Before taking a look at the long history of the London Stone, a quick advert as I have arranged some dates for my very last tours of the year, and the last ones until probably May of next year. I have included all my different tours, and it would be great to show you many of the stories and photos from the blog over the last nine years, at the actual sites.

Dates and links for booking as follows:

Thursday 28th Sept 2023 – Limehouse – A Sink of Iniquity and Degradation(Sold Out)Saturday 30th September 2023 – Wapping – A Seething Mass of Misery(Sold Out)Saturday 7th October 2023 – The Lost Streets of the Barbican(Sold Out)- Sunday 15th October 2023 – Limehouse – A Sink of Iniquity and Degradation (1 ticket available)

Sunday 22nd October 2023 – Wapping – A Seething Mass of Misery(Sold Out)Saturday 4th November 2023 – The South Bank – Marsh, Industry, Culture and the Festival of Britain(Sold Out)Sunday 5th November 2023 – Bankside to Pickle Herring Street – History between the Bridges(Sold Out)- Sunday 12th November 2023 – Limehouse – A Sink of Iniquity and Degradation (1 ticket available)

It would be wonderful to see you on a walk – now to the London Stone.

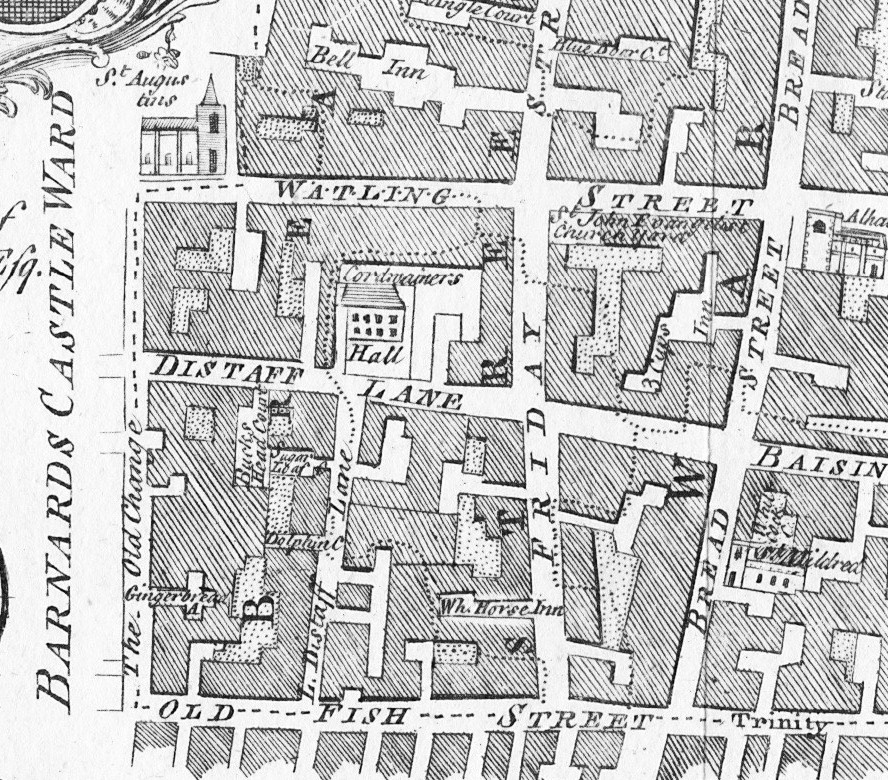

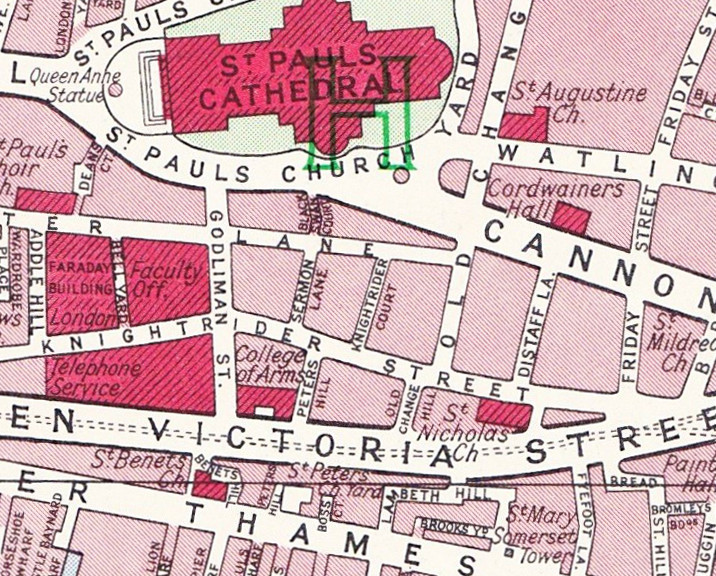

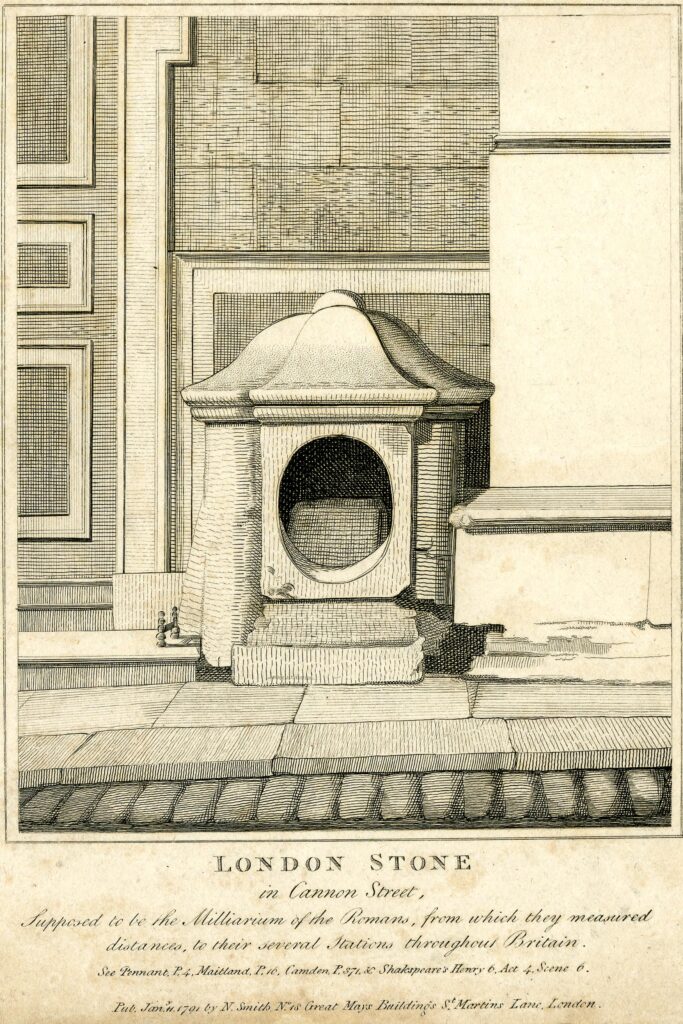

In its ability to attract myths and legends, the London Stone is far more powerful than its physical size suggests. A long time resident of the area around what is now Cannon Street Station, but with the distance of time, it is impossible to know the truth about the block of stone, which can now be found in a new housing with a glass front:

The new housing for the London Stone was completed in 2018, along with the building of which the stone is part of the ground floor frontage onto Cannon Street:

The plaque to the left records some of the key stories about the London Stone:

- It may be Roman and related to Roman buildings to the south

- It was already known as the London Stone by the 12th century

- Jack Cade, the leader of a rebellion against the government of Henry VI in 1450 struck the stone with his sword and claimed to be Lord of London

The plaque on the right tells the story in braille which is rather good.

The previous building on the site was an early 1960s office building, which was demolished 2016, when the London Stone was moved to the Museum of London where is was put on temporary display, before being moved to its new home.

A view of the London Stone through the window at the front of the housing:

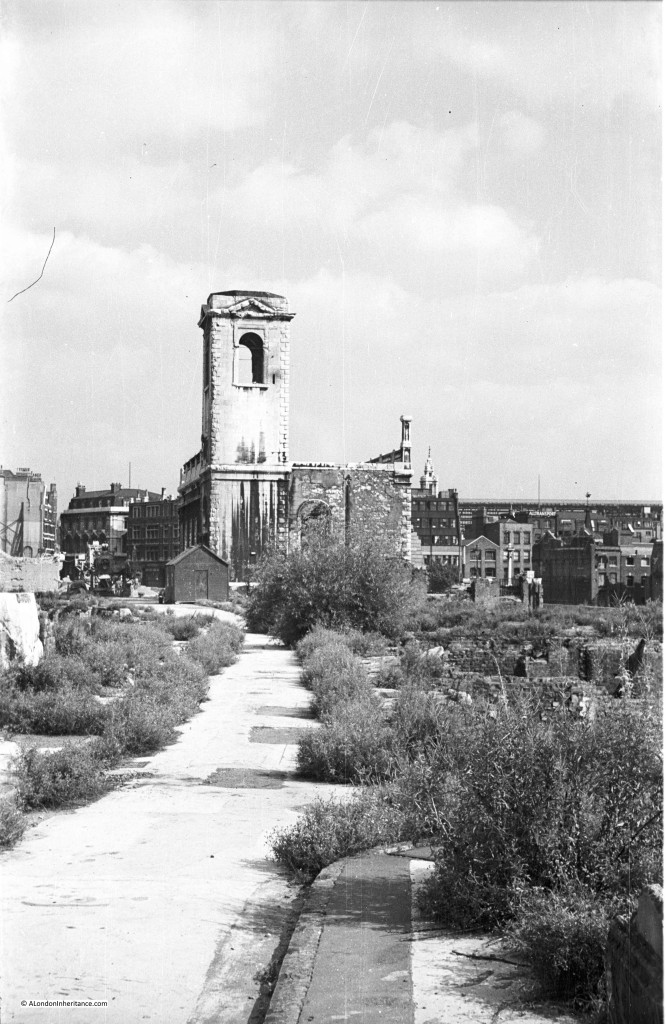

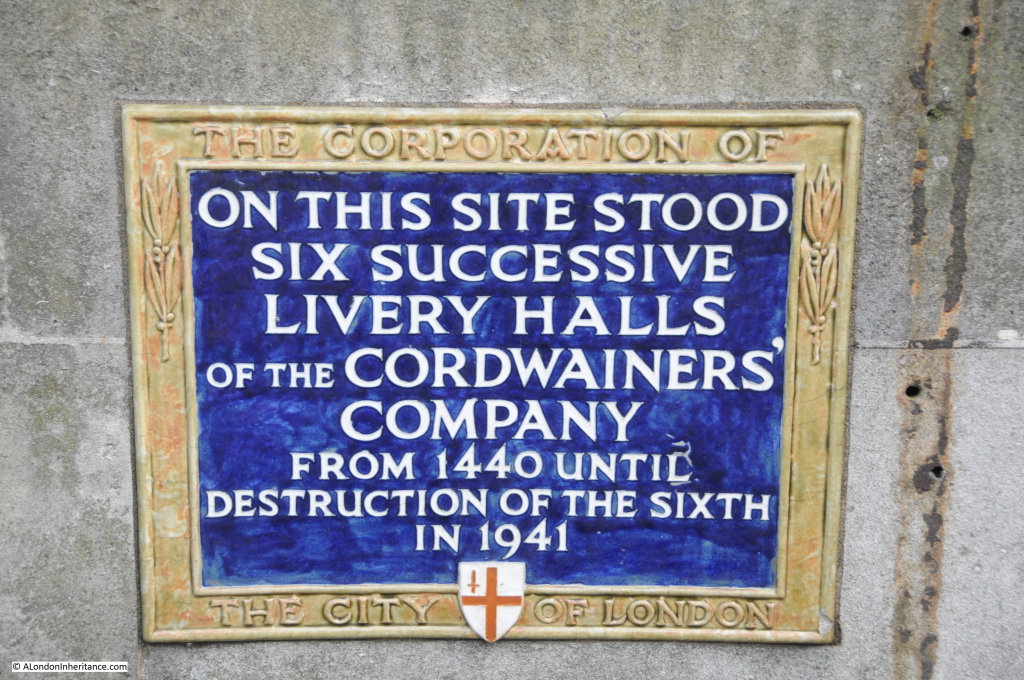

The site was originally occupied by St. Swithin’s Church, however the church was destroyed by bombing in 1940. The stone walls of the church, with the London Stone, survived, and continued to stand on the site until being demolished for the 1960s office building.

Wonderful London has a photo of the London Stone in its housing on the front of St. Swithin’s Church, I doubt that the stone usually had a police guard:

The Wonderful London description below the above photo reads: “Set in a stone casing in the wall of St. Swithin’s, Cannon Street, is this block of oolite, guarded by a grille. It was placed there in 1798, having been transferred from the other side of the road. Camden, the historian, 1551 – 1623, held that it was the milliarium, or milestone, from which distances were calculated on the main roads in days when London was Londinium Augusta. There was a similar stone in the Forum at Rome. If Camden is right, Roman lictors may have stood, like this policeman, in front of the stone 1,600 years ago”.

The text mentions that the stone is a block of oolite, which is a form of limestone, and was used in Roman London for building and sculpture, but may also have arrived in the City in the Saxon and early medieval period.

There was a large Roman building where Cannon Street Station now stands, so it may have formed some part of this building, or some of the decorative sculpture or statues that would have been part of the building.

There is no way to be sure.

The Roman milliarium or milestone story is repeated in multiple accounts of the stone. Sir Walter Besant in his 1910 book on the City of London includes the milestone story, but goes further by saying that some have supposed the stone to be the remains of a British druidical circle or religious monument. He quotes Strype as saying that Owen of Shrewsbury gave rise to the assertion that “the Druids had pillars of stone in veneration, which custom they borrowed from the Greeks”.

Besant also records that “Sir Christopher Wren was of opinion that ‘by reason of its large foundation, it was rather some more considerable monument in the Forum; for, in the adjoining ground to the south, upon digging for cellars after the Great Fire, were discovered some tessellated pavements, and other extensive, and other remains of Roman workmanship and buildings.”

The problem with all these stories about the original Roman use of the London Stone is that there is no firm evidence that it was a milliarium or milestone, when it arrived in the City, whether it was Roman, or the original use of the stone.

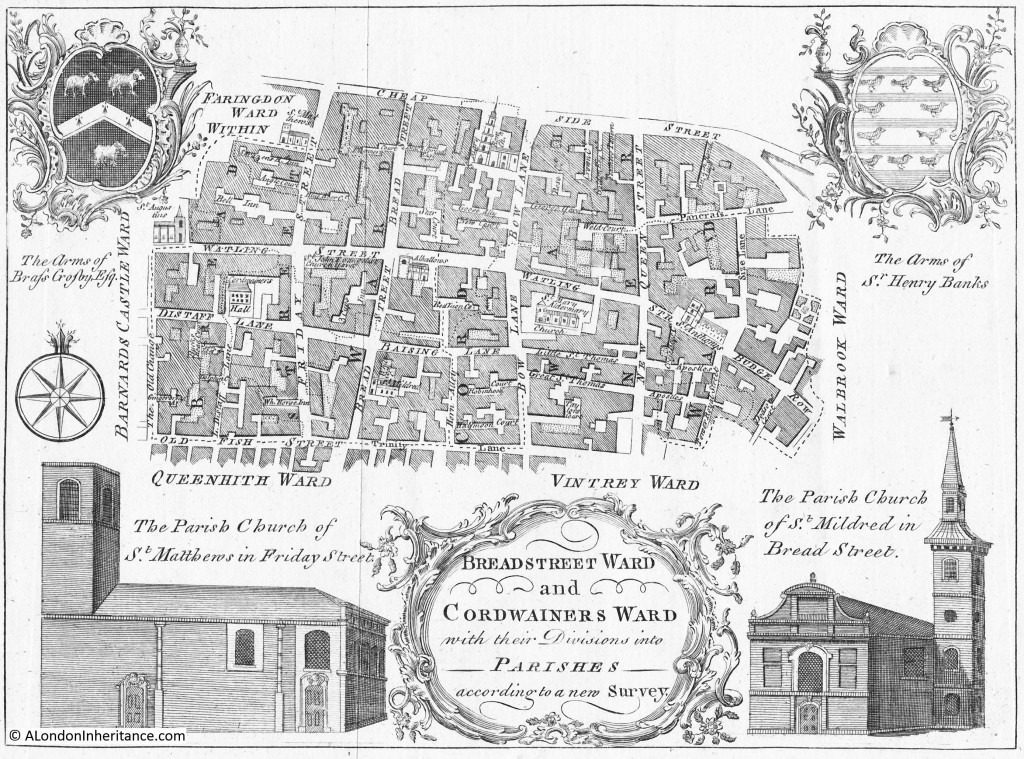

What seems to be certain is that the stone has long been in this part of Cannon Street. It was originally on the south side of the street and was also in the street, where it was an obstruction to the traffic flowing along the street.

The Wonderful London quote references that the stone was moved to St. Swithin’s Church, and guarded by a grill in 1798. This was urgently needed to protect the stone, as it appears to have been frequently under attack by those who used the street, as this report from several papers on the 2nd of July 1741 records:

“Thursday a Carman and a Drayman contending for the Way in Cannon-street, made a shift between them to throw down the little Building that covers London Stone (as ’tis call’d) and then pull the said Stone out of the Earth. this being presently known, great Numbers of People flocked to see it, and many curious Observations, Conjectures, and Prognosticks were believed by the Wiseacres present, on so extraordinary an Accident.”

The 16th century historian John Snow, who first published his Survey of London in 1598 included the following reference to the London Stone which explains how it was fixed in position, and why it was a significant obstruction for those who used Cannon Street:

“On the south side of this high street, near unto the channel is pitched upright a great stone called London stone, fixed in the ground very deep, fastened with bars of iron, and otherwise so strongly set, that if Carts do run against it through negligence, the wheels be broken, and the stone it self unshaken.”

The London Stone seems to have been a well known feature of Cannon Street, as it was often used as part of an address, such as in the following from an advert in the Kentish Gazette on Friday, November the 6th, 1795, where a contact was given as “Mr. Sergeant, Number 86, London Stone, Cannon Street”.

And on the 26th of February 1788 there was an announcement in the Kentish Gazette of the marriage at “St. Swithin’s, London Stone, of W.T. Reynolds’s Esq. of Great St. Helen’s to Miss Sands of St. Dunstan’s Hill”

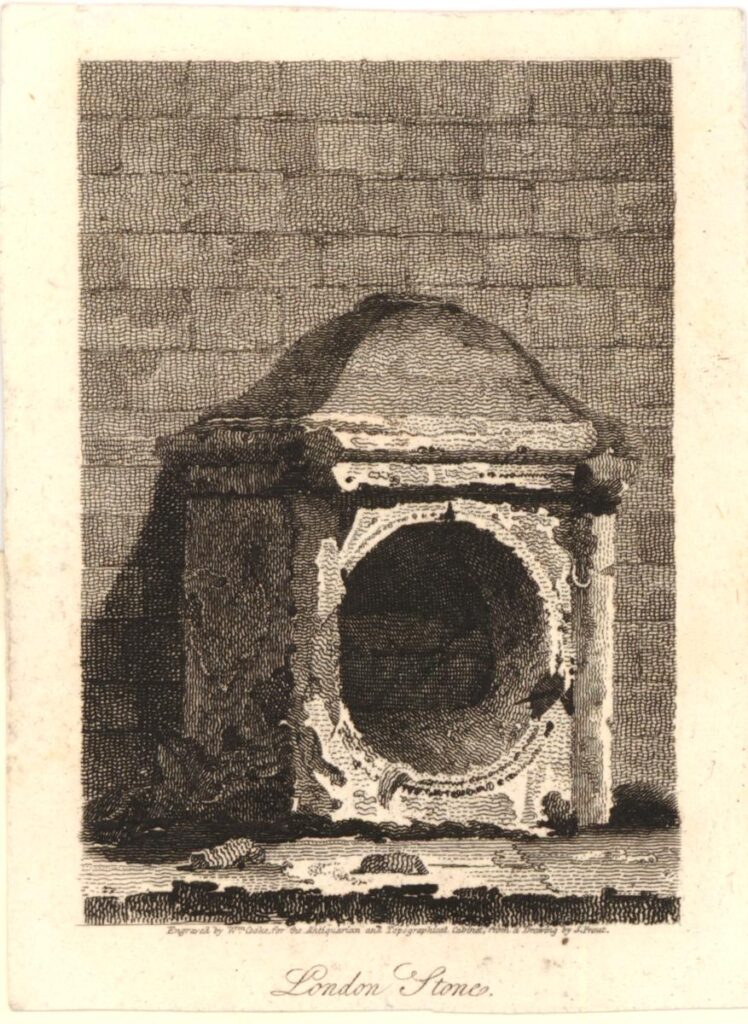

The following print from 1791 shows the London Stone in a casing up against St. Swithin’s church, as although Wonderful London mentioned 1798 for the positioning of the stone against the church, it had been moved to this safe location some years earlier, and in 1798 the church went through a major set of repairs, which included proposals for the stone to be removed as a nuisance, however there were many objections and the stone was kept up against the front of the church ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

The above print repeats the milliarium story and provides sources from a number of historians, who, to an extent are repeating the same story, but not providing any firm evidence.

The print also includes a reference to Shakespeare’s Henry Vi, Act 4, Scene 6, and it is from this scene that Shakespeare amplified the story of Jack Cade’s association with the London Stone.

Jack Cade led a rebellion in 1450, from the south east of the country against the corruption, poor administration and the abuse of power by the King’s local representatives.

He led a large group of men from the south-east who headed into London in an attempt to raise their grievances, remove from power those they held responsible for corruption and abuse of power, and to reform governance.

Once within the City, the rebellion turned into looting, and the residents of the City turned on the rebels

The rebels were offered a pardon to return home peaceably. Cade as the leader was captured in a fight and died of his injuries as he was being returned to London for trial.

The connection between Jack Cade and the London Stone comes from the rebellion’s entry into the City of London. Cade pretended to use the name of Mortimer, (the family name of ancestors of one of Henry VI’s main rivals), and on reaching the London Stone, he struck his sword on the stone and according to Holinshed (a 16th century English chronicler), he exclaimed “Now is Mortimer Lord of this City”.

Describing the London Stone in Old and New London, Walter Thornbury embellished the story of Jack Cade by adding that “Jack Cade struck with his bloody sword when he had stormed London Bridge”.

This drawing from the late 18th century shows Cade in the act of striking the stone ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

There is no reason why Cade would have used the London Stone in such a way. It was not a tradition for Kings or Lord Mayors of the City to strike the stone for any form of recognition.

Accounts imply that Cade did do this, but it was Shakespeare who really amplified and spread the story, including Cade using the stone as a sort of throne from where he issued proclamations and judgments. All part of the myths surrounding the London Stone.

The above print of Cade does show the stone in the street, not against the church, which appears to have been its location until the 18th century.

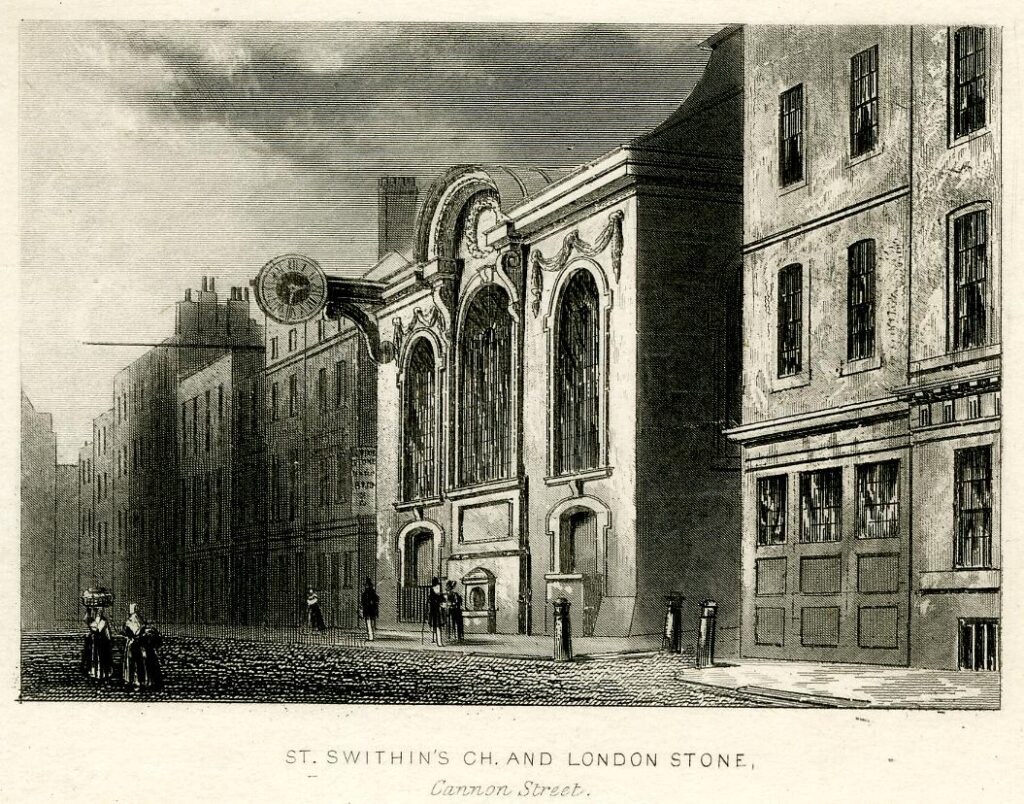

The following early 19th century print shows St. Swithin’s Church with the London Stone in the centre of the church, at ground level, facing onto Cannon Street ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

Another view from the early 19th century which appears to show the housing of the London Stone in a rather poor state ( © The Trustees of the British Museum):

The Illustrated London News on the 13th of March 1937, reported that the London Stone was to be moved to a worthier setting, that it would be moved into an arched recess higher up the church, and flood lit at night.

Unfortunently, these plans were not carried out due to the start of war in 1939.

The Illustrated London News did repeat one of the apparent myths concerning the London Stone, that it “is believed to have originally been a tall prehistoric menhir, and later a Roman milliarium or milestone”, so not just tracing the stone back to Roman origins, but attributing a very much earlier origin as a prehistoric standing stone.

As well as prehistoric origins of the London Stone, there are also a number of myths about spiritual associations with the stone, the position of the stone at a centre of the City, and that if anything ever happens to the London Stone, the City will fall.

The following saying which is alleged to date from the medieval period has been repeated in a number of books about London:

So long as the Stone of Brutus is safe

So long will London flourish

John Clark in Folklore, Vol. 121, No. 1 found that this saying only existed from 1862.

A Brutus Stone seems to have been found in a number of places, for example in the Dartmouth and South Hams Chronicle on the 4th of March 1898: “Mr. Page rather made fun of the Brutus Stone set in the pavement of the High-street in Totnes, and of the claim that it was the stone on which Brutus of Troy landed when he came to Britain.”

Kipling used the name London Stone for a poem published in the Times on the 10th of November 1923. The poem was an elegy on grieving for the dead, however the poem referred to the Cenotaph, rather than the stone in Cannon Street (although the name of the poem was changed in different publications, as explored by the Kipling Society).

Many of the stories associated with the stone are just that, myths and stories, and there is very little to confirm the history of the stone prior to the medieval period.

Wherever stones are found, from the complexity of Stonehenge to a single prehistoric standing stone in a field, they always attract myths and legends.

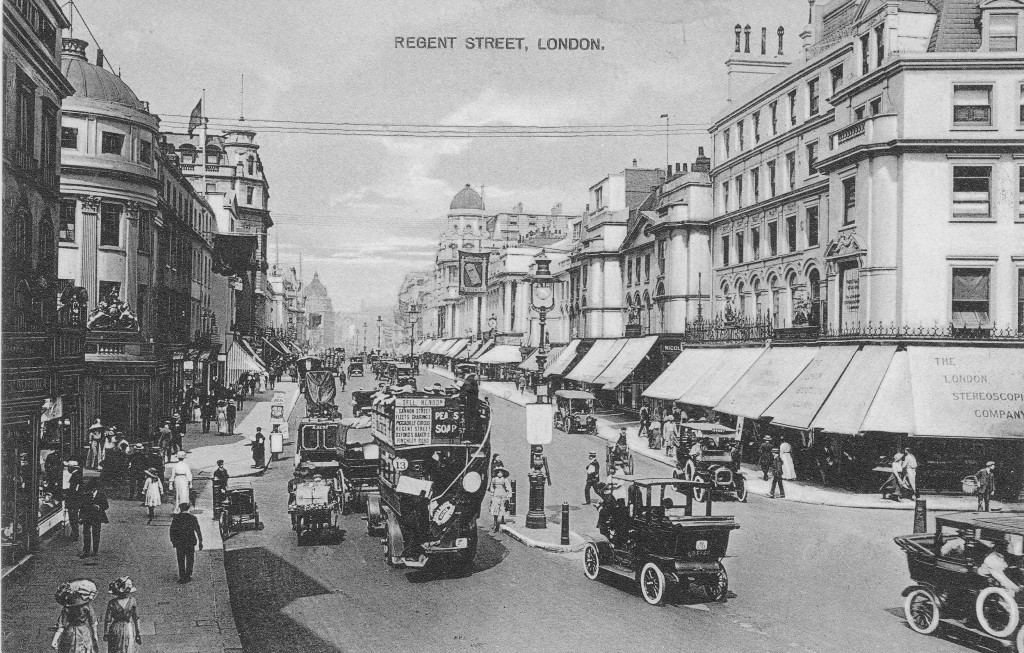

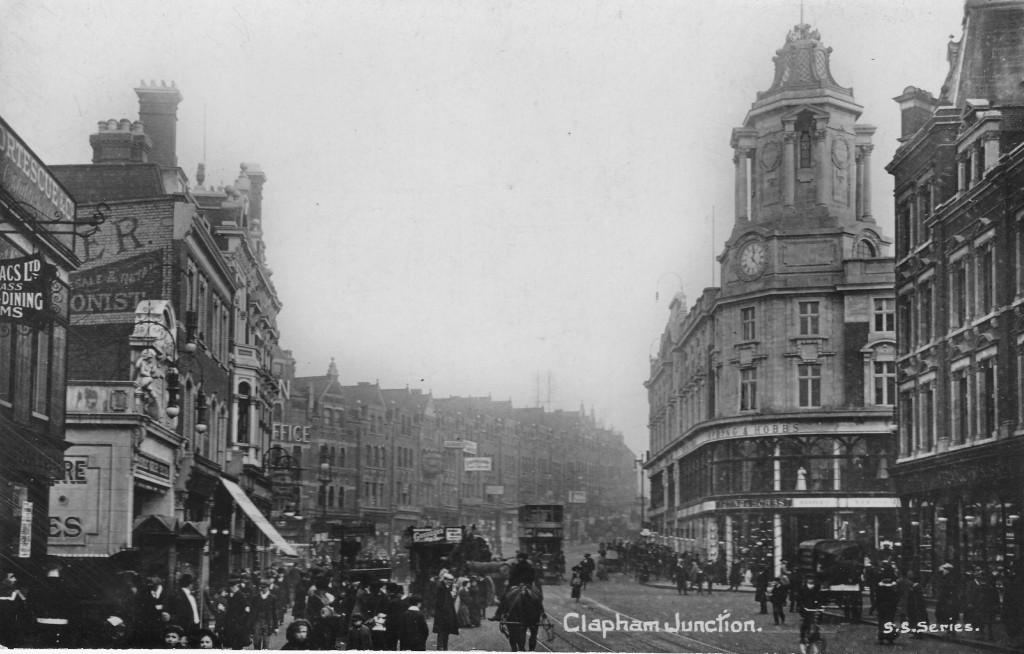

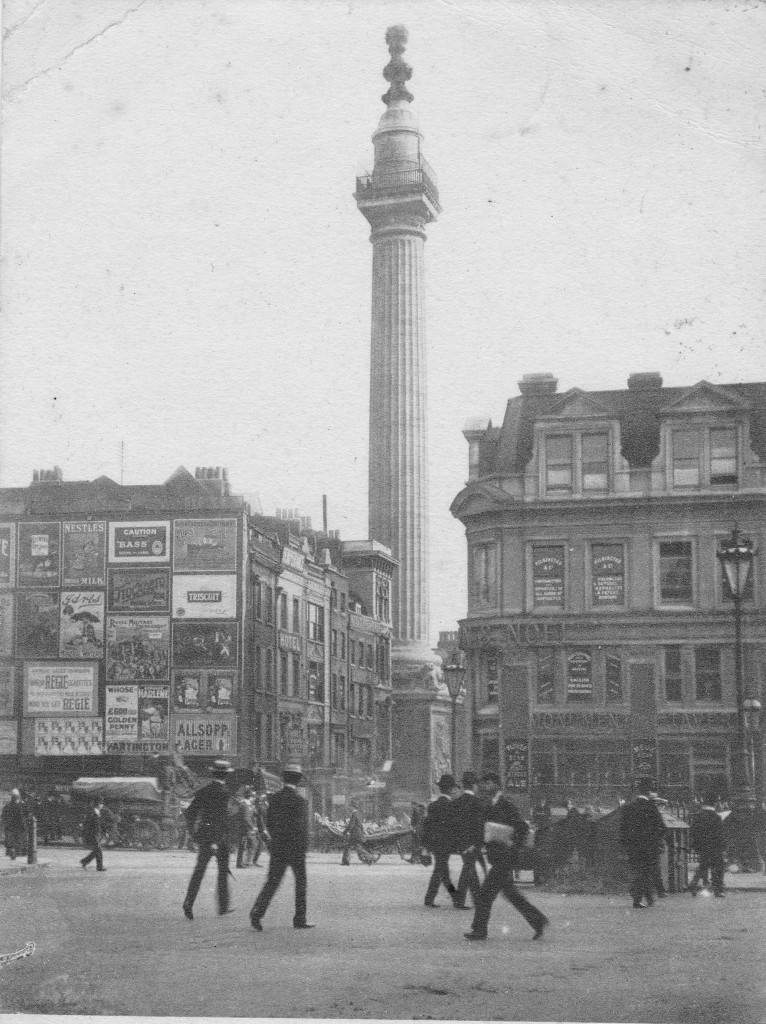

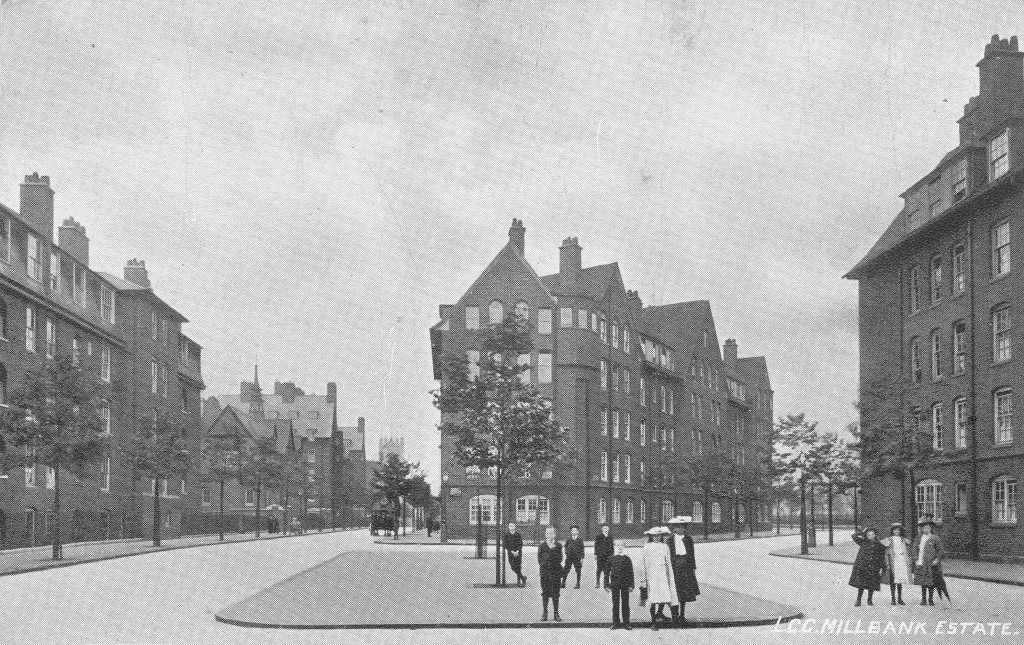

I used a reference from Sir Walter Besant’s 1910 book on the City of London earlier in the post, and opposite the page on the London Stone was this view looking west along Cannon Street towards St. Paul’s. Part of St. Swithin’s church is on the right, with the London Stone just out of shot:

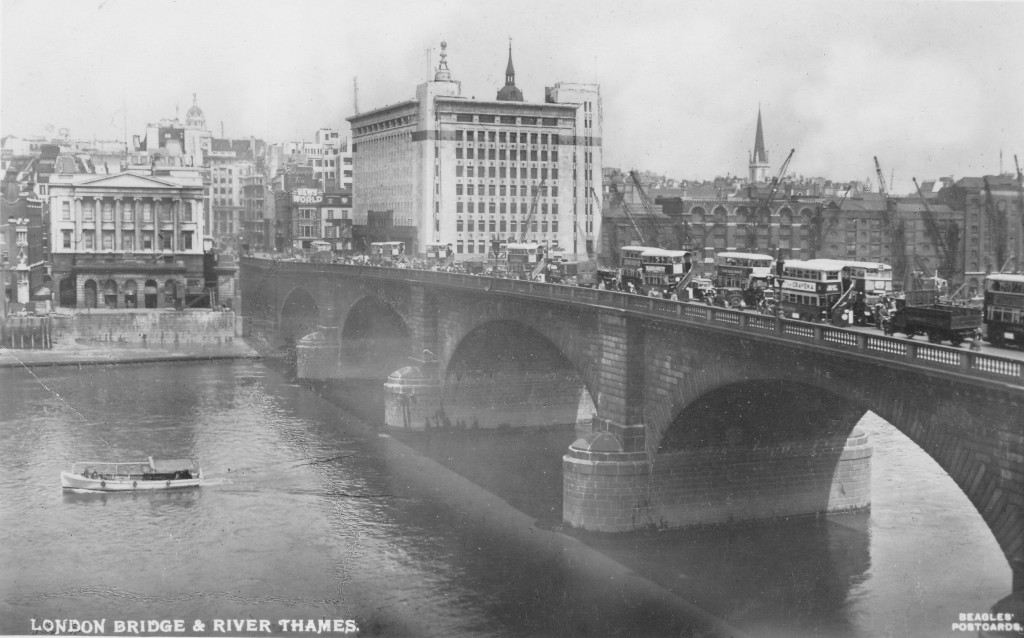

One hundred and thirteen years later the street is just as busy. Apart from St. Paul’s there is only one building that is in both views. In the photo below, on the immediate right is a building with distinctive arches over the windows. In the above photo, you can see the same building on the right, a little further down the street.

The first written reference to the London Stone appears to be from the late 11th century, so the stone is old, but as to its origins and purpose, we can only make educated guesses, and whilst it has moved slightly around its current location in Cannon Street over the centuries, it has looked out on an ever changing street scene.