The City of London has always regarded the boundaries of the City as important in defining where the jurisdiction of the City extended. This included having very visible symbols of where you were crossing from the wider city into the City of London. One such symbol was Temple Bar in the Strand:

The above photo dates from 1878, and comes from the book Wonderful London, which describes the scene as “Scaffolding and buildings show signs of the housebreaker on the left, where the Law Courts are in the process of erection. Their site alone cost £1,450,000, and in the years that have gone since the camera made this precious record, most of the scene has changed out of all recognition. Four buildings remain, St. Dunstan’s Church, the top of whose spire can just be seen, the façade of the entrance to the Middle Temple beyond the southern footway of Temple Bar and the two white houses on the right where the ladders are leaning.”

Not long after the above photo, Temple Bar was demolished, the Law Courts were completed, and a new monument was built on the site of Temple Bar, and Wonderful London recorded the changed street scene:

There was a forty year gap between the above two photos, and the caption in Wonderful London to the above photo reads “On the right the white building of No. 229 still stands, but it is its neighbour that is under repair this time. These two houses are said to have escaped the Great Fire, which destroyed much of the street. St. Dunstan’s is just visible above the winged griffin that ramps on the monument marking the site of the old Temple Bar. The width of the street is almost double what it was, and it would obviously be impossible to get the modern column of traffic through the old narrow arch. The pediment over the gateway of Middle Temple Lane can be seen on the right.”

Although Temple Bar had disappeared from the Strand, the City of London saved the stones that made up the structure. Numbering each individual stone and keeping a plan of their location, the stones of Temple Bar were stored in a yard in Farringdon Road.

The stones of the old gate were purchased by Lady Meux, wife of Sir Henry Bruce Meux (of the Meux’s Brewery Company), who owned a house in Theobalds Park, near Cheshunt, and Temple Bar was rebuilt there in 1888.

The London Evening Standard reported on the laying of the foundation stone at Temple Bar’s new location on the 9th of January 1888: “The foundation stone of Temple Bar was laid on Saturday afternoon by Lady Meux at the entrance to Theobald’s Park, Cheshunt. Her Ladyship was accompanied by Sir Morell Mackenzie and several other ladies and gentlemen. There was a large gathering. At the platform which was erected, her ladyship was received by Mr. Elliot of Newbury, the contractor for the re-erection of the bar, and Mr. Poulting, the architect. Before the ceremony of laying the foundation stone commenced Mr. Elliot presented Lady Meux with a model of Temple Bar worked in oak, a silver trowel, and a mahogany mallet. After depositing a bottle, some of the current coins, several newspapers, and other articles, the stone was lowered, and was declared well and truly laid. About 400 tons of the stones have already been carted to Cheshunt at a cost of £200.”

The book “The Queen’s London” published in 1896 included a photo of Temple Bar in its new location at Theobald’s Park:

Apparently Lady Meux used the room over the central arch for entertaining. The gate frequently appeared in sporting newspapers which included photos of the local fox hunt and hounds meeting in front of the gate.

By the 1920s, Wonderful London’s photo of the gate showed the accumulated dirt of the years since it was rebuilt in 1888. Note the smoke rising from the chimney of the gatehouse to the left.

Almost as soon as Temple Bar had been demolished, and rebuilt in Cheshunt, there were murmurings that it had not been the best decision by the Corporation of London, and that a location for the historic structure should have been found in London. For example, on the 8th of October, 1906, a Mr. H. Oscar Mark wrote to the Westminster Gazette lamenting the removal of the old Temple Bar to Theobald’s Park:

“Surely a site could have been and could now be found in the widened Strand, or in Aldwych, or, if necessary, in the open space west of the Law Courts buildings where old Temple Bar could be seen and admired, as everyone with any sense for the antique or artistic could not help doing. I would suggest that strenuous efforts should be made by Londoners who love their London and its old landmarks – of which we have too few left – to reacquire this fine old relic, and to re-erect it on one of the sites named or in the heart of London.

We can ill afford to lose ancient monuments, the more so when they are of so highly interesting a character as this one must be to thousands of London’s inhabitants.”

Despite languishing in Theobald’s Park, Temple Bar refused to be forgotten in the minds of Londoners. In 1921, the Illustrated London News published a photo of Temple Bar at Theobald’s Park with the caption “To be restored to London?”.

In November 1945, a syndicated newspaper column stated that “I see that the suggestion of bringing Temple Bar back from Theobald’s Park to the City of London has once more been made, this time as part of the scheme for rebuilding the destroyed portions of the Inner and Middle Temples. The suggestion may stand a better chance of being carried out now; but whenever it was made in the lifetime of Admiral Sir Hedworth Meux, owner of Theobald’s Park, he greeted it with caustic comments on the vandalism of Londoners and their unworthiness to possess so fine a piece of architecture as Temple Bar.

Nor were these strictures unjustified. When Temple Bar was pulled down from its old position across Fleet Street at the City boundary, Londoners openly rejoiced at this removal of a traffic obstruction that had long been a nuisance; and the numbered stones lay about in unsightly heaps, derided by all, until they were sold.”

Post war rebuilding would perhaps have been the ideal time to restore Temple Bar to London, however money for such a project was short, and the approach to rebuilding tended to take two divergent views, either to restore to what had been, or to build buildings that fitted the view of a more modern City.

Meanwhile Temple Bar continued to slowly deteriorate in Theobald’s Park:

(Image credit: Temple Bar, Theobalds Park cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Christine Matthews – geograph.org.uk/p/185643)

Plans to return Temple Bar to London began to take on a more positive aspect in 1976 when the Temple Bar Trust was formed, specifically with the aim of returning the structure to the City.

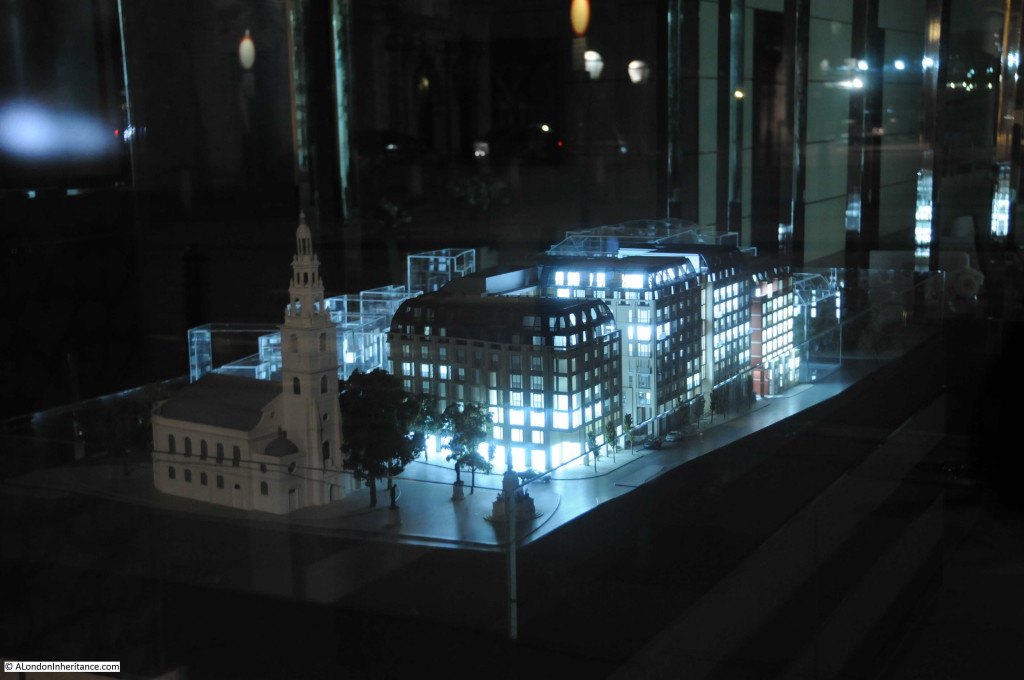

Rebuilding of the area to the north of St. Paul’s Cathedral offered an opportunity for Temple Bar, where it could form part of the Paternoster Square development. A landmark location, where there were no concerns about traffic restrictions that such as structure would impose.

Temple Bar was again dismantled, transported back to London and rebuilt over one of the entrances to Paternoster Square. Temple Bar was officially reopened at its new, third, location on the 10th of November 2004 by the Lord Mayor of London:

But the version of Temple Bar we see at the entrance to Paternoster Square was only the last of a series of barriers across Fleet Street / the Strand, to mark the boundary of the City of London.

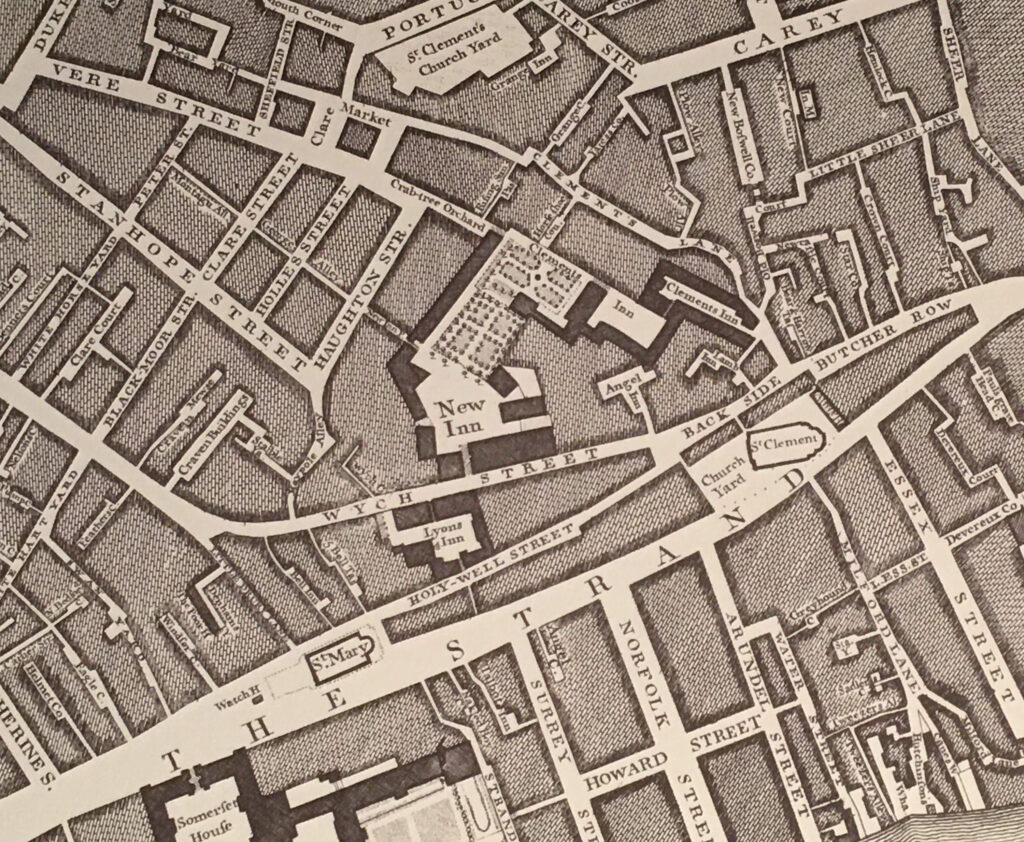

The first references to a barrier across the street date back to the 13th century when a bar was recorded as being across the street. This was not a stone structure, and would probably have been some form of wooden or chain barrier that could be moved across the street. The bar, and location close to the Temple appears to have been the source of the name Temple Bar.

The historian John Strype, writing in the early 18th century stated that at Temple Bar “there were only posts, rails, and a chain, such as are now in Holborn, Smithfield, and Whitechapel bars. Afterwards there was a house of timber erected across the street, with a narrow gateway and an entry on the south side of it under the house.“

It is difficult to be sure of the appearance of earlier versions of Temple Bar. One print dating from 1853 which claimed to be copied from an old drawing of 1620 shows what Temple Bar may have looked like in the 17th century (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Temple Bar was rebuilt between 1670 and 1672 by Sir Christopher Wren, and it is Wren’s version that we can see in Paternoster Square today. Built of Portland Stone, the structure continued to provide an impressive gateway to the City of London.

The location of Temple Bar is perhaps further west of what could be considered the traditional boundaries of the City, the original City Wall and the Fleet River.

Temple Bar is where the Freedom of the City of London met the Liberty of the City of Westminster, and originally whilst not part of the original City of London, it is where the freedoms granted to and by the City of London extended beyond the original City walls, up to the point where Westminster took over jurisdiction.

The location is also where Fleet Street and the Strand met. We can still see this today if you stand by the monument on the site of the gate and look across to the Law Courts where there is a street sign for the Strand, and opposite on the old building of the Child & Co. bank is the sign for Fleet Street.

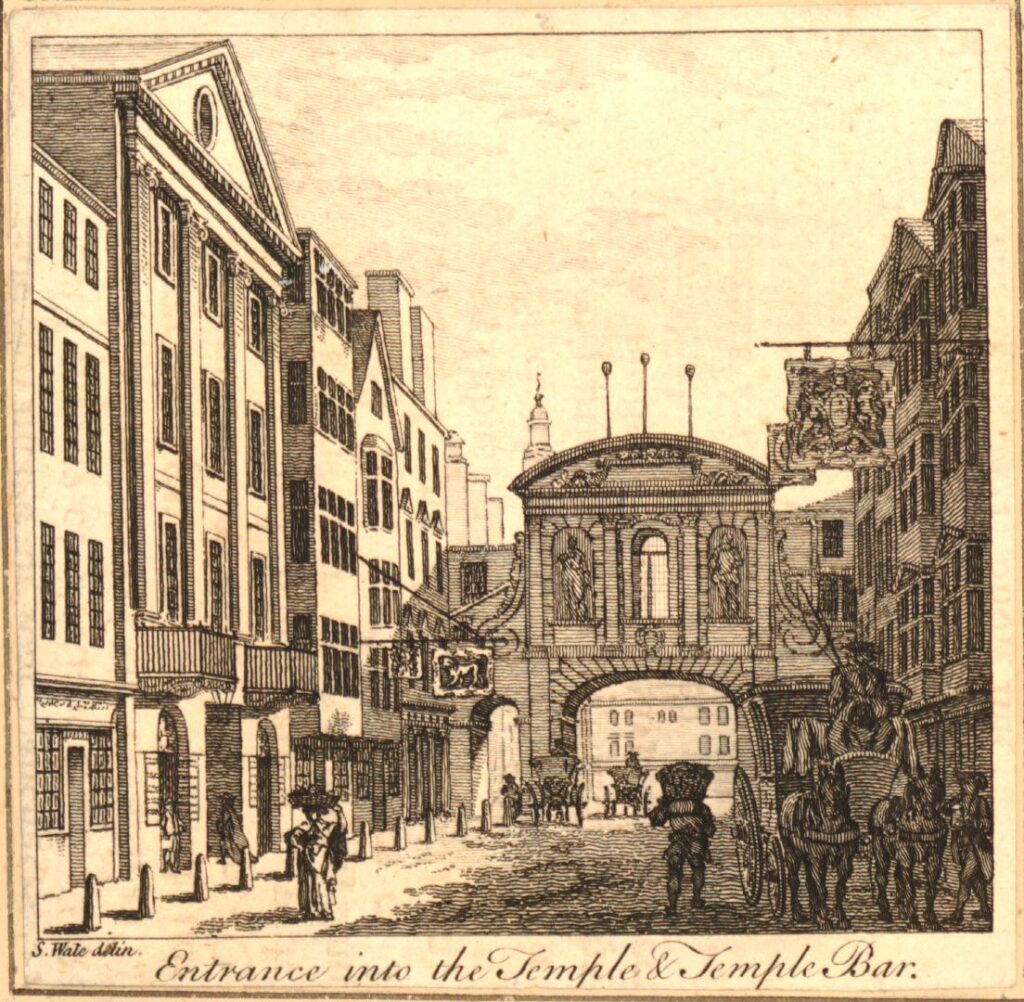

The following print shows Temple Bar in 1761 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Perhaps the most disturbing part of the above print is that even at this point in the 18th century, heads of the executed where still being displayed on poles high above the gate.

The display of heads seems to have been just part of everyday life for 18th century Londoners. Newspaper reports on the 7th of February 1732 simply reported that: “On Sunday the Head of Colonel Oxburgh, who was executed for being in the Preston Rebellion, and had his Head stuck on a Pole, fell off from the Top of Temple Bar.”

The last heads to be displayed above Temple Bar were those executed following the 1745 Jacobite rebellion, including Colonel Francis Townley and George Fletcher.

They were hung on Kennington Common, cut down, then disemboweled, beheaded, and quartered, after which their hearts were thrown into a fire, and at the end of August 1746, newspapers report that “On Saturday last the Heads of Townley and Fletcher were brought from the New Goal, and fixed on two Poles on Temple Bar. The Heads of Chadwick, Barwick, Deacon and Syddall, are preserved in Spirits, and are to be carried down to Manchester and Carlisle, to be affixed on Places most proper for that Purpose.”

A few days later, on the 13th of August, 1746, the Kentish Weekly Post carried a report that showed how feelings were still running high after the 1745 rebellion: “On Friday a Highlander, as he was passing by Temple Bar, and observing the Heads there, uttered several treasonable expressions, upon which he was severely handled by the Populace.”

The heads stayed on their poles for a considerable number of years, until March 1773, when a strong March wind brought down one head, with the second following soon after.

Temple Bar was also the scene of less grisly punishments, with a pillory being set up at the gate. In 1729 it was reported that a Mr. William Hales “Received sentence to pay a Fine of ten Marks upon each Indictment, to stand in the Pillory twice, viz. once at the Royal Exchange, and once at Temple Bar, to suffer five years imprisonment, and to give Security for his good Behaviour for seven years.”

Temple Bar was though the scene of far more enjoyable activities with numerous processions passing through the gate and ceremonies being held at the gate. When the Monarch entered the City, they would be greeted by City dignitaries at the gate.

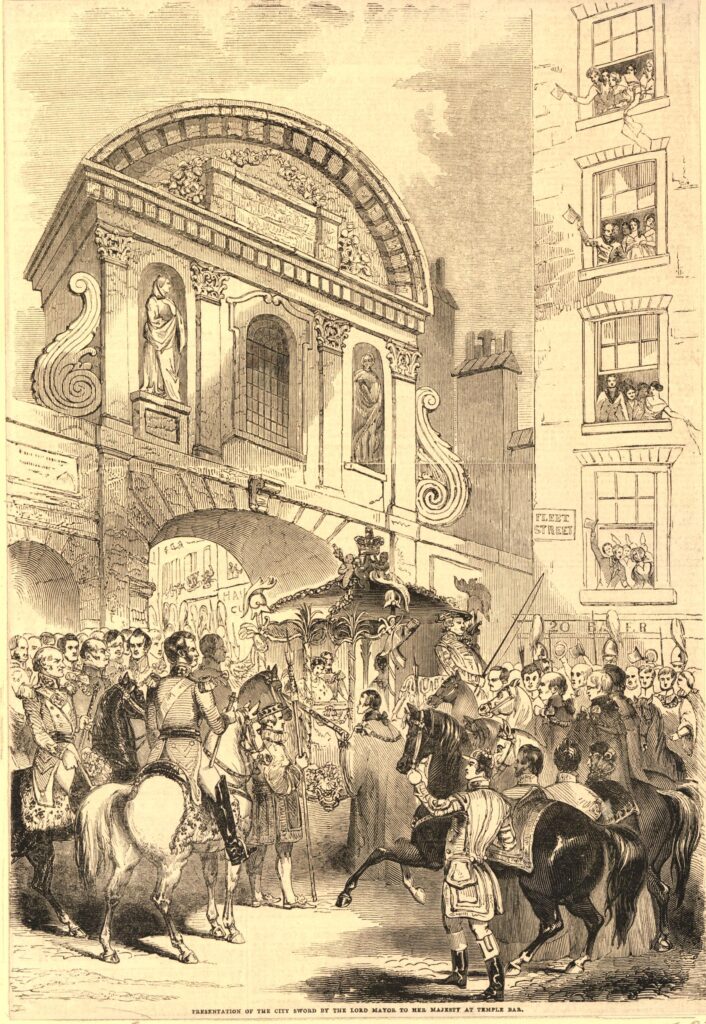

On the 9th of November 1837, Queen Victoria was greeted at Temple Bar where she was presented with the ceremonial sword of the City of London.

During the funeral of Lord Nelson, his funeral procession was met at Temple Bar by the Lord Mayor and representatives of the Corporation of London.

The following print shows another of Queen Victoria’s visits to the City where the Queen and Prince Albert in the royal carriage, are being presented again with the ceremonial sword of the City of London as they arrive at Temple Bar(© The Trustees of the British Museum):

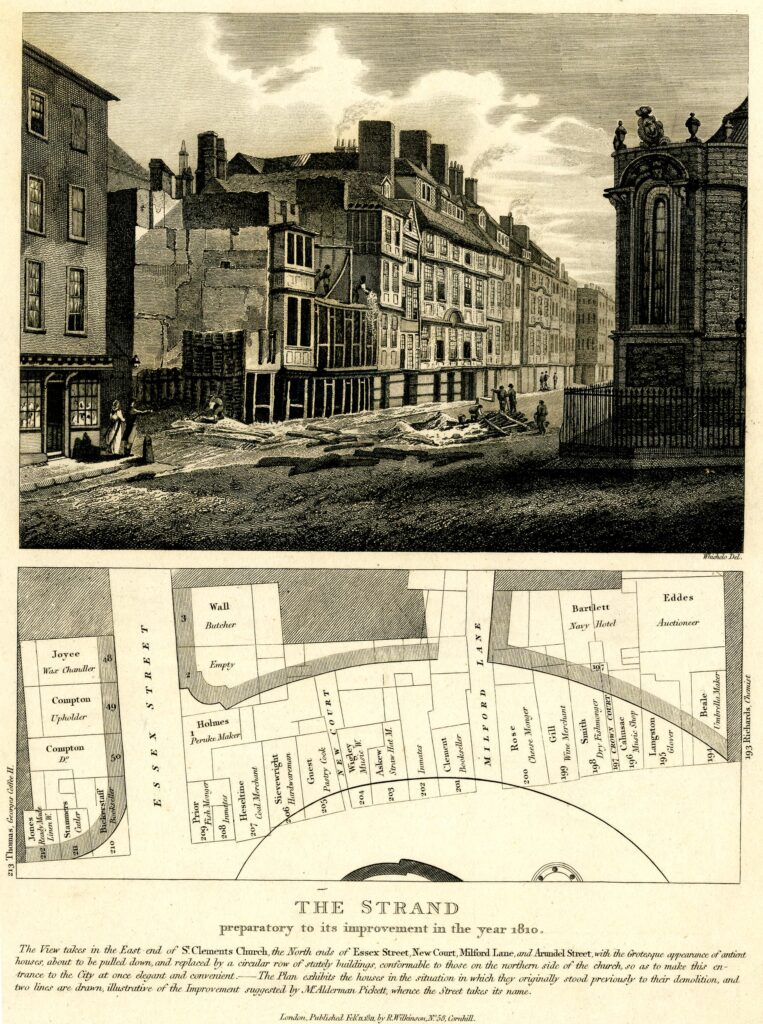

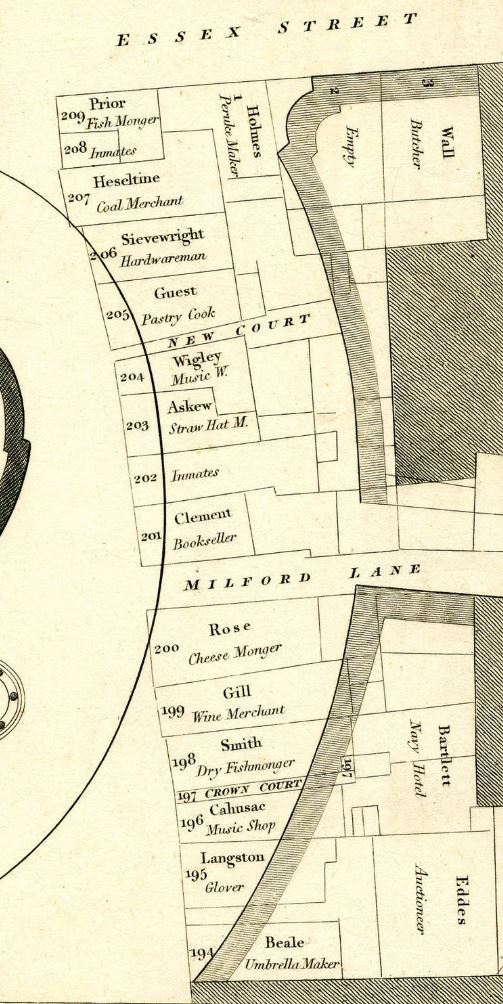

In the second half of the 19th century, much of the area around Temple Bar was being redeveloped, with the Law Courts being the major development to the north of the gate. The following print, dated 1868, shows buildings being demolished ready for construction of the Law Courts and is titled, and shows the “Forlorn Condition of Temple Bar” (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

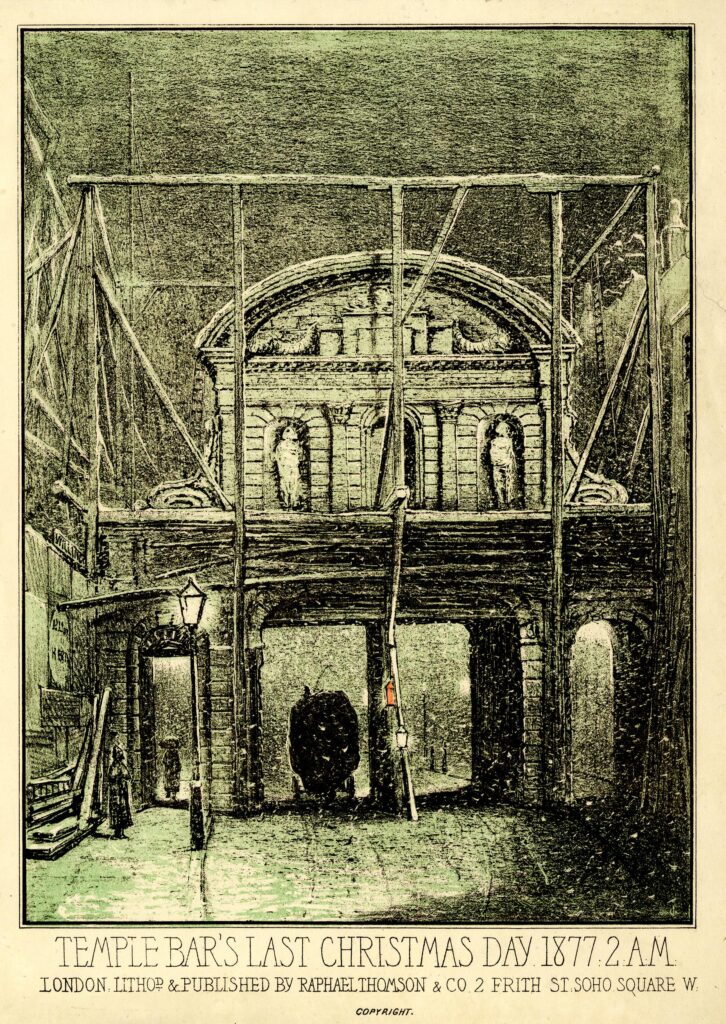

And almost ten years later, a print showed the structure ready for demolition, with the title of “Temple Bar’s Last Christmas Day” (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

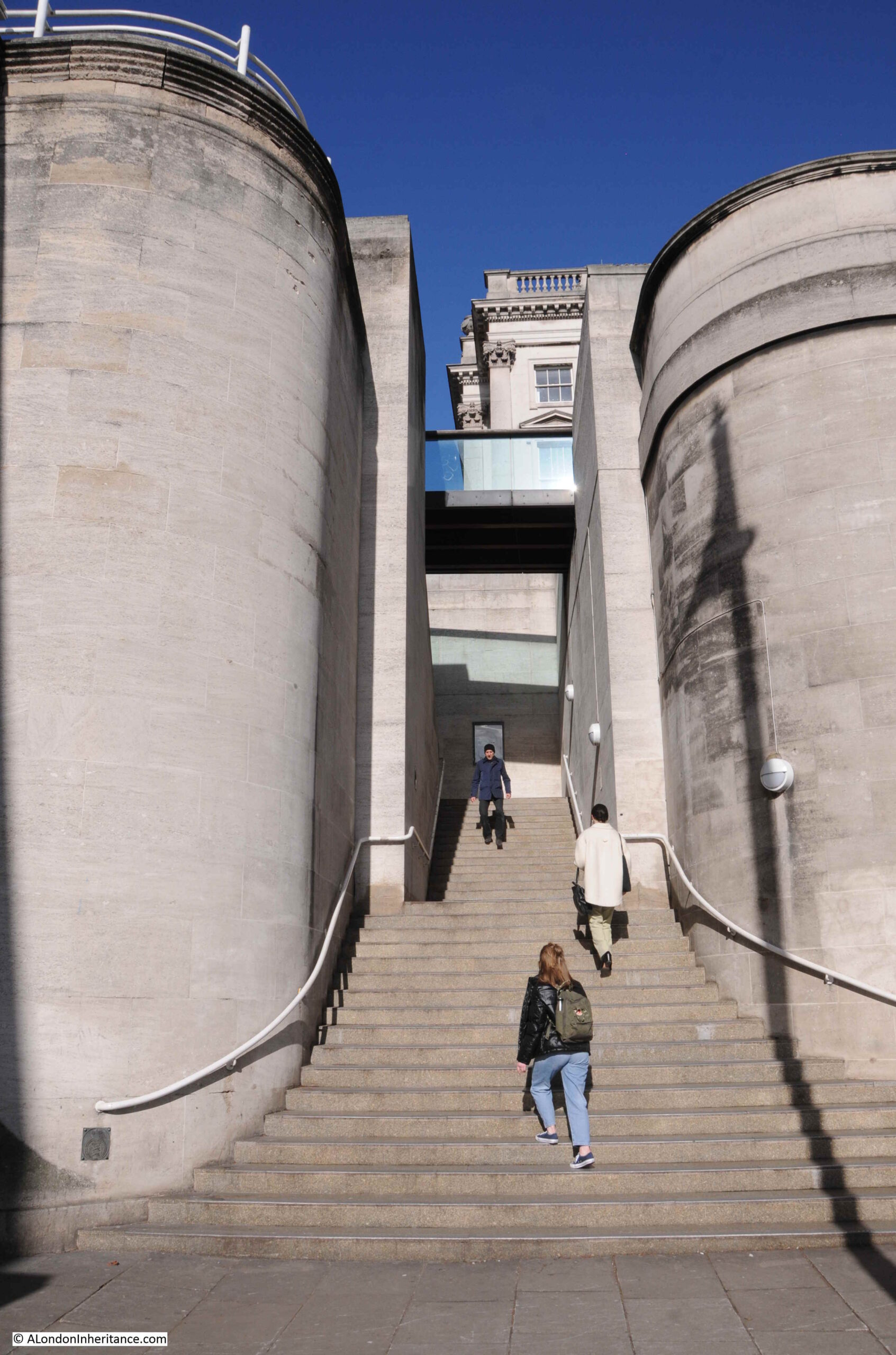

And today we see the gate between Paternoster Square and St. Paul’s Cathedral:

There are a number of statues on the gate. The following photo shows the statues that originally faced to the east and Fleet Street. On the right is James I. The figure on the left is often referred to as Anne of Denmark, the wife of James I, although there are other references, including in Old and New London by Walter Thornbury who claims the statue is of Queen Elizabeth. Anne of Denmark seems to be the most probable.

On the old western, Strand side of the gate are statues of Charles I and Charles II:

A plaque in the ground by the gate records the names of Edward and Joshua Marshall, Master Stone Masons, Temple Bar, 1673.

Edward was the father and Joshua the son.

They were stones masons who worked on a considerable number of 17th century buildings and monuments in the city. It is believed that the majority of the work on Temple Bar was completed by Joshua, as his father was in his sixties by the time of the gate’s construction.

So what of the monument that can be seen today at the old location of Temple Bar?

It was still important to mark the boundary to the City of London, and soon after Temple Bar was demolished, a new monument was built in the centre of the widened street:

In 1880, the Illustrated London News described the new monument: “The new structure will be of an elaborate and handsome character, from designs by Mr. Horace Jones, the City Architect. It will be 37ft high, 5ft wide and 8ft long. The base will be of polished Guernsey granite, the next tier of Balmoral granite, and above that will be red granite from the same quarry as that used in the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park.

In niches in the north and south sides will be life size figures in marble of the Queen and the Prince of Wales, by Mr. Boehm, and in panels in the sides will be reliefs in bronze by Mr. Mabey and Mr. Kelsey, of the Queen’s first entrance into the City through Temple Bar in 1837, and of the procession to St. Paul’s on the day of the thanksgiving for the Prince of Wale’s recovery. The superstructure will be of hard white stone, and will be surmounted by a griffin, the heraldic emblem of the City, which is being executed by Mr. Birch.”

As well as marking the location of Temple Bar, the monument was claimed to offer a refuge for those crossing the street, however the Illustrated London News did not understand this justification, or the need for marking the boundary: “We know of no sufficient reason for marking this particular boundary. Other similar landmarks – such as Ludgate, Aldgate, Cripplegate, and Bishopsgate – have been removed without loss of municipal prestige, rights, or privileges worth preserving. The need of a refuge is much more obvious where the thoroughfare is wide, like Regent Street, or still more where roads intersect.”

Victoria’s son, Prince Edward, Prince of Wales on the side of the monument facing the Law Courts:

On either side of the statues there are columns of carvings, with the left column representing Science and the Arts on the right column. On the narrow ends of the monument there are columns of carvings representing War and Peace.

The new monument was far from universally popular and there was much criticism about the design and location.

in 1881, the Corporation of London had appointed a committee to look at the memorial and decide whether it should be removed and placed in some more convenient spot.

The Times included an article which referred to the monument that the “erection is an eyesore in point of taste, a mischievous obstruction instead of a public convenience and reckless expenditure. As to its future, the best that we could hear would be that it was likely to disappear and be no more seen. The 10,000 guineas or more that it cost would be wasted, no doubt, but they could not be more thrown away than they are at present on a monument which no one likes, and everyone laughs at.”

The monument was even vandelised, despite being guarded. The Weekly Dispatch reported on the 7th of August 1881 that “Notwithstanding the vigilance of the City and Metropolitan Police who are appointed to guard the memorial, it was on Friday morning discovered that there had been further mutilation of the bas-relief representing various events in civic history.”

And on the 29th of August 1881 “On Saturday evening a young man who was lodged in the Bridewell police station on a charge of wilfully damaging the Temple Bar Memorial. A gentleman who was passing by saw the prisoner deliberately disfiguring the heads and legs of the figures with his fists. The attention of a police-constable was called to the matter, and he immediately took the offender into custody. When asked by the Inspector why he had done it, the prisoner replied, ‘I did it for fun. It is only an obstruction, and I didn’t see why I should not have a go at it as well as other people.”

The monument seems to have gradually been accepted, receiving less attention as time went by, although being in the middle of the busy Fleet Street / Strand, with growing levels of traffic in the 20th century, the monument was occasionally still referred to as an obstruction.

Below the statues, there are four reliefs on the four sides of the pedestal.

The first is a rather accurate reminder of the location of Temple Bar:

The text reads: “Under the direction of the committee for letting the City lands of the Corporation of London. John Thomas Bedford Esq. Chairman. The west side of the plinth is coincident with the west side of Temple Bar and the centre line from west to east through the gateway thereof was 3 feet 10 inches southward of the broad arrow here marked.”

On the end of the monument facing Fleet Street is a relief of Temple Bar:

On the side is a relief titled “Her most gracious Majesty Queen Victoria and his Royal Highness Prince Albert Edward Prince of Wales going to St. Paul’s February 27 1872”:

And on the other side of the plinth is a relief titled “Queen Victoria’s progress to the Guildhall, London Nov. 9th 1837.“

The importance of this location as a boundary, not just as the boundary to the City of London, can be seen by a boundary marker set in the pavement on the south side of the street, directly opposite the monument:

This is a boundary marker of the parish of St. Clement Danes. The relevance of the anchor is that it became the symbol of St. Clement as he was apparently tied to an anchor, then thrown into the sea to drown.

I assume that the parish of St. Clement Danes would have ended at the boundary with the City.

What is fascinating about the story of Temple Bar is the recurring theme of how buildings and architecture are treated in London. For example, from Mr. H. Oscar Mark’s letter earlier in the post where he suggested that “strenuous efforts should be made by Londoners who love their London and its old landmarks – of which we have too few left – to reacquire this fine old relic, and to re-erect it on one of the sites named or in the heart of London“.

This was followed by a chorus of criticism about the new monument that replaced Temple Bar at the meeting of Fleet Street and the Strand.

However I suspect there would be concern and criticism if there were proposals today to remove the monument. How we view buildings and architecture in general is very much related to time and their age.