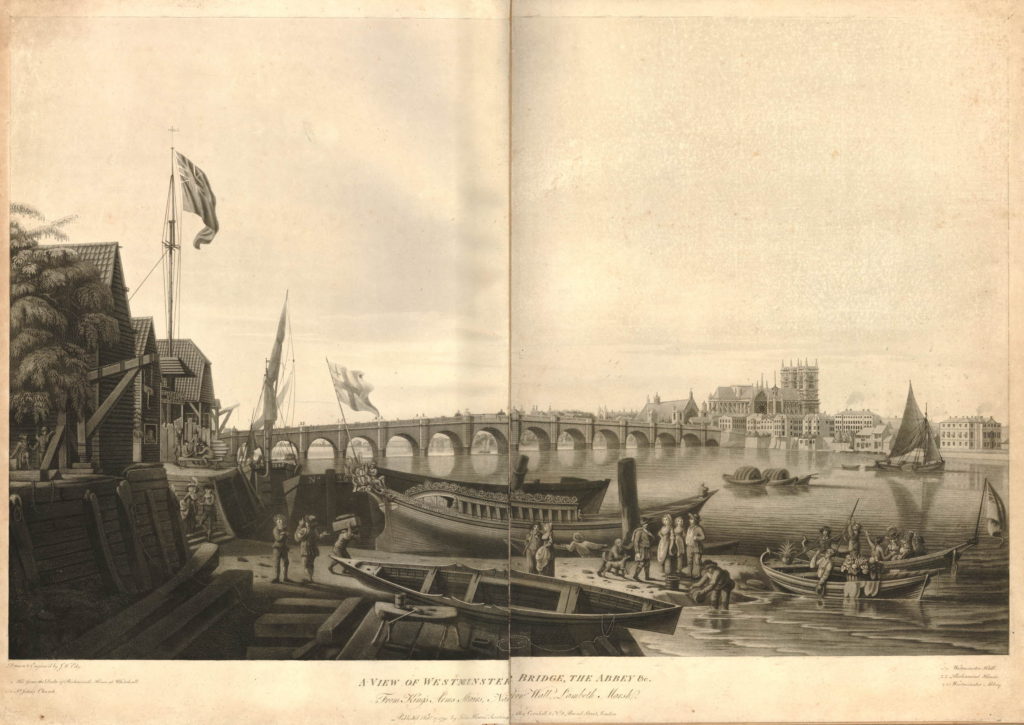

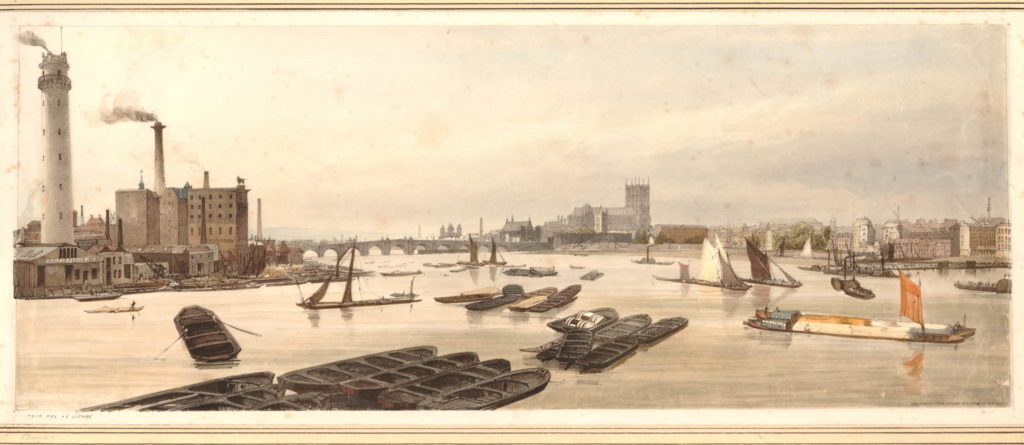

Today, the River Thames runs between embankments on the north and south sides of the river, embankments built over the last 160 years, and were still being completed in the 1980s. For centuries the river had an extended foreshore which would shift with the tides, and particularly on the south bank, large areas of wet, marshy land.

One stretch of the embankment, built during the first decades of the 20th century, is the stretch in front of County Hall, the purpose built home of the London County Council, then the Greater London Council, and now home to hotels and tourist attractions.

County Hall photographed from Westminster Bridge:

The London County Council was formed in 1889 to replace the Metropolitan Board of Works and to gradually take on powers covering Education, Health Services, Drainage and Sanitation, Regulation and Licensing of a whole range of activities, dangerous materials, weights and measures, street Improvements – there was hardly an aspect of living in London that would not be touched by the LCC.

The problem with having all this responsibility was that the LCC also needed the space for all the elected officials and the hundreds of staff who would deliver the services.

The LCC initially had an office at Spring Gardens, near Trafalgar Square, the old home of the Metropolitan Board of Works, but quickly started looking for a new location as staff began to be scattered across the city.

A wide range of locations were suggested, but they were either too small, too expensive or too close to the Palace of Westminster – the London County Council wanted to be seen as a completely separate authority to the national government, but still wanted a prominent location, suitable for the governance of London.

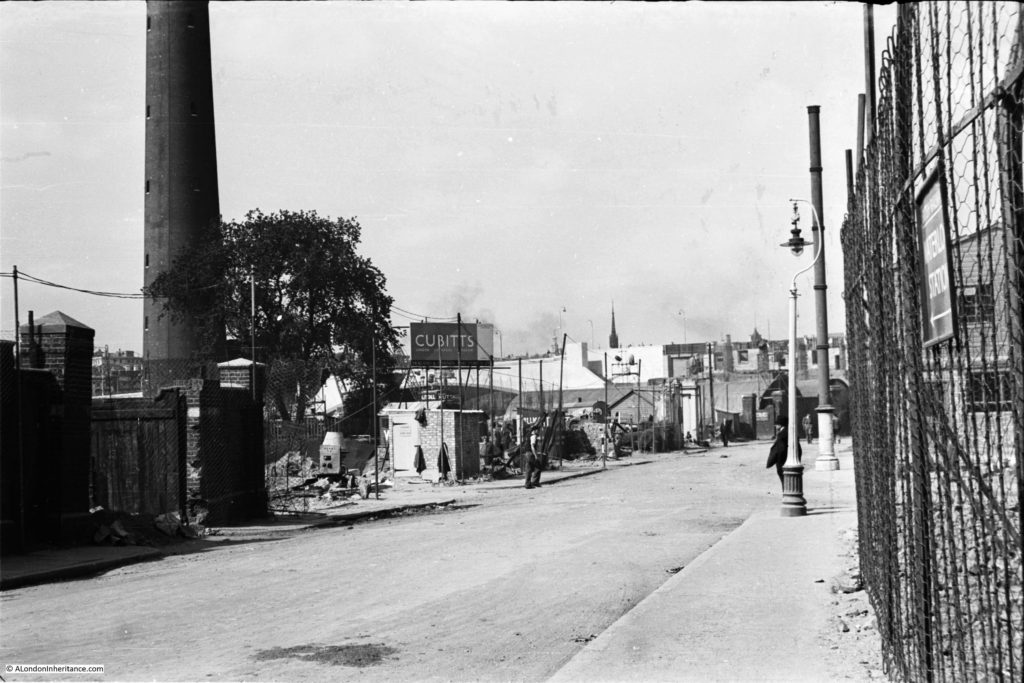

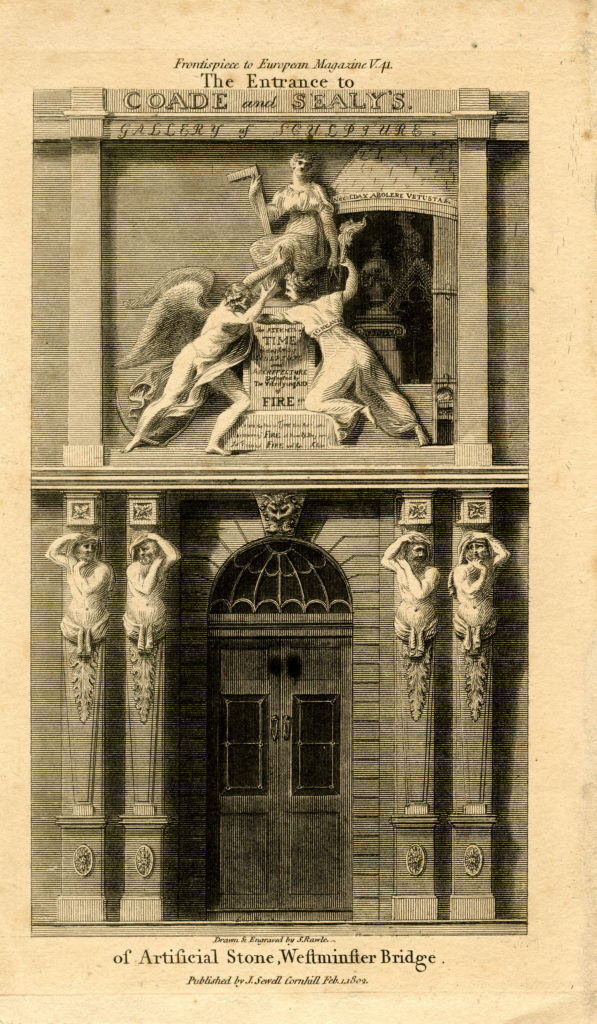

The LCC already had a Works Department which occupied a small part of a site on the South Bank, to the side of Westminster Bridge.

The new St Thomas’ Hospital on the other side of Westminster Bridge had already started the improvement of the Lambeth side of the river, which included the creation of a large formal embankment.

The land across Westminster Bridge Road from the hospital provided a sufficient area for the LCC with space to grow. It was in a prominent position, directly facing onto the river, and importantly was on the opposite side of the river to the Palace of Westminster so was close to, but separate from the national government.

As the site was being acquired, attention turned to the design of the new building, and a competition was organised to invite designs for the new home of the LCC.

There were some incredibly fancy and ornate designs submitted, however the winning design was one of relative simplicity by the 29 year old architect Ralph Knott.

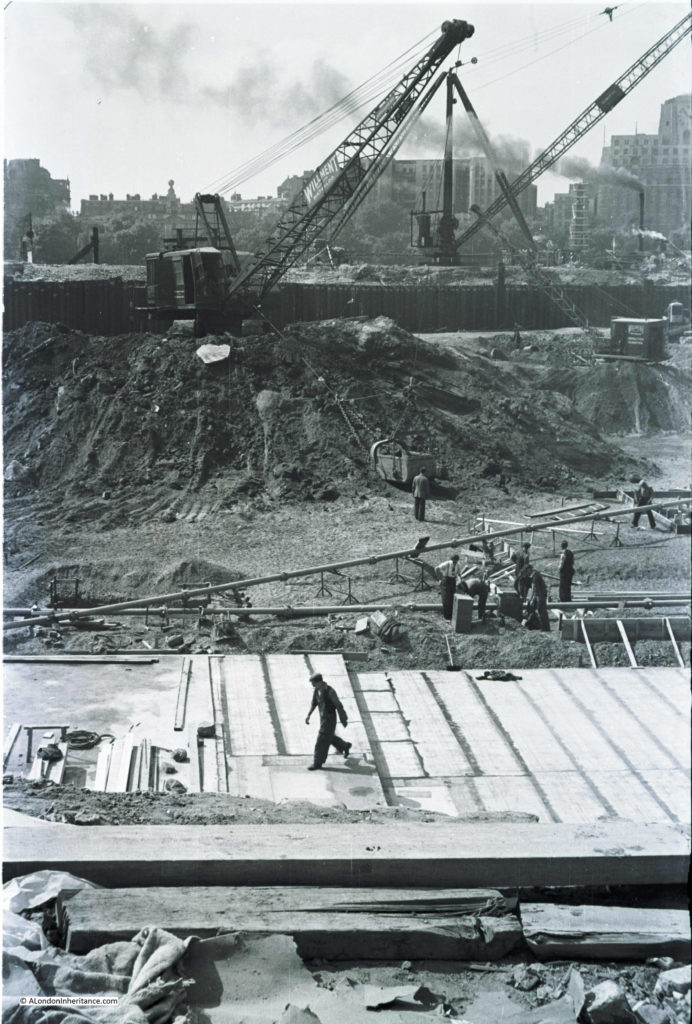

Construction of County Hall began in January 1909 with the construction of a coffer dam in the river, which allowed the new river wall to be built, reclaiming an area of land from the river. Work then began on excavation of the ground, ready for laying a concrete raft on which County Hall would be built.

Work was sufficiently advanced, that by 1912 the laying of the foundation stone could take place, and to commemorate the event, a booklet was published, providing some history of the construction of County Hall up to 1912, along with some plans and photographs of the original river frontage, and an important find during digging ready for the construction of the concrete raft.

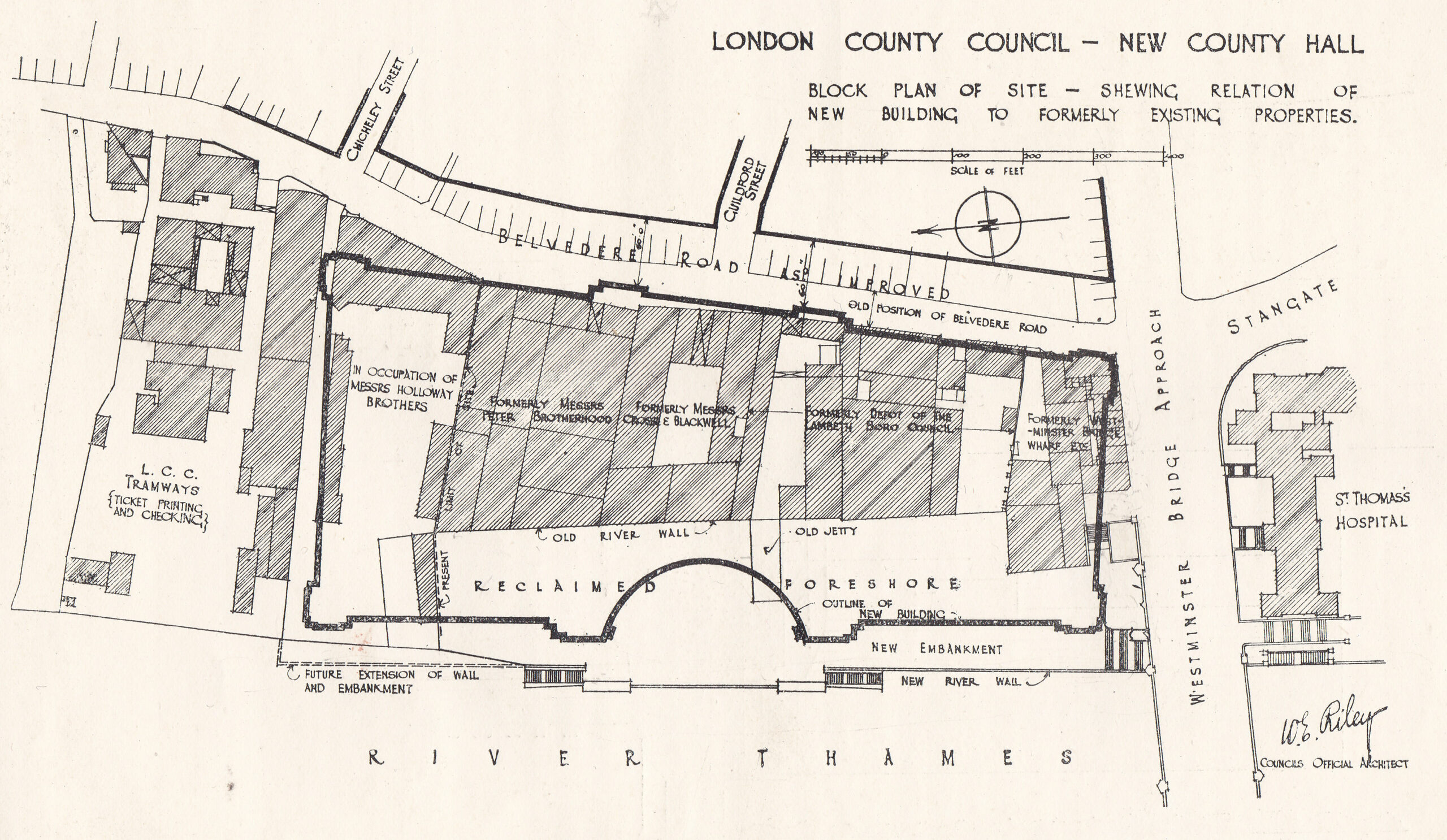

County Hall would be built on a 6.5 acre site, and to achieve this area, a significant part of the foreshore and river needed to be reclaimed. In total two and a half acres of the river were reclaimed and a new river wall constructed to hold back the Thames.

A new river wall had been part of the construction of St Thomas’ Hospital, and the alignment of this wall would be continued with the construction of County Hall.

588 feet of new river wall was constructed. the most difficult part being where the wall would come up against Westminster Bridge. The piers of Westminster Bridge had been built on timber piles, and the foundations of the river wall would go a further 6 feet deeper than those of the bridge, so careful construction was needed to avoid damage to the bridge. This included steel piles driven around the foundations of the bridge to provide some protection from the excavations of the river wall.

Construction of the wall started in January 1909 and was completed in September 1910 at a total cost of £58,000.

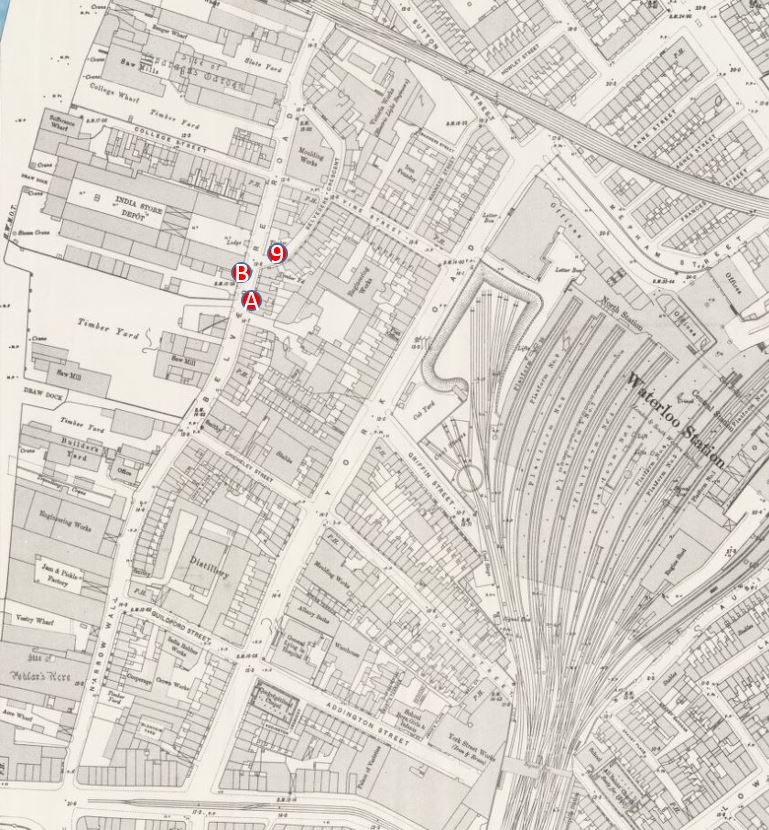

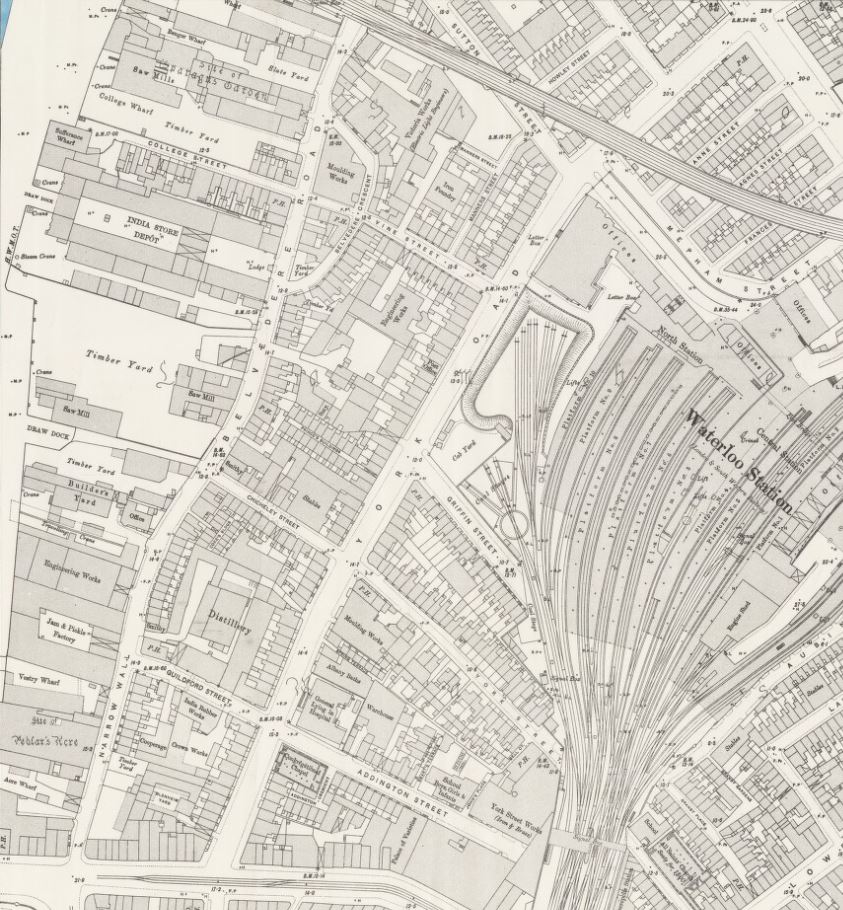

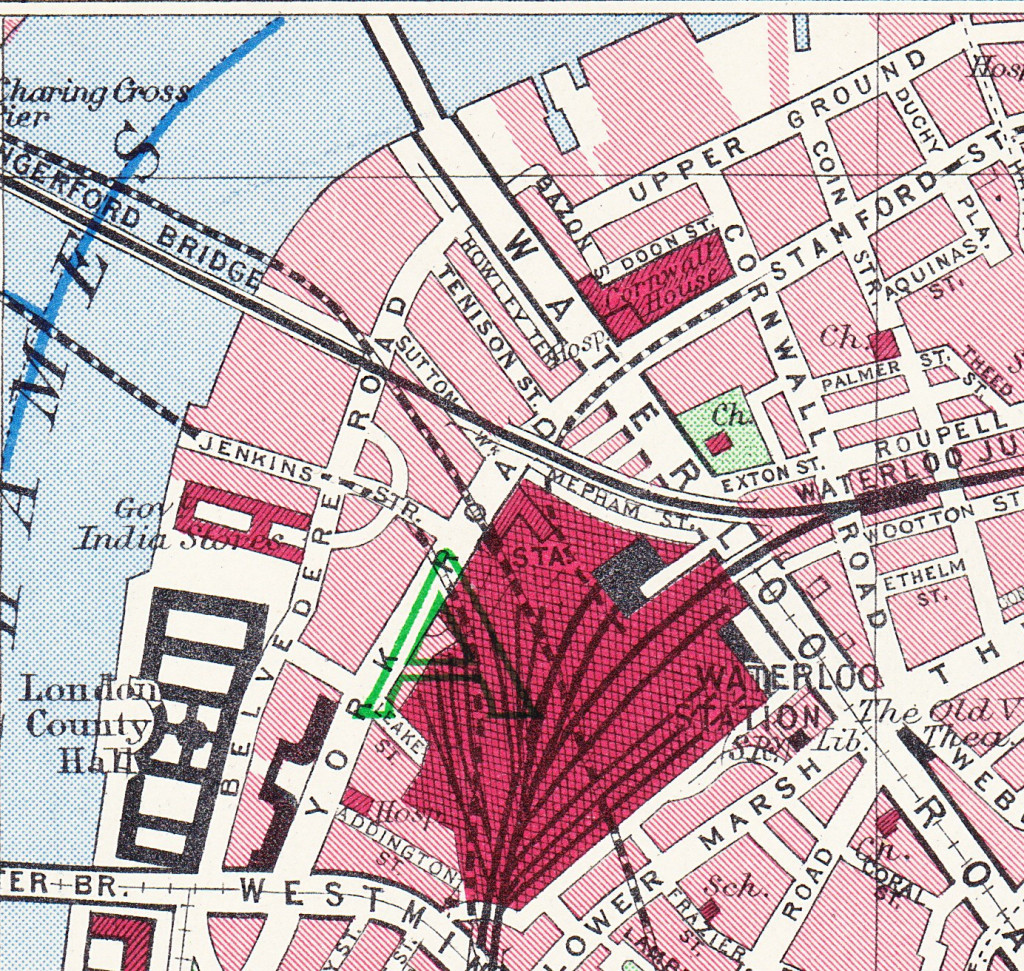

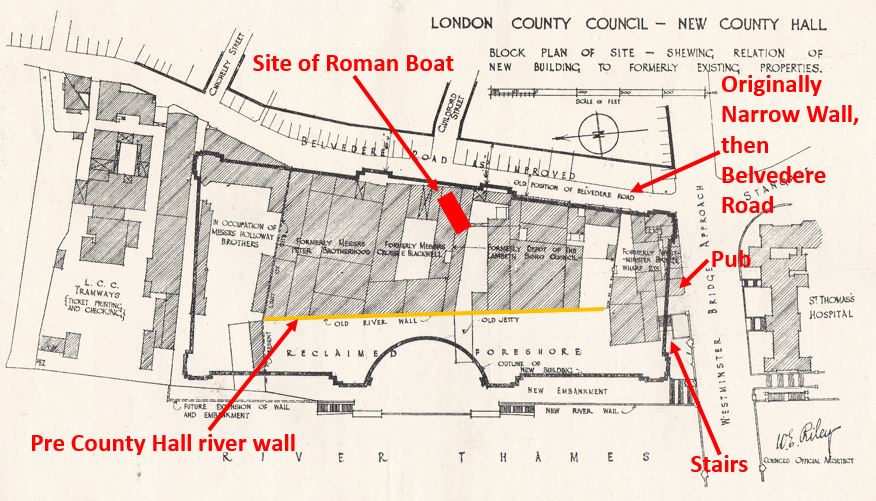

The booklet includes the following diagram which shows the outline of County Hall, the alignment of the new river wall, and within the outline of County Hall, the original buildings on the site and the alignment of the old river wall, showing just how much was reclaimed from the river.

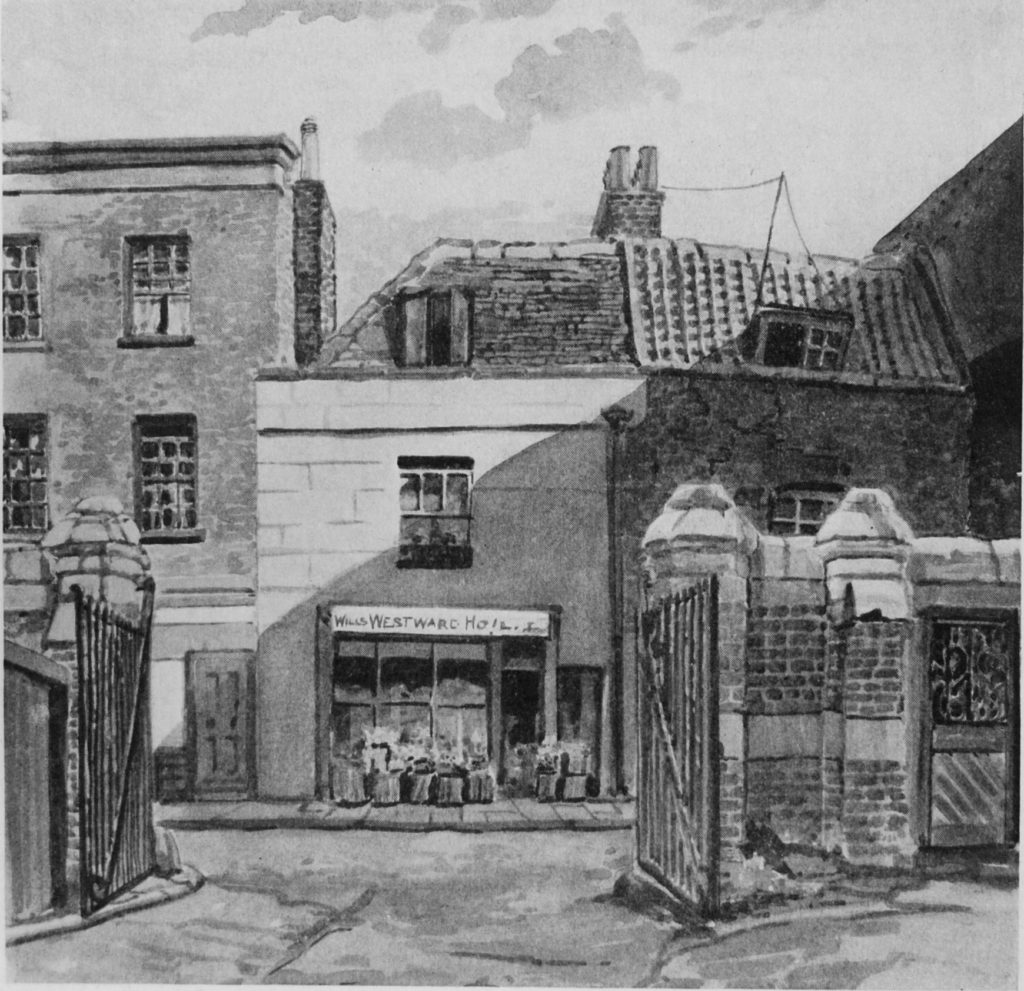

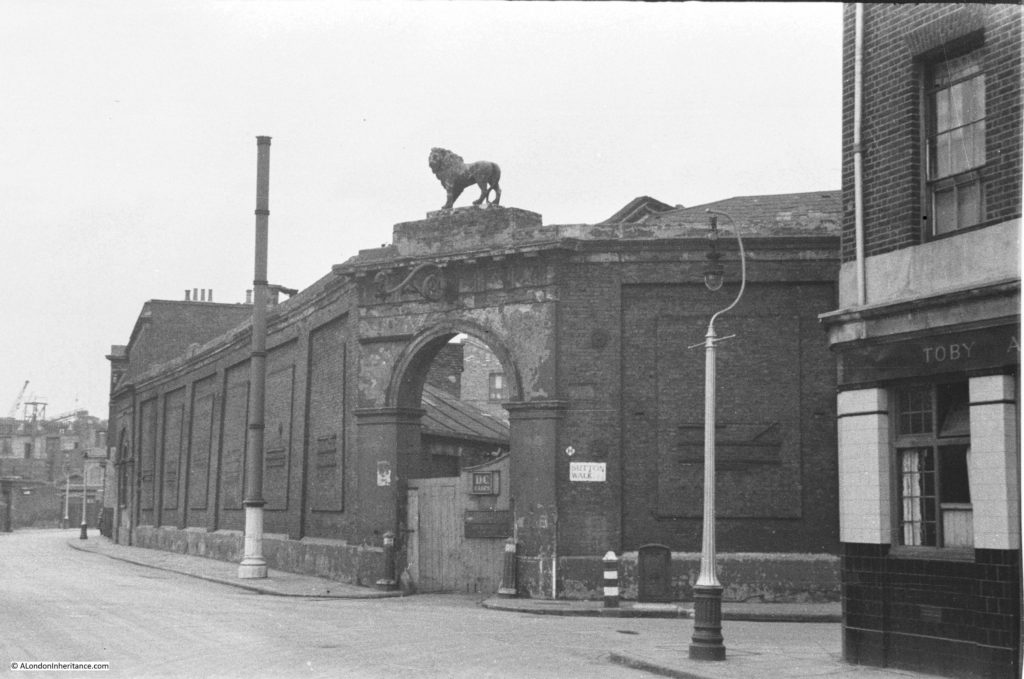

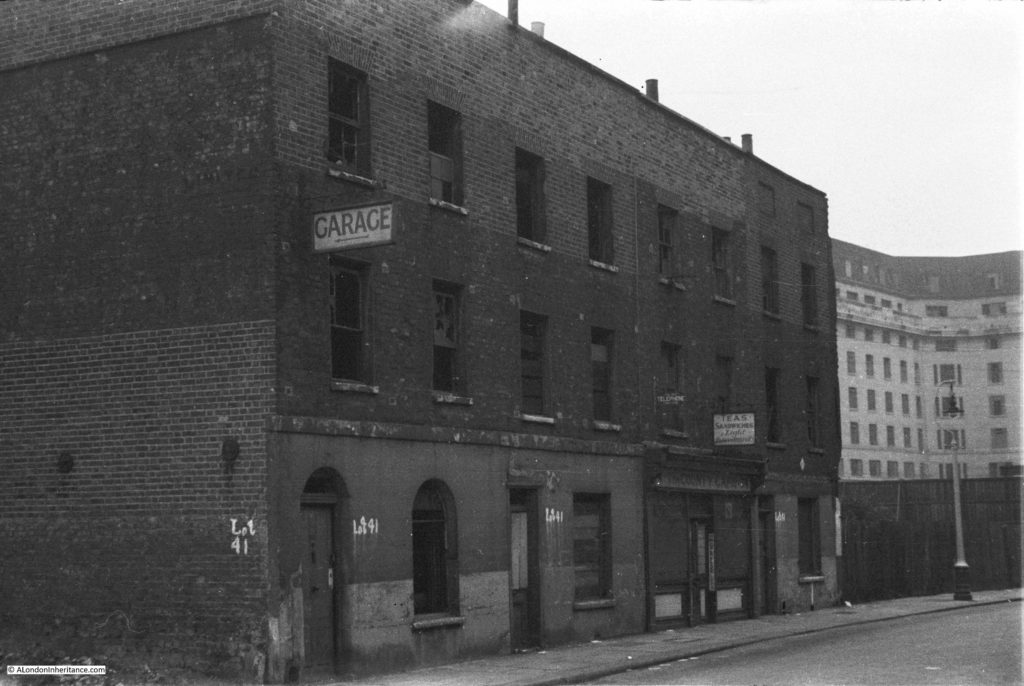

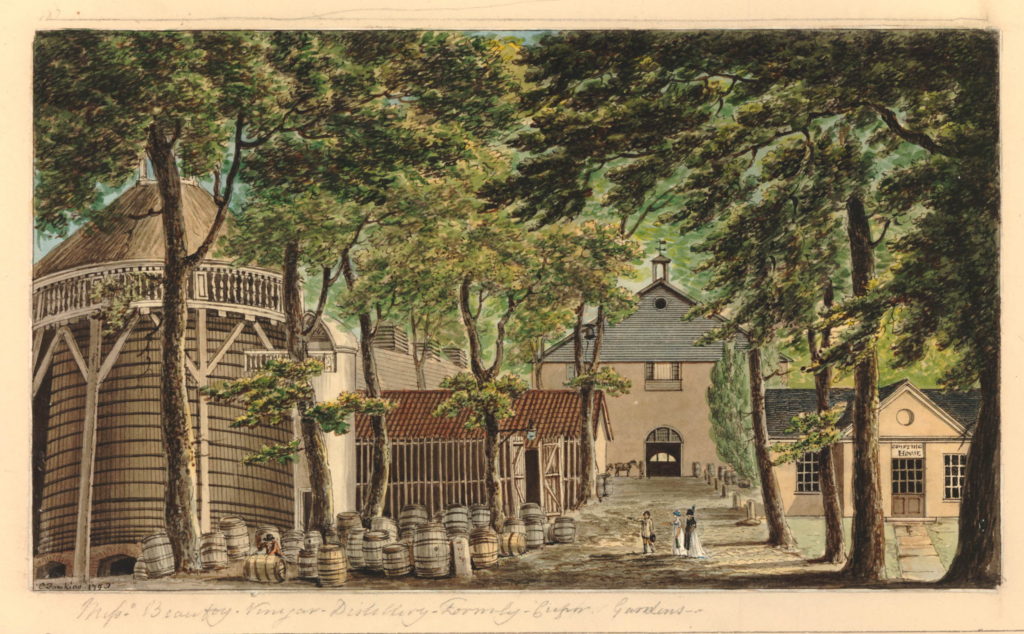

The site was occupied by businesses such as Cross and Blackwell with a jam and pickle factory, and the engineering firm of Peter Brotherhood who had their radial engine factory on the site. Their radial engine was an innovative machine used to power the Royal Navy’s torpedoes, as well as being a source of power for other machines including fans, and dynamos for the generation of electricity.

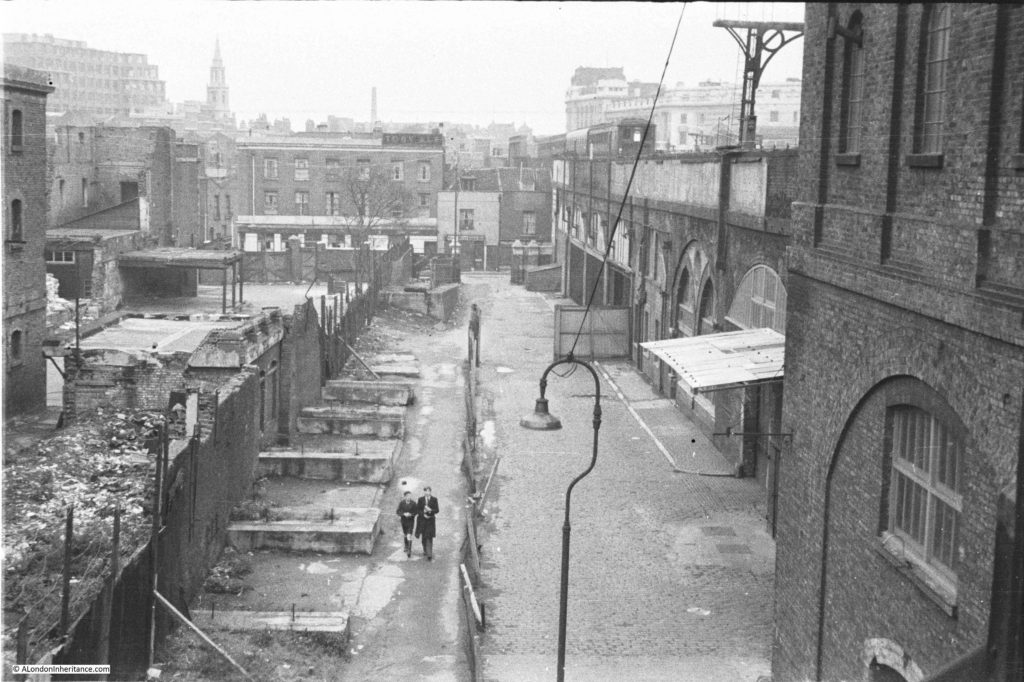

The booklet also includes the following photo of the site from Westminster Bridge. I suspect the embankment wall now runs roughly where the photographer was standing.

If you look at the edge of the photo on the right, there are a large flight of stairs leading down to the river, and at the top of the stairs can just be seen part of a pub. The pub had one side facing onto Westminster Bridge Road, and the other facing a small square and the river stairs. With limited research time, I have been unable to find the name of the pub, and it is not mentioned in the County Hall booklet.

This is the view of County Hall today, the photographer for the above photo was probably standing a bit closer to the river wall than I am, but everything in the following photo was built on reclaimed land.

The new river wall and embankment was a significant construction, and before work on this could start, a timber dam had to be built to hold back the Thames from the construction site. The dam consisted of a wall of tongue and groove timber piles, which had to be driven through four feet of mud, then eleven feet of ballast (sand, gravel etc.) before reaching London Clay, then driven further into the clay to provide a firm fixing.

This was needed as the dam would have to hold back a significant wall of water, as the tidal range could be over 20 feet, so the dam had to hold back sometimes no water (at very low tides) and at very high tides, a wall of over 20 feet of water pressing on the dam.

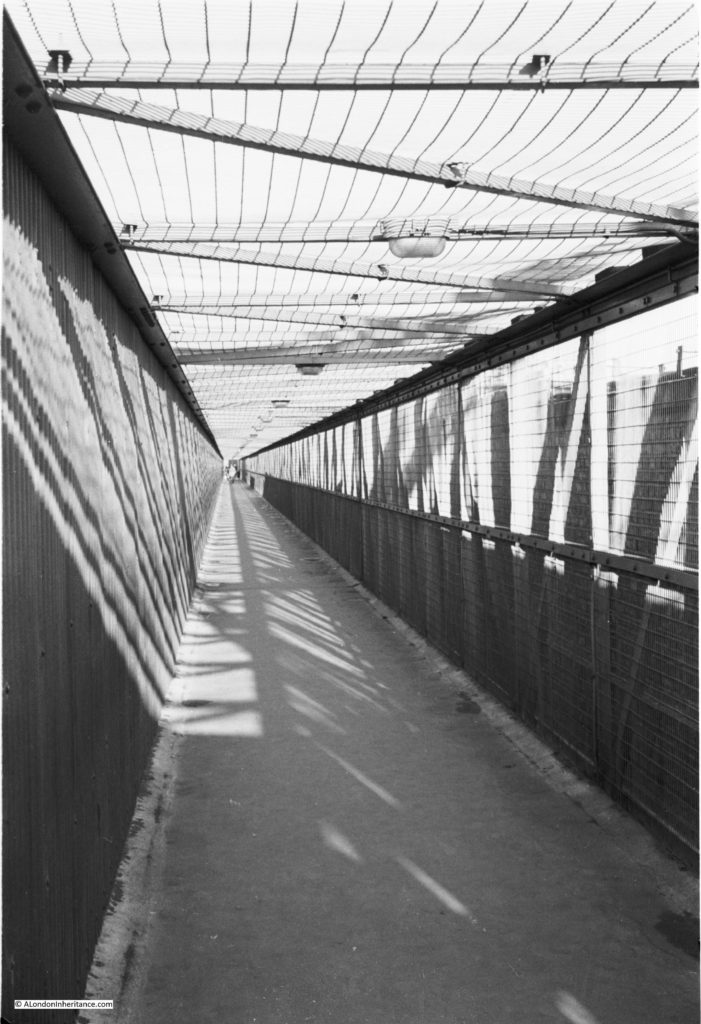

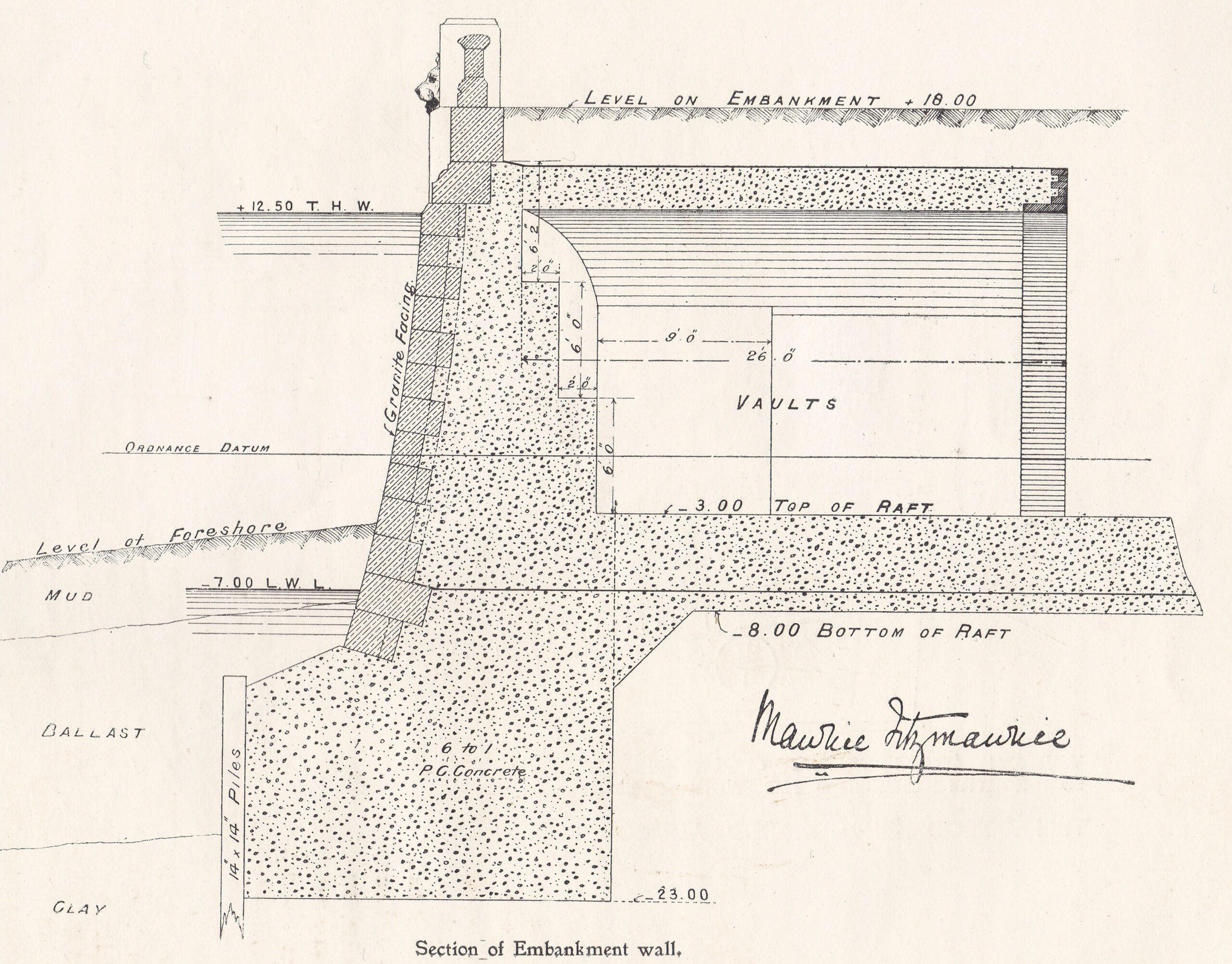

The embankment wall was a very substantial construction, reaching down over 35 feet below the original Trinity high water mark. Between the river wall and County Hall, a new public walkway was constructed, and under the walkway there were large vaults within the open space between the walkway and the concrete raft at the base.

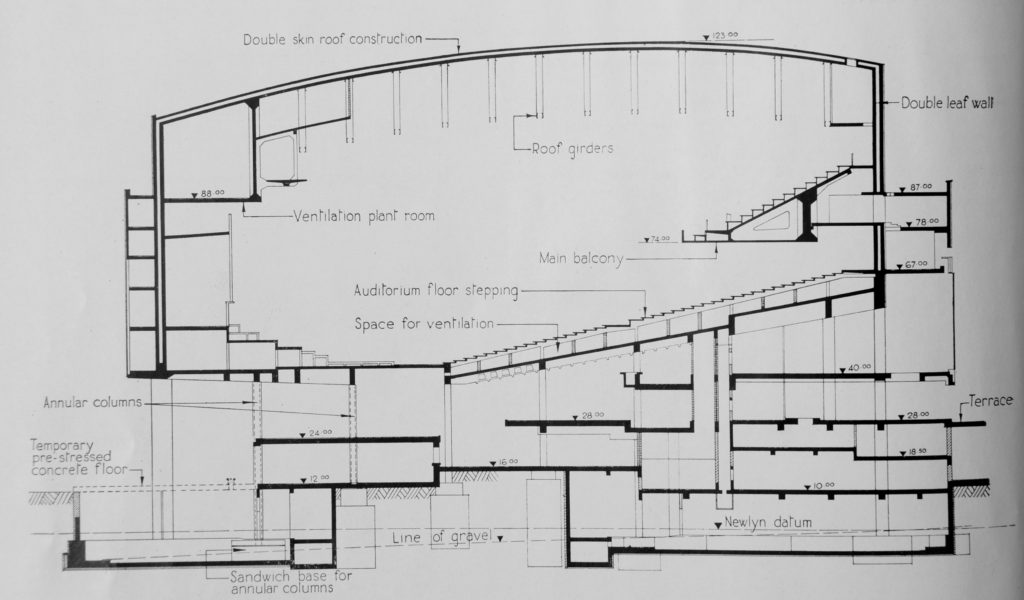

The following drawing shows the construction of the wall and embankment:

Behind the wall, a large area was excavated. Due to the marshy, damp nature of the ground a concrete raft was needed across the whole area on which County Hall would be built. It was during the excavation to build that raft that a significant discovery was made of the remains of a Roman boat, seen in the following photo as discovered:

The booklet provides a description of how the boat was found:

“The discovery was primarily due to Mr. F.L. Dove, the present chairman of the Establishment Committee. While inspecting in January 1910, with Mr. R.C. Norman, the then Chairman of the Committee, the excavation for the concrete raft, he noticed a dark curved line in the face of the excavation immediately above the virgin soil, and some distance beneath the silt and the Thames mud. The workmen engaged suggested that it was a sunken barge, but Mr. Dove realised from its position that it must be of considerable antiquity, and accordingly requested the Council’s official architect to have the soil carefully removed from above.”

Mr. Dove was right about the considerable antiquity of the find. When excavated, it was found to be a Roman boat, constructed out of carved oak. It was lying 19 feet, 6 inches below high water, and 21 feet 6 inches below the nearby Belvedere Road.

The size of the boat was about 38 feet in length, and 18 feet across.

Within the boat were found four bronze coins, in date ranging from A.D. 268 to 296, portions of leather footwear studded with iron nails, and a quantity of pottery. There were signs that the boat had been damaged as several rounded stones were found, one of which was embedded in the wood, and there was indication that some of the upper parts of the boat had been burnt.

After excavation, the boat was offered to the Trustees of the London Museum, who accepted, and the boat was removed from site, with the following photo showing the transport of the boat from the excavation site. It is within a wooden frame to provide some protection.

The boat was put on display in Stafford House, then the home of the London Museum. (Stafford House is now Lancaster House, in St. James, a short walk from Green Park station).

The following photo shows the boat on display:

I contacted the Museum of London to see if parts of the boat were available to view, and was told a sorry story of the limitations of preservation techniques for much of the 20th century.

The boat was found beneath the silt and Thames mud in an area of damp ground. This created an oxygen free environment which preserved the boat’s timber.

As soon as the boat was exposed, it started to dry out, and over the year the timbers cracked and disintegrated. Museum of London staff tried to patch up with fillers, but this was long before the chemical means of conservation that we have today were available.

When the Museum of London moved to its current site on London Wall, only a small section was displayed, and this was removed from display when the gallery was refurbished in the mid-1990s.

Some key features of the boat such as joints and main timbers have been preserved as well as they can be after so many years, and are stored in the Museum of London’s remote storage facility, so not available for public display.

The Museum of London did donate some of the fragments to the Shipwreck Museum in Hasting, so I got in contact with them to find out what remained.

I had a reply from the former City of London archaeologist, Peter Marsden, who advised that much of what was preserved at Lancaster House was modern plaster of paris painted black. He also confirmed that only some ribs and a few bits of the planks survive, and are no longer on display.

Peter Marsden has written some fascinating books on Ships of the Port of London. They are very hard to find, however the English Heritage Archaeology Data Service has the book “Ships of the Port of London, First to eleventh centuries AD” available to download as a PDF from here. It is a fascinating read which includes many more discoveries in the Port of London as well as the County Hall Roman boat.

The age of the boat seems to be around 300 AD which is confirmed by the coins discovered in the boat all being earlier, and Peter Marsden managed to get a tree ring date of around 300 AD from one of the planks.

It is difficult to confirm exactly why the boat was lost on the future site of County Hall. There was much speculation at the time, including in the County Hall booklet, that the boat had been lost during battles in AD 297. The burning on parts of the wood written about in the booklet has not been confirmed, and the stones could have been ballast.

It seems more likely that the boat may have been damaged, or simply lost on what was the marshy Thames foreshore and land of the south bank. Away from the City of London, the boat was left to rot, gradually being covered by the preserving mud and silt of the river until discovery in 1910.

There is another feature on the plan of the new County Hall that suggests the boat could have been on the edge of the Thames foreshore.

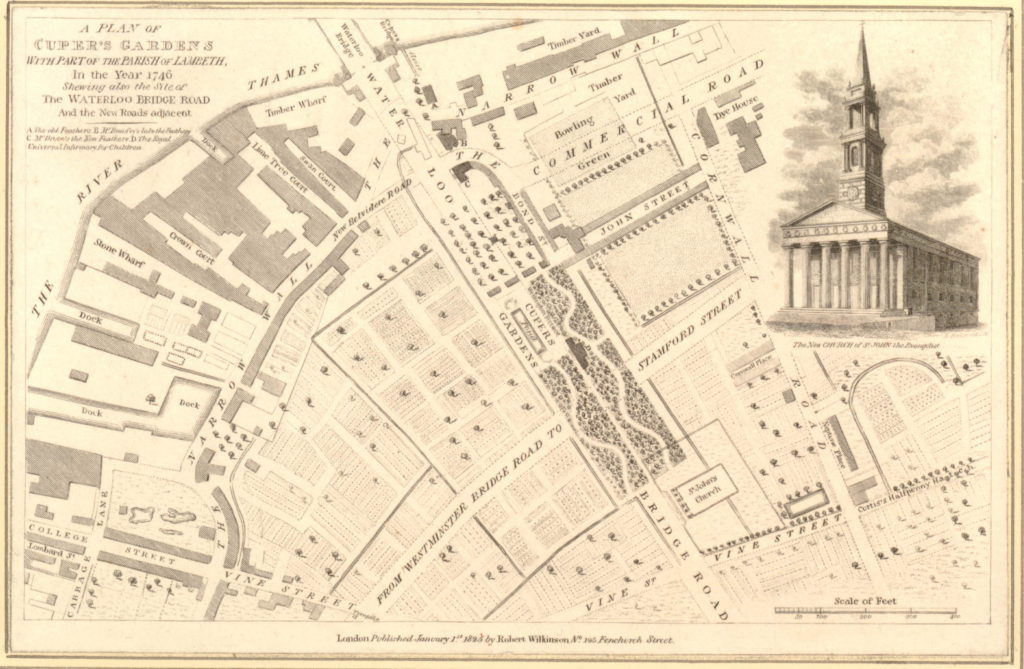

On the opposite side of County Hall to the river is a street called Belvedere Road. This was originally called Narrow Wall. The first written references to the name Narrow Wall date back to the fifteenth century, and it could be much older. The name refers to a form of earthen wall or walkway, possibly built to prevent the river coming too far in land, and as a means of walking along the edge of the river.

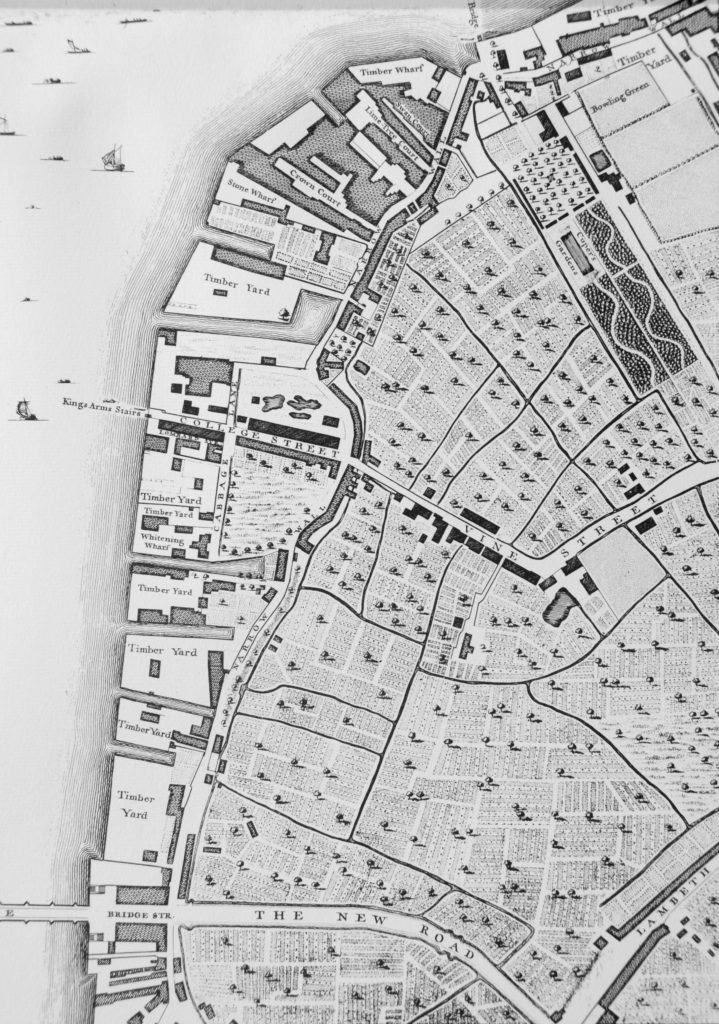

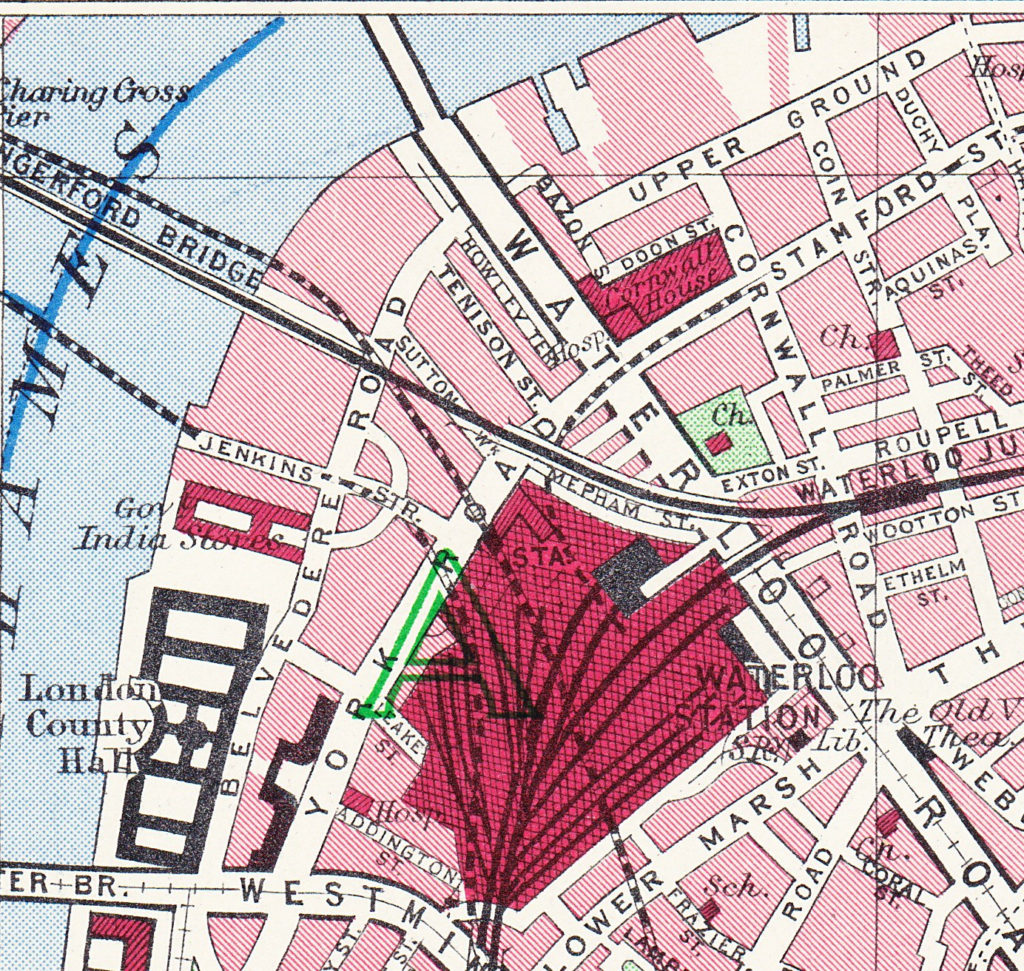

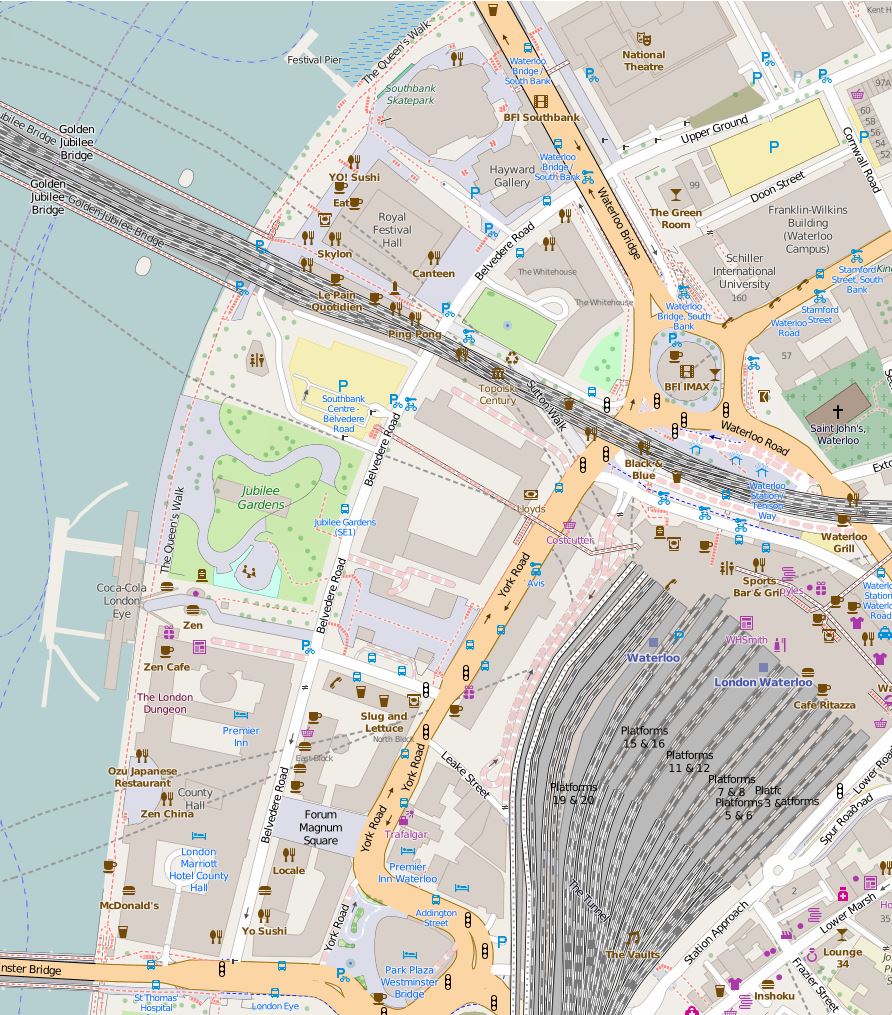

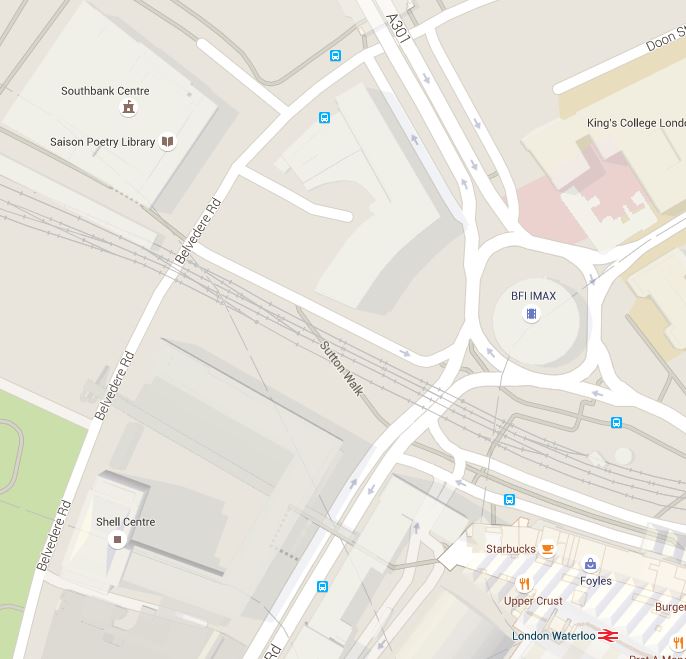

In the following extract from John Rocque’s 1746 map of London, Westminster Bridge is at the lower left corner, and slightly further to the right, Narrow Wall can be seen running north.

Although straightened out and widened, Belvedere Road follows the approximate route of Narrow Wall.

If Narrow Wall was built along a line that formed a boundary between river and the land, then the Roman boat was close to this and would have been in the shallow part of the reed beds that probably formed the foreshore.

I have annotated the original plan from the booklet with some of the key features, including the location of the Roman boat:

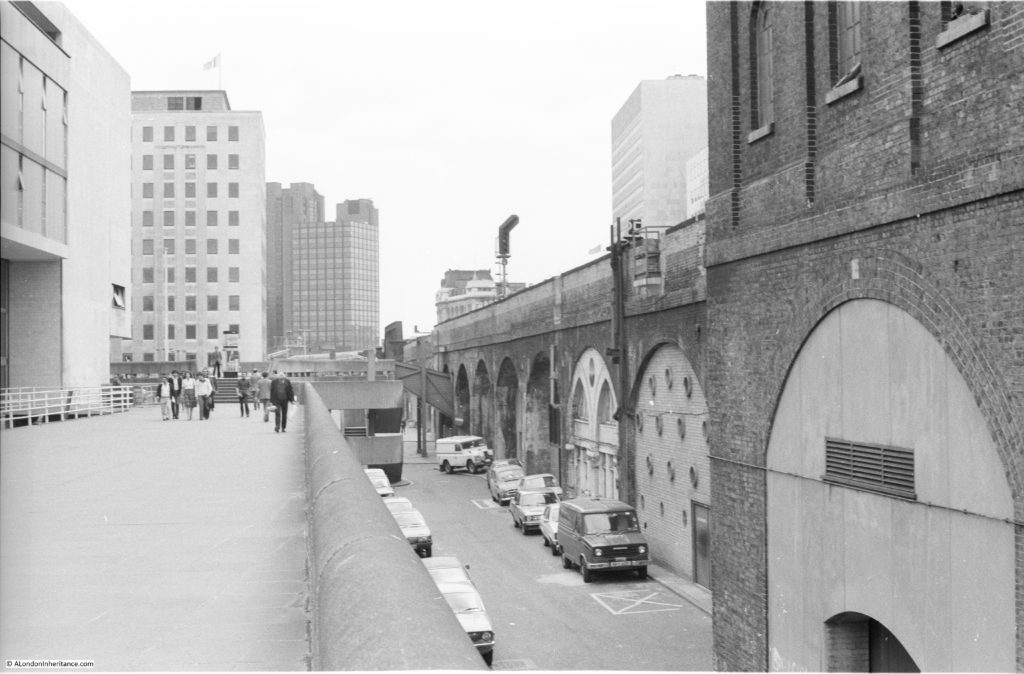

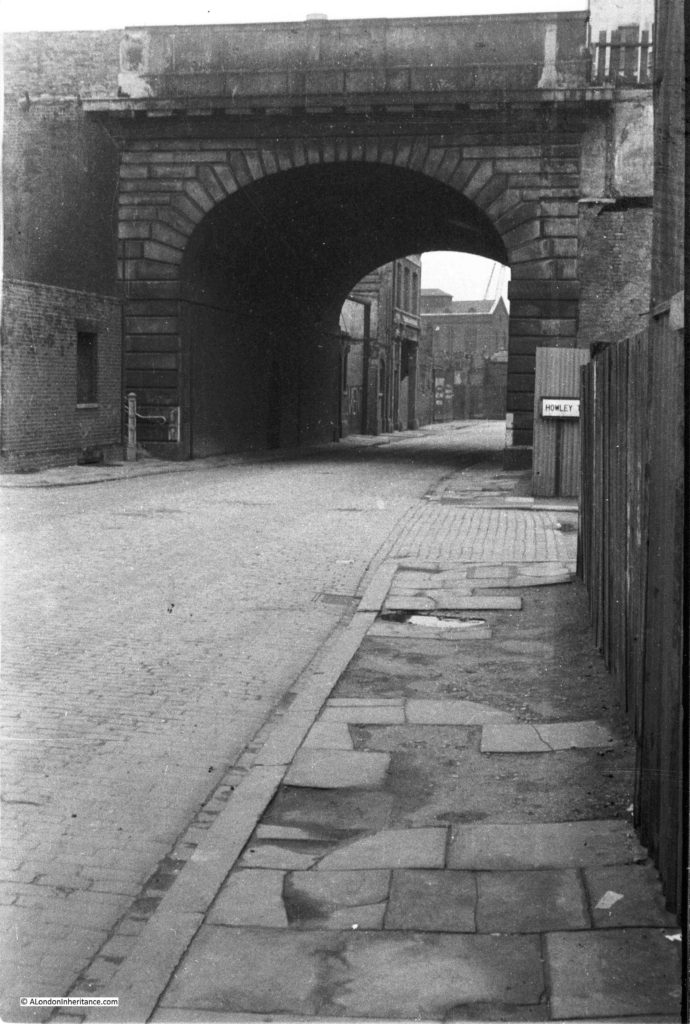

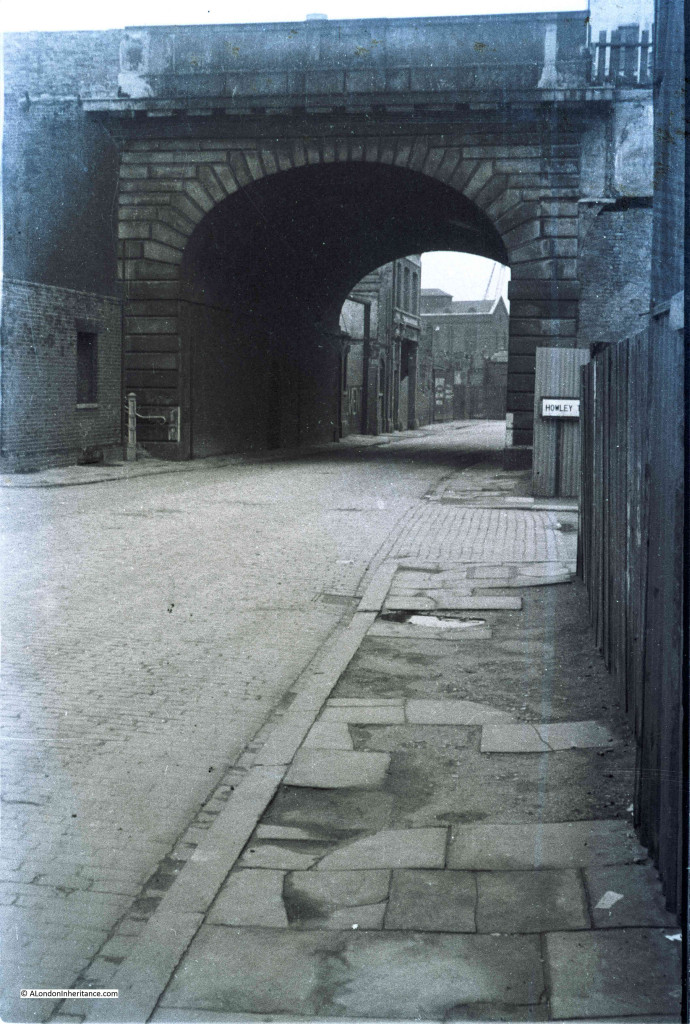

The following view is looking along Belvedere Road / Narrow Wall, with County Hall to the left:

The following photo is a view of the entrance to County Hall from Belvedere Road. The Roman boat was found just behind the doors to the left:

There is a curious link between the finding of the Roman boat and the laying of the foundation stone commemorated by the booklet.

The foundation stone was laid on Saturday the 9th of March 1912 by King George V. Underneath the foundation station was a bronze box, the purpose of which was described in newspaper reports of the ceremony:

“Depositing a ‘find’ for some archaeologist of the future, the King and Queen watching the foundation stone of the new London County Hall being lowered into position. Before the stone was lowered into position and declared by the King to be well and truly laid, his Majesty closed a bronze box containing certain current coins and documents recording the proceeding, and caused it to be placed in a receptacle in the stone. Perhaps at some dim future day, when London ‘is one with Nineveh and Tyre’ this box and its contents will come to light beneath the spade of an excavator, burrowing amid the ruins of a forgotten civilisation.”

So having been the site of excavation of a Roman boat, the hope was that the bronze box would form an archeological discovery in some distant future.

I assume the bronze box is still there, below the foundation stone, in the north-east lobby adjacent to the old Council Chamber.

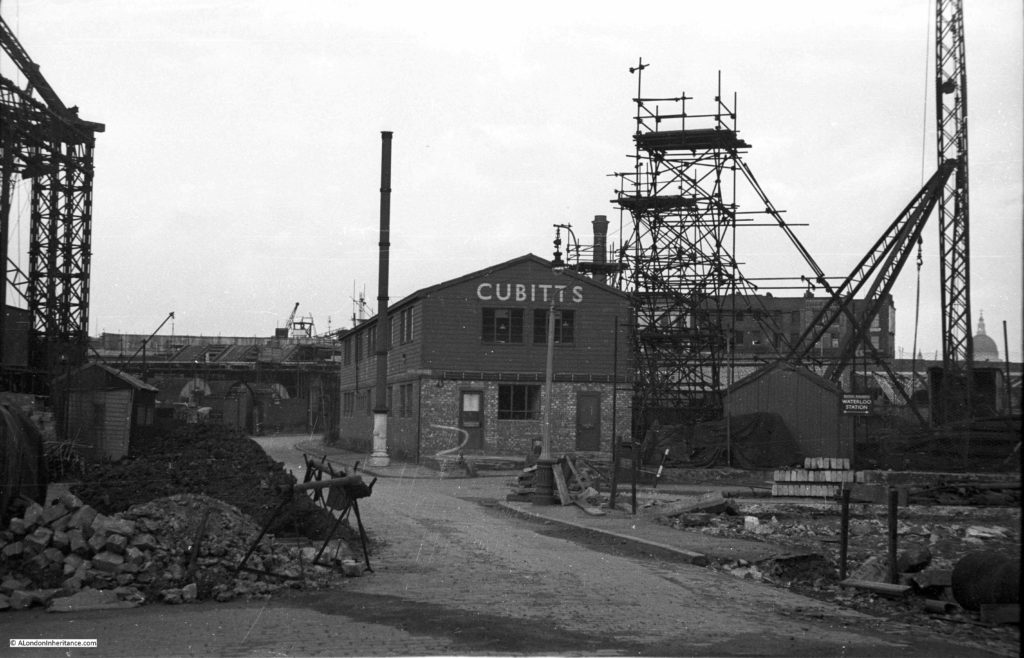

Construction of County Hall continued slowly. It was a large building requiring large numbers of workmen and materials.

The coal and dock strikes of 1912 and building workers strike of 1914 delayed construction. Work continued during the First World War, however war demands such as on the rail network caused problems with the transport of granite from Cornwall to London.

As parts of the building became useable, they were taken over by rapidly growing Government departments such as the Ministry of Munitions and Ministry of Food, who were able to prioritorise their needs over the LCC due to the demands of war.

By the end of September 1919, the LCC were able to retake possession of the building, and work on completion continued quickly, with over one thousand men working on the site by March 1921.

The building was soon substantially complete, was gradually being taken over by an ever expanding LCC staff, and was officially opened in July 1922.

The London County Council continued until the 1st April 1965. The London Government Act of 1963 restructured how London was governed, and this led to the Greater London Council (GLC) which took over from the LCC.

The GLC lasted to the 31st of March, 1986 when it was abolished by the 1985 Local Government Act, primarily down to conflict between the Labour held GLC and the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher across the river.

The building was sold to the Shirayama Shokusan Corporation, a private Japanese company, for £60 million. and in the following years it would be converted to a hotel and the ground floor facing the embankment walkway hosts tourist destinations such as Shrek’s World of Adventure, a Sealife Centre and the ticket offices for the London Eye.

County Hall is Grade II listed, and the original Council Chamber of the LCC has been preserved, and is now available to hire and is used as a theatre.

The architect Ralph Knott worked on County Hall for most of his career. He had been called up into the Royal Air Force during the First World War where he was responsible for the design of airfield buildings, but he still kept in touch with County Hall construction. He returned to the County Hall project after the war to see the main building through to completion.

He was still working on plans for extension of the building late in his career, which were not finished at the time of his death at the young age of 50 on the 25th of January 1929.

County Hall is a fitting tribute to Ralph Knott. A relatively simple, but grand and imposing building facing onto the river, suitable for an institution that was to have so much impact on the 20th century development of London. A building of contrasting design to the Palace of Westminster on the opposite bank of the river.

Sad that the Roman boat has been substantially lost. Preservation of organic remains that have been in waterlogged soil for centuries is difficult, but thankfully now much better, as seen for example, with the preservation of the Mary Rose in Portsmouth.

I hope that no readers comment that the bronze box beneath the foundation stone has been removed. It would be great that it is still there for archaeologists in the distant future to dig up.