Parliament Hill is at the southern part of the high ground of Hampstead Heath. From the top of the hill there are wide ranging views across London, although these views are somewhat obscured by the trees that have grown on the slope leading down from the top of the hill to the fields below.

Parliament Hill has for long been a place to visit, to walk, to look at the view, to play games, and to enjoy the fresh air and open space, above the congested streets of the city.

In August 1947, my father took a number of photos whilst on Parliament Hill, looking at the view, and the surrounding landscape. The first shows an intense, youthful game of football:

I love the concentration and their focus on the ball, a leather ball rather than the lighter balls in use today:

As usual for many places in London, there are different names for the hill, and different origins for these names.

Two names have been associated with the hill, and there is some common root to these names. The name in use today is Parliament Hill, however for most of the 19th century, Traitors Hill seems to have been the most common.

Examples of where references are made to these two names, and their origins include:

From the Holloway Press on the 8th of August 1952: “Of the many explanations of how Parliament Hill got its name, the most popular is that the instigators of the Gunpowder Plot met here to see the effects of their mischief. Some still call the place ‘Traitors Hill’. Another much favoured story dates back to the Civil War when the Parliamentarians had a camp on the site. The Royalists naturally called this ‘Parliament’ Hill ‘Traitors Hill'”.

On the 15th of July, 1897, there was a report of a garden party given by Baroness Burdett-Coutts at her home in Highgate, and after the garden party “A great many of the guests strolled through the numerous walks towards Traitors; Hill, whence, perhaps, the finest panoramic view of London is to be obtained. The extent of the view seemed to impress the Colonial visitors. Traitors’ Hill is so called from the fact that Catesby and his fellow conspirators awaited there the result of Guy Fawkes villainous attempt to blow up the Houses of Parliament”.

The hill seems to have been the destination for those holding parties in the surrounding houses, as another report from the Morning post on the 2nd of June 1834 explains that after a Fete held by the Duchess of St. Albans at her nearby villa “After the déjeuner there was a promenade to Traitors Hill, which is half a mile from the house, and through the most romantic labyrinth imaginable, whence there is a prospect of London and the counties of Essex, Kent, Surrey and Sussex.”

There are also claims that the Parliamentarians had cannon on the hill during the Civil War, and also used the high point as an observation post.

So whatever the true source of the name, it seems to date back to the 17th century, either from the 1605 Gunpower Plot or the English Civil War between 1642 and 1651.

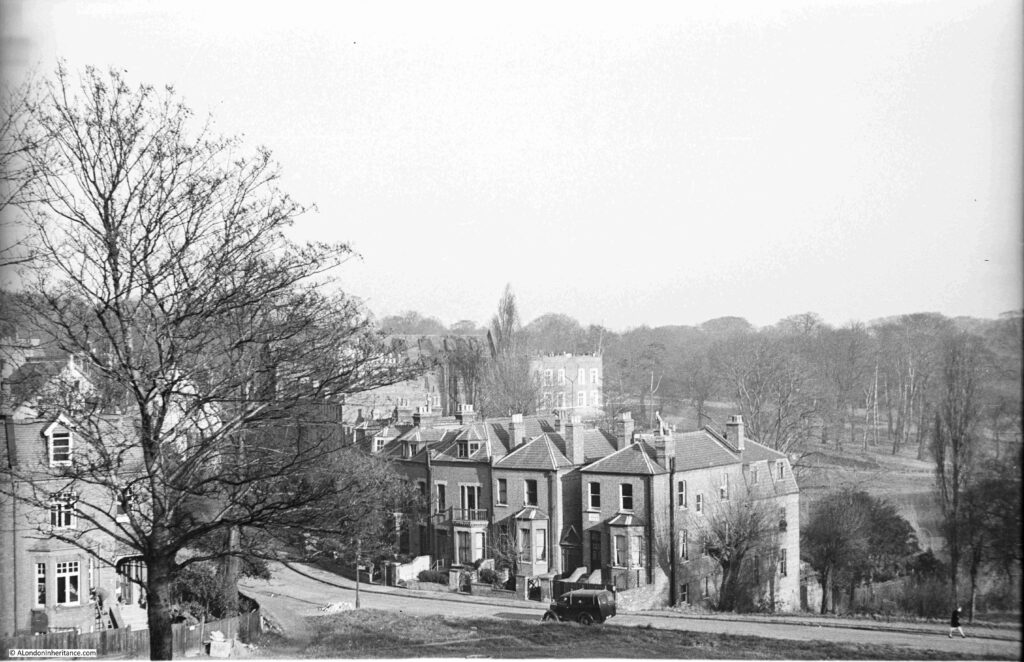

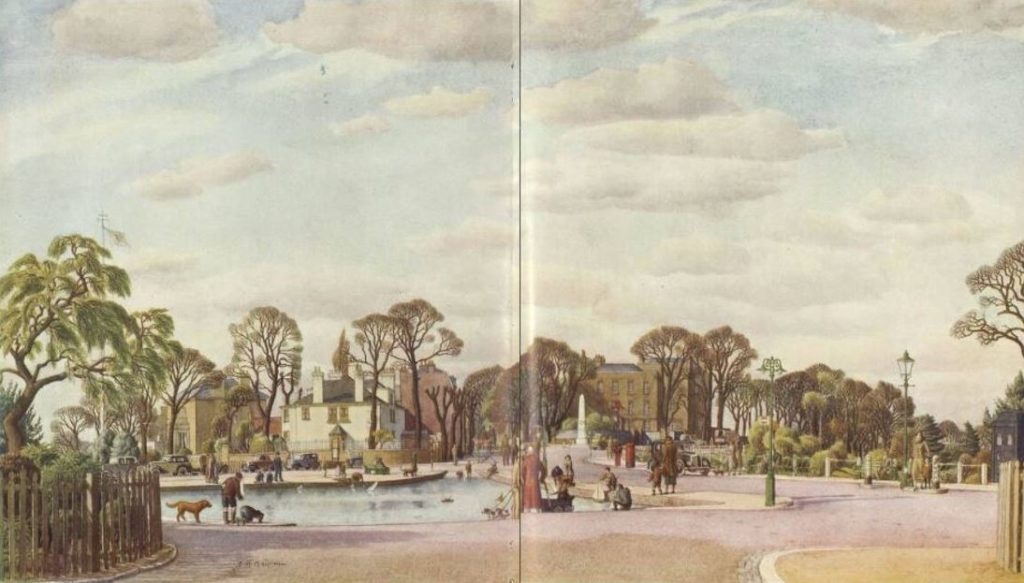

Looking east towards Highgate:

The same view in September 2025:

In both photos (a bit hard to see in my father’s photo due to the resolution of the film) you can see the spire of St. Michael’s, Highgate, the church that stands higher than any other church in London.

A close-up of the church from Parliament Hill, and hidden in the trees just below, someone seems to have a strangely large satellite dish:

Looking to the south-east:

Looking over the city in August 1947, hardly a tall building in sight:

In the above photo, look between the trees and below the hill are open fields, Parliament Hill Fields. At the end of these fields are some low rise buildings. These are the Parliament Hill Fields Lido:

Parliament Hill Fields Lido was opened on 20 August 1938, and the following is a typical newspaper report on the opening of the Lido, part of a scheme by the London County Council for Lido’s across London:

“NEW £34,000 LIDO FOR LONDON – BATHING POOL TO HOLD 2000. With the opening of the new L.C.C. lido at Parliament Hill Fields on Saturday, another important link in the programme of providing London with a chain of modern swimming pools will be completed.

Since Mr George Lansbury, when first Commissioner of Works, gave London its first lido in Hyde Park in 1930, the popularity of these pools has increased enormously.

After Hyde Park came the first lido to be designated as such at Victoria Park built in 1934-35. Records show that in the height of the summer as many as 25,000 people bathe there on a Sunday morning.

The Parliament Hill Lido covers an area of approximately two and a half acres. It is 2ft 6inches deep at the shallow and 9ft 6 inches at the deep end, and holds 650,000 gallons of water, which will be completely filtered and purified every five hours. There are to be fixed and spring diving boards, foot and shower baths, and accommodation is planned for a maximum of 2024 bathers at any one time.

There are two terraces for spectators, and a café available for bathers and spectators alike. The lido had cost approximately £34,000.

The scheme originally approved by the L.C.C. also provided for lidos at Charlton Playing Fields at a cost of £25,000, Battersea Park, £40,000, Ladywell Recreation Ground, £27,000 and Clissold Park, £25,000.

The one at Charlton is nearing completion. The others will be undertaken by convenient stages with a view to the cost being distributed over a reasonable period.

Set among the trees, the lidos of London are vastly different from the cheerless, old-fashioned type of swimming bath. It would seem that they will ultimately render the old baths obsolete.

Including the two lidos already opened, the L.C.C. has eleven open-air swimming pools in London. These were patronised by over 1,000,000 swimmers in a year. Taking the lidos of Hyde Park and Victoria Park alone, the attendances in 1937 were: Children: 62,922, Adults: 175,379, Spectators: 93,731.”

The entrance to Parliament Hill Lido:

Returning to the top of the hill:

Parliament Hill and the fileds below, have long been a place to visit. The above photo shows a couple of children, and earlier photos in the post show people looking at the veiw, and more children playing football.

It was also a very popular place on public holidays, for example om the 11th of June 1892, the Hampstead and Highgate Express reported that: “PARLIAMENT HILL FIELDS – There were some thousands of holiday-makers in these picturesque fields on Whit-Monday. The International Band performed a selection of music in the afternoon, and in the evening Mr. Blake’s band similarly ministered to the enjoyment of the public. Cricket and lawn tennis were in full operation, and attracted large numbers of spectators.”

In 1947, the view from Parliament Hill was less obscured by trees than it is today, There were few stand out features as building height was much lower than it is today. The photos by my father were also made using the lower quality of film available post-war to the amateur photographer, and although taken using a Leica camera and Leica lens, enlarging the photos to look at distant features does not reveal much detail.

Comparing 1947 with today, shows just how the city has grown upwards:

The Parliament Hill viewing point today:

The view towards the towers of the City of London:

The Shard, with the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral to the lower left of the Shard:

The BT / Post Office Tower, and to the lower left of the tower is the Victoria Tower of the Houses of Parliament. It must have been in this direction that the Gunpowder Plotters were looking, expecting to see an explosion – if the stories of one of the origins of the name Traitors Hill is true:

In the middle of the above photo, in the distant haze, is the radio and TV tower at Crystal Palace.

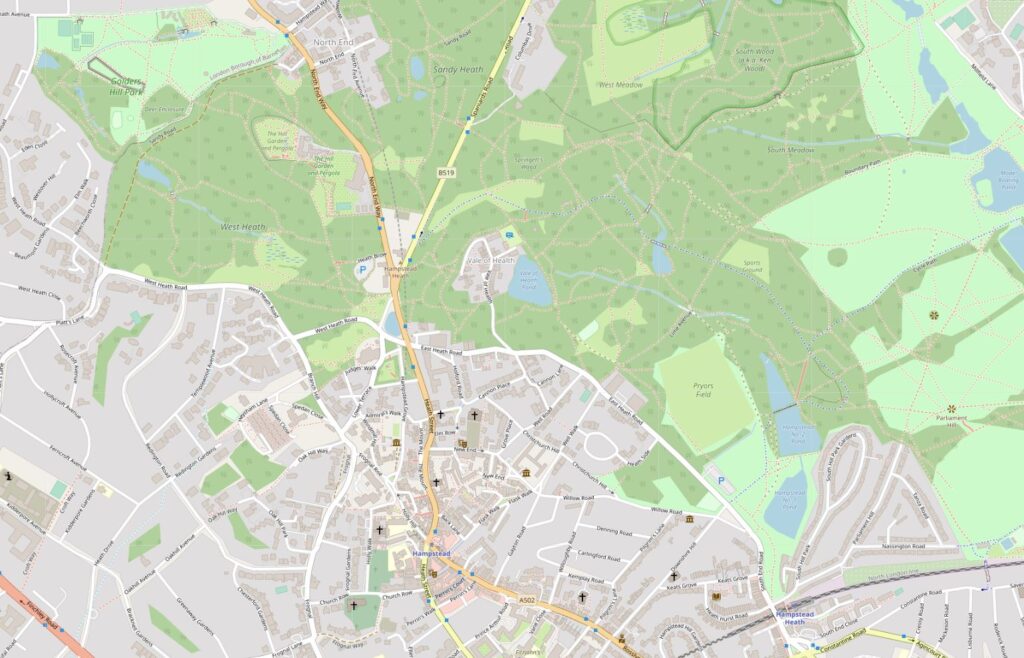

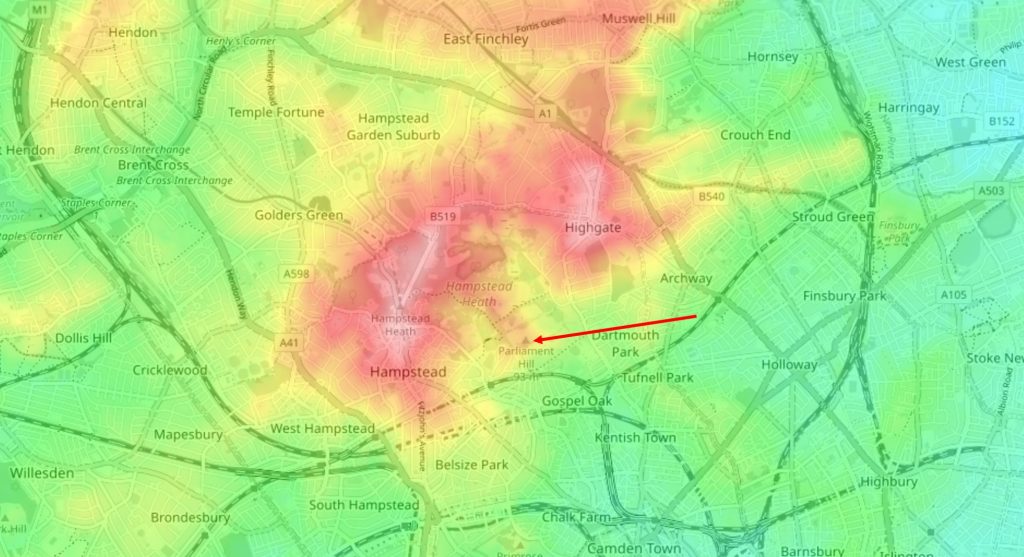

We can see why Parliament Hill is such a good place for a view by looking at a topographic map of the area.

In the following extract from the excellent topographic-map.com the high ground of Hampstead and Highgate is shown in reds and pinks, with the surrounding low ground in yellow and green.

I have marked the location of Parliament Hill with a red arrow, and as can be seen, it is on a small promontory, extending south from the higher ground of Hampstead Heath. To the right is the higher ground of Highgate, as illustrated by photos earlier in the post showing the spire of St. Michael’s, Highgate:

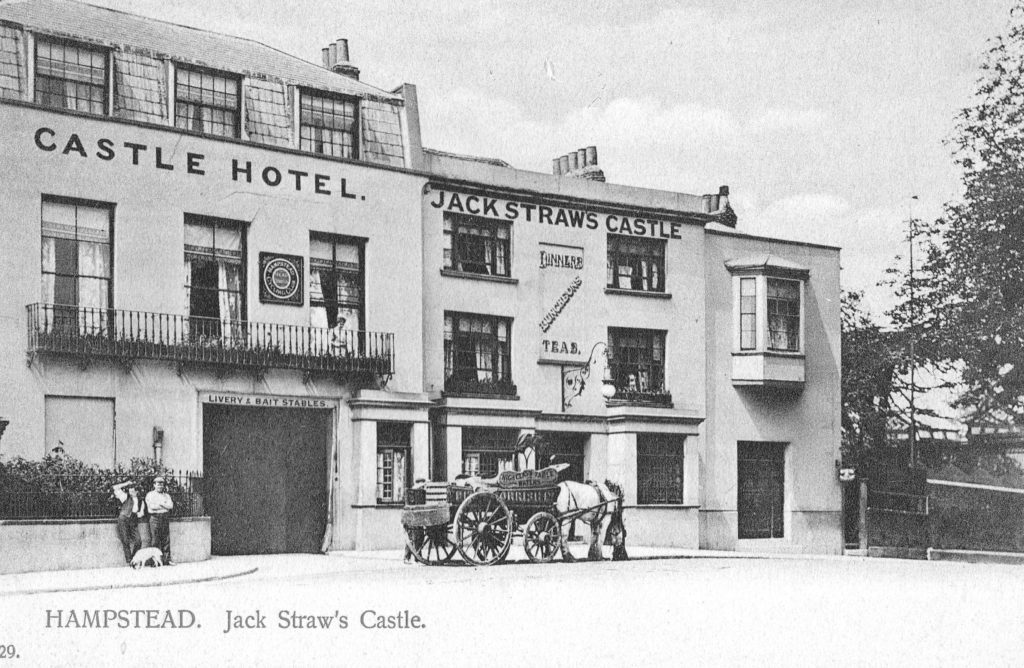

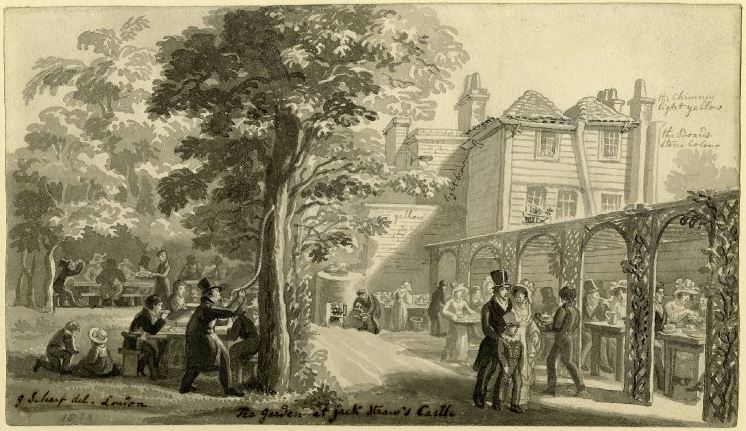

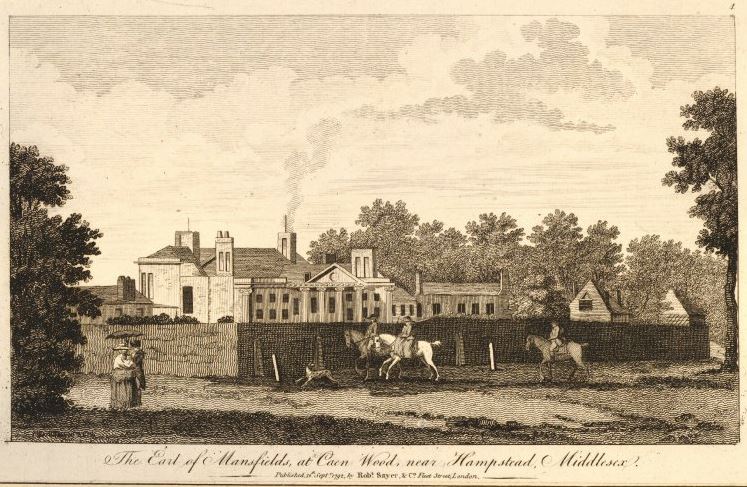

Parliament Hill as a viewing point and open space, has been photographed and painted for many years.

The following is dated 1841 and is by E.H. Dixon, and shows a “View of Highgate Church, from Parliament Hill in Hampstead Heath” (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)::

And a 1938 view by Joseph William Topham Vinall of “London, & Crystal Palace from Parliament Hill (before fire)” (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)::

Surrounding the viewing point:

Looking up at the viewing point on Parliament Hill in 1947:

The tress just below the viewing point at the top of Parliament Hill obscure the full view, and you need to move left and right to view different parts of the city below.

Fromn the viewining point, there is a path that leads through the trees and bushes to a lower point, which does though provide a full panorama of the view to the south.

Descending through the trees:

In the middle of the treeline, there is a dried up stream bed, and just to the side an area that is still damp and muddy – one of the many springs to be found in the area:

Once through the trees, the full panaorama opens up:

Click on the following panorama to enlarge:

As well as the view to the south, looking to the east we can see the Emirates Stadium:

Walking down the hill into Parliament Hill Fields, there is evidence of a long hot, dry summer:

At the base of the hill, as well as the Lido, there is an athletics track. The track itself has recently been refurbished, and I believe that that the original facility dates from 1938, and this is when there were newspaper reports of the “opening of the new L.C.C. track at Parliament Field”, and the brick build and design of the buildings facing onto the track are of a similar design and material to those of the Lido:

That Parliament Hill survives today as a public open space is down to a campaign in the 1880s.

In the later part of the 19th century, the hill was at risk of development. Houses had been springing up in the desirable areas around Hampstead, Highgate and Parliament Hill, and what the press called “The Battle of Parliament Hill” was a campaign to keep the hill free of housing, and retained as a public space.

This came about as a result of the Hampstead Heath Enlargement Act of 1886. The aims of the act was described in the Pall Mall Budget of the 20th October 1887:

“In the first place, the object sought for is the enlargement of Hampstead Heath, but is in reality the preservation of it. The actual proposal was the acquisition of the open space known as Parliament Hill, which, of, course, would, to that extent, be an enlargement of Hampstead Heath. But the point to be most insisted upon is that if Parliament Hill be not acquired Hampstead Heath would be spoiled. For one thing, half its beauty will be destroyed; but it is not the aesthetic consideration that we wish now to place in the forefront, although the destruction of all Coleridge saw ‘looking down from Hampstead Heath’ would of itself be no mean loss. More important, however, than a supply of food for the aesthetic sense, is a supply of fresh air for the lungs, and if Parliament Hill were once to be covered in bricks and mortar the health giving quality of Hampstead Heath would be destroyed.”

Parliament Hill was purchased for the public in 1887 for £300,000.

There is an ancient tumulus on the northern side of the hill, which has been excavated, but nothing was found within.

A child did find what was classed as treasure trove on the hill in 1892, reported from the time as “A small boy called Haynes has been the lucky finder of treasure, including coin and antique silver vessels, while playing with a toy spade in Parliament Hill fields. Valued at £2,000, the treasure trove has formally been taken over by the Crown and the lad’s compensation will be the bullion value of the articles only.”

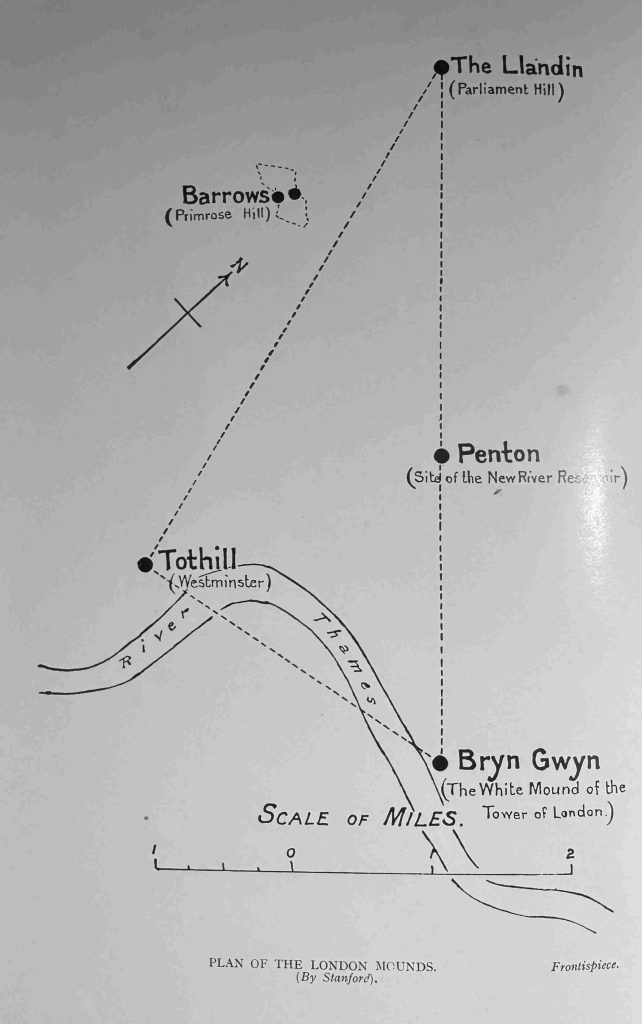

Parliament Hill has also attracted myths and theories about the use of the place in antiquity. In the book Prehistoric London – It’s Mounds and Circle by E.O. Gordon (1932), Gordon claims the hill as an ancient meeting place and also places the hill at the northern corner of a triangular alignment of key London mounds:

With the view across London, and across to the hills in the south, Parliament Hill has long been a place where people would stand and look, a place to look across to the hills that surround London to the south, and it is a special place, although probably not in the way E.O. Gordon thought about the place.

Parliament Hill or Traitors Hill – both names have their origins in events in the 17th century, and in the late 19th century the Parliament Hill was saved from the bricks and mortar spreading across London, so we can continue to stand and gaze across the city to this day.