I ran out of time this week to complete the research and writing of the London post I had planned, so as it is summer, how about a trip to Kent, to visit the village of Biddenden, and discover the strange story of the Biddenden Maids.

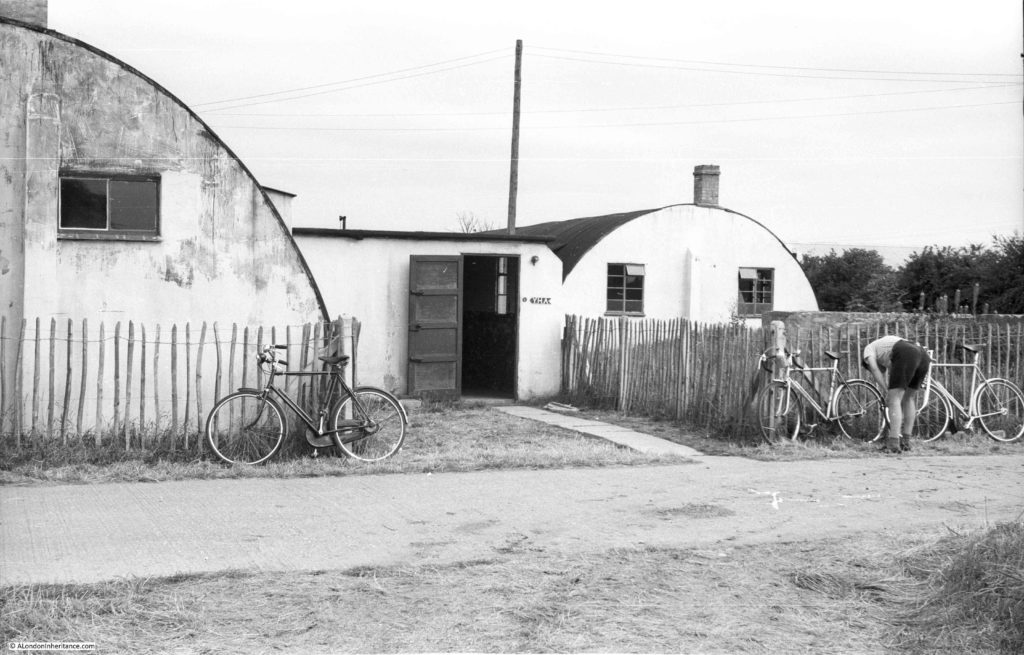

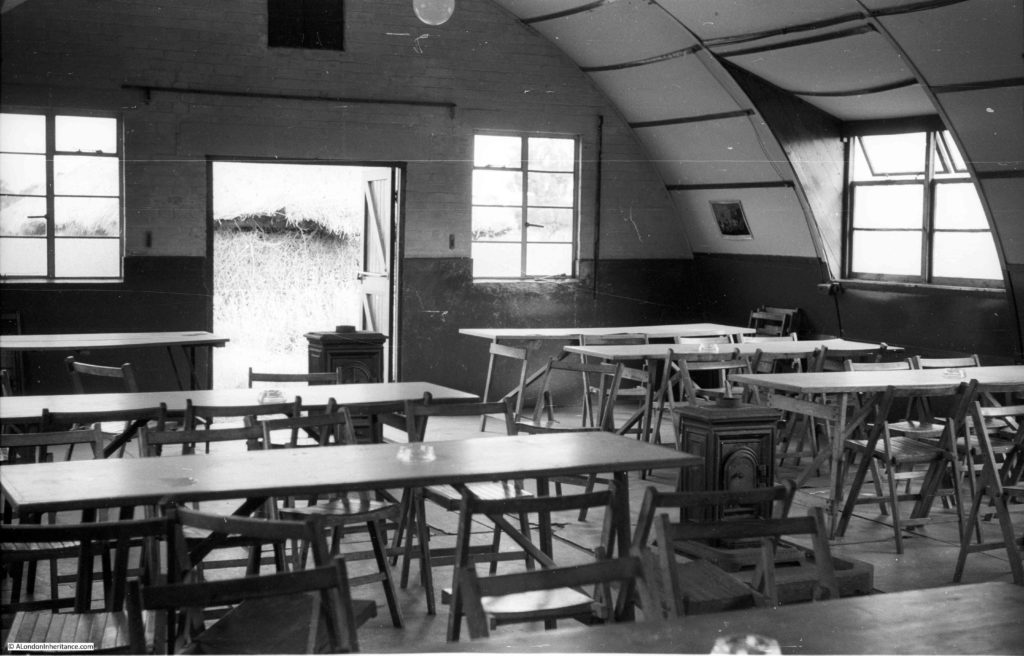

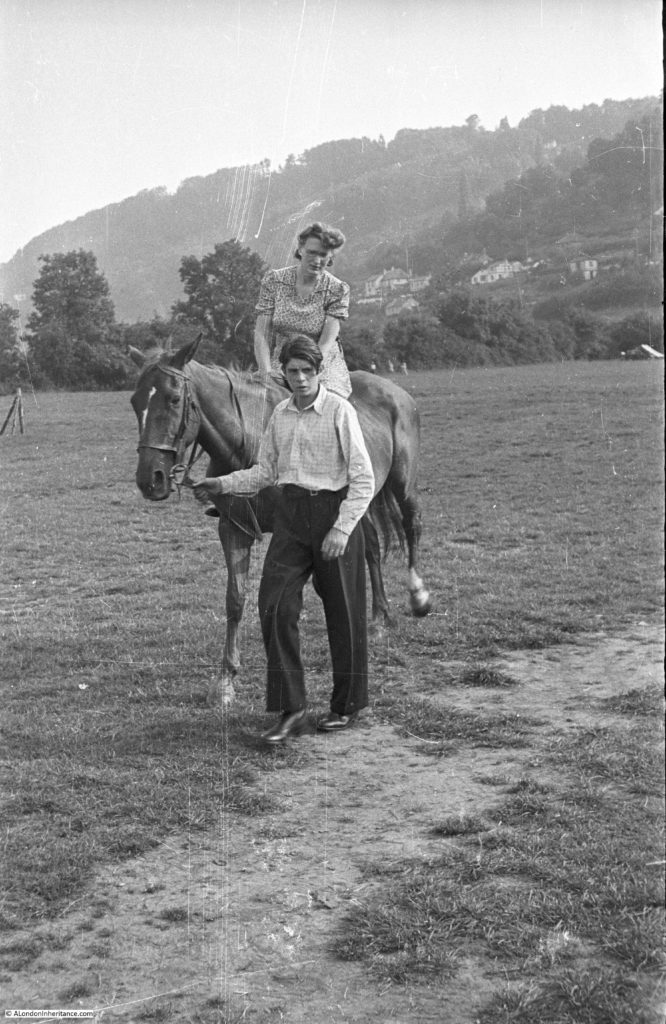

This is not a random choice. As long term readers of the blog will know, as well as London, my father took lots of photos whilst cycling around the country and staying in youth hostels. This was with friends from London, and from his period of National Service.

I am also trying to visit the location of as many of these photos as possible, and take an updated photo to mirror the original.

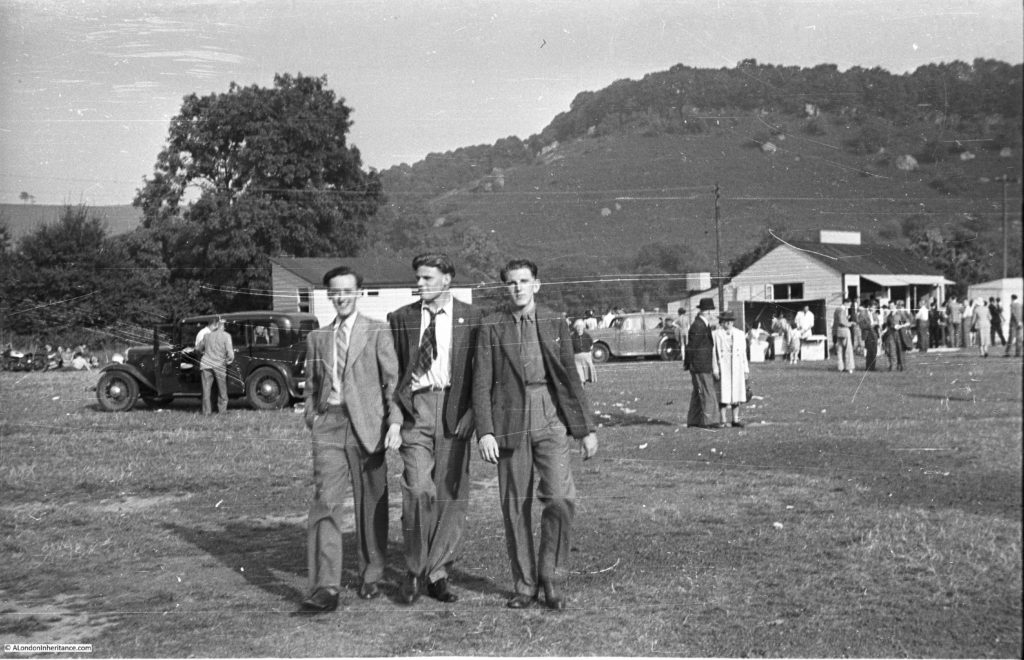

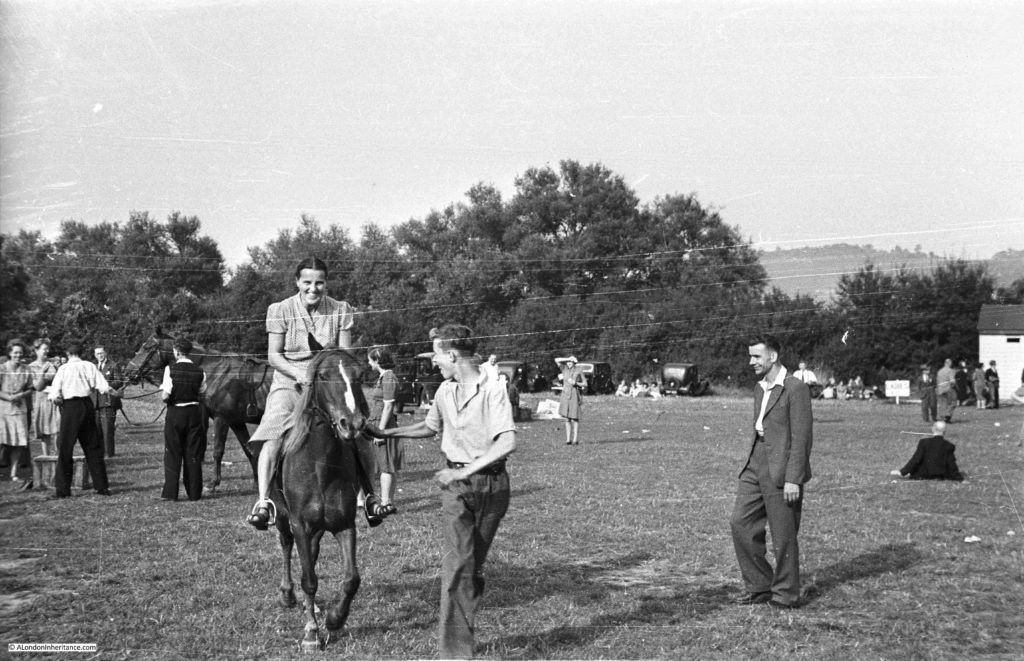

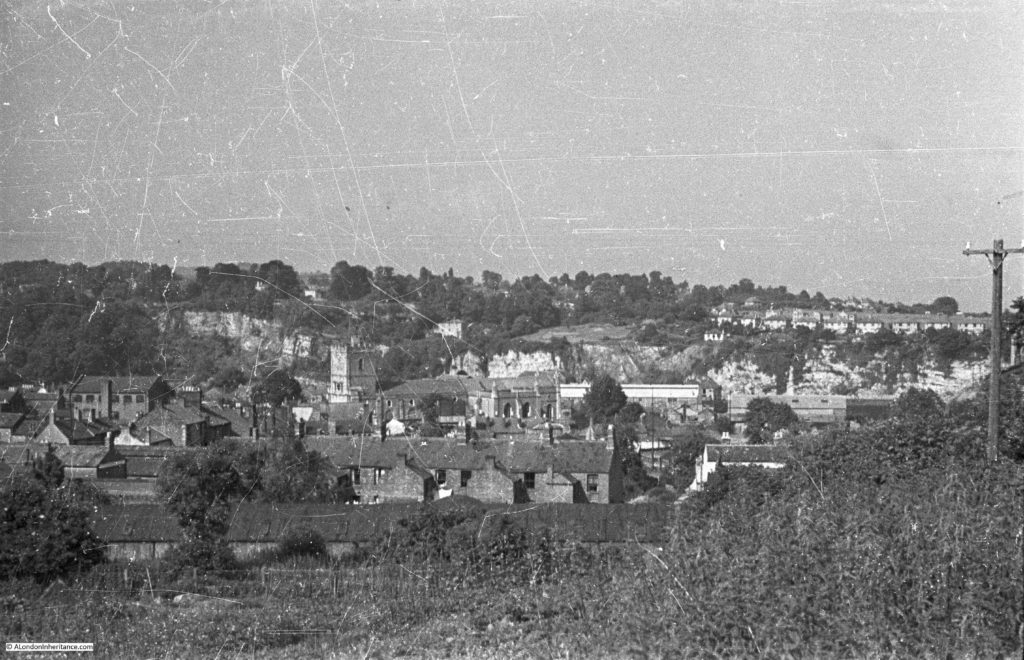

One trip in 1948 included a route through the county of Kent. I have already written about the visit to Canterbury, however they also passed through the small village of Biddenden, and this was the view of the village green on a summer’s day in 1948:

This was the same view in July 2021:

Although there is 73 years between the two photos, the area around the central village green of Biddenden still looks much the same. For a change, I even managed to take the “now” photo with similar weather to the original, although this was more through luck than clever planning.

The main difference is the number of cars parked, and the more organised road markings and boundaries.

The central green area has also lost the original iron railings, and the village name sign has also been moved back further into the green.

Biddenden is one of the many very picturesque villages in the Weald of Kent, the area of once forested land that stretched across the south of the county.

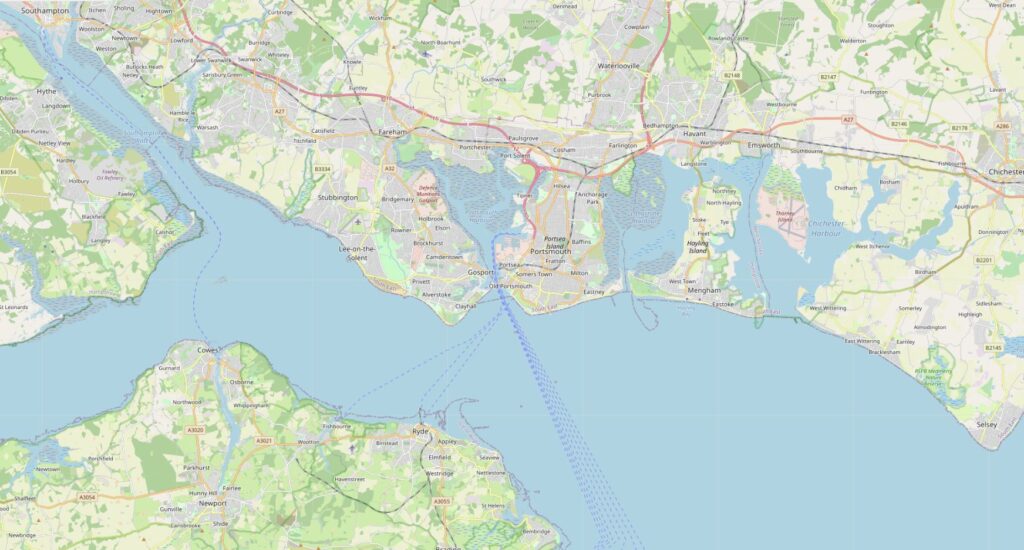

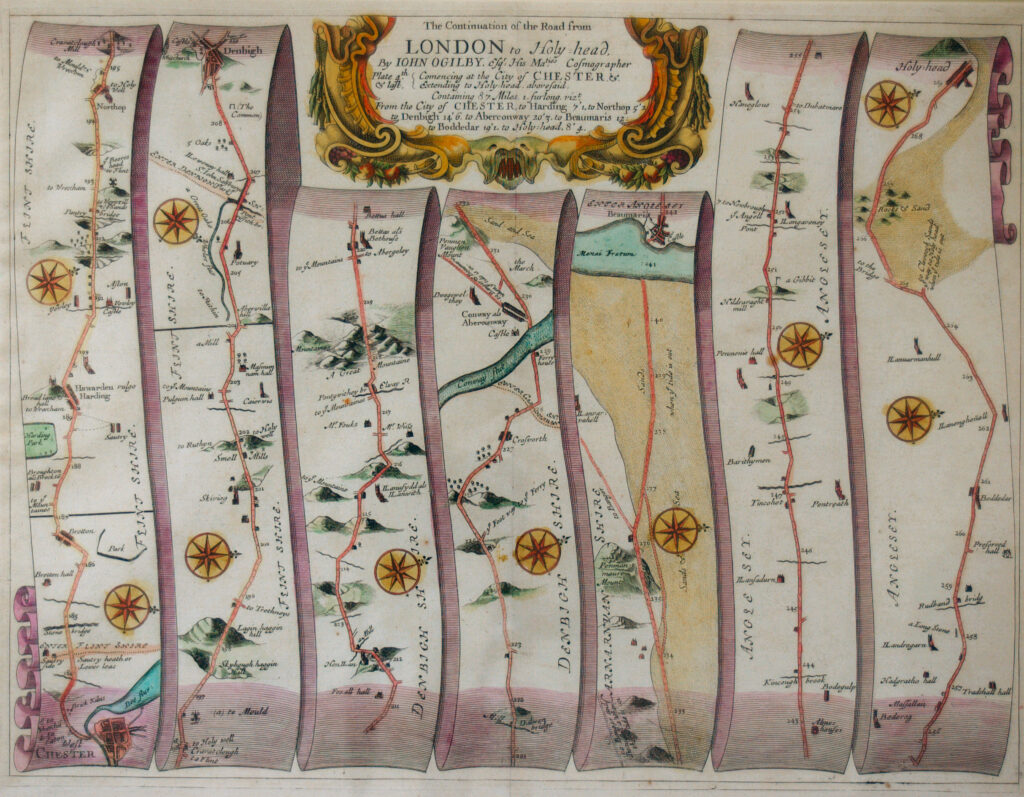

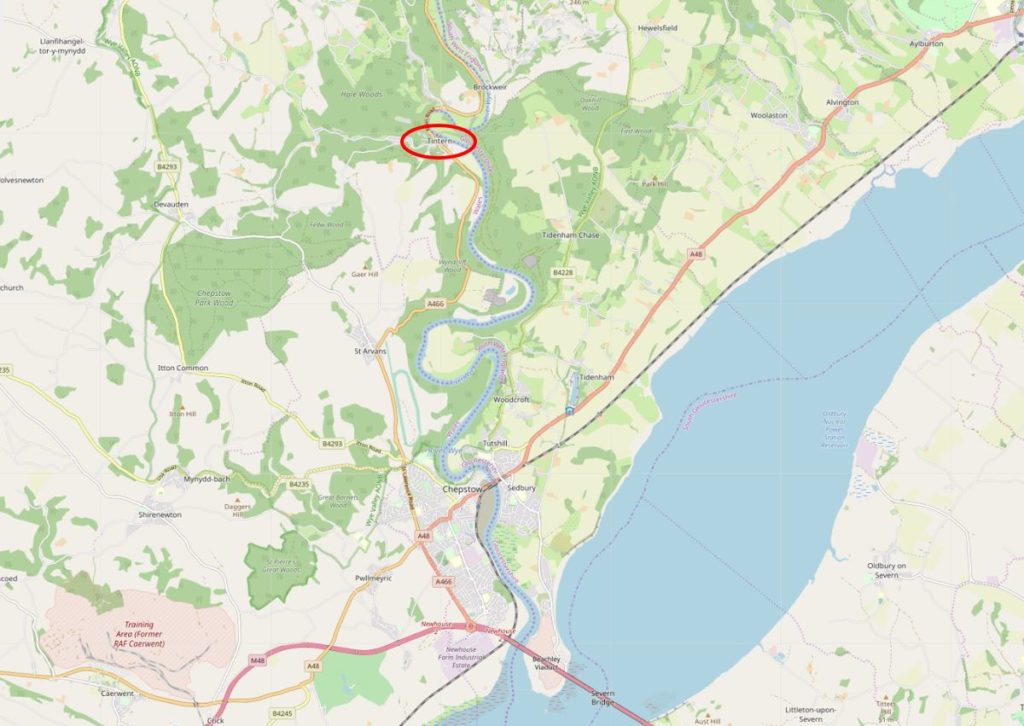

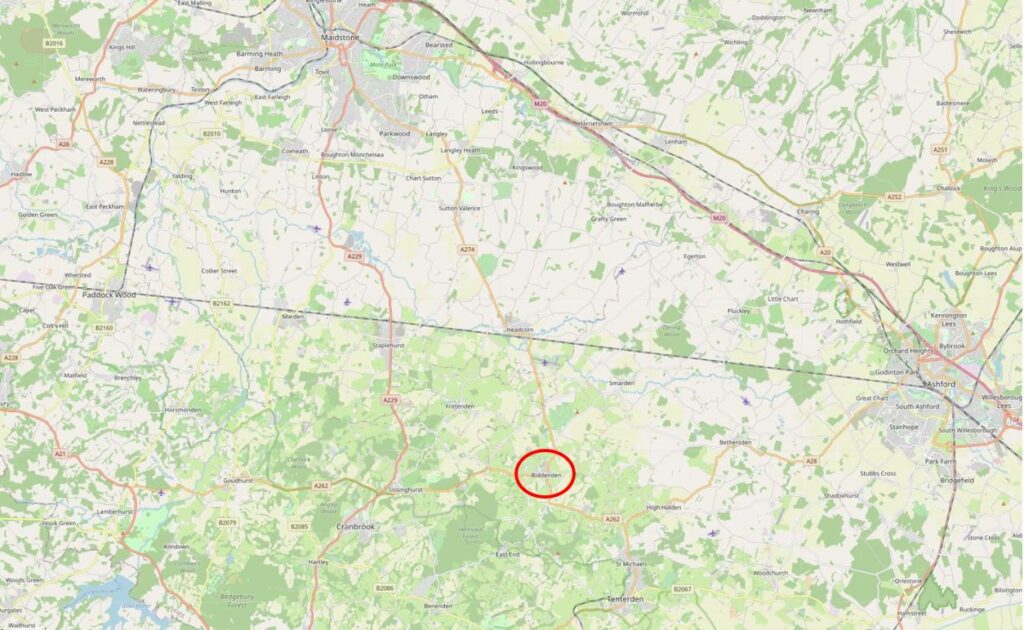

I have marked the location of Biddenden in the following map . The town of Ashford is the grey built area to the right of the map, with Maidstone to top left of the map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

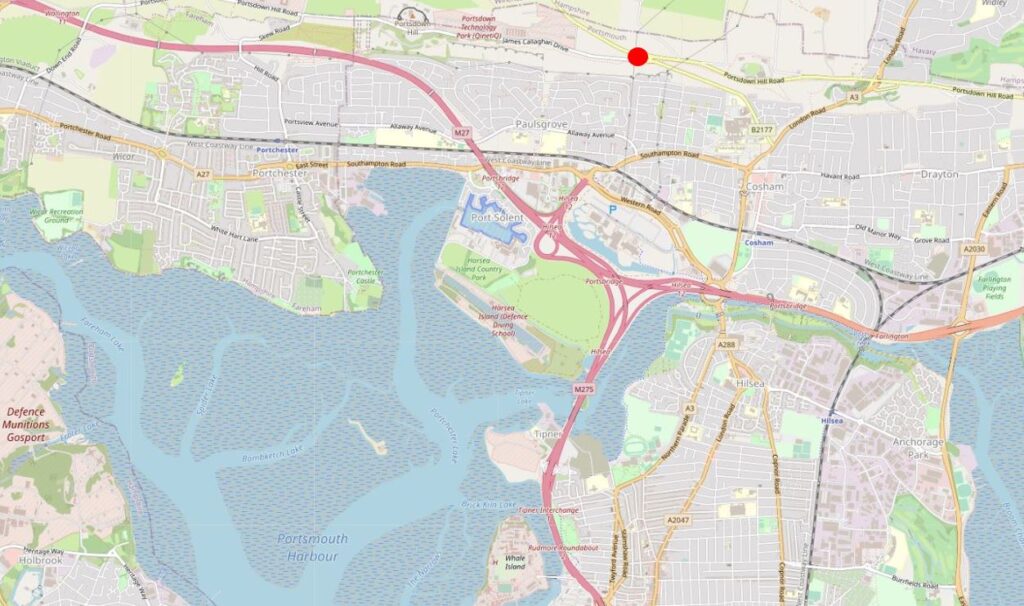

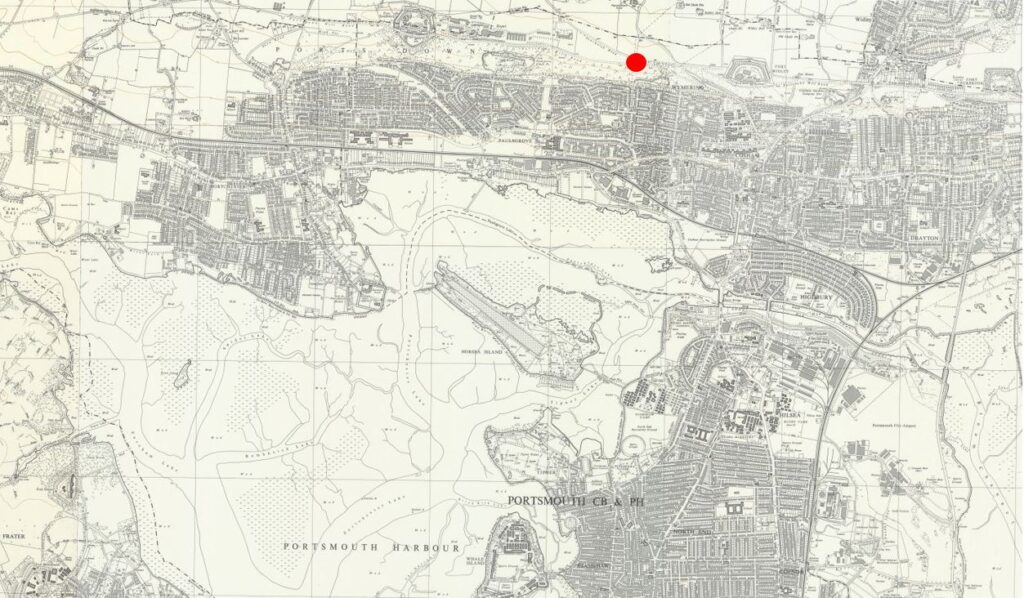

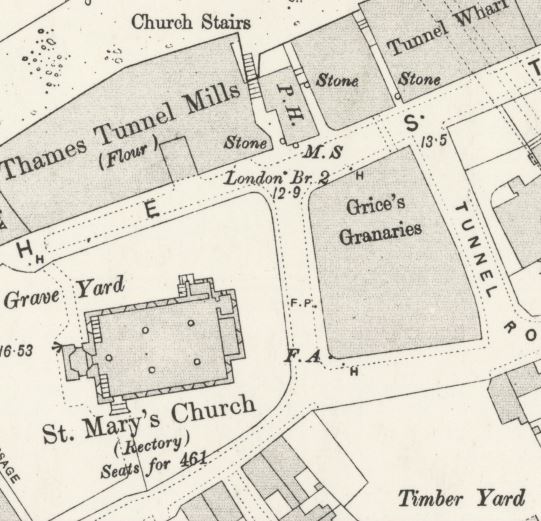

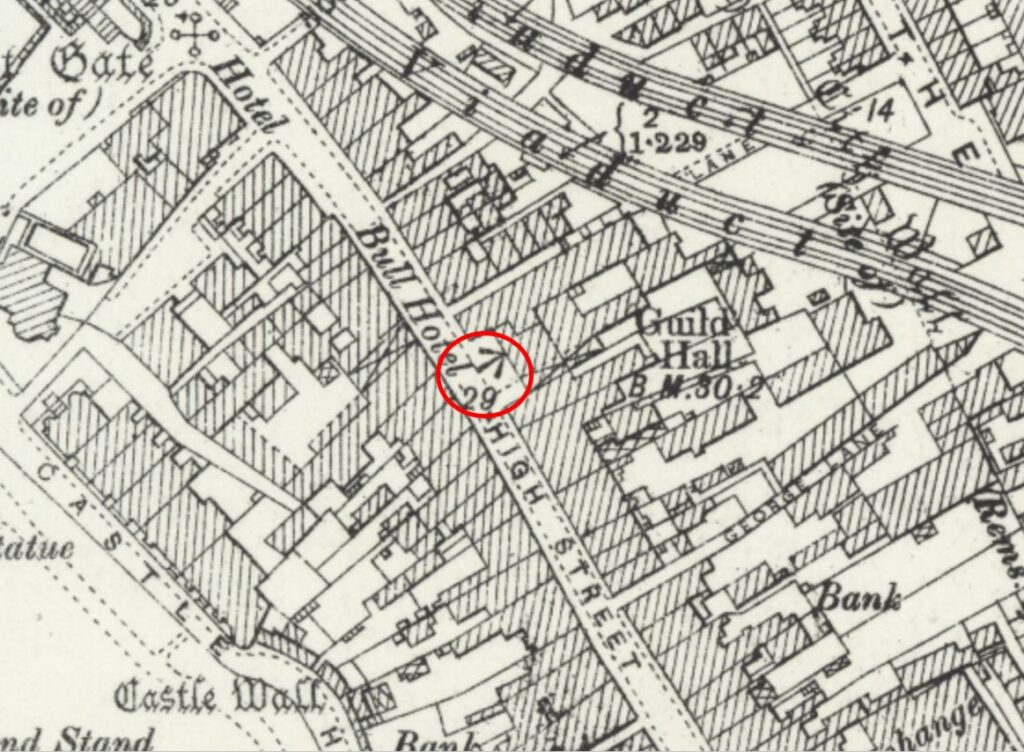

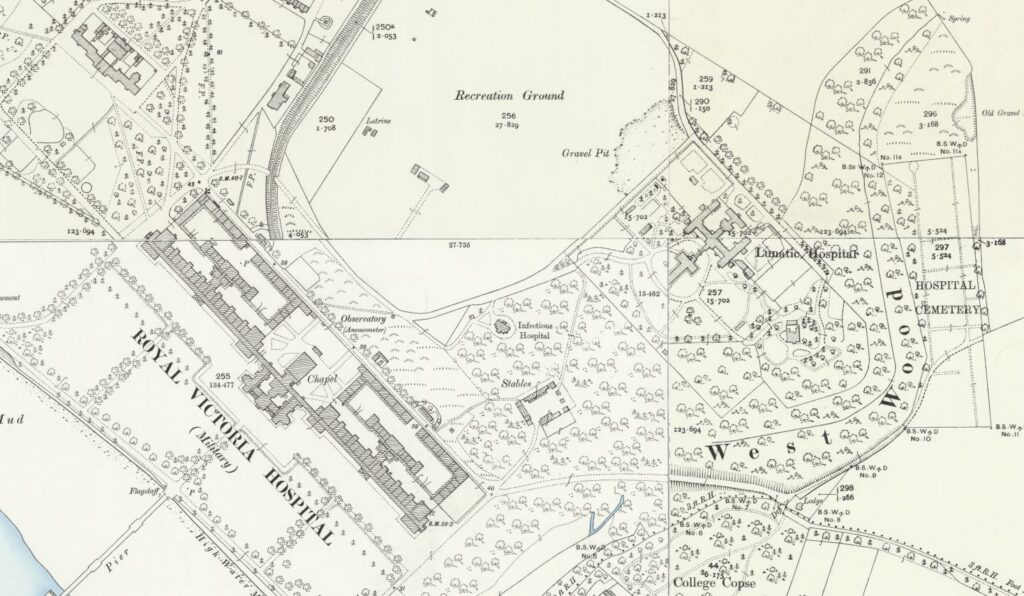

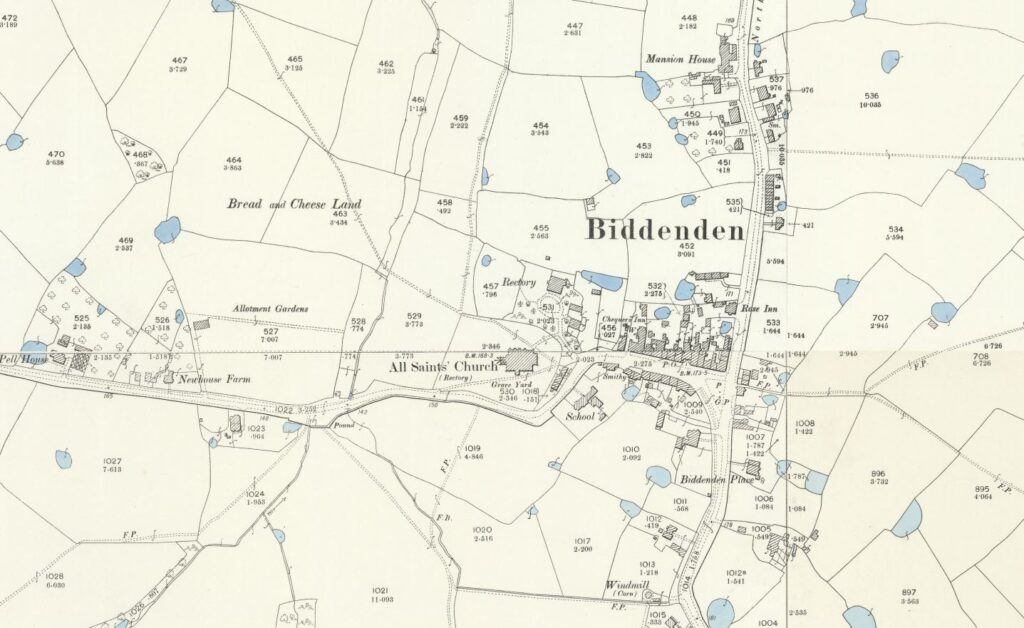

The Ordnance Survey map from around the time of my father’s visit shows a small village surrounded by fields (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

The village green in the above photos is located at the road junction to the right of the street with buildings lining both sides. There has been some development, mainly to the north of the village, and west of the church, however Biddenden is still very much a village surrounded by fields.

Many villages in this area of Kent have rather ornate name signs, which frequently include a historic fact about the village, however few illustrate a story as strange as that of Biddenden.

Looking closer at the name sign, it shows two women standing beside each other (1948 above and 2021 below):

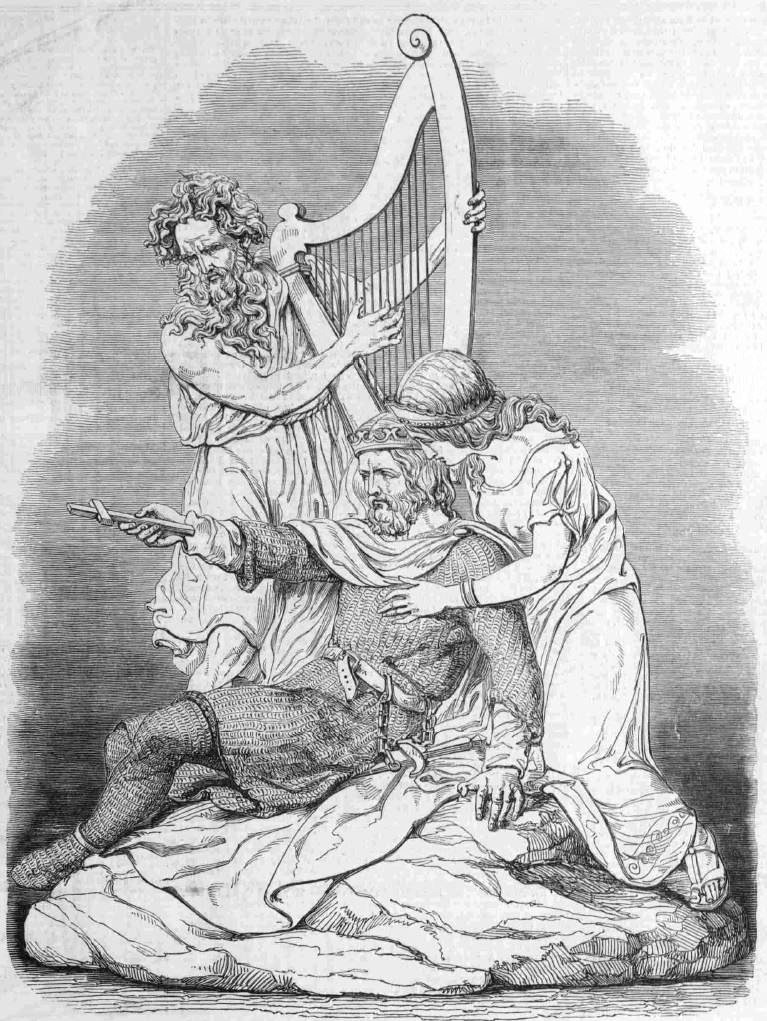

They are the so called Biddenden Maids, or the conjoined twins Eliza and Mary Culkhurst.

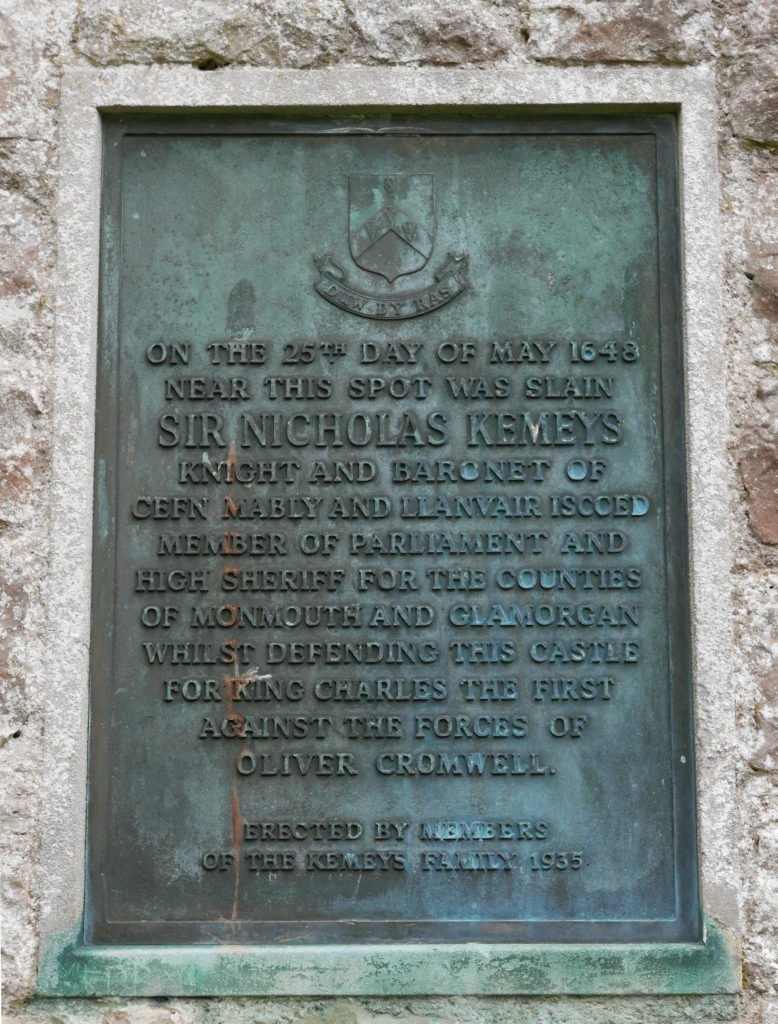

A newspaper article from the 15th May 1885 provides some background to the Biddenden Maids:

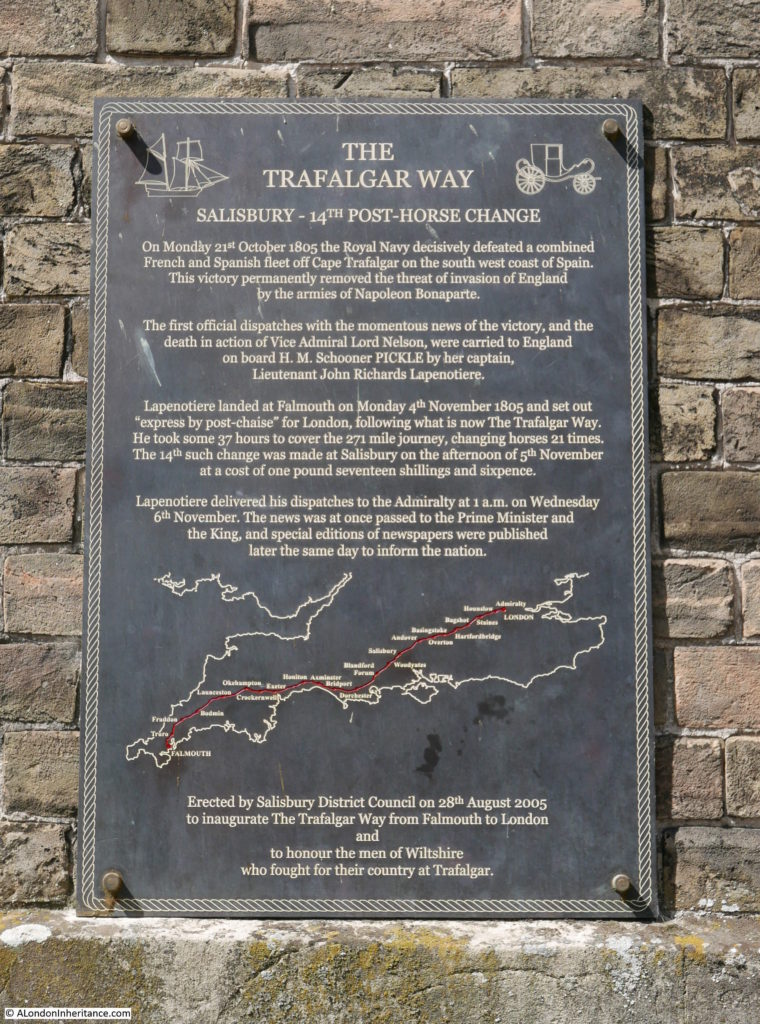

“Among the various charities in the parish of Biddenden, in Kent, is one which has acquired some celebrity. On the afternoon of Easter Sunday a quantity of small flat cakes, made only of flour and water and impressed with the figures of two women, united at the sides after the fashion of conjoined twins, are distributed in the church porch to all comers. Bread and cheese, to a considerable amount, are given at the same time to the poorer parishioners. This, says tradition, was the legacy of the twin sisters, called the Biddenden Maids, who lived for many years united in their bodies after the manner represented in the cakes, and then died within a few hours of each other. There is also given to the recipients of the cakes a printed paper bearing upon it a representation of the impression on the cakes, and purporting to contain ‘a short and concise account of the lives of Elisa and Mary Culkhurst, who were born joined by the hips and shoulders, in the year of our Lord 1100, and in the county of Kent, commonly called the ‘Biddenden Maids’ .

It then proceeds- ‘The reader will observe by the plate of them that they lived together in the above state thirty-four years, at the expiration of which time one of them was taken ill and in a short time died. The surviving one was advised to be separated from the body of her deceased sister by dissection, but she absolutely refused the separation by saying these words ‘As we came together we will also go together’ and in the space of about six hours after her sister’s decease she was taken ill and died also.

By their will they bequeathed to the churchwarden of the parish of Biddenden, and his successors, churchwardens, for ever, certain pieces or parcels of land in the parish of Biddenden, containing twenty acres, more or less, which now let at 40 guineas per annum.

There is usually made in commemoration of these wonderful phenomena of nature about 1000 rolls, with their impressions printed on them, and given away to all strangers on Easter Sunday after Divine service in the afternoon; also about 500 quartern loves and cheese in proportion, to all the poor inhabitants of the said parish”.

At a distance of 900 years, it is hard to know the truth of this story.

Edward Hasted, writing in the “The History and Topographical Survey of the County of Kent” referenced the story as follows:

“There is a vulgar tradition in these parts, that the figures on the cakes represent the donors of this gift, being two women, twins, who were joined together in their bodies, and lived together so till they were between twenty and thirty years of age. But this seems without foundation. The truth seems to be, that it was the gift of two maidens, of the name of Preston; and that the print of the women on the cakes has taken place only within these fifty years, and was made to represent two poor widows, as the general objects of a charitable benefaction.”

Hasted did not seem convinced about the original story of the Biddenden Maids, however he does not give any further details or sources for his suggestion as to the truth of the story.

The money for the cakes and loaves came from the rents received from twenty acres of land known as Bread and Cheese land. If you look back at the Ordnance Survey map of Biddenden earlier in the post, two large fields to the upper left of the village were still called Bread and Cheese Land.

The first newspaper reference I can find to the Biddenden Maids is an article in the London Evening Standard in 1829. There are then numerous articles, mainly reporting on the Easter Sunday charity distribution, and the large number of visitors to the village who came to see and participate in the distribution of the cakes.

Popularising the Biddenden Maids would have helped the economy of the village.

According to Biddenden’s web site, the charity distribution still takes place:

“Once a year Bread and Cheese are given to local widows and pensioners at the Old Workhouse. Biddenden Biscuits, baked from flour and water, are distributed among the spectators as souvenirs. They bear an effigy of two female figures whose bodies are joined together at the hips and shoulders.”

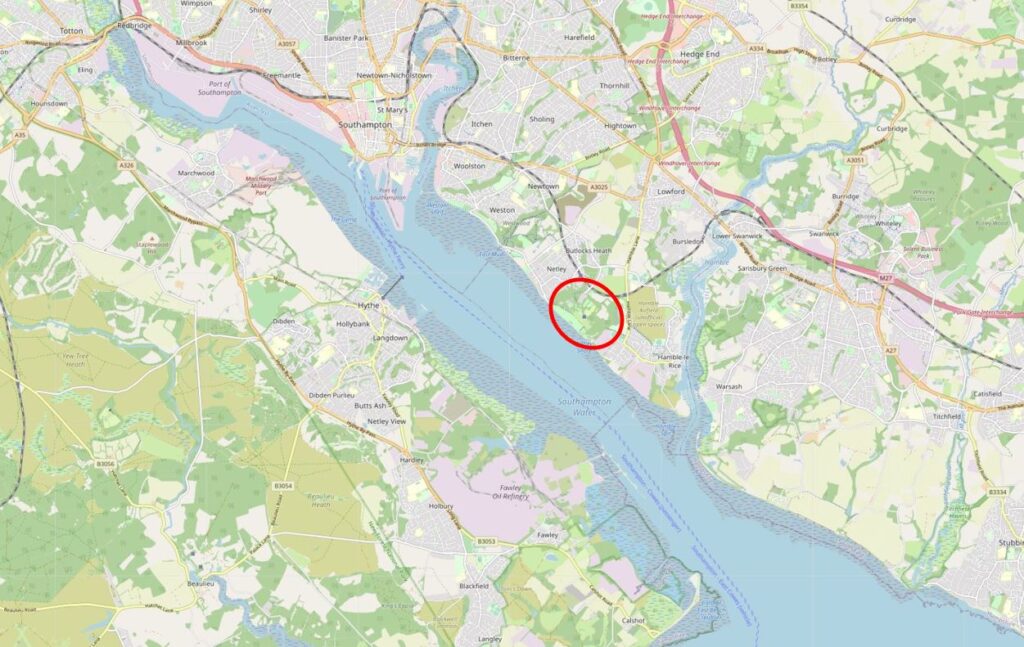

A close up of the village sign in 1948:

In 1948, the wording between the two women was “IN KENT” – a continuation of the village name above to show the county of the village, however by 2021, the names of the two women, Mary and Eliza had replaced the county name.

The origin of the sign dates back one hundred years. In 1920, the King discussed the revival of village signs during a speech at the Royal Academy.

The Daily Mail then organised a village signs competition and exhibition with a fund of £2,200 being available in prizes. Of the ten awards made, the design for the sign at Biddenden received a special prize of £50.

There are a number of subtle differences between the signs of 1948 and 2021. This is probably down to the complete refurbishment of the sign in 1993.

This may have included the changes, such as, moving the sign back further into the green. replacing the county of Kent, with the names of the twins, and replacing the pole as the original square pole is now round, with some gold spiral decoration.

The photos of the village in 1948 and 2019 tell a story of how villages change, and stay the same. If you go back to the 1948 photo at the top of the post, there is a sign on the very first building on the left. The sign is for a bank, and looking at the high resolution scan from the scanner it seems to be a Lloyds Bank. Remarkable at a time when bank branches are disappearing by the day that in 1948 a small village of the size of Biddenden would have their own bank branch.

The building that was once the bank is shown in the photo below:

Not visible in the 1948 photo, but there is a terrace of rather special houses continuing on from the bank. These were Flemish Weavers cottages, dating from the 17th century:

Directly opposite the above terrace, there is a pub and café:

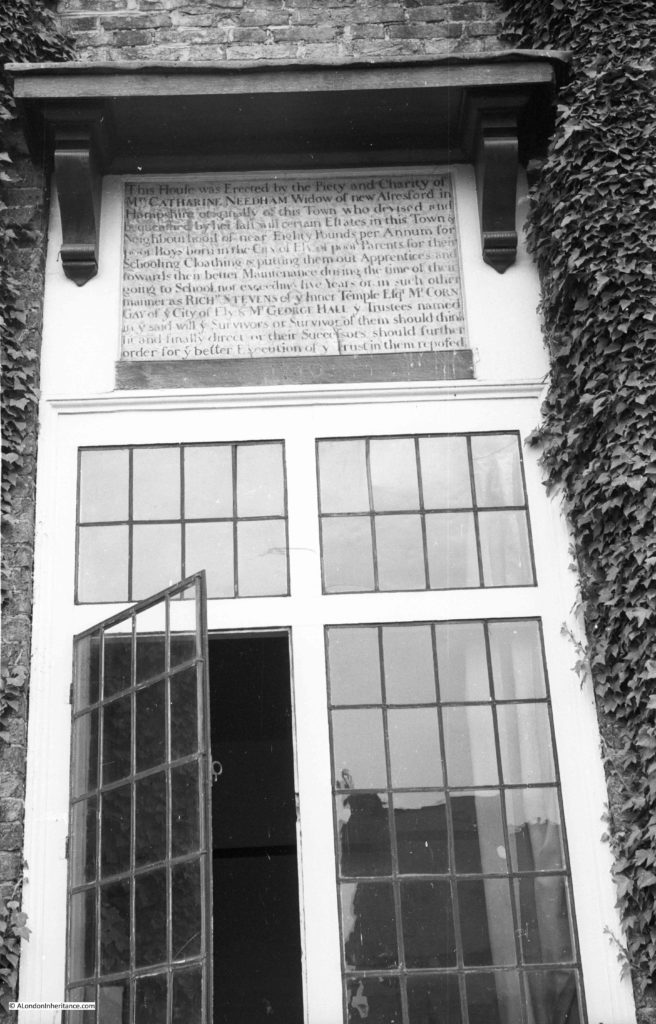

As we had travelled by car, the pub was out of bounds (Biddenden did have a railway station, however this branch of the Kent and East Sussex Railway closed in 1954), so we went into the Bakehouse Café, which was excellent, and which had the following inscription on one of the windows overlooking the street:

The main street through Biddenden village:

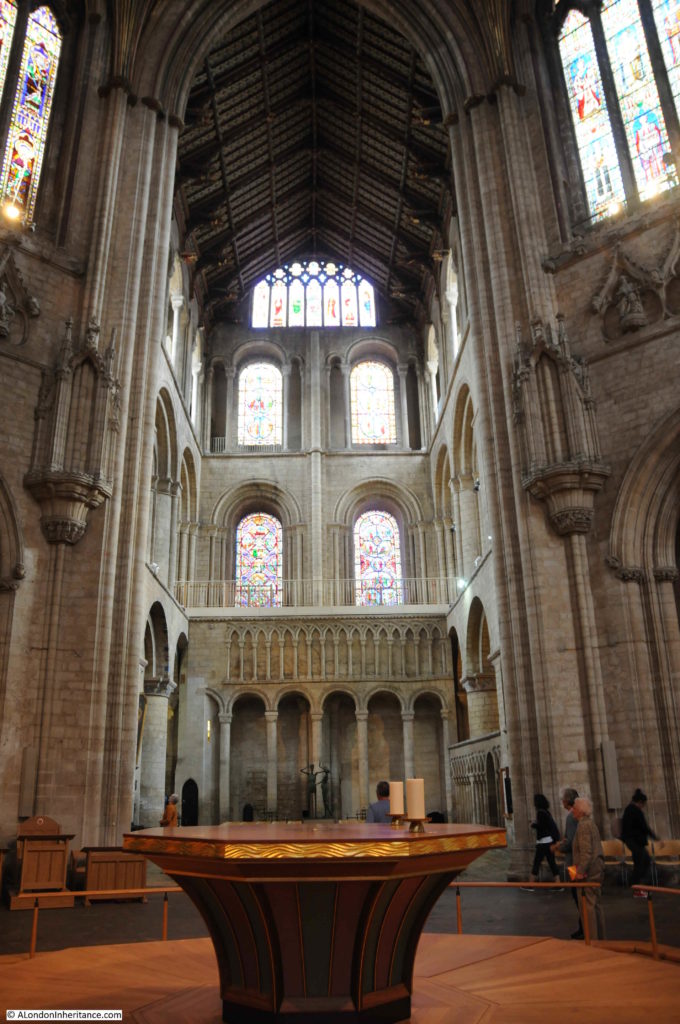

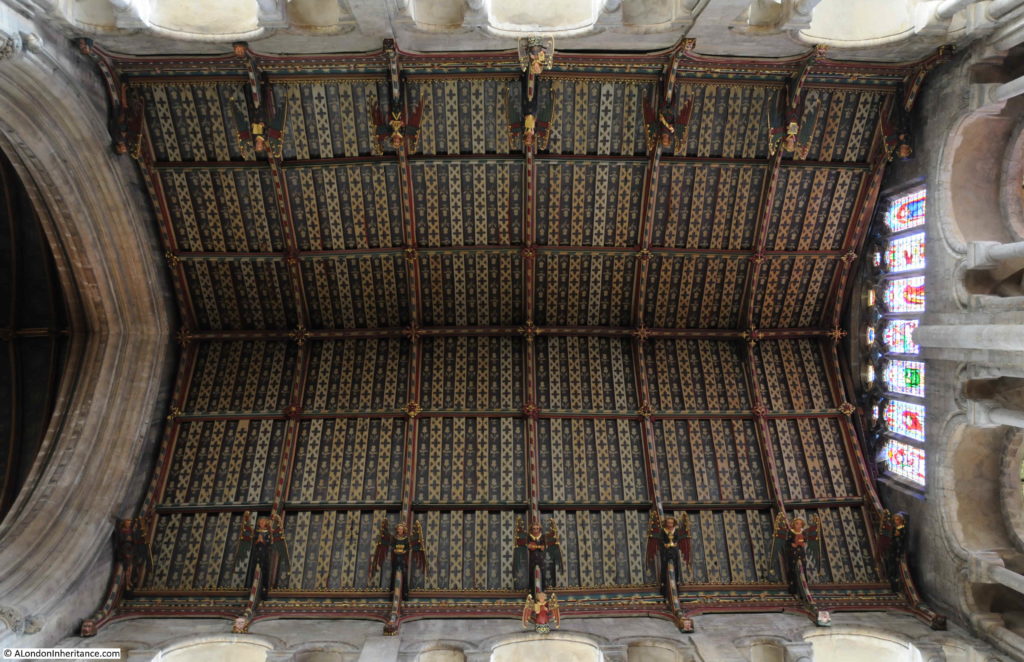

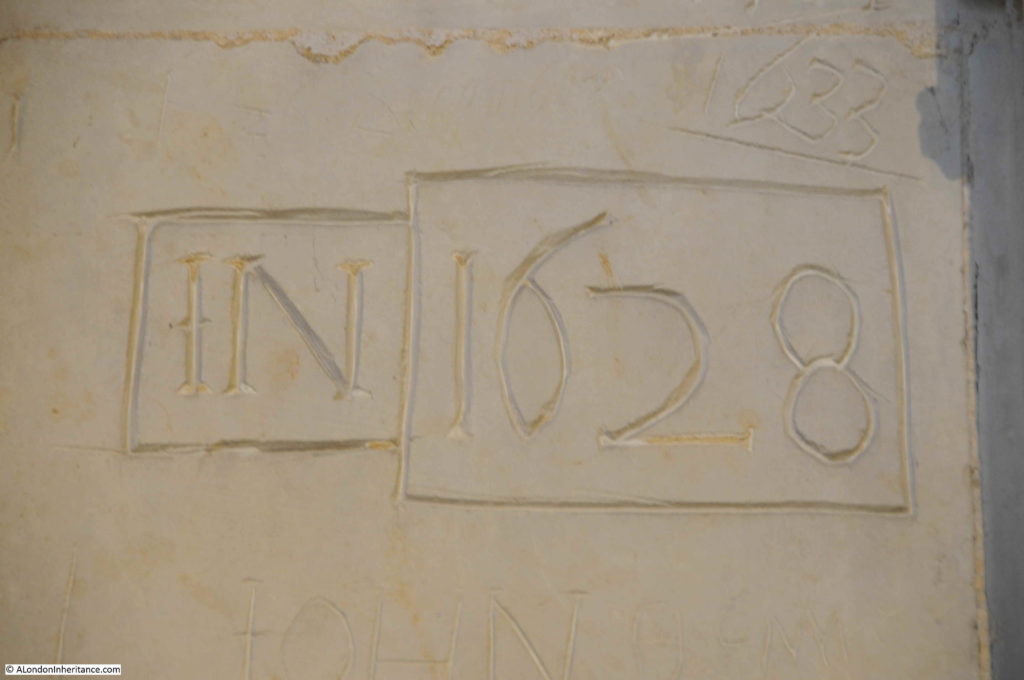

Behind me, in the above photo is the entrance to Biddenden’s church which stands at the western end of the village:

Parts of the church date from the 13th century, however there has been much later rebuilding. Unfortunately it was locked on the day of our visit so no opportunity to take a look inside.

At a distance of 900 years, it is almost impossible to be sure of the origins of the story of the Biddenden Maids, however the story is still central to the village, and it has been the driving force behind a charity distribution which has taken place for hundreds of years, and in a world where places get more and more standardised and similar, it is good for a place to retain its own unique identity.

For next Sunday, I will be back in London.

Southbank Walks

A couple of tickets have become free on two of my Southbank walks. If you are interested in exploring the history of the Southbank and the Festival of Britain, there is:

All other walks have sold out.