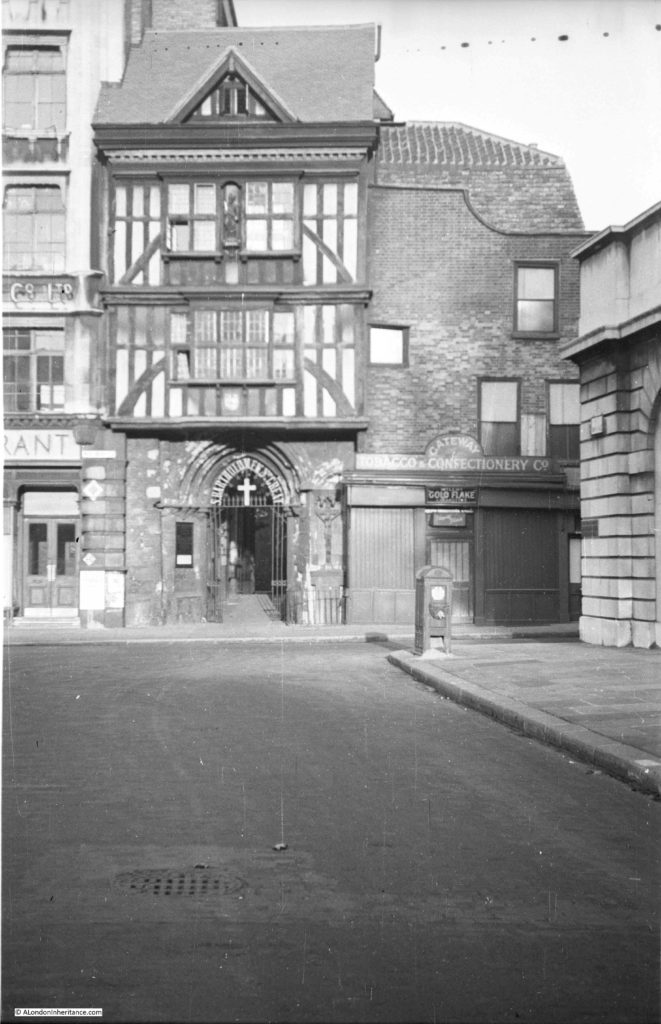

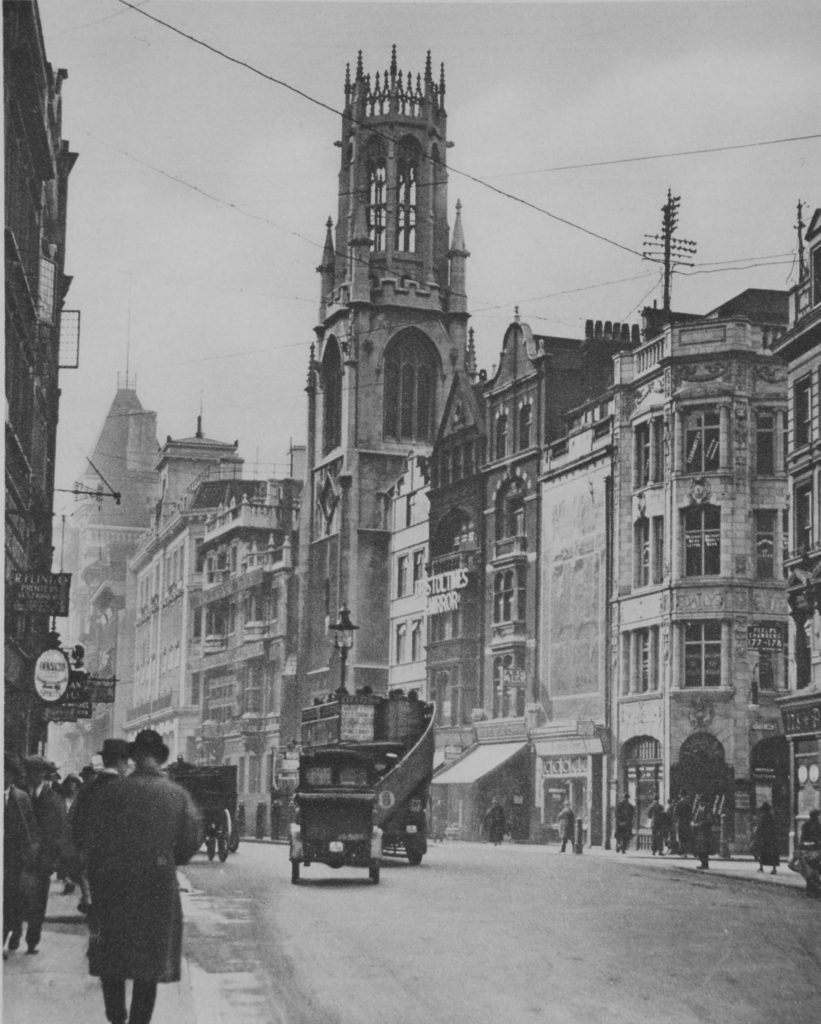

I did not immediately recognise the location of this week’s post. I knew it was in the City of London, but I could not place the curve of the street or the church tower. It was finally the buildings on the right and the church tower that resulted in me standing in Gresham Street, by the junction with Foster Lane.

And this is the same view on a late autumn afternoon in 2017:

The two photos help illustrate the many subtle changes that have taken place in the City, and what buildings did, and did not survive post war reconstruction.

The building that initially helped me to identify the location is the large building on the right of both photos. This is the hall of the Goldsmiths’ Company. The building is the third Goldsmiths’ Hall on the same site. The Goldsmiths’ Company moved to this location in 1339 and the current hall dates from 1835. The hall avoided the complete wartime destruction of many of the surrounding buildings, however the south west corner of the building was damaged by a direct hit.

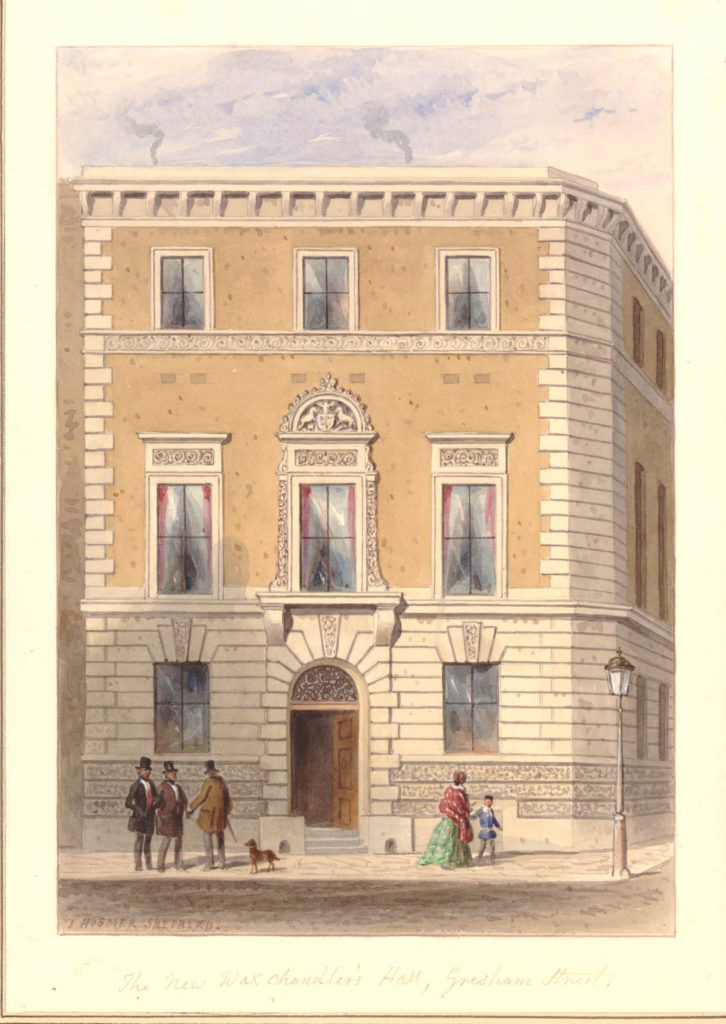

The building next to Goldsmiths’ Hall is the Wax Chandlers Hall. As can be seen this was completely destroyed during the war apart from the granite ground floor outer walls. Rebuilding of the hall was completed in 1958 with the granite frontage being retained and brick used for the new upper floors. As with the Goldsmiths’ Hall, this is a historic location for the Wax Chandlers as they have occupied the site since 1501.

The church tower is that of St. Lawrence Jewry. The church was almost completely destroyed in December 1940, apart from the tower and the outer walls. The church had lost its steeple, which is one of the reasons I did not immediately identify the church.

Gresham Street has also undergone some subtle changes. Today, standing outside Goldsmiths’ Hall we can look directly down to St. Lawrence Jewry. This was not the case when my father took the original photo as there were some curves in the street and a building in front of the church tower.

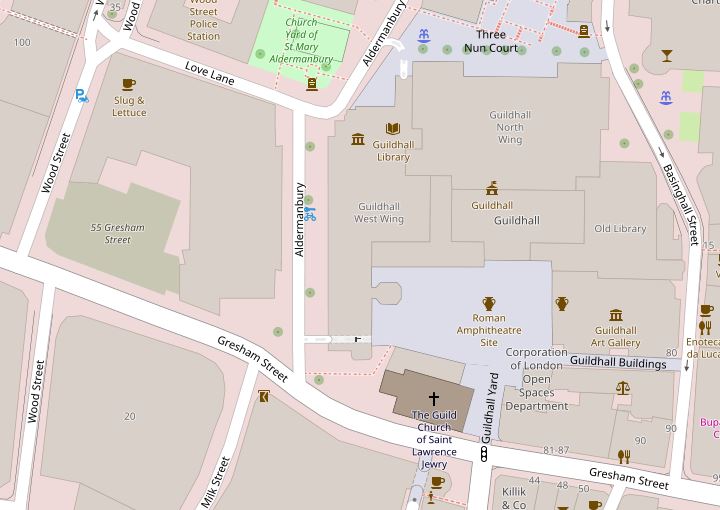

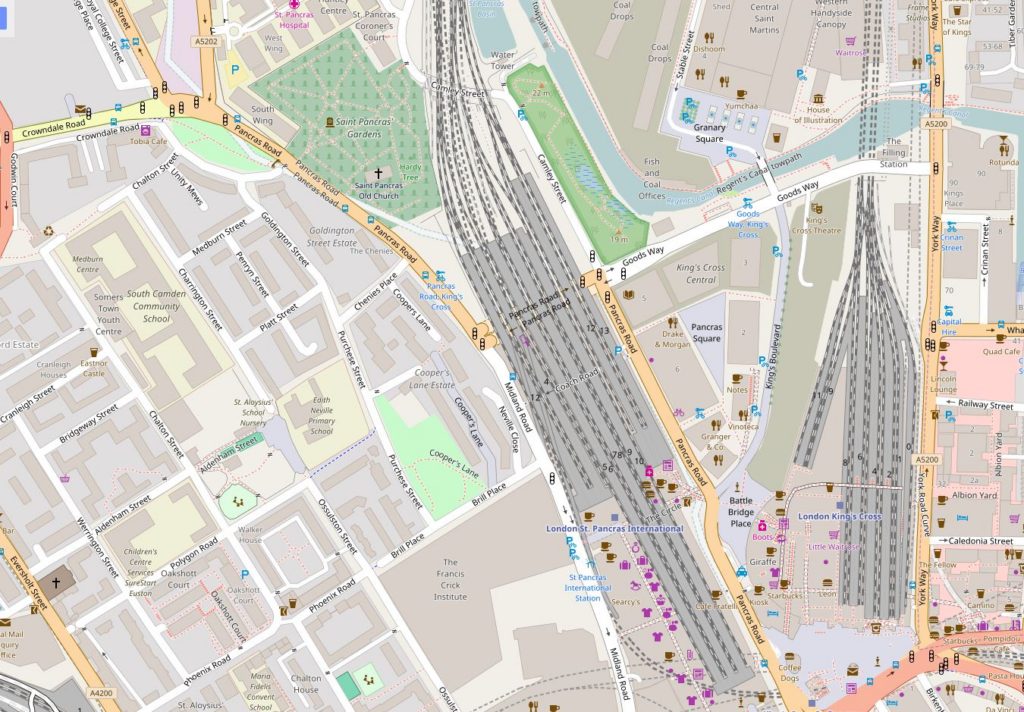

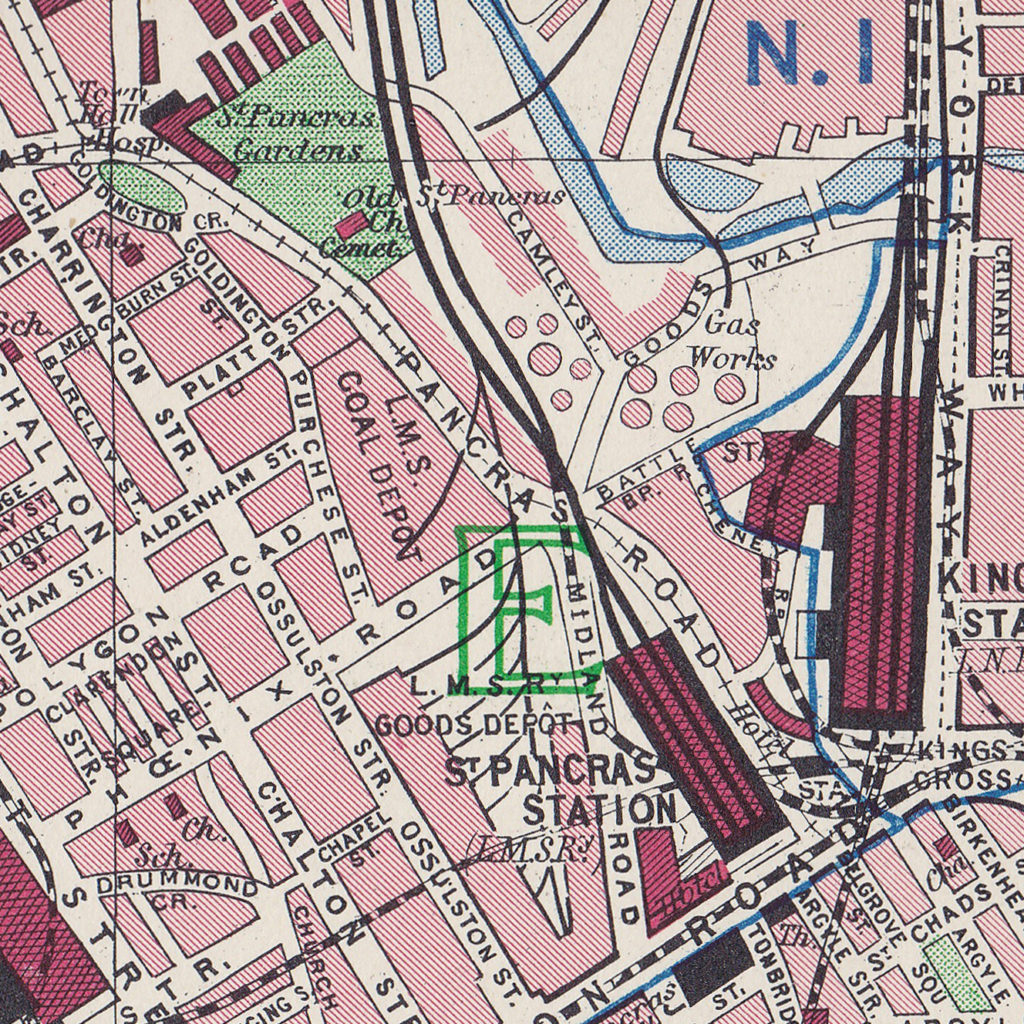

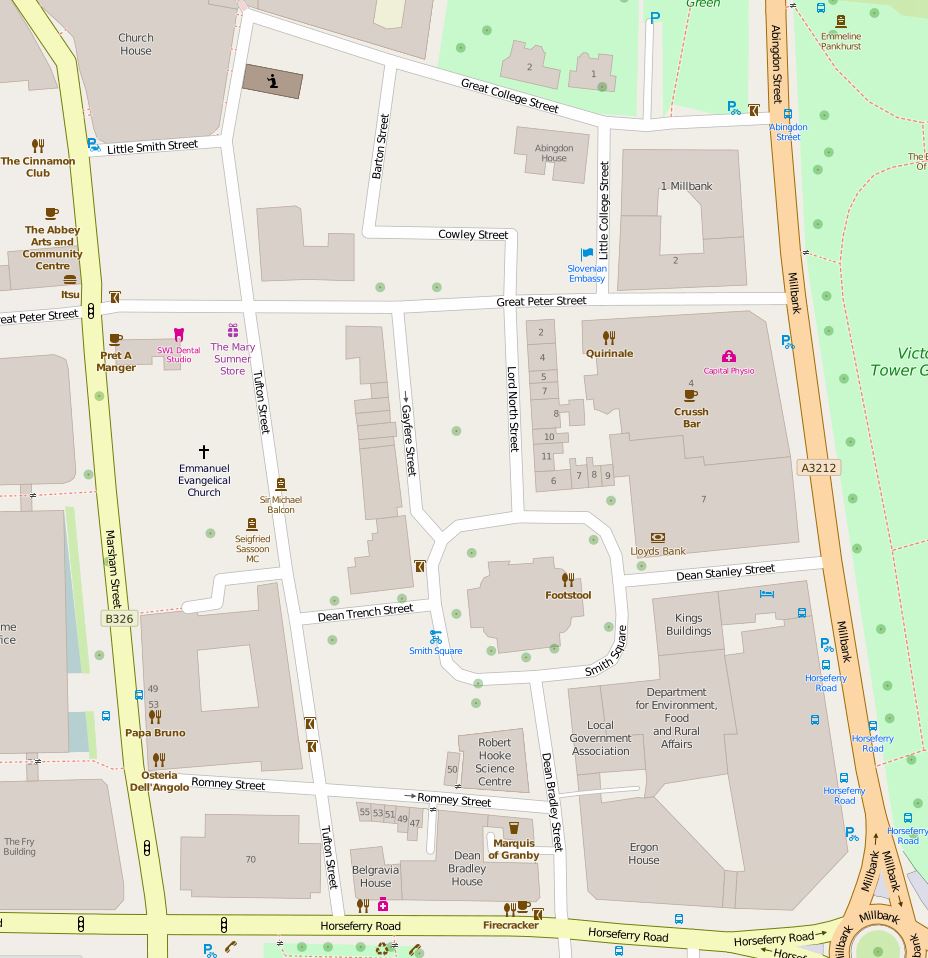

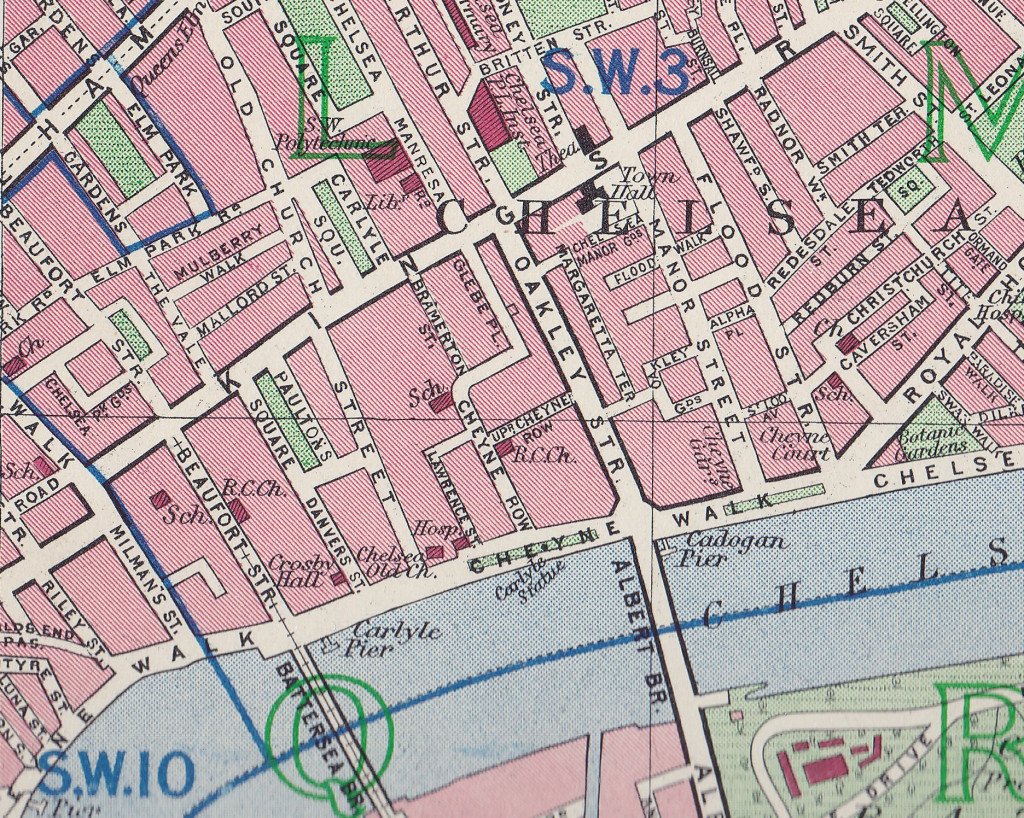

Gresham Street has been through post war widening and straightening. The following map shows the area today. There is only a slight curve in the street by the junction with Aldermanbury.

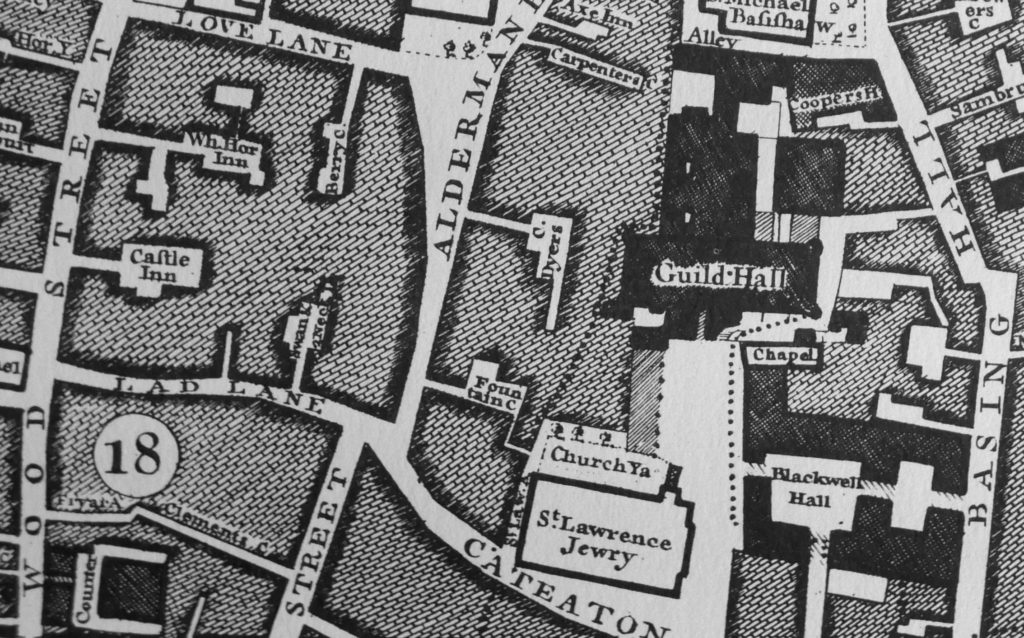

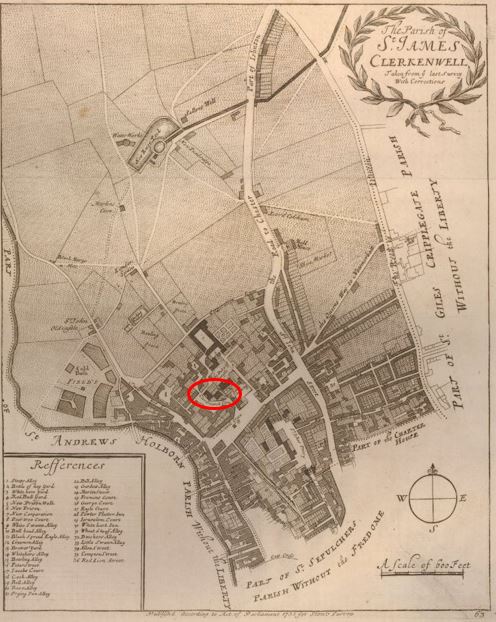

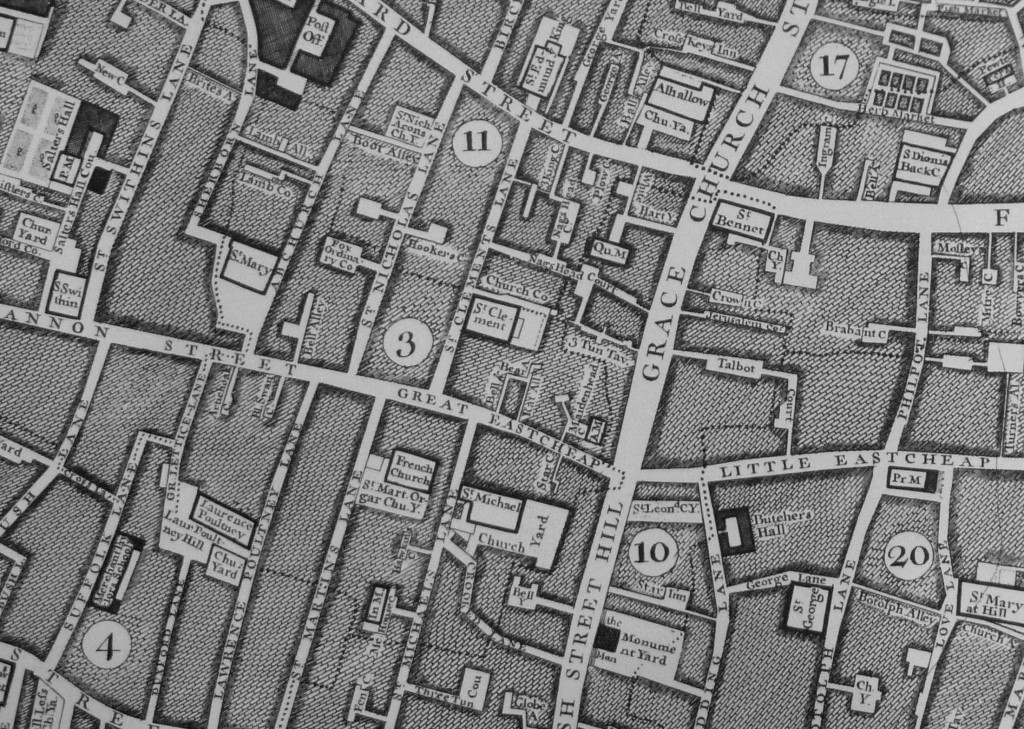

If we go back and look at John Rocque’s map of 1746 we can see that the street had a more pronounced curve at the junction with Aldermanybury and it is here that post war straightening has slightly changed the street. Gresham Street also had different names.

During the 19th century, many of the City’s streets were widened, straightened and what were smaller individual streets were joined into single, longer streets.

Gresham Street was one of these, created in 1845 from Cateaton Street and Lad Lane. The new street was named after Sir Thomas Gresham who was the founder of the Royal Exchange and Gresham College, which started in Bishopsgate Street in 1597 before moving to Gresham Street in 1843 – it has been at Barnard’s Inn Hall near Chancery Lane since 1991.

It is interesting that the street alignment and the buildings blocking the front of St. Lawrence Jewry were much the same in my father’s post war photo as they were in 1746.

This is the full view of Goldsmiths’ Hall on Gresham Street. The main entrance is along Foster Lane. This is the only building to survive intact from before the last war along this stretch of Gresham Street up to the church of St. Lawrence Jewry,

The front of the Wax Chandlers Hall is in the photo below. The granite frontage is the only part that survives from the original pre-war building. The hall dated from the 1845 creation of Gresham Street as the earlier hall occupied land to the north of the existing hall, which was used in the extension of Gresham Street.

The following print from 1855 shows the Wax Chandlers hall in 1855, not long after it was built. The ground floor is the same as in the building today, however the upper floors are very different as a result of the post war rebuild of the bombed building.

Walking down Gresham Street I came up to the church of St. Lawrence Jewry, the church tower in the distance in my father’s photo.

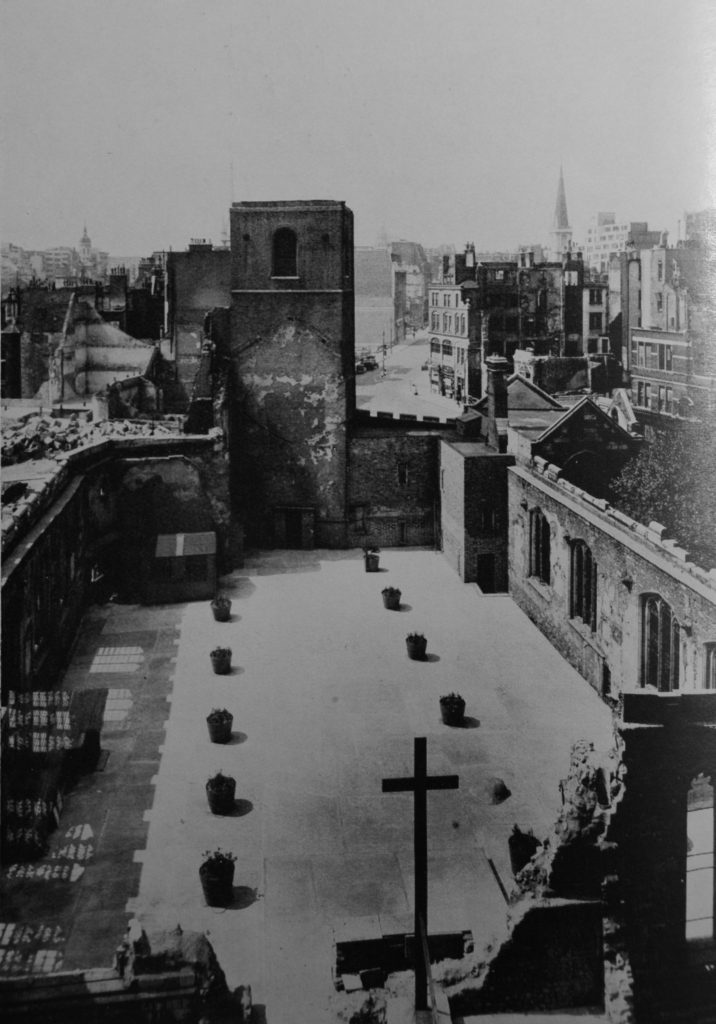

In the original photo, the church had lost the spire on top of the tower, indeed only the tower and surrounding walls had survived the bombing and resulting fires.

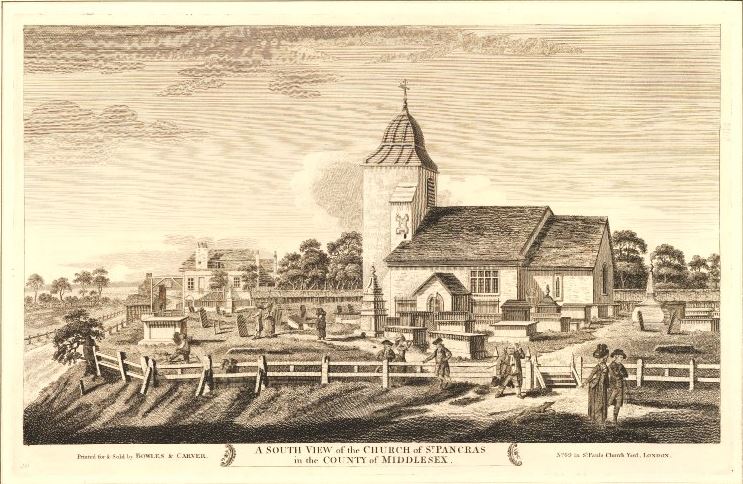

The first church on the site was around the 12th century. The dedication is to St. Lawrence, a 3rd century martyr who was burnt to death on a gridiron in Rome. The reference to Jewry is that the church was originally in the part of the City occupied by the Jewish community.

The symbol of the gridiron on which St. Lawrence was killed is used on the weather vane of St. Lawrence Jewry:

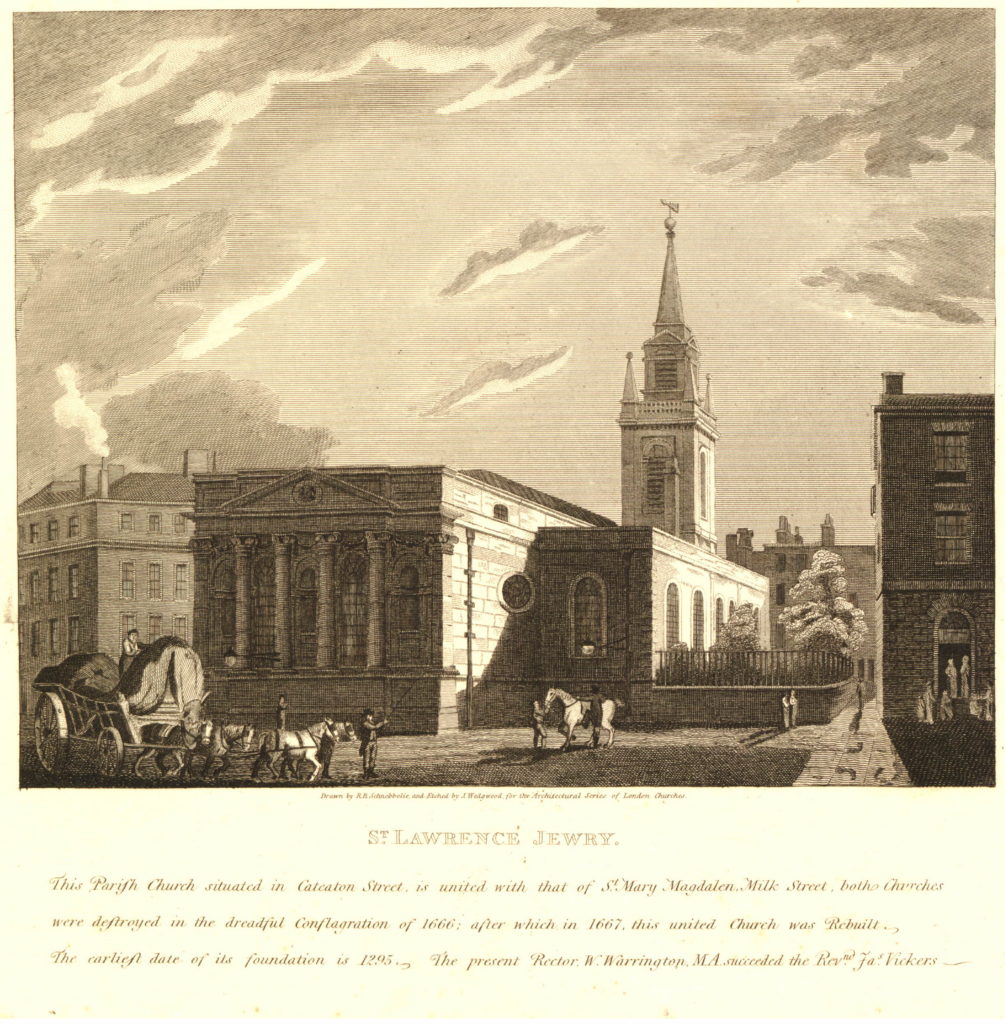

The church was one of many destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 and a new church was built by Wren in 1671 to 1677. The new church cost £11,870 and was the most expensive of the City churches built after the Great Fire.

The church was one of many destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666 and a new church was built by Wren in 1671 to 1677. The new church cost £11,870 and was the most expensive of the City churches built after the Great Fire.

The rear of the church from the junction of Gresham Street and King Street:

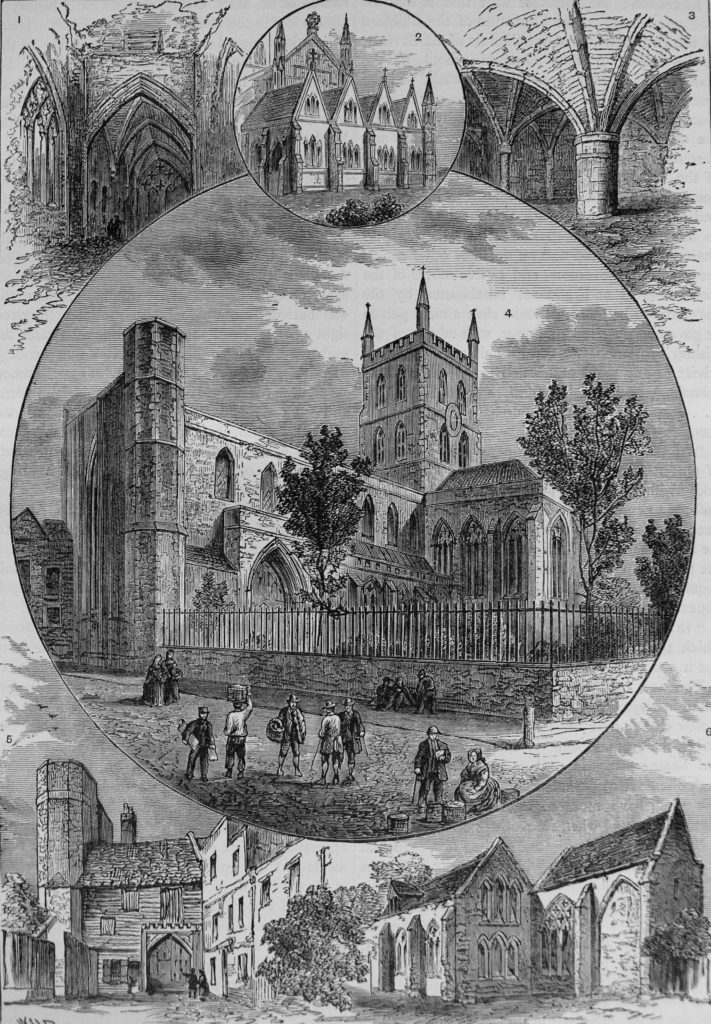

This 18th century view of the church from King Street shows that the post war rebuild of the exterior was faithful to Wren’s original design:

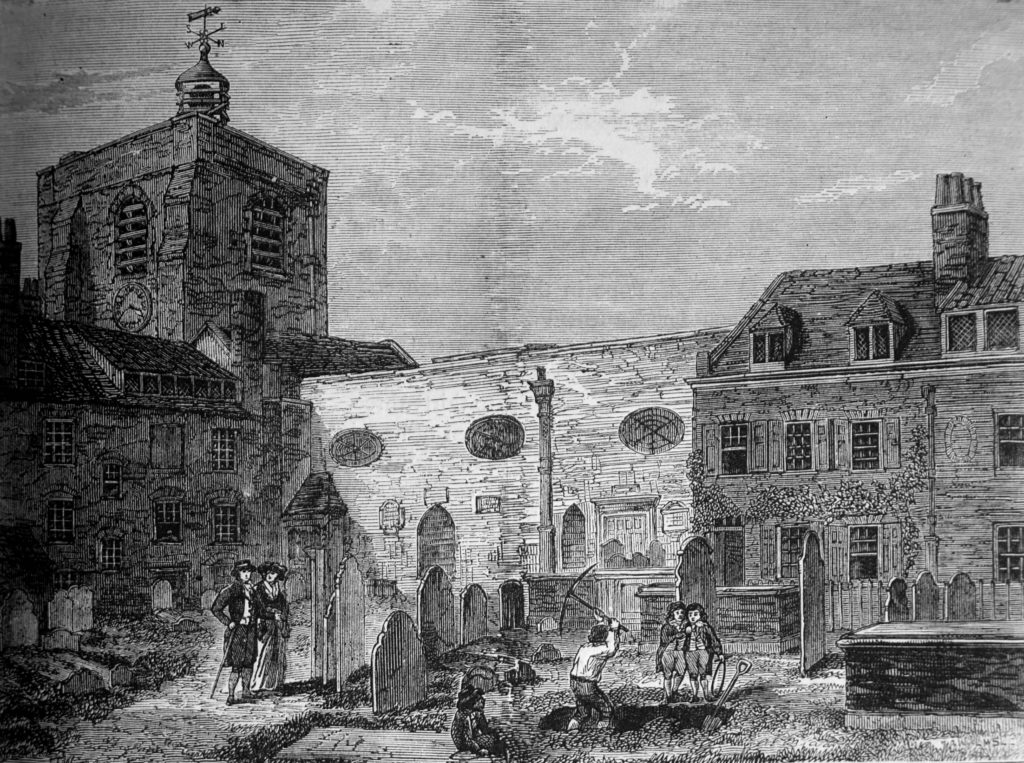

This print from 1811 is interesting, it includes the small church yard in what is now the large open space in front of the Guildhall, and the text also mentions the church being in Cateaton Street.

The interior of the church:

Looking towards the organ at the rear of the church:

The roof:

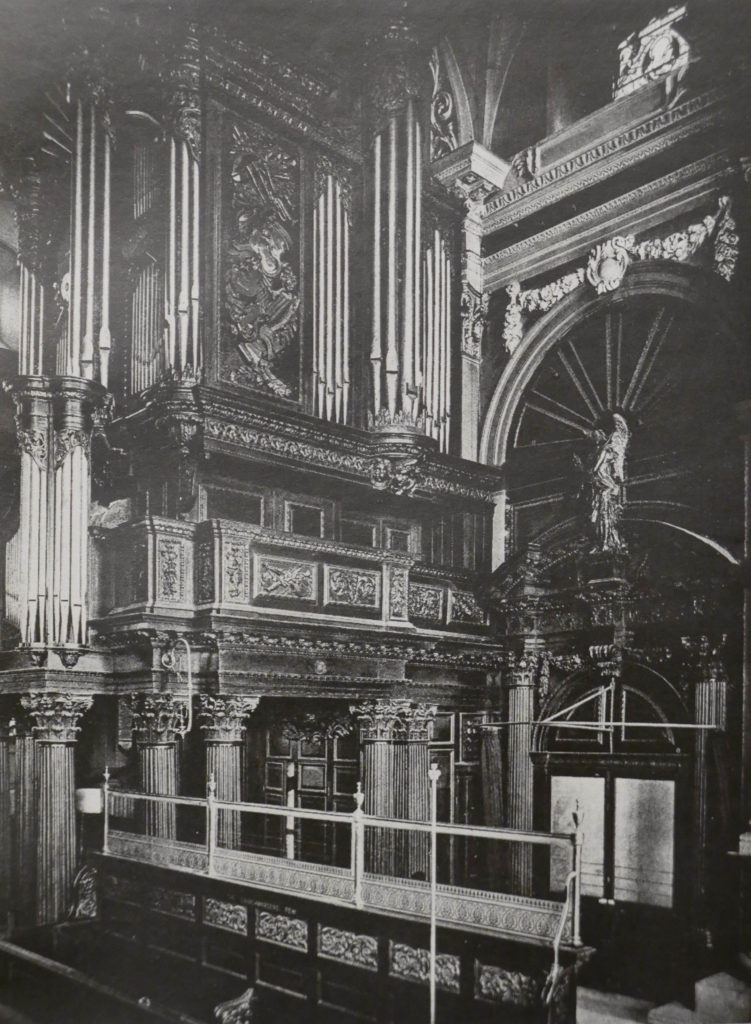

The interior of the church today is very different from the pre-war church. City churches tended to be very ornate with lots of wood panelling. The following print shows the organ case of the pre-war St. Lawrence Jewry:

This is the vestry of the pre-war St. Lawrence Jewry – the ceiling was painted by Isaac Fuller II and carved plaster and dark wood paneling produced a very ornate room:

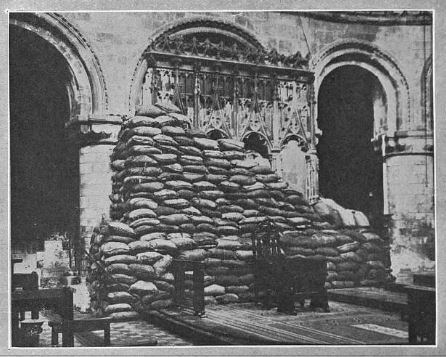

As mentioned earlier, the interior of the church was completely destroyed by the fires caused by incendiary bombs during the raids on the 29th December 1940.

My father’s photo only shows the tower from a distance with the loss of the spire being the only visible damage, however the following photo shows the interior of the church – open to the sky, the interior completely destroyed and a single monument surviving on the wall.

Within the church is a small display showing some of the artifacts rescued from the bombed church. This includes the cups shown in the photo below to show the damage that was caused by the intensity of the heat.

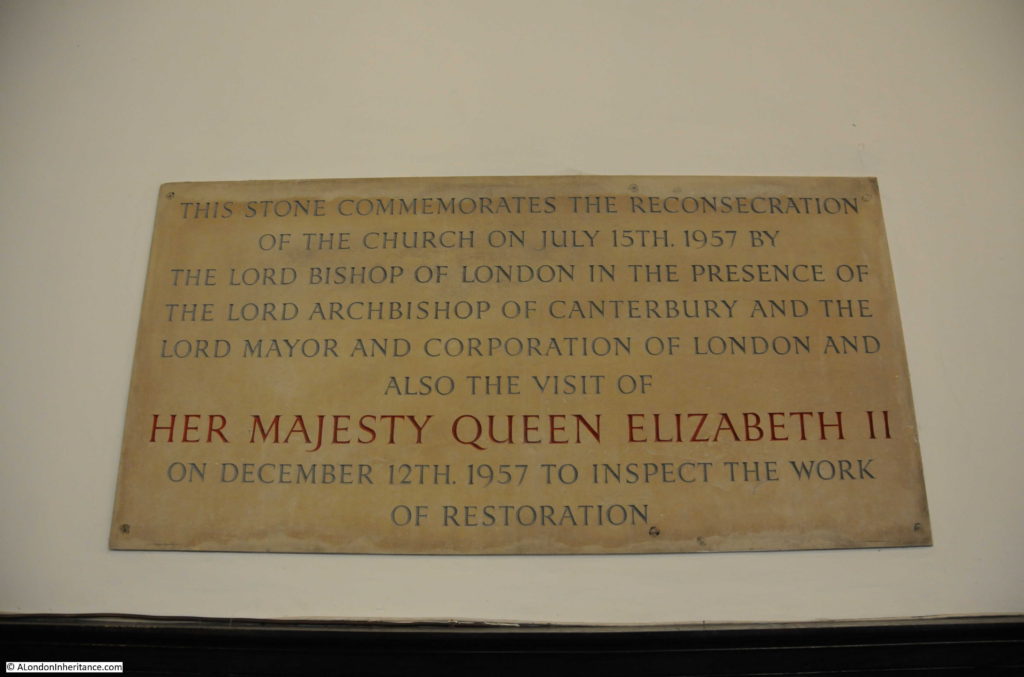

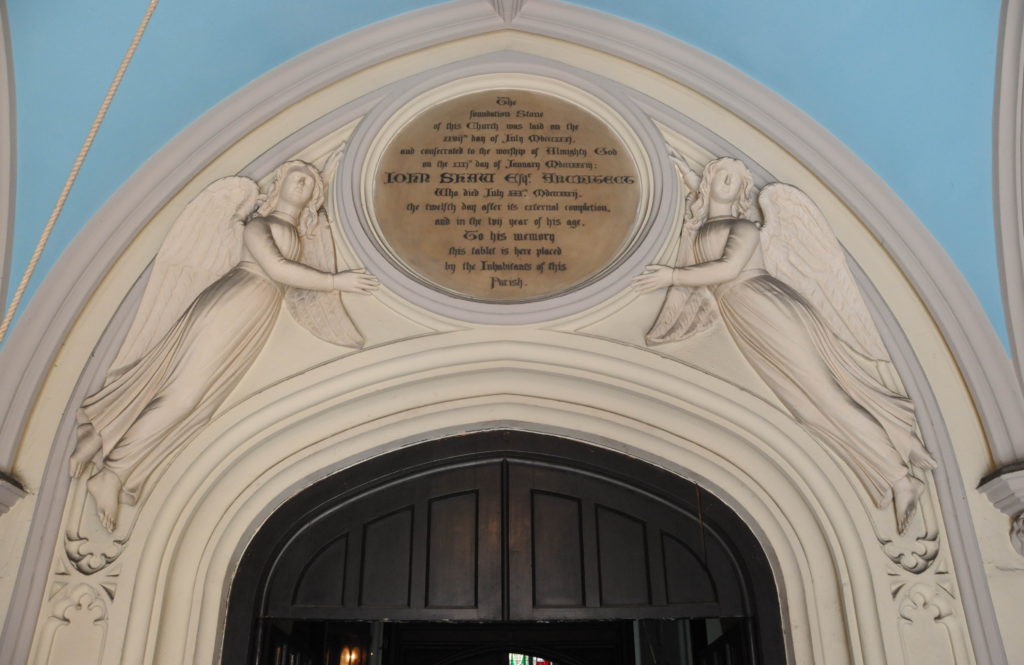

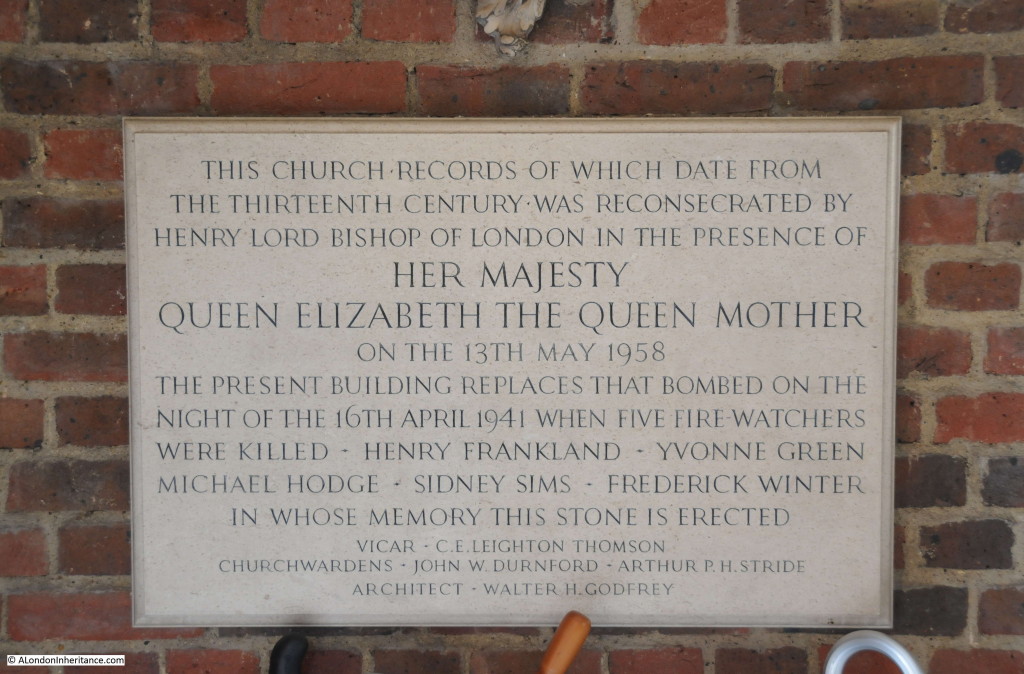

A plaque on the wall of the church commemorates the post war reconstruction:

The destruction of the interior required new furniture which was donated by the City Livery Companies. Items for the church also came from other churches. Many of the pews came from Holy Trinity Marylebone and the font which dates from 1620 was a post war relocation from Holy Trinity Minories.

The church in late afternoon autumn light:

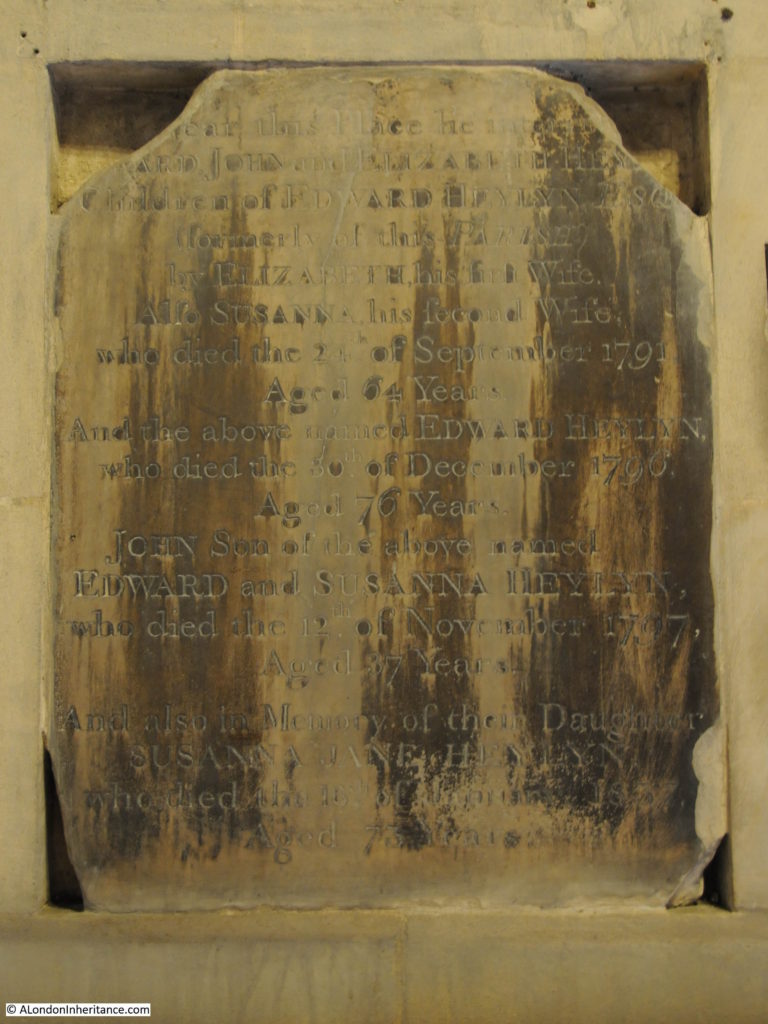

The church has lost its churchyard and bombing destroyed the majority of the interior monuments, however a few monuments and gravestones are preserved, including this 18th century monument to several members of the Heylyn family.

St. Lawrence Jewry once had a small churchyard as shown in Rocque’s map and one of the 18th century prints shown above. The area between the church and the Guildhall was also built up with only a street running from Gresham Street up to the main entrance of the Guildhall.

This area is now a large open space, as shown in the following photo. I am standing at the edge of the church in what was once the churchyard.

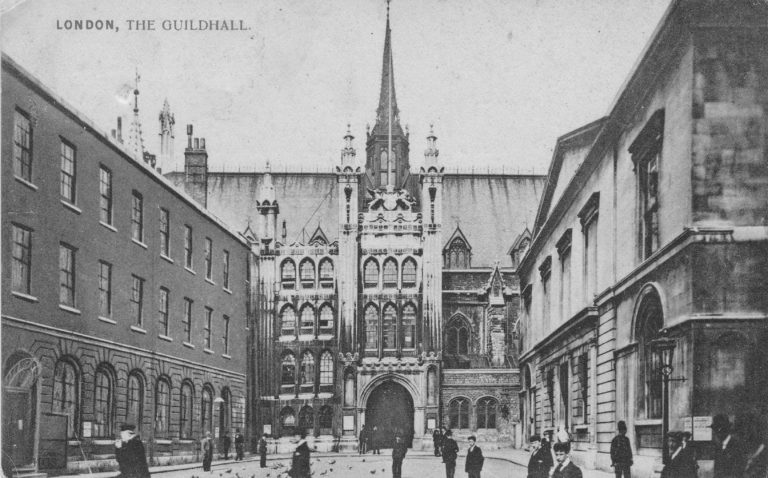

The Guildhall also suffered extensive damage during the same raids that destroyed St. Lawrence Jewry – that is another story for the future. The following postcard shows the buildings on the left between the church and the entrance to the Guildhall.

On the north east corner of the church is an old, hardly readable wooden sign that reads “Church entrance in Gresham Street”. It looks very old, but I cannot believe it is pre-war as being wood I doubt it would have survived the fires.

Gresham Street and St. Lawrence Jewry were my last locations to visit after a walk from Canary Wharf, through Shadwell and Wapping to the City, to visit sites for a couple of my posts over the last month, and a few more for future posts. Very different start and end points, but both with so much to tell of London’s history, however at this point, the main thing on my mind was finding a local pub.