Walking between Tower Bridge and the Isle of Dogs back in early March, I crossed the entrance to Limekiln Dock. The tide was out and the dock presented the strange view of being completely empty of water.

Limekiln Dock is a relatively short expanse of water leading off from the Thames at Limehouse. Over the last few centuries the dock has been called several variations of the name, including Limekiln Creek, Limehouse Creek and Limehouse Dock.

Limekiln Dock seems to be the most commonly used name.

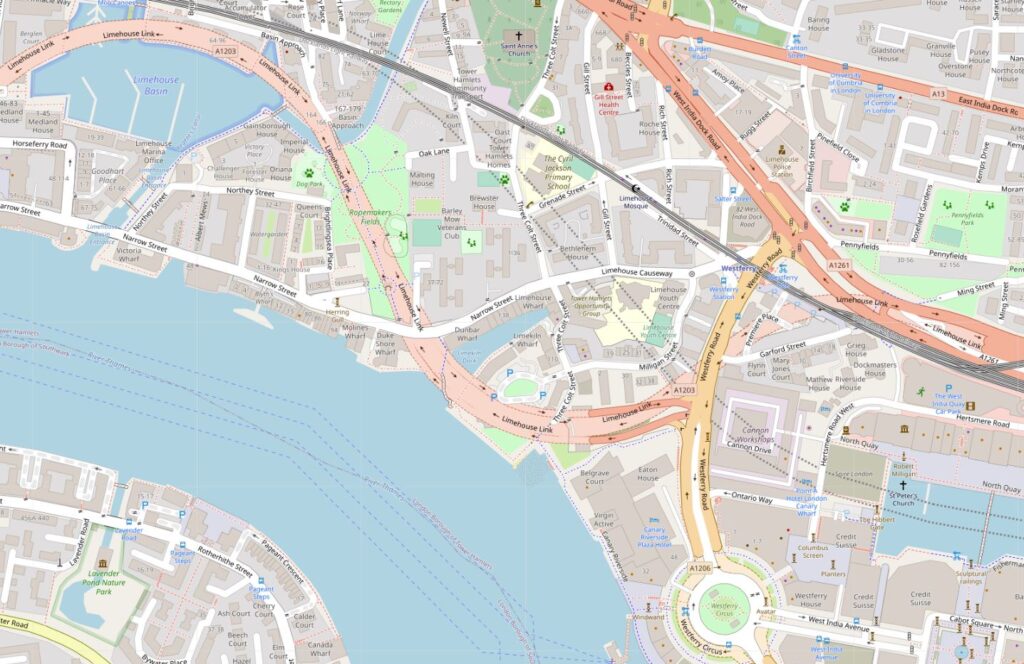

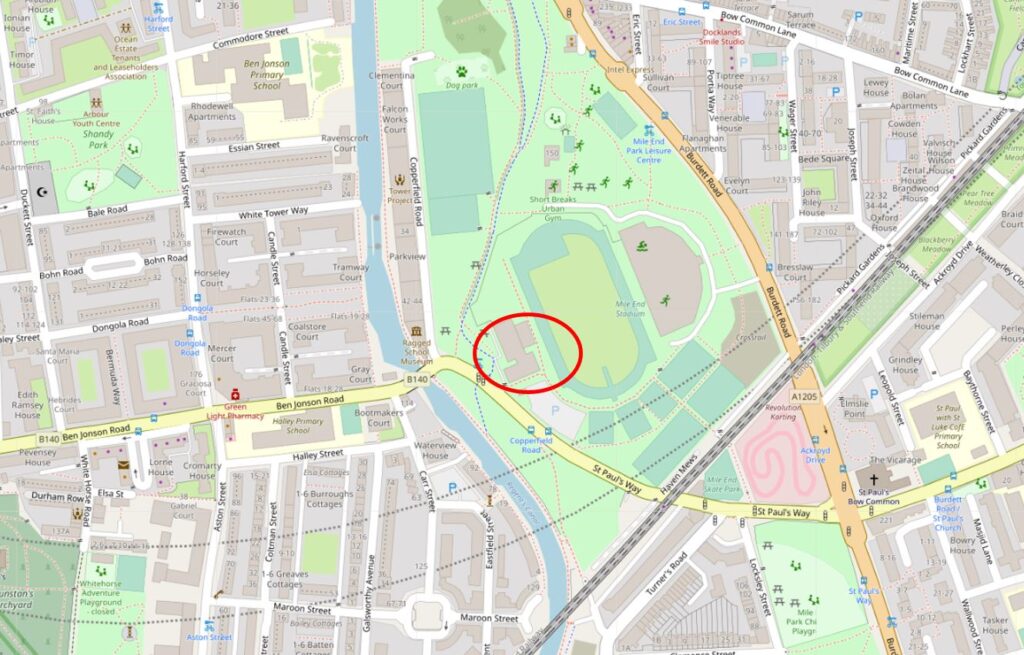

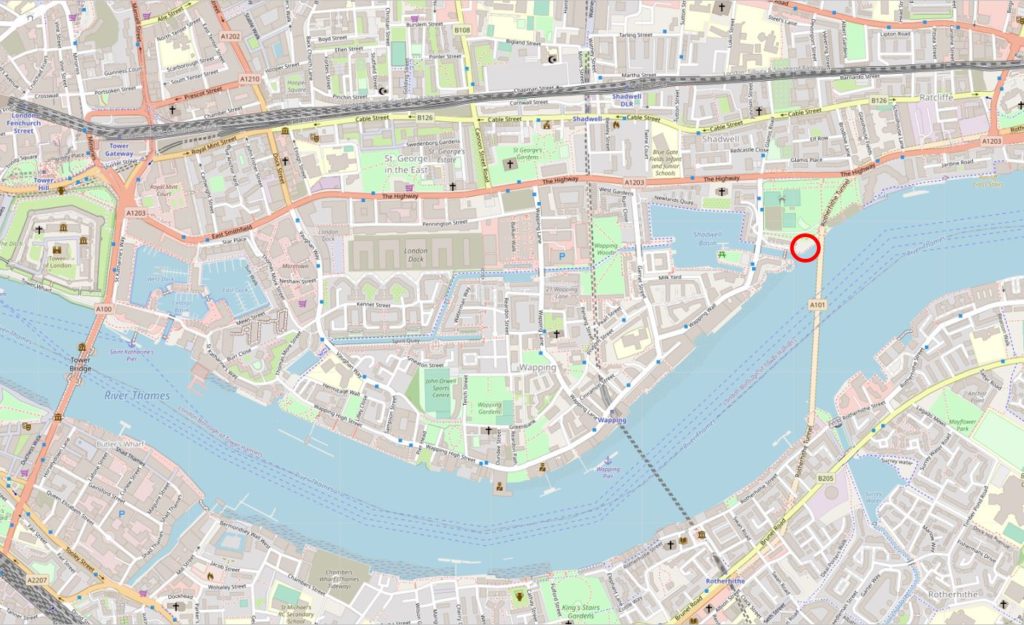

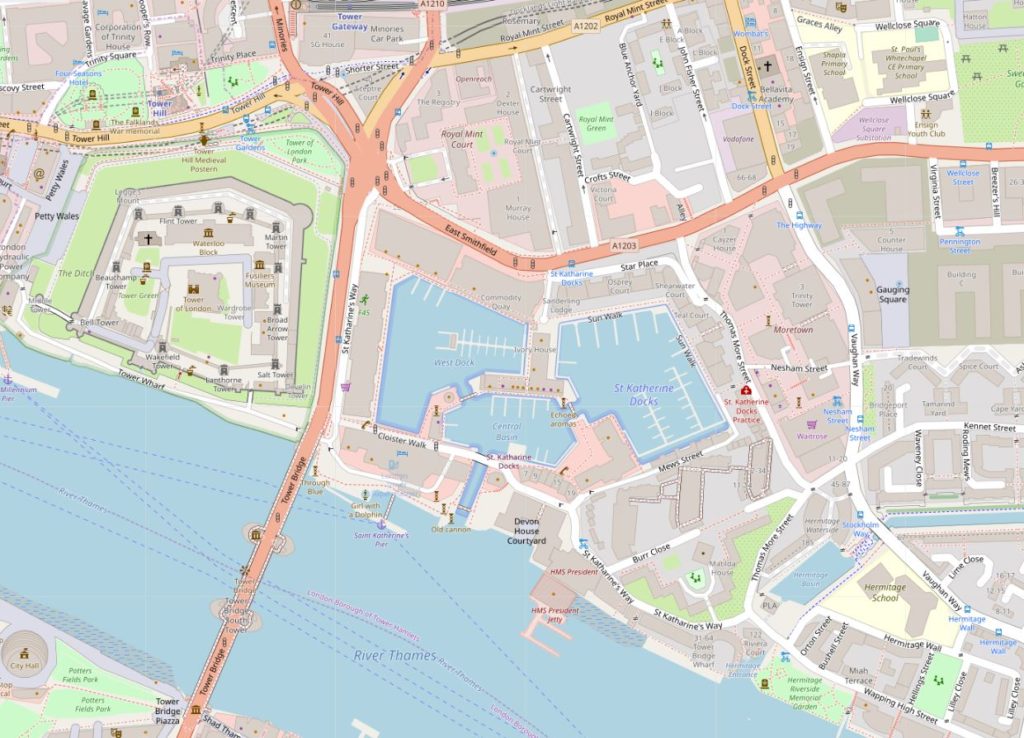

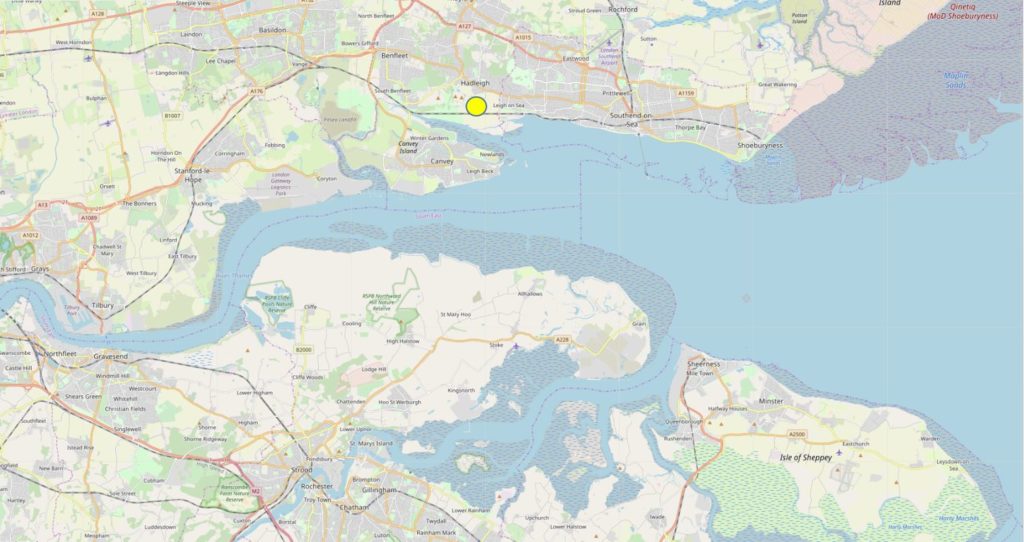

The following map extract shows Limekiln Dock in the centre of the map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

The map implies there is a road running over the entrance to the dock. This is the Limehouse Link Tunnel and runs underneath the entrance to the dock – the lighter colour used for the road on the map shows the extent of the underground routing.

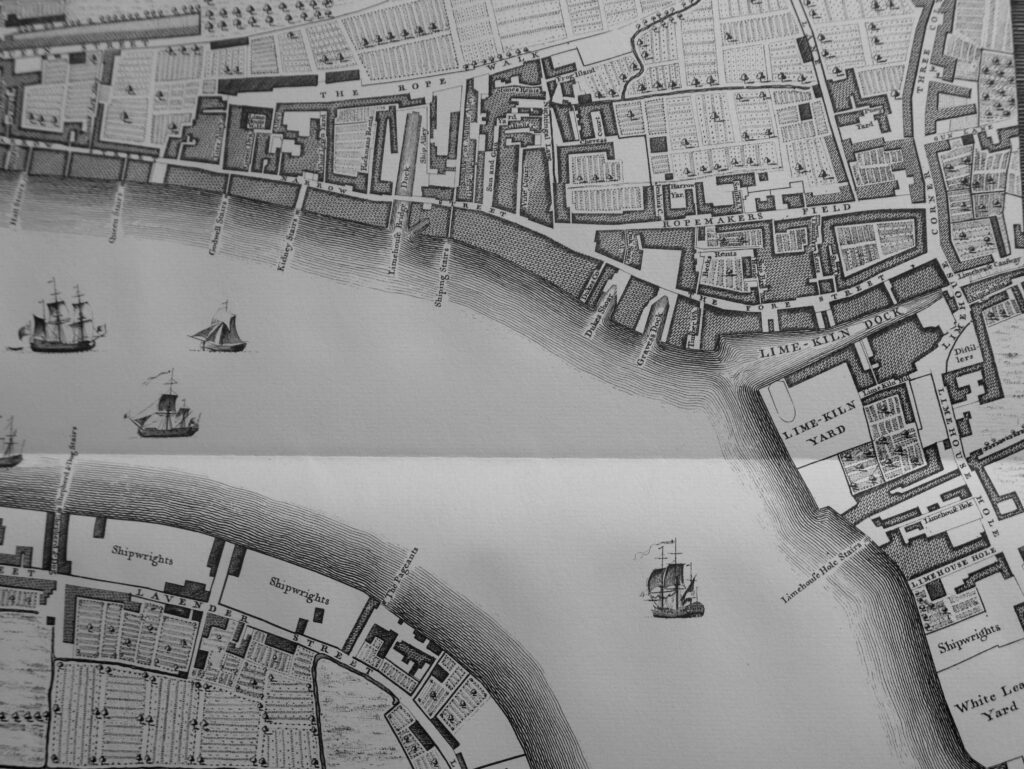

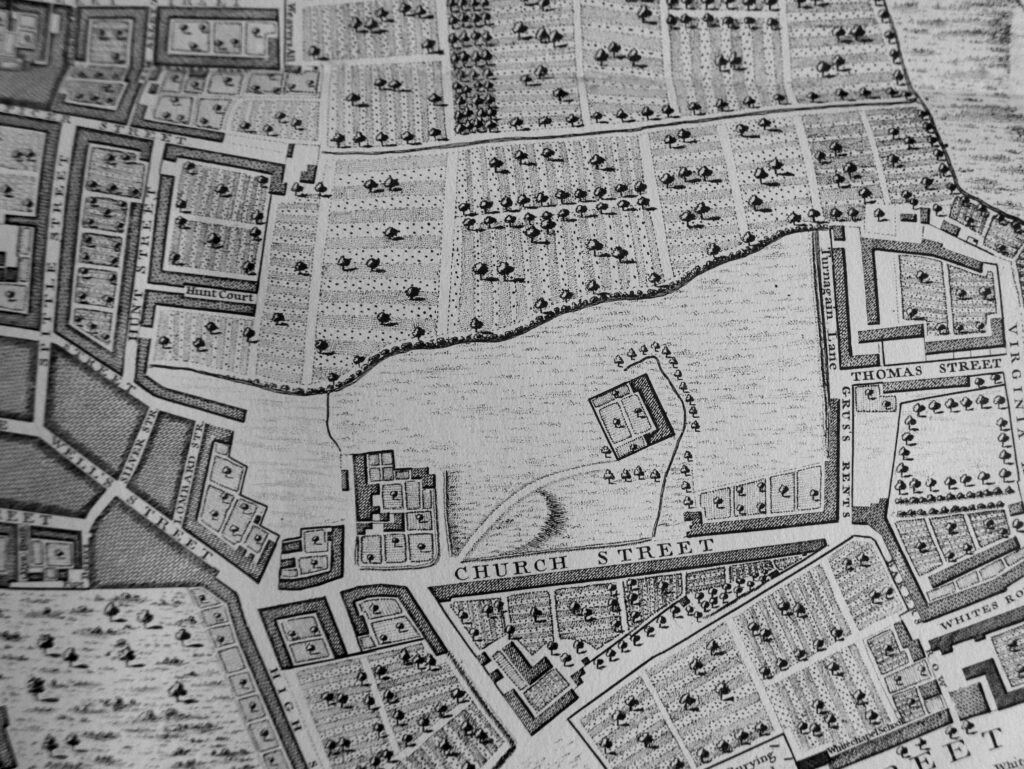

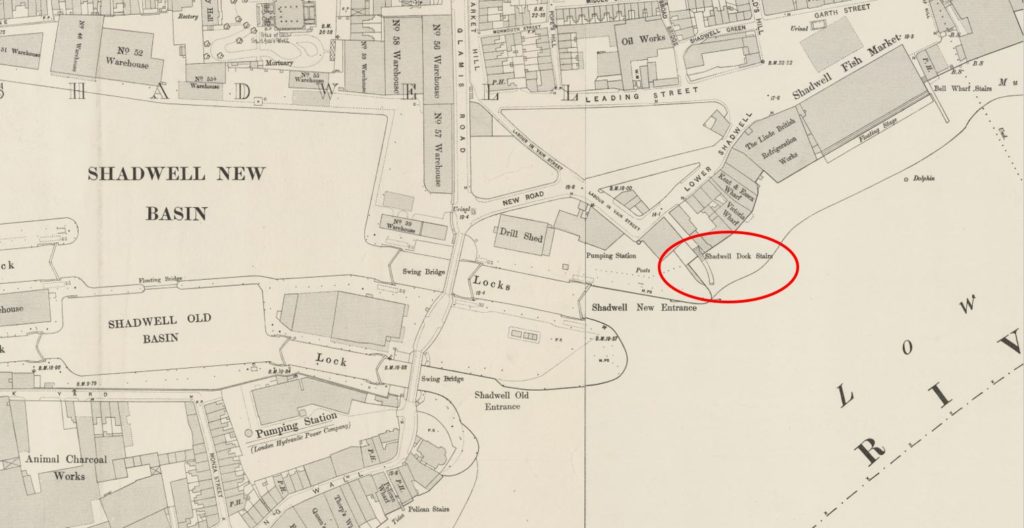

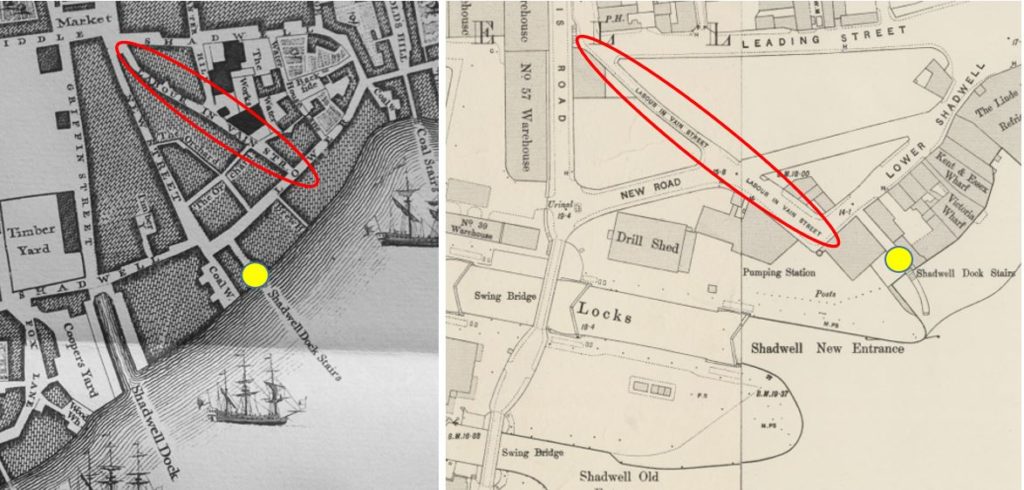

Limekiln Dock is an old feature. In the following Rocque map extract from 1746, the dock is to the right.

Rocque shows that on the southern side of the dock entrance was Lime Kiln Yard. This was the location of the lime kilns that as well as giving their name to the dock, were also the origin of the name Limehouse.

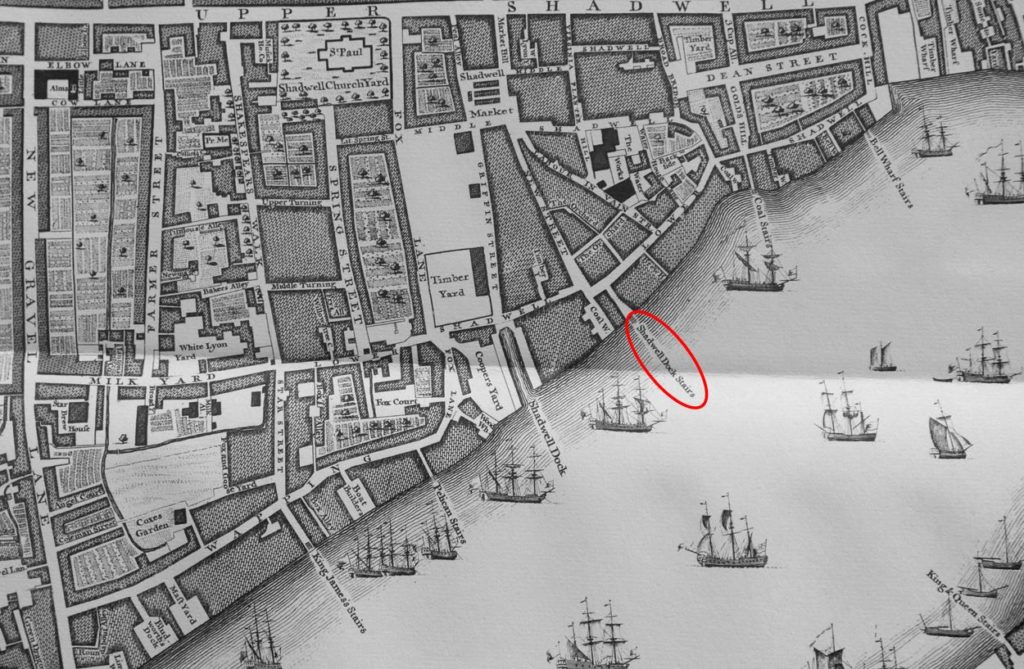

The following extract from Haines & Son map of 1796 also shows Limekiln Dock to the right of the map.

The views of Limekiln Dock in the two 18th century maps show an inlet from the Thames, wider at the entrance, and tapering along the length of the dock. It was not the shape of many other docks along the river, which were more of a rectangular shape, with the full width of the dock staying almost constant along the length.

The reason for the shape of Limekiln Dock is that it is a mainly natural feature. Whilst the shape may have been modified over the years, the dock is the shape it is as it was the entry point into the River Thames of the Black Ditch.

The Black Ditch is one of the many London rivers and streams that has long been hidden underground, becoming part of the City’s sewer system.

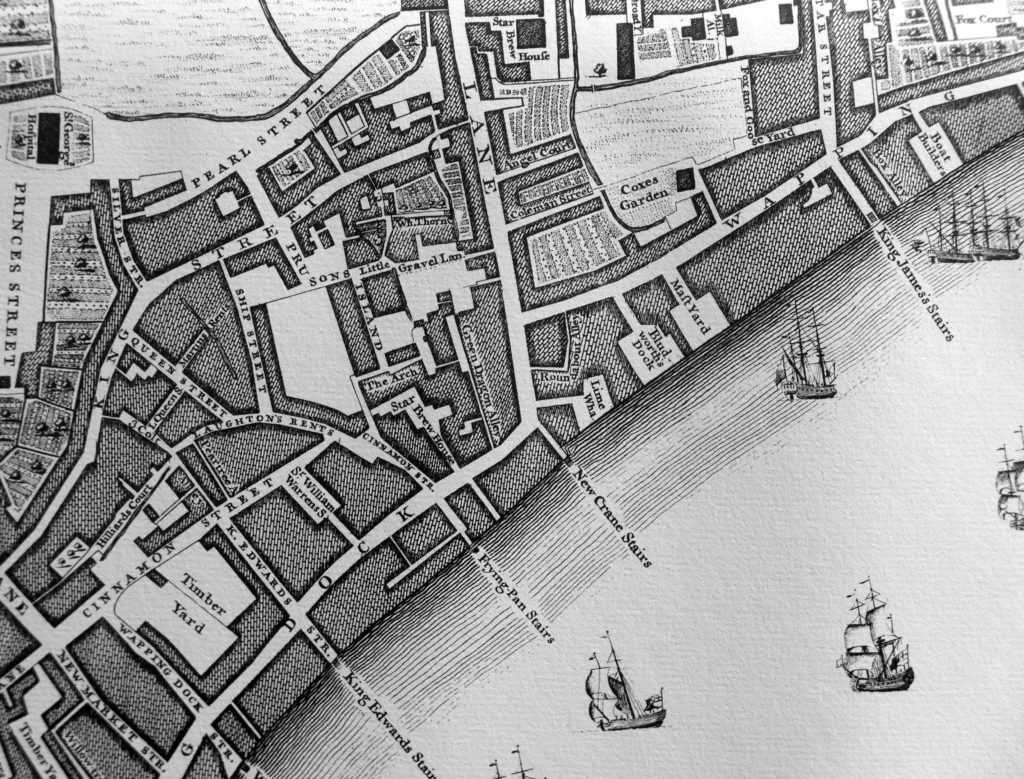

As can be seen in the two maps, during the 18th century, the city was extending along the Thames and had reached Limehouse, although still the majority of building was located close to the river. Inland, most of the area was still field and agricultural, although long rope walks could be found, where the open space provided the large elongated area needed for the manufacture of ropes for the shipping industry.

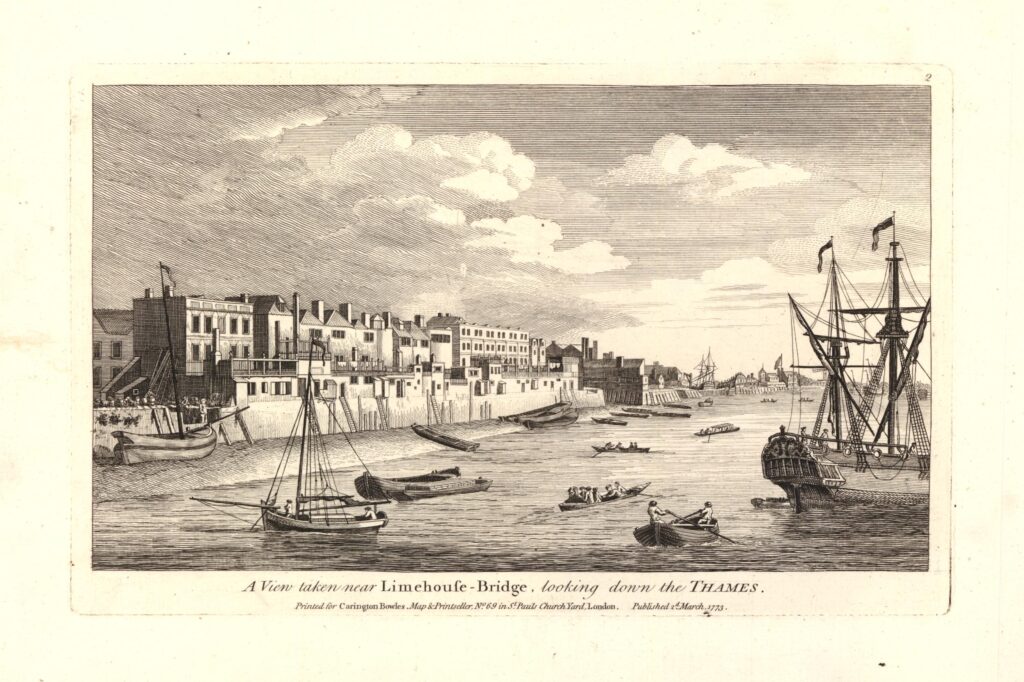

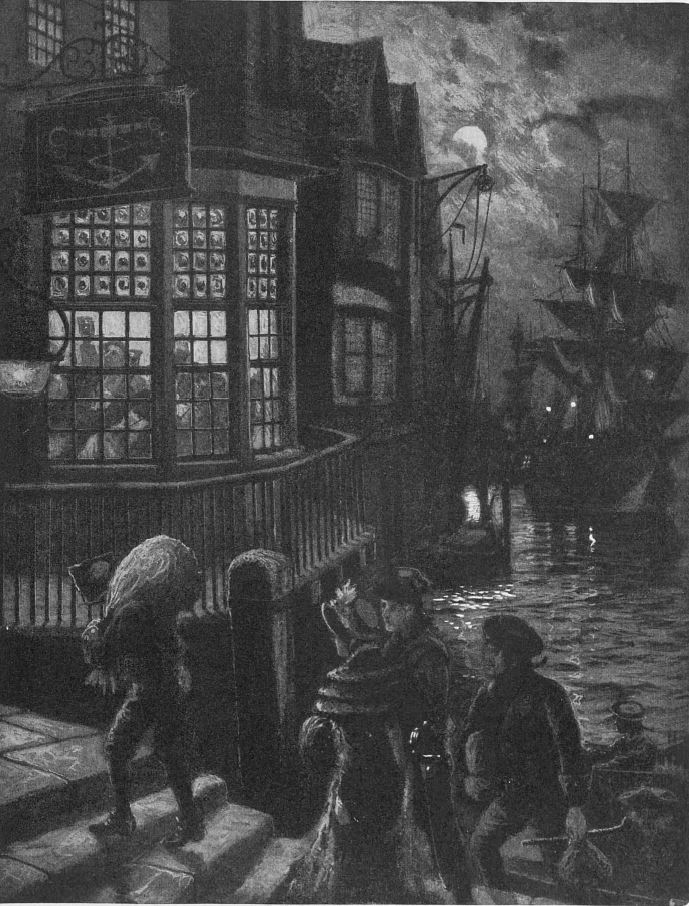

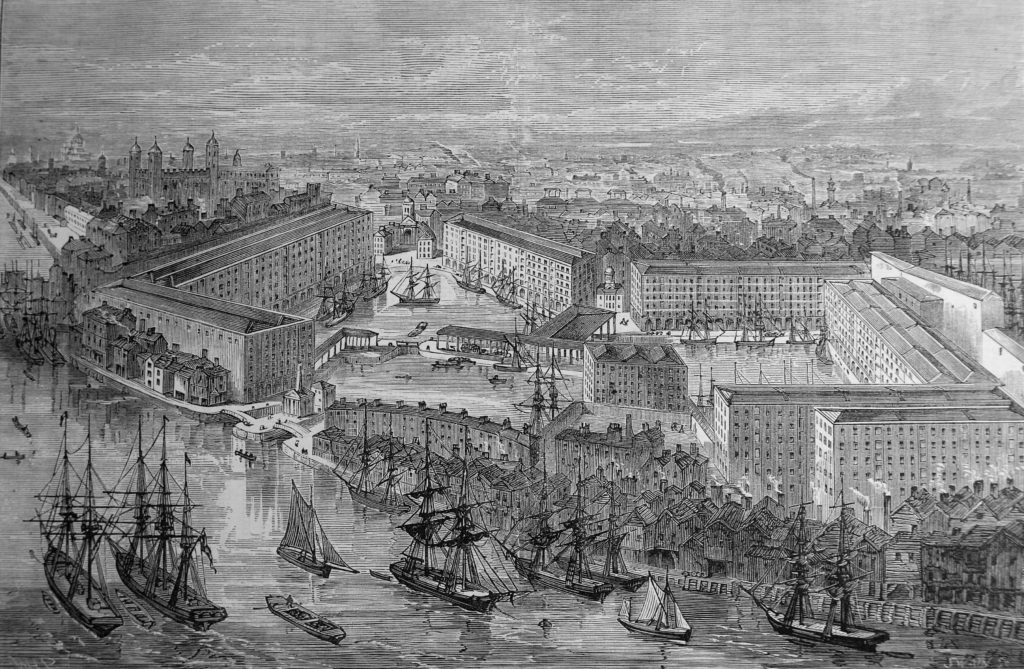

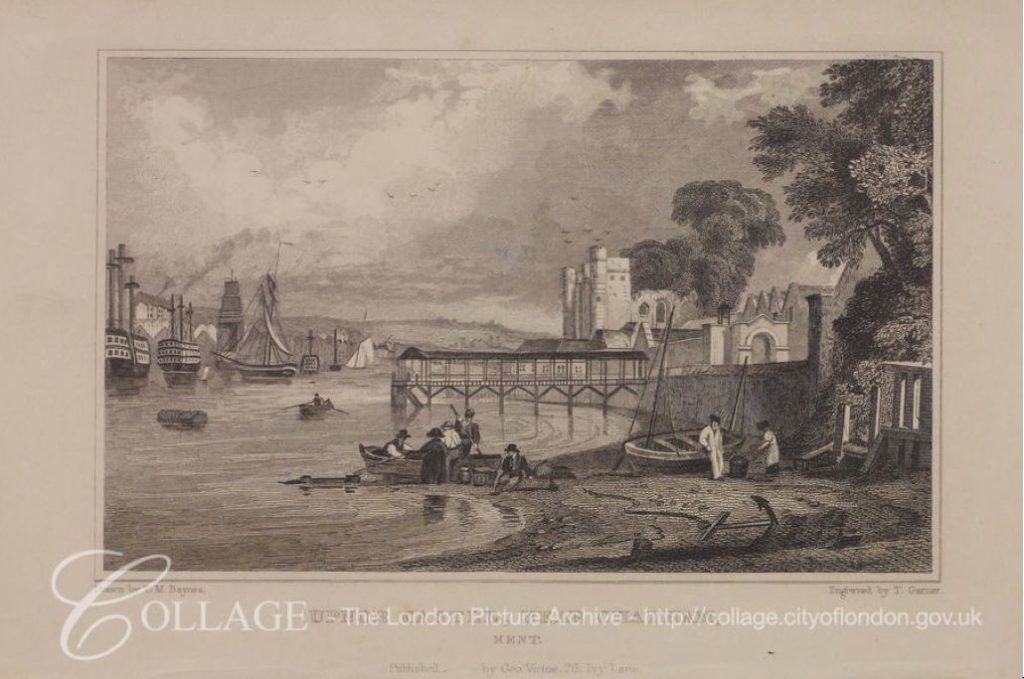

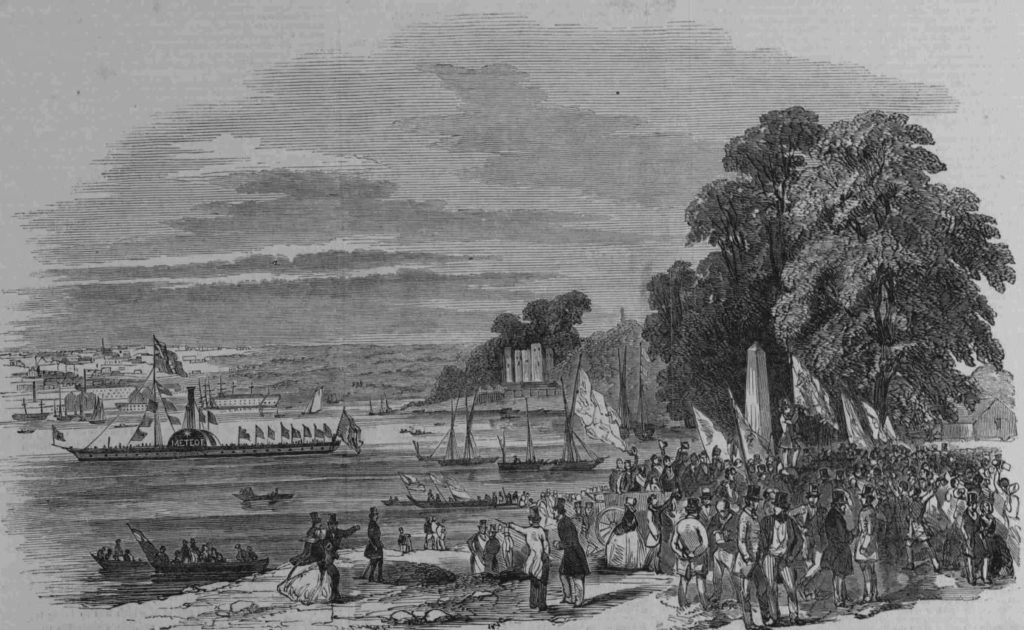

We can get an impression of the area from the following 1773 print. The entrance to Limekiln Dock is just visible, about three quarters of the way along the shoreline © The Trustees of the British Museum.

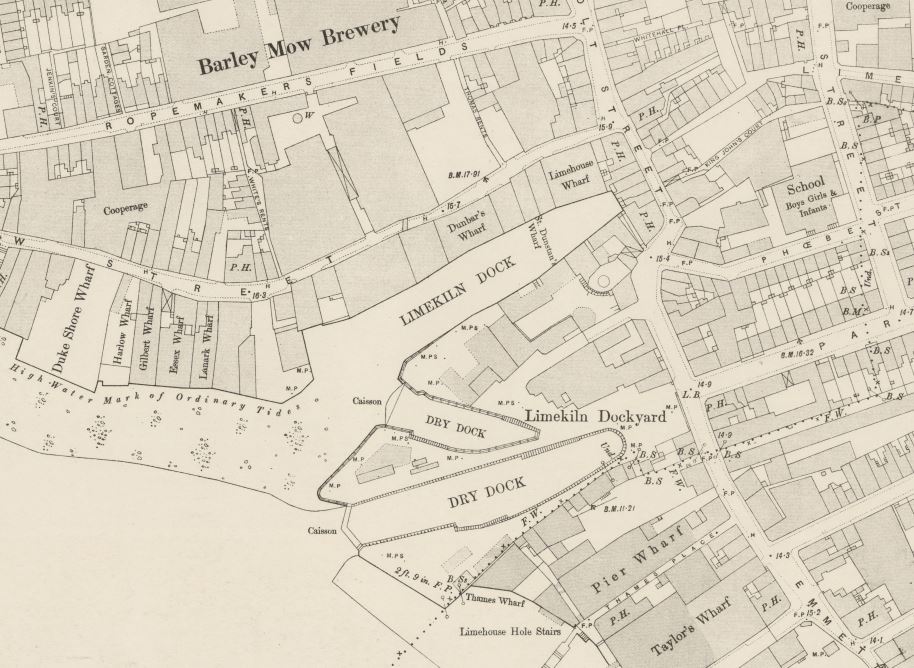

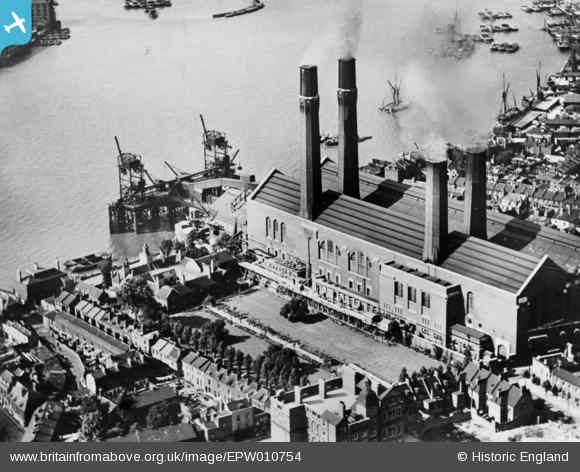

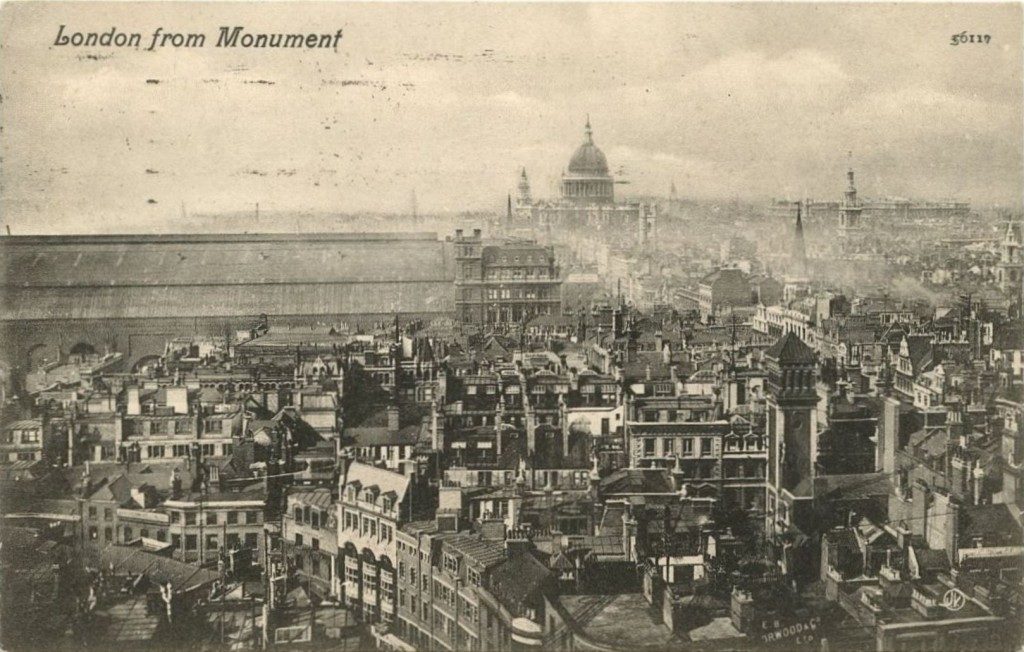

The whole area saw a dramatic increase in industry and housing during the 19th century, and by 1894, Limehouse was a large area of East London, covered in streets, warehouses, factories and terrace housing.

Limekiln Dock had grown a Dry Dock, with a second Dry Dock built just to the south of the entrance, all part of Limekiln Dockyard – it seems that the original Lime Kilns had disappeared many years earlier ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’ ..

Walking along Narrow Street, Three Colt Street and Limehouse Causeway, it is not obvious that Limekiln Dock is there – hidden behind the old warehouse buildings and the recently constructed apartment buildings.

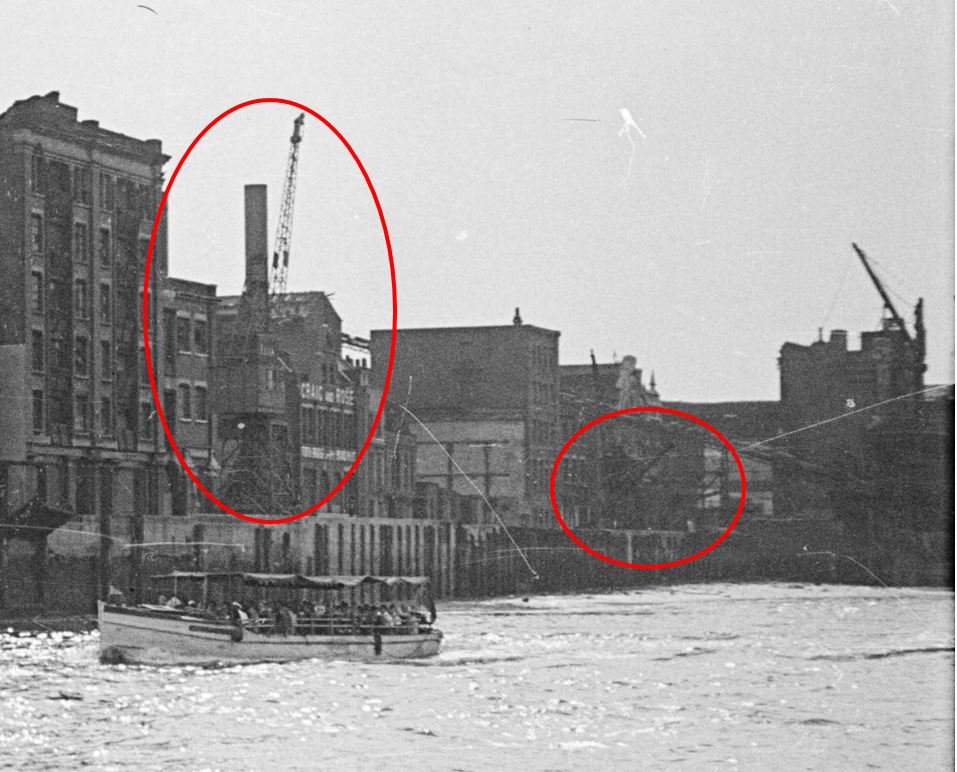

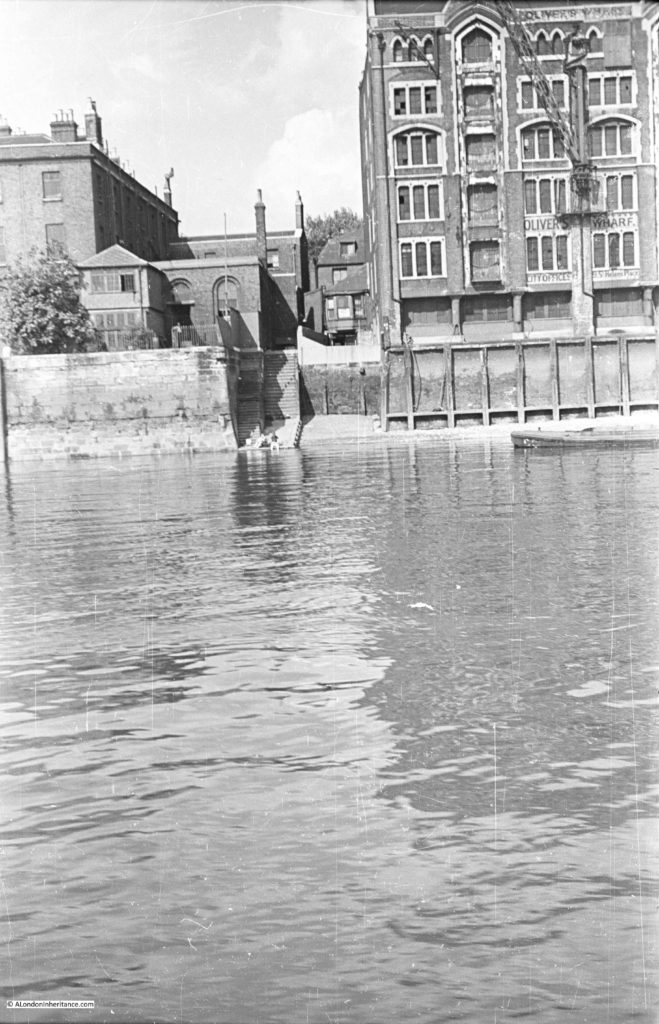

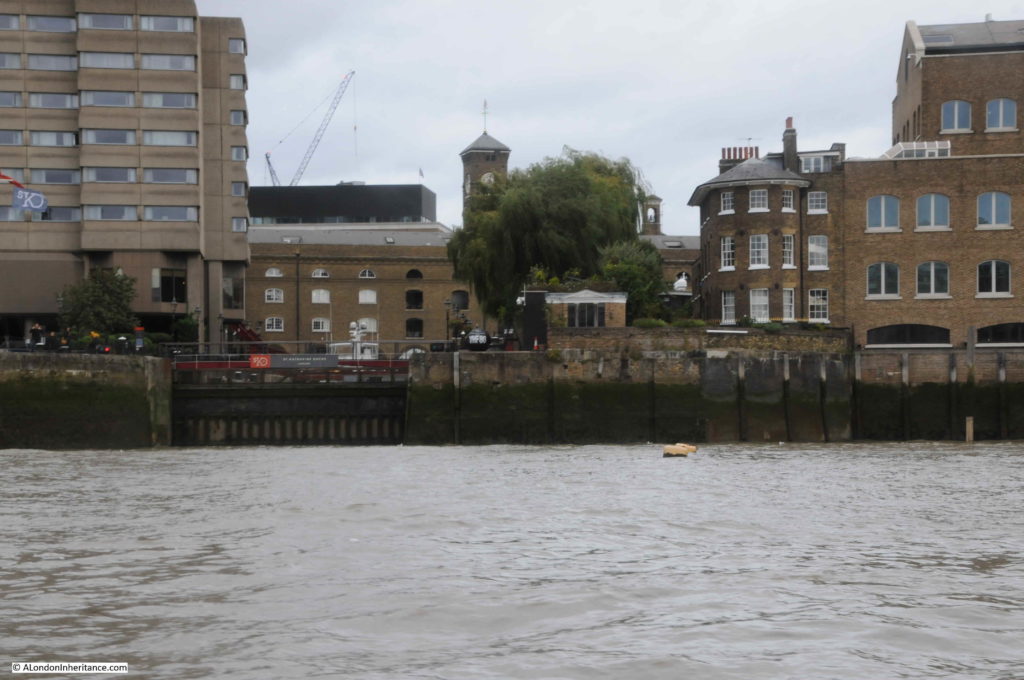

The photo at the start of the post was taken from the footbridge that now crosses the entrance to Limekiln Dock, and from on the river, we can get a good view of the entrance to Limekiln Dock today.

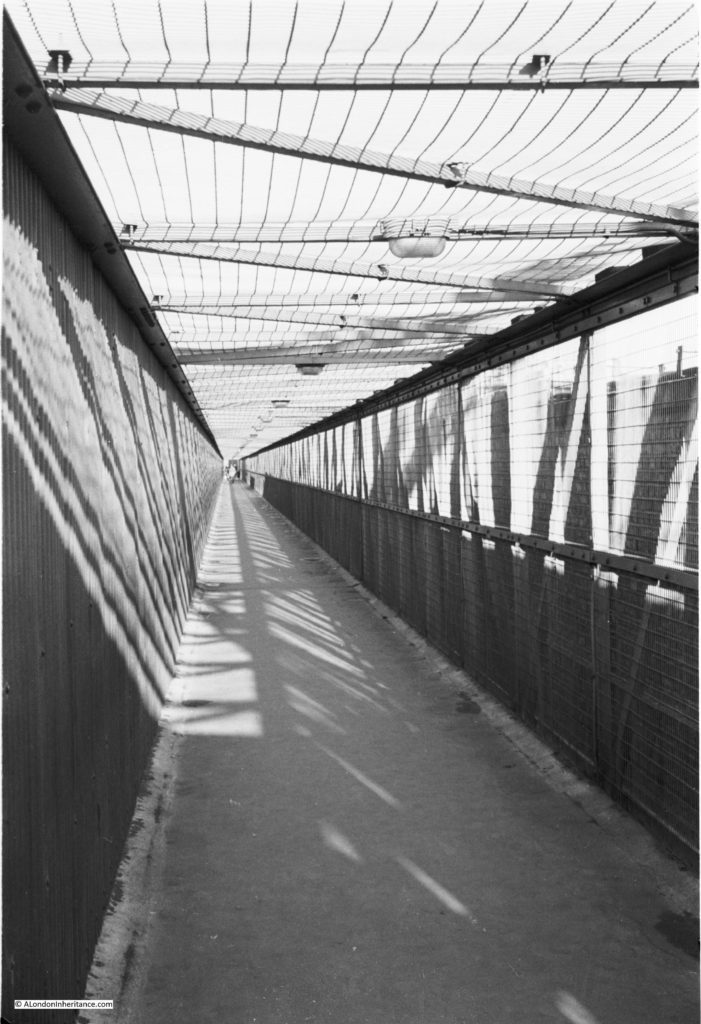

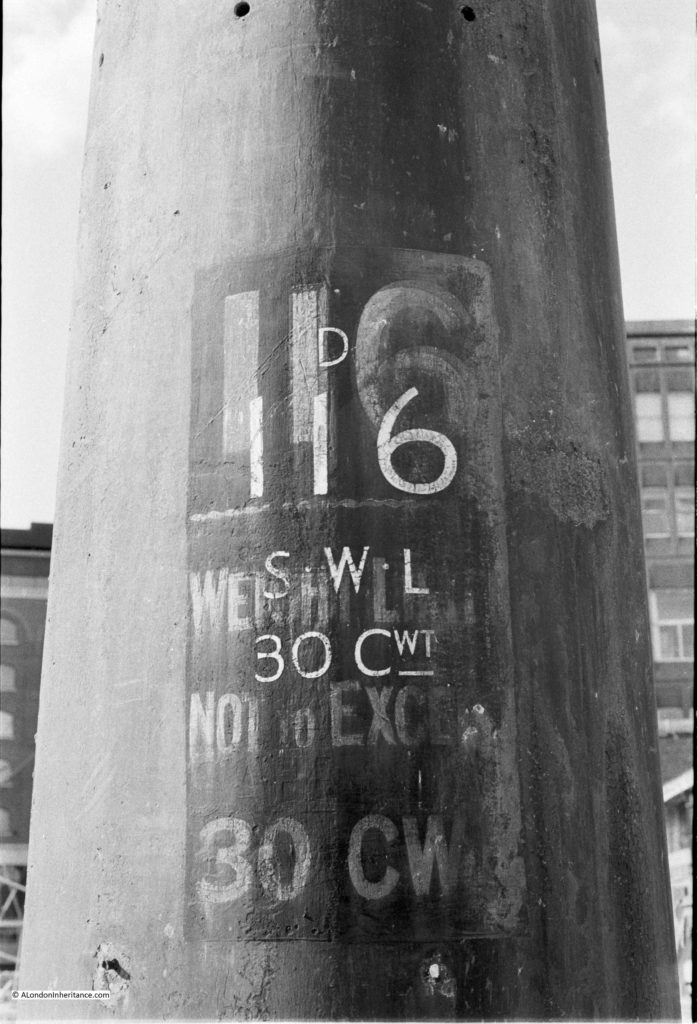

The footbridge is a swing bridge as there are historical rights to bring ships into the dock and moor at the warehouse buildings, although I suspect that this very rarely happens. The bridge was completed in 1996 and designed by YRM and Anthony Hunt Associates and built by Littlehampton Welding.

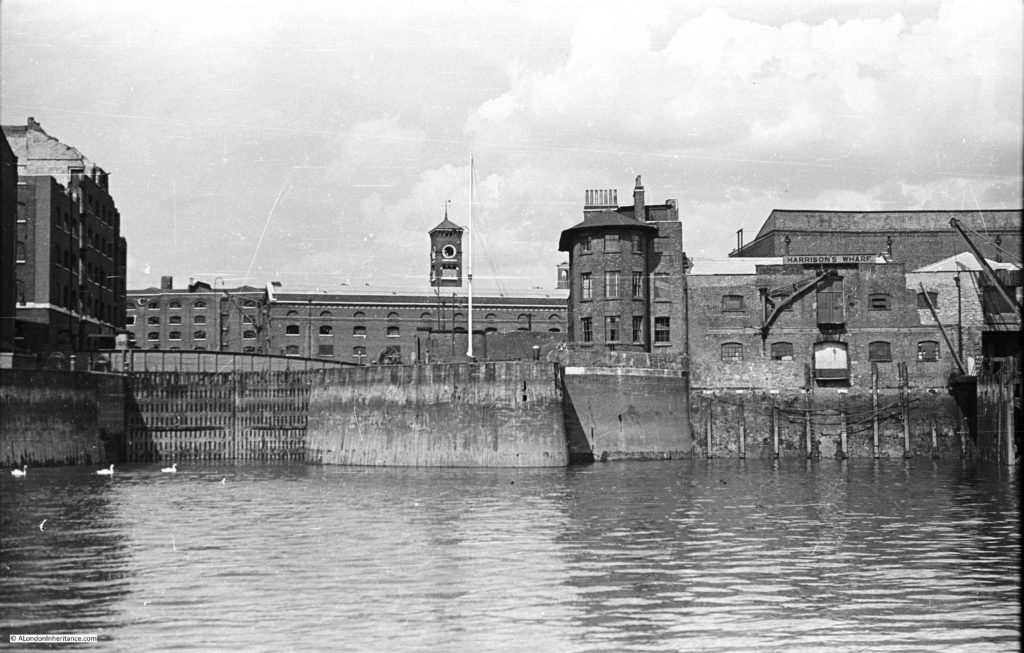

The photo above shows all the new apartment buildings that now line the majority of Limekiln Dock. These have been built over the last 30 years, and in 1981, the entrance to Limekiln Dock looked very different:

The only buildings that remain from the 1981 photo are some of the older buildings visible in the above photo towards the end of the dock.

I love finding little details in these photos which are the same, despite significant change in the area. If you look at the right hand corner of the dock entrance, on both photos there is a section with vertical lines, perhaps reinforcing rods. There is also the same crack visible leading down to the base of the wall, although in the 2020 the crack seems to have extended higher.

I have enlarged the two sections below:

During the 19th century, Limekiln Dock was a very busy place, with goods being unloaded and loaded into the surrounding warehouses. It cannot though have been a very pleasant place to work as the state of Limekiln Dock was a continuing problem.

In a letter to the East Observer on the 27th February 1869, a Mr P. writes:

“THE LIMEKILN CESSPOOL – On several occasions the Limekiln-dock has been alluded to at the Limehouse District Board, as the common receptacle for the sewerage of part of Fore-street, and also being a harbour for a large portion of the animal refuse of the Thames. The place alluded to is Limekiln Creek. The sanitary condition of the place may be seen by any of your readers who will ask permission of several occupiers of houses adjoining the abominable place; we hear of fevers and other contagious diseases being prevalent. Need we wonder ! What will be the consequence if the present mild winter is succeeded with a warm spring?”

The letter was one of the few places I found the word Creek being used rather than Dock. The state of the dock was obviously a long standing problem, as 24 years later, the responsibility for cleaning Limekiln Dock had reached the courts. From the Standard on Thursday December the 14th 1893:

“The Conservators of the Thames V. The Sanitary Authority of the Port of London – This was a specially constituted Court for a hearing of a special case stated by Mr. Mead, Metropolitan Police Magistrate, sitting at the Thames Police-court, in respect to a dispute between the Corporation of the City of London, in their capacity as Sanitary Authority for the Port of London, and the Conservators of the Thames.

The dispute arose in reference to the cleansing of Limekiln Creek, at Limehouse. The Creek, which runs inland some 500 feet from the river is occupied by wharves on each side, is said to have become a public nuisance, and dangerous to health, through the accumulation of foul sewage matter, besides floating dead animals, refuse thrown from barges, &c.”

Initially, the Magistrate found in favour of the Corporation of the City of London, and that it was the Conservators of the Thames responsibility to clean Limekiln Dock, however on appeal, this was overturned and the responsibility was with the Corporation of the City of London as Sanitary Authority.

The following photo is of the far end of Limekiln Dock. You can see at the end there is a large pile of rubbish left as the tide has gone out. I suspect the dock has the same problem as the 19th century articles described where the incoming tide carried rubbish into the dock, which settled and remained at the end of the dock as the water then went out.

As well as everything that washed up from the Thames into Limekiln Dock, the dock also suffered from everything that was washed down the Black Ditch and into the dock as the Black Ditch’s access point to the River Thames.

The Black Ditch is one of London’s lost rivers and has not been very well documented. Most of the detailed routings come from the time when the Black Ditch was a sewer, and whilst the name was used for the full extent of the sewer, it may not have been the original route of the stream.

Care is also needed as the words “black ditch” seemed to have been used as a generic description of a polluted, dirty stream or ditch of water and there are a number of references to other black ditches across London.

The East London Observer had a fascinating regular column going by the name of Roundabout Old East London. The column would be packed with local history, although it is difficult to know how true there all were, but the columns always provide some interesting background information to East London at the time. In the 5th April 1913 column, there was reference to the river running from Limekiln Dock, but under a different name (although the Black Ditch was mentioned). The paragraph was headed The Barge River:

“It would seem from old records of place names in the parishes and hamlets along the Thames side, that Limehouse Hole was so-called because a stream – a Century ago called the Barge River – at that place found its way to the great River.

This effluent, which through the greater part of its course came to be little more than an open ditch, is now the Limekiln Dock Sewer. It is described in the first Metropolis Act 1855 as a Main Sewer of the Metropolis, as commencing at Bonner’s Hall Bridge, leading into Victoria Park, and it extends along Victoria Park-road, East side of Bethnal Green, Globe-road, White Horse-lane, and Rhodeswell-road. It passed under the Regent’s Canal at Rhodeswell Wharf, thence along the Black Ditch, Upper North-street; and discharges into the River Thames at Lime Kiln Dock.

For a considerable length before it entered the Thames the Barge River was tidal, even within living memory.

In 1835 there was an old resident of Narrow-street, Limehouse, who recalled through his father, some strange yarns of smugglers and Revenue Officers on the Barge River when it was navigable for ships and boats for a considerable distance at some seasons and tides.

There are vague references to this stream, and to another which probably joined it across what was afterwards called Bow Common by way of South Grove in the extreme west of Mile End Old Town in very old land records. Of this latter now subterranean river, the engineers of the extension of the Underground Railway made troublesome acquaintance when the tunnel was being constructed”.

I suspect that the use of the name Barge River was an error. I cannot find any other references linking the name to the Black Ditch. There are a few cryptic references to a Barge River near the Lee and in Tottenham, but that is it – I suspect the author was describing the route of the Black Ditch.

I checked the referenced 1855 Metropolis Act and it does not mention the Barge River, but does list the same route for the Limekiln Dock Sewer. The Metropolis Act is a fascinating document (if you like that sort of thing, which I do) as it lists all the main sewers across London in 1855, and there was a considerable number of them. Many were old rivers and streams, covered in and converted to sewers.

The route compares well with the route of the Black Ditch described by Nicholas Barton and Stephen Myers in The Lost Rivers of London. Running alongside Upper North Street, Rhodeswell Street and the east side of White Horse Lane.

One tributary then goes a short distance over Mile End Road to Globe Road. Where the book and article differ is that Barton and Myers do not have the Black Ditch heading up to Victoria Park. They have the ditch in three separate streams heading to Whitechapel, Spitalfields and Bethnal Green.

I suspect the 1855 Metropolis Act correctly routed the sewer which ran from Bonner’s Hall Bridge. Part of the route included the route of the Black Ditch, with pipes leading from the main sewer carrying the old Black Ditch to the destinations listed by Barton and Myers.

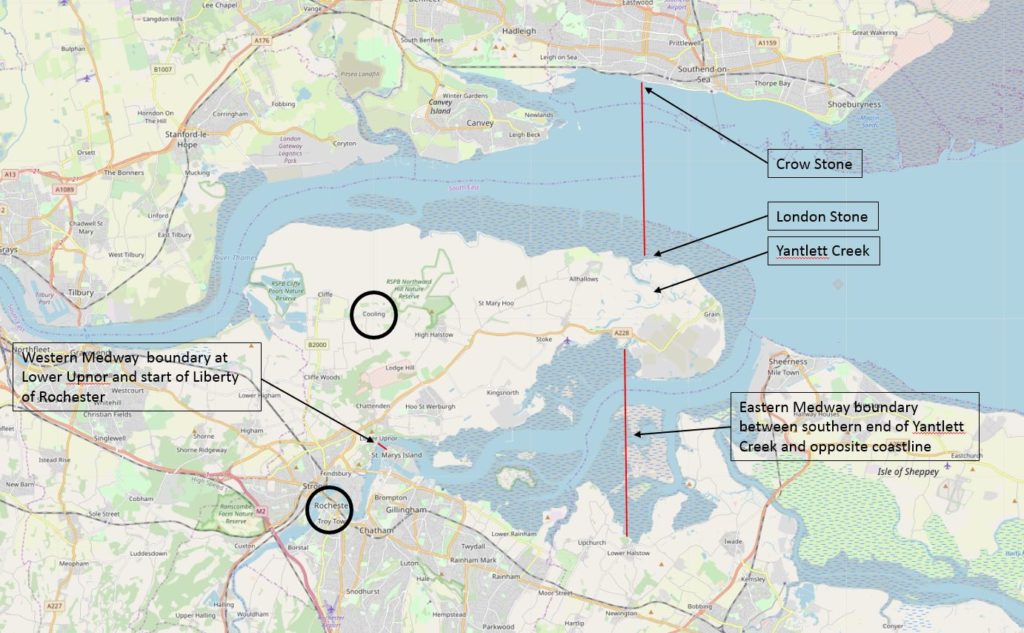

There are very few maps which show any part of the Black Ditch. Some show some tantalising river like features. For example, the following extract from Rocque’s 1746 map shows a river like line to the south of Rhodes Well.

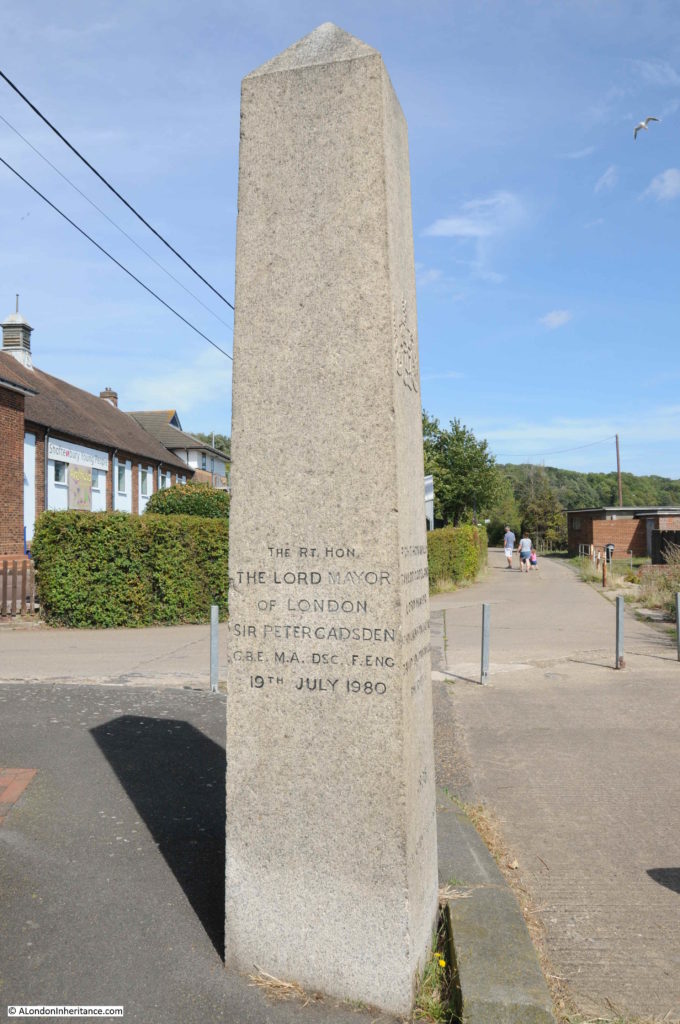

Rhodes Well is the source of the name Rhodeswell Road, and was located roughly within the red oval as shown in the following map extract – exactly where the Black Ditch was described as crossing the Regent’s Canal (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

Rhodes Well is the source of the name Rhodeswell Road, and was located roughly within the red oval as shown in the following map extract – exactly where the Black Ditch was described as crossing the Regent’s Canal (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

One of the tributaries of the Black Ditch was from Spitalfields and in the following extract from 1746, there is a wavy line forming a boundary between what appears to be cultivated fields to the north and grassland to the south. This must be a natural feature due to the irregular line which looks as you would expect of a stream.

The possible stream in the above map runs from the junction of Vallance Road and Buxton Street down to Woodseer Street on today’s streets, and is similar to the route mapped by Nicholas Barton and Stephen Myers.

The Black Ditch may have formed a boundary between Mile End and Bethnal Green. At a meeting of the Mile End Old Town Vestry in August 1877, the upgrade of a sewer was one of the points for discussion, and the sharing of costs between Bethnal Green and Mile End Vestries. During the meeting, it was stated that “The old sewer, as it had been called, was really no sewer at all, but the old black ditch through which the ancient boundary of the two hamlets ran. It was in a horrible state, and if not attended to at once, should heavy rains ensue, it was hard to say what might happen”.

The state of the Black Ditch had been the subject of complaint for many years prior to the work in 1877.

In 1859 it was described as the “receptacle for the sewage from a great number of houses”. The Black Ditch ran under houses for part of its route. In an 1831 murder investigation it was revealed that there was no problem with access to a house which was built over the Black Ditch as anyone could gain access to the premises from the Black Ditch than accessing the house above.

The route of the Black Ditch is on my list of future walks, however I suspect that there is very little to see of this lost river which now runs below the streets in London’s sewers, but it is always worth having a listen at any manhole covers along the route after heavy rains.

Returning to Limekiln Dock, lets have a look at some of the buildings that line the dock.

When walking along Narrow Street, it is not immediately obvious that the dock is behind the buildings, however the names of the buildings provide a clue.

Dunbar Wharf is one of the buildings that date from the time when Limekiln Dock was a busy dock on the Thames. Today, the building retains many of the original external features:

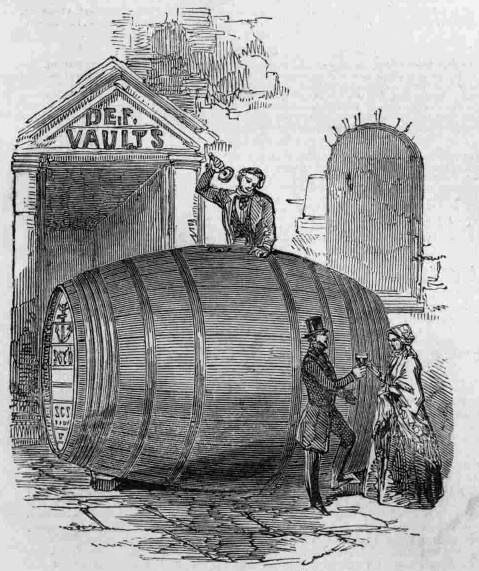

Dunbar Wharf was named after the Dunbar family who had a very successful business at Limekiln Dock.

The Dunbar family wealth was initially from a Limehouse brewery established by Duncan Dunbar. It was his son, also called Duncan, who used the money he inherited from his father to build the shipping business that was based at Dunbar Wharf.

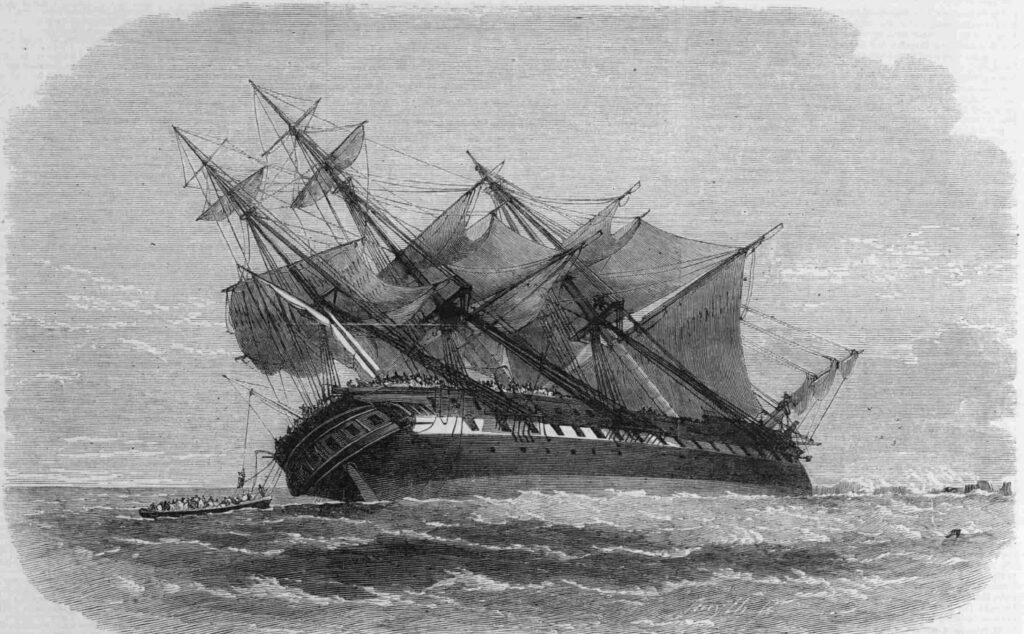

Dunbar’s ships carried passengers and goods across the world as well as convicts to Australia. Whilst very successful, this was not without the occasional disaster, as described in this article from the Western Times on the 7th November 1865:

“The Wreck Of The Duncan Dunbar – The passengers and crew of the Duncan Dunbar reached Southampton on Saturday morning on board the Brazil mail steamer Oneida. It seems that the vessel struck on the reef Las Rocas at about half past eight in the evening of the 7th of October, and an awful night was passed on board. On the following morning they were all, 117 in number, landed on a little island or bank of sand, which was covered with birds. They remained in this situation, with the exception of the captain, one of the passengers and six seamen, who started in a lifeboat to Pernambuco for aid, till the 17th, when they were fetched off by the Oneida. Though the sufferings, mental and bodily were indescribable, not a life was lost or a limb broken.”

The Duncan Dunbar stuck on the reef off the coast of Brazil.

The problem I find with researching a specific subject is that it always opens up another interesting subject, and so it was with Duncan Dunbar.

He was widely known as a “protectionist” in matters of trade, and the battle between trade protection and free trade came to a head in 1849.

During the previous couple of centuries, a number of Navigation Acts had been put in place which protected British trade, and gave a commercial advantage to British manufacturers, agriculture and shipping.

By the mid 19th century the Free Trade movement was pushing for the repeal of these acts, and the opening up of Global Trade.

A large meeting was held in the City of London in May 1849 of what were known as “Protectionists” and Duncan Dunbar was at the meeting and was elected to the committee – an indication of his reputation. An association was formed and went by the name of the The National Association for the Protection of British Industry and Capital. One of the resolutions passed stated:

“That it is of the opinion of this meeting, that the adoption of a Free Trade policy has failed to produce the national benefits predicted by its promoters; that it has been followed by deep injury to many of the great interests of this country; that a reaction in public opinion is widely diffused, and is rapidly extending in favour of just and moderate protection to the productions of the land, the manufacturers, and the industry of the United Kingdom and British possessions; and that it is of the utmost importance to the restoration of the prosperity to the nation, that the influence of agricultural, colonial, mercantile, manufacturing and shipping interests should be united in resistance to the further progress of experimental legislation”.

Duncan Dunbar and his fellow members of the new association were not successful, and the repeal of the navigation acts remained in force.

Duncan Dunbar died in 1862. The report of the funeral, published on the 17th March 1862 provides a view of the standing of Duncan Dunbar in London and the wider shipping community:

“Funeral Of The Late Mr Duncan Dunbar, the Shipowner – The funeral of the late Mr Duncan Dunbar, the eminent shipowner, took place on Friday at Highgate cemetery. The mournful cortege, which comprised ten mourning coaches and several private carriages, left the deceased gentlemen’s residence, Portchester Terrace, Bayswater, at 12 o’clock, and reached the cemetery shortly after 1 o’clock. the mourners comprised a number of gentlemen of high standing in the commercial world. At Poplar and Limehouse much respect was shown. Nearly all the shipping in the East and West India Docks had their colours hoisted half mast high, as also the flags on the pier head entrances of the docks, the lofty mast house at Blackwall and Limehouse Church, the bells of which tolled during the hours appointed for the mournful ceremony.”

Duncan Dunbar did not have any children so his wealth was divided across his wider family members, although no one in the wider family wanted to continue the shipping business. The ships and warehouses were sold, however Dunbar Wharf remains to this day as a reminder of a once highly successful shipping business.

As well as Dunbars Wharf, there are a number of other building remaining along Narrow Street that face onto Limekiln Dock, including Dunstans Wharf:

And Limehouse Wharf:

On the corner of Narrow Street and the southern stretch of Three Colt Street is an old pub:

This was the Kings Head, a late 18th Century / early 19th Century pub, that although it is still clear that this was once a pub, closed a long time ago, around the early 1930s after which it became the office of a banana importing business.

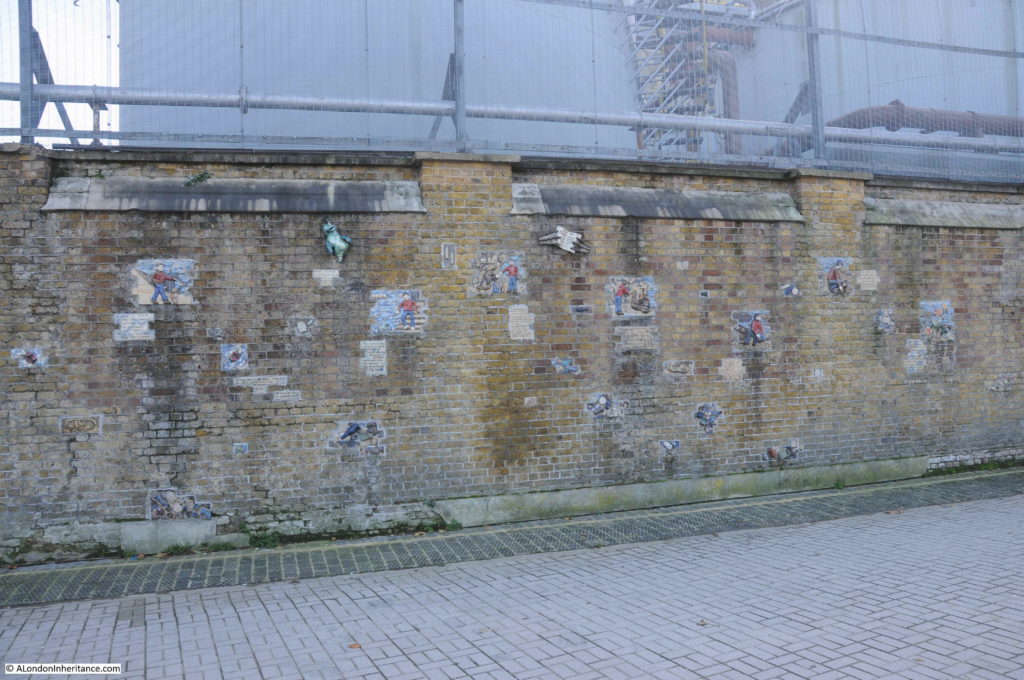

Walking along Three Colt Street towards the river is Limekiln Wharf, dating from 1935:

Further along is one of the new apartment blocks that now surround the entrance to Limekiln Dock:

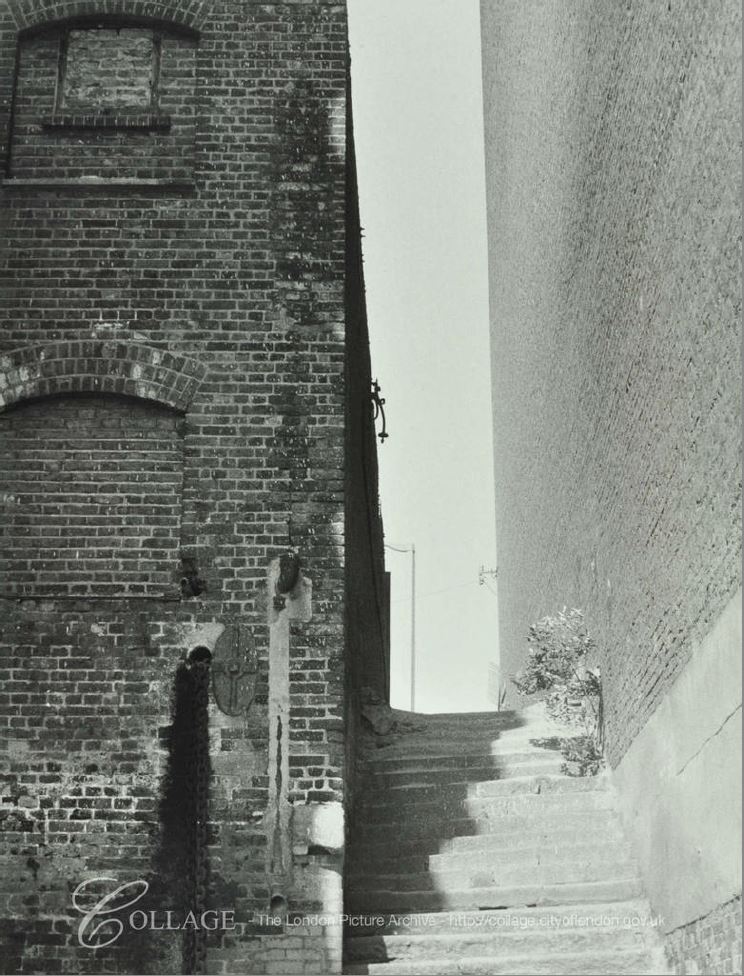

At the end of the wall with darker bricks, there is a dark green door built into the wall.

A rather faded plaque on the door provides some background:

“This is a replica of the door which served the old Limehouse built around 1705 and demolished in 1935. The original door was donated to the Ragged School Museum Bow E.3.”

Which really brings me back to where I started. The Lime Kilns at the southern entrance to Limekiln Dock that gave the dock its name, and indeed the area of Limehouse.

Standing on a new footbridge looking along Limekiln Dock opens up the history of the dock, one of London’s lost rivers that ran to Spitalfields and Bow, one of the 19th centuries most successful shipping companies, the tension between protectionism and free trade, and the location of Limehouse Lime Kilns.