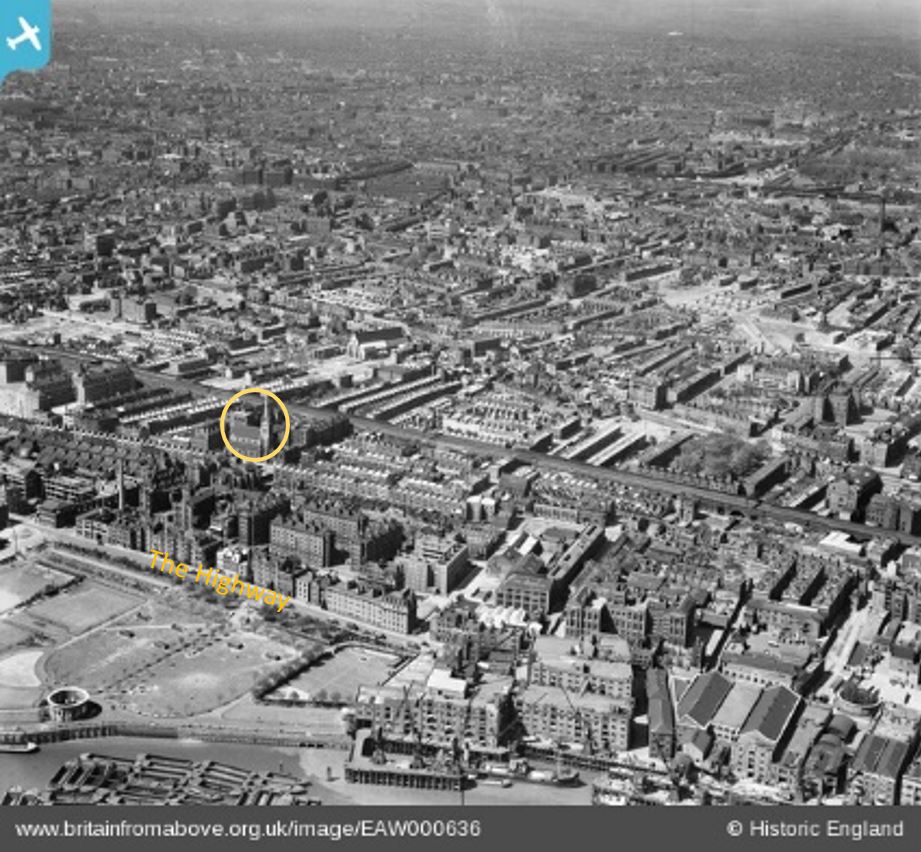

The following photo was taken by my father in 1947, from the south bank of the River Thames, looking over to the north bank, just to the west of the Tower of London (part of which can be seen on the right hand edge of the photo).

The tall building in the centre of the photo is the former headquarters of the Port of London Authority on Trinity Square. Lower, and to the left can be seen a blackened tower. This is the remains of the church of All Hallows by the Tower after the area was very badly damaged by wartime bombing.

Hard to see, but in the very centre of the photo, along the river edge is a set of stairs. I have enlarged the section of the above photo to shows the stairs below:

This was Tower Stairs – one of the many old stairs leading from the land down to the river, described in an 18th century newspaper as “the greatest plying place in all London”.

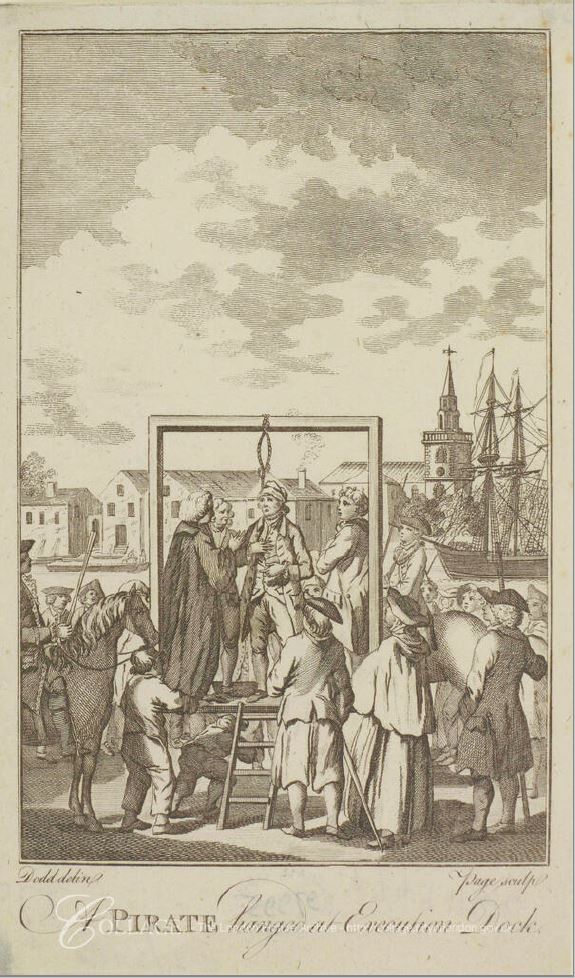

I have written about a number of these stairs in previous posts, and I must admit to be fascinated by them. They connect two very different worlds, the land and the water, although they are an integral part of both, and for so many people they have been a point of arrival or departure.

Along with City churches, they have been in the same location for centuries. They are a fixed point where we can trace events in the history and life of everyday Londoners.

The majority of Thames Stairs are not that obvious, and people probably walk by without noticing them.

A wonderful project would be plaques alongside to restore the original name of each of these stairs, and perhaps some of the key events that happened at each stair. An initiative to try and reconnect people with the river.

Tower Stairs were an important set of stairs to the river. They were adjacent to the Tower of London and they were to the east of London Bridge, therefore if you were travelling to places along the east of the river, such as Greenwich, by using Tower Stairs you would avoid having to pass through the narrow arches of London Bridge, where the fast flow of water through a narrow gap was always a risk.

The following photo is my 2021 view of the same photo taken by my father in 1947:

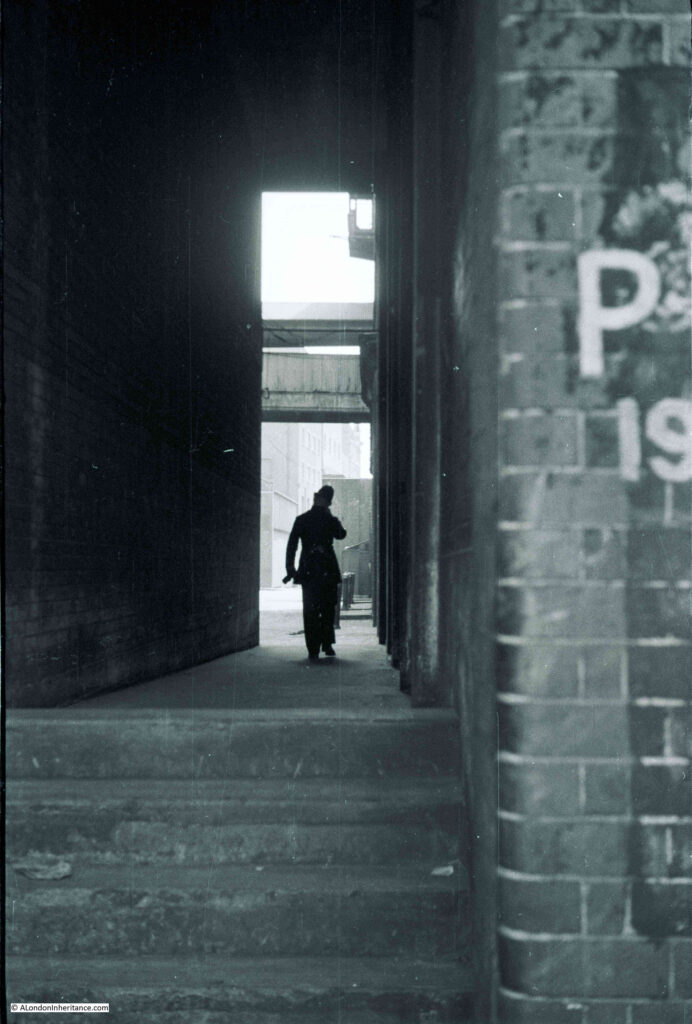

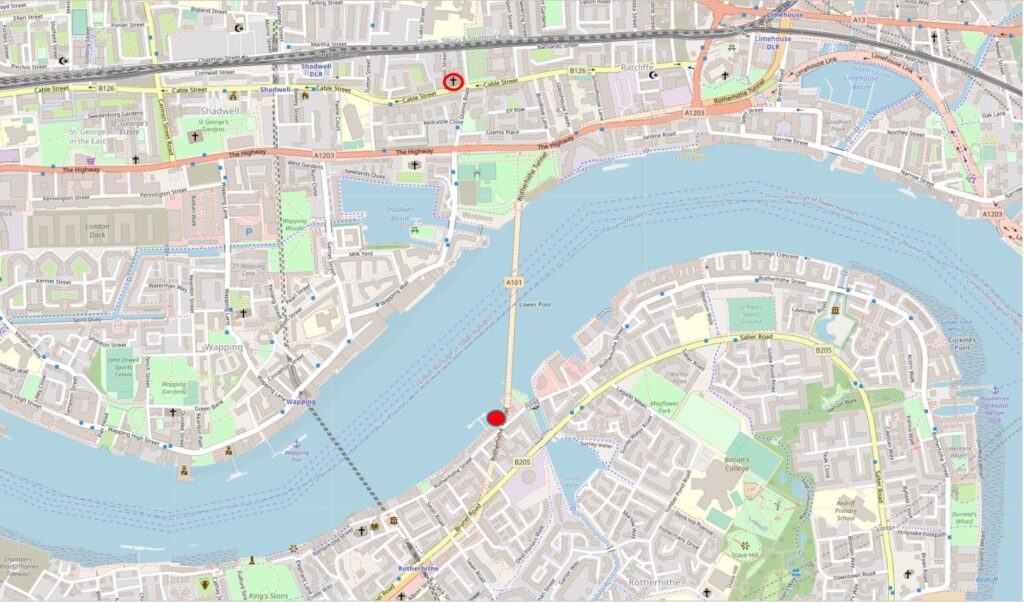

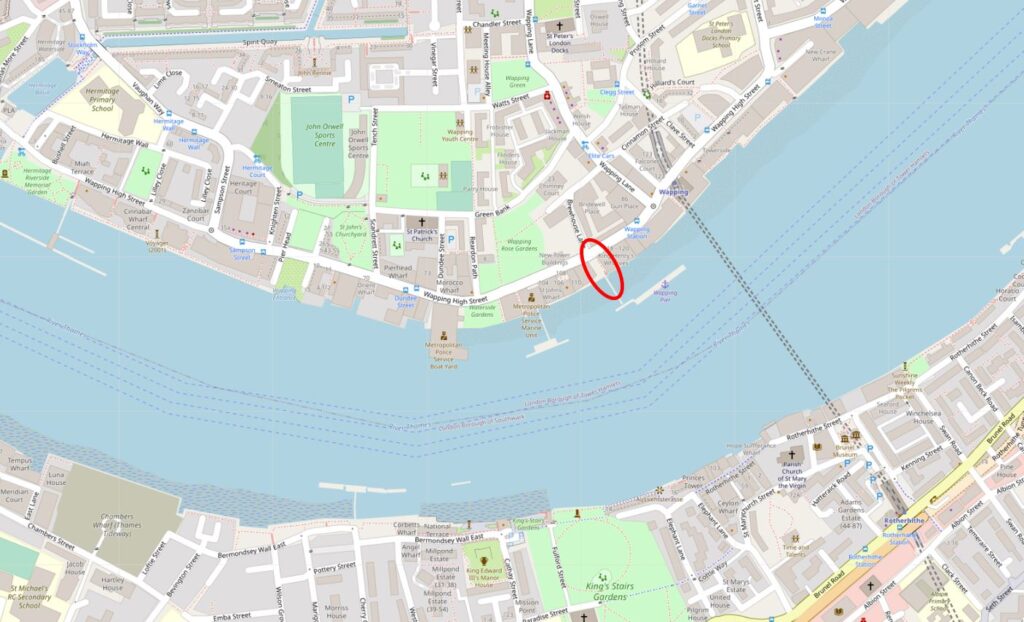

Tower Pier now hides the location of the stairs in the above photo, so to find them, we need to cross the river and look for them under the entrance walkway to Tower Pier:

A wide set of stairs remain, although a considerable width of the stairs has been built on to provide support for the entrance to Tower Pier. Only a narrow section on the left of the stairs runs up to street level.

The following photo is looking at the entrance to Tower Pier. The entrance to the stairs is to the lower right of the pier entrance, at the end of the central light section of paving which runs between the two dark sections.

The entrance to Tower Stairs (unfortunately locked), showing the narrow section which leads down to the wider stairs and to the river.

There are numerous newspaper reports about events happening at these stairs.

In March 1793, it was reported that “one hundred and fifty Frenchmen, chiefly officers, who had fled from Dumourier’s army, landed at Tower Stairs from Holland. They gave the most deplorable accounts of the wants and distresses of Dumourier’s soldiery”.

In May 1750, after reviewing the First Regiment of Foot Guards in Hyde Park, the Duke of Cumberland arrived at Tower Stairs , where he took to the water “to go Pleasuring for a few days in the Caroline Yacht”.

In January 1768, the stairs were described in the words I used in the title to this post as “the greatest plying place in all London” which gives some indication of their importance. The same report stated that old houses adjoining Tower Stairs would be pulled down in the spring to make the “landing more commodious”.

Tower Stairs was also the site of the numerous small tragedies that were almost a daily occurrence on the river. In May 1739 “a young lad, about 18 years of age, servant to a Druggist in Wood Street, washing himself in the river off Tower-stairs, was taken suddenly with the Cramp, and drowned, in sight of numbers of spectators, none of whom could be quick enough to save him”.

And in October 1738, “Captain Collier, Commander of a Norwayman, landing at Tower Stairs, upon stepping on shore, his foot slipped, and he fell into the river and drowned”.

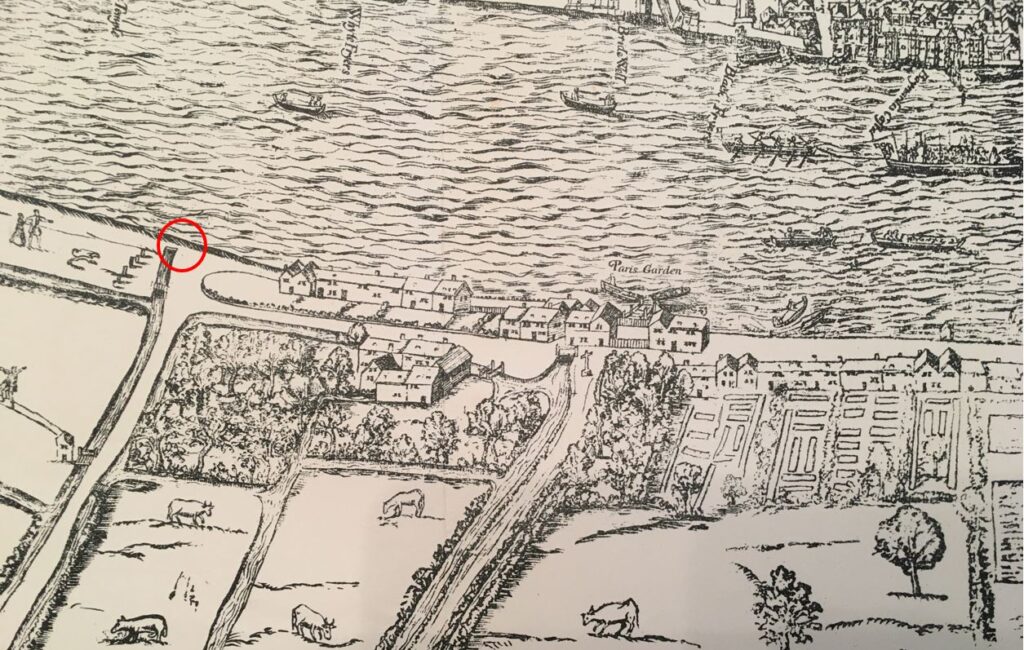

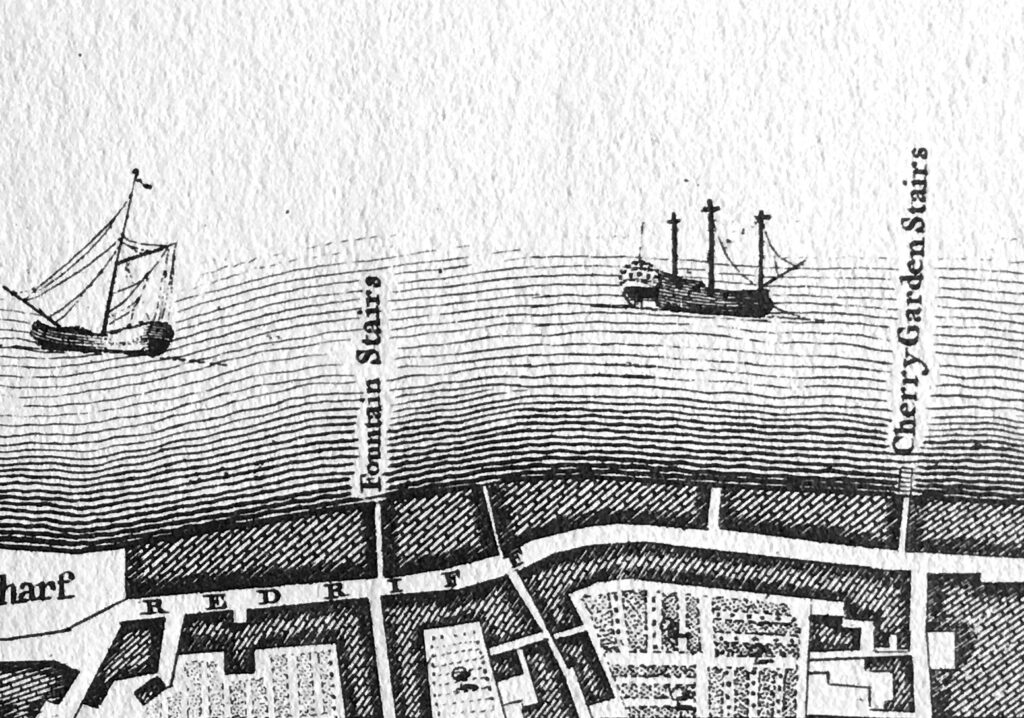

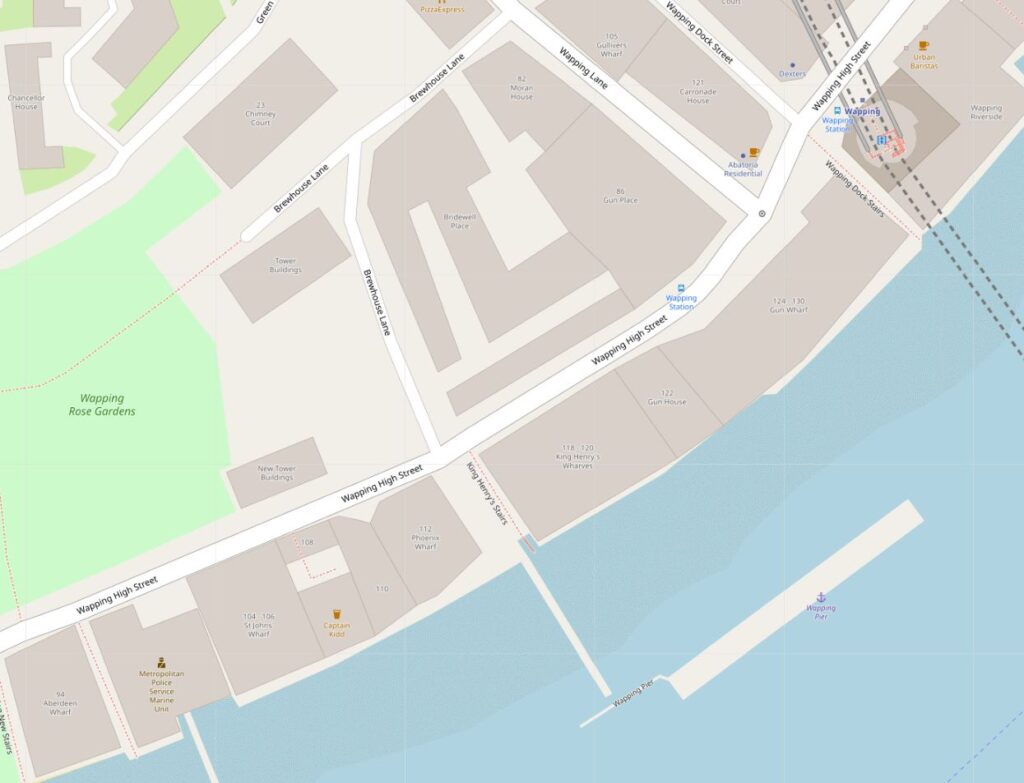

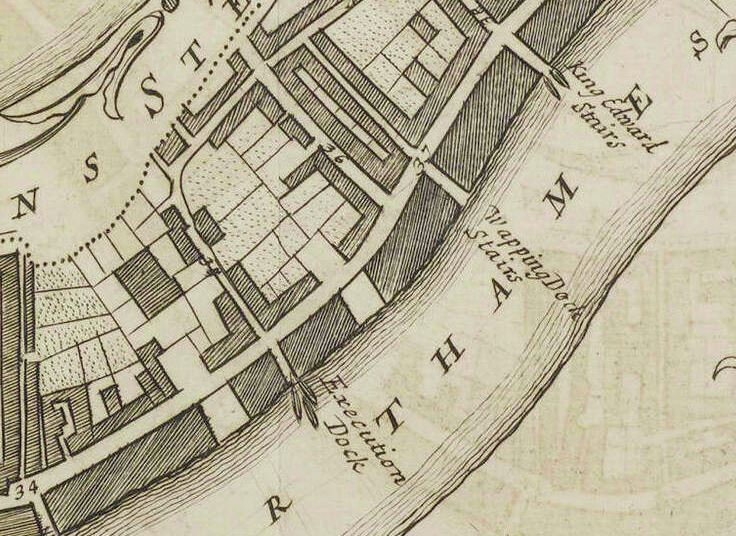

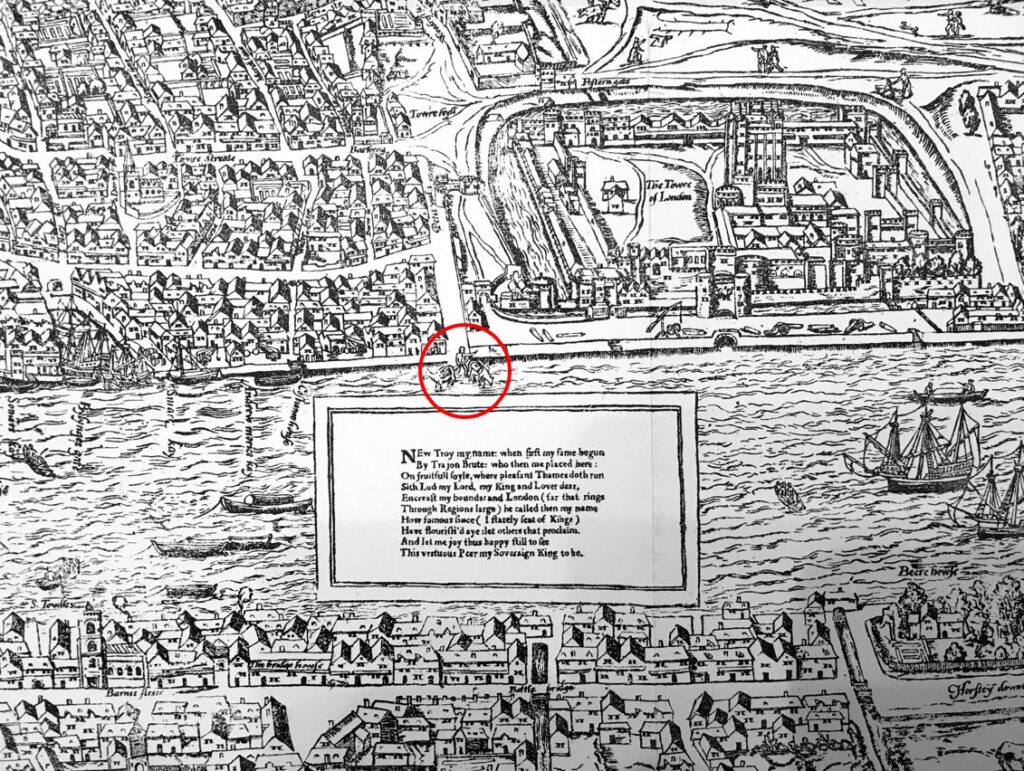

Tower Stairs are very old. Although not named, they are shown on the 19th century reprint of the mid 16th century map known as the Agas map (although the original has not survived, only later, modified copies).

The stairs are not named, but in the following extract, look to the left of the Tower of London, and a wide street runs down to the river, where there is a break in the river wall. A man appears to be driving a couple of animals into the river at the point where the stairs are located.

The stairs are shown and named Tower Stairs on Rocque’s 1746 map of London. They appear right on the edge of the page on my reprint of the map so I have not included an extract.

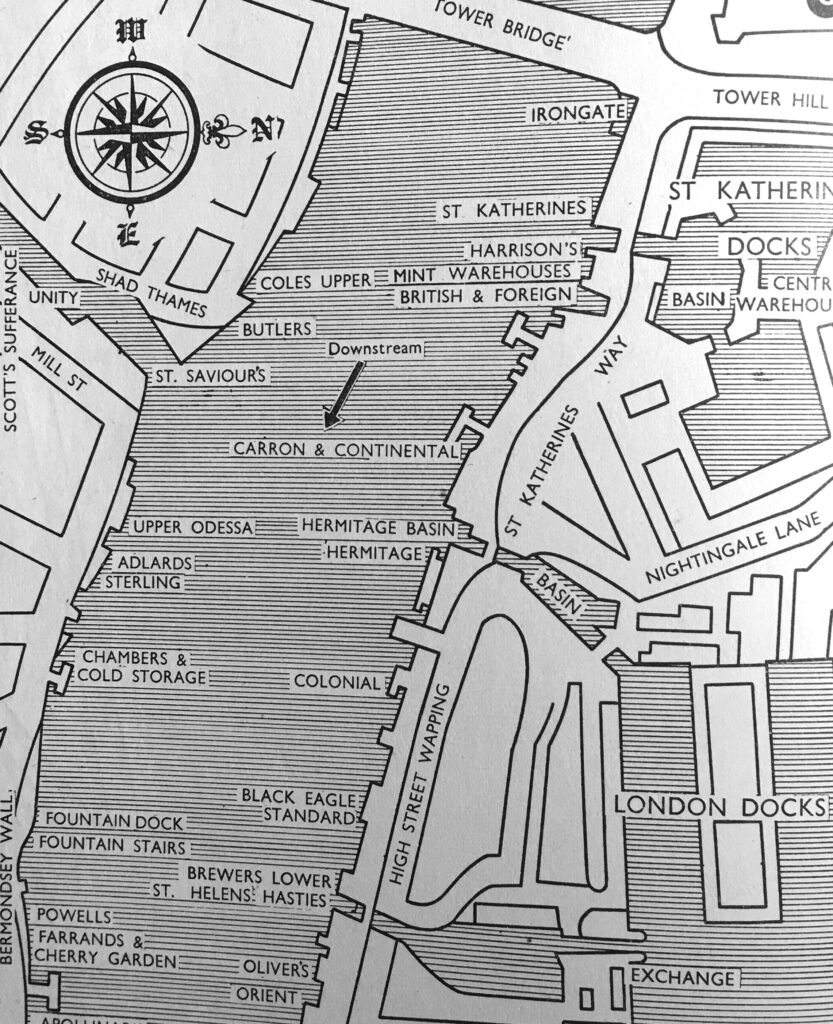

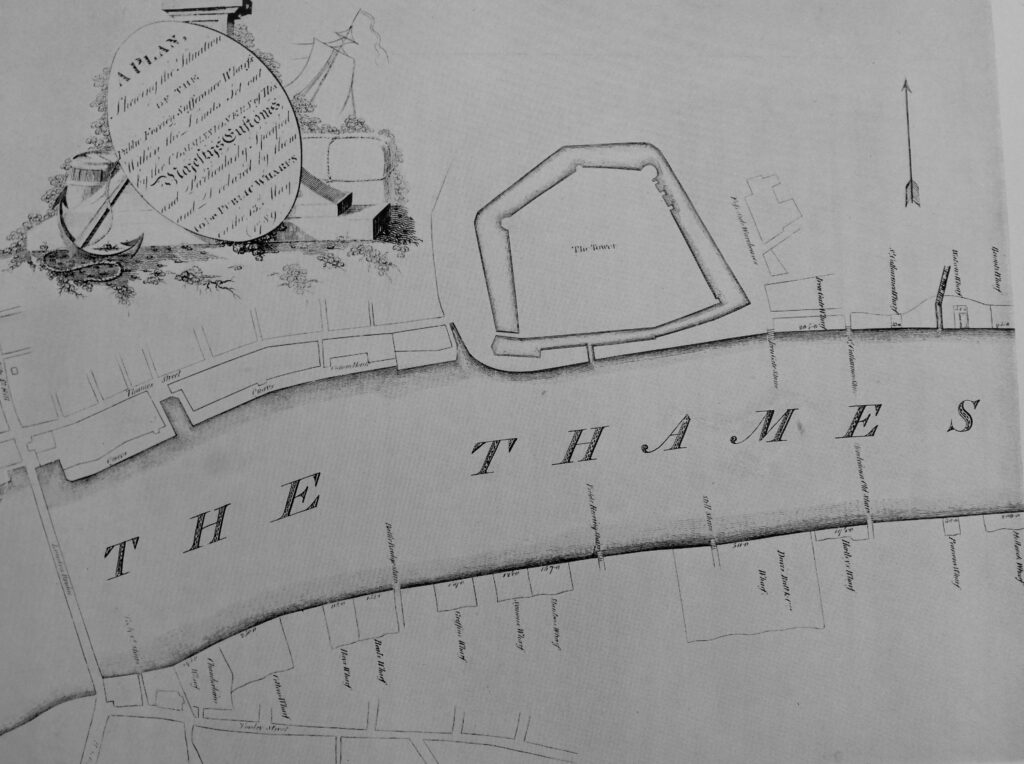

They are also shown on Smith’s New Plan of London, dating from 1816. I have arrowed the stairs in the following extract:

The importance of the stairs can be judged by their location, adjacent to the Tower of London, and where Great Tower Hill meets the Thames. As can be seen in the above map, there was also a small inlet to the left of the stairs, which probably provided additional mooring space for Watermen, and boats loading and unloading at the stairs.

As you have probably seen from previous posts, I use newspaper archives as one of the historical sources when researching posts.

Being newspapers, they have to be read with some care, to try and see through the way the story has been edited and added to by the journalist, however they do provide an account that was written at the time.

There are numerous references to Tower Stairs, so I decided to take a few from the 18th century to see what was happening at the stairs. I have already recorded some local events, but there were four accounts mentioning Tower Stairs that tell of a wider story of life in London in the eighteenth century, based on people who walked along Tower Stairs, so for the rest of the post, four stories about Press Gangs, the Frozen Thames, the Blackheath Chocolate House and when Cherokee Indians visited London.

The Press Gangs

The danger of being taken by a Press Gang and tricked into service in the Navy was more often a risk for those living and working in the streets to the east of the City, however those sleeping in their beds in the City were at risk, but the City of London would always protect their citizens, as this report from the12th of September 1755 records:

“Monday at the Sessions at Guildhall, Robert Alsop, a Midshipman of one of her Majesty’s men of War, was convicted, upon his own confession, of riotously entering the Dwelling-House of Mr. William Godfrey at Billingsgate, a reputable Citizen, and Livery Man of London, at the Head of a Press-Gang, on the 25th of June last, in the Night-time; and for seizing him by the collar, knocking him down, forcibly dragging him through the Streets of London to the Tower-Stairs (with only one Slipper on), carrying him on board a Tender on the River Thames, and confining him in the Hold for twelve hours, without any Warrant of lawful Authority, to the great peril of his Life; when the Court were pleased to fine him £5, and to order him to be imprisoned one Year in Newgate. This Prosecution was carried on by the Directions of the Court of Alderman, at the Expense of the City, in order to vindicate the Rights and privileges of its Citizens, and to prevent such Insolences for the future.”

The City of London was always ready to defend the “Rights and Privileges” of their citizens. I suspect a fine of £5 and one year of imprisonment was a reasonably hard sentence, which also acted as a deterrent to others.

During the 18th century, the Navy was in almost constant need of men to man the ships. The Derby Mercury on the 17th March 1743 described another event at Tower Stairs, when “They press so strong upon the River Thames for Seamen, that not a Day passes but they get a great many Hands, and last Saturday, a Waterman, belonging to Tower Stairs, who had a Protection, was pressed five different times”.

Protection was mainly issued by the Admiralty or Trinity House for specific types of employment, and the bearer had to prove their protection if they were caught by a press gang. This would normally stop a person being taken, however in times of war, even protections were abandoned and almost anyone could be taken.

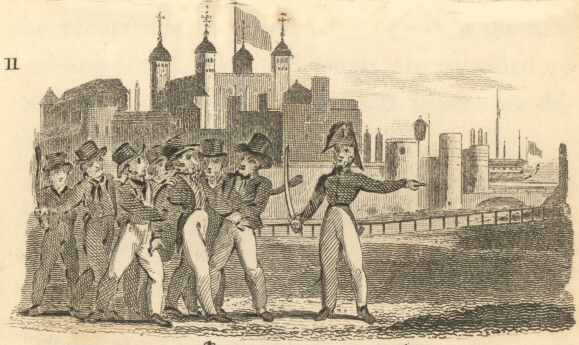

The 1828 edition of City Scenes by William Darton shows a press gang in operation at Tower Hill. I assume the man at the front is pointing towards Tower Stairs where the unfortunate man is being dragged. A Royal Nay ship can be seen in the background.

Source: The Project Gutenberg eBook City Scenes by William Darton

Having avoided the Press Gangs, there is another danger in the Thames off Tower Stairs:

The Frozen Thames

Up until the mid 19th century, a period known as the Little Ice Age had been causing very cold winters and periods when warm summers were not always dependable. This period of colder weather began around the 14th century, but the impact on London is well documented in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

Whilst the popular image is of ice fairs held on the Thames, for those who had to work or travel on the river, ice would also present a danger. For those without the sanctuary of shelter and warmth, very low temperatures would also be a risk to life.

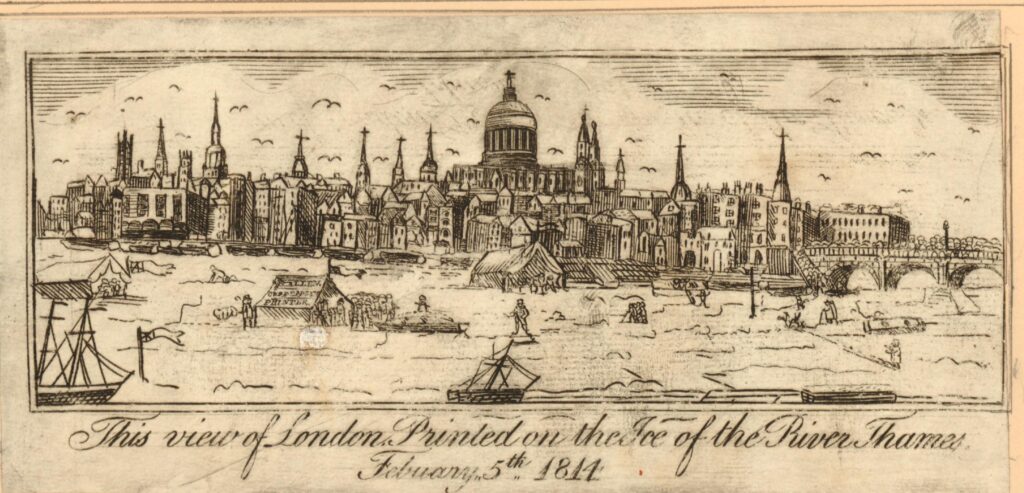

Following image shows “This view of London, printed on the Ice of the River Thames, February 5th, 1814”: (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

News reports referencing Tower Stairs show the dangers of the frozen River Thames. On the 12th January 1740, the Ipswich Journal reported: “On Tuesday Night an adventurous Waterman undertook to carry his Fare, a Woman and a Child, from Tower-stairs to Battle-Bridge, as the tide was coming in; but the Islands of Ice floating down upon them they were drove to the Bridge, where they lay in sight, perishing with the Cold, but out of reach of Relief from any of the Inhabitants of the Bridge, but at last were fortunately carried through to St Mary Overy’s Stairs, and taken up almost to Death. Tis thought neither the Woman nor Child can recover.”

The Bridge was London Bridge when it still had houses and businesses running along the bridge over the river. The relatively narrow arches for water to flow under the bridge caused a fast flow and it was a very dangerous place to get trapped.

In the same report was an indication of the amount of ice on the river “Yesterday morning at Low Water, the Thames was so covered with Ice above Bridge, that several Men walked over from Old Swan to Pepper-Alley Stairs”.

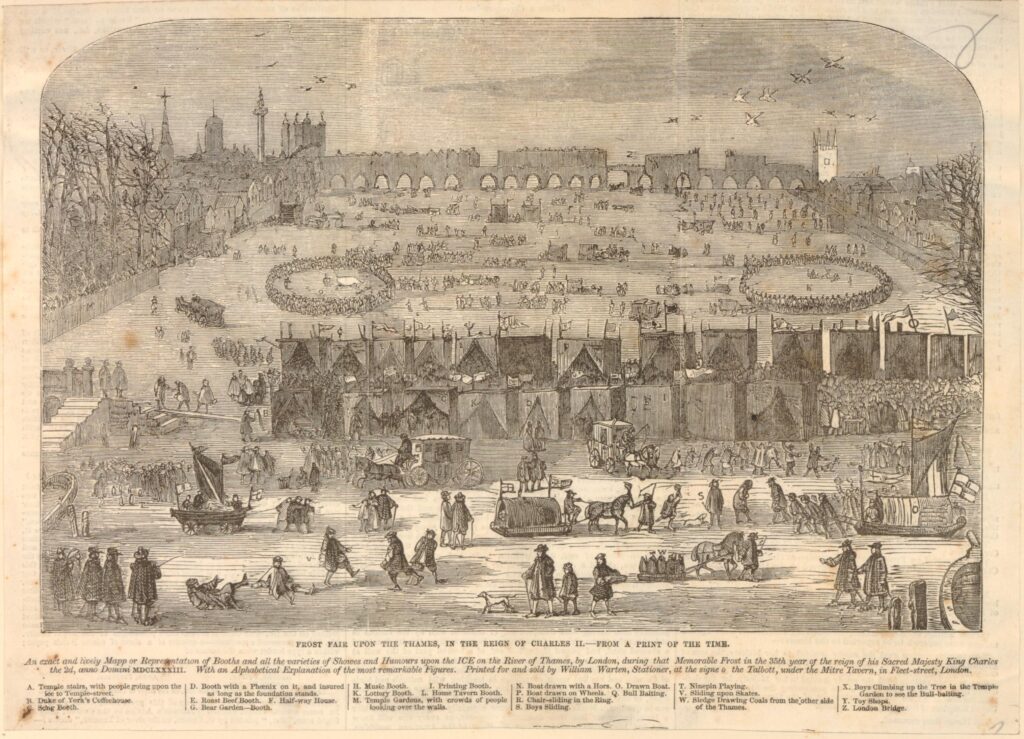

The term “Above Bridge” was used to refer to the stretch of the Thames to the west of London Bridge, in the direction of Westminster. The following print shows a Frost Fair on this area of the Thames during the 17th century. London Bridge is in the background (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

Although prints such as the one above show a scene of celebration on the frozen river, there was a very dark side as the Kentish Weekly Post reported on the 9th January 1740 where “Several dead Bodies float up and down with the Tide and Ice, but none of them can be taken up”.

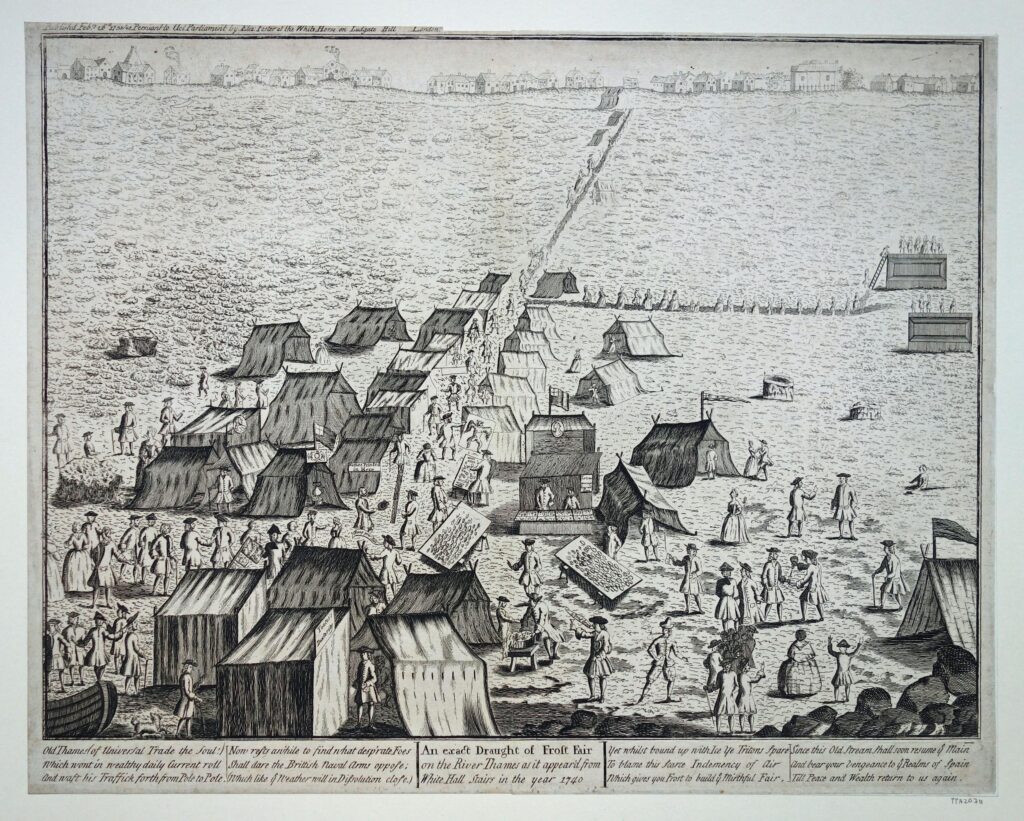

The following print dates from 1740, the year of the above news reports and is titled “An exact draught of Frost Fair on the River Thames as it appeared from White Hall Stairs in the year 1740” (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The winter of early 1740 seems to have been a particularly bad winter for those on and off the river. On the 5th of January “Above 30 boats, twas judged lost between Tower-stairs and Woolwich, most of which were stav’d, but some sunk under the Ice and were not seen afterwards”.

The above paragraph referencing Tower Stairs was at the end of a longer description of the January weather in London: “On Saturday Night, by the Violence of the Wind, several boats were drove from their Fastenings above Bridge near Shore and stav’d to Pieces by the large Flakes of Ice that were brought down by the Tide. The same day in the morning, a Hoy laden with Malt was sunk in Chelsea Reach by the Violence of the Wind.

Two Coasters were drove from their Anchors at Horselydown upon the Sterlings at London bridge, where they lay for some time being beaten against the Houses, to the great Terror of the Inhabitants; but by the turn of the Tide they were luckily carried off, tho’ not without having sustained very great Damage.

Besides the two Vessels above-mentioned, there have been five more since cut from their Anchors by the Ice and drove down against the Bridge, where their Bowsprits have broke into several of the houses of the Eastern side and done great Damages to the Inhabitants.

On Sunday three Boys in a Boat off Rotherhithe were drove away by the great Flakes of Ice and perished thro’ the Severity of the Frost.“

As ever, what is a danger to some is an opportunity for others, although in this instance, without the hoped for outcome:

“Yesterday great Numbers of London Gunners assembled at the several Stairs leading to the Thames, to shoot Ducks, Gulls and Road Geese, which appeared in great Plenty; and many of them were killed, tho’ none could be brought off, the Frost not yet having prevented the Currency of the Tide. Dogs were of no use to bringing them off, the Edges of the Ice on which the birds settled being too weak for the Dogs to get up by.“

As well as freezing much of the Thames, the cold winter of 1740 was a danger to those without the benefit of shelter and warmth:

“A poor man without either Money or Friends, on Friday night last was obliged to take up his Lodging on a Laystall in Tyburn Road, and was on Saturday Morning found dead thereon; although he had covered himself over with Dung and loose Litter.

On Sunday Night last, about nine o’clock, a Man about 60 years was found dead in Pensioners Alley in King-street, Westminster, supposed to have perished for Want; as were also two aged Men by the Waterside at White-friars, and two Women in Old Street, all through excessive Cold and for Want of Nourishment.”

A laystall, referred to in the article was a place where “waste and dung” was deposited.

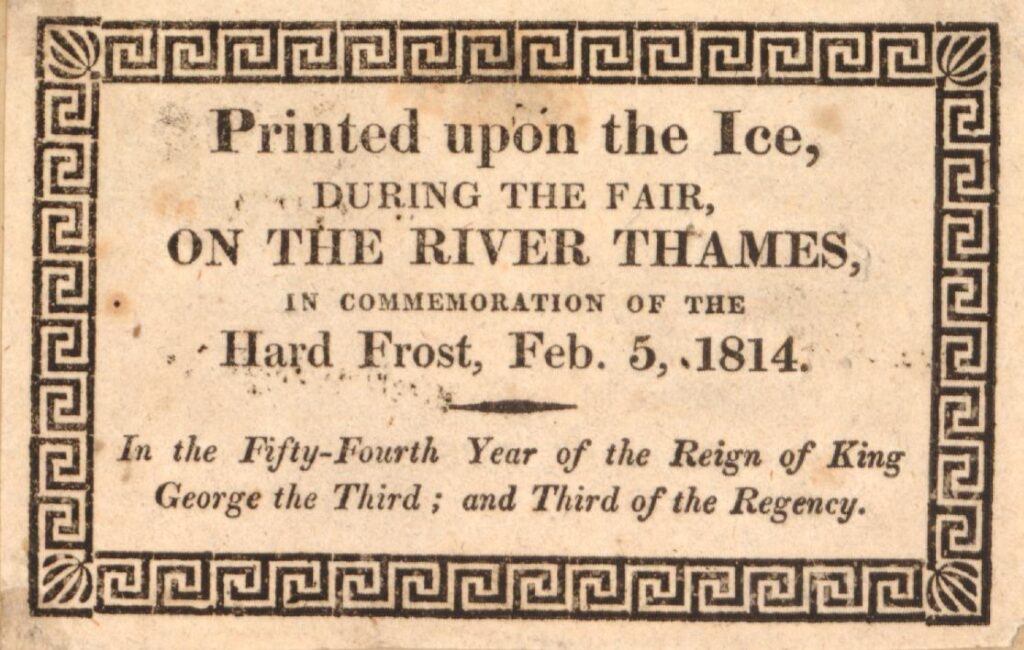

Souvenirs of Frost Fairs and years when the river froze could be purchased from booths on the Thames, including some which were printed on the frozen river (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The above souvenir was printed on the 5th of February 1814, and the following print from Bankside shows the Thames as it appeared on the 3rd, 4th and 5th of February 1814 (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

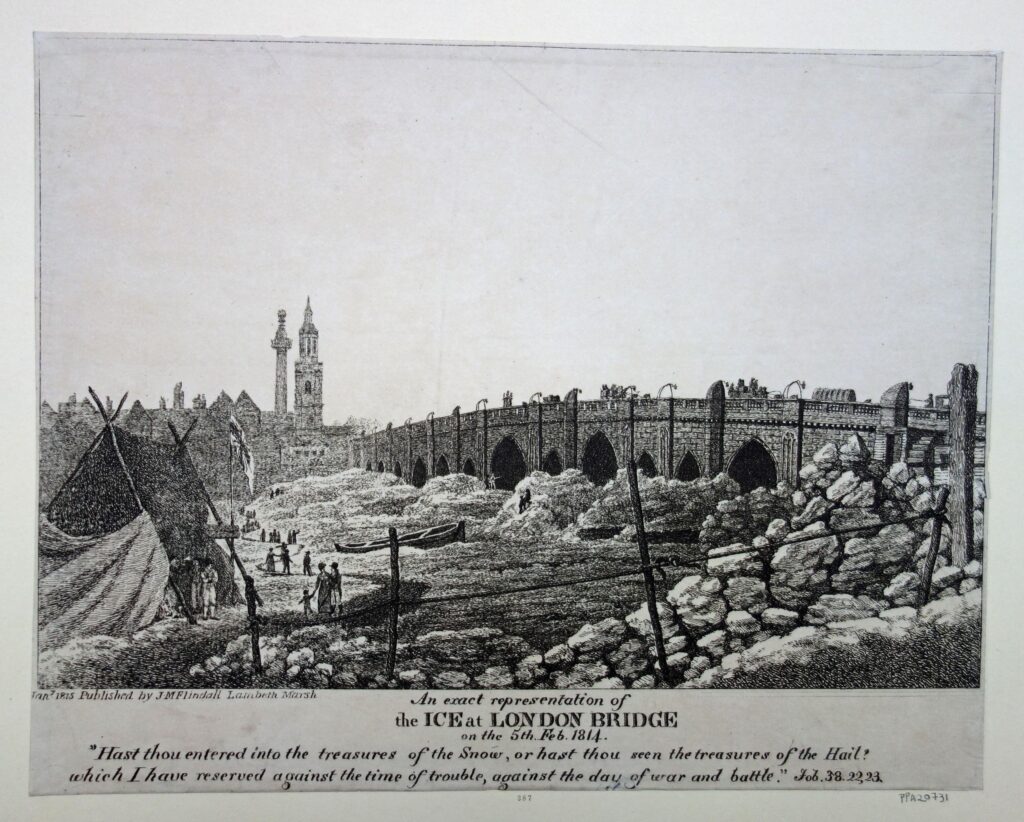

A couple of the articles above refer to the dangers of being swept up against London Bridge, where ice would pile high up against the side of the bridge. The following print from 1814 is titled “Ice at London Bridge” and shows how the narrow channels under the bridge would restrict water flow and allow large amounts of ice to collect against the bridge (© The Trustees of the British Museum).

Now off to a warmer place, as my next stop from Tower Stairs is:

Blackheath Chocolate House

Tower Stairs appear to have been one of the main routes for Royalty when they headed to Greenwich. From the Newcastle Courant on the 8th September 1722:

“This day the young princesses, with a Guard, came through the City, took water at Tower Stairs for Greenwich; dined at Sir John Jennings, and after seeing the Hospital of Greenwich and other Rarities of the place, returned in the evening to Kensington”.

On the 30th June 1736, the Kentish Weekly Post was reporting another Royal visit to Greenwich, which included a visit to a place of entertainment at Blackheath:

“On Saturday evening their Royal Highnesses the Prince and Princess of Wales came through the City from Kensington, and taking Water at the Tower Stairs, went down the River in a Barge, attended by two others, in one of which was a fine Band of Music. Their Royal Highnesses landed at Greenwich, and went to the Chocolate House on Blackheath, where they had an elegant Collation, and about twelve returned back to Kensington.”

The Prince and Princess of Wales were the future King George II and his wife Caroline of Ansbach.

The Chocolate House was a popular place for people to meet, drink chocolate, scheme and plot in the 17th and 18th centuries. The chocolate drink was very different to the type we would drink today. It was heavily sweetened, and would be flavoured with spices and fruits.

There were several Chocolate Houses in London, but I was not aware of one at Blackheath, which if not already a popular place, would be the place to be seen after the Prince and Princess of Wales visit.

The article referenced Blackheath rather than Greenwich, so it was not close to the river or in the park, and luckily a series of articles in the Kentish Mercury in 1902 located the site of the Chocolate House, starting with the following article on the 22nd August 1902:

“THE CHOCOLATE HOUSE ON BLACKHEATH: A glimpse of the ‘manners and customs’ of some 130 years ago is obtained in the following paragraphs taken from the Kentish Express of July 4th, 1774 – ‘Friday, the Kentish Society held their annual feast at the Chocolate House in Blackheath, where there was a most elegant entertainment, and it was unanimously agreed to support the Hon. Mr Marsham and Mr Sawbridge to be the Members of the County of Kent at the General Election, being gentlemen of very considerable property in the said county, and independently to support the interest of the same. Lord North’s name was mentioned, that he is tended to offer, but they all declared to oppose him’.

Perhaps some of our readers can identify the site of the Chocolate house on Blackheath.”

The challenge of finding the location of the Blackheath Chocolate House was one that the readers of the Kentish Mercury rose to, and a series of articles followed based on reader feedback. On the 29th August 1902:

“A correspondent says that while he is unable to identify the site of the Chocolate House on Blackheath, he remembers that twenty years ago there was a pond at the top of Hyde-vale known as Chocolate Pond. He suggests that this may offer some clues.”

On September 5th, 1902: “Mr Alderman Dyer appears to put the matter to rest with the interesting statement that it was in The Grove between Nos. 4 and 5, and was a fashionable resort of the period. The beaux and belles of Blackheath much resorted thereto in the days when George the Third was King, for the purpose of drinking chocolate and discussing the scandal of the neighbourhood. The house was subsequently used as a ladies’ school, but was pulled down some years ago.”

The Kentish Mercury declared success in finding the location of the Chocolate House on the 26th September 1902, when “The question of the site of the Chocolate House on Blackheath, with a view to the definite fixing of which we some time solicited information, can now, we opine, assumed to be settled. documentary evidence in our possession goes to show that the site is now occupied by the houses 4 and 5, The Grove, Blackheath.

By the kindness of a gentleman living on Blackheath-hill we have been afforded the opportunity of inspecting a lease dated from 1776, from Mr. John Wilkinson to Mr. Charles Walker, of the property which stood upon the site in question., described in the document, which is mutilated, as in ‘Chocolate-row’.

Mr Charles Walker, aforementioned, is described as of ‘Chocolate House’. That this Chocolate House was a place of fashionable resort and entertainment we have previously mentioned. Proof is afforded by the fact that on the lease there are clauses relating to the use of the assembly rooms for ‘dancing, music and other diversions’. Our informant himself remembers the premises referred to, before the building was pulled down for the erection of those at present standing.”

The article also mentions an “Olde House” in Hyde Vale where the footmen and attendants would wait whilst their “masters and mistress were disporting themselves in the Chocolate House” – which gives a good impression of the atmosphere in the Chocolate House.

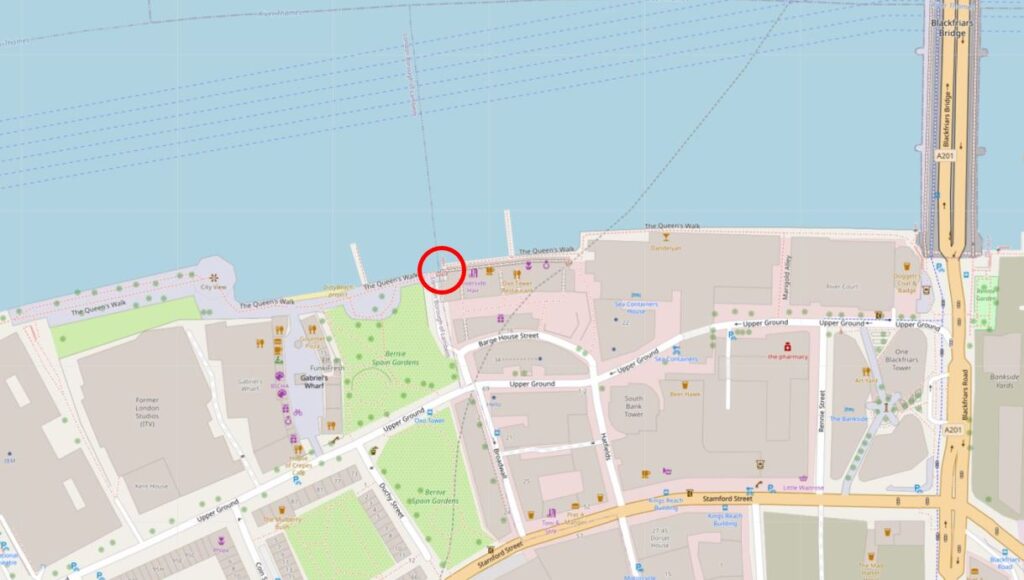

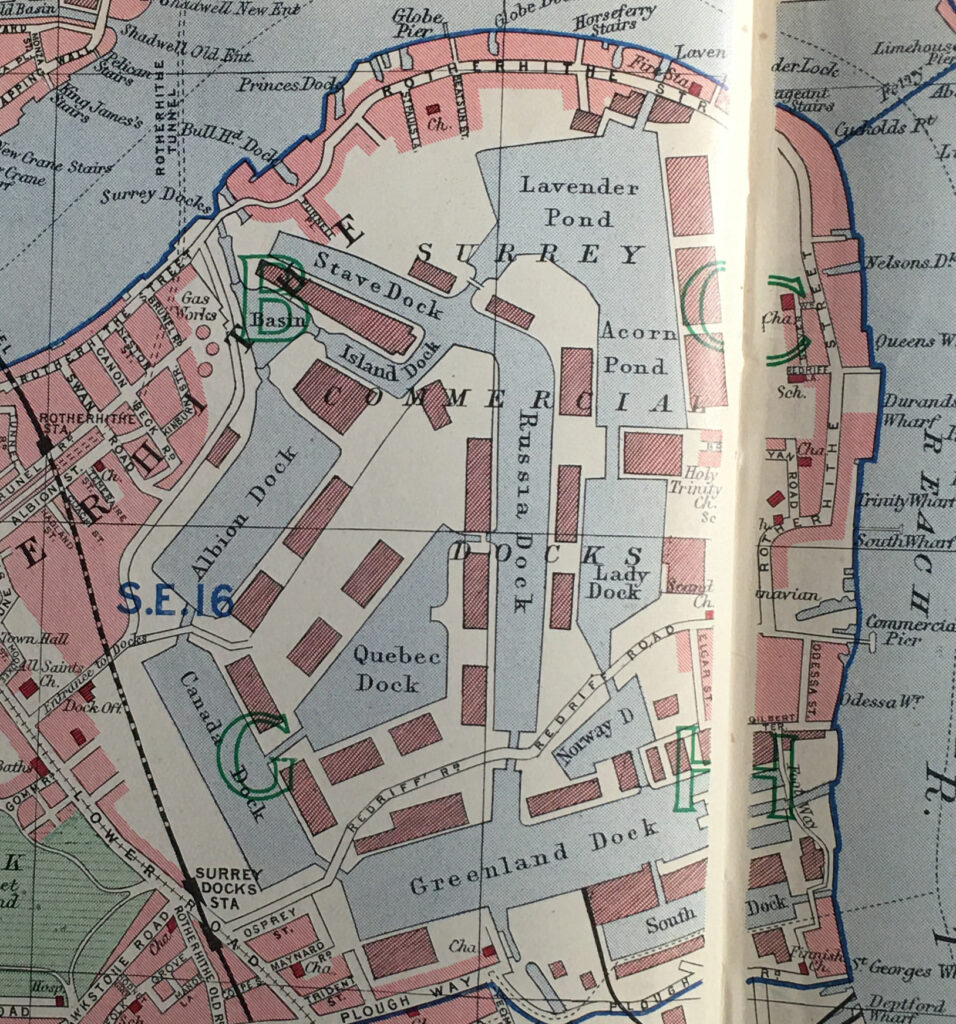

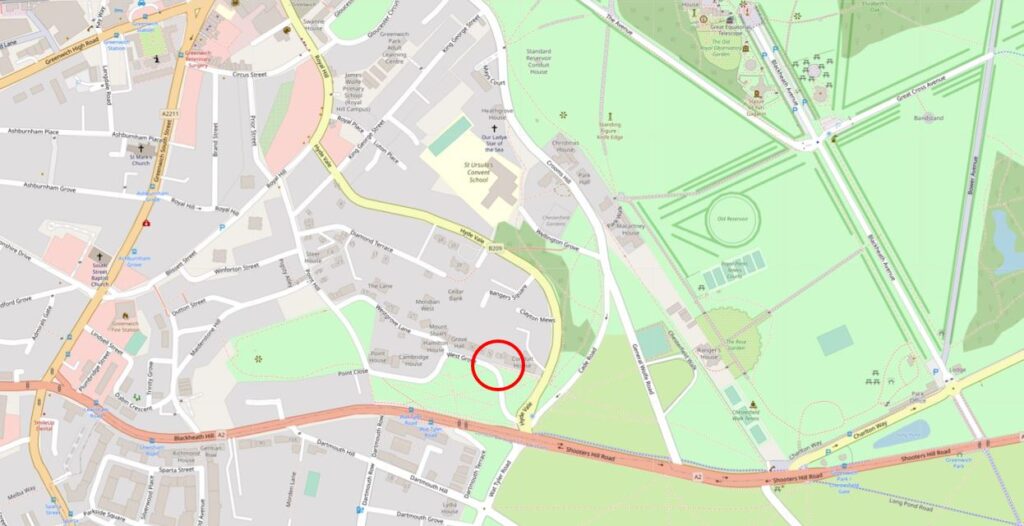

The Grove is today called West Grove and is separated from Blackheath Hill by an area of grass, and on what is today the A2 as the main route from London to Kent and the channel ports. The Chocolate House was at an ideal location to attract passing trade. I have marked the location of the Chocolate House on the following map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

There were a number of Chocolate Houses in eighteenth century London, with Blackheath being described as one of the five most important. They were:

- Blackheath Chocolate House – was much favoured by officers from Woolwich

- The Cocoa Tree in Pall Mall, on what is now 87, St James’s, Pall Mall, gave its name to the Cocoa Tree Club, the oldest of existing London clubs. It was famous as a resort for Tory politicians.

- Lindhart’s was in King Street, Bloomsbury

- The Spread Eagle in Bridge Street, Covent Garden

- White’s the most famous of any, was started in 1698, and was at the southern end of St James’s Street.

Having found the location of the Blackheath Chocolate House, there is one more story of those who had at one time passed along Tower Stairs, a delegation from the US, when:

Cherokee Indians Visit London

Reading through newspaper reports mentioning Tower Stairs, I found the following from the Oxford Journal on the 24th July 1762 – a report I was not expecting to find of some rather unusual visitors to Tower Stairs:

“This day the Cherokee King, and his two Chiefs, went in their Coach to the Tower-stairs, and about half an hour after Ten o’Clock, went on board the Admiralty Barge, in which they proceeded down the River to Deptford, Greenwich &c.”

The British had established an alliance with the Cherokee nation early in the 18th century, with both a trading and military alliance. This was important as the Cherokee were one of the major native American tribes and controlled land across what is now the states of Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia.

An earlier Cherokee delegation had visited London in 1730 when a group of seven Cherokee, led by chief Oukanaekah spent time in London and had several meetings with King George II at Windsor Castle. This led to a treaty where the British supplied military equipment and the Cherokee agreed to trade only with, and fight alongside, the British.

The relationship between the Cherokee and British was tense at times, and the British did occasionally attack and burn Cherokee villages.

The Cherokee fought with the British against France and during the American War of Independence.

A member of the British Virginia Militia was instrumental in arranging the visit to London. Henry Timberlake had lived with the Cherokee for a number of months and was asked by Chief Osteneco for an opportunity to visit England and to meet with the King.

After sailing across the Atlantic (during their voyage their interpreter died which caused problems until a new interpreter could be found), they arrived in Plymouth and then traveled across country to reach London, where newspapers described their appearance:

“The Cherokee Indians lately arrived in Town, are tall men, six feet high, dressed in a shirt, trousers and mantel round them and their heads adorned with Shells’ Feather and Ear-Rings, unfortunately their interpreter died in his passage and they can now only express their wants by signs. They are shy of company, especially a crowd. This King’s business here is to pay his respects to our Monarch, with whom he has lately entered into alliance. In his own country, he can raise 10,000 fighting men.”

The following print shows the Cherokee leader, Osteneco (centre) with his two chiefs:

So what would a Cherokee delegation to London do in 1762. It appears they did much the same as a delegation from a country would do in London today. They were wined and dined, taken to shows, met key people such as the Lord Mayor and visited displays of military power.

I have been able to trace some of their itinerary as follows:

- 11th June 1762 – An Indian King and two Chiefs belonging to the Cherokee Indians arrived in London after landing in Plymouth from America

- 12th June 1762 – Cherokee Indians met the Earl of Egremont at his House in Piccadilly

- 28th June 1762 – King of the Cherokees, with his attendants, dressed in the English fashion, walked for some time in Kensington Gardens, and seemed highly delighted with the place. They dined with Governor Ellis.

- 3rd July 1762 – The Cherokee Chiefs were at Sadler’s Wells, and expressed great satisfaction at the entertainments of the place

- 7th July 1762 – At Vauxhall where they had a very sumptuous entertainment. The wines first set before them were Burgundy and Claret, which however they did not greatly relish. Others were then placed on the table, when they fixed upon Frontenac, the sweetness of which highly hit their palate and they drank of it very freely

- 11th July 1762 – Dined with the Lord Mayor at the Mansion House. They seemed greatly pleased with the numerous concourse of ladies and gentlemen who crowded the windows &c. to see them pass

- 23rd July 1762 – Mr. Montague conducted the Cherokee Chiefs to the Parade in St James’s-Park; they happened to enter the Guard Room just as the Grenadiers were fixing their bayonets in order to Troop the Colour. The formidable appearance of the men and the business that accidently were engaged in threw them into such agitation that it was with the utmost difficulty they were persuaded to advance a step on the parade. They had a suspicion of treachery, were extremely impatient to be gone, and when they got home defined to see no more of those warriors with caps.

- 24th July 1762 – This day, the Cherokee King and his two chiefs, went in their coach to the Tower Stairs, and about half an hour after ten o’clock, went on board the Admiralty Barge, in which they proceeded down the river to Deptford, Greenwich, Woolwich &c. They were much delighted with the hospital. An entertainment was laid on for them at the Greyhound, and after dinner they saw the park and the Observatory

- 28th August 1762 – The Cherokee Indians, in a Landau with six horses, visited Winchester Camp; at its appearance they seemed greatly surprised

- 30th August 1762 – Arrive in Portsmouth and visit the Theatre.

- 31st August 1762 – They went on board the Epreuve Frigate, and the wind being fair, sailed directly back to America

Whilst in London, Joshua Reynolds painted Chief Osteneco:

Source: Joshua Reynolds, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Soon after the Cherokee visitors had returned to America, the War of Independence started. The Cherokee nation allied with the British, but in reality this was more against the settlers who were continually moving closer to, and taking parts of Cherokee land.

As part of the War of Independence, in 1776 Osteneco led his forces against the Province of Georgia, however this resulted in the destruction of the towns occupied by Osteneco’s Cherokee tribes. He would then lead his people to the west and he eventually settled in the town that is today Chattanooga in Tennessee.

He died in 1780 at the house of his grandson Richard Timberlake. Henry Timberlake, who had lived with the Cherokee and was instrumental in bringing the delegation to London in 1762 was the father of Richard with one of Osteneco’s daughters being the mother.

After American independence, the British had no interest in the Cherokee nation. The following decades saw frequent skirmishes and battles with the forces of the independent state of America, and they would gradually loose their land and freedoms.

Today, Tower Stairs are hidden beneath the walkway to Tower Pier, however they were one of the key river stairs. Many thousands of people would have walked along these stairs, either passing to or from the river.

Of those thousands, four tell us a wider story of Press Gangs, the Frozen Thames, London’s Chocolate Houses, and when a delegation of Cherokee Indians visited London.

I just wish there was a conspicuous plaque naming these river stairs and providing some information on their history.