Long term readers of the blog will probably recognise my fascination with the River Thames and how the river has shaped London, and London’s influence on the river.

The river was the main driver in London’s economic growth, providing the route by which ships could reach the City from the sea. This led to the expansion of central London docks, followed by the move of docks from the City out to the Estuary.

The river has also been a weak point, allowing enemies to attack key locations along the Rivers Thames and Medway, and potentially strike at the City.

The River Thames has been lined with various forms of defence over the centuries. I have already written about Tilbury Fort and Coal House Fort, and at Hadleigh in Essex there are the remains of a medieval castle, refurbished and extended to defend the Thames Estuary against the French during the 100 years war, and to provide a royal residence away from London.

A couple of week’s ago I was in Southend (Gary Numan at the Cliffs Pavilion – reliving the late 1970s / early 1980s), so I used the opportunity to visit Hadleigh Castle, just to the west of Southend, on a hill and overlooking the estuary of the River Thames.

The origins of Hadleigh Castle date back to 1215, when King John gave Hubert de Burgh land around the village of Hadleigh. de Burgh constructed the first castle on the site to demonstrate his position in the country and ownership of the Manor of Hadleigh.

As was often the case, relationships became strained as power shifted and de Burgh was forced to return his lands to Henry III in 1239.

Not much happened at the castle until the early 1300s when Edward II started to use the castle as a residence and constructed a number of internal buildings to help make the castle more suitable to providing royal accommodation.

Hadleigh Castle’s potential value as a fortification overlooking the Rover Thames was seen by Edward III during the Hundred Years War – the period straddling the 14th and 15th centuries when the Kings of England fought for the French crown, and the ownership of lands in France.

The Thames was a route whereby the French, and their allies, could attack the towns along the river, potentially all the way to London. This was a very real risk as demonstrated by the attack on Gravesend in the 1380s, and concerns that the French were assembling a large fleet for invasion.

Edward III built on the work of Edward II, strengthening and extending Hadleigh Castle.

Edward III may also have been interested in the castle as a retreat from London, providing views over the river and estuary. The area around the castle also provided extensive hunting grounds for Edward III and his guests.

The river provided easy access to the castle and there are records of the Royal Barge being moored at Hadleigh.

Royal interest in Hadleigh Castle was short-lived as after the death of Edward III the castle was no longer used as a royal residence, instead being leased to a series of tenants, until being sold off in 1551 to Lord Riche, who took no interest in occupying the castle, and started demolition to sell off the castle as building materials.

The version of Hadleigh Castle we see today is therefore a ruin and a shadow of its former self. Just a few towers, walls and foundations that have survived demolition and the castle’s geologically unstable location.

This is the view looking east, with the estuary on the right and the one remaining tower in the centre of the photo.

Almost the same view was the subject of a painting by John Constable in 1829, titled “The Mouth of the Thames–Morning after a Stormy Night”:

Image credit: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

I really do like this painting. It perfectly captures the relationship between the sky and the estuary. Blue sky is starting to appear after the stormy night, and the sun is shining on the ruins of the castle.

In many ways Constable’s view is much the same today, although there was no Southend pier jutting out into the estuary in 1829, and today, cows are not grazing on the slopes adjacent to the castle.

Constable exhibited the painting at the Royal Academy in 1829, where it was described as “Full of nature and spirit, and graceful easy beauty; though freckled and pock-marked after its artist’s usual fashion”.

The painting now appears to be part of the Yale Centre for British Art collection in New Haven, Connecticut in the United States. I am not sure how it was acquired by the Yale Centre. In 1936 newspaper reports were congratulating the National Gallery on the acquisition of the painting and saving the painting for the nation.

The same newspaper reports were also expressing concerns about the planned development of the area around Hadleigh Castle. Factory sites were planned for the land around the castle. The villages of Leigh-on-Sea and West Benfleet were expected to expand towards the castle, and a road was planned to be built to run parallel to the railway.

The site of the castle is still relatively isolated. There are houses about half a mile further in land, and the Salvation Army run Hadleigh Farm is on the approach to the castle. I suspect the war put a hold on the proposed factories.

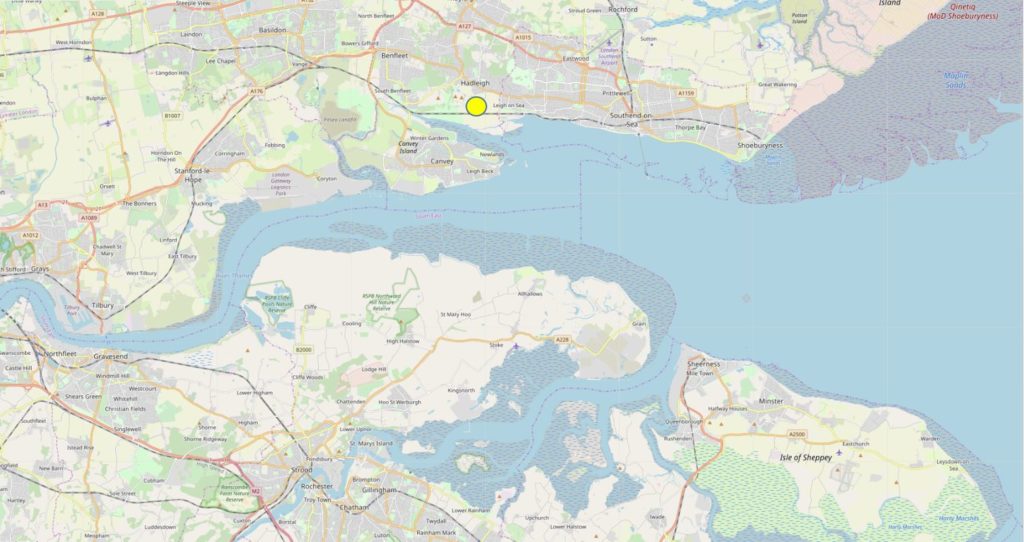

The following map extract shows the strategic location of Hadleigh Castle, marked by the yellow circle (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The map shows that the castle’s position provided an ideal view over the estuary, and any attacking force would be clearly seen. The map does not clearly show the height of the castle, which stands 42m above sea level. Not that high, but high enough in this part of southern Essex to provide a commanding view over the river.

The geology of the site is interesting as the castle stands on the edge of high ground, which quickly falls to a level stretch of land between the castle and the river. The following photo is the view looking towards the south-west, with a c2c train running on the route from London Fenchurch Street to Southend and Shoeburyness.

In the distance are the cranes of the London Gateway port, and in front of them are the oil storage tanks to the west of Canvey Island and in Coryton. Canvey Island is between the oil tanks and the stream of water.

The view below is looking south. The river is at sea level, and the land gradually rises to 6 metres at the rail line.

During the medieval period when the castle was constructed and in use, the area between the mound on which the castle was built, and the river would have been marshland, and probably subject to flooding at times of very high tide.

The view looking to the east, Southend Pier is visible in the distance.

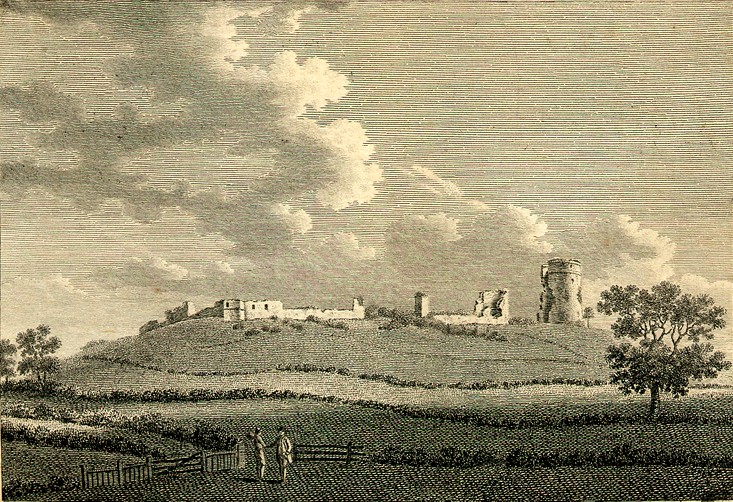

The following print from 1772 shows Hadleigh Castle from where the railway line runs today. Although the majority of the castle had been demolished for building materials, some of the southern walls still remained, although the majority of these have since disappeared.

Although from a strategic perspective, Hadleigh Castle was built in an ideal position, with a commanding view over the approaches to the estuary and River Thames, geologically it was built in a very precarious position.

The castle sits on an unstable spur of London Clay. Over the centuries there have been numerous slippages and damage to the castle building, beginning soon after completion of the castle. The last major landslip was during the winter of 1969 / 1970.

Today, about a third of the southern side of the original castle has been lost due to slippage.

In Constable’s painting, two towers can be seen. Today, only one tower survives. The second tower to the north has slipped and collapsed and the remains can be seen to the right in the photo below:

The main tower still looks impressive, and gives a good idea of what the whole castle must have looked like in the 14th century:

Although the tower sits at the edge of the descent down to lower ground towards the river, and cracks inside the tower tell of the possible future for this one substantial remaining part of Hadleigh Castle.

The exterior of the collapsed tower:

The interior of the collapsed tower:

The following photo from Britain from Above shows Hadleigh Castle in 1930.

The following photo from Britain from Above shows Hadleigh Castle in 1930.

The tower on the left of the above photo is the one that has since collapsed.

The photo does provide a good view of the overall size of the castle, and the rather precarious position, situated on top of a high mound of London Clay.

The river is to the right of the photo and the two towers are facing to the east – to the Continent and to the Estuary, so the two large towers would have been the first evidence of the king’s power that anyone arriving from the Continent would have seen.

19th century interest in Gothic landscapes and architecture, and recreating late medieval architecture may have been the source of considerable growth in visitor numbers to Hadleigh Castle. Constable’s painting probably contributed, as did the relatively easy access from London on the Fenchurch Street line.

Visitor numbers were of such a size that in the later part of the 19th century, a large refreshment room was opened in the grounds of the castle, with seating for 400 people.

No such facilities at the castle today, just neatly clipped grass as the castle is now under the care of English Heritage.

When the Crown sold the castle to Lord Riche in 1551, he seems to have commenced the demolition of the castle for building materials in an organised manner. In the grounds of the castle are the remains of a lead melting hearth from the mid 16th century. The hearth was used to melt down the lead window frames from the castle, thereby making it easier to transport the lead away from the site.

The hearth is located in the middle of the castle’s hall, with only the foundations remaining today.

Part of the remaining curtain wall:

The southern edge of the castle, looking towards the west:

The above photo marks the boundary to the left, with the land that has fallen away in previous landslides.

To the left, there was the King’s Chamber, continuation of the curtain wall surrounding the castle, and the south tower. All lost as the London Clay fell away.

The one main archaeological excavation of the castle was carried out in 1863 by a Mr H.M. King, working for the Essex Archaeological Society. The work was extensive, however the finds from the excavation have since been lost.

Edward III also constructed a castle on the opposite side of the Thames at Queensborough on the Isle of Sheppy, although nothing now survives of this castle.

So, Hadleigh Castle is the one remaining example of a medieval castle on the Thames Estuary. The last land slip was in 2002, so for how long the castle will remain in its current condition is open to question as the London Clay gradually slips away.

Although the castle is fading away, it is still more substantial than the ghost that a Mr Wilfred Davies of Canvey Island was looking for in the 1960s and early 1970s, when armed with tea and sandwiches, he would keep a nightly vigil at the castle, looking for a female ghost that was reported to slap people’s faces. I bet though, on a dark night at the castle’s isolated position, looking over the Thames Estuary, it would be easy to imagine the ghosts of those who made it their home in the 13th to 15th centuries.

A very interesting read of a location that is only a few miles from me. I have only visited it once about 10 years ago but this has renewed my interest so will make a determined visit next week. It is sad seeing the remains of a once great castle but in Maldon there are the remains of a leper hospital which you might consider to be worth a visit.

Gary Numan does a good concert!

As usual a great blog to cheer up my Sunday morning

The Constable painting was an extra bonus

Many thanks

David Barnard

Gray’s Inn

For some years in the 70s I used to commute into London on the Fenchurch line and often wondered about the history of the castle as I saw it from the train.

Thanks for filling that gap in my knowledge. I did not realise how old is.

I must try and visit it before it disappears completely!

King John, Edward II, Edward III . . . Mr Wilfred Davies.

Such an unsung saga. Thank you for uncovering it 🙂

Thanks so much for this post. I was born in Leigh and lived around the Benfleet area till I was 12. In the 50s and early 60s the castle surroundings were much more overgrown than they are now – English Heritage seems to have tidied them up! I hope the blackberry bushes and gorse are still intact. It used to be a great spot for a Sunday afternoon walk and picnic, and maybe a spot of kite flying. Thanks for jolting my memory!

An excellent, well penned and fascinating article. The efforts man has gone to all along this mighty river but that London clay so often thwarts. Superb read.

Thank you so much for this really interesting article, I never even knew of this castle and it’s history. Keep up the research.

The paintings by constable superb -very informative history

Let’s take a moment to congratulate H M King’s parents for giving him those initials.

The version of Constable’s Hadleigh Castle in the UK is the full-size oil sketch, or ‘six-foot’ sketch’, now in the Tate (Tate Britain). For more information to compliment your excellent blog see

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/constable-sketch-for-hadleigh-castle-n04810

For detailed technical information on the painting see

https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/05/constables-sketch-for-hadleigh-castle-technical-examination.

Both the fully finished version at Yale and the six-foot sketch were featured in the momentous 2006-7 exhibition of Constable’s ‘Great Landscapes’ (Tate, NGA Washington and the Huntington CA). A catalogue is available: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Constable-Great-Landscapes-Anne-Lyles/dp/1854375830

Thanks for your excellent and informative blog

Sarah Cove ACR, lifelong Londoner and Founder of the Constable Research Project

http://www.facebook.com/constable.research.project

Nice write up! I grew up in Leigh and have spent many summer days and evenings walking to Hadleigh Castle. I wasn’t aware of the Constable painting. One small correction though, there are still cows grazing on the slopes! Just that these days they are kept from the castle ruins by a fence.

I lived in Tattersall Gardens overlooking the fields which were my childhood playground. We picked the blackberries, lay in the Salvation Army corn field stubs in the sunshine watching the field mice and climbing trees. There was a pond full of newts, pond skaters and small creatures you now need a licence to even look at. I was on the 1971 dig. I was given the task of digging out the latrine in the King’s chamber on the cliff edge as I was the only girl who could wield a pick axe. I was rewarded by being asked to dig out the brick fire hearth in the middle of the central hall the finding of which caused great excitement on site. This area was rich in animal bone finds, trays and trays and tables full waiting to be identified and cleaned. A great dig, great camaraderie. …. also great because my friend’s father brought up our O level results and I passed every subject! Happy days.