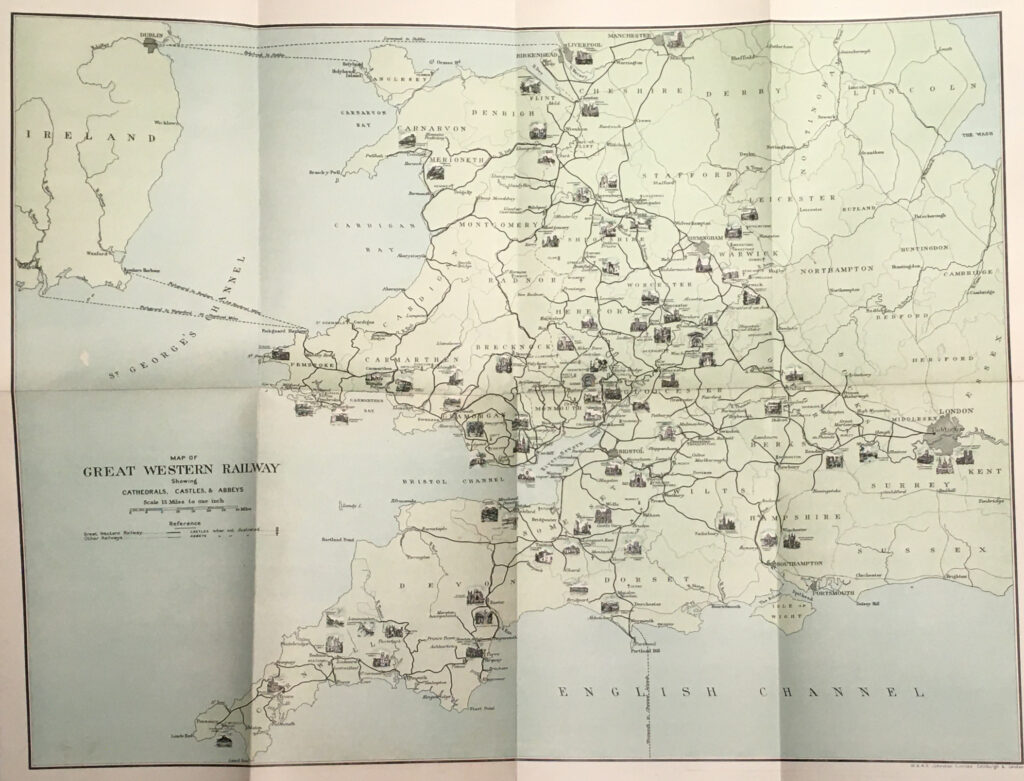

As long term readers of the blog will know, as well as London photos, my father also took many photos from around the country, as after National Service, he along with some friends went on very long cycle rides, staying overnight in Youth Hostels. A popular post-war means of exploring the country,

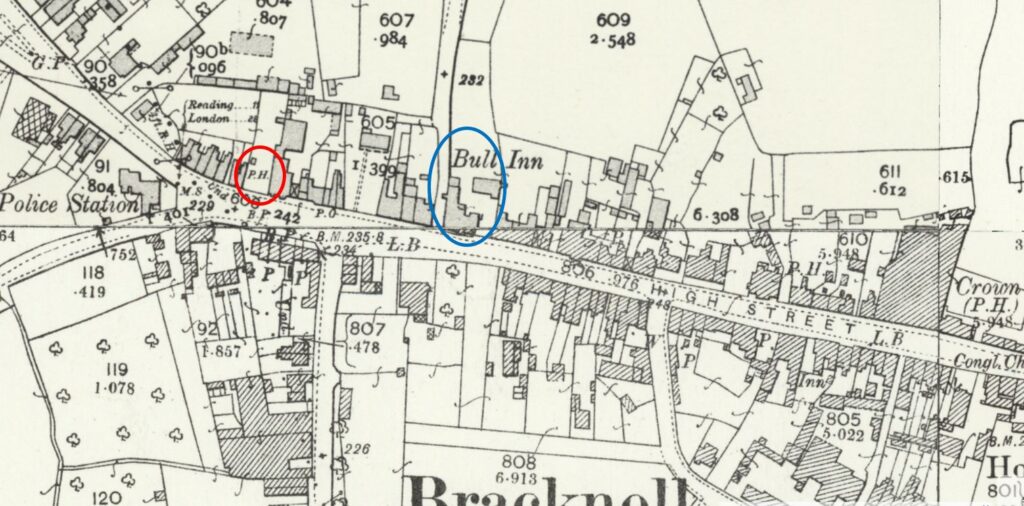

There are two photos which I would not have had any chance of identifying, if he had not left notes for these two:

The note with the photos read “Borley Rectory, 21st July 1952”:

The two photos show what looks like an overgrown field, with no sign of any rectory. The reasons for this will become clear later in the post.

First coming to national attention in 1929, the rectory would soon become know as the most haunted house in England,

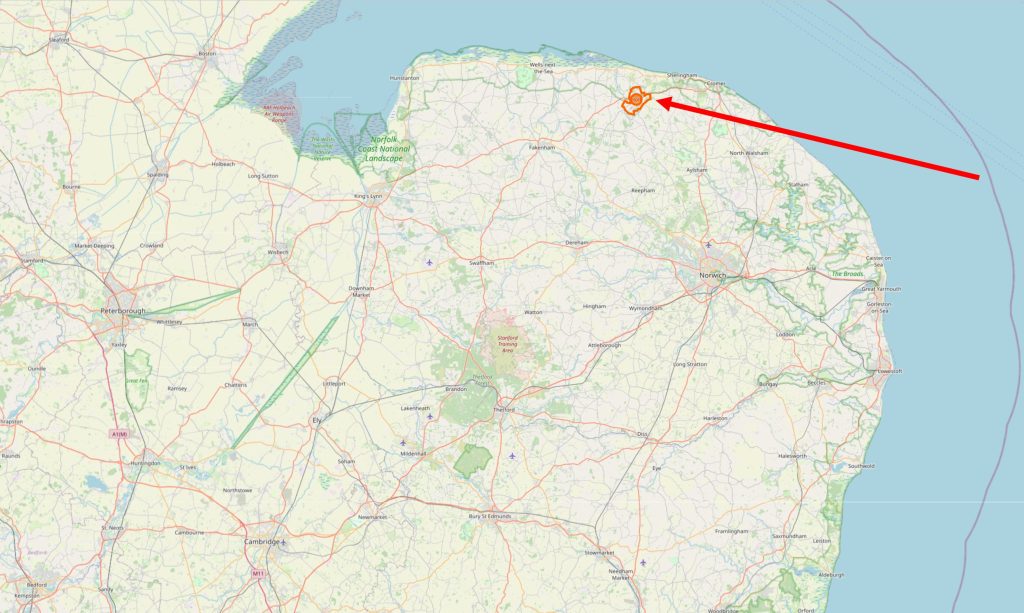

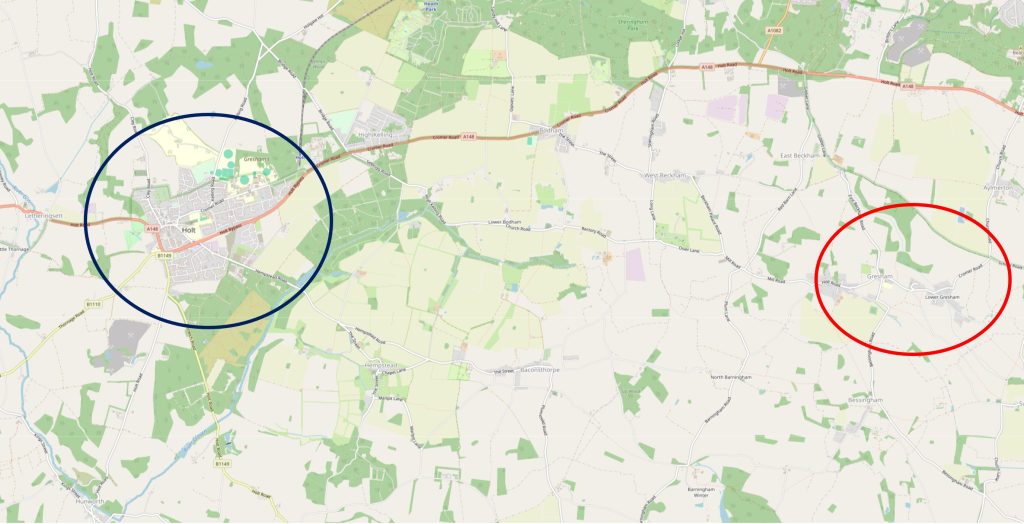

Borley is a very small village in north Essex, to the north-west of Colchester, and the rectory was built in 1863 by the Rev. Henry Bull. It seems to have been known for low level ghostly phenomena for some time, for example on the 28th of July 1900, four sisters of the Rev. Bull saw the figure of a nun on the rectory lawn.

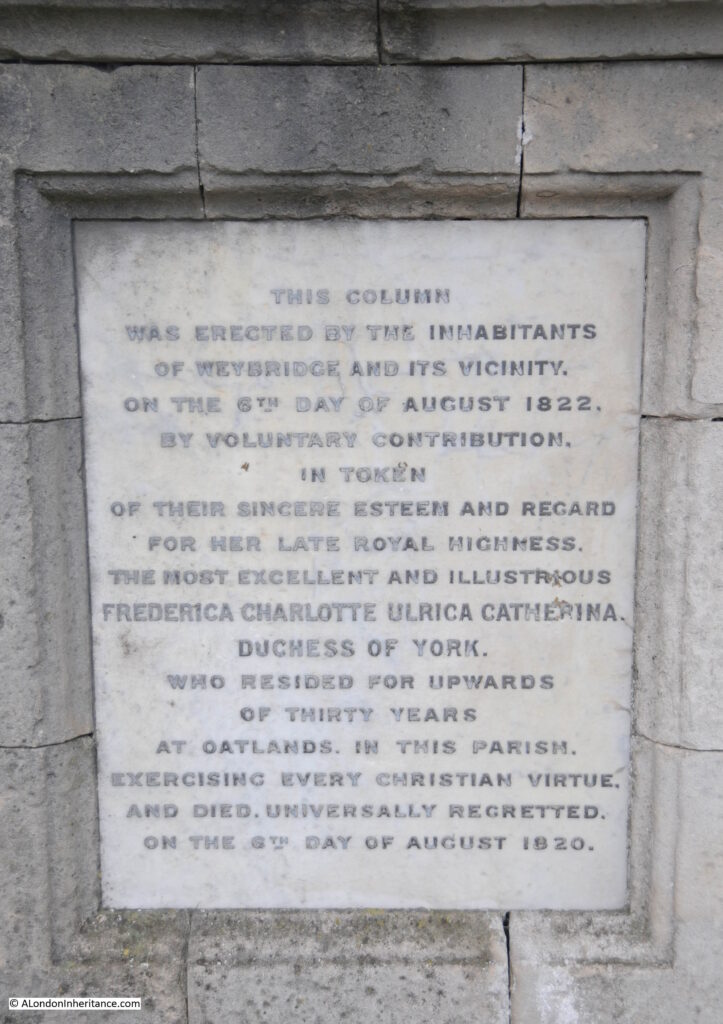

The site on which the rectory was built appears to have been the subject of local legends for many years. In a 1956 report on the Borley hauntings by the Society for Psychical Research, it was noted that:

“According to legend, discredited in 1938, Borley Rectory was built on the site of a 13th century monastery, with a nunnery nearby at Bures. The legend told how an eloping monk and nun were caught and put to death. Apparitions of the nun, the coach in which they fled, and a headless coachman figure in stories current in the late 19th century.”

It is always a headless coachman, and there are numerous examples of this type of apparition from across the country. The legend that the rectory was built on the site of a 13th century monastery seems to have just been a local story, with no foundation in fact.

The Rev. Henry Bull was succeeded by his son Harry, who also became the rector of Borley and whilst he moved to another house in the villages, his father’s sisters still lived in the rectory.

The Rev. Harry Bull died in 1927, and two years later, the Rev. G. Eric Smith took over the living of Borley and moved to the rectory.

The Reverend and his wife were so concerned by the rumours that the rectory was haunted, that they got in touch with the Editor of the Daily Mirror for help with contacting a psychical researcher.

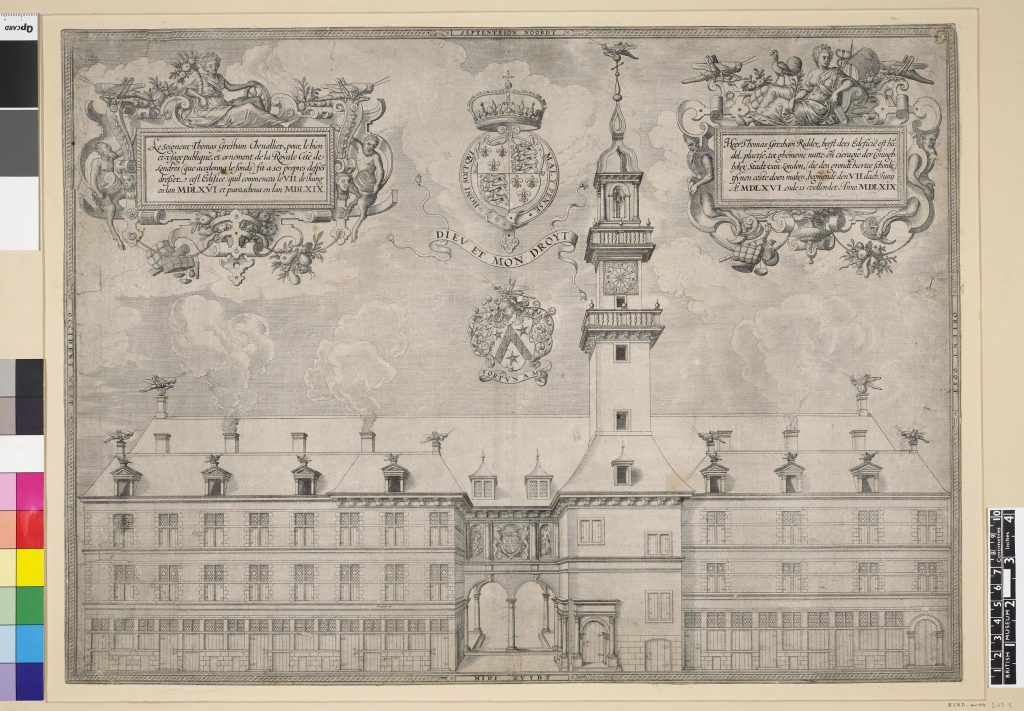

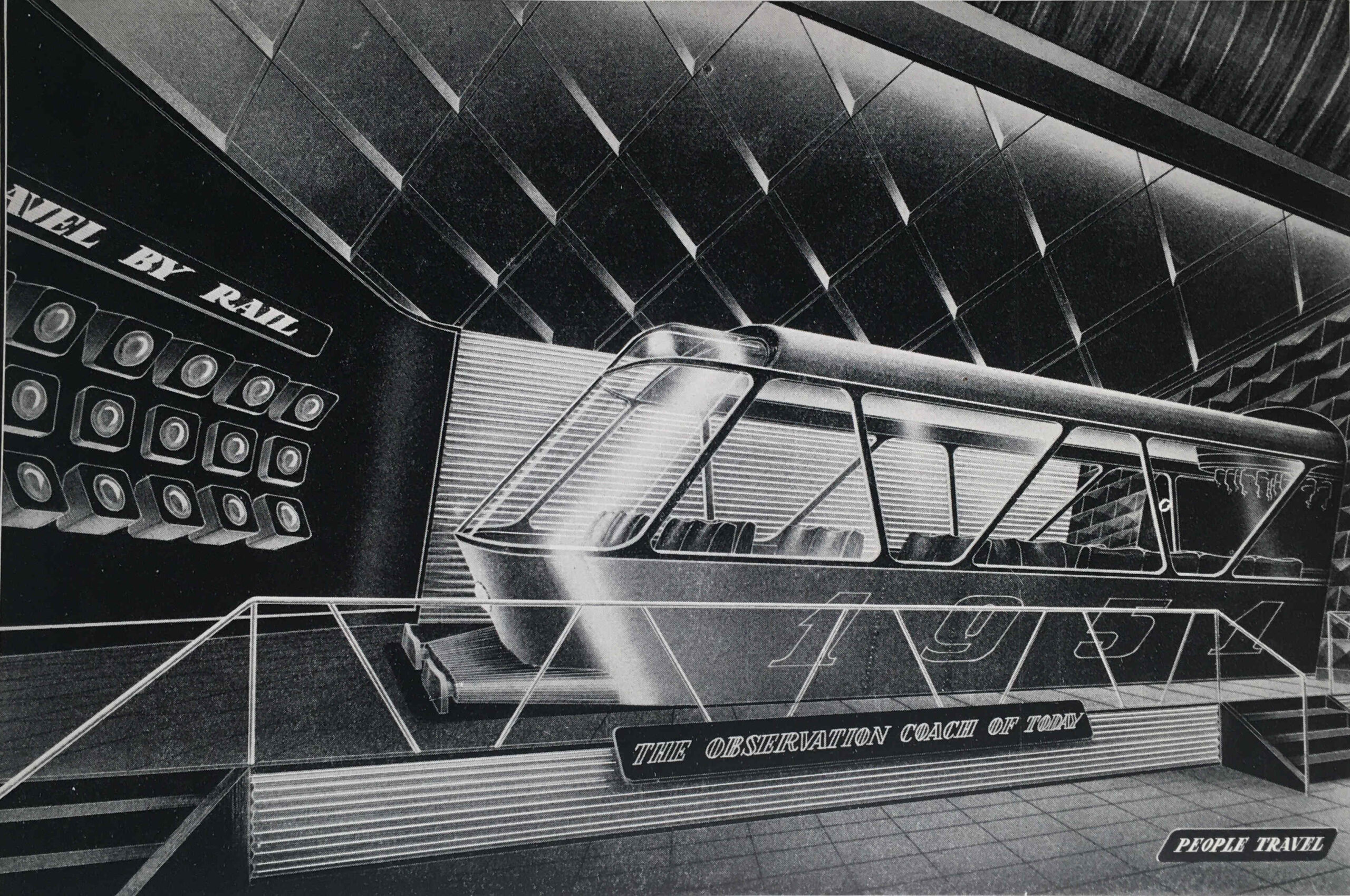

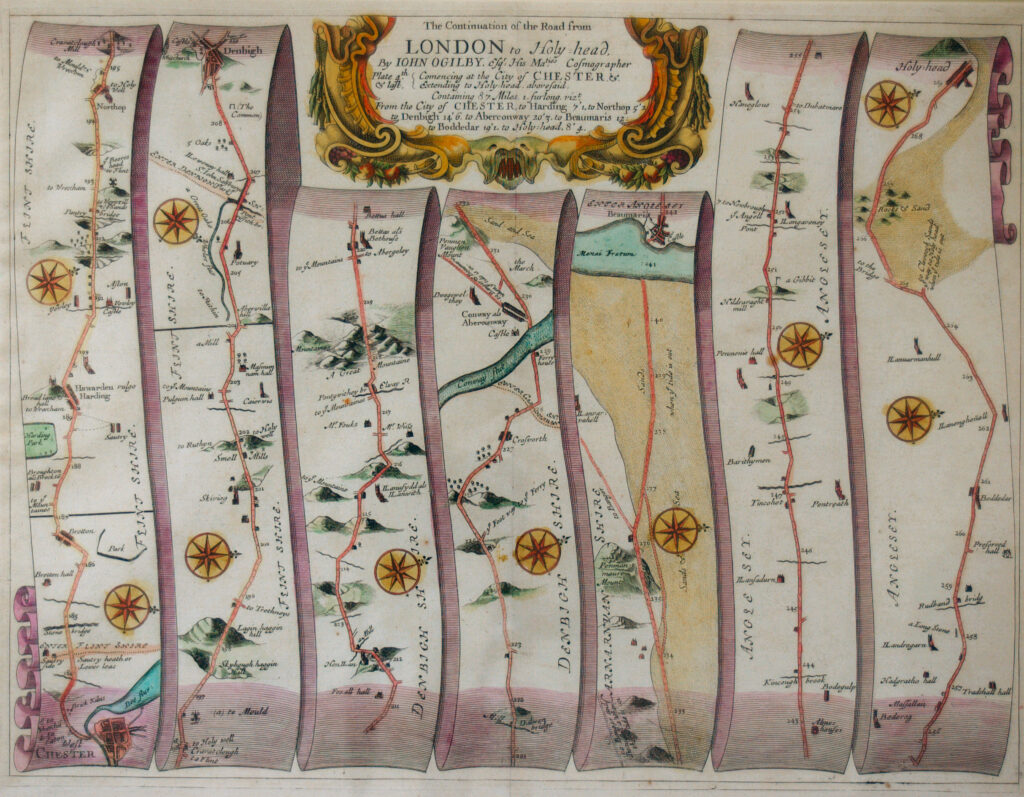

Borley Rectory:

Image source: The End of Borley Rectory by Harry Price, 1946.

Following the Rev. Smith’s request to the Daily Mirror, the newspaper arranged for Harry Price to visit the rectory. In the 1920s Price was one of the best known and most prolific physic journalists of his generation, and he did expose the fraudulent activities of many mediums, so he had some credibility in the research of ghostly phenomena.

The Daily Mirror published an article on the 12th of June 1929 announcing that Harry Price was being sent to investigate, and also published details from a witness who had experienced the phenomena that apparently plagued the rectory:

“HAUNTED ROOM IN A RECTORY. OLD SERVANT’S STORY OF A MIDNIGHT VISITOR. LAYING THE ‘GHOST’. Psychic Expert to Investigate Suffolk Mystery.

One of the leading British psychological experts is to investigate the mystery of the ‘ghost’ of Borley Rectory, Suffolk, described in the Daily Mirror.

In an effort to lay the ghost by the heels, and either prove or disprove its existence, Mr. Harry Price, honorary director of the National Laboratory of Psychic Research, is to conduct the investigation. Mr. Price is famous in this country for his research work and his exposures of psychic phenomena.

Striking confirmation of the weird experiences of the present and past occupants of the rectory is forthcoming from Mrs. E. Myford of Newport, Essex. In a letter to the Daily Mirror Mrs. Myford reveals that forty-three years ago, when she was a maid at the rectory, similar phenomena were quite openly discussed in the rectory and neighbourhood.

Much of my youth was spent in Borley and district, with my grandparents, writes Mrs. Myford, and it was common talk that the rectory was haunted. Many people declared that they had seen figures walking at the bottom of the garden. I once worked at the rectory, forty-three years ago, as an under-nursemaid, but I only stayed there a month, because the place was so weird.

The other servants told me my bedroom was haunted, but I took little notice of them because I knew two of the ladies of the house had been sleeping there before me. But when I had been there a fortnight something awakened me in the dead of night. Someone was walking down the passage towards the door of my room, and the sound they made suggested that they were wearing slippers.

As the head nurse always called me a six o’clock, I thought it must be she, but nobody entered the room, and I suddenly thought of the ‘ghost’. The next morning I asked the other four maids if they had come to my room, and they all said that they had not and tried to laugh me out of it.

But I was convinced that somebody or something in slippers had been along the corridor, and finally I became so nervous that I left. My grandparents would never let me pass the building after dark, and I would never venture into the garden or the wood at dusk.”

Then on the 14th of June 1929, the Mirror published an update, covering the first visit of Harry Price to the rectory:

“WEIRD NIGHT IN ‘HAUNTED HOUSE’ SHAPE THAT MOVED ON LAWN OF BORLEY RECTORY. STRANGE RAPPINGS. ARTICLES FLYING THROUGH THE AIR SEEN BY WATCHERS.

There can no longer be any doubt that Borley Rectory, is the scene of some remarkable incidents.

Last night Mr. Harry Price, director of the National Laboratory for Psychical Research, his secretary, Miss Lucy Kaye, the Rev. G.E. Smith, Rector of Borley, Mrs. Smith and myself were witnesses to a series of remarkable happenings.

All these things occurred without the assistance of any medium or any kind of apparatus, and Mr. Price, who is a research expert only and not a spiritualist, expressed himself puzzled and astonished at the results. To give the phenomena a thorough test, however, he is arranging for a séance to be held in the rectory with the aid of a prominent London medium.

The first remarkable happening was the dark figure I saw in the garden. We were standing in the summer house at dusk watching the lawn when I saw the apparition which so many claim to have seen, but owing to the deep shadows it was impossible for one to discern any definite shape or attire. But something certainly moved along the path along the other side of the lawn, and although I immediately ran across to investigate, it had vanished when I reached the spot.

Then as we strolled toward the rectory discussing the figure, there came a terrific crash and a pane of glass from the roof of a porch hurtled to the ground. We ran inside and upstairs to inspect the rooms over the porch, but found nobody. A few seconds later we were descending the stairs, Miss. Kaye leading and Mr. Price behind me, when something flew past my head, hit an iron stove in the hall, and shattered.

With our flashlamps we inspected the broken pieces and found them to be sections of a red vase which, with its companion, had been standing on the mantlepiece of what is known as the blue room and which we had just searched.

We sat on the stairs in darkness for a few minutes and just as I turned to Mr. Price to ask him whether we had waited long enough something hit my hand.

This turned out to be a common mothball, and had dropped from apparently the same place as the vase. I laughed at the idea of a sprit throwing mothballs about, but Mr. Price said that such methods of attracting attention were not unfamiliar to investigators. Finally came the most astonishing event of the night.

From one o’clock until nearly four in the morning all of us, including the rector and his wife, actually questioned the spirit or whatever it was and received the most emphatic answers.

A cake of soap on the washstand was lifted and thrown heavily on to a China jug standing on the floor with such force that the soap was deeply marked. All of us were at the other side of the room when this happened. Our questions which we asked out loud, were answered by raps apparently made on the back of a mirror in the room, and it must be remembered that no medium or spiritualist was present.”

The reference in the above articles to the “National Laboratory for Psychical Research” implies the credibility of an independent research organisation, however the “National Laboratory” was the creation of Harry Price, and of which he was director.

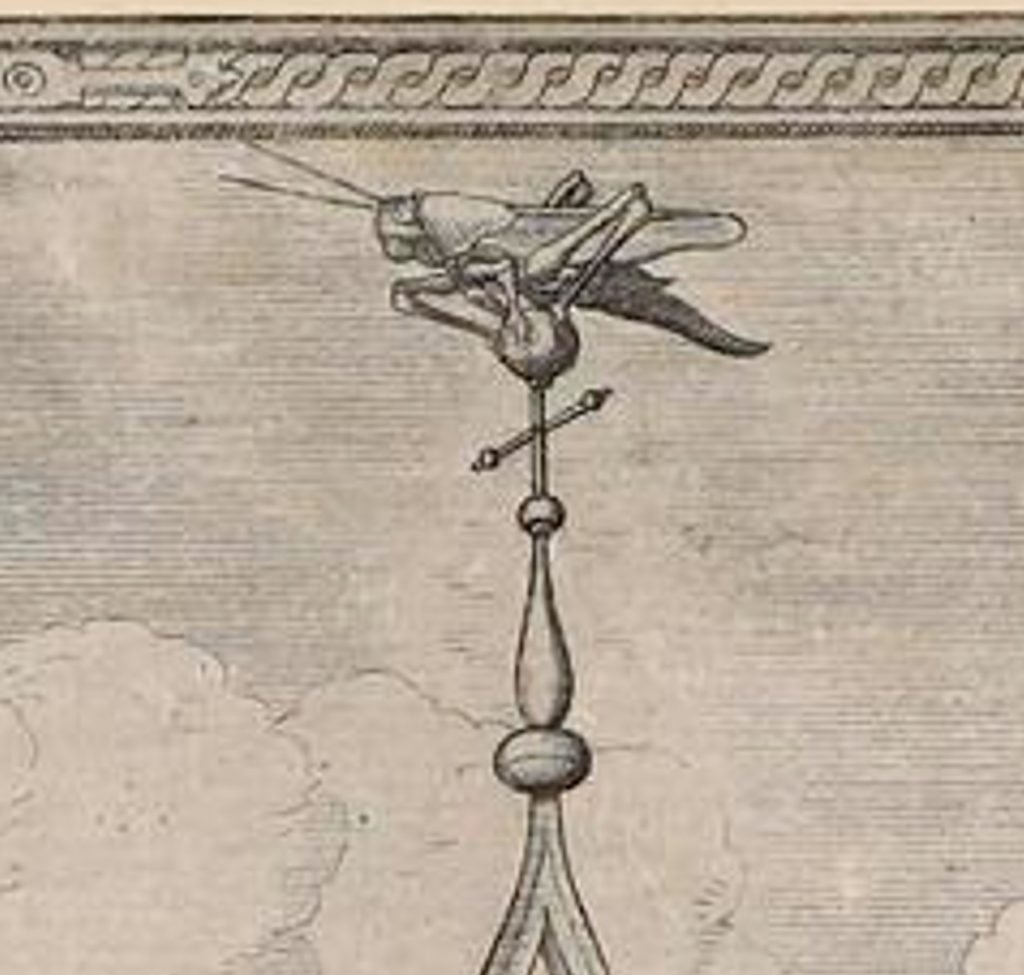

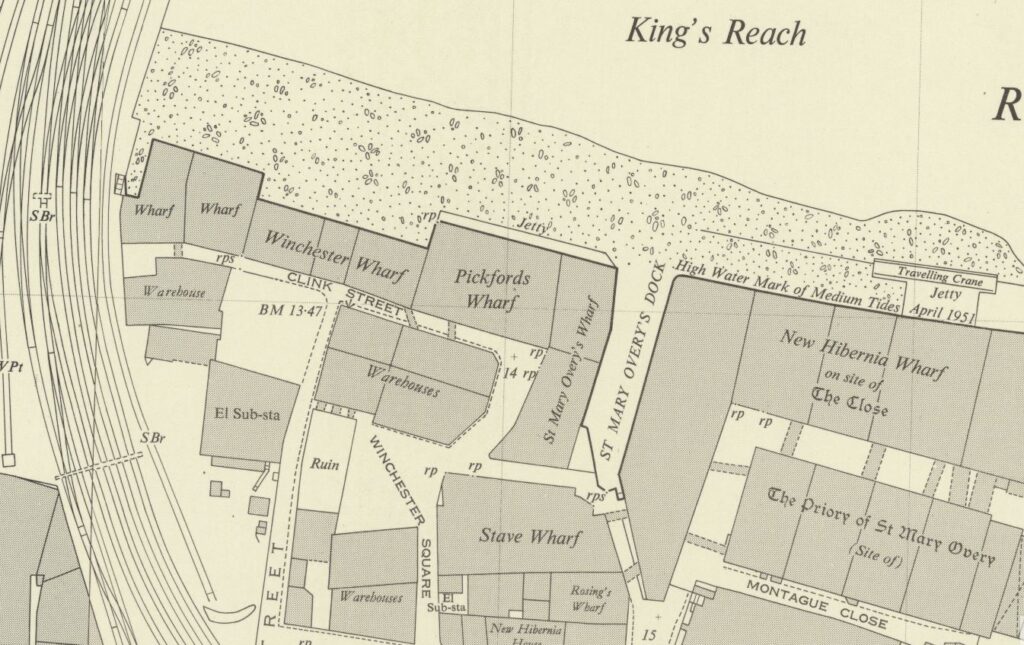

The entrance to the rectory from the road, showing that it was a more substantial building than appears from just a view from the front:

Image source: The End of Borley Rectory by Harry Price, 1946.

Perhaps it should not have been a surprise that as soon as a psychic researcher, sent by a national newspaper got involved, that the phenomena in the rectory became more intense.

The Rev. Smith and his family left the rectory and moved to Long Melford, not just because of the ghostly happenings, but also the “nuisance created by the publicity”.

All then went quiet. The Rev. Smith and his family moved to a new parish in Norfolk, and Borley remained without a rector until the 16th of October 1930 when the Rev. Lionel A. Foyster moves in with his family, and the ghostly phenomena start again, this time with increasing violence.

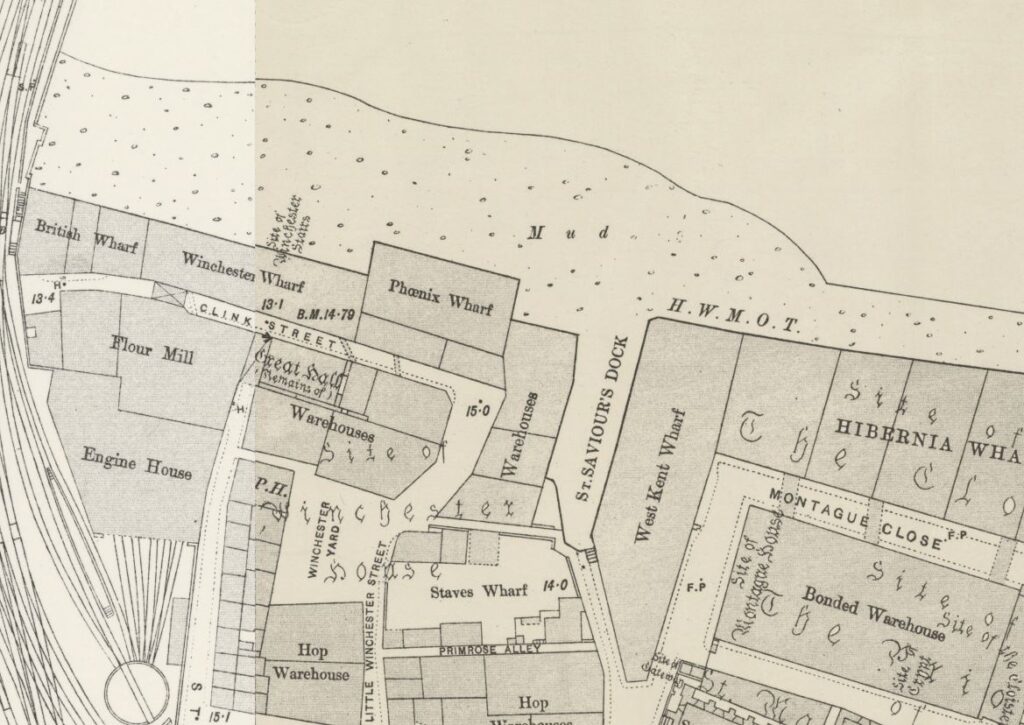

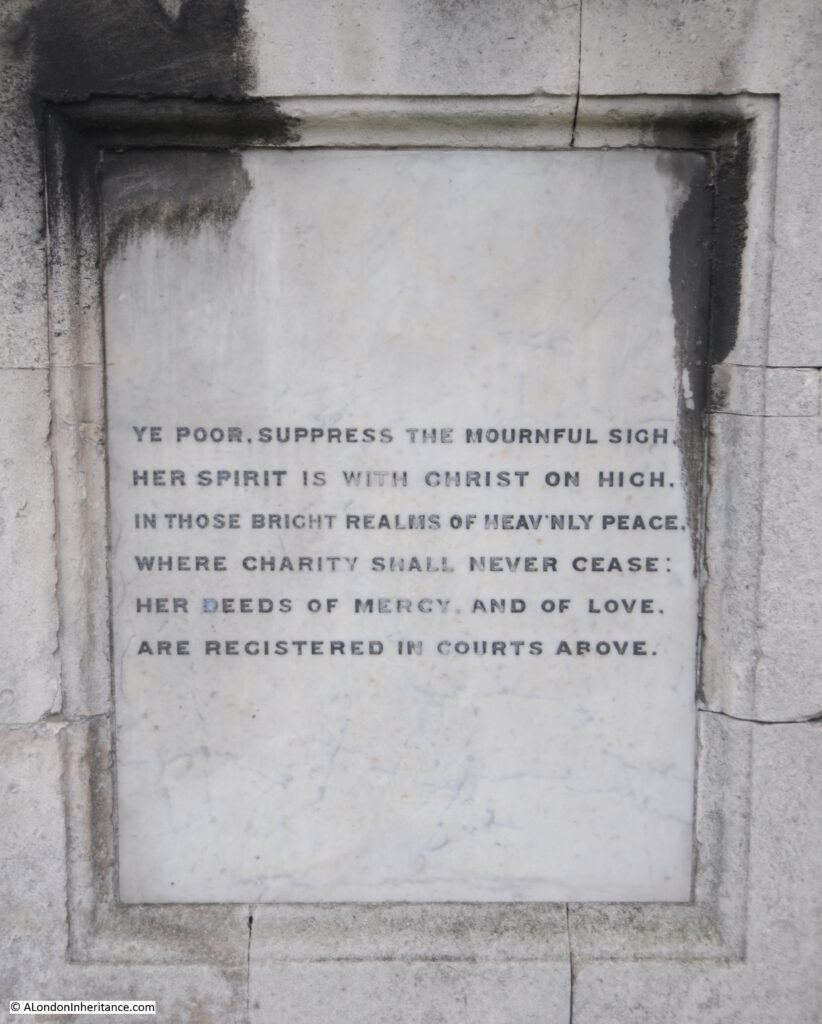

One of the phenomena witnessed during the Foyster’s time in the rectory was wall writing, where appeals were made to Marianne (the wife of Rev. Foyster):

Image source: The End of Borley Rectory by Harry Price, 1946.

Rev Foyster was a cousin to the Rev. Harry Bull, and the sisters were still living close by as they got in contact with Harry Price to ask him to make a return visit.

An exorcism was held, and the phenomena abruptly cease.

In October 1935, the Foyster family move out, and the rectory is left unoccupied. The next rector of Borley receives the Bishop’s permission to live elsewhere, then the livings of Borley and nearby Liston are combined, making the rectory at Borley redundant.

In May 1937 Harry Price again visited the rectory and decided to rent the building for a year. He advertised in The Times for people to join him in a comprehensive investigation, and 48 individuals are signed up, with a rota of visits to monitor the rectory.

One of those involved arranged for a planchette to be used. A planchette was a heart shaped piece of wood, mounted on wheels, and with a hole for a pencil. Those at the sitting where the planchette was used, would gently put their hands on the planchette, and it would move, guided by any spirits who wished to communicate. The pencil writing the results on paper below the planchette.

This method was used between October and November 1937, and the scripts generated by the planchette provided considerable details about the nun from the original legends. Her name was given as either Mary or Marie Lairre, and she had come from France. The scripts claim that she had been murdered, she was a novice and died at the age of 19 in 1667, and that her remains could be found at the end of the wall or in the well.

Later, in 1943, Price excavated the wells in the cellars of the rectory and found human bones at the bottom of the well. They were assumed to be those of the nun and in May 1945 they were buried in the churchyard at Liston.

Throughout Price’s tenancy of the rectory, strange phenomena continued to be observed and felt. There were cold spots, strange noises, taps, bangs, footsteps and whistles, horses hoofs, lights etc.

In May 1938, Price’s tenancy of the rectory ends, and the rectory is purchased by a Captain Gregson, who also reported minor phenomena, as did visitors to the old rectory.

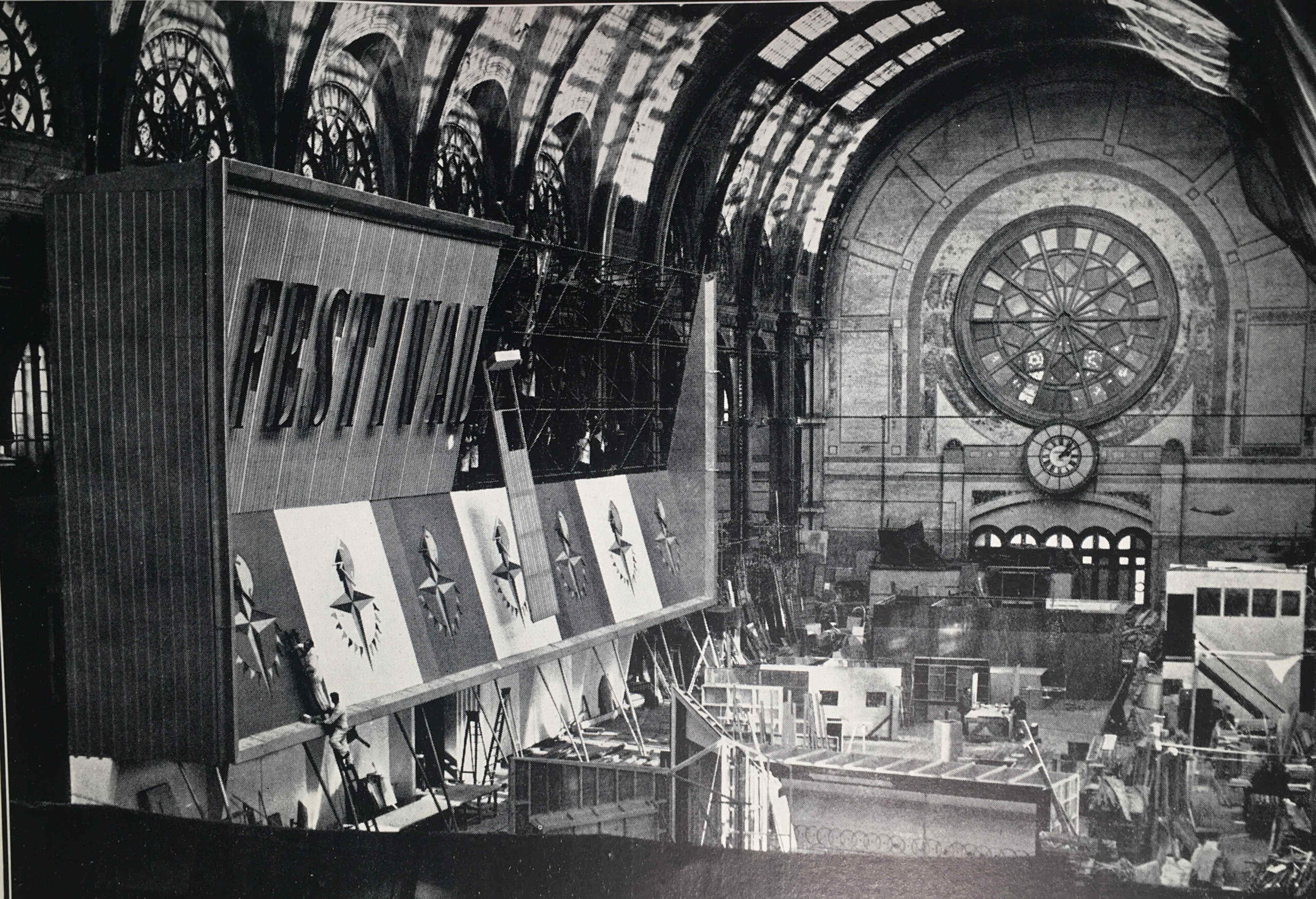

During the night of the 27th of February 1939, Borley Rectory is destroyed by fire. During the fire, strange phenomena continue, including the sighting of strange figures walking in the flames, and strange happenings continue to be reported in the months after the fire, although the rectory is now a ruin:

Image source: The Haunting of Borley Rectory, Volume 51, Part 186 Society for Psychical Research

The saga at the rectory had received continuous national coverage during the 1930s, and in 1940 Price capitalised on the public’s interest in the story of the rectory with the book “The Most Haunted House in England”.

The book resulted in many more people getting in contact with Price, to report their strange experiences at the site.

The remains of the rectory were demolished in 1944, however interest in the story continued and many people still visited the site (including my father and his friends), and some people also held seances on the site.

The following photo shows an aerial view of the site, with the location of the demolished rectory highlighted by the arrow. The photo helps locate my father’s photos as the second photo at the top of the post has some low rise buildings in the background, and these can be seen in the centre of the following photo:

Image source: The Haunting of Borley Rectory, Volume 51, Part 186 Society for Psychical Research

In 1946, Harry Price published his second book on the subject “The End of Borley Rectory”, repeating as the sub-title “The Most Haunted House in England”.

Two years later, on the 29th of March, 1948 Harry Price died of a heart attack in his home at Pulborough in West Sussex. His papers and archive were deposited with the University of London.

There had always been rumours about the phenomena observed at Borley Rectory, and after Price’s death, these rumours started to gain greater credibility.

In 1948, a Mr Charles Sutton who was on the staff of the Daily Mail accused Harry Price of fraudulently producing many of the phenomena observed when Sutton visited with Price in 1929, although quite why he had left it so long to make public these claims is unknown.

In 1949, Mrs Smith, the wife of the Rev. G. Eric Smith, who took over the living of Borley and moved into the rectory in 1928, wrote to the Daily Mail asserting her disbelief that the rectory was haunted.

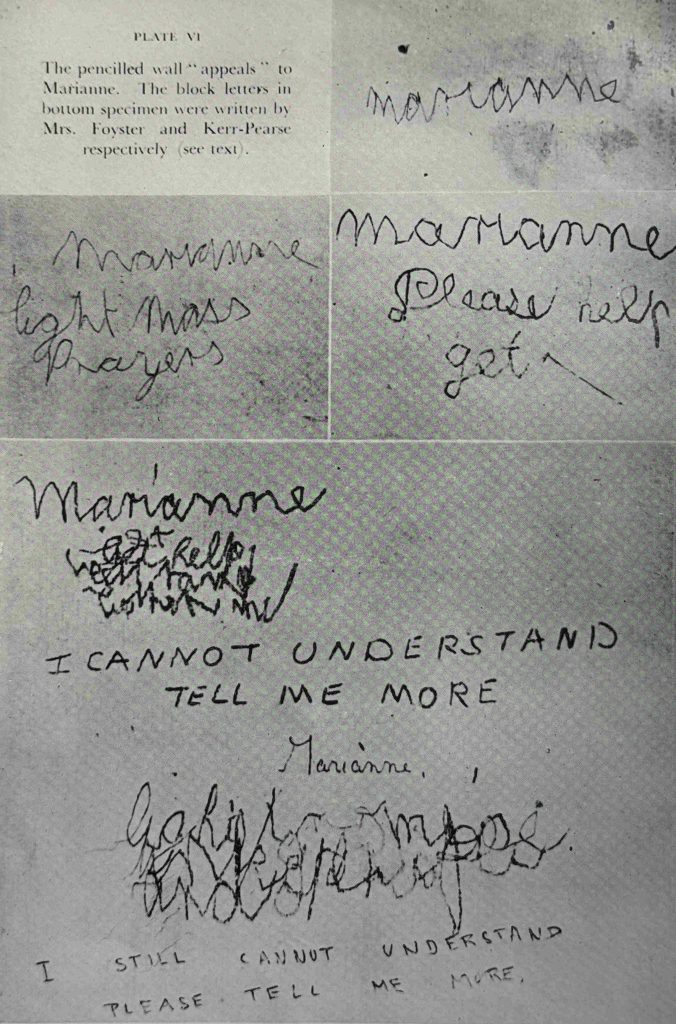

In 1956, the Society for Psychical Research (still going and “Founded in 1882, the SPR was the first organisation to conduct scholarly research into human experiences that challenge contemporary scientific models”), published the results of a “Critical Survey of the Evidence” into the haunting of Borley Rectory in their Proceedings (Volume 51, Part 186, January 1956):

The report is an in depth and comprehensive survey of the haunting, and looks at all the evidence available, although it does make the point that the evidence was not of the type that would stand in a court of law, as the evidence mainly consisted of the reports of all those who had witnessed phenomena, rather than tangible evidence of a supernatural cause.

The rectory was large and had acoustic properties that could have explained many of the strange noises.

The Rev. Harry Bull, as well as being the rector of Borley also had an interest in spiritualism, and this could have influenced both his view of the rectory, as well as how the phenomena were perceived by others.

The report also looked at Harry Price, who was described as possessing a “complex personality whilst to others the motives which inspired him were simple and clear-cut. He was a man of abounding energy and had a wide range of interests and a practical acquaintance with a good many technical matters from numismatics to radio communication and conjuring. Trained as an engineer, he ran his own amateur workshop and some of his apparatus and gadgets were of first class workmanship”.

Whilst many of these skills could have been used to create the phenomena observed at the rectory, the report states that there is no firm evidence to suggest that Price did this, and with his death, and the distance of time, it was impossible to prove.

The report does refer to his career as a journalist on the subject, and that it was possible to regard Price as “a brilliant if cynical journalist who used the material gathered in his laboratory or in the field in such a way that its publicity value was highest. As we have seen, if the material lacked sensational elements it would seem that he was prepared at times to provide these himself. On the other hand, his motives may have been more complex; he may have thought that there was some genuine basis on which to build his stories, and that, by supplying what he thought to be the proper psychological milieu, the genuine elements could easily emerge”.

The report also focuses on the influence of suggestion, and how, “once the mind has been affected, belief can be strengthened and simple events misinterpreted in order to fit them into the desired pattern”.

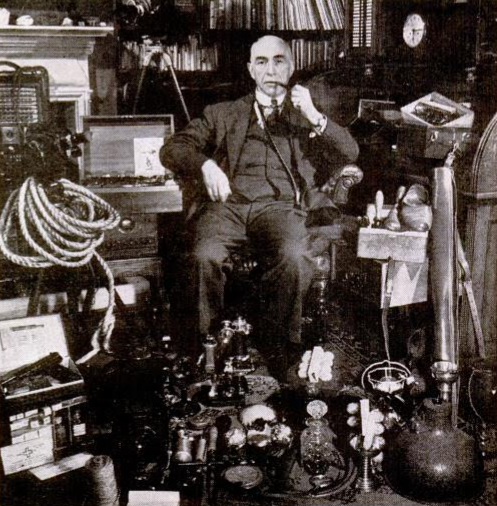

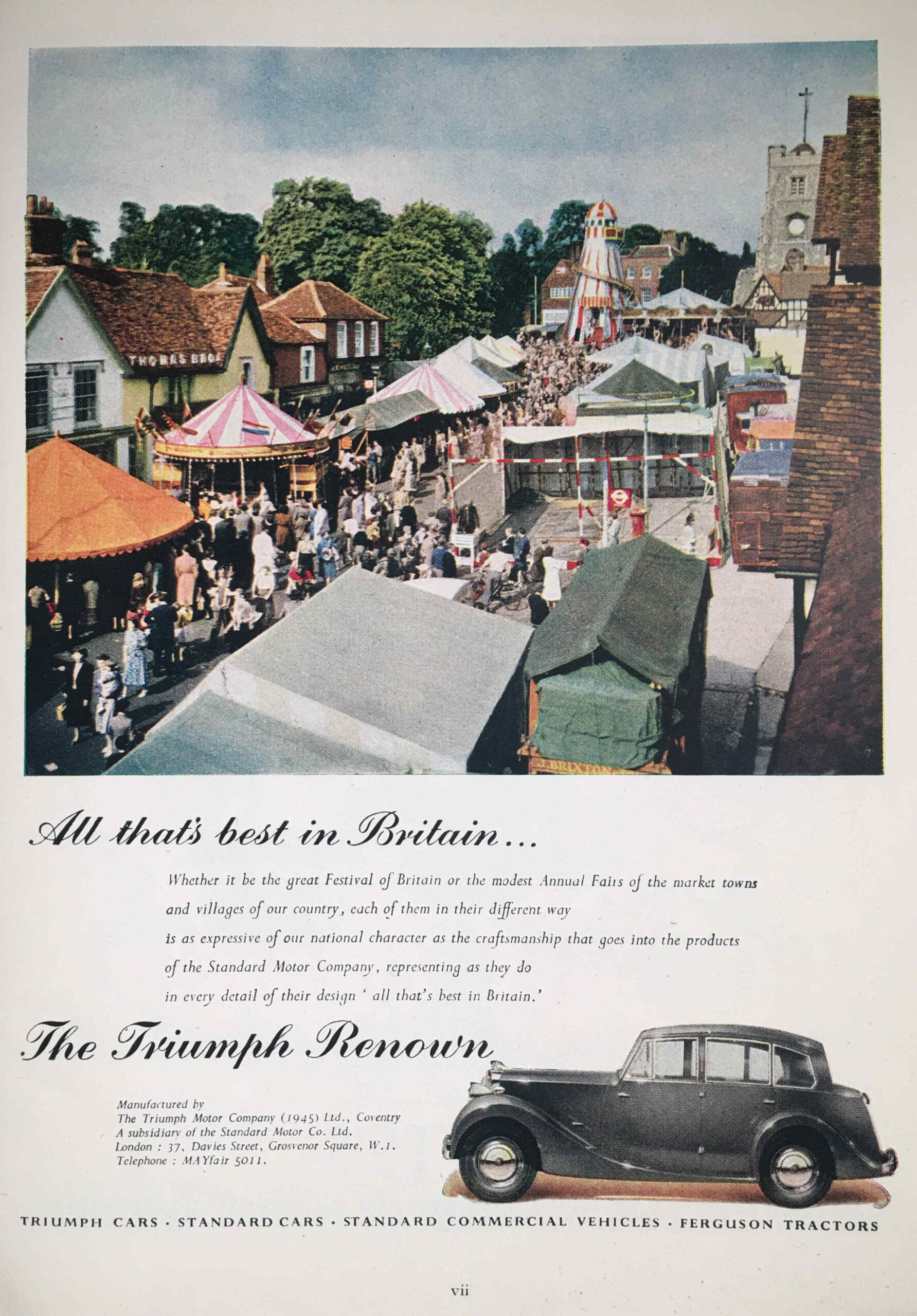

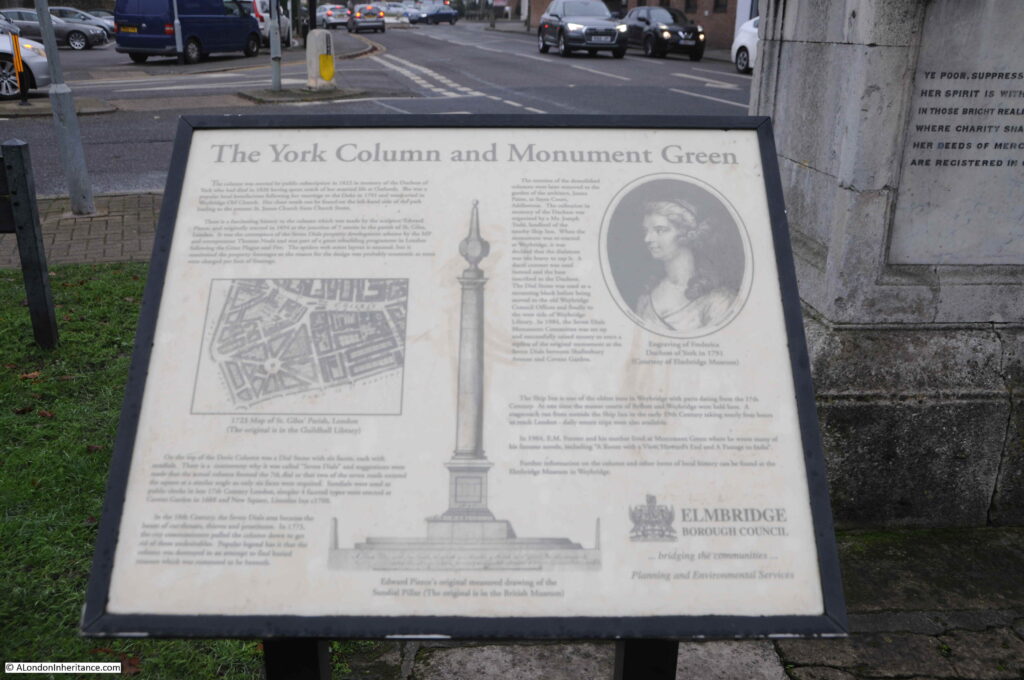

Harry Price surrounded by items from his ghost hunting kit:

Attribution: Noel F. Busch, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

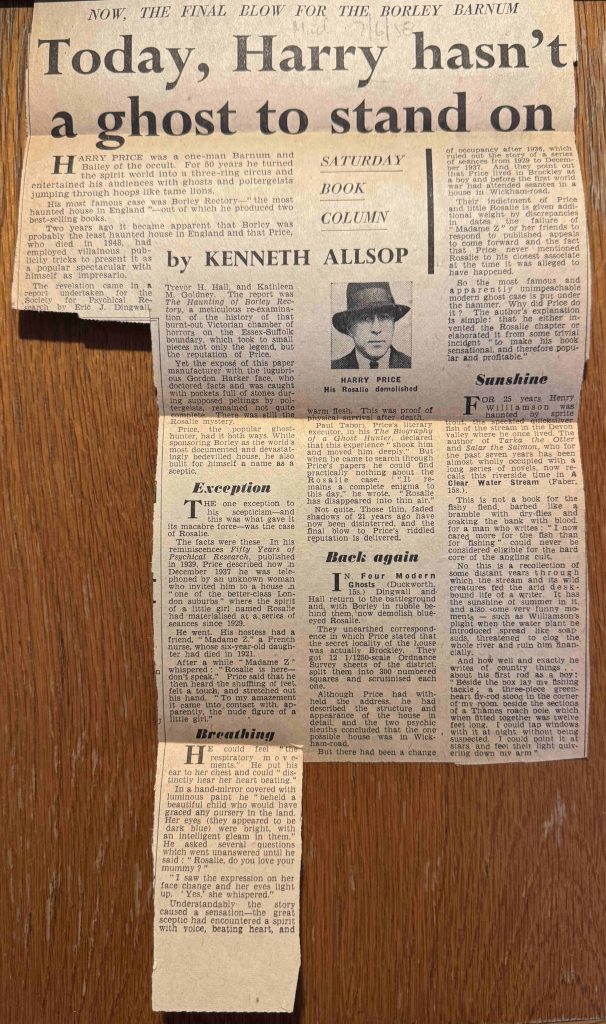

My father had a copy of the book “The End of Borley Rectory” by Harry Price, and inside there is a cutting from the Daily Mail from the 7th of June, 1958, with the headline “Today, Harry hasn’t a ghost to stand on”.

The article refers to the 1956 Society for Psychical Research report as demolishing the Borley haunting, and then looks at a new book which challenges one of Price’s other notable cases, that of a young girl named Rosalie who appeared during a séance after Price was invited to “one of the better class London suburbs“:

Despite all the challenges to the authenticity of the Borley hauntings, stories about the old rectory and the site continued for long after Price’s death. In 1954, two years after my father’s visit, there were still newspaper articles being published. One full page article ended with the following:

“Recently I stood in the long grass which has grown over the foundations of the Rectory and talked with a man who for the last three and a half years has lived in the coach-house which escaped the fire.

Mr. Williams is a retired engineer who keeps a chicken farm there. Quiet, matter of fact, and the least mystical person I have ever met, he is not normally at all forthcoming about the haunting. Publicity, he knows, will only bring more coach-loads of curious sightseers and more mediums who will fall into trances by the Nun’s Walk.

But he admits, frankly and quite unemotionally, that he has experienced things which have no normal explanations.

He told me of how he had sometimes woken in the night to find a light – a glow he called it – hovering in his bedroom and that once he heard quite distinctly footsteps following him across the courtyard at the back of his house. He turned round, but there was no one behind him. Suspecting a trick, he ran round the corner of the house. Still no one.

Had he seen the nun? Mr. Williams took his time before answering, and then said, slowly; ‘Well, I think perhaps I may have. I was in one of the chicken houses at the time. It was broad daylight and I saw a figure pass the window, – just a vague outline, really, you couldn’t say it was a man or woman – and then disappear.

When? Oh, last summer that was – just before the chicken-house was burnt down.”

And with that, can I wish you a very happy Christmas, and if you do get any strange noises, lights, or apparitions of nun’s at this dark time of year – I suggest you do not contact the national press and ask for the assistance of a psychical researcher.