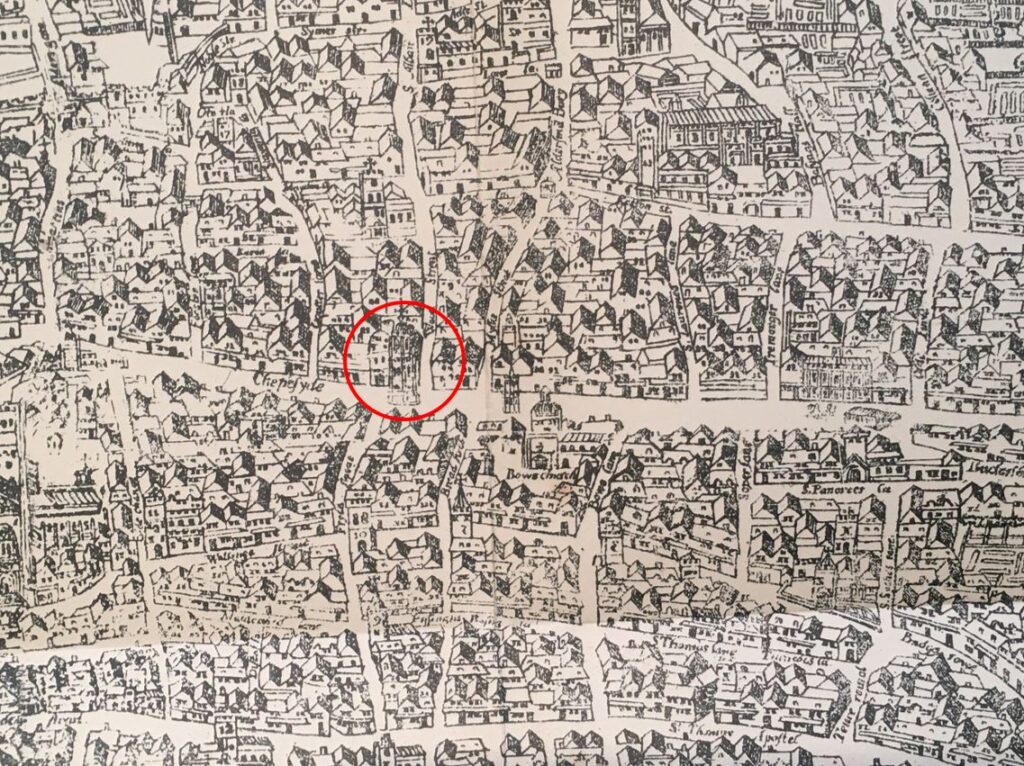

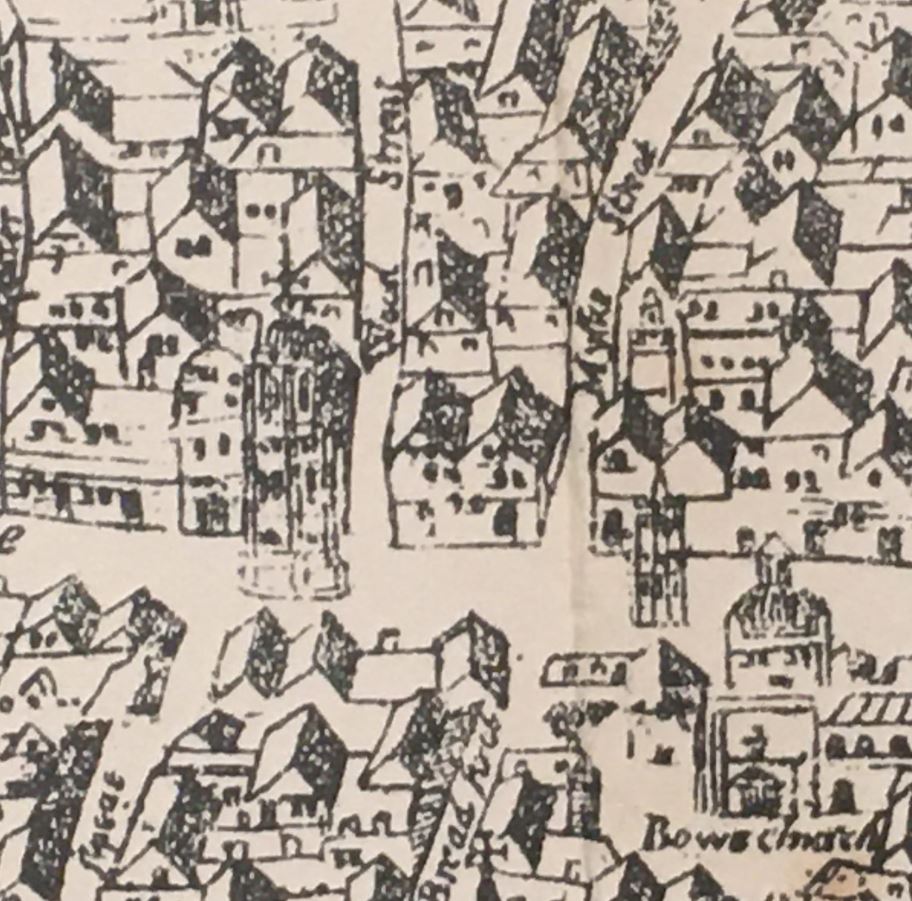

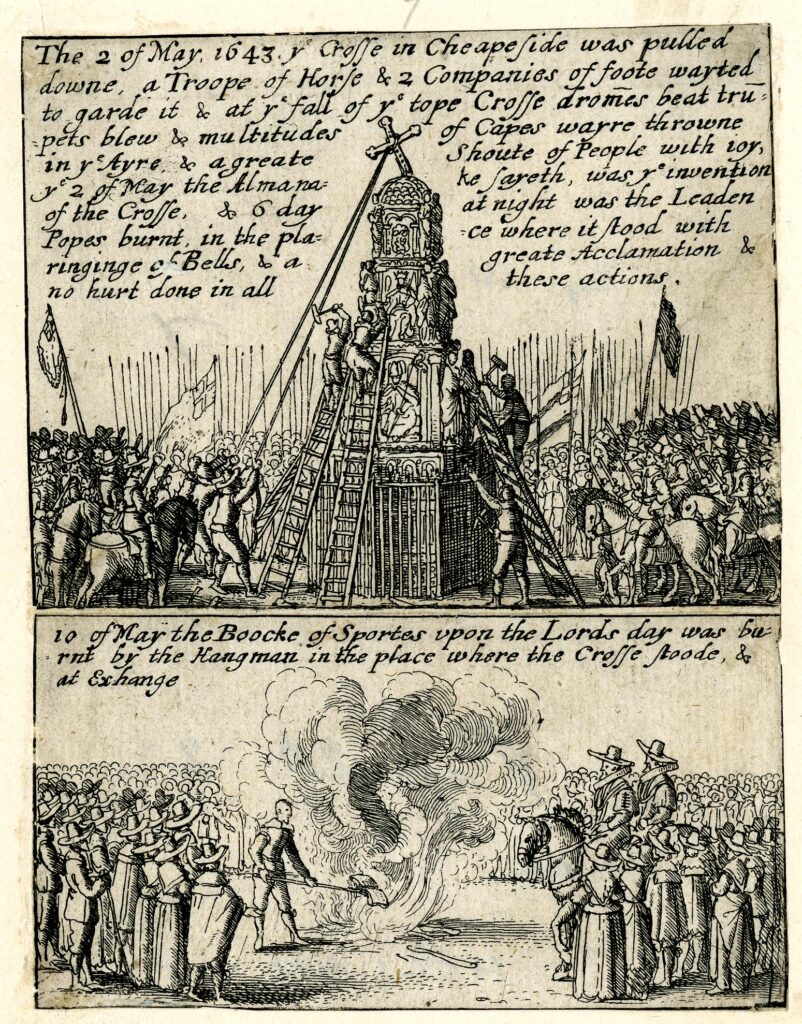

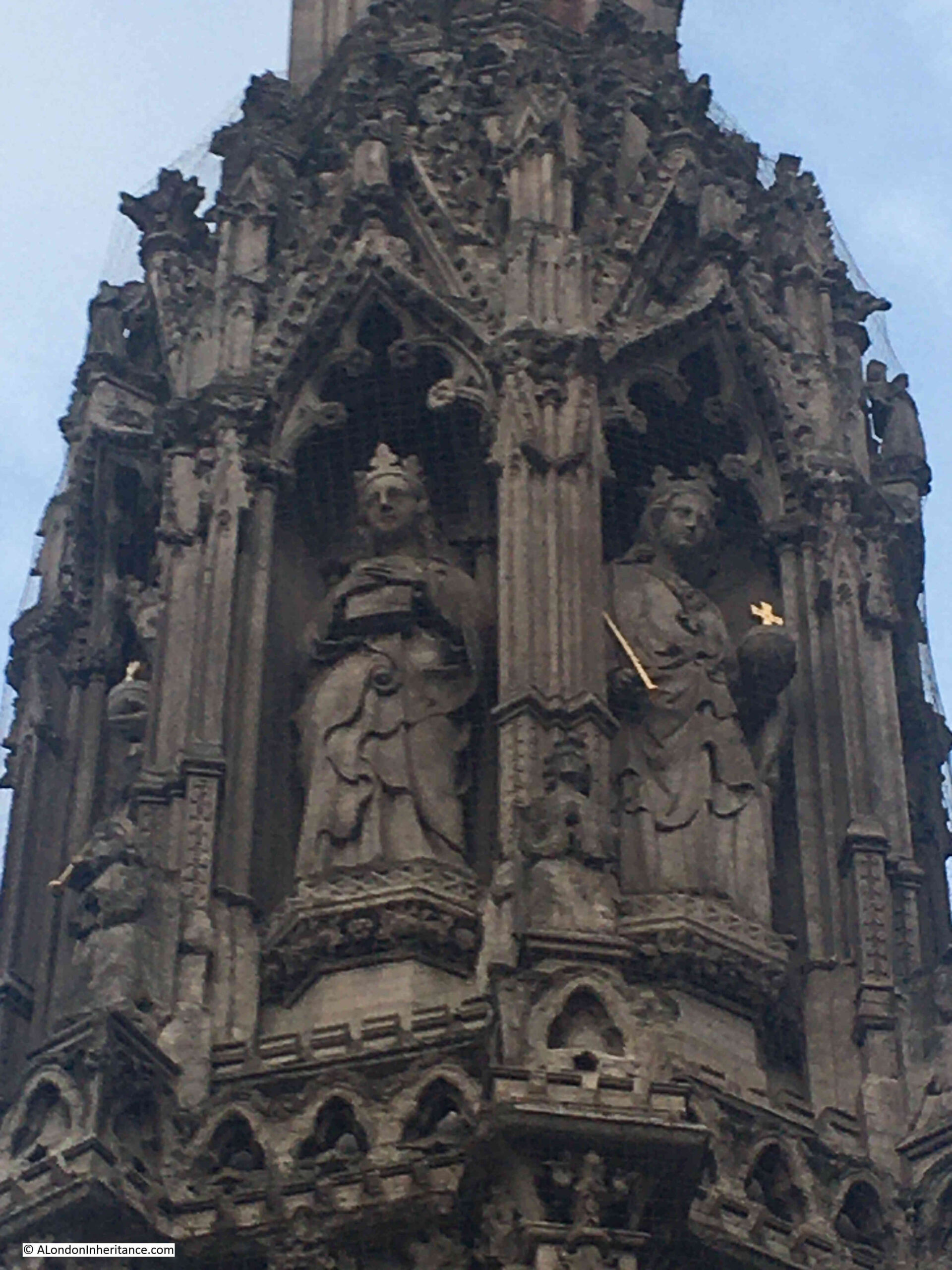

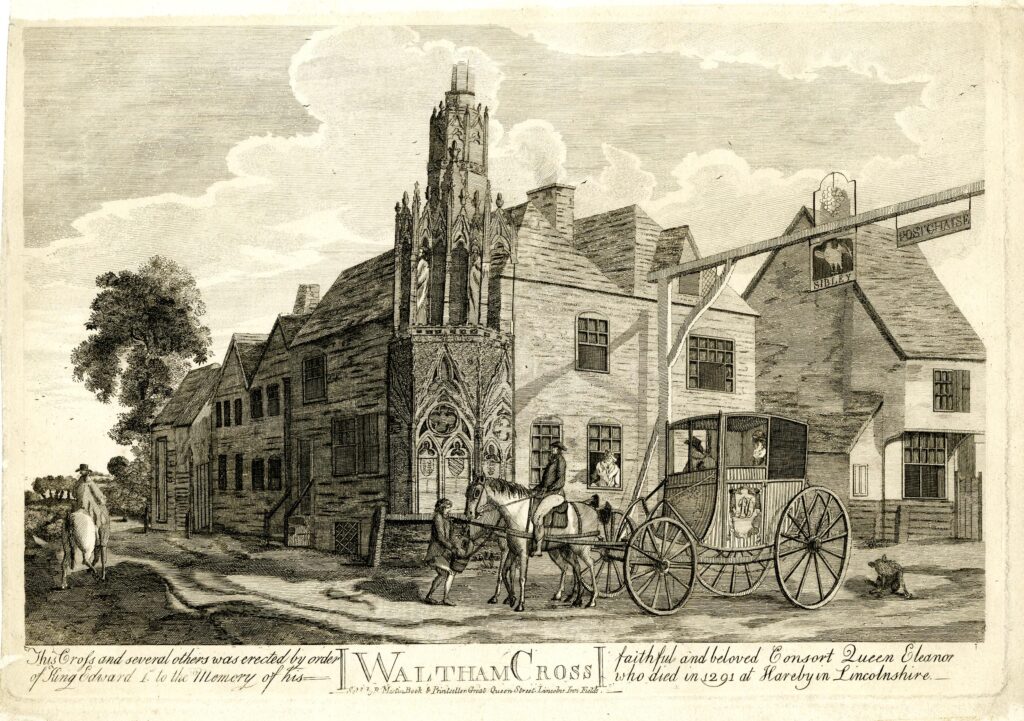

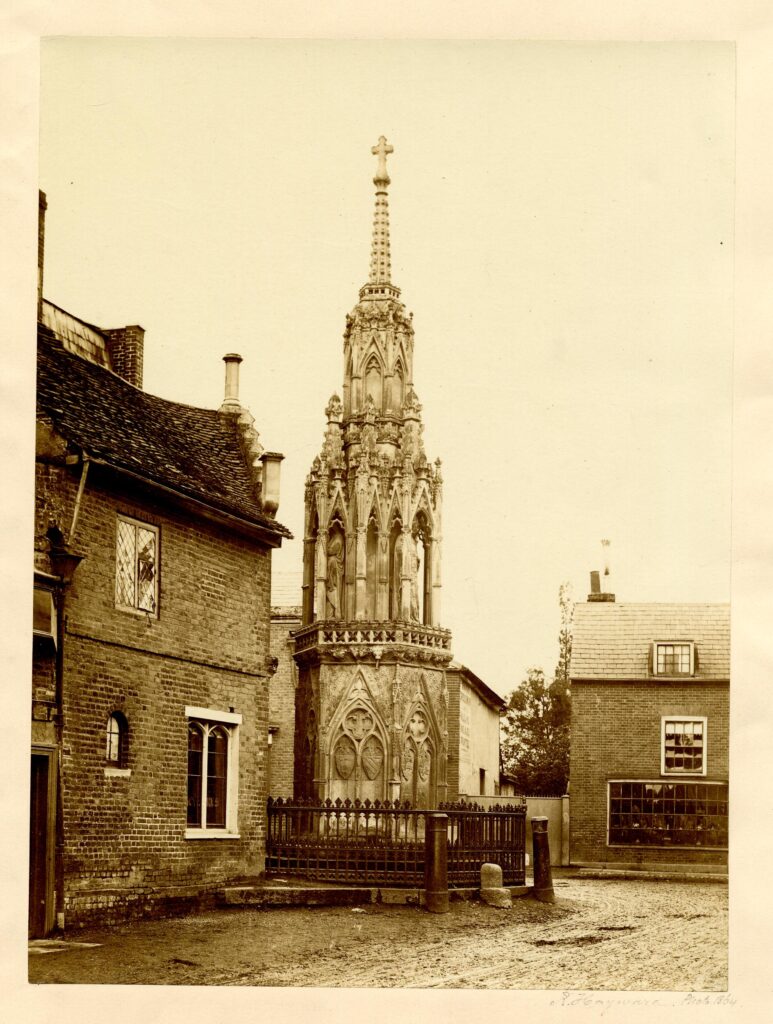

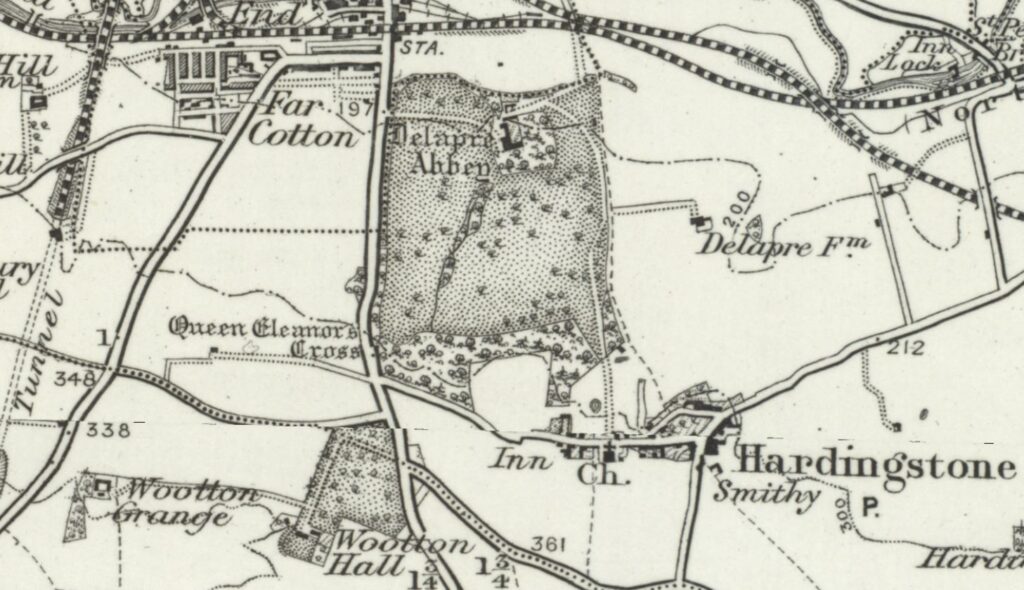

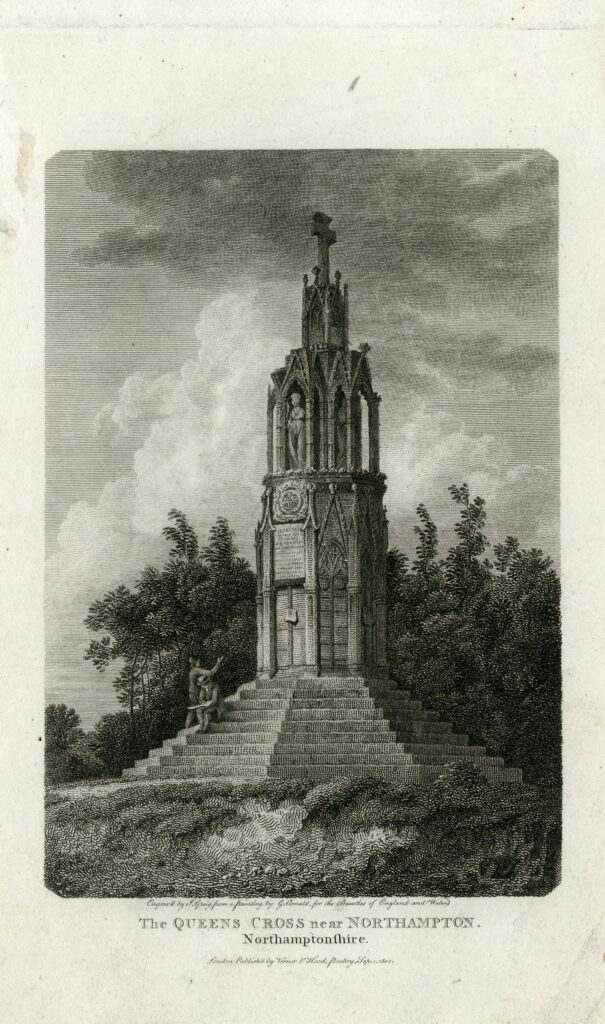

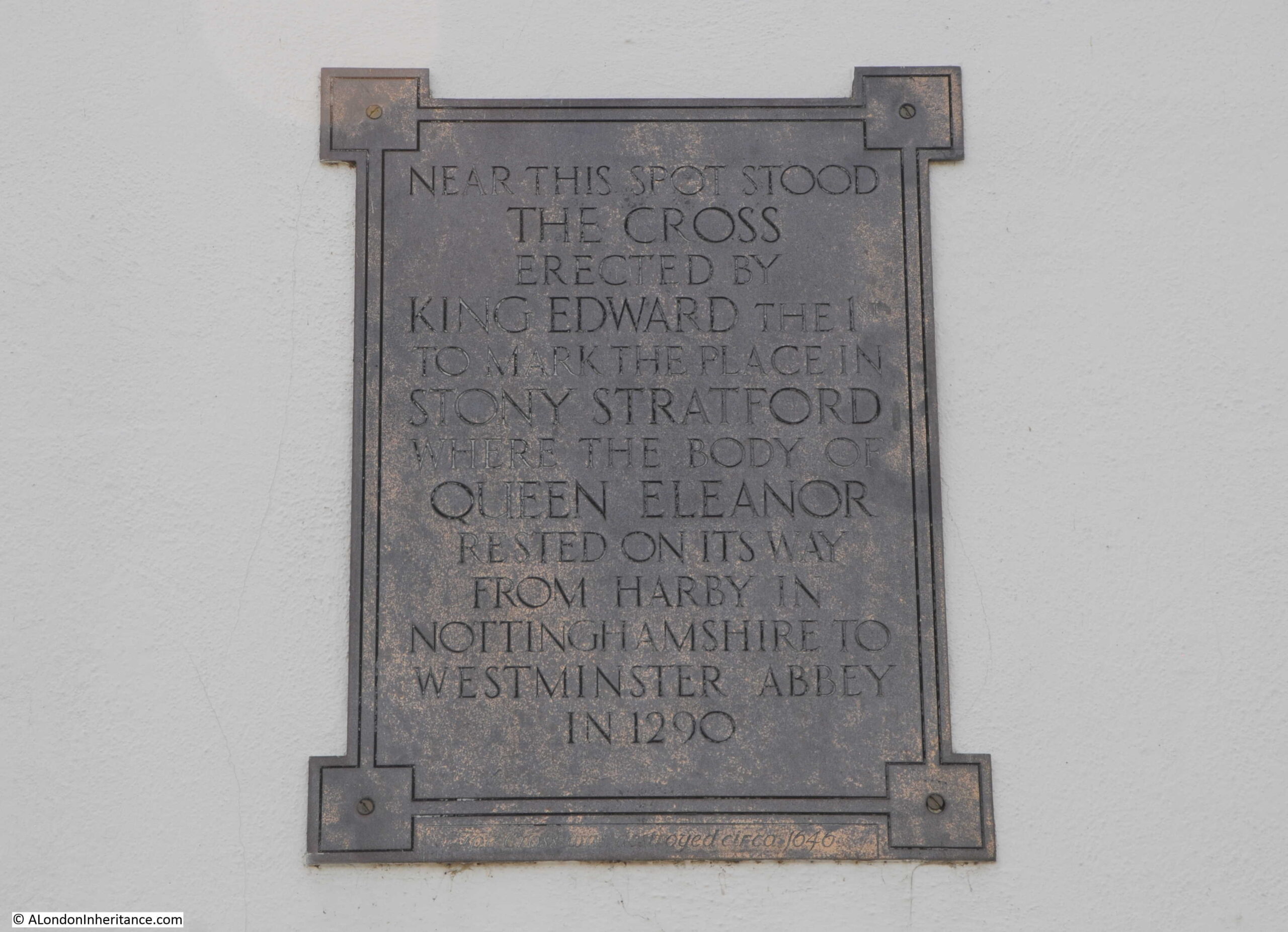

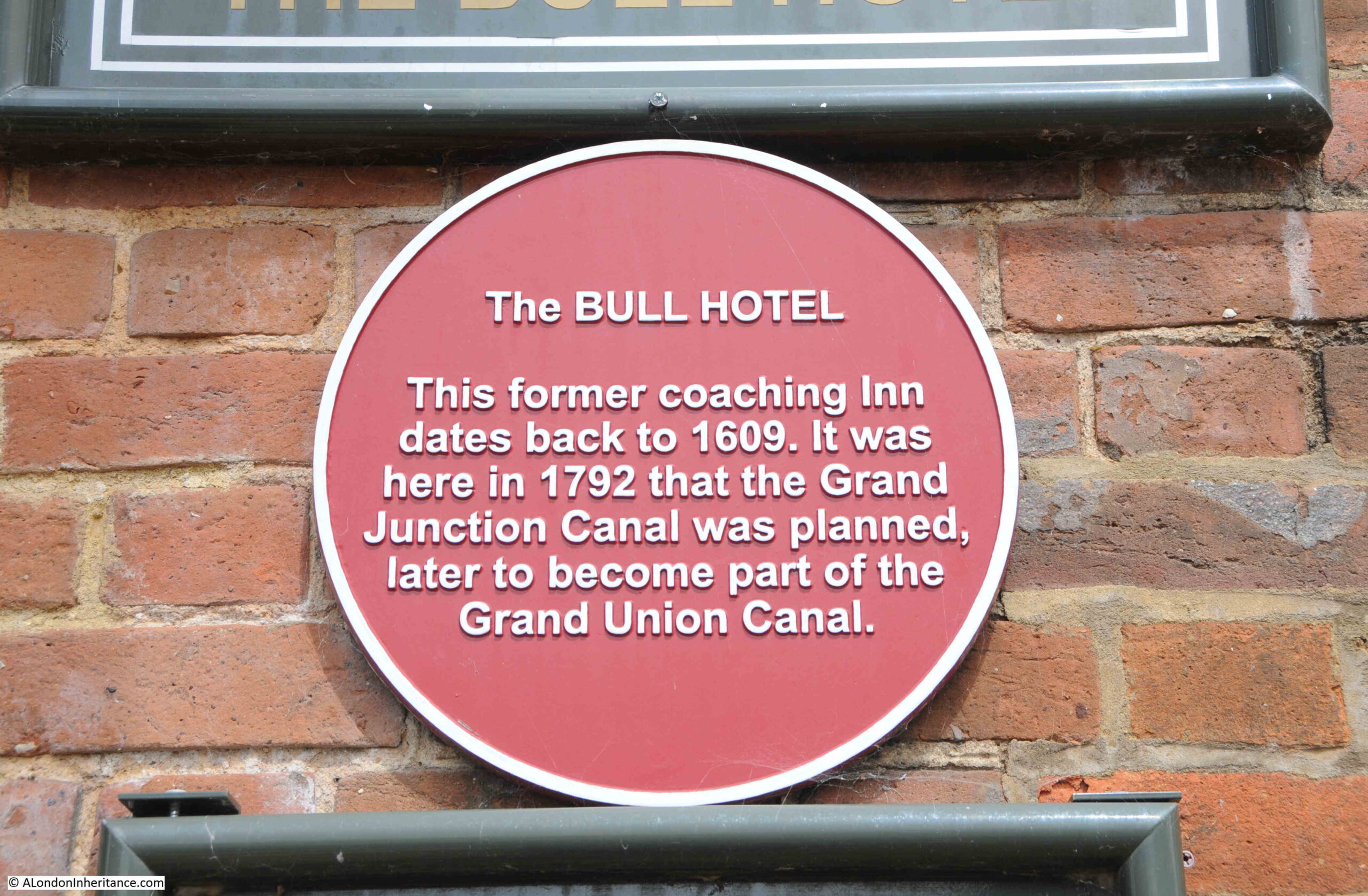

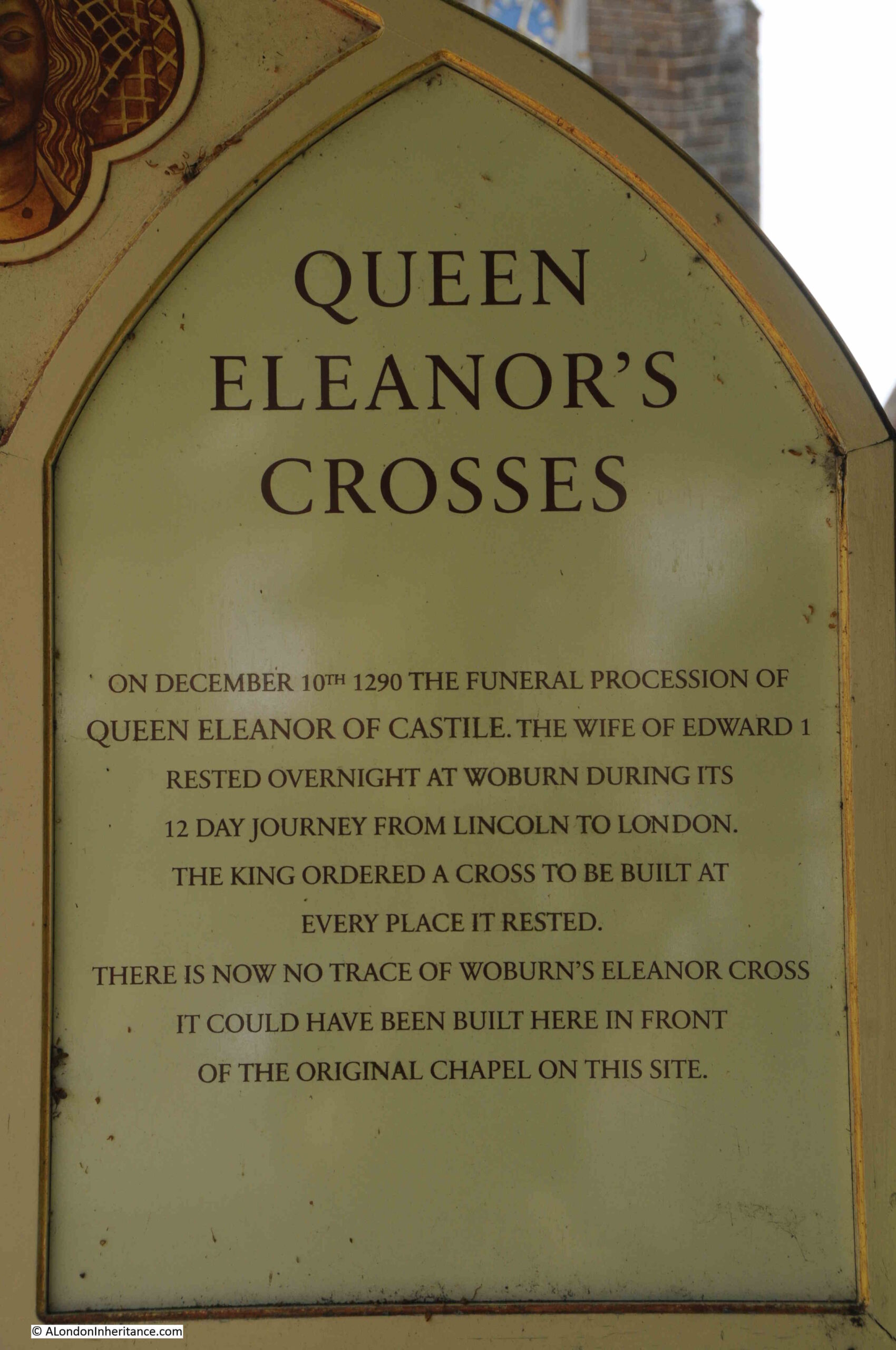

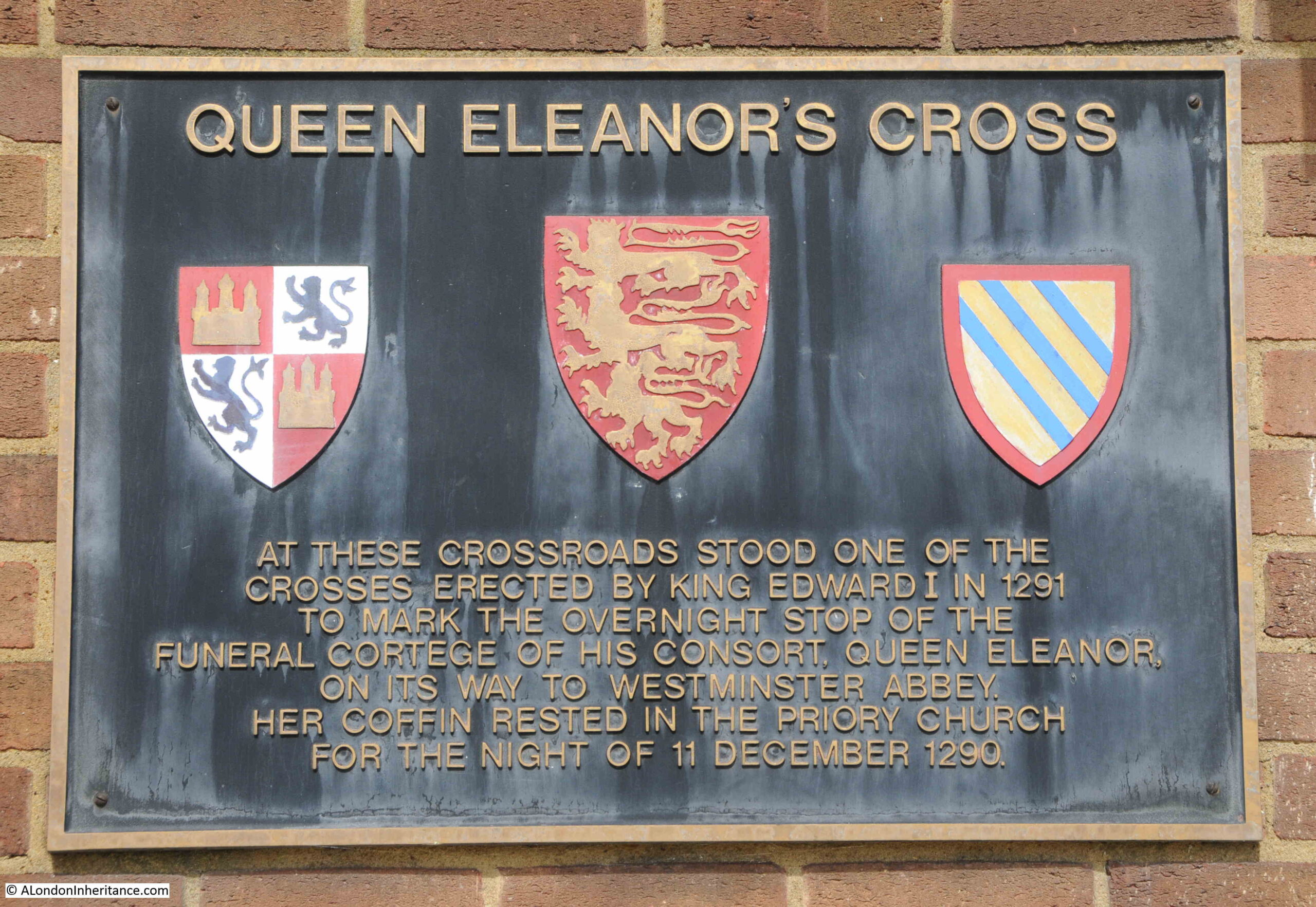

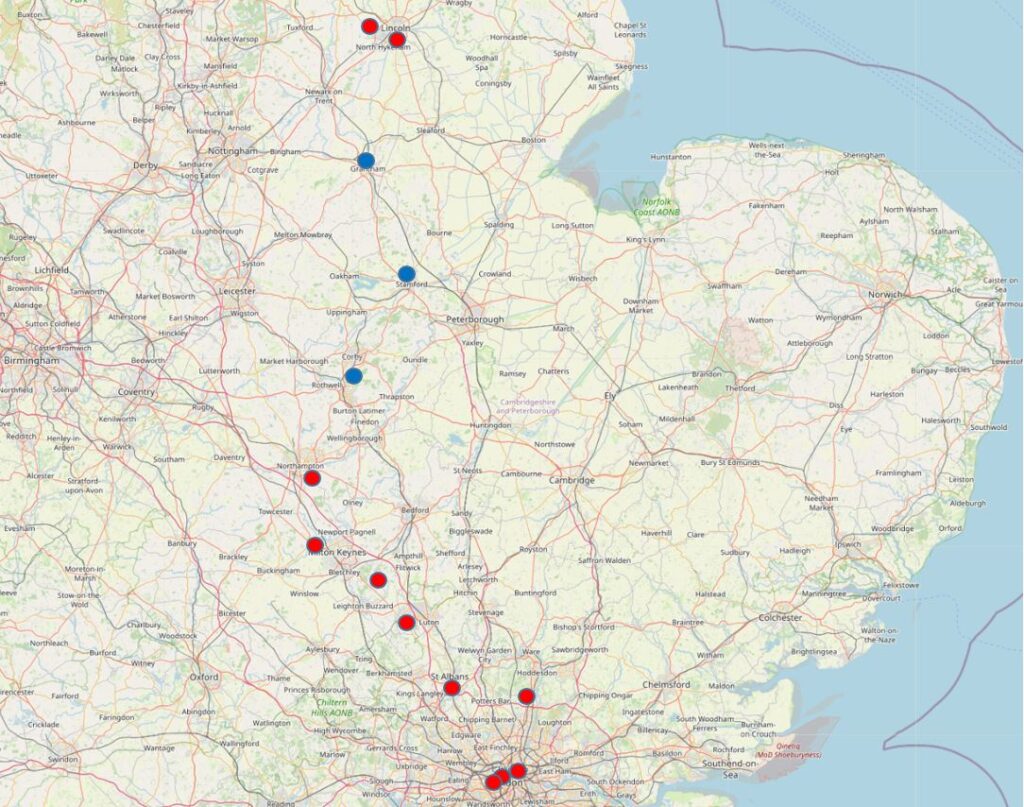

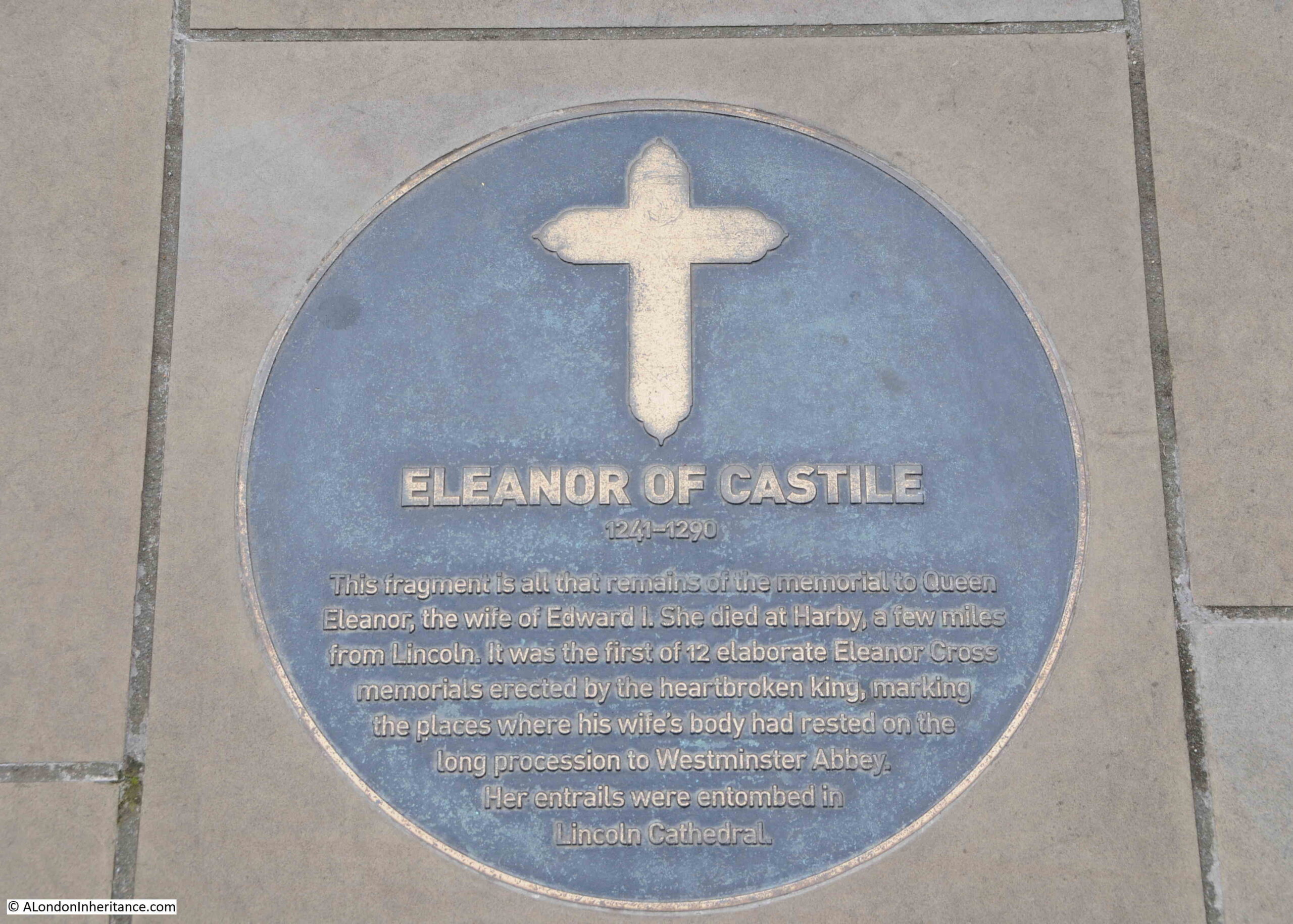

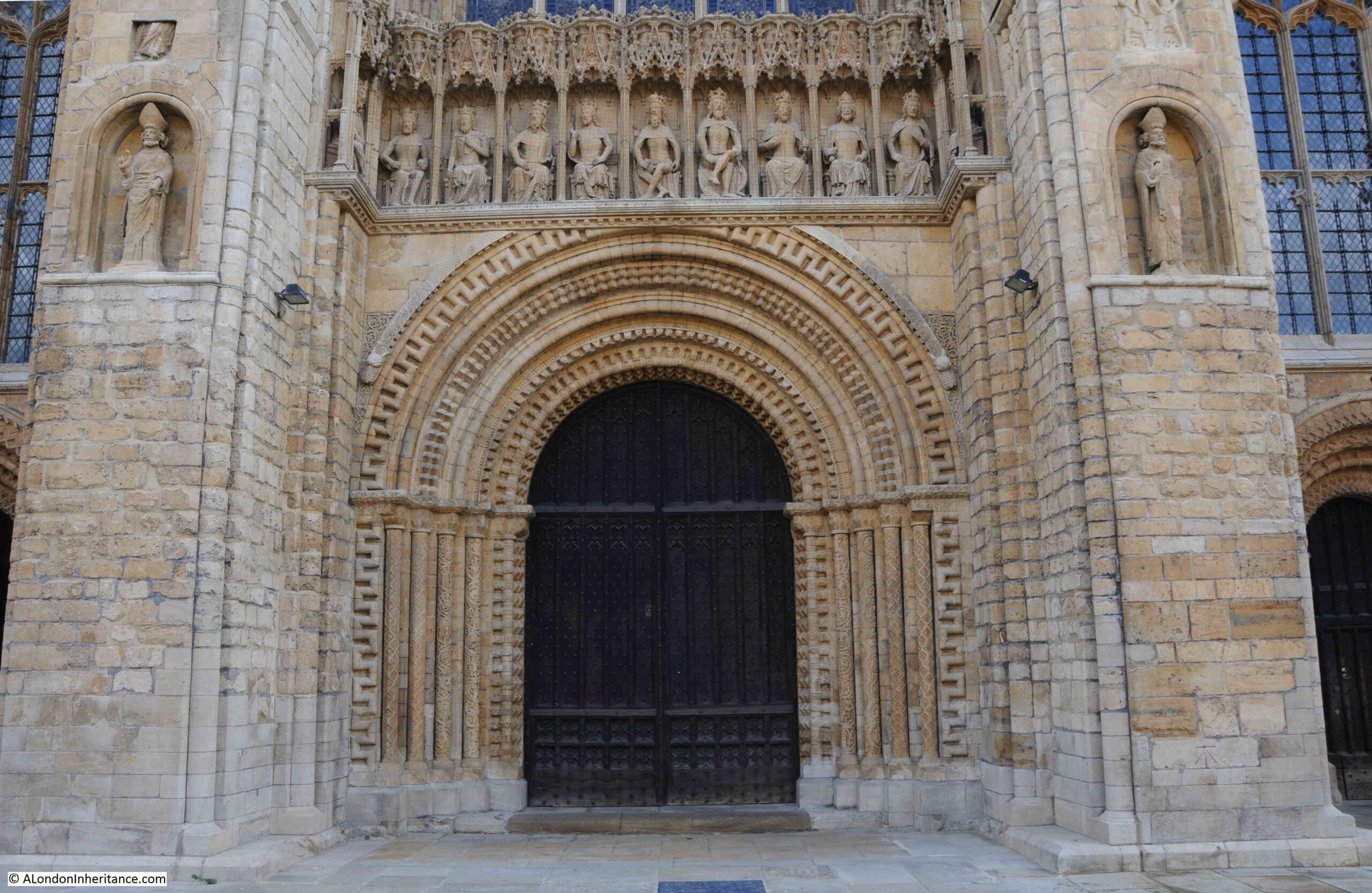

A couple of weeks ago I wrote about the route that the body of Eleanor of Castile took to reach London, and the crosses that were built to mark the route. For today’s post I am tracing another of the historic routes that link London with the rest of the country.

Back in the 18th century, the speed of communication was mainly dependent on how long it took a horse and rider to travel between the source and destination of a message. Routine mail would be carried by stage coach and urgent messages would travel via a horse and rider who could travel much faster, but would still be limited by the speed of the horse, conditions of the roads, weather need to change and rest horses etc.

In 1770, the average time taken between London and Portsmouth was around 17 hours, but with improvements to road surfaces and coach building, by around 1820 this had improved to 9 hours for the fastest coaches.

The very best horse and rider could cover the route in just under 5 hours.

It seems remarkable when today we can make an instantaneous mobile phone call from almost anywhere in the country to the other side of the world, that just two hundred years ago it would take a day to get a message and answer between London and Portsmouth.

Portsmouth was important as it was the site of a major naval dockyard, and with the frequent wars of the late 18th and early 19th centuries there was need to devise a system which could rapidly send messages between the Admiralty in London, and the naval dockyards.

The Napoleonic Wars of the later 18th century resulted in the Admiralty building a telegraph system that copied a system already set up by the French. This used a method where signaling stations were based at high points along the route between London and Portsmouth. At each station, there was a wooden shed with a shutter frame built above. The frame held six shutters in two columns, and each shutter could be opened or closed to send a message to the next station along the route.

It was claimed that a message could be sent between London and Portsmouth in just under 8 minutes.

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars the system was dismantled, with Napoleon being held on the Isle of Elba.

Not long after, Napoleon escaped and returned to France, and the state of war between England and France resumed. The Admiralty needed another, and more permanent line of communication between London and Portsmouth, rather than the temporary wooden sheds set up for the shutter system.

The Admiralty created a new signaling line comprised of stations using a semaphore system, where the positions of two moveable arms would signify a message to be sent along the chain.

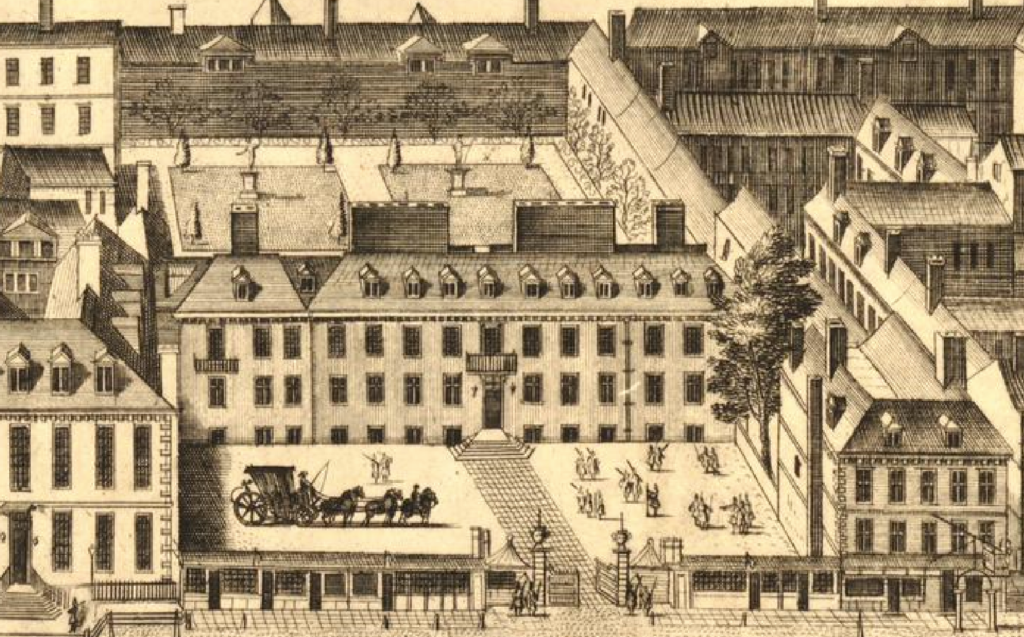

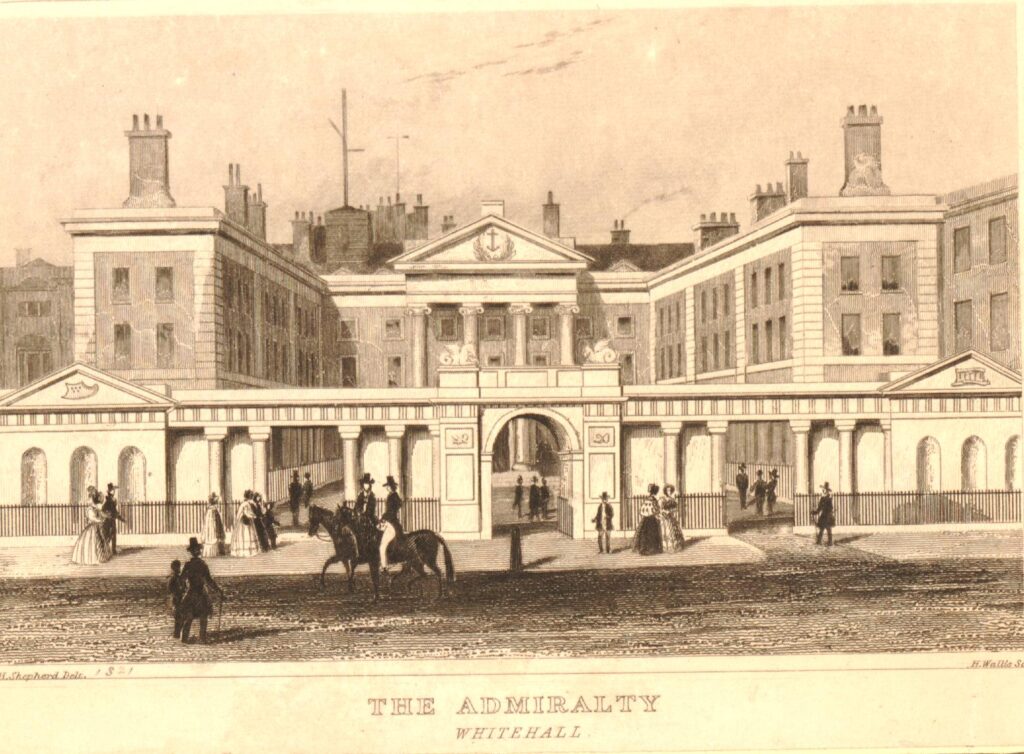

The following print shows the Admiralty building in Whitehall. On the roof at the rear of the building, a tall post can be seen with two arms. This was the London end of the chain of stations between London and Portsmouth (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

Signaling stations were needed at high points on the route between London and Portsmouth. Each station was equipped with a post and signaling arms, and had an observer with a telescope to keep an eye on the adjacent stations in the chain for any message that needed to be sent onwards.

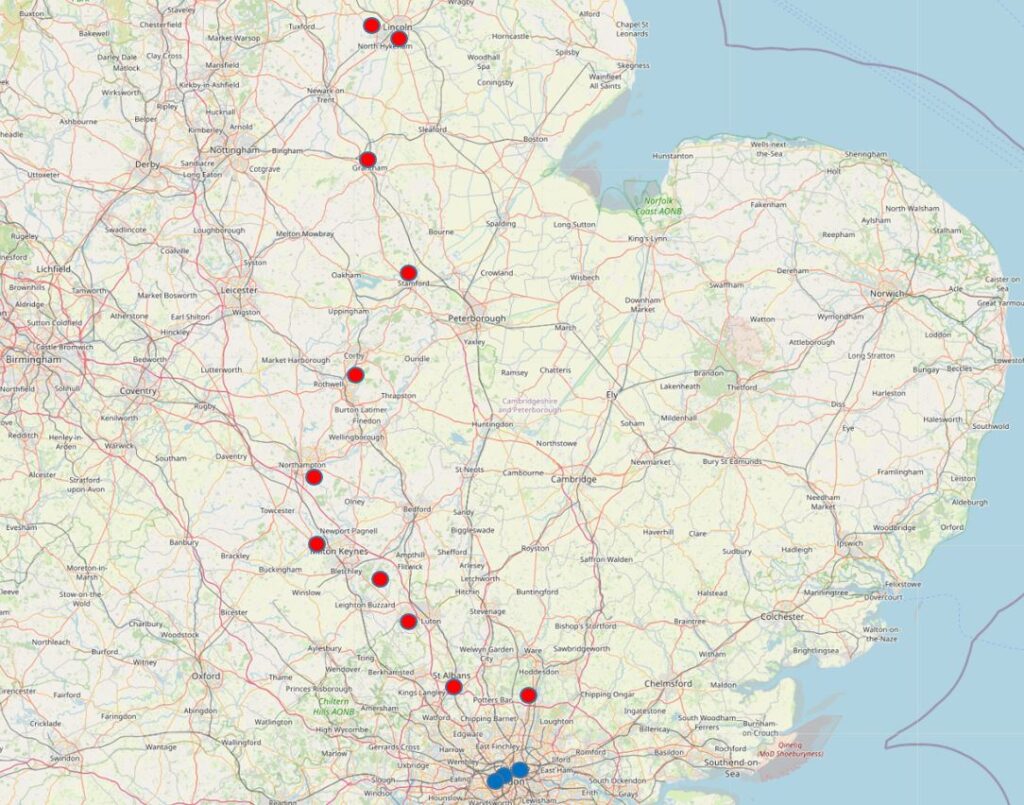

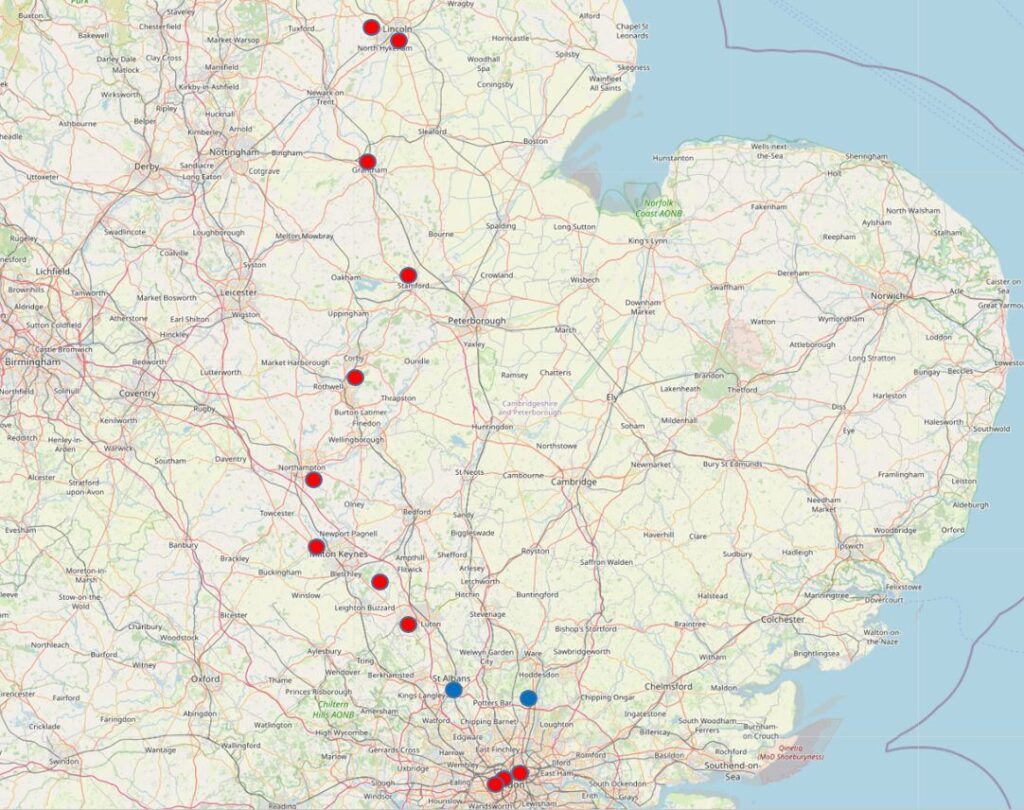

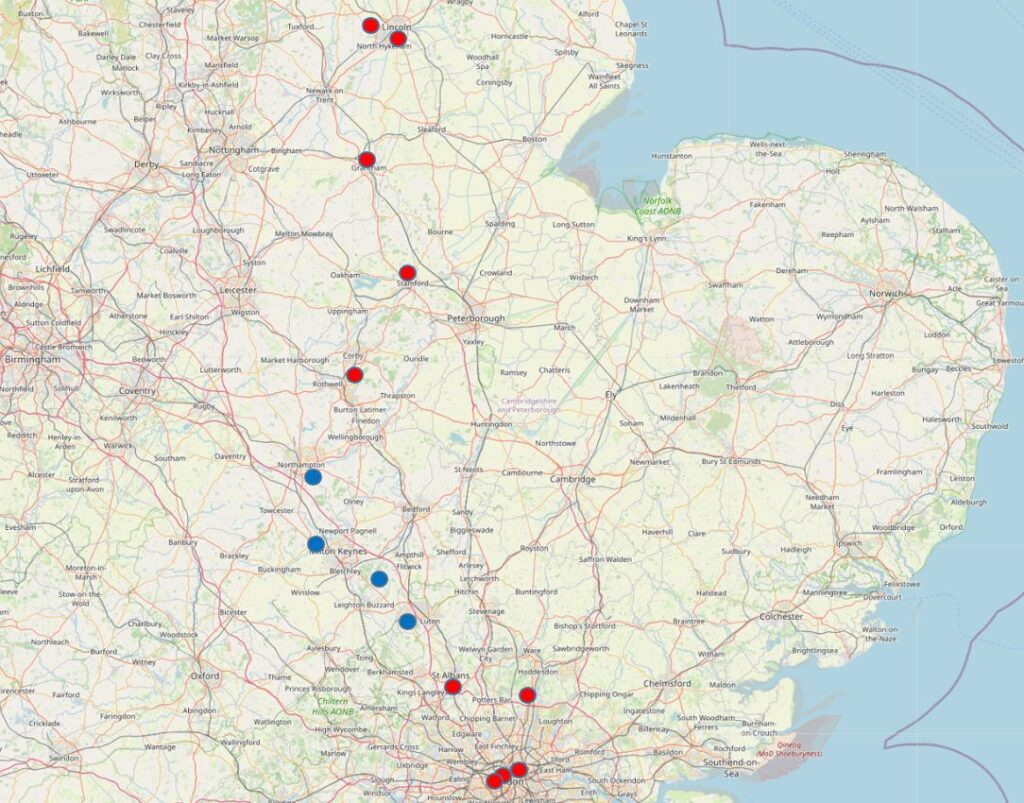

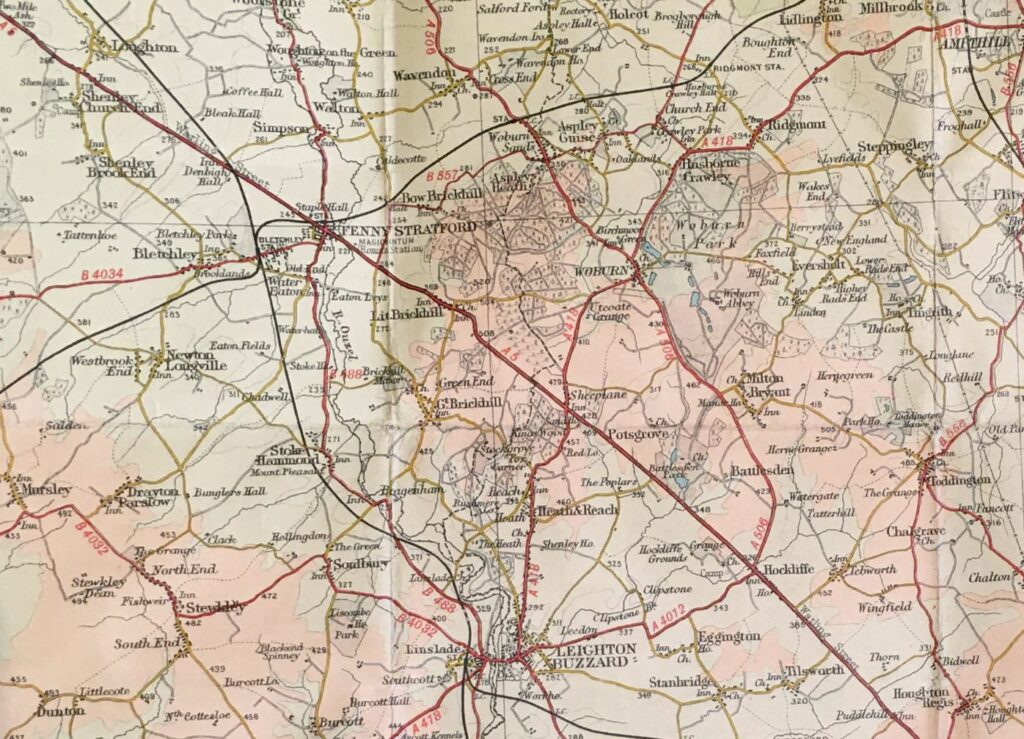

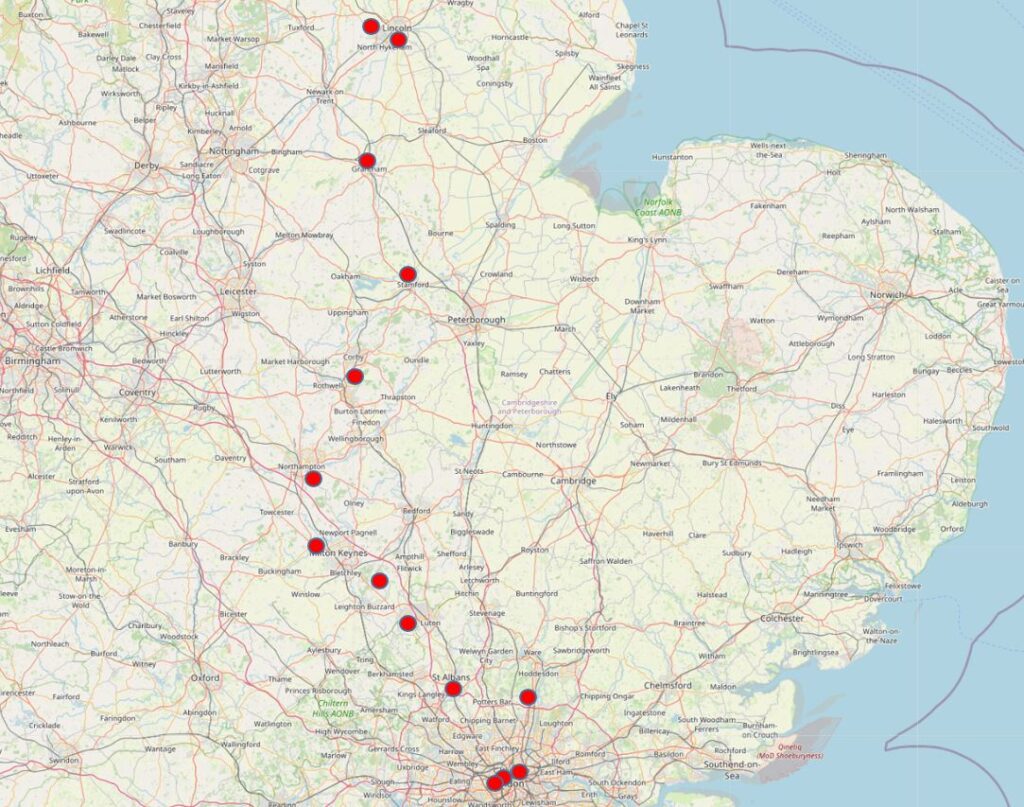

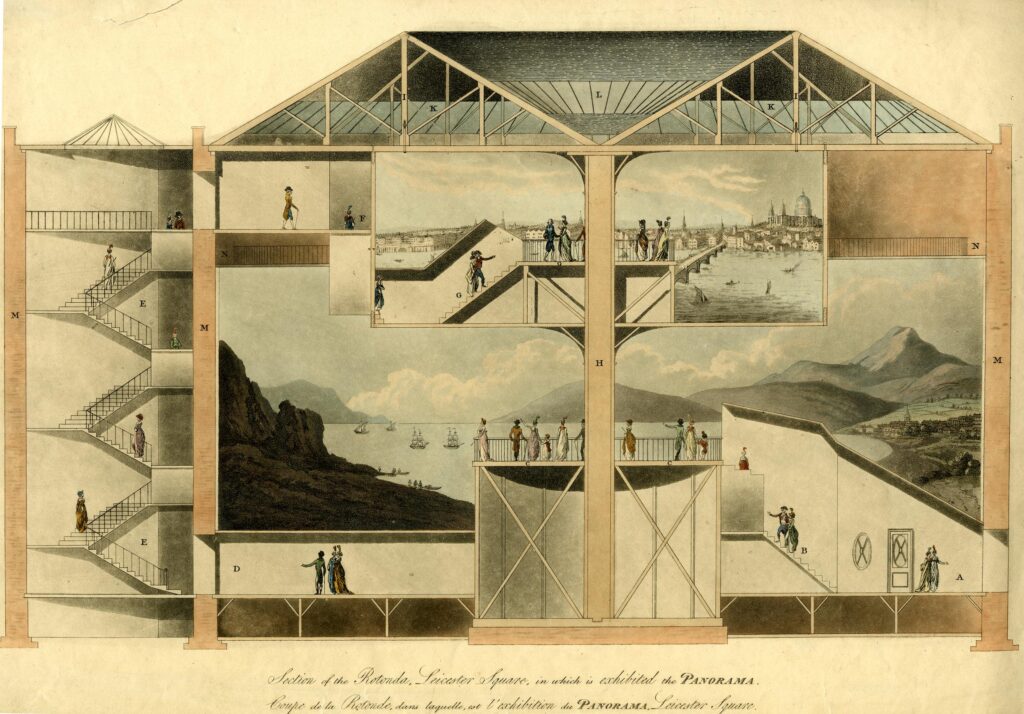

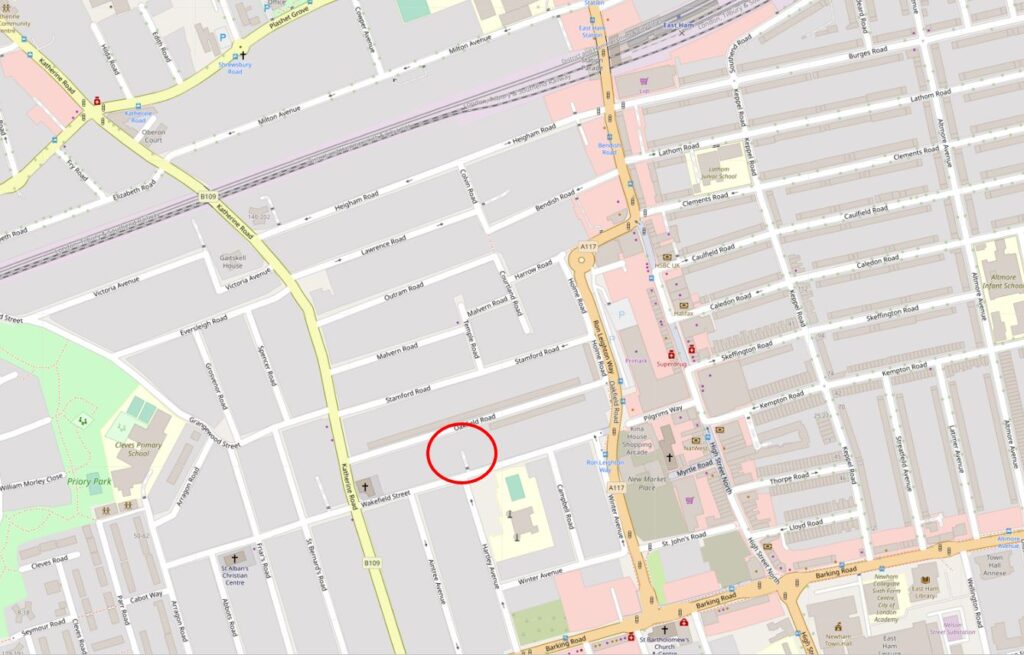

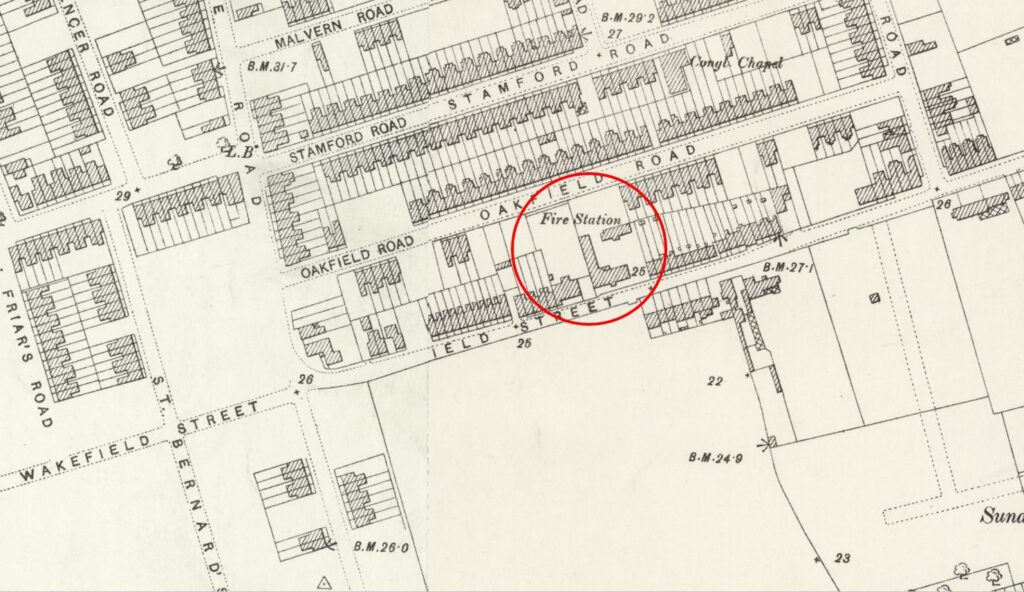

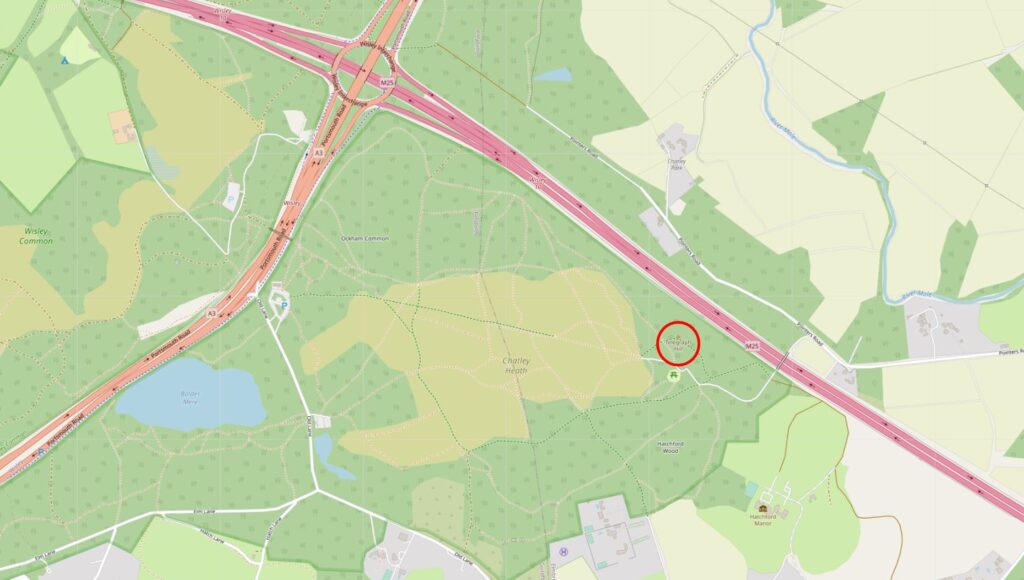

The following map shows the chain of stations from the Admiralty at top right down to the dockyard in Portsmouth at lower left (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

The system was opened two hundred years ago, in 1822, and an article in Bell’s Weekly Messenger in September 1822 listed the stations as;

The Admiralty, Chelsea, Putney Heath, Kingston Hill, Cooper’s Hill, Chatley Hill, Pewley Hill, Bannicle Hill, Haste Hill, Holner Hill, Beacon Hill, Compton Down, Portsdown, Lumps Fort (Southsea) and Portsmouth naval dockyard.

In 1822 it was claimed that a message could be conveyed between the Admiralty in London to Portsmouth in one minute and a few seconds. This seems remarkable and must have been in ideal conditions, perfect visibility, and the staff at the stations were ready for the receipt and forwarding of a very short message. Reports of normal transmission times state that around 15 minutes was the time taken to send a message from one end of the chain to the other – still a remarkably short time.

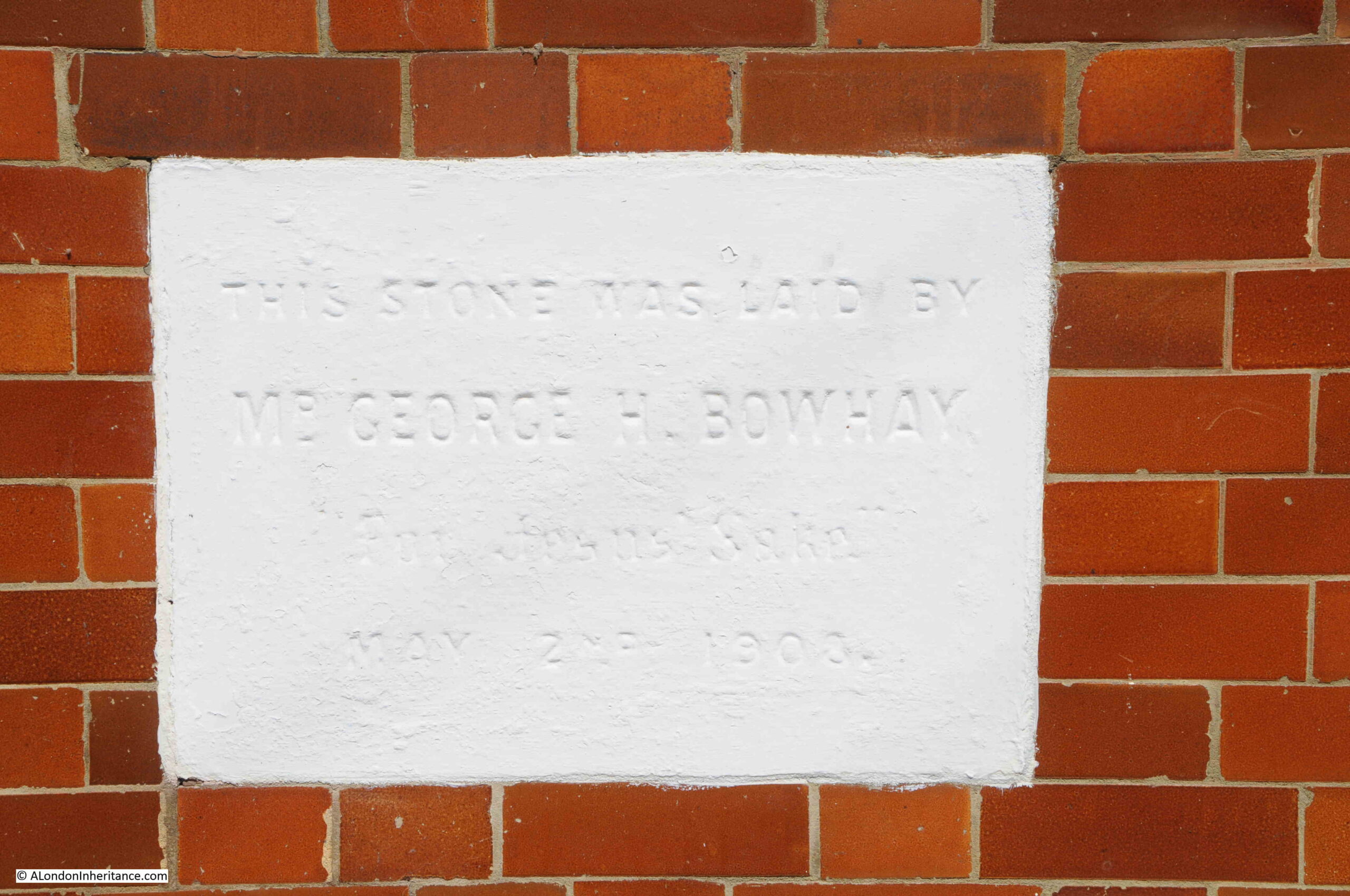

There is one remaining, complete, semaphore tower on the line between London and Portsmouth, at Chatley Heath in Surrey. Indeed it is the only remaining complete semaphore tower in the country. It has recently been restored by the Landmark Trust who held an open day in the summer. so I went along to see this remaining example of two hundred year old communications technology that linked London with the south coast.

In the above map of the whole chain of stations, I have marked Chatley Heath with a red circle around the red dot.

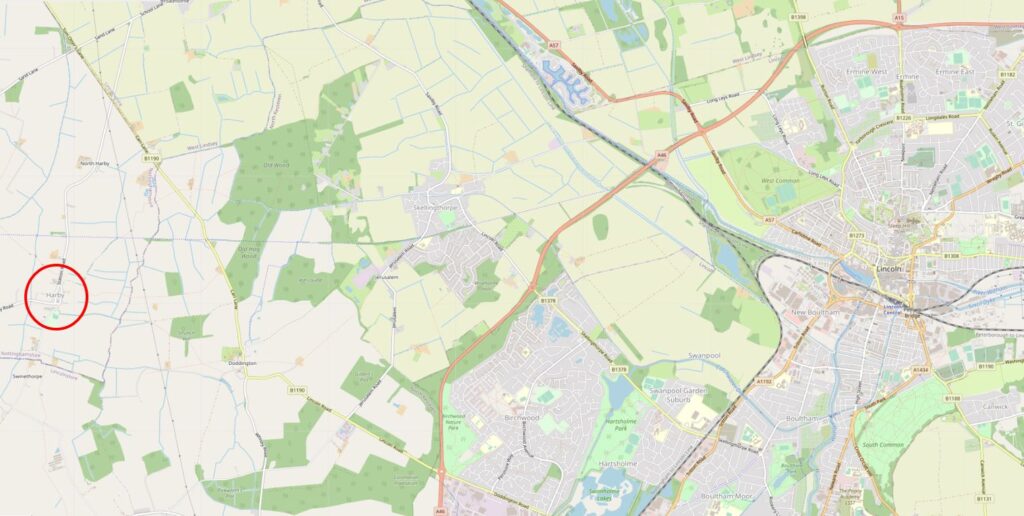

The following map shows the exact location of the Chatley Heath semaphore tower, a very short distance from the M25 and slightly to the east of the A3 (© OpenStreetMap contributors):

Chatley Heath is part of a wider area of 800 acres of commons and rare heathland that is managed by the Surrey Wildlife Trust. There are paths across the heath, some of which are signposted to show the route to the semaphore tower:

The open day was on one of the hot days of summer, where the land was so dry following weeks with no rain, a big contrast as I type this, as it is cold, cloudy and there has been much rain over the last few weeks.

Following the path to the semaphore tower:

The following photo shows the first glimpse of the semaphore arms at the very top of the tower, just showing above the tree line in the distance in the centre of the photo:

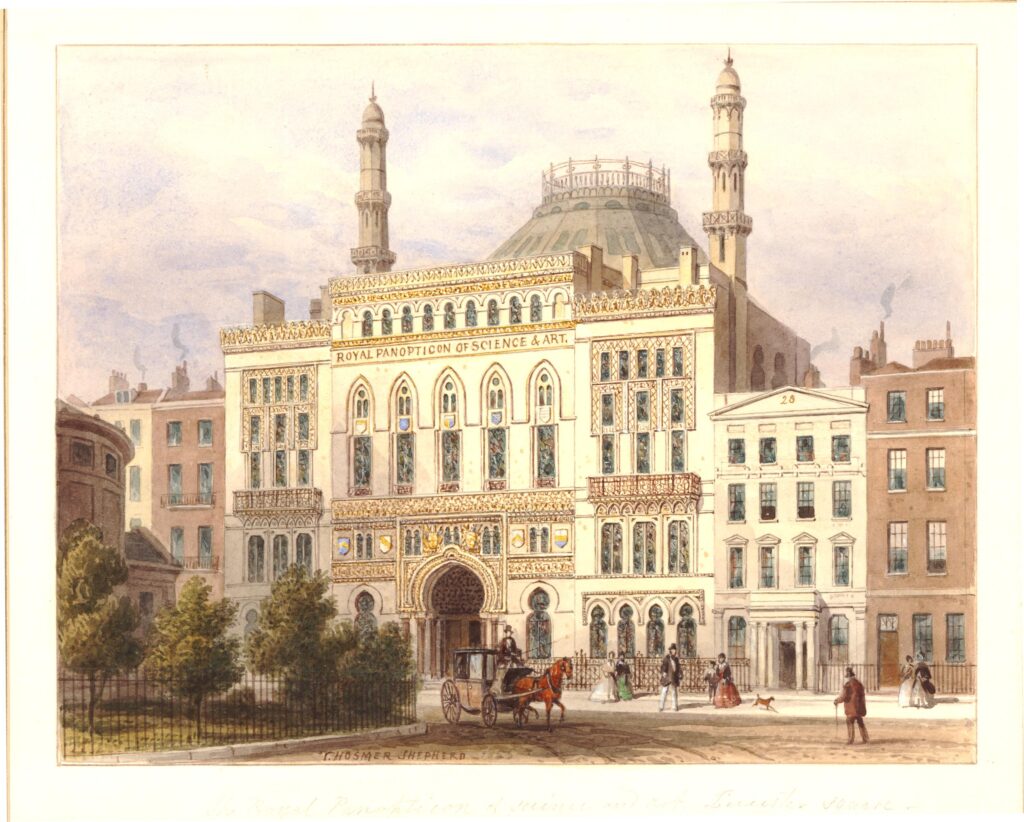

Finally reaching the Chatley Heath semaphore tower. The one remaining, fully restored tower, and the tallest on the line between the Admiralty in London, and Portsmouth.

Each semaphore station was manned by a retired navy lieutenant and an observer, usually a retired sailor of the lieutenants choosing. The lieutenant would be in charge of the station, and the observer was responsible for using a telescope to keep an eye on adjacent stations to check for messages to be forwarded.

The very first officer at the Chatley Heath tower when it opened in 1822 was Lieutenant Edward Harris.

The Chatley Heath tower included accommodation with a small house built onto the base of the tower. The blocked up windows in the tower were probably done to save the cost of building and installing windows. The navy was exempt from window tax, so this would not have been the reason. The shape of the tower was also more cost effective than the complexity of building a circular tower.

The semaphore system used a code devised by Rear Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham.

It was Popham who created the code using flags, allowing messages to be sent between ships at sea, and it was his code that sent the message from Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar that “England expects that every man will do his duty”. He was involved in a number of naval actions, and assaults on enemy land forces across the world, but must have spent some time at home as his wife had at least ten children.

Popham’s semaphore code used two arms on a wooden post. Each arm could assume any position on either side of the post, so could be either horizontal, vertical, or at an angle of 45 degrees, pointing up or down the post.

This arrangement created enough positions using the two arms that every letter of the alphabet, along with the numbers 0 to 9, could all be transmitted.

The two arms and vertical post:

From 1963 until 1988 the tower was left empty. It was vandalised and had suffered a major fire. It was restored in 1988 by Surrey County Council and then passed to the Surrey Wildlife Trust.

The age and very exposed position of the tower resulted in further, gradual deterioration, with water being a problem, getting into the tower around the base of the post, and around the windows.

The Landmark Trust then took on the tower and commenced a full restoration project in 2020. The Landmark Trust has restored and runs some remarkable buildings across the country, and following a restoration, they rent out the buildings for short stays, and this is now the future of the Chatley Heath semaphore tower.

The restoration including fitting out the tower so that it would include accommodation, so today, walking up the tower to the roof includes a walk through a number of rooms, which include a lounge:

Kitchen:

And bedroom:

There is a second bedroom (the tower now sleeps 4) and a bathroom.

In the kitchen, the restored mechanism used to control the position of the arms can be seen:

Once on the roof, it is easy to see why this was the chosen location for the station. It is one of the highest points in the local area at 59 meters above sea level, with the land dropping by 10 to 20 meters in the area surrounding the station.

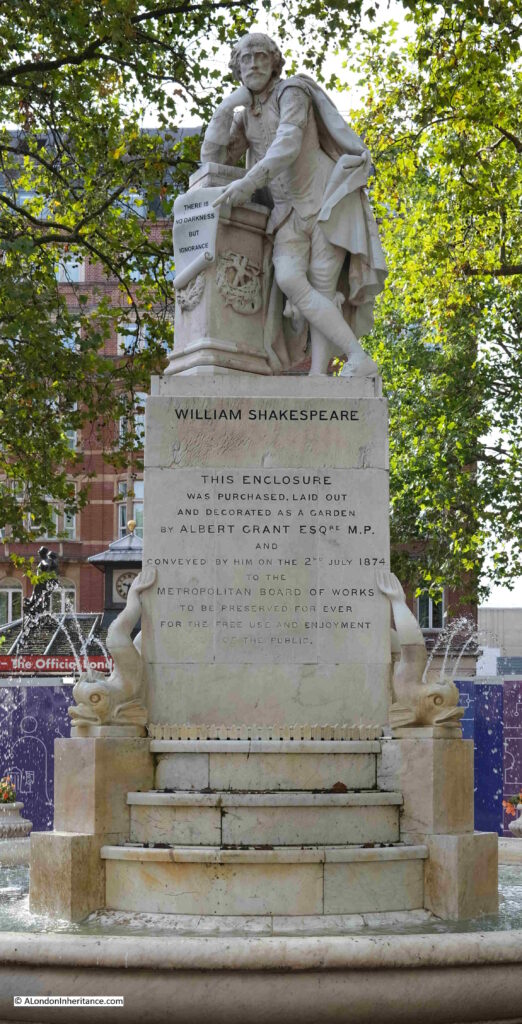

This is the view looking towards London:

Zooming in from the roof of the tower, we can see the towers of London in the far distance, the Shard to the right is just over 31km from the Chatley Heath semaphore tower.

The semaphore post and arms seen from the top of the tower:

Operating the semaphore was not without its dangers. The Hampshire and Southampton County Newspaper reported on the 15th of August 1825 that: “During the thunder storm on Wednesday last, E. Oke, the signal man belonging to the semaphore in Portsmouth, was knocked down and remained insensible for several minutes. The semaphore was at work at the time, and the man had his hand on the wheel, which turns the arms to communicate intelligence to the next station. The whole apparatus is composed of metal, which, of course, attracted the lightning. The Lieutenant, who was standing close by, did not experience the slightest inconvenience, neither was any serious injury sustained by the man or the buildings”.

View looking towards the south, the next station at Pewley Hill was somewhere in the distance:

Chatley Heath was to be the branching point for another chain of semaphore stations, which would have run all the way to Plymouth, however this chain was only completed a short distance after Winchester.

The London to Portsmouth semaphore system ran from 1822 until 1847 when it was made redundant by the coming of the railways and the electric telegraph. The London & South Western Railway connected London to the south coast at Southampton, Gosport and Portsmouth and the new electric telegraph was laid alongside the railway. This provided a far more reliable and cost effective means of sending messages between the Admiralty and the naval dockyard at Portsmouth.

The semaphore line was closed at the end of 1847, and the staff made redundant, which must have been a blow to them as the staff were usually at the end of their naval careers and other opportunities for employment would have been limited.

The views from the tops of the semaphore tower show what a high location this is relative to the surrounding land. As well as the towers of the city shown in an earlier photo, from the top of the tower we can just about see the arch over the Wembley stadium in the distance:

The location of the semaphore stations can often be found in local naming, with Telegraph Hill being used at a couple of the old station locations. there is a Telegraph pub in Putney named after the original shutter telegraph on Putney Heath. There are a number of Telegraph Roads and Telegraph Houses along the route.

The London to Portsmouth semaphore / telegraph route was one of many that were built during the early decades of the 19th century. The admiralty built a number of chains to enable communication with key dockyards.

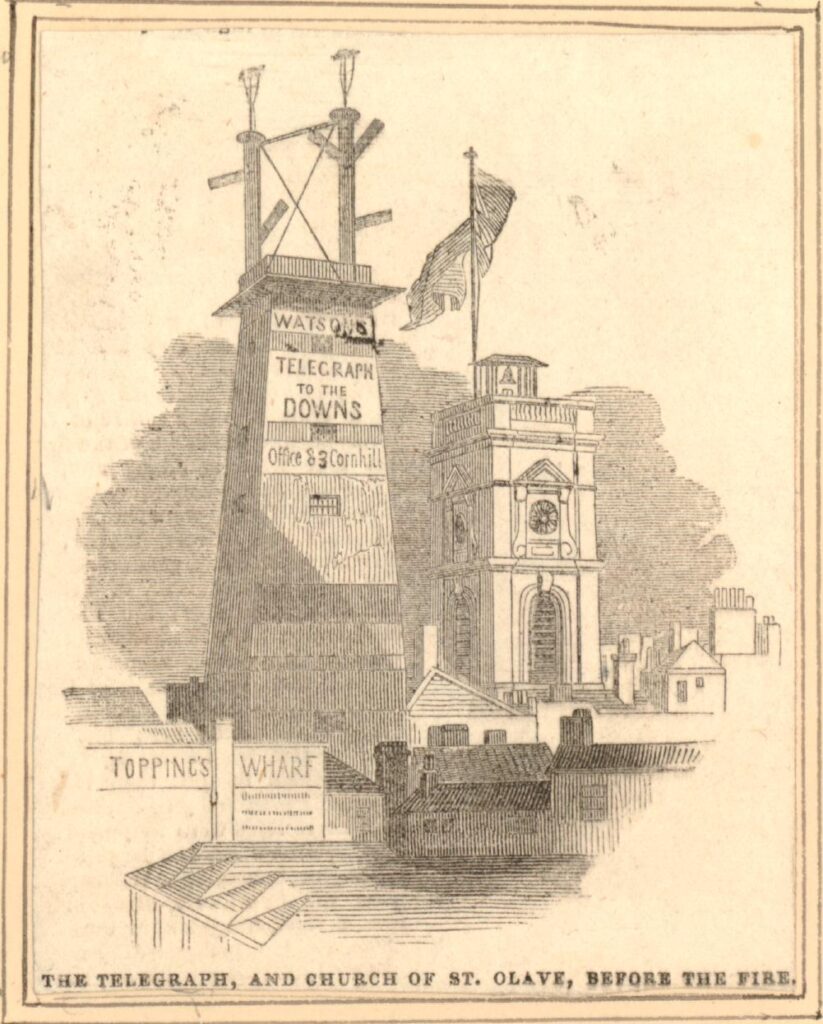

There were also commercial telegraph chains set-up. One, by a Lieutenant Watson was created between Holyhead and Liverpool and reported the names of ships passing Holyhead on their way to the docks at Liverpool. This would enable ship owners to have advance information of when their ships would be arriving in port.

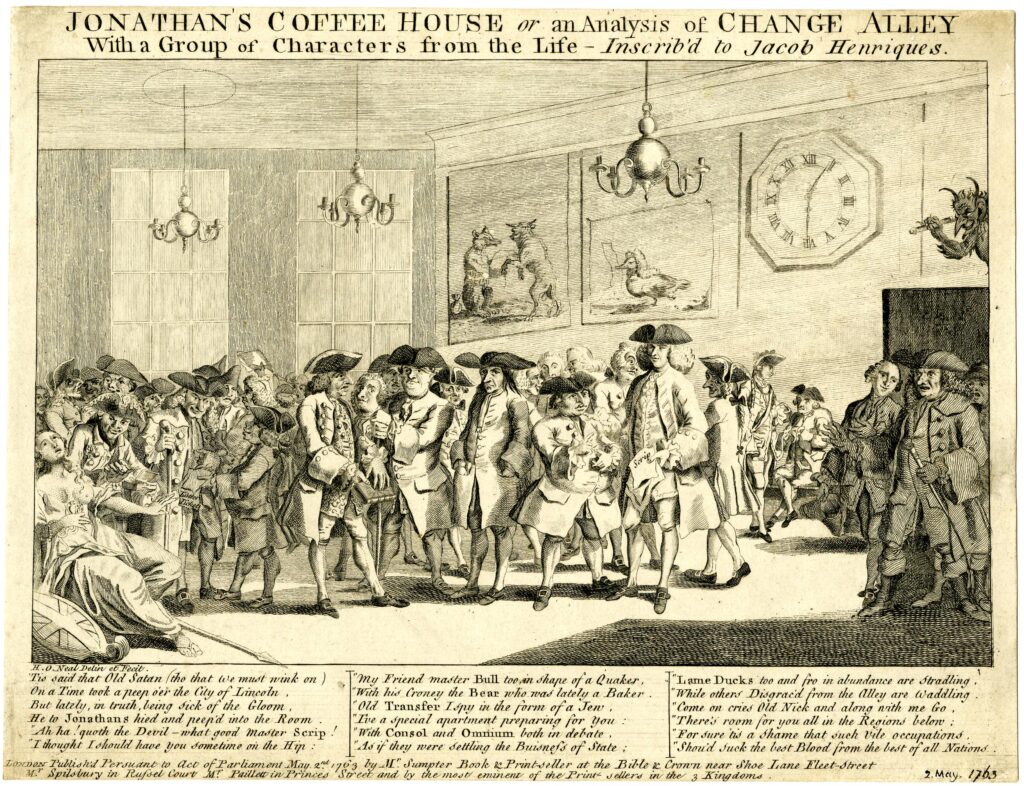

Lieutenant Watson devised his own code for the telegraph system. He may have also been responsible for creating another system from London to the coast. The following print shows Watson’s Telegraph, near Tooley Street (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

This has a similar arrangement to the semaphore route between London and Portsmouth, however it uses two rather than one post, and it appears that one of the posts had two arms at the top. Presumably this arrangement was to allow more complex messages to be sent at a faster rate.

The Chatley Heath semaphore tower is a wonderful reminder of a time, only 200 years ago, when it took hours to send a message the distance from London to Portsmouth, and the technological change that started to speed up communication.

If you fancy a stay in an early 19th century semaphore tower, the page on the Landmark Trust site with information and booking is here.