I have been meaning to do this for some time, to take a walk to find all the pubs of the City of London and last Sunday I had the opportunity to do so. I wanted to do this for a number of reasons.

Working with my father’s photos, I am very aware that there was so much else that would have been fascinating to see recorded as a photo. The costs and limitations of film photography always restricted the number he could take as an amateur.

I like photographic themes and snapshots of a theme at a specific time. They tell the story of what life was like, what you could find on the streets of London, at a specific point in time. My first attempt was a couple of years ago when I photographed all the theatres in the West End. All closed now, but at the time a dynamic, cultural environment, attracting many thousands of people into London and supporting many jobs. Those posts are here and here.

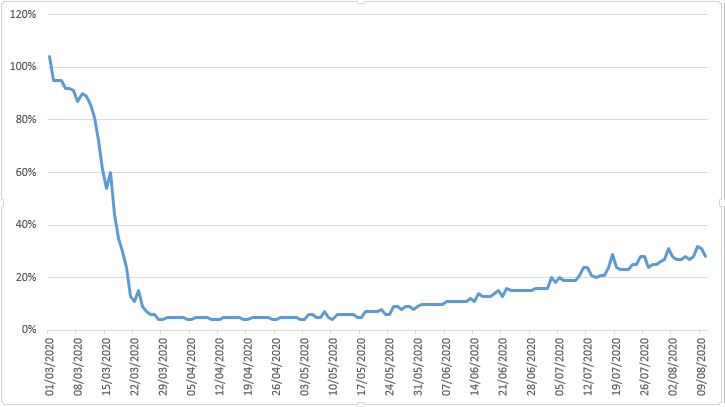

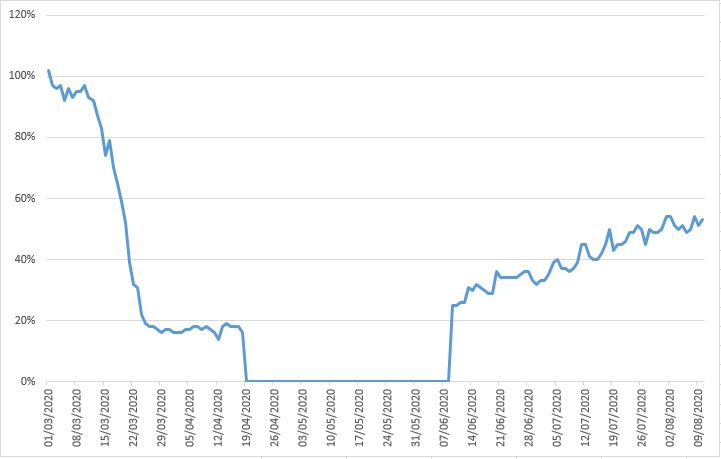

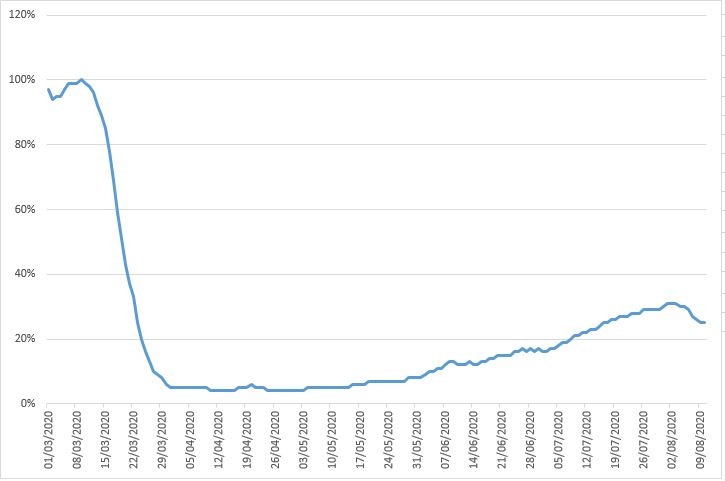

I have also been thinking recently about the impact of the pandemic on the City of London. Is this one of those points in history which results in a significant change, or in five years time will everything be back to normal, the streets, offices, transport systems all crowded.

During the week the City is very quiet. So many companies are finding that it is perfectly possible to work remotely and the potential savings in office space costs are enormous, and for workers, saving both time and money by not having the crowded commute into London are significant benefits.

There will always be a need to have some working space in London, but it may be at considerably reduced levels to those we have at the moment, and whilst working at home offers significant benefits, there is a need for the type of interaction which can only be achieved face to face.

The question will be whether the number of those working in the city return to levels which can support the number of businesses which sell to city workers. All the coffee shops, retailers and pubs.

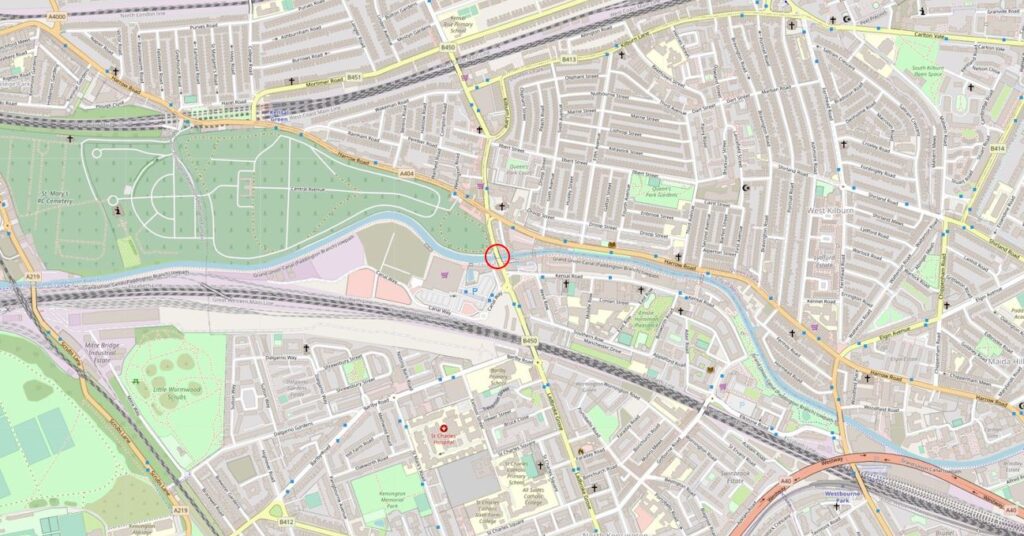

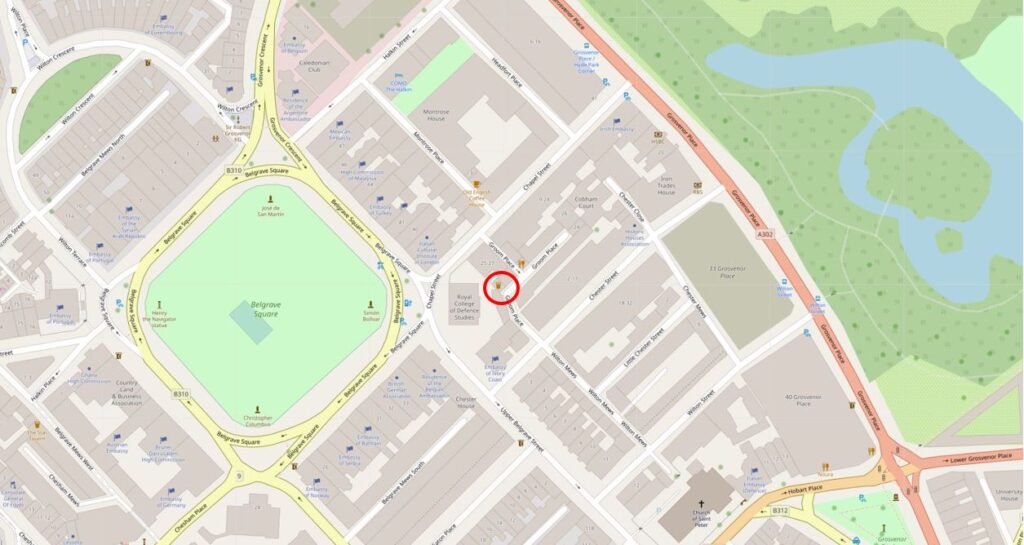

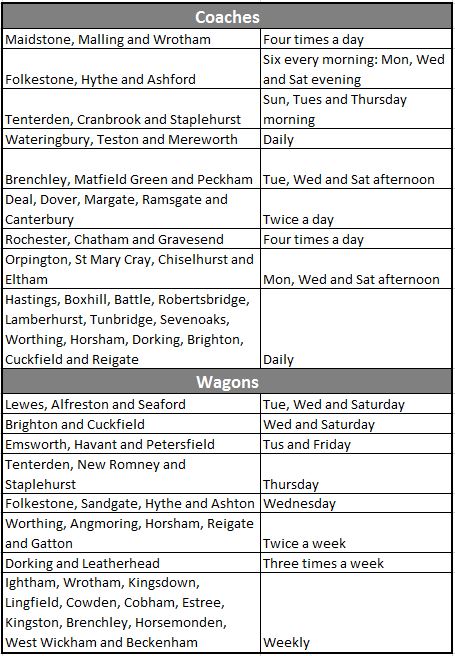

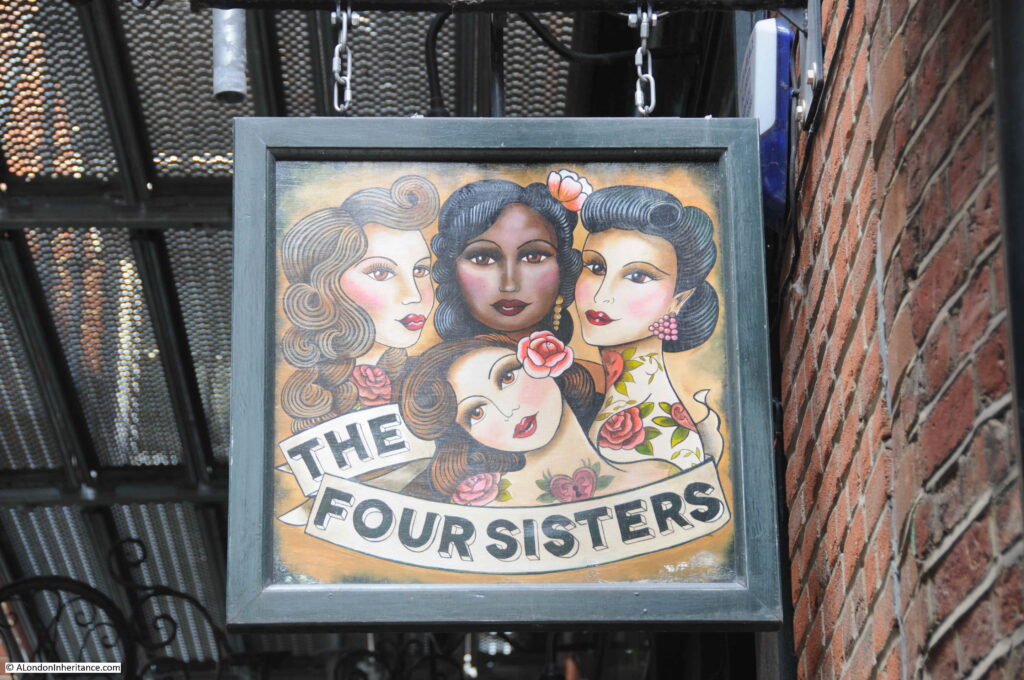

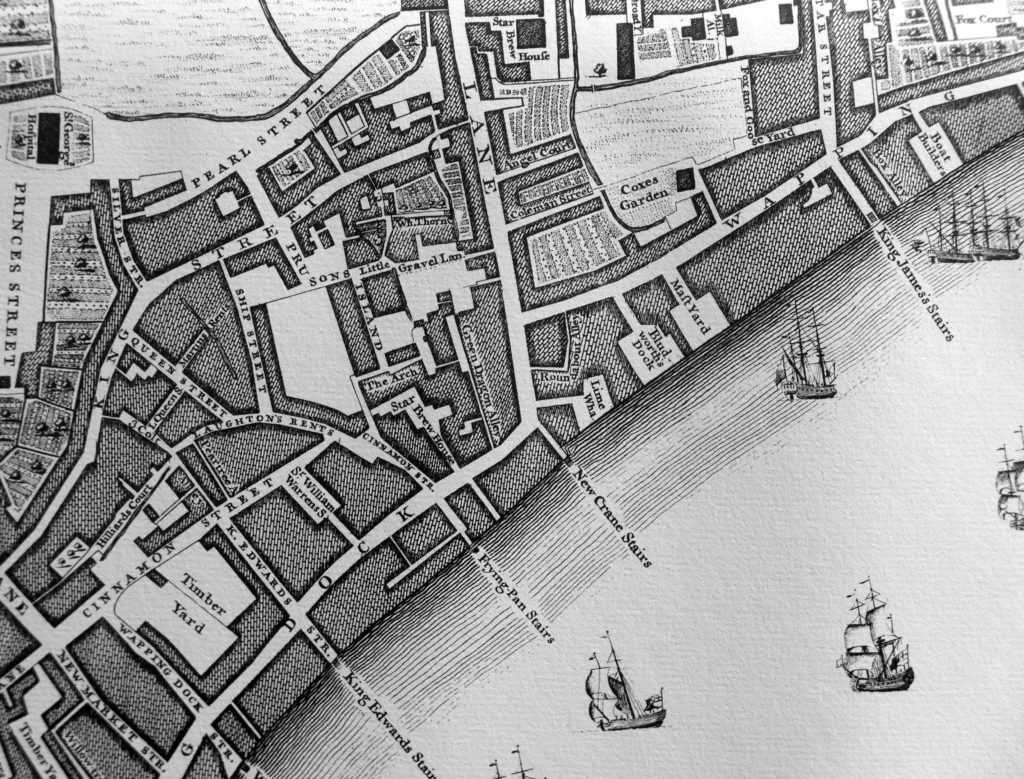

This may be an economic problem for the pubs of the City of London, so I decided to photograph as many as possible during a single day. I know many of these pubs, and also used the data made available on the Corporation of London website where you can map all the premises in the City with alcohol licenses. There are some basic filtering options to help separate out the many restaurants that also have alcohol licenses from the pubs, and I worked out a roughly circular route that took me to a total of 50 pubs.

I know there are some I missed, so will mop these up during a later walk.

Nearly every pub was closed, and the streets of the City were empty. No tourists, very few walkers and very few cars. The congestion charge now applies at weekends, which may also have an impact in reducing the numbers of visitors to the City.

Today’s post has the first batch of pubs, and a midweek post will cover the final batch. This second post will also include an interactive map of all the pub locations.

My walk started in the heart of the City, just north of Gresham Street, at:

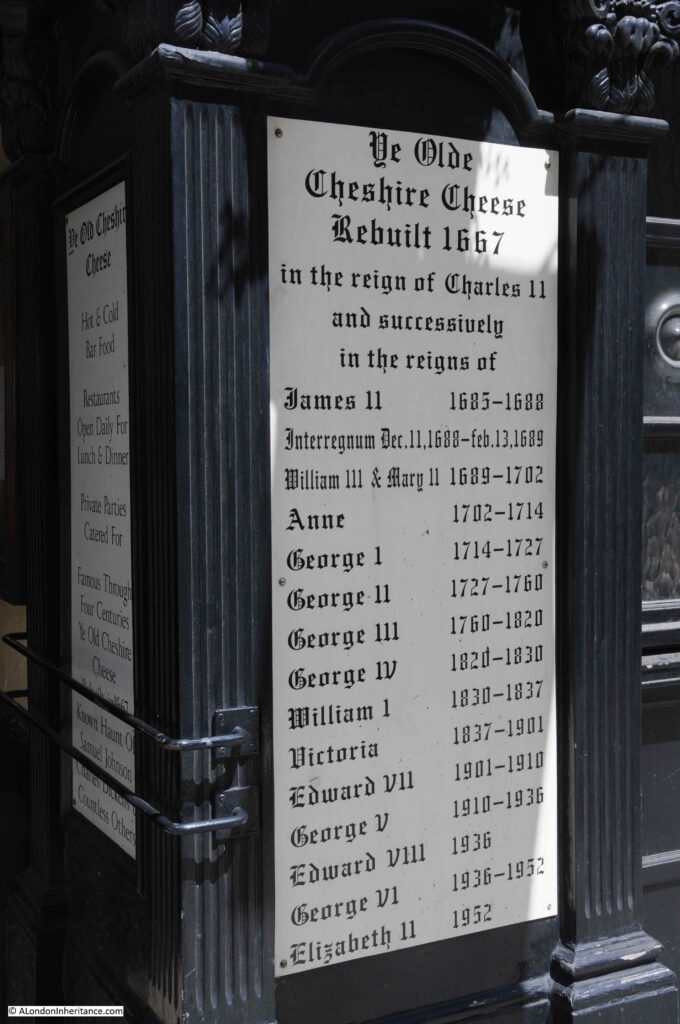

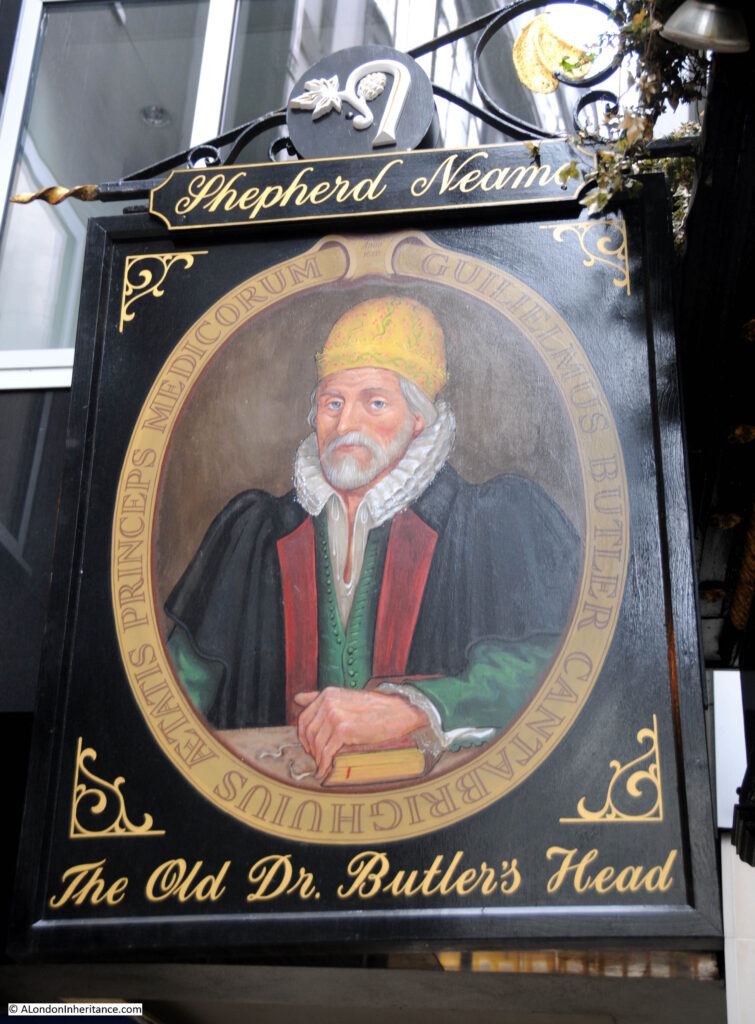

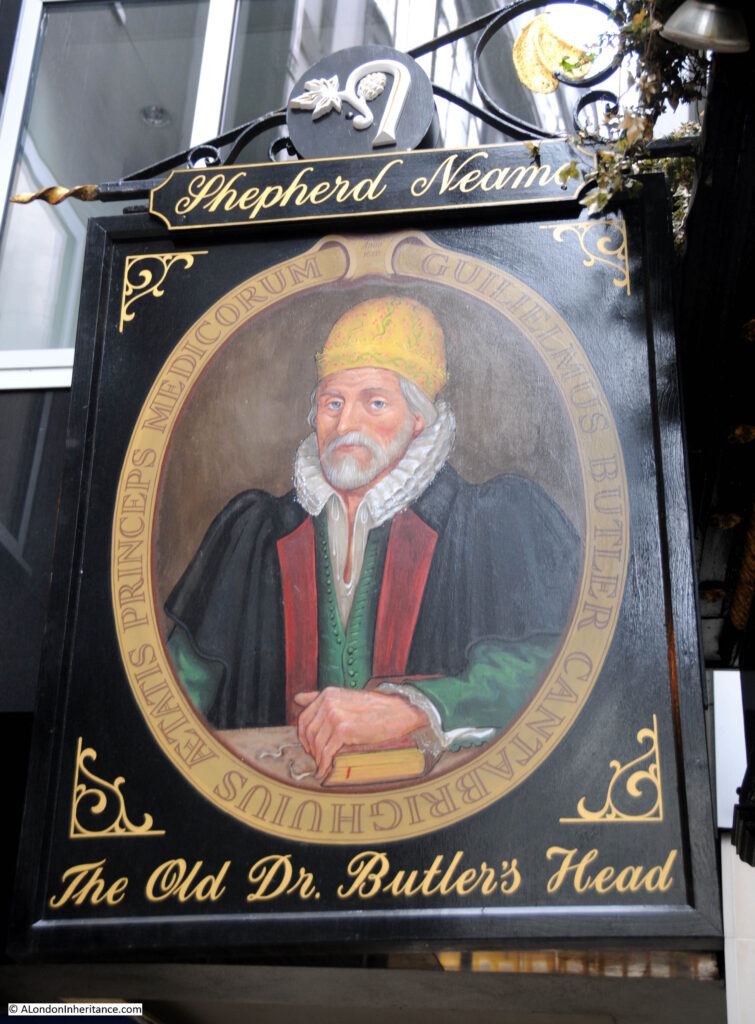

The Old Doctor Butler’s Head – Masons Avenue

With an address in Masons Avenue, you might expect the Old Doctor Butler’s Head to be in a wide street, however you will find the pub in a narrow alley between Basinghall Street and Coleman Street.

The Old Doctor Butler’s Head is an old pub, with the building allegedly dating from just after the Great Fire.

On a summer’s evening, the alley is normally crowded with people having a drink after work.

It is named after Doctor William Butler, the court physician of King James I. Born in Suffolk in 1535, he lived until 1617, and during his life he used a number of bizarre treatments including firing pistols near the heads of his patients with epilepsy to scare the ailment from the patient.

His connection with pubs comes from his creation of a “purging ale” which he claimed had medicinal properties. There were a number of pubs with the name of Doctor Butler selling the ale, and the pub in Masons Avenue is the only one to remain.

The current building cannot date from Dr Butler’s time as it was built at some point after 1666, but there may have been an earlier pub on the same site.

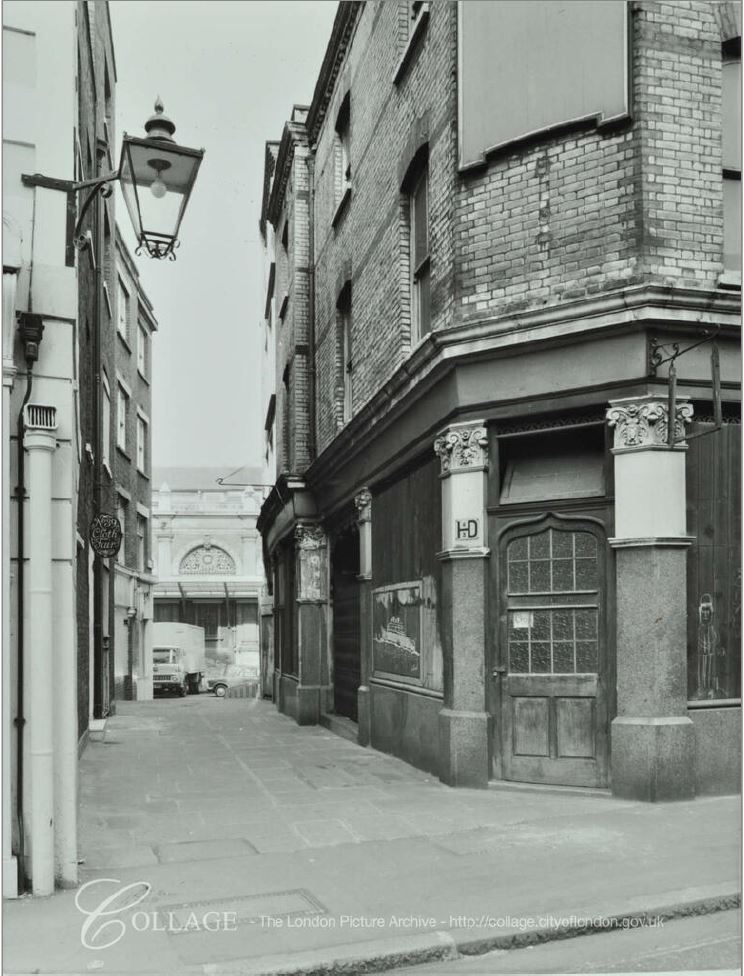

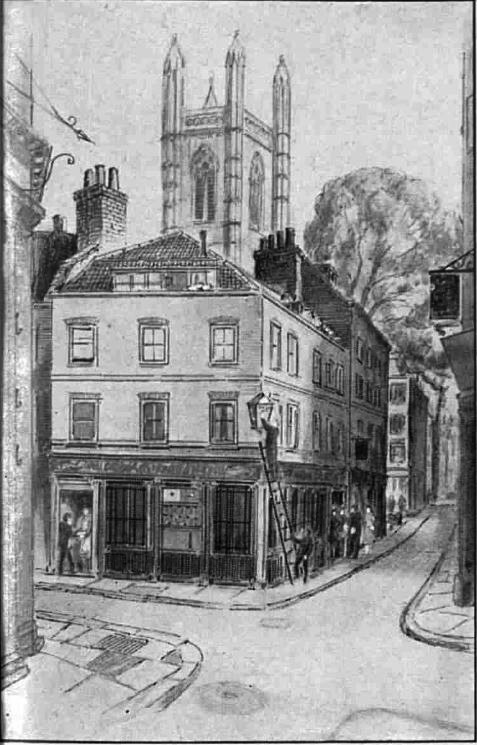

Doctor Butler’s Head looking much the same in 1974:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0975_74_12394

From Masons Avenue, it was a short walk up to the junction of London Wall and Moorgate, to find:

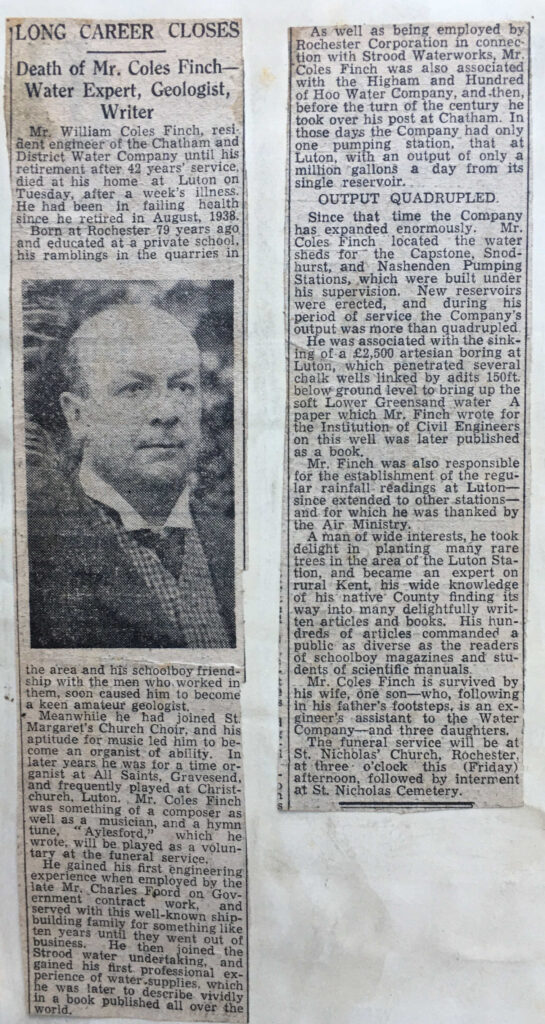

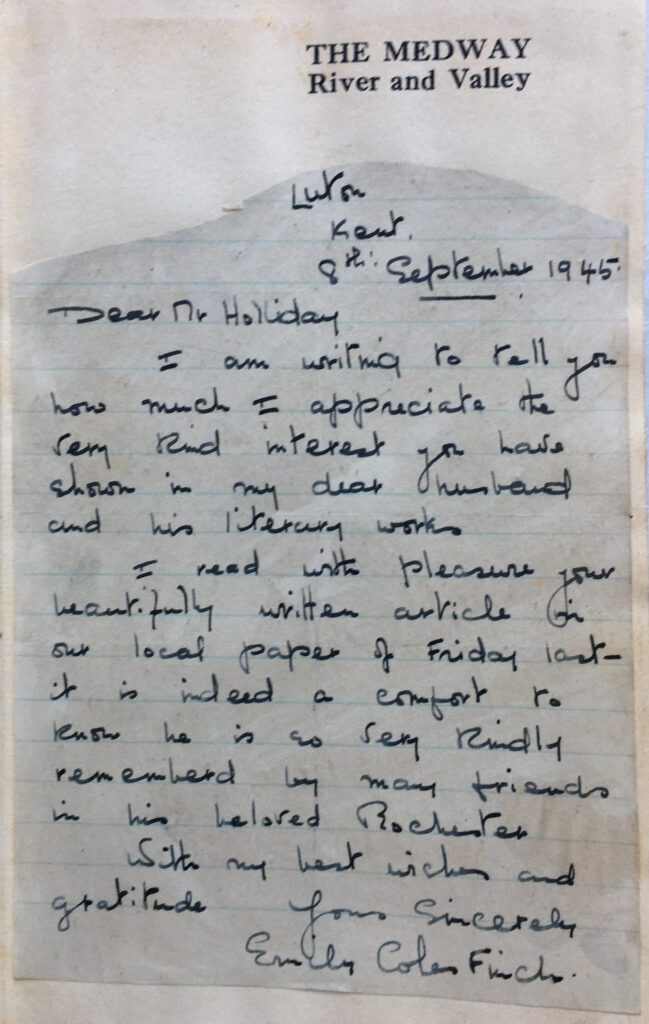

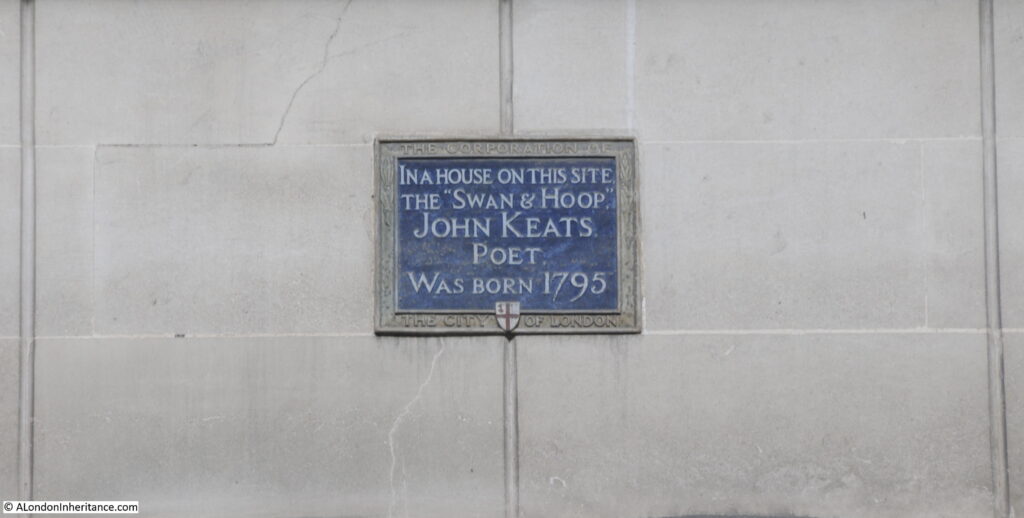

The Globe / Keats At The Globe – Moorgate

I have not been in either of these two pubs for many years, and as far as I can tell they are now effectively one pub.

Walking across London Wall to Moorgate, there is an entrance to the Keats at the Globe in the small space that has now been truncated by the building of Crossrail:

Walk around the corner, and facing Moorgate is a large Victorian pub – The Globe, with a mirror image of the above entrance to Keats at the Globe, alongside the Globe.

The Keats at the Globe was originally a separate pub called the John Keats, but appears to now be a bar associated with the larger corner pub. It make an interesting combination of buildings, with the Globe forming a typical corner pub, and the Keats running through the length of the block of buildings having an entrance at both ends.

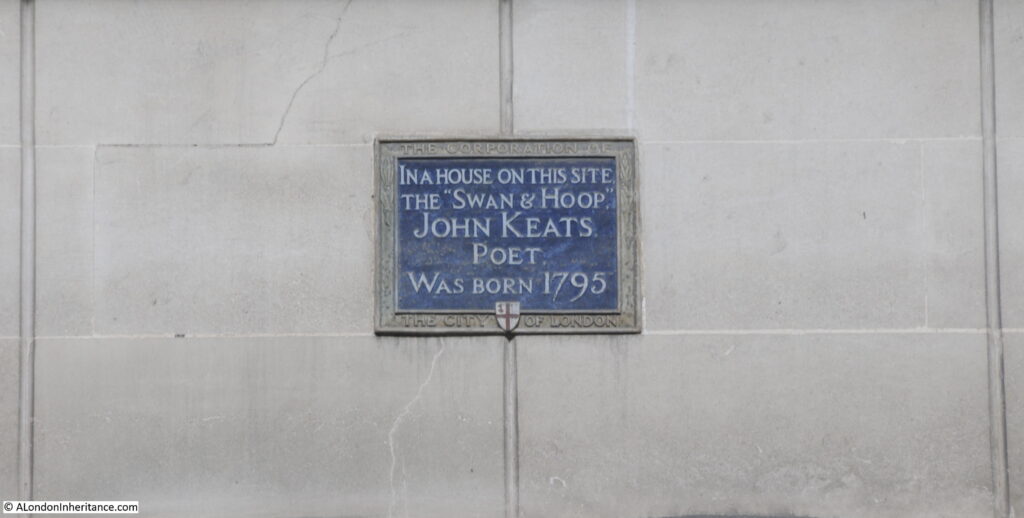

The reason for the Keats name is given in a plaque on the Moorgate facing side of the Keats pub, claiming that John Keats was born in the Swan and Hoop which was originally on the site in 1795.

John Keats was the son of Thomas Keats, a west country stableman, who moved up to London to manage the Livery Stable at the Swan and Hoop. He married Francis Jennings, the daughter of the proprietor of the Swan and Hoop and the poet John Keats would be the result.

Heading further north along Moorgate, then into South Place and Eldon Street:

Red Lion – Eldon Street

The Red Lion is on the corner of Eldon Street and Wilson Street:

Etched onto the pub windows are signs saying that the pub has been a “Purveyor of Quality Cask Ales since 1799”. Until the large corner sign was redecorated, it was claiming to have been established in 1887. I suspect that is when the current building dates from, and there was probably an earlier pub on the same site.

Nothing to do with pubs, but the following photo illustrates how the City streets may well be changing over the coming year. When Eldon Street curves into Broad Street Place, there is a branch of T.M. Lewin, originally founded in Jermyn Street in 1898, For many years, T.M. Lewin branches across the City have been selling shirts and suits to City workers.

However, from now on they will be selling online only, and have announced that all their shops will close. The streets are potentially going to look very different.

From Eldon Street, it was a short walk to Liverpool Street station, and:

The Railway Tavern

On the corner of Liverpool Street and Old Broad Street is the Railway Tavern.

Works for Crossrail have occupied much of Liverpool Street opposite the pub, but now seem to be coming to a close, so hopefully the street will soon be opening up fully.

The Railway Tavern seems to have been built in the 1850s or early 1860s. The earliest record I can find for the pub is from 1864 when the pub was used as a mailing address in an advert.

The pub backs on to the railway lines of the Circle and Metropolitan lines, which are open to the surface just behind the pub.

The Railway Tavern was opposite the old Broad Street Station and is now diagonally opposite Liverpool Street Station, and followed the 19th / early 20th century approach of building a pub outside a railway station and naming it the Railway Tavern.

Broad Street Station has been replaced by office blocks, however the Railway Tavern continues to provide a place for London commuters to have a final pint before running to Liverpool Street for the train home.

The next pub was very close:

Lord Aberconway – Old Broad Street

A short distance from the Railway Tavern, in Old Broad Street is the Lord Aberconway.

The Lord Aberconway was originally named the Kings and Keys, but has not always been a pub. The 1894 Ordinance Survey map does not show a pub at the location. It has though been associated with the nearby stations as it was previously a Railway Buffet and Refreshment Rooms.

The pub is named after Lord Aberconway who was the last Chairman of the Metropolitan Railway.

Outside the pub is a plaque claiming that the Lord Aberconway is “purportedly haunted with the spirits of the Great Fire of London victims”.

Then via Liverpool Street into Bishopsgate, and:

Dirty Dicks – Bishopsgate

In Bishopsgate, all shuttered up was Dirty Dicks:

The pub, originally called The Old Jerusalem, took the name from a character who owned a hardware business in Leadenhall Street.

Nathaniel Bentley was originally a well off, well dressed young gentleman and owned the hardware business in Leadenhall Street. He was engaged to be married, but on the morning of the marriage he received news that his fiance had died. The room where the wedding breakfast had been arranged was locked and he vowed never to open the room again. He changed his way of living, wearing rags, never cleaning the store and generally living in squalor.

Whether the story is true is open to question. There are a number of alternative stories for why Nathaniel Bentley became Dirty Dick. For example, the East London Observer on the 11th June 1870 also used the marriage as the reason, but in this story he was jilted on the morning of the wedding with his bride claiming the cause being that he had not washed his neck. As a result, he swore an oath that he would never again use a bar of soap, use a brush, or allow a woman to enter his doors again.

What ever the cause. his actions resulted in him acquiring the nickname of Dirty Dick.

He refused his landlord access to the building, but when the landlord finally had access: “He found pictures and looking glasses on the walls of the living-rooms so encrusted with dirt that they could only be distinguished from the walls at close quarters. A study was the breeding place of countless spiders. In a bedroom was an old coat lying on the floor – the mattress used by Dirty Dick when he lay down to sleep”.

When he finally left the shop, he took shop soiled goods with him worth £10,000, and moved to Shoreditch. He did not stay there for long, and went on a tour of the country and whilst at Haddington in Scotland, he was taken ill and died in 1819, being buried locally in Haddington.

The link between Nathaniel Bentley and Dirty Dicks is somewhat tenuous. A landlord of the pub is alleged to have removed the contents of Bentley’s rooms in Shoreditch to the pub. The pub was later rebuilt in 1870, and continued the reputation as it was certainly a unique history, and good selling point to get visitors to the pub.

Also on Bishopsgate was:

Woodin’s Shades – Bishopsgate

Almost opposite Dirty Dicks, and on the corner of Bishopsgate and Middlesex Street is Woodin’s Shades:

Woodin was one William Woodin and the word “Shades” refers to a wine cellar.

William Woodin owned wine cellars in Thames Street, and a newspaper report in the Globe on the 6th April 1882 reported on the closure and sale of the wine cellars: “OLD WOODIN SHADES CELLARS – Thames-street. Absolute and Unreserved SALE of about 4,000 dozens of WINES of various descriptions in consequence of the immediate demolition of the Premises by the Fishmongers’ Company”.

As well as the wine cellars in Thames Street, William Woodin was also the landlord of the Woodin’s Shades pub in the 1860s. The current building dates from 1893.

The Woodin’s Shades pub in 1959:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: M0029433CL

From Bishopsgate, down Middlesex Street with a very quiet Sunday morning market was:

The Astronomer – Middlesex Street

The Astronomer is a relatively recent name for this pub in Middlesex Street. Reopened in 2016 as the Astronomer, it was the Shooting Star, and before that, the Coach and Horses which opened in the middle of the 19th century.

It is a Fuller’s pub, and they claim the name Astronomer is because the building in which the pub is located is called Astral House. I would have thought the Shooting Star was also an astronomy related name, so no idea why pub companies sometimes change the name of pubs. Possibly to provide a clean break with any past issues, but I am not aware of any that would have resulted in a name change from Shooting Star.

From Middlesex Street, up north along Sandy’s Row to find:

The Kings Stores – Widegate Street

The Kings Stores is on the corner of Widegate Street and Sandy’s Row.

The current pub dates from 1902, when it was rebuilt as confirmed at the top of the building:

Before the rebuild and name change, there was a pub on the same site, but called the Hoop and Grapes. I suspect the name change was to give the pub a unique name, rather than being one of several Hoop and Grapes in the City, two of which we will be visiting in this journey around City pubs.

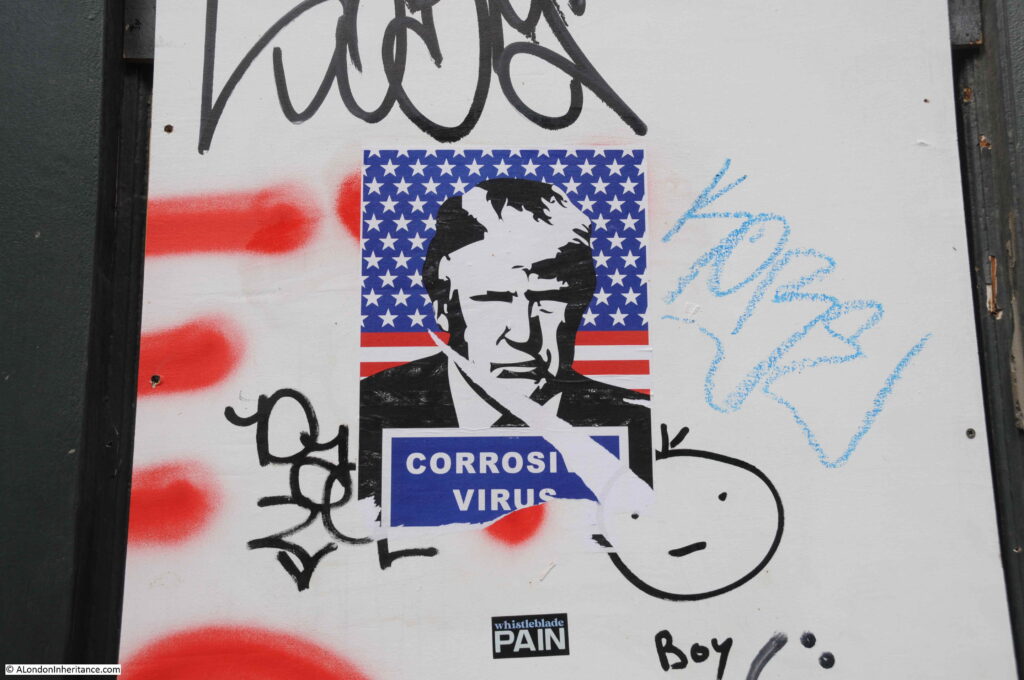

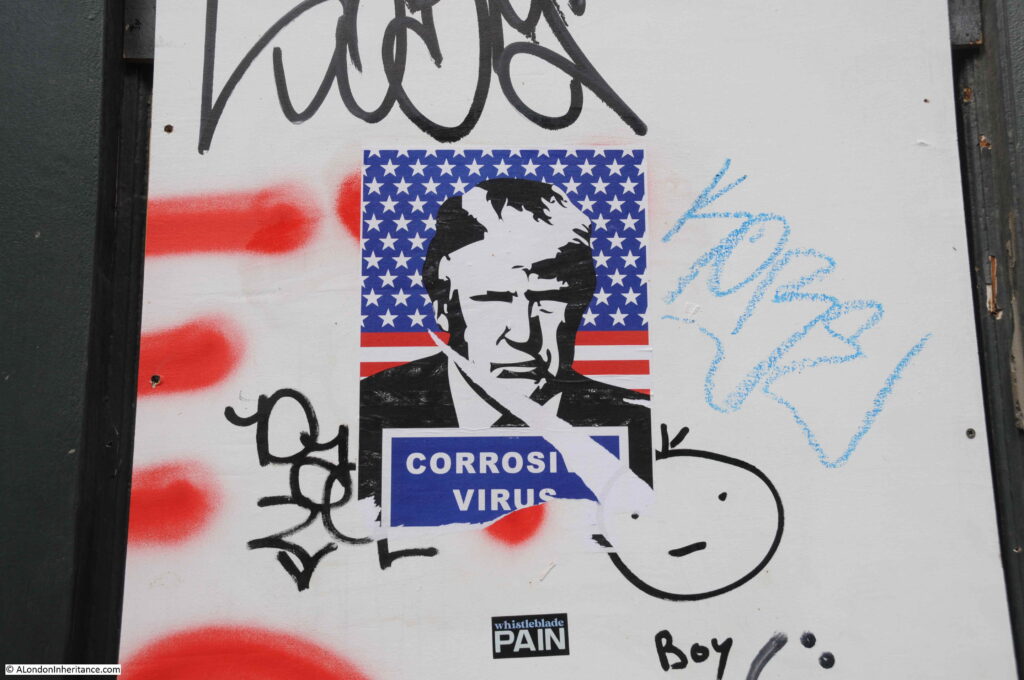

I always photograph graffiti and stickers when walking the streets of London. They are off their time and provide a record of different views of world events. There were several on my City walk. This was on a door opposite the Kings Stores.

Back down Sandy’s Row, then via Middlesex Street, Catherine Wheel Alley and Cock Hill, to:

The Magpie – New Street

The history of the Magpie should be straightforward, but is confused by the pub company’s own references to the pub where they state: “The site of our pub was an ambulance station at the beginning of the 20th Century, but its place in history was secured when one of the first electric ambulances was stationed here in 1909. At night time and Sundays this one vehicle served the entire city”. However, at the top of the pub is the year 1873, and the building does look purpose built as a pub.

Checking newspaper records for the beginning of the 20th century, and there is clearly a pub here. For example in 1902 a report of £1 being collected for charity at the Magpie Hotel, New Street, Bishopsgate, and in 1912 there was an advert for a Housemaid and assistant at the bar of the Magpie, New Street. The 1894 Ordnance Survey map also shows a Public House in the same location as the Magpie.

There was also a pub on the site prior to the year 1873, when I assume the current building was built.

I wonder if the confusion is down to the building directly behind the Magpie. Bishopsgate Police Station extends from where the front of the building is located on Bishopsgate, all the way back to New Street, where the street curves left past the Magpie. It may be that the ambulance was based there, at the rear of the pub rather than at the site of the pub, which from records was clearly a pub from 1873 to the current day.

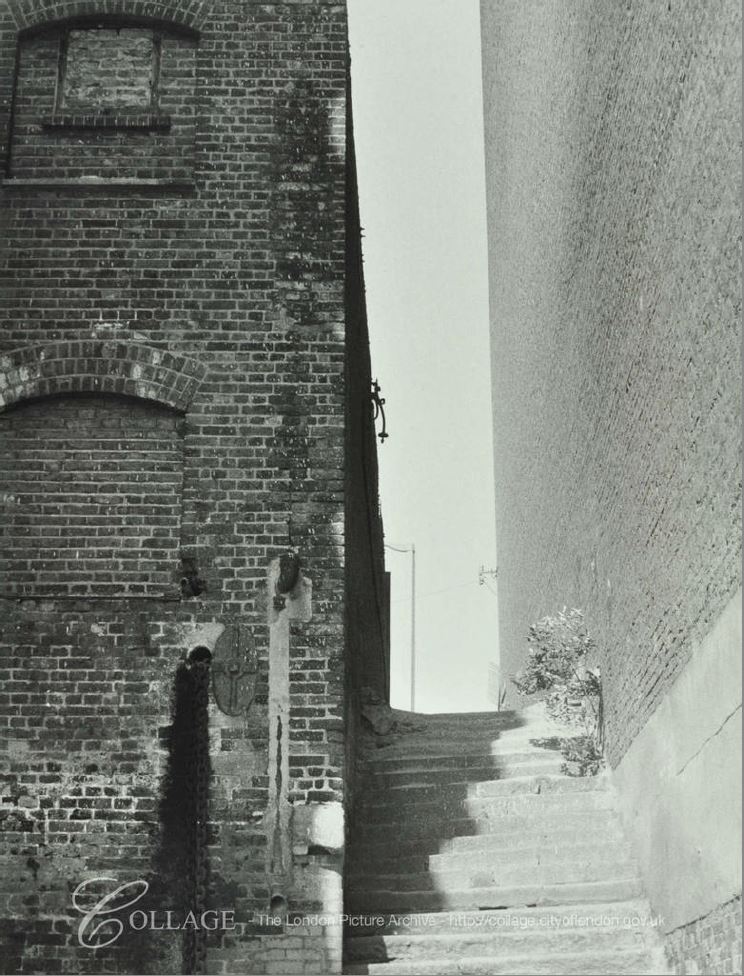

One of the joys of wandering around London is finding things in the most unexpected places. New Street is a dead end for traffic, however at the end of the street Cock Hill provides a walking route down to Catherine Wheel Alley.

Cock Hill is a very quiet alley, but on the side of one of the buildings is a wonderful bit of art:

A large blue cockerel above an entrance to one of the buildings. The tile to lower right has the date 1991, and if I have interpreted correctly, the initials W.N.

I have not been able to find who created the work, and why it is here (apart from the obvious association with the name of the alley), but it brightens up an alley surrounded by tall buildings.

Then back to Middlesex Street, which I followed south to:

Hoop and Grapes – Aldgate High Street

My next pub is the first of two Hoop and Grapes in the City of London, and I suspect why the Kings Stores changed name from the original Hoop and Grapes. The original reason for pubs having such graphic names was to ensure people (many of whom were illiterate), knew where to go. If you said to someone “I will meet you at the Hoop and Grapes” you did not want any confusion as to which one.

The Hoop and Grapes has foundations going back to the 13th century. There are various dates for the main building with both the 16th and 17th Centuries being claimed. Pevsner provides a date of the late 17th century for the pub, however I suspect at that time, buildings were not often completely rebuilt, but use was made of any features worth keeping to keep costs down.

The Hoop and Grapes in 1961, when before or after a beer, you could also get your eyes tested at the adjacent optician and teeth at “Supreme Denture Service Ltd”.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_001_61_4323

Then along Aldgate High Street, and cut through the alley of Little Somerset Street to find:

Still and Star – Little Somerset Street

The Still and Star is a perfect example of the continual threat to London pubs, and the challenges they face in operating an economic business. There was a threat to the pub from development in 2016, however the pub was listed as an asset of community value, which saved the pub from demolition.

The developers appealed and in 2018, the appeal was rejected, however the appeal document showed the potential challenge to the continual existence of the pub.

The appeal findings stated that from 1820 to the 2nd October 2017, the building had operated continuously as a pub, however in October 2017, the tenant vacated the premises leaving a number of unpaid bills. His reason was the lack of revenue, particularly outside the summer months.

I am not sure if the pub has been open since the end of 2017. There is a chalked sign up outside the pub stating that it is closed until late 2021. The Victorian Society had an article dated the 21st March 2019 stating that the Still and Star was again at risk.

The Still and Star is a historic pub, as it was not built as a pub, rather it is a converted house, turned into a pub when licensing was deregulated. The City of London Appeal Findings provide the following source for the name:

“It is believed that the name originates from the premises once containing a still for producing spirit, likely gin, in the hayloft, and the strong associations with the Jewish community around Aldgate and Spitalfields, the star referring to the Star of David”.

No idea what the future will be for the Still and Star. I suspect the reason that the previous tenant left sums up the problem for the pub. Whilst it may be an asset of community value, if it cannot generate enough revenue, who is going to cover the pub’s costs? The developer probably just needs to sit back and wait for time to prove that the pub cannot commercially survive.

Back to Aldgate High Street, and west to find the:

Three Tuns – Jewry Street

The Three Tuns was once a common name for City pubs, however as far as I am aware, this is the only Three Tuns remaining.

A pub has been on the site since the mid 18th century, and the present building dates from 1939. The pub had a brief name change to Hennessy’s in 2003, but fortunately the original name has returned.

The Three Tuns has a section of Roman wall in the cellar which is a very fortunate survival given how many times there must have been building on the site.

The three tuns, or barrels are on display between the first and second floors of the building, which managed to provide a reminder of the original name during the time the pub was Hennessy’s.

Back up to Aldagte High Street, and at the junction with Leadenhall Street, I took the southern branch to Fenchurch Street:

East India Arms – Fenchurch Street

The East India Arms takes its name from the East India Company, who had their offices in nearby Leadenhall Street.

The earliest records I can find of the pub date from 1830 when a meeting at the East India Arms Tavern in Fenchurch Street was mentioned in the London Evening Standard.

It is a lovely brick building which stands in contrast to the surrounding buildings.

The pub sign consists of the arms of the East India Company – which makes sense given the name:

The following photo provides a view along Fenchurch Street to the East India Arms in 1969, and gives an impression of the diversity of shops on London streets at the time.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_010_69_3780

Back to Fenchurch Street and to Fenchurch Street Station, then south into the:

Ship – Hart Street

The Ship is a wonderfully ornate pub, which needs some better lighting conditions than on the day of my visit to do justice to the decoration facing the street.

The current building dates from 1887 and is Grade II listed, and as with the majority of City pubs, there was a pub on the site prior to the current building.

Just above the central ground floor window of the pub is a carved shell, with the words Jubilee Year and the date 1887. A reminder that the year the pub was built was also the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria.

The decoration on the pub is wonderful and fully justifies the Grade II listing.

A quick detour up New London Street from Hart Street:

The Windsor

My intention was to photograph what might be called the traditional pubs in the City, however I have included one very new pub, if only to show how some sites retain their use over very many years, despite the area changing considerably.

This is The Windsor in New London Street:

Just to the right of the top of the steps on the left of the photo is Fenchurch Street Station and a pub called the Railway Tavern was originally on the site of the Windsor.

The first references I can find to the Railway Tavern date back to 1854, so perhaps the pub was built as part of the rebuild of Fenchurch Street Station.

The Windsor occupies the lower floors of a modern office block. No idea why it is called the Windsor and has a picture of Windsor Castle on the pub sign. It is not as if trains from Fenchurch Street run to Windsor.

Back to Hart Street, and east to where the street turns into Crutched Friars, and:

The Crutched Friar – Crutched Friars

The Crutched Friar in the street of the same name, is a pub I have not been able to find too much about.

The name comes from the religious order that established a base near Tower Hill in the 13th century. One of the few City pubs that I have not been in – will have to investigate more once they open.

Keep walking east along Crutched Friars to the:

Cheshire Cheese – Crutched Friars

A short distance along from the Crutched Friar, and on the same street is the Cheshire Cheese which has been built under the railway viaduct of the railway into Fenchurch Street Station,

The railway was built in the 1850s, however a pub with the same name has been on the site for some years before the arrival of the railway. For example, a newspaper advert from the Morning Advertiser on the 4th July 1807: “Wanted for a respectable Public House, a stout active lad, with a good character from his last place. Apply at Mr Chipping’s, Cheshire Cheese, Crutched Friars”.

It is one of the more unusual locations for a City of London pub.

Back to Fenchurch Street, all the way west to Gracechurch Street, then south to:

The Ship – Talbot Court

The second Ship pub on the walk around the pubs of the City of London, but this Ship has a very different appearance. Located in Talbot Court which runs from Gracechurch Street to Eastcheap.

A sign on the front of the pub claims that the Ship was built after the previous pub on the site (The Talbot) was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666. The rebuilt pub was renamed the Ship after the dock workers and deckhands that used to drink at the pub.

On a summer’s day, a very different clientele spill out into the space in front of the pub, but on my walk, it was closed and silent.

Not a single pub was open. If you look at the windows of the pubs, the majority had notices on doors and windows stating they are closed, and that they look forward to welcoming customers back as soon as they can safely open.

The challenge will be whether in a post pandemic world, there are enough customers to keep them all open.

That concludes part one of my walk to find the pubs of the City of London. In part two I continue west and north.

alondoninheritance.com