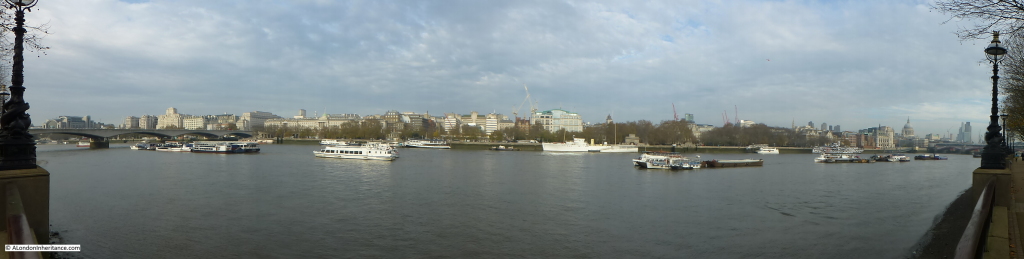

I have long been interested in the history of the South Bank, which for the purposes of this post I will define as the area between County Hall and Waterloo Bridge. I worked there for 10 years from 1979 and it was the location where I first realised that my father had a collection of photos as he brought out some of the photos he had printed to show me what the area where I was now working had looked like some 30 years earlier.

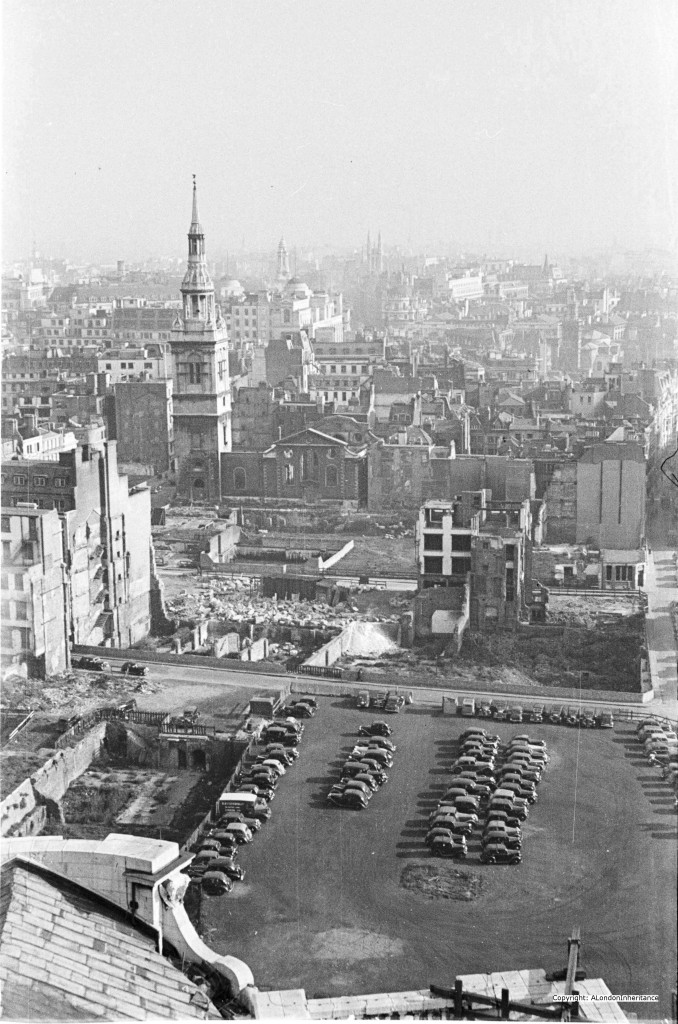

The South Bank has been through two major transformations since the war. The first with the construction of the Festival of Britain exhibition which required the demolition of the whole area between County Hall and Waterloo Bridge (with the exception of Hungerford Railway Bridge which provides a useful reference point).

Following closure, the Festival of Britain site was in turn swiftly demolished with only the Royal Festival Hall remaining, with the rest of the site being gradually built up to the position we see today.

The South Bank was an inspired location for the main Festival of Britain site, a decision which has resulted in the South Bank continuing to be an arts and entertainment centre to this day.

The Festival of Britain was in many ways, a break point between the immediate post war period and the decades to follow. The Festival attempted to define the place of Great Britain within a new world order and looked at how British industry, science, design and architecture could shape that future for the better.

Starting today, and for the next few weeks, I will be exploring the history of the South Bank and the Festival of Britain in detail, starting with three posts covering the South Bank prior to the Festival of Britain.

Then next week, exploring the Festival of Britain at the South Bank, the week after moving to the Festival of Britain Pleasure Gardens at Battersea, then moving onto the Festival’s Architectural Exhibition at Poplar and finally, rounding off with the wider impact of the Festival of Britain.

These are locations and a time in recent history that I find fascinating – I hope you will also enjoy the journey.

A Brief History of the South Bank

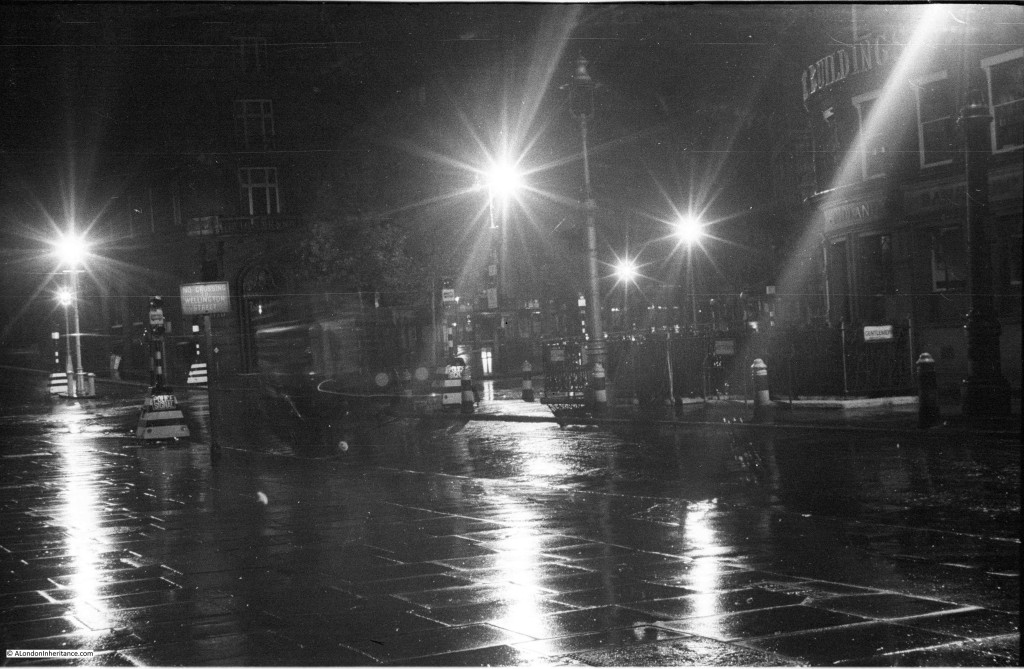

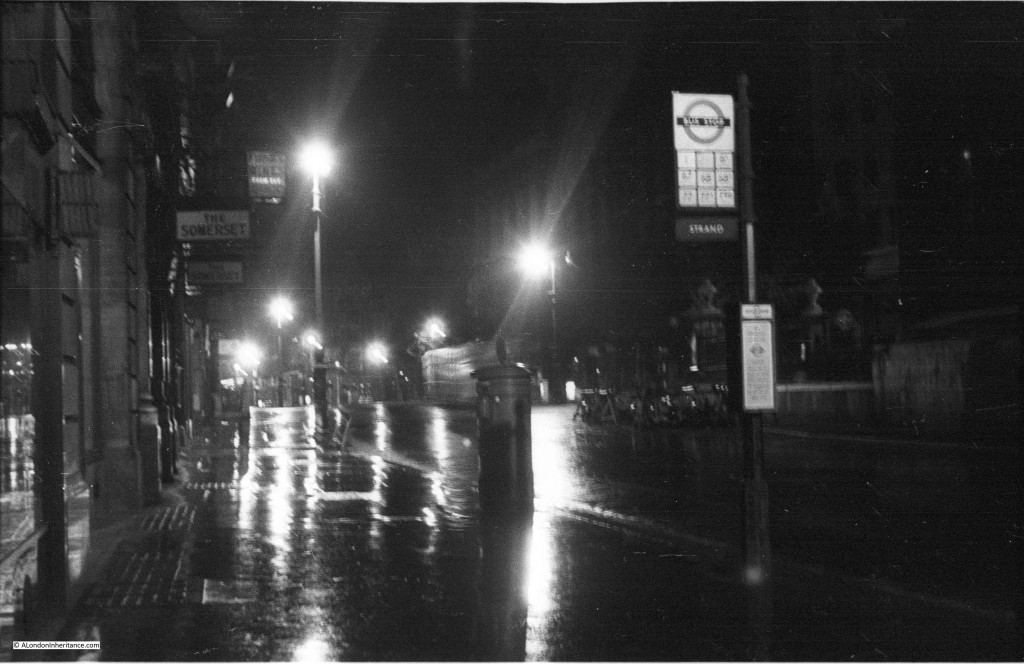

I have published a number of photos my father took of the South Bank over the last couple of years and in the next couple of posts I will take a walk along Belvedere Road and then look at the construction of the Royal Festival Hall using these photos, including a number that I have not published before, but first, some history of the South Bank.

Originally, the river frontage along this stretch of the Thames was mainly marsh land and at times of high tide, water would sweep inland. At some point, an earthen bank was constructed to prevent the Thames coming too far inland and by the Tudor period, a road had been constructed on the alignment of this original earthen bank, although according to Thomas Pennant, in 1560 there was not a single house standing between Lambeth Palace and Southwark. This road was shown on maps as Narrow Wall and today, Belvedere Road is roughly along the line of the old Narrow Wall and therefore also the original wall that formed the barrier to the Thames.

Land between Narrow Wall and the river was gradually drained and a number of small industries grew up along this stretch of the river, with the land behind the Narrow Wall staying as marsh and pasture with drainage ditches taking water into the river.

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the land between the current location of Waterloo and Westminster Bridges, from Narrow Wall to the river was called Church Osiers (Osier being a name for a type of Willow) after the osier bed which occupied this marshy land at the side of the river that would frequently flood. At some point prior to 1690 the land was named Pedlar’s Acre. 1690 is the first time that the name appears in a lease document. The legend behind the name Pedlar’s Acre is that a Pedlar from Swaffham in Suffolk had traveled to London with his dog in the hope of finding his fortune. Different versions of the legend either has the Pedlar’s dog digging up a pot of money either on the South Bank, or after returning home to Swaffham. The Pedlar then gave the strip of land along the river to the parish of Lambeth on condition that his portrait, along with his dog be preserved in painted glass in the parish church.

What ever the truth of this story, there was a picture of the pedlar and his dog in one of the windows of Lambeth Church until 1884.

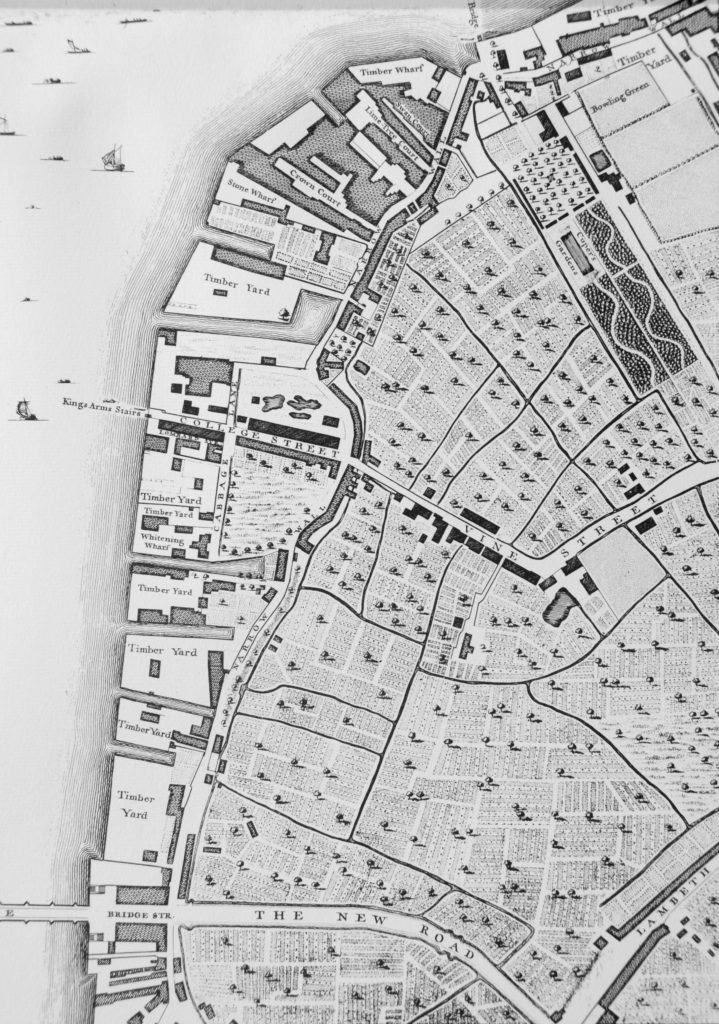

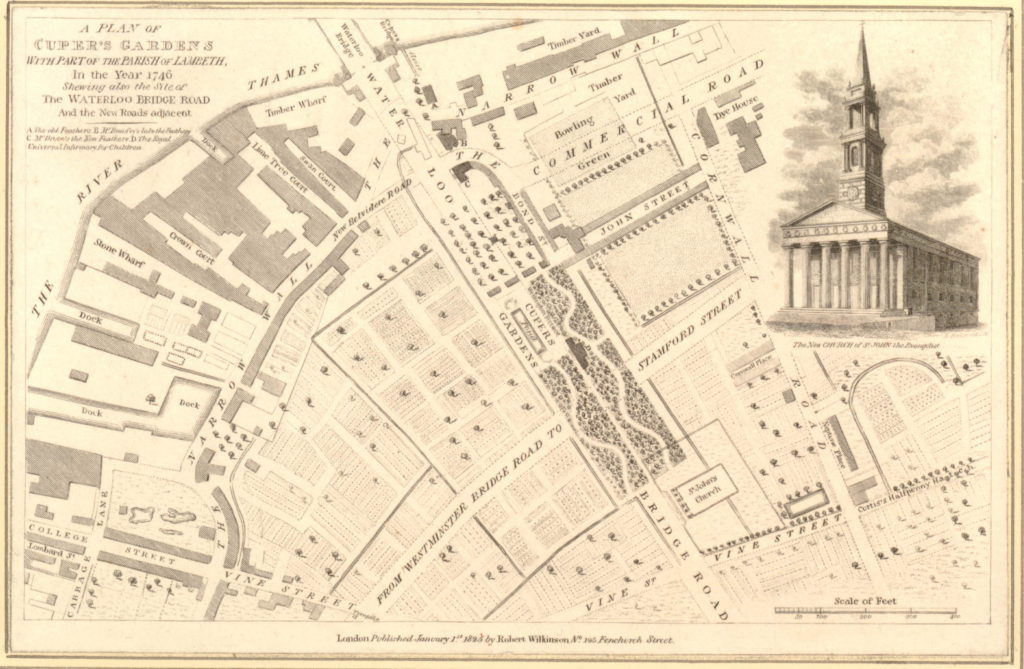

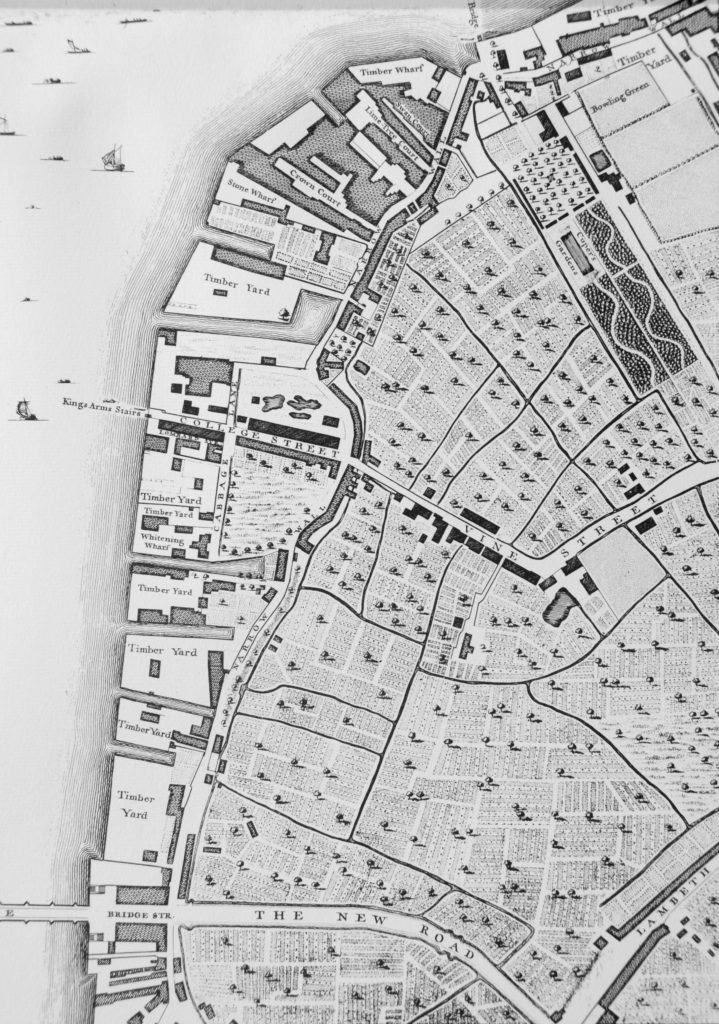

From the 17th century onwards, the land between Narrow Wall and the river was gradually developed. John Rocque’s map shows the area in the middle of the 18th century.

Westminster Bridge is at the bottom of the map and the future location of Waterloo Bridge is at the top of the map, to the left of the bowling green.

Narrow Wall, the original earthen wall, can be seen running parallel to the river, dividing the development along the river from the pasture land that covered much of Lambeth. Starting at the top right of the map, Cuper’s Garden runs in land from the river following almost exactly the route today of the approach road up to Waterloo Bridge.

Cuper’s Garden, one of the many pleasure gardens that ran along the south bank of the river was well known for displays of fireworks and it was also described as “not however the resort of respectable company, but of the abandoned of either sex”. The name came from one Boydell Cuper who had been the gardener to Lord Arundel at his property on the north bank of the river and who rented the land and created the gardens including using some of the old statues from Arundel House.

The land from Cuper’s Gardens along the river went under a number of changes of ownership and names including Bishop’s Acre, Four Acres and Float Mead.

Follow the river south through the wharfs and timber yards that now occupy the space between the river and the Narrow Wall, until College Street.

College Street is on the edge of the current location of the Jubilee Gardens with the open space bounded by College Street, Cabbage Lane and Narrow Wall, called College Gardens part of which is also now the Jubilee Gardens. At the end of College Gardens is Kings Arms Stairs, one of the many stairs down to the river. The curve inland of Narrow Wall at this point was later straightened out, with the inland curve being retained and originally named Ragged Row and then Belvedere Crescent.

The name College Street and College Gardens may refer to the ownership of this parcel of land by Jesus College.

The land after the next Timber Yard and onwards to Westminster Bridge was the future location of County Hall.

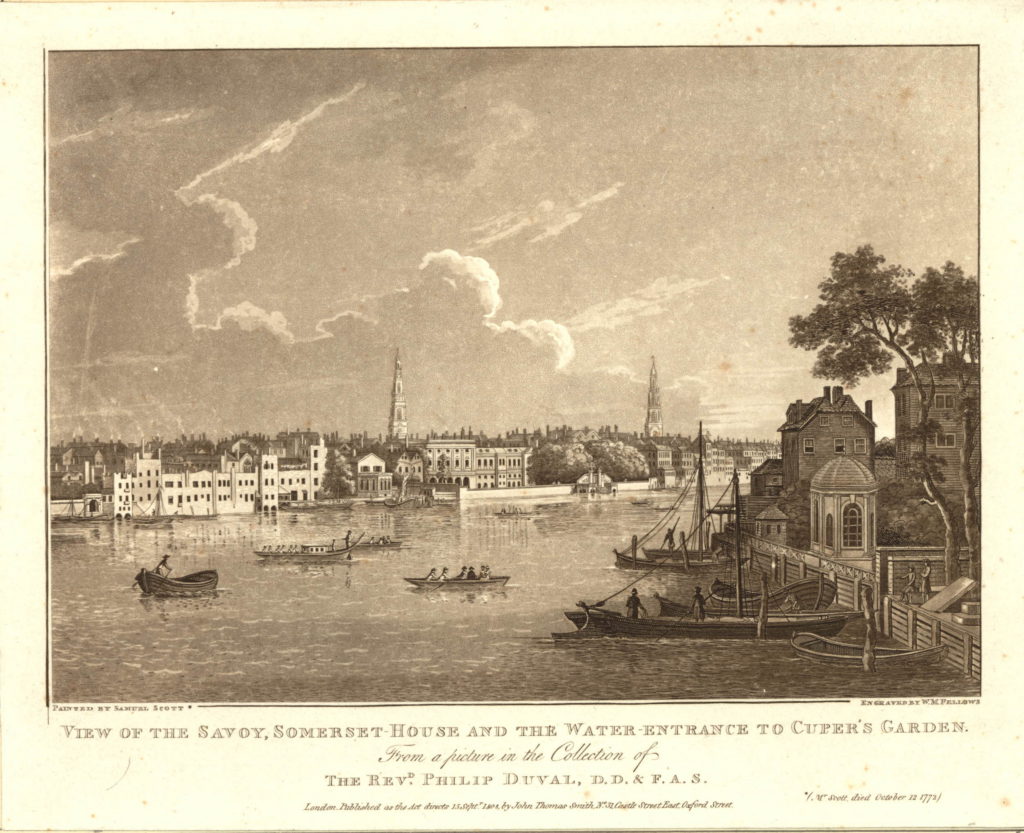

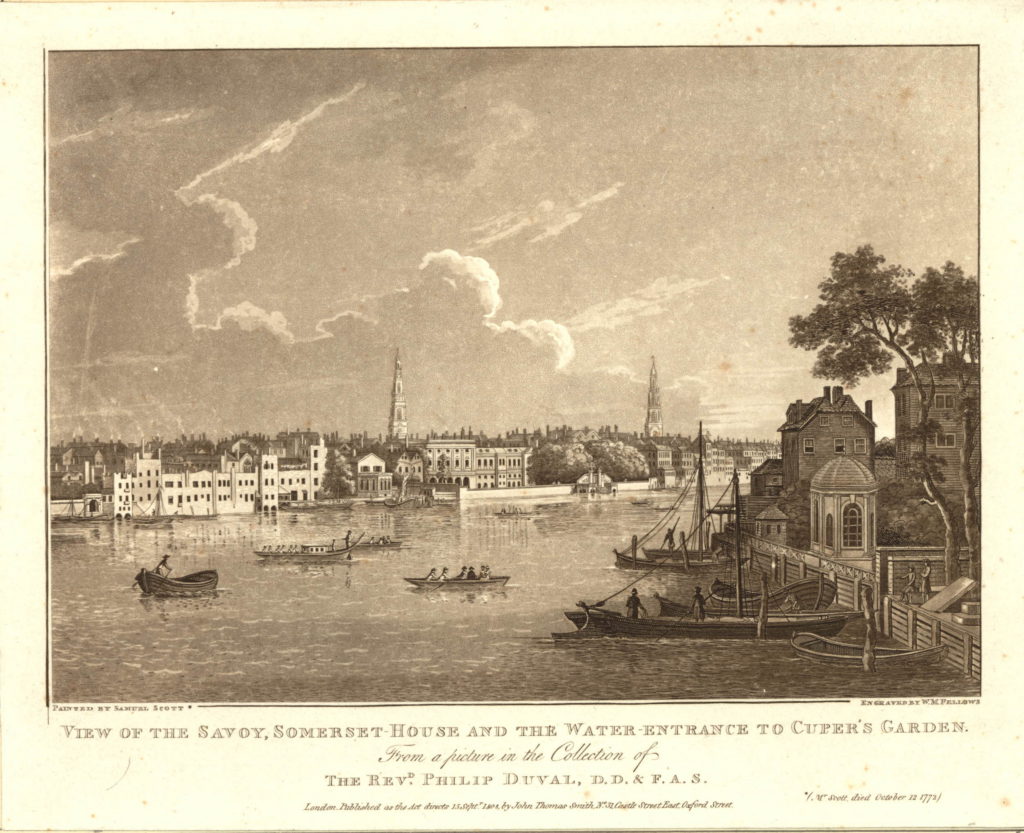

There are a number of prints of Cuper’s Gardens which give the impression of a very pleasant place. The following is from the mid 18th century and is looking across the curve of the river to the north bank, but shows the water entrance to Cuper’s Garden on the right side of the print.

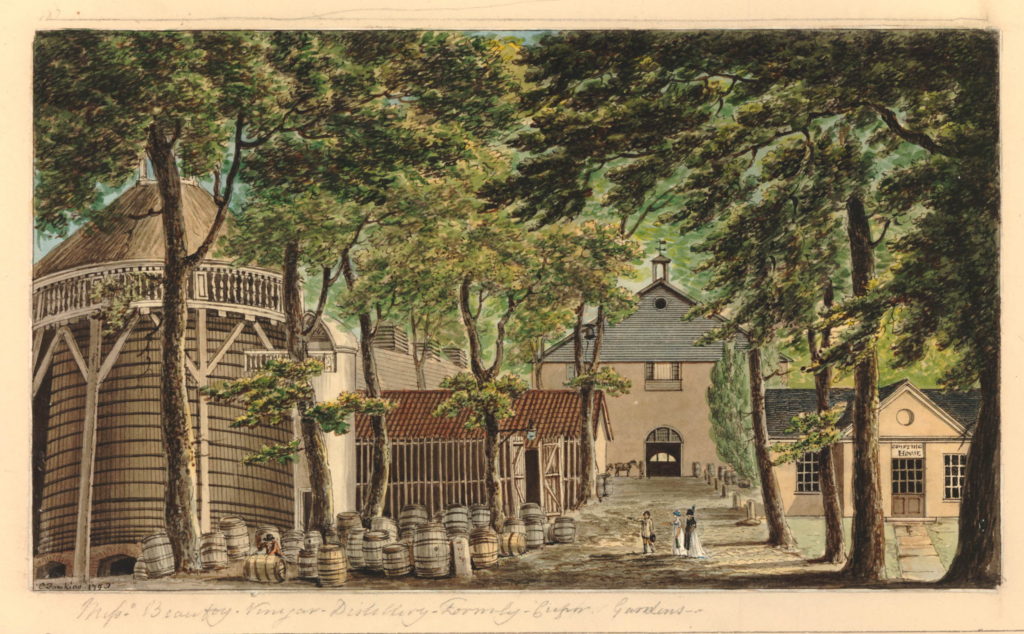

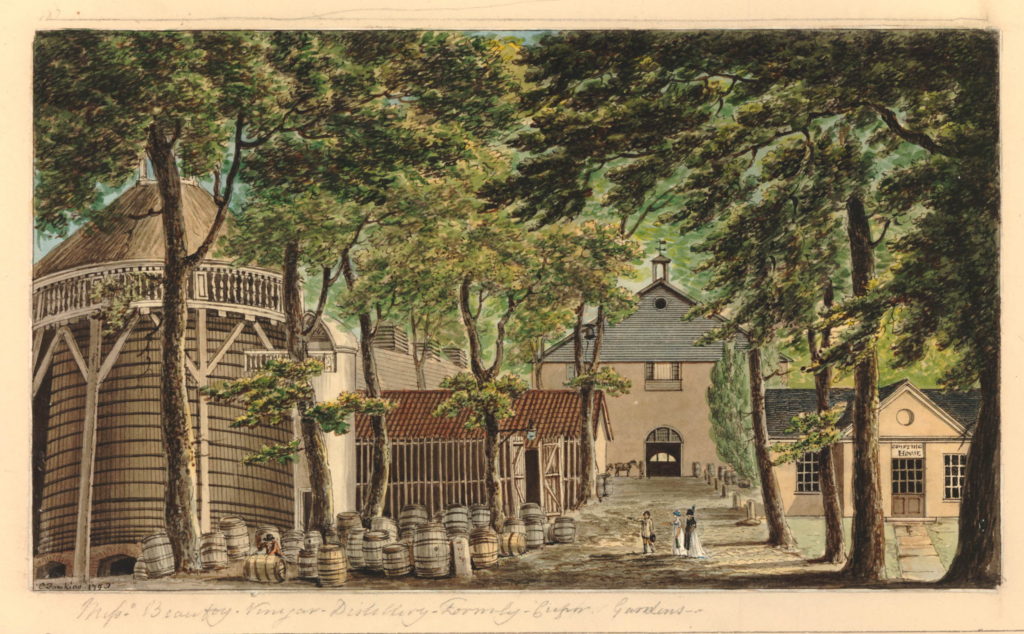

The following print is from 1798 and shows when part of the gardens were occupied by Beaufoy’s Distillery with a large amount of barrels outside. The print gives a good impression of the number of trees across the gardens as it was always described as a wooded area.

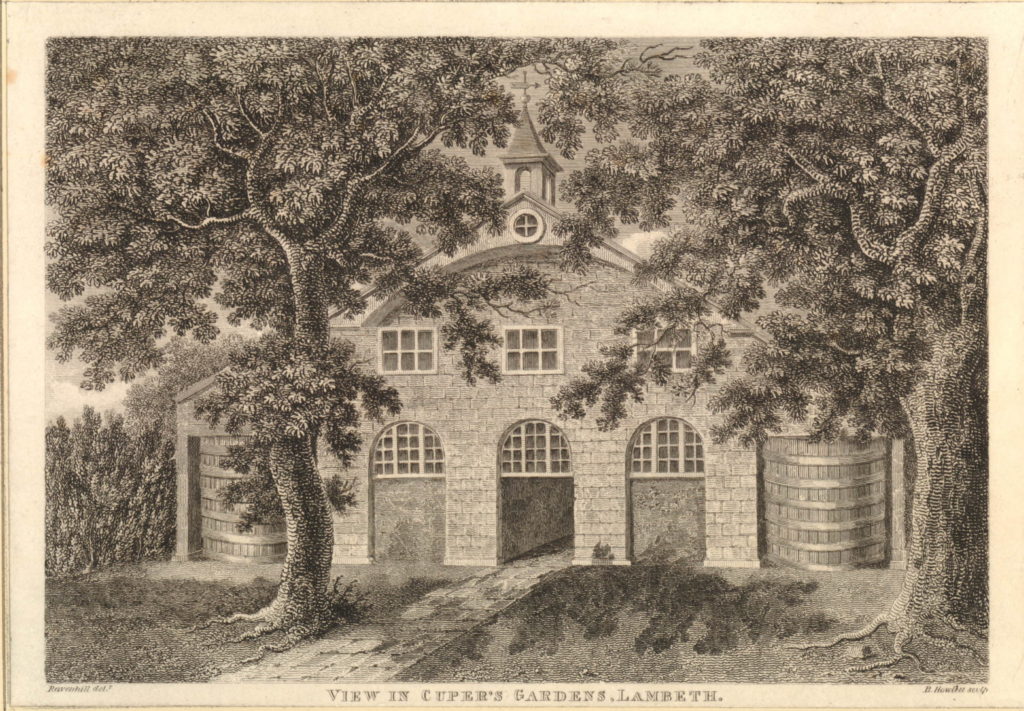

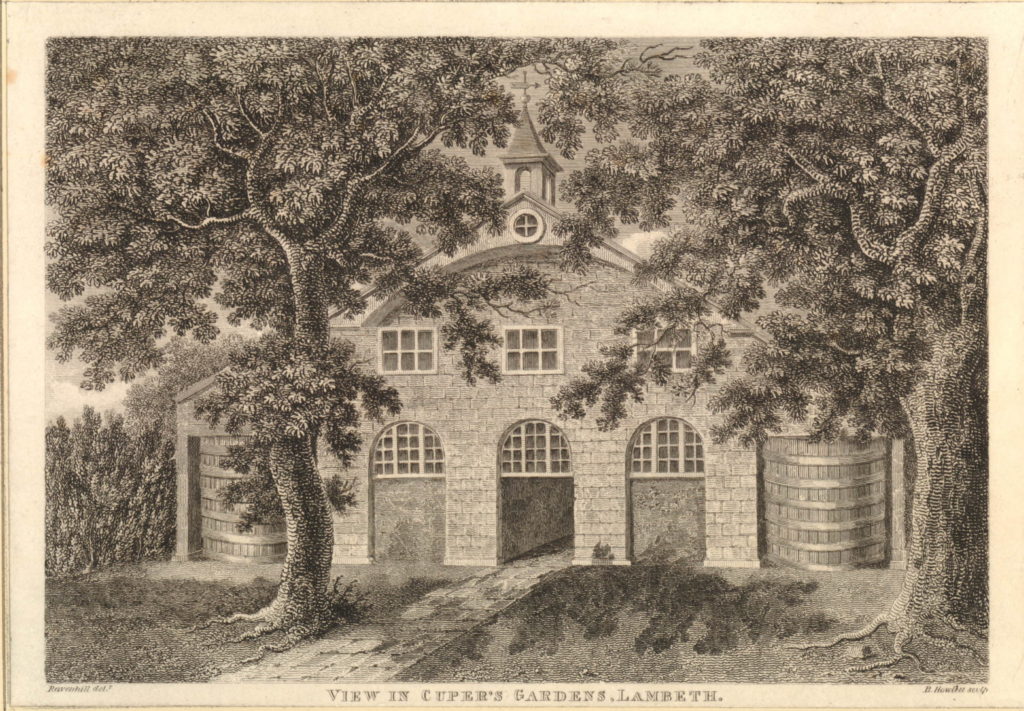

Another view of the Distillery in Cuper’s Gardens.

The next map is part of the “New and Correct Plan of London, Westminster and Southwark” from 1770. This shows the area to be roughly the same with Cuper’s Gardens at the top right of the map and Narrow Wall running down towards Westminster Bridge. This map is interesting as it shows the difficulty with relying on one specific map for accuracy. In the Rocque map, College Street is shown running into Vine Street. In the following map, College Street is now College Walk and Vine Street has changed into Wine Street. These are the only references I have found to these names so I assume that they are errors in 18th century map making.

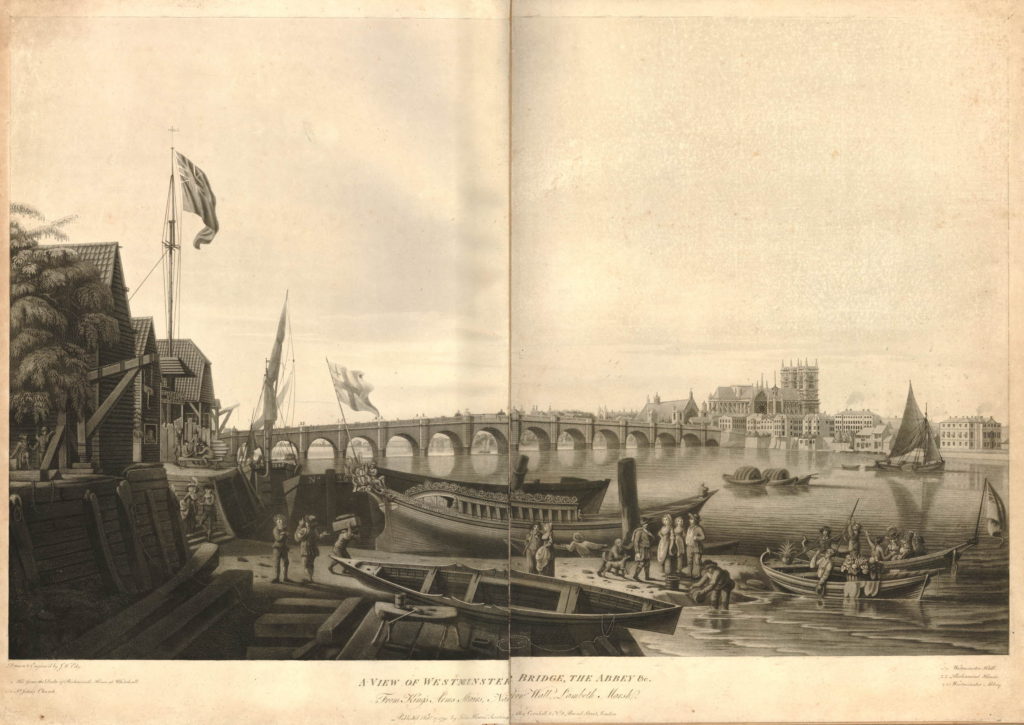

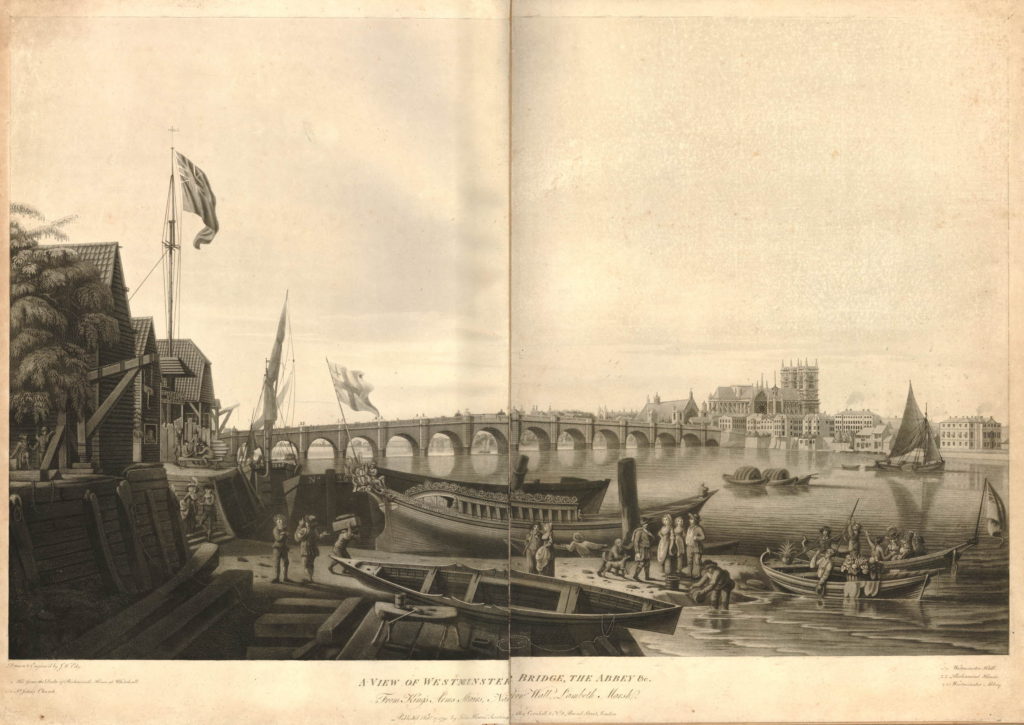

The above map shows the location of Kings Arms Stairs. The following print from 1791 is titled “A View of Westminster Bridge, the Abbey &c. from Kings Arms Stairs, Narrow Wall, Lambeth Marsh”. The stairs can be seen on the left, the tide is low and there is much activity on the waters edge. Westminster Bridge can be seen across the river with Westminster Abbey and Westminster Hall just to the left of the Abbey.

The rest of the scene cannot be a usual scene on this part of the south bank. In the centre of the print is a very ornate boat facing into the river with the flag of the City of London on the stern of the boat. The two small boats in the river to the right have people in ornate dress and large baskets of flowers. It would be interesting to know what was happening. On the left, the building just past the stairs has a sign reading “Artificial Stone Manufactory”, referring to Coade’s Stone Factory which i will cover later in the post.

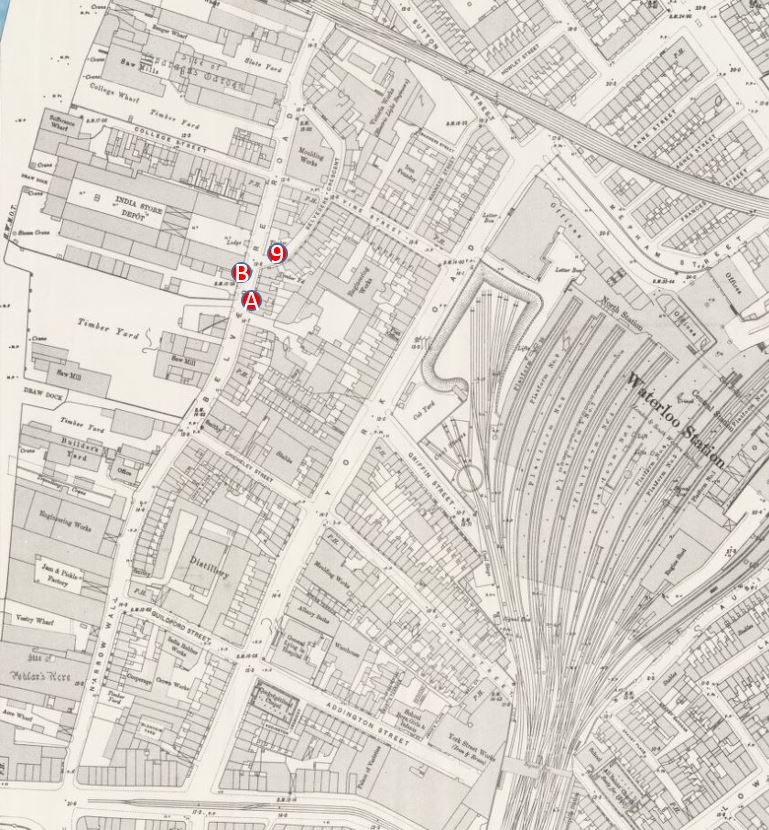

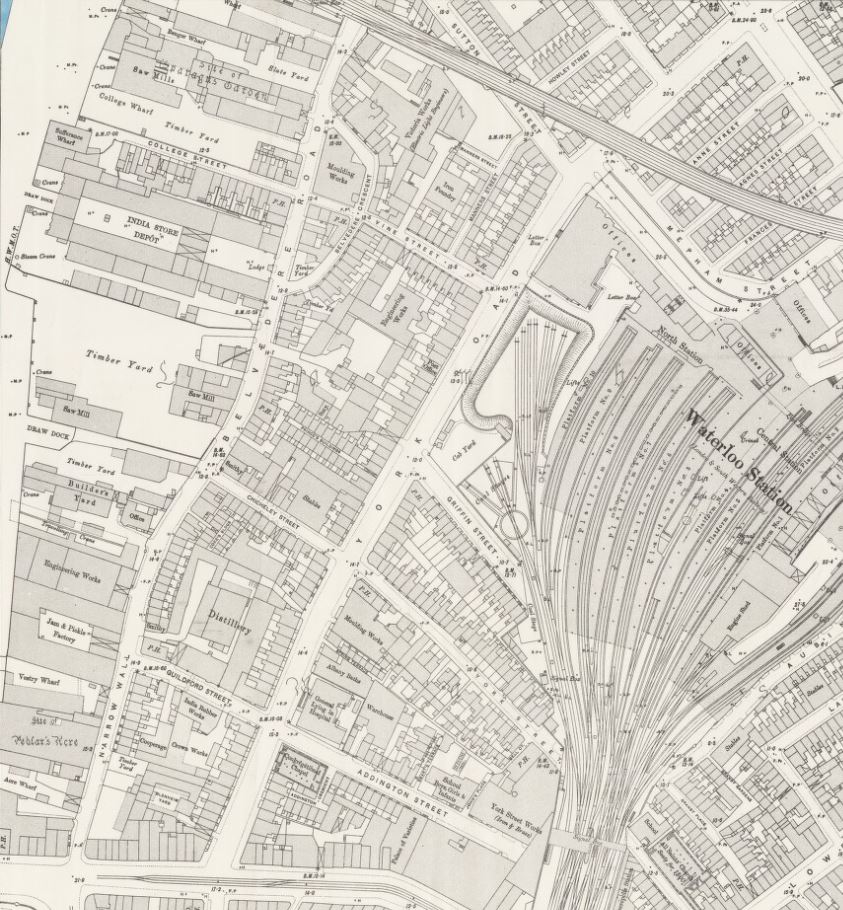

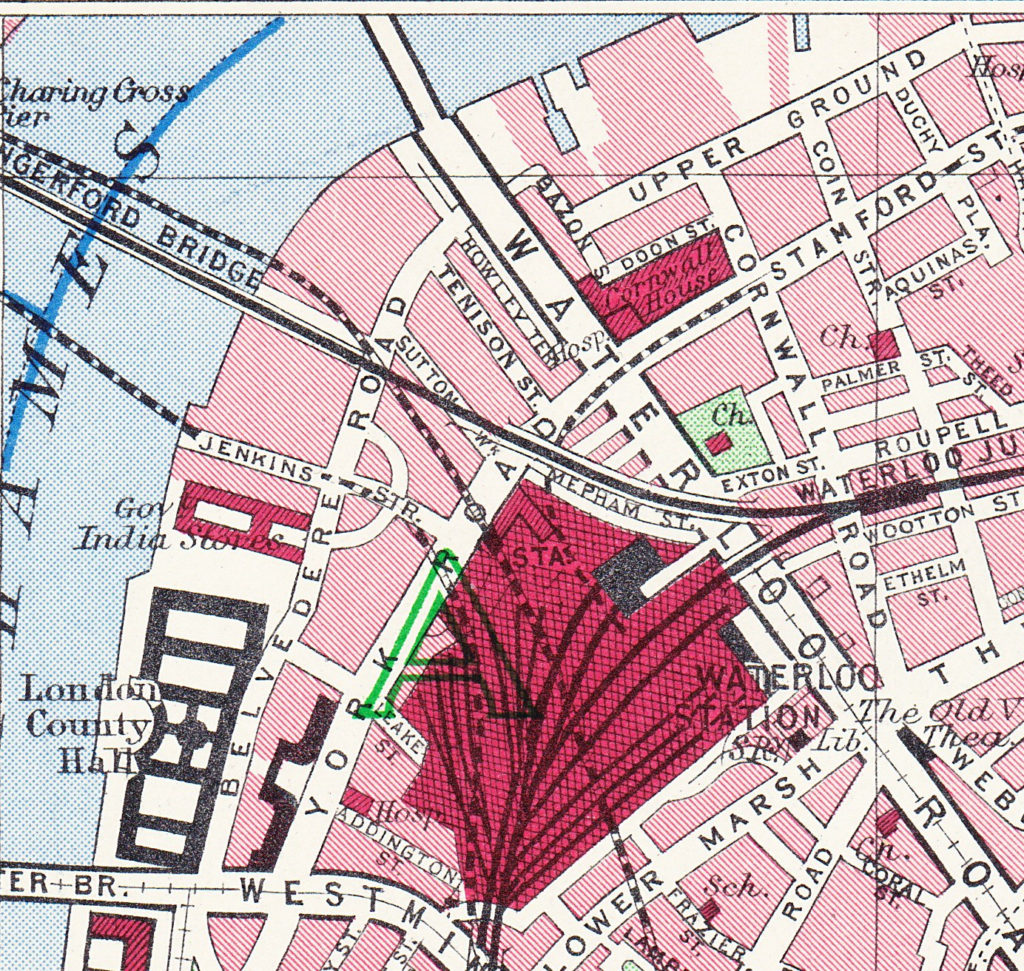

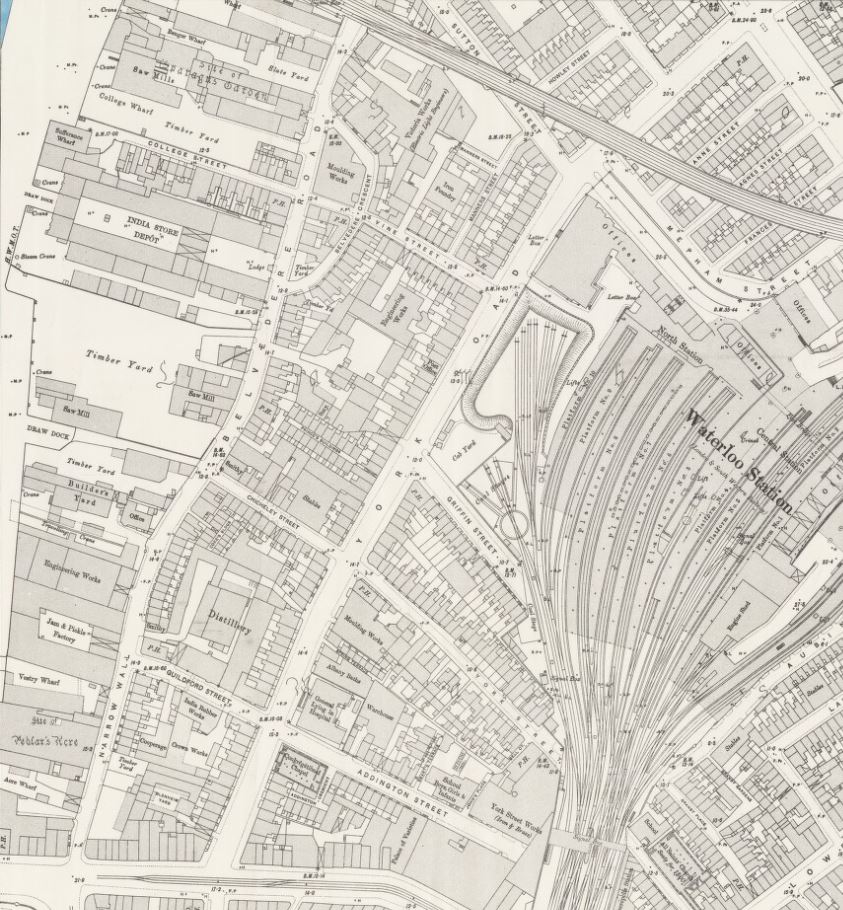

Between the above map of 1770 and the next map, the Ordnance Survey map of 1895, the whole area underwent considerable development.

This edition of Ordnance Survey map splits coverage of the area between two maps, so the following map shows the area between Waterloo Bridge and Hungerford Railway Bridge.

The approach road to Waterloo Bridge still has the name of Cuper’s Garden, retaining a link from when this now heavily built area was mainly pasture land. The Waterloo Bridge approach was developed between 1813 and 1816.

The area inland from Belvedere Road has been developed with rows of terrace houses.

The area between the old Narrow Wall, now named Belvedere Road, and the River Thames is still industrial with two major landmarks, the Iron Works and Shot Tower close to Waterloo Bridge and the Lion Brewery adjacent to Hungerford Bridge. Narrow Wall was widened and straightened between 1824 and 1829 to become Belvedere Road. The source of the name is from Belvidere, a house and grounds on the land south of the Iron Works in the above map. As with many of the other pleasure grounds along the river, Belvidere was opened to the public from 1718 and sold wine and food, including fish taken from the river.

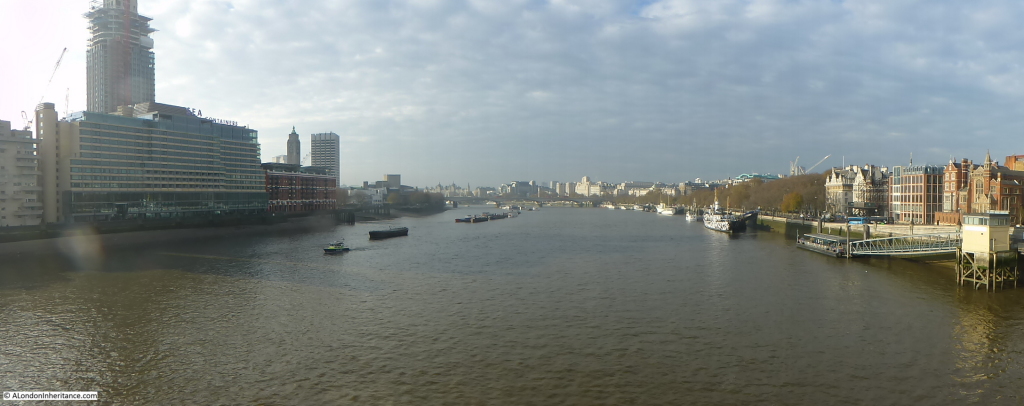

The start of the Hungerford Railway Bridge is shown in the lower left of the above map. Construction of the bridge and the associated railway almost cut the area in two with Belvedere Road now being the main route through the area. If you look back at the Rocque map, Hungerford Bridge was built over the Timber Yard and land just north of College Street.

Designed by Brunel, construction of the original Hungerford Bridge was completed by 1845 when the bridge was opened. It was not originally a railway bridge, the aim of the bridge was to bring more custom to the Hungerford Market on the north side of the river. The original bridge did not last long and in 1859 the construction of a new railway bridge was authorised by the Charing Cross Railway Act. The old bridge was demolished and the new railway bridge was opened in 1864. The chains and ironwork from the old Hungerford Bridge were sold to be used in the construction of the new Clifton Suspension Bridge, also to a design by Brunel.

The original Hungerford Suspension Bridge:

The other major change was the construction of Waterloo Bridge, with the approach road across the former Cuper’s Gardens. Construction of the original Waterloo Bridge commenced in 1811 with the bridge being opened by the Prince Regent on the second anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo in 1817, after which the bridge was named following an act of parliament in 1816 to approve the proposed name.

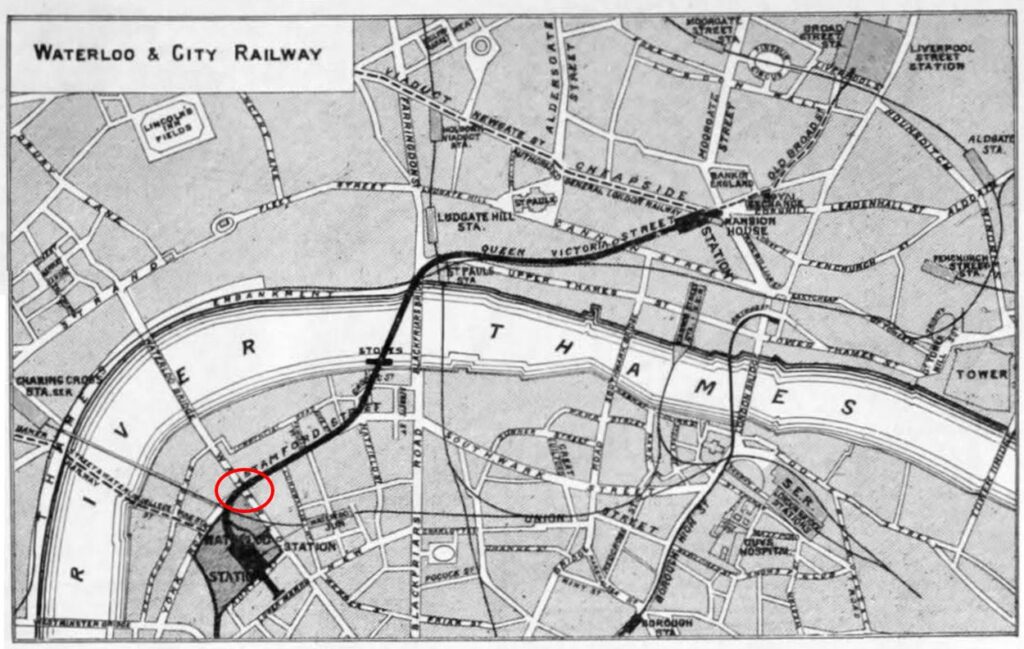

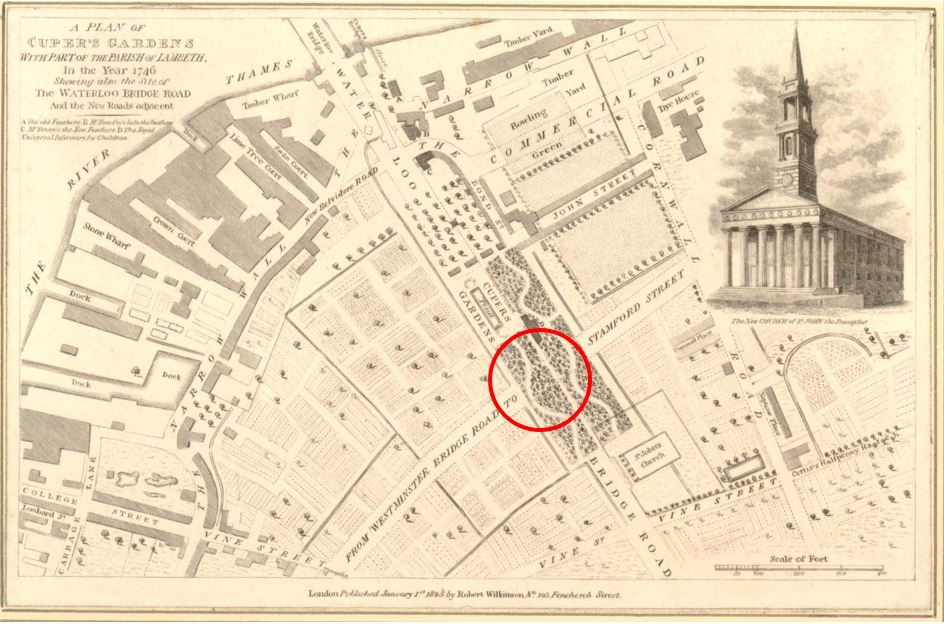

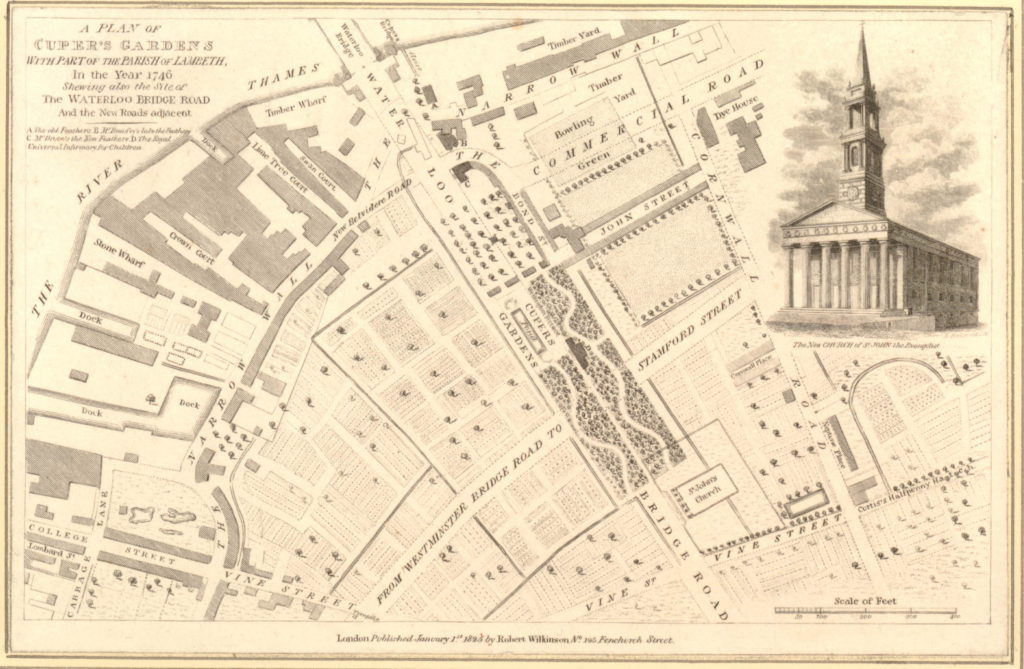

The following map is interesting as it appears to bring together some of the later development around Waterloo Bridge with the area in 1746. Published in 1825, eight years after the bridge was opened, it is titled “A Plan of Cuper’s Gardens with part of the Parish of Lambeth in the year 1746 showing also the site of the Waterloo Bridge Road and the new roads adjacent”.

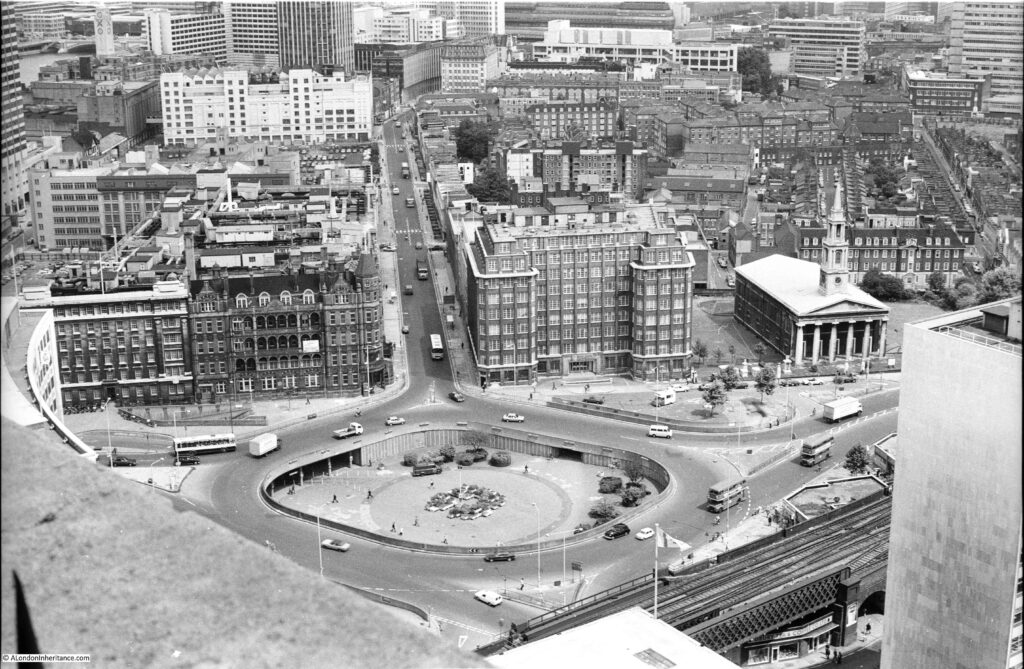

The map helps define the exact location of Cuper’s Gardens as the church of St. John is also shown. The large roundabout at the end of Waterloo Bridge Road is now covering the end of Cuper’s Gardens at the junction with Stamford Street.

The map also shows how the name Belvedere Road came into use. The first straightening of the Narrow Wall is shown close to the approach to Waterloo Bridge and the name for this short section is New Belvidere Road. It is the first reference to the new street name, and also retains the original spelling from the house and gardens. As the name was taken on by the rest of the Narrow Wall, the name changed to the present spelling.

You will need to click on the map to expand a larger version to see the next reference point to the area today. In the gardens in the wooded area just at the bottom right corner of the pond is a building marked D. Checking the key at top left, D is given as the “Royal Universal Infirmary for Children”. This is on an alignment of Waterloo Bridge down to St. John’s Church and although it has now closed as a hospital, a later version of this building, the Royal Waterloo Hospital for Children and Women is still there, on the junction with Stamford Street. This allows us to place the location of Cuper’s Garden precisely and as you walk up towards Waterloo Bridge from St. John’s Church, you are walking through the middle of Cuper’s Gardens.

You will need to click on the map to expand a larger version to see the next reference point to the area today. In the gardens in the wooded area just at the bottom right corner of the pond is a building marked D. Checking the key at top left, D is given as the “Royal Universal Infirmary for Children”. This is on an alignment of Waterloo Bridge down to St. John’s Church and although it has now closed as a hospital, a later version of this building, the Royal Waterloo Hospital for Children and Women is still there, on the junction with Stamford Street. This allows us to place the location of Cuper’s Garden precisely and as you walk up towards Waterloo Bridge from St. John’s Church, you are walking through the middle of Cuper’s Gardens.

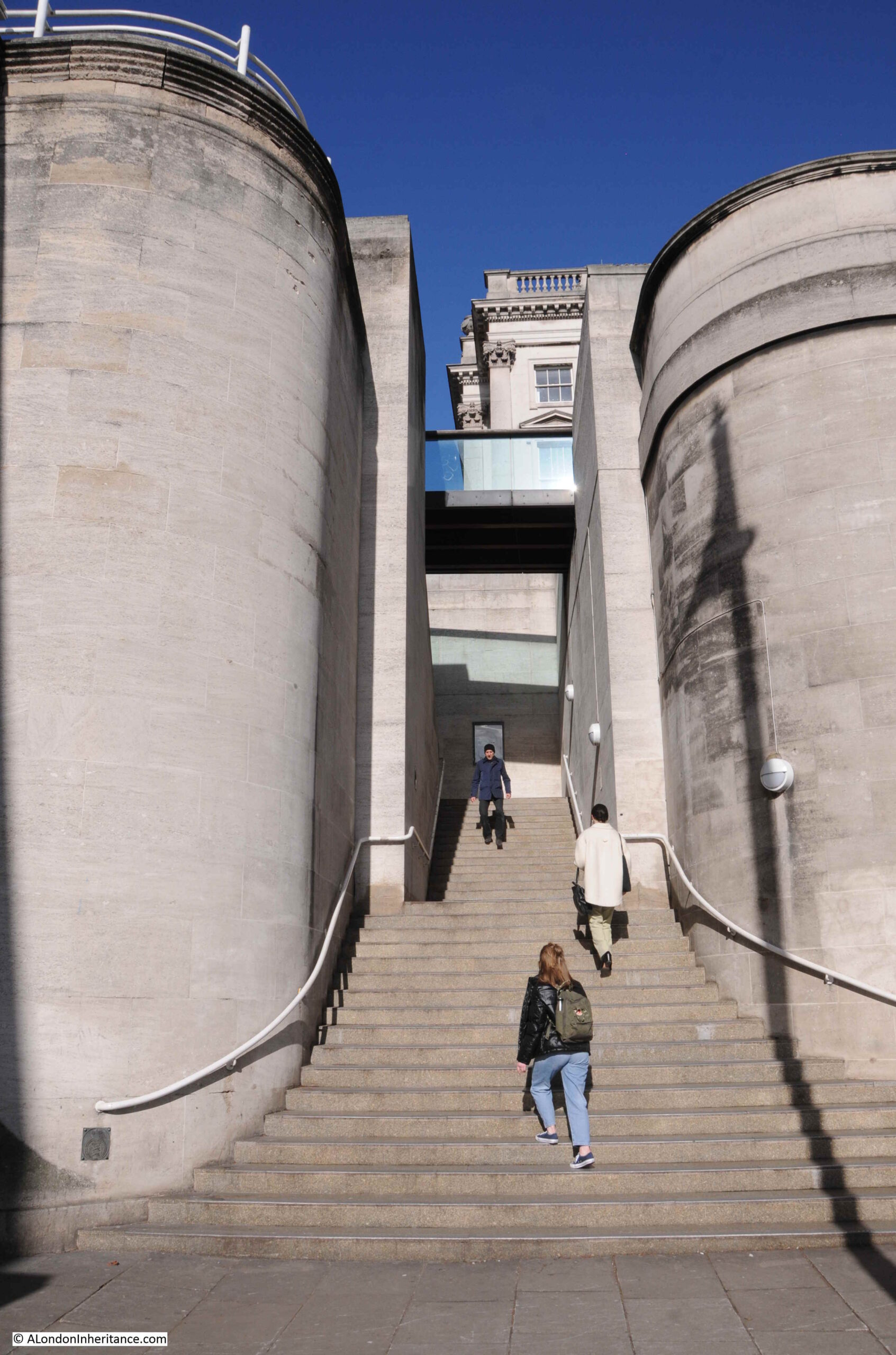

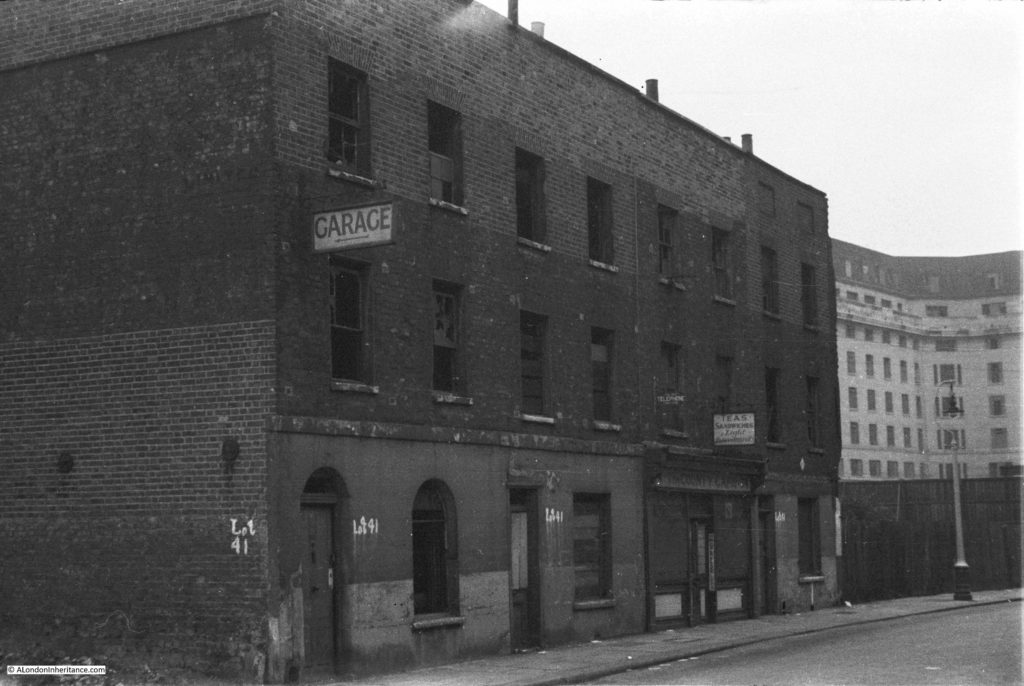

The following photo shows the Royal Waterloo Hospital for Children and Women on the corner of the approach to Waterloo Bridge and Stamford Street.

The church of St. John, although badly damaged by bombing during the last war, it was rebuilt to the original plan and is still exactly the same as the drawing on the 1825 map. During the Festival of Britain, the church was designated as the Festival Church with a programme of events during the period of the festival. The church is at the end of the original location of Cuper’s Gardens, the entrance to the gardens was on the left.

Looking up towards Waterloo Bridge from where the end of Cuper’s Gardens would have been. The hospital and Stamford Street are on the right. The IMAX cinema is on the left in the centre of the roundabout. A very different place to the 18th century gardens.

In 1923, Waterloo Bridge suffered from settlement to the central arch along with subsidence to the carriageway and parapet, leading to the bridge being closed to traffic in 1924. A temporary bridge was constructed alongside Waterloo Bridge and options were reviewed as to whether the original bridge should be repaired, rebuilt or a completely new design of bridge built.

The decision was for a new design of bridge and the Waterloo Bridge that we see today was fully opened in December 1945. The following postcard with a photograph taken from the top of the Shot Tower shows the original Waterloo Bridge with the damage to the central pier, along with the temporary bridge built alongside.

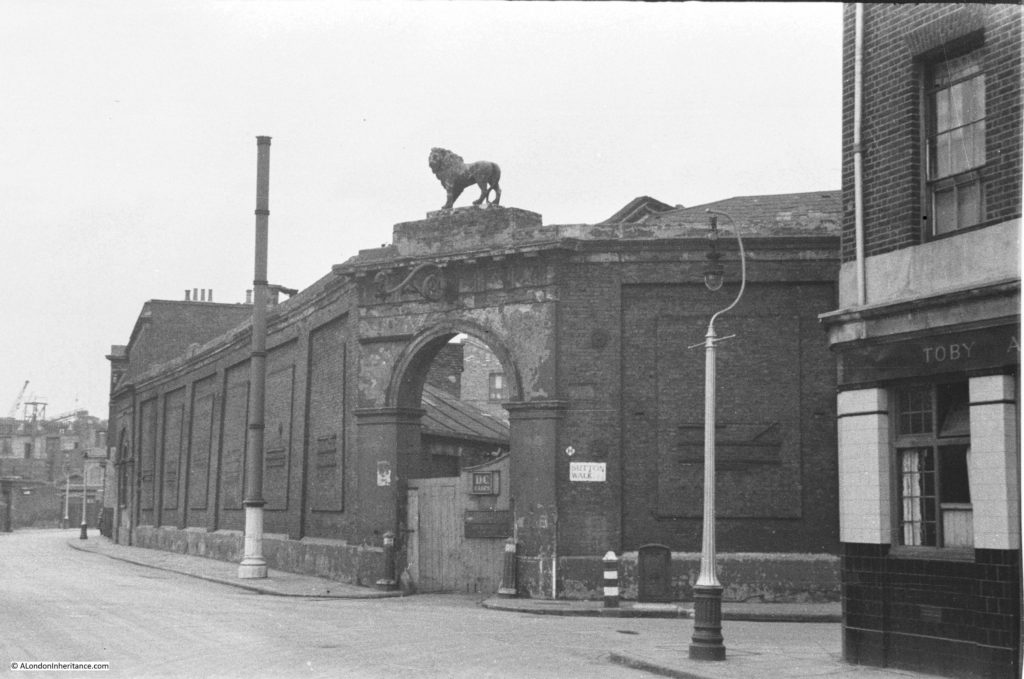

Also in the above map, adjacent to Hungerford Bridge is the Lion Brewery. This area was originally the location of Belvidere House and Grounds, and in 1785, Water Works were built on the southern end of the gardens, drawing water from the river to supply the local residents. Not surprisingly, there were issues with the purity of the water being taken from the river and as part of the general improvements to London’s water supply, the water works were moved to outer London locations such as Surbiton. After the closure of the water works, the lease on the land was assigned to James Golding and the Lion Brewery was completed in 1837. On the opposite side of Belvedere Road to the brewery, Golding purchased a lease on an additional parcel of land and built stables and warehouses to support the brewery.

The Lion Brewery was taken over by the brewers Hoare and Company of Wapping in 1924 and in 1931 the building was badly damaged by fire. It was then temporarily used for paper storage before being demolished in 1949 to make way for the Royal Festival Hall.

During the demolition of the brewery buildings, a total of five wells were found which had been used to provide water for the brewery as water could not be taken from the Thames.

There are a number of prints which show the industry along the South Bank between Hungerford and Waterloo Bridges. The following shows the Lion Brewery. Note the tower of the church of St. John’s in the background.

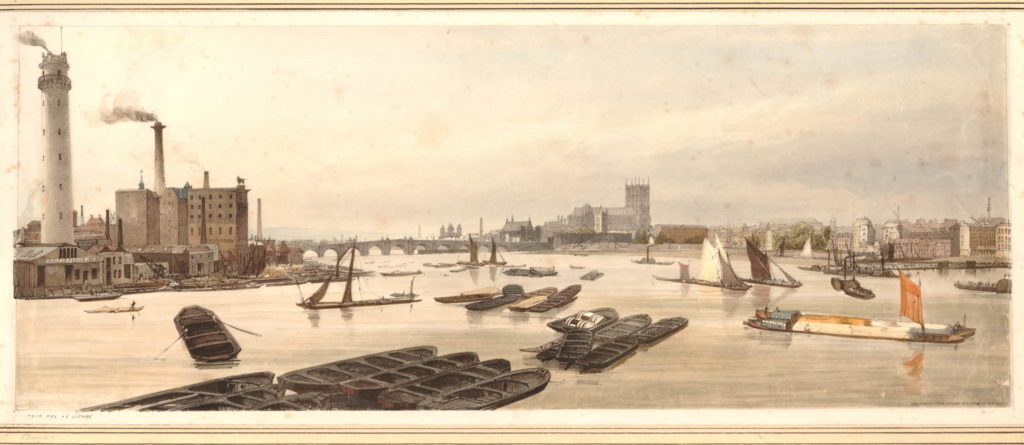

Another print shows both the Lion Brewery and the Shot Tower with the original Waterloo Bridge on the left.

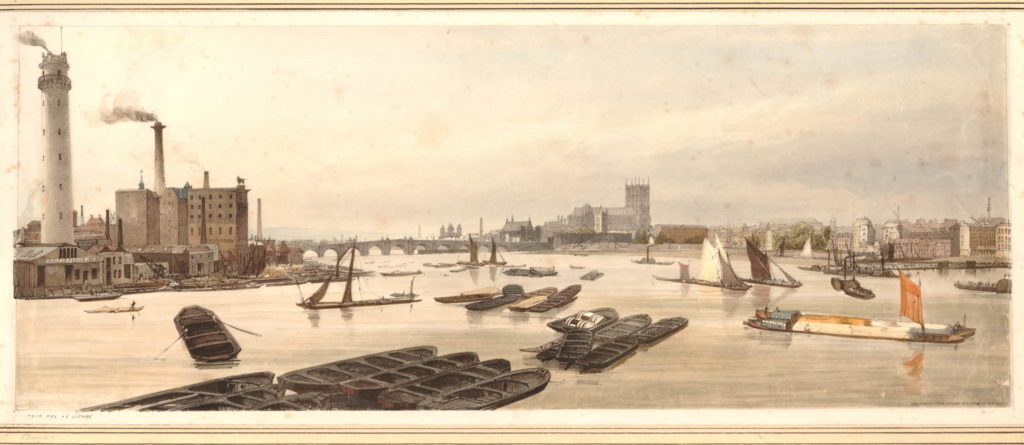

And a view from Waterloo Bridge along the river to Westminster Bridge before the construction of Hungerford Bridge. The Shot Tower and the Lion Brewery are on the left.

The Shot Tower was built in 1826. The gallery at the top of the tower is 163 feet high, and was used to drop molten lead for large shot. A gallery half way up the tower was used to make small lead shot.

The Shot Tower and the associated lead works were owned from 1839 by Walkers, Parker and Company who ran the business until 1949.

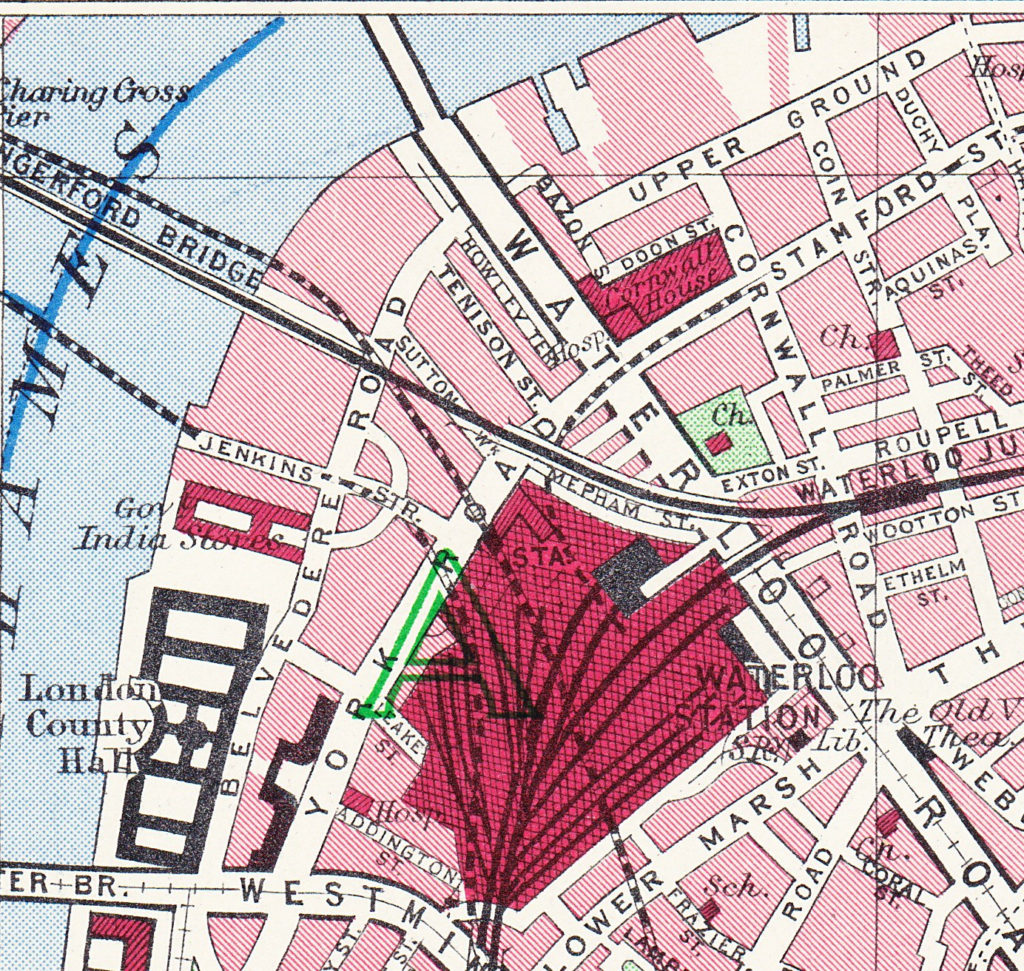

The area between Hungerford and Westminster Bridges is shown in the following map (the map cuts off before Westminster Bridge but if included it would be just at the bottom of the map to the left).

The map shows the straightened Belvedere Road, with the original curve in the road still in existence but is now named Belvedere Crescent. Follow Belevedere Road towards the bottom of the map and at the junction with Chicheley Street, it reverts back to Narrow Wall.

Below the Chicheley Street junction, the whole area between York Road and the river would later be occupied by County Hall. Following the Festival of Britain, the area bounded by York Road, Belevedere Road, the rail tracks and Chicheley Street would be occupied by the Shell Centre building. On the opposite site of Belvedere Road, up to the river, during the Festival of Britain, the Dome of Discovery would be built on the area occupied by the India Store Depot and today the Jubilee Gardens are on this spot.

At the top left of the map is a set of buildings, over which is written “site of Sparagus Garden”. This was also an early pleasure gardens, but unlike Culper’s Gardens, is not very well documented. This was also the site of Coade’s Artifical Stone Works.

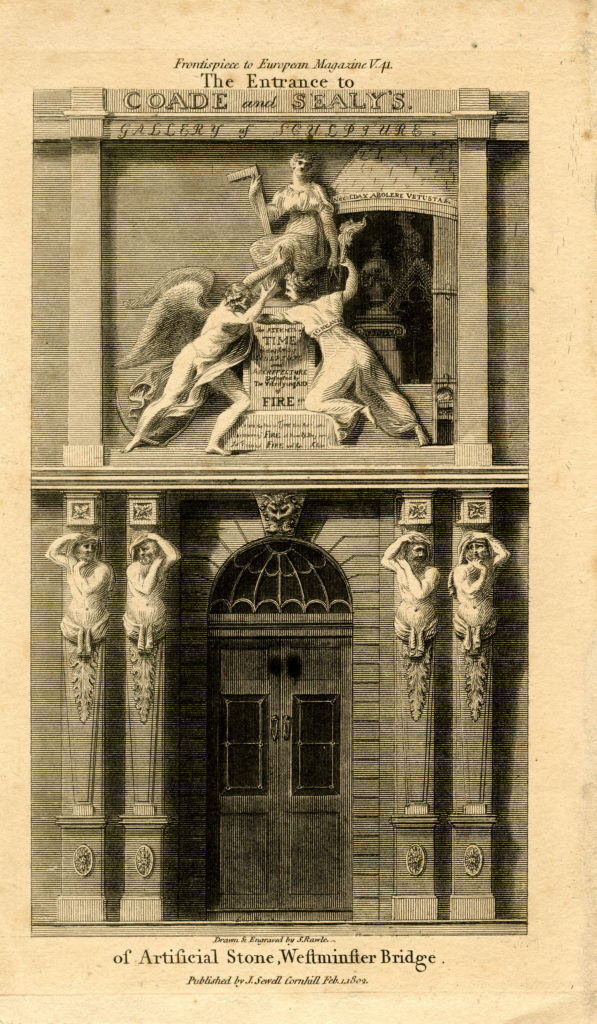

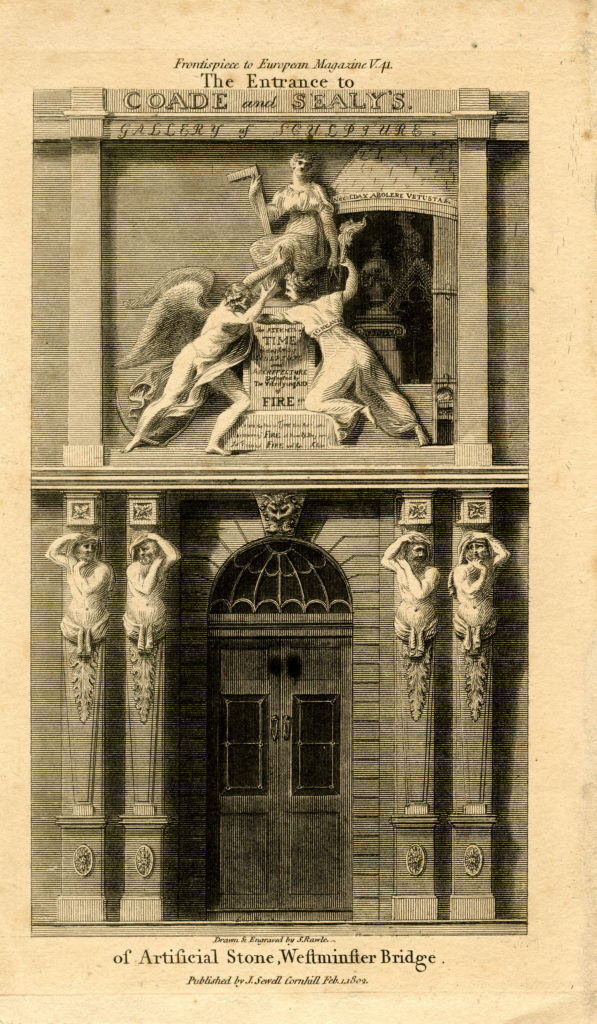

The initial stone works on the site were opened in around 1770 by Daniel Pincot who published that he had opened a factory “by King’s Arms Stairs, Narrow Wall, Lambeth”. At some point soon after 1770, the factory appears to have been taken over by Eleanor Coade who would go on to run the factory for 25 years until her death in 1796 when her daughter, also called Eleanor, took over the factory. The younger Eleanor also ran the business well and opened a gallery for the factory’s products at the corner of Narrow Wall and Bridge Street – the street leading up to Westminster Bridge – along with a number of houses which took the name Coade’s Row.

The entrance to the Coade Stone showroom on Westminster Bridge Street:

Products from the Coade factory were used across London and wider afield, but the most long lasting and well known is the lion that was on top of the Lion Brewery. Removed and stored at the time that the brewery building was demolished, it was installed on a plinth at the southern end of Westminster Bridge in 1966.

The younger Eleanor Coade was unmarried and had no children by the time of her death in 1821, however she had already taken on a cousin, William Croggon to take control of the business, who was succeeded by his son Thomas in 1836, however his ownership of the business did not last long and the Coade Stone Factory appears to have closed a year later in 1837 and the production of this unique, man-made stone was consigned to history.

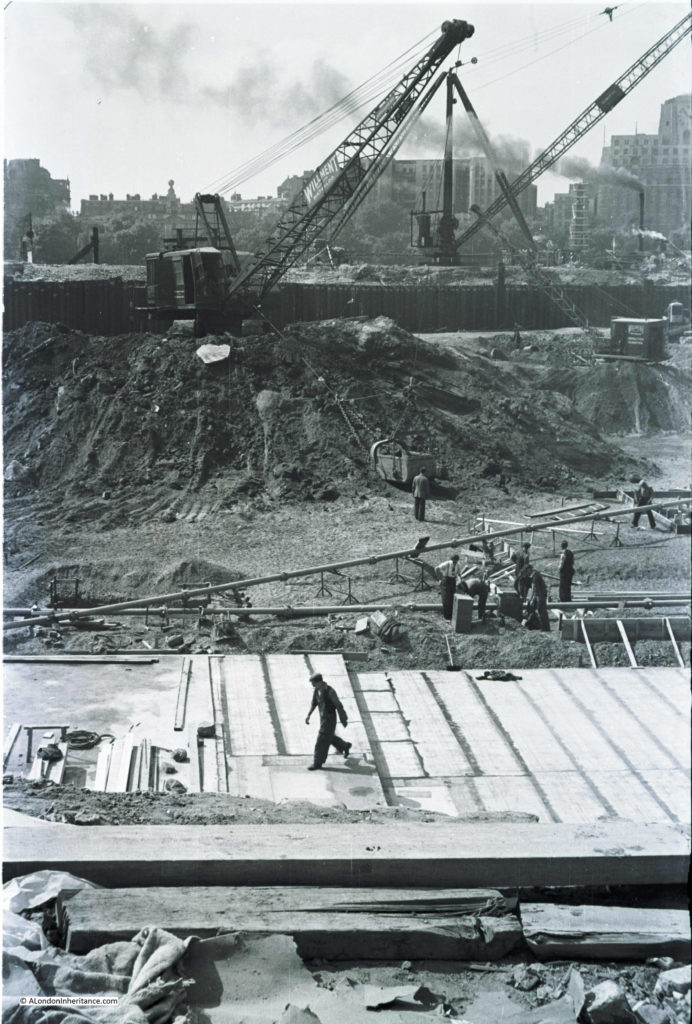

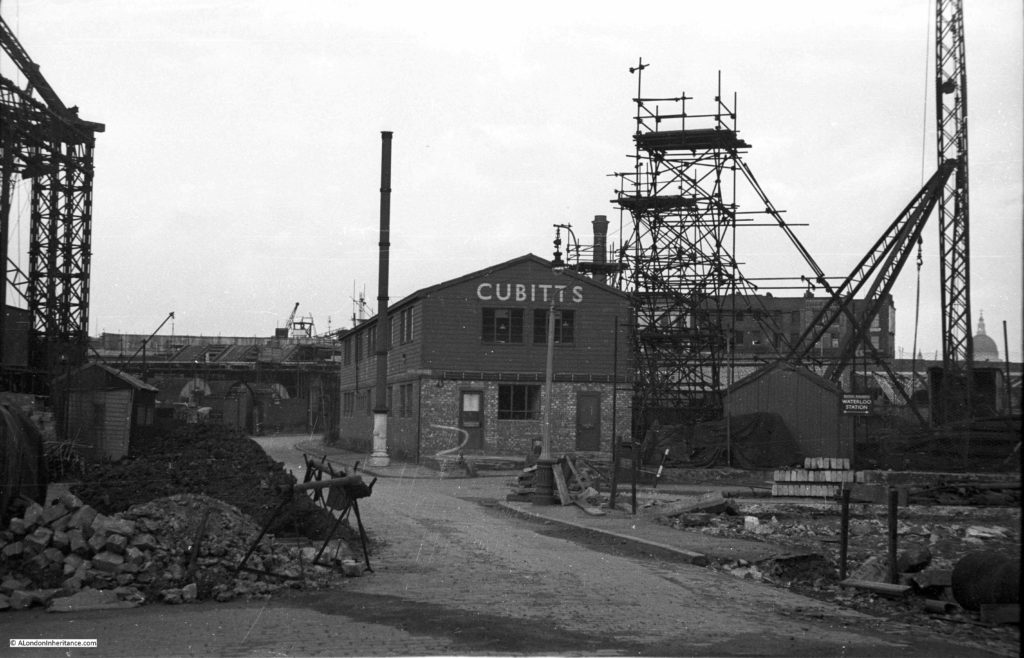

Just to the south of College Street, is labelled the India Stores Depot. This was built in 1862 on land leased by the Secretary of State for India. These stores were gradually extended until the start of the 2nd World War, during which they suffered considerable damage and were demolished to make way for the Festival of Britain.

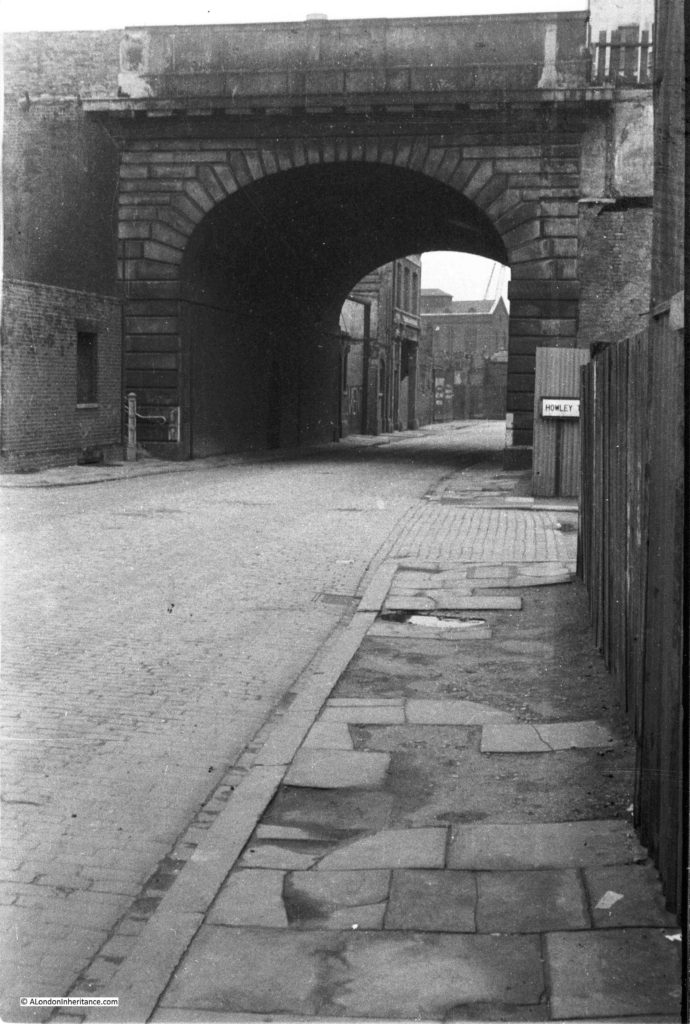

As a final bit of confusion regarding continuity of street names, the following map extract is from the Bartholomew Greater London Street Atlas from 1940. It shows Belvedere Road running between Westminster and Waterloo Bridges, with Howley Place shown at Howley Terrace, Tension Street and Sutton Walk with the same names as previous maps, but further along, where College Street and Vine Street were shown in the 1895 Ordnance Surcey map, the street is now called Jenkins Street. This map is the only place I have seen this name for the street, so it was either an error, or there was a name change between 1895 and 1940.

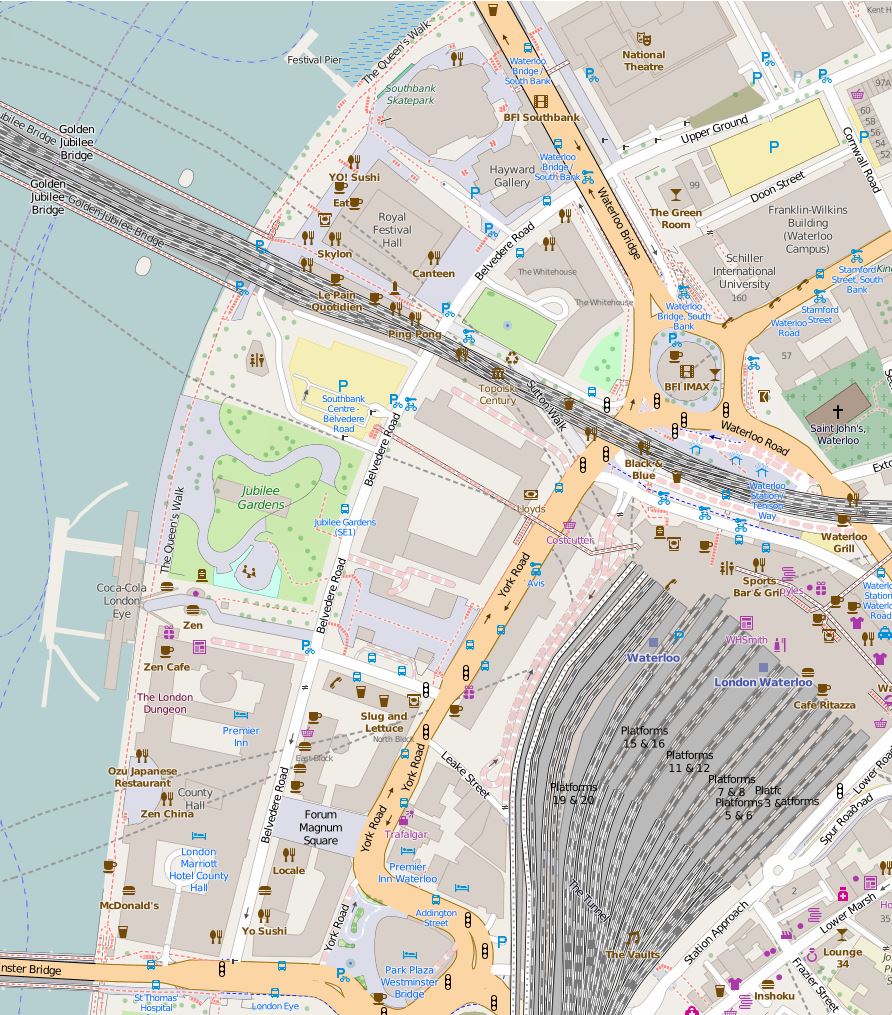

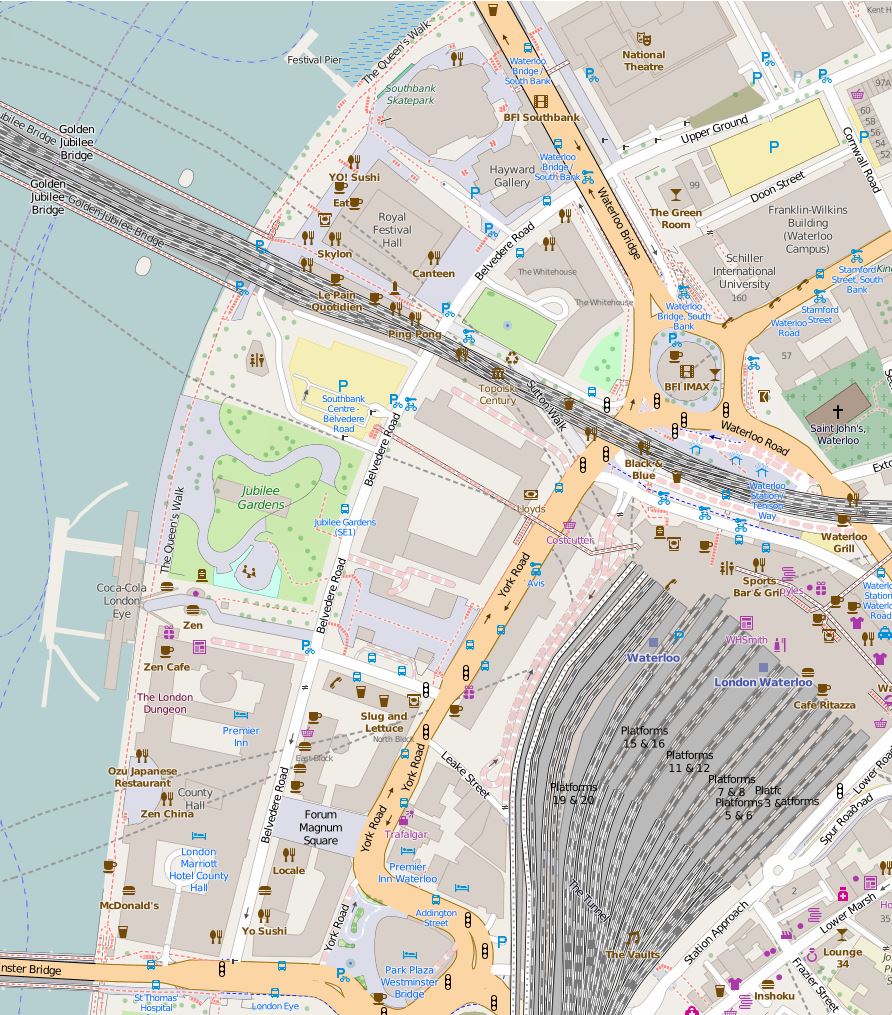

And finally we come to today and the following map shows the layout of the area as it is now – although this will also change soon as the buildings surrounding the Shell Centre tower have been demolished to make way for a new development of multiple apartment towers.

The map shows roughly the same area, between Waterloo Bridge at the top of the map and Westminster Bridge at the bottom.

The only streets that remain from previous years are Belvedere Road and Chicheley Street. Belvedere Road has been widened and straightened over the years, but follows roughly the same route as the Narrow Wall and the original earthern embankment.

There is more land between Belvedere Road and the river as during the construction of County Hall and the Festival of Britain, the embankment was pushed further into the river.

The approach road to Waterloo Bridge now covers the area occupied by Cuper’s Gardens. The Royal Festival Hall occupies the site of Timber Yards and then the Lion Brewery.

The Coade Stone Factory was on the site now occupied by the car park above the Jubilee Gardens.

The rows of terrace houses between Belevedere Road and York Road have gone with the space being occupied by the Shell Centre Upsteam and Downstream buildings – off which all but the tower building have either been converted into apartments or have been demolished to make way for more apartment blocks.

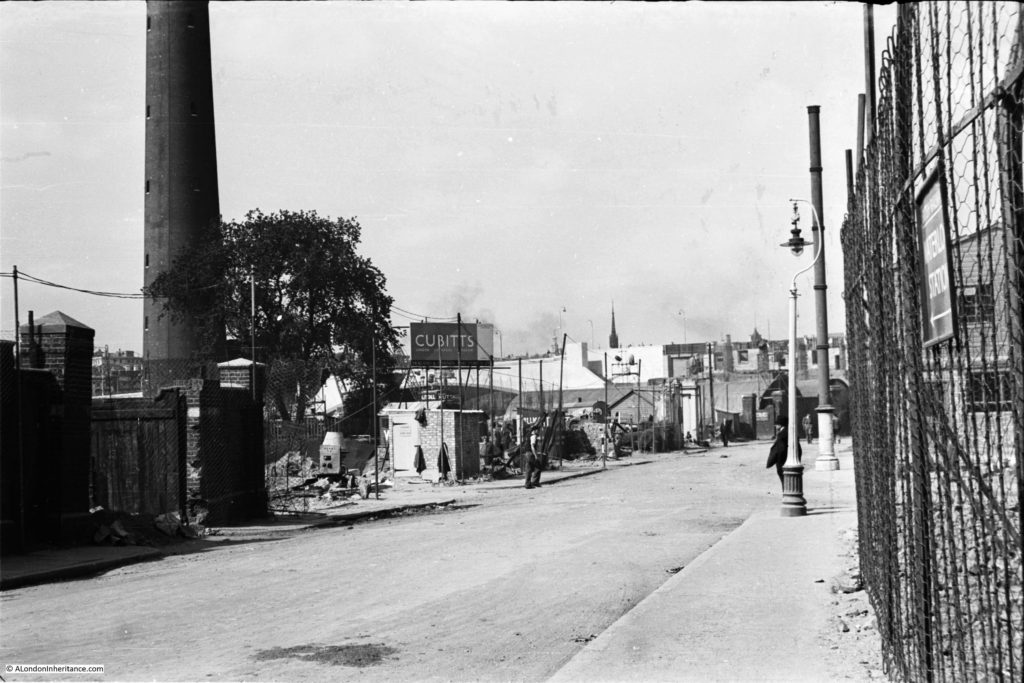

In my next post we will have a walk along Belvedere Road looking at the buildings and views from between 1947 and 1950 as the site is prepared for the Festival of Britain and comparing with the same scenes today.

All the prints in the above post are ©Trustees of the British Museum

The extracts from the 1895 Ordnance Survey Map are reproduced by permission of the National Library of Scotland.

alondoninheritance.com