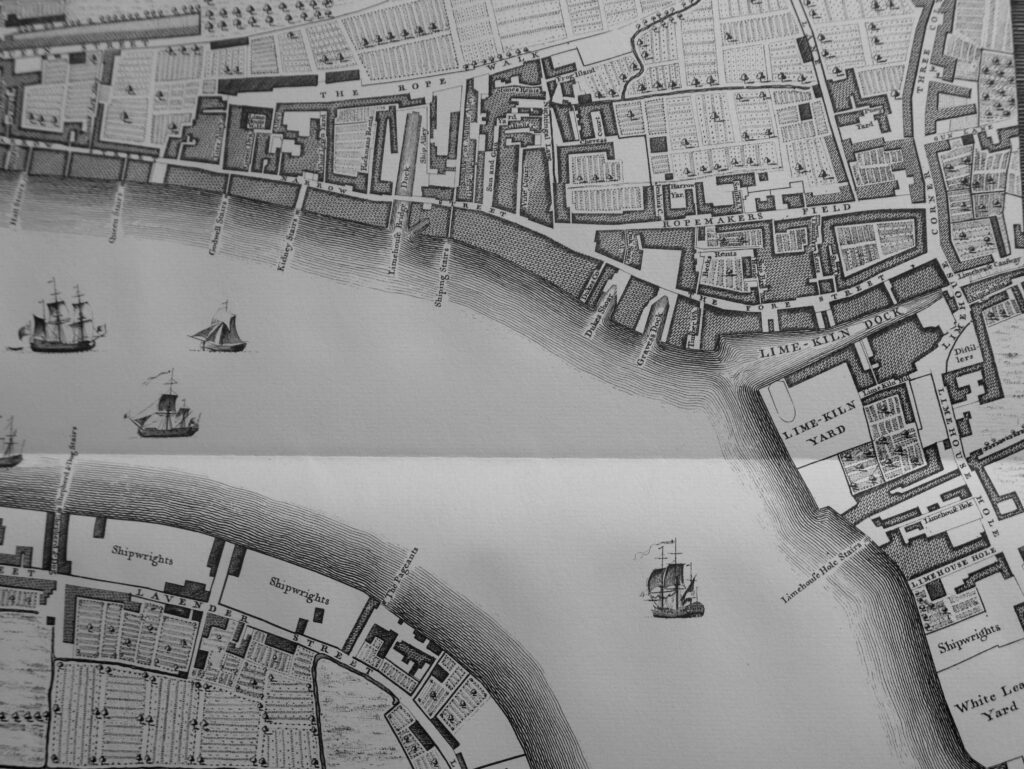

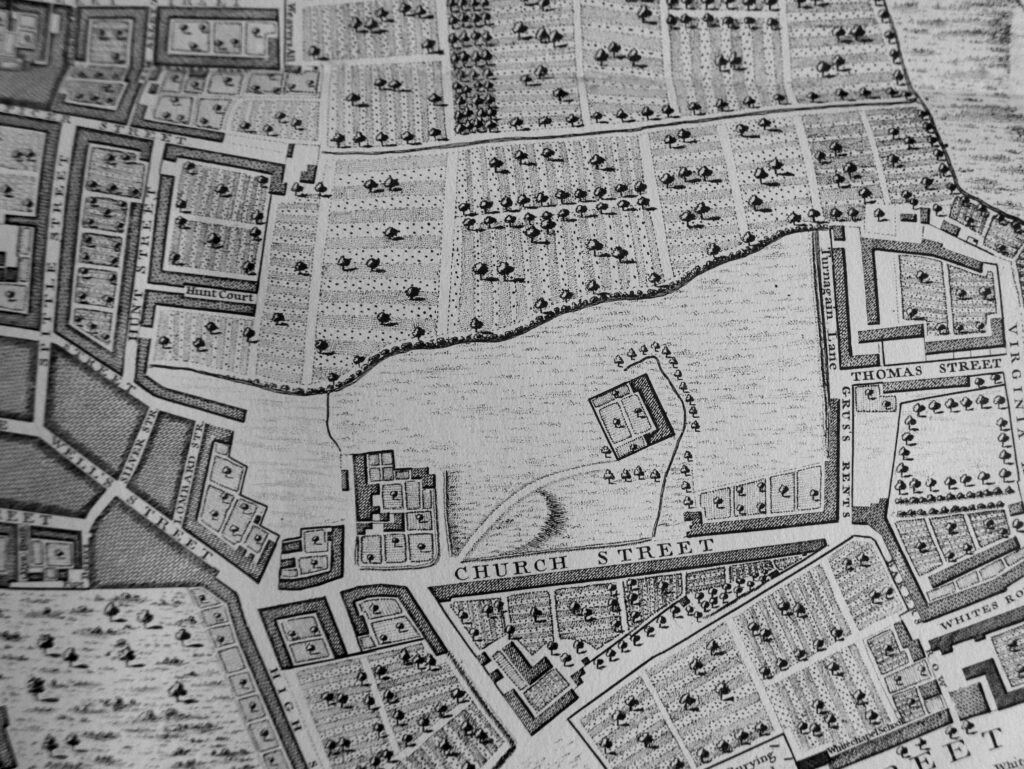

The banks of the Thames was not just full of docks and warehouses, but was also a place of industry, attracted by the easy transport of raw materials and goods along the river. Many of these industries were very dirty, polluting the local area and blighting the lives of those who lived nearby.

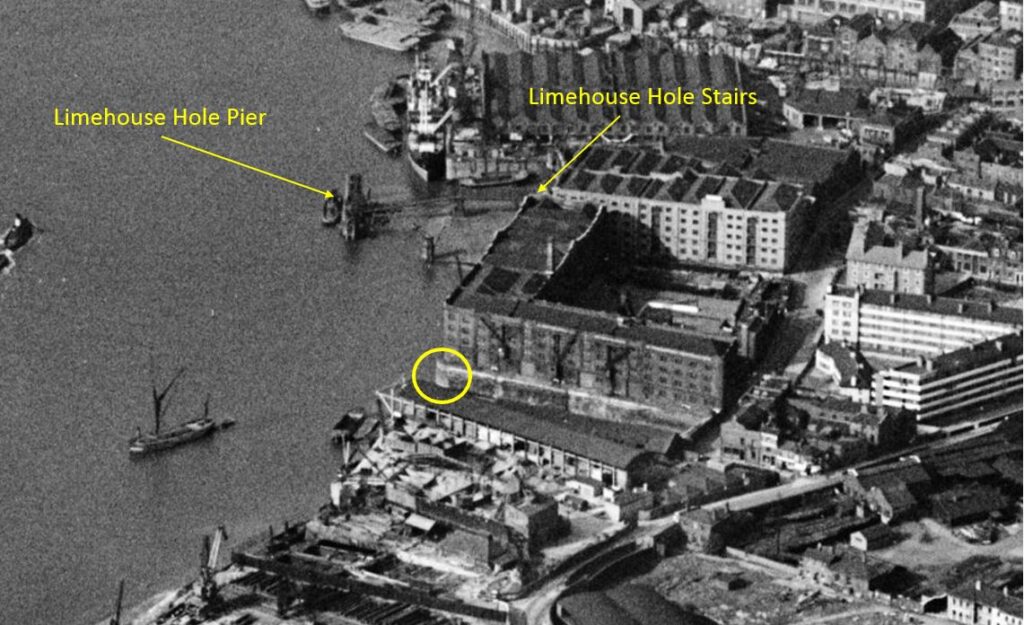

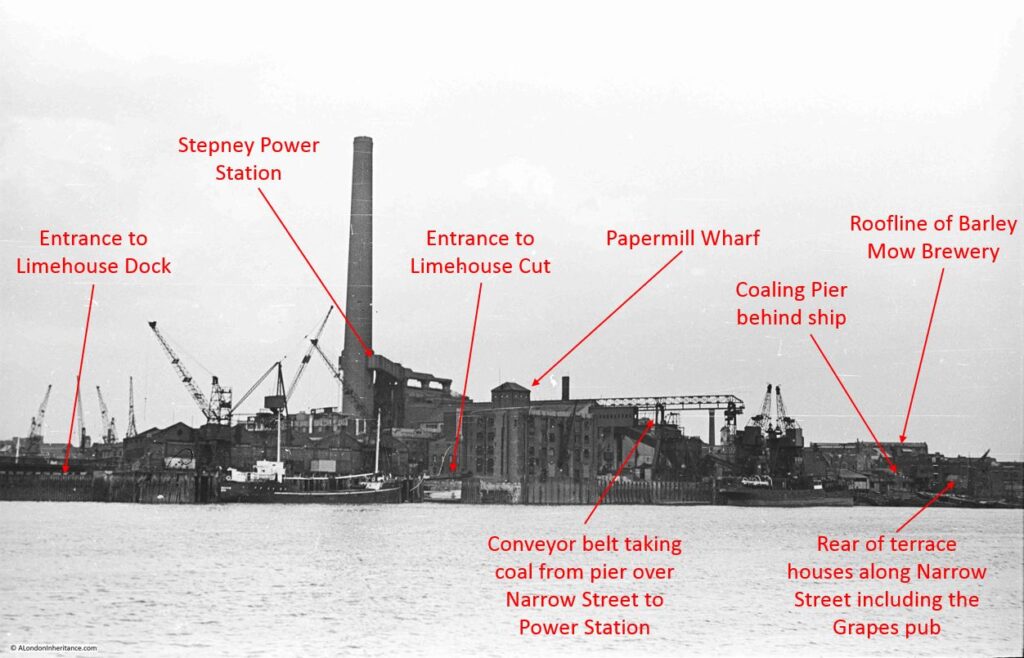

One of these was Stepney Power Station, a coal fired electricity generator, that can be seen in the following photo taken by my father in August 1948 on a boat trip from Westminster to Greenwich:

The same view in January 2024:

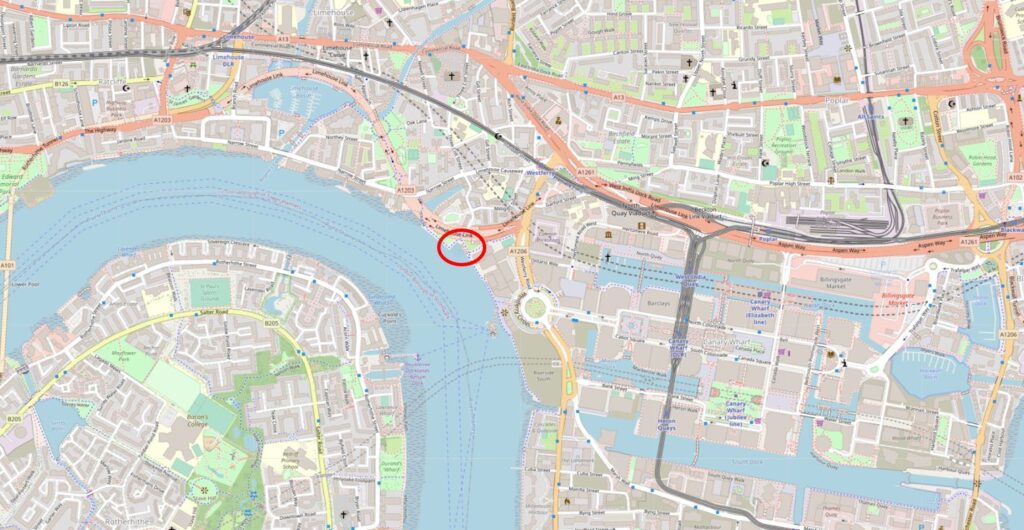

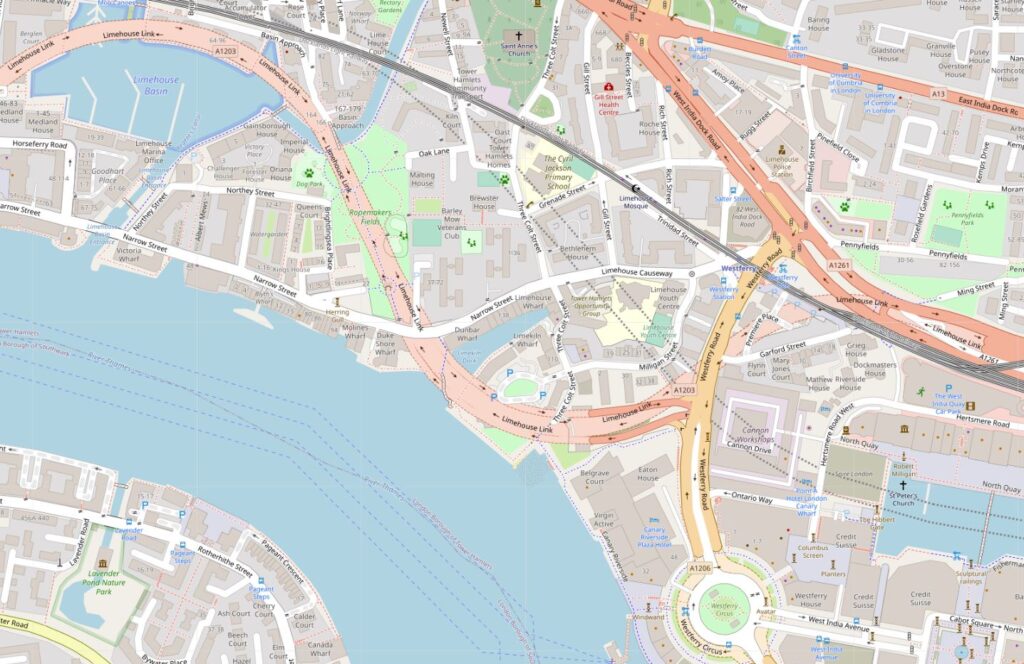

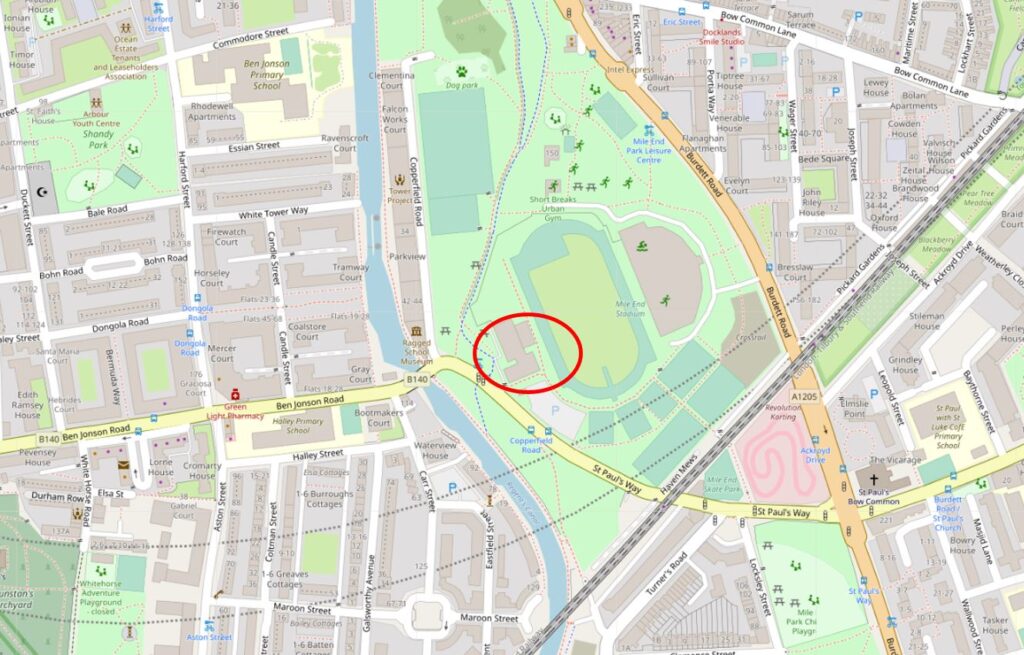

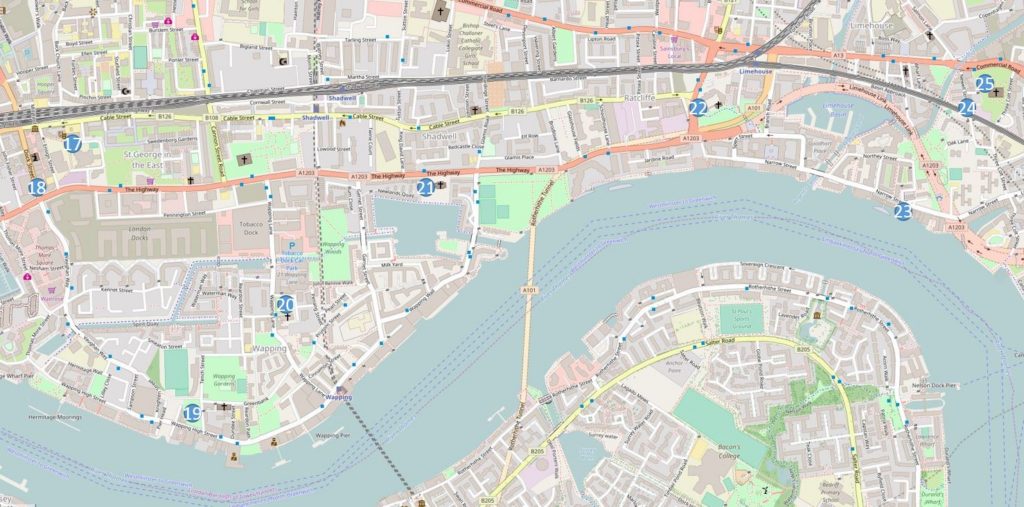

I have outlined the location of Stepney Power Station in red, in the following map of the area today (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

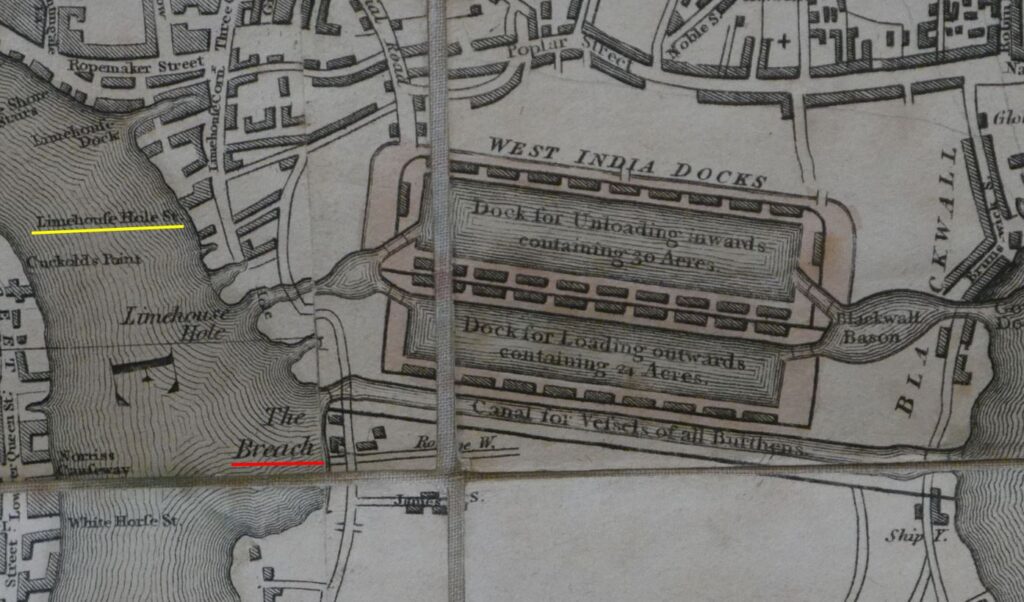

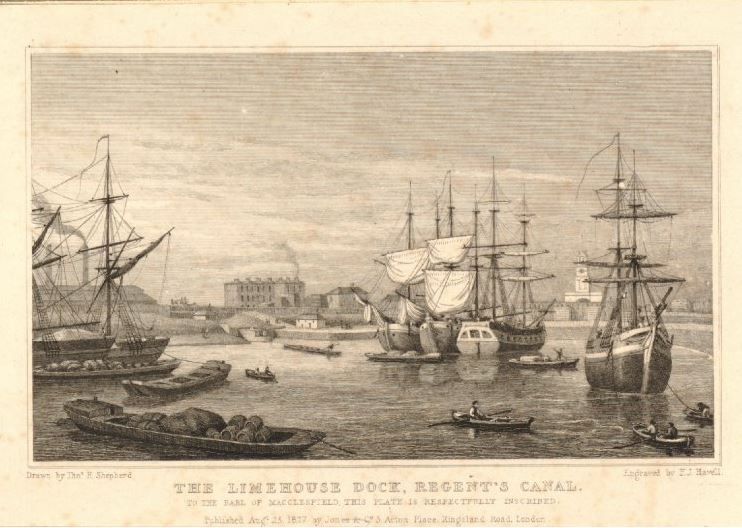

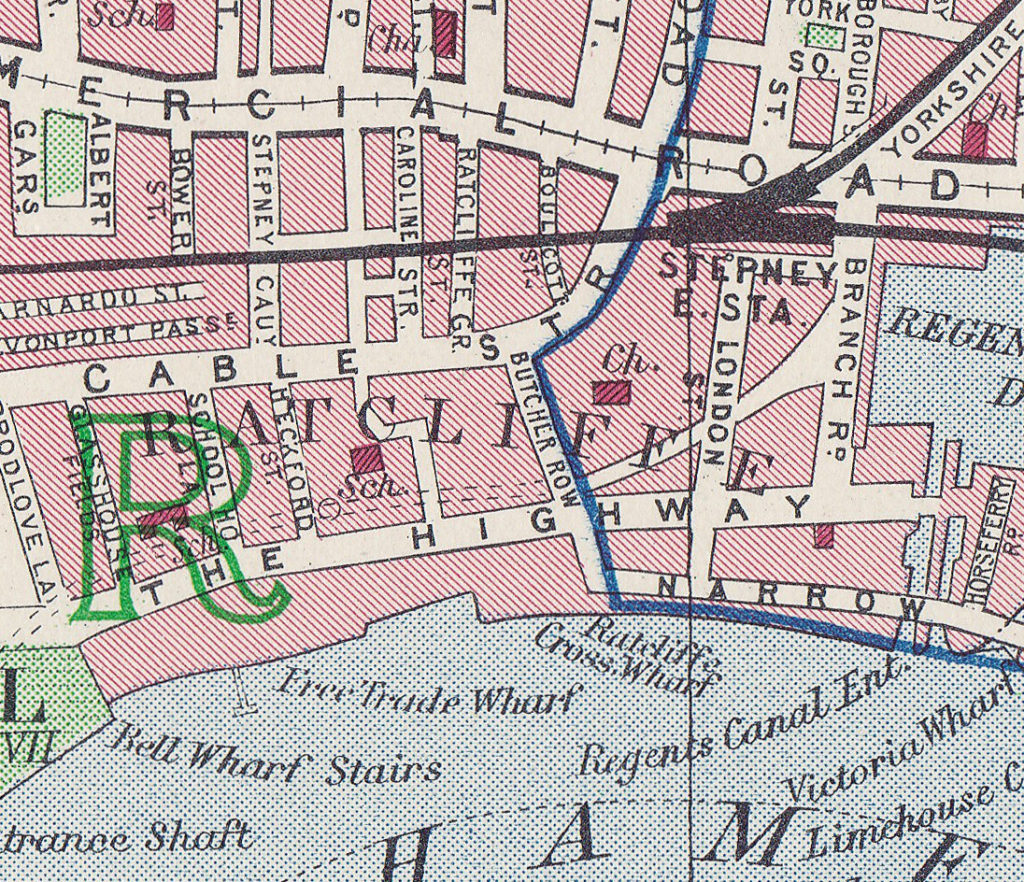

As can be seen, the power station is next to Limehouse Dock (originally Regent’s Canal Dock), and the name Stepney Power Station comes from the power station being in, and originally built, by the Borough of Stepney. It was occasionally referred to as Limehouse Power Station, which more accurately referred to its geographic location.

At the start of the electrification of London, lots of small electricity generating stations sprung up across the city, funded and built by a mix of private and public bodies.

These would supply their local area, with limited, if any, connection to other power generators.

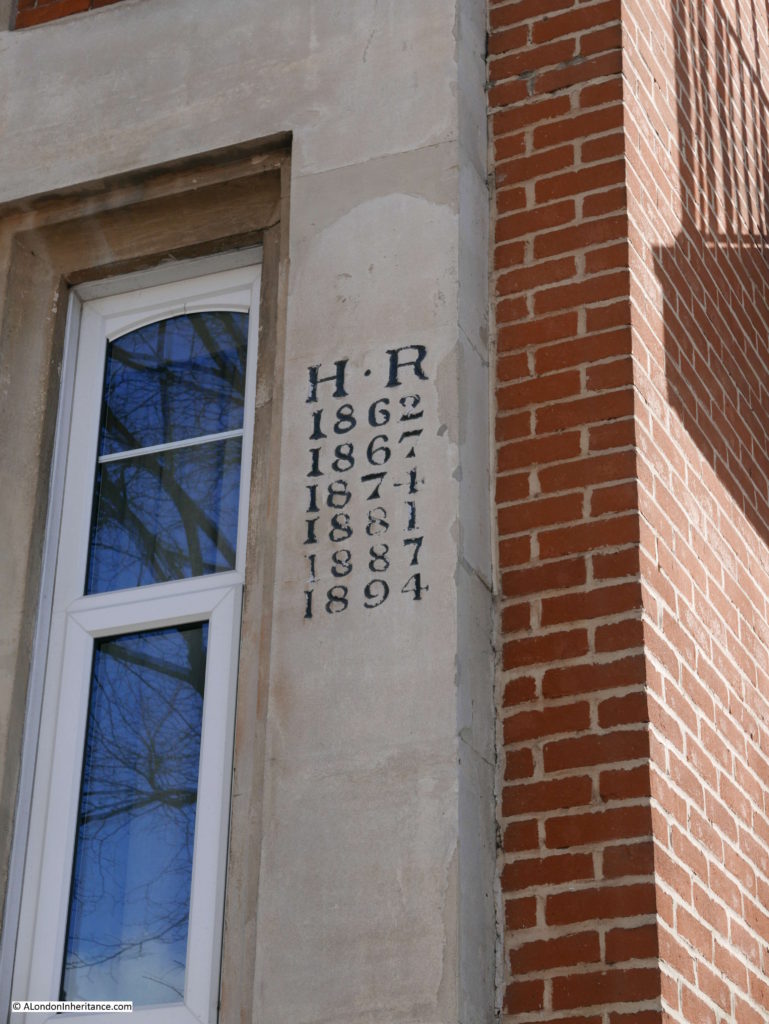

London’s Boroughs were under pressure to develop and build electricity services to provide this new power source to homes, industry, the lighting of streets etc. and there were a large number of power stations built at the end of the 19th and the first decades of the 20th century.

My grandfather worked in two power stations in Camden (see this post for one of these), and my father worked for the St. Pancras Borough Council Electricity and Public Lighting Department which then became part of the London Electricity Board.

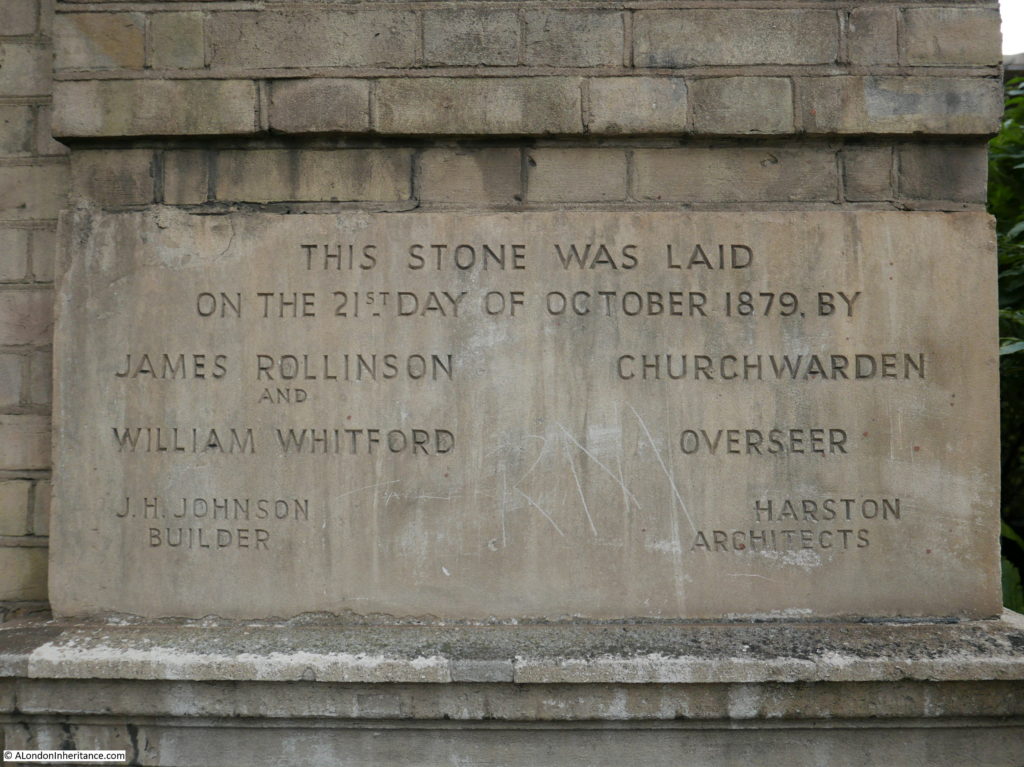

Stepney Power Station formerly opened on the 27th of October, 1909, as recorded by a report in the Morning Leader on the following day;

“An extension of the Stepney electricity undertaking was opened yesterday by the Mayor and Mayoress (the Hon. H.L.W. and Mrs. Lawson).

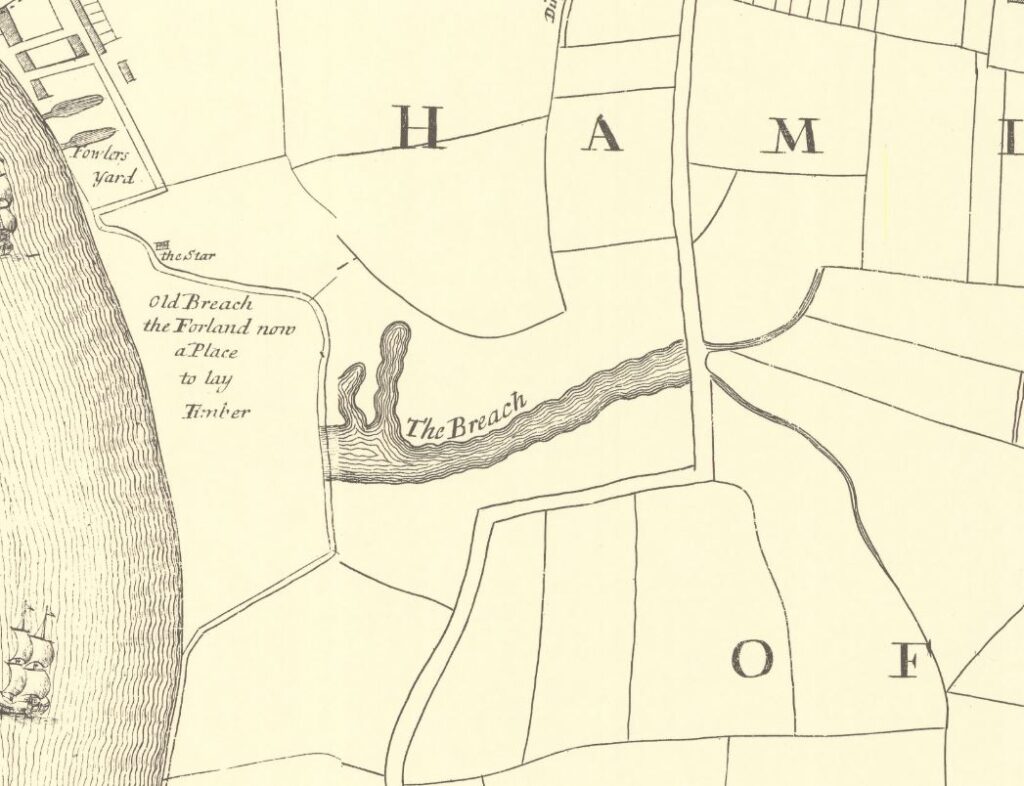

The new generating station is situated at Blyth’s Wharf on the river, which gives the advantages of cheap sea-borne coal and an ample supply of condensing water.

Councilor Kay mentioned yesterday that the whole station had been erected by the council’s officials, so that it was in every respect a municipal undertaking.”

The 1909 power station was relatively small, but in the following years it would rapidly grow as demand for electricity increased and the cables needed to carry electricity across Stepney were installed and spread out across the Borough.

The version of the power station in my father’s 1948 photo shows the power station at its maximum size, with the tall chimney, which was added in 1937. There would be further upgrades in the following years, but from the river, this is how the station would have looked.

To help identify the location of the power station, features of the power station, and a comparison with the same view today, I have marked up the following two photos, starting with the view in August 1948:

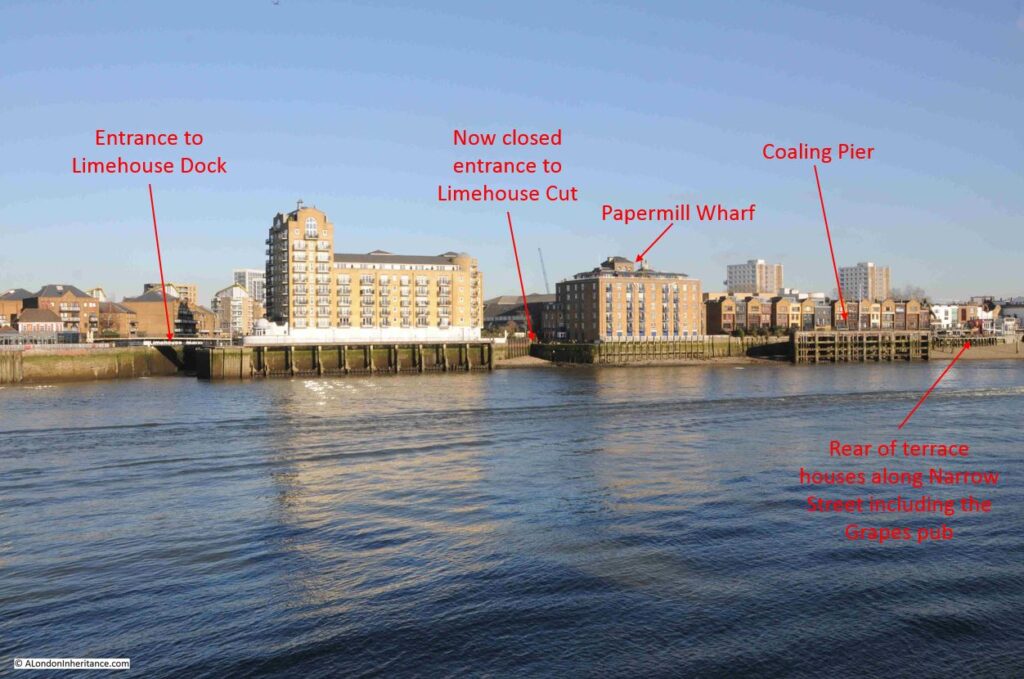

And January 2024:

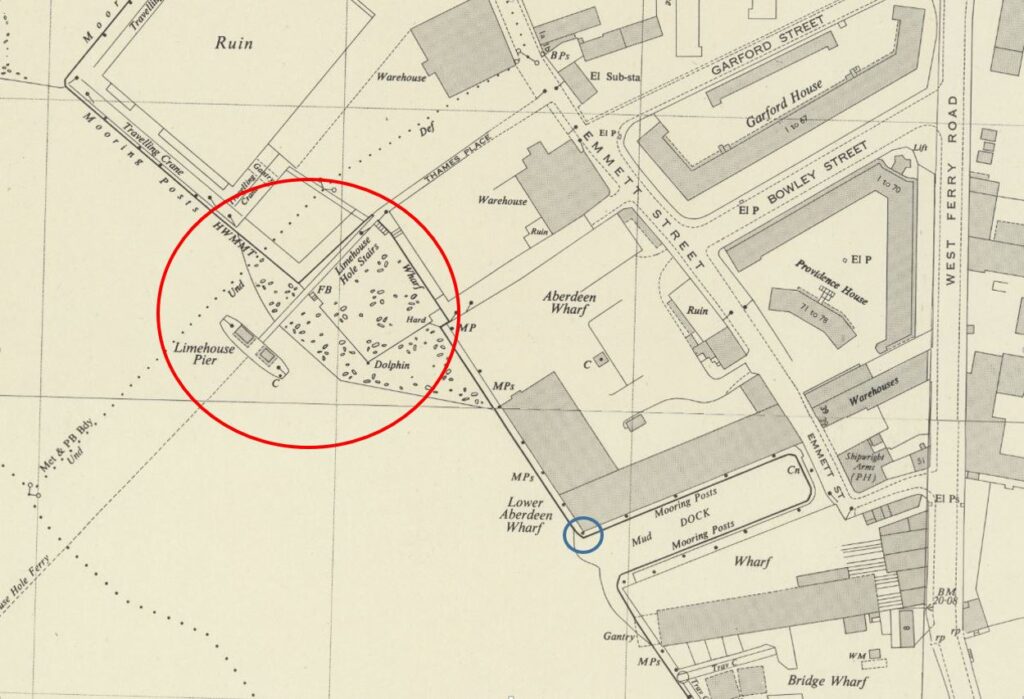

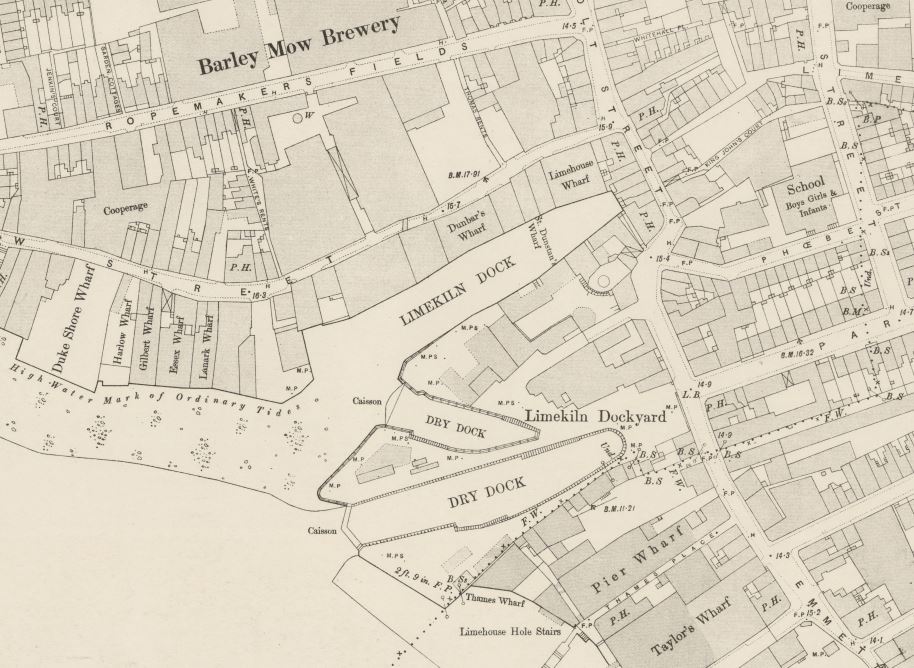

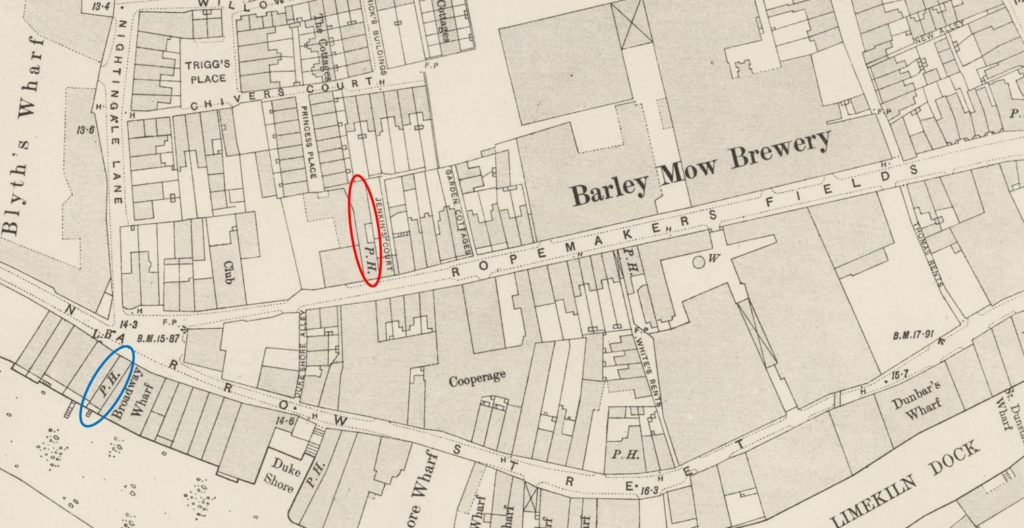

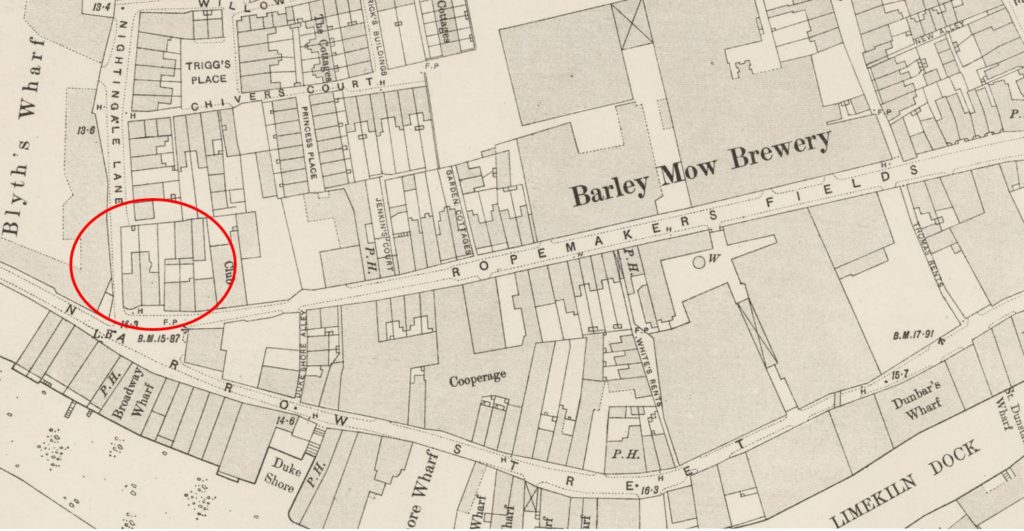

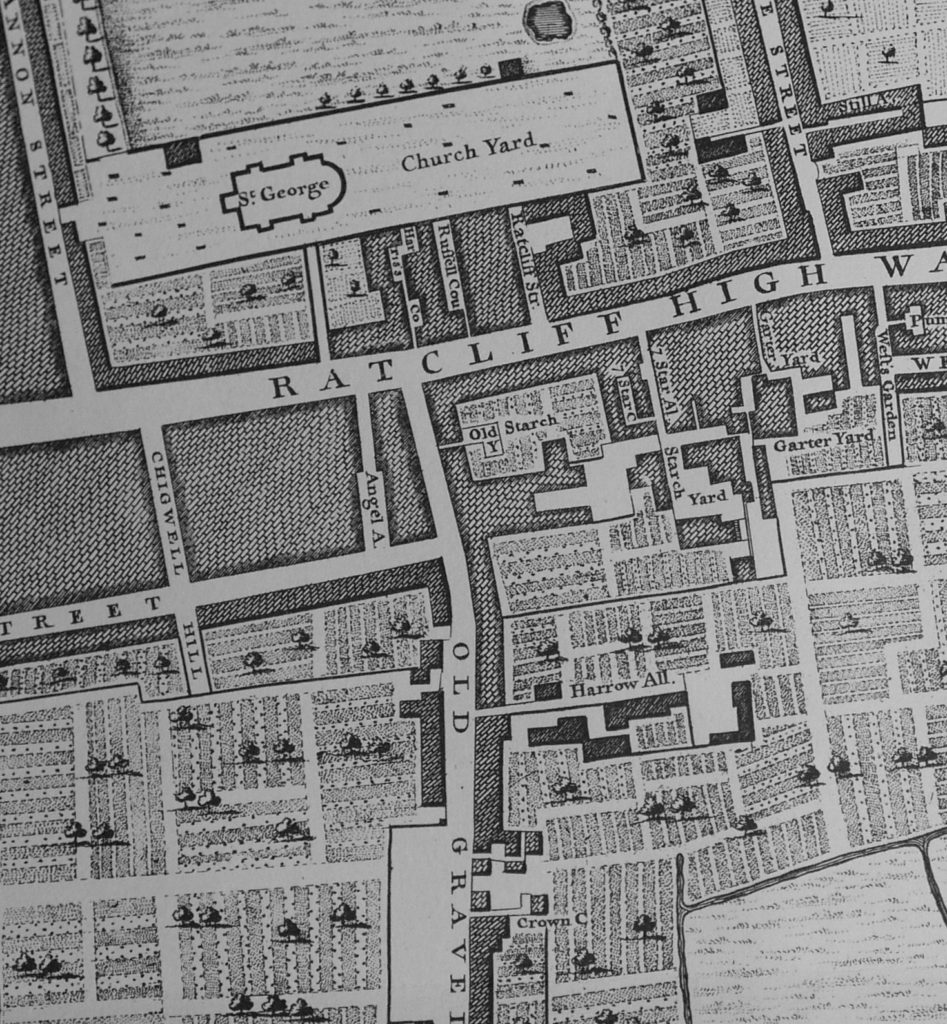

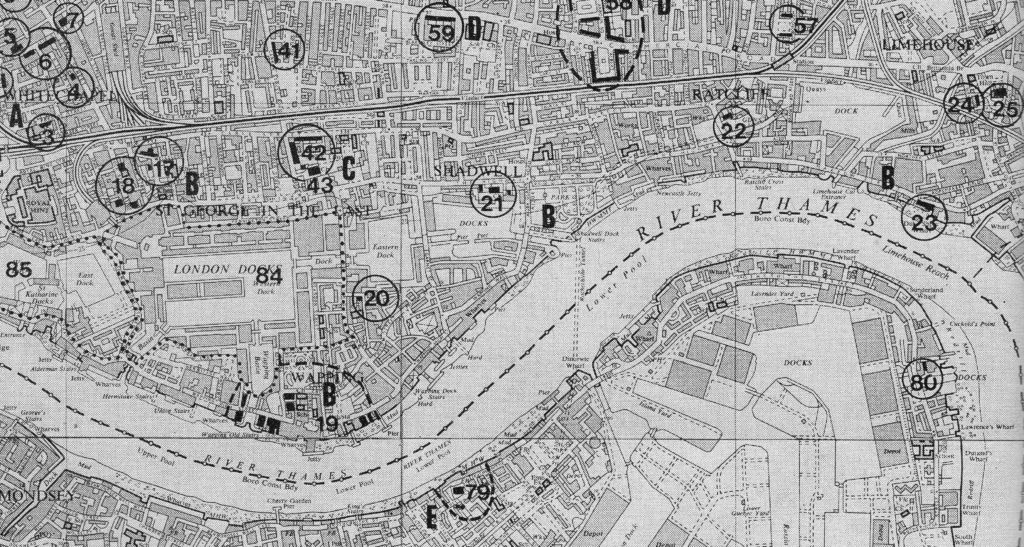

The following extract from the OS map shows the location of Stepney Power Station, labelled as “electricity works”. The conveyor transporting coal from the coaling pier to the power station can be seen, and between the coaling pier and Narrow Street, there is an open space. In the 1909 report of the opening, there is a reference that the “new generating station is situated at Blyth’s Wharf on the river”, and this open space was Blyth’s Wharf (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

Being right next to the river was a perfect location for the power station. It enabled supplies of coal to come from the north east of the country, via sea then along the Thames. The river also provided ample supplies of cooling water and water for steam generation in the boilers.

As the generation capacity increased, and therefore the demand for coal, the coaling jetty was built in 1923 to simplify the transport of coal from ship to where it would be burnt.

Newspapers in the 1920s were full of adverts by Stepney Borough Council advertising that their supply of electricity was the cheapest in London due to the prime location of their power station.

Whilst good for the price of electricity, the location was not good for those who lived, worked, and went to school near Stepney Power Station. There were many complaints about the dirt and pollution from the power station, and if you look at the above map, just to the top right of the power station, there are two buildings marked “school”. These are mentioned in the following newspaper article.

From the East End News and London Shipping Chronicle on the 2nd of December, 1949:

“COAL DUST COMPLAINT – Stepney Council is joining the L.C.C. in ‘strong representations’ to the British Electricity authority about nuisances caused by the Stepney power station.

It is said that coal dust dispersed by the movement of coal at the power station can penetrate into class rooms at the Cyril Jackson school even when the windows are closed and the schoolkeeper’s house – about six yards away from the station – cannot be occupied.

Another nuisance is caused by grit from the chimney of the station, the council was told last week. The council point out that when they were in control of the chimney as electrical supply undertakers in 1935 they improved conditions there.”

As the article highlights, it was not just pollution from the chimney, it was also the dust created by the use of coal.

Coal had to be unloaded from ships, transported across Narrow Street, stored, and then pulverised reading for burning. All these activities would have created coal dust, much of which would have contaminated the local area.

Another example can be found in the East End News and London Shipping Chronicle on the 6th of April 1950:

“GRIT AND COAL DUST, COMPLAINT ABOUT STEPNEY POWER STATION – The public health committee reported to the last meeting of Stepney boro council:

Representations have been made to the Minister of Fuel and Power and the British Electric Authority with a view to securing an abatement of the nuisance caused by the emission of grit from the chimney of the Stepney power station and by coal dust distributed as the result of the movement of coal.

The representations have been duly acknowledged by the Ministry and British Electric Authority, in a communication to the Minister dated January 24, 1950, deprecates the suggestion that the condition has worsened since this station vested in the Authority; state that the Authority is fully alive to the responsibility for ensuring that only the minimum interference is caused in the vicinity; and suggest that the chief engineering inspector of the Ministry should visit the site for the purpose of determining whether any further remedial measures are practicable.

We are fully alive to the fact that the operation of a generating station in a highly congested district must, to some extent, detract from the amenities of the persons residing therein but we are seriously concerned that the health of the children attending the Cyril Jackson school, which adjoins the station, may be prejudiced by the emission of grit and coal dust. We understand the extent of the coal dust nuisance varies with the climatic conditions and, it appears to us that since pulverised fuel is being used the coal storage bunkers should be effectively covered in. before making further representation, however, we have directed that inquiry be made of the Minister of Fuel and Power as to whether the Ministry’s chief inspector has visited the site, if so, what further remedial measures are considered necessary.”

I can only imagine what the long term impact on the health of the children attending the Cyril Jackson school would have been. The mention in the above article to the “British Electric Authority” is to the post-war nationalisation of the country’s electricity generating and distribution industries, which brought together all the private and public generating stations, and their distribution networks, into single bodies.

The British Electricity Generating Authority would late become the Central Electricity Generating Board, which would build the national transmission network (the pylons, or towers as they should be known), which allowed the small power stations in London to be closed, and electricity transported from much larger stations across the rest of the country.

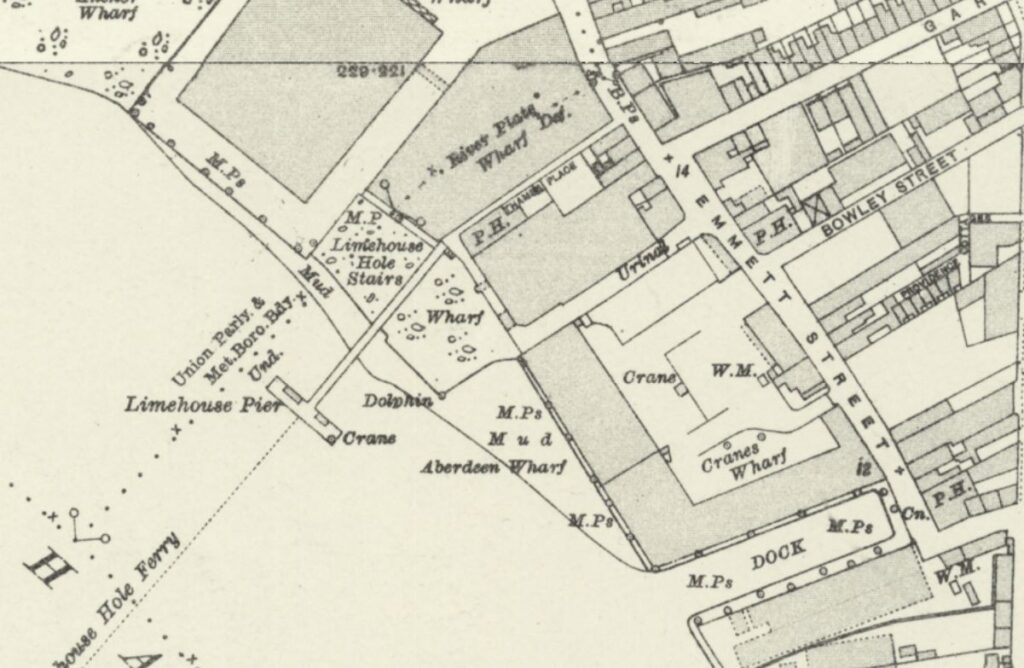

When Stepney Power Station was first built, each of the boilers had it’s own chimney. This was standard construction in the first decades of the 20th century (see this post which includes a photo of the first Bankside power station with its rows of chimneys).

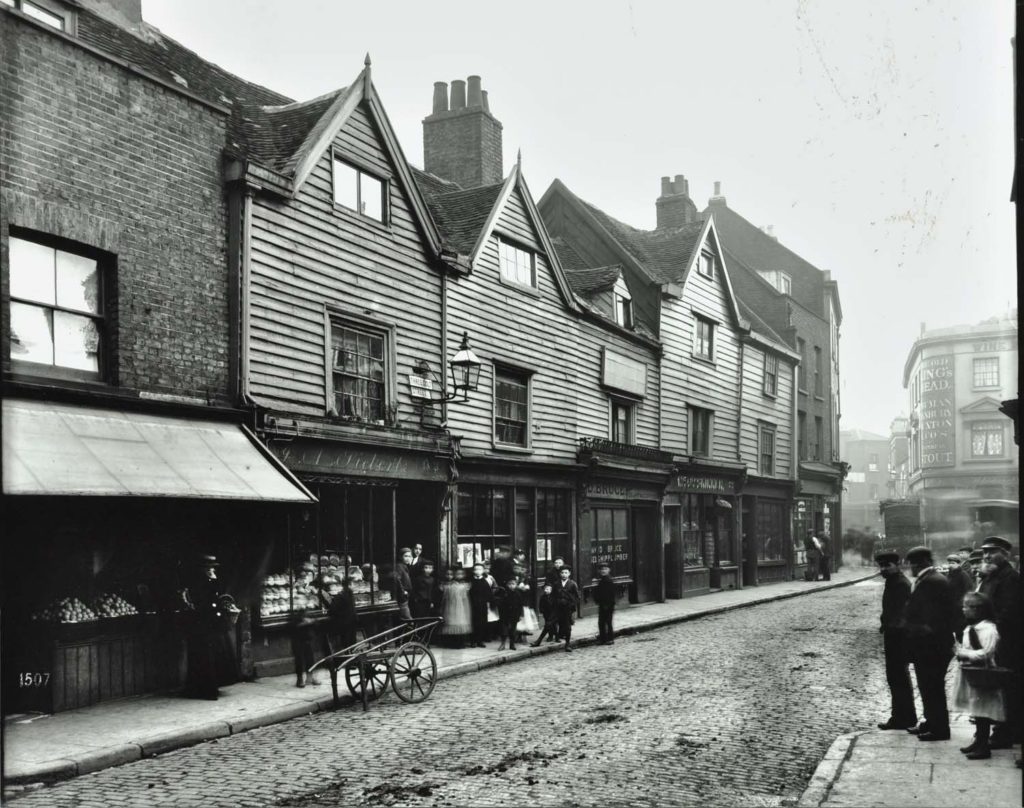

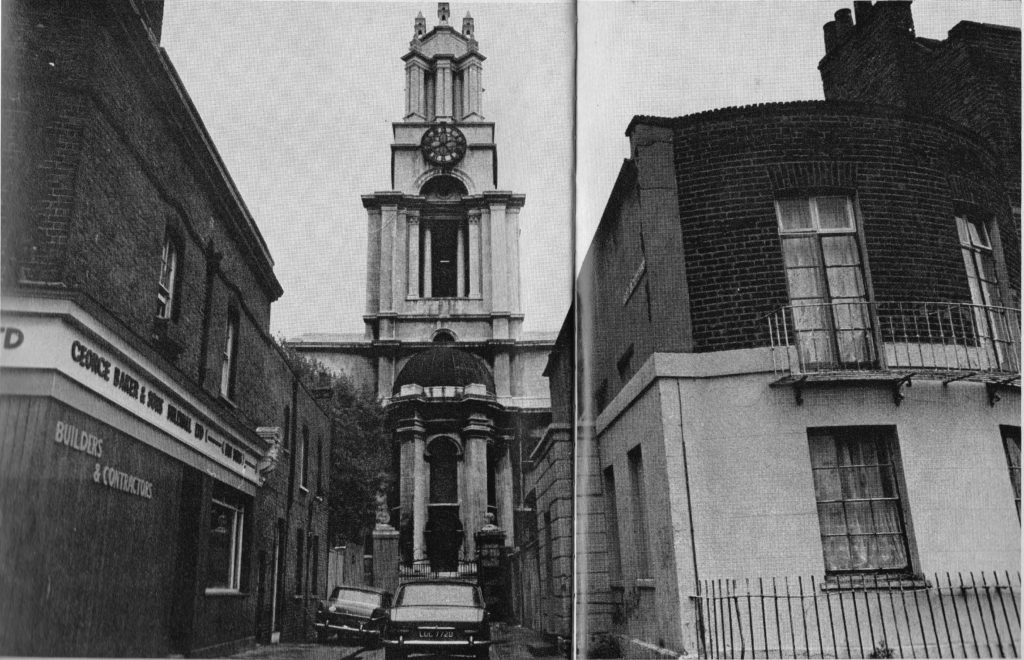

In this 1928 photo, we can see the power station as the white building, with a number of chimneys rising from the roof. Note that the chimneys are relatively low in height:

Photo from Britain from Above at this link.

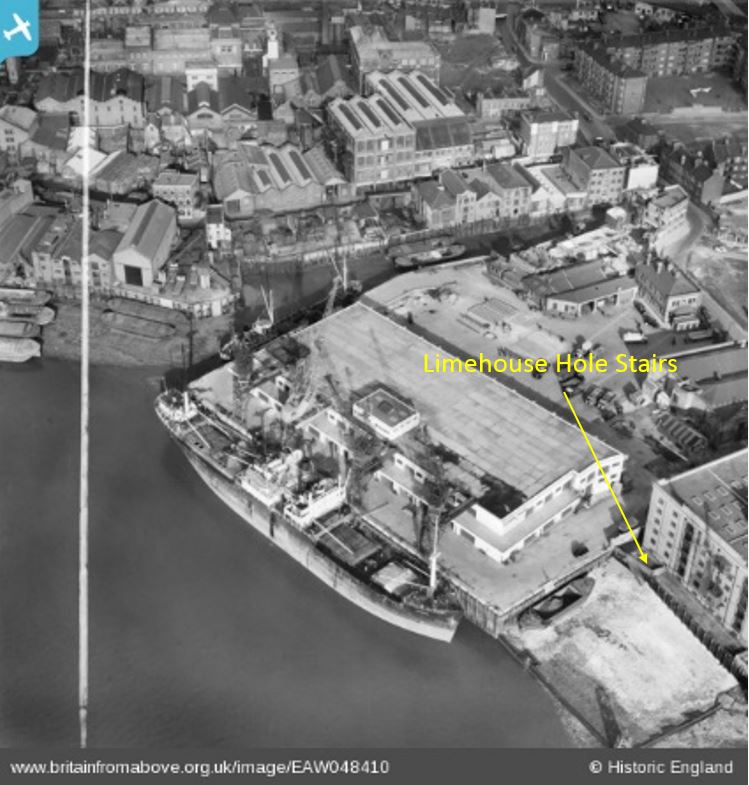

The low height of the chimneys did not help with the dispersion of smoke, gases and grit from the chimney so by 1937 a much taller chimney had been built, which can be seen in the following 1949 photo and is the chimney seen in my father’s photo:

Photo from Britain from Above at this link.

There was a rather glowing report about the new chimney in the Evening Telegraph and Post on the 2nd of August 1937:;

“An Almost Invisible Chimney – There is nothing mars a city more than unsightly chimneys sprouting from factories and power stations. London’s East End must have hundreds of these chimneys, which are, of course, necessary to carry away dangerous smoke and fumes.

There is, however, one chimney in London, its 354 feet making it one of the highest in Britain, which cannot be called unsightly, for it cnnot be seen a mile away. It is situated in Limehouse, and is part of the Stepney Power Station.

The reason for its invisibility is that it is constructed of square bricks, some brown, some a light creamy colour. At close quarters it looks spotty, but from the distance it seems to have no real colour of its own, and is just a faint shadow on the sky.”

I know for certain that it could be seen from more than a mile away, as the chimney appears in other photos taken by my father, and the “light creamy colour” would have turned dark in a short time due to the level of pollution in the air in the industrial West End of London.

For example, this is my father’s photo of the view from the east of King Edward VII Memorial Park in Shadwell, and clearly shows a very visible chimney rising above Stepney Power Station:

Stepney Power Station would continue in operation until 1972 when it was decommissioned.

During the 1950s and 1960s large new coal and oil fired power stations had been build along the Thames, and a distribution network connected London up with the rest of the country, so there was no need for small power stations in congested areas of London.

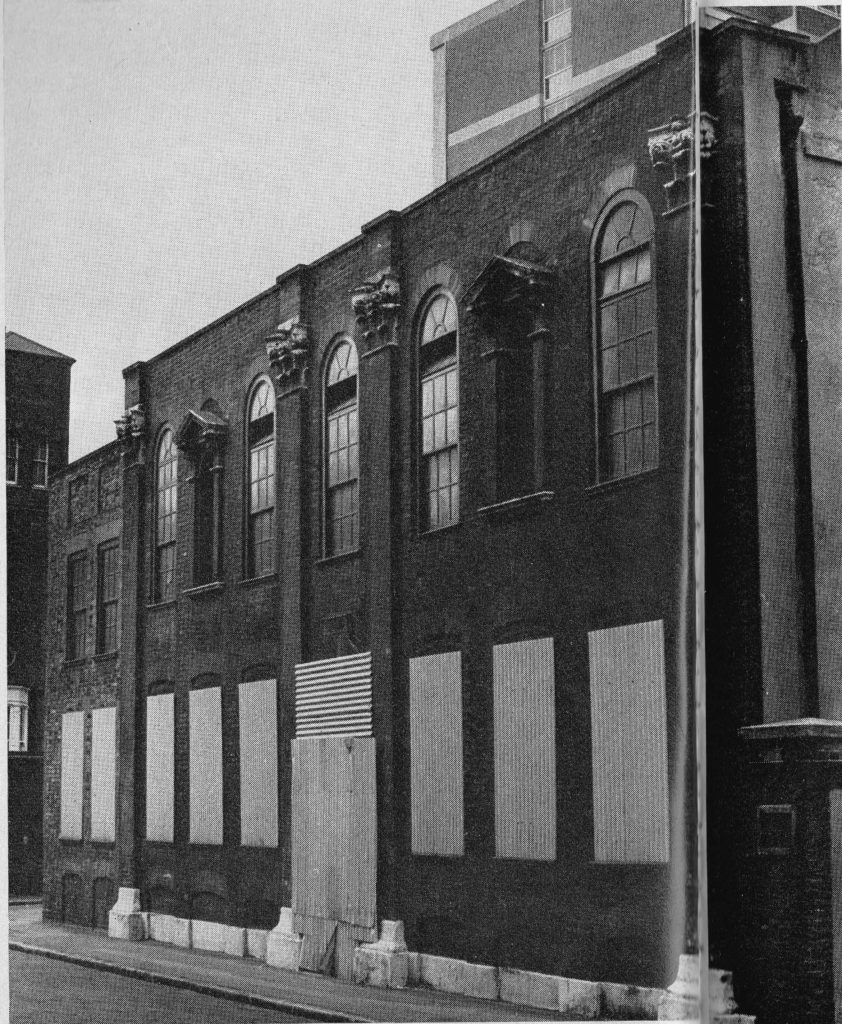

All that remains today of Stepney Power Station is the coaling pier. The buildings and chimney were all demolished years ago, and the building that now occupies the majority of the site is the Watergarden complex of apartments.

This is the view of the Watergarden apartments facing onto Narrow Street:

Stepney Power Station was instrumental in providing electricity to the factories, warehouses, docks and homes of the borough, and in 1917, Stepney had entered into an agreement with Bethnal Green Council, under the London Electricity Supply Act of 1908, to help develop and supply electricity in Bethnal Green.

The growing dependence on electricity can be seen by the impact that failures in supply had on the local area.

On the 8th of May, 1926 it was reported that:

“LIGHT CUT OFF, London Hospitals Have To Stop X-Ray Work: Three important London hospitals are still without electric current owing to the Stepney power station cutting off the supply. They are the London Hospital, the Whitechapel Infirmary, and the Whitechapel Dispensary for the Prevention of Consumption.

The work of these hospitals becomes more and more hampered by the loss of electrical power, and all X-ray has had to be stopped.”

And on the 27th if July, 1955, the Daily Herald reported that:

“POWER FAULT BLACKS OUT HOSPITALS: Three East London hospitals and the whole borough of Stepney were blacked out last night by a four-hour power failure.

It was the third in a week, and the third time cinema audiences get their money back. Police were sent in vans to all major crossings because traffic lights failed.

And while engineers sweated at Stepney power station, hospitals, homes and public houses switched to candles.

At the London Jewish Hospital the water supply failed too. It is kept up to pressure by electric pumps.”

From the London Daily Chronicle on the 22nd of August, 1922:

“STEPNEY IN DARKNESS – Two Men Injured at the Electricity Works: Two workmen named as Tindall and Armstroong were injured last evening in a mishap at Stepney Borough Council’s electricity generating station in Narrow-street, Limehouse.

The switchboard burst into flames, and the two men sustained burns in trying to put out the fire. Their injuries, however, were not serious, and after treatment at Poplar Hospital they were allowed to go home.

For a time part of the district was deprived of Light and Power.”

The view today, looking into the Watergarden complex from Narrow Street, into what was the core of the power station:

The view from the west – no coal dust, dirt, smoke or grit covering Limehouse today:

To the west of the power station site was Shoulder of Mutton Alley, which can still be found today, as can be seen in the following photo where the power station would have been on the right, and a paperboard mill on the left, with the power station chimney being at the far end of the street:

Walking along Narrow Street today, it is hard to imagine just how much industry there was along these now quiet streets, along with the noise and dirt which these industries generated. In just the above photo there was the power station and a paper mill on opposite sides of the street.

Stepney Power Station does help tell the story of how electricity came to London, and became an essential part in the ability of the city to operate in the modern world.

The Cyril Jackson school is still in Limehouse, however it has moved slightly east to a site along Limehouse Causeway, where today the children breath much cleaner air than their predecessors.