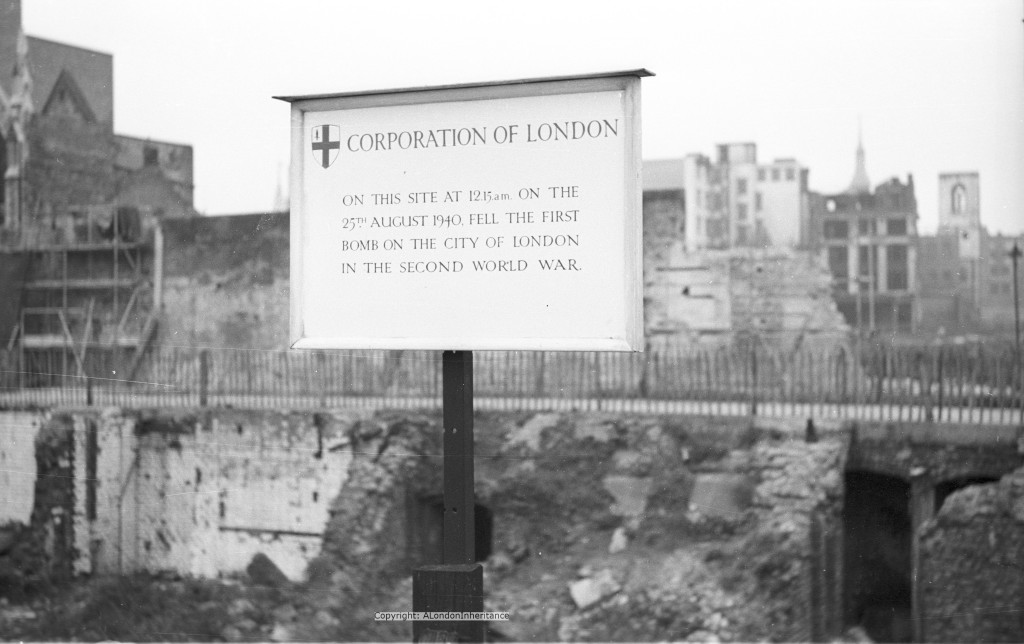

A year ago I wrote my first blog post. It was about the location of the first bomb on central London in the last war, a site in Fore Street commemorated by the sign in one of the photos my father took shortly after the war:

It seemed a fitting place to start a blog where my main focus is to discover how London has changed over the last seventy years, and to learn more about the history of each location.

It has been a fascinating year and I have learnt so much about London by researching the subject of each week’s post.

I would like to thank everyone who has read, commented, provided some additional information, subscribed by e-mail and followed on Twitter. It is really appreciated.

To mark the first year, it would perhaps be a good time to provide some background as to why I started the blog and the photography that I am using to build up a personal view of how London has changed.

As a family, we have a long attachment to London. My great-grandfather was a fireman in East Ham, my grandfather worked in an electricity generating station in Camden, but it was my father who was born and lived in Camden during the last war, who started taking photos of London at the age of 17 in 1946. I also grew up listening to family stories about London and being taken on walks to explore the city.

I have had his collection of photos for many years. Not all of the photos were printed, many were still only negatives and have been stored in a number of boxes in the decades since the photos were originally taken.

Film for cameras immediately after the last war was in short supply. The first film he used was cut from 35mm movie film which had to be rolled into canisters before use. When standard 35mm camera film cartridges became more readily available, the film quality also improved with Ilford being a major provider to the retail market.

I have been looking after these boxes of photos and negatives and about 10 years ago started a project to scan all the negatives. The very early ones on the worst film stock were starting to deteriorate so the time was right to begin this work. Due to family, work and other commitments it took the 10 years (and now on my third negative scanner) to complete the series of black and white photos, over 3,500 covering not only London, but also post war cycle trips around the UK and Holland along with his period of National Service starting in 1947.

Some of the storage boxes of negatives:

It was a really interesting project. Seeing long-lost London scenes appear on the computer screen. Never knowing what a new strip of negatives might contain.

It was a really interesting project. Seeing long-lost London scenes appear on the computer screen. Never knowing what a new strip of negatives might contain.

A number of the photos were easily identifiable. Those which my father had printed often had the location, date and time written on the back, but for many there was no location.

Flicking through these photos on the computer, a project to find the locations, understand the changes since the original photo was taken and use this as a means to learn more about this fascinating city seemed the logical next step.

I also needed an incentive to follow this through. A blog seemed a possible method to document the project and attending one of the Gentle Authors blogging courses last February provided the final kick I needed to get this underway.

Photography just after the war was very different when compared with the cameras available today. My father started taking photos using a Leica IIIc camera in 1946.

(Photo credit: By Rama (Own work) [CC BY-SA 2.0 fr (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/fr/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons)

Leica produced these from 1940 to 1951 and apparently they were readily available after the war, brought home by returning solders who had bought them cheaply in Germany. This was the source of my father’s camera.

Unfortunately he sold this in 1957 to purchase a Leica IIIg camera, however this one I still have as he continued to use this until the late 1980’s when he finally bought a new SLR camera. This is his Leica IIIg which I still posses:

The lens on the camera is not the standard for the Leica IIIg, it came from my father’s original Leica IIIc. Lenses on the Leica III range up to and including the “g” model were a screw fitting and compatible throughout the range, so although the camera body of the Leica IIIg was not used for the early photos of London, the lens was from the original Leica IIIc and was used for all the 1940s and 1950s photos in my blog.

The lens on the camera is not the standard for the Leica IIIg, it came from my father’s original Leica IIIc. Lenses on the Leica III range up to and including the “g” model were a screw fitting and compatible throughout the range, so although the camera body of the Leica IIIg was not used for the early photos of London, the lens was from the original Leica IIIc and was used for all the 1940s and 1950s photos in my blog.

I have recently had the camera serviced to fix a sticking shutter, so a future project for the Spring is to start taking photos using the Leica, which, having the same lens as used for the original photos should make it easy to get the same perspective. Not always possible when using a new digital camera with a completely different lens for the current comparison photos.

It will be an experience to be taking photos of the same scene, from the same place, almost 70 years apart and with the photo taken through the same lens.

I have used cameras with inbuilt light meters since my first camera in the mid 1970s. The Leica III range did not have this facility and external measurement was needed in order to set the correct aperture and speed before taking a photo. I still have the Weston Light Meter that my father used for all his photography with both the Leica IIIc and g:

The Weston Master Universal Exposure Meters were made by Sangamo Weston in Enfield from 1939 and provided a method of measuring the light level. The user would hold up the rear of the light meter (which had a light-sensitive cell which generated an electric current proportionate to the intensity of the light), towards the subject of the photo. The meter on the front would then display the light intensity and using the dial below the meter, this reading would be used to calculate the aperture and speed settings for the camera, specific to the scene being photographed.

The Weston Master Universal Exposure Meters were made by Sangamo Weston in Enfield from 1939 and provided a method of measuring the light level. The user would hold up the rear of the light meter (which had a light-sensitive cell which generated an electric current proportionate to the intensity of the light), towards the subject of the photo. The meter on the front would then display the light intensity and using the dial below the meter, this reading would be used to calculate the aperture and speed settings for the camera, specific to the scene being photographed.

With practice it was possible to visually estimate the light level and the settings needed, and some degree of wrong exposure could be corrected when the photo was developed in the dark room. There was both an art and a skill to getting the correct exposure, something I need to try to learn before taking the Leica back onto the streets of London.

Any serious amateur photographer of the late 1940s and 1950s would develop their own photos and my father was no exception (he was also a member of the St. Brides Institute Photographic Society). The lens on the camera also served as the lens on the enlarger which projected the negative onto the paper during the developing process (another reason why he kept the lens from the first camera).

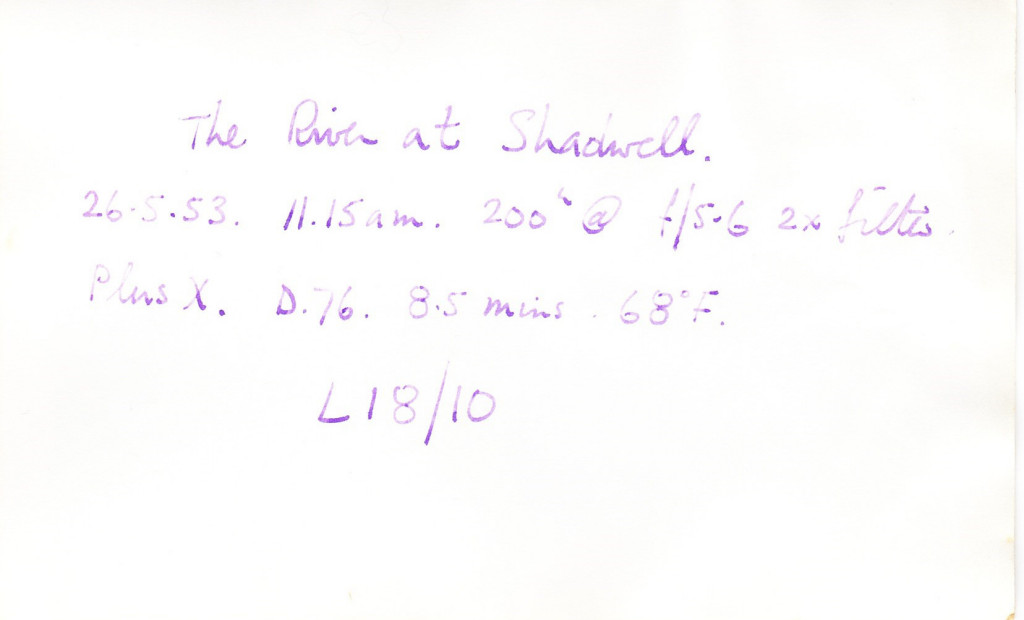

When printing photos, it was useful to record the details, not just when and where the photo was taken, but also the settings on the camera and developer. He recorded this on the back of the photo. The following is a photo of the Thames at Shadwell:

And on the rear is recorded that the photo was taken on the 26th May 1953 at 11:15 am, along with the speed and aperture settings and that a filter was used. On the third line is recorded the film type and the parameters used during developing.

My father continued taking photos of London through the 1980s and 1990s. I have started scanning these and they cover not just central London, but also the Isle of Dogs, north and east London, Greenwich etc. The posts on London Hairdressers and Murals and Street Art from 1980s London are some of the first I have scanned.

I started taking photos of London in the mid 1970s (can an urge to photograph London be inherited?). The photos from the posts on Baynards Castle and a Dragon Rapide over London are some of my early photos.

The first camera I could afford on pocket-money was a Russian built Zenith-E. The only problem with this camera was a random sticking shutter so you would never know whether you would have a good photo until after they were printed. Very frustrating.

My first serious camera was a Canon AE-1 bought on hire purchase in the late 1970s when I first started working.

A job on the South Bank, started in 1979, introduced me to the photos my father had taken when he showed me the printed photos he had taken of the same area just after the war and before the Royal Festival Hall and the Festival of Britain. I think it was from this point that I knew I wanted explore all the photos he had taken. I included some of these photos in last years posts here, here and here.

I switched from film to digital in 2002 and now use a compact Panasonic Lumix and a Nikon D300 and hopefully soon a Leica IIIg if I can master the techniques needed to correctly set the exposure levels.

Digital photography has provided significant benefits over film photography, however having been through the process of scanning these negatives, the earliest of which are almost 70 years old it does make we wonder how many of today’s digital photos will still be usable in 70 years time.

Negative film can be stored cheaply in a shoe box and providing it is not exposed to extremes of heat, cold, humidity and light will last a long time. To view the original photo, it is simply a matter of shining a light through onto a receptive surface, whether photo paper, within a scanner etc.

Apart from professionally archived digital photos, how many personal digital photos will survive the next 70 years? Computer hard disk failures, changes in technology etc. over the next 70 years may well mean that the majority of photos will be lost or unreadable.

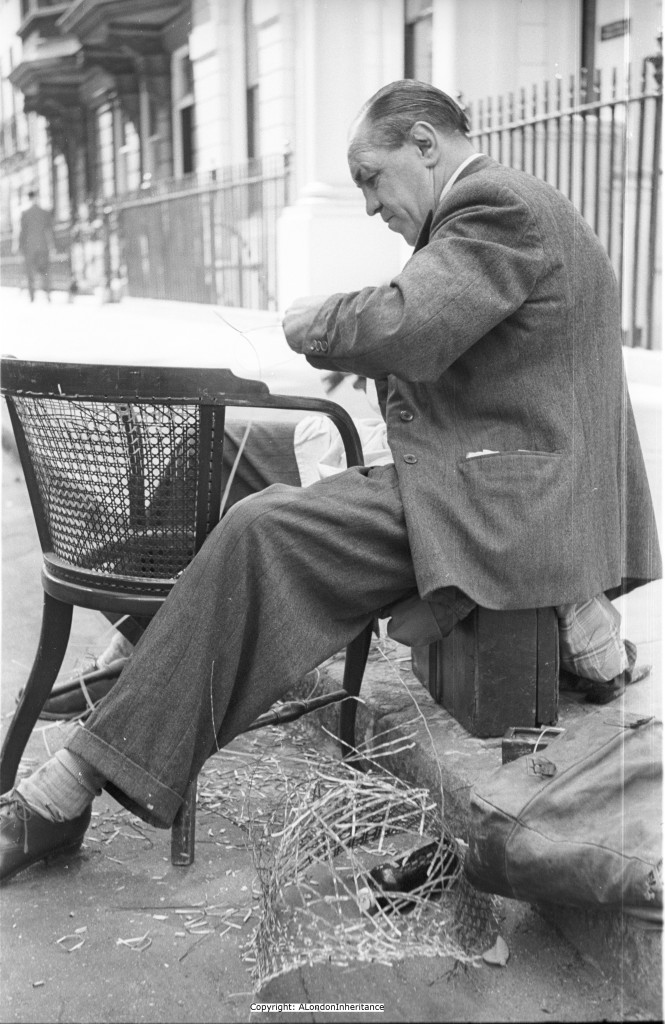

Looking back on the first year of the blog, one of the most remarkable events happened when I published the following photo of a man repairing a chair on a London street:

Thanks to the Internet, the photo was seen by Rachel South who identified him as her grandfather, Michael George South. Remarkably, Rachel is still following the same craft and her website can be found here. The original post is here.

My favourite location from the first year has to be the Stone Gallery of St. Paul’s Cathedral. It was from here that just after the war my father took a series of photos showing the whole panorama of London. The devastation caused by bombing in the immediate vicinity was clearly visible and the City skyline looks very different when compared with today. The full posts can be found here and here, and below is one example of the original photo, looking towards Cannon Street Station with the 2014 photo of the same scene following:

And the same scene in 2014:

Much of the devastation around St. Paul’s was caused on the night of the 29th December 1940. It was fascinating to research the story of the St. Paul’s Watch and the night of the 29th December for posts here and here.

Much of the devastation around St. Paul’s was caused on the night of the 29th December 1940. It was fascinating to research the story of the St. Paul’s Watch and the night of the 29th December for posts here and here.

London continues to change. One of the major projects going through planning approvals during the year was the Garden Bridge. This will have a dramatic impact on the Thames and surrounding areas. I gave my thoughts on this in a post in December which can be found here.

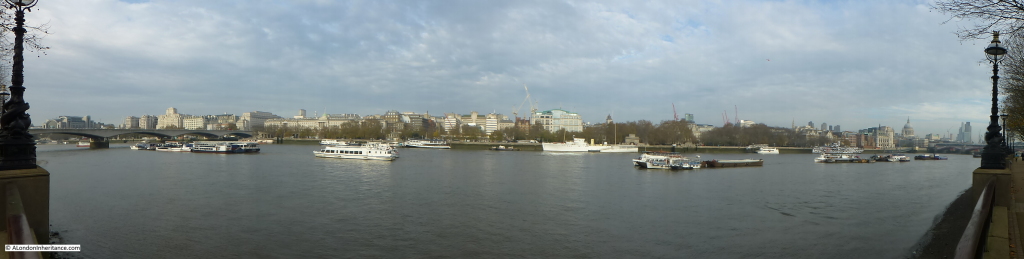

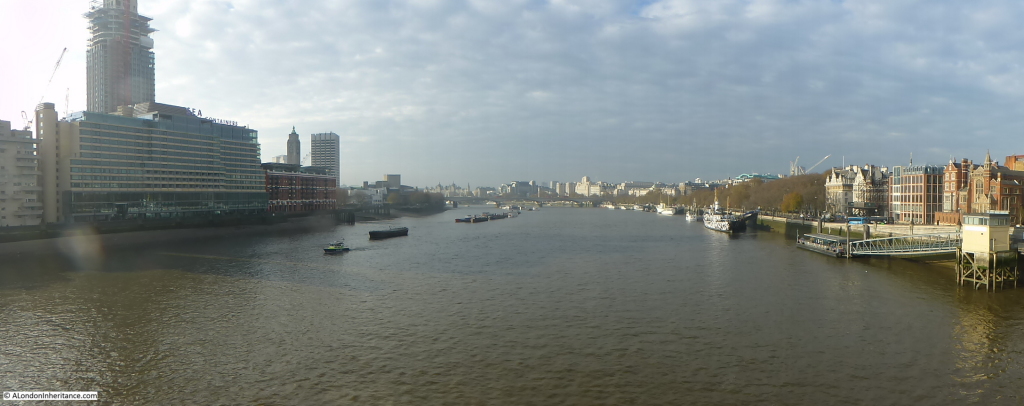

The Garden bridge will have a very dramatic impact on this view from Waterloo Bridge:

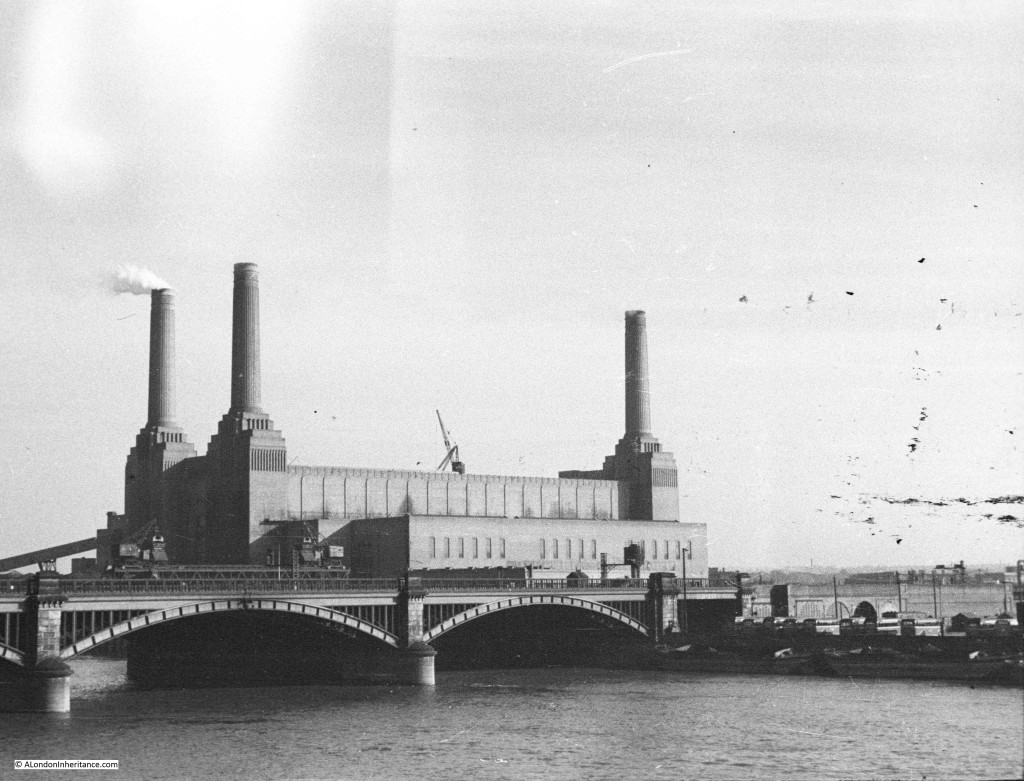

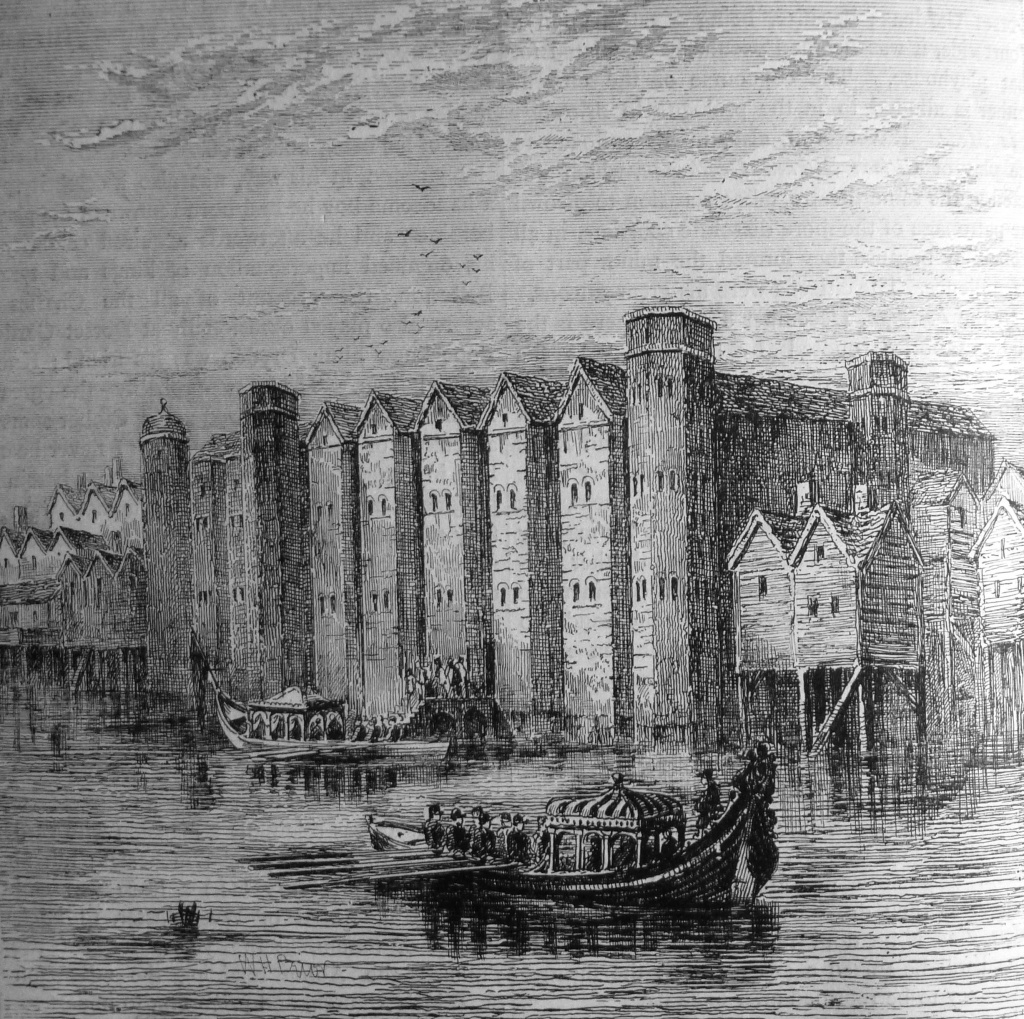

So looking forward to the second year, I have many more places to explore and research. I plan to extend the range a bit further. My father took a river trip from Westminster to Greenwich and there are a whole sequence for photos showing the old docks and wharfs along the river as they were in the early 1950s. Also a series of photos of Hampstead will require a couple of visits to hunt down all the locations from these original photos.

So looking forward to the second year, I have many more places to explore and research. I plan to extend the range a bit further. My father took a river trip from Westminster to Greenwich and there are a whole sequence for photos showing the old docks and wharfs along the river as they were in the early 1950s. Also a series of photos of Hampstead will require a couple of visits to hunt down all the locations from these original photos.

Again, my thanks for your interest in the blog, and if you see someone in the coming year on the streets of London trying to work out how to take a photo with an old light meter and camera, that will be me with the Leica IIIg.