The Lansbury Exhibition of Architecture is the final stop on my exploration of the 1951 Festival of Britain.

My apologies, but this is rather a long post, however the story of the Exhibition of Architecture held at the Lansbury Estate in Poplar is a fascinating subject, and as usual, I feel I am only scratching the surface, although I hope you will find this of interest.

For the majority of this post, I will take a walk around the Lansbury Estate, but first some background.

The London Docks, industry and density of population meant that much of the east end of London was a prime target during the last war with large areas in need of urgent reconstruction by the late 1940s.

On the 29th May 1946, the London County Council applied to the Minister of Town and Country Planning for 1,945 acres of Stepney and Poplar to be declared an area of comprehensive development under the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act.

Of the total request, 1,312 acres were declared to be an area of Comprehensive Development which meant that development of the area could now be planned and implemented as an integrated project with zoning of space and allocation to specific functions such as shops, housing, schools etc.

The plans to redevelop the area were based on the 1943 County of London Plan which attempted to address many of the problems caused by the random and sprawling growth of London such as:

- Traffic congestion

- Large areas of depressed housing

- Inadequate and badly distributed open spaces

- Intermingling of industry with housing

The plans acknowledged that despite the way the city had grown, strong, local communities had developed and it was important that these were retained during future development.

Eleven new neighbourhoods were planned for the Stepney and Poplar area of comprehensive development, each would be developed as if it were a small town with the appropriate local facilities of schools, shops, churches and public space.

An Exhibition of Architecture was planned for the Festival of Britain and in 1948 the Council for Architecture, Town Planning and Building Research proposed that one of the neighbourhoods to be developed in Stepney and Poplar would be an ideal site to demonstrate the latest approach to town planning, architecture and building.

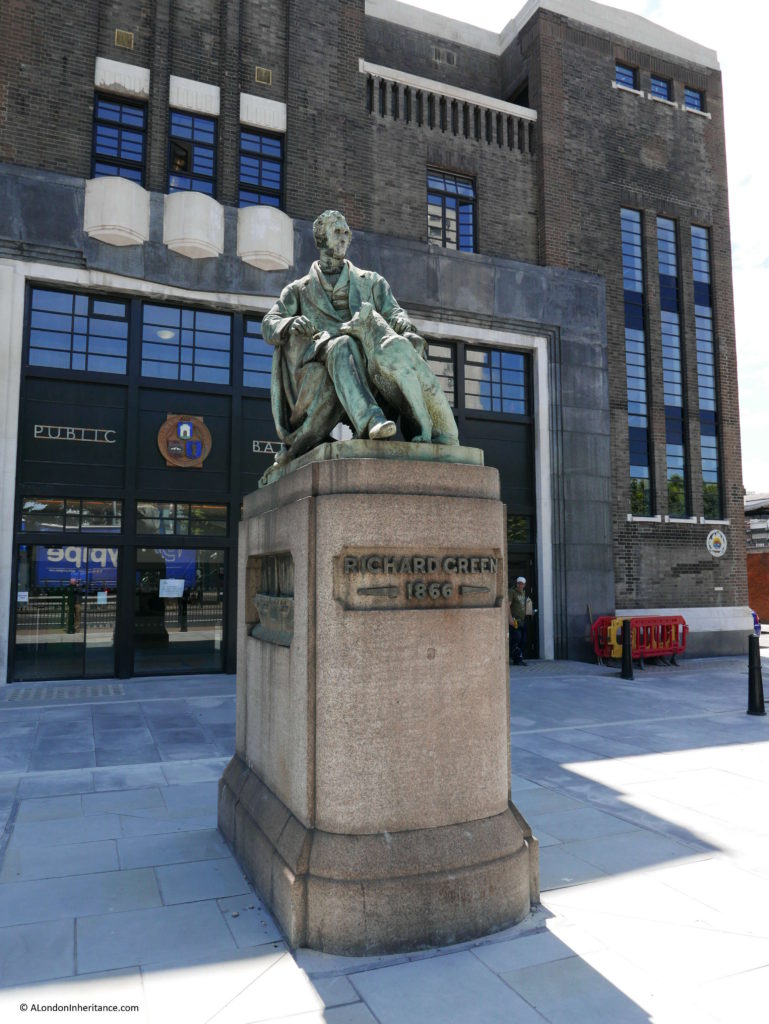

A neighbourhood in Poplar was chosen. Named “Lansbury” after George Lansbury who had a long association with Poplar, as the Poplar member for the Board of Guardians of the Poor, on the Poplar Borough Council, the first Labour Mayor in 1919 and until his death in 1940 he was the Labour MP for one of the Poplar divisions.

The Lansbury Exhibition of Architecture would show how town planning and scientific building principles would provide a better environment in which to live and work, and how this would be applied to the redevelopment of London and the new towns planned across the country.

The following Aerofilms photo from 1951 shows Poplar looking west towards the City. The East India Dock Road runs from middle left of the photo. Along the lower part of the photo, running from left to right is the old railway that ran from Poplar Station (located where All Saints is now), north through Bow and Old Ford stations. The DLR now occupies this route.

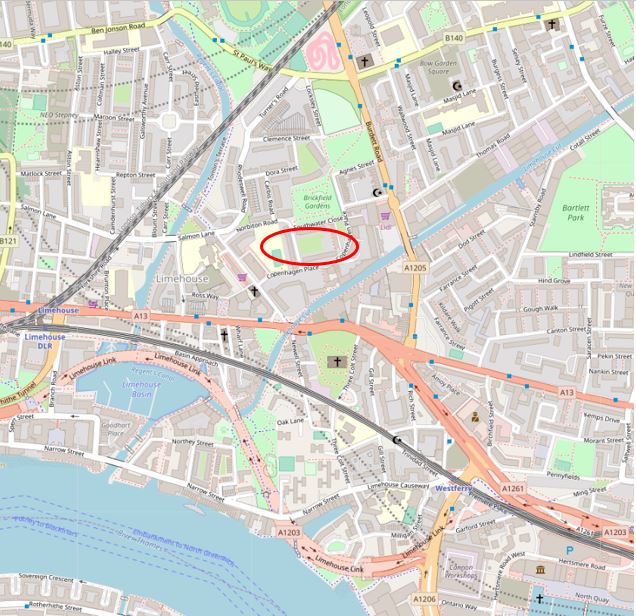

I have outlined in red the borders of the Exhibition of Architecture. Much of the site was still being developed by the time of the Festival of Britain, however the construction of some buildings was brought forward and a special exhibition area was constructed specifically for the festival.

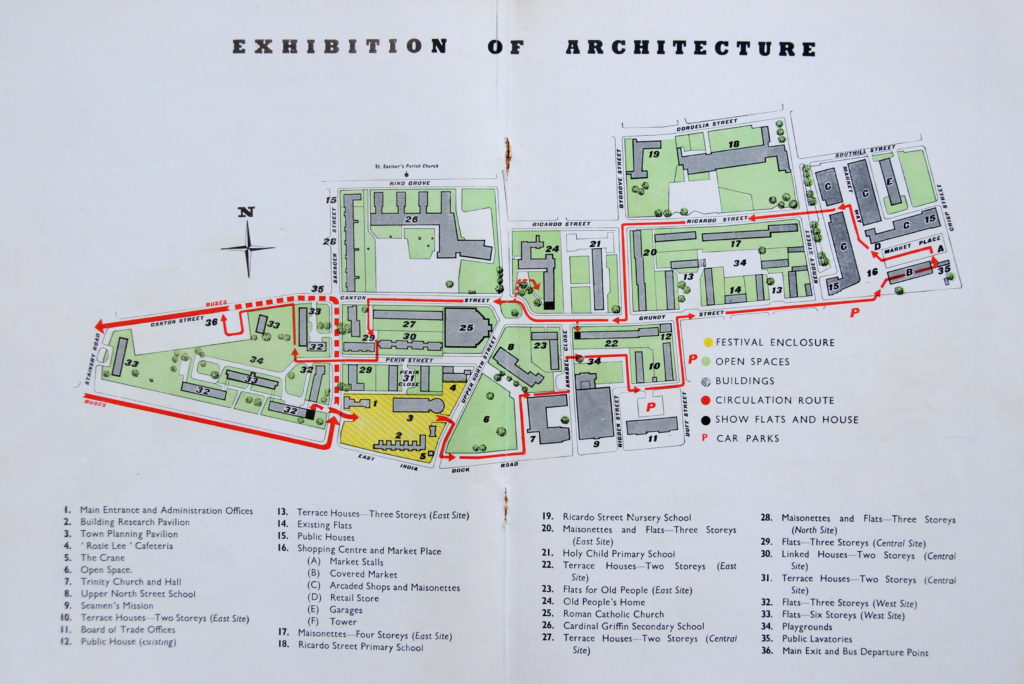

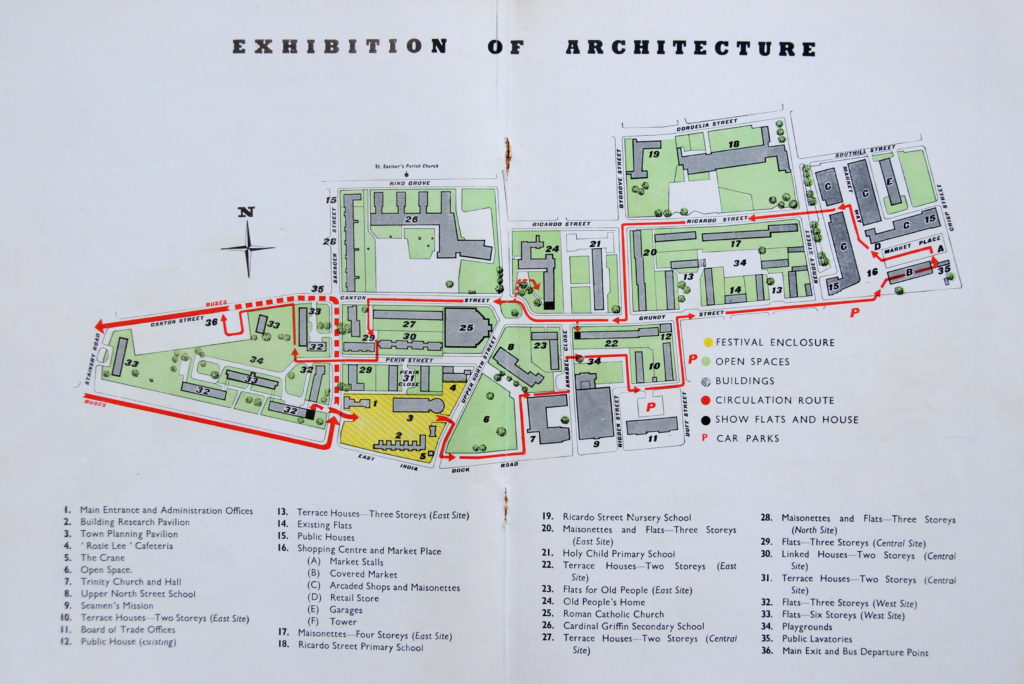

The following map is from the Lansbury Exhibition of Architecture Guide. Turn this by 90 degrees to the right to match the layout of the photo above. The red arrows on the map show the recommended route for the visitor to walk around the exhibition and the map shows the type of buildings either constructed, in the process of construction, or planned for the future in order to show Lansbury as a single, integrated neighbourhood.

The map gives the impression that at the time of the exhibition this was a fully finished site. Completion of many of the buildings had been rushed through ready for the start of the exhibition, however work on many others was still in progress and the exhibition site would not really reach a state of completion until the closure of the exhibition. A criticism at the time was that the route around the site was hard to follow with lack of clear sign posting and white direction lines on the ground not always being clear.

To explore the Exhibition of Architecture, I took my copy of the guide and via the DLR arrived at All Saints station ready to walk the same route as the Festival route in 1951.

My tour of the site started in the road to the left of the yellow block which included features 1 to 5. This was the Exhibition Enclosure, and was the first point on the tour – built specifically for the festival and hosting pavilions that would highlight the approaches now being used for town planning and building.

The Exhibition Enclosure included a Building Research Pavilion, a Town Planning Pavilion, a weather station (to show the relationship between changing weather conditions and building materials), along with one of the new types of crane that would soon be seen across London as reconstruction continued apace.

The Exhibition also included a “Gremlin Grange” in the Building Research Pavilion that highlighted what goes wrong when scientific building principles are not employed, such as:

- Structural cracks and leaning walls – due to bad foundation design

- External plaster coming off – because the mix contained too much cement

- Damp rising up the walls – because there is no damp course

- Leaning chimney stacks – often the result of chemical action on mortar joints

- Fireplaces smoking – owing to bad design of chimney and flue

- Tank leaking – because it lacks protection against frost

- Cracks in walls – because poorly designed foundations have subsided

- Bad artificial lighting – causing discomfort and eyestrain

The intention was to show that through the use of new design principles and building materials, the buildings across Lansbury would not suffer these gremlins.

The following photo is from the corner of Saracen Street and the East India Dock Road looking across to the area that was the Exhibition Enclosure. Buildings in line with the architectural style of the rest of Lansbury were built on the site following the closure of the festival.

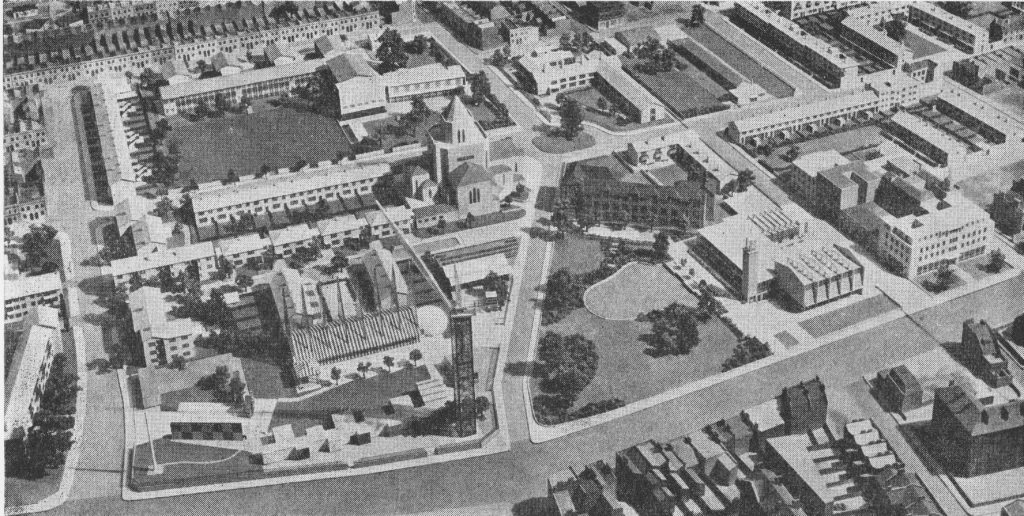

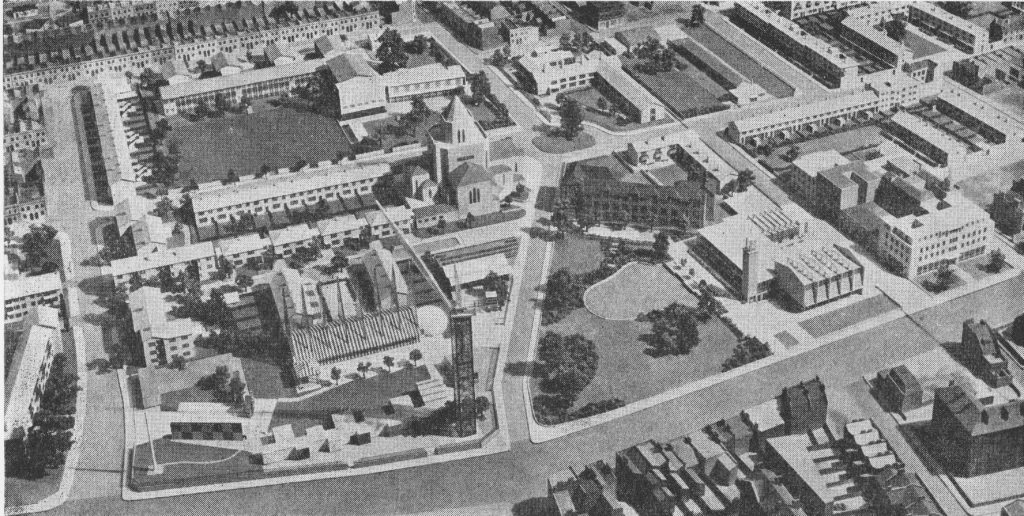

A model of the area shows the Exhibition Enclosure in the lower left of the following photo:

I then walked to the open space marked as point 6 on the map – and centre right in the above photo.

Point 6 is an area of open space in front of the new Trinity Congregational Church. Before the redevelopment of Stepney and Poplar there was a combined total of 42 acres of open space which averaged out at 0.4 acres per 1,000 people. The County of London plan proposed an increase to a standard of 3.6 acres per 1,000 people and across the Stepney and Poplar development area, an increase from 42 to 267 acres of open space was planned. We will see as we walk around the Exhbition of Architecture route how open space has been used across the development of Lansbury.

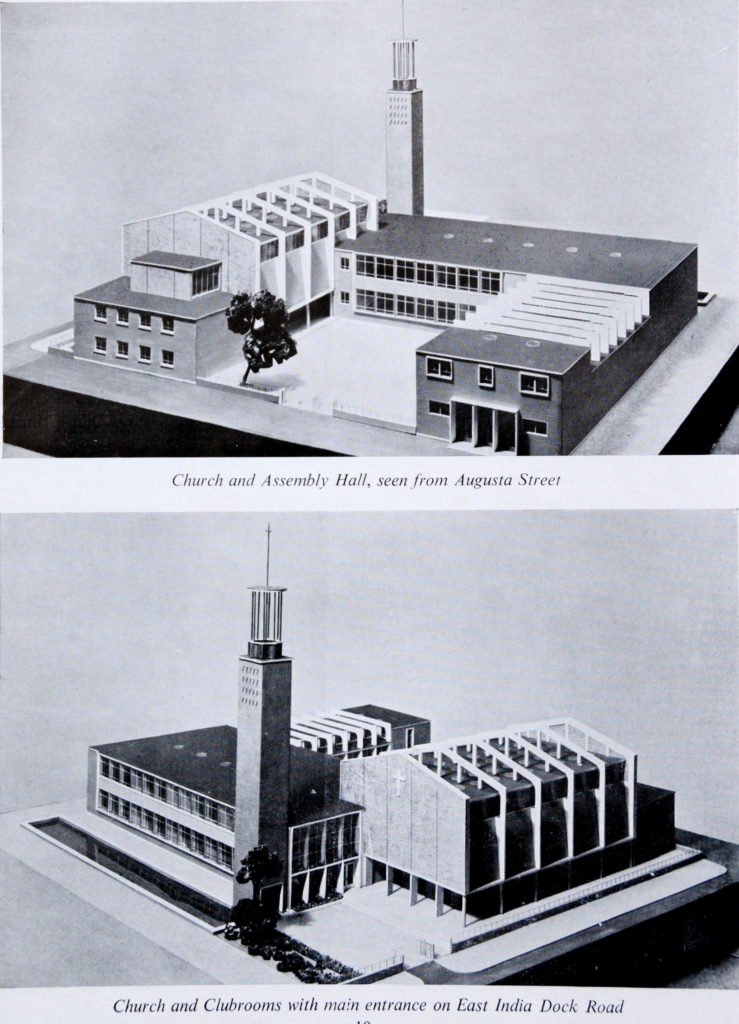

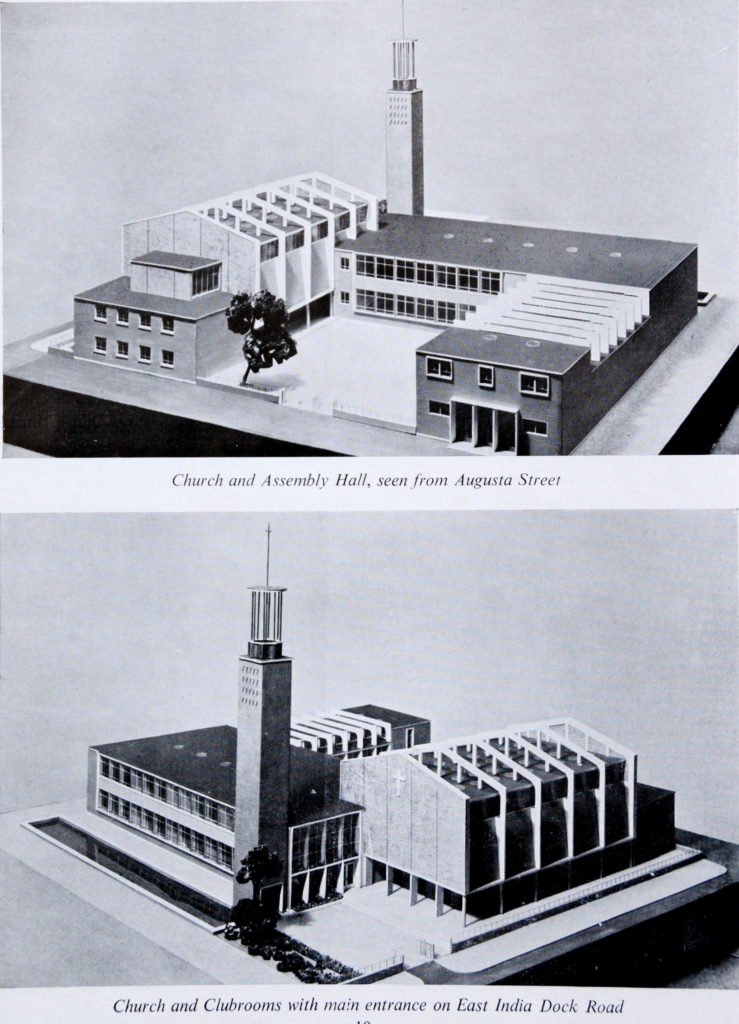

At the far end, we can see the tower of Trinity Congregational Church (point 7 on the map). Built on the site of an earlier church that was destroyed by bombing, the new church was designed by the architects Cecil C. Handisyde and D. Rogers Stark. The main structure of the church is of reinforced concrete with London brick covering the exterior of the tower.

The church today looks almost identical to the original architectural models:

Rear view of the church from Annabel Close – the only change to the model of the church is from a double to a single row of windows on the building at the rear.

The church was originally a Methodist Church, but is now a Calvary Charismatic Baptist Church.

The photo below shows the side view of the church buildings, again almost identical to the original model. The brick facing and large areas of glass are typical of post war designs used for public buildings.

Back to the recommended route for the Lansbury Exhibition of Architecture and after walking round the church, we can cross Annabel Close and walk into the playground marked 34 on the map.

The playground as it is today:

Playgrounds were an important part of the open space policy and at the time of the Exhibition of Architecture were planned to include children’s playground rides and sandpits.

In the centre of the old playground are two highly reflective memorials to the Festival of Britain and George Lansbury. The memorial to George Lansbury is shown below and provides an overview of his work in politics, the pacifist movement, efforts to improve the lives of the poor, equal rights and votes for women, along with his long marriage to his wife Elisabeth and their 12 children (one of his grandchildren is the actress Angela Lansbury).

Walking out of the old playground area, past the parking area for cars and into Duff Street and it is here that we first encounter the new homes built as part of the redevelopment of the area.

The following photo is looking up Duff Street towards Grundy Street with the two storey, terrace houses marked at point 10 on the map.

Although almost the whole area of Lansbury is post-war new build, there are some buildings that remain from the pre-war period. On the map is a building at the end of Duff Street marked as number 12 – Public House (existing). The side of the pub can be seen in the above photo and the full view from Grundy Street is shown in the photo below:

The pub was built in 1868 as the African Tavern, but changed name to the African Queen in the 1990s. The faded name board for African Queen can still be seen on the edge of the pub from Duff Street. The pub closed in 2002.

Standing in Grundy Street we can see at each end two of the main features of Lansbury, to the west the Roman Catholic Church:

And to the east, the tower at Chrisp Street Market:

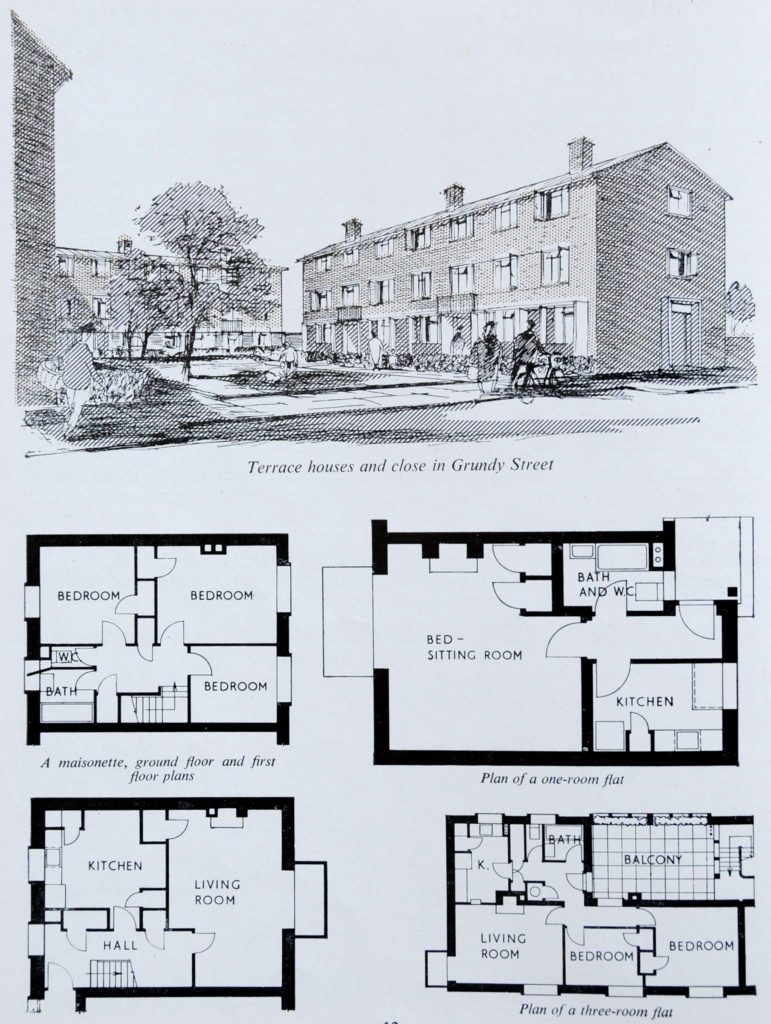

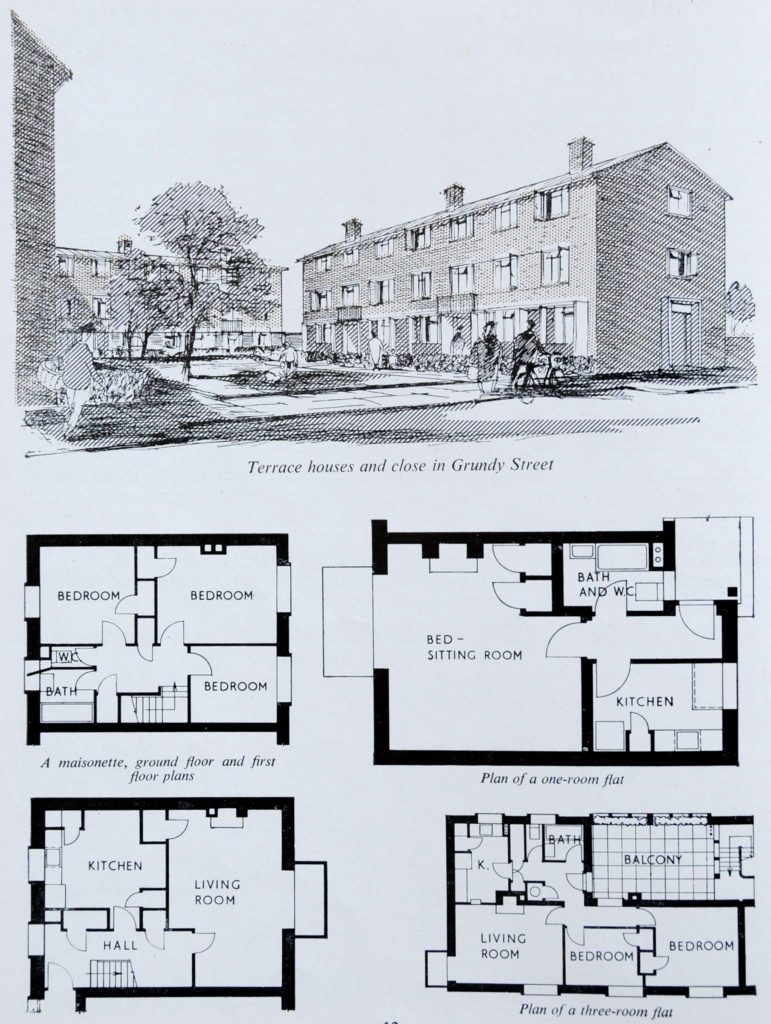

Continuing along the route from the exhibition along Grundy Street and these are the three storey terrace houses marked at point 13 opposite Duff Street. Again, the use of a large area of open space that opens out to the street, with the houses constructed on three sides results in a very different environment when compared with the high density housing that originally occupied the area.

Walking along Grundy Street and here is the second set of three storey, terrace houses, also marked as point 13 on the map. This is Chilcot Close.

The drawings for Chilcot Close were featured in the guide to the Exhibition of Architecture and show the buildings and central open space to be almost the same today. The drawings also show the floor plans of the mix of different types of accommodation in these terrace houses with a maisonette, one room and three room flats.

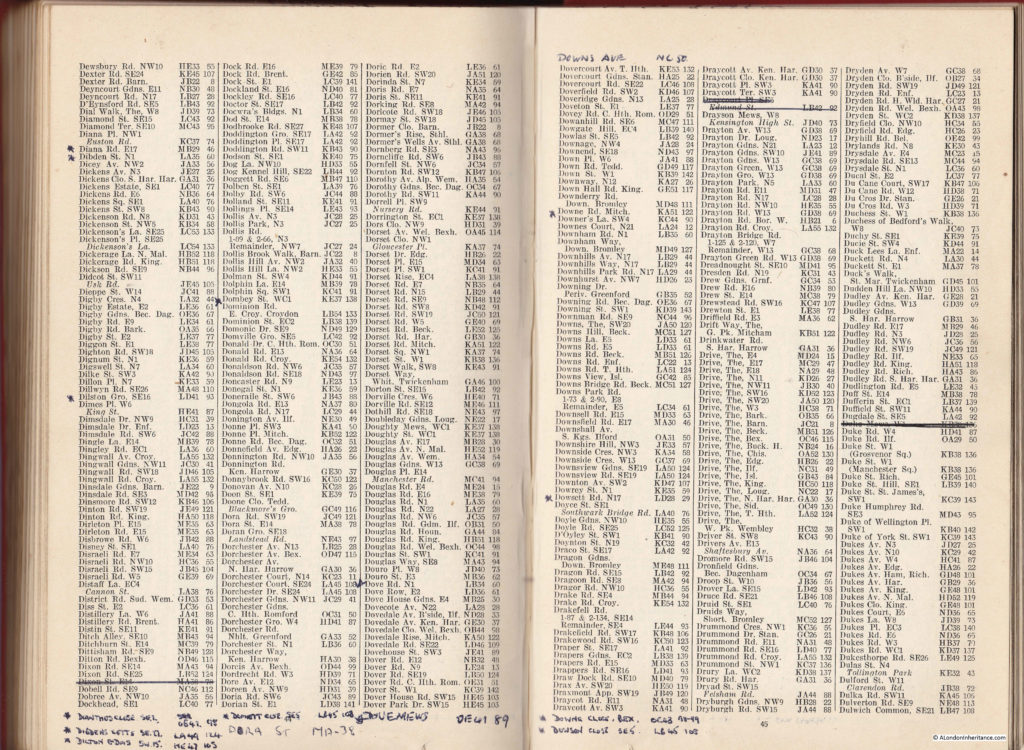

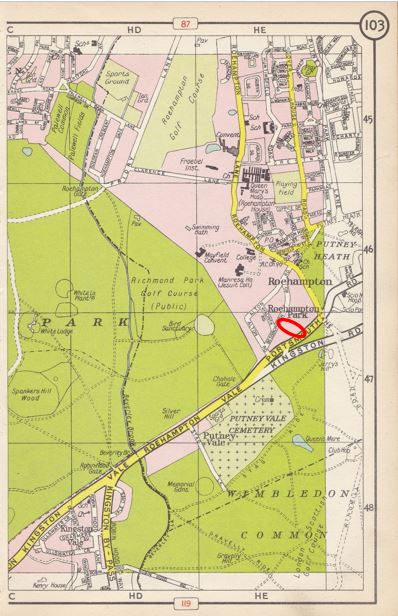

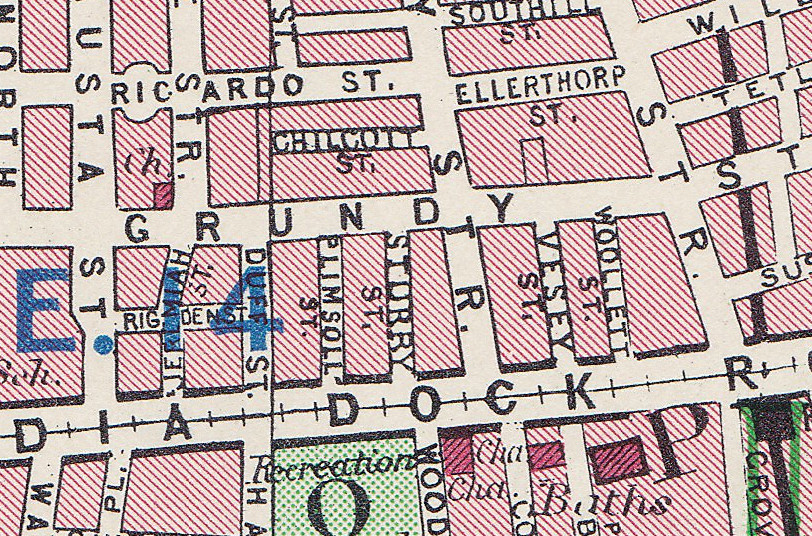

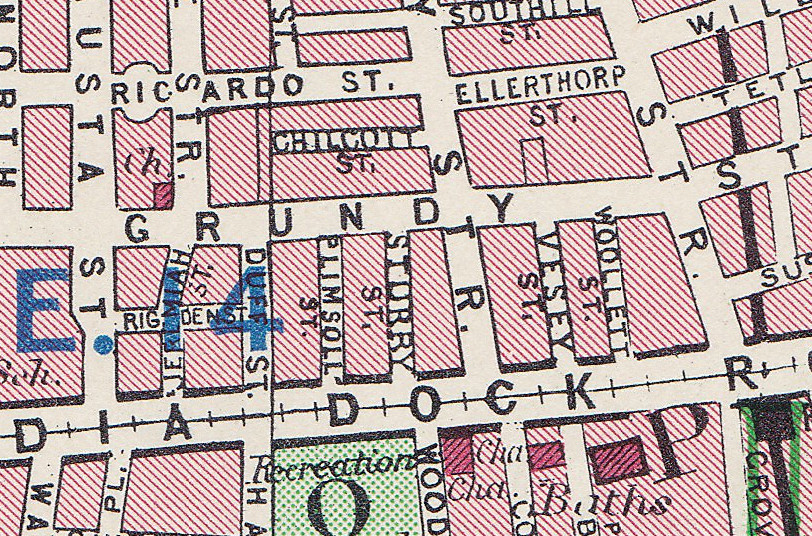

Chilcot Close is an interesting example of where building names have retained the names of lost streets. The map extract below is from the 1940 Bartholomew Greater London Atlas and shows Grundy Street running along the centre of the map. Just above the letter N in Grundy is Chilcott Street. The street was lost in the post war rebuilding with the two sets of three storey houses now occupying this space, however the name of the street (less a T) has been kept as Chilcot Close. The fact that a street extended into this block of land shows the original density of building as houses would have run along Grundy Street and also all round Chilcott Street.

Continuing to the end of Grundy Street, we come to the junction with Kerbey Street and it is here, at point 15 on the map that we find the Festival Inn. Thankfully still a working pub, as well as the name, the pub retains a link with the Festival of Britain by the use of the festival’s symbol by Abram Games on one side of the pub sign.

The Festival Inn is on the edge of the Shopping Centre and Chrisp Street Market (point 16 on the map) which was core to developing the Lansbury community and to replace the original Chrisp Street market.

The Festival Inn replaced two nearby pubs, the Grundy Arms and the Enterprise. Although the pub sign still uses the festival symbol, there was originally a free standing pub sign consisting of a pole with at the top the model of a group of Londoners dancing around the Skylon – the Festival and London equivalent of a maypole. Unfortunately this has not survived.

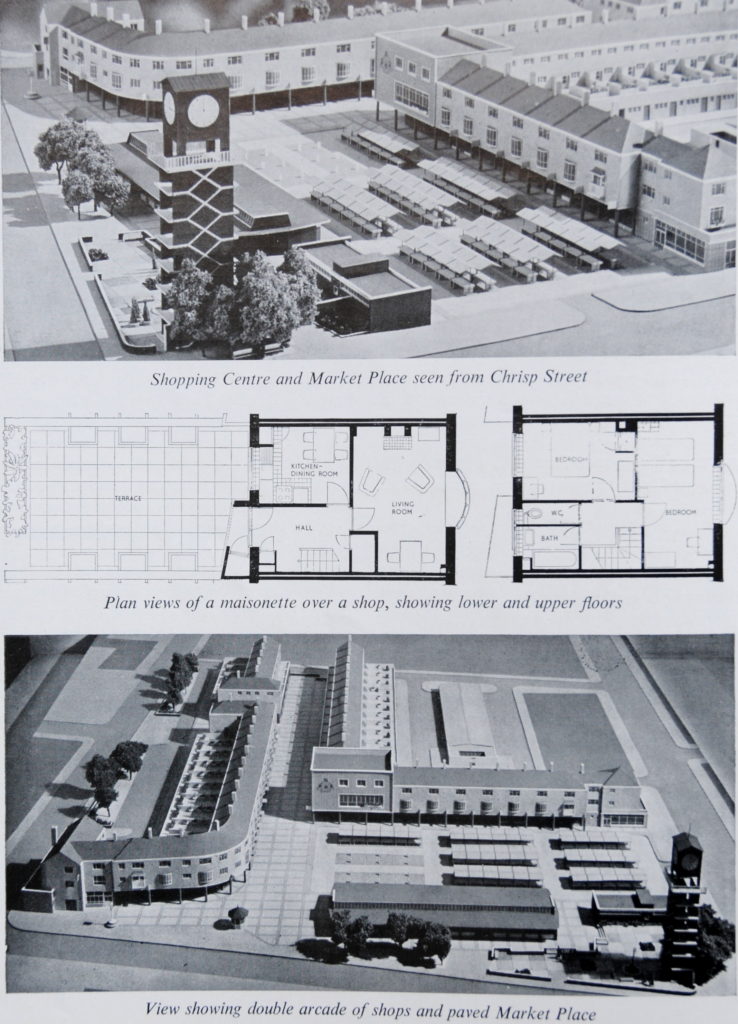

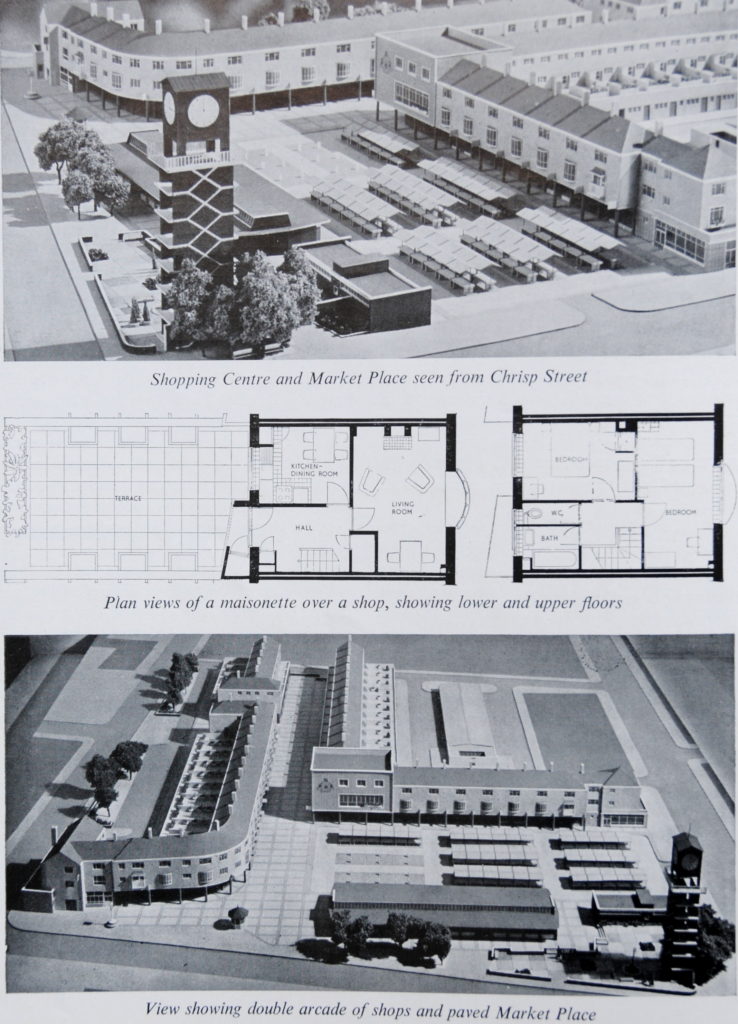

Photos of the model of the shopping and market area are shown below. The area consisted of:

- a large pedestrian area with space for the stalls of street traders along with permanent covered stalls allocated to traders in meat and fish

- terraces of lock up shops running alongside the market and along a branch heading up to Cordelia Street

- above the lock up shops were maisonettes, mainly two bedroom, but some three bedroom

The buildings lining the market are of London brick with reinforced concrete beams running along the top of the shops to support the maisonettes above.

At the edge of the market is a clock tower with steps running up the inside of the tower to a viewing gallery at the top. As well as photos of the model, the floor plans of the maisonettes can be seen below.

View from within the market showing the pub at the left and the shops with the maisonettes above. This is the part of the market in the lower left corner of the photo above.

The photo below shows the branch of the shopping centre / market looking down towards Cordelia Street. Again, still almost identical to the original model shown in the photos above.

This layout, with pedestrianised walkways between rows of shops with accommodation above would be the format for new town shopping centres and town centre redevelopment for decades to come.

View looking to the north east corner of the market / shopping centre.

The Chrisp Street Market replaced an earlier street market. Pre-war, Chrisp Street Market was the largest across Poplar and Stepney with 285 licensed stalls on the busiest day, the next largest was Middlesex Street Market with 262 licensed stalls. These were figures from 1939.

There were many other street markets across Poplar and Stepney and the following table shows the markets with pre and post war stall numbers. Interesting that for the majority of street markets they were smaller in 1951 than they had been in 1939 – reflecting the loss of housing and therefore population.

| Stepney |

1939 |

1951 |

| Solebay Street |

26 |

8 |

| Burdett Road |

60 |

36 |

| Hessel Street |

29 |

29 |

| Burslem Street |

16 |

9 |

| Watney Street |

200 |

150 |

| White Horse Road |

150 |

42 |

| Salmon Lane |

18 |

9 |

| Wentworth Street |

68 |

68 |

| Goulston Street |

100 |

148 |

| Old Castle Street |

40 |

60 |

| Middlesex Street |

262 |

262 |

| New Goulston Street |

30 |

42 |

| Poplar |

|

|

| Chrisp Street |

285 |

189 |

| Devons road |

39 |

12 |

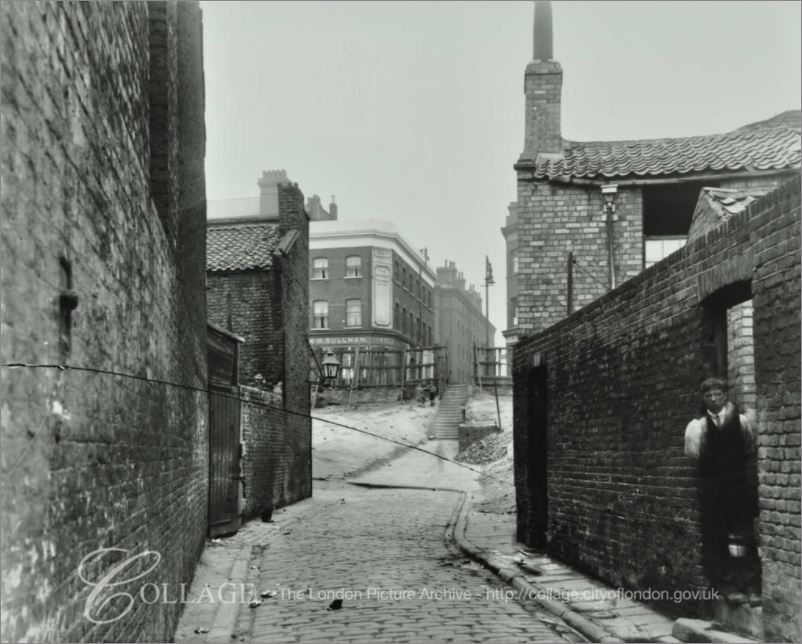

The following photo shows part of the original Chrisp Street market:

At the corner of the market, alongside Chrisp Street is the clock tower built as a key feature of the market. Running up the centre of the tower are two interlocking staircases built of reinforced concrete leading up to the viewing gallery and clock mechanism. The two staircases only met at the top and bottom of the tower so that those walking up would use one staircase and those walking down would use the second – a clever design to avoid congestion on the stairs.

At the opposite corner of the market place to the clock tower, along Chrisp Street, is one of the new pubs, shown as point 15 on the map, built as part of the redevelopment.

To continue the recommended route from the exhibition, walk back through the market and along Market Place and cut through to Ricardo Street.

Ricardo Street is lined along the south side with four storey maisonettes (point number 17 on the map). A mix of two to four bedroom maisonettes each with a living room, garden and clothes drying area with two storeys per maisonette. The upper level is reached along the balcony on the third floor that runs the length of the terrace.

At the end of Ricardo Street, turn south into Bygrove Street and these three storey blocks line the street which comprise two storey maisonettes with a flat above on the top floor (number 20 on the map).

The construction of these four and three storey buildings was to the same standard and consisted of foundations of mass concrete with piling where required, external walls of load bearing brick with London brick on the exterior facing. Fire resistant construction between individual flats and maisonettes along with sound insulation – all aimed at improving the safety and living standards of those who would be living in Lansbury.

Roofing was in Welsh Slate and windows were metal in wooden frames.

At the end of Bygrove Street we are back into Grundy Street and in position 22 on the map there is a row of 2 storey terrace houses.

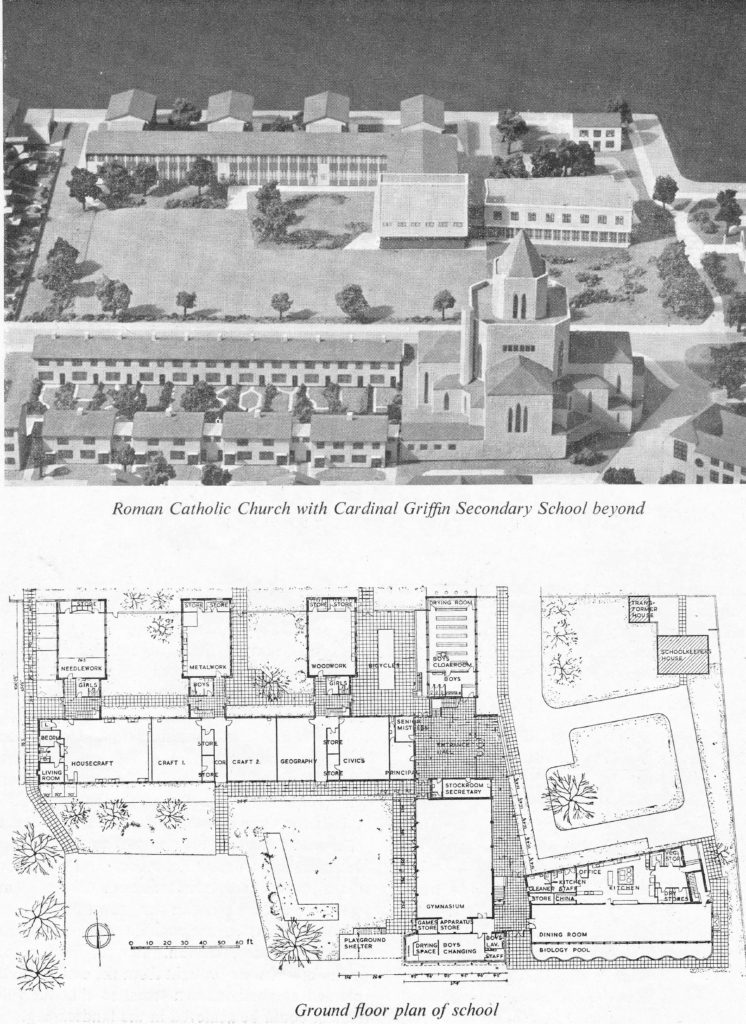

At the end of Grundy Street is the large Roman Catholic Church that was under construction at the time of the Festival of Britain. Replacing an earlier church, the new church had seating for 700 people as at the time, Poplar had a large Roman Catholic population and in the years immediately after the opening of the church, attendance would often reach 1,000 people.

The architect of the church was A. Gilbert Scott. The overall shape of the church was based on a Greek cross, and exterior of the building was faced with stone coloured bricks with the roof being covered in Lombardic styles tiles – a very different style to the rest of Lansbury and to the Trinity Church, which along with the central position of the church within the Lansbury estate made the church a key landmark within and from the outside of the estate.

Now walk past the church and into Canton Street and in position 27 on the map are more two storey terrace houses. The opposite side of the road has buildings of recent construction which I will return to later.

Follow the map and cut through into Pekin Street and there are more two storey houses, but of a different design. Point 30 on the map and described as “linked houses”. Not exactly terrace, rather semi-detached houses linked together by a smaller, two storey build.

Now at the junction of Pekin Street and Saracen Street we can look across to the three storey flats marked as 32 on the map.

Following the map and walking past these flats, a large, green space with mature trees (almost certainly planted at the time of construction) opens out. As can be seen from the photos, there is a good amount of open space, trees, hedges and grass across the Lansbury estate, with the level of green on the exhibition map showing the planners intention that there should be plenty of open space, gardens and grass across the estate.

Having reached the open space we can see the tallest buildings constructed as part of the original development, the six storey flats shown at point 33 in the map.

The architect for these flats was Sidney Howard of the Housing and Valuation Department of the London County Council.

The six storey flats have lifts and each flat was equipped with a solid smokeless fuel fire and back boiler in the living room or bed-sitting room. This combination provided hot water to the bathroom, hand-basin and the kitchen sink. The flats had a hot water tank in the linen cupboard providing an immediate supply of hot water. Electric power points were installed in each room.

The recommended walk then passes through to Canton Street with the main exit and the bus departure point which was located at point 36. This has since been built over with later flats with a slightly different style but following the overall format of the estate.

Rather than walk back to the Exhibition Pavilion as suggested by the recommended route, I decided to take a walk along some of the other streets in the Lansbury estate which were not on the exhibition’s recommended route.

This is the northern section of Saracen Street and shows the three storey buildings marked 28 on the map. These builds provided maisonettes and flats.

At the end of Saracen Street is the junction with Hind Grove. This is the view looking back down Saracen Street and shows the proximity of this area of Poplar with the towers of the Canary Wharf development.

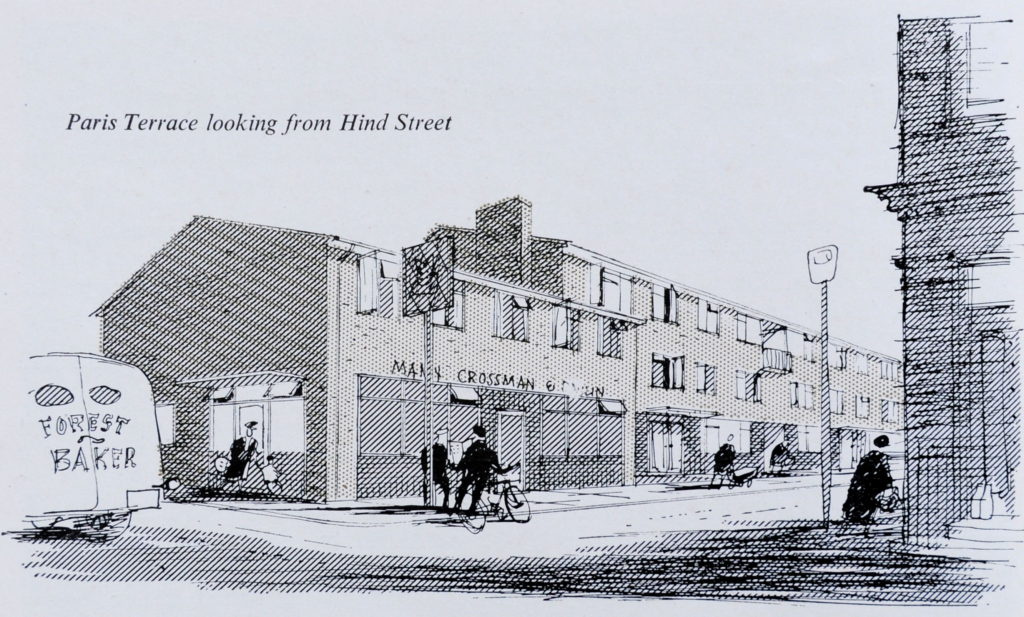

The building on the corner is now the Hind Grove Food and Wine store but was originally a pub marked as number 15 on the map at the junction of Hind Grove and Saracen Street.

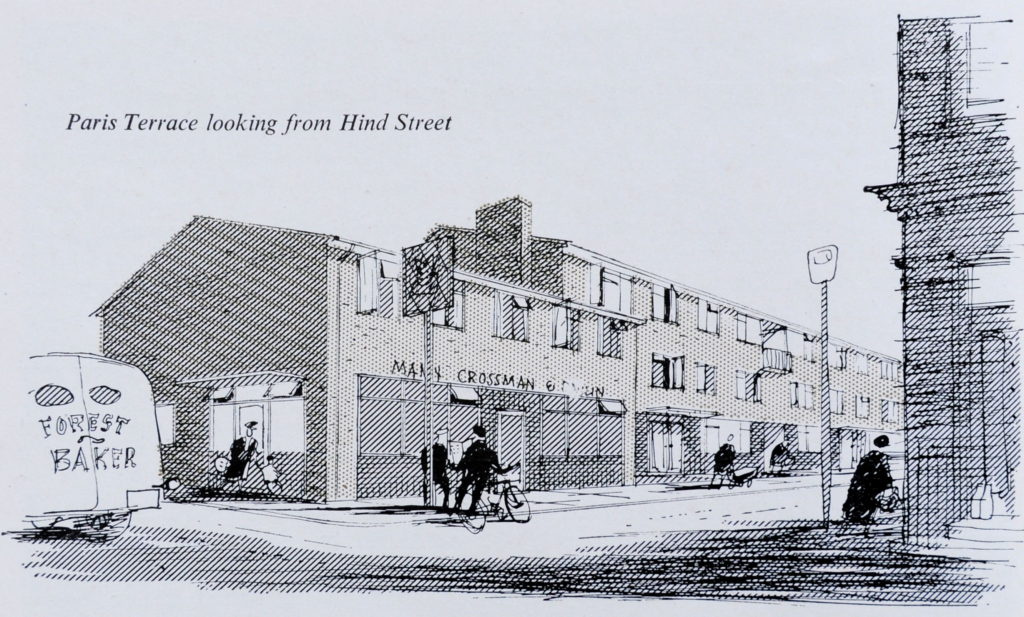

This is the drawing of the pub from the exhibition guide (the caption references Hind Street, however in the 1940 Bartholomew map and on today’s maps the street is called Hind Grove).

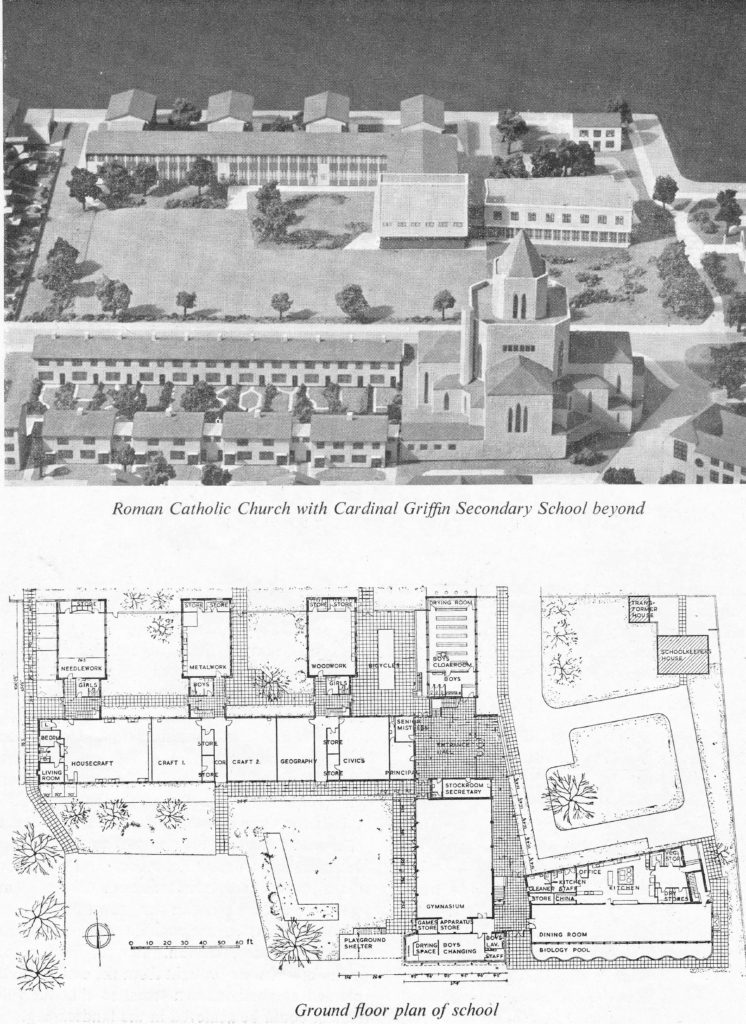

Follow Hind Grove along and this is now the view. In the exhibition map, the buildings marked at number 26 were on this site. This was originally the Cardinal Griffen Secondary School. a large school built as part of the overall development of the Lansbury estate.

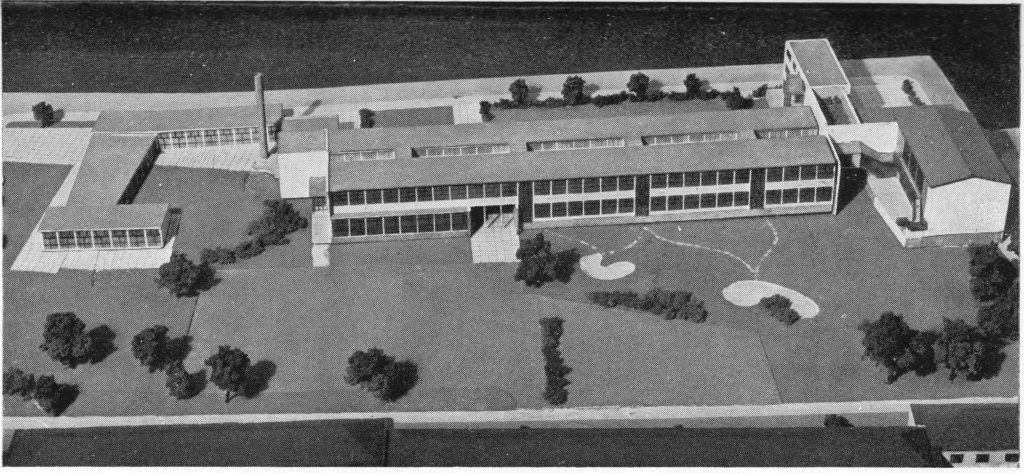

The Cardinal Griffen Secondary School was designed for the Archdiocese of Westminster and the London County Council by David Stokes, to accommodate 450 children aged between eleven and fifteen.

The school consisted of a gym, assembly hall, dining room, staff room, medical room, general class rooms and specialised classrooms for crafts and sciences. The school was constructed of a reinforced concrete frame and brick walls with large areas of glass to provide lots of natural light to the classrooms. Load bearing walls were kept to the outside of the structure thereby giving the freedom for future reconfiguration of the internal space of the school without the need for major building works.

The following extract from the exhibition guide shows the school with the playing fields running along the edge of Canton Street.

The school was renamed as the Blessed John Roche Catholic School in 1991 and closed in 2005 with new housing built on the site of the school and across the playing fields. This included the new building facing onto Canton Street mentioned earlier.

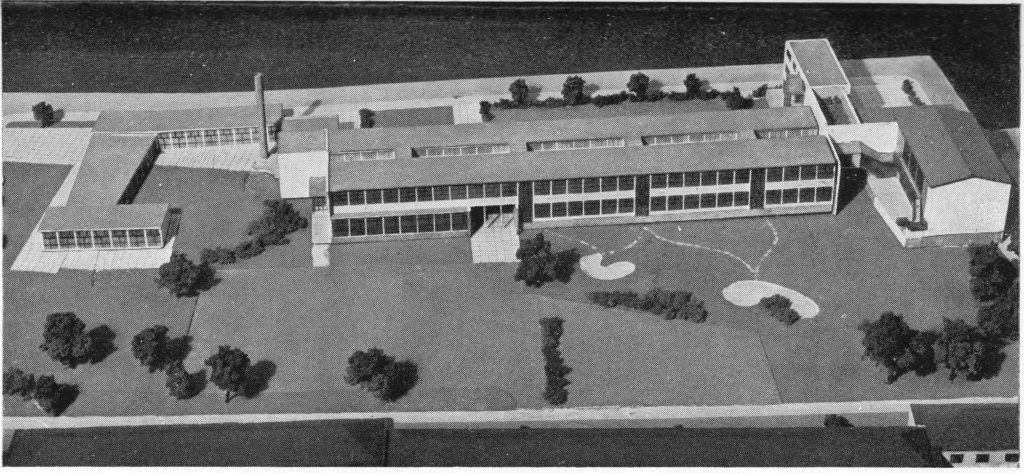

One school that is still here is the original Ricardo Street Primary School – now named the Lansbury Lawrence Primary School. Named after George Lansbury and Susan Lawrence, a Labour MP and member of the local council in Poplar at the time when George Lansbury was challenging central government by refusing to set a rate due to the unfairness of charging the poor.

The entrance to the Lansbury Lawrence Primary School on Cordelia Street is shown in the photo below. Designed by the architects Yorke, Rosenberg and Mardell, construction of the school consisted of a steel framework faced with concrete slabs along with London bricks. Large areas of glass provided plenty of natural lighting to the school as can be seen in the photo.

The original model of the school is shown in the following photo and shows the long row of classrooms with large windows providing plenty of natural light. The entrance to the school shown in my photo above is in the top right corner of the model.

That was the end of my walk around the Lansbury Exhibition of Architecture site, but what was the outcome of the exhibition?

When the Lansbury Exhibition of Architecture was being planned, expected visitor numbers were in the order of 10,000 to 25,000 a day, however by the time the exhibition closed the average daily attendance at the exhibition pavilions was 580. This low attendance should really have been anticipated:

- there was very limited advertising for the exhibition and it had a low key opening

- travel out to Lansbury was not that easy with a boat journey followed by buses being provided by the exhibition organisors

- it was a specialist exhibition, probably only of interest to those in the architectural and building professions and the limited numbers within the population with an interest in architecture and the future of towns and cities

- the Exhibition of Architecture in Poplar, could not compete with the excitement of the rather more central locations of the main festival site on the South Bank and the Pleasure Gardens at Battersea

The impact of the Lansbury development was also unpopular with many of the existing residents. A large number of people needed to be moved to allow for rebuilding to take place. By November 1950, 533 people had been relocated, however the London County Council policy was that people would be relocated to the next available accommodation. This meant that the original population of the Lansbury site could be scattered across London. This was made worse when the new Lansbury buildings were ready for occupation as priority was not given to original residents, rather Lansbury became part of the overall LCC pool of housing with residents being matched to accommodation based on availability and need.

The general view of the architecture at Lansbury was that it was “worthy but dull”. Whilst the estate consisted of buildings ranging from two storey houses up to six storey flats, the overall design was much the same and the use of the same coloured brick for the external finish to the majority of the buildings resulted in a lack of architectural diversity across Lansbury – this can still be seen walking the estate today, as shown in my photos.

Following closure of the Exhibition of Architecture, Lansbury became just another of the many London County Council development sites, with construction of the wider site continuing for the following decades, filling in the area between the Market and the East India Dock Road, building north to the Limehouse Cut and west to Burdett Road.

The area was also hit badly during the 1970s and 80s by the closure of the London Docks. Unemployment and a growing backlog of maintenance work across the estate contributed to an environment where drug dealing and crime took hold across the estate. The Poplar Housing and Regeneration Community Association (Poplar harca) was established in the mid 1990’s and a considerable amount of work has taken place since to repair and refurbish the existing housing stock, build new housing, address unemployment issues etc.

Many of the principles on show at Lansbury, such as the use of mainly low-rise housing and green space was used in the new towns that were being built across the country and walking through the market / shopping centre at Chrisp Street will show similarities with shopping centres at new towns such as Harlow.

As with the majority of London, time does not stand still for Lansbury and today the Chrisp Street market area is threatened with a range of new developments.

A much shorter post in the next couple of days will include some final information about Lansbury.

alondoninheritance.com