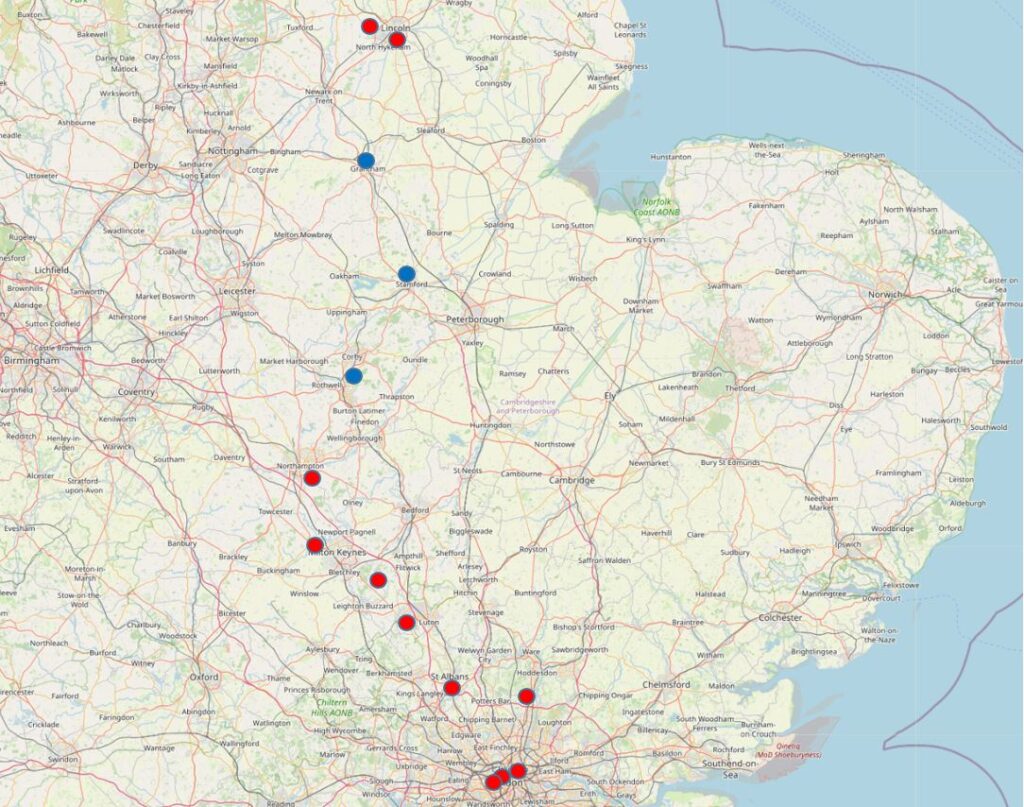

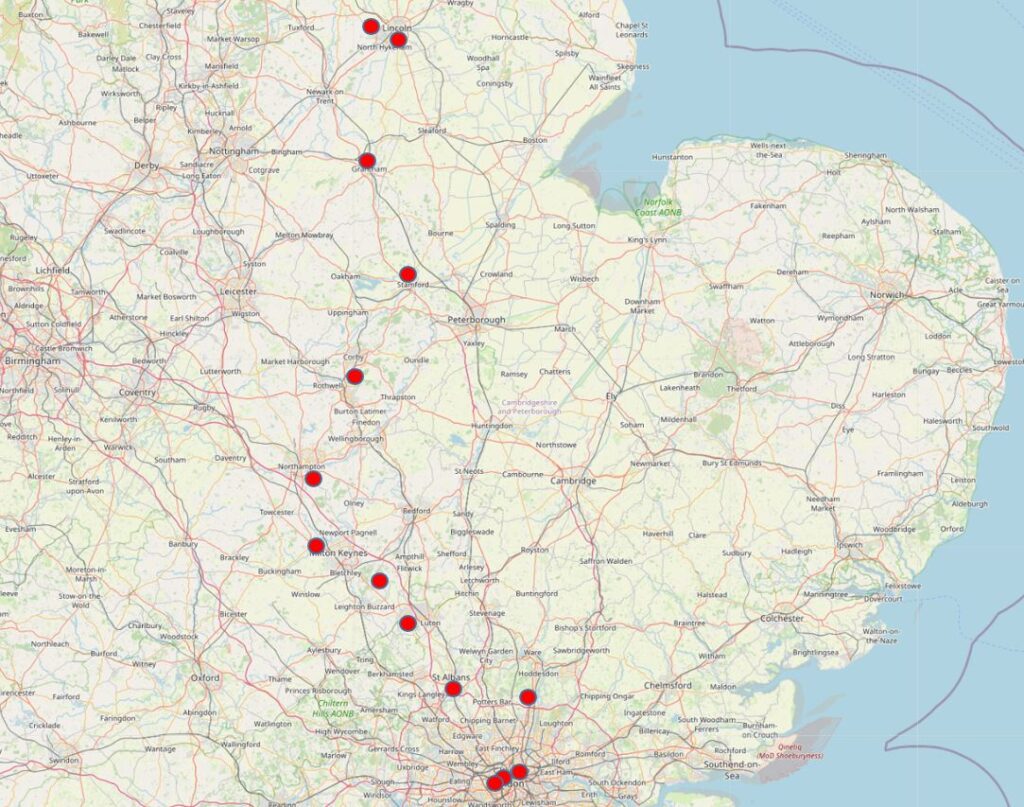

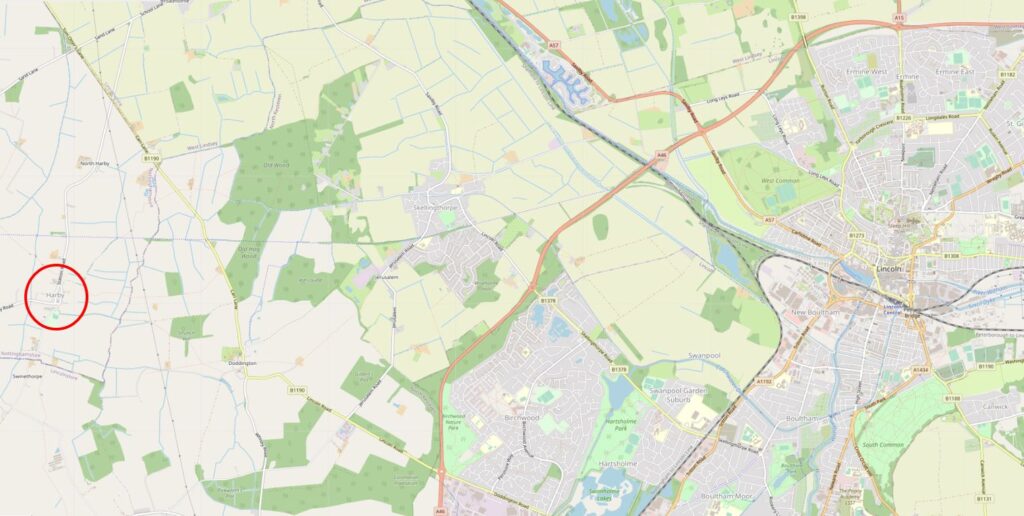

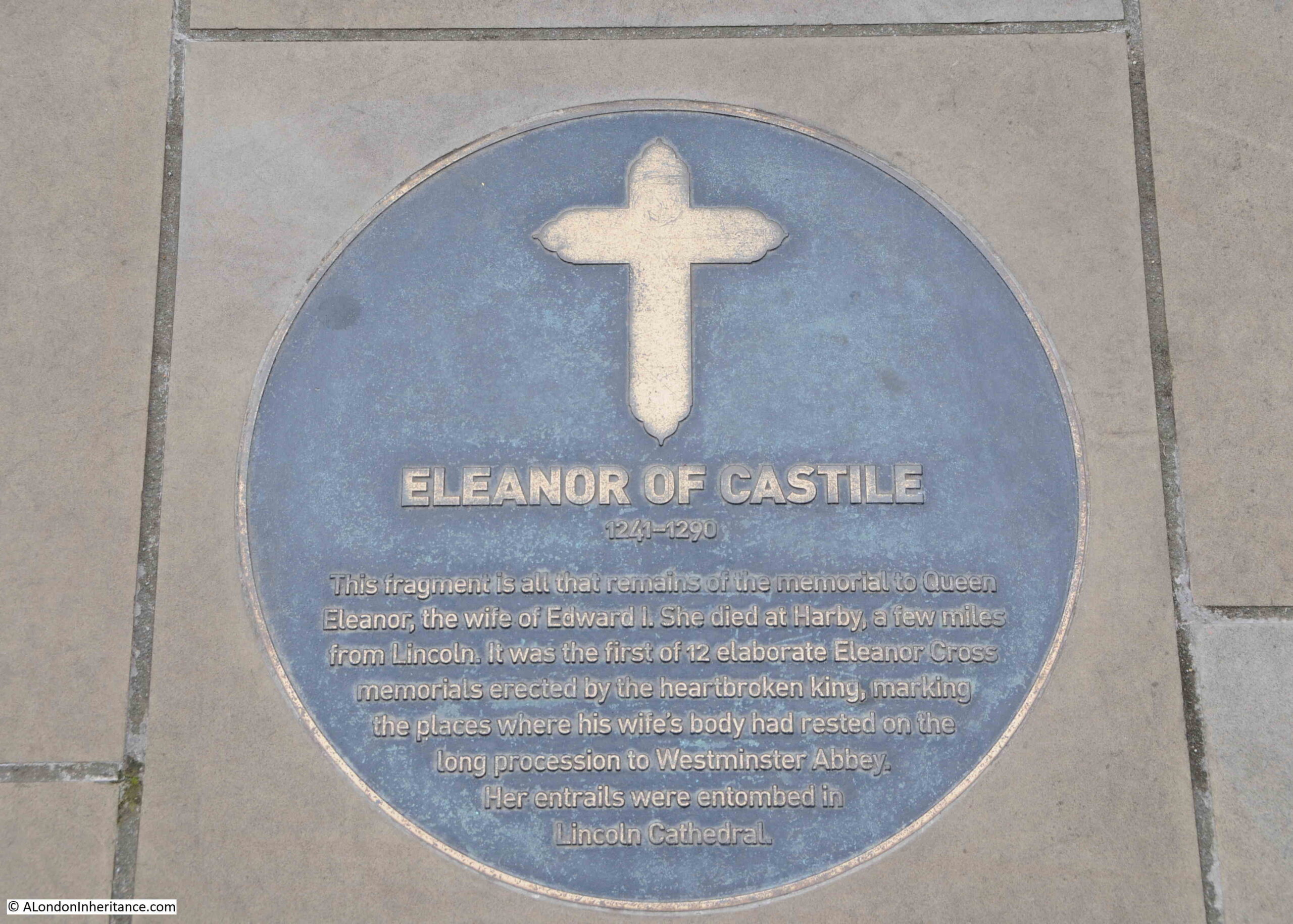

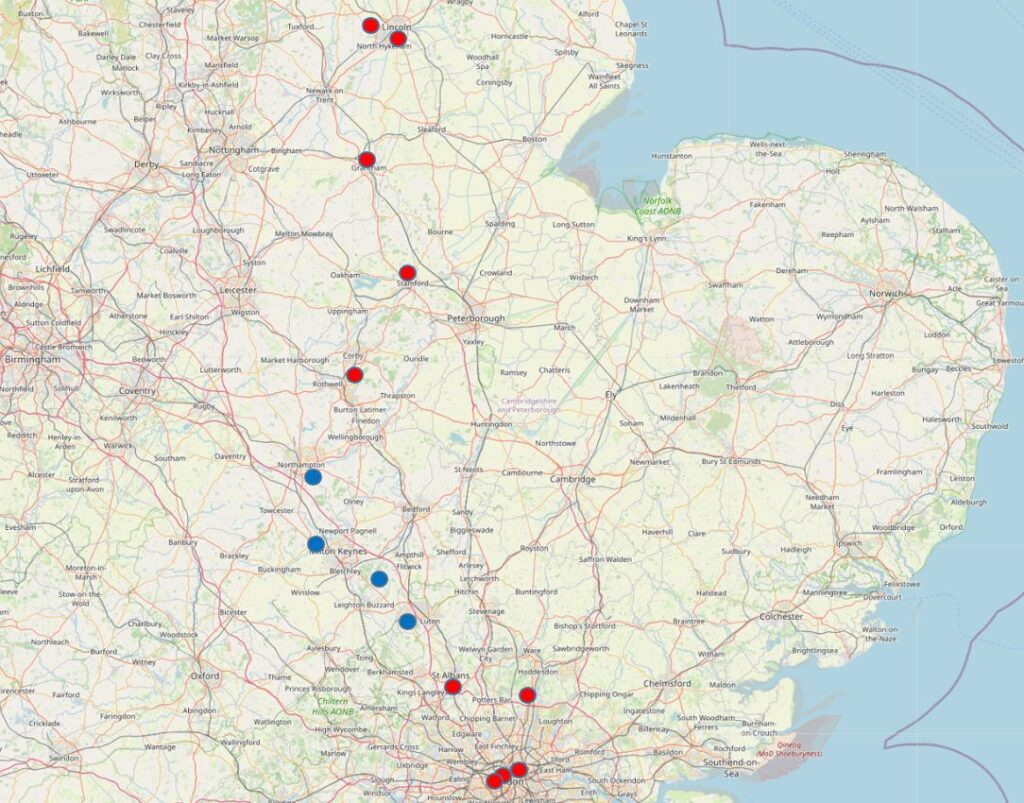

Having left Geddington in the last post, today’s post will visit the next four sites where the procession taking Eleanor of Castile’s body to Westminster Abbey stopped overnight. The stops are shown as blue dots in the following map and are at Hardingstone, Stony Stratford, Woburn and Dunstable (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Leaving Geddington, the procession headed towards:

Hardingstone

Just south of Northampton, Google maps shows this as a distance of 22 miles, however they probably went through Kettering rather than taking the bypass, so the distance was around 20 miles.

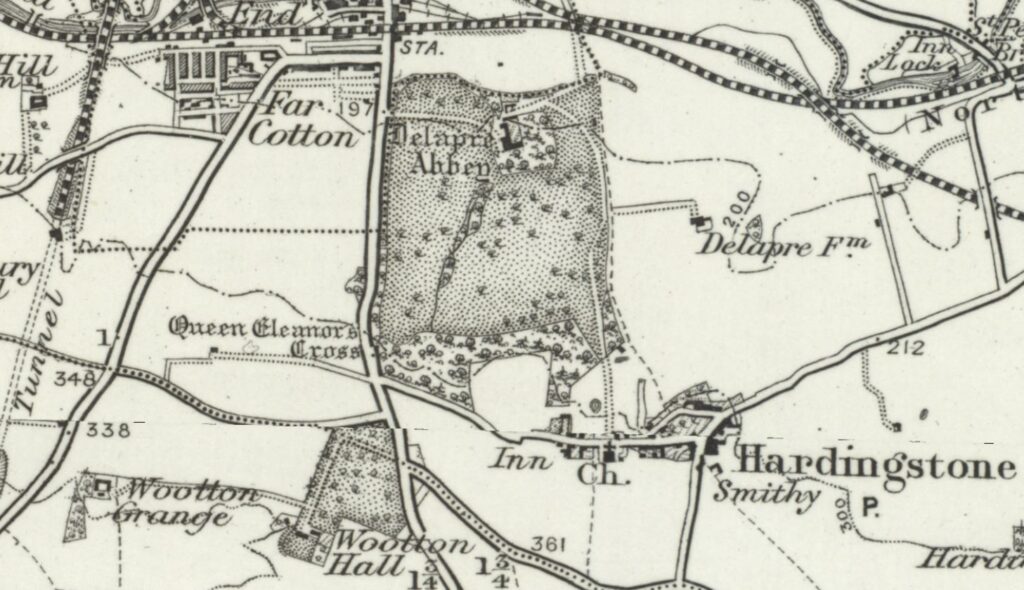

Hardingstone has now been swallowed up in the suburbs of Northamption, but in 1290 it was a very small village, and the destination of the procession was Delapre Abbey, to the south of Northampton, and north-west of Hardingstone.

Delapre Abbey was founded around the year 1145. It was a Cluniac nunnery, which followed the Benedictine Cluny Abbey in France.

In 1290, the abbess was Margery de Wolaston, and she would have looked after Eleanor’s coffin and arranged for prayers to be said throughout the night. Being a nunnery, Edward would have been unable to stay, so he retired to Northampton Castle for the night.

A cross was built, not in the grounds of the nunnery, but on a high point alongside a road that ran along the western perimeter of the nunnery’s grounds.

That road today is the A508, with the name of London Road, implying that it was the main road leading out of Northampton in the direction of London.

Travelling along the A508, it was easy to spot the Eleanor Cross:

The Hardingstone cross is one of the few survivors, and although it has lost the very top of the cross, it is still an incredibly impressive monument, and is more substantial than the Geddington cross.

Possibly because of their care of Eleanor’s body, Edward I gave the abbess a grant of royal protection in 1294, although by 1300 the abbey’s standards seemed to have slipped as according to the Victoria County History edition for Northampton, “The bishop in 1300 issued a mandate to the archdeacon of Northampton to denounce Isabel de Clouville, Maud Rychemers, and Ermentrude de Newark, professed nuns of Delapré, who had discarded the habit of religion and notoriously lived a secular life, as apostate nuns, also to inquire as to who had aided them in their apostasy.”

The abbey was surrendered to the Crown in 1538 during the dissolution of the monasteries, and a few years later it was in private ownership where it would remain for the next few centuries.

Northampton Corporation purchased the building in 1946, and the building soon housed the County Records Office. It is now owned by the Friends of Delapré Abbey, and is open to visit.

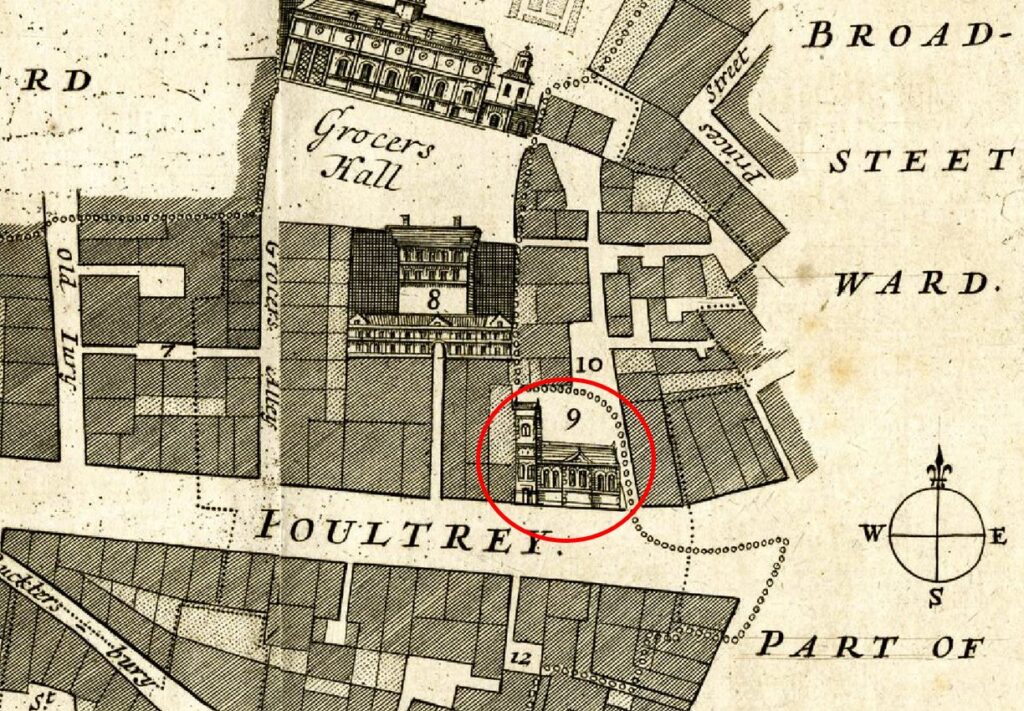

In the 1897 revision of the Ordnance Survey, Delapre Abbey is shown, with Queen Eleanor’s Cross marked towards the lower left of the abbey grounds. The village of Hardingstone is lower right. Apart from the abbey grounds, today, much of this area of the map has been built over (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“).

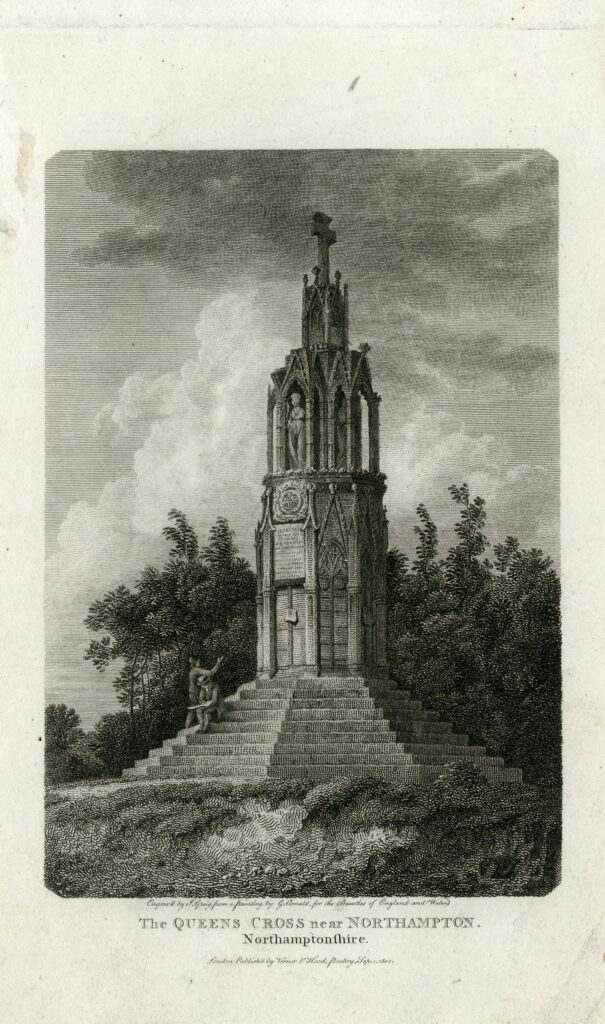

The following print shows the Eleanor Cross, when there was still a cross at the very top. The print is dated 1802 (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

The cross is missing in this photo from later in the 19th century (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

I crossed over the London Road to take a closer look.

There is a plinth on the grass which adds some confusion to the top of the cross as it states that “The design of the original top is unknown. the present broken shaft having been placed in position in 1840”. I am not sure how that works with the earlier print, and whether there was a cross on the top when the print was made, or whether this was some artistic license being used.

On the wall to the side of the cross, along the edge of the old grounds of Delapre Abbey, there is a set of stones:

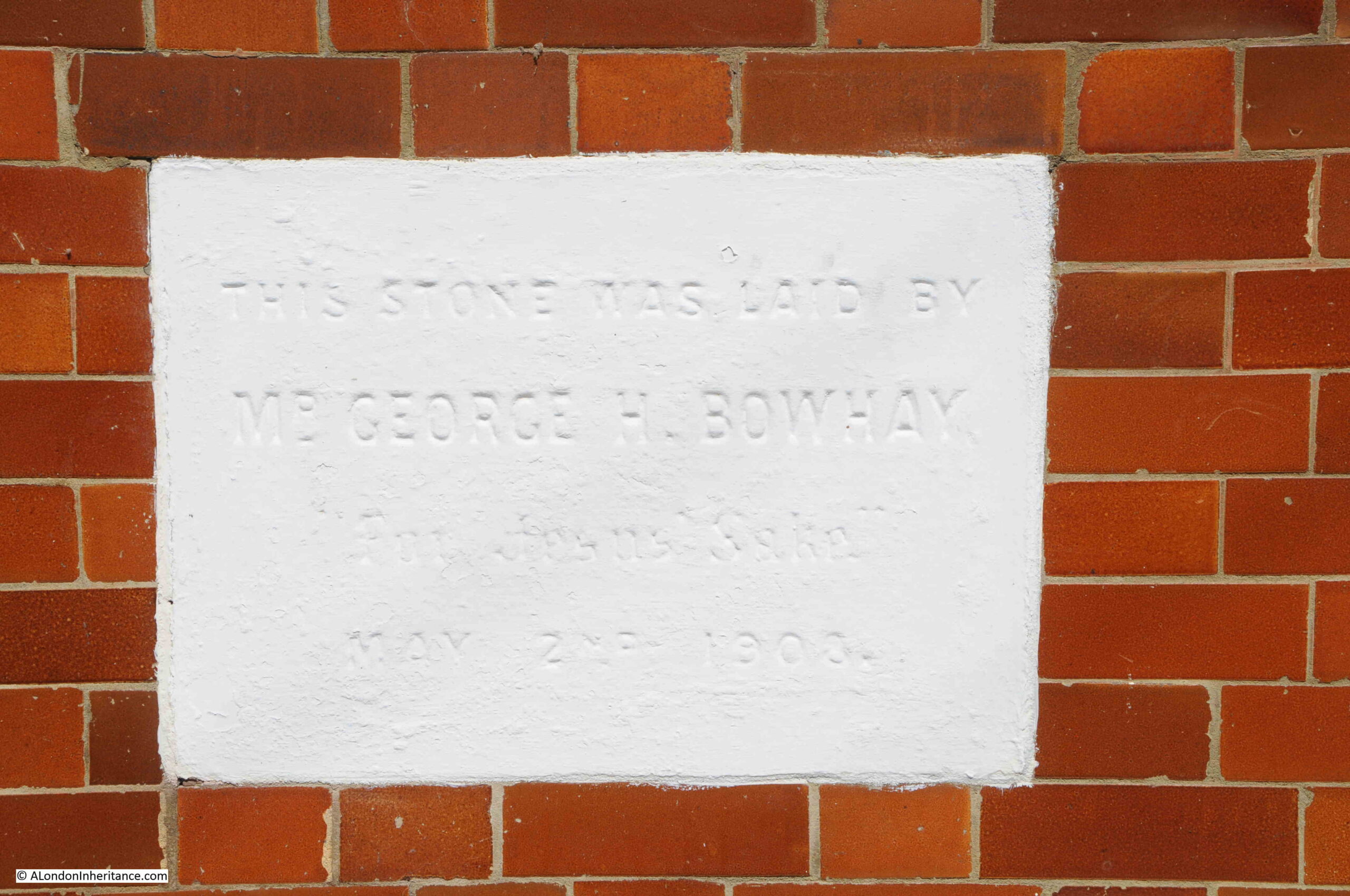

The large stone on the left of the panel has some very faded text. Fortunently, the panel at the top has a copy of the text:

“In everlasting memory of conjugal love, the honourable assembly of judges of the County of Northampton resolved to restore this monument to Queen Eleanor when it had nearly fallen down by reason of age in that most auspicious year 1713 in which Anne, the Glory of Mighty Britain, the most powerful avenger of the oppressed, the arbitress of peace and war, after Germany had been set free, Belgium made more secure in her defences, the French overcome in more than ten battles by her own and by the arms of her allies, made an end of conquering and restored peace to Europe after she had given it freedom.”

Well that confirms that the cross was significantly repaired in 1713, followed by some major crawling to Queen Anne.

The panel also states that the three stones to the right are the original stones from around 1291 when the cross was built, removed from the cross during restoration in 1984. The stones were the bases for three of the statues of Eleanor.

The text from 1713 starts with “In everlasting memory of conjugal love“, and it is the love between Eleanor and Edward that has really defined their story.

Royal marriages were almost always marriages aimed at establishing relationships between different royal families, to cement alliances, to prevent war etc. They were very rarely for love, and although Eleanor and Edward’s marriage was arranged for them, and they were incredibly young at the time, they do appear to have been devoted to each other.

Very unusually for medieval Kings, Edward I appears to have been faithful to Eleanor. He did not have any mistresses which was considered normal practice at the time.

Eleanor travelled widely with Edward, including when in 1270 Edward left the country to join the French King Louis IX on Crusade.

The French King died of the plaque before Edward could join him, so Edward continued to Acre (in what is now Israel) to free the city from Islamic control.

Edward’s force was relatively small, so had very little success, and he had to agree a truce with the Baibars or Baybers – Egyptian rulers of much of the eastern Mediterranean.

During his time in the middle east, he narrowly survived a murder attempt, when he was stabbed by a dagger which was believed to be poisoned. The person who attempted to murder Edward was an Assassin, from an order or sect of Shia Islam that existed middle ages, and from where the term used to describe a hired or professional murderer has come from.

Edward and Eleanor left Acre for Sicily, and it was here that news finally reached them that Edward’s father, Henry III had died on the 16th of November 1272.

On the death of a king, what would frequently happen was a rush back to one of the main centers of Royal power, such as London or Winchester to claim the throne. This was a time when there were often many competing claimants for the throne, however Edward as the eldest son of Henry III, and because of the way he had supported his father during many previous rebellions, and his exploits on Crusade, was proclaimed King in his absence, and it would be just under two years before he finally arrived back in London and where he was crowned at Westminster Abbey in August 1274.

Eleanor has been with Edward during all this time away on Crusade, whilst in Sicily, and on the journey back

Returning to the Hardingstone Cross, and it has the same recurring features that are found on many other original or later monuments to Eleanor.

The arms of England, Eleanor of Castile and the arms of Ponthieu:

Whilst the Hardingstone cross is more substantial than the cross at Geddington, it follows the standard design of having a lower section with coats of arms, with above a section with statues of Eleanor. I assume due to the wearing of the stone, these statues are original, and they have been looking out from the cross for around 730 years:

The Hardingstone cross is a remarkable survivor and an unusual sight for those travelling along the A508. A reminder of the area’s medieval history.

Leaving Hardingstone, the next stop is:

Stony Stratford

I have read some accounts that state that the stop at Stony Stratford was not the intended destination for the night, and that the procession had planned to continue on to Woburn. Stony Stratford is a short journey of around 14 miles from Hardingstone, much shorter than the typical 20 miles a day that the procession had been achieving.

As with some of the other places on the journey, Stony Stratford is the location of a crossing point over a river, the River Great Ouse, so it may be the crossing that dictated the route via the town, as well as the road that runs through the town.

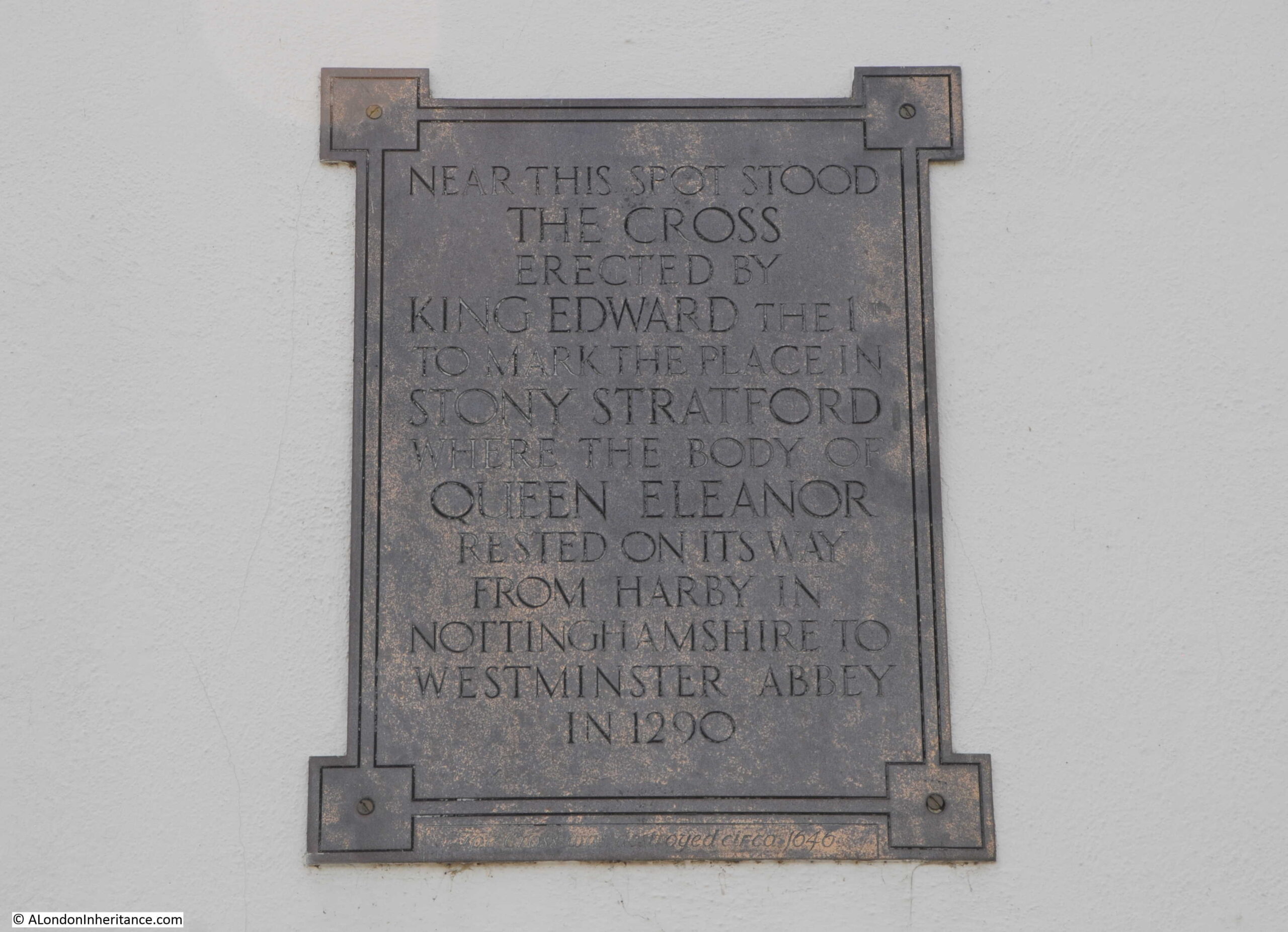

There is no record as to where either Edward or Eleanor’s body stayed during the stop in Stony Stratford. A cross was built here between 1291 and 1293 by John of Battle, however it was destroyed during the English Civil War and there is nothing left of the cross today. There is a plaque on a building marking roughly where the cross was located, towards the northern end of the main street, so stopping in Stony Stratford, the plaque was my first destination, seen in the following photo on the white wall:

Details of the plaque:

Stony Stratford is a wonderful town, with a very long high street. I have not been here since the late 1970s when as a BT apprentice I was training at nearby Bletchley and the pubs of Stony Stratford were an attraction.

The view along Stony Stratford High Street:

Stony Stratford is one of those towns, like Grantham in the previous post, that is on a major, long distance road. Before being bypassed, the A5 ran through Stony Stratford.

The A5 runs from Marble Arch, through Shrewsbury, and on to the Holyhead ferry terminal in Anglesey. This latter part was an extension of the road in the early 19th century by Thomas Telford.

For this reason, Stony Stratford has a number of large hotels and inns which would have been coaching inns when stagecoaches passed through the town. One of these is the Cock Hotel:

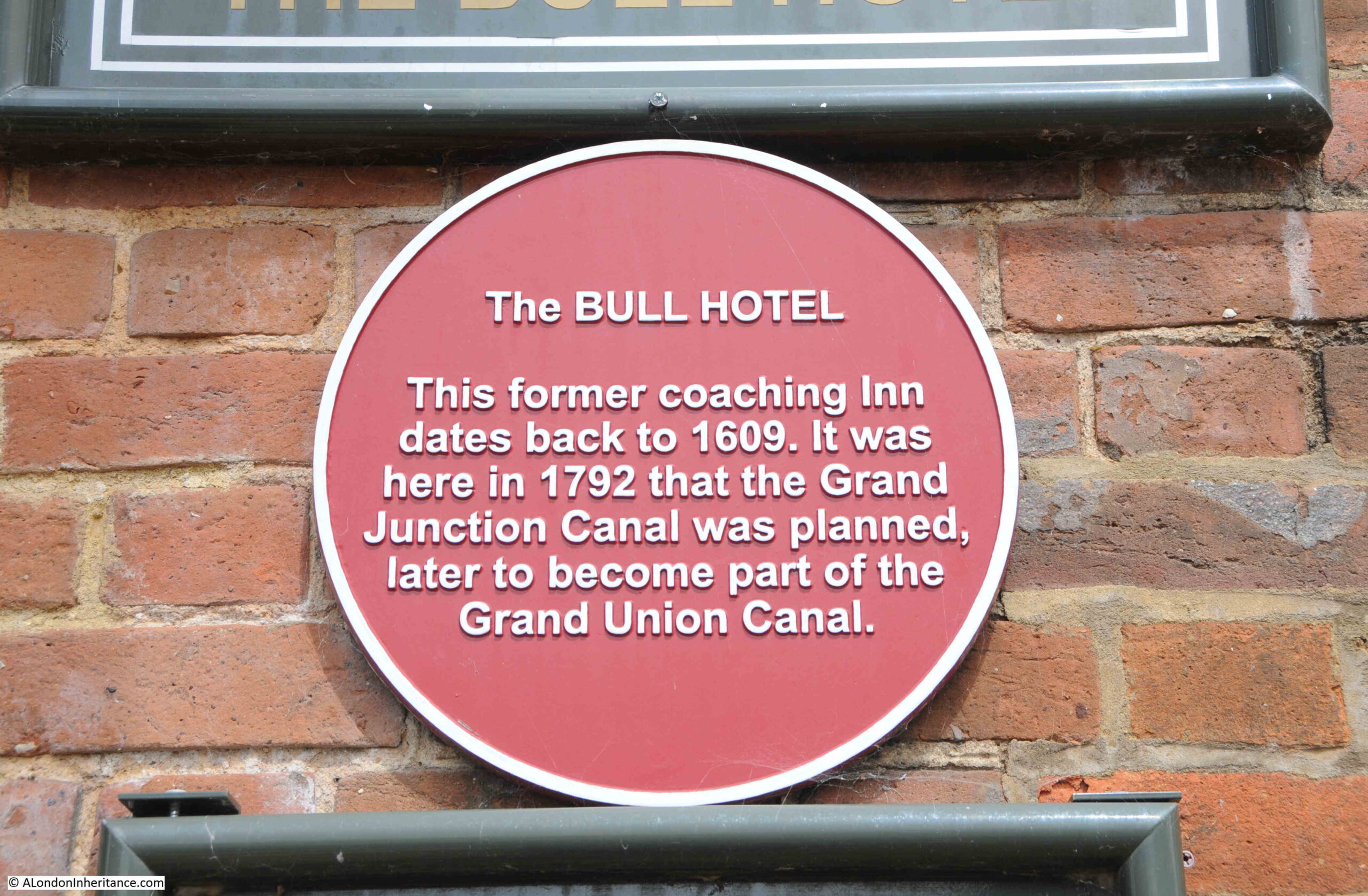

Another is the Bull Hotel:

Which has a plaque on the wall recording the age of the hotel and a link with the Grand Union Canal:

Stony Stratford also has some wonderful shops, including Odell & Co, the type of hardware store that has many of their products on view on the pavement outside:

The Old George, an old pub which has a secret that explains why the A5 runs through Stony Stratford:

A plaque on the side of the pub explains that the ground floor dates from 1609 and remains at the original Watling Street road level:

Watling Street is an incredibly old road, parts of which may predate the Roman period, but it was the Roman’s that established the road as a paved route from Dover, passing by Reculver, crossing the Thames in London, then heading up to Wroxeter. (I wrote about Reculver here, and Wroxeter here).

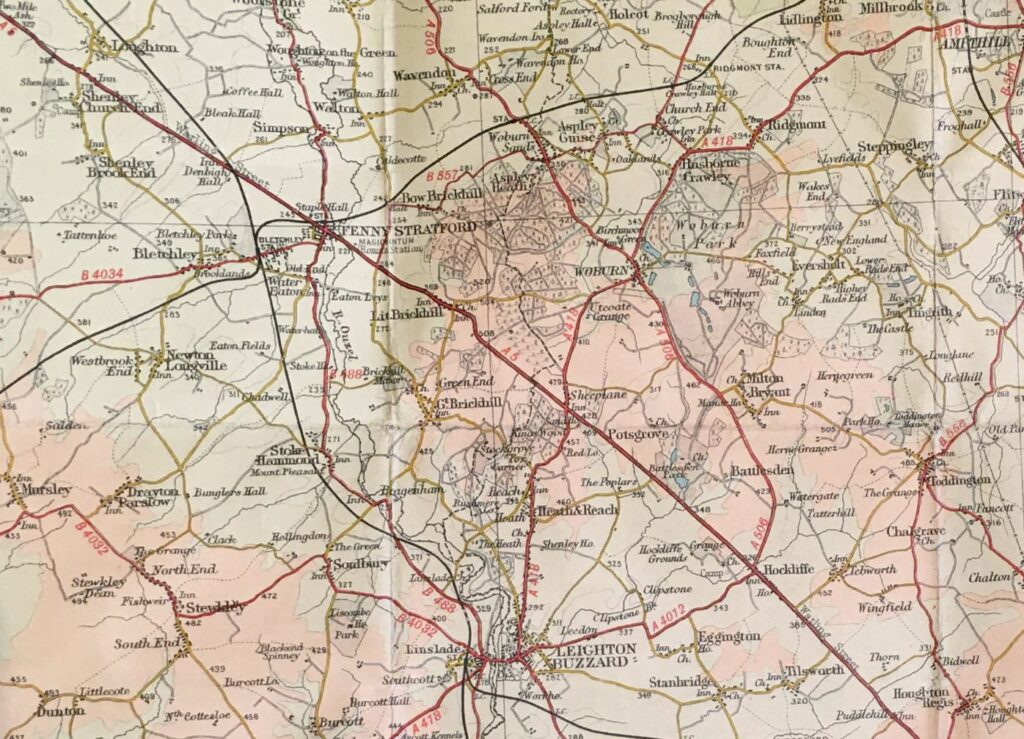

The area to the south west of Stony Stratford is now extremely built up, as this was the site where the new town of Milton Keynes was built. The street that was Watling Street, and then the A5 is now partly buried within the Milton Keynes development, however if we look at one of the old Bartholomew Contour maps of the country, we can see Watling Street as one of the easily identifiable, very straight, Roman roads.

In the following extract, Stony Stratford is just off the top left corner (it was just on the edge of a different map), and Watling Street can be seen running diagonally across the map from top left to bottom right:

The A5 / Watling Street was an important road for centuries, and is why Stony Stratford High Street is long and straight and is why the town has so many large inns and hotels.

There is another plaque on a building that was once a pub:

Where the plaque tells another Royal story that has touched Stony Stratford:

Stony Stratford is a wonderful, historic town, however the 21st century does roam the streets, in the form of Starship delivery robots, following their 2020 launch in Northampton, and expansion across towns in the area.

Leaving Stony Stratford, the procession with Eleanor’s body continued south on the A5 / Watling Street, and then made a small detour to head to:

Woburn

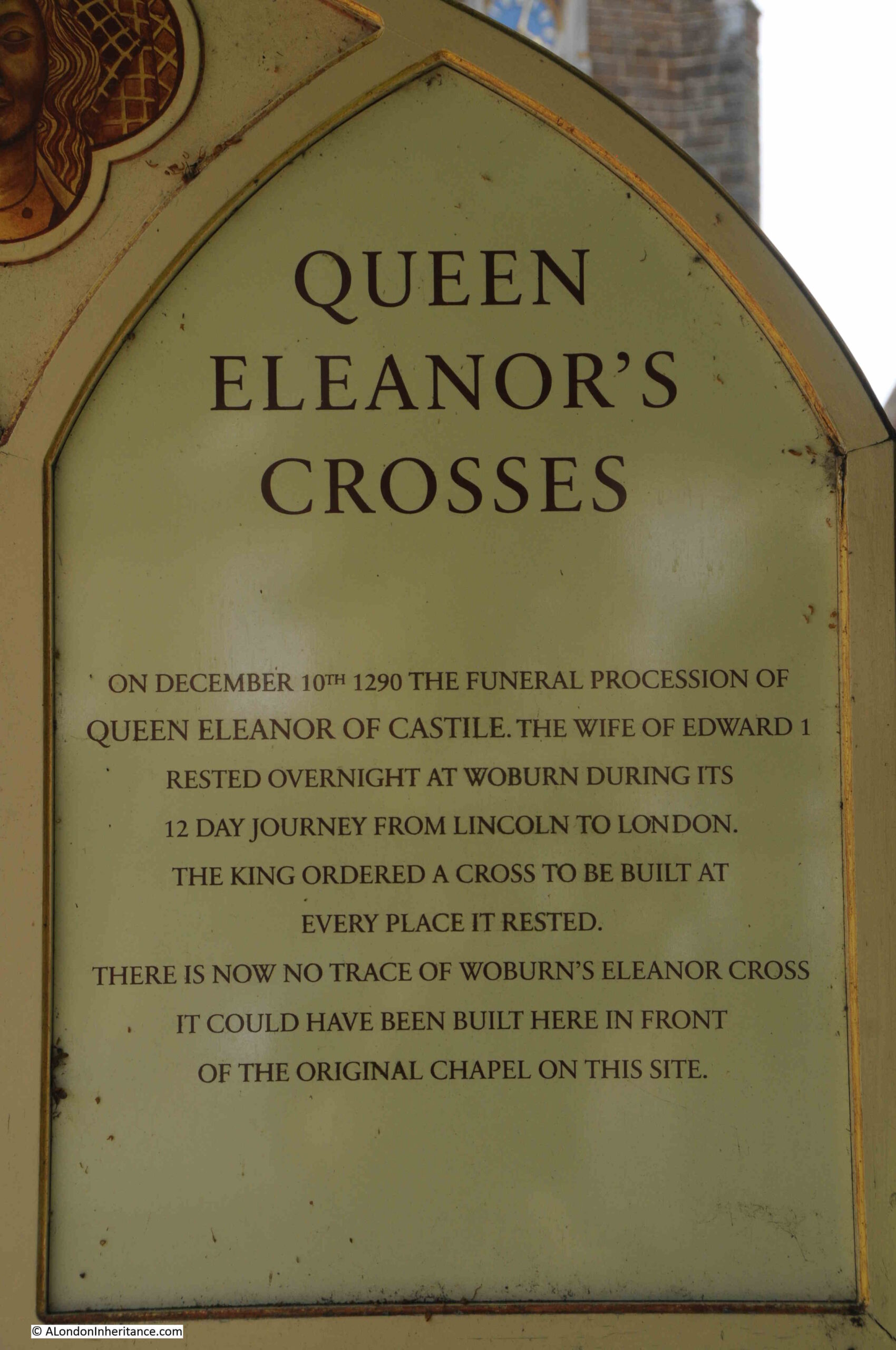

The destination was Woburn Abbey, a Cistercian monastic establishment founded in 1145. The Eleanor Cross marking the overnight stay in Woburn has disappeared, and there is no record of its appearance or a confirmed location.

One place to visit in the town to find a reference to the cross is the old St. Mary’s church which is now run by the Woburn Heritage Centre Trust:

Where there is a sign by the entrance that records Eleanor’s stop in Woburn, and that the cross could have been built in frount of the chapel that was originally on the site of the current church building:

Woburn Abbey, where the body is believed to have stayed overnight, and which is the obvious location being a religious establishment, lasted until the mid-16th century, when it was taken by Henry VIII during the dissolution of the monasteries.

In 1290, Woburn Abbey was a Cistercian monastic establishment and had been founded in 1145.

Henry VIII gave the property and the surrounding lands to John Russell, the 1st Earl of Bedford, and the lands and house that was built following the demolition of the original abbey buildings, is still in the possession of the Russell family. A prime example of how many large land owners today, owe their holdings to being in favour with the monarch in previous centuries.

The Russell family have very many London connections, for example with the development of parts of Bloomsbury, and with locations such as Russell Square, named after the Russell family, which I wrote about here.

Woburn has a wonderful high street, mainly built of brick:

Many of the buildings in Woburn have a listing, and the building in the centre of the following photo with the Woburn China Shop is Grade II listed:

The majority of buildings to left and right of the following photo are also Grade II listed:

After leaving Woburn Abbey, the procession must have returned to the A5 / Watling Street and continued on the route to London for the next overnight stop at:

Dunstable

As with Stony Stratford, the original A5 / Watling Street ran through the town of Dunstable, and although now partly by-passed by the M1, the main street through Dunstable remains very busy.

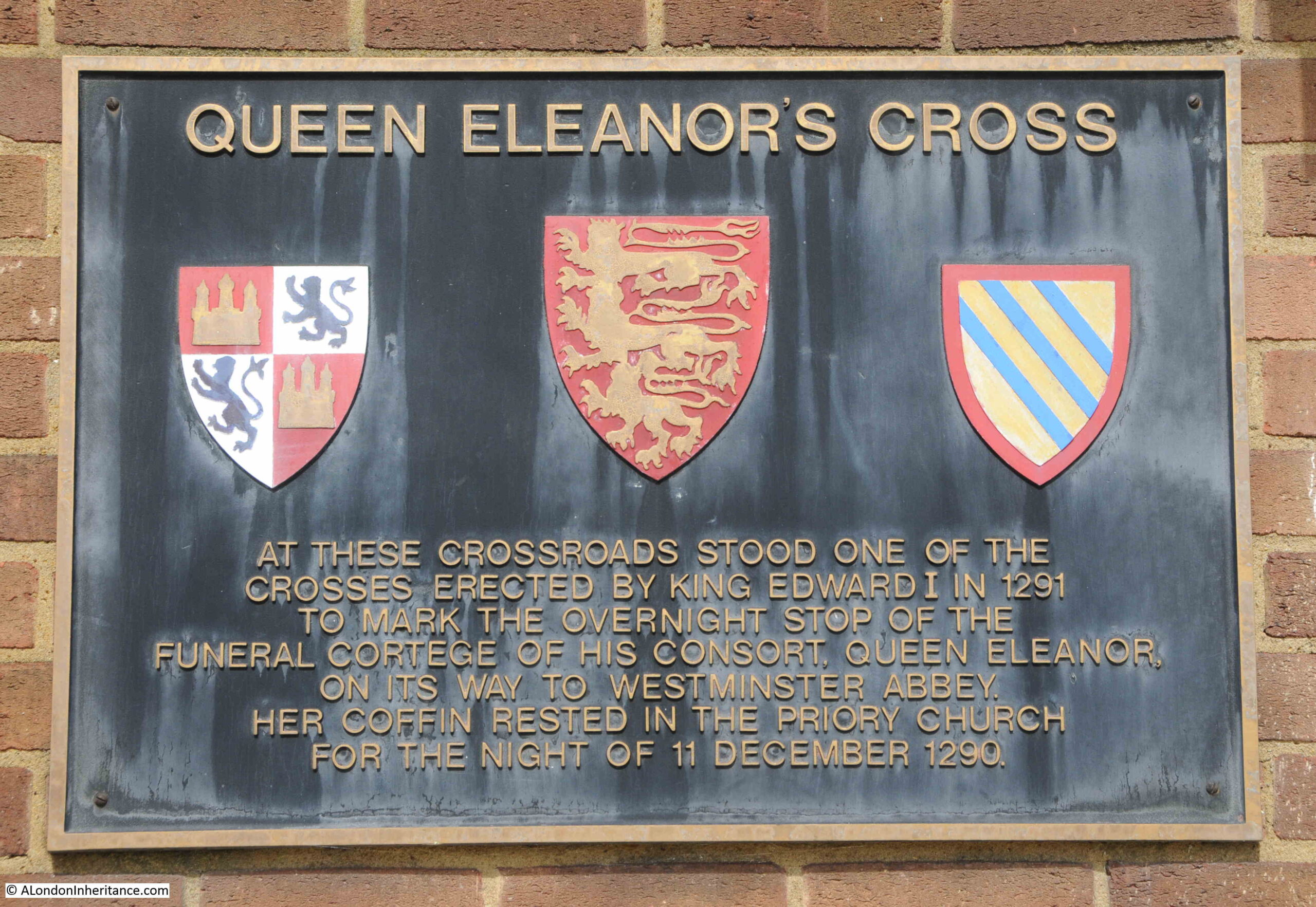

There are no remains of the Eleanor Cross built in the town, however there is a plaque recording the approximate location. There is a large cross roads to the south of the town, and the following photo was taken from the south west corner of the cross roads, looking at the NatWest Bank on the opposite corner.

A plaque can just be seen in the above photo, to the left of the NatWest Building.

This plaque records that the cross roads was the site of an Eleanor Cross, built between 1291 and 1291 by John of Battle.

William Camden, the 16th / 17th century antiquarian, recorded the cross as being engraved with heraldic arms and statues of Eleanor, so as the cross was built by the same stone mason as earlier crosses, and based on William Camden’s description, it must have been very similar to the cross at Hardingstone.

The cross was destroyed during the Civil War by soldiers of Sir Thomas Fairfax, who was Lord General of the New Model Army.

The plaque records that Eleanor’s body rested in the Priory Church for the night of the 11th of December 1290.

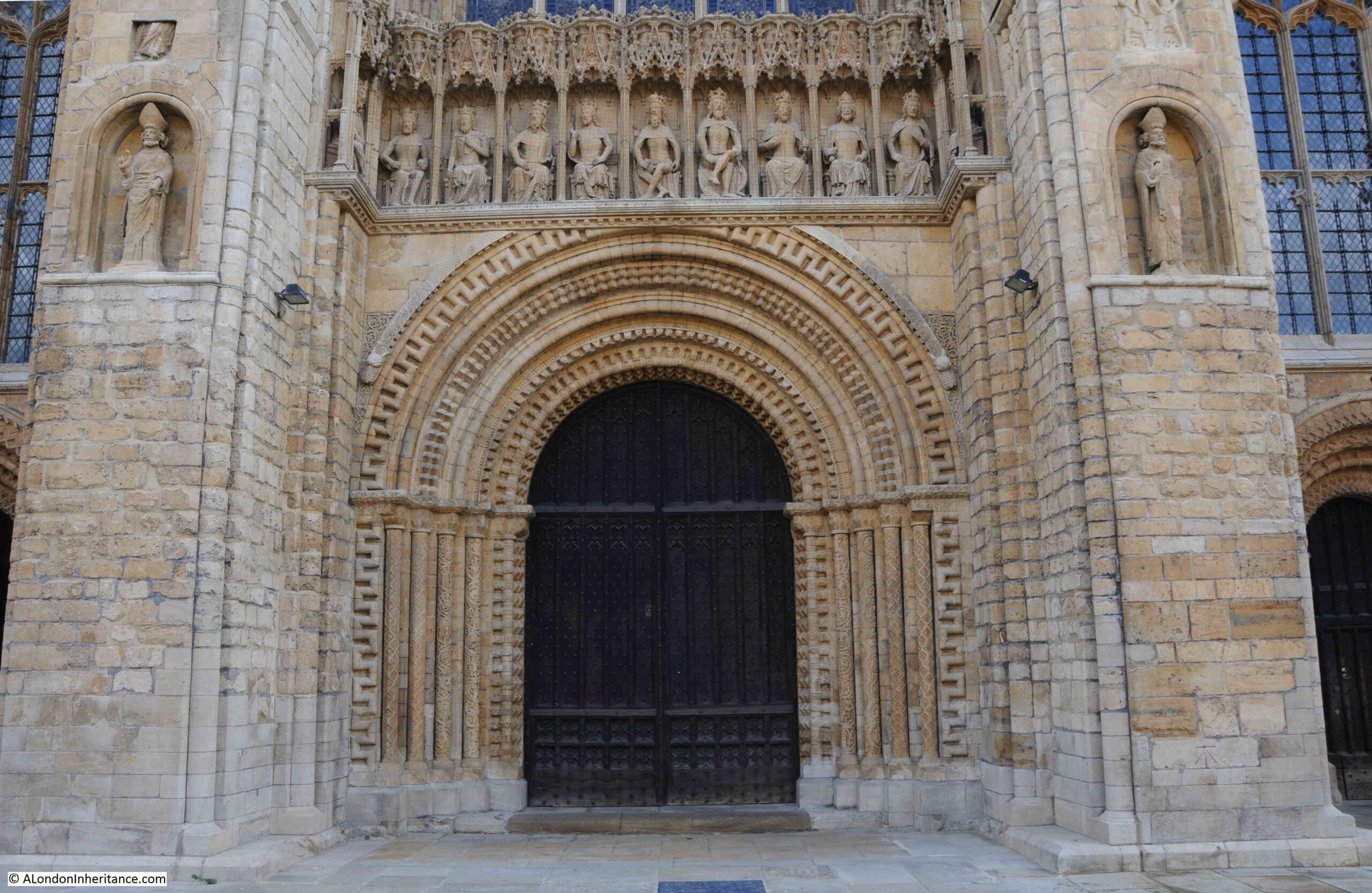

Part of the Priory Church of Dunstable Priory still remains and it would have been in the following church where Eleanor’s body rested:

The Priory Church looks incredibly impressive today, but it is only part of the original church (the nave), which in turn was part of the overall priory buildings and grounds.

Dunstable Priory had been founded in 1132 as an Augustinian monastic establishment. It really is remarkable how many religious properties there were across the country in the medieval period, however as with so many others, Dunstable Priory was taken by the Crown in the mid 16th century.

The priory then fell into decay, stones of the buildings were taken for other construction projects, and the remains of the Priory Church became a parish church.

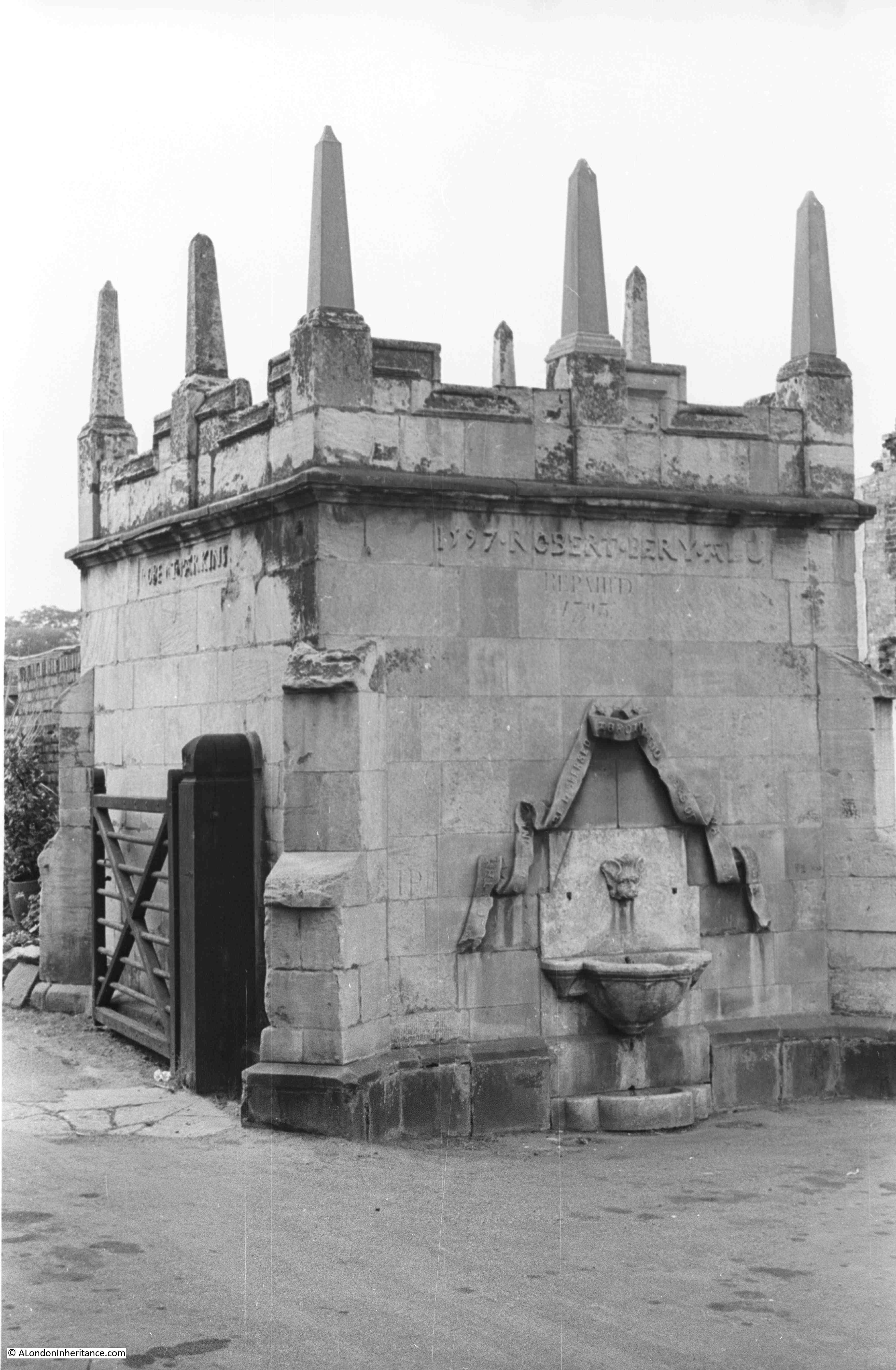

Apart from the church, not much else of the Priory remains. One of the few examples being what is left of the Priory Gatehouse:

The size, detail and quality of carving of what remains of the Priory Church gives an impression of what the overall Priory site must have looked like when Eleanor’s body was rested here overnight in frount of the high altar.

The rear of the Priory Church is bricked up. This is where the church would have continued, and there are carved remains that show how the church was decorated. This figure could well have looked on as Eleanor was in the church:

From Dunstable, there were only two more stops before reaching the City of London, and these stops will be covered in the next post, before an exploration of the London crosses, and Eleanor’s final resting place, in the final post of the series.