If you would like to come on my Limehouse walk, I have just had a couple of tickets come available. Two tickets on Saturday 19th of August, and one ticket on Sunday 20th of August. All other walks are fully booked.

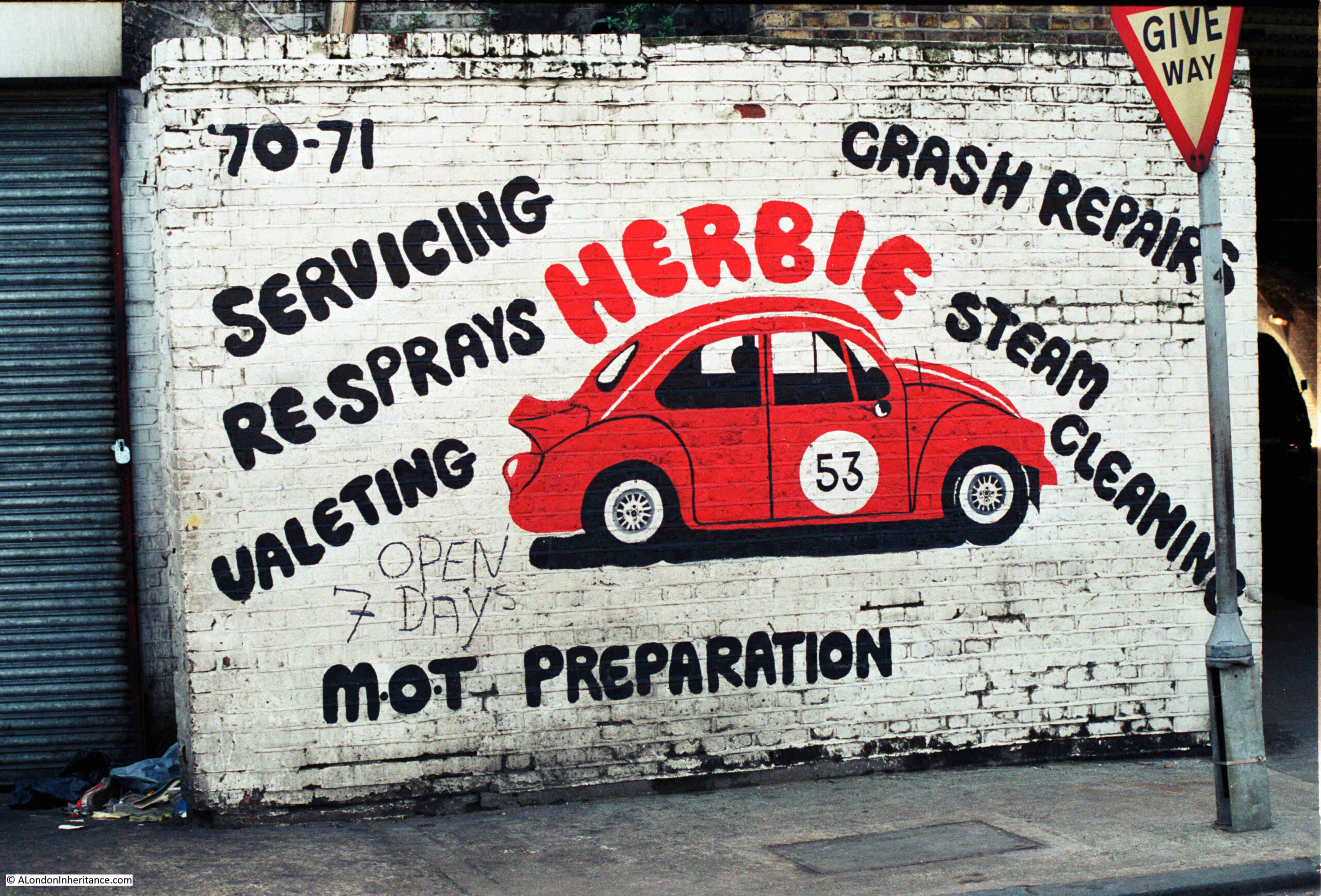

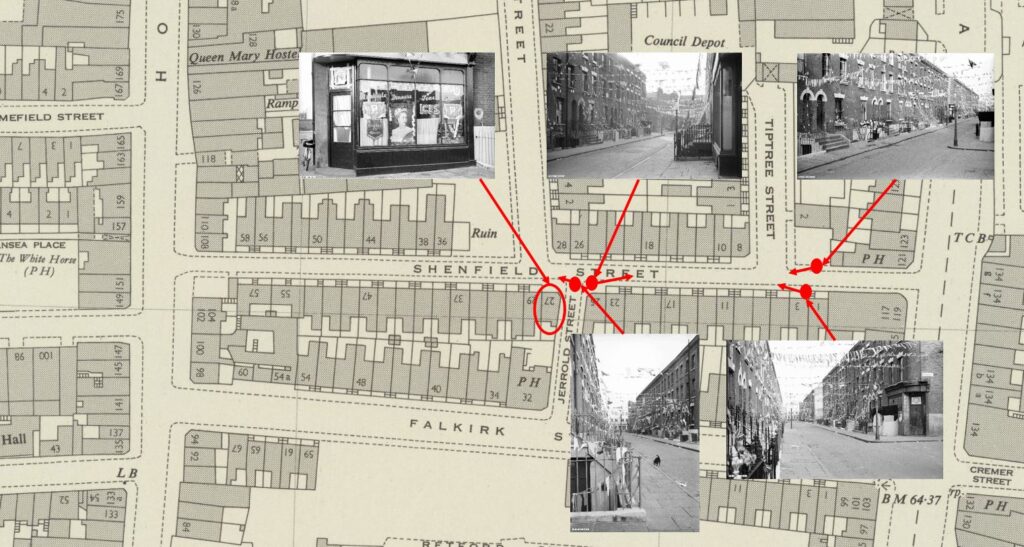

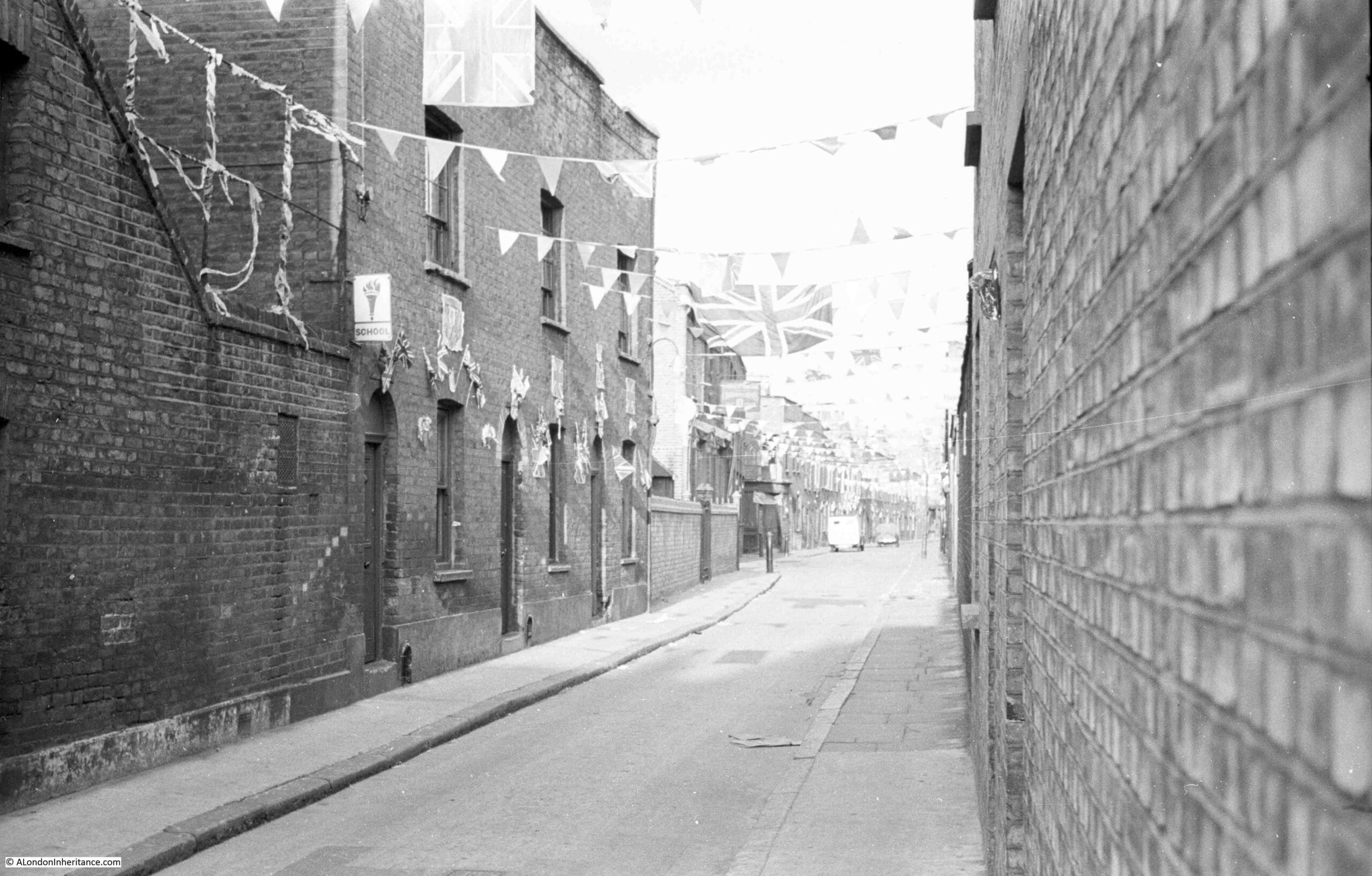

I was unsure about using this 1980s photo as the subject of a blog post, as there did not seem anything of specific interest in the view. The photo was taken at the junction of Bethnal Green Road (not visible, but to the left) and Redchurch Street, the street on the right:

I assume the two old columns were the reason my father took the photos. Rather than lighting columns, I believe these are ventilation columns for the toilets below ground:

The following photo is looking over to the location of the toilets, some forty years later in 2023. The toilets have gone, one of the columns remains, and a rather strange building now stands over the site of the toilets.

The column appears to be the one that was at the rear of the original photos, and has been relocated to the corner of the junction.

Bethnal Green Road is to the left and Redchurch Street is to the right.

Taking a look inside the building over the site of the toilets, and if you look at the far end to the right, it is hard to see, but there is a descent down to below ground level, a handrail on the left and a sloping ceiling. This was presumably the stairs down to the toilet area below.

And to the side of the building are the glass tiles which cover much of the area in the 1980s photos, and originally provided light to the space below, which I assume they still do.

The toilets in the 1980s photo were typical of the underground toilets found at many locations across London. They were built around the end of the 19th and start of the 20th centuries and were part of the late Victorian drive to improve the city.

They have now nearly all closed. The demands on local authority budgets have meant that facilities such as these, which are not part of their legal responsibilities to provide, were among the first to go.

The one exception is the City of London, and although they have closed their old toilets, they have at least installed new facilities, or included them as a requirement of planning permission for new developments.

Many of these you have to pay to use, however the City does have a number of free to use toilets tucked away in places such as their car parks under London Wall, or at the Minories.

I have been photographing the above ground remnants of these rather enlightened improvements to the City, so perhaps a subject for a future post.

And that was as far as I thought I could go with the two 1980s photos, but as usual with any London scene, there is always something else to discover and learn, and so it is with these photos.

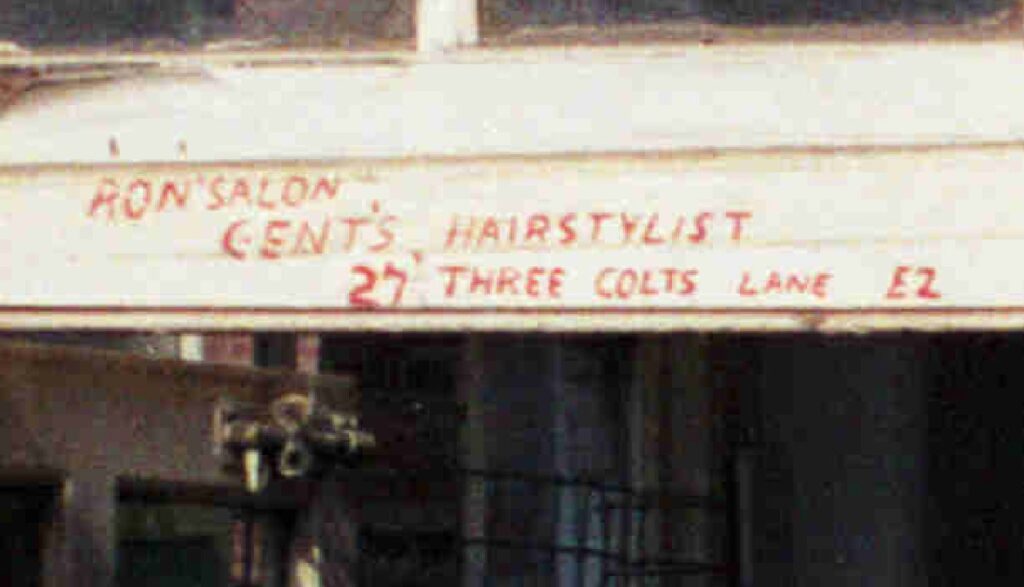

If you look along the street on the right in the first photo at the top of the post, there is a pub sign, with the ground floor of the pub just visible. This was the Dolphin pub, and I have enlarged the section showing the pub sign below:

The Dolphin closed in 2002, and the ground floor is now occupied by a Labour And Wait store, with the floors above presumably being used as residential.

The old pub as it appears in 2023:

There is not that much to discover about the Dolphin. It did not feature in many news reports, or place any adverts as to the excellence of their beers which was typical practice for most London pubs.

The one newsworthy event seems to have been a robbery in 1929, when a Henry Bently, 39, of Scalater Street in Bethnal Green, leant over the bar to take four £1 notes from the till. He was pursued by the landlord, he escaped, but later came forward as he appears to have been a regular at the pub, and therefore well known.

The interesting thing about the 1929 article was that the address was given as Church Street, rather than Redchurch Street as the street is now know, so I started to look at some maps.

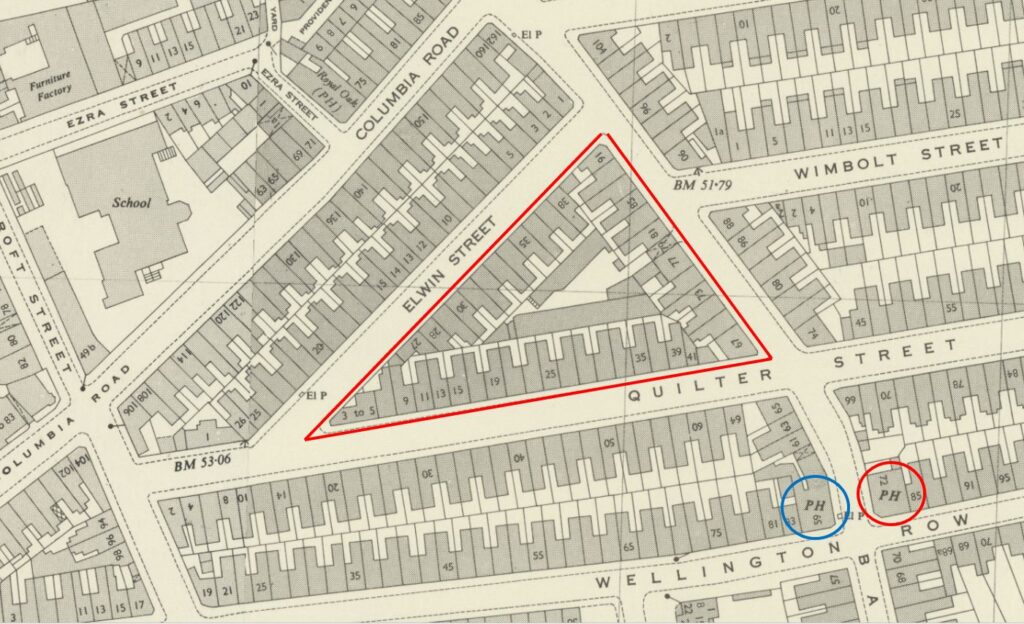

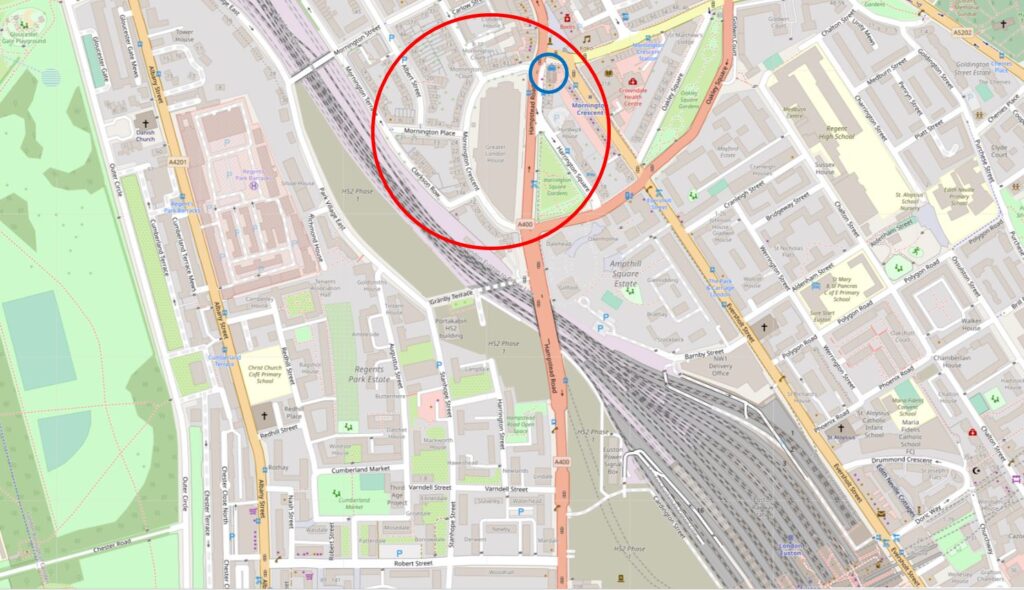

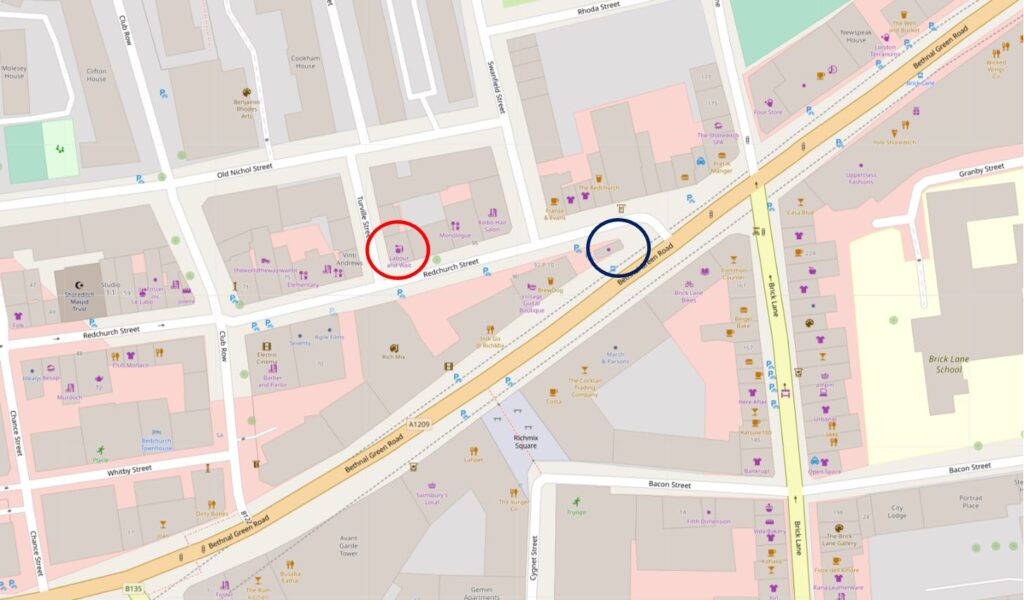

Firstly, the map of the area today, and in the following extract, the dark blue circle is around the space where the toilets were located, and you can see the main road of Bethnal Green Road heading south west, at this junction, with Redchurch Street turning off from Bethnal Green Road. The old Dolphin pub is marked by the red circle ( © OpenStreetMap contributors).

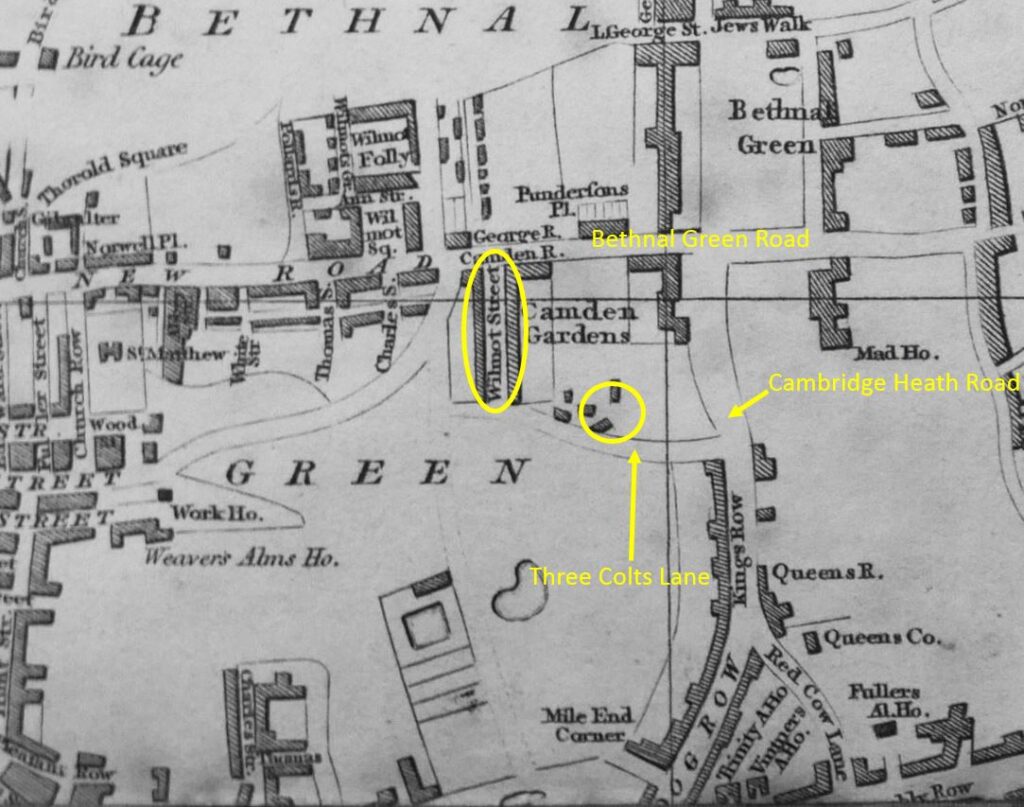

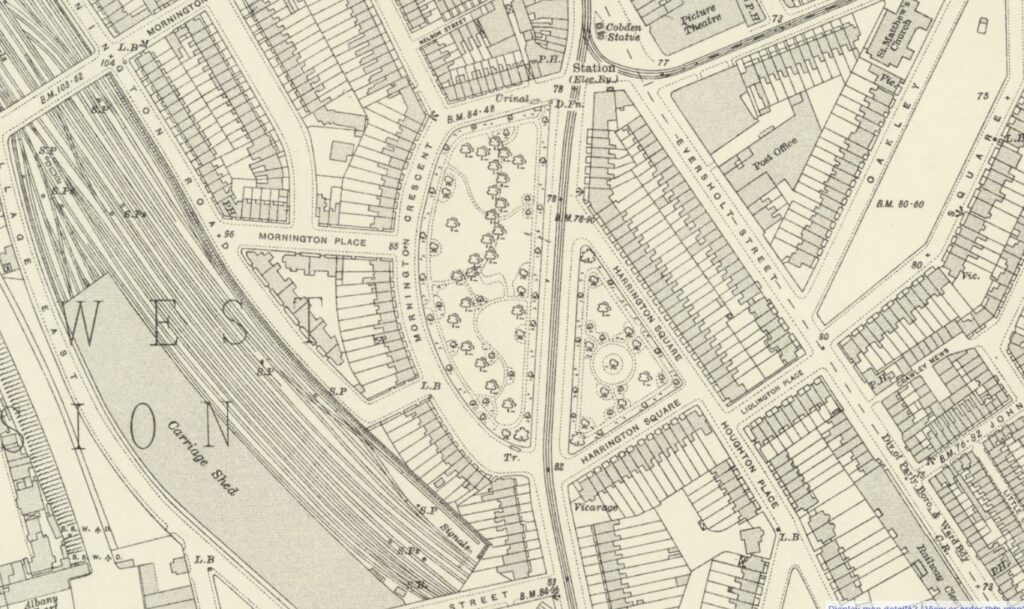

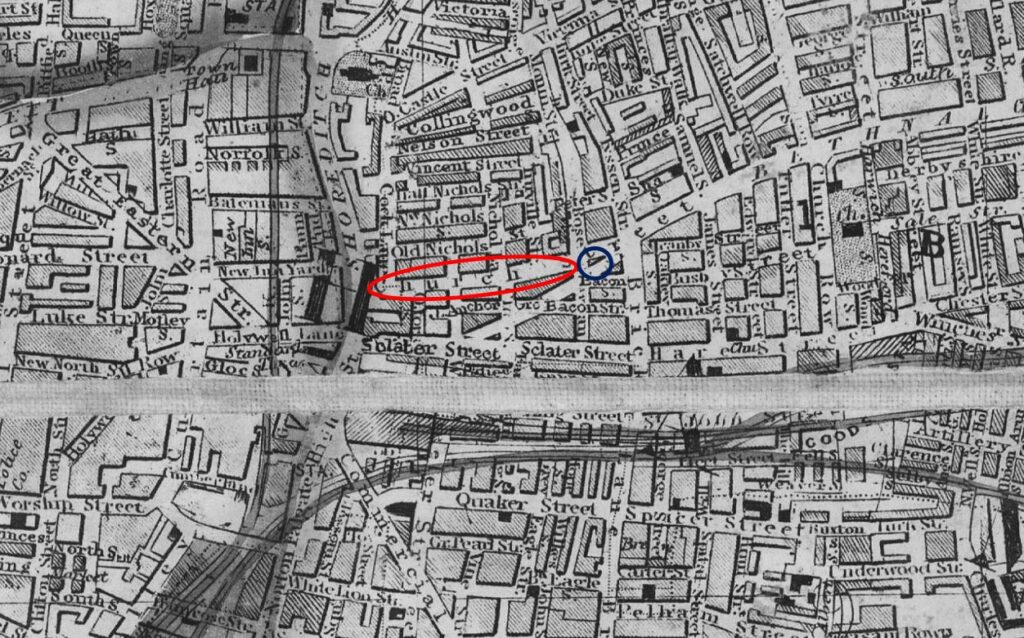

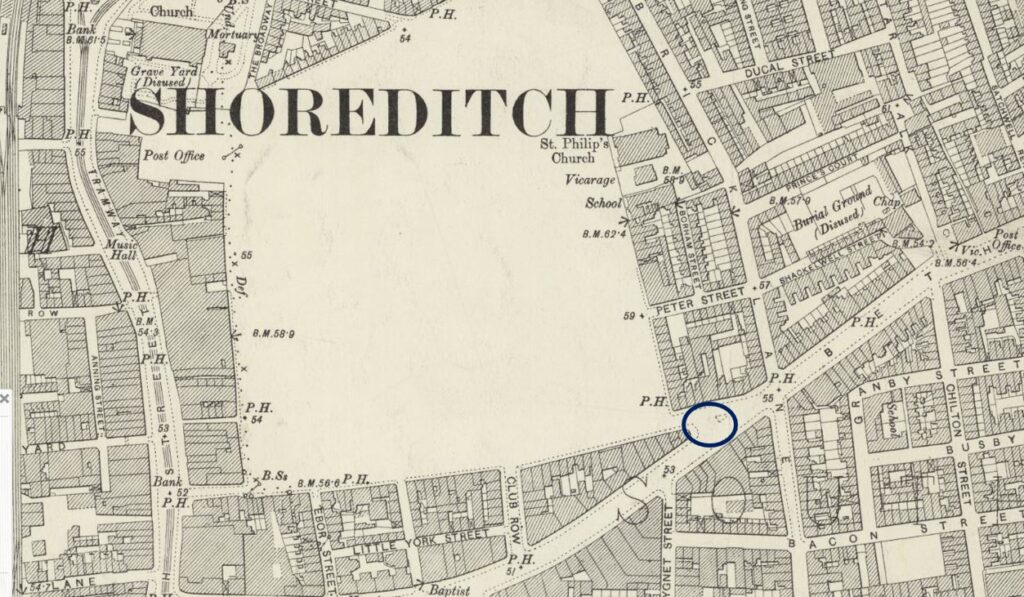

Looking at some older maps, starting with Smith’s New Plan of London from 1816, and I have again marked the location of the toilets with a blue circle, and Redchurch Street, then called Church Street is surrounded by the red oval:

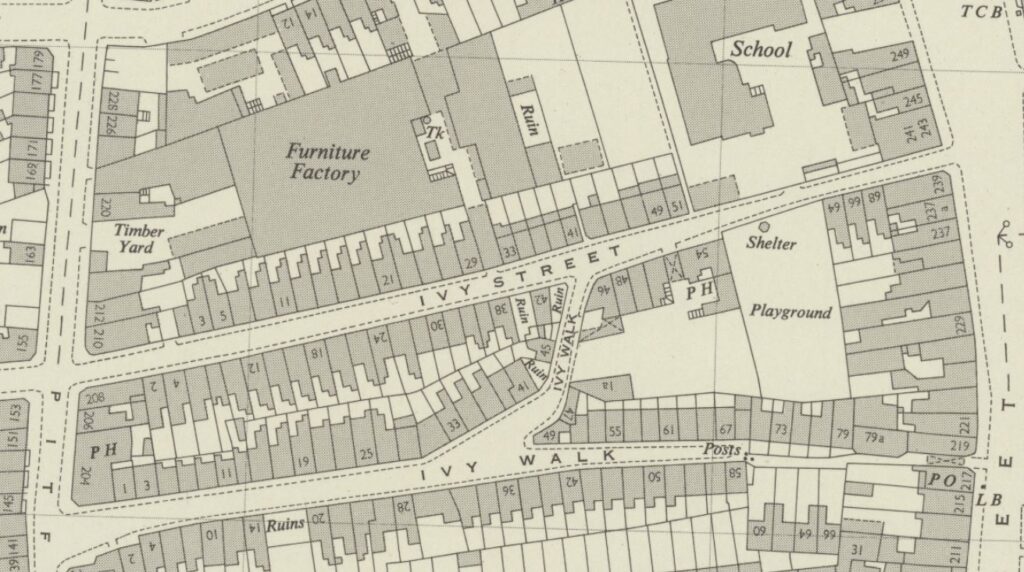

Look to the north of Church Street and you will see a dense area of streets and buildings, which looks different to the streets in the wider area.

Some of the street names should provide a clue as to the name and reputation of the area as this was the Old Nichol, a notorious area of densely populated streets and courts which was inhabited by some of the poorest people in east london.

The streets and buildings of the old Nichol were demolished in the 1890s and the Boundary Estate, which was built on the site, was opened in 1900. Newspaper reports of the opening described the old and new estates as follows:

“One most interesting feature of the Boundary Street Estate is that it has been built on the site of one of the most notorious slum districts in London. This was known as the ‘Old Nichol’, and is described minutely under the title of ‘The Jago’ by Mr. Arthur Morrison’s story ‘A Child of the Jago’.

A population of 6,004 persons were displaced under the Council’s scheme, and the slum clearance revealed a pitiful state of things. In two common lodging houses, 163 people were found to be living. 2,118 people were living in 752 single rooms, and 2,265 in 506 two-roomed tenements. The inhabitants consisted of the poorest classes of unskilled labourers, and in addition to large numbers of button makers, box-makers, charwomen, worker-women and so-called ‘dealers’, included some of the vilest characters in London.

In one small street alone there lived no fewer than twenty ticket-of-leave men. (see below for explanation) These people were transferred to other districts. Of the inhabitants of the ‘Old Nichol’, those who are new tenants on the Boundary Street Estate can be numbered on the fingers of one hand. The present occupants of the dwellings are mainly of the better classes, policemen, postmen, commissionaires, together with a few clergymen, schoolmasters, and Church workers”.

A ticket-of-leave man was a person who had been released from prison on parole, and the ticket-of-leave was the document handed to the person, documenting their status on parole.

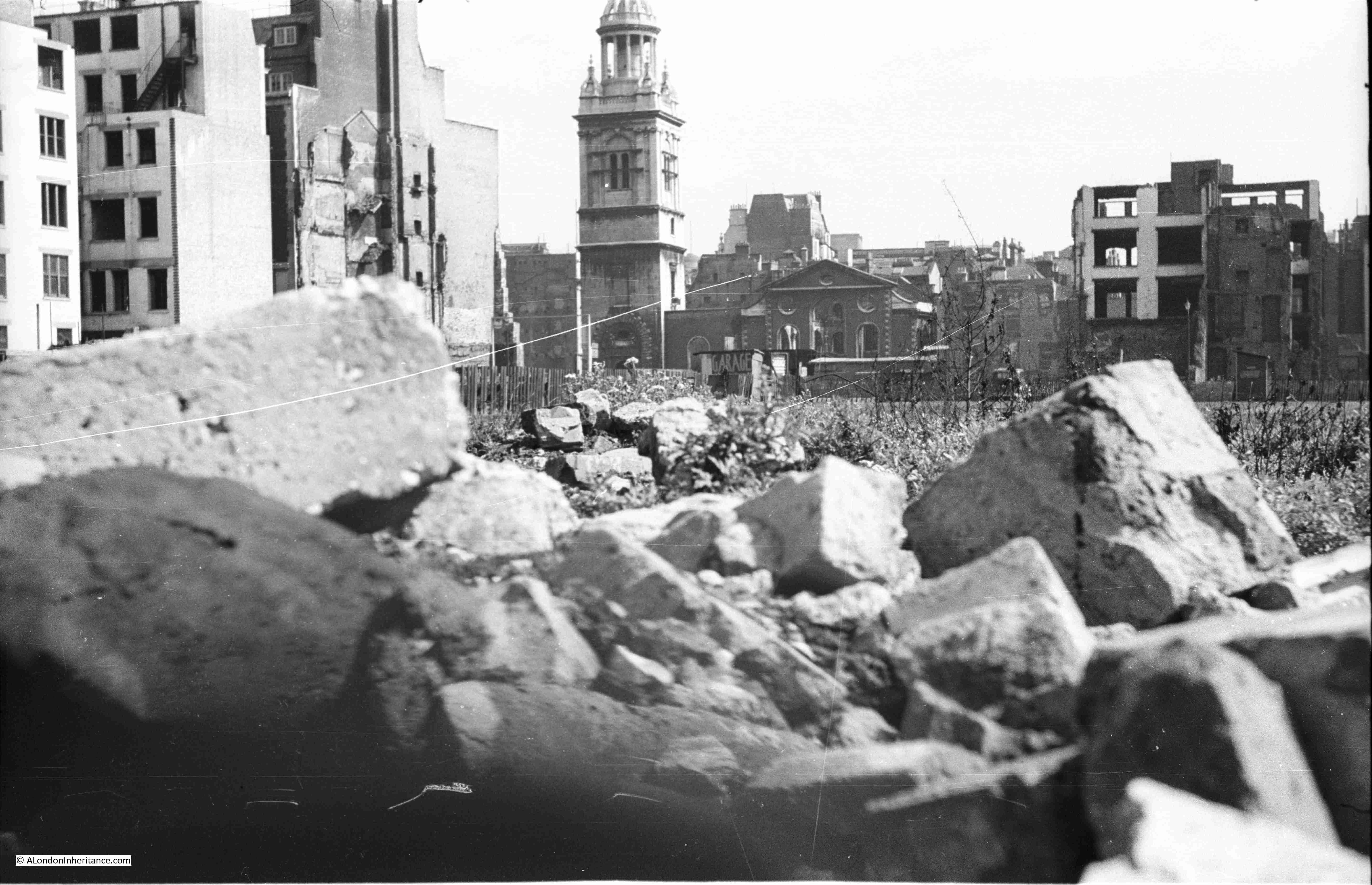

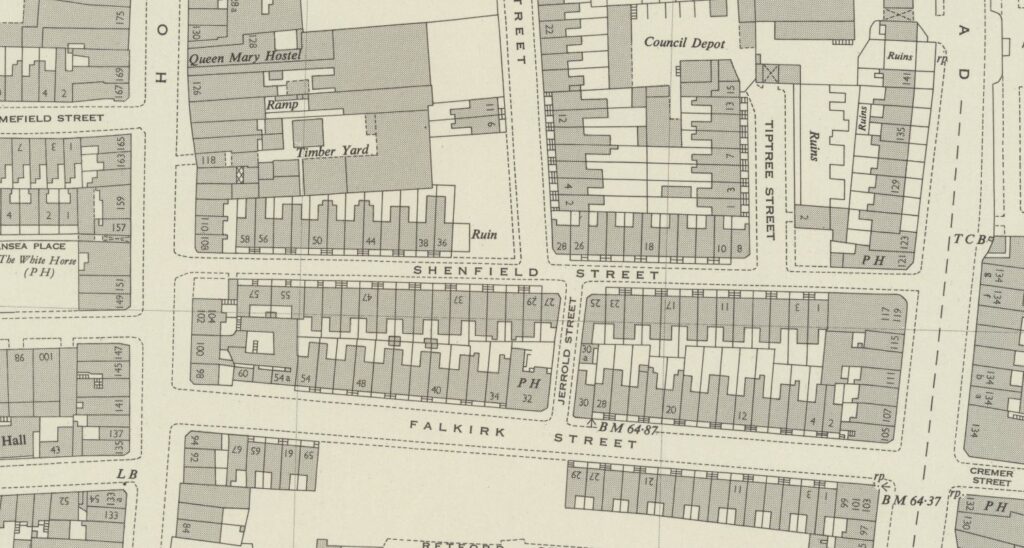

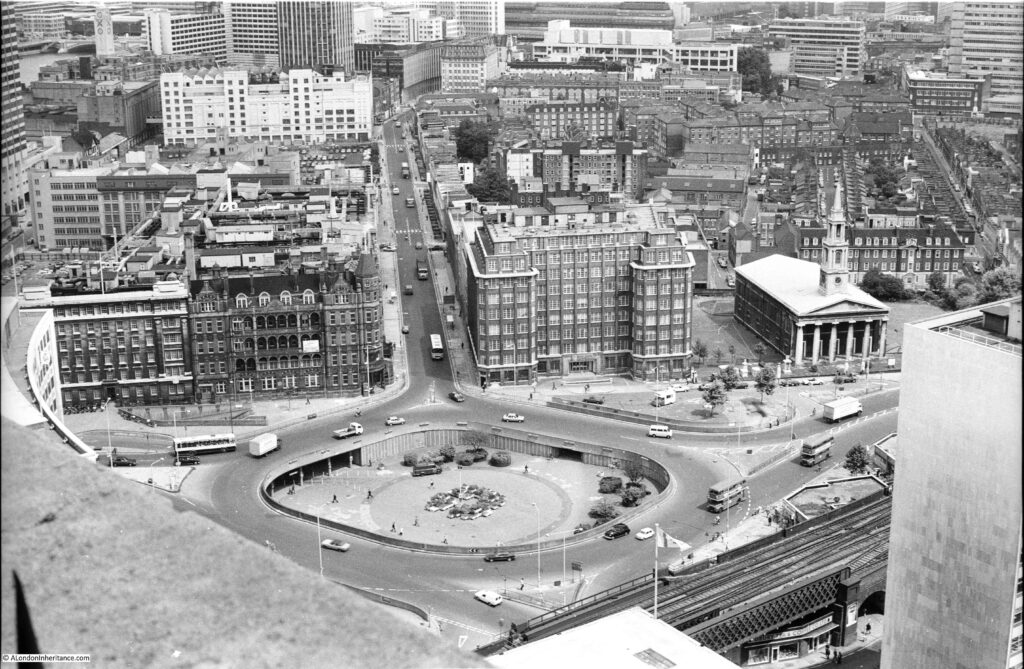

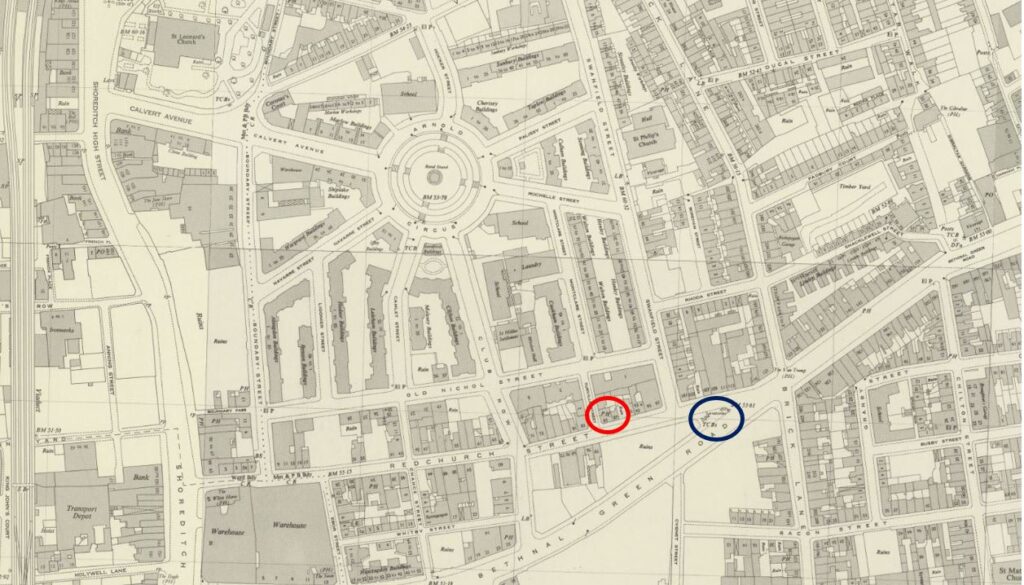

The Boundary Estate was opened by the Prince of Wales in March 1900, and we can jump forward to the 1948 revision of the OS map to see the new estate, with the central circular feature of Arnold Circus, with new streets radiating out from the circus (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“).

In the above map, I have again marked the location of the toilets by the blue circle, and the Dolphin pub by the red circle.

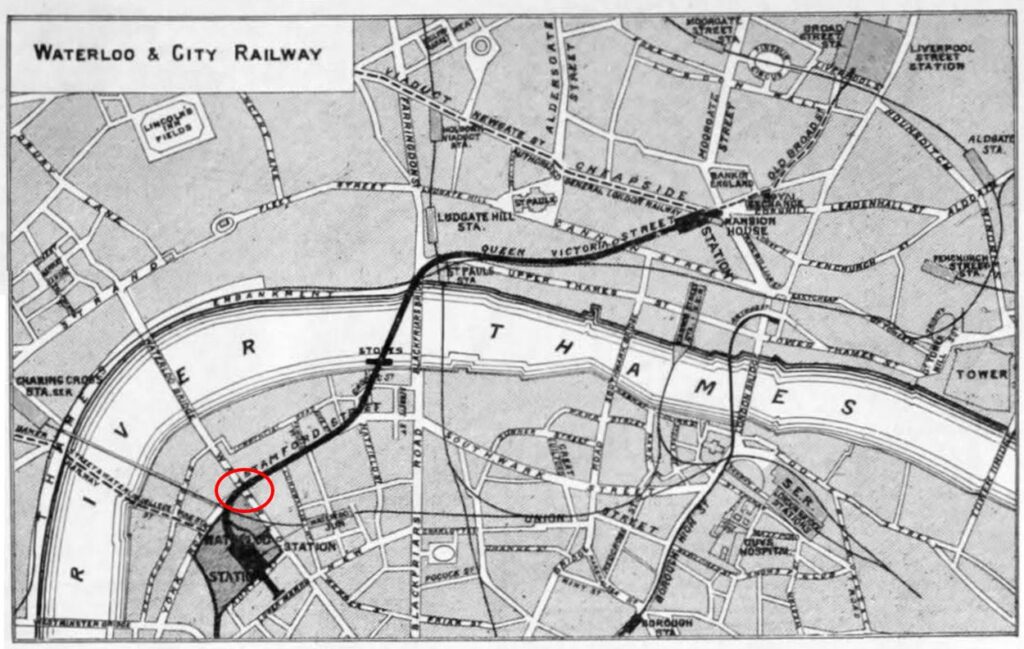

So far, so good, I then went to the 1898 revision of the OS map, which resulted in a bit of a mystery (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“).

In the above map, I have marked the location of the toilets with the blue circle, however to the left, the entire area north of Redchurch Street is shown as blank space, presumably the area demolished ready for the construction of the Boundary Estate.

The strange thing is that the Boundary Estate does not reach all the way down to Redchurch Street, and the Dolphin on the north side of the street had been built a few decades before the above map, and was still in use during the 1890s.

I checked the 1895 edition of the Post Office Directory, and it lists the Dolphin at number 85, along with a full range of businesses along the northern side of the street, including James Julier Fried Fish Shop at number 19, William Padley’s Dining Rooms at number 29, Nathan Bloom, Cabinet Maker at number 53 and Joseph Barker, Undertaker at number 71.

So the northern side of Church Street in 1895 had a full range of businesses, however in the OS map of three years later, the northern side of the street has disappeared, and is the lower boundary of the Old Nichol, that was in the process of being rebuilt as the Boundary Estate.

There were three years between the Post Office Directory and the OS map, and the streets on the northern side could have been demolished in those three years, however the Dolphin demonstrates this probably did not happen, and looking at the 1948 revision of the map shown above, the northern side of Church Street has the same layout of buildings as could be expected from the 1895 directory. It is very clearly not part of the Boundary Estate.

There is another PH for public house on the 1898 map on the north side of Church Street. This was the Black Dog pub, which although long closed, the original building can still be seen.

Whether the OS map shows a more extended area originally planned for rebuild, which was reduced during the development stage, or whether it was simply an error of mapping, it is unusual to find such a significant error in OS maps.

Redchurch Street / Church Street is a very old street. It is the core of the Redchurch Street Conservation Area as defined by the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. Their conservation area document also helps confirm that the northern side of the street was not demolished as part of the Boundary Street Estate.

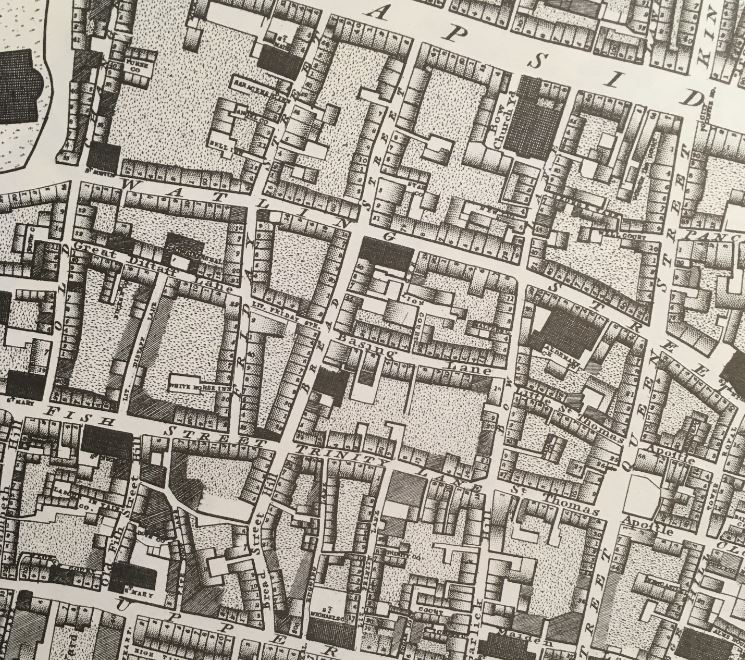

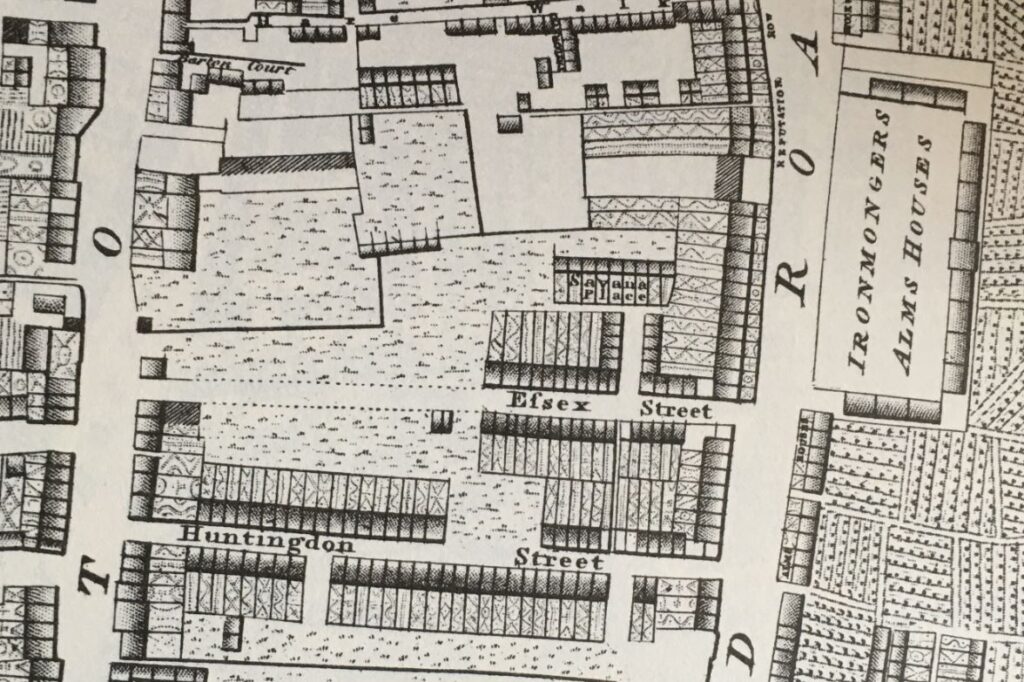

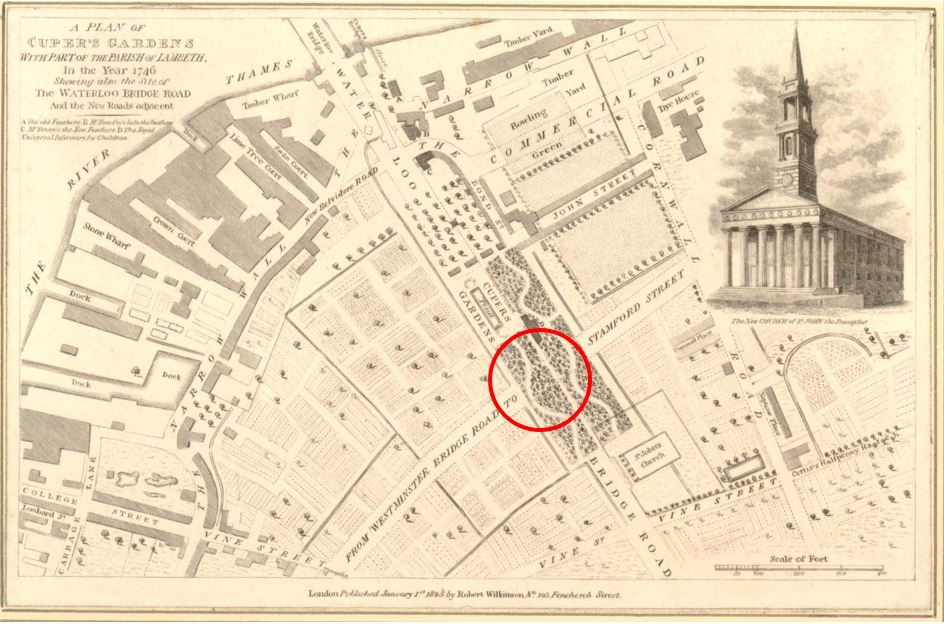

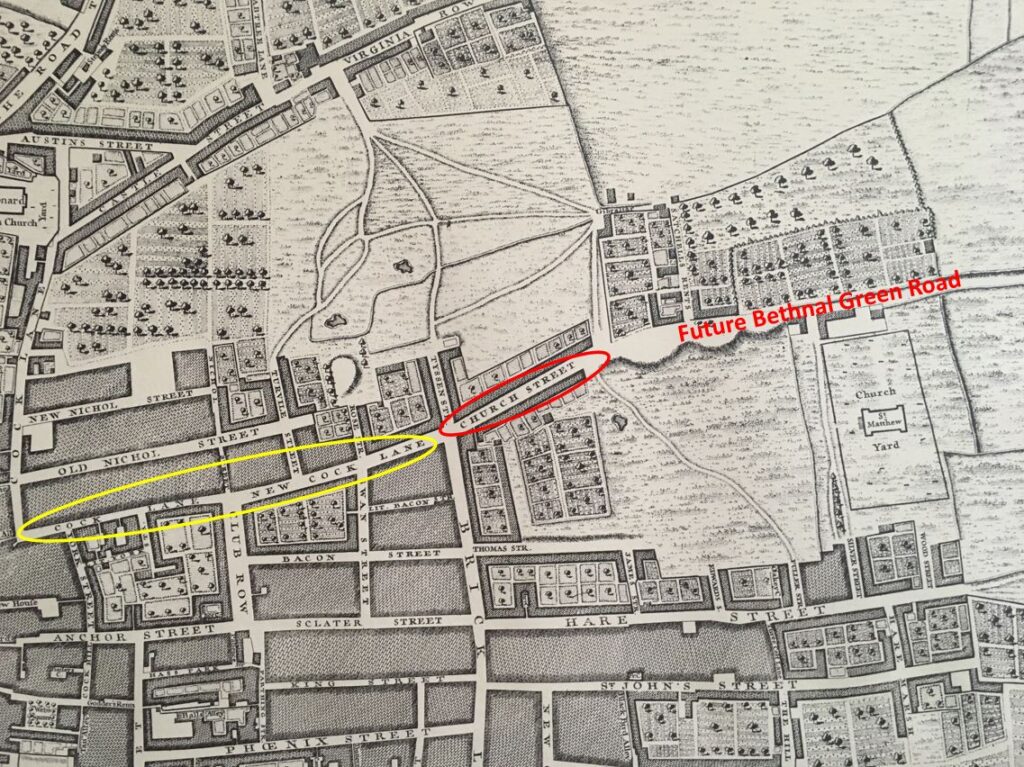

To illustrate the age of the street, the following is an extract from Rocque’s 1746 map of London:

The future Bethnal Green Road is to the right. Church Street is within the red oval, however this part of the street is now part of Bethnal Green Road, which today turns a little south, below New Cock Lane and Cock Lane (within the yellow oval), which today is Redchurch Street.

When the extension to Bethnal Green was built, New Cock Lane seems to have changed name to Church Street, and the junction in the 1980s photo is where Bethnal Green Road and the old New Cock Lane diverged.

The change of name from Church Street to Redchurch Street took place at some point in the first half of the 20th century.

It was still Church Street in 1911, where in the census, James Cooper is listed as the Licensed Victuallier of the Dolphin pub, along with his wife Mary, and his sister-in-law Emma Bass who was listed as a General Help.

In the 1921 census, the street is still Church Street, and Cornelia John Alfred was the landlord, living in the Dolphin with his wife Leah.

So the name change seems to have taken place between 1921 and the 1948 OS map.

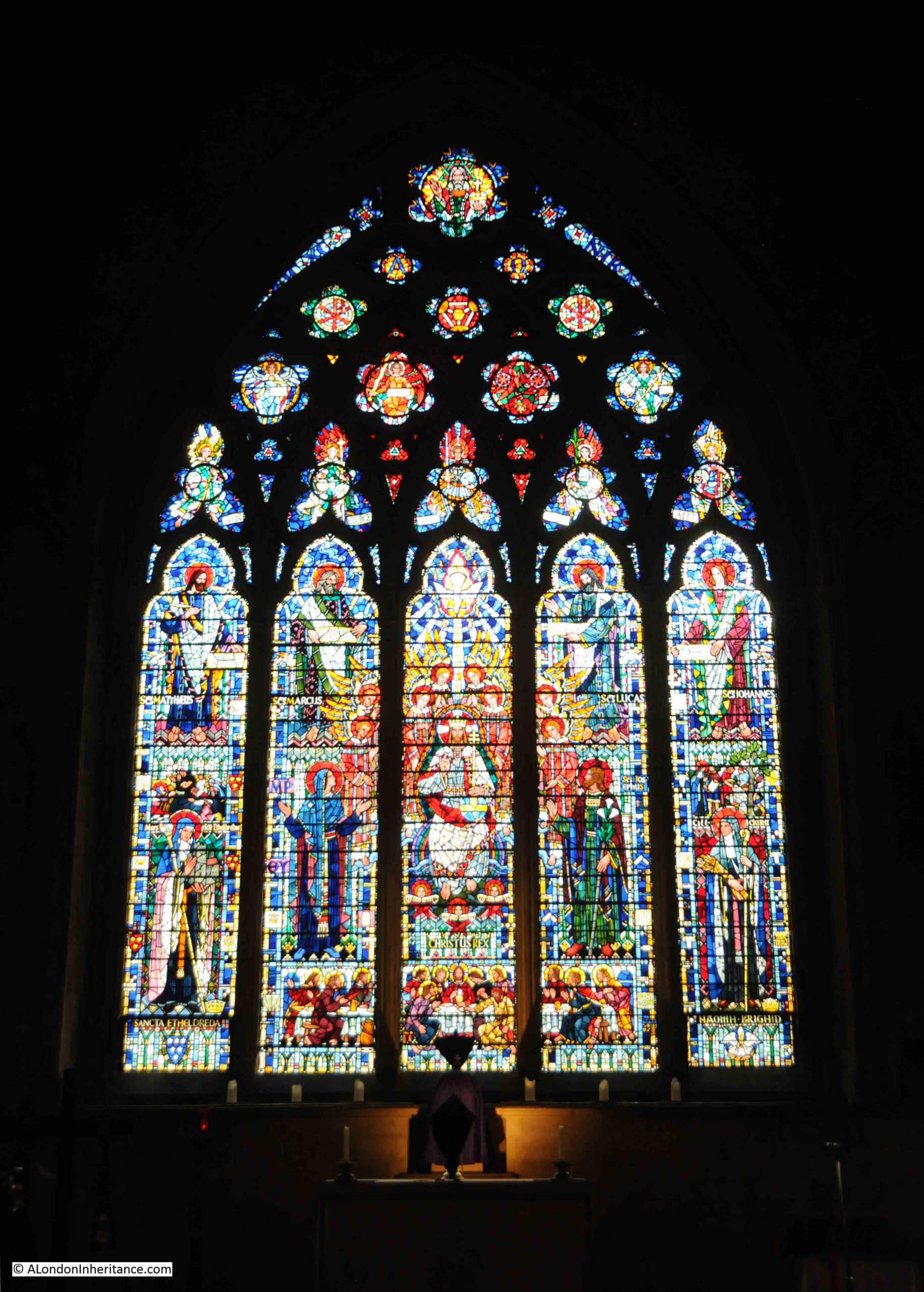

According to the Tower Hamlets Conservation Statement, the name Redchurch Street comes from the church of St. James the Great which is strange as the church is a reasonable distance east along Bethnal Green Road. The church was the first red brick church in the area when built around 1840, and seems to have given the description of the church to the name of the street. the church closed in the 1980s and is now housing.

The story of the Old Nichol and the Boundary Estate to the north of Redchurch Street is fascinating, and has been on my very long list of subjects for a blog post, however if you would like to read more about the Old Nichol, I can thoroughly recommend “The Blackest Streets: The Life and Death of a Victorian Slum” by Sarah Wise.