During my walk through Bermondsey and Rotherhithe in the last couple of posts, I walked past one location that helps tell the story of the development of the railways in London as well as the long brick viaduct that stretches across so much of south east London from London Bridge Station. This was in Spa Road, Bermondsey, the location of Spa Road Station, London’s first railway terminus.

The brick viaduct that carries the railway out from London Bridge Station is an early 19th century engineering marvel. Although sections have been widened, and cast iron extensions to the side of the viaduct help carry the large numbers of trains that run along this route every day, the core of the brick viaduct is the same as when built for the London and Greenwich Railway Company in the 1830s.

When built, Spa Road was roughly the location where the viaduct emerged from the streets of south London and headed over open country and market gardens towards Deptford and Greenwich. In many places the viaduct is hidden from view behind the buildings that cluster up against the sides of the railway, however in the many streets that cross underneath the viaduct, we can still get a good view of this remarkable structure.

As I walked along Spa Road, this is the view of the tunnel underneath the viaduct from the southern approach where Spa Road narrows to pass between the original cast iron columns:

The central roadway runs through the middle of the tunnel with footpaths on either side between the cast iron columns and the tunnel walls:

And on the side of the tunnel is this plaque commemorating Spa Road Station.

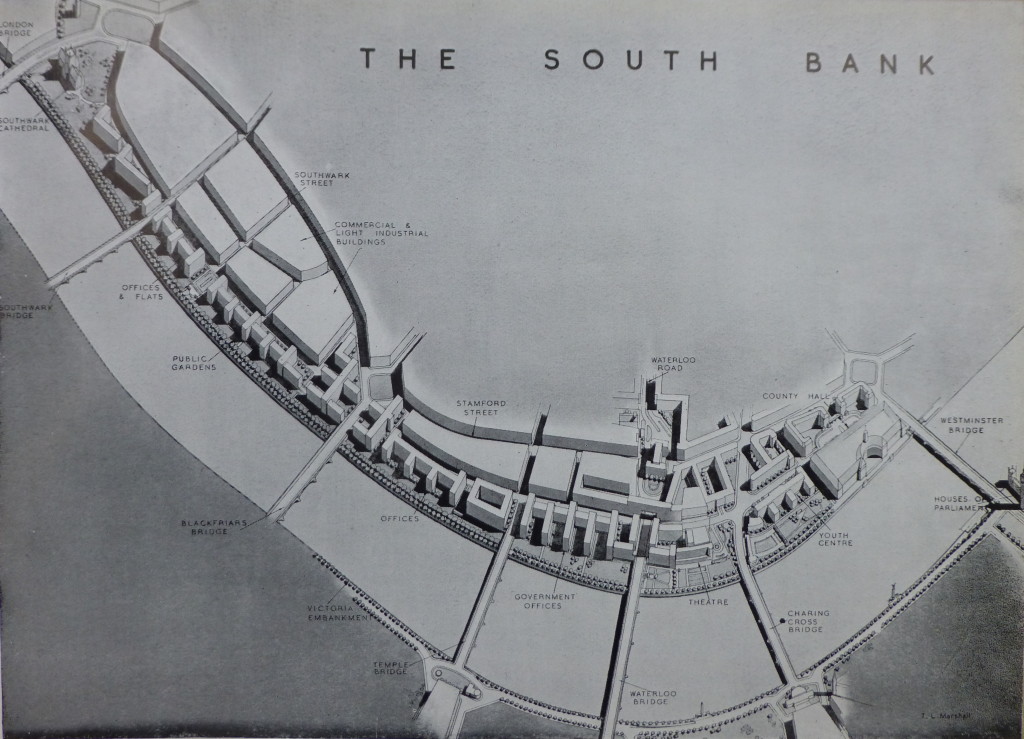

Proposals for a railway to run from London out to Deptford and Greenwich had been put forward in the early decades of the 19th century, and in the 1830s. the technical solutions, finance and Acts of Parliament came together to build this first railway into central London.

The land between the planned London terminus of London Bridge and Spa Road in Bermondsey was built up, very densely as the proposed route approached London Bridge. Running a railway at ground level would have caused considerable problems with the large number of streets that would have to be crossed by a railway. The land was also marshy and the open land out towards Rothehithe and Deptford was crossed by streams and ditches.

A viaduct was seen as the best solution as this would carry the railway above the marshy ground and would also ensure the streets that the railway crossed could run underneath the viaduct without obstructing street traffic or the railway.

The route was surveyed in 1832 and in 1833 the Acts of Parliament had been approved and the Act to create the London and Greenwich Railway (L&GR) received Royal Assent on the 17th of May 1833.

The L&GR began compulsory purchases of land in 1834, and the enormous quantities of materials needed to build the viaduct began to arrive on site.

Construction of the viaduct started at Corbetts Lane as this point was roughly in the centre of the route, and was in open country so was not dependent on the land purchases and demolition work required to prepare the route in central London.

Soon after construction started, the considerable quantity of 100,000 bricks were being laid daily and such was the demand for bricks that the price of bricks for sale in the London area rose due to shortages created by the quantities purchased for the construction of the railway.

On either side of the viaduct a roadway and footpath was constructed. This was intended to provide access to the arches and also to provide a parallel walking and carriage route with the railway charging a fee for access. The boundary between the pathway and the adjacent country was made up of shrubs and bushes.

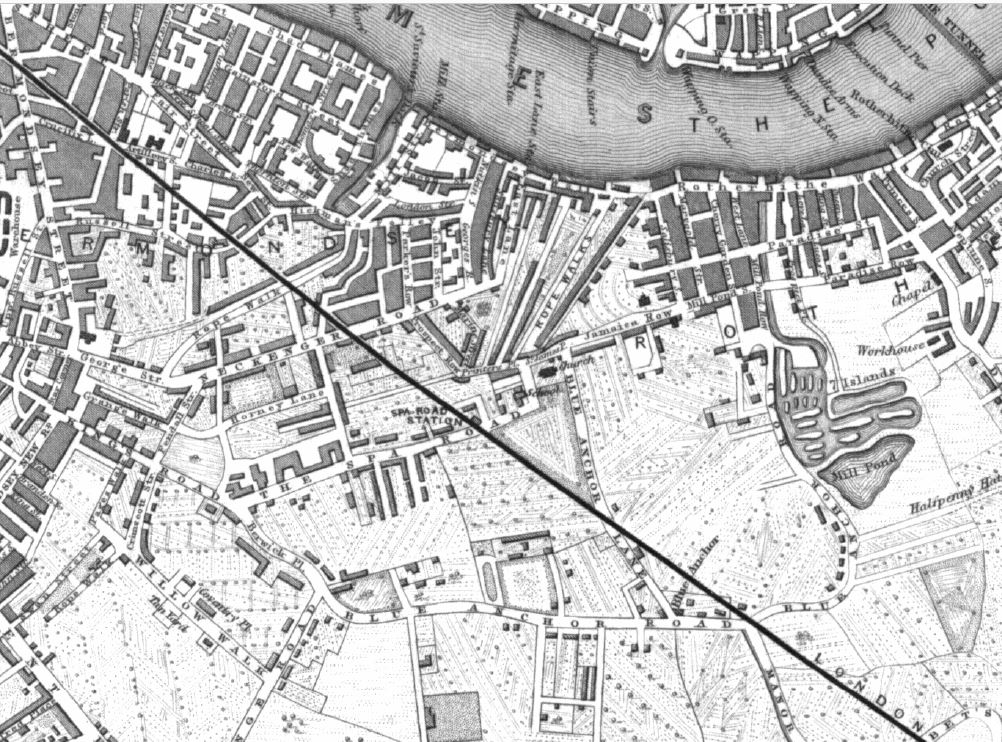

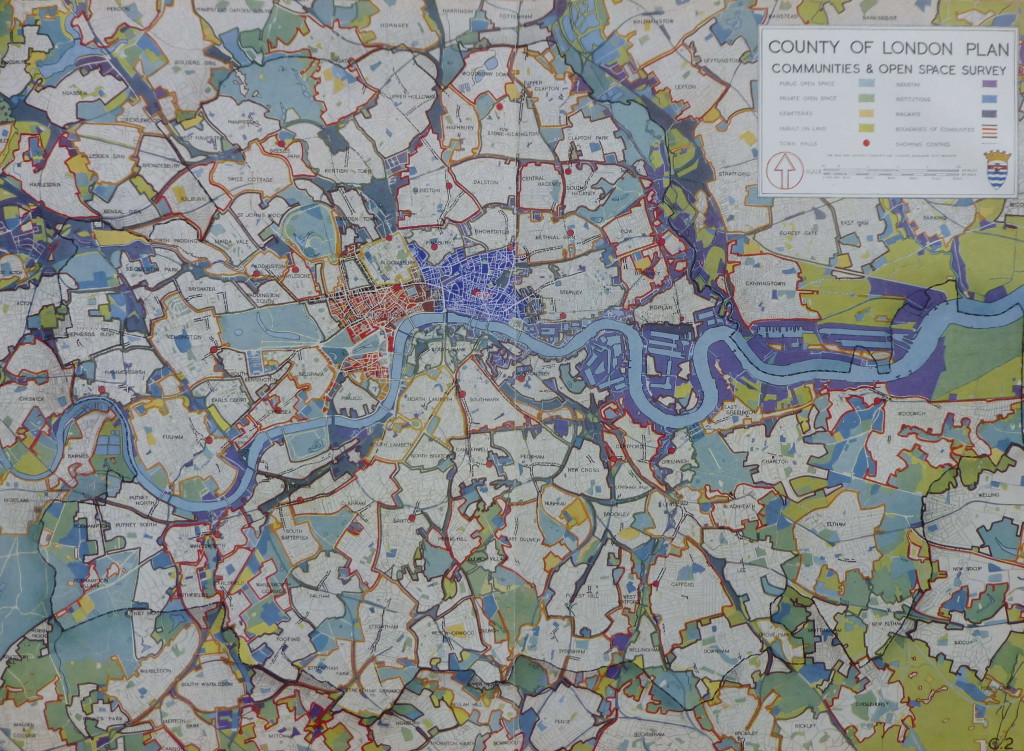

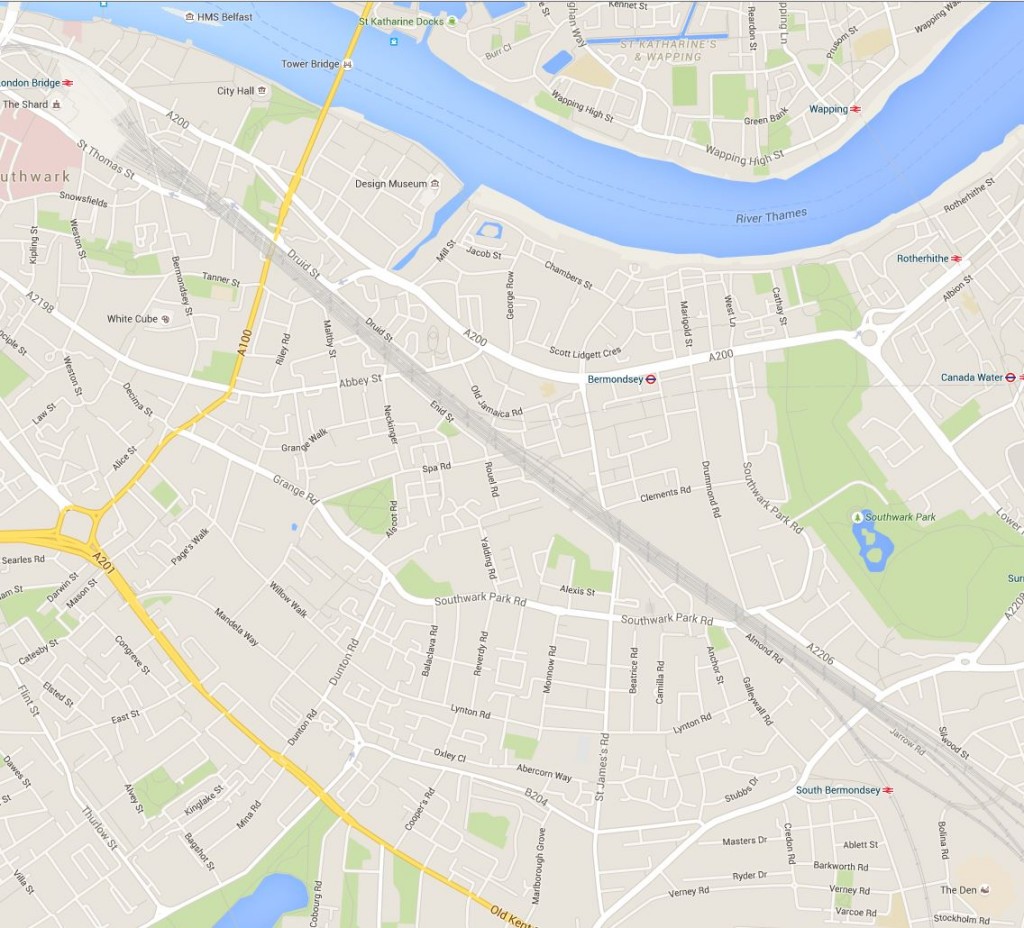

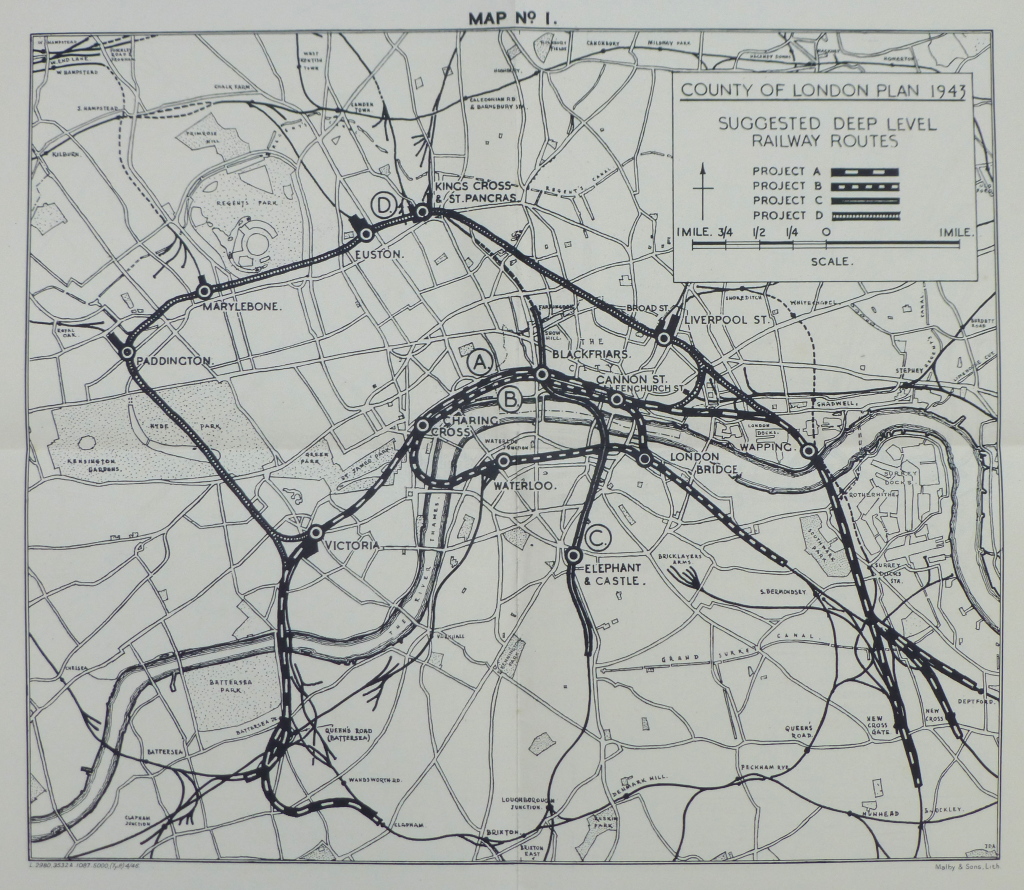

Maps provide an insight into how south east London expanded, the route of the railway and Spa Road Station. The first map shows Bermondsey in 1832:

I have marked the location of the future Spa Road Station with a red circle. The street running left to right underneath the circle is the future Spa Road, although in 1832 is was called Grange Road.

Look just to the upper right of the red circle and you will see the name Gregorian Arms – this is the pub on the Jamaica Road which is still in existence and with the same name. See my photo of the pub in last week’s post.

In 1832, the future location of Spa Road station was on the edge of development with open country and market gardens stretching out towards Deptford and Greenwich. To the right of the red circle are the Seven Islands and the Mill Pond. Occasional houses, a windmill and the Blue Anchor Public House can be seen along the sides of the streets.

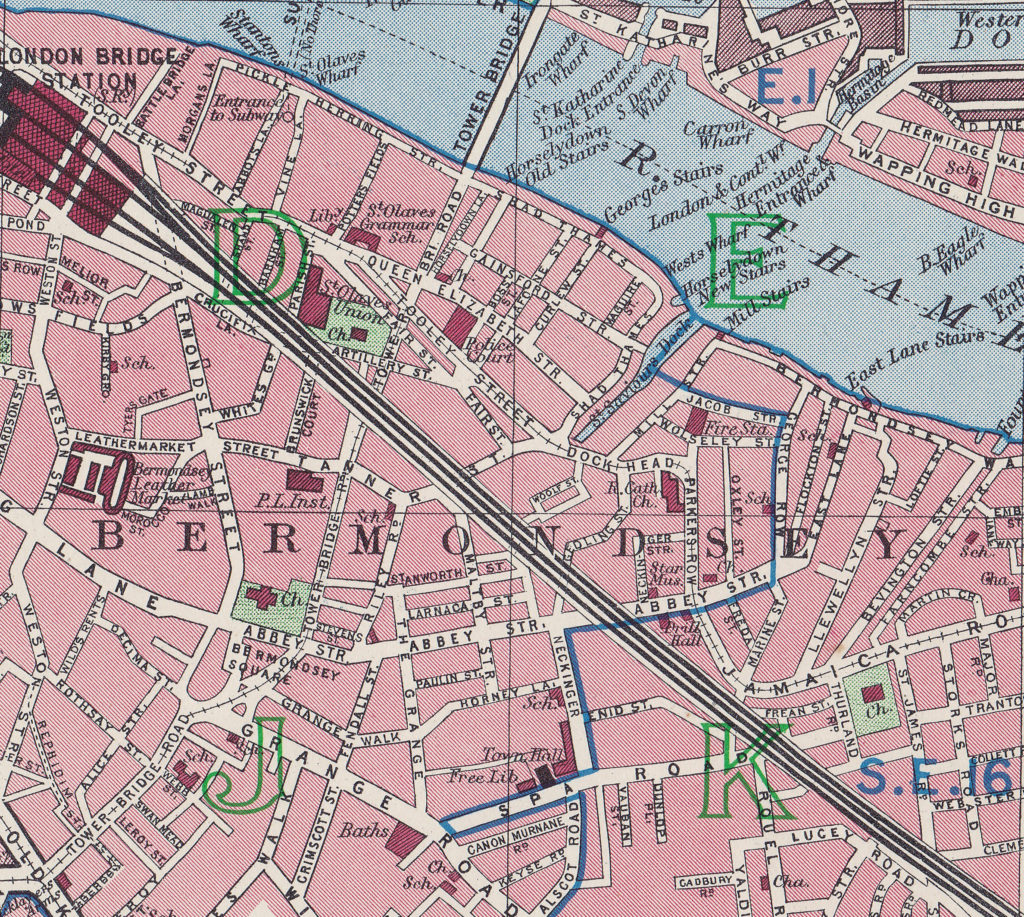

Now move forward, only 12 years to 1844, and a solid black line across the map shows the new viaduct of the London and Greenwich Railway. Look in the centre of the map, and replacing the red circle is the new Spa Road Station, with the street below the station now having been renamed The Spa Road.

Apart from the building of the viaduct, there has not been much more development, with the route of the railway to the south east still running over open land, although more detail has been added to this map which shows the cultivated nature of the land.

The 1895 Ordnance Survey map extract shown below demonstrates how the area around Spa Road had changed from open country to densely built streets in the 50 years between the above and below maps.

The map also shows that Spa Road Station has moved from being to the west of Spa Road to now being a couple of hundred yards to the east (I explain the move later in the post).

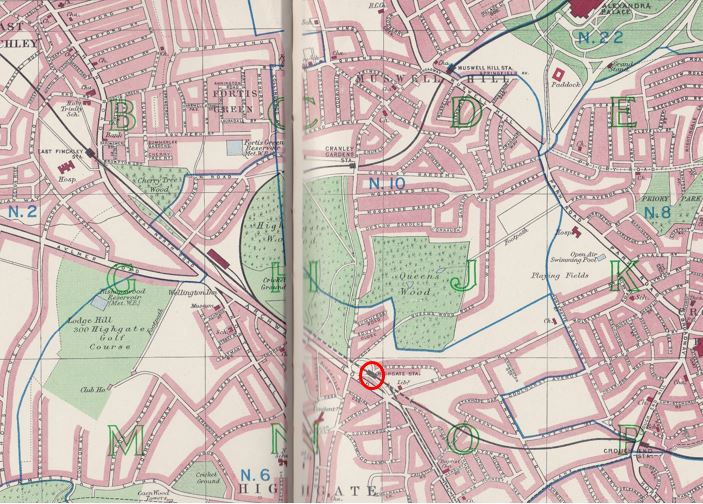

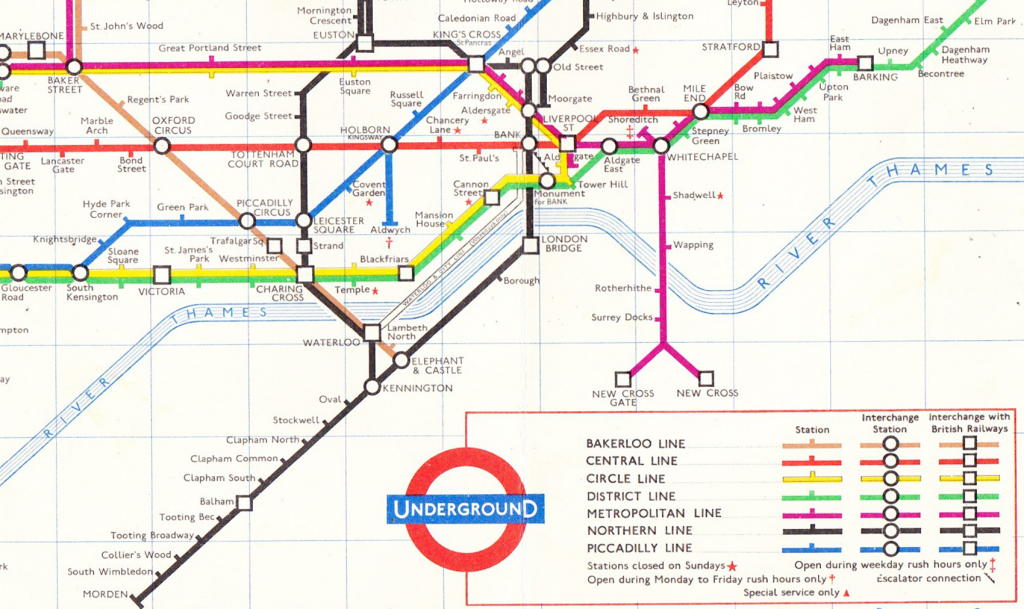

Forty five years later in the 1940 edition of Bartholomew’s Atlas of Great London, Spa Road Station has disappeared. Spa Road is in the lower right hand quarter of the map and the top right of the green letter K is roughly where the first station was located. The map shows that by 1940 there were no stations in the area with London Bridge being the terminus for rail lines heading off to the south east.

As the viaduct was completed, there was considerable interest in the London & Greenwich Railway which the company encouraged by providing access to the viaduct. On Easter Sunday 1835 some 10,000 people walked along the viaduct with the company taking almost £50 in tolls.

During the rest of 1835 construction of the viaduct at the Greenwich and London Bridge ends continued and test runs of trains were made along the route. By early 1836 there was considerable pressure to open the railway. Revenue was needed and there was welcome publicity to be had from being the first railway to run trains in London. It was therefore decided to open the line between Spa Road and Deptford whilst the Greenwich and London Bridge works completed.

The first train left Deptford for Spa Road Station at 8am on Monday 8th February 1836.

It must have been quite an experience to speed along in a train along the viaduct above the surrounding buildings and countryside. The Birmingham Journal on the 13th February 1836 reported “A passenger in a Greenwich Railway carriage, on Monday last, says, that in one of the experimental trips, the train of six carriages was conveyed at the rate of a mile per minute, or 60 miles per hour! He adds, that the sensation experienced was that of flying, rather than that which is felt in the most rapid of ordinary modes of travelling. There were two numerous parties of ladies in the carriages, who seemed highly delighted.”

The first trains on the 8th February marked the start of a regular service from Spa Road. Adverts in newspapers gave details of the services and fares. From the Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser on the 10th February 1836:

“LONDON & GREENWICH RAILWAY COMPANY. A TRAIN of the Company’s CARRIAGES will start DAILY at the following hours, until further notice – Fare, 6d.

From DEPTFORD to SPA-ROAD, BERMONDSEY, at eight, nine, ten, eleven, twelve, one, two, three, four and five”

The return journey from Spa Road to Deptford was at half past the hour.

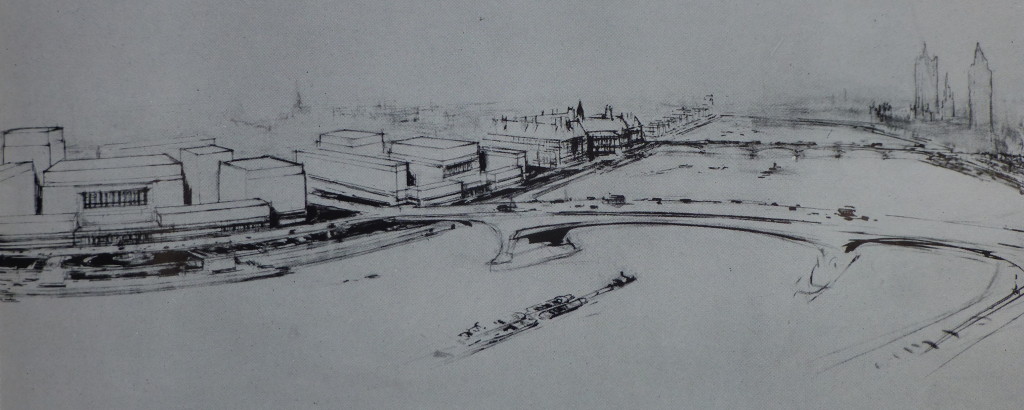

The first station at Spa Road was very much of a temporary form. Wooden stairs led up to the top of the viaduct where there was a narrow platform between the tracks and the viaduct parapet. The platform space was so limited that passengers would queue up the stairs until there was space to board a train.

The following print from 1836 shows the Spa Road tunnel underneath the viaduct with the stairs up to the station on the left. This is the view approaching the viaduct from the south.

Today, the above view is obscured by buildings, however the following photo shows the arches to the left of Spa Road and it was along here that the stairway led up to the platform.

The following photo shows the arches on the northern side, although these have been extended out from the original viaduct to form a bulge in the track for the future station. The metal bridge carrying the rail tracks rather than the original brick arches can be seen in the top left – another example of a later extension to the original viaduct.

The narrow nature of the platforms at Spa Road and the casual attitude towards the dangers of trains, with passengers standing on the tracks until the train arrived, resulted in a fatal accident at Spa Road on Monday 7th March 1836. From the London Evening Standard on the 10th March 1836:

“Mr James Darling, poulterer, Leadenhall-market, deposed that on Monday afternoon last, about three o’clock, he was standing by the platform on the Greenwich and London Railway, near the Spa-road, which is erected for the purpose of assisting passengers to get into the coaches that proceed on the railway. He was waiting for the steam engine to come from Deptford, which was shortly expected with a train of carriages, and which on arrival would be detached from that train to be joined to the train of coaches in which passengers would be conveyed to Deptford, and which train was on the railroad on the south line. While standing there he saw the train coming from Deptford. At that moment he was assisted on the platform. He had just been speaking to the deceased. The train came in at a rapid rate, and at the place where the engine is detached it receded from the north to the south line, and was not stopped till it came with a very violent concussion against the carriages. From the shock, witness was completely turned round. The train, by the impetus given it, was propelled to the barrier on the north line; on reaching which witness observed the deceased on the ground, dead.”

Despite this tragic accident and a number of other fatalities, the new railway was popular with travelers between Bermondsey and Deptford, and in December 1836 the stretch of viaduct between Spa Road and London Bridge opened allowing trains to now run to central London and out to Deptford, and following completion of the route from Deptford to Greenwich in April 1840 the full route was open.

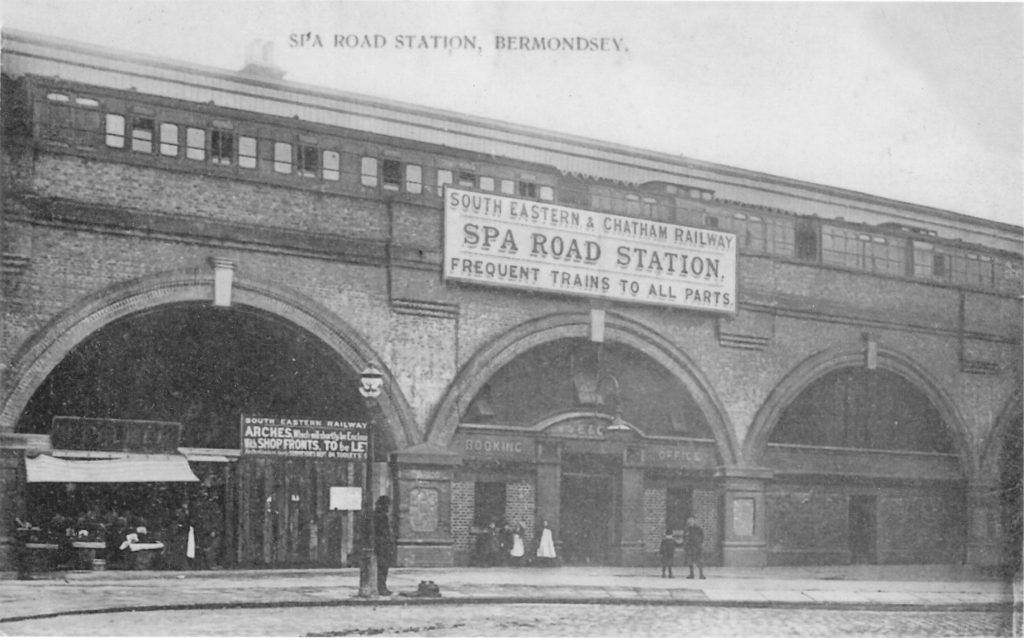

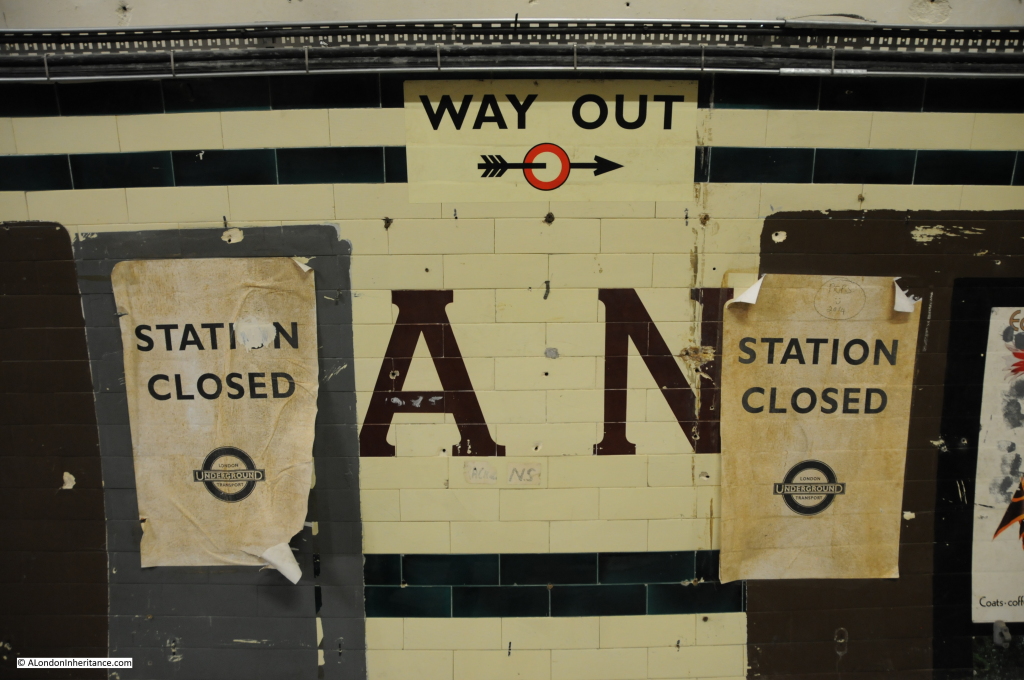

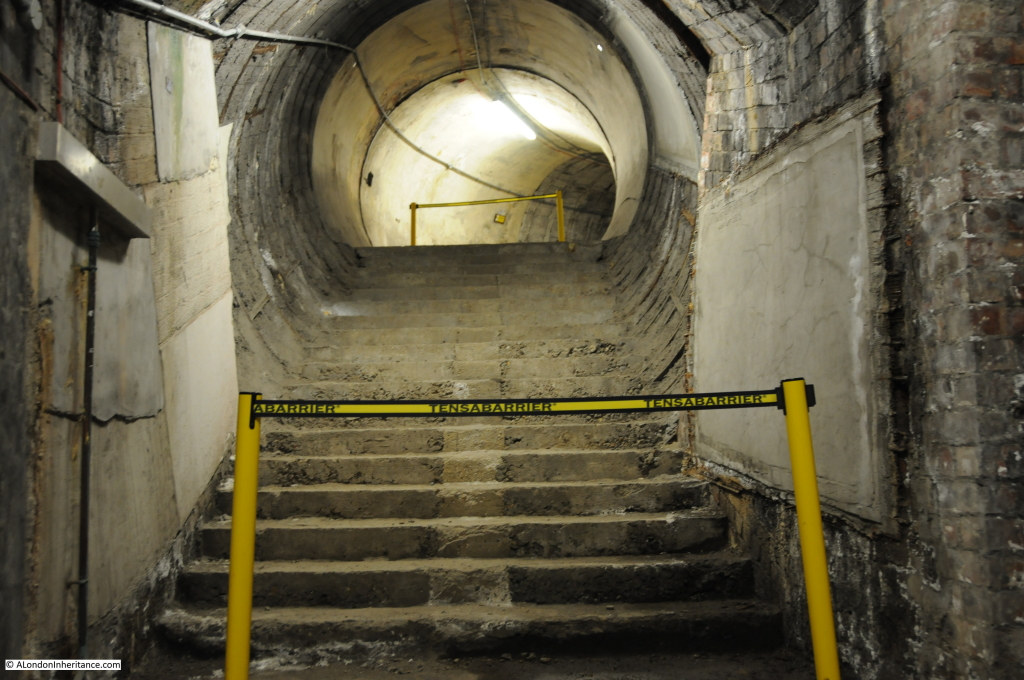

Improvements and upgrades were made to the original Spa Road Station, however around 1872 it was relocated to a new station built 200 yards to the east where new ticket offices had been built into the arches and steps from within the arches led up to the platforms. This new station operated until the 15th March 1915 when Spa Road was one of a number of stations closed due to war time economy measures and it was never to re-open.

The remains of this later station can still be seen in a small industrial area at the end of Priter Road.

The view from Priter Road looking directly at the arch that was once the Spa Road Booking Office:

The view along the arches. The Spa Road Booking Hall is in the arch just to the left of the white truck:

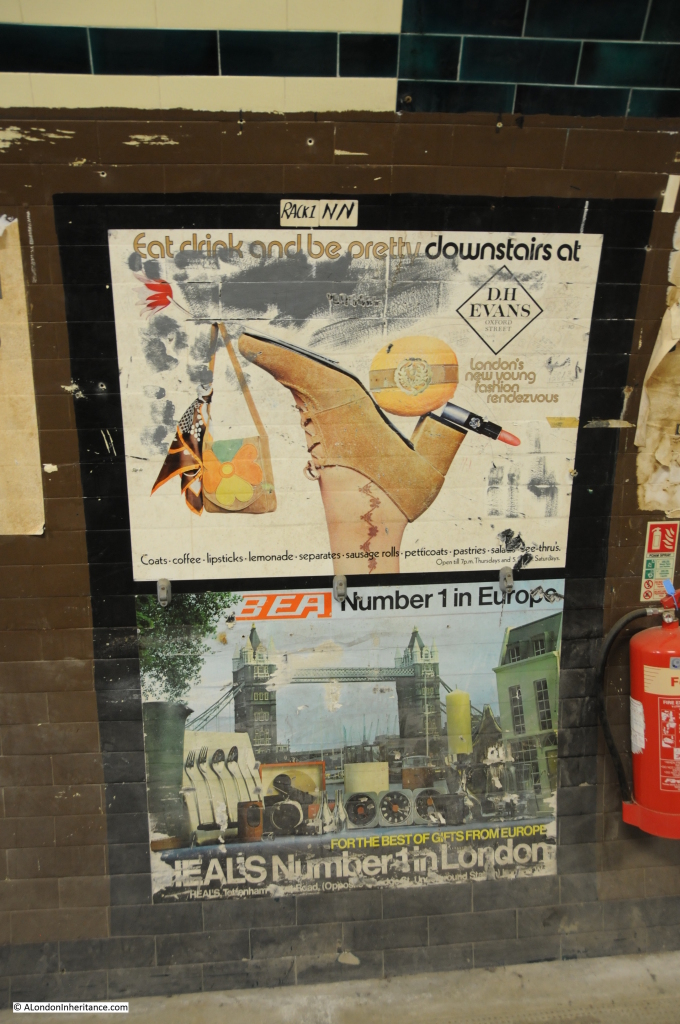

The booking office:

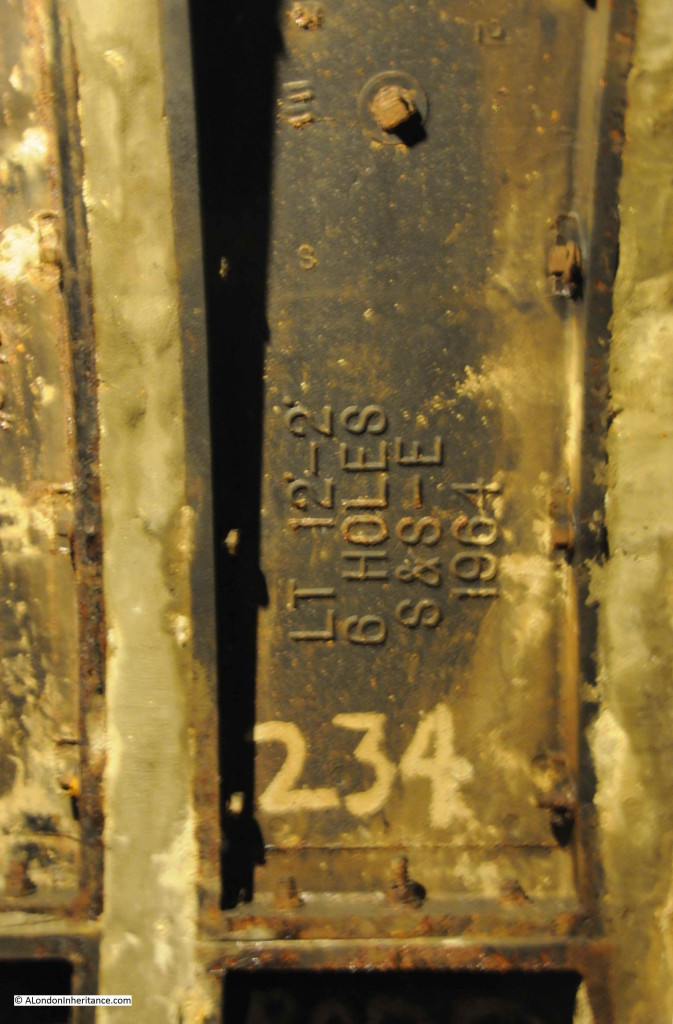

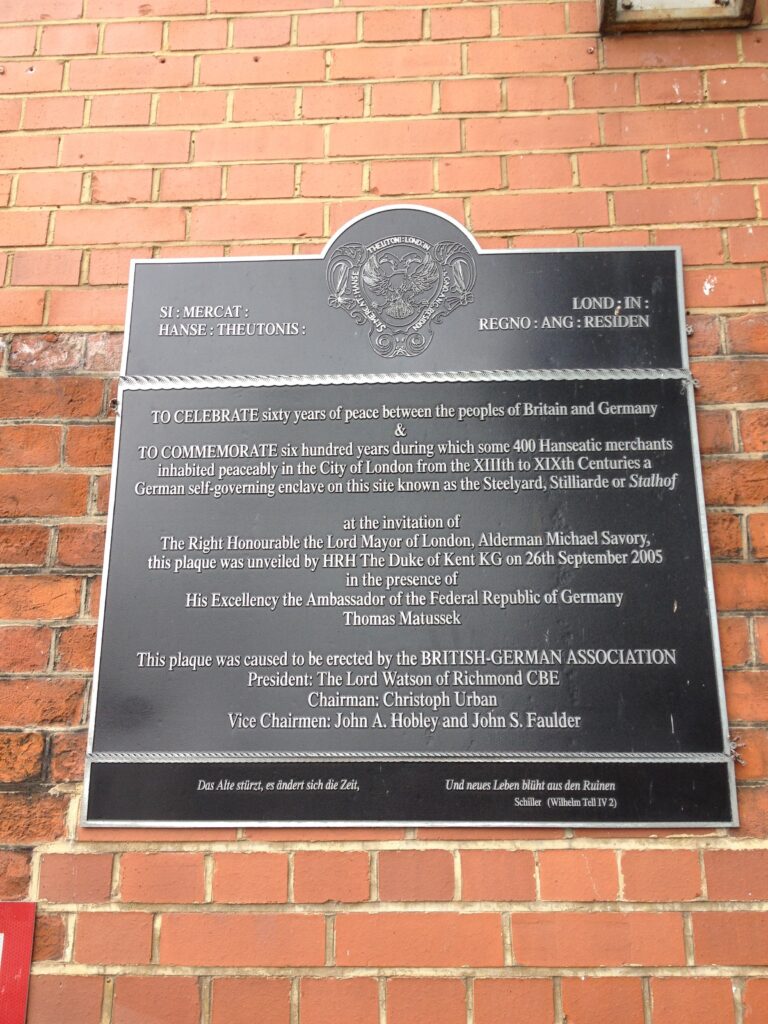

To the right of the Booking Office there are a couple of plaques recording the London and Greenwich Railway and Spa Road Station. Had to take the photo at an angle as a truck was parked directly in front.

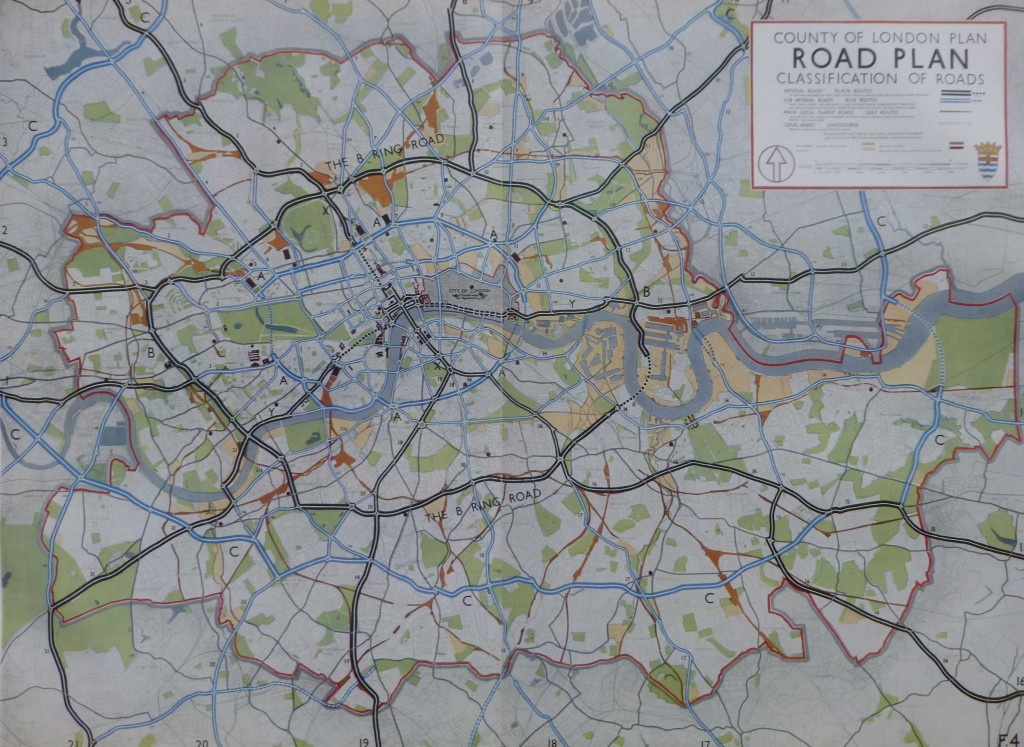

Soon after the viaduct was opened, other railway companies were formed to build and run additional routes out of London Bridge Station. Until these new lines branched off to their final destination, they used the viaduct built by the London and Greenwich Railway and paid a fee to the L&GR, usually based on a percentage of the ticket value.

One of the these was the South Eastern and Chatham Railway, formed in 1899 from the merger of the South Eastern Railway and the London, Chatham & Dover Railway. A couple of arches along from the booking office is another survivor from Spa Road station, with the initials of the South Eastern and Chatham Railway above the main entrance.

I have a postcard of the station when in use by the South Eastern and Chatham Railway., although I am not sure which of the two arches feature in the photo.

Above the arch are the initials SE&CR which are preserved on one of today’s arches, whilst on either side of these initials in the above postcard are the words Booking Office which feature on the other arch that remains today. There are no other clues as to which of the two arches is in the old photo, however it does show what the station looked like,

The view above the arches also shows the improvements at this second Spa Road Station.

The original station was made up of wooden staircases up the side of the viaduct leading to a narrow platform between the parapet and the tracks. The new station had wider platforms. station buildings and a roof above the platforms. The stairs leading to the platforms were also inside the viaduct. The space for the station on the viaduct was still limited, but it was a considerable improvement on the first station.

The two arches are in the photo below, although the arch with the words Booking Office is behind the wide truck:

The remains of the station on the viaduct can still be seen today. I have never been able to get a good photo from a train on the route, however the location of the station can be seen from the Shard.

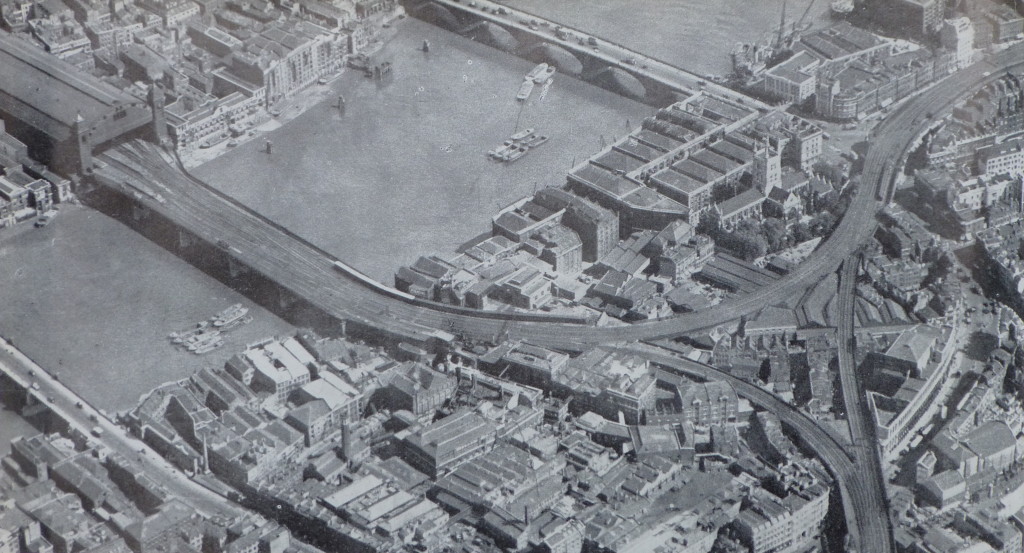

The following view shows the viaduct stretching out from London Bridge Station towards Deptford and Greenwich, and gives a good impression of the scale of the building work carried out in the 1830s by the London and Greenwich Railway. Follow the viaduct away from London Bridge and in the distance, a train can just be seen on the left of the viaduct.

Enlarging this section of the photo shows the location of Spa Road Station where the viaduct extends out to the left. The platform was in the middle of the two tracks:

The tower of St. James Bermondsey is on the left of the station, and the large buildings of the old Peek Frean biscuit factory are just to the upper left of the station. These provide a couple of good landmarks to locate the old station when on a train running along the viaduct.

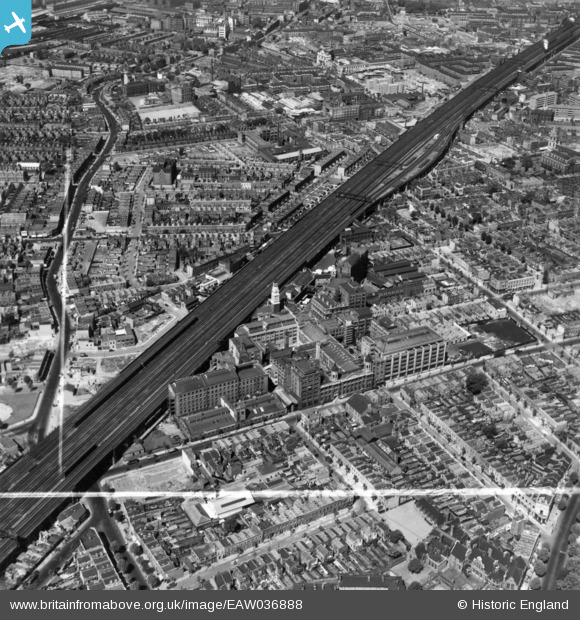

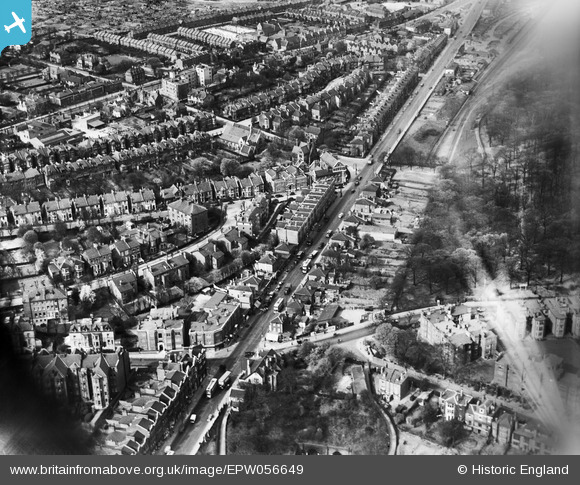

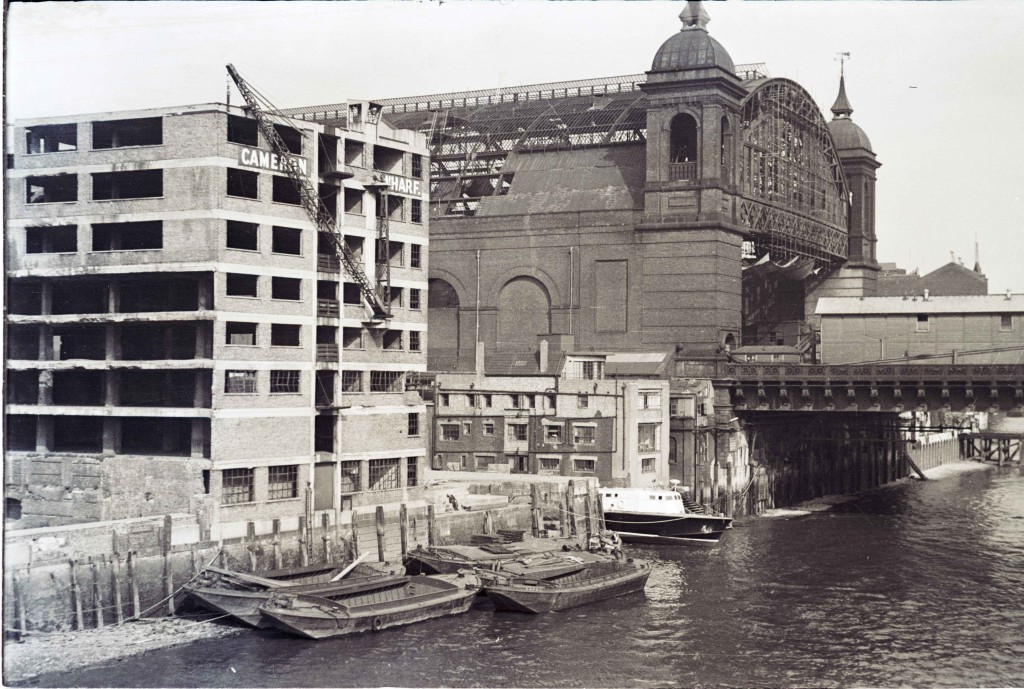

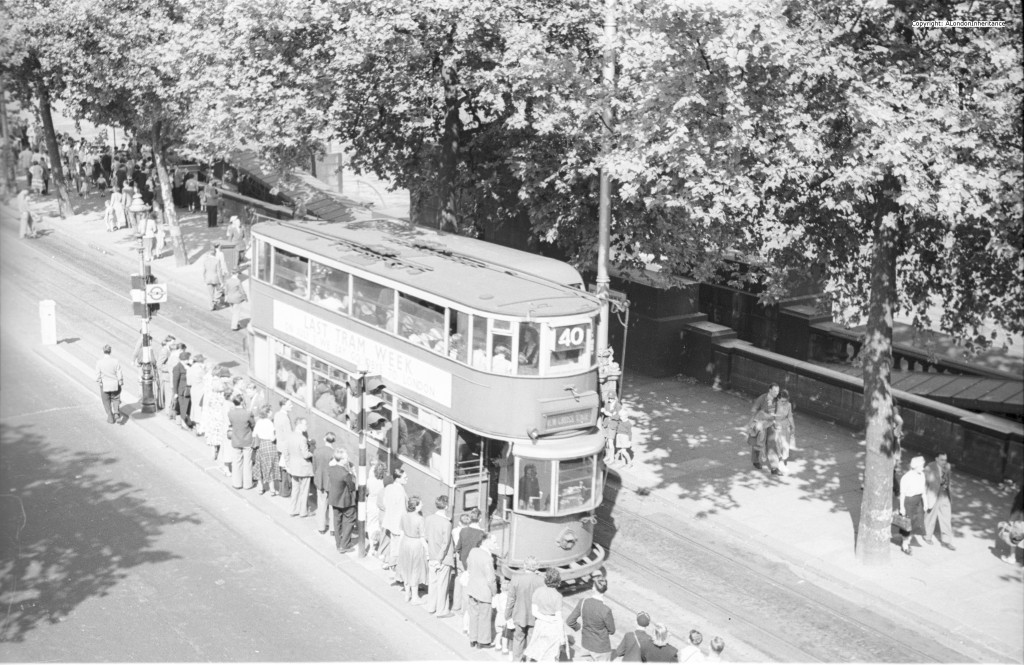

The remains of the station are also visible in these 1951 photos from Britain from Above:

Both photos also show the size of the Peek Freans biscuit factory which ran alongside the viaduct.

Whilst exploring Spa Road, I walked to some of the other streets passing through the viaduct. There are many of them, all different with features dictated by the places they connect, the type of streets that pass underneath and the architecture of the viaduct.

The number of streets cutting through the viaduct show that the use of a viaduct rather than ground level rail tracks was a superb bit of forward thinking. Despite the size of the viaduct, the frequency of streets passing underneath helps to ensure that the areas on either side are not separated. It all seems part of the same, connected place and instead of walking along open streets, part of the route is through a relatively short tunnel.

Had the London and Greenwich Railway been built at ground level, there would have been very few crossing points resulting in a distinct separation between either side of the tracks.

The wonderfully named Rail Sidings Road passing underneath the viaduct. Rail Sidings Road runs to Lucey Way which in turn runs parallel to the viaduct and alongside a housing estate. It is not a main through road and the tunnels on the right are now used for parked cars with only the tunnel on the left being open for traffic.

St. James’s Road tunnels passing underneath the viaduct:

Dockley Road passing underneath the viaduct, with a Monmouth Coffee Shop in one of the arches:

Whilst walking through these few tunnels I started to have thoughts about a project to photo all the tunnels between London Bridge and Greenwich – I need to take this less seriously !!

Adjacent to the St. James’s Road tunnel is Clements Road. Running from Clements Road. Parallel to the viaduct is a narrow paved road. When the original viaduct was built, construction included a roadway and footpath alongside the length of the viaduct and the L&GR charged a toll for the use of these. I have no idea whether this is true, however it would be good to think that this cobbled roadway is part of the original road from when the viaduct was built.

On the junction of Rail Sidings Road and St. James’s Road is the pub St. James of Bermondsey, formerly the St. James Tavern, a Victorian pub dating from 1869.

I also walked along Clements Road to take a look at a major landmark in the area, the old Peek Freans biscuit factory.

The Peek Freans factory was part of the development of Bermondsey from the open country shown in the maps earlier in this post to the densely built area of today. The factory was built on 10 acres of former market gardens adjacent to the viaduct which were purchased in 1866.

The factory closed in 1989, and has since provided space for a number of small businesses, however will soon be the subject of a major redevelopment.

One of the old factory entrances:

There is one of the usual artists impressions of the future development cabled tied to the metal fencing around the old factory. The usual view of these future developments where the sky is always blue, it is always summer and where no one over the age of forty or fifty would apparently ever be seen.

To be fair to the developers, the small print in the bottom right corner does state “Indicative computer generated image” so it may look completely different when finished (as these developments often do).

There is so much more to explore here, but this post is getting too long. For a final photo, I found this Bermondsey Book Stop at the junction of Webster Road and Clements Road, opposite one of the entrances to the old Peak Freans factory with quotes from Pride and Prejudice and Tristram Shandy on the doors. A brilliant initiative.

Spa Road Station has now been closed for over 100 years, however the place where the viaduct passes over Spa Road will always be the first railway terminus in London and the viaduct will continue to support many more trains and passengers than the original founders of the London & Greenwich Railway can ever have imagined.

I have only covered the very first years of the construction of the viaduct. As soon as the viaduct was under construction there were many proposals for additional routes and extension of the railway onwards to Gravesend and Dover.

There was even a serious proposal at one stage to extend the viaduct across Greenwich Park, however fortunately this scheme was turned down in favour of the tunnel that was built underneath the land between the Queen’s House and the old Royal Naval College.

If you travel on the railway, look out towards the north when the old biscuit factory comes into view or the tower of St. James Church and you may catch a glimpse of the remains of Spa Road Station.