If you have been on my Puddle Dock walk, you will recognise this location, the old Mermaid Theatre alongside Puddle Dock.

Although I have written about Puddle Dock before (there is a link at the end of the post), I have not covered the Mermaid Theatre, so time to remedy that omission in today’s post.

The Mermaid Theatre is the brick building in the centre of the following photo:

Upper Thames Street is the road in the foreground. This was constructed on land reclaimed from the Thames foreshore as part of the late 1970s / early 1980s redevelopment of the whole area in the photo.

The street Puddle Dock, which occupies the site of the original Puddle Dock is the street to the left of the photo.

Another view of the Mermaid Theatre. This is not the original theatre, it was part of the redevelopment of the area when the surrounding office blocks were built, along with Upper Thames Street:

The following photo shows the original Mermaid Theatre building, the smaller building in the centre of the photo, alongside the edge of the Thames:

In the above photo, all the land in front of the theatre would be reclaimed to allow the move of Upper Thames Street to a new dual carriageway. New office blocks were built around the theatre and Puddle Dock, which can be seen to the left of the theatre, was filled in and the street with the same name constructed.

The story of the theatre, how it came to occupy this bomb damaged site, and its transformation to the place we see today, is the subject of today’s post.

The Mermaid Theatre was the dream of Bernard Miles and his wife, Josephine Wilson.

Bernard Miles was born in Uxbridge to a father who was a market gardener and mother who was a cook.

He went to school in Uxbridge and then Pembroke College, Oxford, and after university he took a job as a teacher, but he would not stay for long in this profession.

His first acting role was as the second messenger in a revival of Richard III, after which he joined a number of repertory companies taking on roles from a carpenter to an actor. He had London stage roles in the late 1930s and early 1940s, including touring with the Old Vic.

He also had a number of film roles starting with the 1932 film, Channel Crossing, and the films that followed included In Which We Serve (1942) and Great Expectations (1946), and he continued to have film roles through to his final film in 1988, The Lady and the Highwayman.

He also appeared on TV, with one of his best known roles as Long John Silver in a TV series and later TV film of Treasure Island. He would also play the role of Long John Silver when Treasure Island was put on at the Mermaid Theatre.

He perhaps overplayed the role of a pirate when he “kidnapped” the Governor of the Bank of England on a short river journey on the Thames, when he “relived” the Governor of a cheque for £25 in support of the Mermaid, and then used the event to claim that the Mermaid Theatre was supported by the Bank of England.

It was down to Bernard Miles enthusiasm for the Mermaid Theatre, his ability to fund raise, and his sheer hard work throughout the whole process, that took the Mermaid Theatre from idea through to a working theatre, opening in 1959.

To explore the story of the Mermaid Theatre, I will use the Press Information document issued for the official opening of the theatre at 6p.m. on Thursday the 28th of May, 1959:

The press pack starts with the background to the Mermaid:

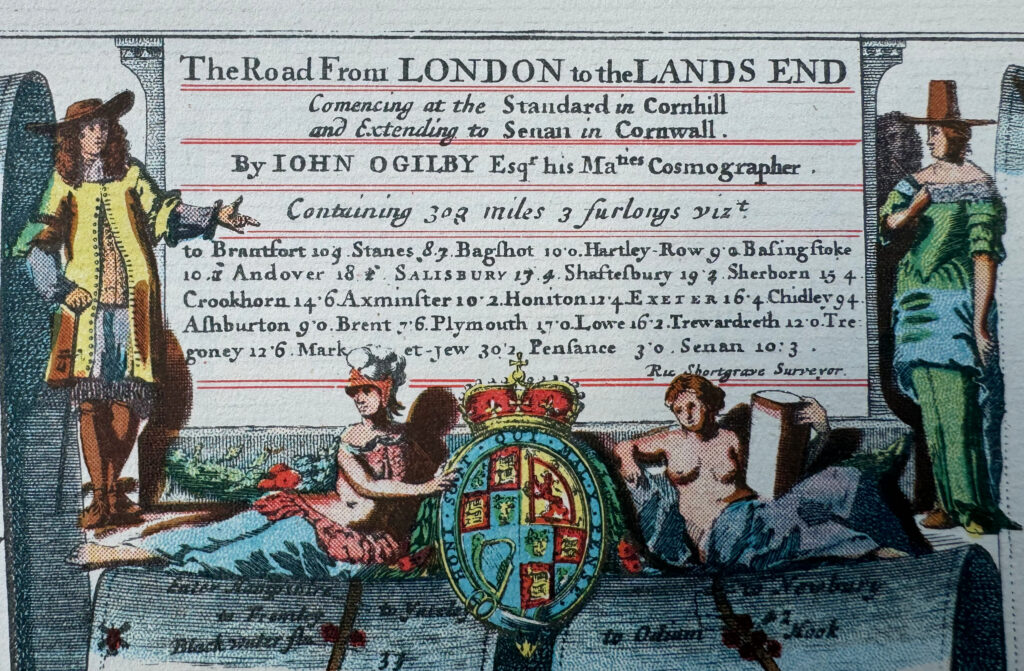

“‘See the players well bestowed’, says Hamlet, and the City has obeyed his solemn injunction by helping to bring to fruition a dream born on Acacia Road, St. john’s Wood, nine years ago.

In the dream Bernard Miles and his wife, Josephine Wilson saw one of the most exciting small theatres in Europe rising against the blitzed warehouses of the City’s riverside. They saw a new and vital centre of entertainment thriving in the great business hub of the Commonwealth.

In that summer of 1951, they had built a small theatre in their back garden. Its stage and fittings had been planned by two brilliant young designers, Michael Stringer and Walter Hodges, and early in September the Mermaid Theatre opened with Kirsten Flagsted singing twenty-six performances of Purcell’s ‘Dido and Aeneas’. Her salary for the season was a bottle of stout a day.

This first season was such a success that it was decided to have another one the following year. This time Bernard and Josephine Miles had no idea that before long they would be building a real bricks and mortar theatre in E.C.4. But during the second Mermaid season, a good friend of the Miles’ brought the Lord Mayor, Sir Leslie Boyce, to see the production of Macbeth. It was the Lord Mayor who suggested that the Mermaid be brought to the City for Coronation Year.

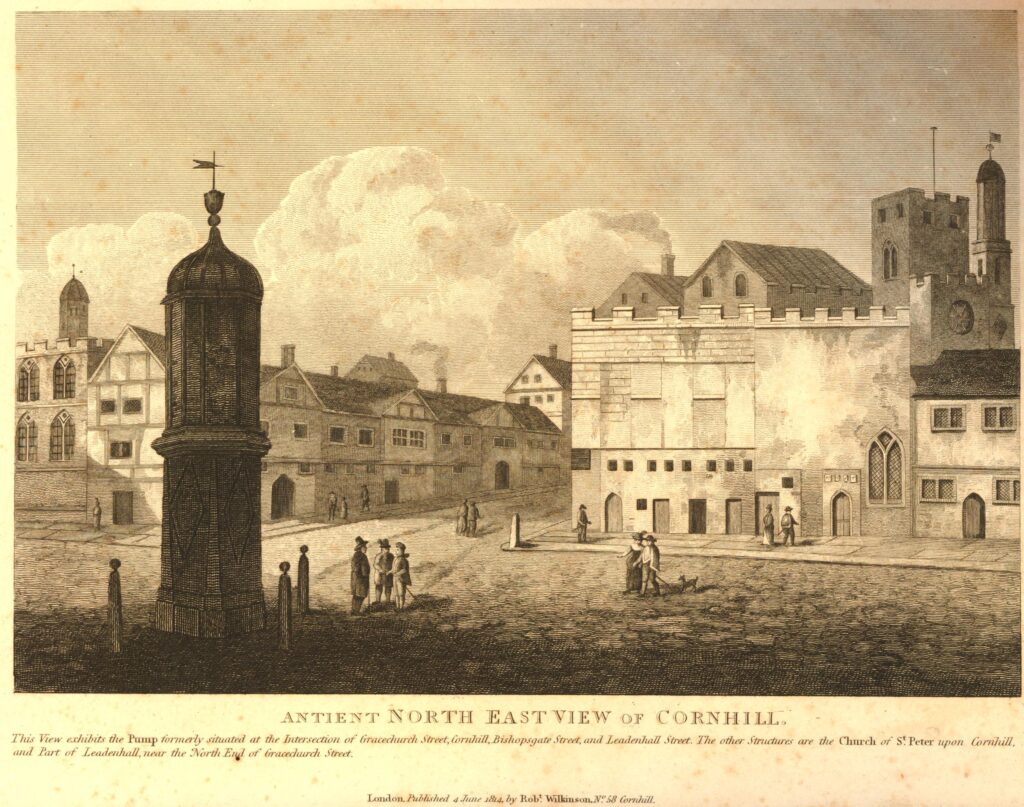

So it came about that between May and August 1953, the Mermaid Company played 13 weeks on the Piazza of the historic Royal Exchange in the very heart of a City, theatre less for nearly 300 years. And 70,000 people paid to see the four productions. This solid support led the Miles’s to believe that there was a very real demand for drama in the City.

From this point the ball began to roll towards Puddle Dock. It was argued that if they could persuade the City Corporation to lease them a bombed site for a token rent and then build the theatre by public subscription, they could set it fee from rent and so bring the price down to a real pubic service and habit forming level.

And since the entire Box Office takings could then be spent on the productions, this freedom from rent would also act as a negative subsidy, giving vital artistic elbow room.

In 1956, the Corporation generously granted a lease of the Puddle Dock site, so rich in theatrical associations. Then began the task of raising the £62,000 required to build and equip the theatre.”

The Puddle Dock site provided by the City Corporation really was a bombed warehouse, as can be seen in the following photo with the warehouse that would become the Mermaid Theatre on the left, with Puddle Dock, with a moored barge, to the right of the warehouse:

Looking up what was Puddle Dock today, with the old Mermaid Theatre buildings on the right:

Following the provision of the warehouse site, the next step was to try and raise the money needed to build and equip the theatre. The press pack continues:

“COLLECTING THE MONEY: The Mermaid has been financed entirely by public subscription. By donations from banks, shipping companies, insurance companies, stockbrokers, the City livery companies, ordinary men and women all over the United Kingdom, indeed all over the world – in America, Australia, New Zealand, Africa, Spain, Portugal, France, Canada, Bermuda, Norway and Sweden.

The launching of the ‘buy-a-brick’ campaign in 1957 carried the Mermaid appeal across the world. Nearly 60,000 people have paid their half-crown for a brick in the venture.

There have been many delightful instances of individual generosity, many heart-touching stories of a very real and practical interest in the living theatre.

There is the old-age pensioner who write saying she would like to donate £5. Not having the ready cash, she asked to be allowed to subscribe on the ‘never-never’ – a down payment consisting of a savings book containing five shillings worth of 6d. savings stamps followed, and the installments are paid whenever she finds she has a bit to spare.

There is the 10-year-old boy in Hampstead who sent two half-crowns – ‘the profit I made on the pantomime Aladdin which I staged in my bedroom at Christmas’.

There is the man working next door to the theatre who every week for 2.5 years has clocked in to give his half-crown.

There is the school-girl who sent her 10 shilling birthday money – ‘It was given to me to spend on whatever I wanted most, and most of all I want four bricks in your theatre.”

There is the New Zealander who sent money for four ‘bricks’ on behalf of his ancestors who lived and worked in the City during the 18th and 19th centuries.

In addition to cash, covenants etc., the Mermaid has received many gifts of materials. Window frames, lavatory and wash basins, bricks, radiators, timber, electrical equipment, bars, tiles, piping, furniture, carpet. And the neighboring firms have helped by lending office accommodation and storage space; by donations of paper for our printing; by the free use of office machinery and facilities.”

A bit further up Puddle Dock and we can see where the entrance to the theatre dives under the 1980s office block:

Development of the Mermaid Theatre progressed as follows:

- OCTOBER 1956; The Mermaid Theatre Trust is granted a lease of a bombed site in Puddle Dock. It is decided to incorporate the existing 4-ft thick walls in the design and simply bridge them with a concrete barrel roof. An appeal is launched for the £60,000 needed to complete and equip the building.

- JULY 1957. Sufficient money has been collected for work to start on the site. An open-air concert is held on the site to mark the launching of the building programme. Artists include Amy Shuard, Denis Matthews, Harold Jackson, Larry Adler and Max Bygraves. Some 1000 people sat on park chairs on a bombed site open to the sky, and a mercifully fine evening gives a good send off to the Mermaid project.

- SEPTEMBER 1957. The Lord Mayor of London launches a ‘buy-a-brick’ campaign to raise further funds for the theatre. He throws the first half-crown into a trunk on the steps of the historic Royal Exchange and appeals to the rank and file of City workers to support the venture. The two-week campaign brings some of the biggest names in show business into the streets and pubs of the City selling ‘bricks’. Over £3,000 is raised,

- DECEMBER 1957. Work on the building advances. The site is a sea of scaffolding as work begins on the roof. Meanwhile the work of collecting money continues. Cheques roll in from the great mercantile exchanges, from banks and shipping companies, from stockbrokers, charitable trusts and insurance companies. From a host of firms and individuals.

- MARCH 1958. The roof is on, A roof-warming party is held on the site. A torch lit at the stage door of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane (London’s oldest theatre) is run through the streets to Puddle Dock by relays of the John Tiller Girls. on arrival at the Mermaid it is taken over by Norman Wisdom who casts it into the faggots beneath a 15-gallon cauldron of punch which is then served to the 1000 guests. Later, Norman joins the builders on the roof to drink a toast. Meanwhile, Sir Donald Wolfit, in a speech to the crowd, declares the roof ‘ well and truly no longer open’. The first stage of the building is complete.

- JUNE 1958. Members of the Moscow Art Theatre Company pay a visit to the site. At tables under the new roof they sit down to a traditional English meal – roast beef and ale from the wood. During their visit, the director of the company, Mr. A. Golodovnikov, traces the M.A.T.’s seagull emblem in a block of cement as a permanent reminder of the visit. The Mermaid is made an honorary member of the M.A.T.

- AUGUST 1958. the building is well advanced. the restaurant and dressing room area overlooking the river is nearing completion. Work has started on the seating ramp in the auditorium.

- APRIL 1959. The auditorium and restaurant are complete. Work continues in the foyer.

- MAY 1959. All is ready. A two year battle is won.

Before continuing with the story of the Mermaid Theatre, lets have a look at the location of the theatre, as the place today is very different compared to when the theatre opened in 1959.

The area around Puddle Dock was completely redeveloped in the late 1970s / early 1980s. New office blocks were built around the theatre, Puddle Dock was filled in, and replaced by the road that retains the name of the old dock, and the theatre was completely redeveloped.

This redevelopment resulted in the building that we see today, with a larger block to the south, overlooking the river, where the Mermaid Theatre restaurant and bar were located, the auditorium running back along the site of Puddle Dock, and the entrance to the theatre under the office block that spans Puddle Dock.

In the following photo, I am looking across the street Puddle Dock to the theatre entrance under the office block:

A close-up showing the glass windows of the entrance foyer, and a small passage running between the theatre and an office block to the left:

The late 1970s / early 1980s redevelopment of this whole area was significant, and included the reclamation of some of the Thames foreshore, and the rerouting of a historic London street.

The following map extract is from an early 1950s edition of the OS map. I have circled the word “ruin”, and this is the location of the ruined warehouse in the photo earlier in the post, and also the location of the Mermaid Theatre (Map ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

You will see that Upper Thames Street runs to the north of the ruined warehouse, and further along to where it joins Queen Victoria Street.

As part of the 1970s / 1980s redevelopment, the foreshore in front of the 1959 build of the Mermaid Theatre was reclaimed, and Upper Thames Street rerouted to run along this reclaimed land as a dual carriageway (the route of the red line in the above map), part of the Lower and Upper Thames Street changes that provided a dual carriageway from north of the Tower of London to join with the Embankment.

And where Upper Thames Street once ran – a typical Victorian street lined by large warehouses and offices, today, in front of the Mermaid Theatre, there is a short passageway. Upper Thames Street once ran along here:

A wider view:

When the Mermaid Theatre opened in 1959, the main entrance to the theatre was onto the original alignment of Upper Thames Street, where the short passageway is in the above photo.

The following photo shows the main entrance to the theatre, with Upper Thames Street (as confirmed by the street sign on the theatre) in front of the building – now a short, dark passageway:

if you walked into the entrance shown above, through the foyer and then into the auditorium, then this would have been your view down to the stage, with the original warehouse walls to left and right, and the new concrete roof above:

The view of the auditorium in the above photo may look rather basic, however at opening, the Mermaid Theatre had:

- 500 theatre seats on a single sharply-raked tier

- A stage of 48 feet wide by 28 feet deep

- An extensive stage lighting system

- The Mermaid was the first theatre in the country to have a stereophonic sound system, a donation from the Decca Record Company

- Restaurant and snack bars

- Eight dressing rooms with total accommodation for 50 to 60 actors. The dressing rooms were named after Wards of the City of London – Castle Baynard, Candlewick, Newgate, Cordwainer, Dowgate, Cripplegate, Broad Street and Queenhithe.

After opening, and throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the Mermaid Theatre was generally successful. An almost continuous run of different productions, apparently able to attract many of the leading actors of the time, as well as good audience numbers, although finances were always a challenge.

Bernard Miles and Josephine Wilson had the role of artistic directors, and Bernard Miles would occasionally also appear in one of the Mermaid’s productions.

The symbol of the Mermaid Theatre, on all their programmes, advertising etc., from the 1959 opening, was a mermaid, as shown on the cover of the programme for the 1972 production of Noel Coward’s Cowardy Custard:

The Mermaid was often struggling financially, so as well as the revenue from ticket sales, the theatre was always looking for additional sources of revenue, and as with theatres today, food and drink made up a large part of this.

In the Mermaid Theatre, there was the Riverside Restaurant, the Tavern Restaurant, the Whitbread Bar, the Charrington Bar and a Snack Bar:

The cast list from the 1972 production of Cowardy Custard:

When the area around the Mermaid Theatre was redeveloped, the theatre had to close for an extended period of time. This work involved the reclamation of the foreshore, build of a new embankment and the move of Upper Thames Street from the north of the theatre to the new dual carriageway to the south, filling in Puddle Dock, and build of the new road alongside the theatre, and the build of all the new office blocks that today surround the theatre.

The new route of Upper Thames Street is shown by the red line on the earlier OS map extract.

Bernard Miles was able to get some support for the rebuild of the Mermaid Theatre out of the developers of all the change, and this resulted in the slightly enlarged theatre building that we see today. However it also cost the Mermaid a considerable sum of money, and in the programmes that went with their early 1980s productions, they advertised the:

“MERMAID APPEAL – The Mermaid Theatre Trust offers warn thanks to those who have contributed in cash and in kind to the rejuvenation of the theatre. BUT, the hard winter of 1979 and the medieval and Victorian obstacles underground slowed up our rebuilding and combined with inflation to push up the cost of completing our existing building by £100,000. PLEASE HELP TO TOP US UP.”

The medieval and Victorian obstacles underground highlights that when the 1959 Mermaid was built, it was mainly built within the ruins of an existing building, and there was no need to go down below the surface for the majority of construction work.

When the Mermaid reopened in 1981, the first production was a musical version of the 17th century play Eastward Ho. This was a financial disaster and lost £80,000, and over the next two years, losses kept increasing to reach a total of £650,000.

One of the 1981 productions was “Children Of A Lesser God”, which opened on the 25th of August, 1981:

Which starred Trevor Eve, Elizabeth Quinn, and Irene Sutcliffe:

The above programme was one of the last to list Bernard Miles and his wife Josephine Wilson as Artistic Directors.

Two years after reopening, debts were so bad that the Trustees were forced to put the Mermaid up for sale.

Bernard Miles and Josephine Wilson stepped down as Artistic Directors.

The Mermaid Theatre was purchased by Ugandan Asian businessman Abdul Shamji through his property company Gomba Holdings.

Shamji was sentenced to 15 months imprisonment in 1989 following the collapse of the Johnson Matthey Bank, and the Mermaid Theatre then went through a series of different owners, and with different artistic directors and managers, however the theatre never reached the success in terms of productions, actors and audiences that it had done under Bernard Miles (although it had always struggled financially).

In 2000 it was basically a redundant building, and in 2002 it was scheduled for demolition as part of a redevelopment plan for the area (which never materialised), and in 2003 the Mayor of London blocked any demolition.

The theatre was used for a number of BBC concerts, and the formal end of the building as a theatre came in 2008 when the Corporation of London City Planning Committee removed the theatre license from the Mermaid Theatre.

When the Mermaid was opened in 1959, it was the first theatre in the City of London for almost 300 years, by the time the theatre was redundant, the City of London had a theatre at the Barbican, so there was probably no perceived need to, or interest in financially supporting the smaller Mermaid.

The building was then turned into an exhibition and conference centre, a role it continues to this day

Bernard Miles was recognised for his work both as an actor and with the Mermaid Theatre as in 1953 he was made a CBE, he was knighted in 1969 and in 1979 he was made a Life Peer as Lord Miles of Blackfriars in the City of London.

His choice as being titled “Lord Miles of Blackfriars” probably indicates his deep connection with Blackfriars and the Mermaid.

Whilst the Mermaid building is a reminder of Bernard Miles’ original dream of a new theatre in the City of London, there is almost nothing to remember Bernard Miles or Josephine Wilson around Puddle Dock.

The one exception requires a walk up to the walkway on Baynard House (one of the office blocks that were built as part of the major redevlopment of the area – the walkway can be accessed from stairs on Queen Victoria Street, and provides access to Blackfriars Station).

In this gradually decaying space can be found the Seven Ages of Man sculpture by Richard Kindersly:

A plaque on one of the side plinths near the sculpture records that the work was unveiled by Lord Miles of Blackfriars on the 23rd of April, 1980:

Bernard Miles continued to act after stepping down from the Mermaid Theatre, but these roles must have been difficult given his previous 30 years involvement with the Mermaid, from the initial idea through to stepping down as artistic director.

In 1983, he took on the role of Firs, the old retainer, in Lindsay Anderson’s production of the Cherry Orchard, at the same time as what could have been considered his very own cherry orchard, the Mermaid, was being sold.

Bernard Miles and his wife Josephine Wilson had put almost all their own money into the Mermaid Theatre, and in 1989 they had to move from their four bedroomed house in Canonbury to a flat.

Josephine died in 1990, she had been Bernard Mile’s strongest and most consistent supporter throughout their life together, and during the whole period of the Mermaid, from the original idea through to the loss of their roles with the theatre.

After the death of his wife, Bernard moved into a Middlesex nursing home, and it was rumoured that he only had his state pension to live on.

The Mermaid Theatre’s new management staged a gala benefit in his honour, and despite being confined to a wheel chair, and also partially deaf, we was able to hear the many tributes that were paid to him, whilst in the theatre that had been his main life’s work.

Bernard Miles died on the 14th of June, 1991. Obituaries after his death celebrate his role in the founding of the Mermaid Theatre and the challenges that he overcame in getting the idea of the theatre from a bomb damaged warehouse through to a working theatre in the City of London.

They also identify a number of shortcomings, that perhaps he never recognised his shortcomings as an actor, that he wanted to take on the great roles of theatre, but in the words of one obituary “he played them and was terrible in all of them”.

He was strongly loyal to his old actor and director friends, but again was blind to their inadequacies.

He also failed to listen to advice when he had an idea and wanted to see it through, which was one of the reasons why the Mermaid frequently struggled financially.

Despite these shortcomings, he was widely remembered with affection and for his achievement in bringing the Mermaid to the City of London, long before the Royal Shakespeare Company were established at the Barbican.

I have tried to visit the Mermaid, and to take some photos, however there has been no response to my requests.

A walk around the outside of the theatre shows the Mermaid surrounded by the developments of the 1970s / 80s, but this could all change as there are proposals for a wholesale redevelopment of the area, and it is one part of London that does need to change – one of the most unfriendly pedestrian places you will find in the City of London.

Nothing appears to remain from before the theatre was built (although I would love to know what is underneath the Mermaid), however I did find these two strange red painted metal objects to either side of one of the doors to the theatre:

They appear to be made of iron, and are completly out of place with their surroundings. Two thirds of the way up, there is a slot on both objects, the type of slot that looks as if a wooden plank would have been inserted to bar the way.

It would be interesting to know if these are survivors from the time before the Mermaid was built.

The Mermaid Theatre is a fascinating story of how one man’s single minded devotion to an idea, led to the founding of the first new theatre in the City of London in almost 300 years, and in many ways, also led to its downfall.

I hope in the redevelopment of the area, the story of Bernard Miles, Josephine Wilson, and the Mermaid Theatre does not get lost.

You may also be interested in my post on Puddle Dock And a City Laystall, and Queen Victoria Street and Upper Thames Street – A Lost Road Junction.

I will also be running the walk “The Lost Landscape and Transformation of Puddle Dock and Thames Street” in the summer of next year. Follow here on Eventbrite to get updates when new walks are available.