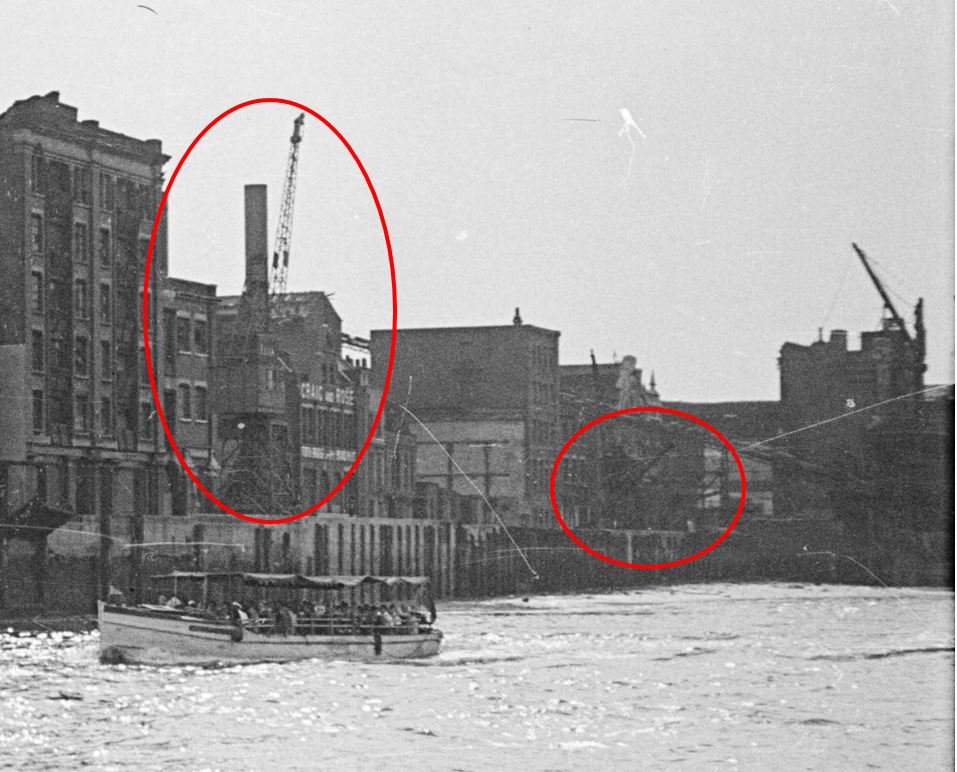

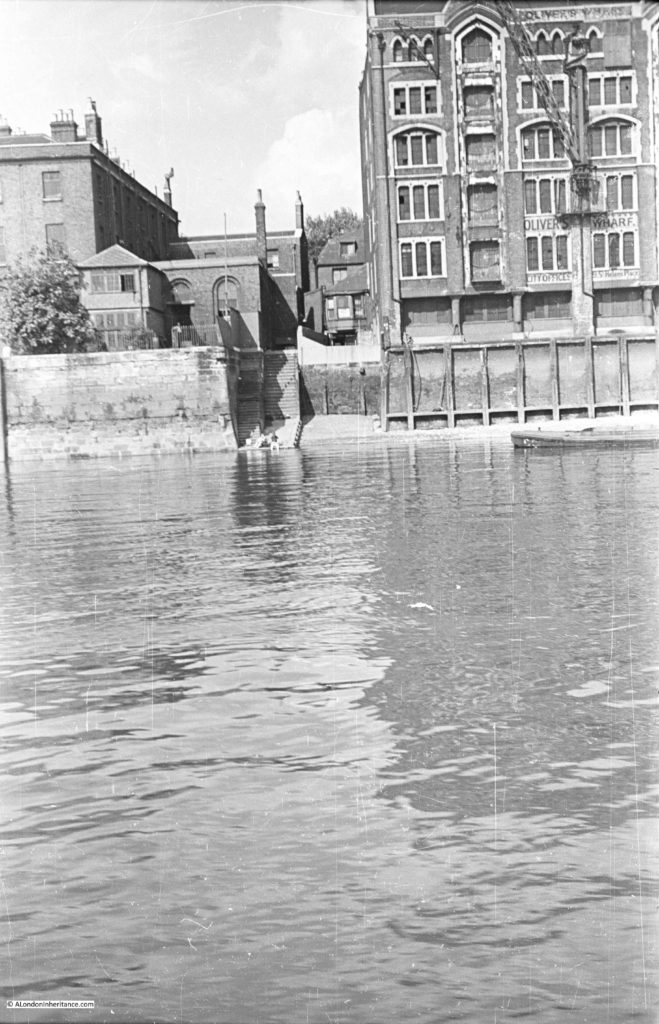

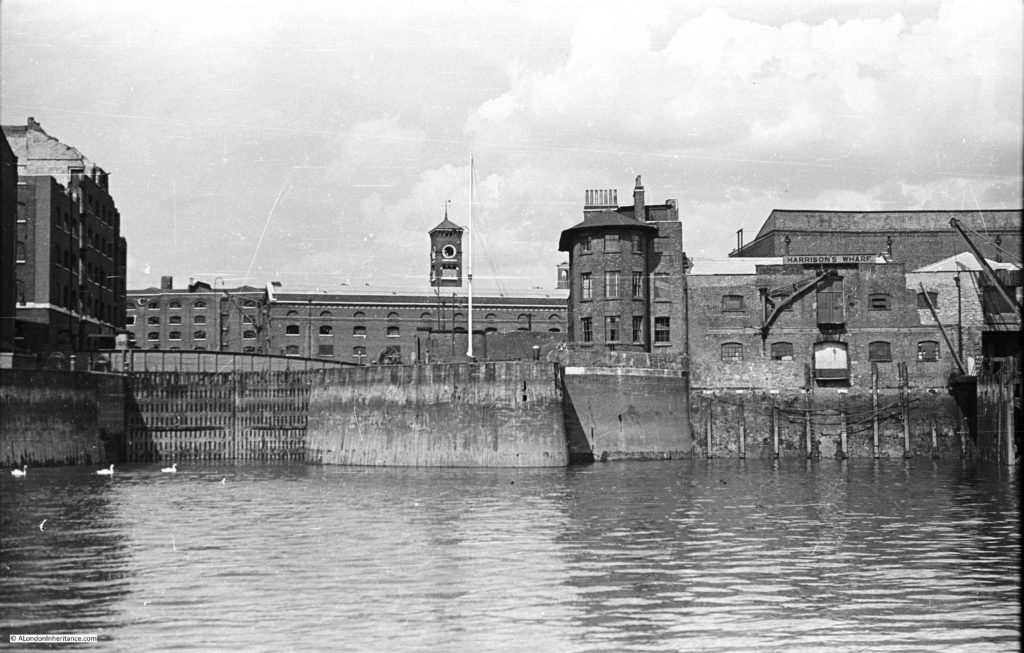

In August 1948, my father was on a boat sailing from Westminster to Greenwich, taking photos along the route. The following photo is after having just passed under London Bridge, looking down towards Tower Bridge, with the cranes and warehouses of the wharves that line the river opposite the City of London.

The Southwark side of the river between London Bridge and Tower Bridge was very different to the City side of the river. The Southwark side was full of wharves, warehouses, cranes and moored ships and barges.

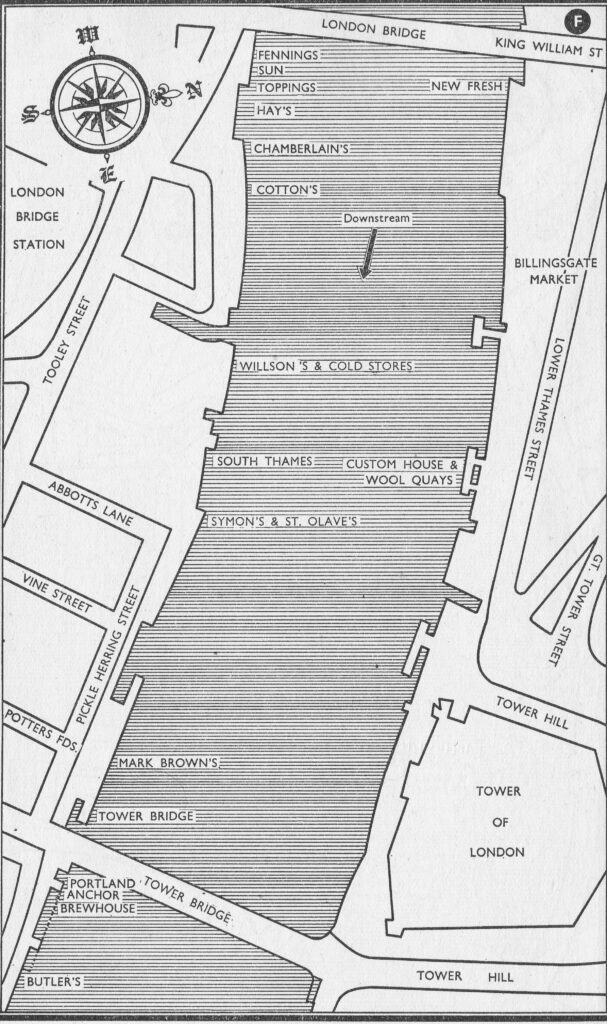

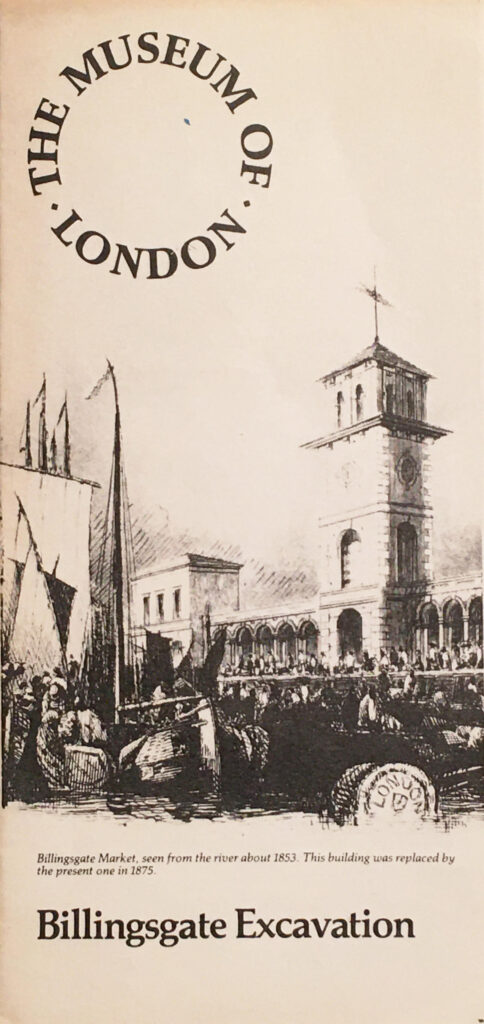

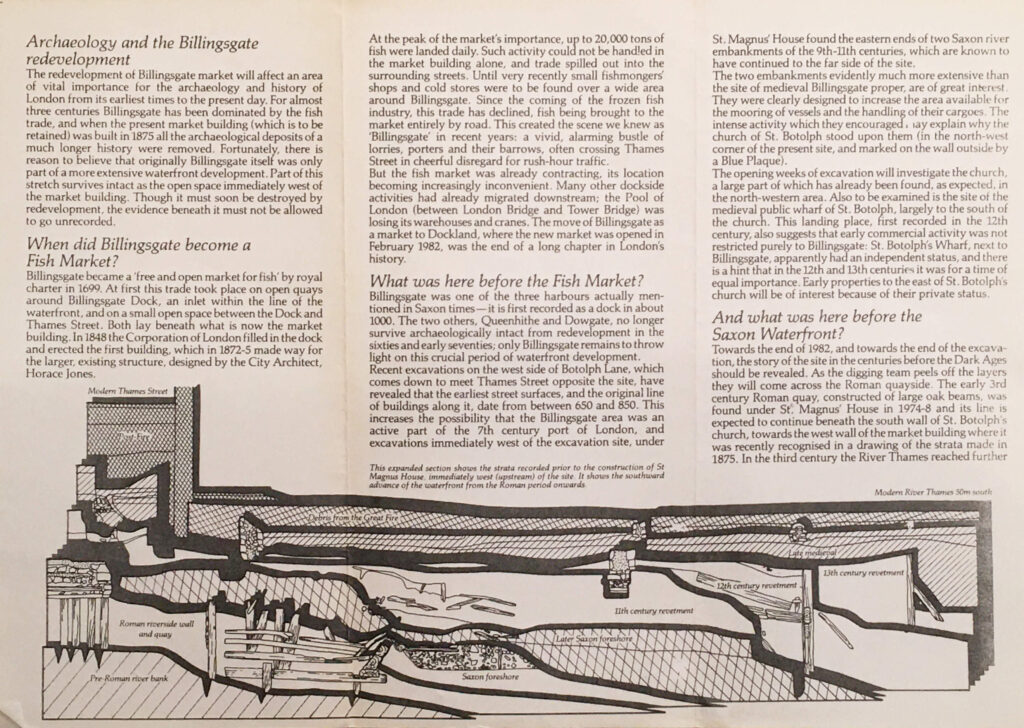

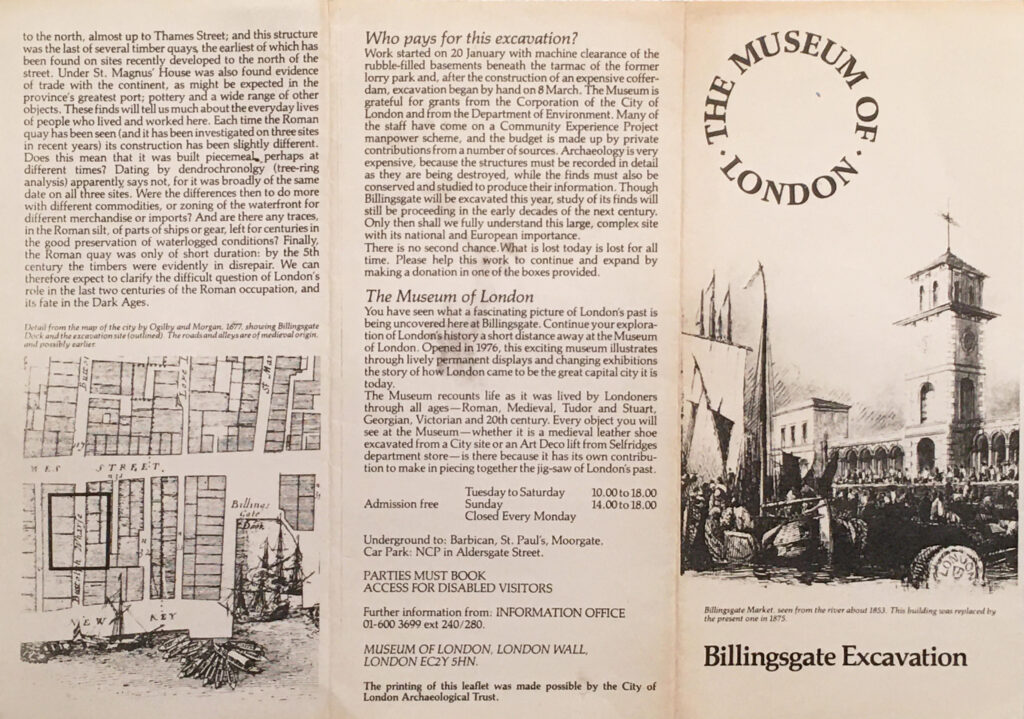

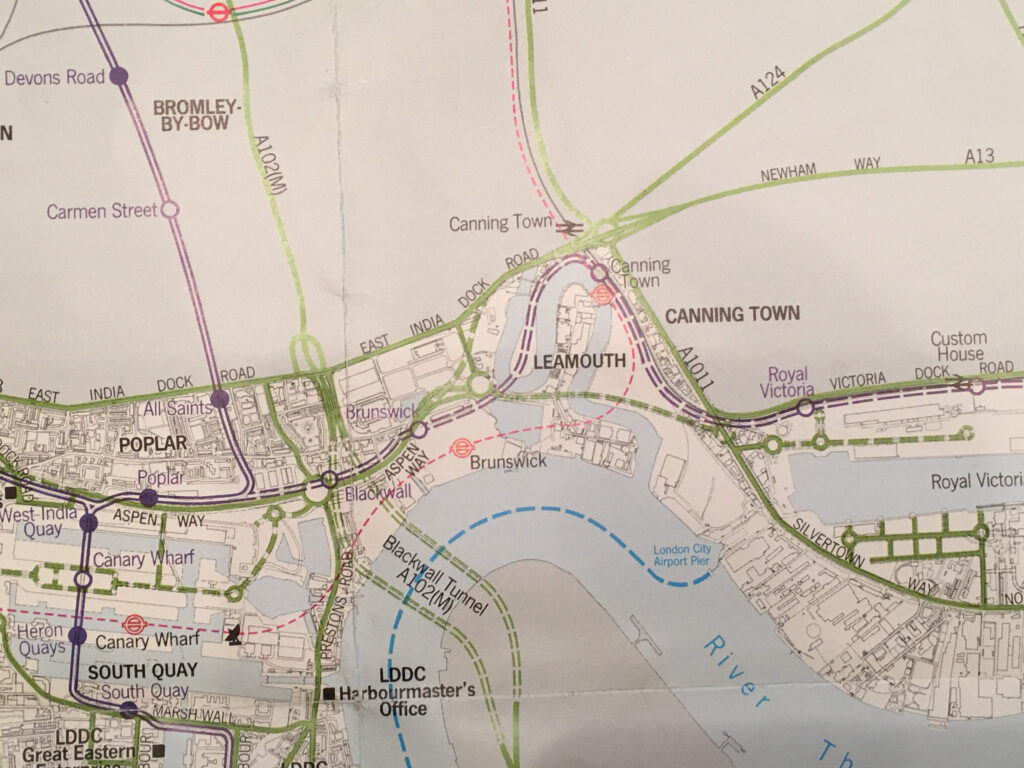

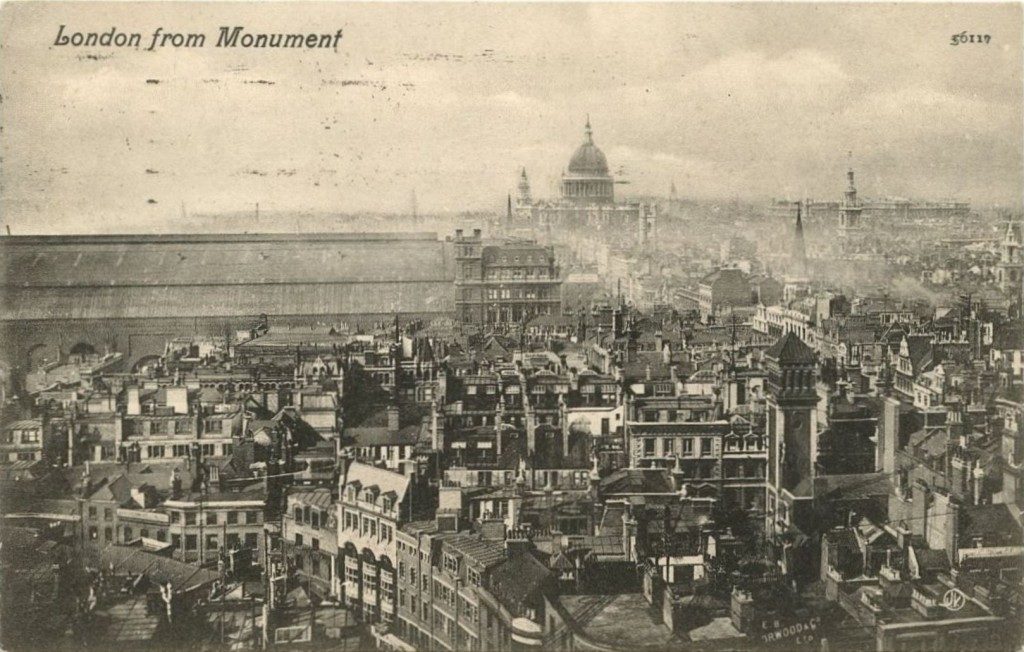

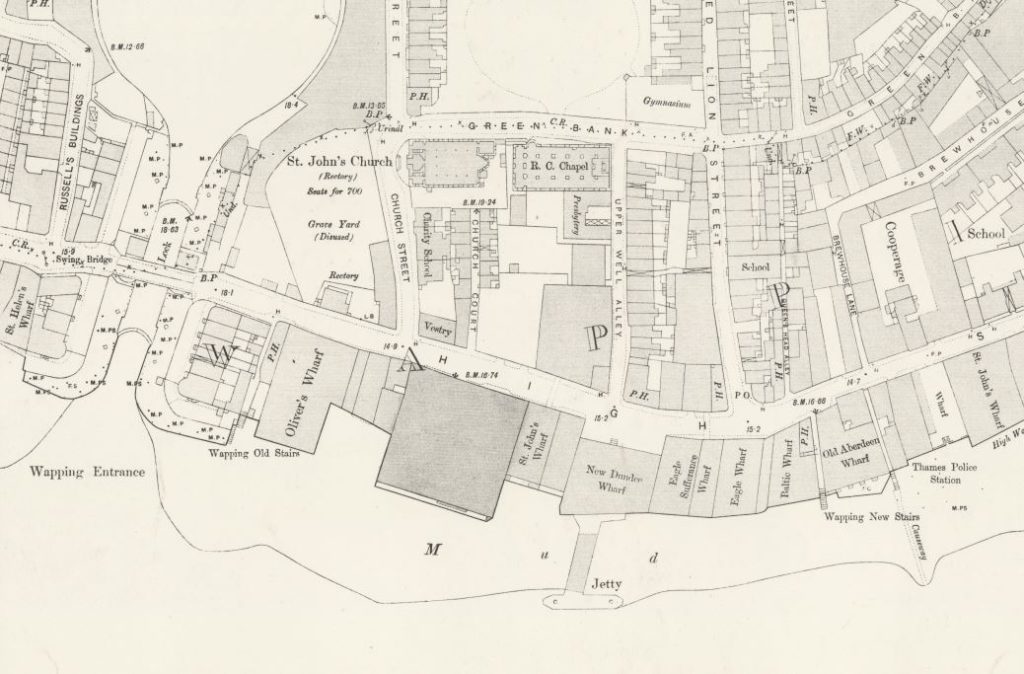

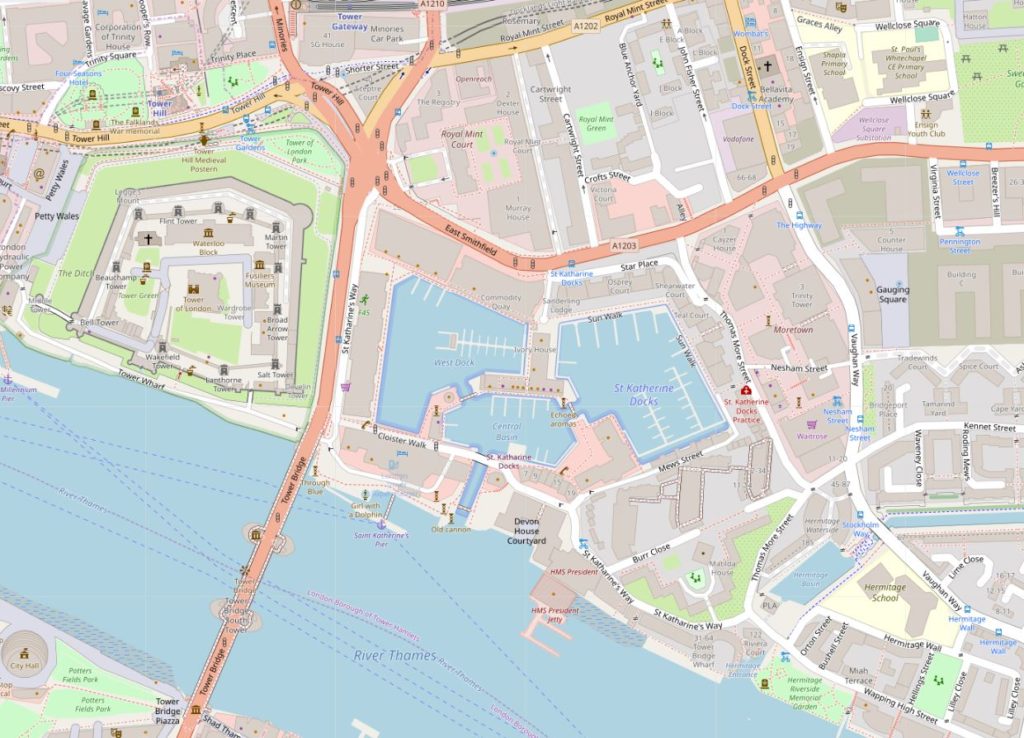

The City had Billingsgate Market, the Customs House, New Fresh Wharf and the Tower of London. The difference between the two sides of the river can be seen in the following map from Commercial Motor’s 1953 edition of London Wharves and Docks:

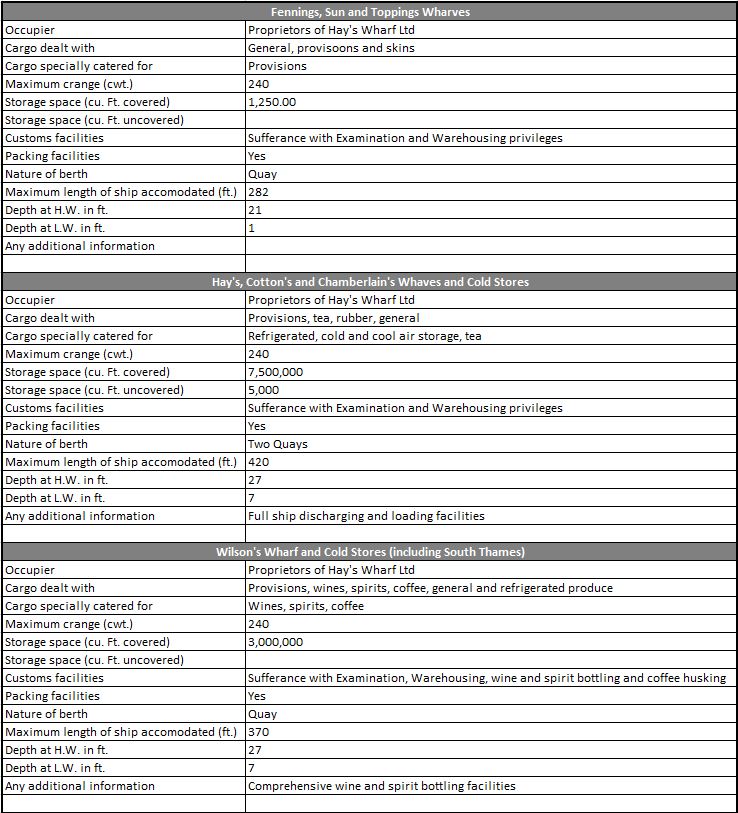

This fascinating book lists all the wharves and docks between Teddington and Tilbury, and provides details of the trade that they handled and their facilities. The following tables cover the Southwark wharves between London and Tower Bridges:

There was a remarkable 20,250,000 cubic feet of storage space within the warehouses along this relatively short stretch of the river, and there was a wide range of goods being stored. Chances are that if in 1953 you were drinking your morning cup of coffee, it would have been imported through one of these wharves.

By 1953, all except the Tower Bridge Wharf were owned by Hay’s Wharf Ltd, a business that had been expanding rapidly, and a name that can still be found in this transformed stretch of the river.

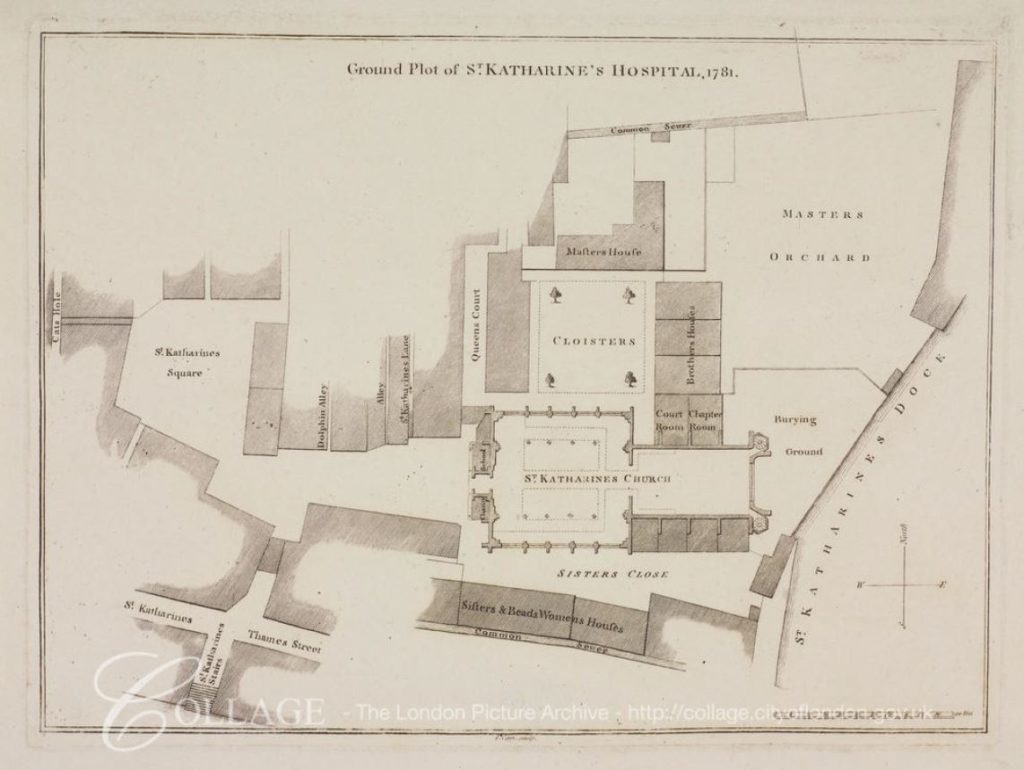

Many of these wharves had been in existence for hundreds of years, and they would have had individual owners with the name often reflecting the original owner / builder of the wharf.

There is so much history associated with each wharf, and they can demonstrate how trade was conducted, and what life was like in this part of London. Close to London Bridge in the above map is Topping’s Wharf, and I have taken this single wharf to see what can be found of its history.

The first reference I could find of Topping’s Wharf was an advert in the Newcastle Courant on the 17th December 1774 where the new owners are setting up a cargo route between London and Newcastle and advertising Topping’s Wharf as a safe and insured site for goods to be stored:

“To the MERCHANTS, TRADERS and SHIPPERS of GOODS to and from London and Newcastle. We take this opportunity of acquainting you, that having lately taken a new, commodious, and convenient Wharf, situate in Tooley-street, Southwark, and adjoining to London bridge, known by the name of Topping’s Wharf, where there are exceeding good warehouses for lodging and securing goods from damage by weather, and where vessels of 300 tons burthen or upwards may load by cranes, which will be a considerable saving of expense and risk, incurred by the present method of shipping, by lighters from above bridge. The goods will be lodged in warehouses, upon which an insurance of £4000 from fire will be made till shipped and the policy deposited at the Bank of Newcastle. A set of good accustomed vessels are engaged, one of which will sail every week. We therefore solicit your favours, and assure you, that the greatest care will be taken to ship your goods with regularity and dispatch, by Your humble servants, CHINERY, RUDD and JOHNSON, London, December 9th 1774”.

These newspaper adverts and reports are interesting because they shed some light on how trade was conducted in the 18th century. They also mention fire insurance as a key feature of Topping’s Wharf, and from later events we can see why.

Warehouses held large volumes of highly flammable materials, and fires in London’s warehouses were very frequent, with often significant destruction of buildings, the goods stored in the warehouse and ships moored alongside.

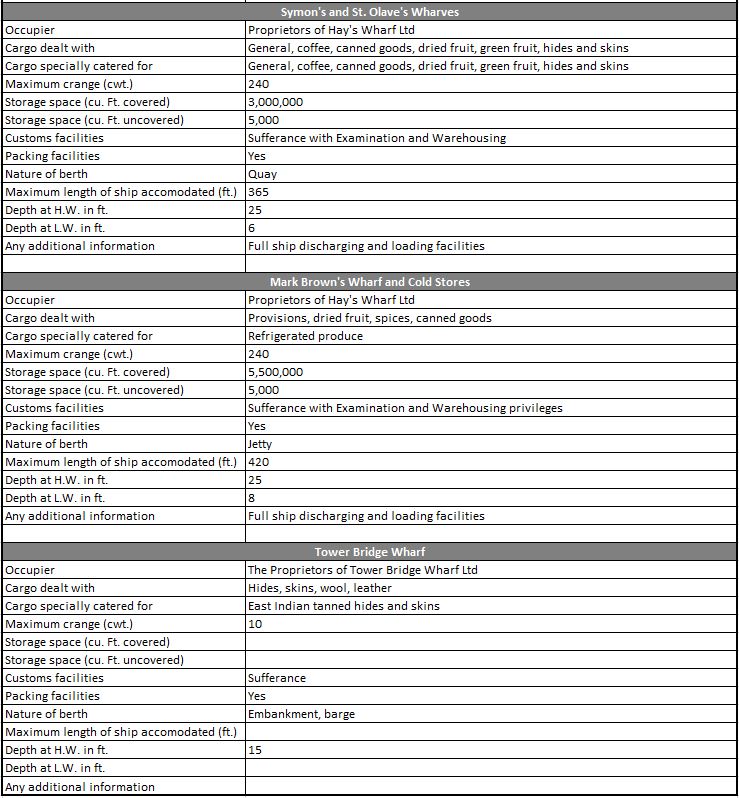

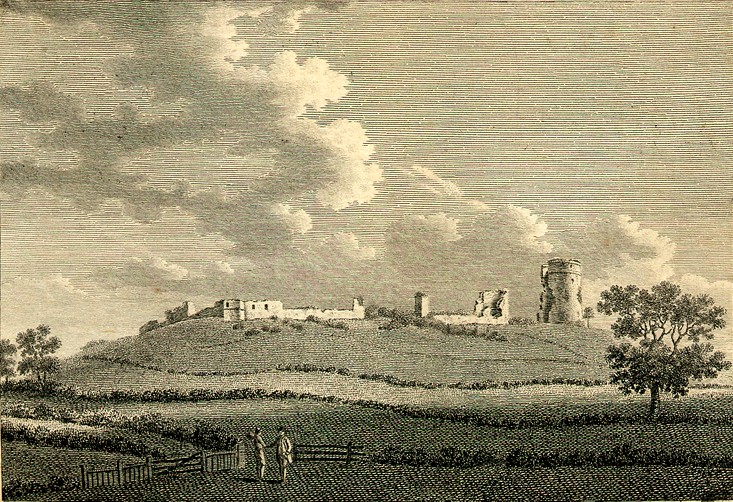

I have already written about one fire in the area, called at the time the “Great Fire at London Bridge” in 1861. There had already been another major fire eighteen years earlier in 1843. This fire had destroyed Topping’s Wharf, as reported in the Globe on Saturday, August 19th, 1843:

“TERRIFIC FIRE THIS MORNING – Never since the too well remembered fire at the Royal Exchange in 1838, has it fallen to our lot to record a more terrific one than that which took place this morning at an early hour, at the premises known as Topping’s Wharf, situate on the east side of London bridge, near Fenning’s Wharf, which it will be recollected was destroyed by a similar calamity in 1836.

In magnitude it exceeded the above-named disaster, or any other that has occurred on the banks of the River Thames for many years past; for, in addition, we regret to say that Watson’s Telegraph, formerly a shot tower, the large turpentine and oil stores of Messrs. Ward and Co, in Tooley-street, and St Olave’s Church, all fell a sacrifice to the devouring element, besides doing extensive damage to a tier of shipping moored alongside Topping’s Wharf”.

The fire had started just before two in the morning and was spotted by a Police Constable. The Fire Brigade was soon on the scene, led by the superintendent of the brigade, Mr. James Braidwood (who would be killed in the fire in Tooley Street eighteen years later).

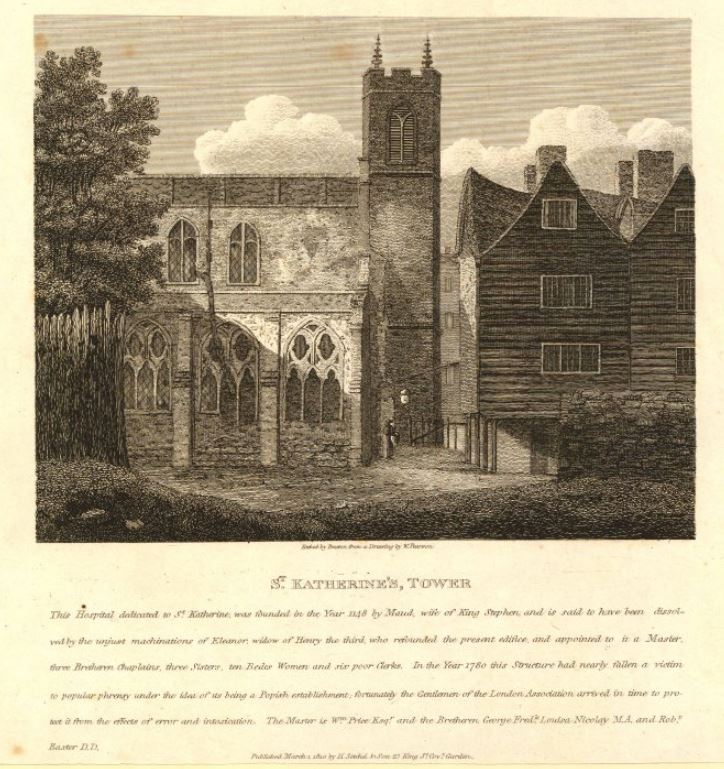

By four in the morning, St Olave’s Church, just behind Topping’s Wharf was on fire and the Globe reported that “there appeared very little chance of any of that ancient building being saved”.

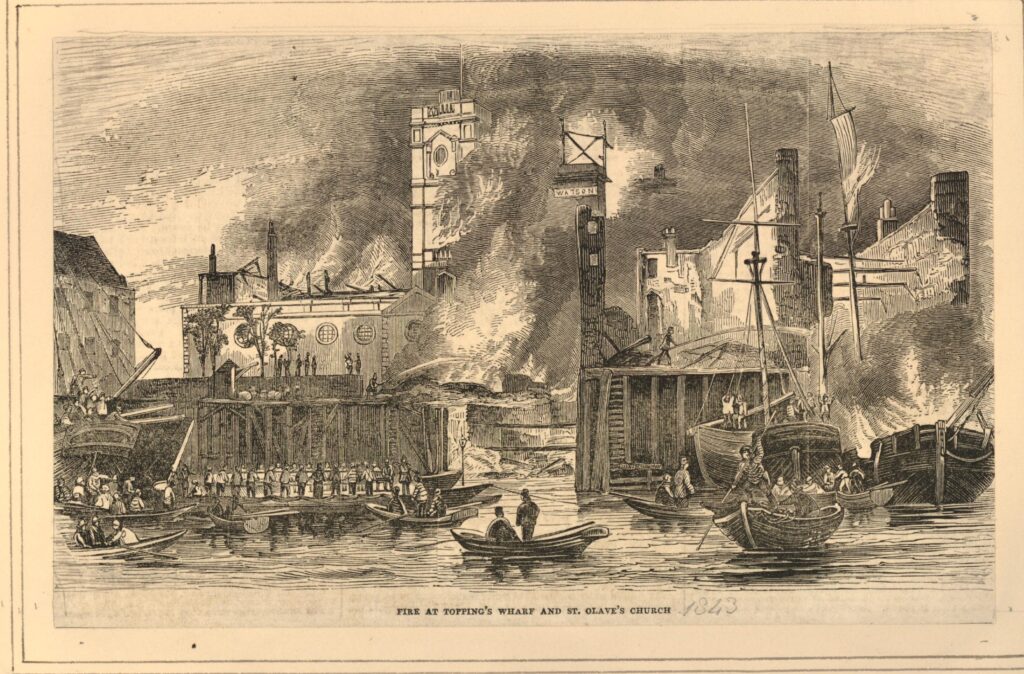

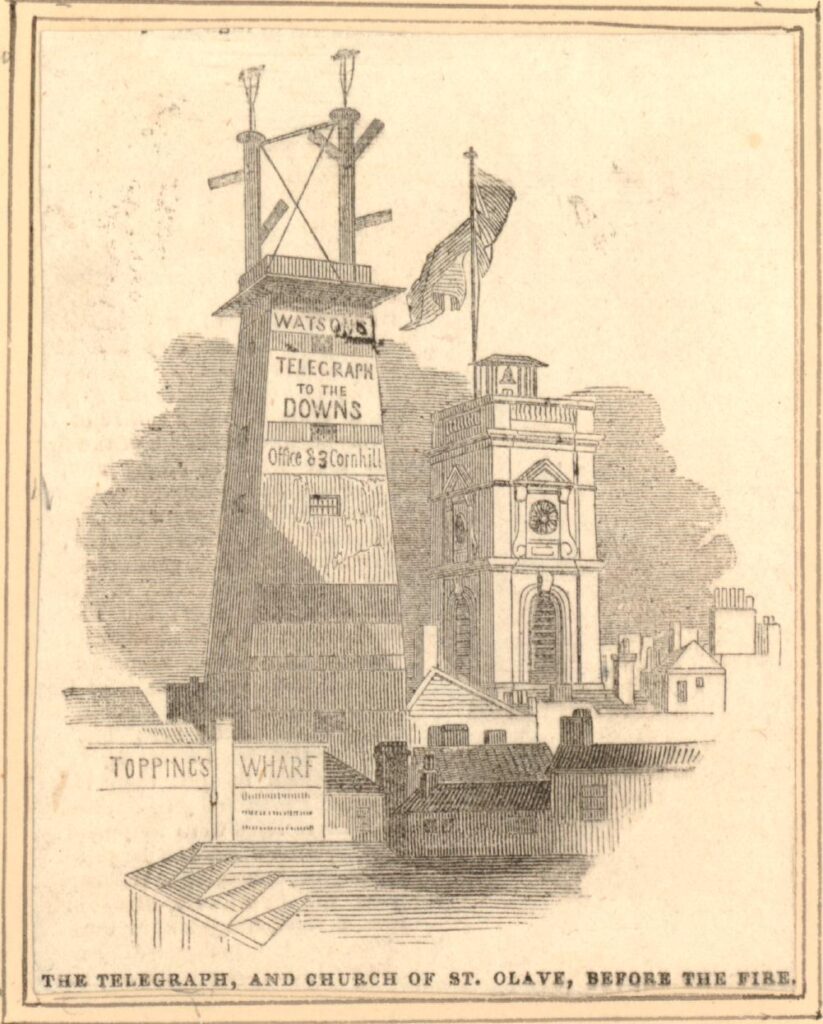

The following print shows the 1843 fire at Topping’s Wharf (©Trustees of the British Museum):

The report in the Globe newspaper mentioned Watson’s Telegraph, and in the above print, just to the right of the church tower you can see the word Watson. I knew about Watson’s Telegraph, but did not know that the central London telegraph was based by St Olave’s Church and Topping’s Wharf, just to the east of the southern end of London Bridge.

The British Museum has a print of Watson’s Telegraph before the fire, with St Olave’s Church to the right, and Topping’s Wharf to the lower left (©Trustees of the British Museum).

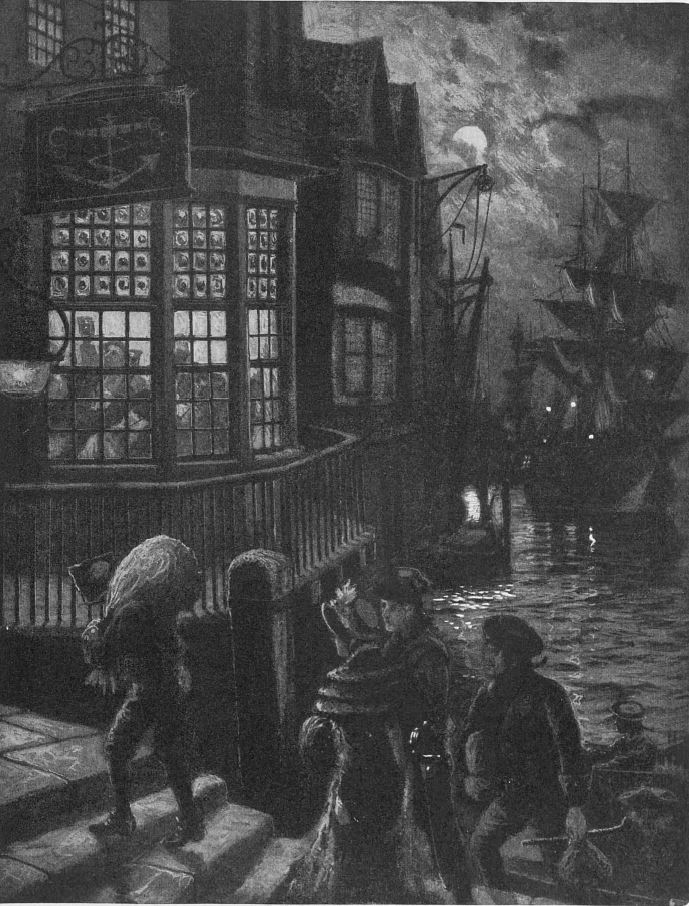

Watson’s Telegraph was the creation of a Mr. Watson of Cornhill. The purpose of the system was to rapidly pass messages to and from the coast and key ports. It was important to traders and ship owners in the City to know when their ship and cargo were getting close, or events such as a tragedy at sea.

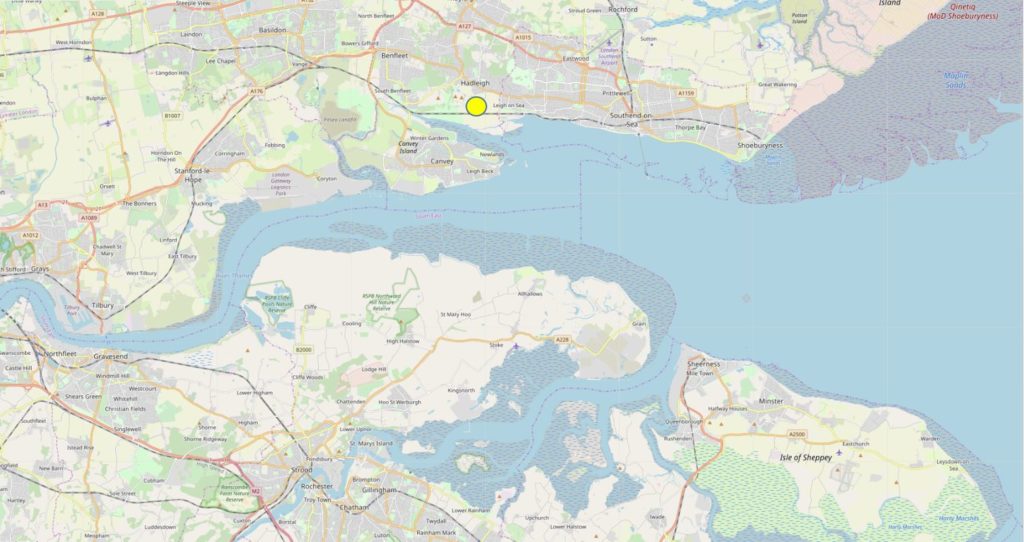

Watson’s Telegraph system comprised of a number of towers with a semaphore signaling system on top. These were located at strategic points to allow a message to be passed along a chain of stations to the required destination. Each telegraph station needed to be able to see the telegraph stations on either side in the chain. For example, to pass a message between the City and Deal in Kent, the telegraph chain consisted of: “London-bridge; the second at Forest-hill; the third at Knockholt; and others at Wrotham-hill, Bluebell-hill, and three or four elevated spots between there and Deal”.

An article in the Illustrated London News provided the above list of locations, and I love the introduction to the article which paints a futuristic view of communications:

“In this miraculous age of improvements and discoveries when ‘the annihilation of time and space’ is no longer regarded as an idle chimera of the brain, it might hardly be considered necessary to occupy our space with a detail of the various schemes that have been adopted and put in operation to facilitate this most paramount and prevailing desire. So many of our readers must be naturally unconversant with those experiments in arts and science which the ‘great metropolis’ is continually eliciting, that we feel it a duty which we owe to our friends and supporters at a distance, to place before them those objects of interest and real usefulness in which the metropolis abounds, and which are only known to them by name”.

As well as the telegraph stations, a key part of the system was a Telegraphic Dictionary which was kept at each station and contained “several thousand words, names, phrases and directions, such as are likely to be most useful and required, and names of vessels, places, and certain nautical terms which have been selected with great care, as may best suit the object in view”.

The message entries in the dictionary have an associated unique number and the positions of the arms on the semaphore corresponded to different numbers, thereby allowing the position of the arms to send a message from the telegraphic dictionary.

The system was created in 1842. It is remarkable to think that 179 years later, on the evening before writing this post, I was watching a live stream over the Internet from the US of the Perseverance rover landing on Mars, with photos of the surface coming minutes after landing. How communications technology has changed in less than 200 years. I suspect the readers of the Illustrated London News in 1842, could not have imagined this new ‘the annihilation of time and space’.

It is difficult to track the ownership of Topping’s Wharf over the centuries of its existence. It seems to have been owned by Magdalen College, Oxford for some time, as in the Globe on the 28th October 1907, there is a record that: “the leasehold of Topping’s Wharf, Tooley-street, London-bridge, which Messrs. Jones, Lang, and Co. are to offer by the instructions of Magdalen College, Oxford”. There was also a description of Topping’s Wharf:

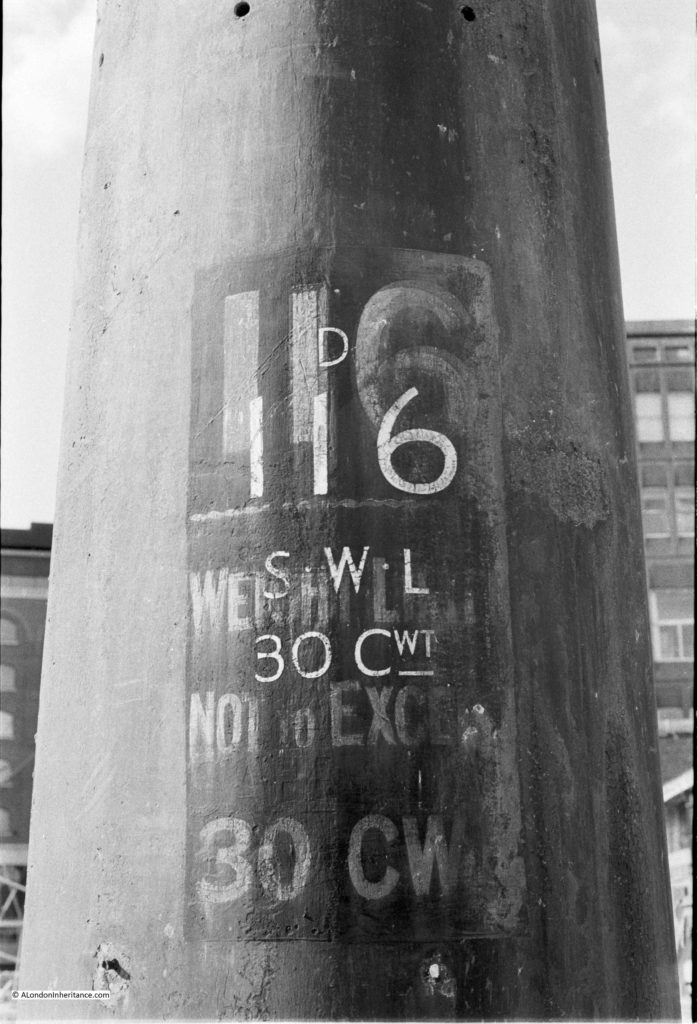

“The premises, which comprise ground floor, basement, and three large upper warehouse floors are supplied with loopholes to each floor, with hydraulic lifts, and cranes, back and front, and have recently been fitted with a London County Council staircase”.

I cannot find who took the lease in the 1907 auction, but in 1912 Topping’s Wharf was let to Nestle and the Anglo Swiss Condensed Milk Company. Hay’s Wharf Ltd seem to have taken on Topping’s Wharf in the 1920s.

Back to the view of the river between London and Tower Bridges, and another view of the wharves along the river, and the ships that used these wharves is shown in the following photo which my father took from the open space outside the Tower of London.

When my father took the above photo and the photo at the top of the post, the wharves along this part of the river were really busy. Cranes lined the river and ships loaded and unloaded their cargo at this stretch of wharves which were then nearly all owned by Hay’s Wharf Ltd.

The introduction to the 1953 edition of Commercial Motor’s London Wharves and Docks gives an impression of how trade on the river was increasing:

“Commercial activity on the River Thames has increased considerably in the post-war years, due in large part to British Industry’s successful efforts to expand its export trade with world markets. Arising out of this intensified traffic in the industrial reaches of the Thames has come the need for an up to date, comprehensive guide to the many wharves and docks which line the banks of the River from Teddington to Gravesend”.

Despite the post-war increase in trade on the river, the wharves between London and Tower Bridges would not have too many years left. The increasing size of cargo ships and containerisation meant that inner London docks quickly became unsuitable for the type of shipping and new methods of moving cargo.

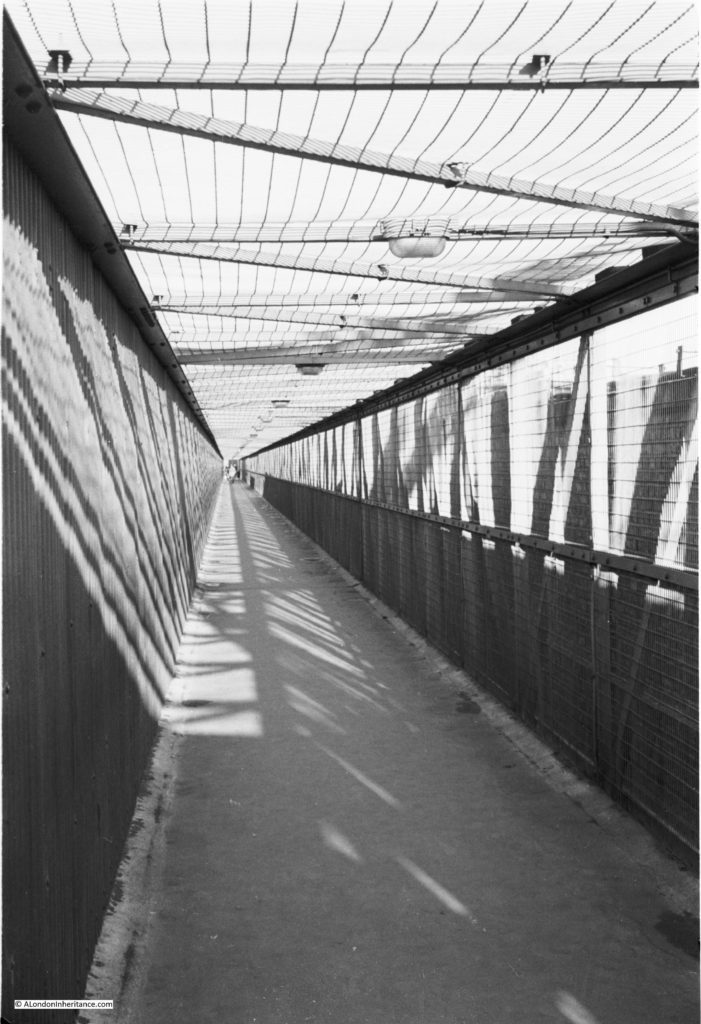

To show how quickly river trade changed, 26 years after the above description of increased activity on the river, I took the following photo in 1979, looking along the river from London Bridge:

The cranes lining the river have gone, some of the warehouses were still being used for storage, but the majority were derelict. The space where the cranes once moved cargo between ship and warehouse was then used for parking space.

Another photo from 1979 looking down the river. A few of the remaining cranes can be seen just to the right of HMS Belfast. These would have been on Mark Brown’s and Tower Bridge Wharves.

I took a couple of “now” photos in August 2020 to mirror my 1979 photos, and the following photo shows the redevelopment of the Southwark side of the river. Part of Hay’s Wharf remains, but the rest of the area has been transformed.

A riverside walk now runs where cranes once transferred goods between ship and warehouse, and where cars parked in 1979.

The following photo is an August 2020 view of my second 1979 photo and shows the redevelopment at the Southwark end of Tower Bridge, with the Mayor of London’s City Hall.

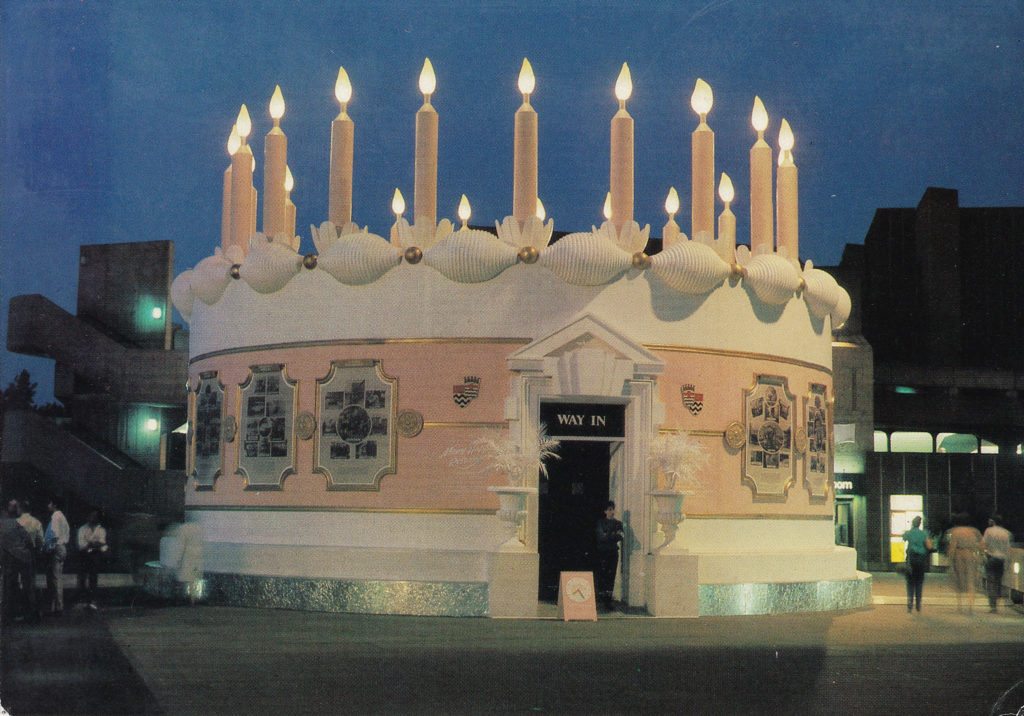

So what occupies the location of Topping’s Wharf today? The whole Southwark stretch of the river between London and Tower Bridges was marked for development in the 1980s, and by 1986 “Number 1 London” had been constructed. A two part building complex with a 13 storey tower adjacent to London Bridge and a smaller 10 storey section on the site of Topping’s Wharf.

In the following photo, taken from the top of the Shard, London Bridge is on the left. The two buildings of Number 1 London are of similar design and materials and can be seen to the right of the bridge, directly on the river. The smaller of the two buildings is where Topping’s Wharf was located.

A view of the location from the river. Topping’s Wharf was located where part of the glass canopy and the building to the left of the canopy now stand.

In my father’s 1948 photo at the top of the post there are a line of identical cranes between the warehouses and river. These are the 240 cwt. or hundredweight (approximately 12,192 kg) cranes listed in the Commercial Motor specifications for each wharf.

The most newsworthy appearance of the cranes was during the funeral of Winston Churchill in 1965. His coffin was carried along this stretch of the Thames, and the cranes bowed in turn as the boat carrying his coffin passed. This can be seen in a British Pathé film of the funeral, which can be found here – the cranes can be seen starting at 9 minutes.

If you want to see part of the street that ran behind the warehouses at the Tower Bridge end of the river, then see my post on the Lost Warehouses of Pickle Herring Street.

There is far more to discover along this stretch of the river. The 300 year history of Hay’s Wharf and the lost church of St. Olave are just two examples. These will have to wait for future posts.