Following the walk round the Upstream Circuit of the Festival of Britain on the South Bank, in this post I will take a walk round the Downstream Circuit – The People, however first a couple of other aspects of the festival.

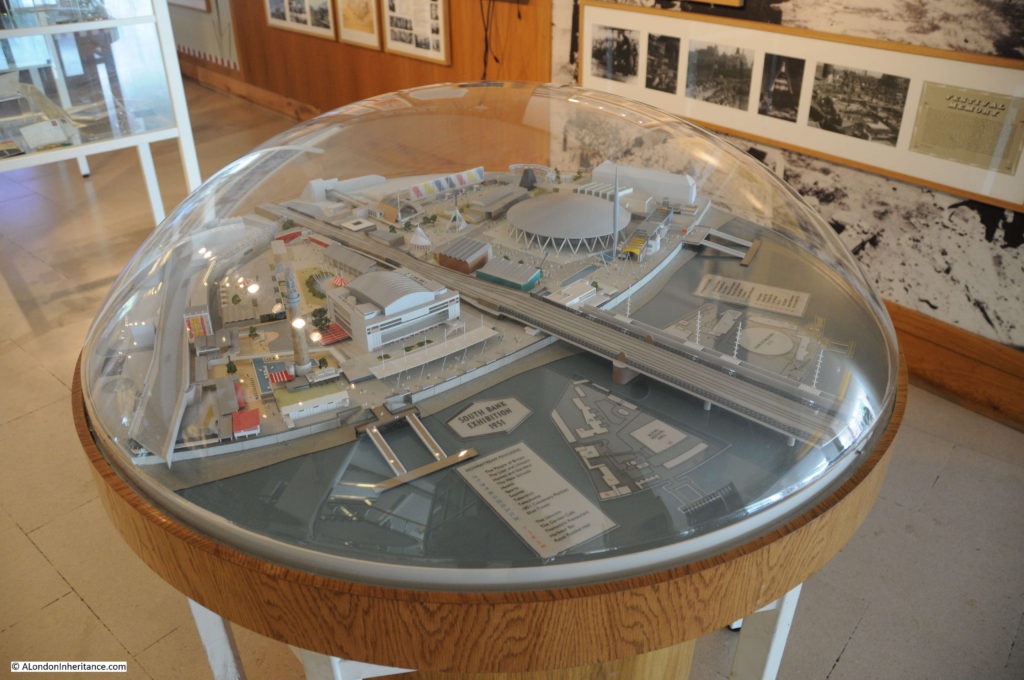

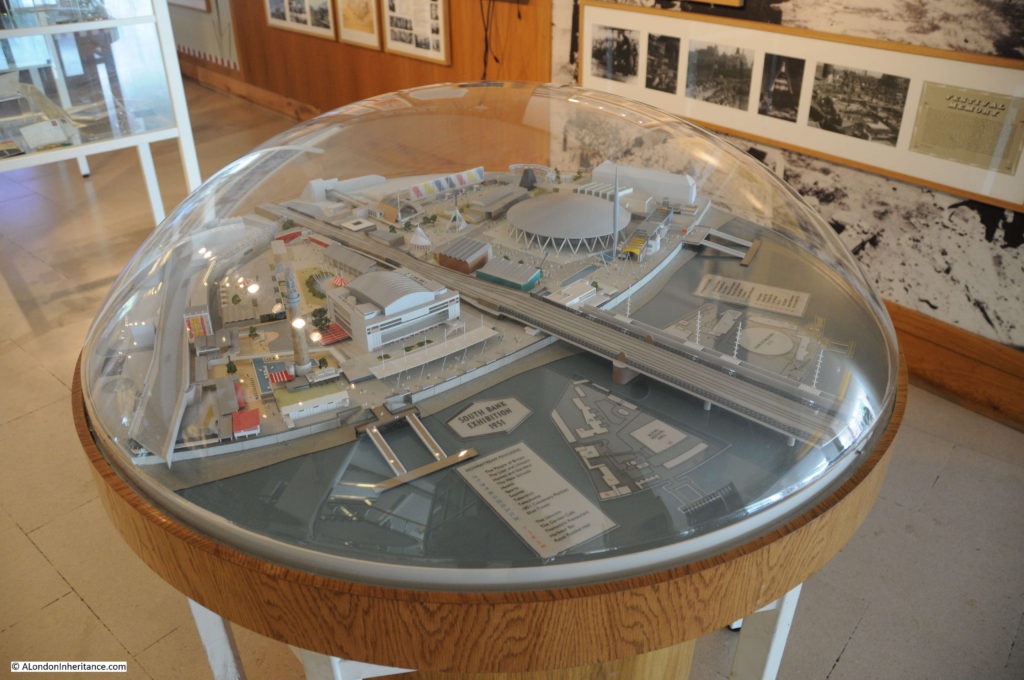

There is a small display in the Royal Festival Hall covering the Festival of Britain. This display includes a superb model of the overall festival site showing all the major landmarks of the festival, pavilions and Thames piers. If you visit the Royal Festival Hall, please do take a look.

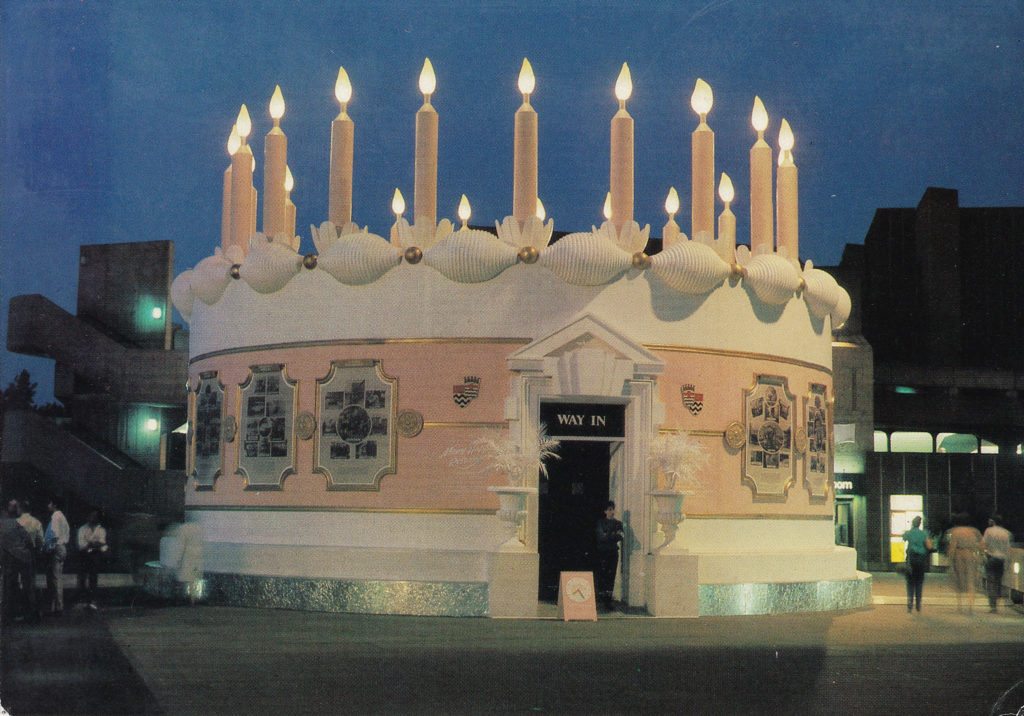

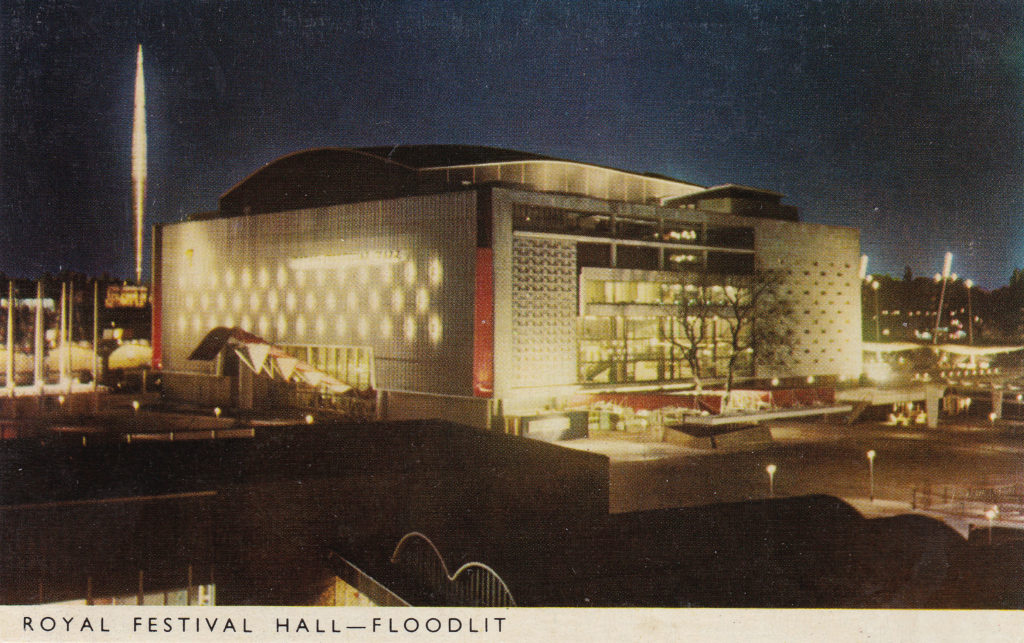

The Festival At Night

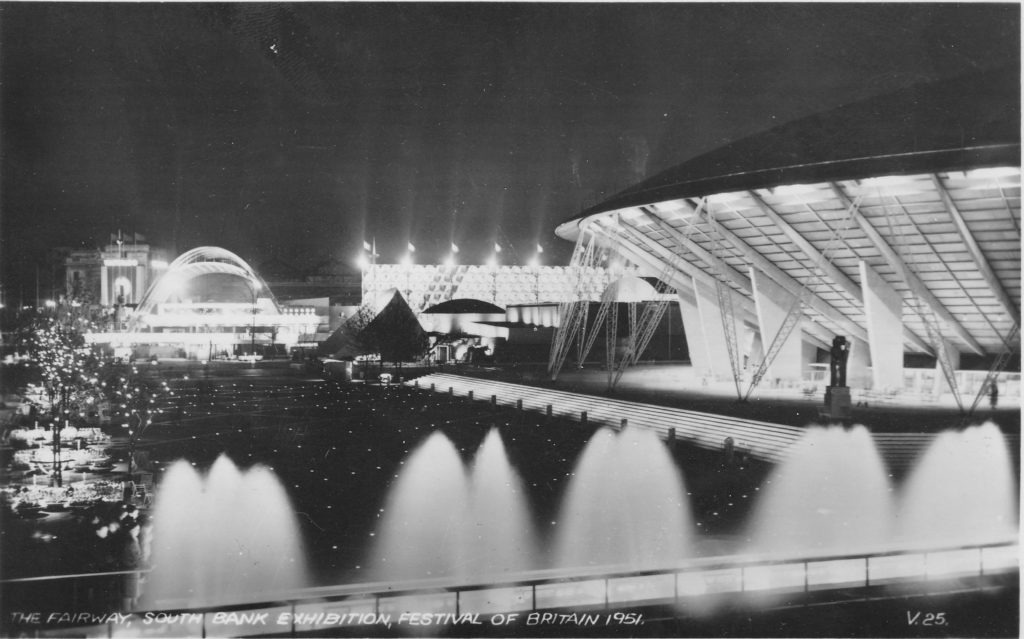

I mentioned in my last post on the use of colour across the festival site after long years of war and austerity. As well as colour, the festival was very brightly lit after dark, which again was a major attraction for visitors given that nothing had been this brightly lit for many years.

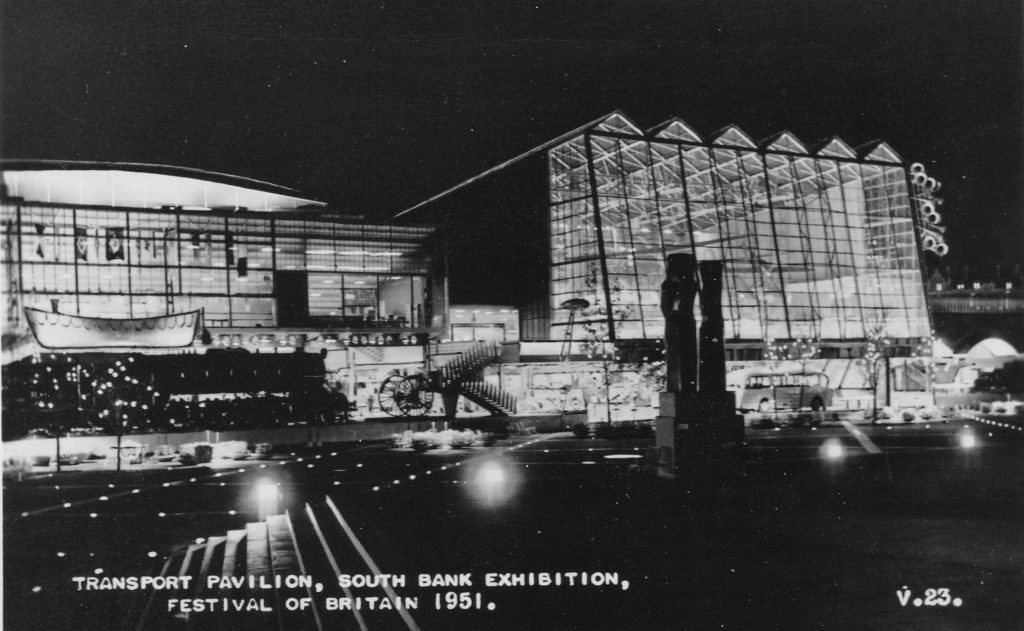

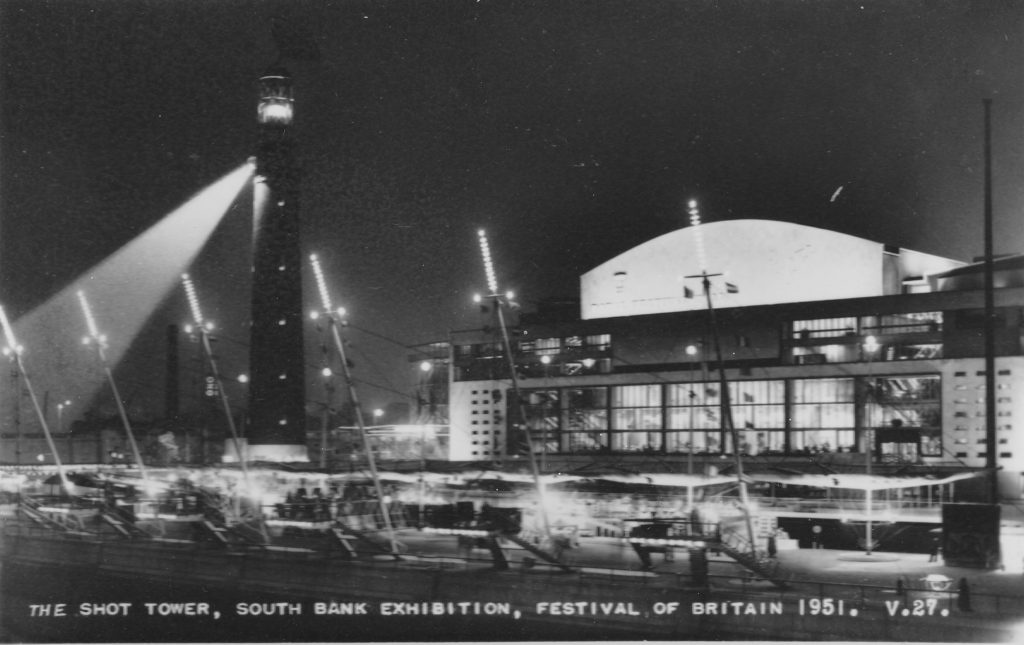

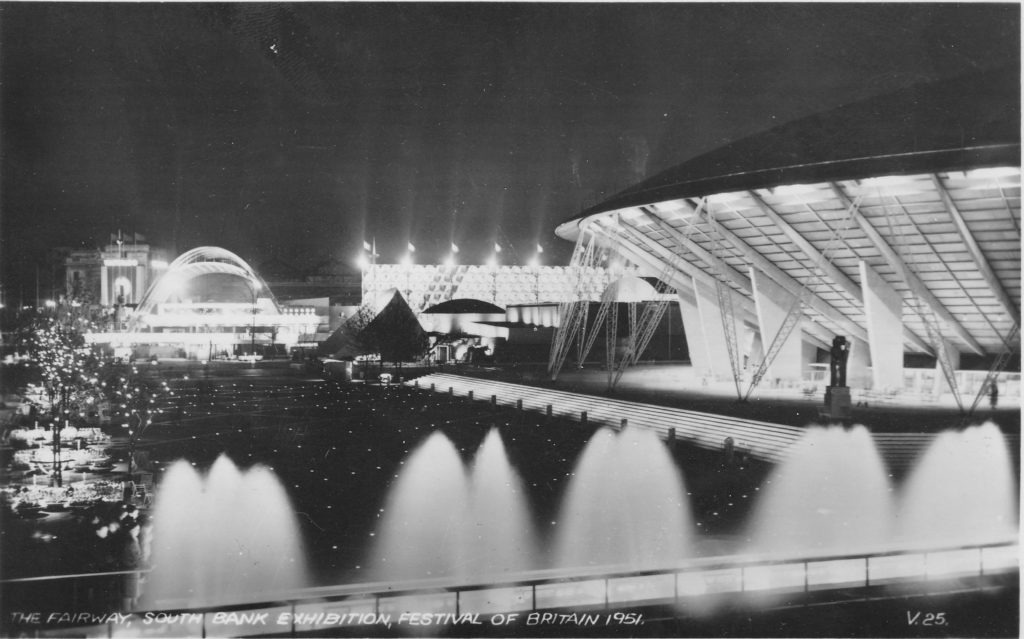

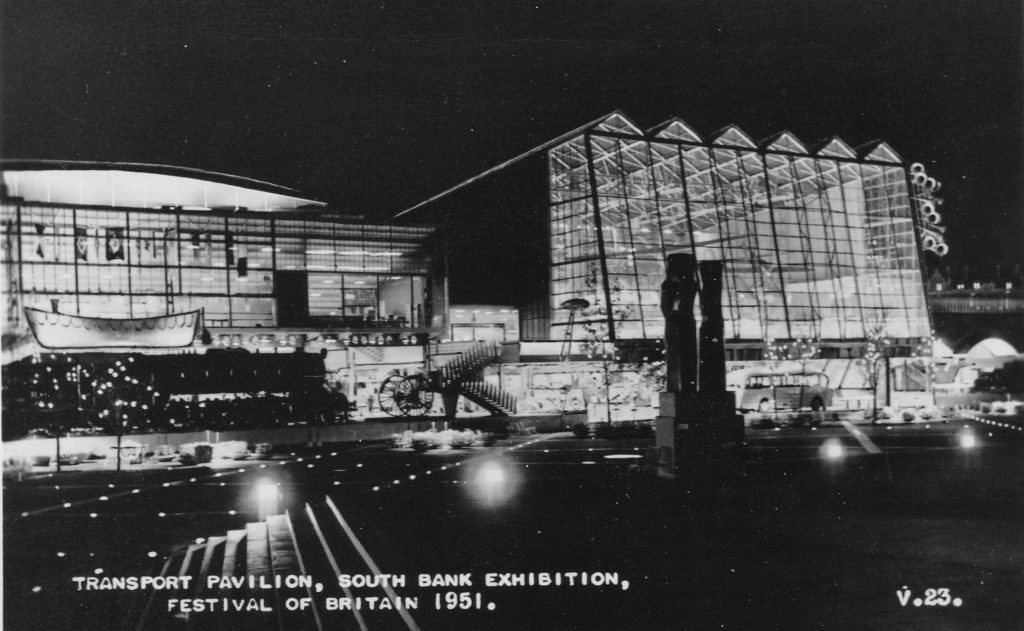

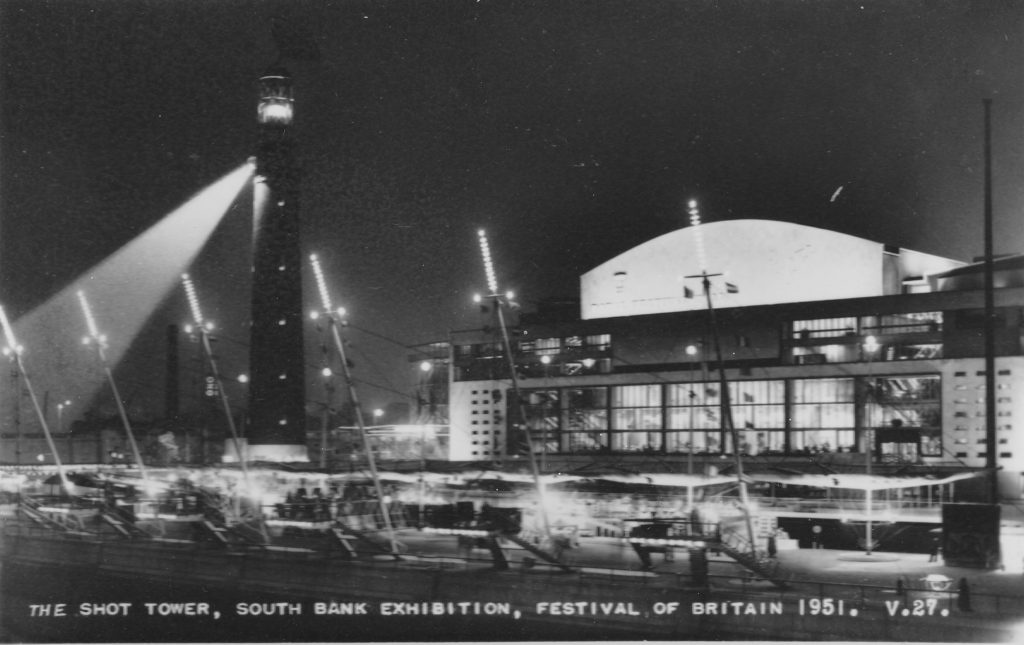

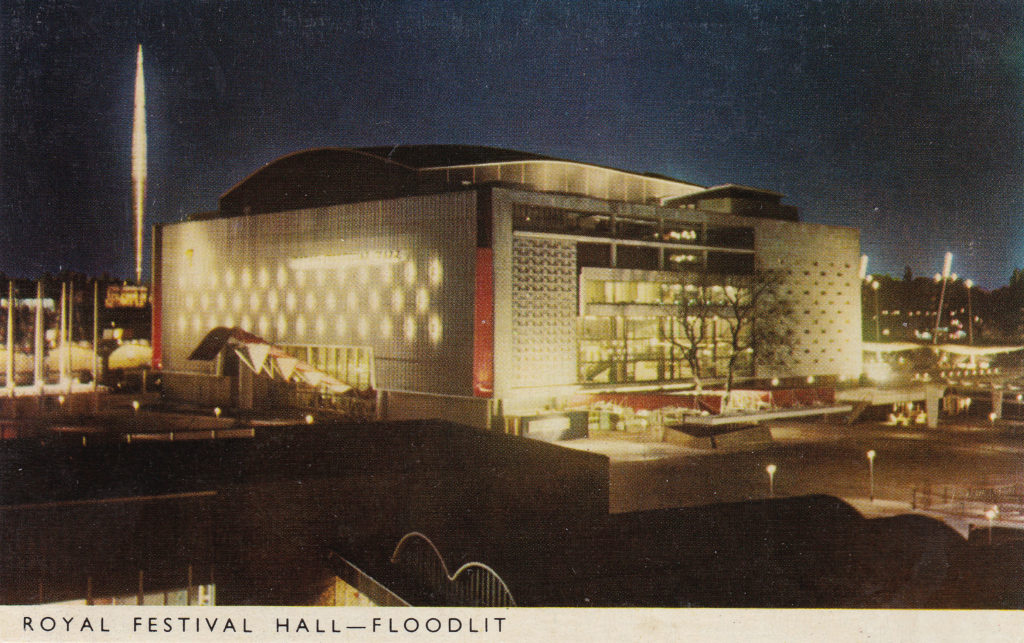

The following photos show how good the South Bank site must have looked after dark.

The first photo is looking towards the Station Gate from the embankment. On the left, the side of Waterloo Station is lit, then the arches over the Station Gate entrance, followed by the screen which separated York Road from the festival site, then the Dome of Discovery. In the foreground are the Fairway Fountains.

This photo is looking at the Transport Pavilion.

From the north bank of the river looking across to the festival site. The brightly lit Skylon is in the centre of the photo, Royal Festival Hall to the left followed by the Shot Tower.

The Royal Festival Hall and the Shot Tower.

A colour view of the Royal Festival Hall with the Skylon in the background.

It was not just the South Bank site that was illuminated. Surrounding buildings were as well, as this photo shows, with floodlit buildings along the north bank of the river, including the Houses of Parliament.

As well as the information and products displayed in each of the pavilions, the use of colour and lighting during the Festival of Britain after so many years of war, austerity and rationing aimed to inspire visitors to the festival with optimism and that there was a much better future ahead for the people of Great Britain.

A Walk Round The Downstream Circuit – The People

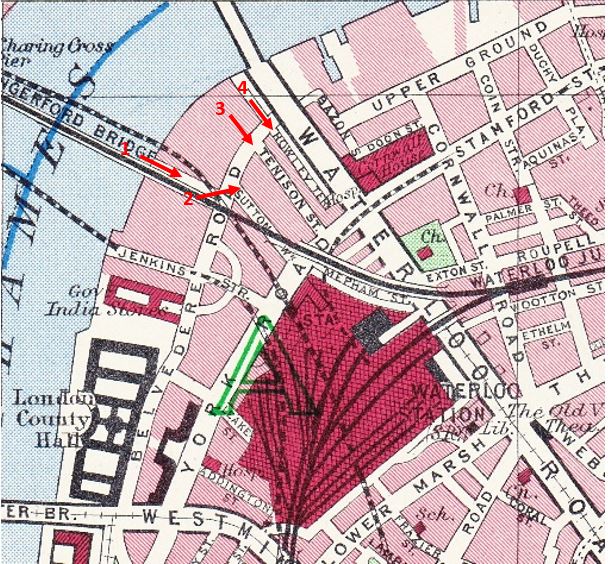

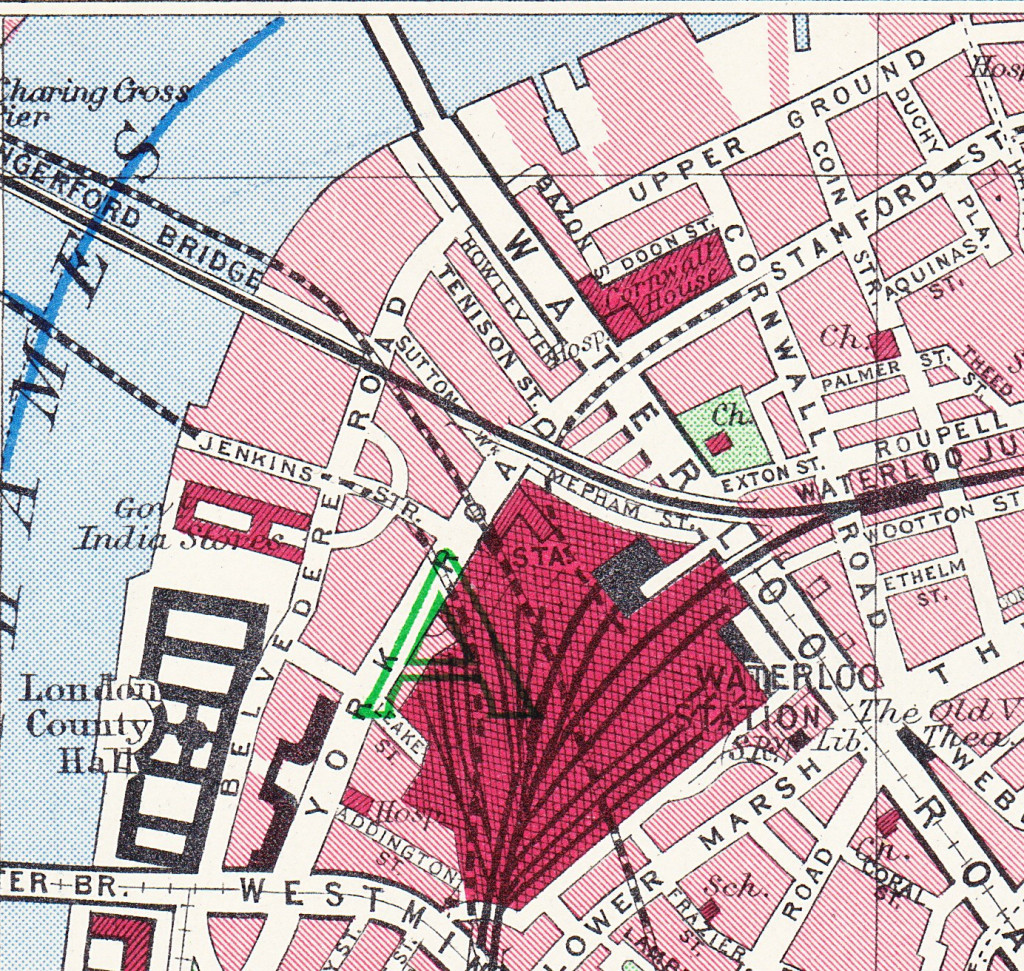

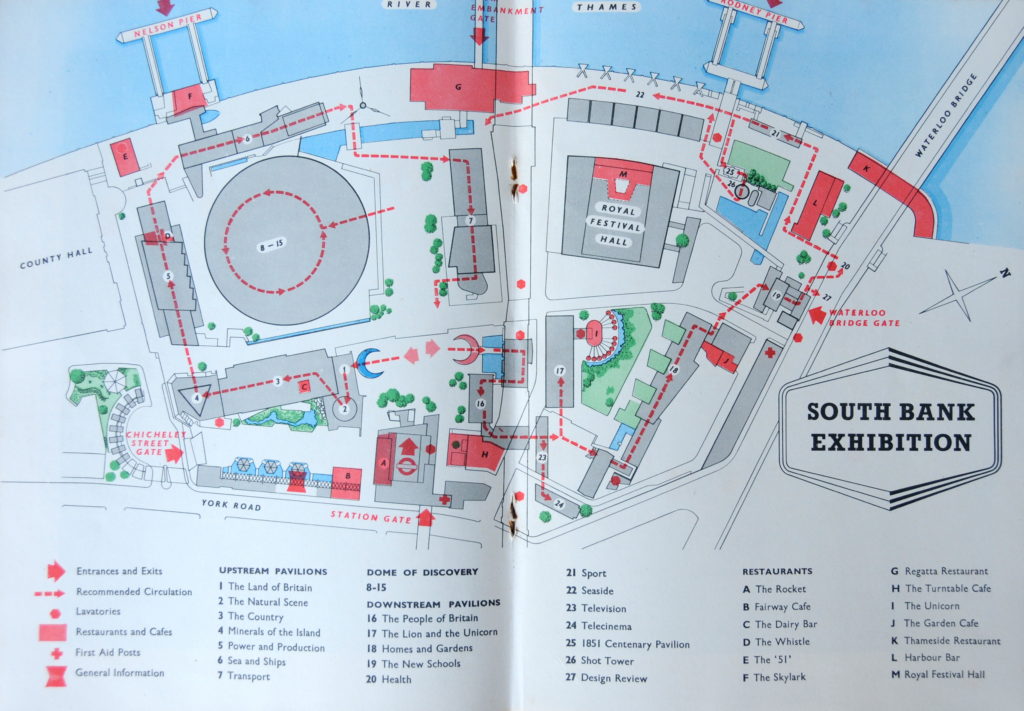

The Upstream Circuit told the story of the Land of Britain and in this post we will walk round the Downstream Circuit which occupied the space between Hungerford and Waterloo Bridges and told the story of The People.

Firstly, a couple of views of the Downstream Circuit from Waterloo Bridge. The first shows the Royal Festival Hall and Shot Tower. On the river is the Rodney Pier, named after the British naval officer Admiral Rodney who served in the Royal Navy and was involved with many battles against the Spanish, French and during the American War of Independence. There was a second pier on the Upstream Circuit named the Nelson Pier. These two piers allowed boats and their passengers arriving from along the Thames to access the festival and also shuttle services to two of the other main London events. A shuttle service ran to Battersea for the Festival Pleasure Gardens and a second shuttle service ran to the West India Dock where a special bus service would take visitors to the Architecture Exhibition at Poplar.

A view of the Downstream Circuit close to the river bank showing the cluster of pavilions, cafes and event spaces around the Shot Tower.

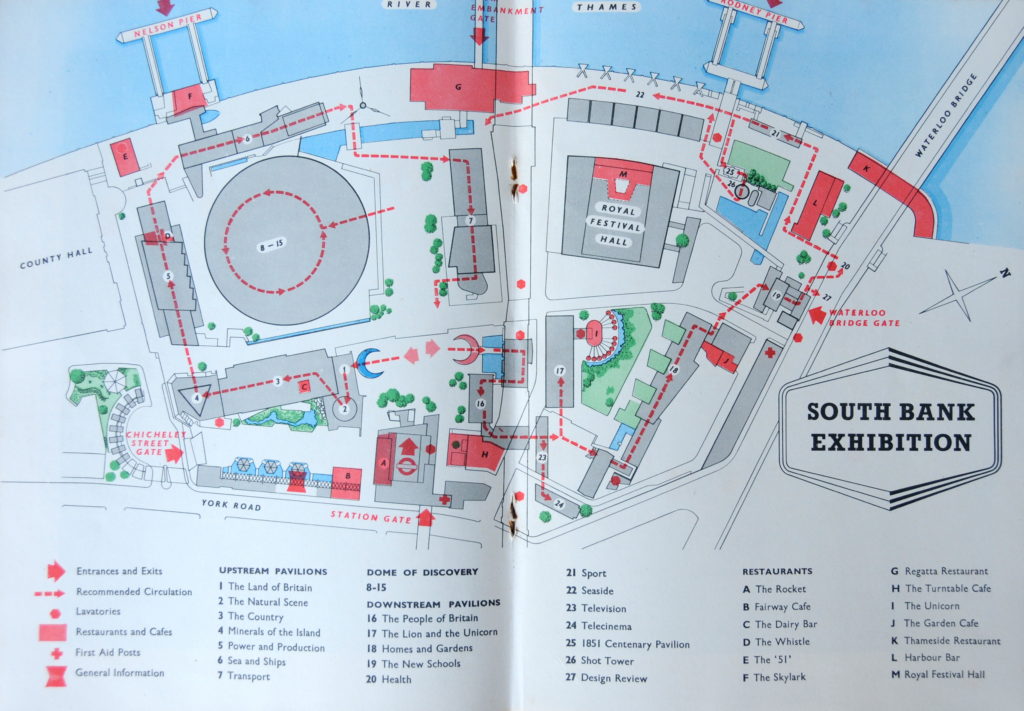

Here again is the map of the South Bank Exhibition.

The first pavilion in the Downstream Circuit is number 16 – The People of Britain. The guide-book stated that the pavilion will answer the following questions:

“The story that has been told so far shows that, in achievement, the British are a nation of many different parts. In appearance, too, they are just as mixed – certainly one of the most-mixed people in the world. But who are these British people? What different breeds of ancestors have contributed to the shaping of such a rare miscellany of faces as confronts the visitor in any London bus? Where did those various ancestors come from? And how did they reach this land?”

The pavilion told the story of the first islanders from the stone and bronze ages, the Celts then came from Northern France and gave a fresh impulse to the development of agriculture across the country. Then came the Romans who gave the Britons “a first taste of a civilisation”. This was followed by Christianity, then the Norse and Danish Vikings and finally the Normans – the last invaders.

The long history of arrivals to the country from the earliest settlers to the Normans were all absorbed into the life that was here before them and each wave of settlers became islanders. As I discussed in the post on the background to the festival, the story of immigration and settlement in Britain from the perspective of the festival ended with the Normans and later immigration or migration from the Commonwealth was not included in the story of the British people.

Leaving The People of Britain pavilion, we head to pavilion 17 – The Lion and the Unicorn.

The Lion and the Unicorn Pavilion was on the space now occupied by the Whitehouse apartments. I could not get to the exact position as the above photo as the Whitehouse buildings now occupy the site, however in the photo below, the Lion and the Unicorn pavilion occupies the space to the right.

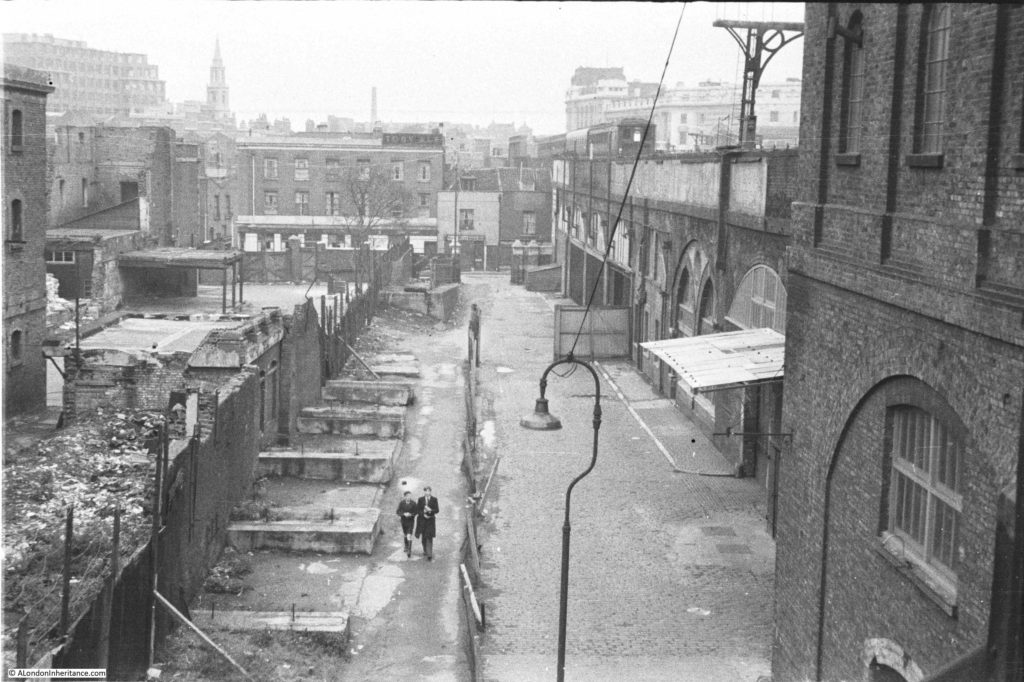

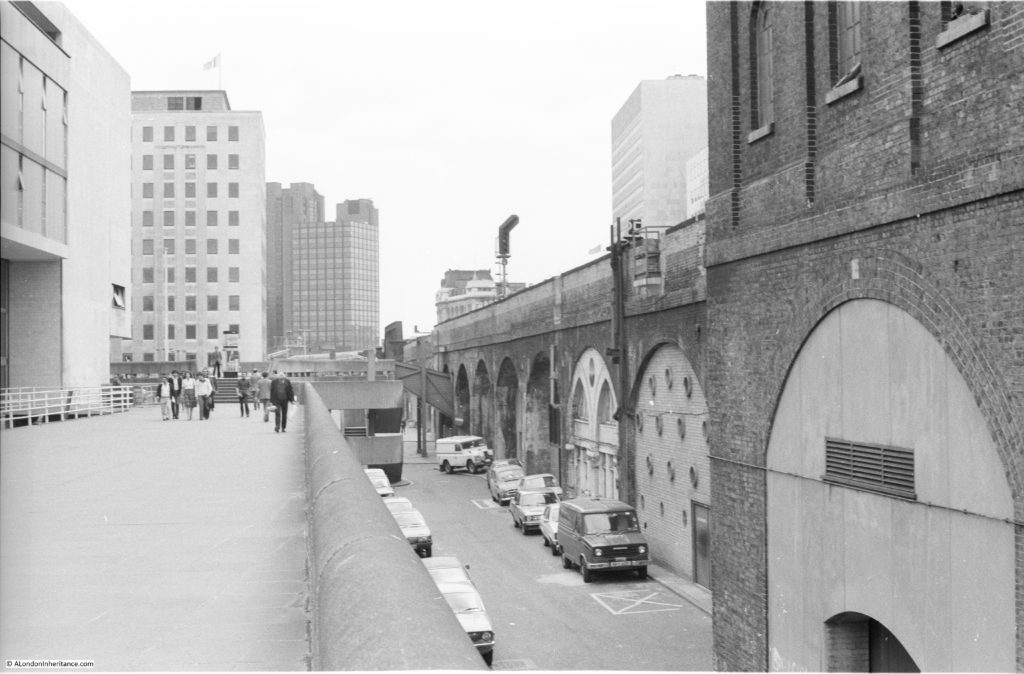

A colour photo from the time of the festival looking along Belvedere Road. The Lion and the Unicorn Pavilion is the building on the left, between the large tent and the railway viaduct.

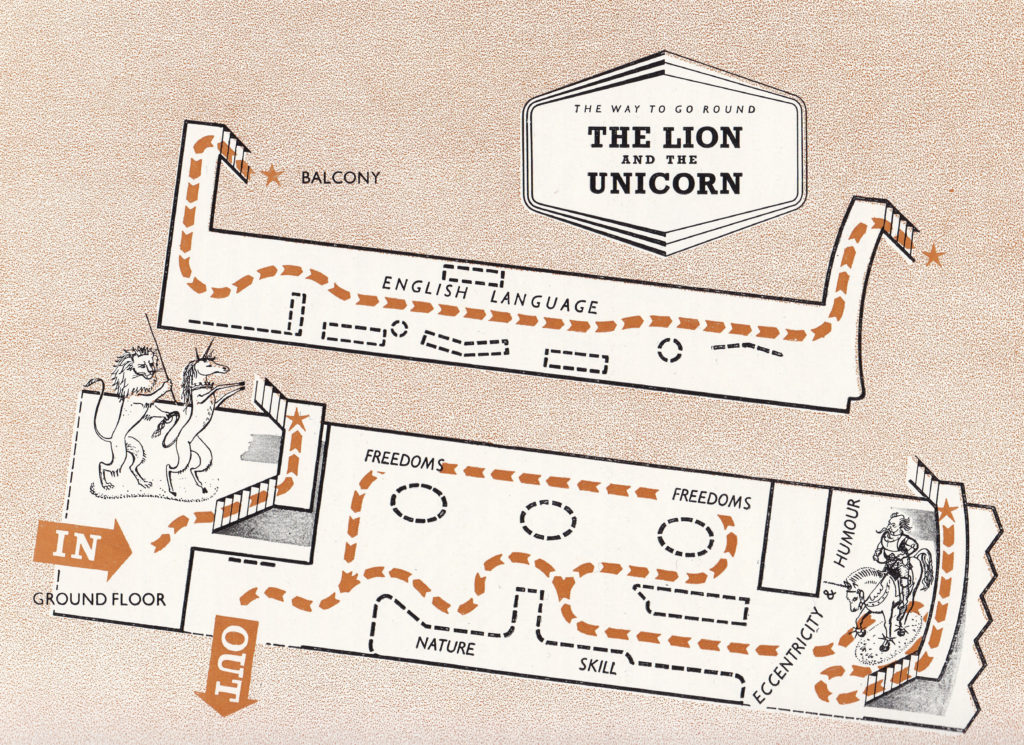

As discussed in my post on the background to the festival, the Lion and the Unicorn Pavilion attempted to show and explain the British character to the visitor with the Lion and the Unicorn symbolising two of the main qualities of the national character: “on the one hand realism and strength; on the other fantasy, independence and imagination“.

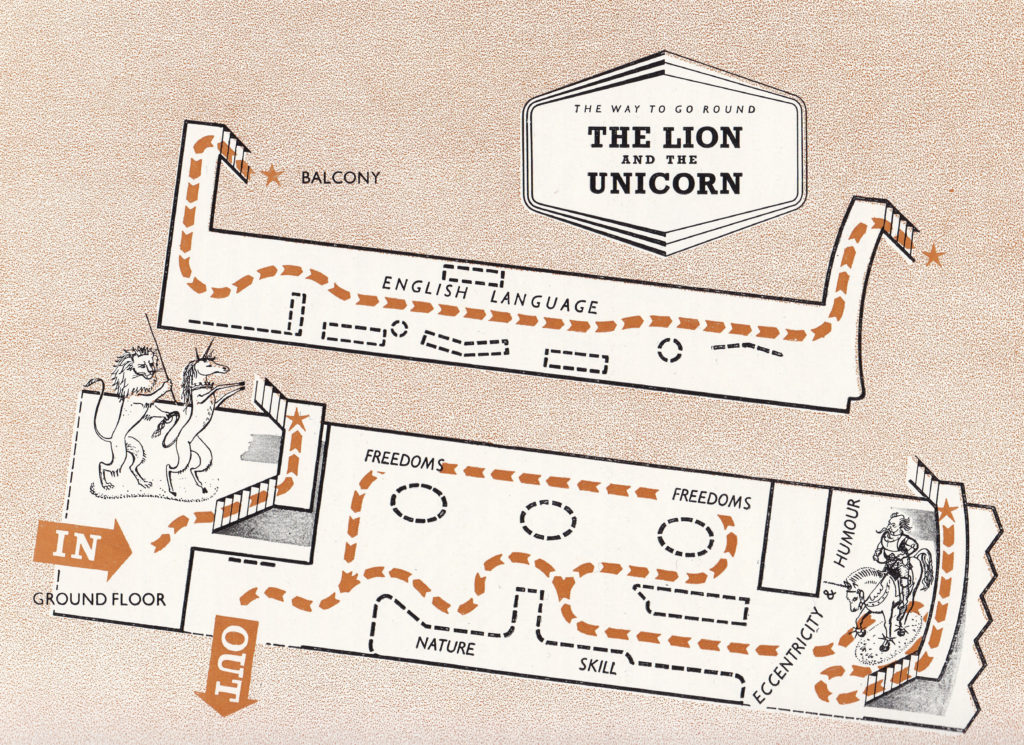

The following plan shows the pavilion and the main sections.

The main characteristics of the British people covered in the pavilion were, Language and Literature, Eccentricities and Humours, Skill of Hand and Eye and the Instinct of Liberty.

On entering the pavilion, the visitor would see high on a side wall, very large straw figures of the Lion and Unicorn set in front of the legend “We are the Lion and the Unicorn, twin symbols of the Briton’s character. As a Lion I give him solidarity and strength. With the Unicorn he lets himself go“.

The large straw figures were created by Fred Mizen who lived in Great Bardfield in Essex who was an agricultural worker and specialist in thatching and straw work. To illustrate the character of the Unicorn, he was holding a rope which led up to a giant birdcage hanging from the roof of the pavilion. The rope had opened the door of the birdcage allowing a flight of plaster doves to escape and were shown suspended in flight along the length of the pavilion roof.

The pavilion included exhibits such as the Oxford Lectern Bible displayed on a fifteenth century church lectern, scale models of sets for Shakespeare’s plays, portraits of British authors, recordings of local speech from across the country showing how there was much diversity in the spoken word.

There were a number of murals used in the pavilion. The photo below shows part of the interior of the Lion and the Unicorn Pavilion and to the lower left is a large mural along the wall. The mural was painted by Kenneth Rowntree and titled “The Freedoms”. The mural used a number of scenes from history to highlight the British concept and struggle for freedom including the Tolpuddle Martyrs, Emmeline Pankhurst and the fight for woman’s suffrage.

If you look to the left of the mural, you can see part of an aeroplane wing marked G-APXL which was a divider between the British scenes and a couple of panels on the “British colonies”, which may have been added as an afterthought, with the message that Britain had freed the countries of the Commonwealth by giving them better living conditions. Again, one of the very few references to the Commonwealth with a message that does not fit well with the current view of Empire and Commonwealth.

The guide-book acknowledges the challenge of explaining the British Character. The closing paragraphs for the pavilion read:

If, on leaving this Pavilion, the visitor from overseas concludes that he is still not much the wiser about the British national character, it might console him to know that British people are themselves still very much in the dark about it. For them, the British character is as easy to identify, and as difficult to define, as a British nonsense rhyme.

The lion and the unicorn

Were fighting for the crown;

The lion beat the unicorn

All round the town.

Some gave them white bread

And some gave them brown;

Some gave them plum cake

And sent them out of town.

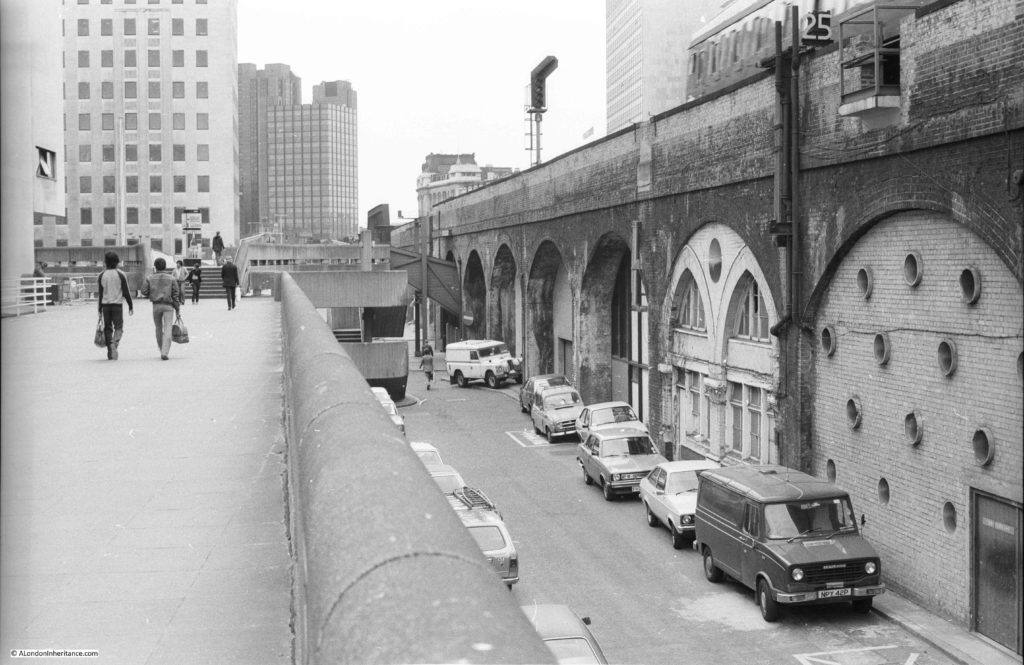

We can now leave the Lion and Unicorn Pavilion and walk across to the Homes and Gardens Pavilion. As you walk across, the view down towards the Royal Festival Hall is shown in the following photo:

Just before entering the Pavilion (the entrance doors can be seen to the right) we have this view:

The guide-book introduction to the Homes and Gardens Pavilion states:

“Fifty million people live on a slice of land which covers an area of less than a hundred thousand square miles – smaller than New Zealand where less than two million people live. Eighty per cent of those people have their homes in towns where the demand for space is clamorous. The great task lies, then, in planning the towns and the houses as a whole. This subject is covered in the Festival Exhibition of Architecture at Poplar. Here on the South Bank, our concern is with some of the units within the house itself; and in the Pavilion a picture is presented of contemporary living created by and for the British family of to-day”.

The aim of the pavilion was to show how British design had addressed the needs of the British family of 1951. Six rooms were chosen and a team of designers selected for each of the rooms. The route through the pavilion took the visitor to each room in turn where they could see how each team of designers addressed the function of each room and the types of products that the consumer could expect to purchase in the future to use within and decorate each room.

The rooms chosen for display were:

- The child in the home

- The bed-sitting room

- The kitchen

- Hobbies and the home

- Home entertainment

- The parlour

The description of the parlour shows how change was taking place in the home in 1951:

“The parlour has long-lost its original meaning as a place where people could sit and converse. Today the very word has a frowsty sound. Yet, quite often, when architects have provided a family with a larger living-room instead of a parlour, one corner has been turned nostalgically into a token parlour-substitute. It is evident, then, that many people still feel the need for a room apart, where photographs and souvenirs can contribute memories, and where the fireplace can be treated as an altar to house-hold gods. So the designers have shown how such a need can be met, in twentieth-century style and without any trace of frowstiness”.

Leaving the Homes and Gardens Pavilion, if we run up to Waterloo Bridge and look over the area we would get the following view. There is another of the festival cafes at lower right, here the Garden Cafe. Again see the use of colour across the site.

The next pavilion, number 19 is the New Schools Pavilion and is shown in the following photo:

Significant changes were taking place in education after the war. The 1944 Education Act empowered local education authorities to provide education for every child in the country between the ages of five and fifteen. The act brought in a three stream system of schools with grammar schools, secondary technical schools and secondary modern school, along with the comprehensive school system which would combine the three separate streams.

The 1944 Education Act also required local education authorities to provide school meals and milk.

The New Schools Pavilion provided the visitor with a view of what the future school would look like and how it would be equipped. Class room settings, school furniture, laboratories were all on show within the pavilion along with presentations on how the education system would work and the type of teaching children would experience.

The New Schools Pavilion was an example of where the Conservative Party saw the festival as a display of Labour party policies. Despite there being no references to politics throughout the festival there was a concern that the visitor may associate the positive view of future schools with the government of the time.

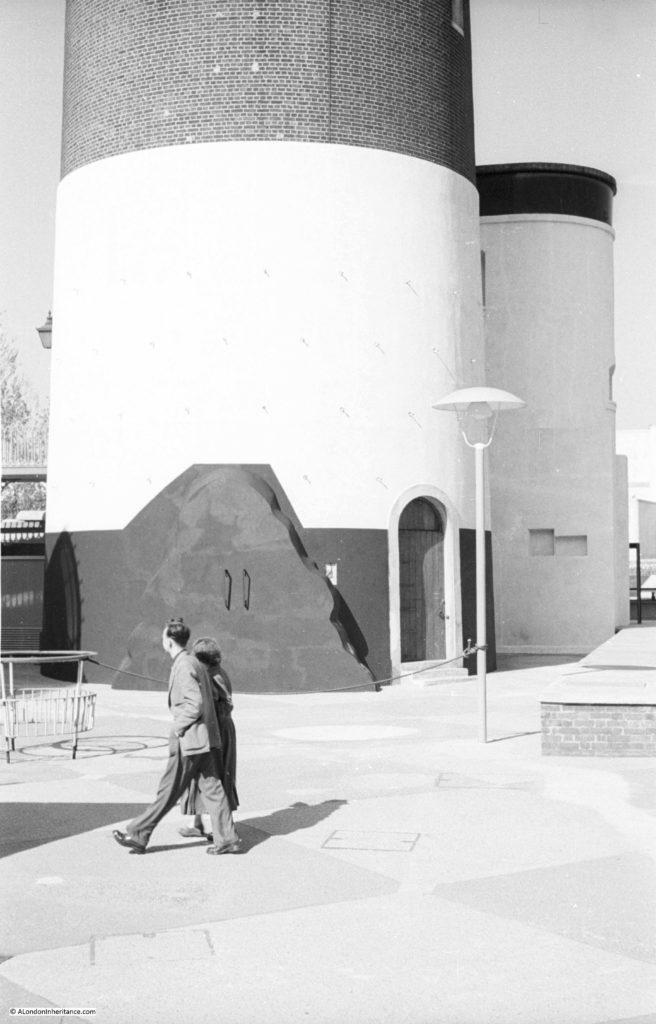

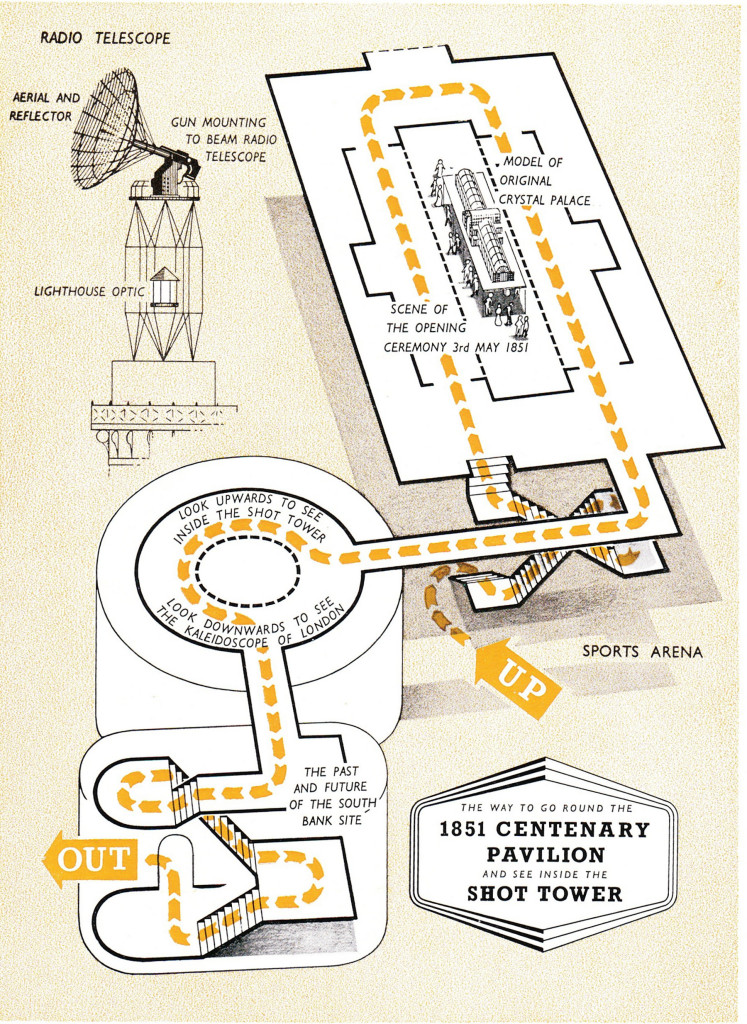

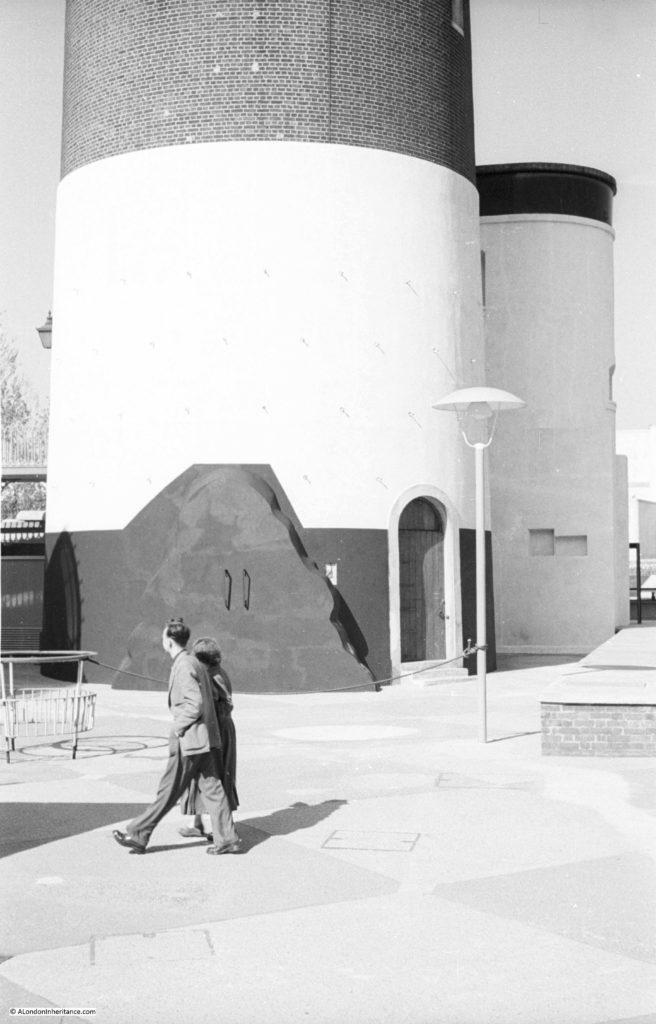

The following photo shows the edge of the New Schools Pavilion and the full height of the Shot Tower with the radio antennae mounted on the top.

The mount for the antenna was an old anti-aircraft gun with the antenna dish mounted along the line of the gun barrel.

Installing the anti-aircraft gun at the top of the tower was not without problems and it was only at the second attempt that the gun was successfully installed. At the first attempt, the gun crashed to the ground injuring one of the gunners trying to install the gun.

From the New Schools Pavilion we can also get a good view of the boating pool at the base of the Shot Tower as shown in the following photo:

My father also took a photo at the base of the Shot Tower:

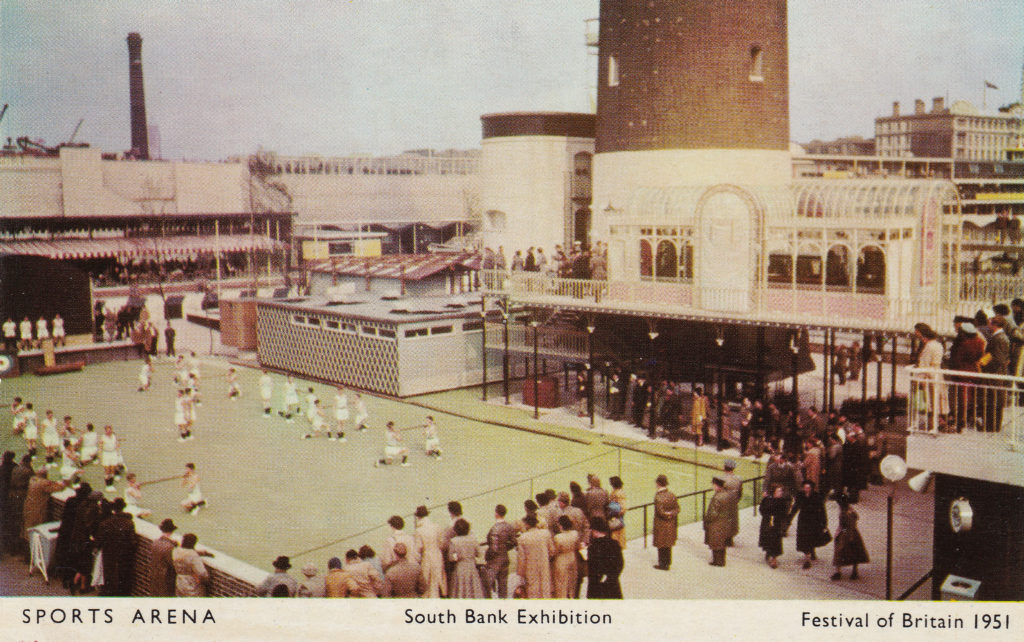

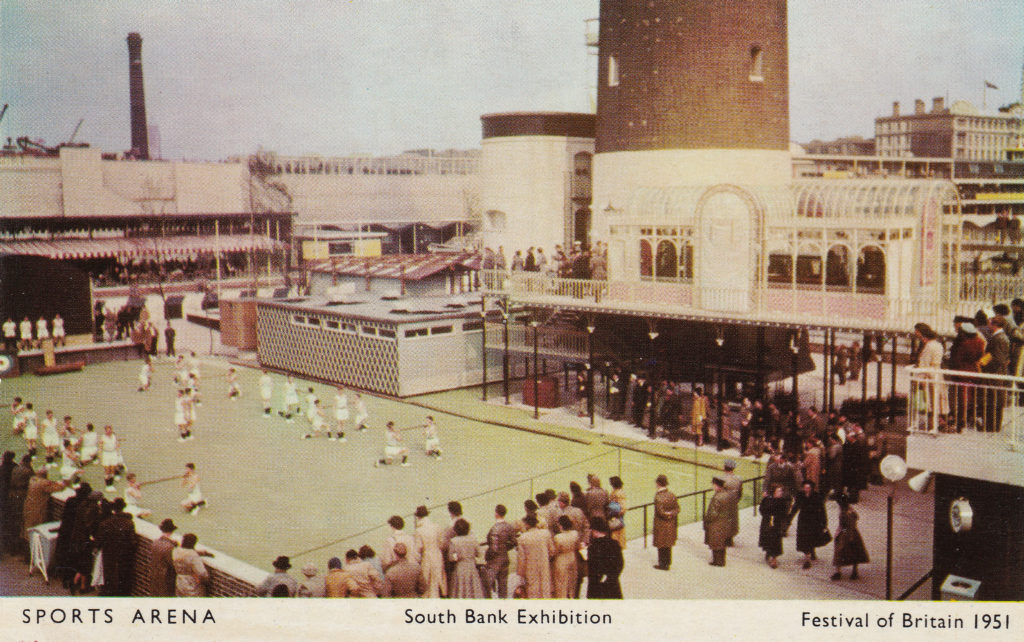

Behind the Shot Tower at position 21 on the map is the Sports Arena which was used to demonstrate a wide variety of sports during the festival. One of the aims of the Sports Arena was to encourage visitors to the festival to take part in sports, indeed the view at the festival was that it is more important for wide participation in sport across the population, than British sportsmen leading the world.

Look to the right of the Sports Arena and just in front of the Shot Tower and you will see a model of the 1851 Great Exhibition on stilts. I will come to this later in this post.

Another view of the Sports Arena showing the location in relation to Waterloo Bridge.

Photo today showing the area occupied by the Sports Arena and the Shot Tower:

The Festival Pier is where the Rodney Pier was located during the festival:

In the background of the Sports Arena photo, there was a model of the 1851 Great Exhibition. My father took a photo of the pavilion after the festival had closed.

Although the centenary of the 1851 Great Exhibition was one of the original justifications for the 1951 Festival of Britain, it was almost forgotten in the planning of the pavilions and exhibits. The raised pavilion was almost an afterthought to ensure there was a reference to the exhibition of 100 years earlier.

At each end of the interior of the pavilion were rotating screens with coloured views of different aspects of the 1851 exhibition. In the centre, a model of the exhibition along with a model of the opening ceremony along with a spoken description of the scene and music performed at the 1851 opening ceremony.

It is understandable that there was very little reference to the 1851 exhibition in 1951, the centenary being almost accidental. The 1851 exhibition was an international exhibition with manufactured goods from across the world whereas the 1951 exhibition was focused on British industry. The 1951 exhibition was also a celebration of Great Britain – the land and people compared to the 1851 exhibition’s international outlook.

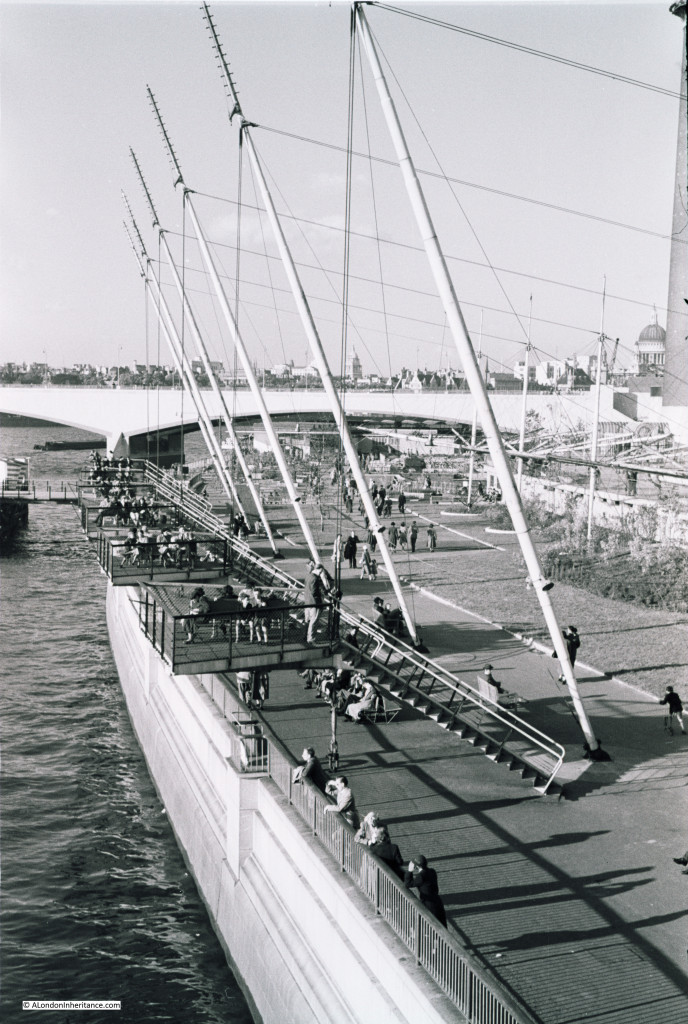

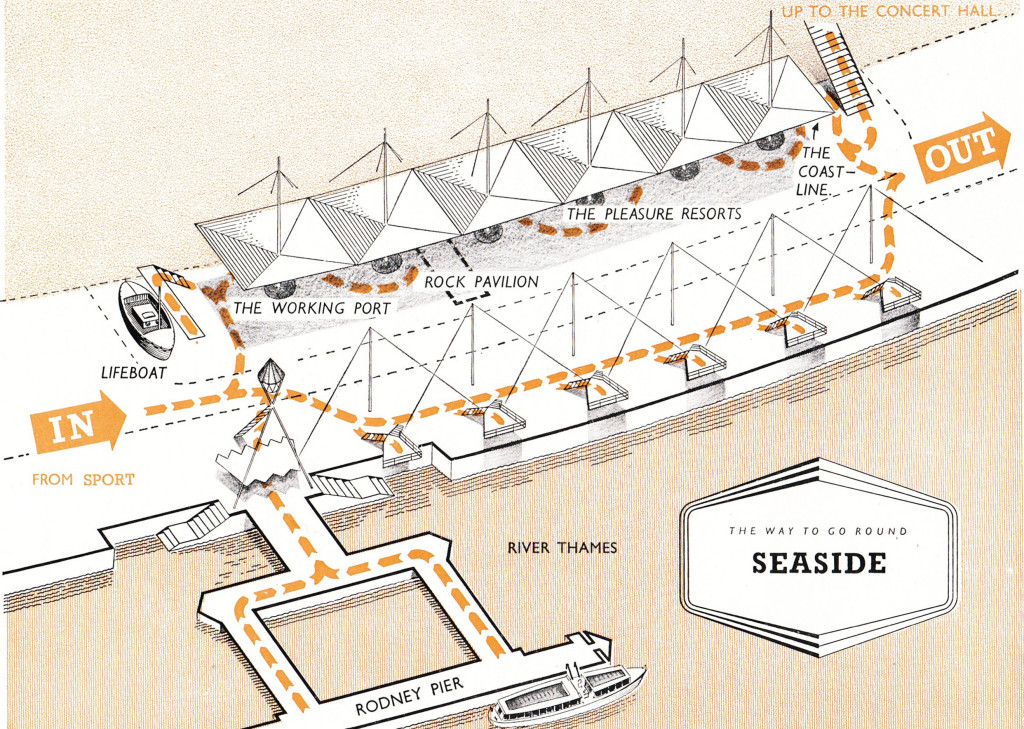

From the area of the Sports Arena and Shot Tower we can now head towards Hungerford Bridge and the next display – the Seaside. This was not in a pavilion but ran along the embankment in front of the Royal Festival Hall as can be seen in the following photo:

The seaside was where “the British feel the need to relax – either after a hard week in their industrial cities or a hard year on their land”.

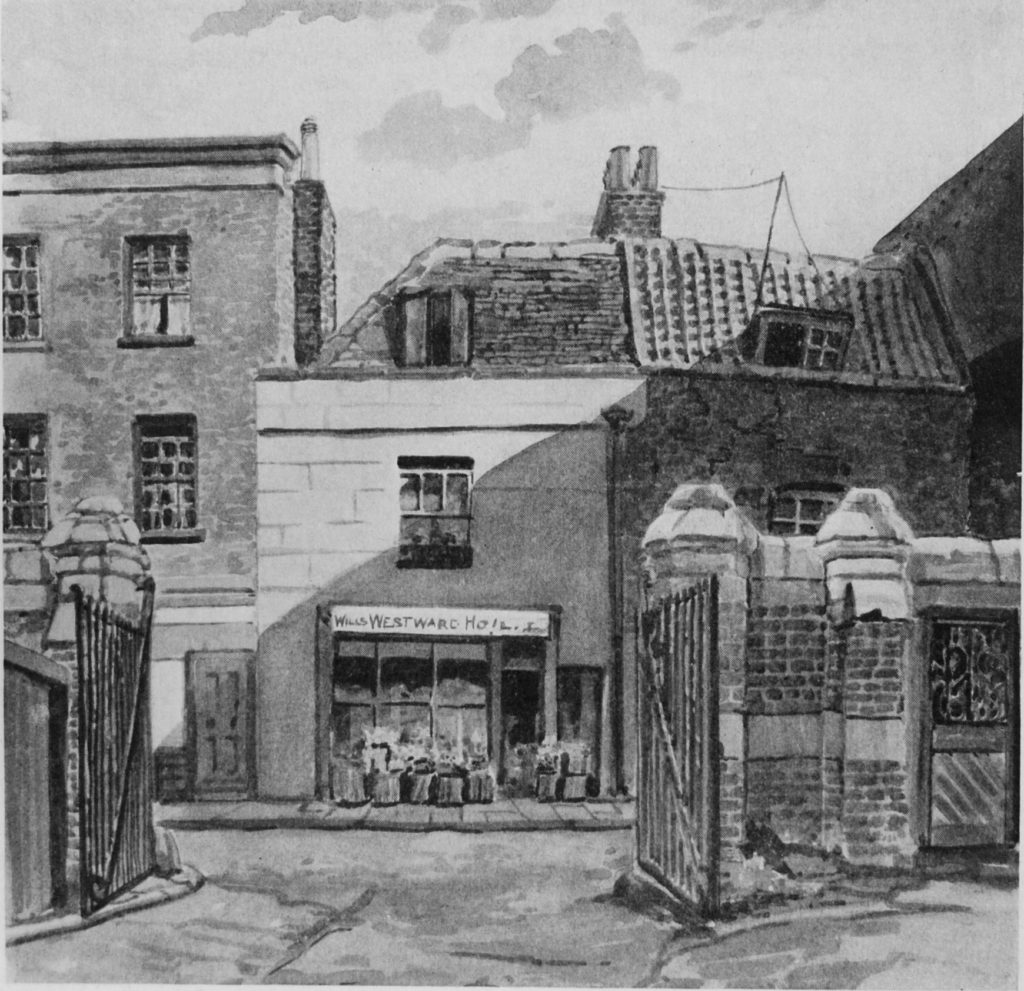

The Seaside was characterised at the festival as “All this bright and breezy business with magic rock and funny hats and period peepshows, is conducted here against the background of a characteristically British seafront; a medley of Victorian boarding-houses, elegant bow-fronted Regency facades, ice-cream parlours, pubs, and the full and friendly gaudiness of the amusement park”.

The Seaside also touched on the equipment needed by those who work on the shores of the country and the display included the latest design of lifeboat.

The view of the coast within this section also included a display of five samples of stretches of coastline to show the visitor the beauty and variation to be found along the British coast.

The Seaside also included viewing platforms raised over the edge of the Thames. These can just be seen to the right of the above photo, however one of the photos my father took immediately after the Festival closed shows these viewing platforms running along the length of the embankment:

That completes the walk through the Downstream Circuit of the exhibition. In addition to the core areas and pavilions we have walked through, there were two other minor displays. One covering Television which told the story of the development of television and how the service by the BBC (reintroduced 5 years earlier) will provide a platform for entertainment and information.

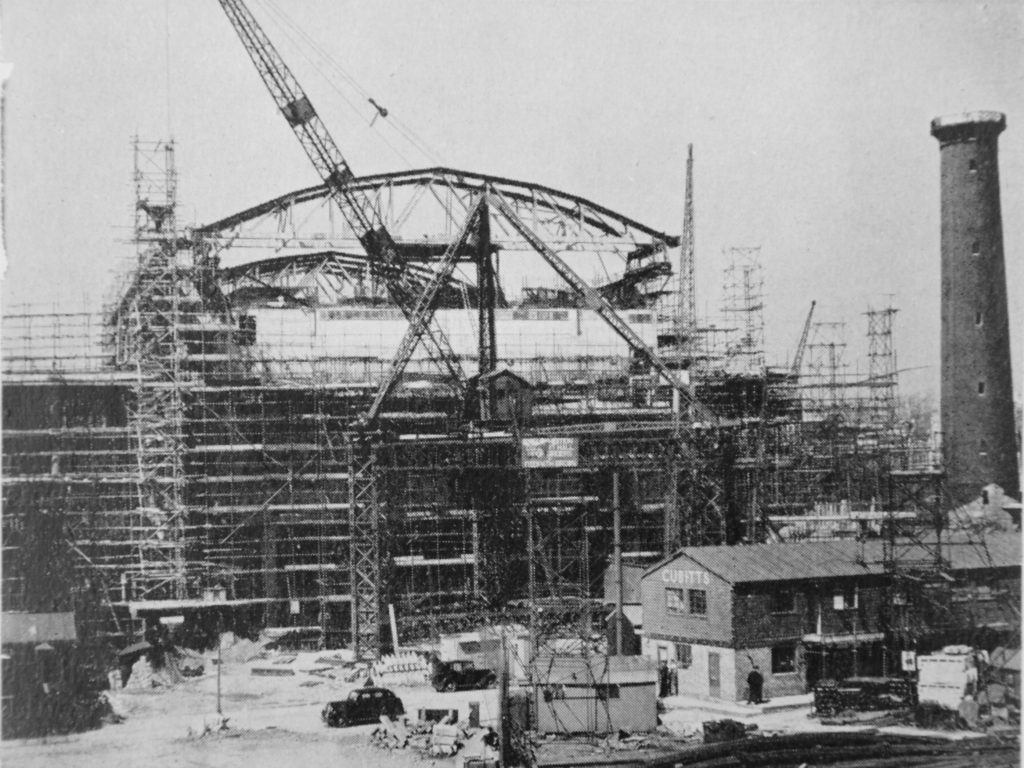

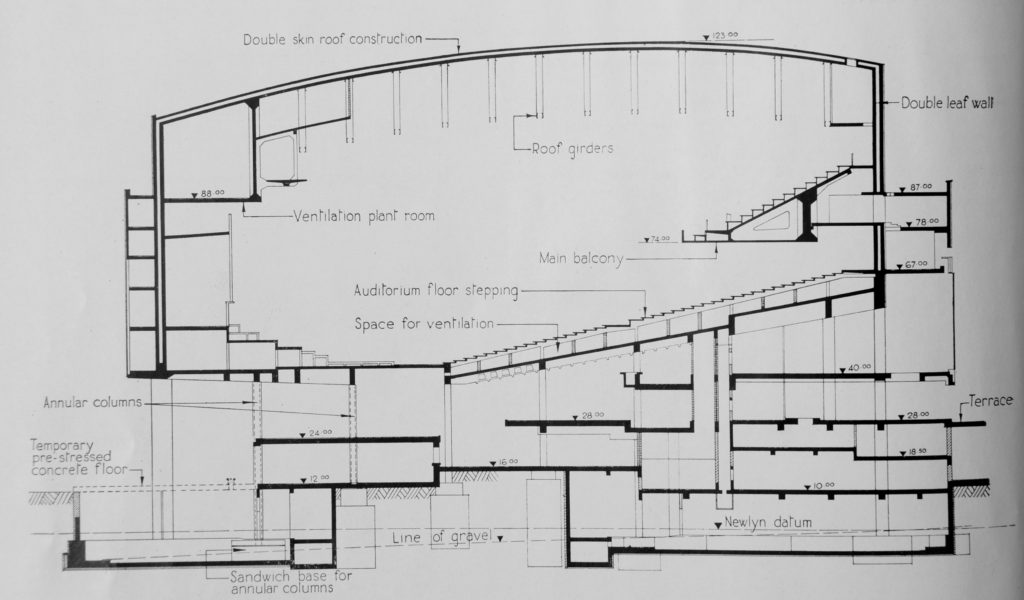

There was also a Telecinema, which was the first cinema in the world to be specially designed and built to show both films and television. The Telecinema showed live broadcasts from across the festival site along with a series of documentaries specially produced for the festival.

And as a final view of the site as we leave across Hungerford Bridge here is a photo my father took shortly after showing the Royal Festival Hall, the viewing platforms over the river and to the lower right of the Royal Festival Hall, one of the many outdoor works of art that were installed as part of the festival. Also on the right of the Royal Festival Hall is the flagpole that is now on the opposite side of Hungerford Bridge – see my photo of the flagpole in my post on the Upstream Circuit.

The Festival Site Today

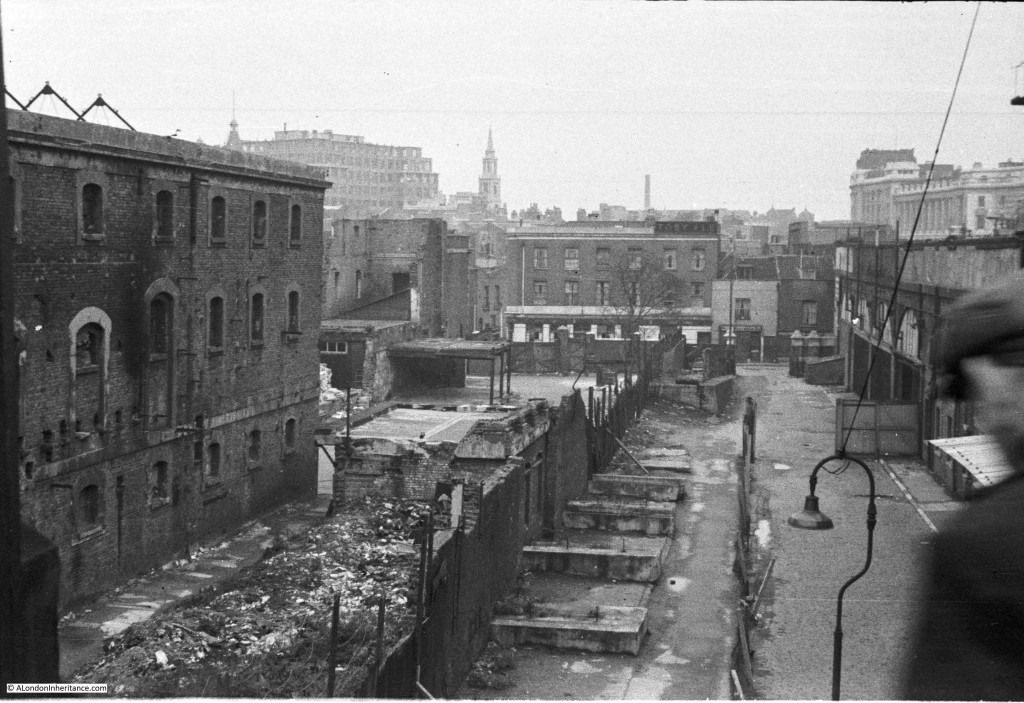

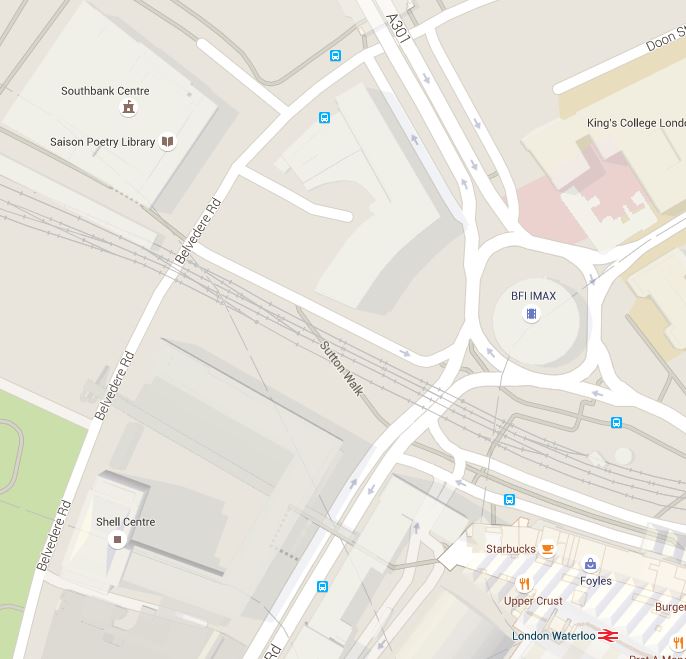

The majority of the old festival site is still dedicated to arts and entertainment with the Royal Festival Hall at the core along with buildings created since the festival such as the Queen Elizabeth Hall, the Purcell Room and Hayward Gallery, built on the site of the Shot Tower. Both the old Upstream and Downstream Circuits were split into two with the Shell Centre upstream and downstream buildings occupying the space. The area between Belvedere Road and the river in the upstream area is now the Jubilee Gardens with the London Eye occupying the space where the 51 Bar and the Nelson Pier were located during the festival.

The site continues to undergo major change with the low rise office buildings around the Shell Centre Tower currently being demolished in preparation for a large cluster of new, mainly luxury apartments to be built.

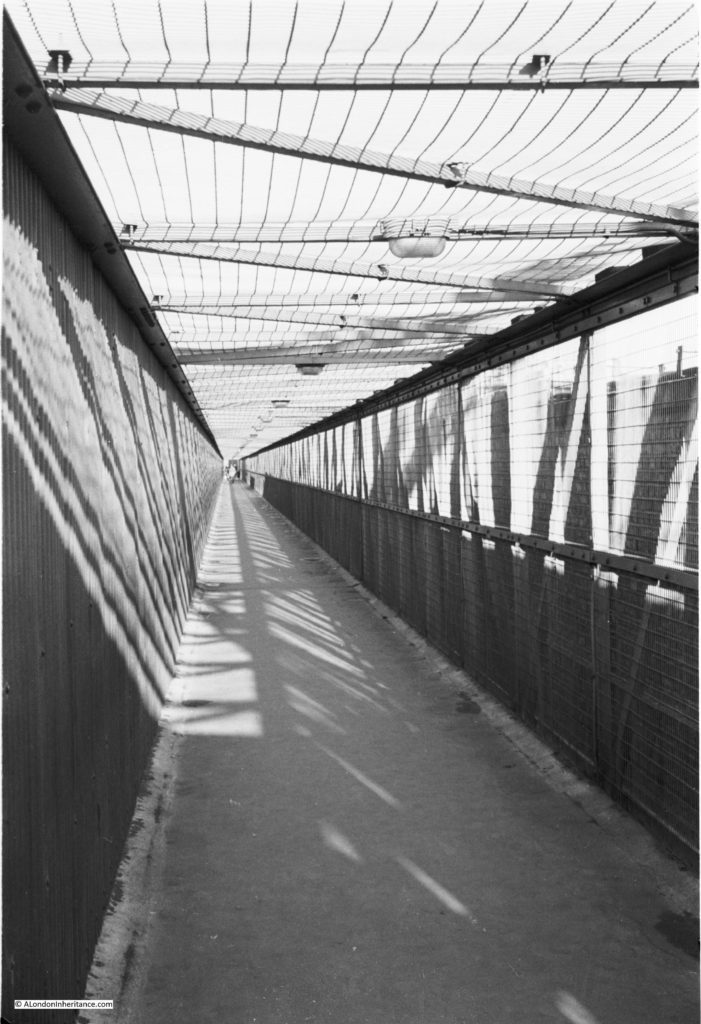

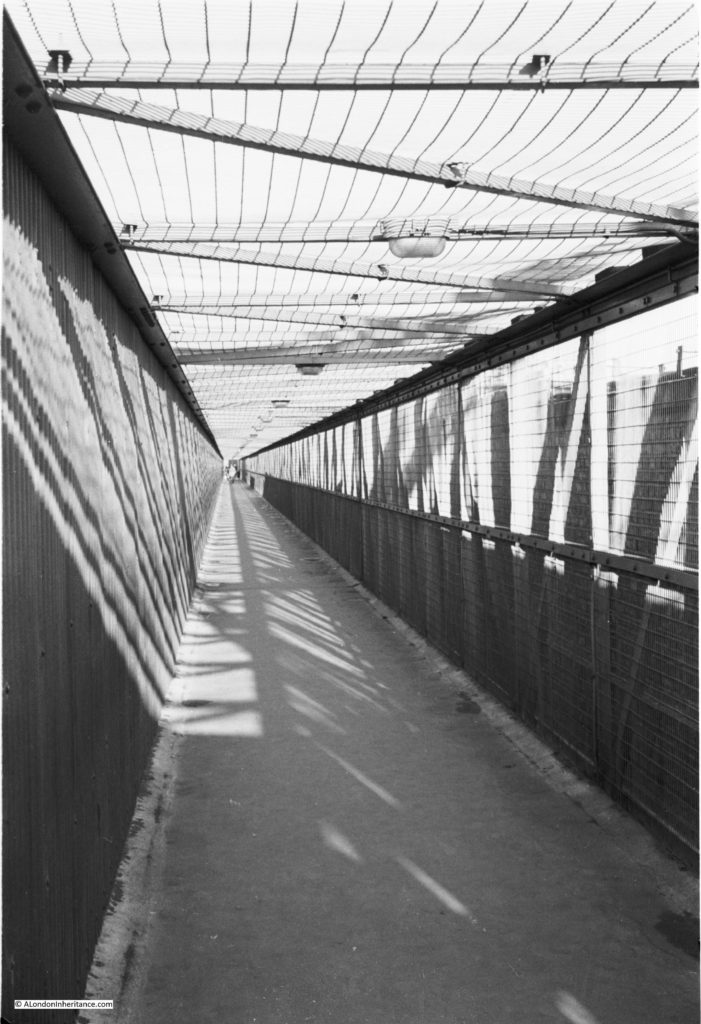

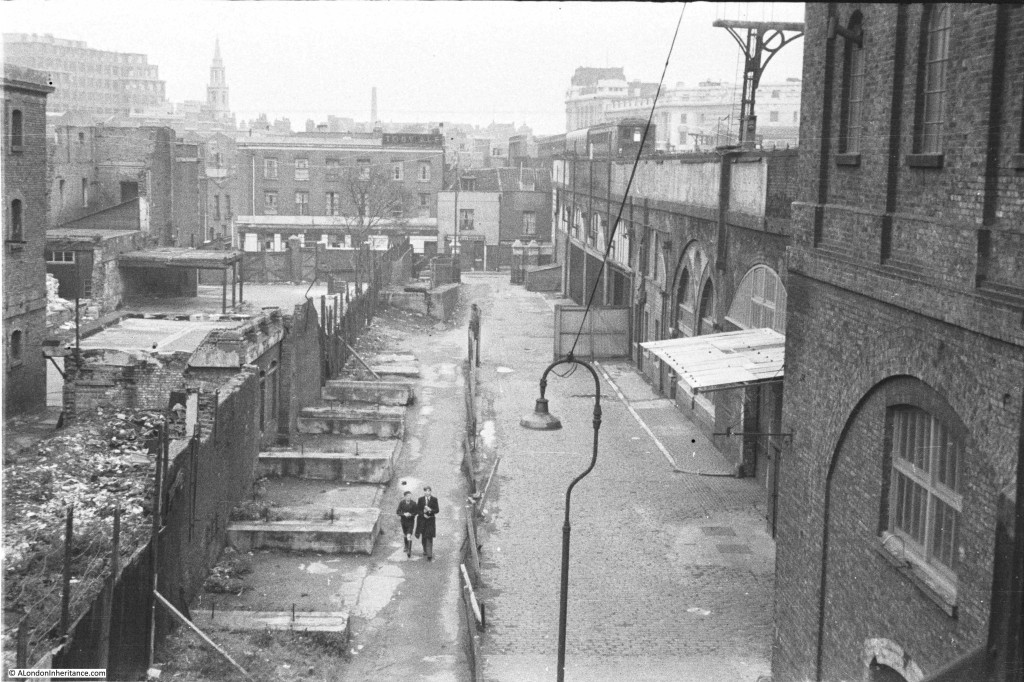

The following panorama taken from under the now closed footbridge from Waterloo Station to the opposite side of York Road (along the same alignment as the original festival Station Gate) shows the large building site that this area has now become – the original area occupied by the first pavilions of the upstream circuit.

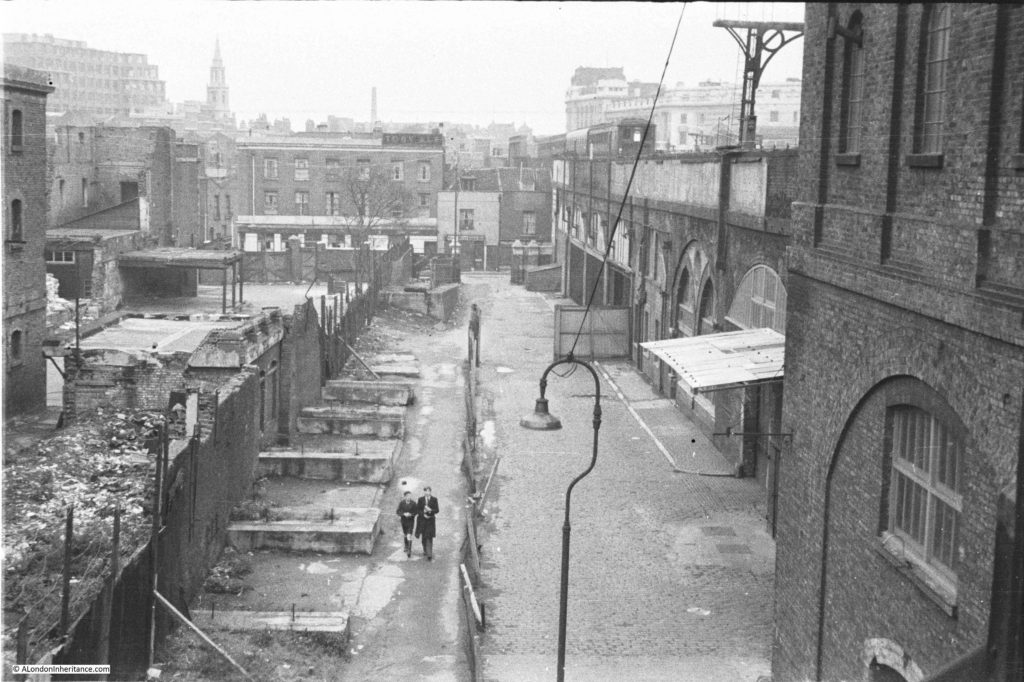

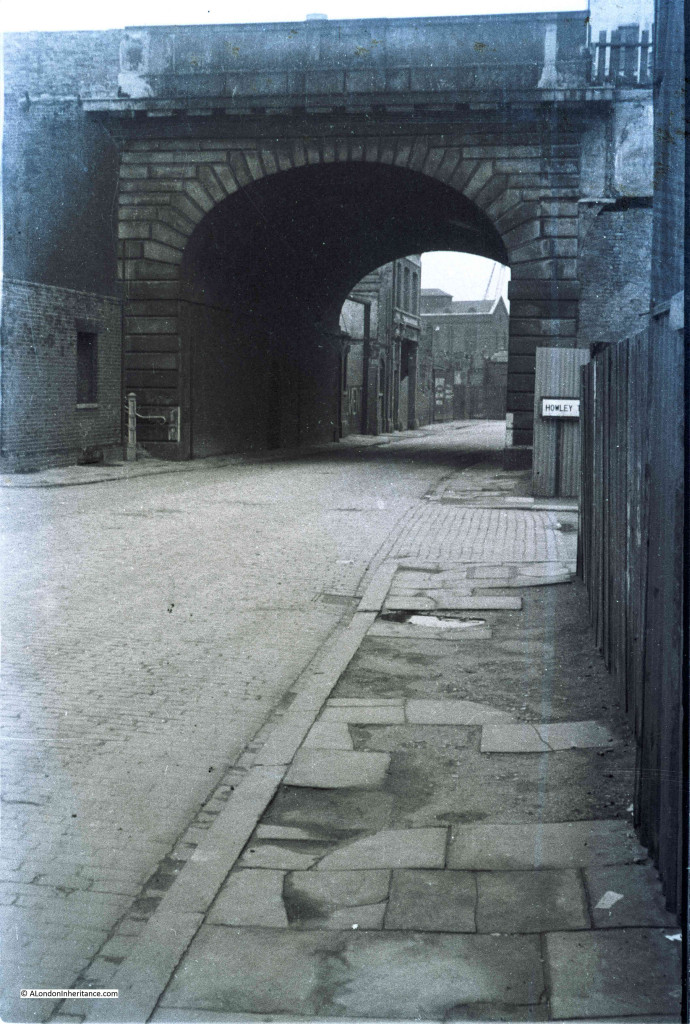

But throughout all these years of such significant change, Belvedere Road still runs through the site, maintaining a link with the original Narrow Wall when the Thames swept up to the marsh that covered much of Lambeth.

The Festival Closes

Following closure, the new Conservative government quickly ordered the demolition and sale of the festival pavilions, exhibits and artwork so by the end of 1952 not much was left.

One can only imagine the frustration of the designers, architects and all those all had put so much work into creating a festival that although there were major gaps in the story the festival told of the British and it could also be a rather narrow view, the festival did provide a very optimistic view of the future and what the benefits of design, architecture, science and art could bring to the “man in the street”.

I hope you have found these last three posts on the Festival of Britain – South Bank Exhibition of interest. In the coming weeks I will cover the wider aspects of the Festival along with visits to the Festival Exhibition of Architecture at Poplar and the Festival Pleasure Gardens at Battersea.

I included a list of books I have used to research the Festival in my first post. There are also a number of excellent films that show the thinking behind the Festival and the Festival site, including:

And looking at the area today, a film produced for the Waterloo Sights and Sounds project which can be found here.

alondoninheritance.com