There are a few locations in London where it is possible to feel very close to the earliest days of the City, one of these is the subject of today’s post, the church of All Hallows by the Tower.

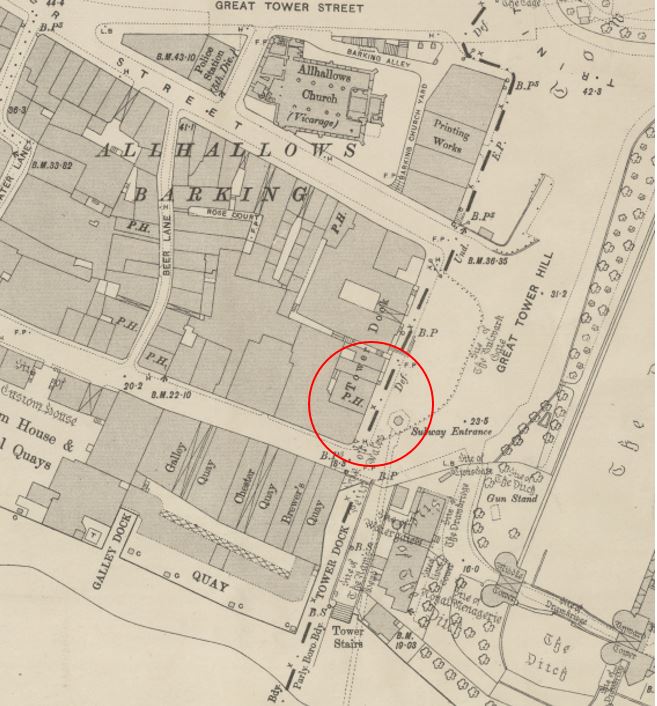

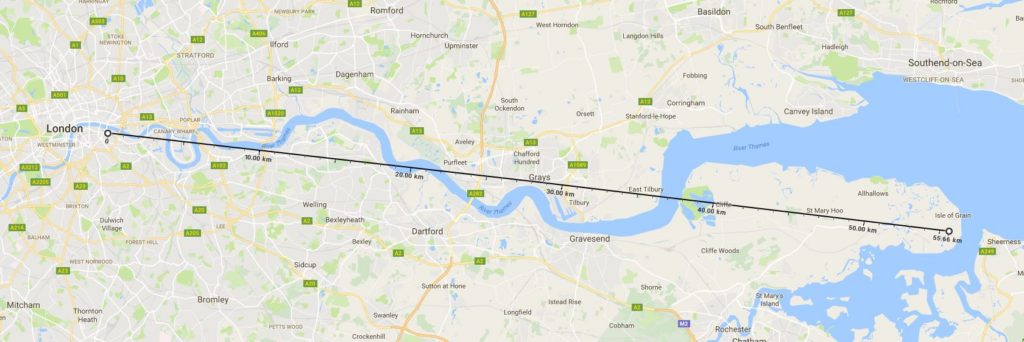

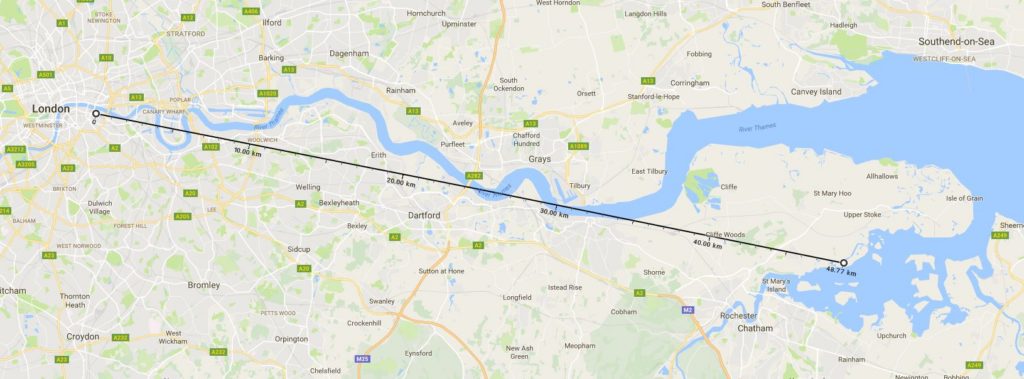

All Hallows by the Tower, or All Hallows Barking as it was known due to the original association with the Abbey of Barking in Essex who owned the land on which the first church was built-in the late 7th century, is to be found at the top of Tower Hill alongside Byward Street.

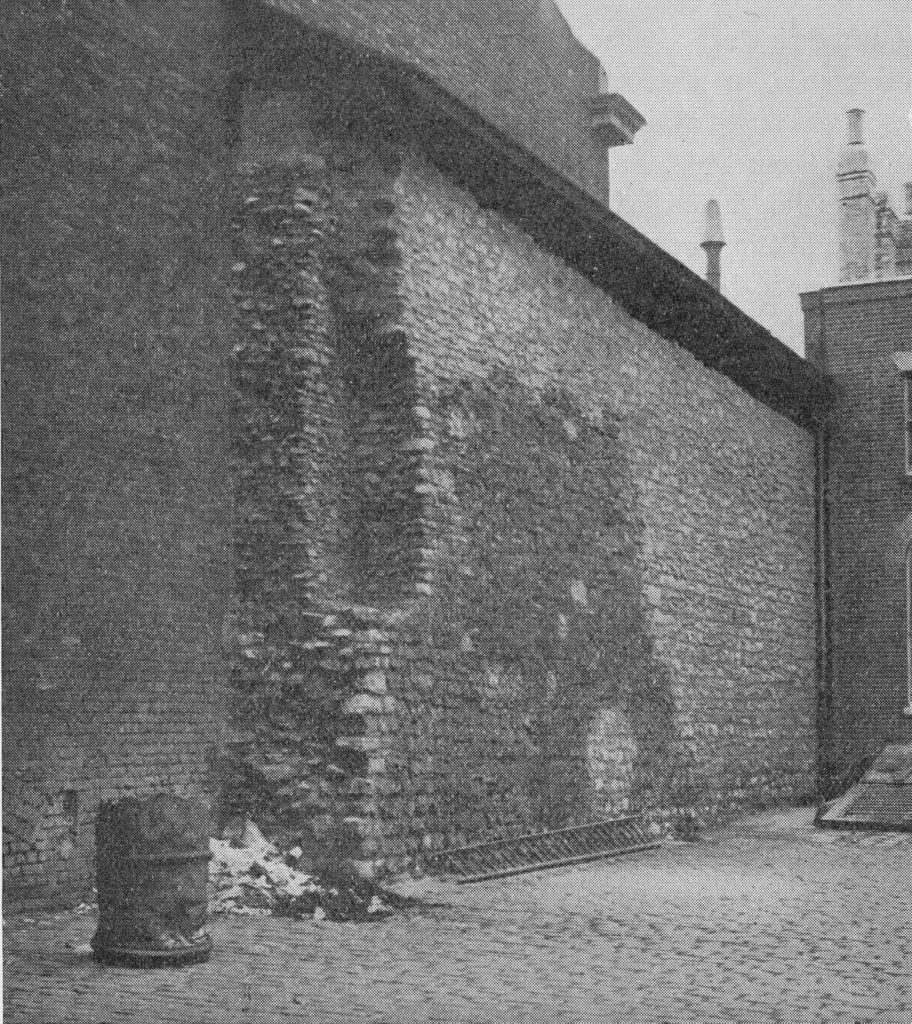

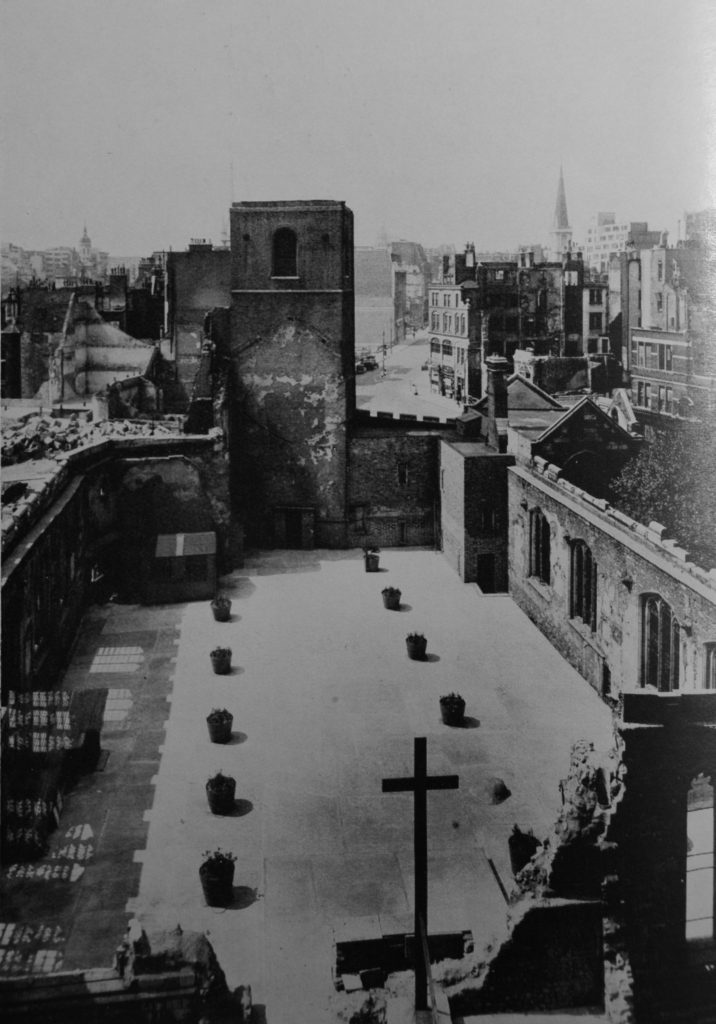

The area between Byward Street and the River Thames suffered very badly in the last war and All Hallows by the Tower suffered a direct hit, along with the impact of nearby explosive and incendiary bombs. By the end of the war, the church was an empty shell.

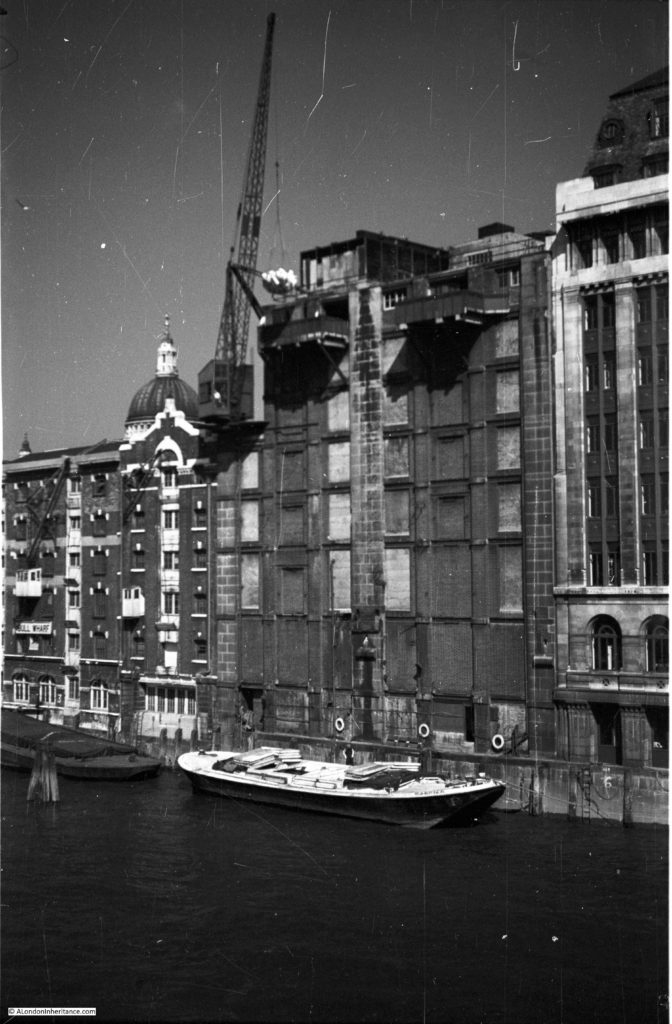

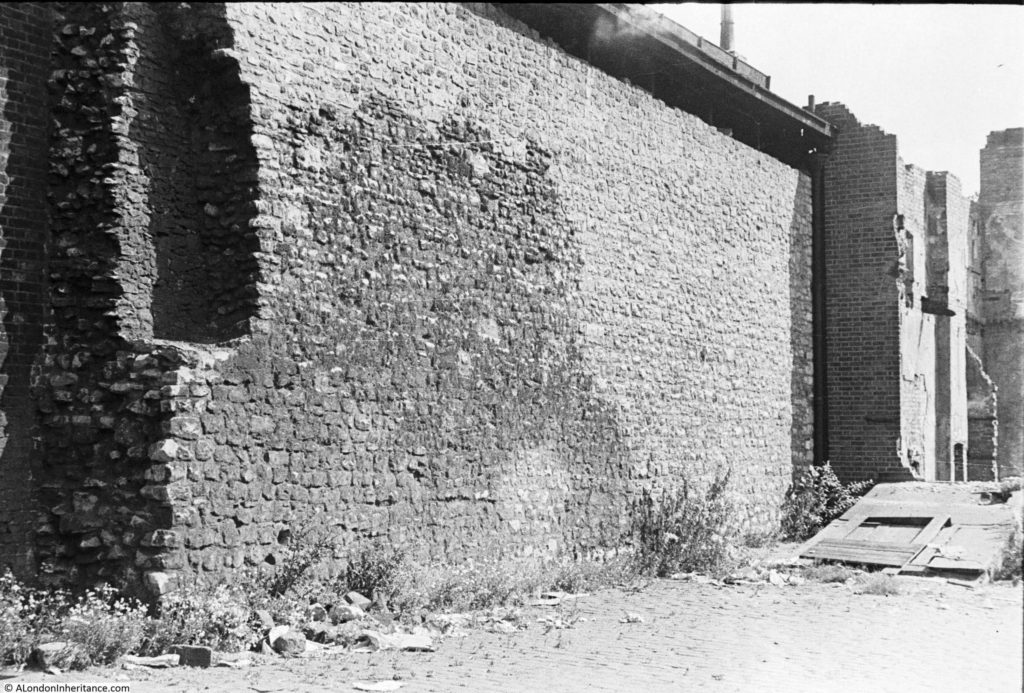

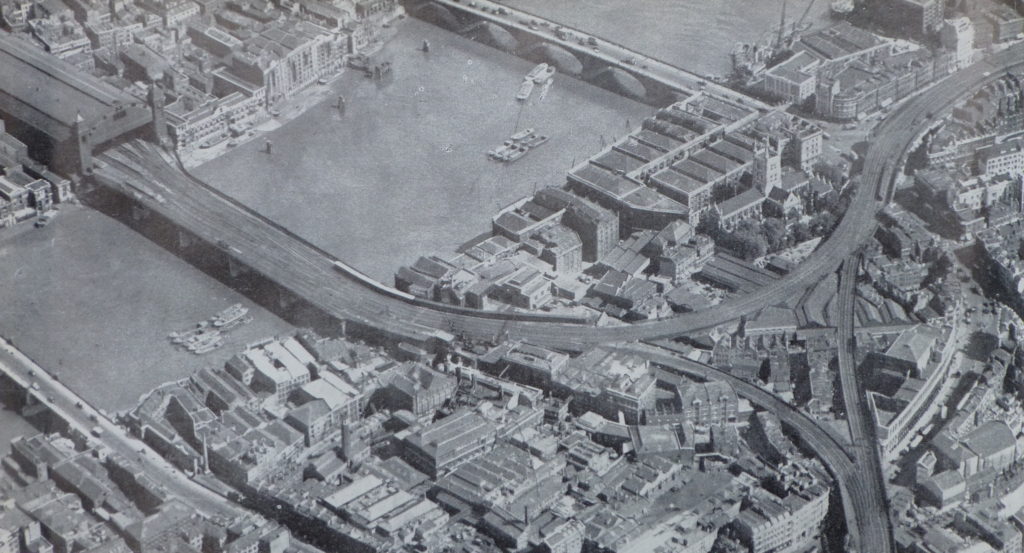

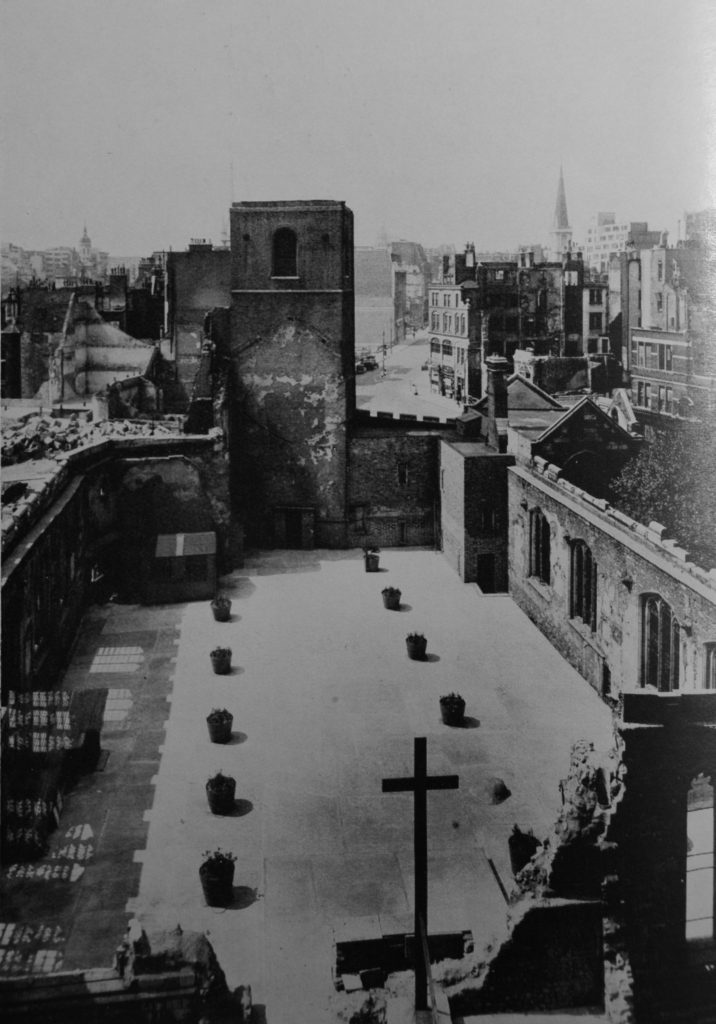

My father took the following photo of All Hallows by the Tower in 1947.

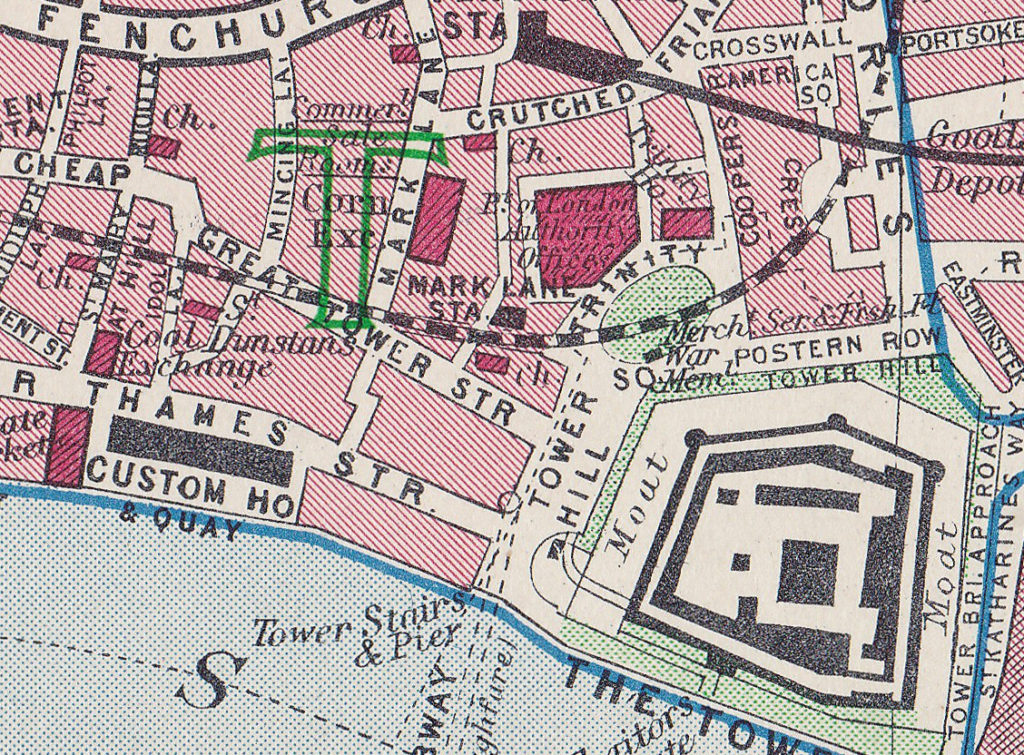

The photo was probably taken from Beer Lane, a street that once ran from just in front of the church down to Lower Thames Street. The old Port of London Authority building is in the background and the buildings that once ran along the edge of Tower Hill are on the right.

Beer Lane does not exist now, and the area to the south of All Hallows by the Tower is occupied by the recent development, Tower Place. Trying to take a comparison photo of the church is the only time I have been stopped taking a photo in London.

Tower Place consists of two buildings forming the two sides of a V shape. In between the two buildings is a large glass atrium that looks to be part of the open space in front of the church. Walking into this atrium I was swiftly told by the security people who appear to be permanently wandering around the area, that I could not take photos (despite explaining what I was doing and also that the photos were not of Tower Place).

Tower Place (and if I remember correctly the building that was here before the Tower Place development) is an example of how streets such as Beer Lane disappear and become private space.

I wanted to get the old Port of London Authority building in the background, however as I could not get far enough back from the church, the following photo is the best I could get to compare with my father’s photo.

Only the outer walls of the church along with the tower survived the war. The restored church was reopened in 1957 and although the construction of the church appears traditional, reinforced concrete beams were used to carry the roof. The 17th century tower was capped by a ‘renaissance’ style steeple.

An earlier tower to the one we see today was badly damaged in an explosion caused by gunpowder being stored in some nearby buildings in 1649. The current tower was completed in 1659 and is the only surviving feature on a City church dating from the Commonwealth period after the Civil War. It is this tower from which Pepys watched the Fire of London. His diary entry for the 3rd of September 1666 reads “I up to the top of Barking steeple and there saw the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw”.

So many interior features was lost during the blitz, including the original pulpit (1613), reredos (1685), altar table (1636) and a chancel screen from 1705 which had been a gift from the Hanseatic League.

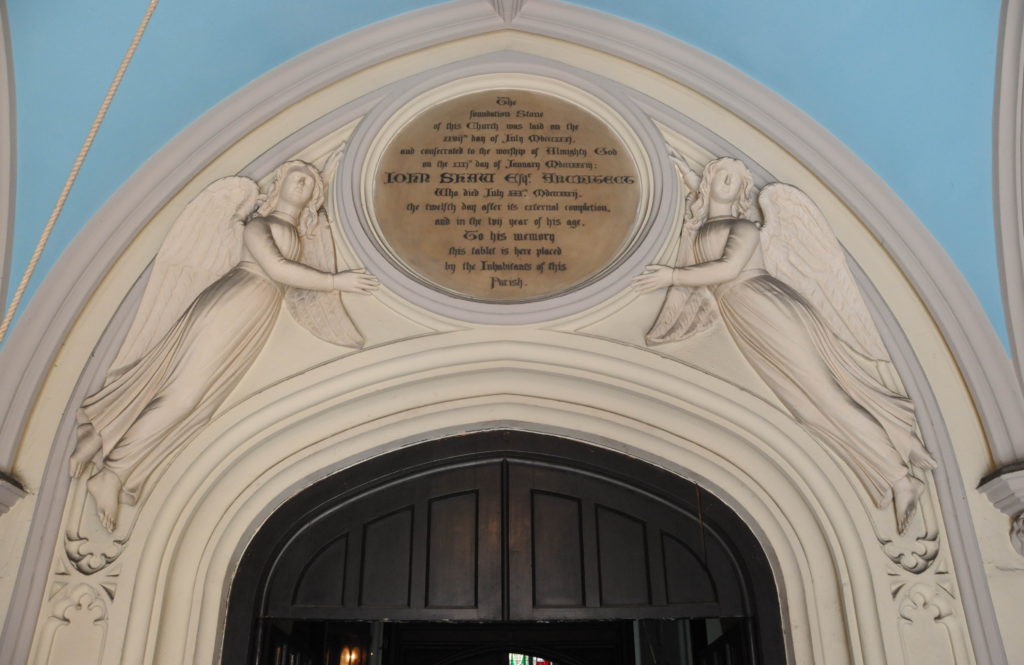

The restoration of All Hallows by the Tower created the interior we see today. It is remarkable that everything in the photo below is part of the post war restoration with the exception of the exterior wall.

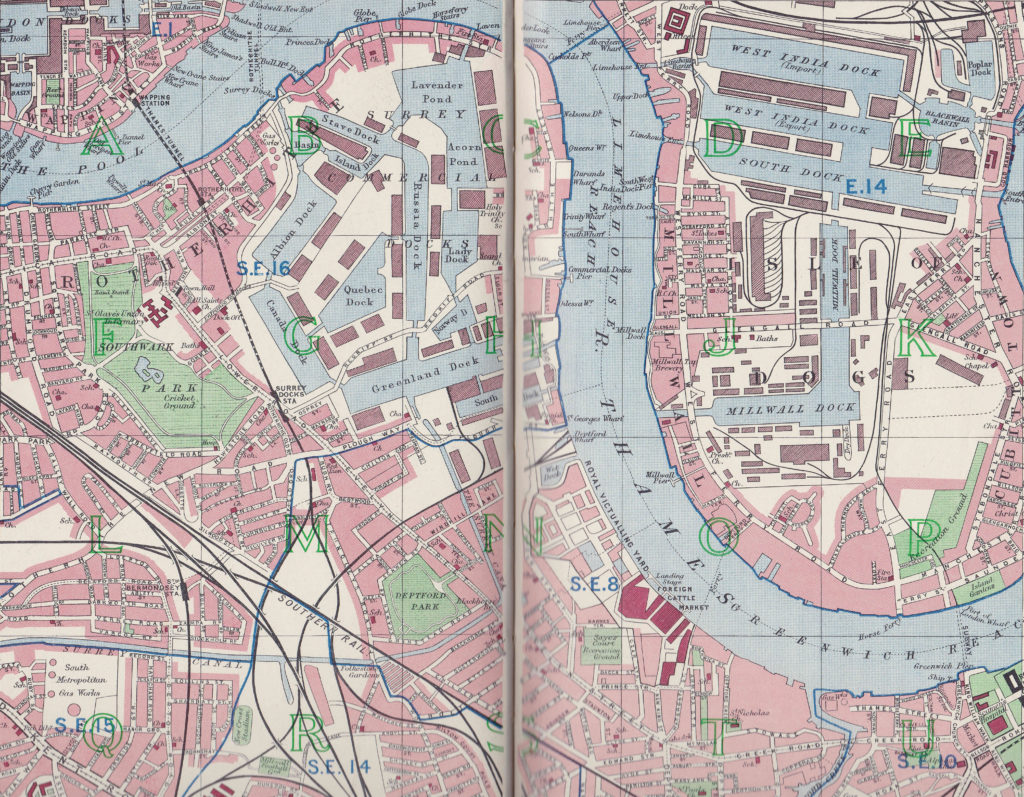

Whilst my father’s photo shows the view from the outside, it does not fully convey the level of damage within the church. The following photo is from the 1947 publication “The Lost Treasures of London” by William Kent and shows that apart from the tower and the external walls, there is nothing left of the church.

The original font was destroyed in the war. The new font was carved by a Sicilian prisoner of war known only by the name of Tulipani in 1944 using limestone from Gibraltar and is a memorial to the tunnelers of the Royal Engineers who excavated tunnels in the Rock of Gibraltar during the war.

The font cover is attributed to Grinling Gibbons and from 1682. It is one of the finest of the period.

Whilst the font was destroyed in the blitz, the font cover had been moved to St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The proximity of All Hallows by the Tower to the Tower of London and the execution place on Tower Hill meant that many of those who were executed were then carried into the church. This includes Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey and 26 years later his son, Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk. Lord Thomas Grey (the uncle of Lady Jane Grey), Cardinal Fisher and Archbishop Laud.

The Calendar of State Papers from June 2nd 1572 records the fate of Thomas Howard:

“His head being off, his body was put into a coffin belonging to Barking Church and the burying cloth of the same Church laid on him. He was carried into the Chapel of the Tower by four of the Lieutenant’s men and there buried by the Dean of St. Paul’s, he saying the service according to the Queen’s book without any other preaching.”

The church was also used as a temporary resting place following execution. William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury was executed on the 10th January 1645 and the body was buried in a leaden coffin at All Hallows Barking by the Tower of London. Twenty years later, on July 24th he was then laid in a vault at St. John’s College, Oxford at 10 pm, having been “the day before taken from London, where he was buried.”

All Hallows by the Tower has numerous nautical associations and reminders of these can be seen throughout the church, including some superb model ships.

The pulpit. This was originally in the church of St. Swithin in Cannon Street and is dated to around 1682. St. Swithin was one of the City churches destroyed by bombing and not rebuilt.

Looking down the length of the church towards the organ. Remarkable that everything in this photo is from the post war reconstruction. After the war the church was an empty shell with nothing between the outer walls.

In the Lady Chapel is the following tomb of Alderman John Croke from 1477. It was destroyed during the war, but rebuilt and restored from the remaining fragments.

The 16th century monument to the Italian merchant Hieronimus Benalius who lived in nearby Seething Lane and died in 1583 and left instructions for Mass to be said for his soul.

A niche in the wall holds a 17th century wooden statue of St. Antony of Egypt.

Ornate Sword Rest:

At the western end of All Hallows by the Tower is the Saxon arch that was uncovered during the last war by the bomb damage to the church. The date of the arch is variously given as the 7th, 8th and 11th century. The Bradley and Pevsner Guide to City Churches states that an 11th century date is preferred.

Although I suspect the arch will never be accurately dated, the key point is that the arch is pre-Norman and highlights the antiquity of the church. Also interesting to see Roman bricks within the arch – reuse of building material from much earlier London buildings.

Beneath the church is the Crypt Museum. This is a remarkable place, not just for the exhibits, but for the sense that here, below ground level, we are close to the early years of London.

I was in the Crypt Museum for about 15 minutes and during this time there was no other visitor. This solitude enhanced the sense of the antiquity of the crypt, but it is a real shame as both the church and the crypt museum are superb and deserve support and visitors.

On climbing down the steps from inside the church, this is the view along the crypt museum. On the floor in the foreground is the tessellated pavement from a 3rd or 4th century Roman house. Although this has been recently relaid, there is an in-situ Roman pavement which I will come to later.

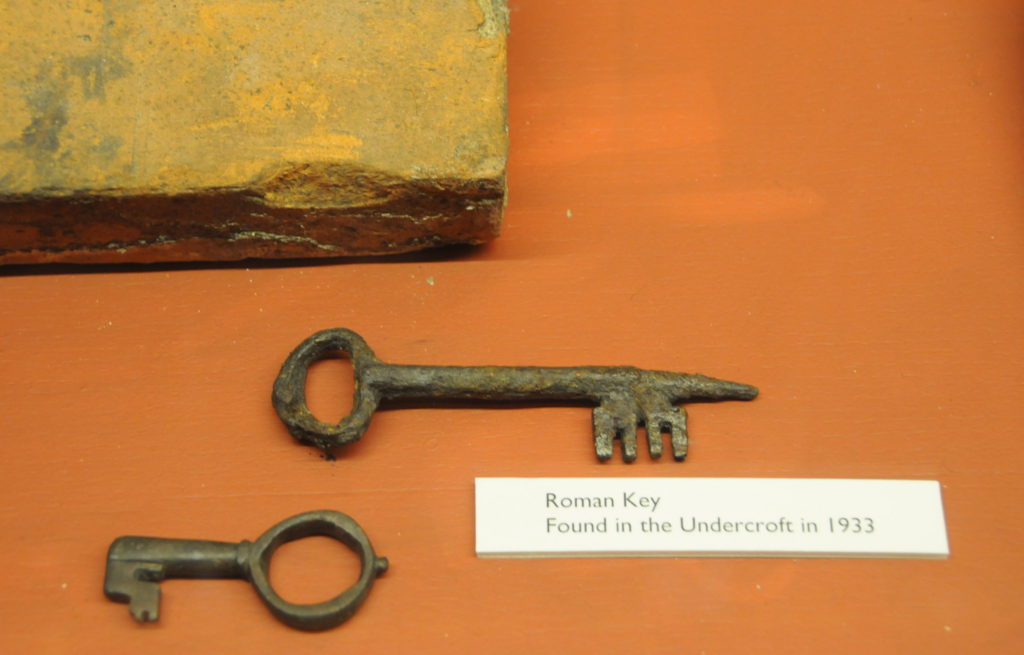

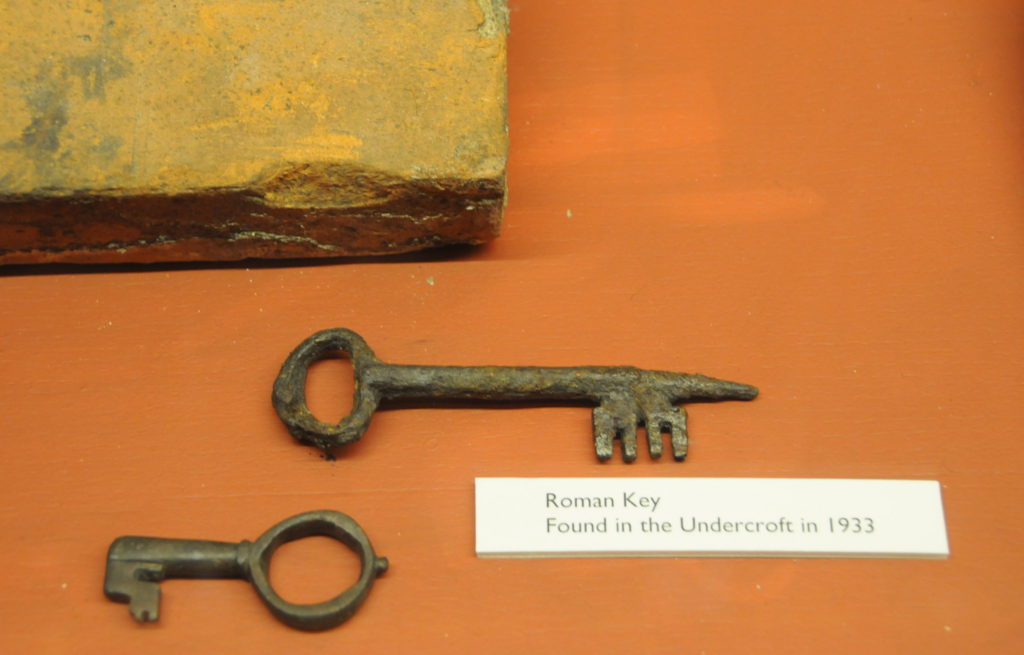

The crypt museum has on display many of the artifacts that have been discovered in and around the church.

There are also recent exhibits which tell of the history of the church during the 20th century including the remains of the north door, constructed in 1884, but damaged during incendiary bombing on the night of the 29th December 1940.

Along with the plaque that records the baptism of William Penn, the founder of the US state of Pennsylvania in the church on the 23rd October 1644.

In addition to the relaid Roman pavement shown above, the Crypt also has an in-place, perfectly preserved floor of a 2nd or 3rd century domestic house. The gully in the centre is thought to be the location of a wall and traces of plaster have been found on the edge. The pavement is cut across by one of the walls of the original Saxon church.

There are many places in London where Roman remains can be seen, however, looking on at this Roman floor, in its original setting, in a quiet and empty crypt has to be my favourite – those early Londoners who would have walked across this floor feel very close.

Standing here also shows the layers that have built up London. The original Roman floor, the Saxon foundations, wall and arch, elements of the Medieval church which can be found above, along with the 17th century church tower which looked down on and survived the Great Fire, 20th century destruction and restoration – almost 2,000 years of London history in one place.

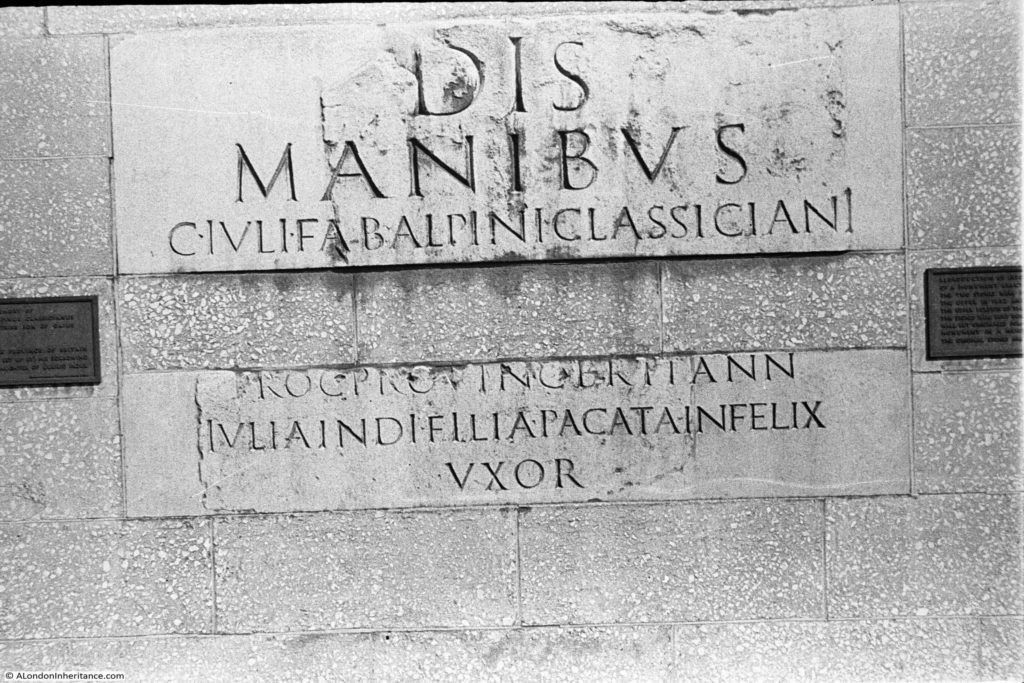

As well as the Saxon arch, damage during the blitz also revealed a number of other pre-Norman remains that had been embedded in the fabric of the church.

The Rev. P.B. Clayton describes the finds:

“Out of the wall adjacent to the arch great fragments fell, which had for at least 800 years been embedded as the capstones in the strong Norman pillars of that date. Some of these stones were most remarkable. The Keeper of the Medieval Department of the British Museum announced them to be unparalleled. The pillar has preserved them to this age intact, unique, alone and unexampled. They represent a school of craftsmanship whereof we have no other evidence. They form a portion of a noble Cross which once upreared its head on Tower Hill, before the Norman William conquered London.”

The photo below is of the upper half of an original Saxon cross. Dated to the early 10th century. The inscription around the edge reads “Thelvar had this stone set up over here….” the rest of the inscription would have carried on around the missing lower half.

Part of the shaft of a Saxon cross stands in one of the alcoves. One piece of the shaft was found during clearing of the lower chapels in 1925-27 and the rest of the shaft was found in the rubble of the Nave Pillars following the blitz as described above by the Rev. P.B. Clayton. The shaft includes Anglo-Saxon knot designs along with St. Peter and St. Paul on the side panel. The shaft has an inscription which may read “Werhenworrth”.

At the end of the Crypt Museum is the Undercroft Chapel. At the far end of the chapel, above the altar can be seen the rough wall of the 14th century church. The altar stones are from Castle Athlit on the coast of what is now Israel. Castle Athlit was a Crusader castle which fell in 1291.

An unusual relic in the crypt is the original crows nest from Ernest Shackleton’s ship, the Quest. A ship that was not well suited to Antarctic exploration, the ship took Shackleton to South Georgia where he died in January 1922. Taking a route via the eastern Antarctic and Cape Town, the Quest finally returned to Plymouth on the 16th September 1922.

It is not known how the Crows Nest came to be in the possession of All Hallows, however the Rev P.B. Clayton used the Crows Nest in his fund-raising activities so he must have acquired it by some means. The Rev P.B. Clayton (who also wrote the earlier extract on finding the Saxon stones) was Vicar of All Hallows for 40 years from 1922 to 1962.

Ending my visit to the Crypt, I walked back up through the church and outside. I took the following photo of All Hallows by the Tower from Tower Hill which was as busy as usual with visitors to the Tower of London and to the river boat piers on the Thames. It is really surprising that despite being this close to Tower Hill there were so few visitors to All Hallows and that I had so long in the Crypt on my own.

View from the east of the church.

All Hallows by the Tower from across Byward Street, during a brief gap in traffic.

All Hallows by the Tower encapsulates London’s history, from the earliest Roman times to the destruction of the mid 20th century and the restoration that followed. Well worth a visit, and perhaps one day I will get to take a photo of the church from under Tower Place’s atrium.

alondoninheritance.com