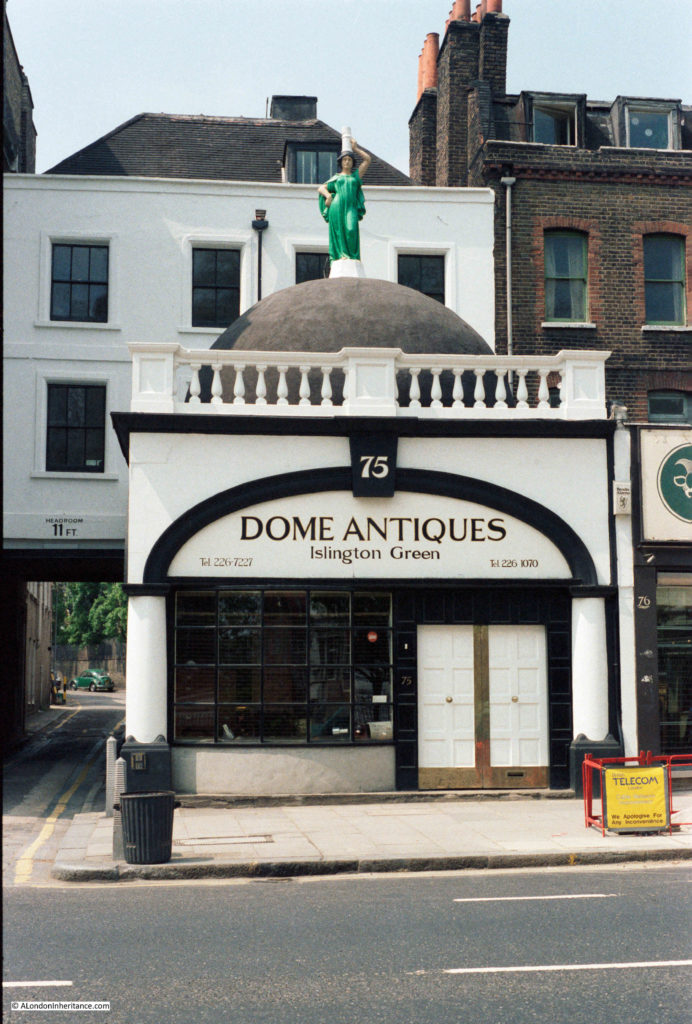

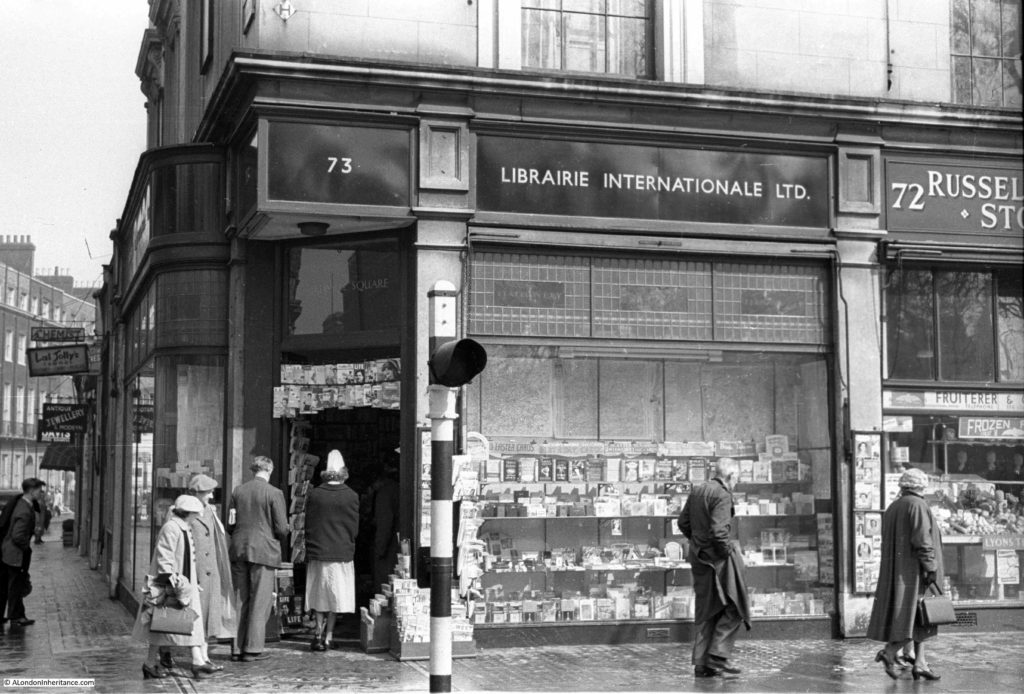

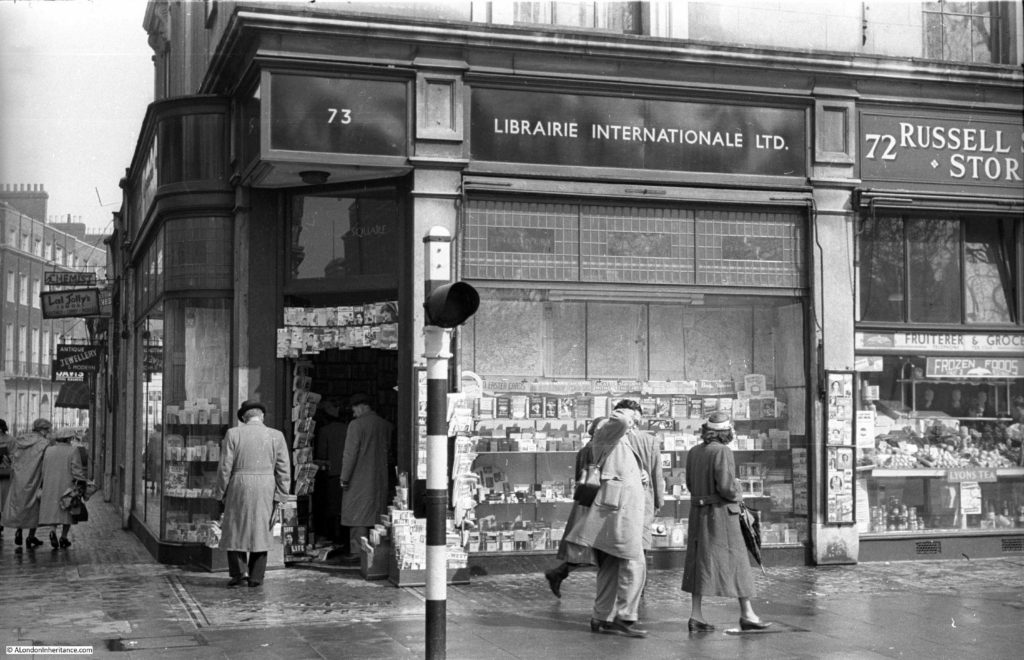

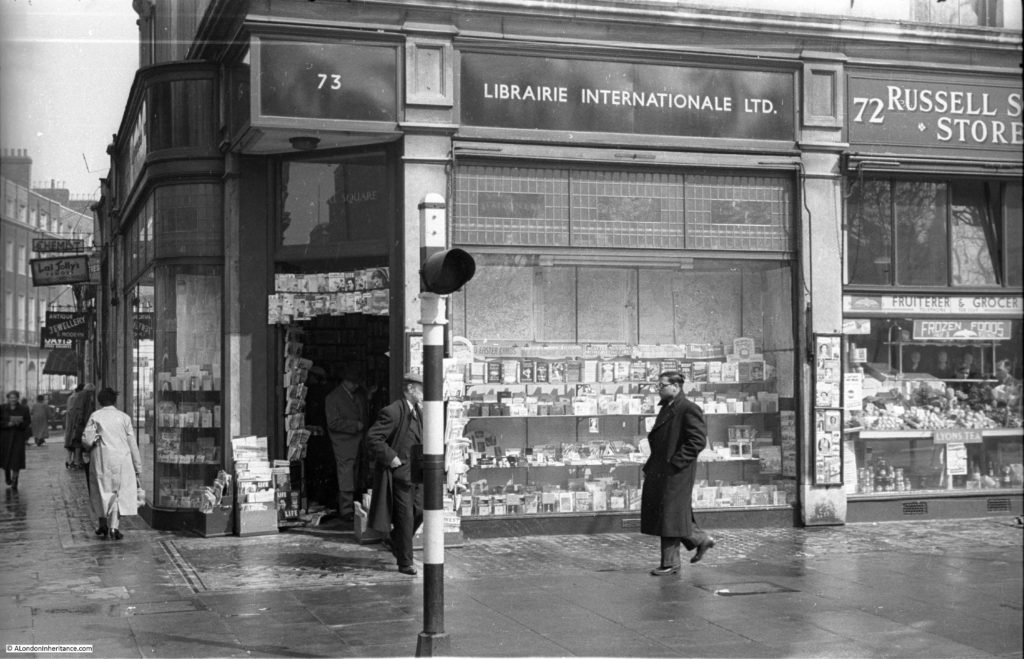

Last weekend I was in Islington Green for the first time in a few years. It was a perfect opportunity to photograph a rather unusual building, last photographed in 1985:

The same building in February 2020:

Before getting into the history of the building, there are two key differences between the views in 1985 and 2020 which typify what has happened across all London streets, not just Islington.

The first is the loss of many one-off shops, many of which were traditional to a specific area. There were a number of antique shops around Islington Green, today they remain clustered around Camden Passage. All too often chain shops have taken over from so many one offs.

The second is the CCTV camera. Initially I was frustrated with having the pole, CCTV camera and equipment boxes in front of the building, however they do provide a perfect demonstration of the growth of CCTV monitoring across the city, and the amount of street furniture. These are all too often installed without any apparent consideration of the impact on the surrounding street scene and buildings, as the 2020 photo illustrates.

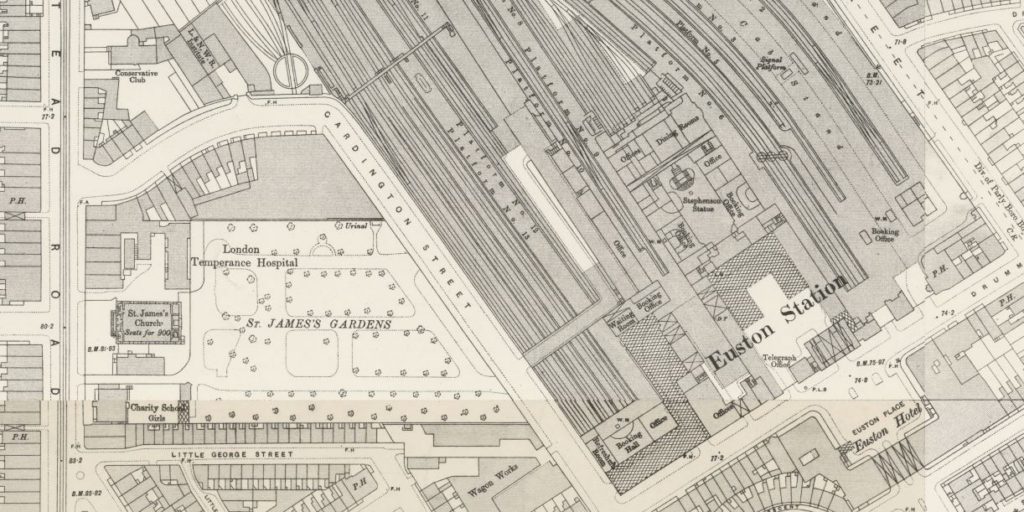

The building has an interesting history. It was purpose built as the Electric Theatre and opened in February 1909. The domed section was originally open at the sides and formed the entrance vestibule to the cinema. Passing through the vestibule was the foyer which was built into the ground floor of the three storey building we can see from the street, and behind that was the single storey auditorium.

The Bioscope on the 11th February 1909 recorded that “The new Electric Theatre at 75, Upper Street, Islington, opened on Saturday last, is a very handsome and artistically decorated hall, both inside and out. Everything for the comfort of its patrons has been studied, and as it is owned by Electric Theatres (1908) Limited it will no doubt prove as successful as the other well-known theatres run by that company.”

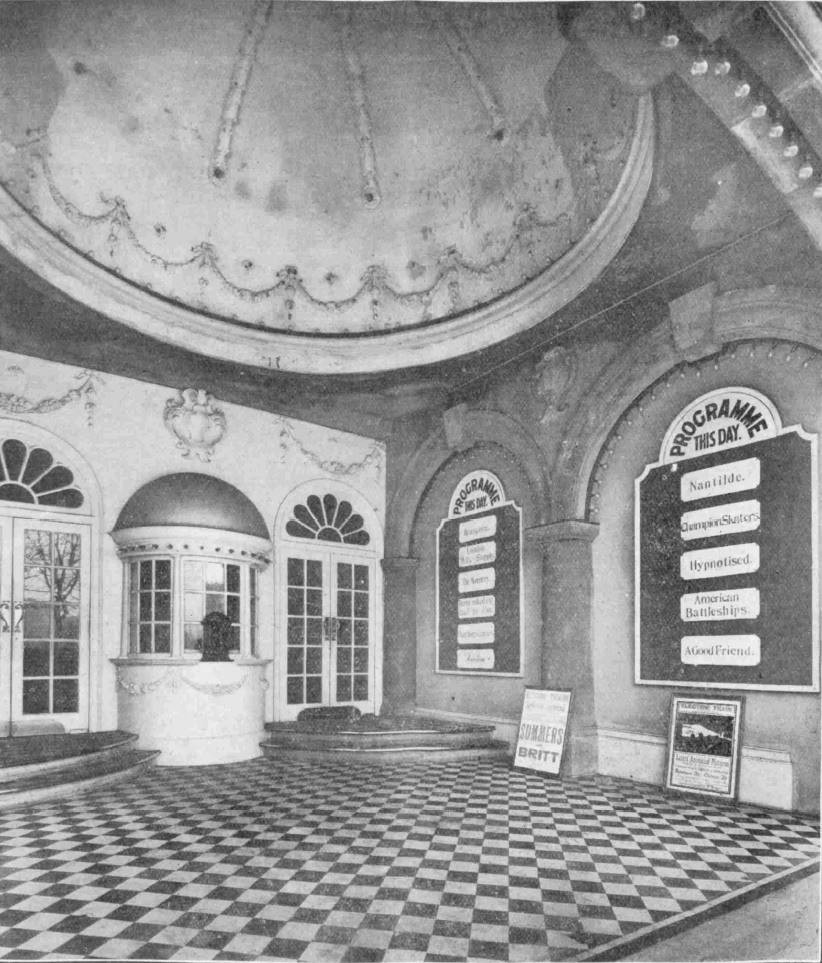

The Electric Theatre company was one of the first to open a chain of cinemas across London. The interior of vestibule leading into the Electric Theatre is shown in the following photo. The decorated interior of the dome can be seen. Imagine this view if you walk in today for a coffee.

There is an interesting statue on top of the dome. The following photos show the 1985 statue (left) and 2020 version (right).

The figure on top of the dome, in 1985, was painted and holding a lighted torch above the figure’s head. By 2020, the coloured paint had been removed and the lighted torch appears to be missing.

The Electric Theatre in Islington did not last too long, closing in 1916. It is good to see this unusual building still facing onto Islington Green, and being Grade II listed, the building is protected.

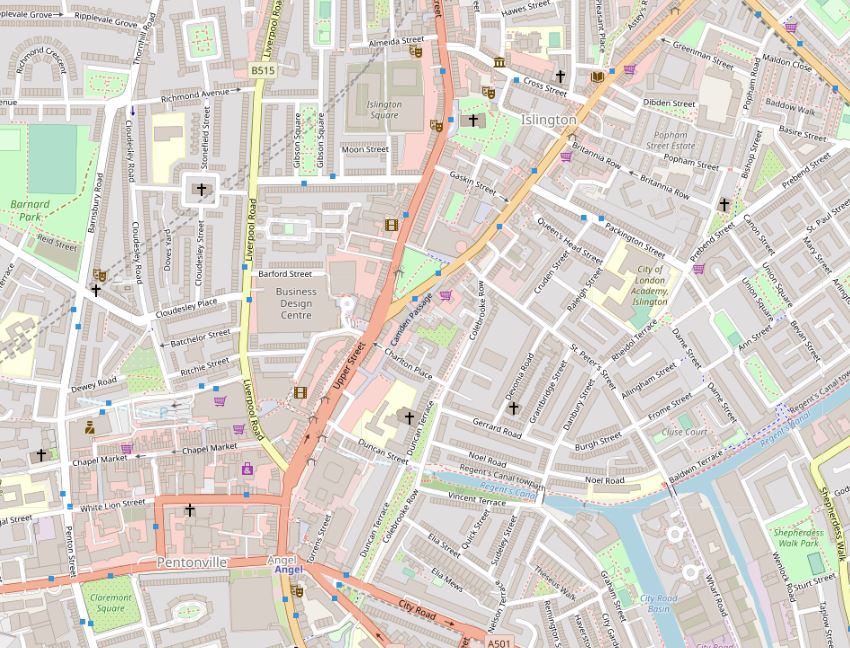

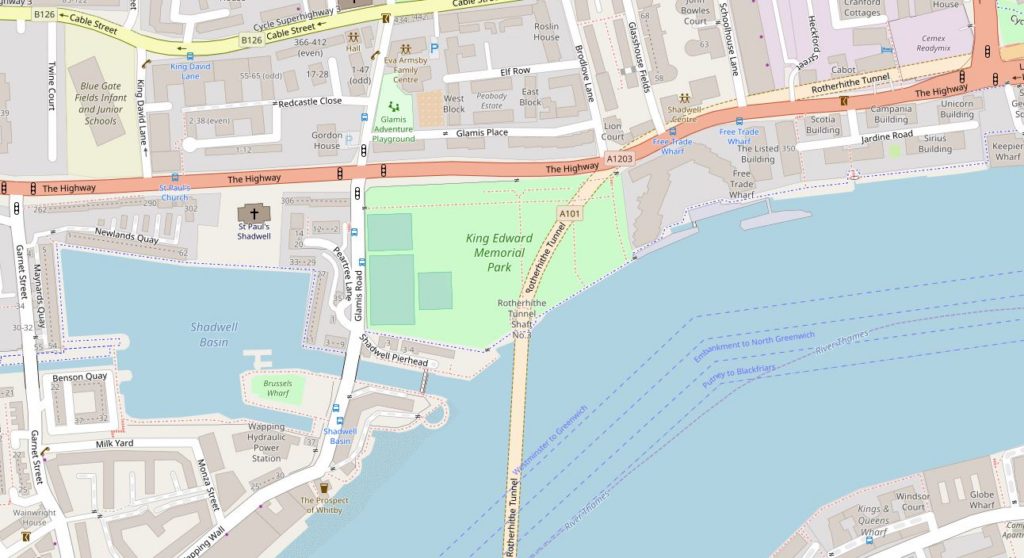

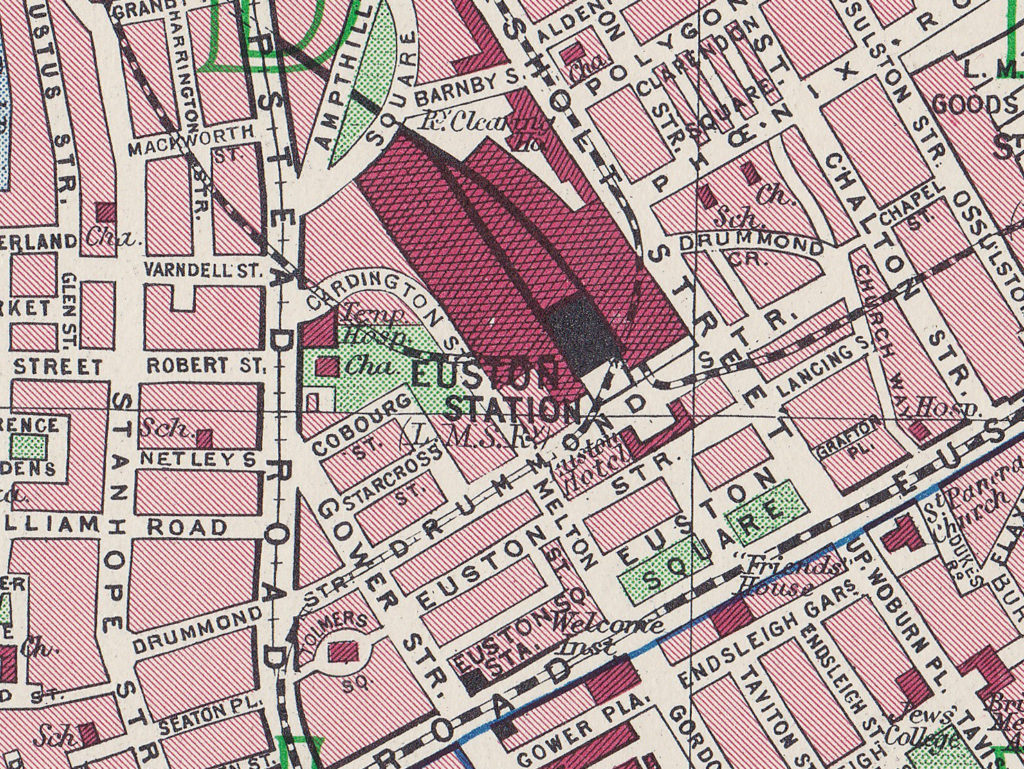

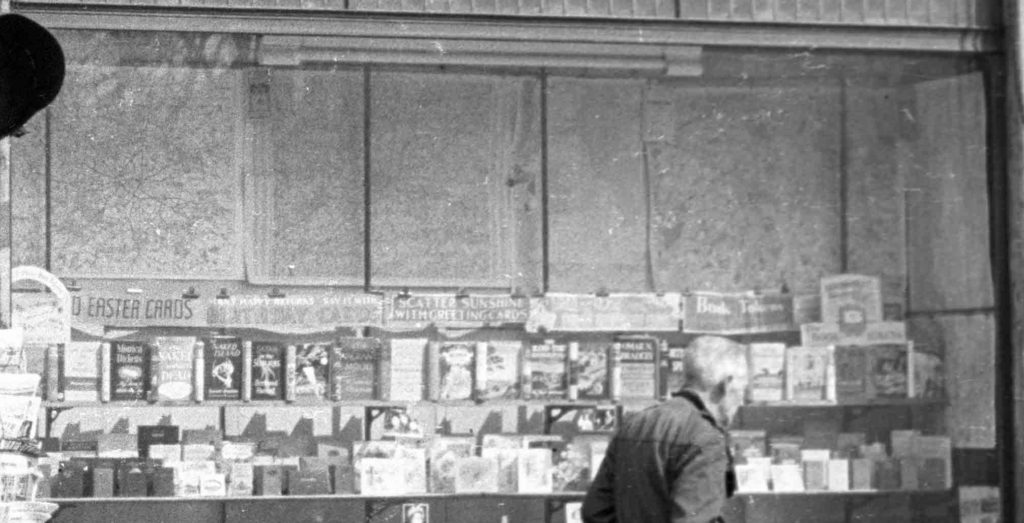

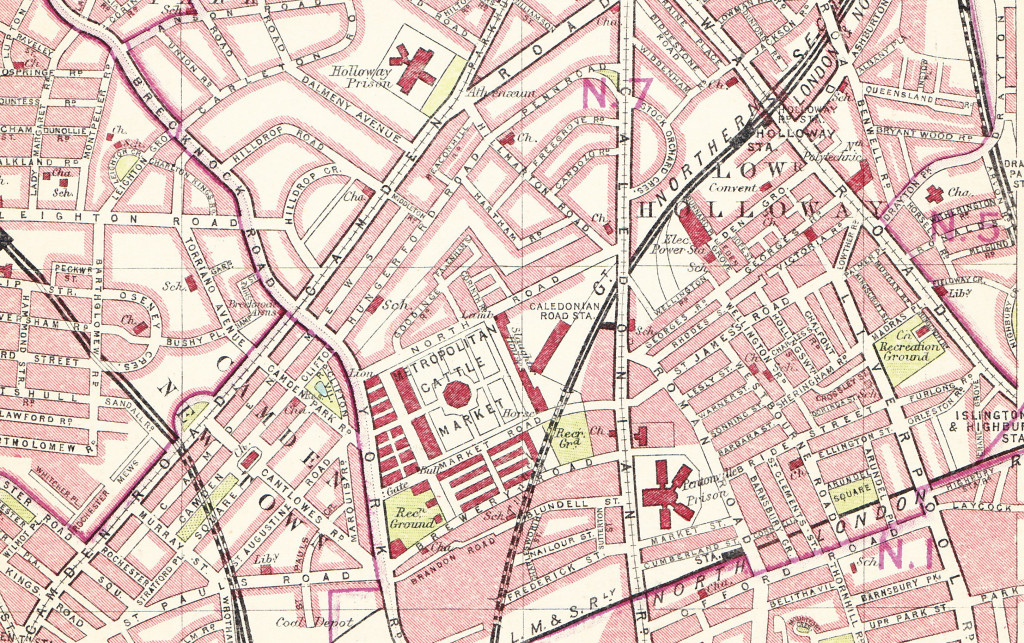

Islington Green is a reasonably small, triangular green space to the east of Upper Street (the main A1 road). The street to the east of the green space is called Islington Green. The following map extract shows Islington Green as the triangular green space in the centre (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The area is very built up today, and was part of the late 18th, early 19th century expansion northwards of London, however the twin roads and road junction that forms the triangular space where Islington Green can be found has long been a feature.

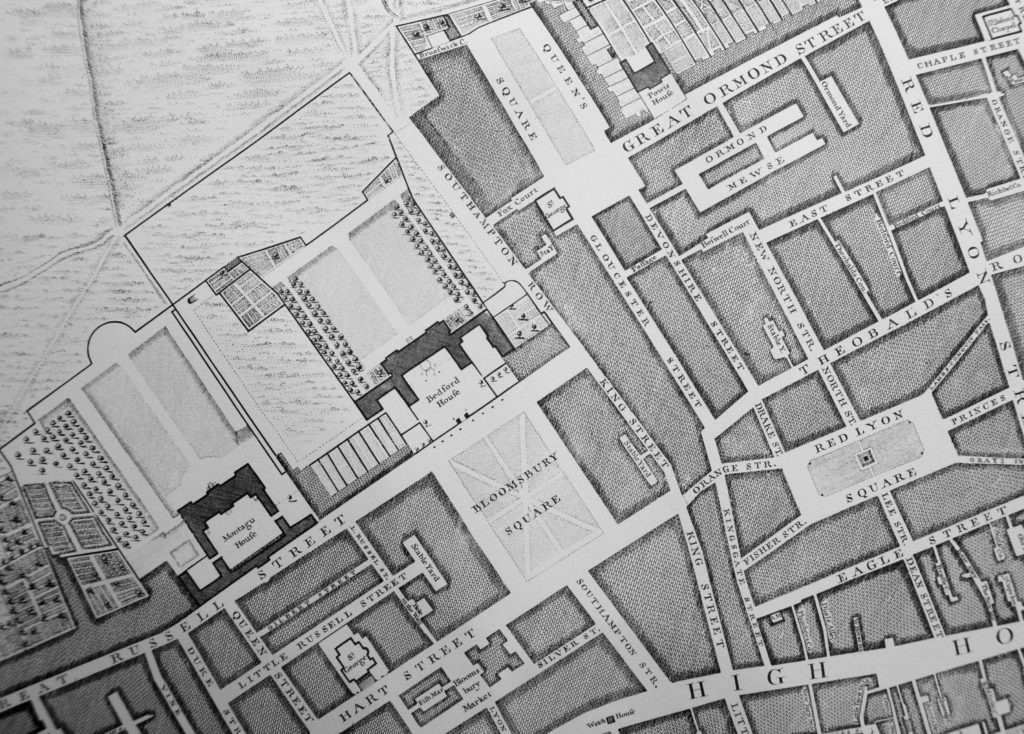

The following extract from John Rocque’s 1746 map of London shows the familiar shape of Islington Green where the two roads come together. There was ribbon development along the roads and some streets just to the north, but the rest of area is still fields. Note the New River running through the area between Hertfordshire and New River Head, just to the south.

One hundred years later in 1847, Reynolds’s Splendid New Map of London shows the area has transformed from fields to streets. Islington Green is still a feature where Upper and Lower Streets meet towards the top centre of the map.

This is the green space of Islington Green looking north. There was a council event occupying the wider northern width of the space at the time.

If you look to the top right corner of the green and you can just see a row of terrace houses.

I wanted to find this terrace as it provides a good illustration of Islington before it transformed to the area of expensive housing it is today, and how you can never really trust the age of a building by looking at the exterior.

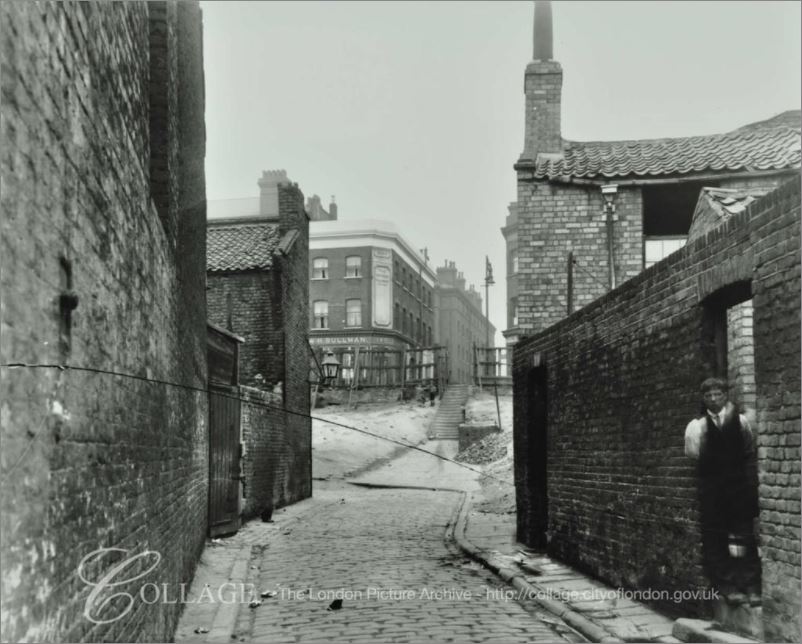

Walking to the north-east corner of Islington Green and this is the view of the terrace across the road. The view shows what looks to be a complete row of late 18th, early 19th century terrace houses.

This was the same view in 1979:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_188_79_1227

To confirm that this is the same view, look at the building on the far left of both photos, just across the side road where the terrace stops and it is the same building, although the terrace looks very different and the fourth house from the left is missing.

Although many of the 18th / 19th century buildings in Islington were in a poor state in the 1970s, the reason for the condition of this terrace is a bomb in the last war. The London County Council bomb damage maps have the terrace marked as “general blast damage”. The bomb that caused the damage probably landed behind the terrace as the building behind is marked as “damaged beyond repair”. The house on the far left of the terrace still looks as it probably did after the war with smoke marks and missing top floor window frames.

The fourth house in the terrace from the left is completely missing – metalwork can be seen supporting the walls of the houses on either side of the missing house.

But look at the terrace today, and it looks original. The missing house has been replaced with a house identical to the others, and just looking at the terrace you would assume a complete survivor from the time of the original build.

The open space to the right of the 1979 photo was a Gulf petrol station – today the space is occupied by a Tesco store.

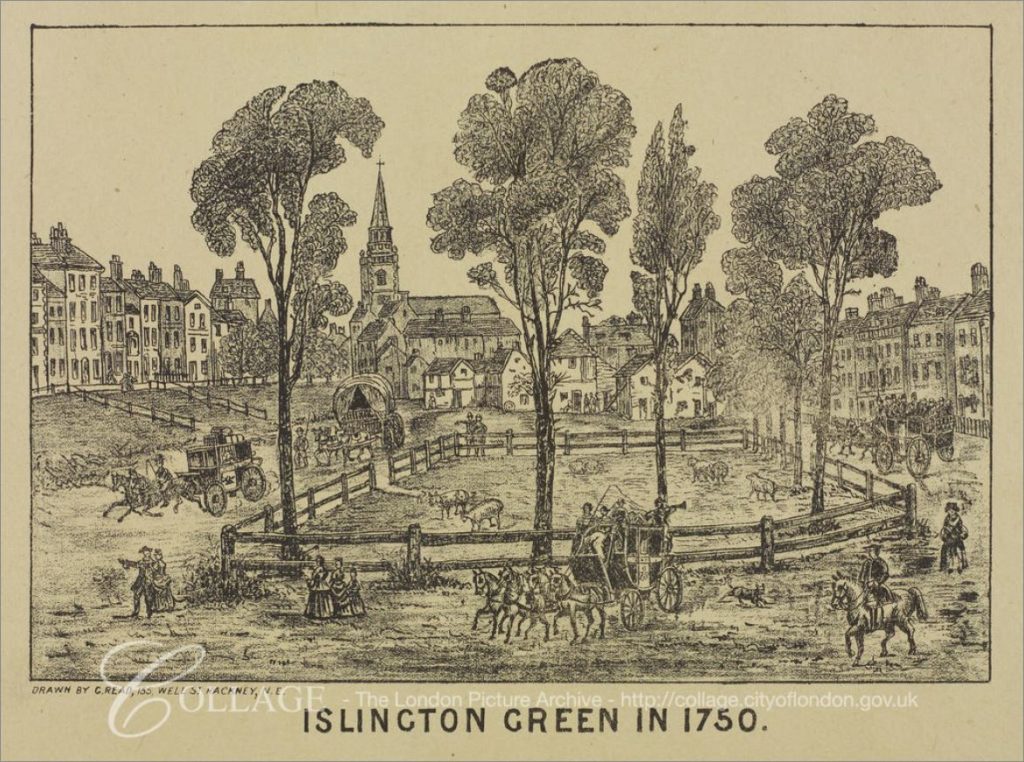

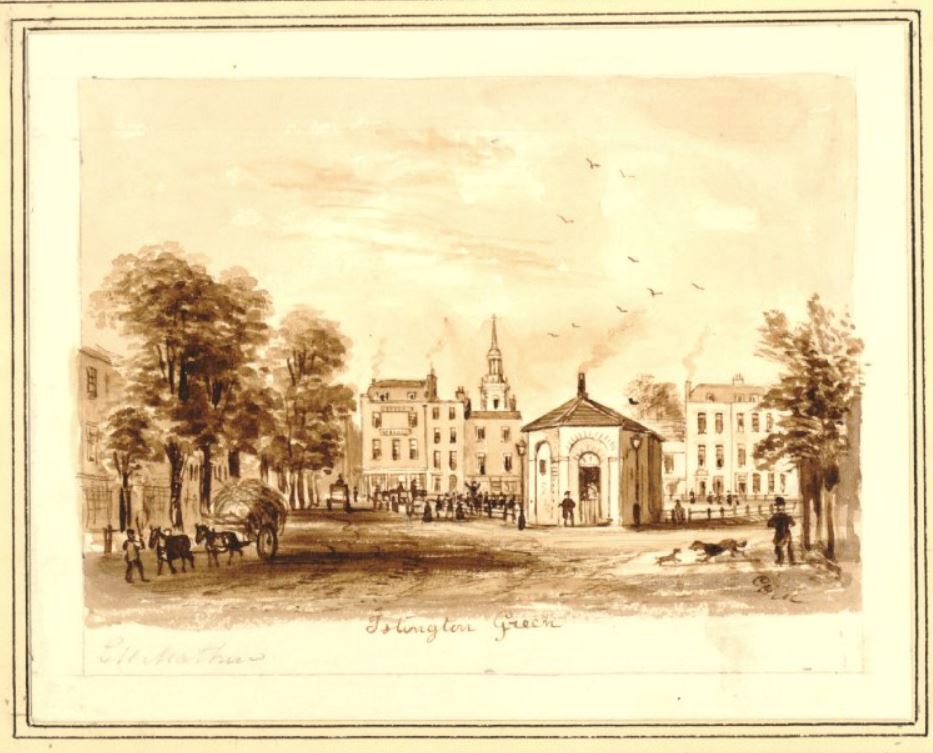

The following print of Islington Green from 1750, just a few years after the 1746 map shown above, shows what appears to be the same terrace to the right of the green. The view is looking north, with the church of St Mary in the background.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: p5379292

90 years later, and more substantial building lines the northern edge of the green.

The structure on the green in the above print, is probably the one mentioned in the following extract from a report in the Islington Gazette on the 12th of March 1859, which also provides an indication of the state of the green, prior to Victorian improvements:

“A short time since the police gave up possession of their old quarters, the Watch-house on Islington Green, which was built in 1779, and this elegant structure now belongs to the parish. The best use it can be put to is to sell it as old building materials, and this will immediately be done. The Green will then pass into perhaps its final condition.

This open space, for which so strenuous a battle was lately fought and won, was formerly a piece of waste ground, uninclosed, and was granted to Trustees for the use of the parish by the lord of the manor in 1777.

For a long time, however, it was made the common laystall for a great part of the dirt and filth of the parish.

A watch-house, together with a cage, engine-house, and a pair of stocks, stood in the middle of the Green until the present watch-house was built. Upon its site, the Vestry have now determined to place a drinking fountain and a better situation could certainly not be found for it. it will be erected at the apex of the Green which divides the Upper from the Lower street.”

The word “laystall” refers to a place where “waste and dung” is deposited, so this gives a good idea of how Islington Green would have been used for prior to the mid 1700s.

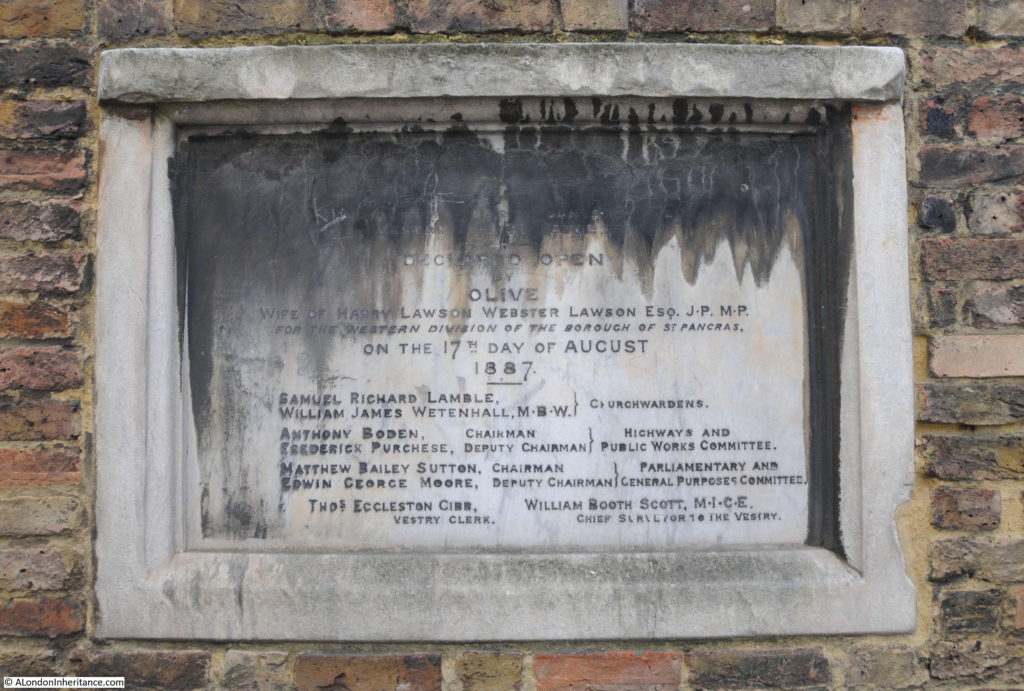

In the 1860s Islington Green was “improved”. The green was grassed, trees and shrubs were planted, and Islington Green was transformed to the Victorian view of an improved city green space.

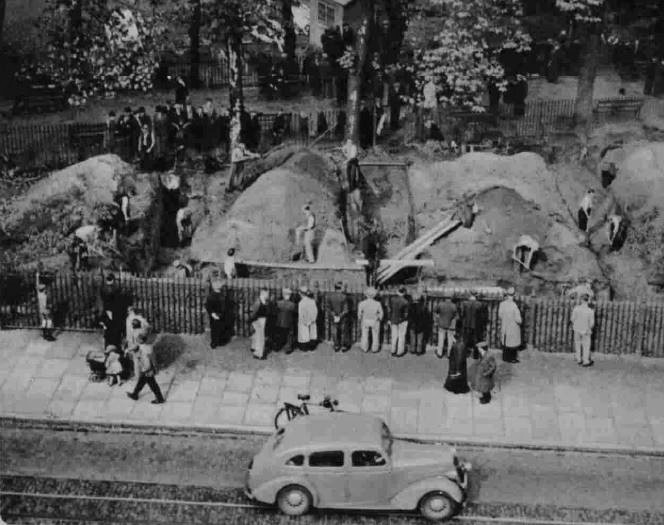

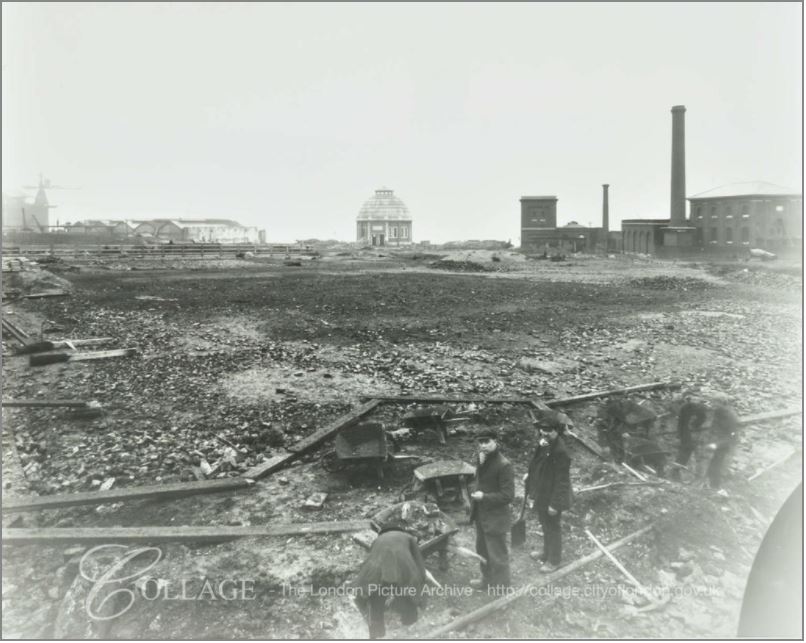

The next time that Islington Green would be transformed was in 1938 when in preparation for the expected war with Germany, and the use of air power to bomb cities, air raid trenches, along with more substantial shelters were being dug across the green.

The following photo from 1938 shows “labourers engaged in the construction of trenches in one of the smaller open spaces of north London”.

Whilst the following photo from 1939 shows the conversion of one of the trenches from an open trench to a more secure, enclosed shelter made of concrete and steel. The photo shows Sir John Anderson, Lord Privy Seal inspecting the new shelters.

It would be interesting to know if there are any remains of the shelters still under Islington Green.

Time for a walk around the green. The following photo is looking north along Upper Street with the dome of what was the Electric Theatre on the left.

As well as the location of the Electric Theatre, the above photo shows the location of a second, early 20th century cinema on Islington Green. To the right of the photo is “The Screen on the Green” cinema, the wonderful facade of the cinema is shown in the photo below.

The cinema opened four years after the Electric Theatre, in 1913 and named the Empress Electric Theatre. In the early years of the 20th century, cinemas still used the name theatre, and the word “electric” was often included, as in Islington, to accentuate the modernity of the form, and the use of electricity in the display of film.

Not long after opening, the “Electric” was dropped and the name changed to Empress Picture Theatre, which was retained to 1951 when the name changed to the Rex Cinema, followed by Screen of the Green after the Rex closed in 1970.

Watching a film at the Screen on the Green is a very difference experience to the typical multi-screen cinema.

In addition to the two cinemas, another building facing onto Islington Green was an entertainment centre, although this was music hall rather than film.

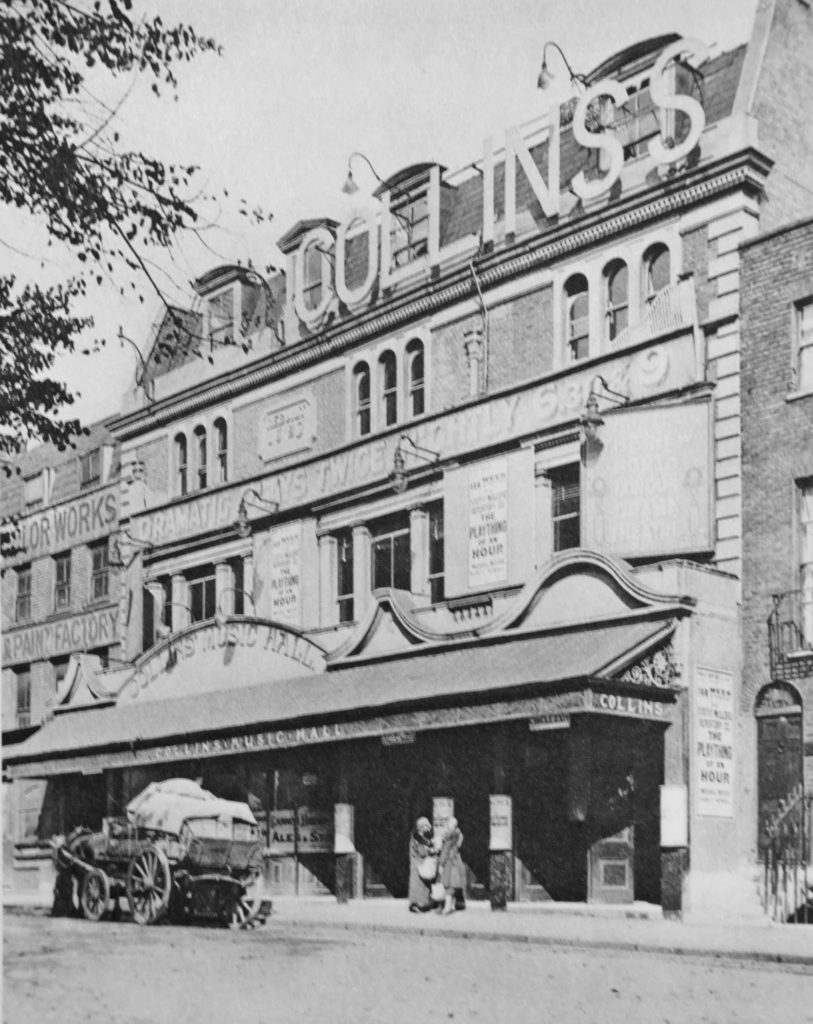

Facing the northern side of the green is the facade of the building that was Collins Music Hall.

The building is now a Waterstones bookshop, but it is still possible to imagine the building as it appeared when it was entertaining the people of Islington:

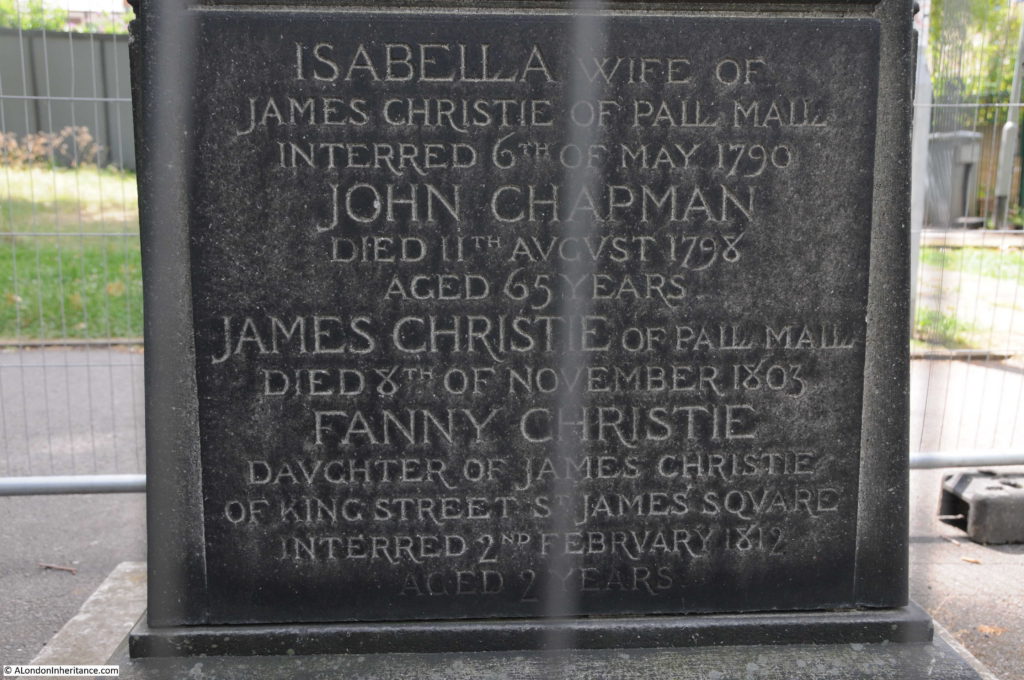

A pub, the Lansdowne Arms originally occupied the site, and in 1862, Sam Vagg, a chimney sweep who had built a stage career as Sam Collins turned the pub into a music hall. Three years after opening, Sam Vagg died at the age of 39, however the music hall would continue and retained the name of Collins in honour of the founder.

The entertainment on offer can be appreciated by taking a random edition of the Islington Gazette and checking what was on the bill. The 15th September 1887 edition details the following “Varied Star Programme”:

“The Five Jees, in the Musical Smithy, Sisters Bilton, the enchanting duettists; Dan Leno, the champion comic of all comics; Ethel Victor, the dashing serio-comic; Florrie West, the charming serio-comic; Brothers Passmore, variety artists; Arthur West, extempore vocalist; Sisters Dagmar, the pleasing duettists; Charles Murray, comic; Jessie Hart, the sprightly serio-comic; Fred Carloss, the ‘Sloper’ comedian, Professor Wingfield, with his educated dogs; Swiss Mountaineers, the vocal trio.”

How was that for a night out in Islington – who could not be tempted by Professor Wingfield, with his educated dogs.

The music hall was rebuilt in 1897, this date is still visible on the front of the building.

In the following decades, Collins would continue to put on variety shows in the music hall tradition, and names such as Norma Wisdom, Benny Hill and Tommy Copper performed at Collins in the early years of their careers.

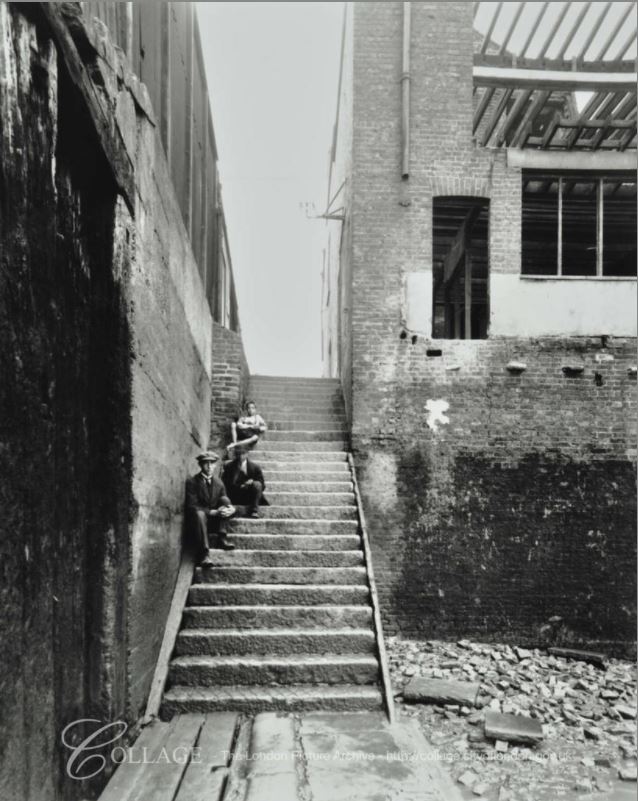

Collins Music Hall was very badly damaged by fire in 1958. Only the front and side walls survived, and the core of the music hall was lost, and the remains of the building (apart from the front wall) was demolished in 1963.

Collins Music Hall was also used for other purposes, which also give an indication of the poverty that existed in Islington. On the 24th December 1912, the islington Gazette carried a report titled “Christmas Dinners – Distribution Today at Collins Music Hall – Over 8,500 Dinners”:

“Through the medium of the Daily Gazette fund between 8,500 and 9,000 persons, or one in every 40 of the population of Islington, will participate in these Christmas gifts. the dinner parcels consist of meat, tea, milk, sugar, cake, rice and sweets, and will represent something like 10 tons of food.”

Up to 9,000 people sounds an enormous number, however this appears to have been only a proportion of those who applied. At the end of the article, the following appears in large, bold text:

“The Editor regrets exceedingly that he is unable to reply to the large numbers of letters received from poor and needy people in the four divisions of Islington, asking to participate in the distribution of dinners to-day at Collins’ Music hall.

Having regard to the enormous population of Islington, and the wide-spread poverty existing in the borough, it naturally follows that large numbers of applicants cannot be administered to.

The Editor hopes that the applicants who have been turned empty away will accept this explanation. Had the fund been half as large again as it is, most of the cases which unfortunately have been rejected could have been dealt with. Some of these, it is hoped, will be relieved from other charities.”

A clear reminder of the poverty that existed across London on a considerable scale.

The following photo shows the Fox on the Green. A pub at the north-west corner of the green.

Originally called just the “Fox”, reference to the pub dates back to the start of the 19th century, however I am not sure if the current building is the original. There are a number of newspaper references to the widening of the road north from Islington Green, starting from the Fox, and also one reference specifically referring to the Fox when describing how the Metropolitan Board of Works would preserve a licence to sell alcohol when they had demolished a pub, and before the replacement had been completed.

Apparently the Metropolitan Board of Works would install a temporary “shanty” on the site which would sell a minimum of a single drink a day. This would allow the licence to be preserved.

One newspaper report from 1881 which covered many of the improvement schemes in the area stated that St Mary, Islington was the “most populous in the metropolis”. An indication of how the area had developed from the fields of the 1746 map.

I need to research more to check the date of the current Fox, however whether this building, or a previous version, there are very many references to a large number of inquests held in the pub, adverts for staff, a suicide from one of the upper floor windows, theft and fatal accidents outside the pub – it was a busy place.

A view along Upper Street, to the west of the green showing a mix of architectural styles.

The larger brick building in the centre has a blue plaque stating that the singer and entertainer Gracie Fields lived here.

More mixed architecture and colour schemes.

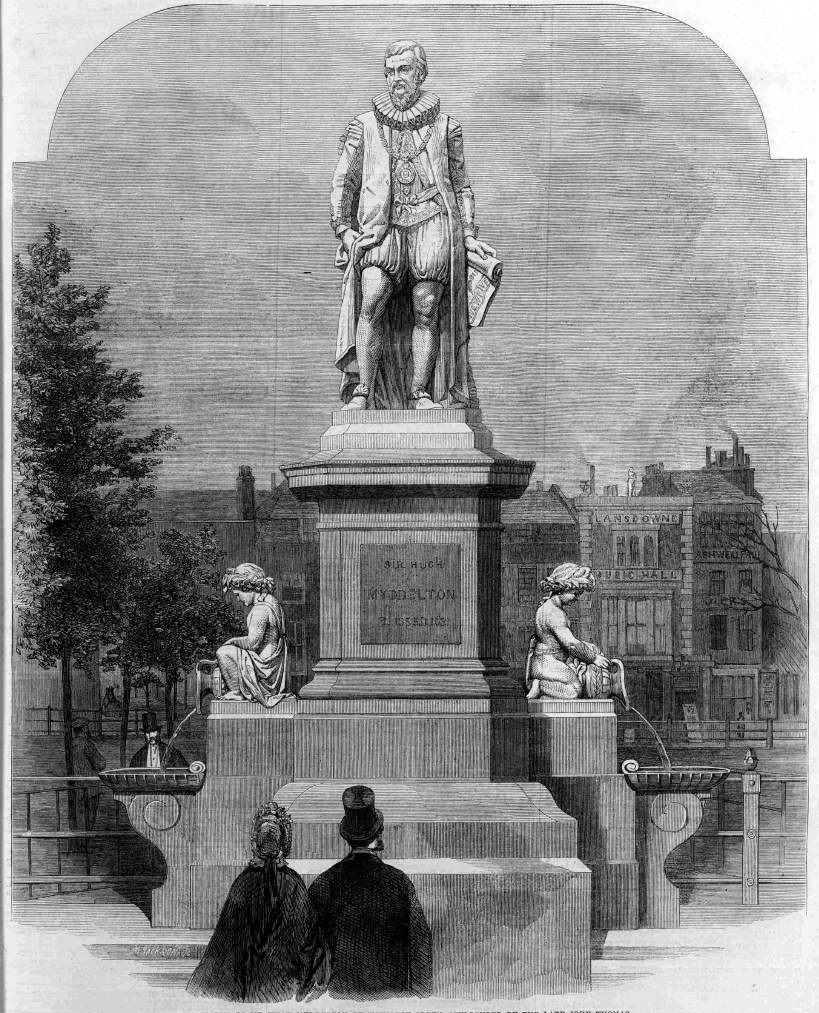

At the southern end of Islington Green is a statue of Sir Hugh Myddelton, the wealthy City Goldsmith, who took up the scheme for the New River, and saw construction through to completion. He is facing towards New River Head, a short distance further south where the New River terminated, and water was distributed onward to consumers across London.

The statue was erected in 1862, with the statue being funded by Sir Samuel Morton, and the pedestal and fountains on either side of the pedestal, by voluntary subscriptions and aided by a grant from the Vestry of Islington.

The following drawing from the year the statue was unveiled shows the fountains in operation. It also shows the words “New River” on the plan Myddelton is holding in his left hand – not sure this is still visible today.

Walking back to the Angel underground station, and this is the view looking back up to Islington Green with Upper Street to the left, the street with the name Islington Green to the right, and the green in the centre, with Hugh Myddleton looking back towards New River Head.

Although it is only a small bit of grassed open space, Islington Green is a very old feature. Formed where the road from the City split into two, the green was there when the rest of what is now Islington was still covered in fields and open space.

It has been used as a dumping ground, improved by the Victorians, seen a tremendous growth of traffic on the surrounding roads, along with building on all sides.

The green has seen the changing forms of entertainment, from pubs, to the Electric Theatre, the Music Hall, and now retaining one of London’s unique small cinemas.

Bombed at the north-east corner, and dug up for air raid shelters, Islington Green continues watching the changes in one of London’s northern villages.