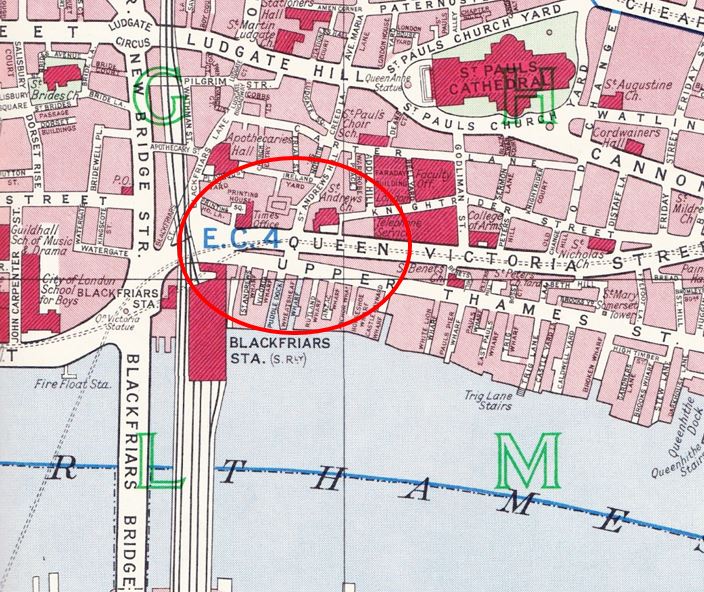

This week’s photo finds us in Gresham Street in 1947 looking towards St. Paul’s Cathedral. With the exception of St. Paul’s and the church spires, all the other buildings have been demolished over the years following the war and only the street names and churches provide a tangible link back to the long pre-war period.

The church in the foreground is St Vedas on Foster Lane, a Wren church built following the Great Fire of London.

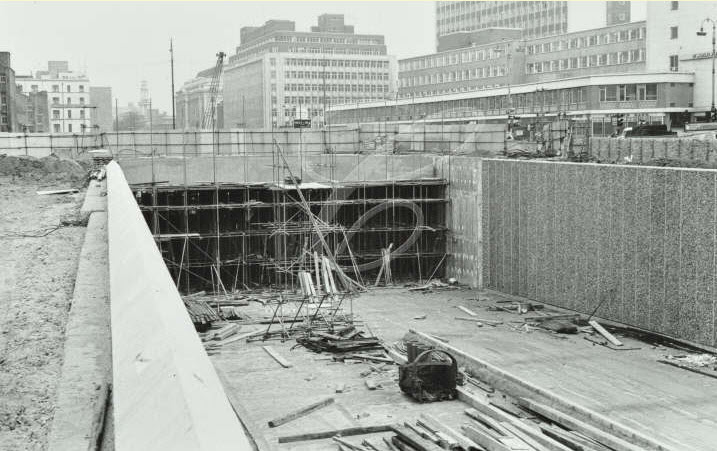

As with many City churches, the core of the church has been destroyed with only the shell remaining, however the tower still stands and fortunately is structurally sound. It was the raid on the 29th December 1940 that caused the majority of the damage in the area around St. Paul’s. As well as high explosive bombs, over 100,000 incendiary bombs created so many fires that the area was devastated. Only the work of many volunteer fire-fighters managed to save St. Paul’s.

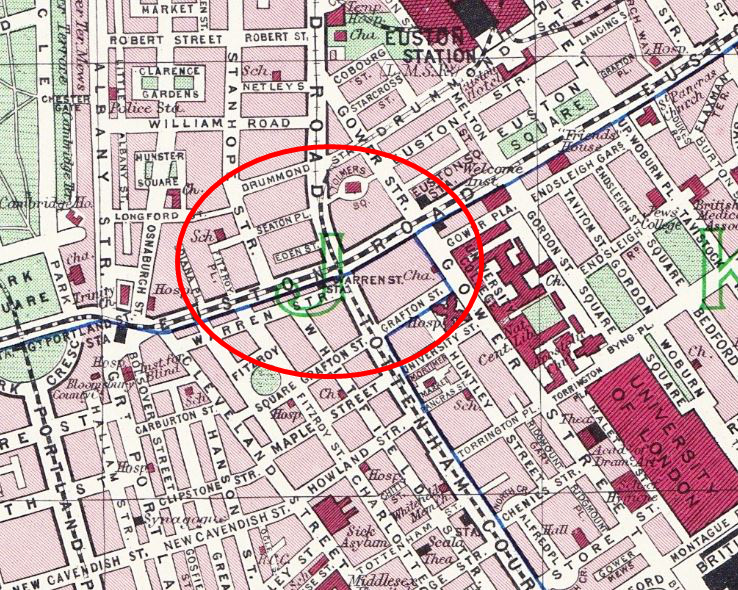

My grandfather had experience of incendiary bombs during one of the many raids that hit the area they were living in just to the west of Euston Station. An incendiary penetrated the flat above and armed with buckets of water and a stirrup pump he managed to put it out before a fire took full hold. If you could get to an incendiary bomb quickly you would have a chance. The problem was the sheer number of them that would fall in a raid with limited numbers of fire-fighters to get to them quickly, or they would lodge in inaccessible places and could not be put out. This, along with the risk of high explosive bombs falling at the same time.

The photo was taken from Gresham Street, looking across Gutter Lane to St Vedas. I spent an hour somewhat optimistically walking around this area trying to get any view of St Vedas from Gresham Street and surroundings for a comparison photo, however with the degree of new building in the area it is impossible. Coming from the Gresham Street area, you do not realise there is a church until you are almost alongside.

The only place I could get a clear photo of St Vedas is from the Cheapside / New Change crossing just across from St. Paul’s where St Vedas still stands proudly in amongst the building of the last 65 years.

A church was established on the site in the twelfth century dedicated to St Vedas who was a French saint, Bishop of Arras and Cambray in the reign of Clovis (who lived from 466 to 511) and apparently performed many miracles on the blind and lame. Following the invasions of the region by tribes in the late Roman period, Vedas helped to restore the Christian Church.

The dedication to St Vedas may have been by the Flemish community in London in the 12th and 13th centuries. It is an unusual dedication for a church in the United Kingdom as there is only one other church that is currently dedicated to St. Vedas which is in Tathwell in Lincolnshire.

Foster Lane was also known in the 13th Century as St Vedas Lane, which was gradually corrupted over time to Foster Lane (the church has also been referred to as St. Foster).

Foster is evolved from Vedast in such steps as Vastes, Fastes, Fastres, Faster, Faister and Fauster. For 100 years or more prior to the Great Fire, the church was known as St. Foster’s and is now also known as St. Vedas alias Foster.

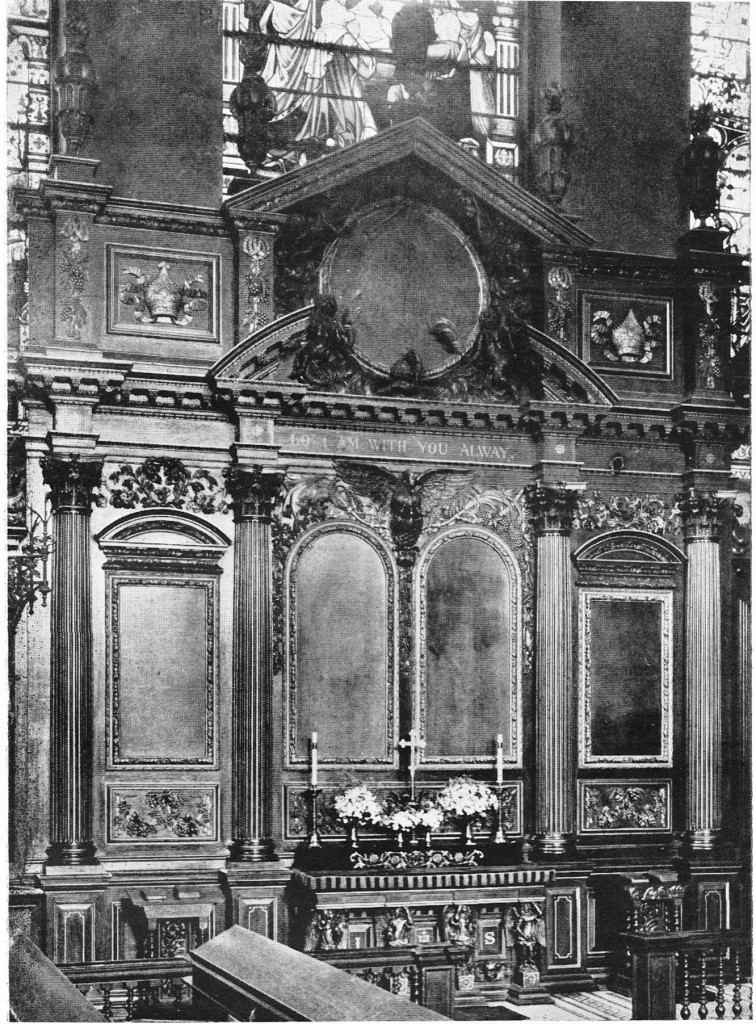

In the 19th century, the interior of St Vedas was described as:

“a melancholy instance of ornamentation. The church is divided by a range of Tuscan columns, and the ceiling is enriched with dusty wreaths of stucco flowers and fruit. The altarpiece consists of four Corinthian columns, carved in oak and garnished with cherubim and palm branches. In the centre above the entablature is a group of well executed winged figures and beneath is a sculptured pelican.”

From 1838 there is a reference that the church did not have stained glass, the windows being covered by transparent blinds painted with various Scriptural subjects.

The following photo from “The Old Churches of London” shows the altarpiece in St. Vedas before destruction in the war, exactly fitting the 19th century description.

Work on reconstruction of St. Vedas commenced in 1953 and it is now a very bright and simple interior. There is still an altarpiece but without the degree of melancholy ornamentation as in the 19th century description. The following photo is as you enter the church and look down to the altar.

And looking back towards the entrance to the church:

And looking back towards the entrance to the church:

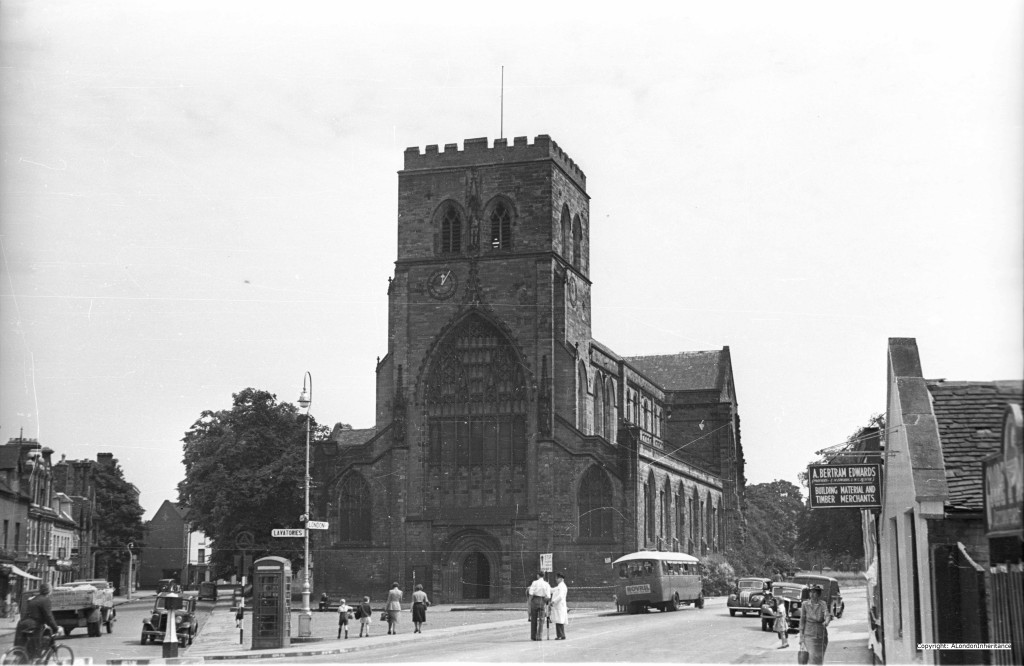

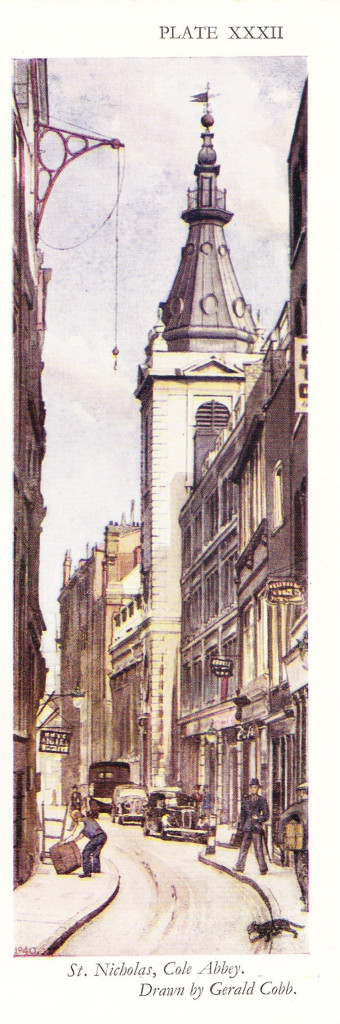

The following picture from “The Old Churches of London” provides an interesting view of the surroundings of St Vedas looking towards St. Mary-le-Bow in Cheapside.

This was still at a time when the spires of the City churches stood well above the surrounding buildings.

The spire of St Vedas is unusual when compared to many other Wren churches in that there are no vases to decorate the spire. The contrasting surfaces and cornices, concave and convex, emphasise the angles and on the light and shade across the spire.

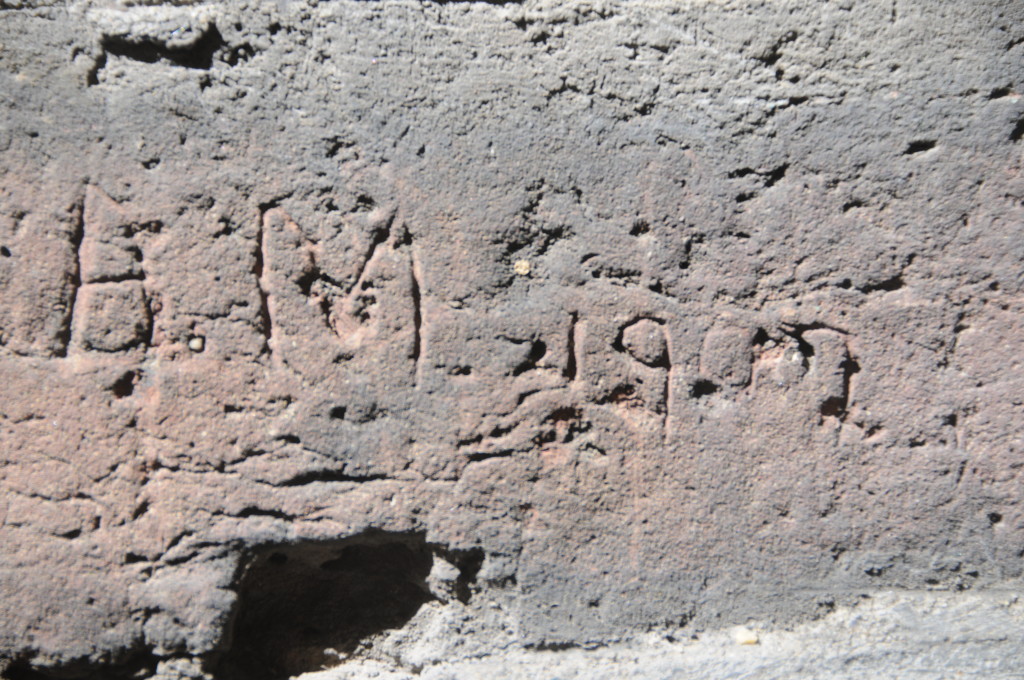

It is always interesting to look at the outside of City buildings and on St Vedas I found two boundary markers just to the side of the main door. Interesting is the use of “alias Foster” as part of the name.

St Vedas is a lovely church to visit and despite being so close to St. Paul’s and the thousands of people who visit this landmark everyday, and being in the heart of the city, it is a quiet and peaceful church. In the all too brief fifteen minutes I spent visiting the church I was not disturbed by a single person.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- The Old Churches Of London by Gerald Cobb published 1942

- London by George H. Cunningham published 1927

- Old & New London by Edward Walford published 1878