Last weekend I was walking in Chelsea, hunting down some of the locations of my father’s photos when I walked past one of the places I have always meant to visit.

If you walk or drive along the Chelsea Embankment, in-between the rows of apartment buildings that face onto the embankment you will see a low brick wall with a slightly ornate entrance gate, with what appears to be gardens behind.

This is the Chelsea Physic Garden.

The main entrance to the Chelsea Physic Garden is on Swan Walk, which when facing the Gardens from the river forms the eastern boundary. A plaque in the brick wall adjacent to the entrance provides an indication of the function and the age of the Gardens:

The main entrance is a relatively small gate in Swan Walk:

Once through the gate and having paid the entrance fee, the Gardens open up. Hard to believe that this is Chelsea and that the traffic on the Chelsea Embankment and the River Thames is just beyond the trees at the far end of the following photo:

The Chelsea Physic Garden was established in 1673 by the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries when the land was leased from Charles Cheyne, the Lord of the Manor of Chelsea. It has continued to occupy the same location adjacent to the River Thames, whilst the rest of Chelsea has been developed around the gardens.

The Apothecaries needed an area where medicinal herbs could be grown and apprentices to the Society could be trained in their use. The Society had acquired a Medical Garden at Westminster prior to Chelsea and it was the contents of this garden that were moved to Chelsea.

The location chosen in Chelsea was ideal. It was south-facing, fertile and directly adjacent to the river (the Chelsea Embankment had not yet been built) as the river provided easy and safe access to central London rather than cross the dangerous fields and marshes that extended east at this time.

In London Old and New, Edward Walford writes:

“The Physic Garden to which we now come, was originated by Sir Hans Sloane, the celebrated physician, and was handed over in 1721 by him, by deed of gift, to the Apothecaries Company, who still own and maintain it. The garden, which bears the name of the Royal Botanic, was presented to the above company on condition that it should at all times be continued as a physic-garden, for the manifestation of the power and wisdom, and goodness of God, in creation; and that the apprentices might learn to distinguish good and useful plants from hurtful ones. Various additions have been made to the Physic Garden at different periods in the way of greenhouses and hot-houses; and in the centre of the principal walk was erected a statue of Sir Hans Sloane, by Michael Rysbraeck.”

Walford gives the impression that Sir Hans Sloane created the Chelsea Physic Garden, however it was already in existence and Sloane had been an apprentice at the Garden. After Sloane had made his fortune (more on this in a later post on Chelsea), he purchased the Manor of Chelsea from Cheyne and granted a perpetual rent of the Garden to the Apothecaries for a peppercorn rent of £5 a year.

The Chelsea Physic Garden has not always looked as good as it does now. From “London Exhibited in 1851”:

“At the time the garden was formed, it must have stood entirely lying in the country, and had every chance of the plants in it maintaining a healthy state. Now, however, it is completely in the town, and but for its being on the side of the river and lying open on that quarter, it would be altogether surrounded with common streets and houses. As it is, the appearance of the walls, grass, plants and houses is very much that of most London gardens – dingy, smokey, and as regards the plants, impoverished and starved. It is however, interesting for its age, for the few old specimens it contains, for the medical plants, and especially because the houses are being gradually renovated and collections of ornamental plants, as well as those which are useful in medicine, formed and cultivated on the best principles, under the Curatorship of Mr Thomas Moore, one of the editors of the Gardeners Magazine of Botany. In spite of the disadvantages of its situation, here are still grown very many of the drugs which figure in the London Pharmacopoeia.”

From inside the garden we can see the gates that face onto the Chelsea Embankment. These gates and the upgraded enclosure of the gardens was completed in 1877 when Mr Thomas Moore, mentioned in the above quote, was the Curator. (As evidence of the scientific principles underlying the gardens, the Curator is effectively the Head Gardener, but with the responsibly to curate the collection of plants held by the garden.)

A the top of the gates is the badge of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries in London:

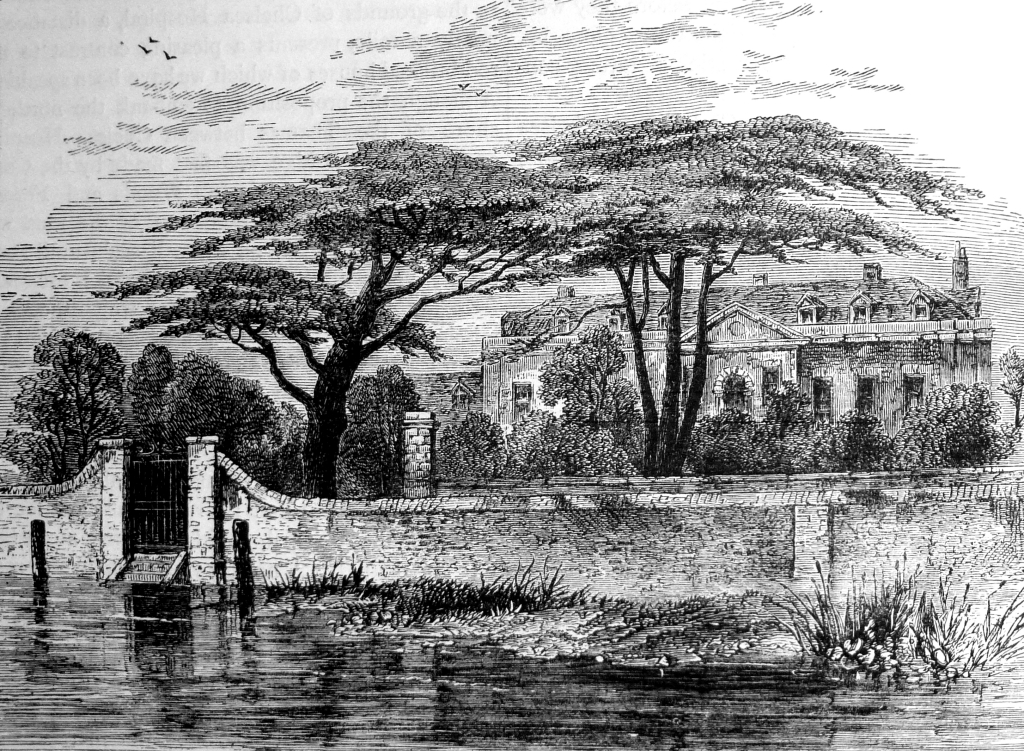

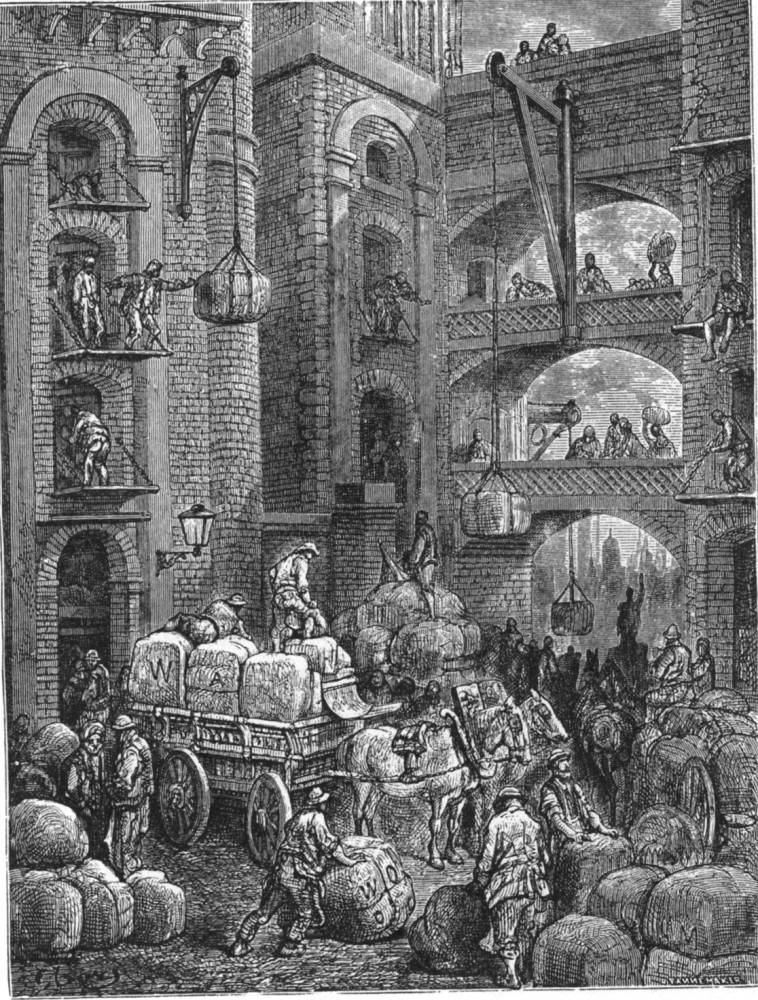

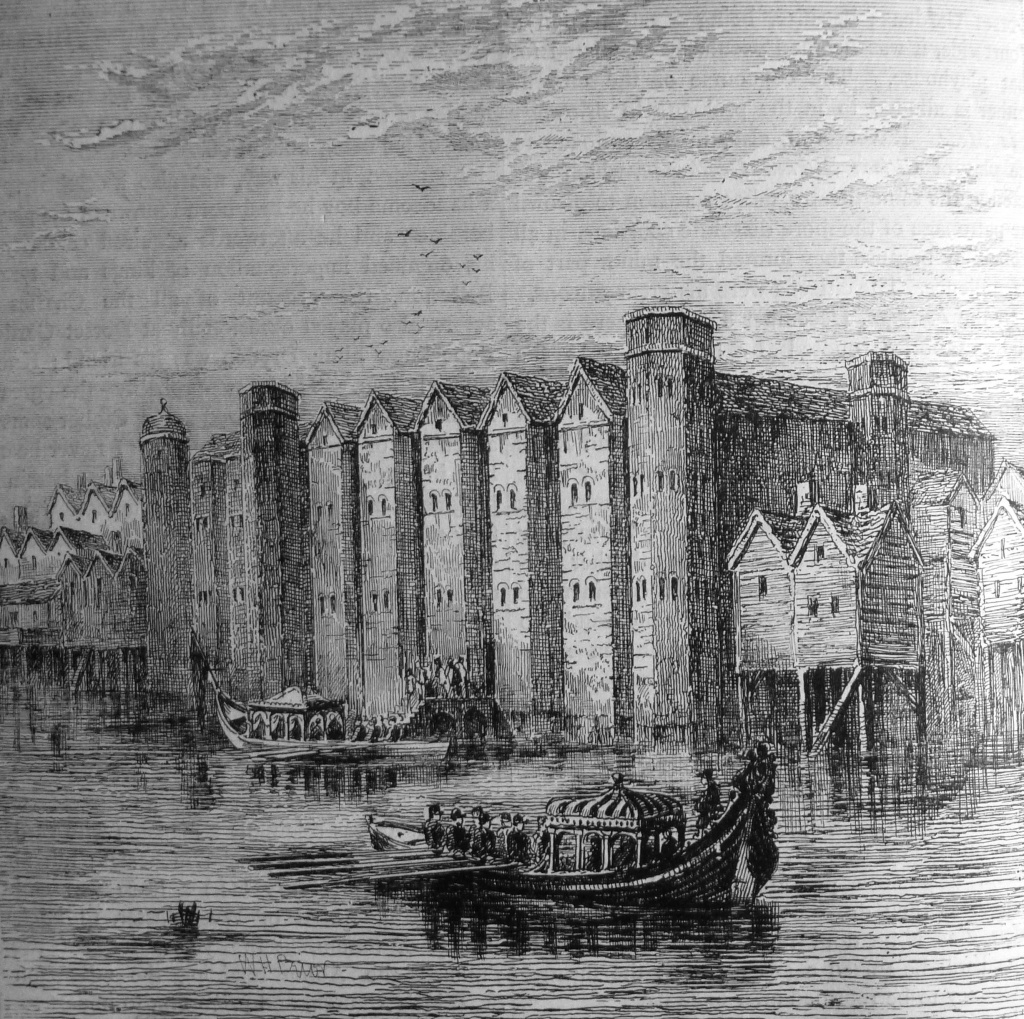

The following engraving from London Old And New shows the gardens in 1790 with the original wall and gates directly onto the River Thames before the construction of the Thames Embankment.

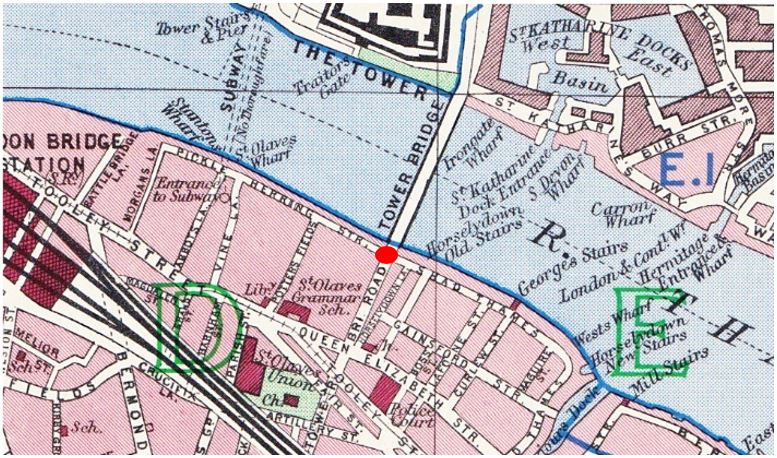

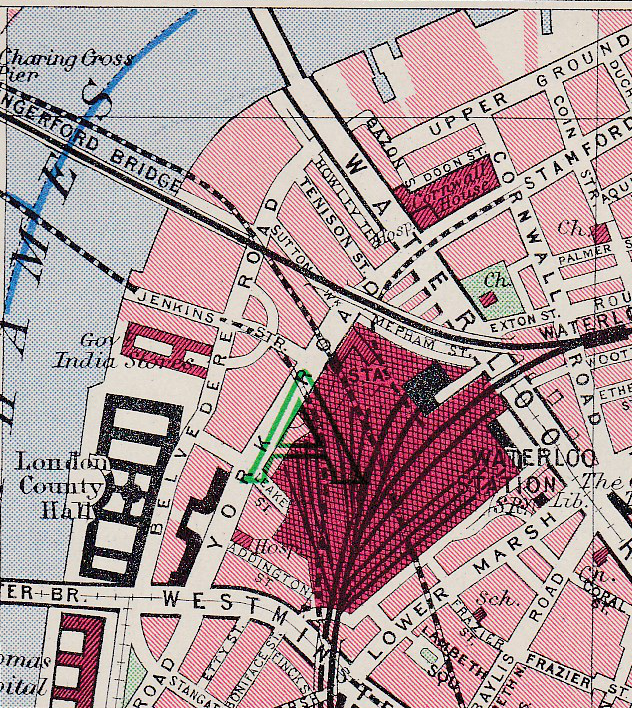

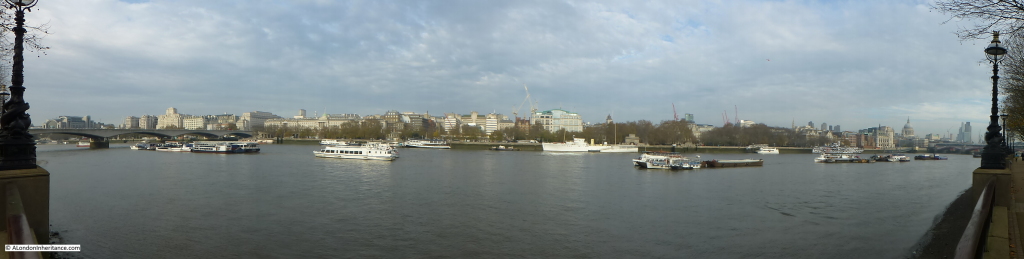

The following map extract from the early 1830s shows the Botanic Gardens between Coal Wharf and the Swan Brewery facing directly onto the river, as did Cheyne Walk prior to the construction of the Chelsea Embankment.

The statue to Sir Hans Sloane has pride of place in the centre of the gardens. This in not the original 1733 Michael Rysbrack statue, the original was damaged by pollution and is now in the British Museum. The current statue is a replica of the original.

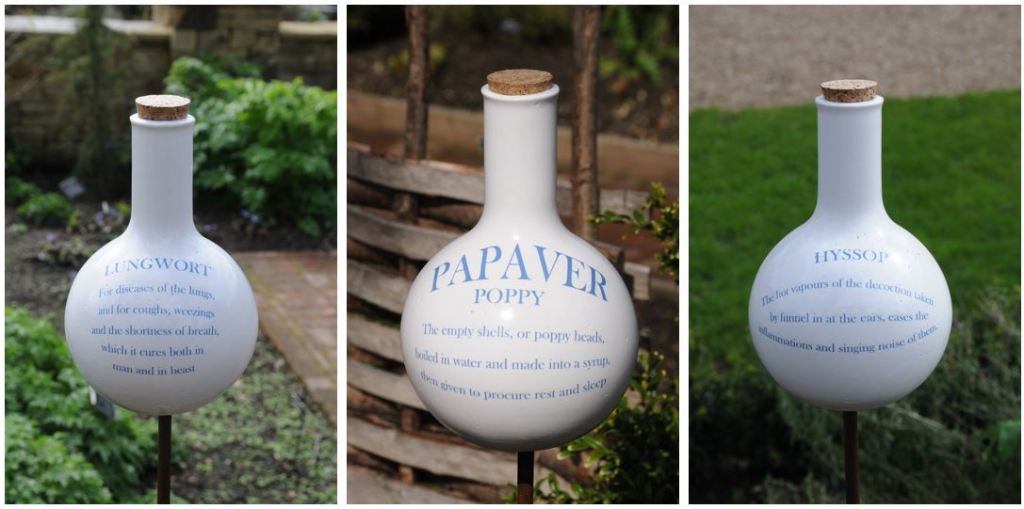

Visiting the garden now provides an excellent learning experience. The plants are very well labelled with several themed areas to focus on specific geographical sources of plants. There is also currently an art installation by Nici Ruggiero which uses jars in the style of those used by early Apothecaries to explain how different plants were and are used in medicine.

Jars are placed on stakes in the gardens:

As well as a rack of jars against one of the boundary walls:

If you did not know that Lungwort is for diseases of the lungs and for coughs, weezings and the shortness of breath, which it cures both in man and in beast, or that Golden Rod cures conditions of jaundice and provokes urine in abundance, then this is the place to learn.

The Chelsea Physic Garden was also one of the first in Europe to have a glass / hot house, and in 1685 the diarist John Evelyn described a visit to the garden where he met Mr Watts, keeper of the Garden and saw the heated glass house. He wrote in his diary: “what was very ingenious was the subterraneous heat, conveyed by a stove under the conservatory, all vaulted with brick, so as he has the doores and windowes open in the hardest frosts, secluding only the snow.”

The gardens to this day have a number of heated glass houses that support plants from tropical locations that would not otherwise thrive in a London climate:

And they work well in promoting abundant growth:

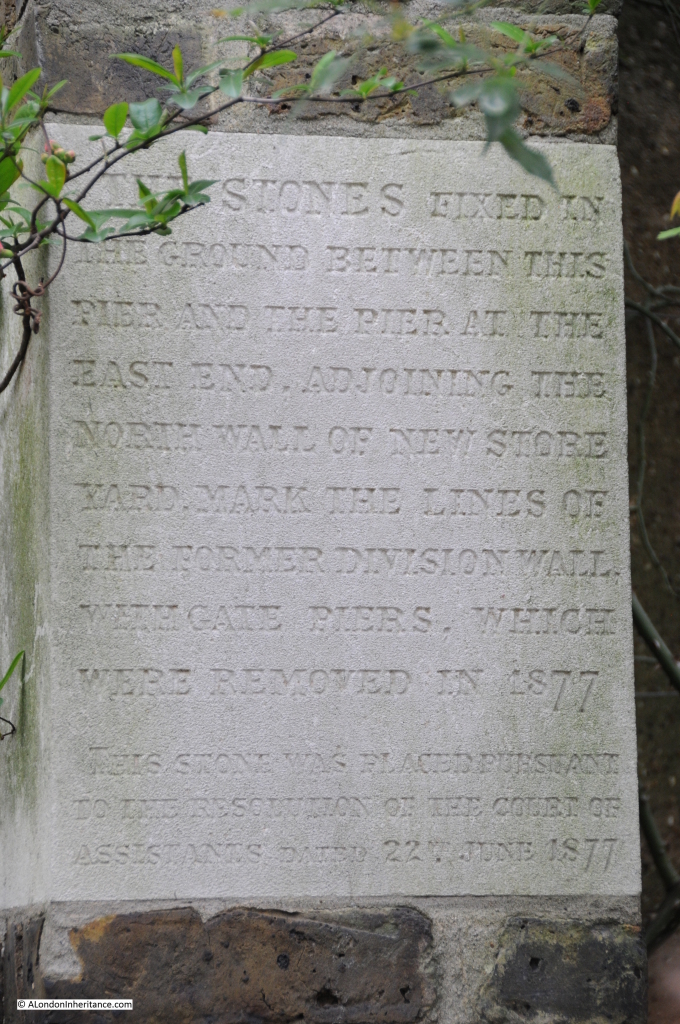

At the Chelsea Embankment edge of the gardens, it is still possible to find hidden on the side walls, stones fixed to mark the original division walls:

The gardens experienced mixed fortunes in the later half of the 19th century. The numbers of visiting medical students rose significantly in 1877 from a couple of hundred to 3,500 due mainly to the Society of Apothecaries finally allowing women to the study of medicine, but by the end of the 19th century the study of plants had been dropped from the medical syllabus and the Society of Apothecaries decided that there was no real need to continue with the garden.

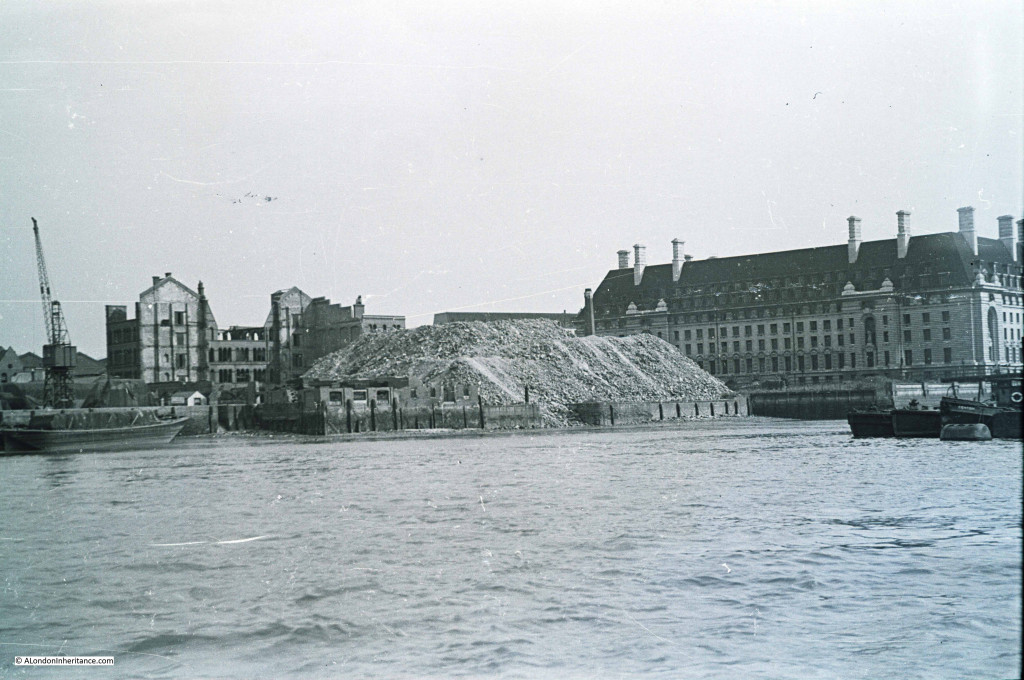

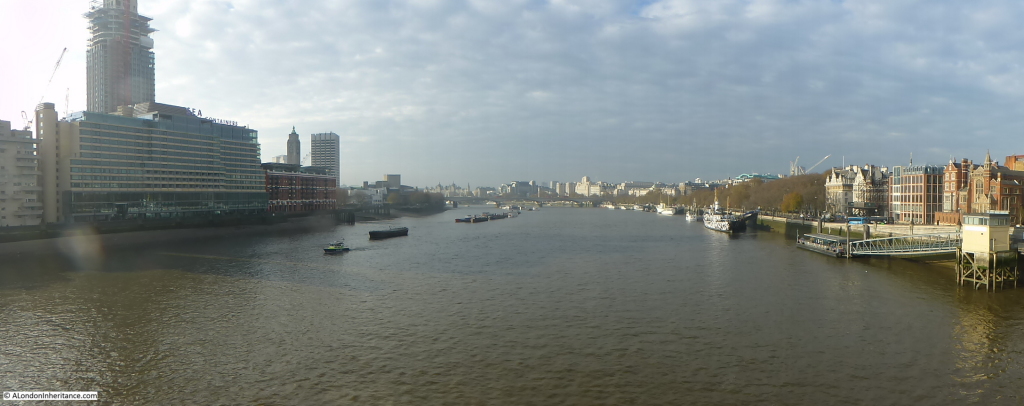

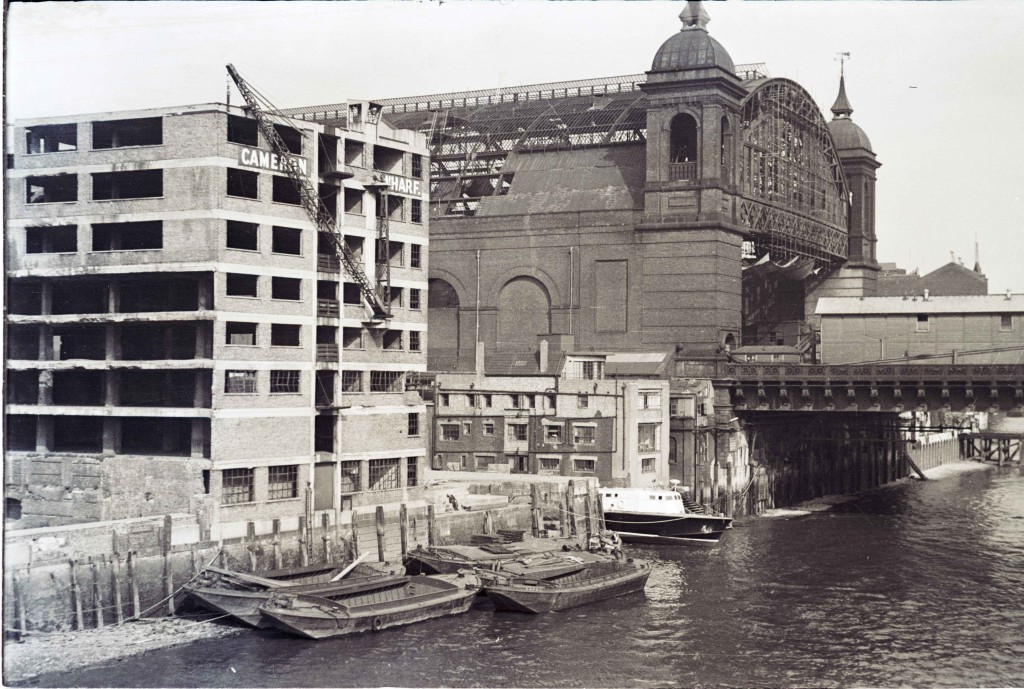

The gardens also suffered from the construction of the Chelsea Embankment in 1876, cutting of what had been a riverside garden from the river.

The gardens were taken on by the City Parochial Foundation. From the history of the Foundation by Victor Belcher:

“The first additional long term obligation taken on by the Foundation was the maintenance of the Chelsea Physic Garden. By the 1890s the Company had decided that it could no longer afford the upkeep of the garden and recommended that the site should be sold and the proceeds used to endow scientific research and teaching. Widespread concern was voiced and a departmental committee was appointed by the Treasury to look into the situation. In 1898, W. H. Fisher (later Lord Downham), a trustee who also happened to be a Junior Lord of the Treasury in Lord Salisbury’s government, introduced a motion before the Central Governing Body urging the trustees to take over the garden from the Apothecaries Company. he stressed its importance as an open space and as a source of botanical study for students at the Battersea and South-Western polytechnics. The trustees were convinced and asked the Charity Commissioners to draw up a scheme. This was published in 1899 and required the Foundation to give an annual grant of £800 to the garden. the government provided a small supplementary grant, but from this time the Chelsea Physic Garden was essentially the Foundation’s responsibility, a state of affairs which was reflected in the composition of the garden’s managing committee, over half of whose members were to be appointed by the Foundation.”

(The City Parochial Foundation is one of the many bodies that have had an impact on the development of London. Formed in 1891 by bringing together a range of endowments so as to be under the control of a single corporate body, the Foundation was charged with helping the poor of London mainly through creating and supporting technical education in the form of the polytechnic movement)

It was good fortune that the Chelsea Physic Garden was saved otherwise it would now be just more Chelsea streets and buildings.

The City Parochial Foundation continued to support and provide grants to the gardens. By the early 1920s the original £800 per annum grant had grown to £2000.

The grant was reduced during the 2nd World War as the gardens were placed on a care and maintenance status, with several plants being moved to Kew due to damage by bombing. After the war the Foundation was responsible for repairs and redecoration to the gardens and buildings.

The end of the association between the City Parochial Foundation and the Chelsea Physic Garden started in the 1970s, again from the history of the Foundation:

“By the mid-1970s the trustees were becoming concerned about both the rising cost of repairs and the amount of grant now needed. There was also a nagging doubt, once the connections with the polytechnics had been severed, whether the Physic Garden could be said to serve the purposes of the Foundation any longer, if indeed it ever had done. The sub-committee which was appointed to prepare a policy for the quinquennium 1977-81 was asked to include the future of the Garden in its deliberations. It recommended that funds should be made available for the modernisation of the Garden, but that the Charity Commissioners should be informed that the Foundation wished to withdraw further financial support. In the meantime the trustees would actively seek another sponsor.

Finally, in 1981 a new and independent body of trustees agreed to take over the Garden, and in return were promised grants totalling £200,000 to meet the estimated running costs over the next four years. A new scheme was published, and the formal transfer took place on 1 April 1983 when the Foundation’s scheme grant came to an end.”

Along with the new status of the Chelsea Physic Garden, it was also formally opened to the public, and this continues to be the status of the gardens today with a small, independent charity responsible for the running of the gardens, and the associated educational work carried out to this day.

During their development, the gardens benefited from a constant stream of new discoveries from across the world. the 18th and 19th centuries were a time of botanical discoveries with expeditions being sent to all corners of the world to bring back specimens.

Among those who contributed to the garden was Joseph Banks, who had already made expeditions to Newfoundland and Labrador and was part of Captain Cook’s voyage to South America, the Pacific, Australia and New Zealand. It was through his role as President of the Royal Society that Banks supported expeditions around the world to bring back specimens for the Chelsea Physic Garden. Banks was elected as President in 1778 and held the post for 41 years

Curators were also major plant hunters. One such being Robert Fortune who was curator from 1846 to 1848. He was a prominent plant hunter who brought back many samples from Asia.

Insect houses up against the boundary wall with the Chelsea Embankment.

It has not really been possible to do justice to the history of the Chelsea Physic Garden in the space of a weekly blog post, however I hope this provides some background and an incentive to visit another example of the history of this fascinating city.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- The Face of London by Harold P. Clunn published in 1951

- Old And New London by Edward Walford published in 1878

- The City Parochial Foundation 1891 – 1991 by Victor Belcher published in 1991

- London: The Western Reaches by Godfrey James published in 1950

- The history of the gardens on the Chelsea Physic Garden web site which can be found here