Much of what I have written so far has been about the physical change across London. How the buildings and streets have changed so considerably over the last 70 years, however there are many other ways in which London has changed and for this week’s post I want to use a series of photos to show that whilst a specific area has not changed that much physically, it is now playing a very significant role in London’s position as one of the major world tourism destinations.

Tower Hill is the area to the north-west and western side of the Tower of London. Tower Hill, in the words of Stow was:

“sometime a large plot of ground, now greatly straitened by encroachments (unlawfully made and suffered) for gardens and houses. Upon the hill is always readily prepared, at the charges of the City, a large scaffold and gallows of timber, for the execution of such traitors or transgressors as are delivered out of the Tower or otherwise, to the Sheriffs of London by writ, there to be executed.”

There is a long list of those executed on Tower Hill, with the last being the execution of Lord Lovat on April 9th 1747. At this execution, a scaffolding built to support those wishing to view the execution collapsed with nearly 1,000 people of which 12 were killed. Apparently, Lovat “in spite of his awful situation, seemed to enjoy the downfall of so many Whigs”.

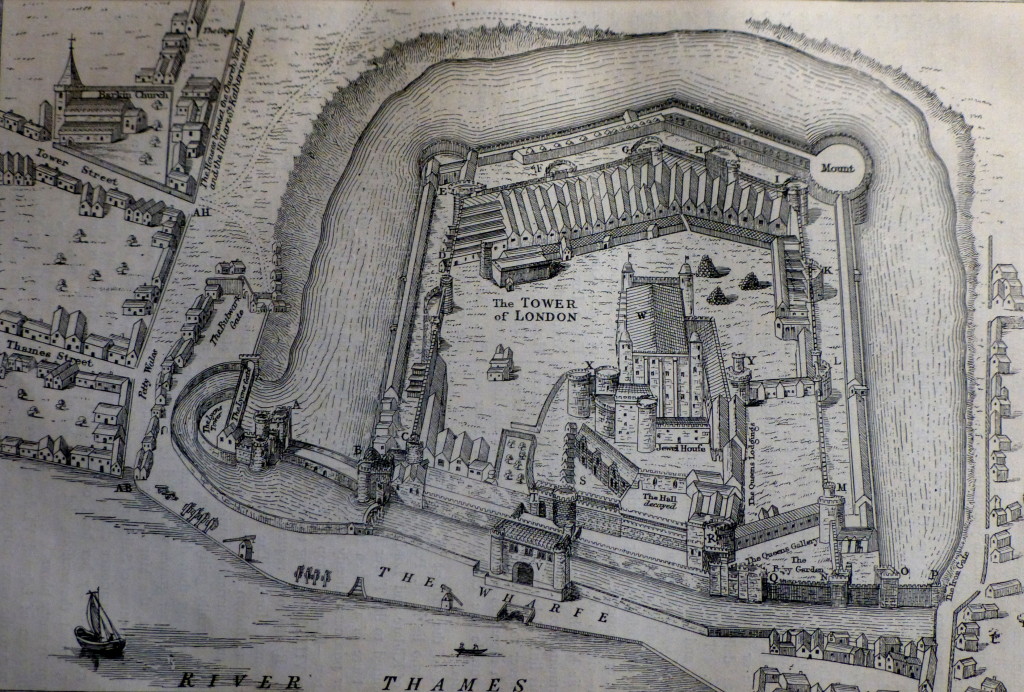

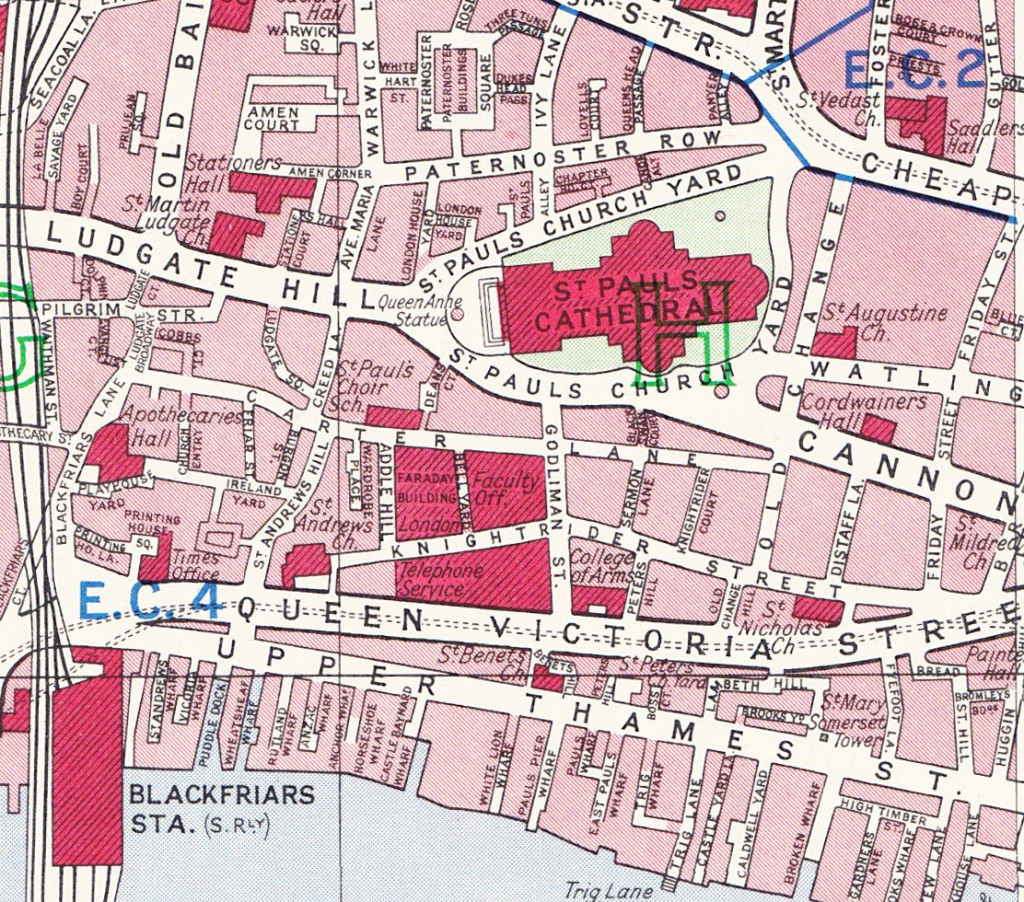

The following shows the Tower of London from a survey in 1597 showing the moat and the area to the north-west and west that formed Tower Hill.

The western end of Tower Hill. as can seen in the above picture, has long been the main land based gateway to the Tower of London, countless numbers of people must have walked down Tower Hill on their way to the Tower of London, for many, not in the best of circumstances.

The moat was drained in 1843 having long been described as an “offensive and useless nuisance”. After being drained workmen found several stone shot which were identified at the time as being missiles directed at the Tower during a siege in 1460 when Lord Scales held the Tower for Henry VI and the Yorkists cannonaded the fortress from a battery in Southwark.

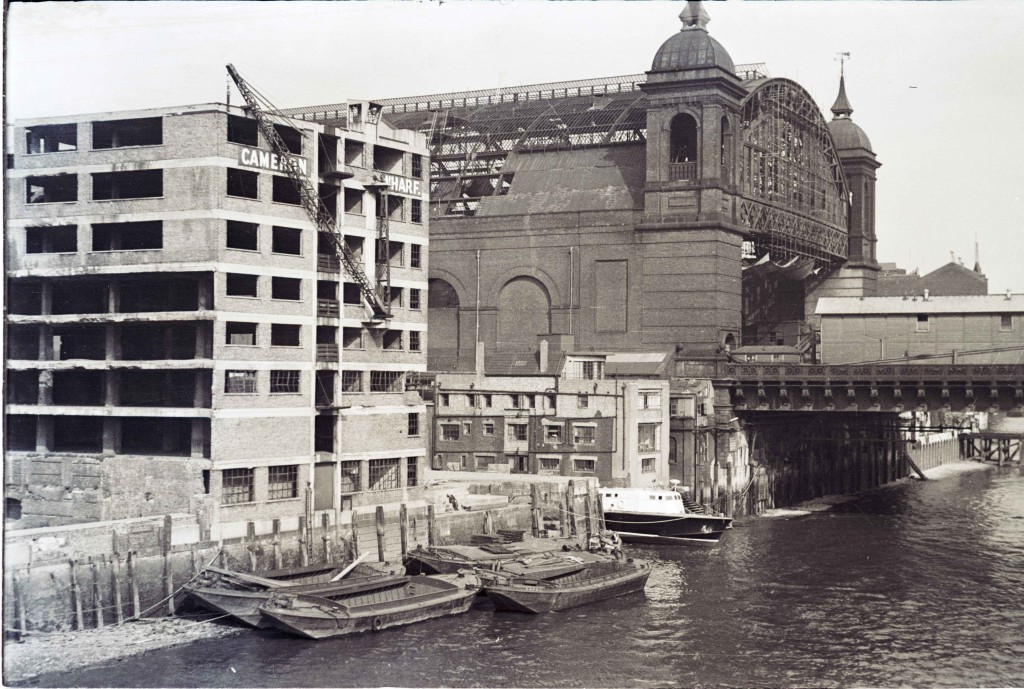

The following postcard is from the first decade of the twentieth century. I suspect it was taken from the top of the tower of All Hallows by the Tower looking over the Tower of London with part of Tower Hill in the foreground with the approach running down towards the main entrance on the right. Transport is lined up along the approach, taking visitors to and from the Tower.

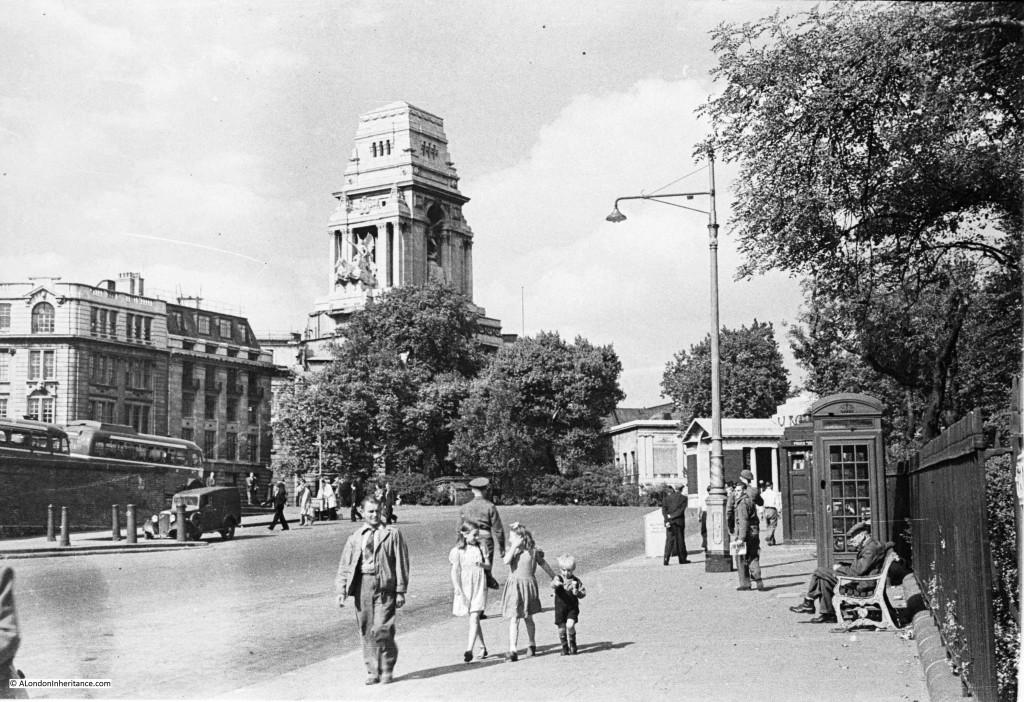

My father took the following photo looking up Tower Hill from a position to the extreme right of the above photo in 1948 (all of the following three photos from 1948, 1977 and 2014 were taken in the summer at roughly the same time, early afternoon as can be seen by the direction of the shadows).

The moat is just over the railings to the right. The large building behind the trees is the Port of London Authority headquarters. From the Face of London by Harold Clunn:

“Many courts and alleys were swept away between 1910 and 1912 to make room for the new headquarters of the Port of London Authority. This magnificent building, designed by Sir Edwin Cooper, stands on an island site enclosed by Trinity Square, Seething Lane and the two newly constructed thoroughfares called Pepys Street and Muscovey Street. Constructed between 1912 and 1922, it has a massive tower rising above a portico of Corinthian columns overlooking Trinity Square, and the offices are grouped around a lofty central apartment which has a domed roof of 110 feet in diameter”.

The “massive tower” is a very striking local landmark both from the surrounding streets and from the Thames.

The colonnaded building which can partly be seen at the top right of Tower Hill is the memorial to the men of the Merchant Navy and the fishing fleets who died in the two world wars. Some 36,000 names are listed of men who “have no grave but the sea”.

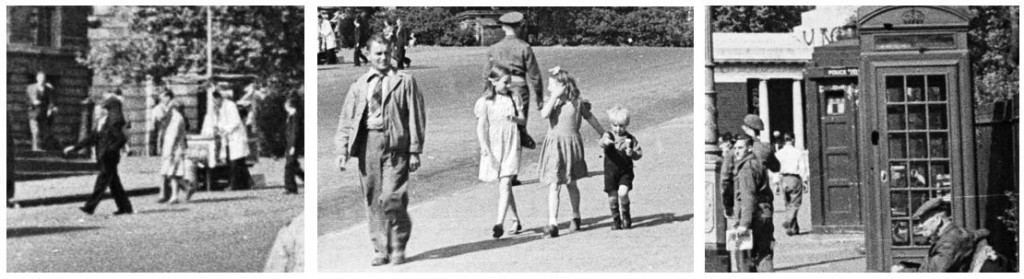

I find the detail of these photos fascinating, from left to right below. An Ice Cream seller in a white coat with his ice cream cart, one of which was bought for the boy in the middle photo and on the right behind the phone box is a Police Box, probably better known these days as a Tardis. Note also how common military uniforms were on the streets of London, even three years after the war had ended.

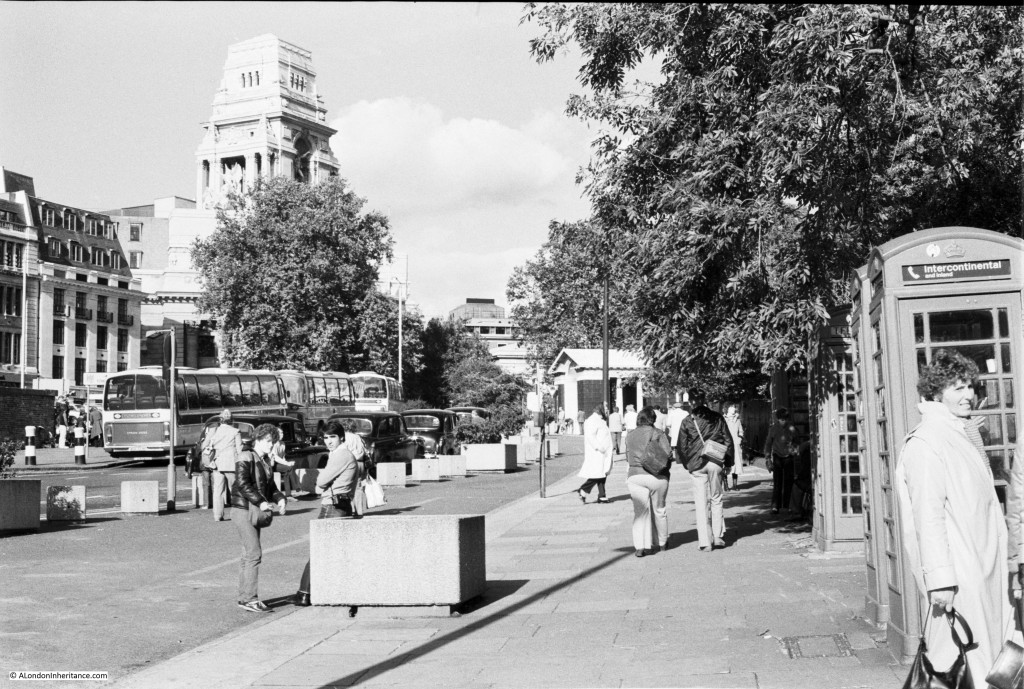

Now fast forward 29 years and I took the following photo in 1977 when I first stated taking photos of London with a Russian Zenit camera (all that pocket-money could stretch to at the time). The camera had a tendency for the shutter to stick and unlike digital cameras, you did not know this until after the film had been developed. This is one of the photos where it actually worked.

The scene is very similar. the coaches show the start of mass tourism to London and there are additional telephone boxes including one for Intercontinental Calls (this was still at a time when intercontinental calls were the exception and expensive to make).

Now fast forward again another 36 years and I took the following photo in early August 2014. Fortunately I now have a much better camera and I thought converting to Black and White would allow a better comparison with the previous photos.

When I took this, planting of the poppies for the “Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red” installation had only just begun and it had not generated the level of visitors seen in October and the start of November. This was a typical summer’s day on Tower Hill.

This photo also has cranes in the background which now appears to be mandatory for any photo within the City.

The Tower of London is now one of the major tourist attractions in London as can be seen on almost any day in Tower Hill. New ticket offices, food outlets and visitor displays have been built down the left hand side, the telephone boxes have disappeared and the ice cream seller with his ice cream cart from 1948 would be hard pressed to manage the industrial scale of ice cream vending now seen on Tower Hill on a summer’s day.

Visitor numbers to London have risen dramatically over the last few decades. In the last ten years they have risen from 11.696 million in 2003 to 16.784 million in 2013 and the first half of this year’s numbers show a 7% increase over the first half of last year.

Of these visitors in 2013, 2.894 million visited the Tower of London in 2013. I doubt that these numbers could have been imagined on that summer’s day in 1948.

Tourism is one of the many factors that are changing the face of London, and with numbers continuing to increase this influence will continue.

I recommend a visit to Tower Hill late on a cold winter’s evening, when it is possible to look over the moat, across to the Tower without the noise and hustle of the crowds and with a little imagination, see the Tower as it has been for centuries as a functioning garrison, fortress and prison. There is also an opportunity to briefly experience the Tower at night. The Ceremony of the Keys takes place every night with admittance starting at 9:30 pm. Whilst with modern-day security systems this ceremony is now probably more ceremonial than functional it does provide a glimpse of the Tower at night and of a ceremony which has been in existence for at least 700 years. Again, a cold winter’s evening is the best time to experience this event. Tickets are free from Historic Royal Palaces and can be found here.

You may also be interested in my post on the Tower Hill Escapologist which can be found here

The sources I used to research this post are:

- London by George H. Cunningham published 1927

- Old & New London by Edward Walford published 1878

- The Face of London by Harold Clunn published 1932

- The London Tourism numbers are from the Greater London Authority Data Store which can be found here

- Figures for visitors to the Tower of London are from the Association of Leading Visitor Attractions and can be found here (which also has a fascinating list of visitor numbers to the majority of UK attractions)