In August of last year, I was standing on the Stone Gallery of St. Paul’s Cathedral on a beautiful sunny day with London looking fantastic in all directions. I had my iPad with me which contained photos my father had taken from the same place just after the war, showing a very different London. I covered these photos in two posts which can be found here and here.

Looking at the devastation caused by wartime bombing, it was remarkable that St. Paul’s survived relatively unscathed. How had this happened, and what would it have been like to have experienced such a dramatic event in London’s history?

I wanted to find out more, and I have written two posts consolidating the results of some research carried out since that August day. I decided to pick one day’s events to provide some focus. The bombing on the 29th December 1940 caused fires of such intensity and scale that it became known as the 2nd Great Fire of London and from a distance it appeared that St. Paul’s would be lost.

I have split this across two posts which I will publish over two days on the 3rd and 4th of January 2015. This post covers the St. Paul’s Watch, the volunteers who protected the Cathedral during the war. The second will cover the night of the 29th December 1940, the 2nd Great Fire of London.

My apologies for the length, however I hope you will find these two posts as interesting to read as I did to research. (Unless otherwise stated, in this post, all photos and documents are from the St. Paul’s Cathedral Architectural Archive).

So let’s start with:

The St. Paul’s Watch

In the months leading up to the start of the 2nd World War, there was much preparation in London for what was expected to be a devastating war from the air. Limited bombing during the 1st World War had shown the possibilities, further developed in the Spanish Civil War and then by the Blitzkrieg or lightning form of mechanised warfare used by Germany in the attack on Poland which was the catalyst for bringing the UK into formal war with Germany.

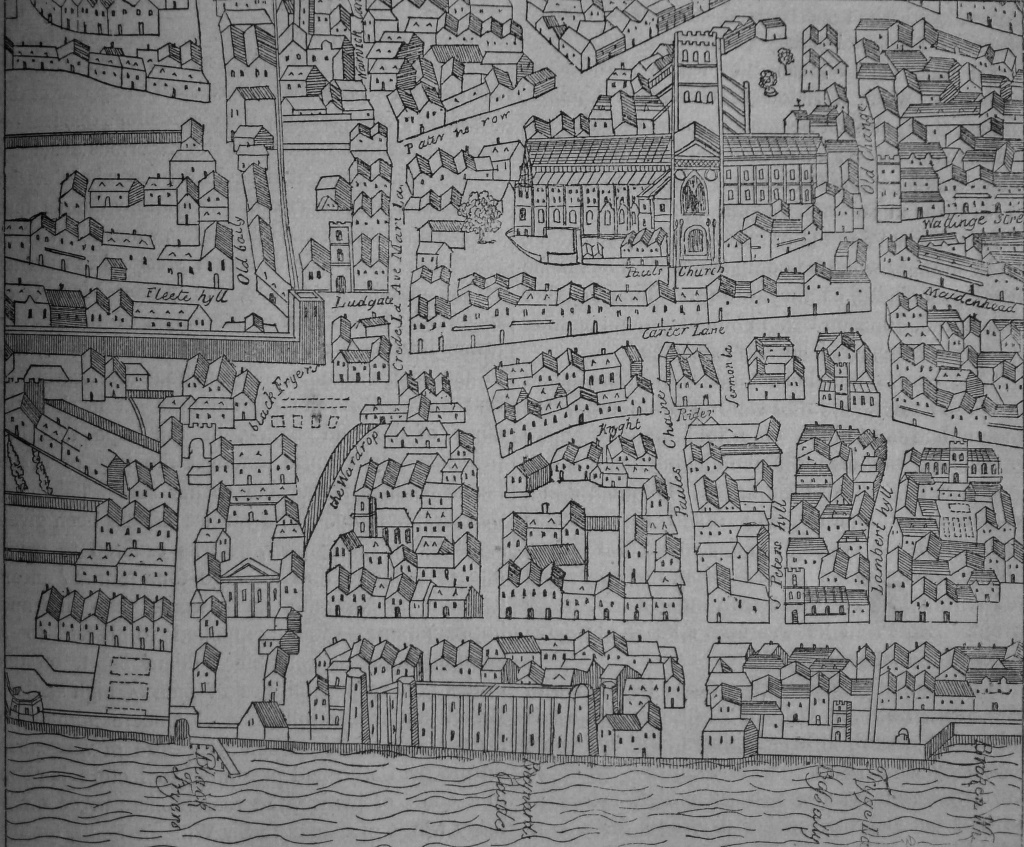

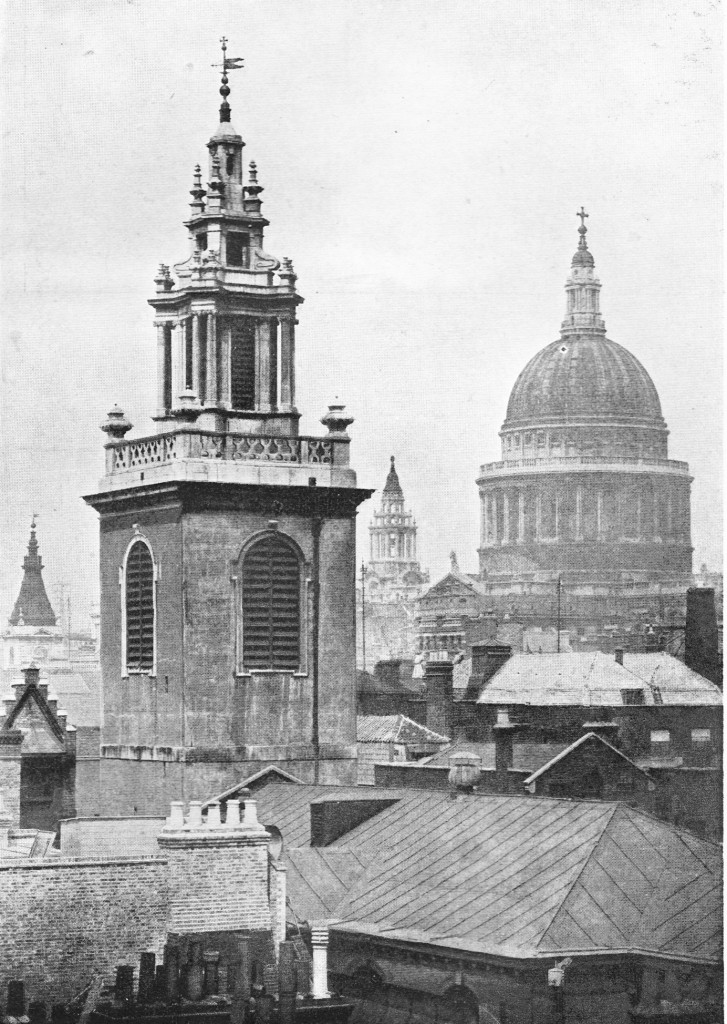

St. Paul’s Cathedral was considered at high risk from aerial bombing. Unlike today, the Cathedral was by far the tallest building in London, standing clear on one of the two hills that formed the original City. Not only was the Cathedral an architectural masterpiece created by Wren, one of London’s main architects after the Great Fire, it was a central landmark in the life of Londoners and to the nation.

In the month’s leading up to the start of the war, the Cathedral started to prepare. On Saturday, 29th April 1939 one of the regular meetings of the Chapter of St. Paul’s was held, and although a regular meeting, this day’s session was different, it was to start planning for how the Cathedral could be protected.

During the 1st World War, a volunteer watch had been kept at the Cathedral and it was along these lines that planning for the new threat was made, with the creation of a volunteer Watch who would have responsibility for defending the Cathedral against any form of aerial attack.

Mr Godfrey Allen, the Cathedral Surveyor was appointed to command the Watch and preparations were made to put the Cathedral onto a war footing.

One of the first challenges was to find sufficient manpower to mount a fulltime, day and night watch over the Cathedral. This was at a time when the majority of the able-bodied, younger male population was expected to be involved within the armed forces. The Cathedral Watch initially started with 62 volunteers from the Cathedral staff, however this number was not sufficient to maintain a full 24 hour Watch over the Cathedral and many of these volunteers were also approaching retirement and when action was needed across the heights of the Cathedral, in the roof spaces, under the Dome etc. additional support was needed.

At the suggestion of Mr Godfrey Allen, a request by the Dean was made to the Royal institute of British Architects (RIBA) for volunteers to join the Watch. RIBA was a perfect match with members having knowledge of architecturally complex buildings and therefore perfectly suited to working in a building such as St. Paul’s and the age profile of experienced architects probably made a larger pool of people available.

The Dean of St. Paul’s made the following appeal:

“St. Paul’s Cathedral is in urgent need of double the present number of Firewatchers. The average strength at the moment is about 20 men a night. Dr. W.R. Mathews, the Dean, is sending out an appeal for volunteers and his first letters have gone to the Royal Institute of British Architects and to the High Commissioners for each of the dominions. He stated yesterday that the work is interesting and volunteers have the unique privilege of being given the freedom of the Cathedral. They are expected to watch one night a week; but the hours of duty can be adjusted to suit individual requirements. The watchers are required to be at the Cathedral not later than 9.30 PM. Subsistence allowance is paid and bunks, blankets and mess room accommodation are provided.”

I would have thought that being given the freedom of the Cathedral would have been a considerable incentive for anyone interested in the architecture and history of the building.

The appeal was successful as another 40 volunteers came forward, with the first full meeting held on the 15th September 1939 and from the 25th September a regular “night shift” from 9.30pm to 6.30am was maintained.

Whilst the Watch was made up of volunteers, it was far from an amateur operation. Under the guidance of Godfrey Allen the Cathedral was prepared and the members of the Watch participated in an extensive series of lectures, training and exercises to prepare them to work in the expected intense bombing to come.

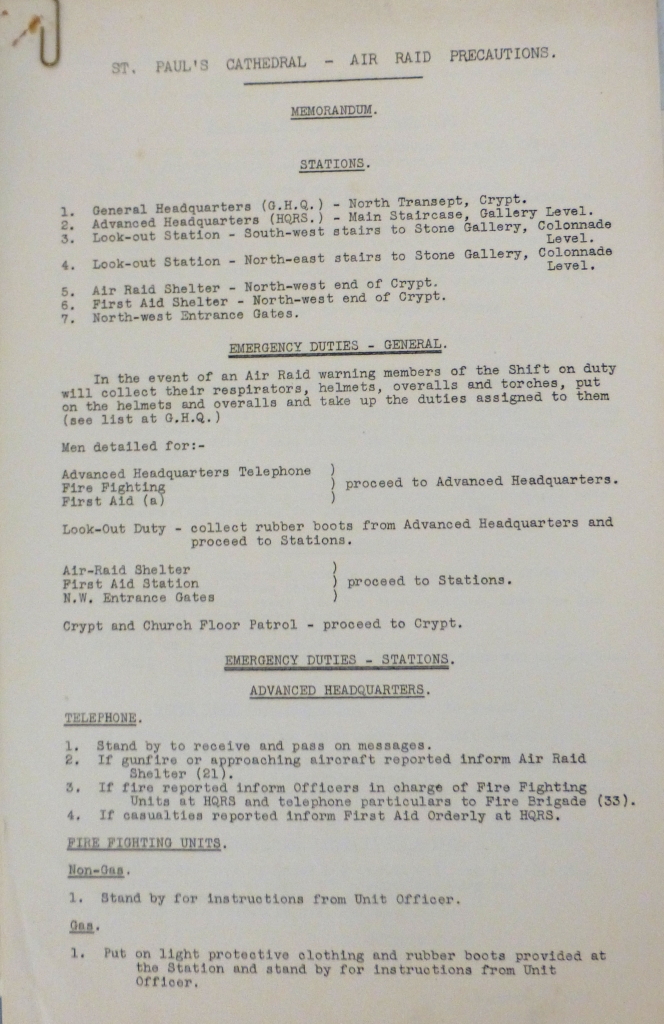

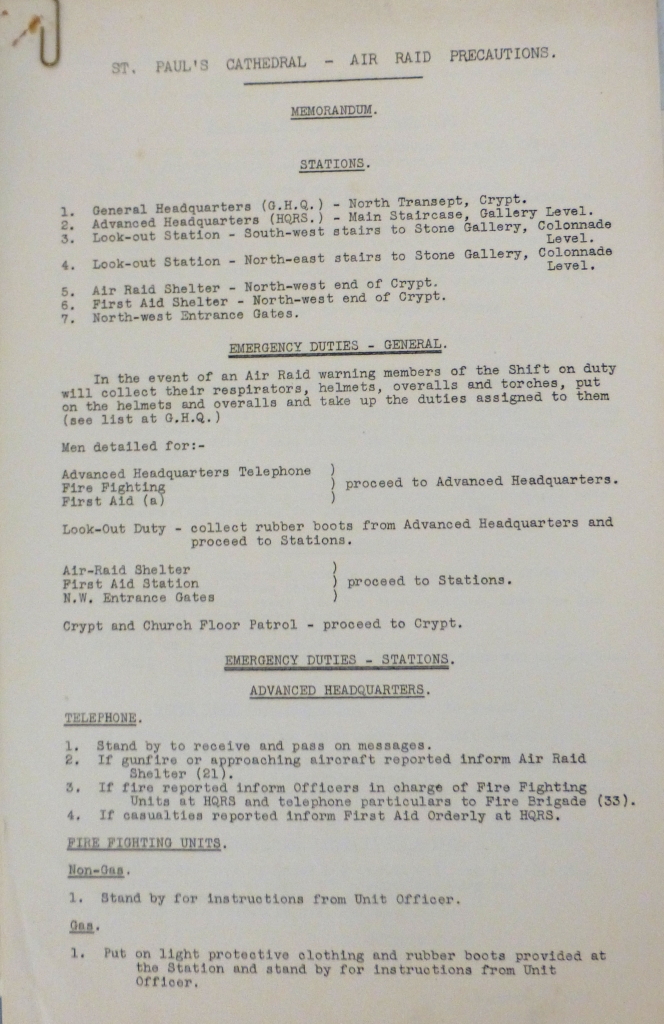

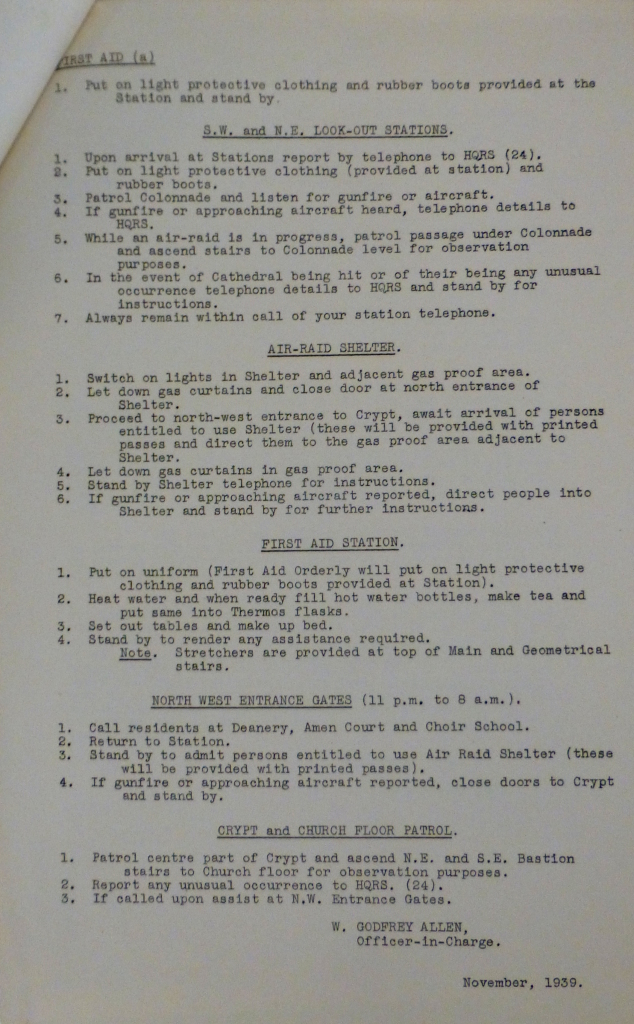

Many of the original lecture notes and training material remains in the archives at St. Paul’s. The following two pages are the initial Air Raid Precautions documented in November 1939. The level of planning and preparation is very clear and highlights what is needed to protect such a complex building as St. Paul’s.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Note the reference to “gas proof area” and “gas curtains” in the following page. This was before any serious bombing had commenced and there was still an expectation that as well as explosive bombing, London would also be attacked with poisonous gas. Exercises included first hand experience of gas. A hut in Cripplegate was used to provide the experience of passing through a chamber filled with tear gas. Fortunately this was to be the only contact that London and the members of the Watch had with the much dreaded gas.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The complexity of St. Paul’s, the numerous stairs, small corridors, access to roof spaces, access to the external roofs, access to the interior of the Dome etc. were a considerable challenge for those volunteering and without an in-depth knowledge of the building. Many sessions were held, training the members of the Watch to find their way around the Cathedral. Where to find equipment, water supplies, telephones etc. and to be prepared to do this whilst the Cathedral was in the dark, being bombed, on fire and with the constant threat of high explosive bombs.

To give some idea of the types of small corridors that connect different parts of the upper building, the following are two photos that I took on the way to the Archive.

Adding to the challenge of trying to get to the site of a fire, the Watch would probably have to work through these corridors by torch-light whilst carrying tools and buckets of water. Remove the electric lighting, cabling and pipes and these corridors are probably unchanged since the time the Cathedral was originally built.

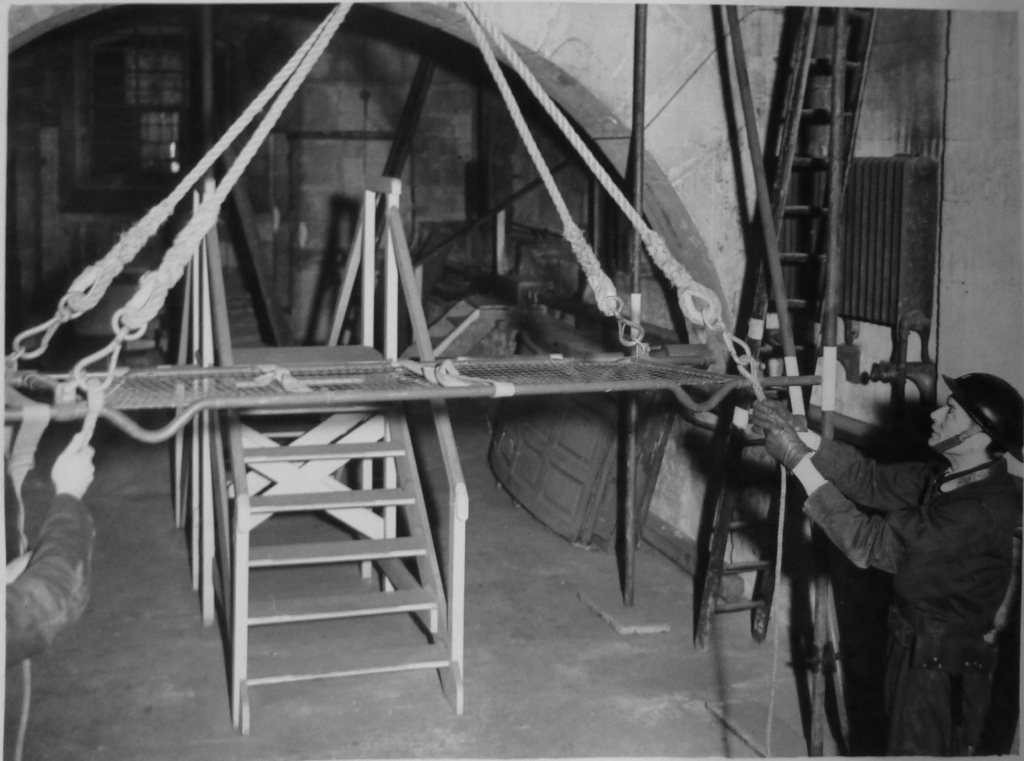

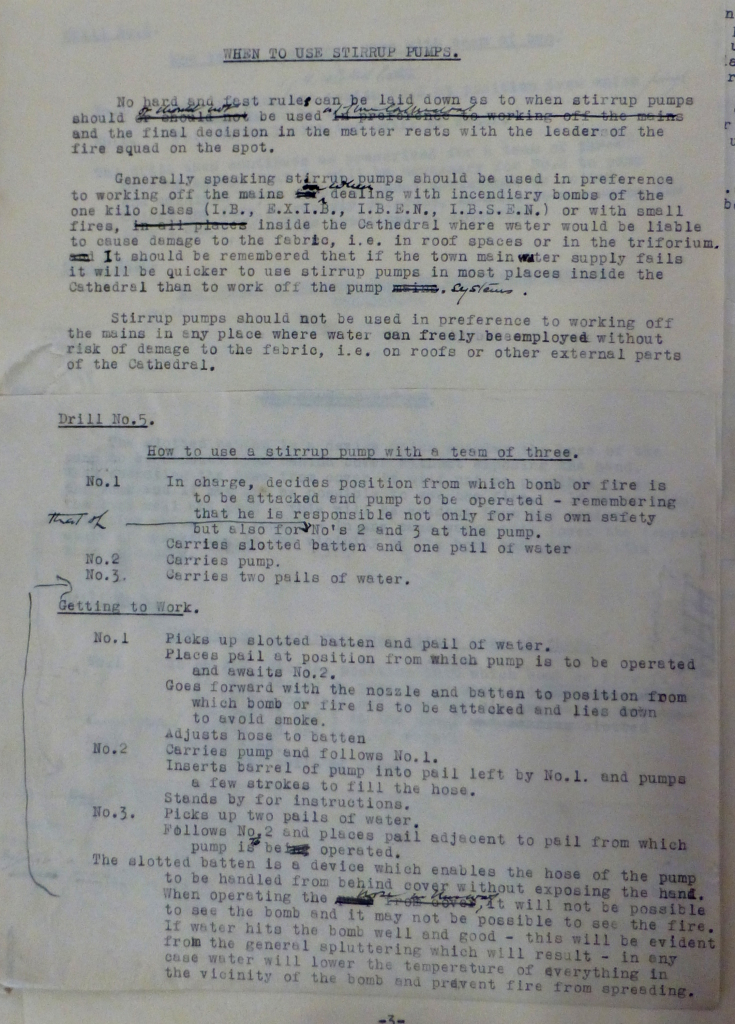

There were a number of key factors to be considered when fighting a fire.

Large quantities of water could do damage to the fabric of the building. There was a balance to be achieved with using the right approach to extinguish a fire without causing undue damage to what is an architecturally complex and delicate building.

There was the issue of access to difficult locations. In a building as complex as St. Paul’s with many small, hidden locations, access to a large quantity of water was just not possible.

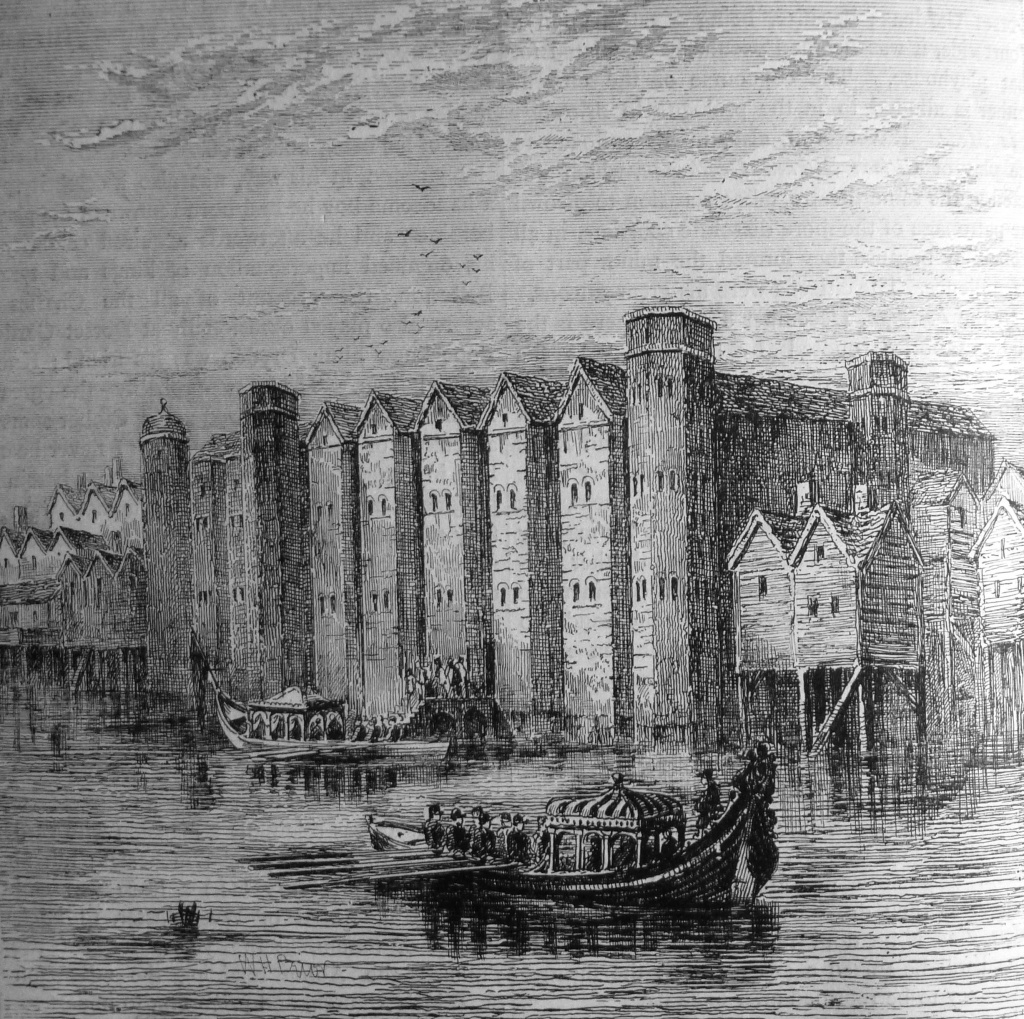

And availability of large quantities of water was always a concern as would be demonstrated on the night of the 29th December 1940. Water would be required not just for St. Paul’s, but also to protect all the buildings in the City. Storage was a problem, the River Thames was tidal and bombing could also damage the pumps extracting water from the river and the complex pipes and hoses bringing water up from the river along the City streets.

One of the key tools in use by the St. Paul’s Watch was the Stirrup Pump. The following photo from the Imperial War Museum collection © IWM (FEQ 864) shows a typical Stirrup Pump in use by the St. Paul’s Watch:

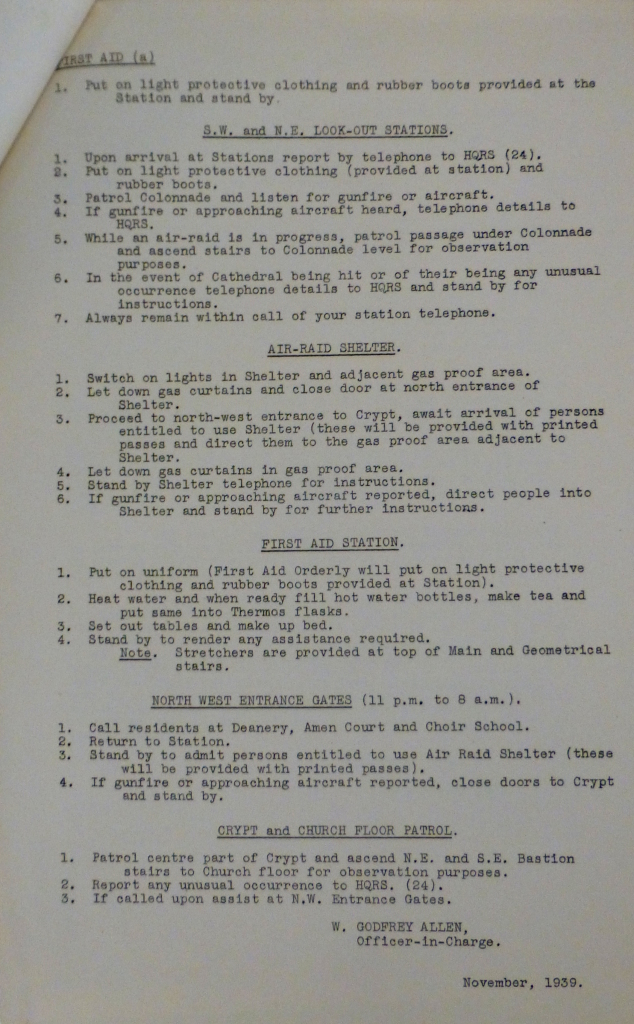

The Stirrup Pump was in such great demand as a fire fighting tool that at one stage, just a single factory in 1941 was producing 10,000 a week. As with all other areas of the Watch, there were detailed instruction and training in the use of the Stirrup Pump.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

It is interesting to read in one of the introductory lectures that the Cathedral was classified as a “business premises” with the Dean and Chapter being the occupier. As the occupier, their responsibilities were clearly defined as:

- for organising the fire watch;

- for supplying equipment, appliances and water;

- for the instruction and training of fireguards;

- for keeping a register of all attendances and defaults;

- for giving directions as to the place and time the fireguards are to perform their duties;

- for providing sleeping accommodation, bedding, adequate sanitary arrangements and lighting;

- for providing facilities of access to all parts of the building, except such parts as may reasonably be excluded

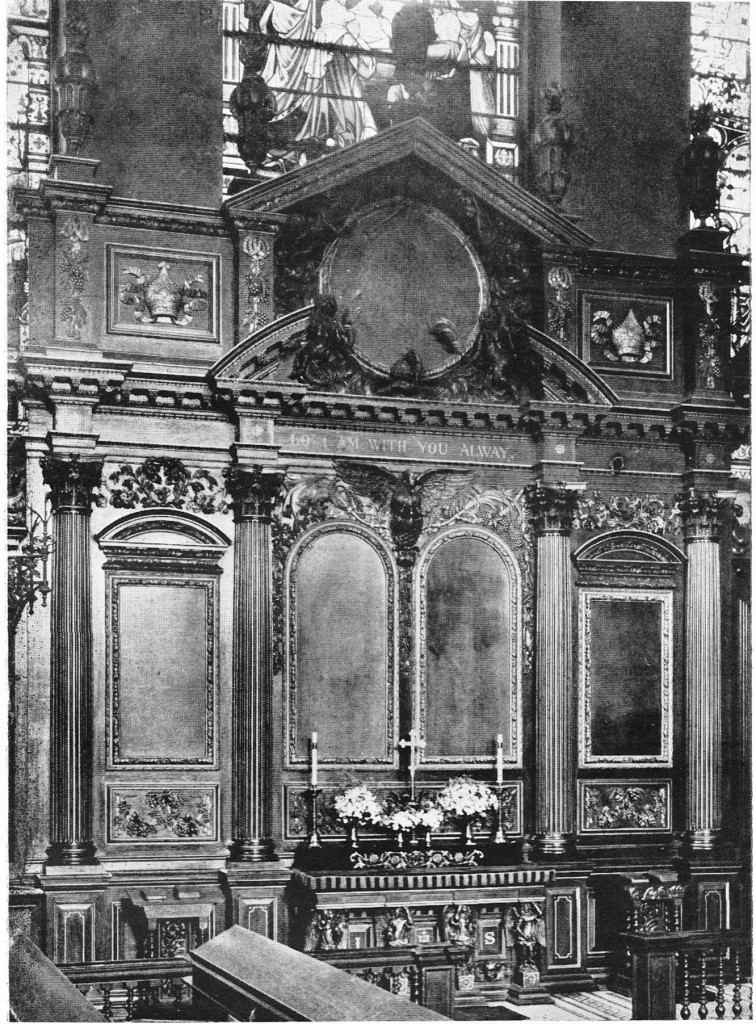

As well as the Watch, St. Paul’s was also prepared for the possibility of direct bombing by the removal of all that was possible to remove and the protection of anything that could not be removed.

The Grinling Gibbons Choir Stalls were dismantled with the more valuable pieces being sent out of London, the rest being stored in the crypt. The ironwork gates by Tijou along with Wren’s model of the Cathedral were also sent out of London. The rarer books were sent from the Library to the National Library of Wales.

Statues and busts which could be moved were relocated to the crypt. For anything that could not be moved, for example the memorial tablets to the Wren family, they were bricked in to provide some degree of protection.

There are a number of photos in the Cathedral Archives that show the Watch. These appear mainly to be posed photos, possibly for newspapers and magazines, however they provide a very good record of the Watch and their working conditions.

A lecture class given in the Stewards Office:

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

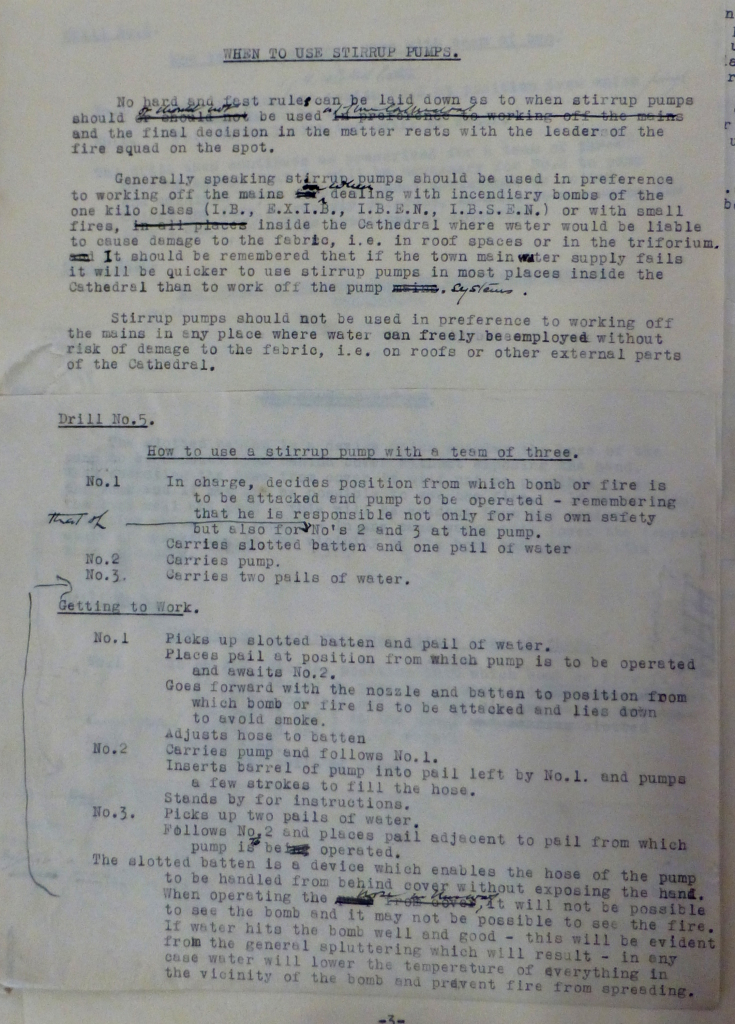

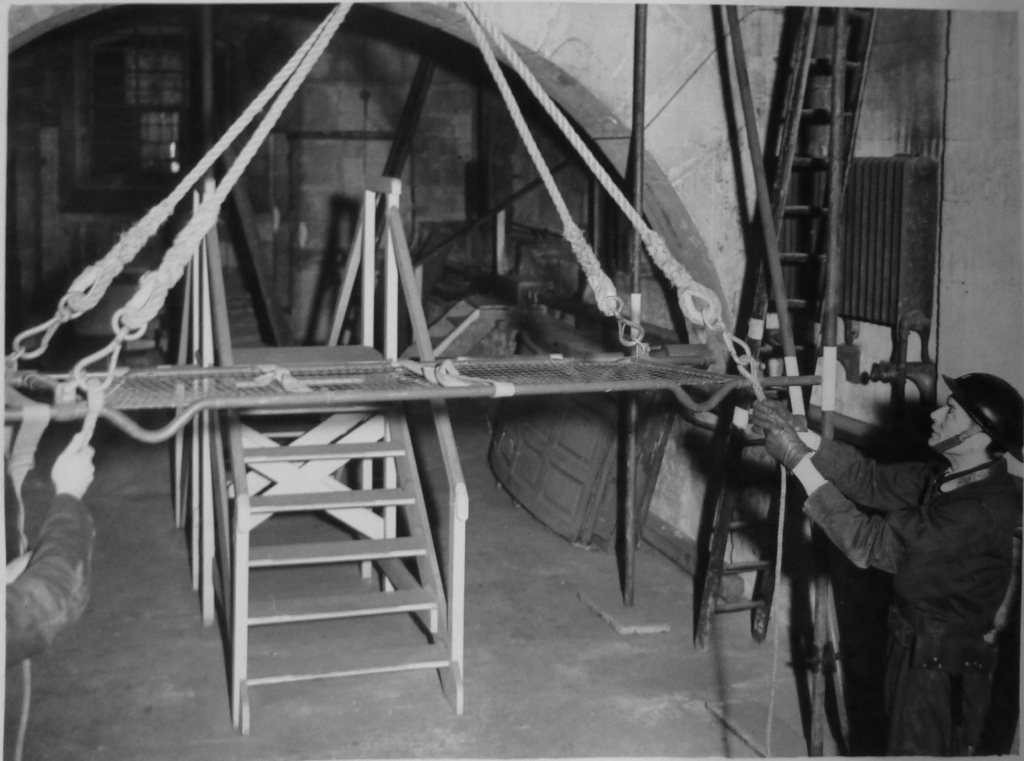

The following photo shows Stretcher Practice in the Dome galleries. In preparing for any bombing, there was a very real concern that the Watch could suffer injury. The Watch would not have waited until bombing has ceased to go out and fight fires, the Watch would have been across the roofs, in the Dome etc. looking out for damage, fighting fires and checking for incendiary bombs that had lodged in hidden parts of the Cathedral in the middle of raids.

Bringing those injured down the long stairs from the upper reaches of the Cathedral was not considered practical, therefore arrangements were in place and tested to lower casualties on stretchers over the edge of the upper areas (for example the Whispering gallery) and lower them down to the ground floor of the Cathedral. I am not sure what would have been more frightening, the external threat from bombing, or being lowered in one of these from the great heights of the Cathedral.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Another photo showing stretcher lowering being tested:

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The risk of injury or death was not just when on Watch in the Cathedral. The journey into the Cathedral was just as intense. From St. Paul’s Cathedral in Wartime by the Dean of St. Paul’s:

“Many of our members came from distant parts of London and the task of getting to St. Paul’s on many a noisy night might have daunted the stoutest heart, but it did not daunt the Watch. They came through darkness, falling shrapnel from our guns, and the debris of wrecked buildings, sometimes having to throw themselves on the ground when a bomb fell near, on foot or on bicycle when other transport failed, they came to keep their Watch, whilst those they relieved made similar nightmare journeys home. Men at the look-out posts on the roof glanced occasionally towards their homes and offices wondering what they would find there on the morrow. Some saw their homes go up in flames, but they did not flinch”

This rather puts the modern-day irritation of a delayed train on the way home in context.

The following photo shows members of the Watch at one of the advance locations around the Cathedral:

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

And another similar photo:

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Locations were set-up around the Cathedral that could be used as waiting and reporting points and to control specific areas of the Cathedral. Each was equipped with a telephone to enable reporting back to the Control Station in the Crypt of the Cathedral.

These photos also show the ages of the Watch. In 1939 conscription covered males of between 18 and 41 and by 1942 this has been extended to the age of 51. This would have limited the pool of men available to the Watch only to those over the age of conscription.

The remainder of 1939 and the first half of 1940 was relatively quiet for the Watch. Training progressed, exercises were performed and the Cathedral was prepared as best as possible for what was still a threat that whilst imagined had not yet been experienced.

Bombing of central London of any intensity started in August 1940 when on the 24th there was some limited bombing of the City with two bombs near the Cathedral. The first air attack took place on the 7th September when an attack was concentrated on the London Docks. Members of the Watch experienced this first major raid from the high points of the Cathedral. From the Dean’s book:

“It was a golden, peaceful evening and, as the light faded from the sky, the angry red glow in the east, diversified by leaping flames, dominated the prospect, while from time to time the peculiar thud of bursting bombs punctured the silence. We were a silent company as we gazed upon the apocalyptic scene, each no doubt pondering many things. We noted, without remark the apparent absence of defence – an observation which we were to make often in the next few weeks. We wondered how long it would last before the attack moved westwards to the heart of London. We feared that the whole port of London was being annihilated. At last someone spoke, “It is like the end of the world,” and someone else replied, “It is the end of a world””.

For the Watch training and preparation continued. Note the Watch members assigned medical tasks in the following photo with the cross on the white helmet.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Axes and hoses were key components of equipment, however hoses were very dependent on having a readily available source of water under pressure.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The availability of water was a constant issue for the Watch team. As would be found on the 29th December 1940, when water from the River Thames could not be relied on. Damage to pumps and pipes was always a risk, but also low tides in the river which took the main body of water below the level of the intake pipes.

The Cathedral had then as well as now a riser system providing distribution around the Cathedral:

However in the event of mains supplies of water failing, these would be of little use. The Watch team prepared the Cathedral by storing supplies of water in all areas of the Cathedral using any form of container that could hold water. This would be invaluable in fighting the fires on the 29th December.

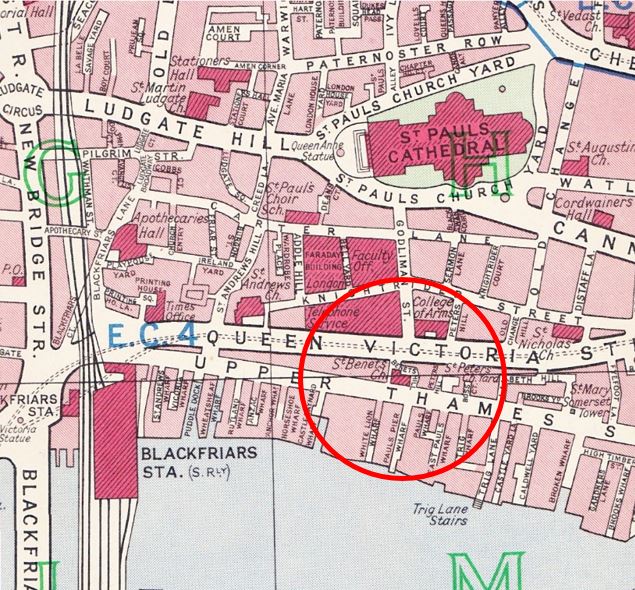

The area to the immediate north of the Cathedral was destroyed in the raid of the 29th December. In the following months the buildings were cleared and water storage tanks installed. The outlines of these were still visible in the photos my father took from the Stone Gallery after the war. The following photo taken from the Cathedral shows the tanks in place, a couple of which can be seen in the lower right of the photo.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

Following the initial raids, the St. Paul’s Watch settled into a routine of periods when there would be intense activities, raids almost daily for a number of months, followed by periods of quiet, a time to regroup and repair damage.

The Watch were critical in protecting the Cathedral from fire and the huge amount of incendiary bombs that fell on the City. The Cathedral suffered a few direct hits from high explosive bombs during the war. The following photo shows bomb damage in the North Transept caused by falling debris.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The Cathedral had a very narrow escape on the 12th September 1940. The night had been one of intermittent attacks and in the early morning a high explosive bomb fell very close to the South West Tower. It narrowly missed the tower by a few feet and penetrated deeply below the road surface. The bomb did not explode, but due to the soft clay beneath the surface, the bomb gradually sunk deeper, eventually to reach a depth of 27 feet 6 inches below the surface.

The bomb was removed on the 15th September and taken to Hackney Marshes where the bomb was blown up, it left a crater 100 feet in diameter. Had the bomb exploded on impact it would almost certainly have taken out the whole of the South West Tower and much of the West front of the Cathedral.

There was very little that the Watch could do with an explosive bomb. If one hit the Cathedral it would explode on contact, any bomb that did not explode, either due to a fault or a delayed action fuse, was left to the professional bomb disposal teams.

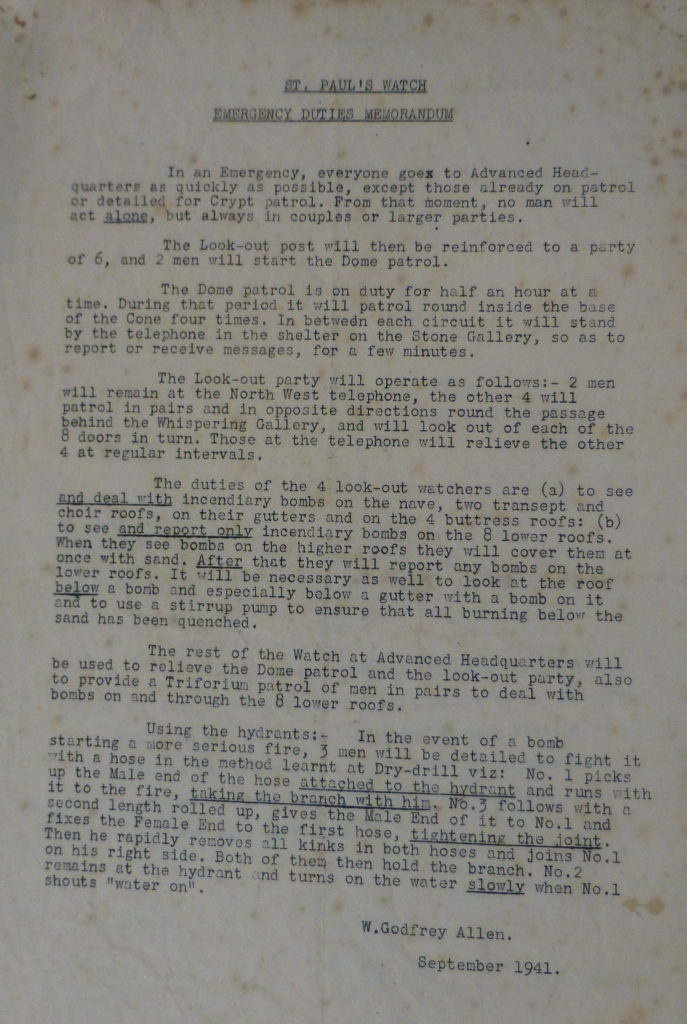

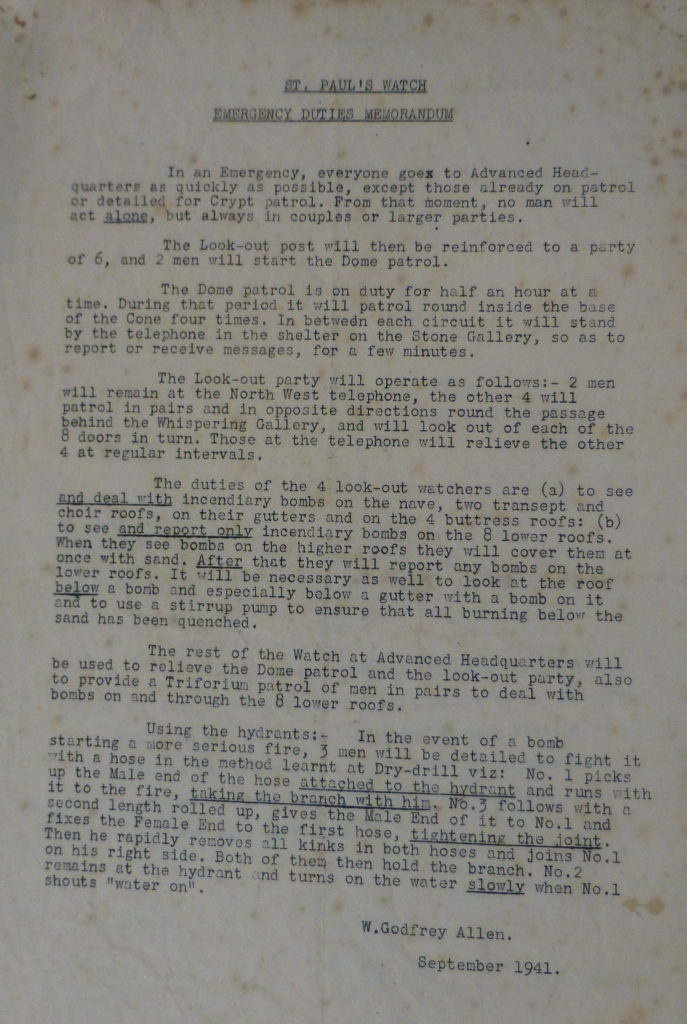

Emphasis for the Watch was always on the roofs of the Cathedral, the Dome and the risk of fire. The following memorandum from Godfrey Allen in September 1941 details the duties and procedures to be used in an emergency.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The Dome patrol was critical to ensure that a fire could not get hold in the timbers supporting the Dome. The Dome must have been a strange place to be during the height of a raid. In his book, W.R. Matthews recorded that:

“The Dome was not a healthy place in the height of a blitz and the patrol was changed at half-hourly intervals. Men have told me of the awesome feeling they experienced when carrying out their patrols in the darkness of the Dome while the battle ranged around them and of how the din seemed to be magnified by the Dome, like the beating of a drum. If they had any compensation it was perhaps that of witnessing from their lofty perch of the Stone Gallery the spectacle of the Battle of London as few others can have seen it.”

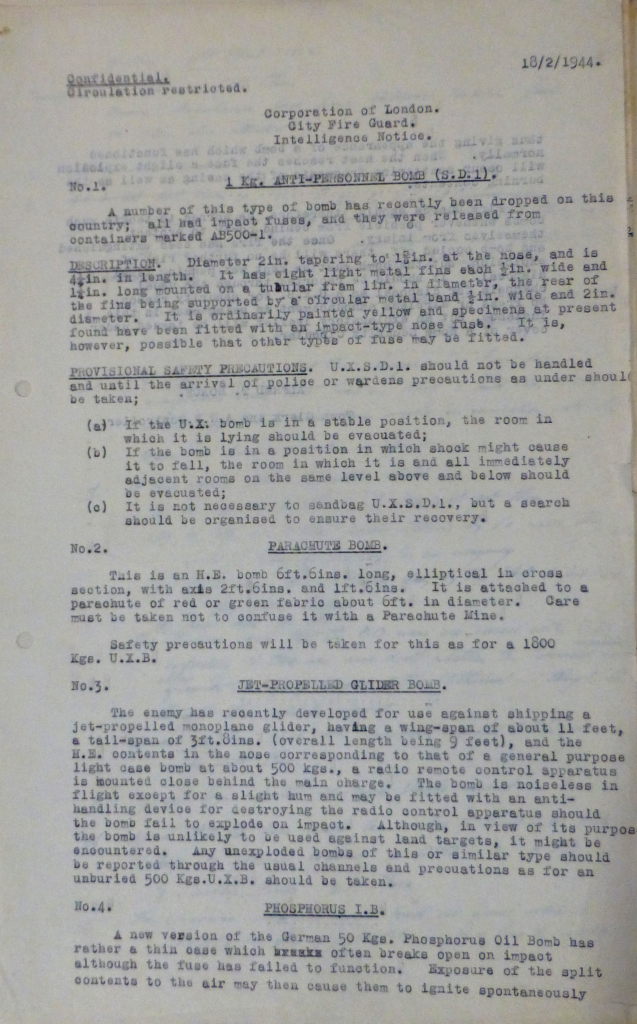

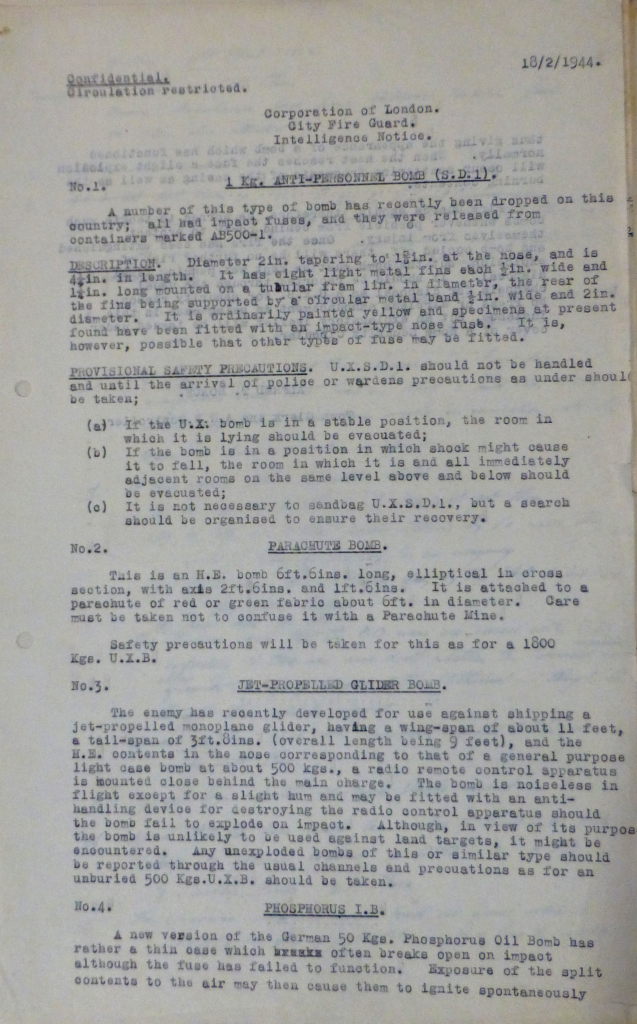

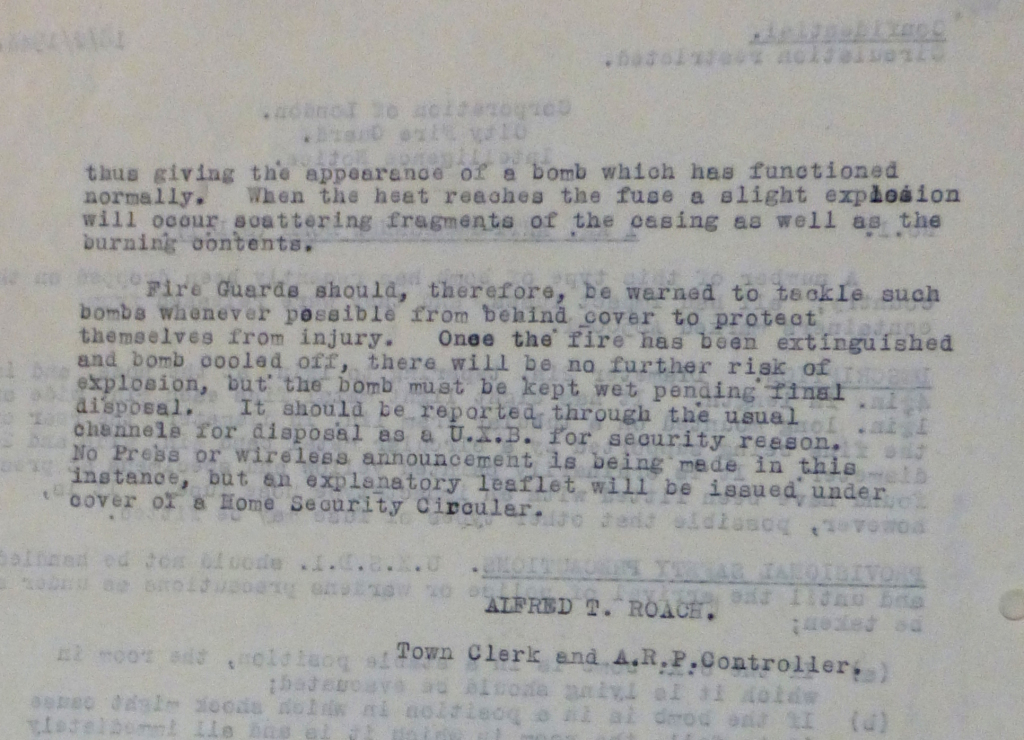

Training continued throughout the war, the types of threats continued to evolve and updates from the appropriate authorities provided the Watch with information on the threats they may have to face.

The following two pages are an Intelligence Notice from the Corporation of London detailing new models and versions of bombs.

- A 1Kg Anti-Personnel Bomb

- Parachute Bomb

- Jet-Propelled Glider Bomb

- A new version of the Phosphorus Incendiary Bomb

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

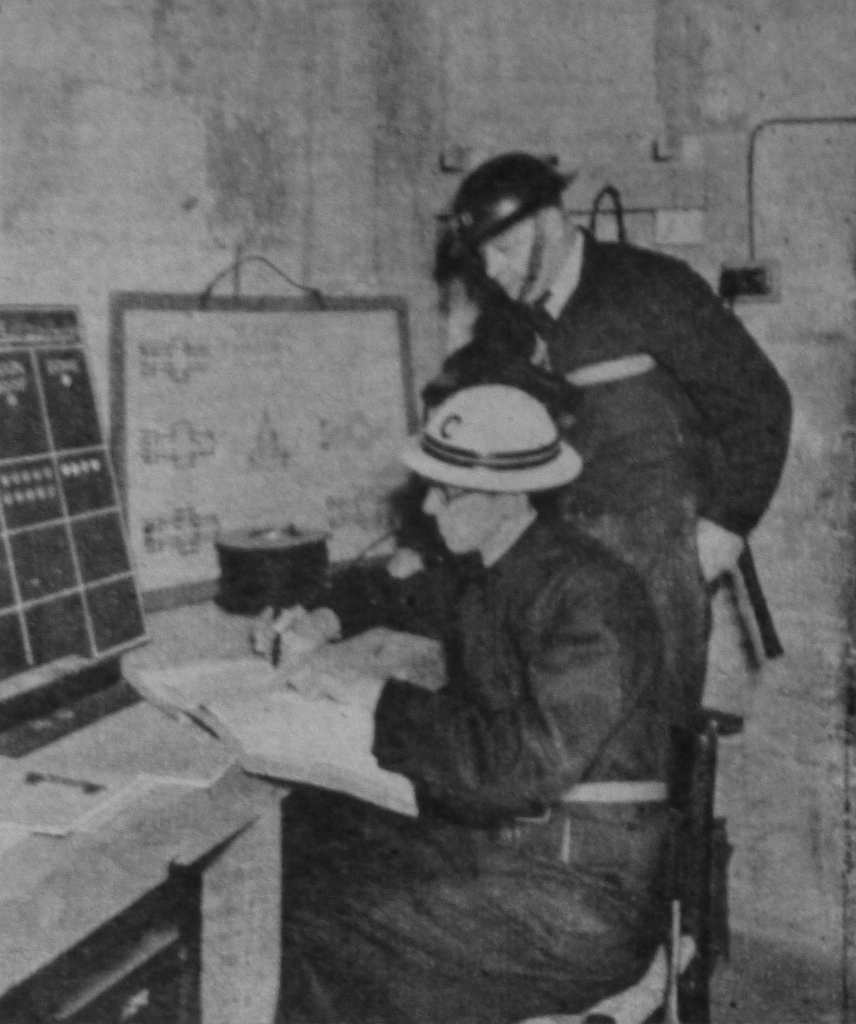

In researching the work of the Watch, one name keeps recurring, whether as the author of much of the training materials and instructions for how the Watch should operate, to the very limited number of books that have been written about the Watch. Godfrey Allen was the Surveyor of the Fabric before the War (he held the post from 1931 to 1956) and took on the command of the Watch for the duration. It was not only his intimate knowledge of the construction and layout of the Cathedral, but also his organisational abilities in moulding the Watch into the team that protected the Cathedral during the height of the blitz. He was also responsible for the immediate repairs needed to those parts where bomb damage had been suffered, both the immediate repairs to protect the building from the elements, but also the long-term repairs.

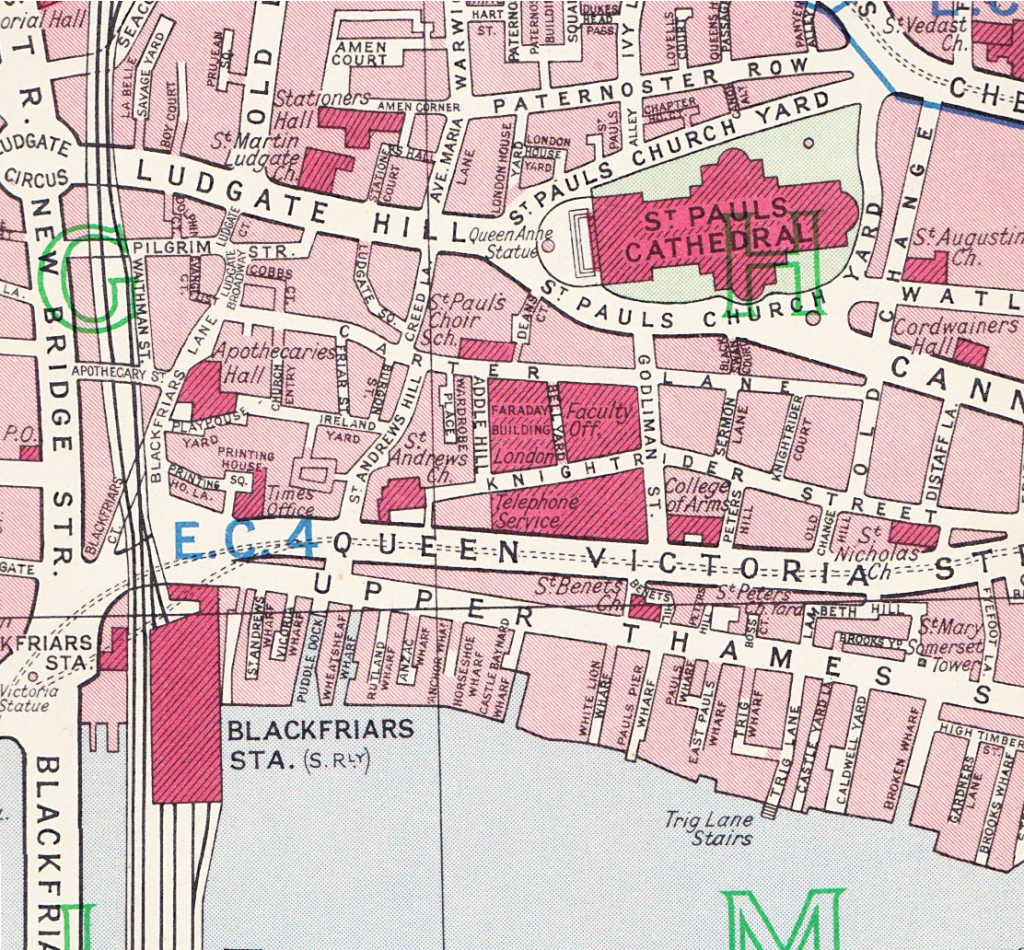

Before the war, Godfrey Allen was also responsible for the St. Paul’s Heights policy. These were put together in the 1930s following the construction of The Faraday Building and Unilever House, which started to obstruct the views of St. Paul’s. The Heights Policy has remained in force ever since and is now part of the Local Development Framework of the City of London.

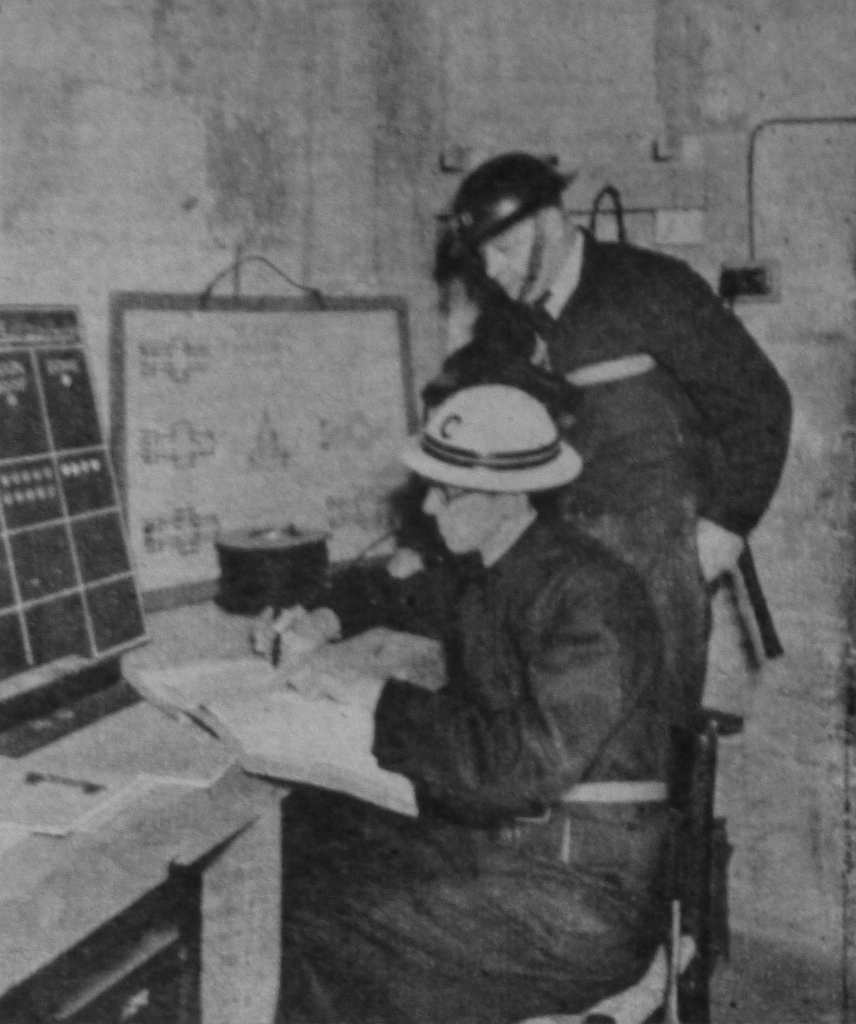

Mr Godfrey Allen (in the white hat) in the crypt control room.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

The Dean of St. Paul’s wrote at the end of the war “If any one man could claim to have saved St. Paul’s, that man is Mr Allen”.

The Christmas and New Year card sent by Godfrey Allen to members of the Watch for Christmas 1940, during and continuing into the peak period of the London Blitz.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

During the latter stages of the war, there were no threats to the Cathedral (apart from the period of V1 and V2 rocket attack), however the Watch still maintained a nightly vigil. To help with the monotony of nightly exercises the Watch organised a series of lectures and the following provides an example of the lectures from one week in January 1945:

| C.A. Linge |

The Preservation of Durham Cathedral |

| J.D.M. Harvey |

Time |

| J. Steegman |

Iceland to Istanbul n Wartime |

| R.M. Rowett |

Women in Poetry |

| P.B. Dannett |

Some Lantern Slides, Record and Pictorial |

| Basil M. Sullivan |

The People of India |

The Watch continued until the very end of the war in Europe. The “stand down” of the Watch was arranged and an act of worship planned for the final meeting of the Watch on the 8th May 1945. By coincidence, this was also the day that the German forces surrendered, VE day and the Cathedral was crowded all day long with frequent services held from early morning to dusk (an estimated minimum of 35,000 people attended the services during the day along with countless others who called into the Cathedral to mark the day’s events). The final meeting of the Watch took place at the end of the day’s public events.

© The Chapter of St Paul’s Cathedral

One of the closing paragraphs from Godfrey Allen’s reply to the Dean during the Service of Thanksgiving sums up what the members of the Watch must have felt at the end of such an intense period in their lives as well as in the history of St. Paul’s and London.

“To many of us, I am sure, these years will prove to be the most memorable of our lives and when we recall them in the quiet of our homes we shall think, not only of the horror and waste of those dreadful days and nights, but also of the great building which bound us all together and for which we fought with all our might.”

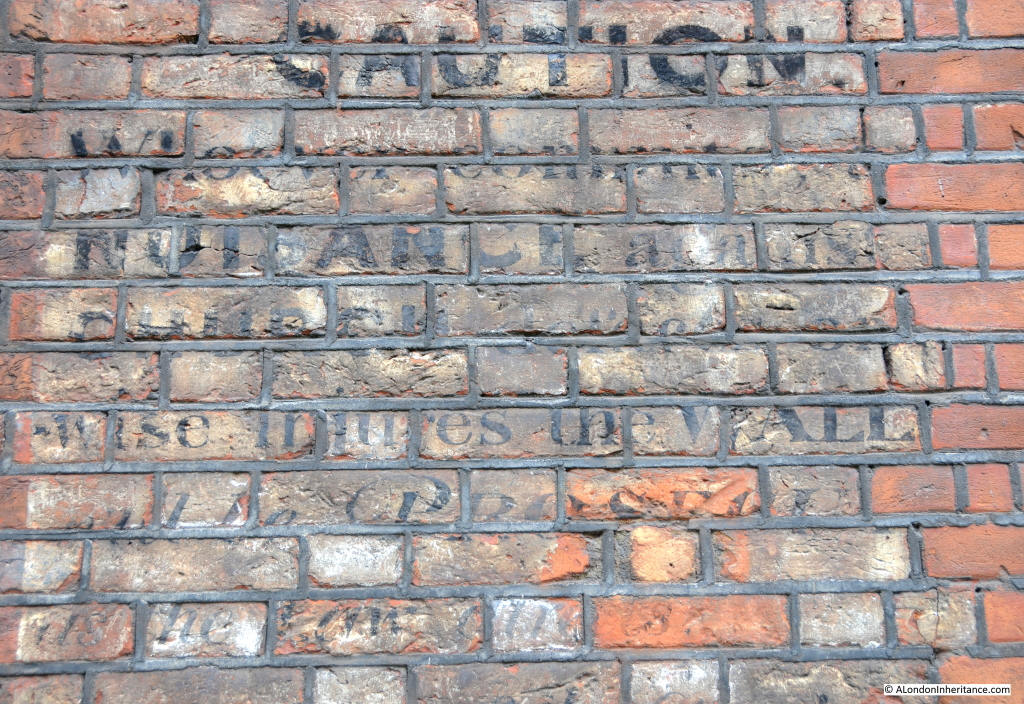

To provide a lasting reminder of the work of the St. Paul’s Watch, the following tablet was set in the floor by the western end of the Cathedral:

In tomorrow’s post I will cover the night of the 29th December 1940, the impact to the area around St. Paul’s Cathedral, and how the Watch protected the Cathedral from the surrounding devastation.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- I am very grateful to Sarah Radford, Archivist at St.Paul’s Cathedral for providing access to the documents covering the St. Paul’s Watch

- The Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral during the war, the Very Reverend W.R. Matthews published a comprehensive account titled St. Paul’s in Wartime published in 1946 (this article only scratched the surface of the work of the Watch. I recommend this book for a detailed and very readable account)

- St. Paul’s In War and Peace published by the Times Publishing Company in 1960

alondoninheritance.com

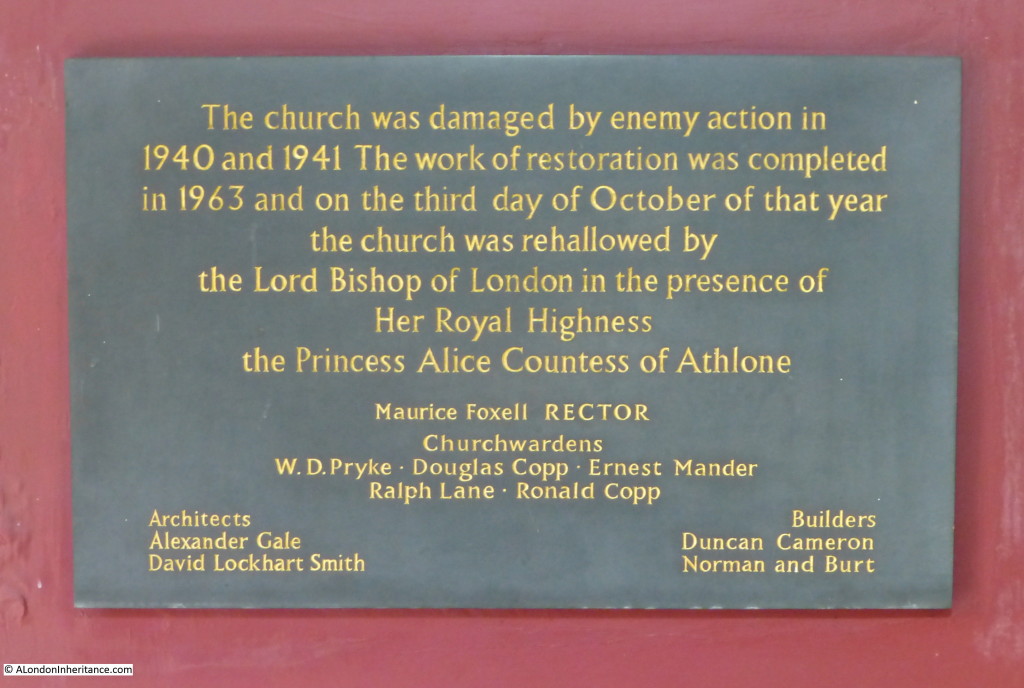

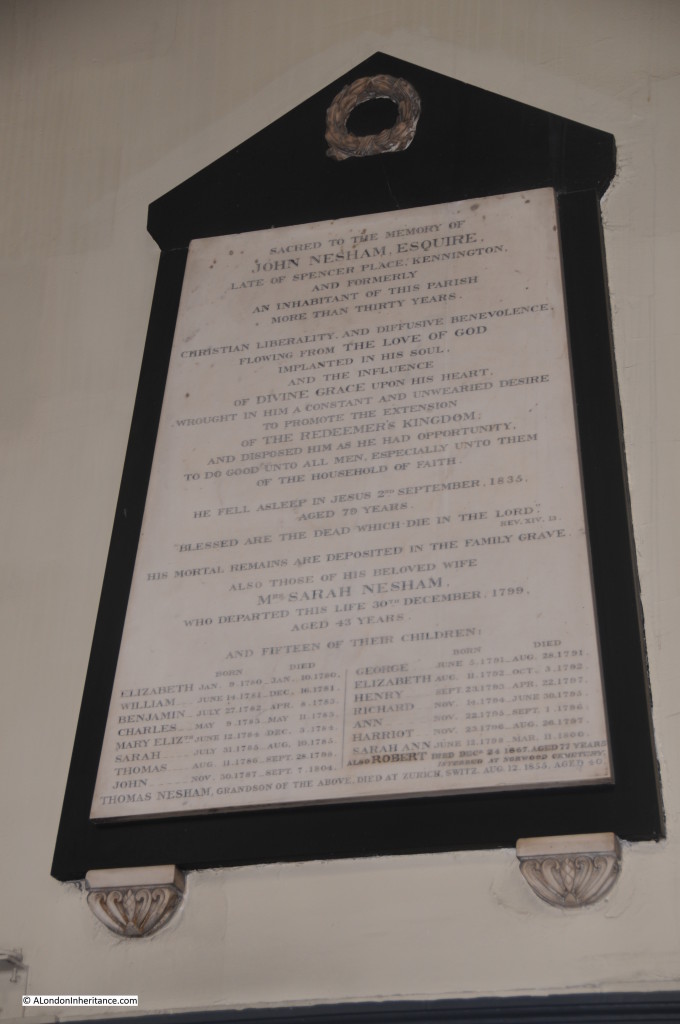

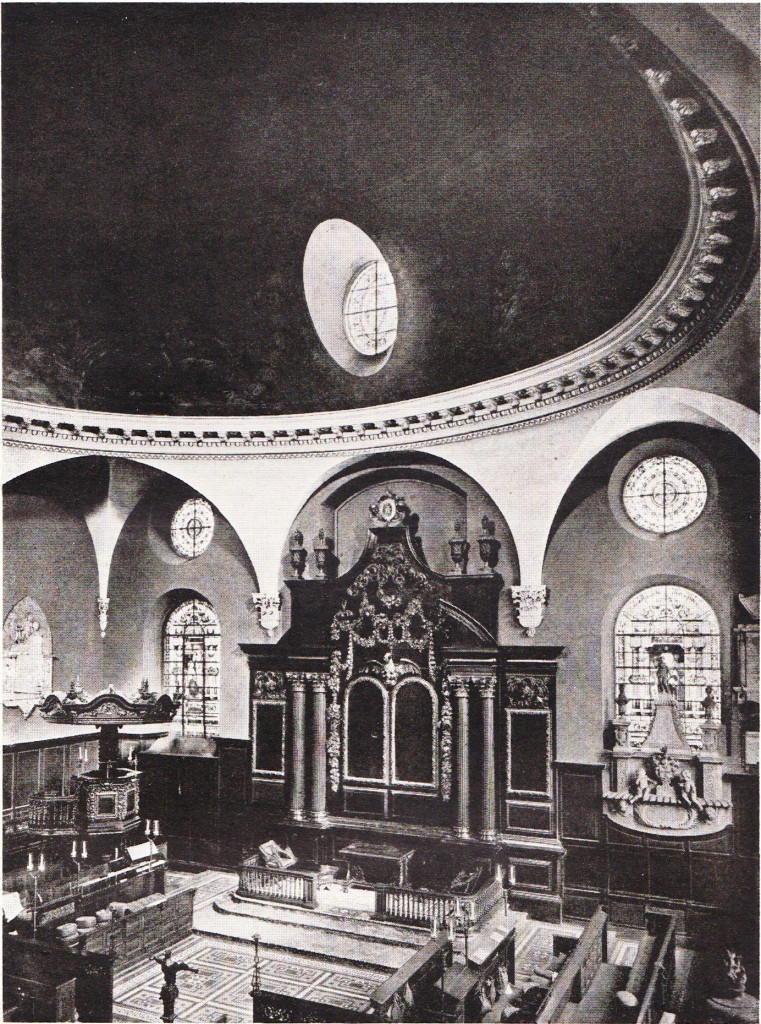

Again a surprise given the external appearance of the church from Lovat lane.

Again a surprise given the external appearance of the church from Lovat lane. The organ was restored following the fire of 1988 and rededicated in 2002.

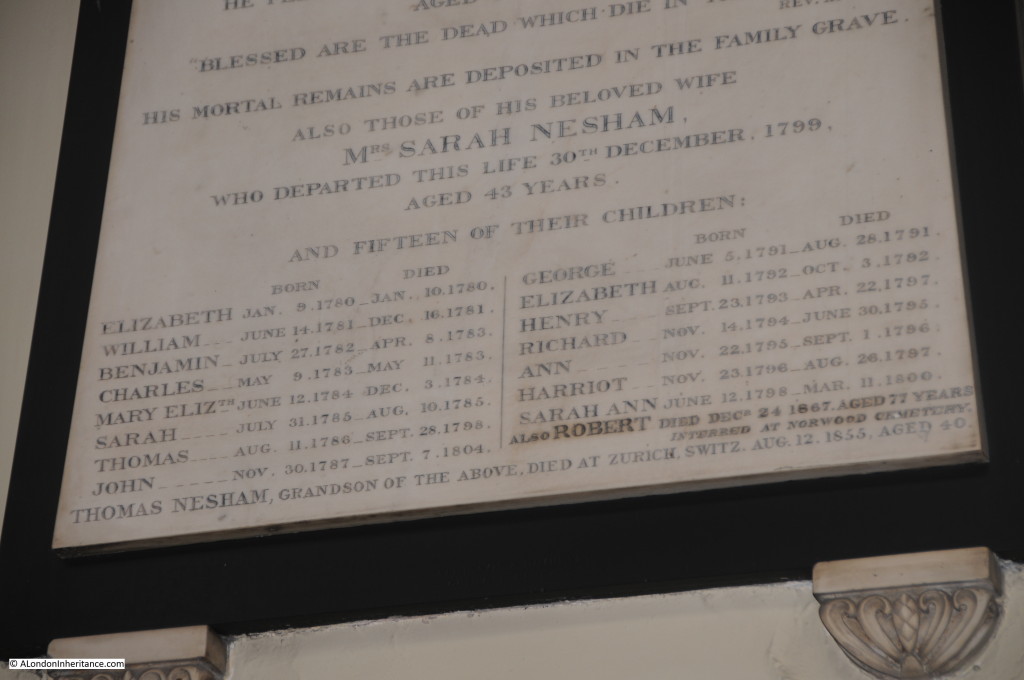

The organ was restored following the fire of 1988 and rededicated in 2002. A plaque on the wall informs us that “the burial ground of the parish church of St. Mary-at-Hill has been closed by order of the respective vestries of the united parishes of St. Mary-at-Hill and Saint Andrew Hubbard with the consent of the rector and that no further interments are allowed therein – Dated this 21st day of June 1846.” Following closure, all human remains from the churchyard, vaults and crypts were removed and reburied in West Norwood cemetery.

A plaque on the wall informs us that “the burial ground of the parish church of St. Mary-at-Hill has been closed by order of the respective vestries of the united parishes of St. Mary-at-Hill and Saint Andrew Hubbard with the consent of the rector and that no further interments are allowed therein – Dated this 21st day of June 1846.” Following closure, all human remains from the churchyard, vaults and crypts were removed and reburied in West Norwood cemetery. The reference to St Andrew Hubbard is an example of the consolidation of parishes after the 1666 Great Fire, The church of St Andrew Hubbard was not rebuilt and the parish integrated with that of St. Mary at Hill.

The reference to St Andrew Hubbard is an example of the consolidation of parishes after the 1666 Great Fire, The church of St Andrew Hubbard was not rebuilt and the parish integrated with that of St. Mary at Hill.