If you walk to the southern end of Blackfriars Bridge, on the eastern side of the bridge there is a small garden, and it is a perfect example of how places in London can tell multiple stories, and for the garden the story is of the engineer John Rennie, the Albion Mill, a unique view of London, as well as the price of grain and flour in London.

This is Rennie Garden alongside the path that runs up to, and along the eastern side of Blackfriars Bridge:

This is a very small garden and consists of a few trees and two blocks of planting:

Which really look good, and bring a splash of colour on a sunny May morning:

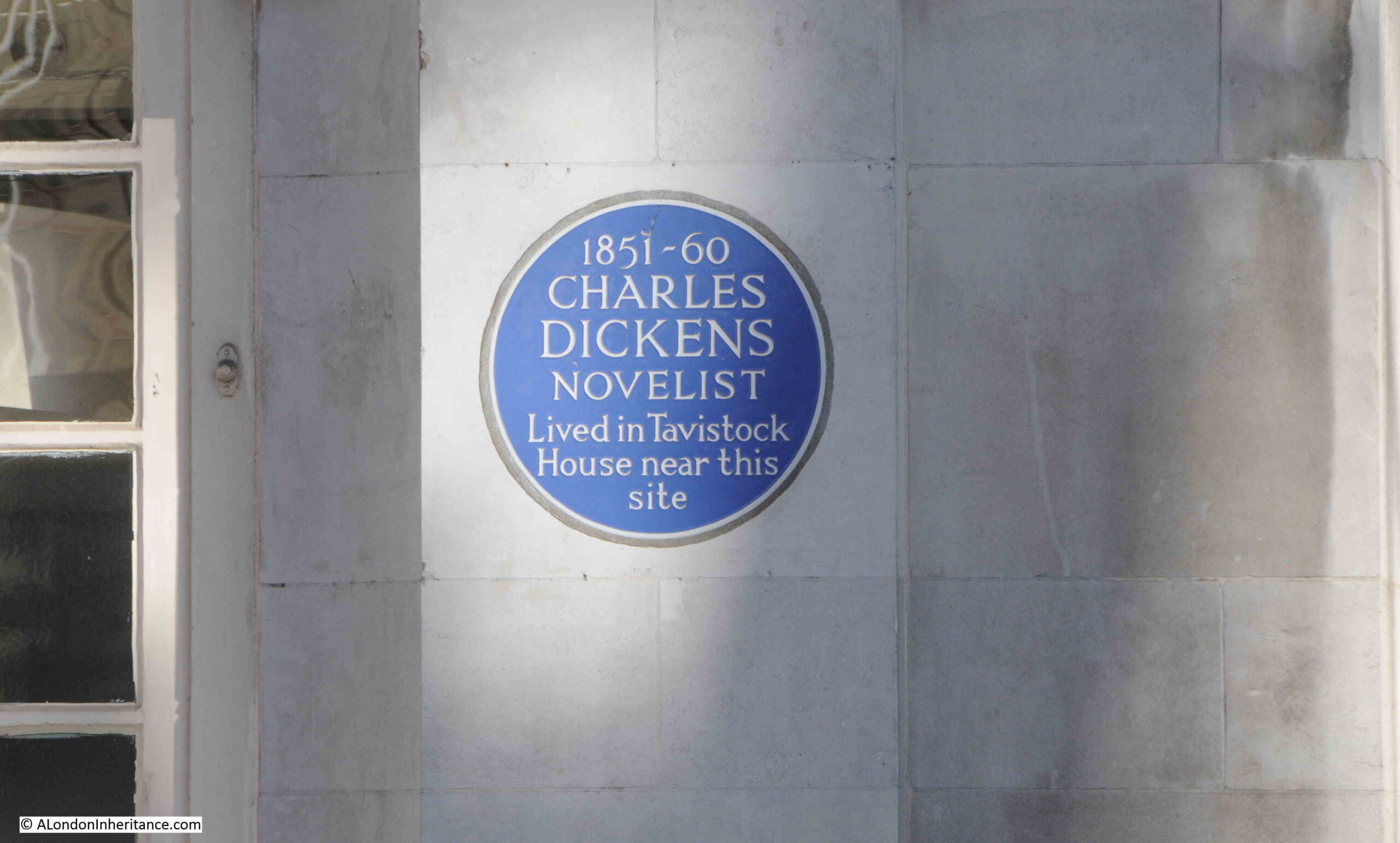

The gardens were created in 1862 by the Corporation of London and named the Rennie Garden after the engineer John Rennie.

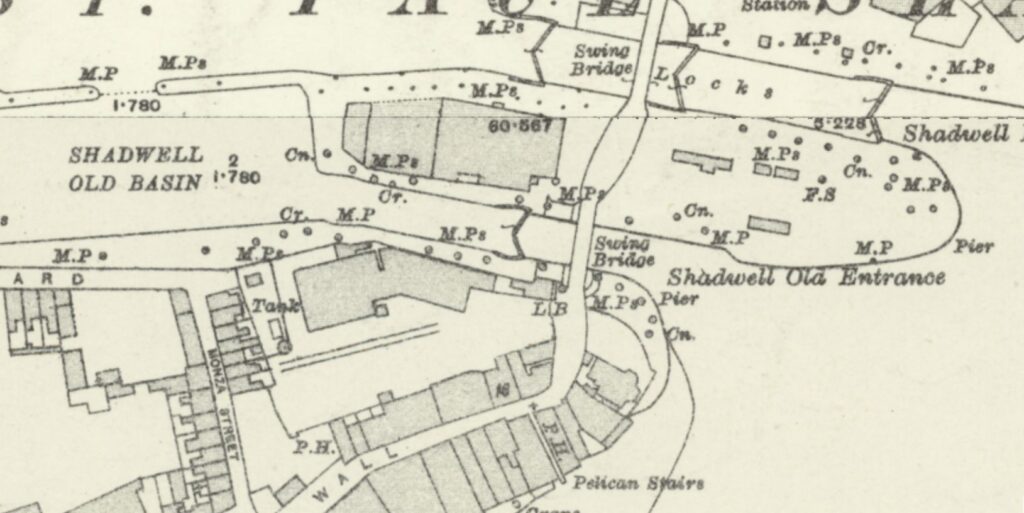

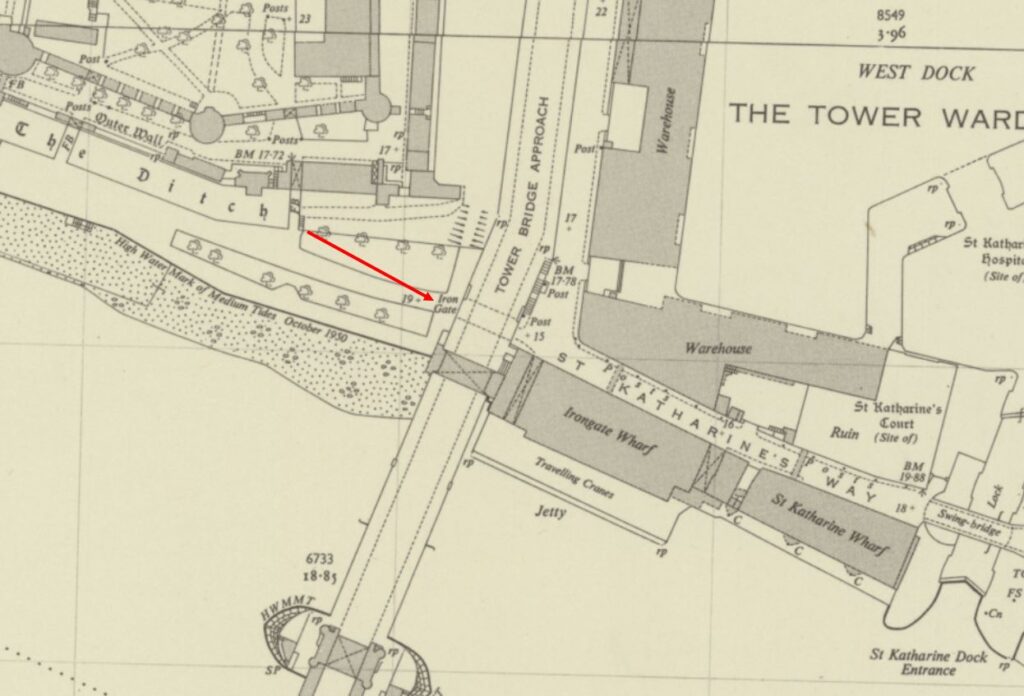

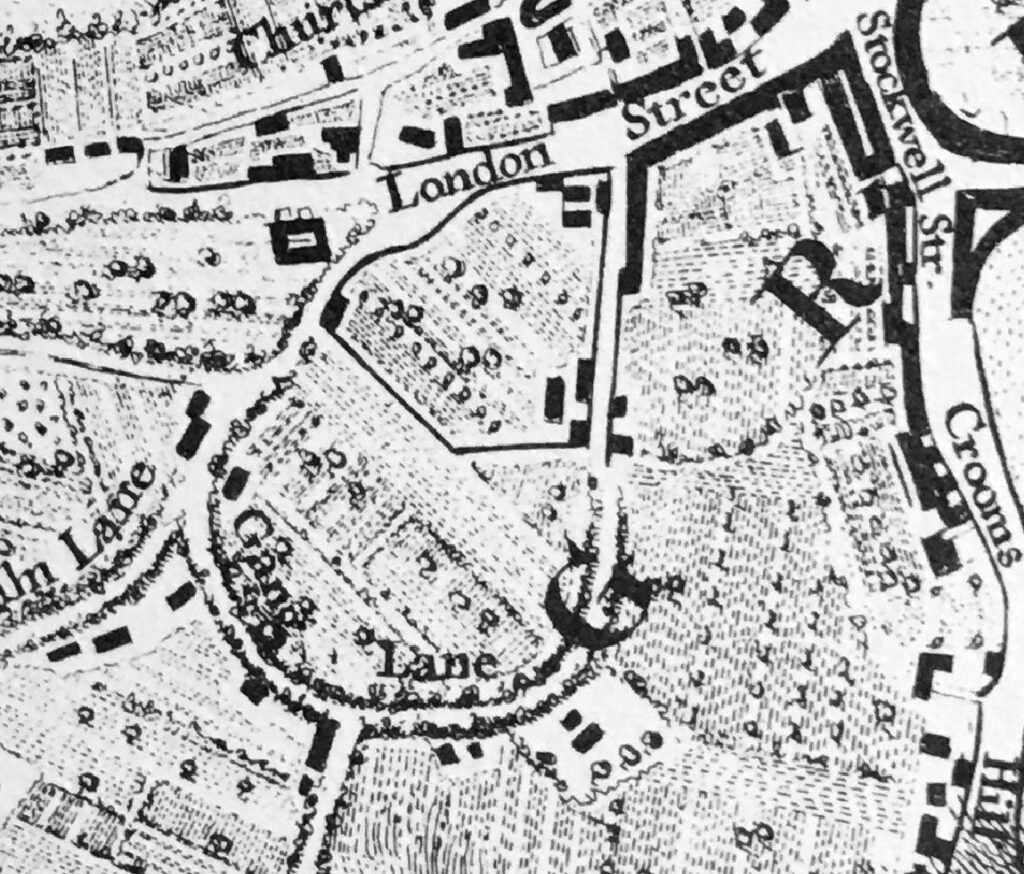

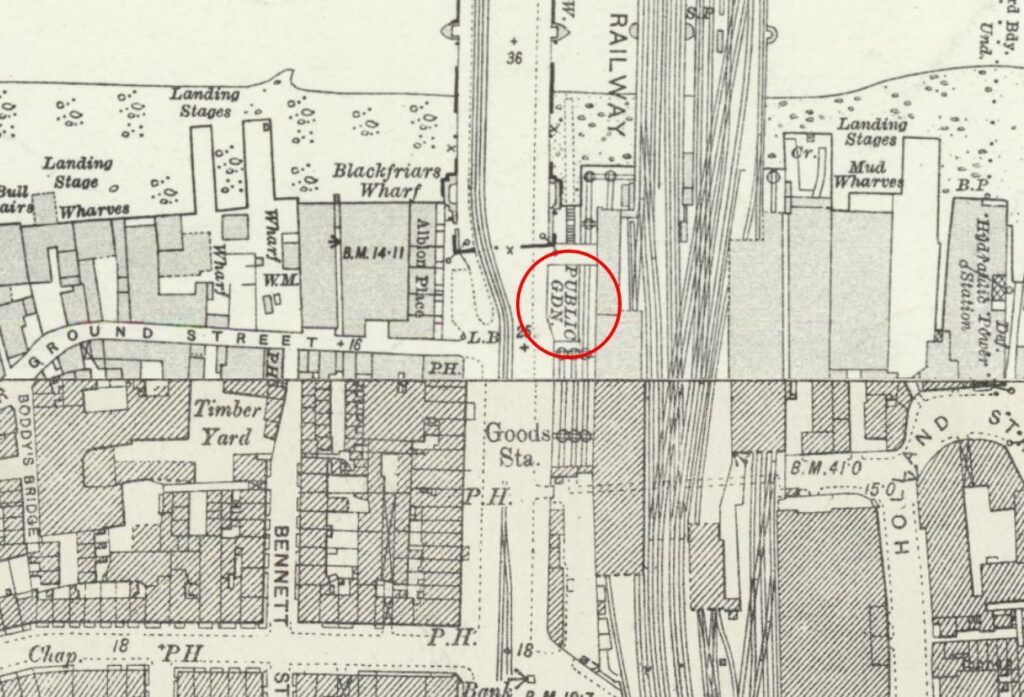

The following extract from the 1894 edition of the Ordnance Survey map shows the gardens (ringed in red), as a very small patch of public gardens squashed between the railway and the road, both of which were running on to the bridges which crossed the Thames (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland“):

In the above map, some stairs can be seen running down to the foreshore from the north of the gardens. The stairs are still there today, however they now lead down to the walkway along the side of the river:

There are though stairs on the other side of the river wall which lead down to the foreshore. This is not a historic set of stairs and they seem to have been built around the same time as the bridge.

So why are the gardens named after John Rennie, and what is the connection with a mill, the price of flour and a view of London?

John Rennie was the architect of London Bridge (the version of the bridge that was later demolished and moved to Arizona in the US). After Rennie’s death in 1821, the bridge was built by his son, also named John, who continued his father’s practice as a civil engineer.

According to “A Biographical Dictionary of English Architects” by H.M. Colvin, (1954), John Rennie (1761 to 1821) “was the younger son of a Scottish farmer, and was born in Phantassie in East Lothian on June 7th, 1761. As a child he showed a remarkable aptitude for mechanical pursuits, and he afterwards found congenial employment with a millwright. His earnings enabled him to study at Edinburgh University for three years before establishing himself as a millwright and general engineer. In 1784 he went to Birmingham in order to assist Boulton and Watt in designing and executing the machinery for the Albion Flour Mill ay Southwark”.

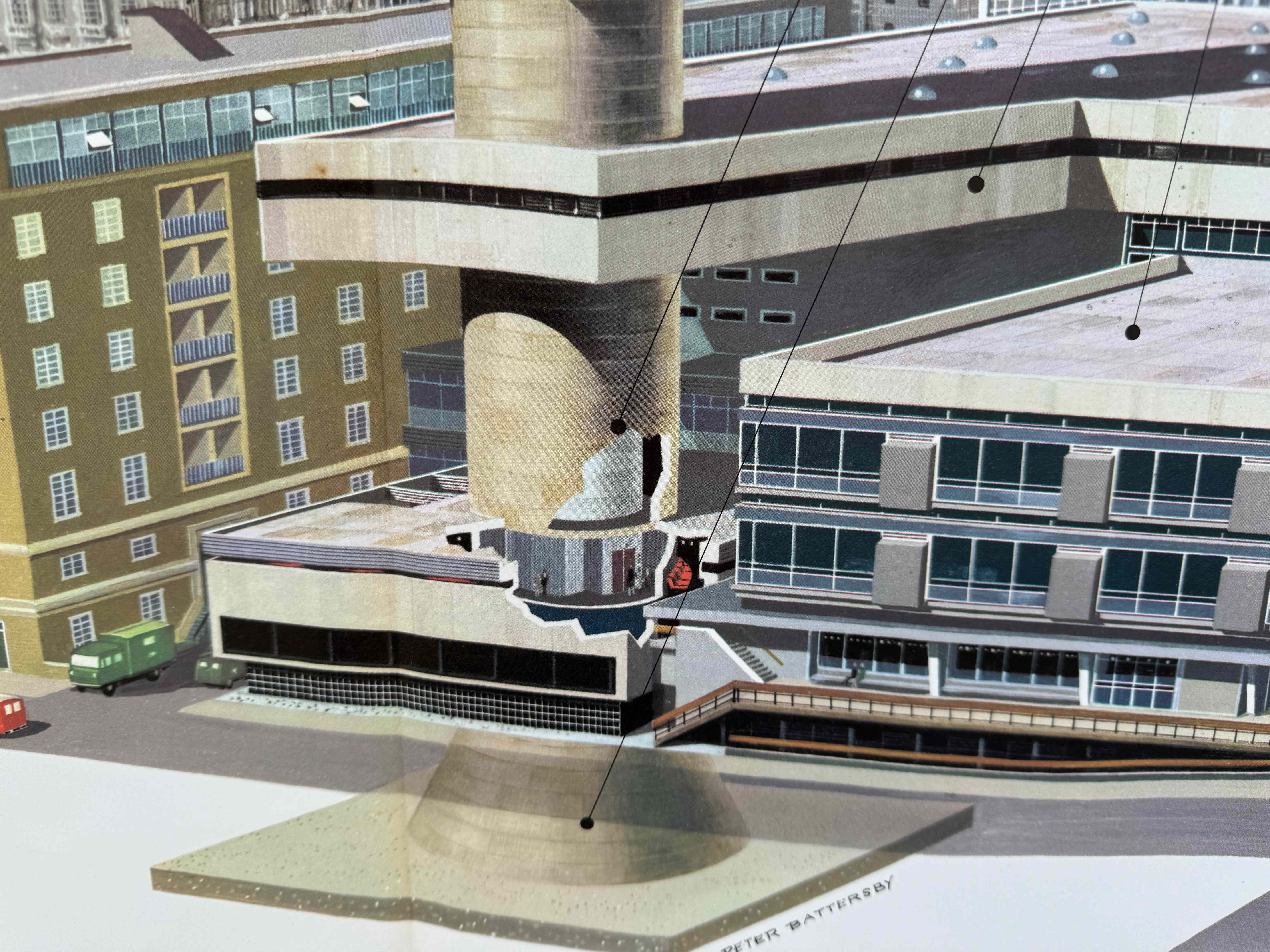

And that is the connection between John Rennie and the gardens, as they are on part of the site of the Albion Flour Mill, the first steam powered flour mill in London and at the time of completion, the largest in the world.

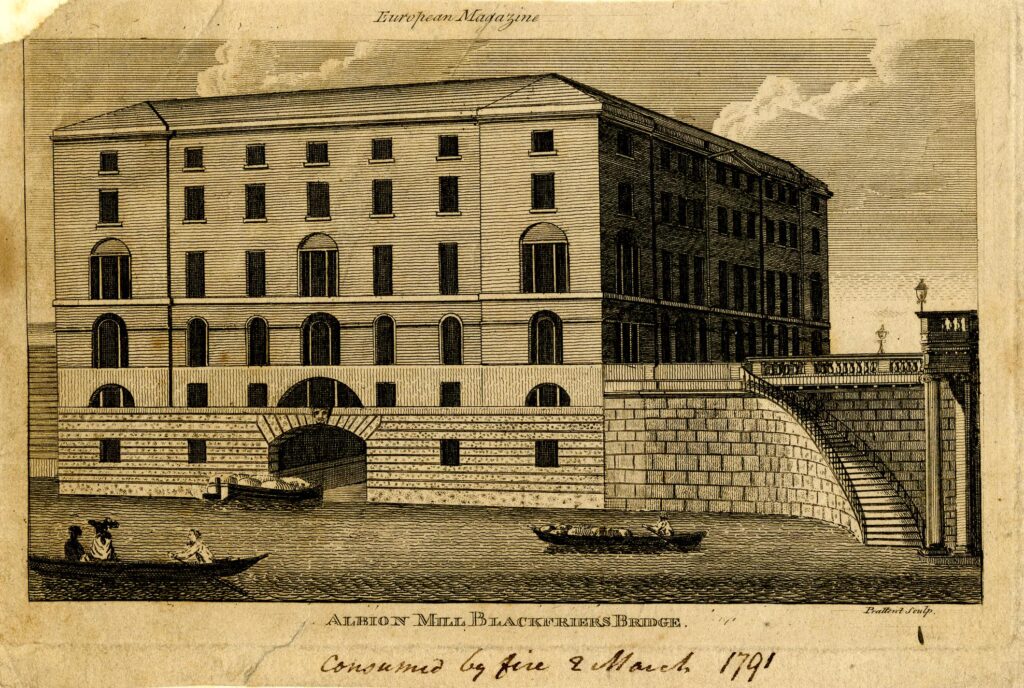

The Albion Flour Mill, Blackfriars Bridge is shown in the following print, with the edge of the bridge (the version before the Blackfriars Bridge we see today) at the right edge of the print:

Before the Albion Mill, there had been a number of much smaller mills scattered across London and the counties surrounding the city, using a range of power sources such as wind and water.

The introduction of steam power rendered all these other mills redundant as the Albion Mill could process large quantities of grain with a reduced level of manpower. Being next to the river enabled both coal and grain to be delivered directly to the mill.

Newspapers reported on the opening of the Albion Mill, and the following from the 10th of April 1786 is typical “A few days since the Albion Mill, on the Surrey side of Blackfriars Bridge, commenced working. This mill, the largest in the world, has been erected by the proprietors for the beneficent and salutary purpose of supplying this great metropolis with flour, and of course reducing the price of bread, the greatest blessing the poor can experience on this earth. The machinery is worked by the operation of steam, and we are happy to say, there is every reason to expect it will amply fulfil the intent, and fully reward the ingenuity and public spirit of those gentlemen who have risked their money in this arduous and laudable undertaking”.

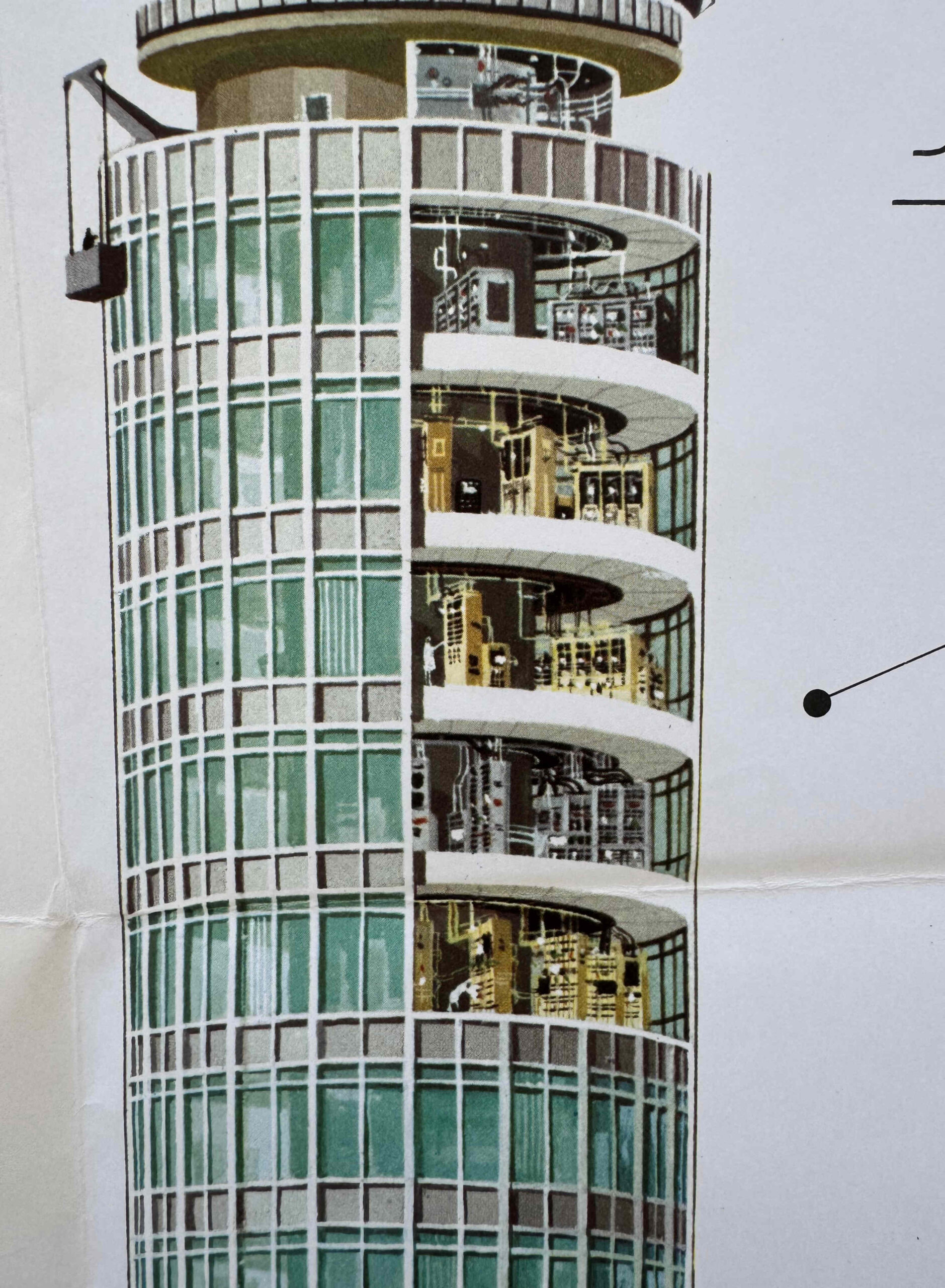

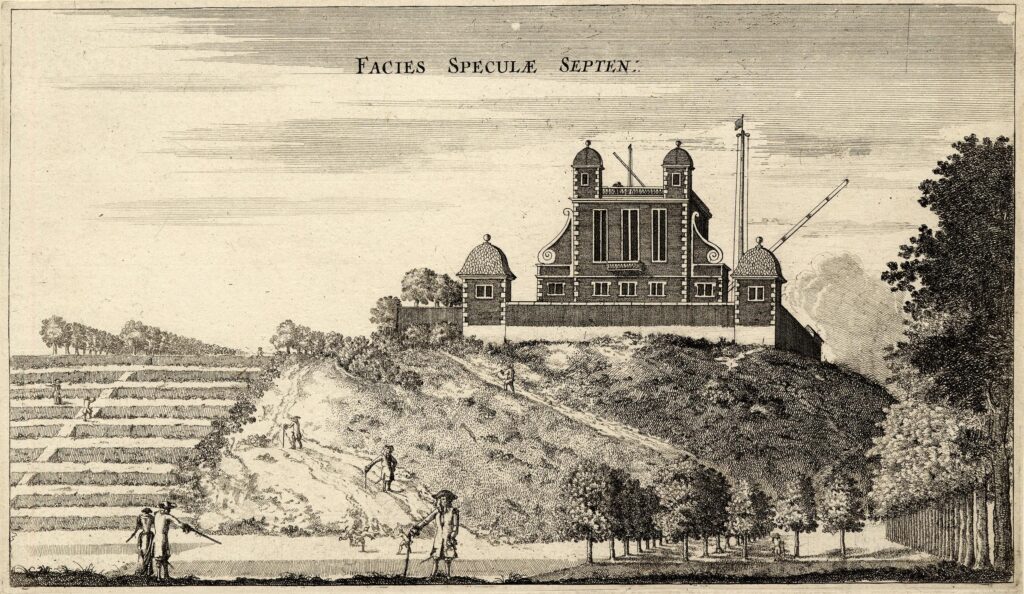

As well as being the first use of steam power in London to produce flour, the Albion Mill’s name was associated with a panoramic drawing made from the roof of the building “London from the roof of Albion Mills”.

The panorama as a form of painting and exhibition was invented by a Scottish painter, Robert Barker. One of the 19th century accounts of the history of the panorama claims that Barker had been imprisoned for debt in Edinburgh in 1785. “His cell was lighted by an air-hole in one of the corners, which left the lower part of the room in such darkness that he could not read the letters sent to him. He found, however, that when he placed them against the part of the wall lighted by the air hole the words became very distinct. the effect was most striking. It occurred to him that if a picture were placed in a similar position it would have a wonderful effect. Accordingly on his liberation he made a series of experiments which enabled him to improve his invention, and on June 19, 1787, he obtained a patent in London, which established his claim to be the inventor of the panorama”.

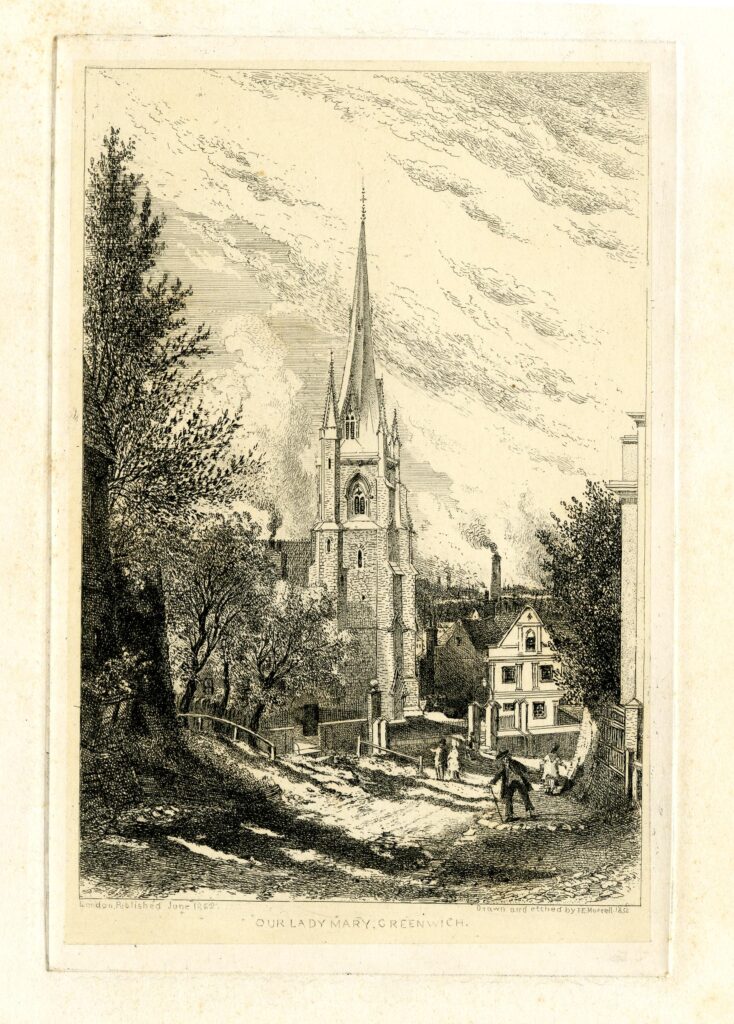

To display his new invention, Barker raised enough money to build “an entire new Contrivance or Apparatus for the Purpose of displaying Views of Nature at large by Oil-painting, Fresco or any other mode of painting and drawing”. This was to be found next to Leicester Square, with a small entrance from Cranbourn Street.

Barker gave his display the name “Panorama”, and once inside, spectators would stand on a raised circular platform in the centre of a round building. They were about 30ft away from the circular wall on which was painted the scene to be viewed, stretching for the full 360 degrees around the spectators.

After entering in the dark, light was then let in from the roof, and it was focused on the scene painted on the surrounding wall – the panorama.

The lighting and the quality of the painting on the wall gave the effect of standing in the middle of the real scene that was portrayed around the wall.

To keep paying spectators returning, Barker regularly changed the panoramas on display, and they were not limited to landscapes. One very popular panorama was of the Naval Grand Fleet lying at Spithead, with Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight in the background.

Robert Barker’s panoramas were very successful and always drew a crowd wherever they were on display. He opened panoramas in France, Holland and Germany, and the panoramas on display in Leicester Square would also go on tour around the country, as the following from Aris’s Birmingham Gazette on the 22nd of October, 1798 illustrates:

“By particular Desire of a Number of Families of Distinction in Birmingham and its Environs; the PANORAMA, Union-street, or perspective VIEW of the GRAND FLEET at Spithead, will continue open till Saturday next, the 27th instant, on which day it will positively and finally close, in order to embark for Hull, where it is engaged. That part of the public who have not yet had an opportunity of seeing the Grand Exhibition, will do well to take the present Opportunity of seeing the Wooden Walls of England before their Departure. Admittance One Shilling.”

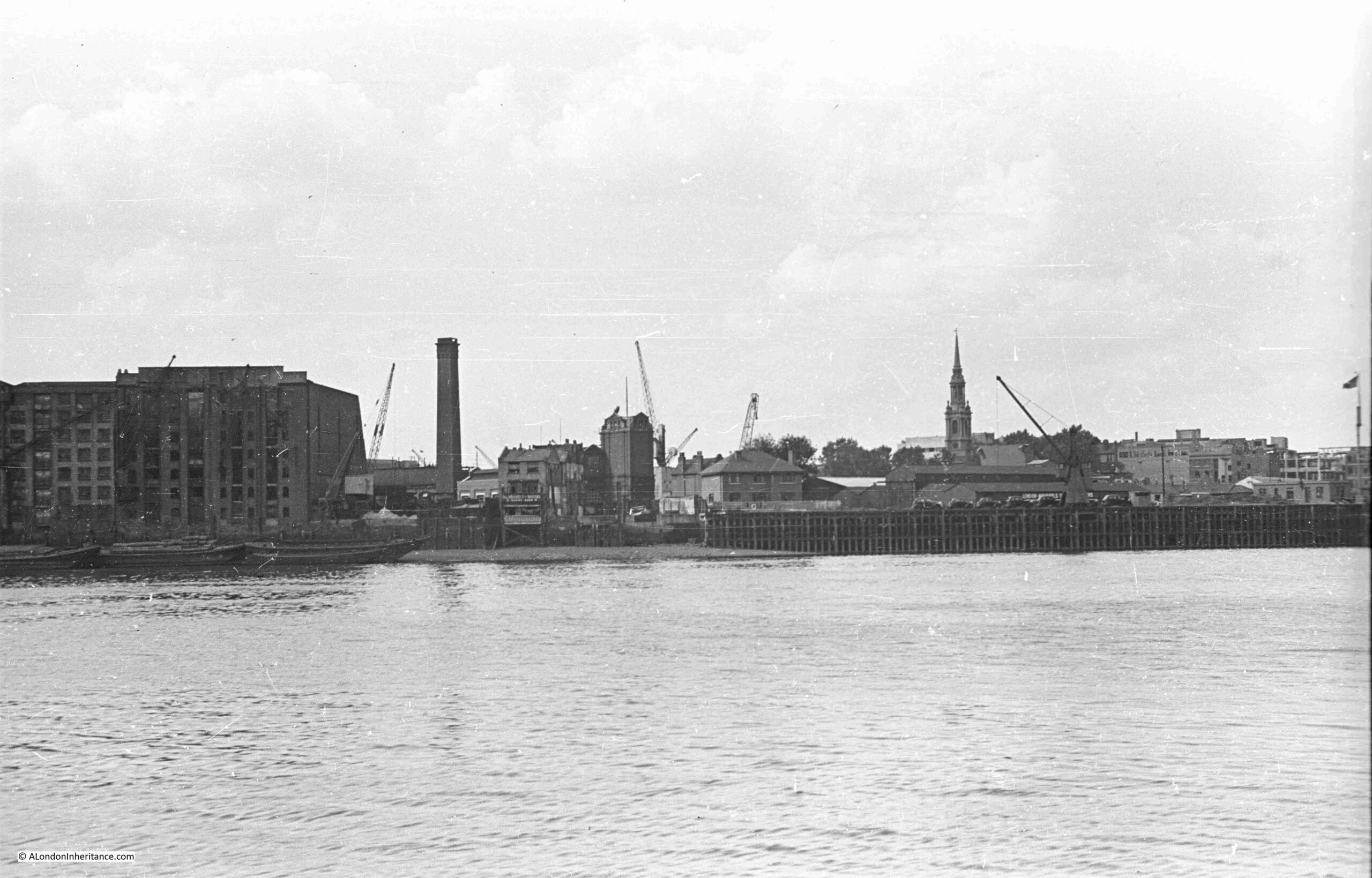

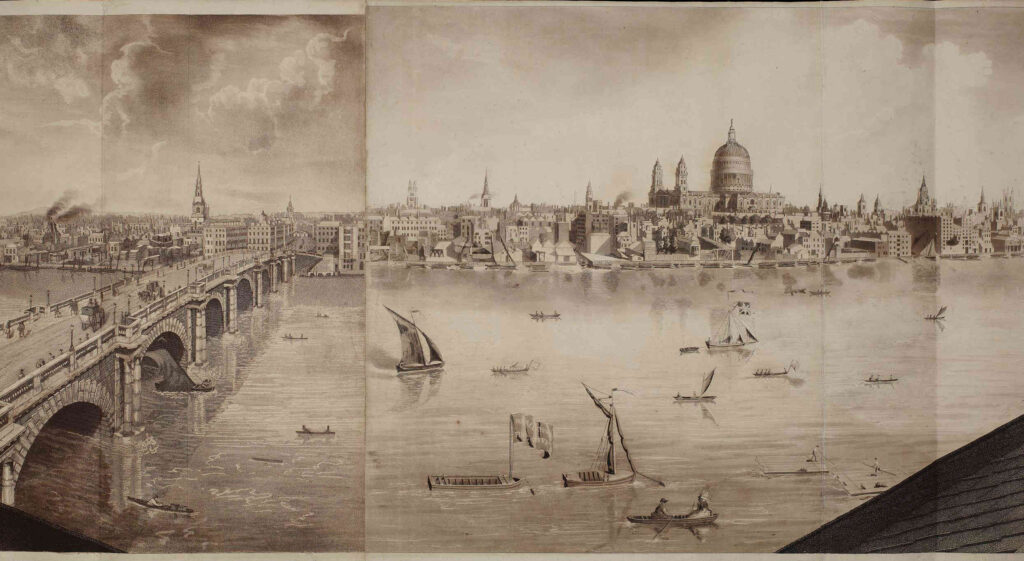

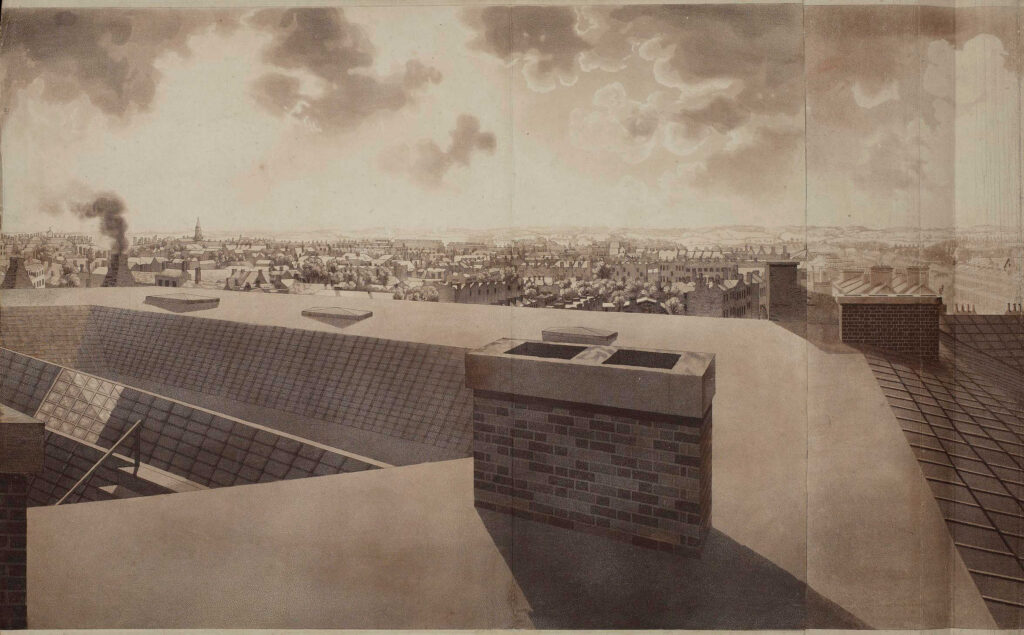

After completion, the Albion Mill was the highest building between St. Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, so it was the ideal location from where to make another panorama, and to do this Barker sent his 16 year old son up to the roof of the mill in the winter of 1790 to 1791 to paint the view for the full 360 degrees – a vast panorama of London at the end of the 18th century.

The British Museum have a copy of the panorama from the roof of Abbey Mill in their collection, and it is available for use under a Creative Commons license, so although today I cannot get to the same height and specific location from where the panorama was made, below is a very rough comparison of the early 1790s with the view of London today.

All the prints in this post are © The Trustees of the British Museum Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Looking to the east:

Looking to the north and we can see St. Paul’s Cathedral, spires of the City churches, and the Blackfriars Bridge on the left:

To the west:

To the south-west:

A very different view today:

To the south:

To mirror the above view, I would be looking straight at the Rennie Garden as in the photos earlier in the post.

As with Robert Barker’s other panoramas, the View from the Roof of Albion Mill also travelled across the country, and internationally, so for example, in 1796 it was on display in Philadelphia in the US, where you could walk in to see the view of London for half a dollar.

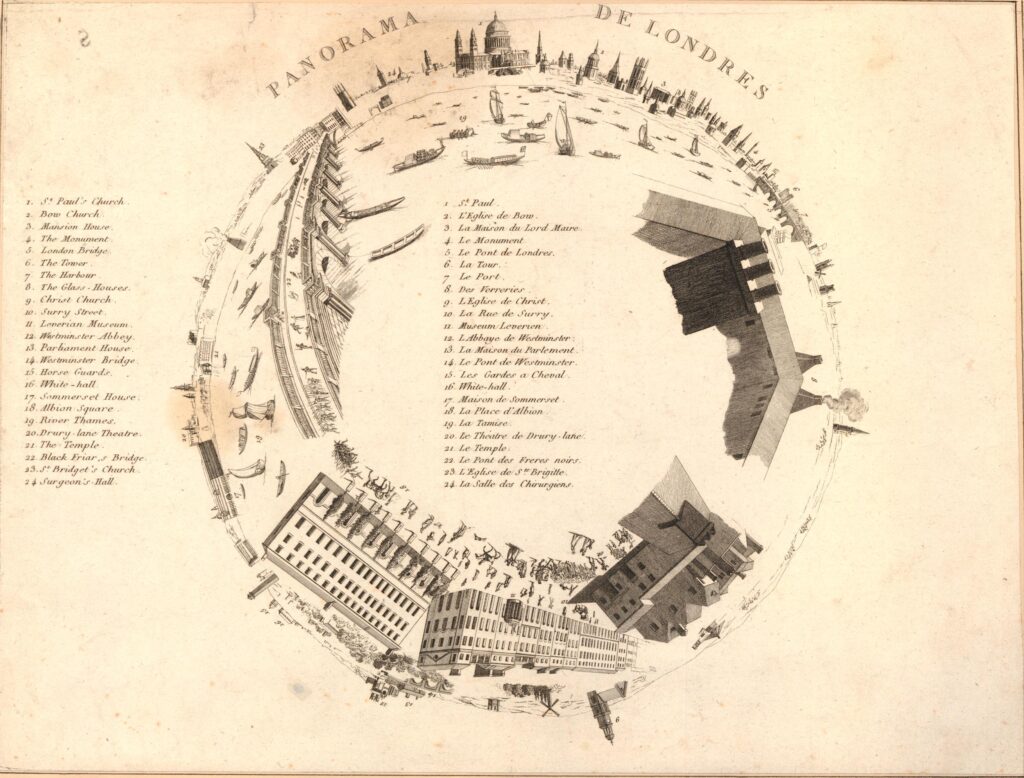

The panorama was also printed onto single sheets to give an idea of the view of London:

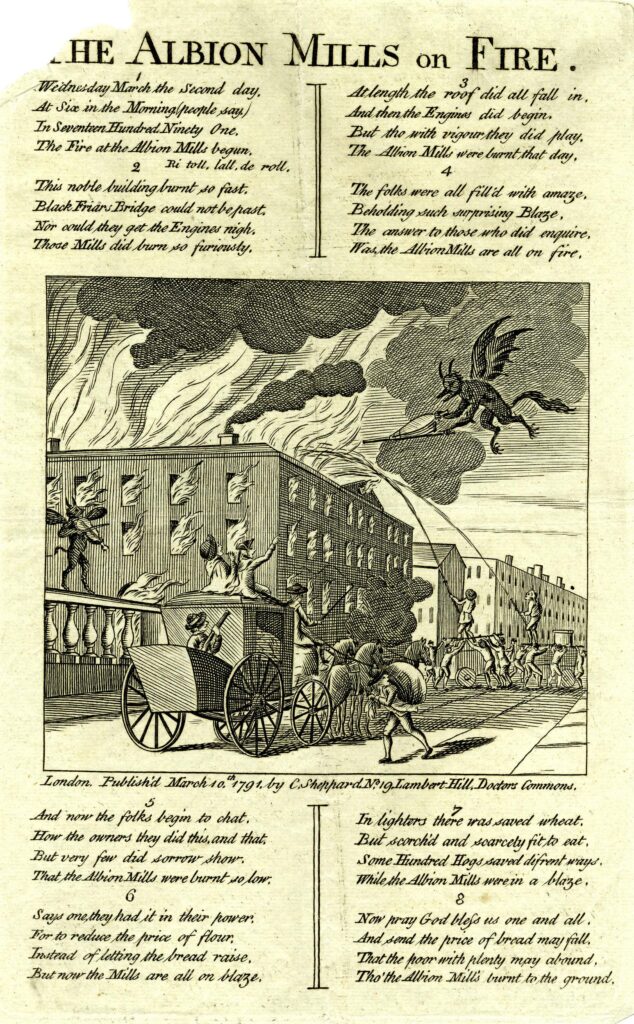

The Albion Mill did not last for long as in March 1791, a couple of months after the panorama was completed, the entire building burnt down.

The following report from newspapers of the time covers the fire, and also provides a possible cause:

“Yesterday morning, soon after six o’clock, a most dreadful fire broke out in the Albion Mills, on the Surrey Side of Blackfriars Bridge, which raged with such unbaiting fury, that in about half an hour the whole of that extensive edifice, together with an immense quantity of Flour and Grain, was reduced to ashes; the corner wing, occupied as the house and offices of the Superintendent, only escaping the sad calamity from the thickness of the party wall.

It was low water at the time the fire was discovered, and before the engines were collected, their assistance was ineffectual; for the flames burnt out in so many directions, with such incredible fury, and intolerable heat, that it was impossible to approach on any side till the roof and interior part of the building tumbling in completed the general conflagration in a column of fire, so awfully grand as to illuminate for a while the whole horizon.

The wind being easterly, the flames were blown across Albion place, the houses on the west side of which were considerably scorched, and the inhabitants greatly alarmed.

In the lane adjoining the Mills one house was burnt to the ground, and others considerably damaged. The Accident is supposed to have been occasioned by the Machinery having been overheated by Friction.

Another circumstance has been mentioned, that might operate either as an original or secondary cause in producing the above catastrophe:- A quantity of Grain that lay contiguous to the Machinery had been damaged by the late Floods, and was Yesterday Morning observed to have acquired such a degree of Heat, as made some of the Workmen conceive that it might be dangerous to put the Mills in motion. The Remark was not attended to, and the Consequence has been what we have related.”

So after 5 short years the Albion Mills had completely burnt down.

The following print shows the mill on fire, attempts to pump water from the river at low tide, into the fire, and watching crowds lining the side of Blackfriars Bridge:

The total loss of the Albion Mill was estimated by the companies that had insured the mill at around £90,000. There were also concerns about the loss of a large quantity of grain, and what this would do to the price and availability of flour. The proprietors of the mill were able to assure concerned Londoners that whilst a large quantity had been lost at the Albion Mill, they still had large quantities at other grain stores.

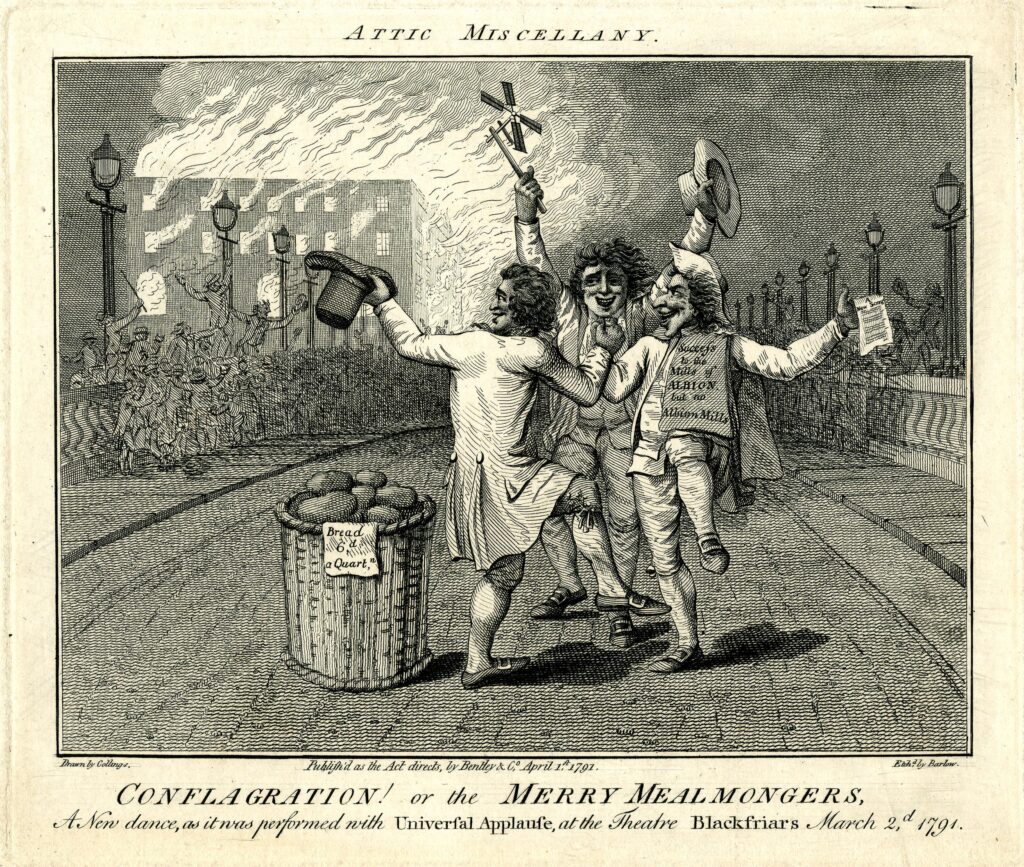

There were many though, who celebrated the loss of the Albion Mill, and a number of satirical prints were published about the fire:

In the above print, the dejected owners can be seen in the boat at lower left. In front of the building there are two barges on the river. The left barge is filled with sacks labelled Pot80 (potato), and the barge on the right with sacks of Indian Wheat. These sacks were implying that the flour produced at the mill had been adulterated. A number of demons can be seen rejoicing at the fire.

The opening of the Albion Mill had a very serious impact on all the millers in London and the counties surrounding the capital. The use of steam power had allowed the mill to produce flour quickly and efficiently, and the impact of this resulted in the closure of many other mills.

As an example of both the impact of the working Albion Mill, and the after effects of the fire, the following is from the Hampshire Chronicle on the 14th of March 1791:

“The Berkshire millers are sensibly affected by the late fire at the Albion mills, but not with grief. Many of them, who gave over working two years since, have again set their wheels in motion.

The flour-mills at Blackwall, Poplar, Limehouse, Rotherhithe, and many other places, which have stood still upwards of these three years, have also begun working again, owing to the Albion mills being burnt down.”

The price of flour had increased during the time of the mill’s operation. In the five years prior to opening, the average price of flour had been 44 shilling, 6 and a quarter pence. During the years the mill was in operation, the average price had increased to 45 shillings and 2 pence. A small increase, but still an increase.

It was argued that the increase in price was down to two bad harvests and that there had been a scarcity of wheat throughout all of Europe.

The following print also had a celebratory theme to the fire at Albion Mills, with a demon playing a fiddle on Blackfriars Bridge as the mill burns, whilst another demon fans the flames:

The following print is titled “A New Dance, as it was performed with Universal Applause, at the Theatre Blackfriars March 2nd 1791” and shows a celebrating crowd on the bridge, and three men dancing in the foreground. The man on the right has a sheaf of papers over his shoulder on which is written “Success to the Mills of Albion but no Albion Mills”:

One of the main complaints against the Albion Mill was that by being able to process so much grain and flour, and by forcing so many other mills to close, it was becoming a monopoly. These allegations may have had some truth, as soon after the fire, it was reported that:

“However well or ill informed the charge of monopoly against the Albion Mill Company may have been, the destruction of their mill has been followed by an almost immediate fall of three shillings per quarter in the price of wheat. This is proof that they were generally considered as having it in their power to keep up the price artificially.”

There were proposals to rebuild the mill in the years following the fire, however permission was not granted for the project, and houses were later built on the site of the Albion Mill.

I always find it surprising how you can take one very small spot in London, in this post, Rennie Garden at the southern end of Blackfriars Bridge, and find layers of history, and so many other connections. The story of John Rennie, a leading mechanical engineer in the later decades of the 18th century, the first steam driven mill in London, the story of the panorama and a unique and innovative view of London in the late 18th century, and the price of grain and flour.