Three different subjects in this week’s post, but they all have a common theme of time – change over time, how centuries old data can be interpreted in modern ways, and how the future always develops in a way we can never foresee, starting with:

The 1803 Table of Watermen’s Rates

In last week post on Pageant’s Stairs, one of the references I included to the stairs, was the Watermen’s rates for taking you from London Bridge to the stairs in 1803, according to the “Correct Table of the Fares of Watermen, which has recently been made out by the Lord Mayor and Court of Aldermen”, as published in the Evening Mail on Monday the 16th of May, 1803..

The table included the rates for a long length of the Thames, from Windsor to Gravesend, and in my nerdy way of looking at stuff like this, I thought it would be interesting to interpret this data in a way we are familer with now, if we travel on London’s underground and rail network, where basic charging is by zone.

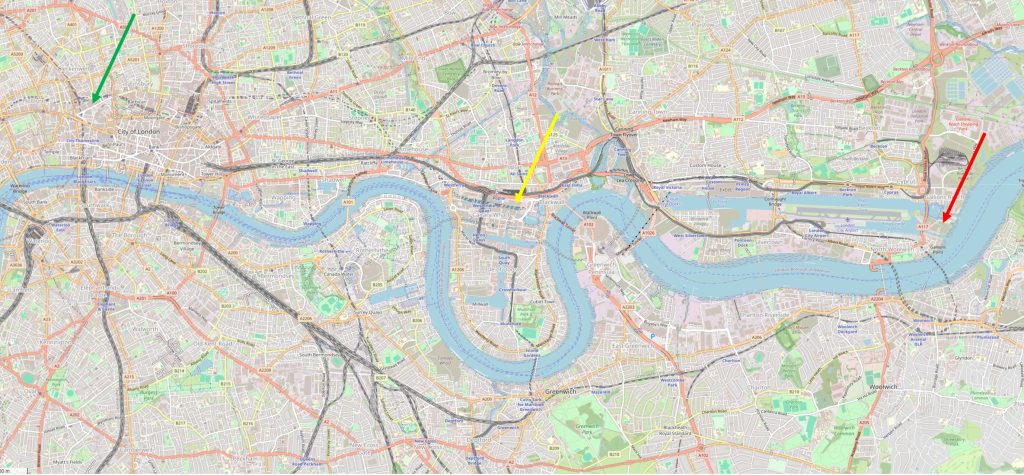

So taking the starting point of London Bridge, in the City of London, I mapped the rates in 1803 on to a map of the Thames, with each zone defining a specific Watermen’s price to row you from London Bridge.

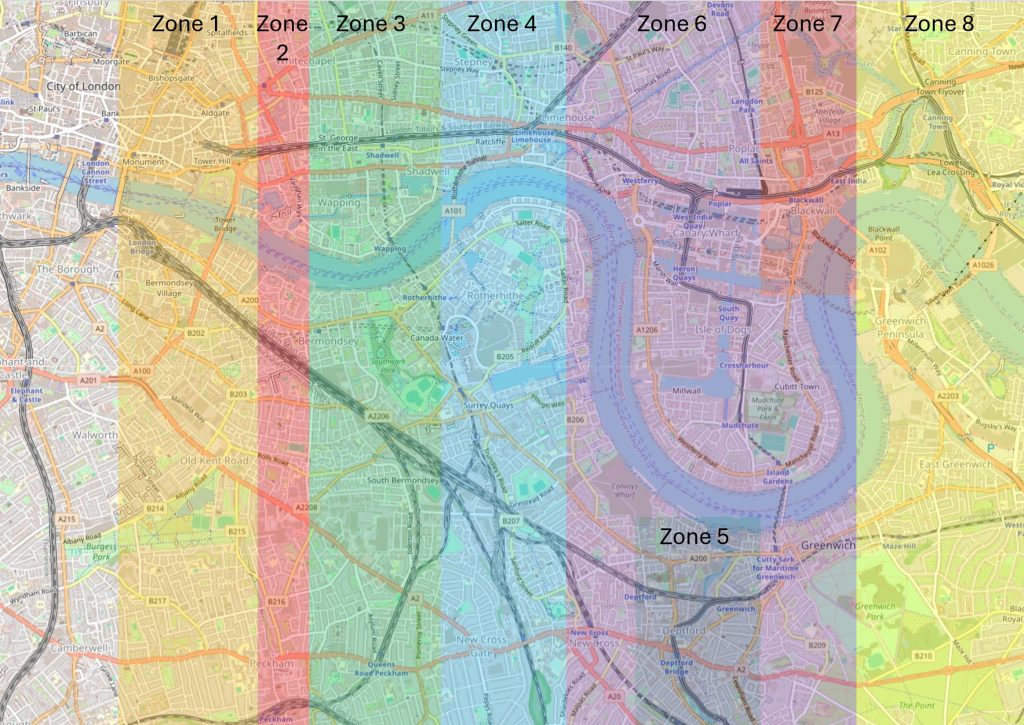

If you walked down to the river in 1803 to take a Watermen’s boat to your destination, then, as with an Underground station today, we can imagine the following maps pinned to the wall of the alley leading down to the stairs, the first map starting with the zones from London Bridge out to Blackwall (the actual zone pricing is after the maps). All base maps are © OpenStreetMap contributors:

London Bridge is the bridge on the left edge of Zone 1, and this is the starting point for a journey east along the river, and as with Transport for London’s (TfL), charging today, the price increases as the length of journey increases.

There are some strange charges, for example the whole of the Isle of Dogs appears to be in a higher priced zone (6), whilst Deptford has it’s own little zone (5), which is a lower price to the Isle of Dogs.

Displaying data in this way does make some huge assumptions. For example, with the Isle of Dogs, the 1803 table does not specify where on the Isle of Dogs the priced journey would end, so as stated in the table it looks to cover a large distance of river, from Limehouse round to Blackwall.

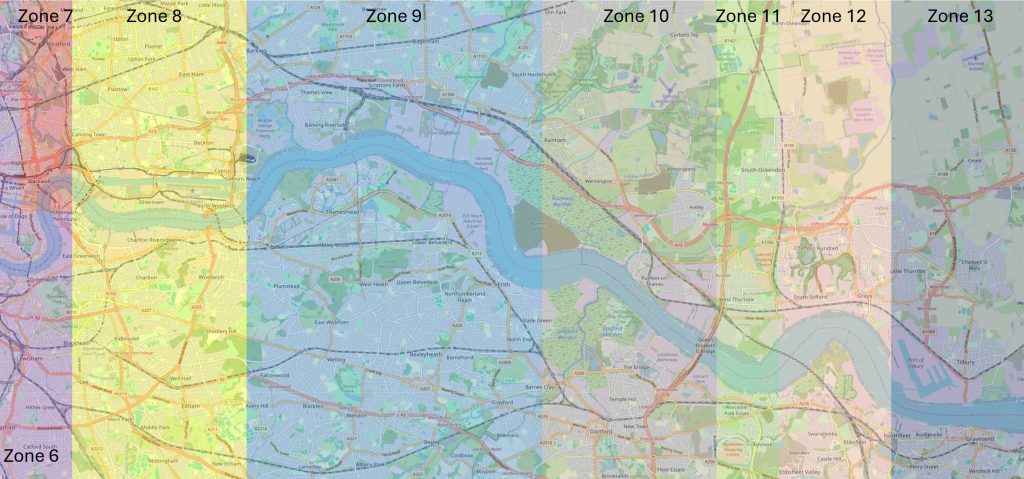

In the next map, we continue along the river to Gravesend, which, as Zone 13 is the final easterly zone, and priced destination in the 1803 table:

There seems to be no standard length of journey, so as can be seen in the above map, the length along the river of zone 9 is much more than zones 11 or 12.

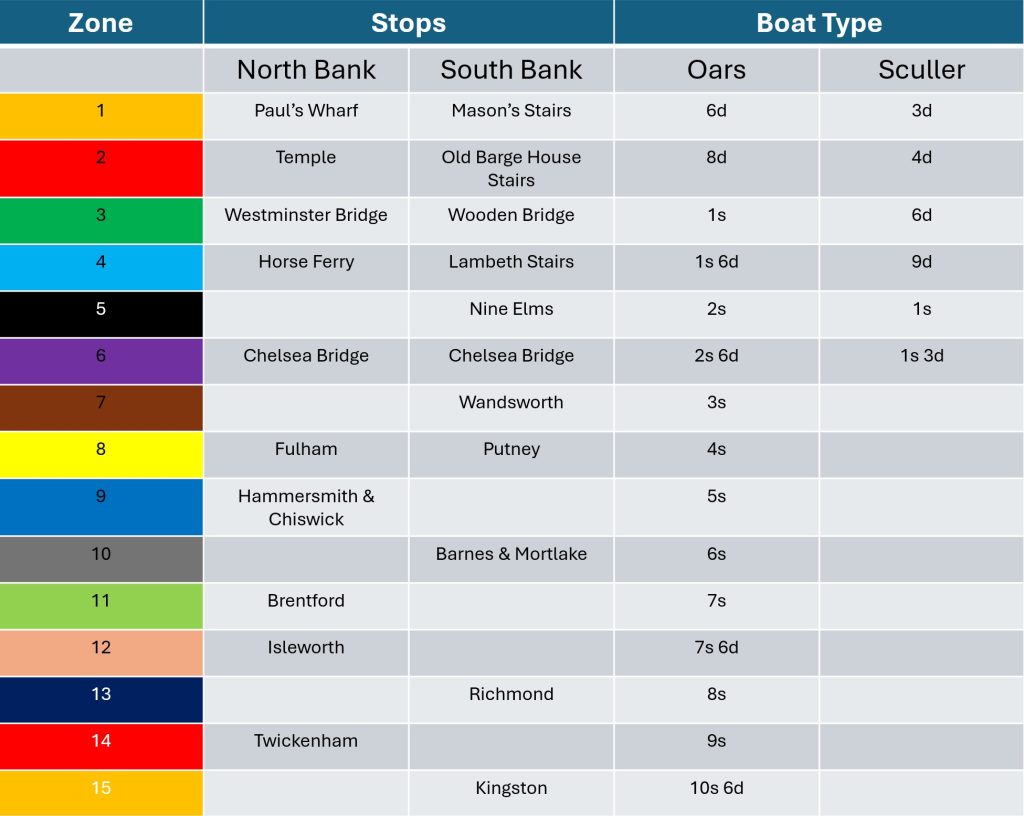

The pricing and sample locations within each zone is shown in the following table:

The best description of the difference between Oars and Sculler that I can find, is that with Oars, a rower is holding a single Oar in two hands, whilst with a Sculler, a rower is holding a pair of Oars in both hands.

I assume this explains the difference in pricing and why the price for a Sculler ends at the Isle of Dogs / Greenwich, as a boat could be rowed by a single person, using two oars, where with Oars, at least two people would be needed, each holding one oar on either side of the boat.

If this is wrong, comments are always appreciated.

The price for a Sculler ending at the Isle of Dogs / Greenwich is probably due to this being the physical limit that a single person could row along the river.

Regarding my earlier comment about the difference in length of the zones, the pricing table helps to explain this, with the jump in rates roughly rises in line with the distance travelled.

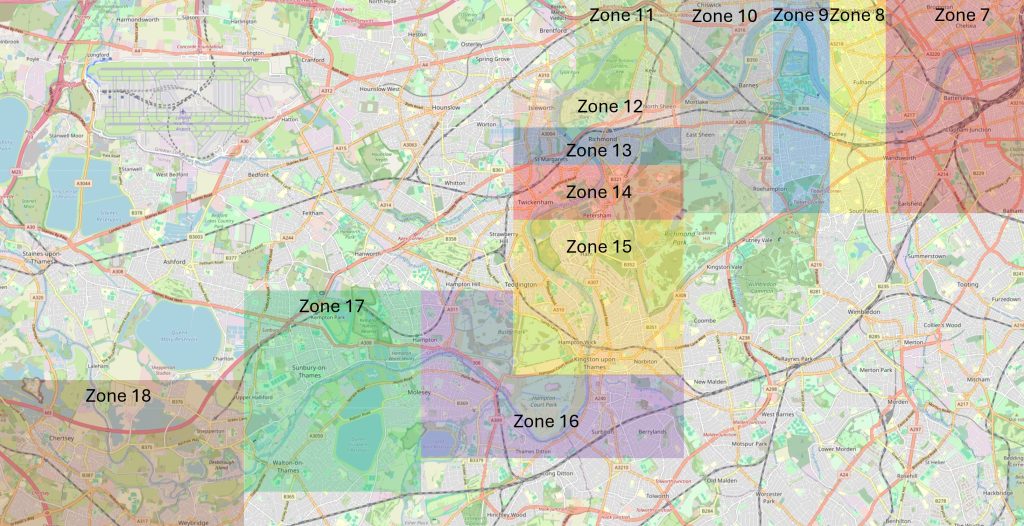

The above maps and table cover the east of the river. If you wanted to travel west, then there is a similar zone map hanging on the wall at London Bridge.

This is the first seven zones, from London Bridge up to Wandsworth:

Zone 6 covers the rate to Chelsea, and the following print from 1799 shows a party being rowed along Chelsea Reach. The boat is being rowed by Oars, as there are six rowers and three oars either side, so each rower is holding a single oar with both hands:

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

The above print shows several people being rowed by a team of six, and an obvious question is whether the rates apply to any number of passengers and number of rowers, and the answer is that there is an additional charge.

The 1803 Table of Watermen’s rates states that for the journey from London Bridge to Chelsea, for every additional passenger, there is an additional charge of 4d on top of the base rate, so in the above print there are ten passengers, plus two playing instruments who I assume also incur a charge as they are not Watermen.

The man at the back is wearing a Watermen’s badge on his arm, so presumably comes with the boat, so if the above boat had been rowed from London Bridge to Chelsea, the charge (see table after the next two maps) would have been 2s 6d base rate plus 12 times 4d (passengers plus musicians), so a total charge of 5 shillings and 10 pence.

Continuing along to Zone 18, Shepperton, Chertsey and Weybridge:

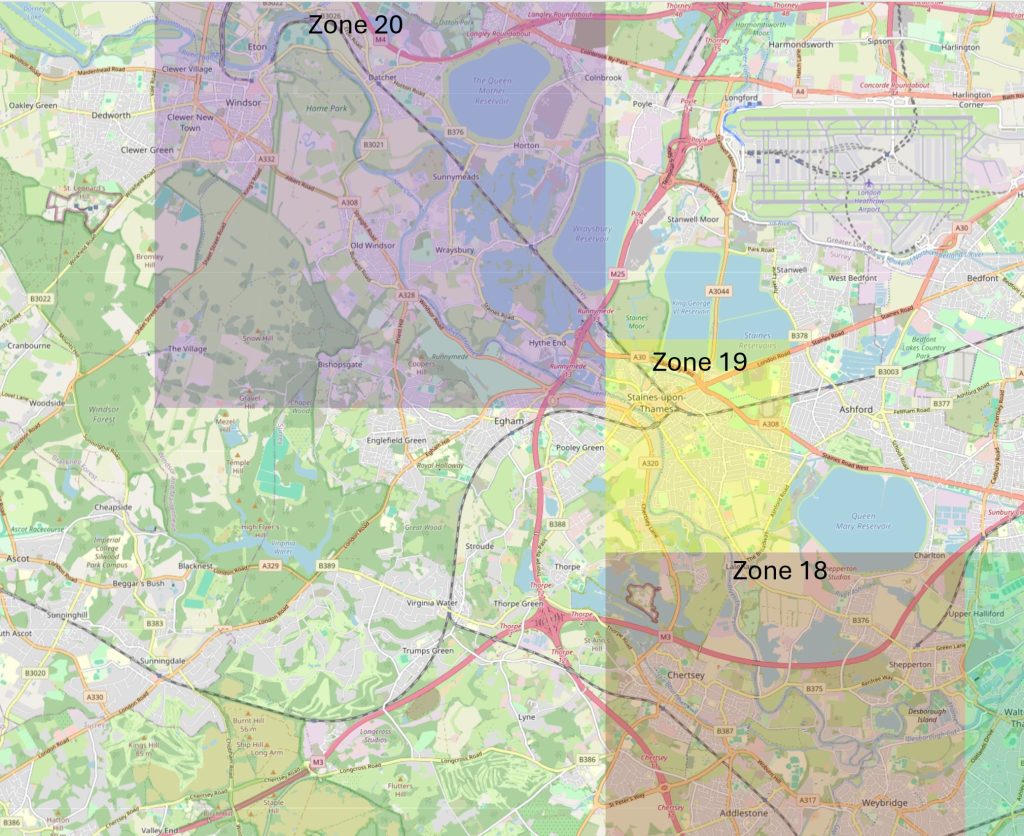

The final two zones, 19 and 20 run all the way to Windsor:

The table of rates travelling west from London Bridge:

The final five zones from Hampton Court / Town up to Datchet and Windsor:

The journey out to Windsor is considerable, and is way beyond the area of Port of London Authority’s responsibility, which ends at Teddington, the last westerly point on the tidal Thames.

Including Windsor in the Waterman’s rates must have meant there was demand for travel this far west, and is probably due to the times when the Monarch was based at Windsor Castle, so there would have been a need for travel from central London out to Windsor.

The price is also considerable for 1803 at 21 shillings, and on top of this there was a 3 shilling charge for additional passengers. Assuming the traveller from London to Windsor required a return trip, then the price would have been double, so not a journey that the average Londoner would have taken. Only one for the rich, and those on state business.

As well as listing charges for additional passengers, there were a number of other additional charges:

- If the journey is not a direct journey between places on the river, for example, if the journey is taking or collecting passengers from a ship, which may include waiting at the ship whilst passengers and luggage transfer, then the Waterman has the option of charging either the standard distance rate, or a time rate of 6d for every half hour for oars, and 3d for scullers.

- If the Waterman is detained at a stop by the passenger, for example having to wait at the destination stop whilst the passengers wait to disembark, wait to be met etc. then the Waterman can charge an additional 6d per half hour of waiting for oars and 3d for scullers.

- A journey directly across the river is charged at the standard rate of 2d, or if more than one person, 1d per person

- There were also standard rates between different stairs or landing places on the river, these were roughly the difference between the zones in which the different places were located. As an example, Wapping (Zone 3) to Greenwich (Zone 7), was 1 shilling 6 pence. The difference of the London Bridge standard rates of 2s 6d (to Greenwich) minus 1s (to Wapping, Zone 3).

- No more than six persons are to be carried in a wherry (the standard Watermen’s boat), and up to Windsor and Greenwich, up to eight in a passage boat (which I believe is a larger boat than the basic wherry).

One surprising omission is any reference to the state of the tide, as for a rowed or sculled boat, it would have been considerably harder rowing against the tide than rowing with the ride. It may be that this is expected to average out over a series of journeys with half being against the tide and half with the tide.

It would also be interesting to add a time column to the listing of rates, as the journey to the furthest reaches to the east and the west must have been considerable. This was reflected in the rates for the watermen, however it must have taken many hours to reach the furthest places in the table, and time of the journey would have been variable, depending on tide, weather, other river traffic etc.

Despite what seems to be well regulated pricing, there were challenges for the passenger who used the river to travel through London.

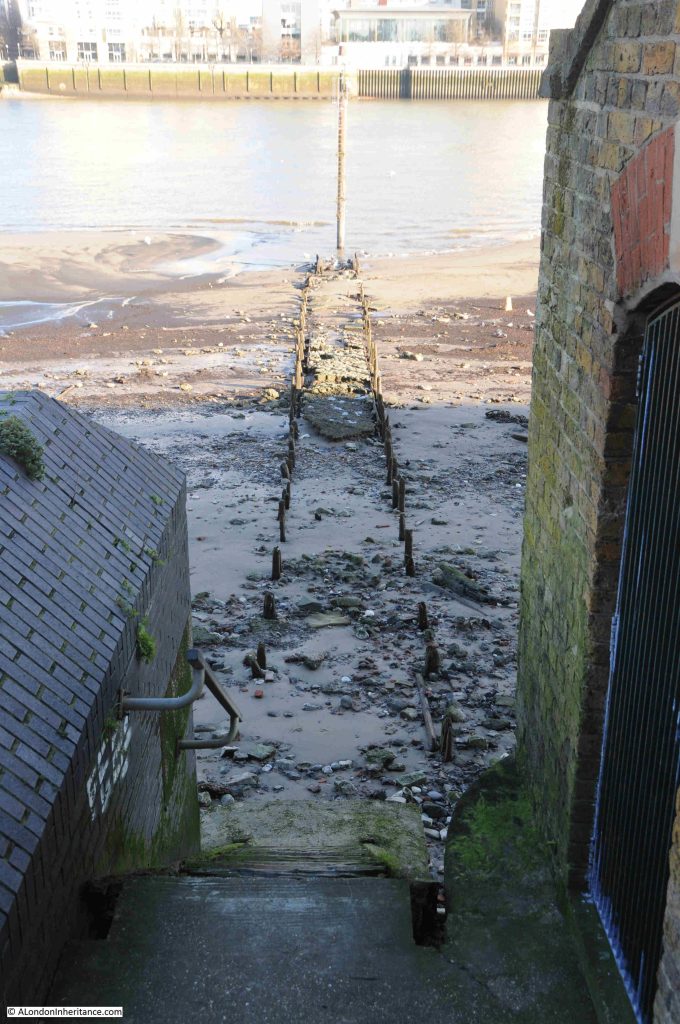

The following print dated 1816 from the Miseries of London series shows a woman walking down the steps at Wapping Old Stairs, presumably wanting a boat to travel to her destination, and being “assailed by a group of watermen, holding out their hands and calling Oars, Sculls, Sculls, Oars, Oars”:

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

The Watermen are wearing their badge on their arms to signify that they are a Waterman, and the following is an example of such a badge:

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

Not adhering to the rates would often result in being brought to court, for example in 1847, waterman John Thomas Jones was in court on a charge of overcharging a passenger 12s 6d for a fare that should have been 4s 3d. The Waterman was fined 20s.

Watermen also were at a number of risks, as well as the daily danger of rowing along a congested river, they were also valued for their skills, and were prized as recruits for the Navy.

A report in the London Magazine in 1738 on the need to crew several new naval ships, states that a “press” took place on the river, with 2,370 men taken and enrolled in the Navy, the majority of them being Watermen.

The 19th century saw a gradual decline in the need for a Watermen to row passengers along the river.

The growth of steam ships on the river, the growth of the railways, underground, improved roads, bridges etc. all made it easier to travel without the need to be rowed.

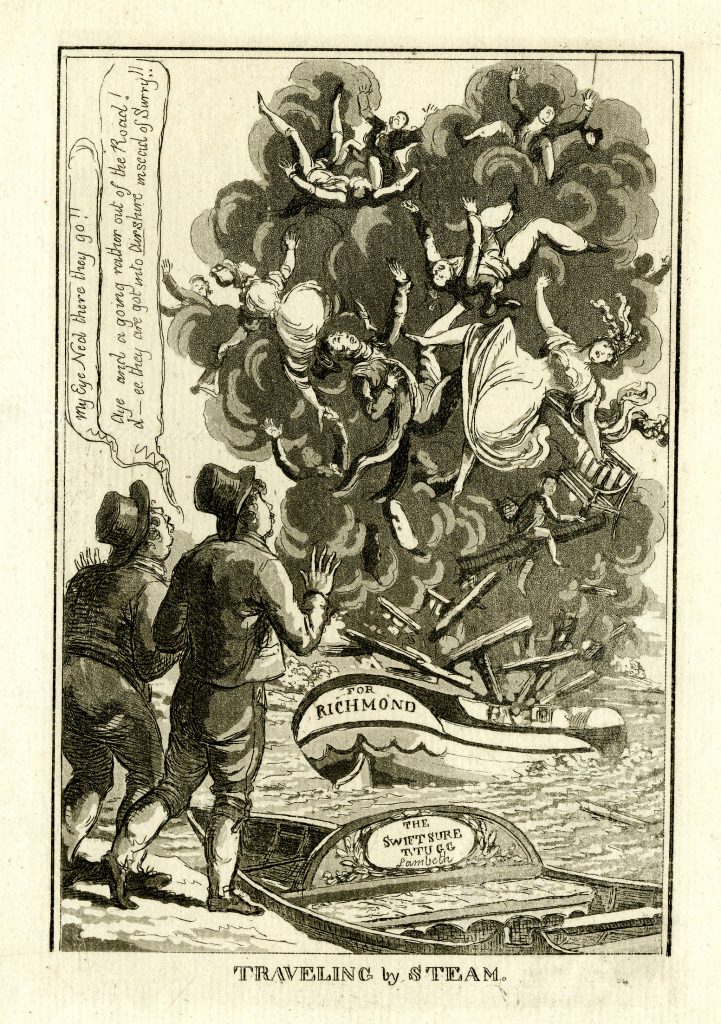

Steam powered boats started ferrying passengers along the river, although initially this method of transport was not always safe and reliable. The following print from 1817 titled “Travelling by Steam” shows two Watermen watching a steam packet boat exploding and throwing the boat’s passengers across the river:

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

The newspapers listing of the Watermen’s Rates were always dense columns of text, and showing these visually on a map, in a similar way in which TfL display underground and rail fares helps with understanding part of the rich life of London’s river.

One big difference between 1803 Watermen charges and today’s TfL charging is that in 1803 there was no capping of the daily charge, so in 1803, you would have been charged for each journey you would have taken on the river.

The Sunbeam Weekly and the Pilgrim’s Pocket – Shock and Outrage at the Evolution of the United States of America

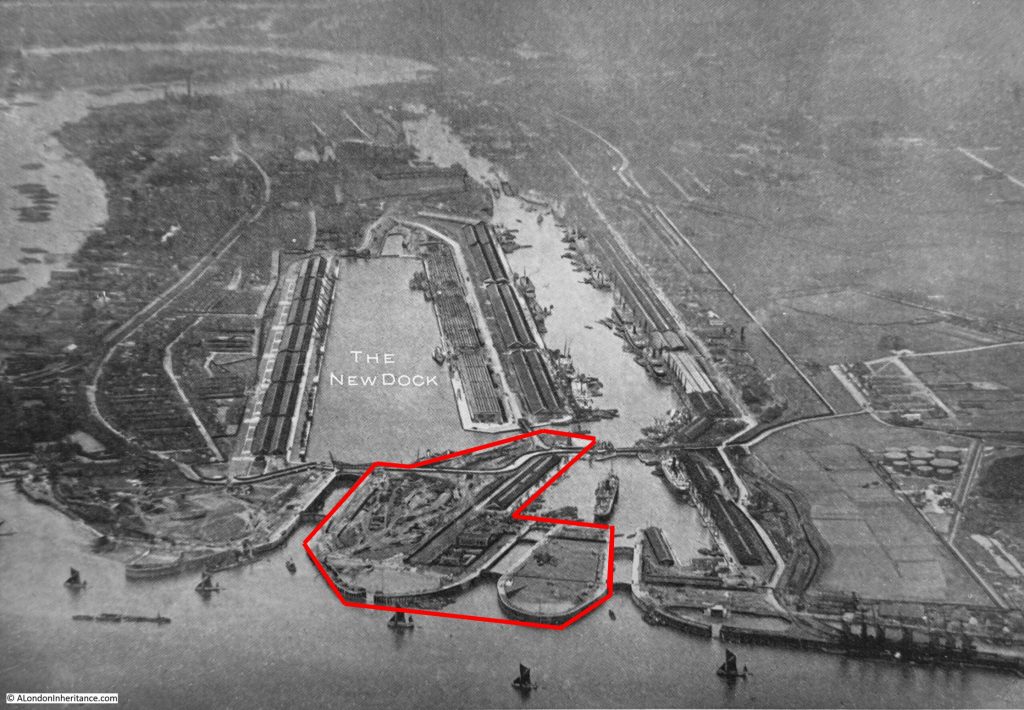

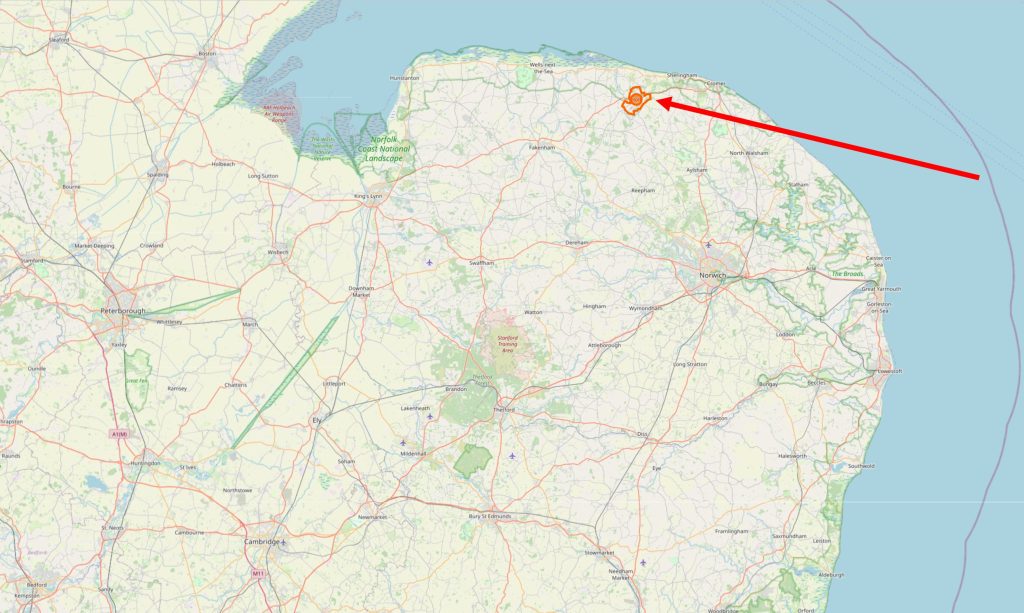

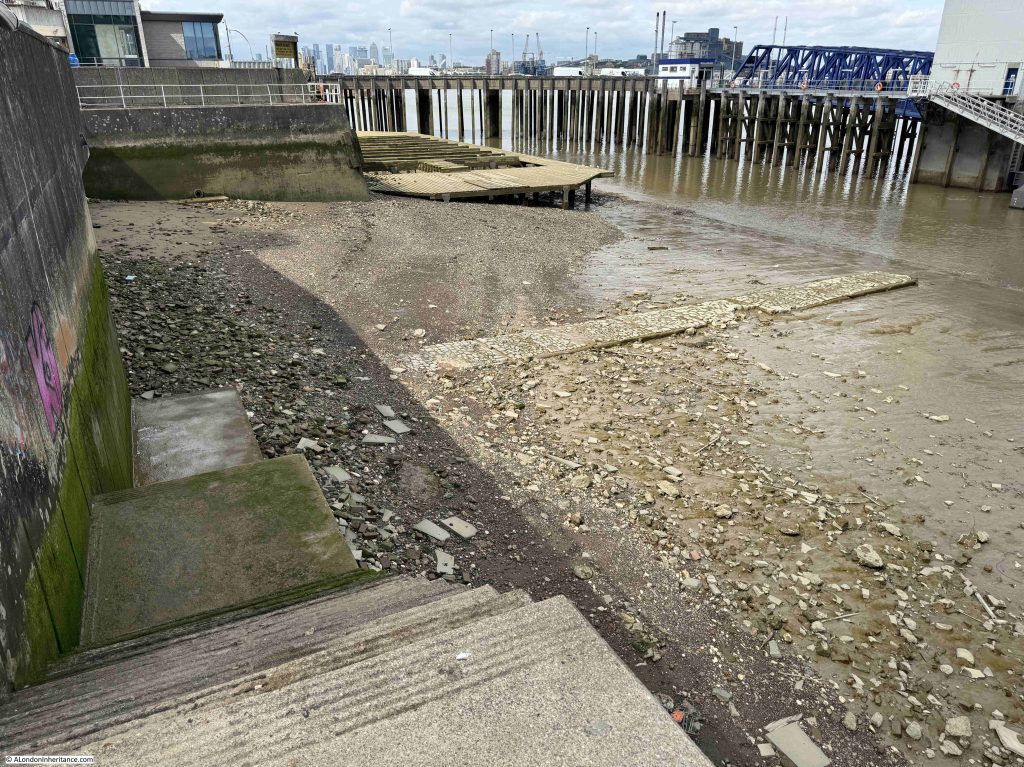

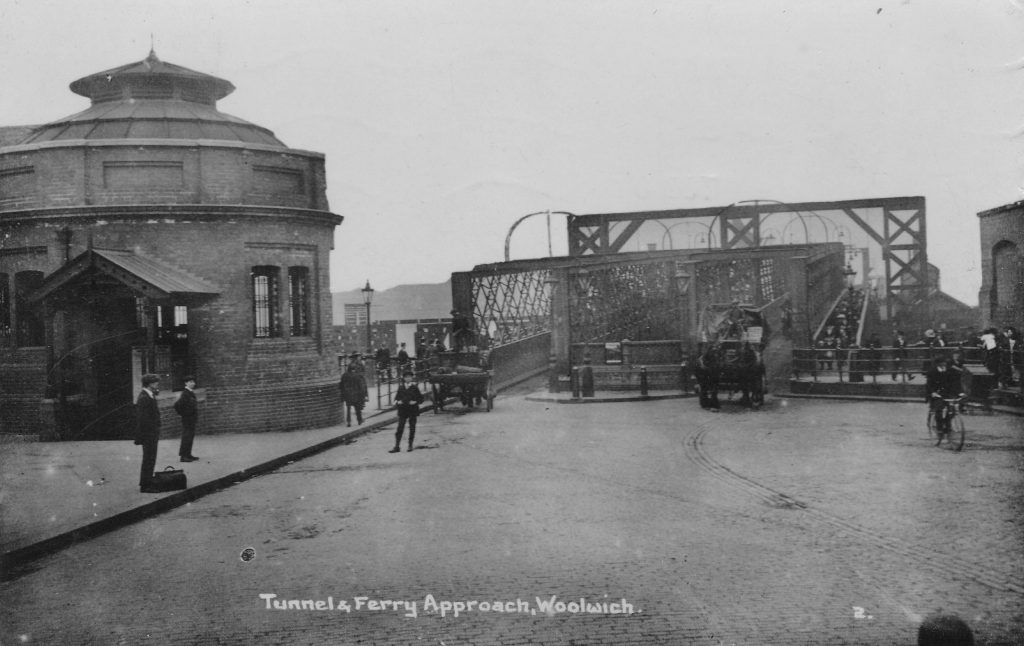

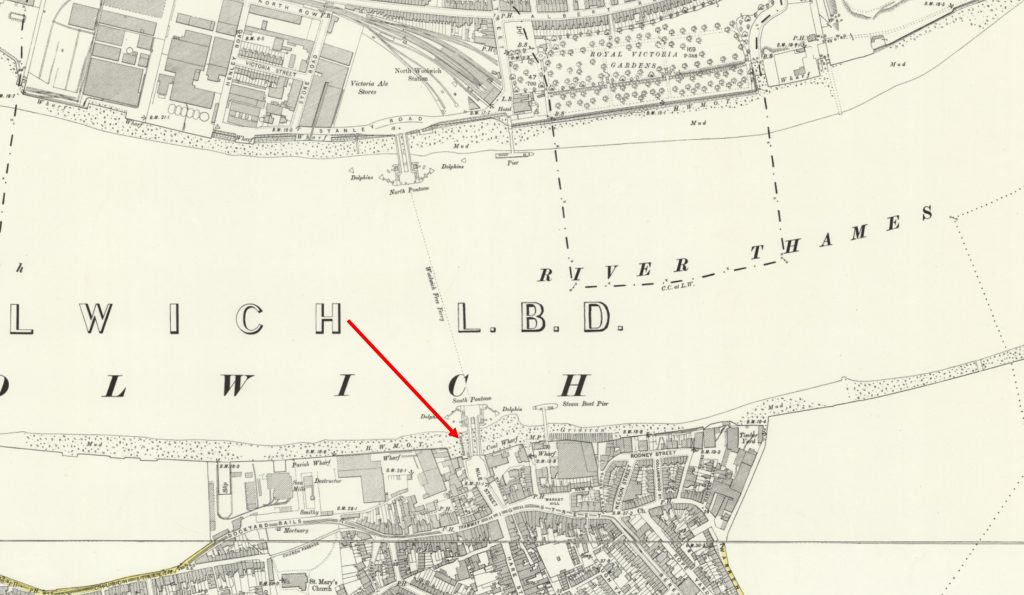

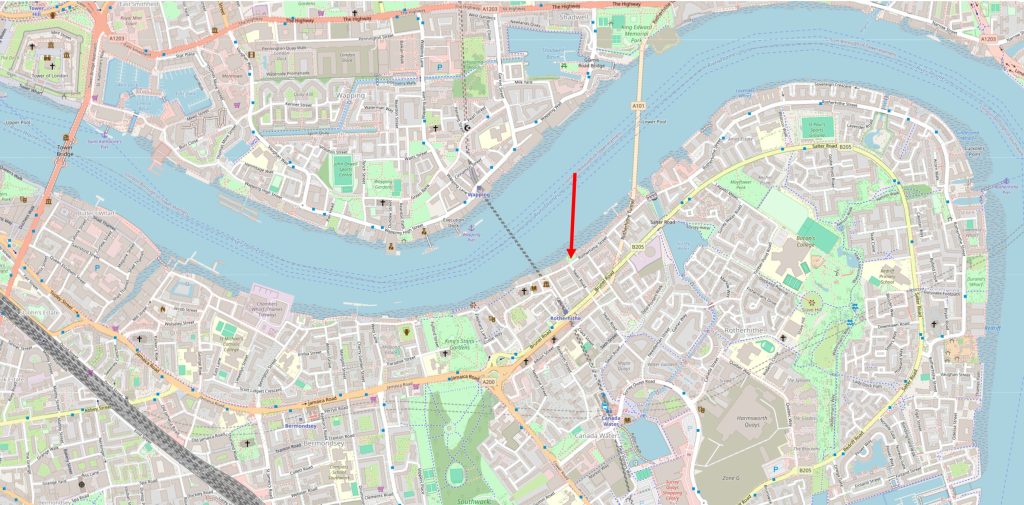

There is a wonderful statue at Cumberland Wharf in Rotherhithe, which is today a small area of open space alongside the river at the place indicated by the arrow in the following map:

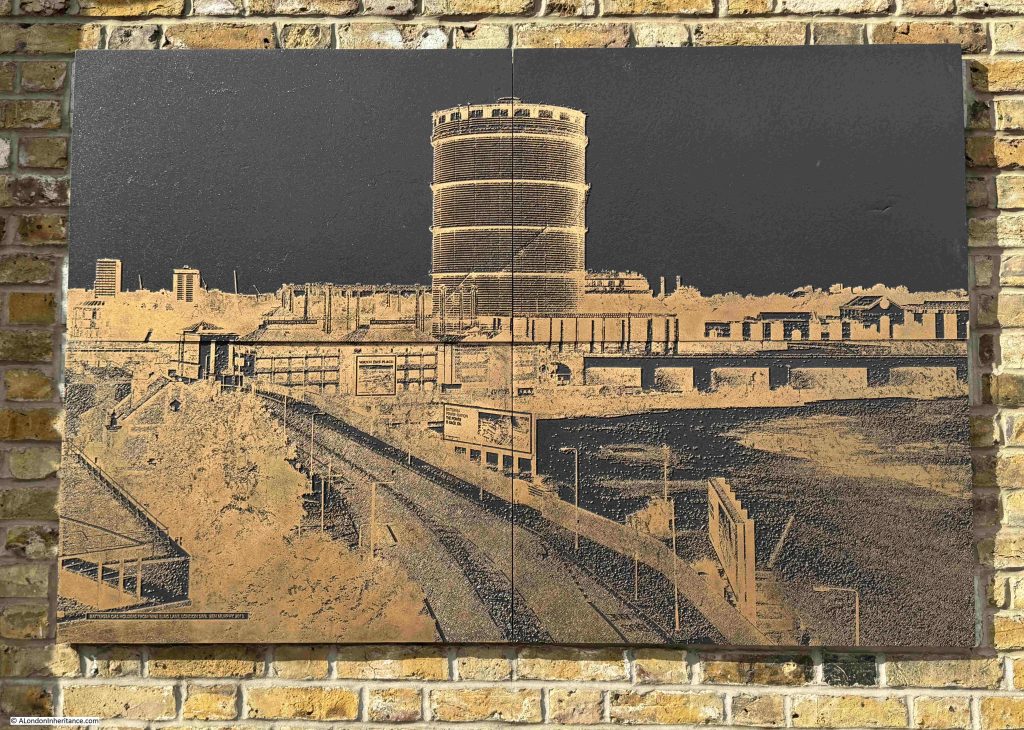

Once a wharf between Rotherhithe Street and the Thames, servicing a large granary across the street via conveyors which ran across the street in the photo below, and which shows the area occupied by Cumberland Wharf:

If you look to the left of the space, there is a walkway with a statue at the end, which is alongside the river:

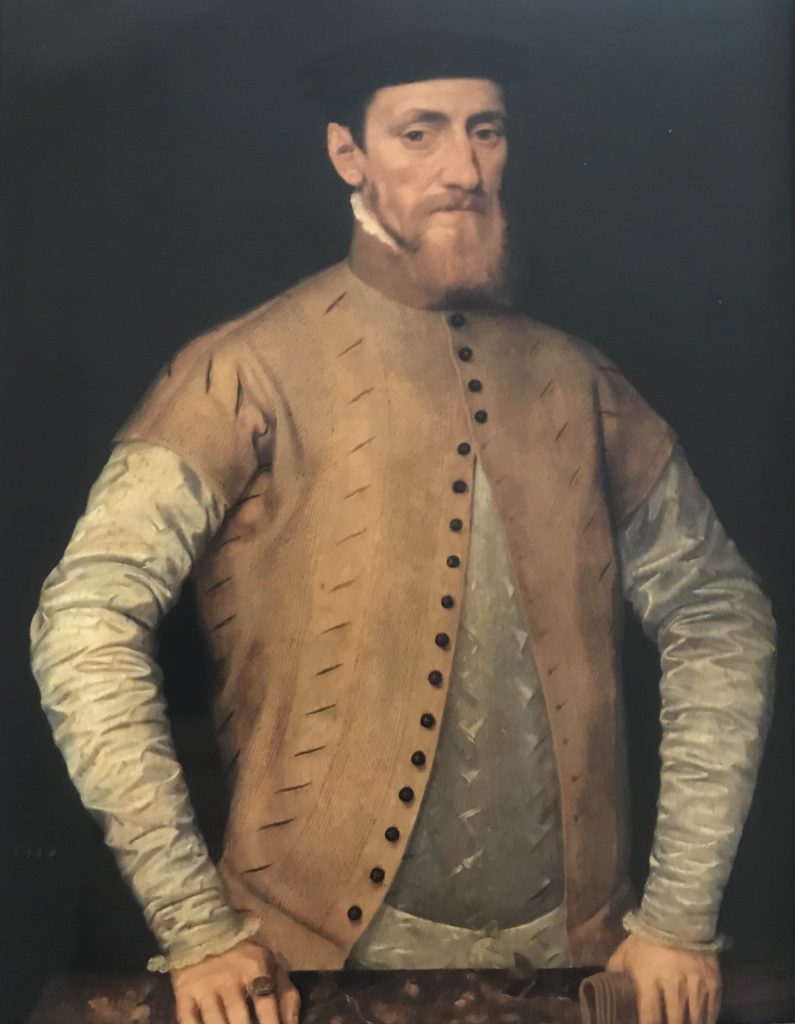

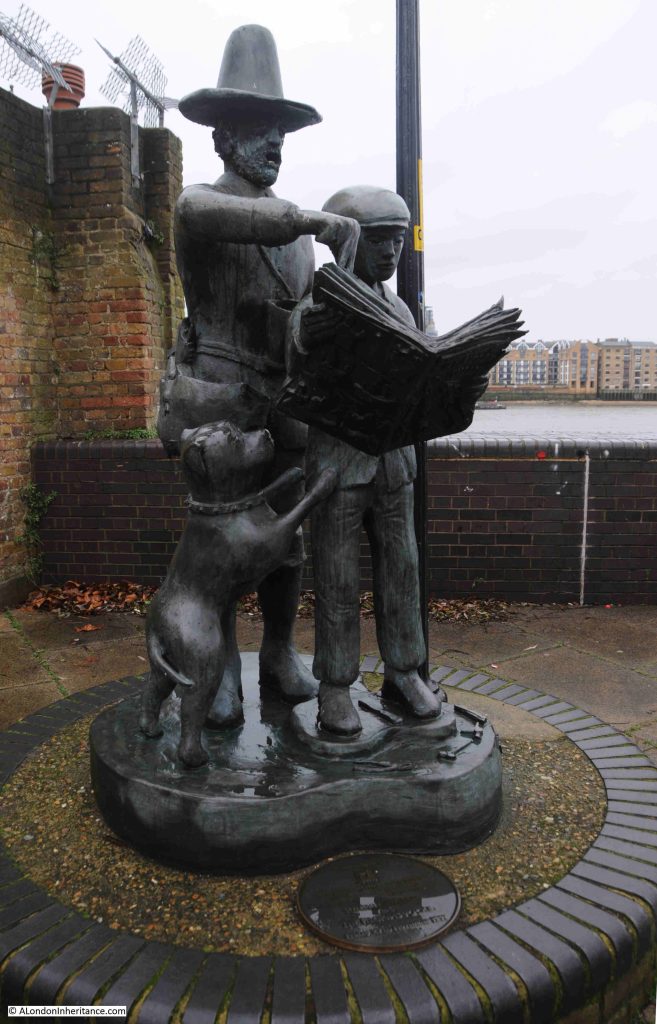

The statue consists of a taller figure – William Bradford, who was Governor of the New Plymouth colony in the United States for a number of periods between the years 1621 and 1657. The boy is in 1930s clothes, and represents a local boy reading a comic of the time:

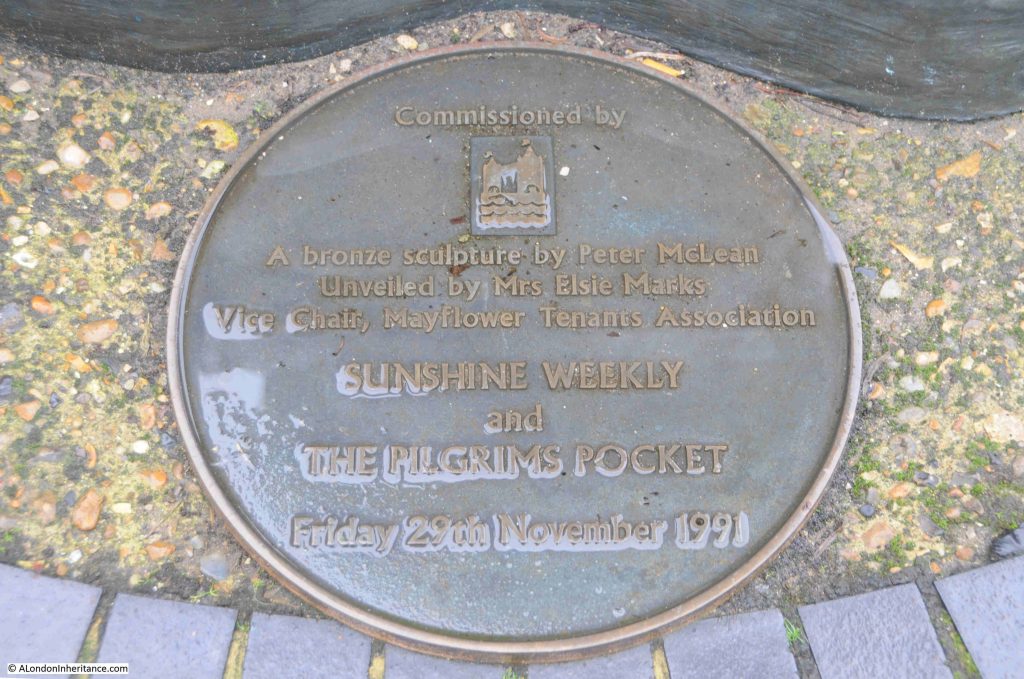

The work by Peter McLean dates from 1991 and is titled “Sunshine Weekly and the Pilgrims Pocket”:

William Bradford was one the Pilgrims who left Rotherhithe on the Mayflower in 1620. The ship sailed from Rotherhithe from the area around Cumberland Wharf, although not their last port of call in England, as they stopped off at Plymouth before crossing the Atlantic on a two month journey.

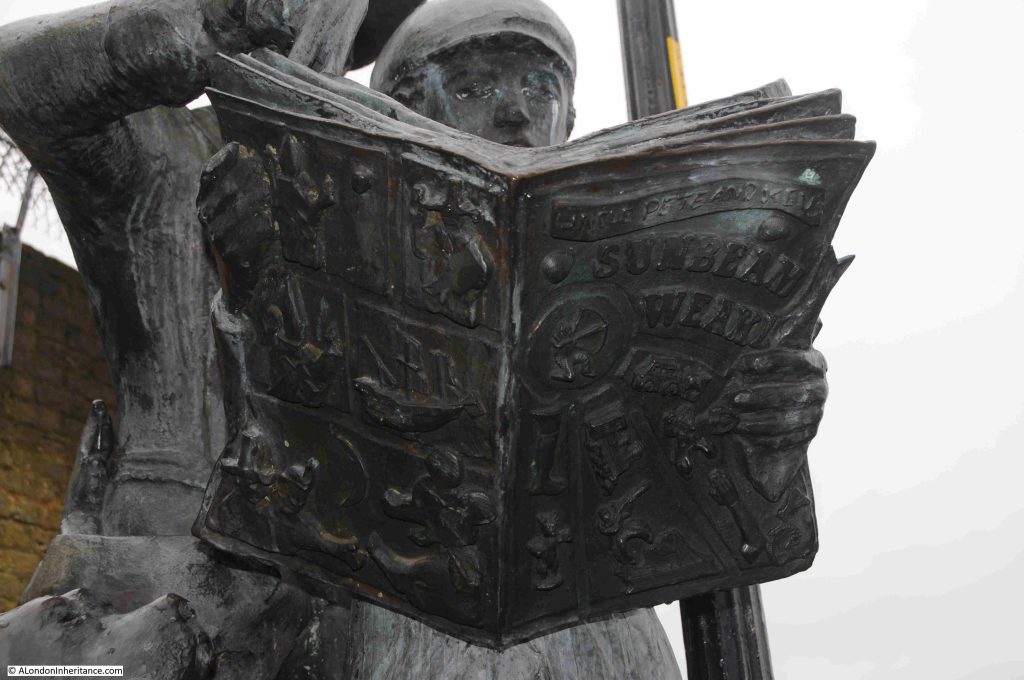

Bradford is looking over the boy’s shoulder at his comic with, as described in the adjacent information board, “a look of shock and outrage” as he turns the pages of the comic:

The Sunbeam Weekly was a comic from the 1930s:

Why was the Pilgrim William Bradford, who had a long career as the Governor of the Plymouth Colony at what is now Plymouth, Massachusetts, looking at a 1930s comic with a look of shock and outrage?

The reason is that the pages of the comic are showing how the United States of America has evolved since the Pilgrims landed in 1620.

(Sorry, the photo is slightly out of focus. It was grey, overcast, raining, breezy and cold).

The pages of the comic show the Statue of Liberty, an aeroplane, cars, a train, skyscrapers, the Space Shuttle and King Kong:

William Bradford was a Puritan, the strand of English Protestantism that believed that the Reformation had not gone far enough in ridding the Church of England of Roman Catholic practices. Puritans, and the clash between reformers. separatists and the established church would play a major part in the English Civil War and the Protectorate which would take place during the 1640s and 1650s.

I am sure Bradford would be absolutely shocked how the United States has developed in the 400 years since he was part of Plymouth Colony. I am not sure about the outrage, as Puritans were against Roman Catholicism rather than what can loosely be described as technical progress, however they were strict religious adherents (which is where stories about Christmas festivities being banned during the Protectorate, although in reality the vast majority of the population continued to celebrate).

The pocket of William Bradford includes some key symbols.

A 1620 A to Z of the New World, a lobster claw and fish to show the seafood that was key to the Pilgrims survival in the early years of the colony, and a cross which is symbolic of the religion that the Pilgrims carried to the new colony. There is a small US badge at the base of the cross:

The artist’s tools are shown at the feet of the statue:

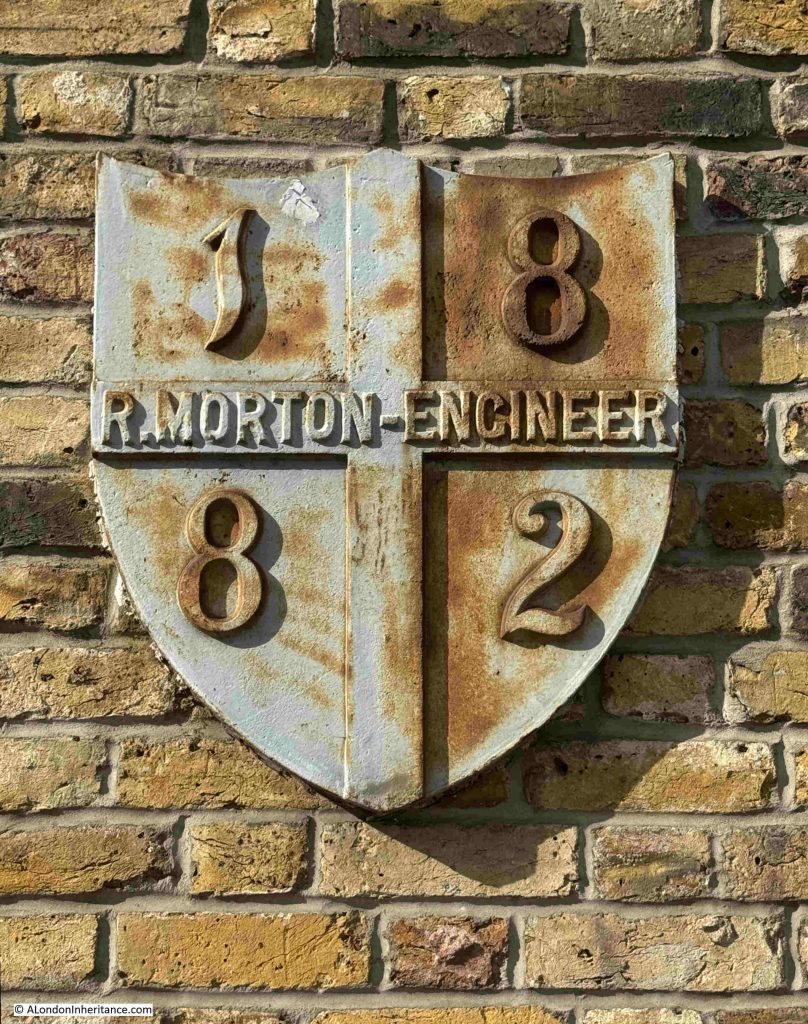

And along the edge of the base is the sculptors name and year the work was created:

I think this is a wonderful work of art.

I often wonder when looking at old photos, what the people in the photo would think about how the future has developed, as it is always in a different way to that expected at the time.

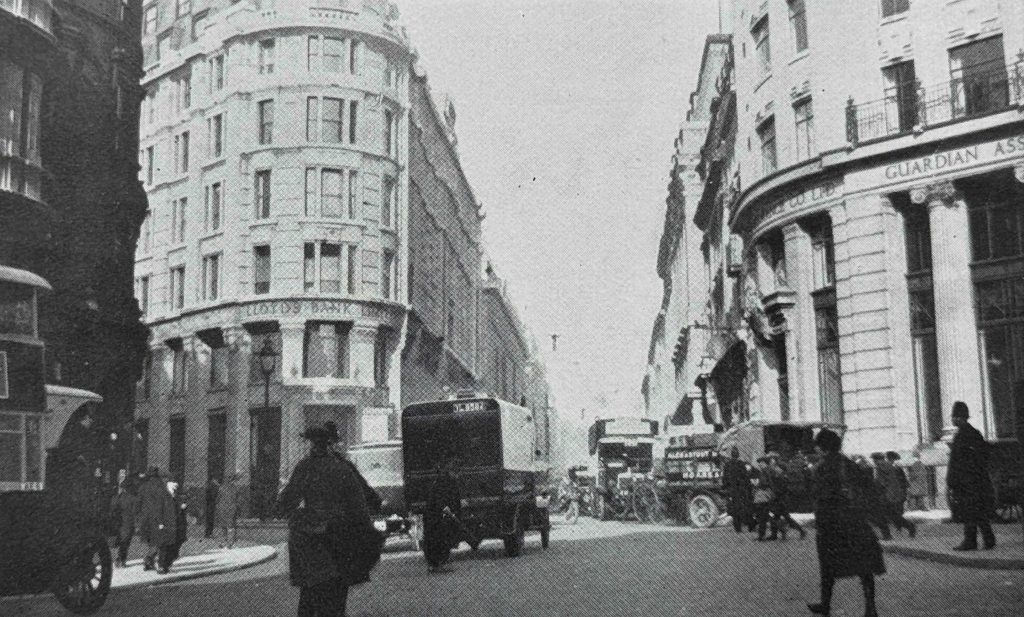

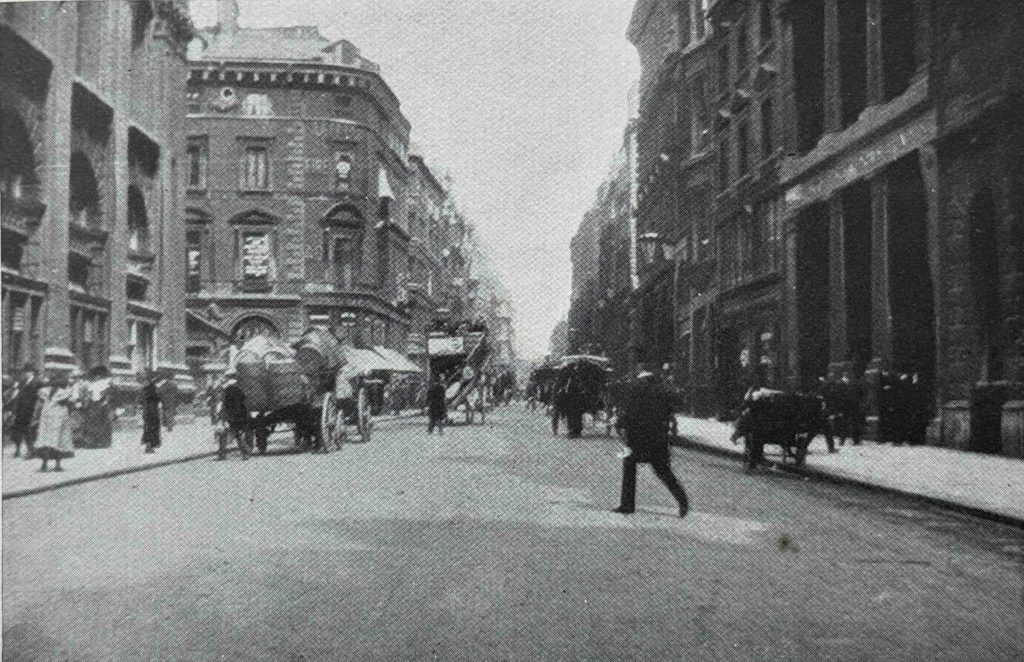

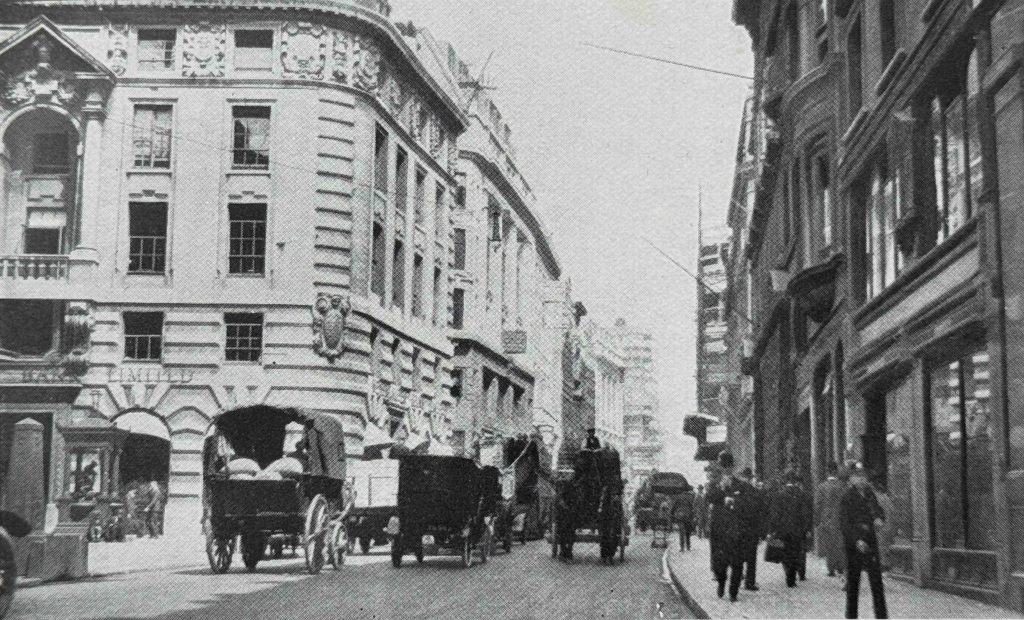

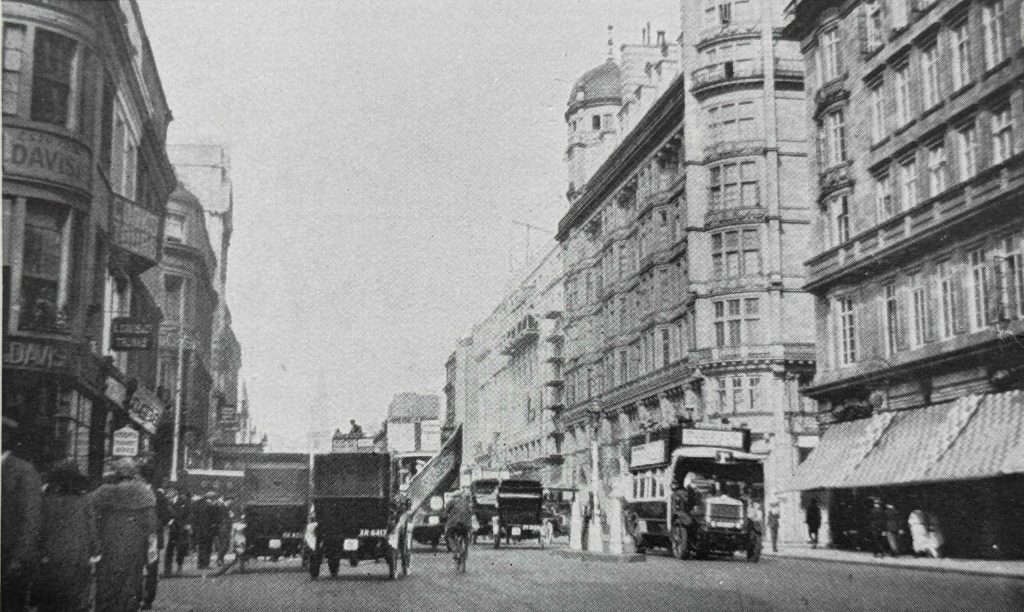

My father mainly photographed scenes rather than focusing on people, however whilst it is a gap of only 73 years, compared with the almost 400 years in the Rotherhithe statue, it would be interesting to see how those waiting for the 1953 Coronation procession in one of his photos, would look at the London of today:

If you walk the Thames path in Rotherhithe, or along Rotherhithe Street, stop at Cumberland Wharf to take a look at “Sunshine Weekly and the Pilgrims Pocket” and also consider that whatever we expect the future to be – it will almost certainly be very different.

And for the final look at a different aspect of time hopping, another of my first post of the month looks at the resources available if you are interested in discovering more about the history of London:

Resources – Tallis’s London Street Views

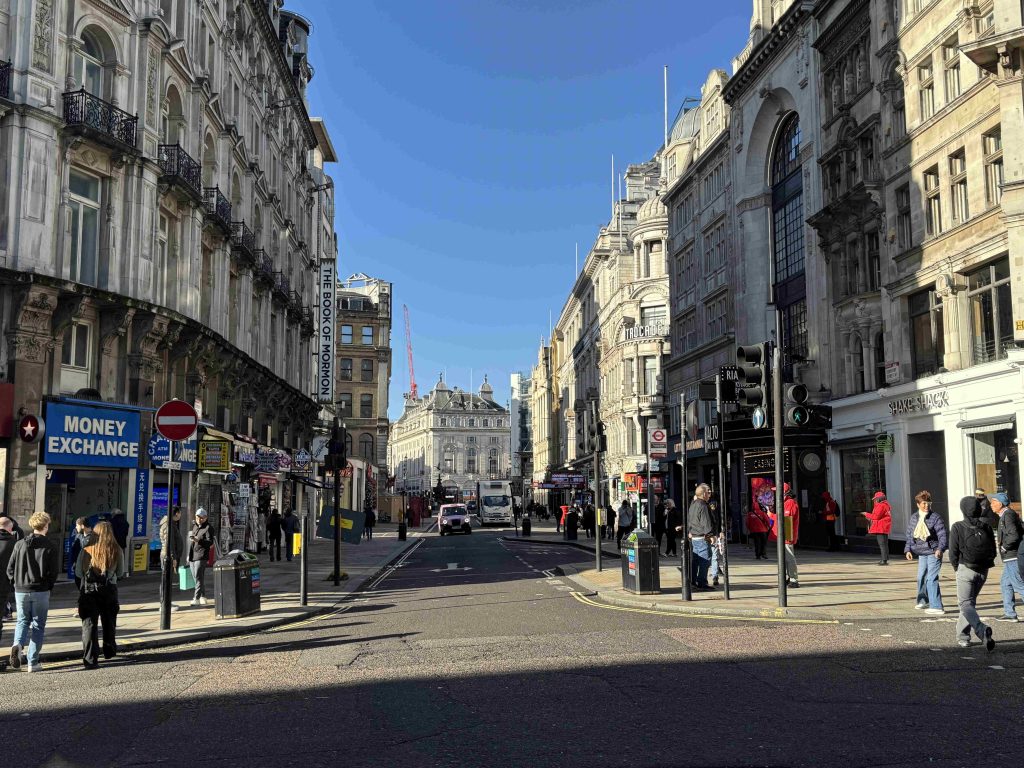

Today, if you want to look at a street and see the buildings and businesses along the street you can use Google Street View.

Imagine if it was possible to do this for the years long before photography and Google made this possible, well for the years between the late 1830s and early 1840s there is a Street View available, which whilst being drawn, and not as comprehensive as Google still provides the opportunity to take a virtual walk along a London street.

This is Tallis’s London Street Views.

(Before going further, the version of Tallis’s Street Views available on line is the 2002 reprint of a London Topographical Society (LTS) print of the street views. The copy was held by the University of Michigan and digitised by Google, and is made available online by the HathiTrust, a US organisation who describe themselves as:

“HathiTrust was founded in 2008 as a not-for-profit collaborative of academic and research libraries now preserving 19+ million digitized items in the HathiTrust Digital Library. We offer reading access to the fullest extent allowable by U.S. and international copyright law, text and data mining tools for the entire corpus, and other emerging services based on the combined collection.”

The HathiTrust have made the work available under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives.

It is difficult to know the true copyright status of documents such as this, when you have very large organisations such as Google digitising vast amounts of works and many, often US based organisations making these fully available online, a situation which I expect is going to get more problematic in years to come).

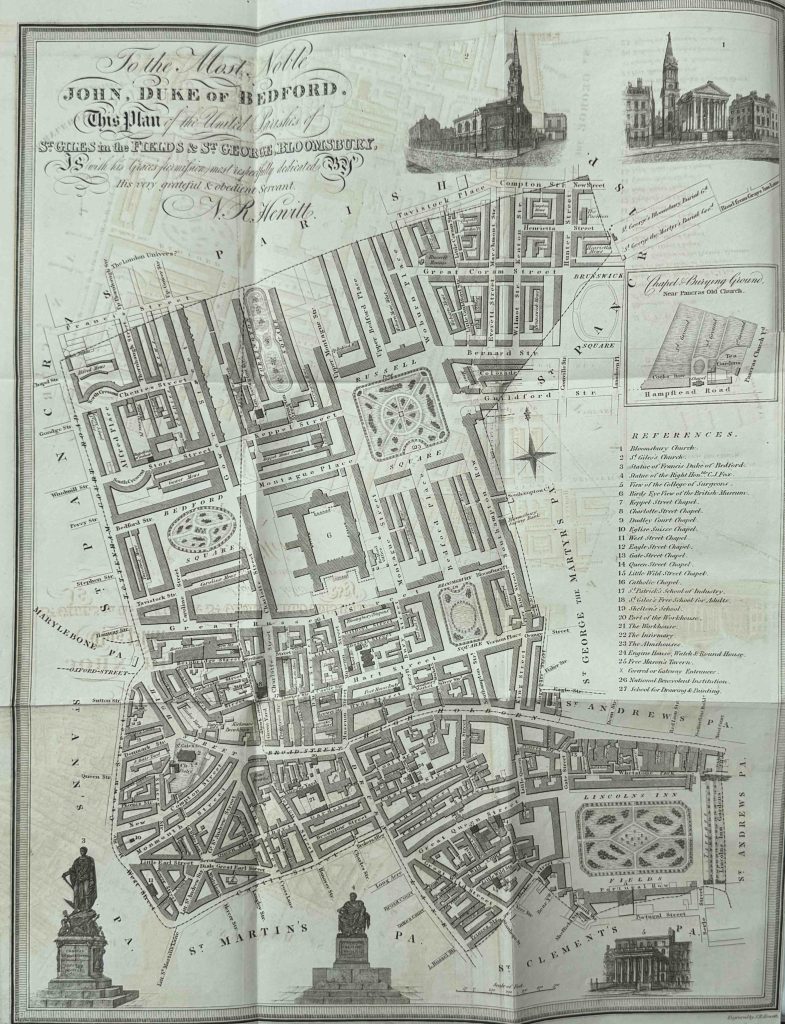

John Tallis was the publisher of the Street Views. He was based at 15 St. John’s Lane, near St. John’s Gate.

Tallis was a prolific publisher of prints covering people (real and fictional), actors, landscape scenes, buildings, places etc. As well as multiple prints of London, he published images of other places, for example the following print of Margate Pier and Harbour:

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

Initially, Street Views was published in parts before being published as a complete set.

The following, from the Gloucester Journal on the 21st of July 1838 is typical of advertising for the Street Views:

“TALLIS’S LONDON STREET VIEWS. For the sum of Three-half-pence, you can purchase a correct View, beautifully engraved on steel, and drawn by an artist of great talent, of upwards of One Hundred Houses, with a Street Directory, or a Key to the Name and Trade of every occupier to which is added a Map of the District, and an Historical account of such Streets, Courts, or public Buildings worth recording.”

The Street Views obviously does not cover all the streets of London, but does provide comprehensive coverage of the major thoroughfares of central London, along with many of the smaller streets, particularly in the City.

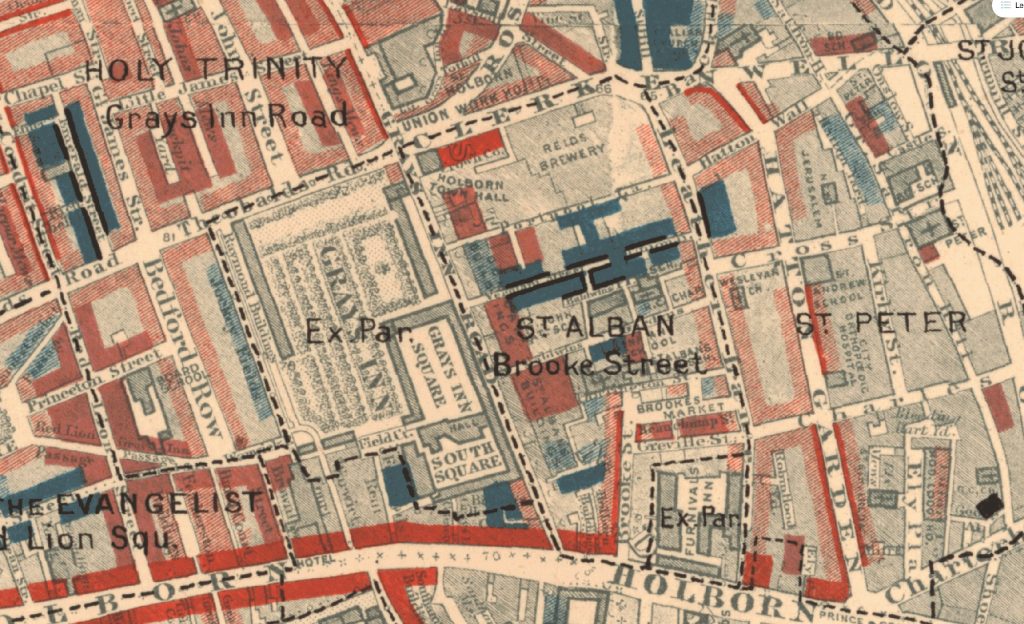

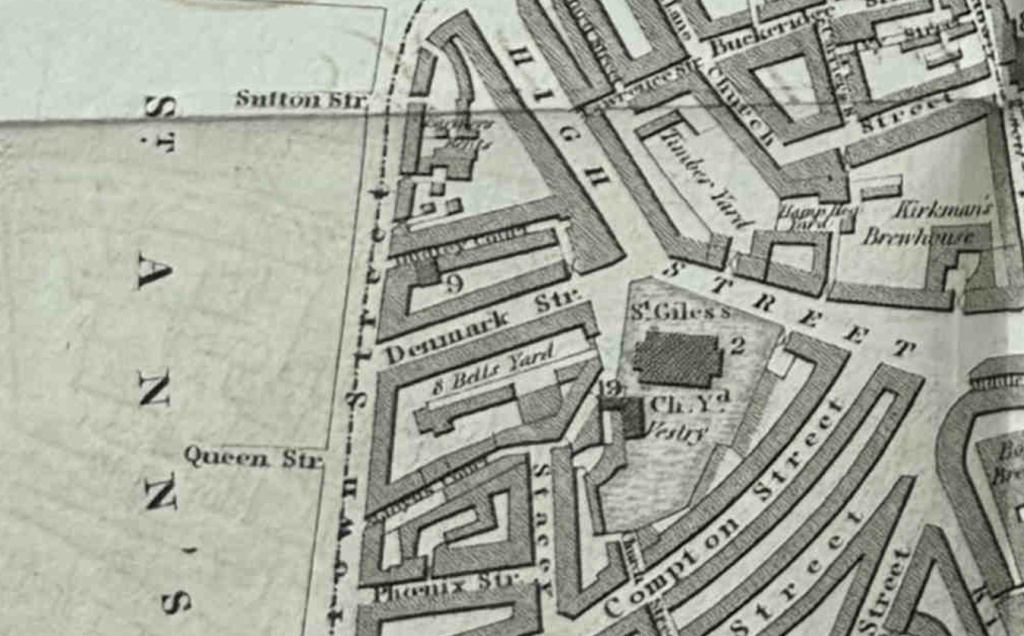

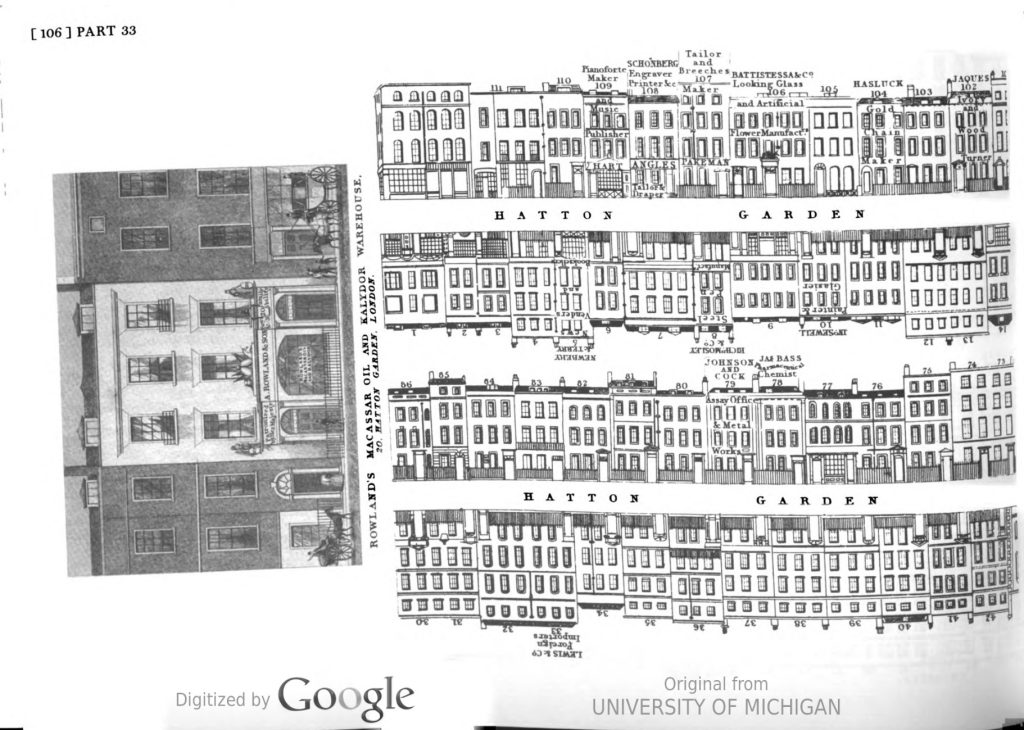

An example of the way that streets are illustrated is the following view of part of Hatton Garden:

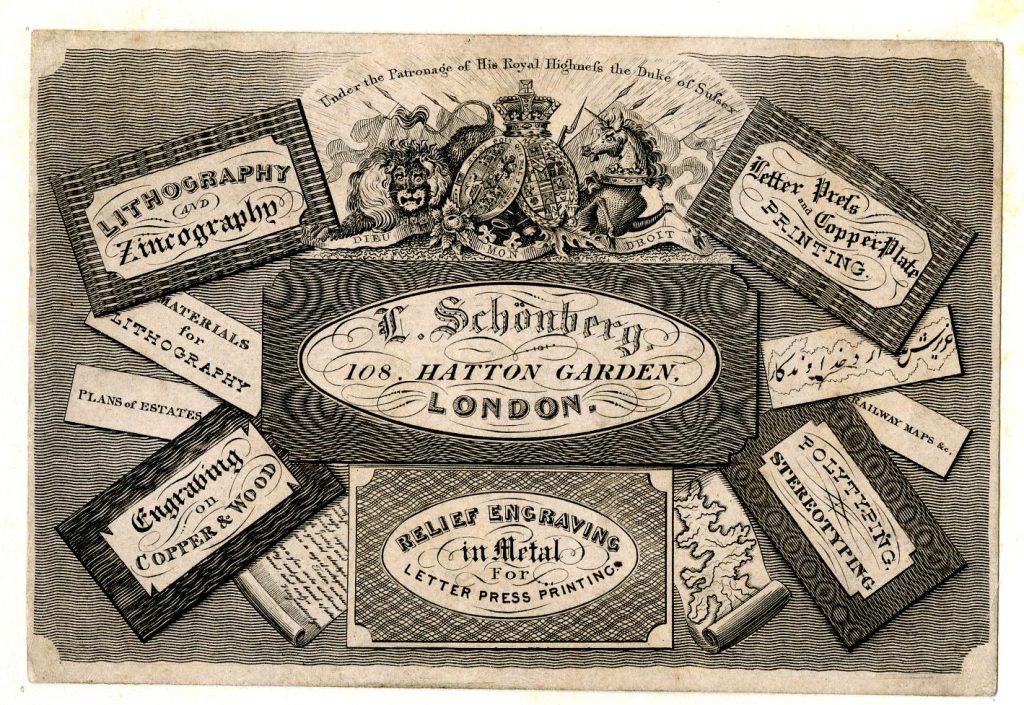

As well as an illustration of the building, where a business occupies a building, the name and trade is also provided, so at number 109 Hatton Garden there is a Pianoforte Maker and Music Publisher who presumably goes by the name of Hart.

Next door at 108 there is Schonberg, Engraver and Printer, along with a Taylor and Draper in the same building, and at 106 there is Battistessa & Co, Looking Glass and Artificial Flower Maker.

What is fascinating is being able to find more about these business, and in the British Museum collection is a trade card for the above mentioned L. Schonberg of 108 Hatton Garden:

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

Tallis’s London Street View is a fascinating way of walking the streets of London in the late 1830s and early 1840s, and a reminder that John Tallis came up with this format of recording a city long before Google Street View.

Google Street View is a brilliant equivalent resource of today. Imagine being interested in London’s history in a couple of centuries time, and being able to walk through a photographic view of the City’s streets, however continuing the theme of the future is always very different to that we expect, and that services such as Street View are digital, will they survive that length of time given the magnitude of change that can occur over such a period of time.