I was recently scanning some negatives of photos I had taken in London in 1982 and found a series of photos of archaeological excavations around St. Peter’s Hill and Upper Thames Street, all in the region of the church of St. Benet which I covered in a post a couple of weeks ago.

In the early 1980s a site was needed to relocate the City of London School and the site chosen was adjacent to St. Benet and unusually across the new routing of Upper Thames Street which was in the process of being boxed into a tunnel and onto the embankment of the Thames with space left for a new Thames Path.

As well as the foundations of the Victorian warehouses that ran along this part of the river and an enormous range of finds from the 1st to the 18th centuries, the excavations found two significant finds:

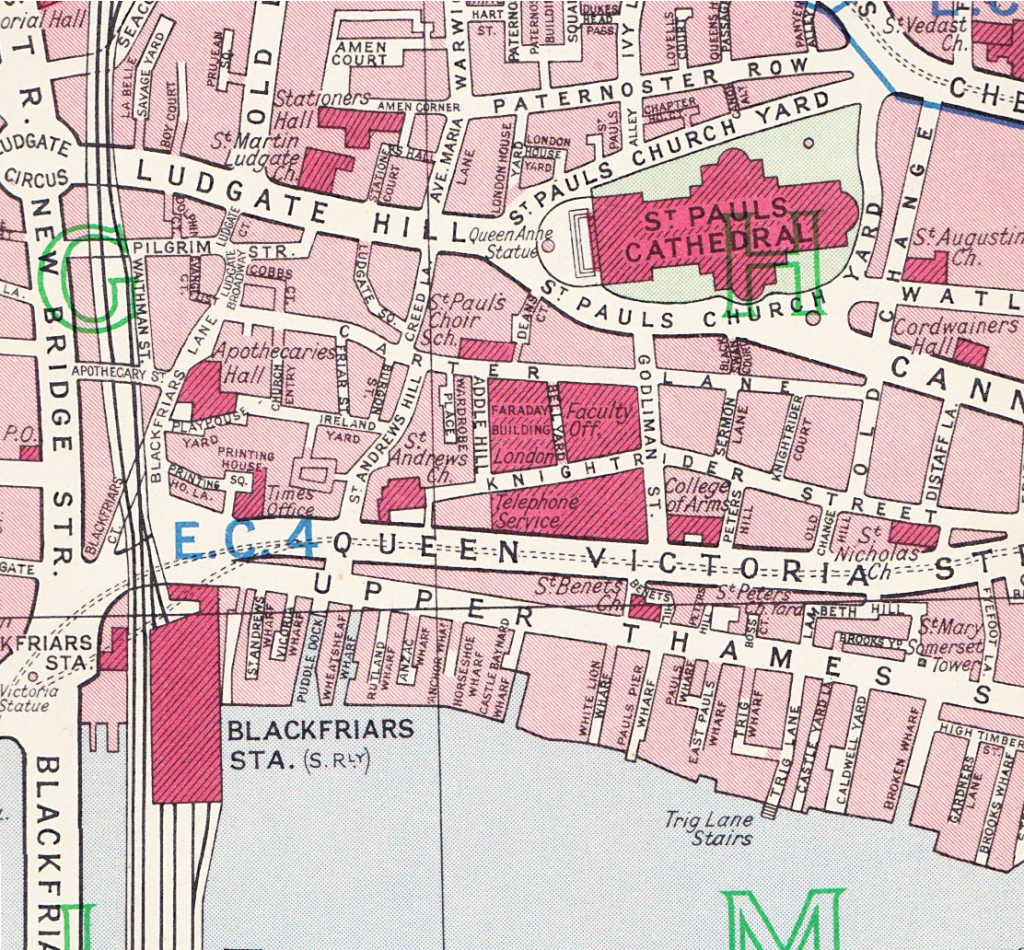

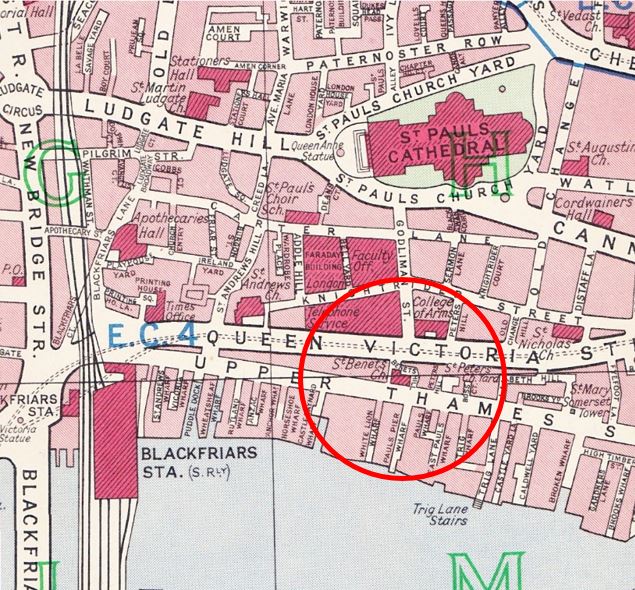

- A corner of Baynards Castle

- The foundations for a significant Roman monument

But before discussing these finds, let’s start with a view of the area facing the Thames.

I took the following photo standing on the new White Lion Hill, looking along the area that had already been cleared ready for construction of the City of London School. The concrete tunnel on the left is the new routing of Upper Thames Street, the school will soon be built over this tunnel.

An interesting feature of this photo is the crane at the far end of the cleared area. This was the last working crane in the City and operated by the company LEP (Lanstaff, Ehremberg and Pollak) who ran their Transport and Depository business from the white building behind the crane which was LEP’s Sunlight Wharf building, which would soon be demolished in 1986. the crane was dismantled earlier in January 1983.

The Sunlight Wharf building was originally constructed on an area owned by and for Lever Brothers (now Unilever). Plans for the new warehouse were submitted in 1903 and the warehouse was completed in 1906.

Sunlight Wharf specialised in the unloading and storage of furs, silk and tinned fruit. Sunlight Wharf also carried on the tradition of this small area of being the landing point for stone destined for St. Paul’s Cathedral. The original landing point used by Wren during the construction of St. Paul’s was the adjacent Paul’s Wharf. During later repairs to the cathedral, Sunlight Wharf was used with one of the last sailing barges to carry stone to central London arriving at Sunlight Wharf in August 1927 after a five day voyage from Dorset carrying a cargo of 50 tons of Portland stone,

Before the war there were four swinging cranes along Sunlight Wharf. After the war as the number of barges decreased, these were replaced by the crane in the photo which was a ten ton Butters crane, able to lift a larger load and place this directly onto a waiting vehicle. A clear sign of why the docks in central London were not able to continue in business.

Although the Millennium Bridge which is now adjacent to where this building stood is a relatively recent construction, plans for a bridge between Southwark and St. Paul’s stretch back to 1851 and almost came to be built following the Bridges Bill of 1911. Needless to say, the occupiers of the area including Lever Brothers strongly opposed the building of the bridge. An architectural competition was held in 1914, but the outbreak of the first world war prevented any further progress and immediate plans for the bridge came to an end.

At the bottom of the above photo can be seen a fence. Looking down into this fenced off area we can see the base of the 15th century tower at the south east corner of Baynard’s Castle.

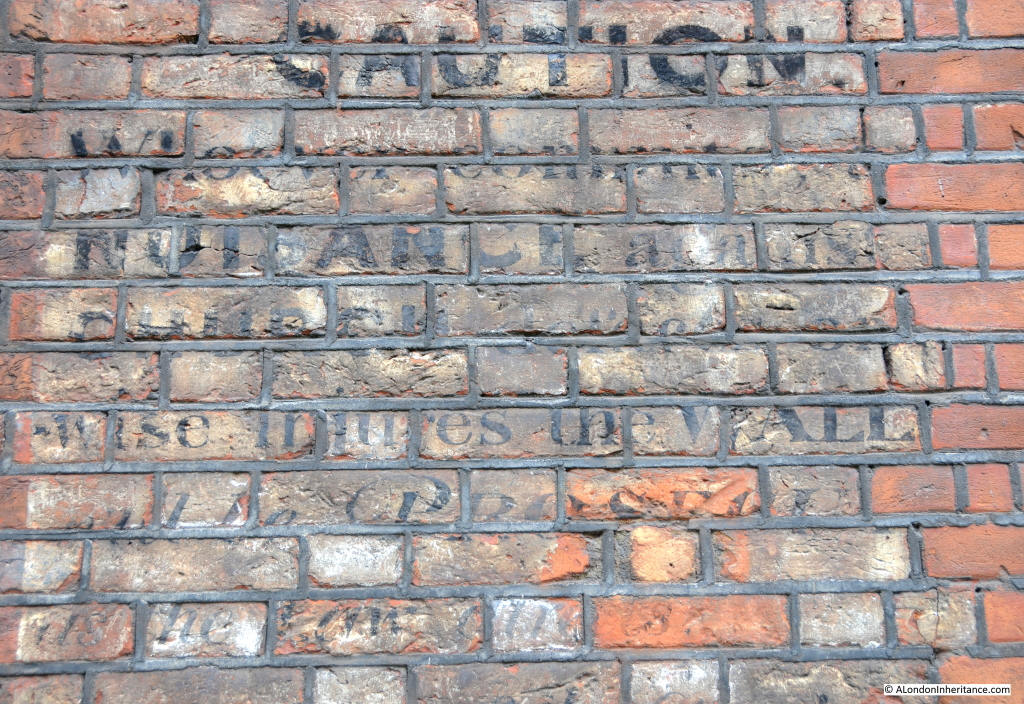

Note the no expense spared sign to inform onlookers:

The original Baynard’s Castle was built just after the Norman conquest and takes it’s name from Ralph Baynard who came over with William the Conqueror. Baynard’s being the castle at the west end of the City with the Tower of London at the east end.

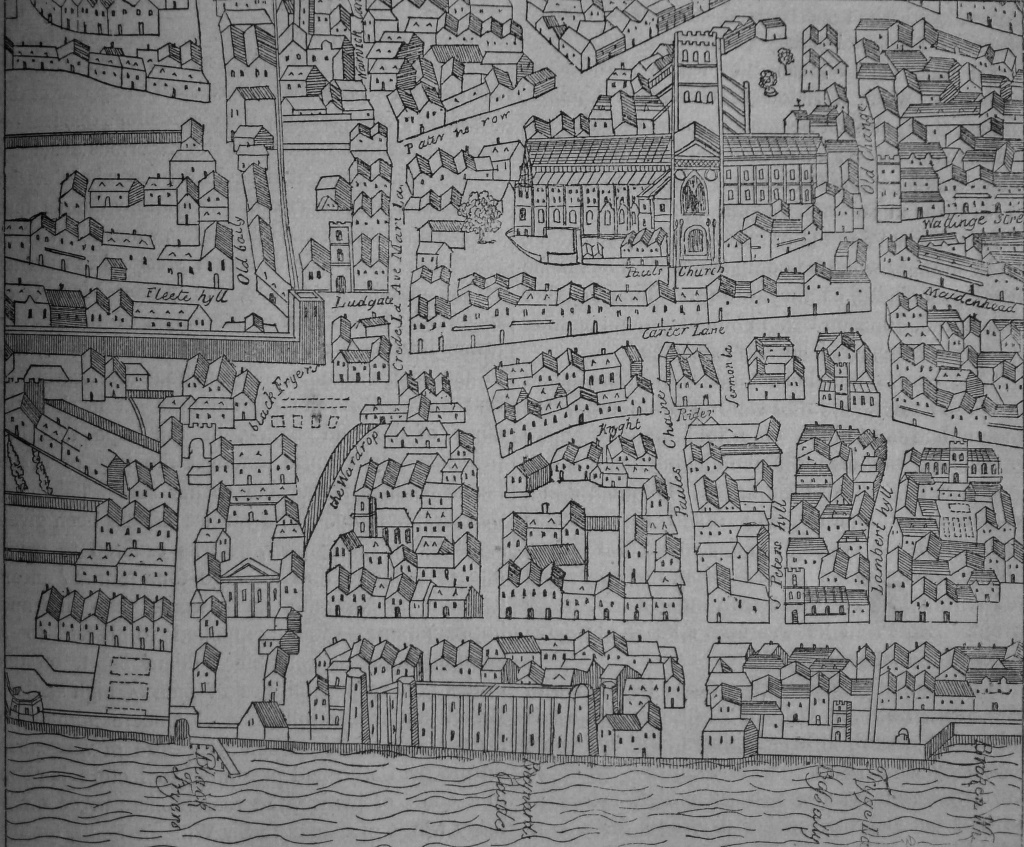

The excavated tower is the east end of the castle which extended back along the Thames river front towards Puddle Dock. The following extract from Agas’ Plan of London from 1563 shows Baynard’s Castle at the centre of the frontage along the Thames.

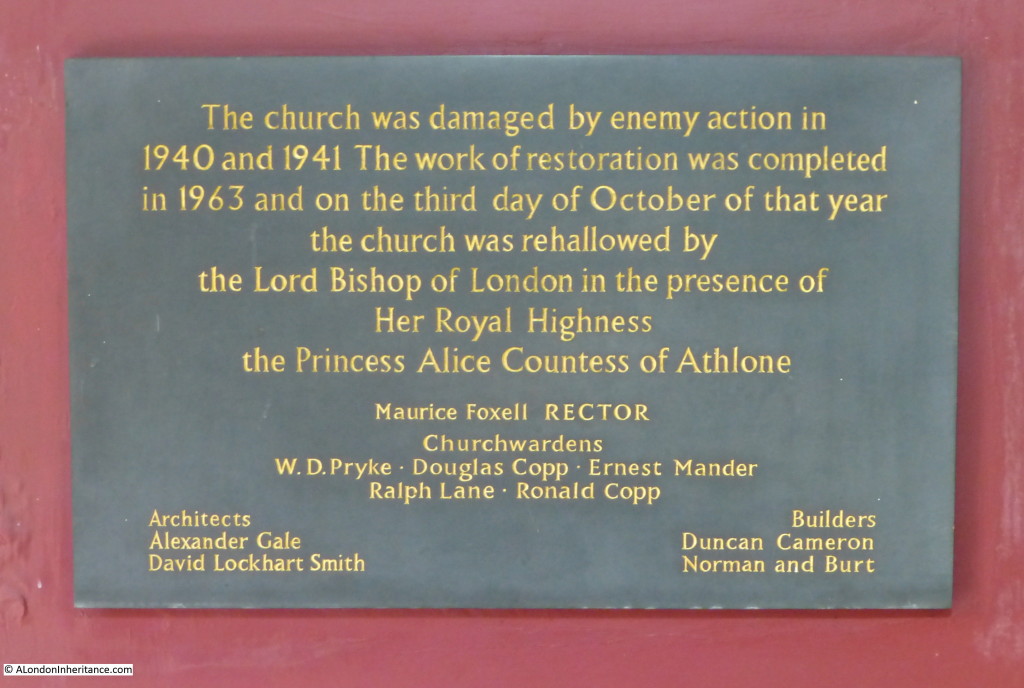

The original castle burnt down in 1428 and was rebuilt by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and it is these foundations that were discovered in 1982. After Humphrey’s death, the castle passed to the crown and was made a royal residence by Henry VI.

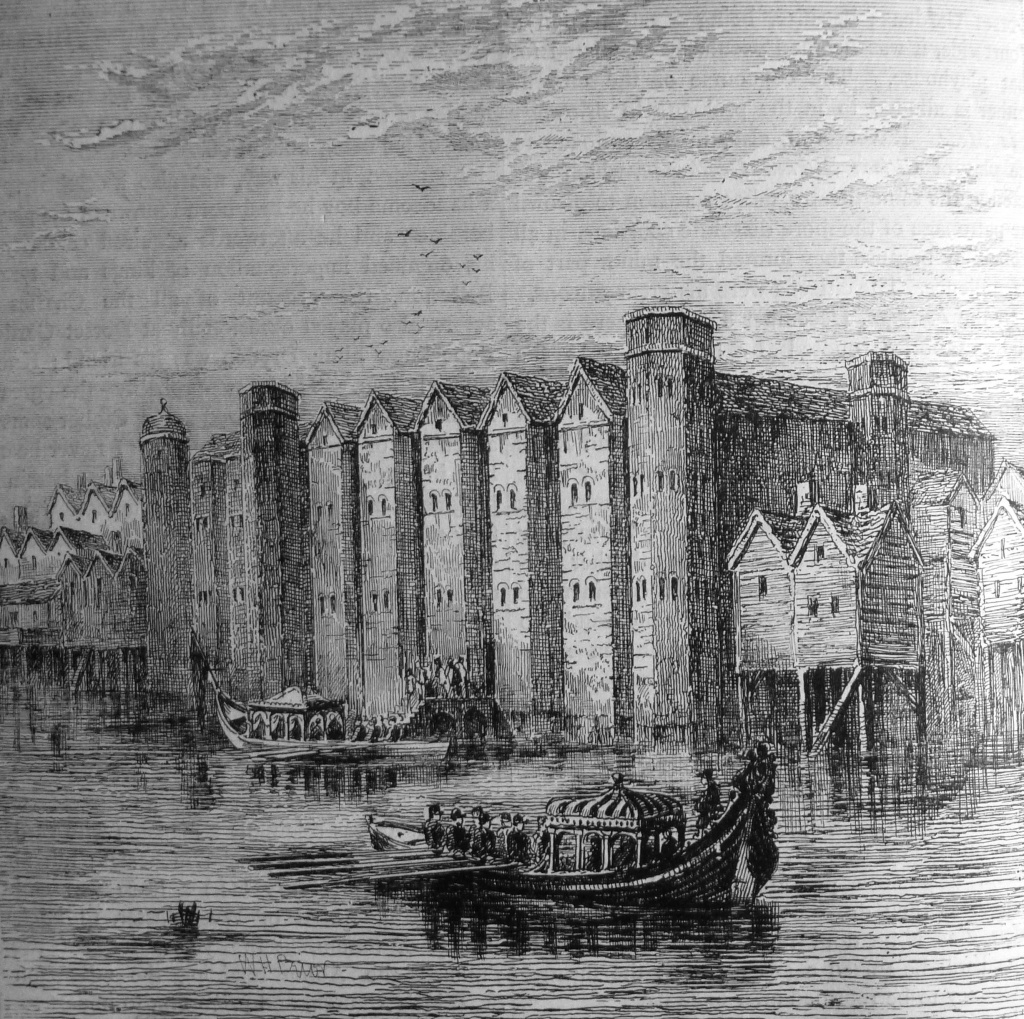

The following gives an impression of the appearance of Baynard’s Castle.

Henry VIII spent a large sum to turn the castle from a fortress into a palace, and after Henry’s death it was in Baynard’s Castle that the council was held which confirmed that Mary would be Queen of England, for her short lived and generally unpopular reign from 1553 to 1558.

Queen Elizabeth I occasionally used the castle, but royal usage declined and the castle was taken on by the Earls of Shrewsbury until the castle became one of the casualties of the Great Fire.

The area of the photo is now fully occupied by the City of London School. I walked along White Lion Hill to try and take a photo from the same position, but all you would see is the wall of the school. The Millennium Bridge is the best vantage point for a view of this area now. I took the following photo which is looking from the bridge (at the far end of the original photo) towards White Lion Hill which is at the far left of the photo. The school, along with the Thames Path occupies the area at the front of my original photo and continues back over the Upper Thames Street tunnel.

Now let’s move back up to Queen Victoria Street to the area now occupied by the school, adjacent to St. Benet’s. In 1982 I took the following photo from Queen Victoria Street overlooking the excavations towards the corner of St. Benet’s. The other side of the Upper Thames Street tunnel to that shown in the previous photo can be seen.

I could not take a photo of this area from the same position as it would be looking straight into the walls of the school. The following photo is my 2014 photo from Queen Victoria Street which shows the school to the left and is looking towards the church. The black and white posts in the 2014 photo are along the same line as the fencing on the right of the above photo which protected the site from St. Bennet’s Hill, the side street running past the church.

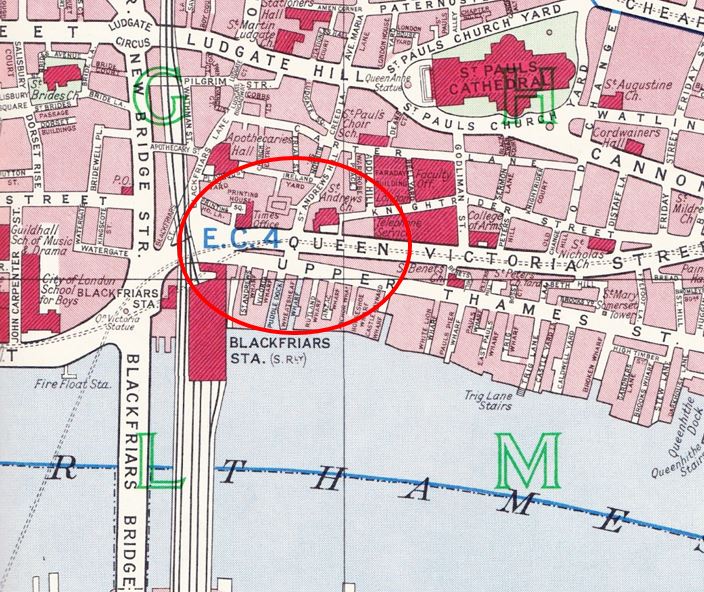

I have marked some of the features that can be seen in the following photo. Upper Thames Street originally ran directly past the church. The redevelopment seen in these photos relocated this street slightly to the south, closer to the river. The original route of Upper Thames Street is marked in yellow in the photo below.

The majority of the foundations that can be seen in this photo are of the Victorian Warehouses that covered this area (see my post on St. Benet’s to see a photo of this area as it was), however what excited much interest during this excavation was the find of a large monumental base from the Roman period. This is highlighted in blue in the following photo.

There was not that much Roman activity in this area in the 1st and 2nd centuries as the area was at the far south west of the main Roman settlement. This area was at the bottom of a hillside extending back up away from the river, with terraces being cut into this hill. The monumental base was found on the lowest terrace and was of limestone blocks and ragstone masonry and was built on a raft of oak piles and rammed chalk.

Although only a small part can be seen in the above photo, the actual size of these foundations extended 4m along the western edge and possibly 8 meters along the southern edge. What was built on these foundations was not clear. Other excavations produced evidence of what could have been a temple in the area. A Roman altar was found rebuilt into a wall at Blackfriars and fragments of a monumental archway and a Screen of Gods were found in the riverside wall a short distance to the west, so it may have been possible that a temple was built on these foundations facing the river and being cut back into the hillside. These were dated from the third century.

There is also evidence that Upper Thames Street in it’s original route prior to the 1980s redevelopment had strong connections with remaining Roman structures. It may have been possible that the southern terrace constructed in the Roman period was still visible in the 11th Century when development of this area started to get underway again. St. Benet’s being one example of this as the first mention of the church is from the year 1111, when it was built up against the original Upper Thames Street. Reference is made to a wall next to the river at the end of the ninth century when King Alfred made two grants of property to the Bishops of Worcester and Canterbury with the wall being described as the southern boundary of the property.

The following photo gives another view of the site with the monumental base in the centre foreground with the two planks meeting on the top of the base.

And in the following photo we can just see the end of the monumental base with some of the blocks which were dislodged by robbing when much of the stonework was removed for reuse in building work (just above the three planks).

The following photo gives some idea of the depth of excavations. After the Great Fire large quantities of fire debris were dumped over this area which had the effect of raising the area by 2 to 3 metres.

The following photo gives some idea of the depth of excavations. After the Great Fire large quantities of fire debris were dumped over this area which had the effect of raising the area by 2 to 3 metres.

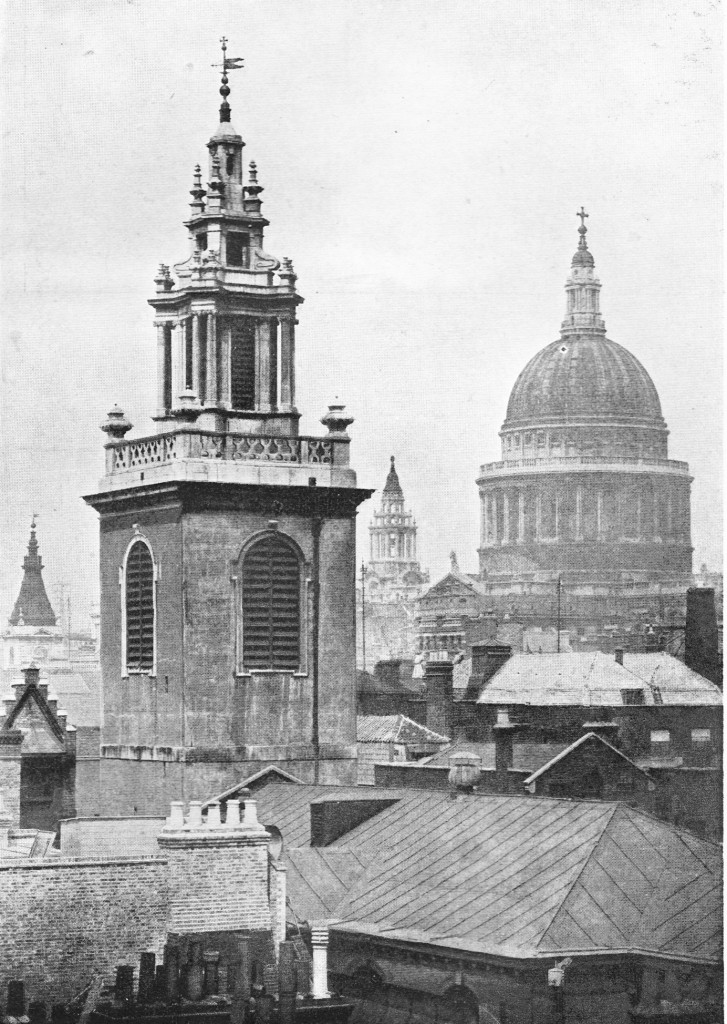

I took the photo looking down towards the Baynard’s Castle tower foundations from White Lion Hill. I also took the following photo from the same position on this road looking back up towards St. Benet’s and St. Paul’s.

And in 2014 from exactly the same point. The big difference again being the school which now occupies the whole area to the right.

Although small, this is a fascinating area of London and demonstrates the multi-dimensional aspect of London which I find so interesting. In this post I have covered the site of today, along with early Roman foundations and the later medieval castle. If you refer to my post of a couple of weeks ago which can be found here you can also see the streets that once ran across this site and one of my father’s photos showing the original warehouses before demolition.

Although small, this is a fascinating area of London and demonstrates the multi-dimensional aspect of London which I find so interesting. In this post I have covered the site of today, along with early Roman foundations and the later medieval castle. If you refer to my post of a couple of weeks ago which can be found here you can also see the streets that once ran across this site and one of my father’s photos showing the original warehouses before demolition.

The London we see today is just one instance of the City. Standing in the same position, there are many different going back for two thousand years and occasionally we can catch a glimpse of what the City looked like at a specific time.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- St. Paul’s Vista (A history commissioned by the Lep Group plc to mark the redevelopment of the Sunlight Wharf site) by Penelope Hunting published 1988

- Popular Archaeology magazine July 1982

- London by George H. Cunningham published 1927

- Old & New London by Edward Walford published 1878

- Stow’s Survey of London. Oxford 1908 reprint

- Bartholomew’s Reference Atlas of Greater London published 1940