A church that was not rebuilt after the 1666 Great Fire along with the churchyard lost in the late 19th century was the subject of last week’s post. For today, I want to take a look at two churches that have survived, both very old churches, and at the eastern end of Cornhill in the City.

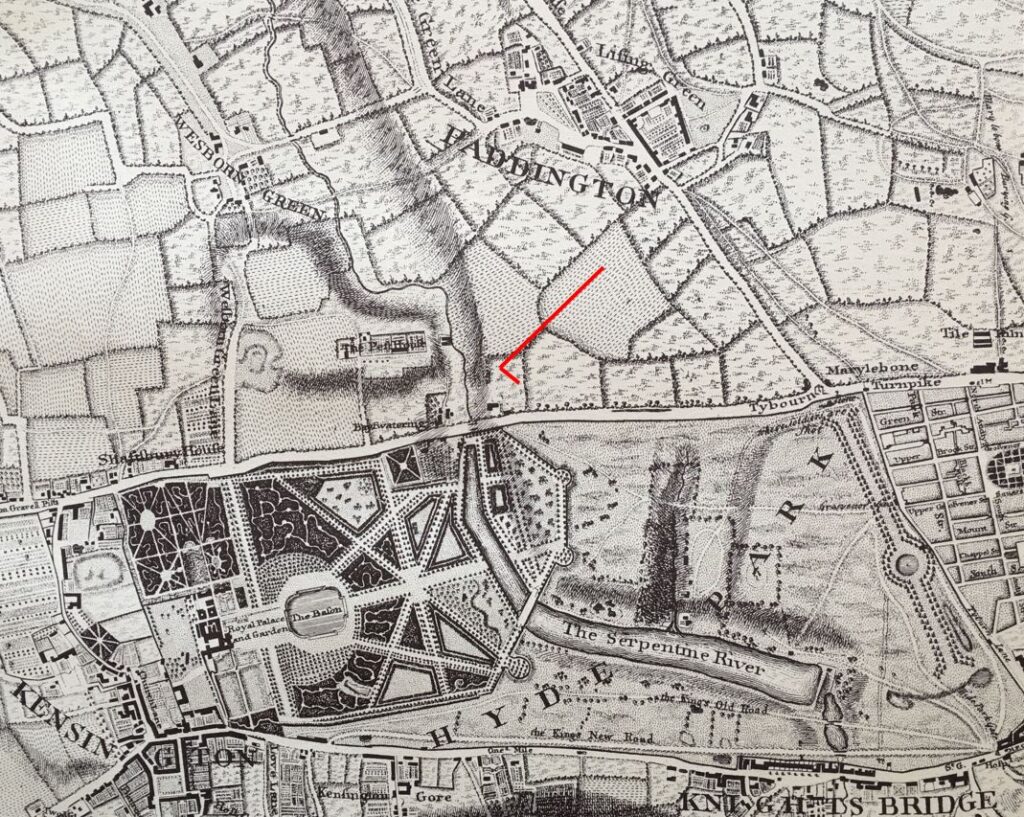

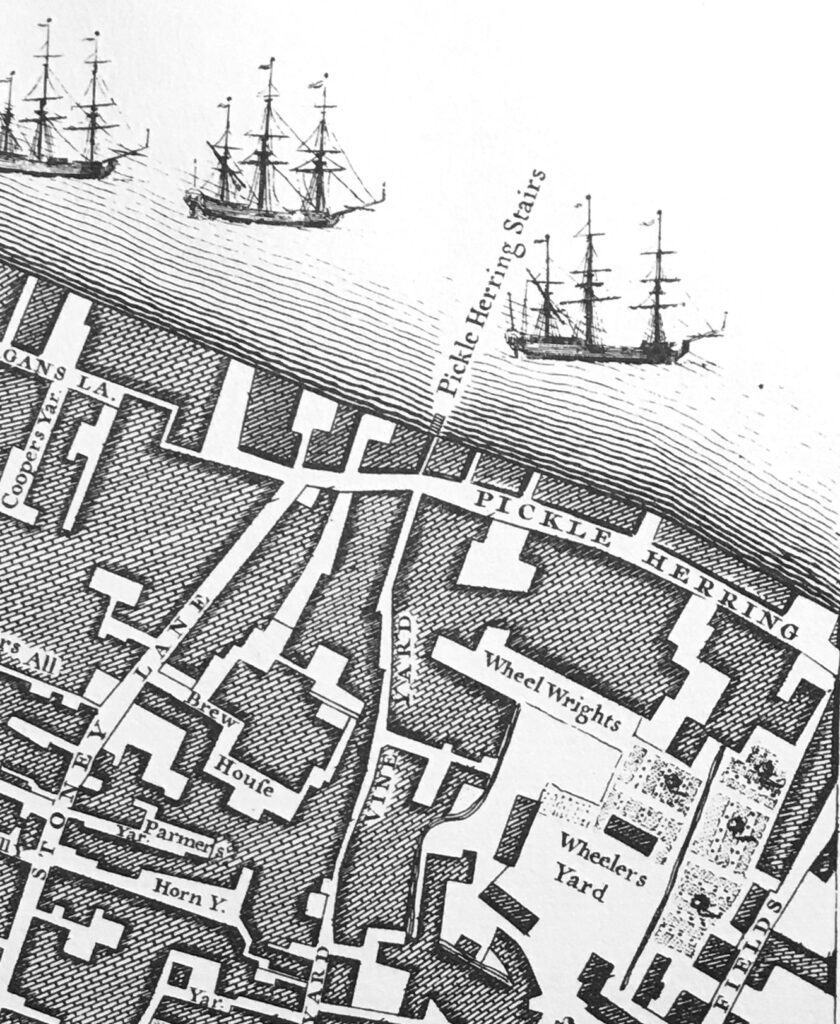

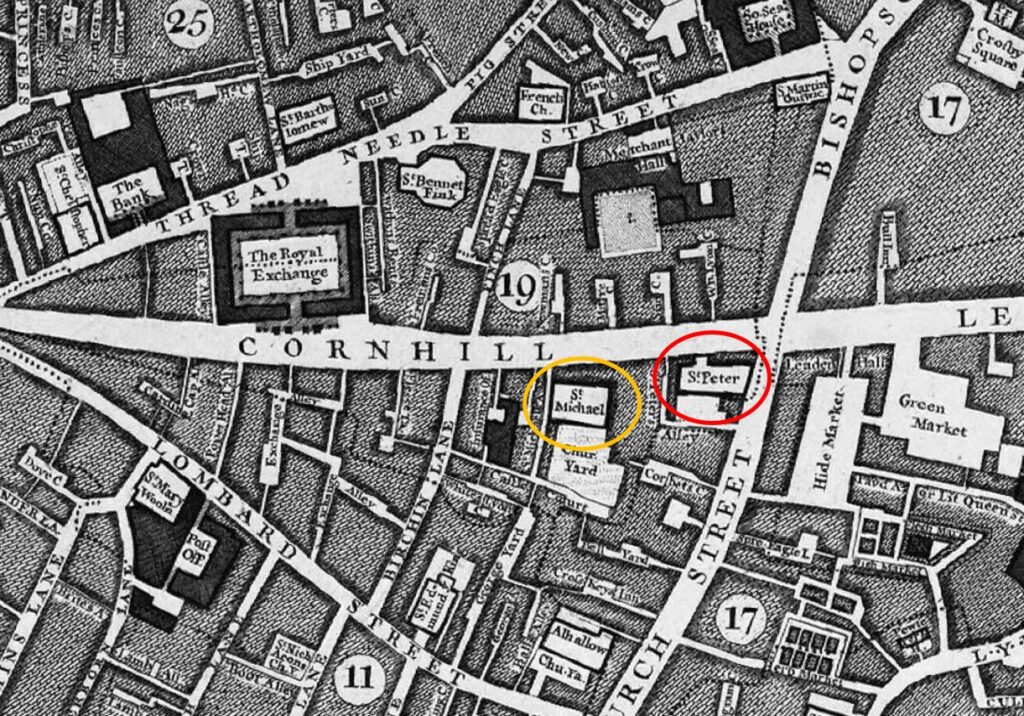

In the following extract from John Rocque’s 1746 map of London I have circled St Peter-upon-Cornhill (red) and St Michael Cornhill (orange):

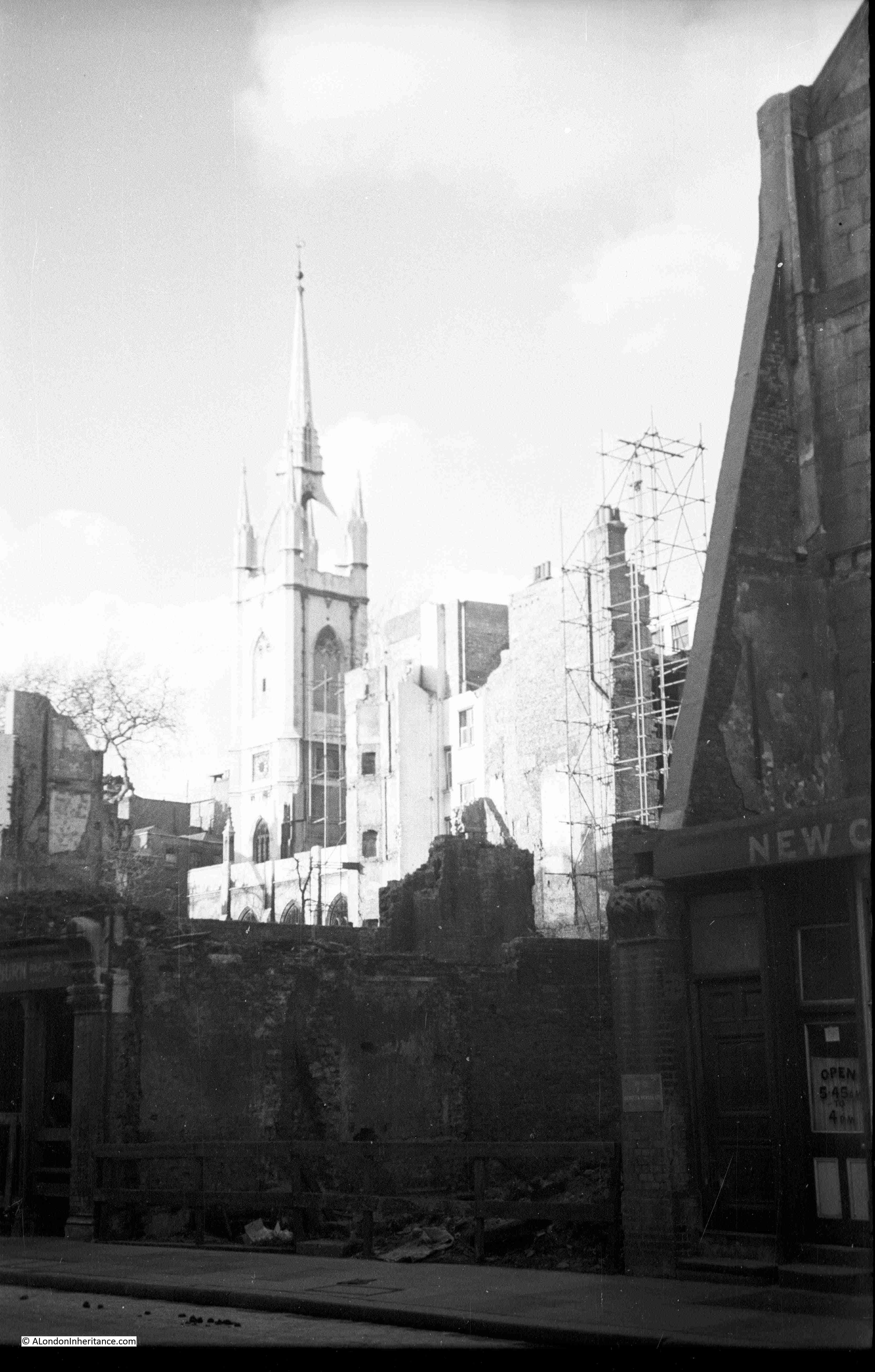

Both churches are partly hidden behind other buildings that face onto Cornhill, and have the appearance of churches from an earlier period of London’s history, when the built space was very crowded, and every available plot of land was utilised for building.

This is the view of St Peter, from Cornhill, with a lunchtime queue at the food shop that is on the small wedge of land between the body of the church and the street:

Only the main entrance to St Peter is on Cornhill, and when the doors are open, the entrance appears to offer a rather mysterious portal between the food shops to an older London:

St Peter-upon-Cornhill is in an interesting location, as it is at roughly the highest point in the City of London. Whether this has anything to do with the church’s location is doubtful, however it has been a religious site for very many centuries with Stow claiming the second century as the date for the founding of a church on the site.

The website of the church is even more specific as it states ” 179AD when Lucius, the first Christian King of Britain”, and that St Peter was the first church in the City of London. It was built on the site of the Roman Basilica.

Stow refers to a tablet in the church which had an inscription about the original founding of the church, and this reference also appears in other accounts of the church, however it seems this tablet dated to the 14th century, so a considerable gap of many centuries with the alleged second century date of the original founding of the church.

The earliest written records for the church date to 1127, however a church was probably on the site for many centuries before the 12th century, but whether back to the 2nd century is impossible to confirm.

The church has had a number of rebuilds and additions over the years. In the 15th century there was a school attached to the church.

In common with many other City churches, it was very badly damaged during the 1666 Great Fire. It was rebuilt by Wren between 1677 and 1684, and this is the church we see today as it survived the blitz without any damage – although there have been a number of restorations since the 17th century.

It was the post fire rebuild that shortened the church. Ten feet of the eastern section of the pre-fire church was demolished to make way for a widened Gracechurch Street.

I found one reference to the church of a type that I have not seen before. It goes back to the 25th of January 1783 and is a newspaper report about a fire in Fenchurch Street, and states that:

“There was a great scarcity of water for some time, but the reservoir belonging to St Peter’s Cornhill, being opened, a good supply was obtained, which was the means of its being got under.”

I have not seen a reference to a City church having a water reservoir. Whether this was an open body of water, or a large tank or conduit, it is impossible to tell. It could perhaps have been a service that the church provided to the parish.

Walking through the dark portal of the church from Cornhill reveals a surprisingly light church interior:

The last major restoration of the church was in 1872, and although everything above ground is Wren and later, below ground there are much earlier remains as during an excavation in 1990 it was found that Wren had used the medieval pier foundations of an earlier version of the church which probably dated to around the mid 15th century.

The most recent additions to the church are some stained glass. These were created by the stained glass artist, Hugh Ray Easton, and date from 1960.

The military significance of the windows is that the church was Regimental Church of the Royal Tank Regiment, between 1954 and 2007.

They are a strange mix of war and religious imagery, with in the following window, a group of soldiers are standing on a tank and are witnessing either the Ascension or the Resurrection:

As can frequently be found in City churches, there are a number of historical relics, including the following dating from 1710 which was probably carried in a procession by representatives of Cornhill and Lime Street Wards:

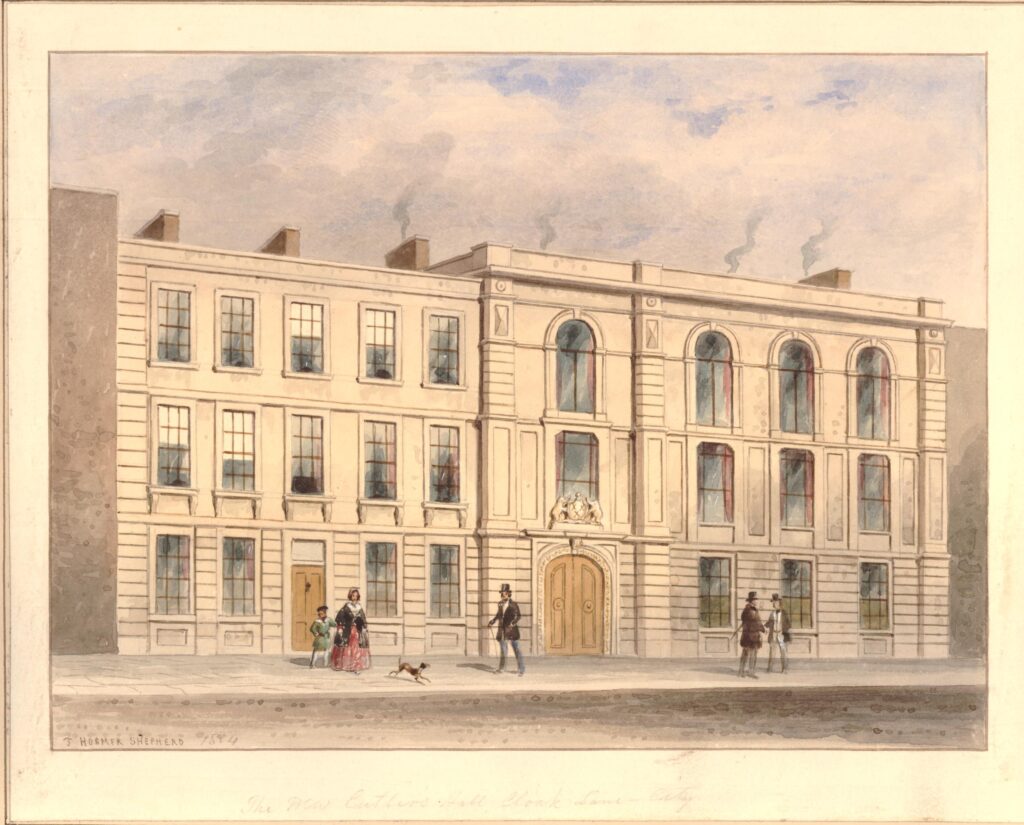

What also adds to the view of an earlier London is the building to the right of the entrance to the church. This is numbers 54 – 55 Cornhill:

The building has a food outlet on the ground floor, but look at the terracotta upper floors, and there are details that you would not expect to find on a commercial building in the City:

Some very grotesque creatures peer down at those walking along Cornhill.

This strange building was designed by Ernest Augustus Runtz, and dates from 1893. Apparently (although I can find no contemporary confirmation), Runtz’s original plans for the building strayed onto land owned by St Peter. The vicar objected, Runtz had to rework his plans, and added the figures as an insult to the vicar.

The Vicar may have had the last laugh though as Runtz was declared bankrupt in 1912 following financial problems and the failure of his business.

He has though left a most unusual building on Cornhill.

The second church, St Michael Cornhill, is a very brief walk from St Peter, and demonstrates how densely populated the City once was with churches, and again shows how buildings once surrounded City churches, as with St Michael, only the tower is visible from Cornhill, with the main entrance to the church being through an ornate entrance in the base of the tower:

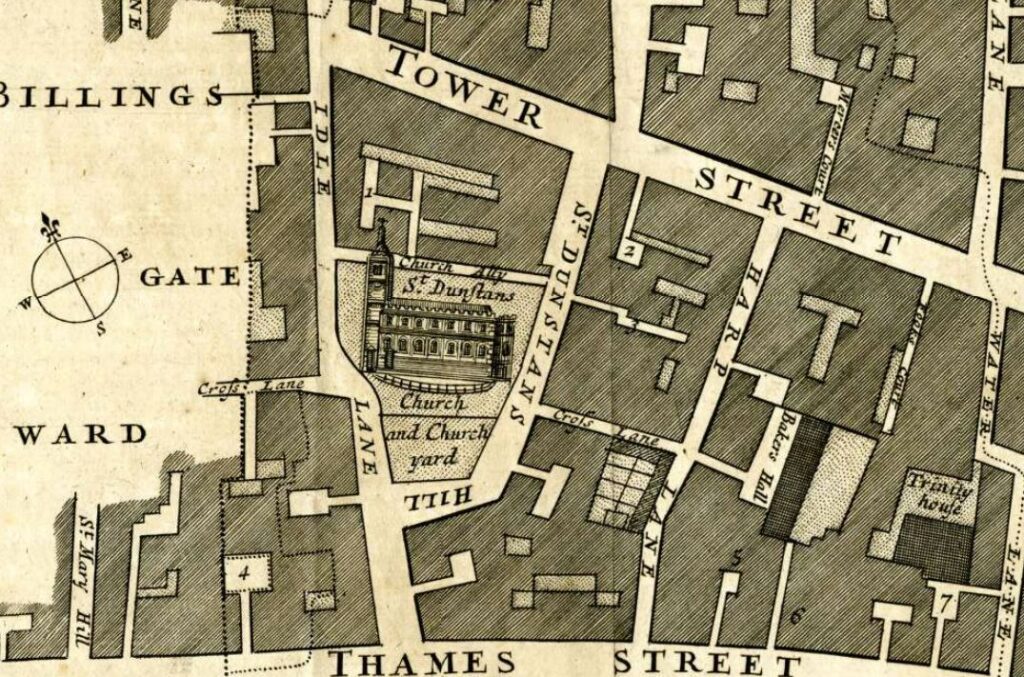

St Michael is again an old church, however there are no firm records of just how old. The usual references where “tradition points to a church in Saxon times”, however the first written reference, according to “London Churches Before The Great Fire” by Wilberforce Jenkinson (1917) is from 1133 when the church was in the possession of the Abbott of Evesham, and the “living granted by him to Sparling the Priest”.

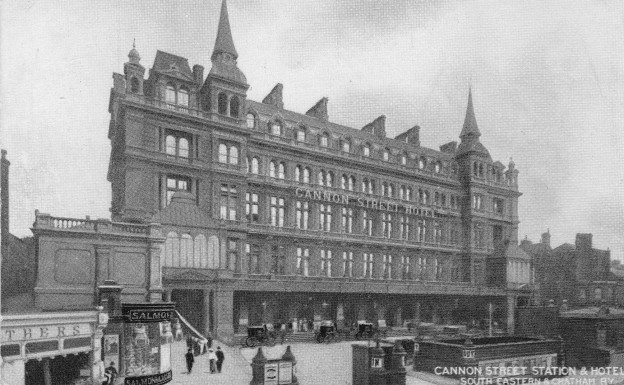

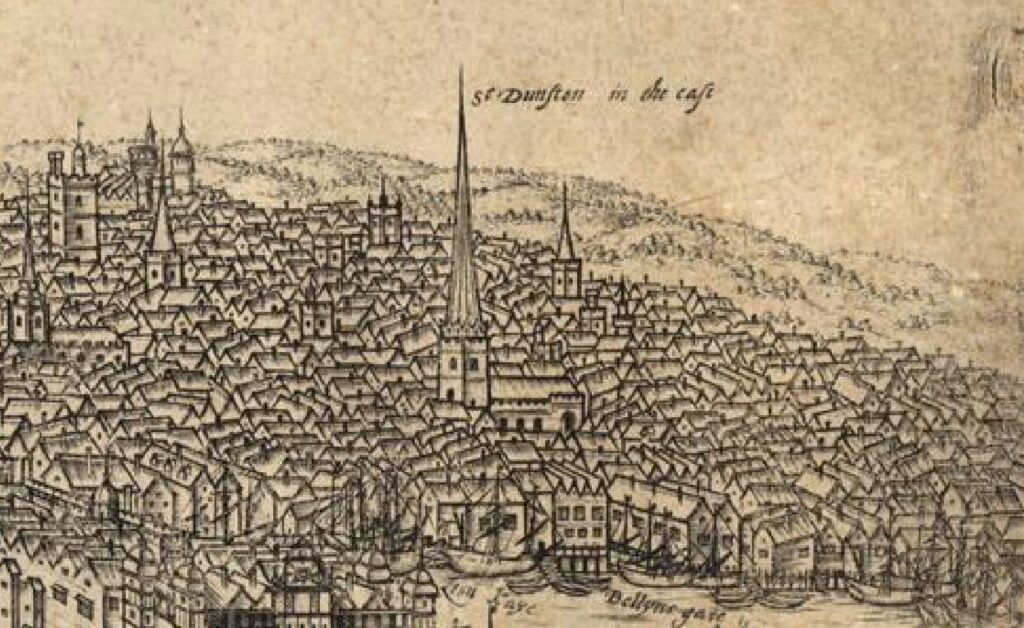

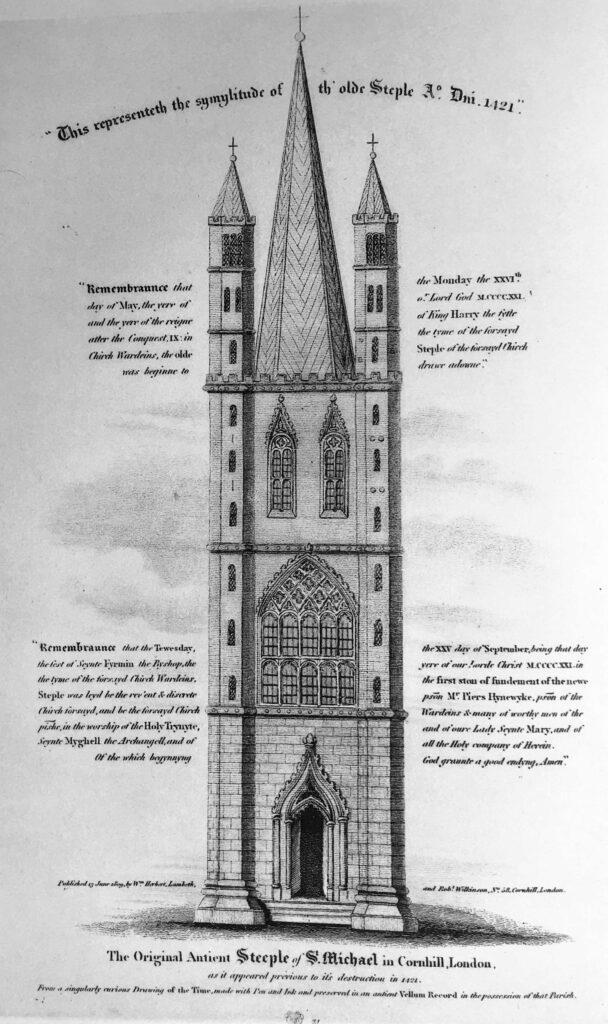

The tower of the church seems to feature in the majority of references to, and illustrations of St Michael.

There are no illustrations of the original church, however a copy of an illustration of the fourteenth century tower, which was destroyed in 1421, has survived and shows the “Symilitude of the old Steeple 1421”:

The church was badly damaged during the 1666 Great Fire, but was rebuilt between 1670 and 1671 by Wren, who included the surviving tower into the reconstruction. The tower was weakened by the fire and survived for a further fifty years and was then taken down “as wanting in stability”.

Pevesner states that the new tower was probably designed by “William Dickenson who was in charge of winding down Wren’s City Church Office”, although other references state that it was to Wren’s original design.

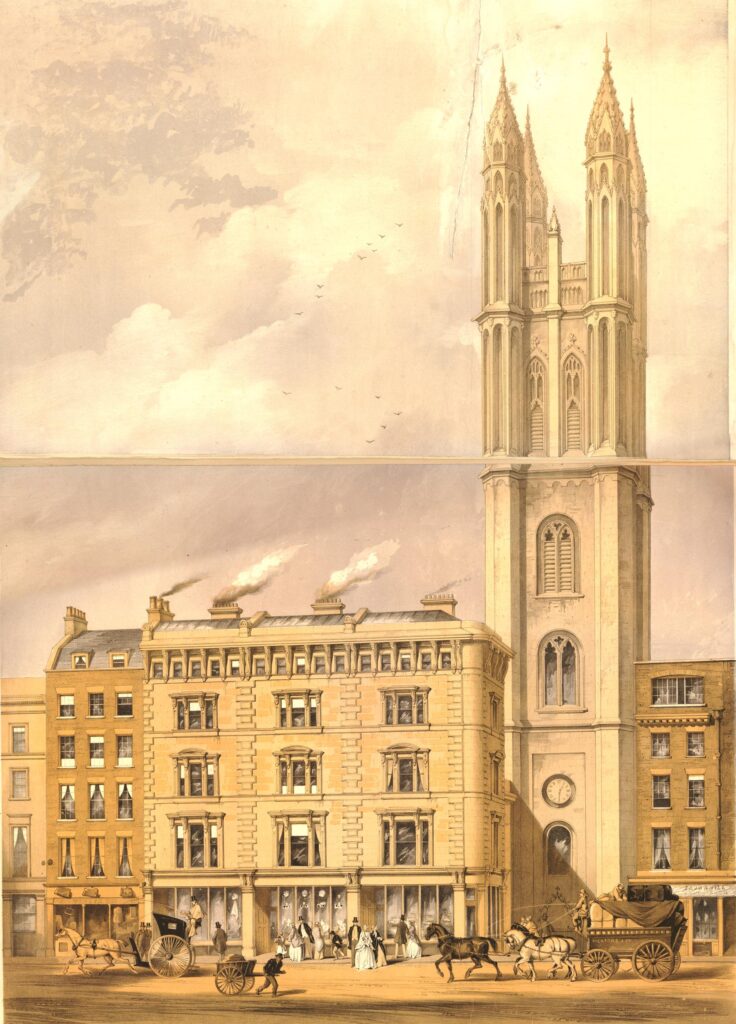

The following print illustrates the appearance of the tower in 1850, again with only the tower being visible from Cornhill. The body of the church is behind the buildings on the left (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The tower in the above print is the same tower that we see today, however it was missing one vital feature, the ornate entrance to the church at the base of the tower.

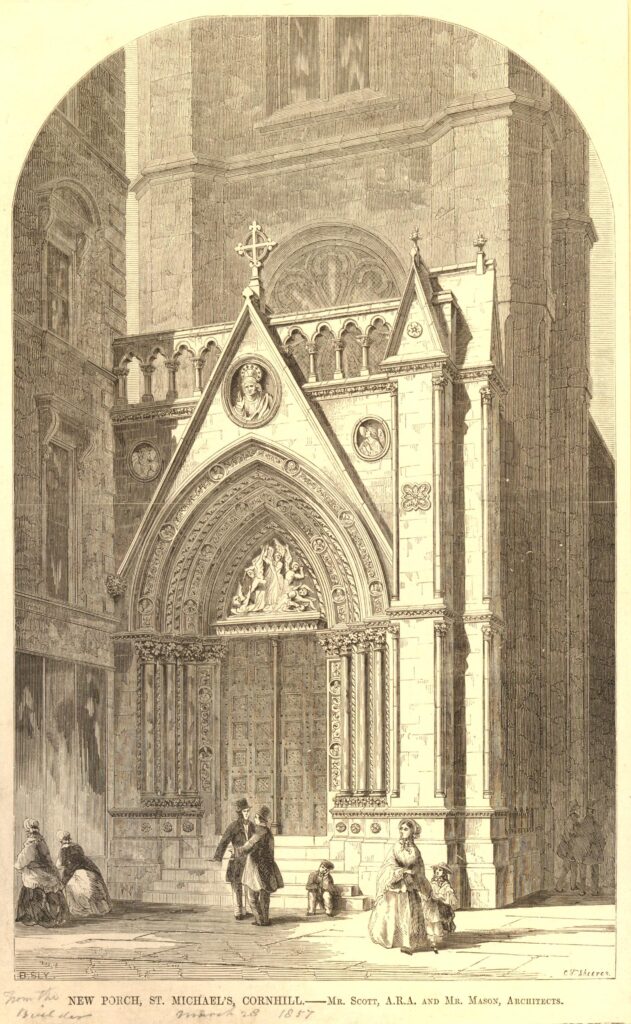

This ornate, Gothic entrance would be built between 1857 and 1860 when the church was the first in the City to be remodeled to high Victorian taste by Sir George Gilbert Scott.

The following print has a penciled note dating it to 1857. It may actually be a couple of years later, however it does show the new porch soon after it had been added to the church, and although today the stone is blackened with dirt (another feature of older City churches), it does look much the same today (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The interior of the church is mainly from the 17th century, post Great Fire rebuild with mid 19th century and later restorations:

Pevsner states that the organ has been “much rebuilt”, so it is probably not that old, although there may be some surviving parts from the original Renatus Harris 17th century organ. It still looks very impressive with gleaming, gold, organ pipes occupying a corner of the church:

Looking back towards the base of the tower:

The majority of City churches have plenty of old monuments, pulpits, sword rests etc. and St Michael Cornhill is no exception. In St Peter I wanted to highlight the stained glass windows as a different feature, and in St Michael there are coats of arms on the sides of the pews. The majority appear to be City Livery Companies, however there are some I cannot identify. The following photos show a sample.

The Merchant Taylors:

The Drapers:

This one is rather strange. I cannot find a similar set of arms being used by a Company. The crossed swords may indicate the Cutlers who usually have three sets of crossed swords on their arms, however I cannot confirm that they use the images on the right of the shield:

The Clothworkers:

Another I cannot identify, or find anything similiar:

I thought I had a reasonably good understanding of the arms used by City companies, and have also been through the book “The Armorial Bearings of the Guilds of London”, but the following is a mystery as well:

The Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom – apparently this were placed on the pew at the front of the church in anticipation of a visit by Queen Victoria. Unfortunately she failed to visited the church.

The arms of the City of London:

When researching many of my posts, I am struck by the number of times there is a reference to a serious fire at or near the subject of the post. It is incredible just how many fires there were in 18th and 19th century London. Even after the building regulations put in place after the 1666 Great Fire, serious fires still continued.

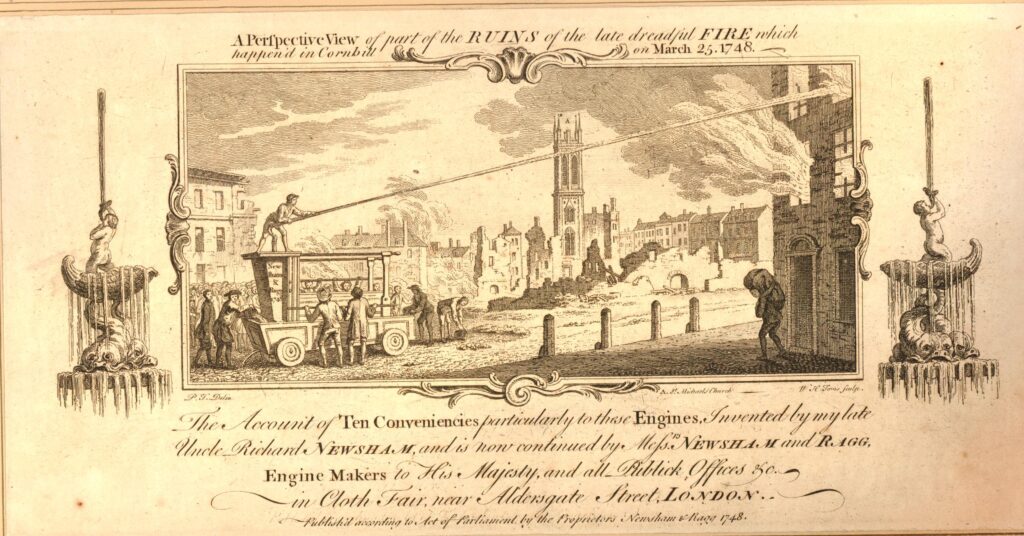

When searching for stories about St Michael, I found the following print which shows a serious fire in Cornhill on the 25th March, 1748, with the tower of St Michael in the background (© The Trustees of the British Museum):

The print is fascinating for the detail it portrays. There is presumably a property owner on the right, apparently rescuing something from the burning building.

There is a very early fire fighting pump on the left, sending a jet of water at the building.

The print references the engine as “invented by my late Uncle, Richard Newsham”, an inventor who held two patents for fire engines, taken out in 1721 and 1725. Newsham appears to have dominated the mid 18th century market for fire fighting equipment.

The following photo shows the earliest known fire engine by Newsham purchased in 1728, and photographed at St Giles Church in Great Wishford, Wiltshire. The photo is almost identical to the one in the 1748 print:

Source: Trish Steel, CC BY-SA 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A quick visit to two Cornhill churches. They are an interesting pair of churches to visit as they demonstrate what City churches must have looked like in previous centuries. Surrounded by buildings on the main street, a small churchyard behind, but only an entrance to the street.

That they are also a very short distance apart is a reminder of how densely populated the City was with churches, before the loss of churches caused by the Great Fire, 19th century church closures, and bombed churches not being rebuilt after the last war.

You can read another of my posts about Cornhill, the Cornhill Water Pump, here.