In 1948, my father took a couple of photos of repair work underway to the rather impressive Cumberland Terrace to the east of Regent’s Park:

Bomb damage seems to have been rather superficial to the terrace, with the main damage being to the rear of the buildings, and I suspect that the scaffolding was there due to urgently needed repair and refurbishment work, as the buildings had deteriorated significantly during the first decades of the 20th century, which was not helped by lack of maintenance during the war.

The central building in the terrace has a large sculptural pediment, which can be seen above the scaffolding in the above photo.

Walking past the central building, and the northern section of the terrace (which mirrors the southern section), can be seen, where three large blocks with Ionic columns, project towards the street:

Cumberland Terrace is the most impressive of the terraces and large houses along the eastern edge of Regent’s Park.

Regent’s Park was originally part of a Royal hunting ground created by Henry VIII, when he took the land formerly known as Marylebone Park, which was part of the large mix of common and forest land to the north and west of London.

During the Civil War in the mid 17th century, much of the land was sold off to tenant farmers, and by the end of the 18th century, the growth of London was such, that as with much of west and north London, the land which is today now occupied by Regent’s Park was becoming a valuable area for building.

Luckily, the Prince Regent (the future King George IV) was looking for a site to build a summer palace, along with extensive gardens, and to provide space for this, much of the old tenant farming land was partitioned off to become Regent’s Park.

The Prince Regent commissioned the architect John Nash to design the new park, the summer palace and the surroundings of the park.

Nash was one of the major architects of the late 18th / early 19th century. Born in Lambeth, and probably the son of engineer and millwright William Nash, his first experience within the architectural profession was with Sir Robert Taylor where he became an assistant draughtsman.

By 1777, he was an architect and speculative builder in London, but was better at architecture than finance as he soon went bankrupt.

He then joined another partnership in Wales working on small projects, and by 1796, he had returned to London, where he formed a partnership with the landscape gardener Humphrey Repton (who was responsible for the original design of Russell Square).

The partnership with Repton had been dissolved by 1802, and by this time, Nash was considered a fashionable architect, and was responsible for a large number of projects across the country.

His involvement with the planning of Regent’s Park came about because of his appointment in 1806 as architect to the Department of Woods and Forests, the department responsible for the development of the land that was to become Regent’s Park, which had recently reverted to Crown ownership.

The plan for the Regent’s Park was that it would be a landscaped open space with the Prince Regent’s summer palace, a small number of private villas and surrounded by handsome terraces.

This approach would mean that Regent’s Park was not just a new park, but was also a new fashionable residential area for London.

The following map shows Regent’s Park as it is today. The arrow points to Cumberland Terrace:

The Regent’s Canal runs along the northern boundary of the park (Nash also had some involvement with the canal). London Zoo is at the north of the park. Terraces and large houses occupy much of the eastern boundary of the park, there are a number of villas to the north, and more terraces and houses along the western boundary.

The Prince Regent’s planned summer palace did not get built, he appears to have lost interest, and there were not as many of the large, individual villas as originally planned, however as designed by Nash, the park and the surrounding buildings are an impressive example of Regency architecture from the start of the early 19th century.

It is some time since I last walked through the terraces that line the eastern boundary of Regent’s Park, so last week I planned a visit. The weather on Monday was clear and bright, but I was not free for a day of walking. Tuesday though looked good, the forecast showing a mix of light cloud and sunny intervals, but such is the nature of weather forecasts that when I reached the Outer Circle (the road that forms the boundary to the central park), it had started snowing:

The walk up from Euston Road to find Cumberland Terrace, along the eastern boundary took me through and past a number of very impressive houses and terraces.

The first is the Grade I listed Chester Terrace, where the entrance to the road that runs in front of the terrace has a triumphal arch proclaiming the name of the terrace:

Chester Terrace, designed by Nash and built by James Burton is around 280 metres in length and is the longest unbroken façade in the Regent’s Park development.

The terrace consists of 37 houses and 5 semi-detached houses, and is at a raised level to the Outer Circle, and is separated from this street by private gardens. Chester Terrace dates from around 1825:

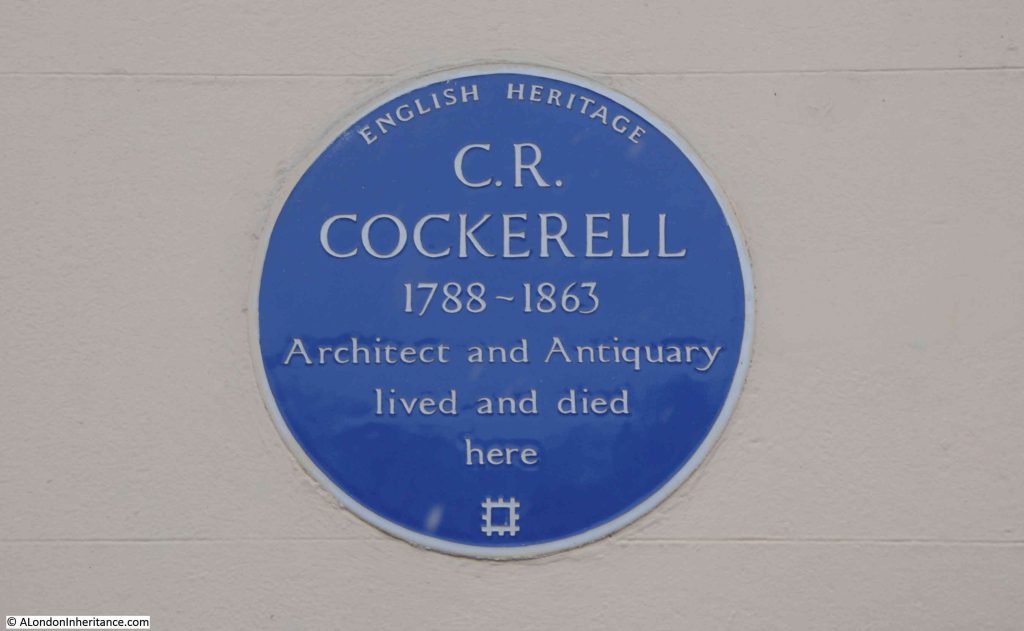

Given that the terraces to the east of Regent’s Park are around two hundred years old, and provided what must have been highly desirable homes in an equally desirable part of London, there are very few blue plaques across the terraces.

Chester Terrace has two, the first to the architect Charles Robert Cockerell, who was responsible for a large number of works across the country, and in London he worked on the Sun Fire Office in Threadneedle Street, the London and Westminster Bank in Lothbury, the Westminster Insurance Company’s offices in the Strand, the Hanover Chapel in Regent Street, the 1821 new ball and cross on St. Paul’s Cathedral, and many more:

Looking back to the southern arch to Chester Terrace, Cockerell’s blue plaque can just be seen on the left:

Looking along Chester Terrace, building works were taking place on the road and boundary wall to the gardens on the left:

In the above photo, there is a building with 8 free-standing, fluted Corinthian columns, then a building undergoing work and covered in scaffolding.

(A comment on Ionic and Corinthian Columns as I use both terms in this post. With my limited architectural understanding, the easiest way of confirming the type of column is that Corinthian have decorated work at the top of the column, while Ionic have a more simple finish, often looking rather like a scroll at the top of the column. As always, more informed feedback than I can provide is appreciated in the comments to the post).

Walk past the building with scaffolding, and there is another building with Corinthian columns, although with 6 rather than 8, and not projecting as far from the façade of the building. The pattern of columns alternates along the terrace, starting with from the south, 8, then 6 then 8, then 6, then finally 8 at the northern end of the terrace:

In the above photo there is another blue plaque, to Sir John Maitland Salmond, Marshal of the Royal Air Force. Salmond was one of the early pilots of the Royal Flying Corp, and in the Register on the 14th of March 1914, it was reported that: “For a flight 13,140 feet high in a B.E. (government built) biplane, Captain J.M. Salmond of the Royal Flying Corp has been granted by the Royal Aero Club the British altitude record”:

The thought of flying at over 13,000 feet in a government built biplane is a rather scary one.

At the end of Chester Terrace is another triumphal arch, and through this we can see one of the large houses that are also part of the development along the eastern boundary of Regent’s Park:

Walking to the end of Chester Terrace, and looking to the right, there is another arch that leads away from the Nash developments down towards Albany Street:

My father would have known this area well, as he lived a very short distance away. Not in one of the Nash buildings, but in what is still a Peabody estate, Bagshot House in the Cumberland Market estate – see this post.

Cumberland Place, which leads round to Cumberland Terrace:

The full length of Cumberland Terrace from the southern end:

Cumberland Terrace was the work of John Nash and James Thomson. It is difficult to know who was exactly responsible for what, and how much of the design was down to Nash or Thomson, however the overall design was certainly down to Nash, as the terrace was part of his vision for grand terraces along the boundary of Regent’s Park.

The terrace consist of 59 houses and was completed in around 1827. If differs from Chester Terrace in that it is not a continuous row of houses and there are two triumphal arches which lead into courtyards, not over the entrance road, but within the terrace, as shown in the following photo:

Cumberland Terrace was intended to be the most impressive of all the terraces, and at the centre is the building that was planned to give the impression of being a palace, looking out from its elevated position, over Regent’s Park. Only just visible in the following photo, at the top of the central building, above the Ionic columns is a Tympanum full of sculpture. A tympanum is the triangular space within a pediment that is frequently decorated, as in Cumberland Terrace:

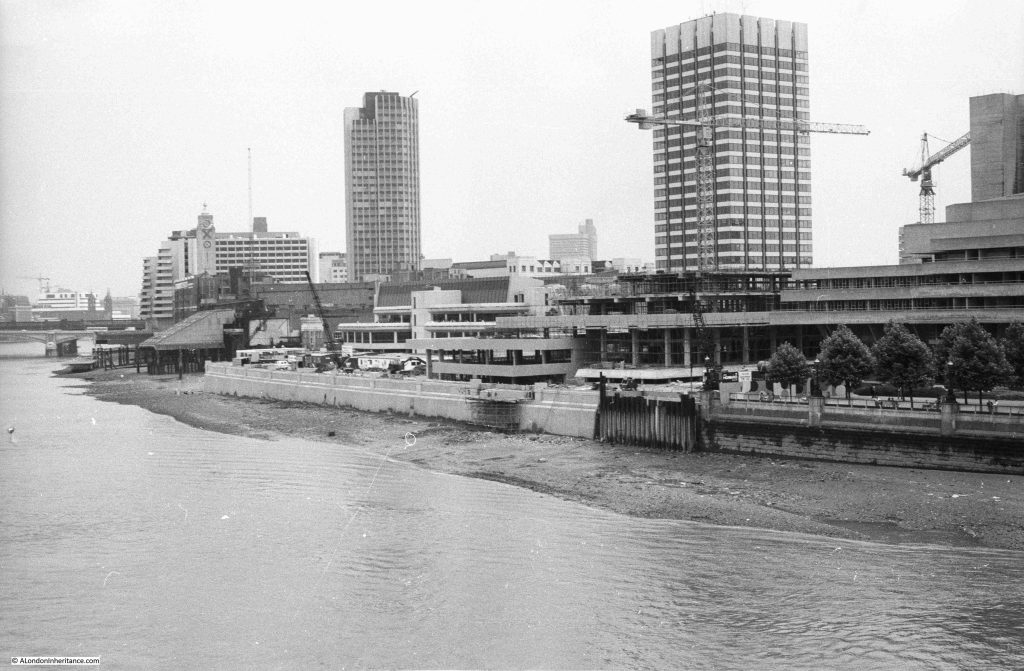

This central building was the one covered in scaffolding in my father’s photos, another of which is shown below:

There had been some limited bomb damage to Cumberland Terrace, mainly to the rear rather than the front of the buildings. The main reason for repair work was the poor condition of the buildings after a long period of relatively limited maintenance, and years of wartime deterioration.

There was a risk that the buildings were going to be demolished, however they found another immediate post-war use, as reported in the Daily London News in April 1946:

“The Nash Houses To Be Spared – Terraces of houses designed by John Nash in Regent’s Park, which it was feared might be demolished, are to become an annexe of Whitehall.

The News Chronicle recently reported a protest by three writers, Elizabeth Bowen, Cyril Connolly and H.G. Wells, who all live in the Nash terraces in the Park, against the possible demolition of these fine specimens of Georgian building.

Last year a committee under Lord Gorell was appointed by the Prime Minister to report on the future of these buildings. Now the Government has already decided to take over 200 houses in Sussex Place, Cornwall Terrace, York Terrace, Chester Terrace and Cumberland Terrace.

Various Ministries will move departments there, freeing their present premises for use as offices and flats.”

What the above article did not report, was that Lord Gorell’s committee had stated that the terraces were an important part of the Nation’s architectural and artistic heritage, that they should be preserved as far as was possible, and that they should be residential and not offices, and the Government occupation should cease at the earliest possible time.

This was reported in the Illustrated London News on the 24th of May 1947, which included concerns about the physical state of the terraces. They had been built at a time when “the contemporary quality of building was at a very low ebb from a structural point of view. The quality of the maintenance of the houses has varied greatly, but dry-rot is very extensive and some of the serious outbreaks were prior to 1939”,

A further article in April 1950 in the Illustrated London News confirmed that repairs to the terrace had been underway, and the scaffolding which my father photographed must have been part of this work.

Some of the photos in the Illustrated London News show much of the internal woodwork being exposed and removed due to dry-rot.

The northern part of Cumberland Terrace:

In the above photo, the gardens that separate Cumberland Terrace from the Outer Circle can be seen, as well as the drop in height from the terrace down to the gardens, the Outer Circle and the rest of the park, which gave the terrace an elevated view over the park, and also made the terrace look more impressive from the park.

The above view includes the area covered by another of my father’s photos:

At the end of the terrace, the road leads down to the Outer Circle, with another example of the houses that make up the estate as well as the terraces, at the far end of the road:

Although there are modern street names signs, the terraces and their surrounding streets are mainly a place of black painted name signs:

The names of all the terraces and other significant buildings around the park, as part of Nash’s development, all come from the Royal Family, so Cumberland Terrace is named after Ernest Augustus, the King of Hanover and Duke of Cumberland. He was the fifth son of George III.

Chester Terrace comes from George IV, as the Earl of Chester was one of his titles before he became king.

As far as I can tell, the majority of the Nash terraces and houses are still owned by the Crown Estate.

Following a quick search, I could not find any detailed listing of the properties owned by the Crown Estate, however they do state on their website that Regent’s Park is one of the areas where they hold a residential portfolio of properties.

In the following photo, I am looking along the Outer Circle, the road that forms the boundary to Regent’s Park. The gardens to the left provide privacy to the terrace, and Cumberland Terrace can be seen behind the gardens:

Cumberland Terrace is all Grade I listed, and the Historic England listing record describes the terrace as “Monumental palace-style terrace”, and from the Outer Circle we can see how the terrace, especially the central part of the terrace, was meant to be seen – an impressive, ornamental palace, overlooking the Prince Regent’s new park, and part of a fashionable new housing estate for London:

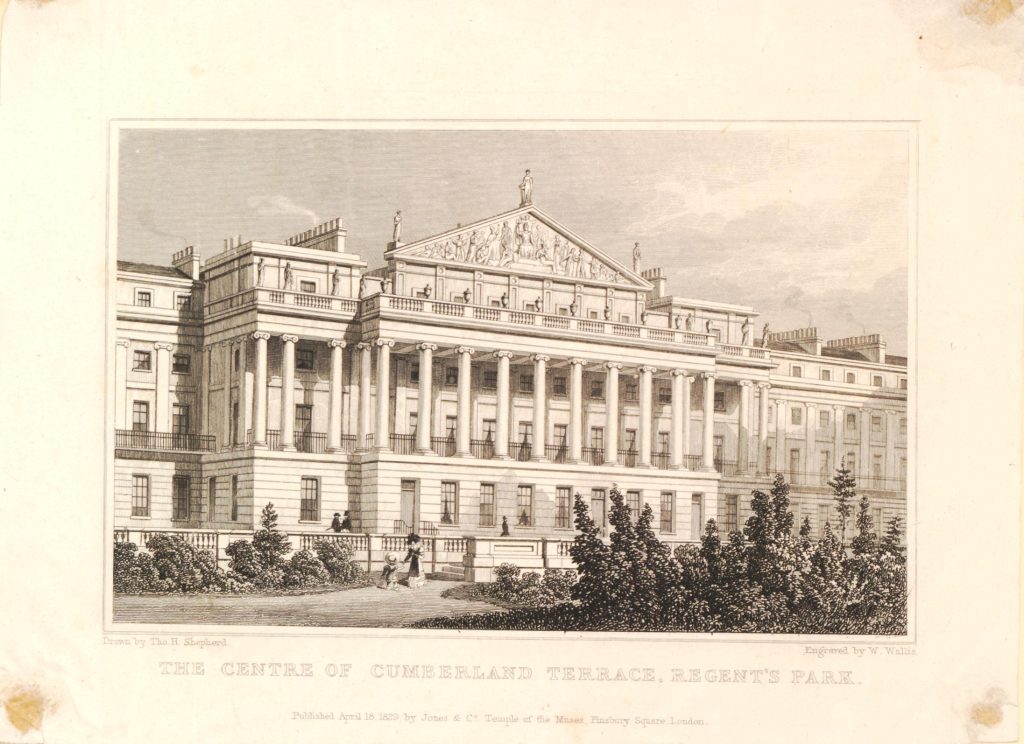

The following print dates from 1829, only a couple of years after completion of the terrace, and shows the central part of the terrace looking much the same as it does today:

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

The decoration within the pediment is hard to see when walking along Cumberland Terrace, and it is only from the Outer Circle and the park that this impressive work can be seen fully:

The Public Ledger on the 29th of September 1827 included the following description of the terrace and pediment soon after completion:

“Among the very numerous embellishments to our Metropolis which have so closely succeeded each other since the commencement of the Regency, and which will, when the whole in present progress, and these to which these must inevitably give rise, shall be completed, render it still more the wonder of foreigners, we view with peculiar pleasure the improvements in the Regent’s Park.

In that delightful spot, the Cumberland Terrace must ever be an object of admiration. The pediment to that long length of handsome dwellings is nearly finished, and we expect will be viewed with much admiration.

The subject is boldly conceived, and the work is, we think, well executed. Britannia appears crowned by Fame. She is seated on her throne, supported by the emblems of Valour and of Wisdom. On one side, Literature, Genius, Manufacture, Agriculture and Prudence. On the other Navy surmounted by Victory, and attended by Navigation, Commerce and Freedom, extends blessings to the world; and the interesting group is surrounded by the symbols of Plenty.

Not only will the pediment be attractive, but over the 32 columns there are to be as many statues with a quantum sufficit of sphynxes, vases and other decorations.”

And the many statues listed in the article, as well as the sphynxes and vases are still to be seen:

And here:

Cumberland Terrace is a very impressive example of Nash’s work around Regent’s Park, and Cumberland Terrace was often used as an example of quality design.

In the second half of the 1940s, the luxury car brand Lagonda was advertising that “Cumberland Terrace, Regent’s Park, by John Nash characterises a flourishing period of design. As with this noble early 19th century building, so with the new 2 litre Lagonda designed by W.O. Bentley. Lasting merit has been achieved through time and genius expended on conception and construction”.

Large house facing onto the Outer Circle:

The above photo shows that it was not just the terraces that had features such as Corinthian or Ionic columns and pediments. Other buildings facing towards Regent’s Park had many of the same features, to give the impression of the park being surrounded by large and small palaces or stately homes.

London has always had a housing shortage, and there was an interesting proposal for Cumberland Terrace in 1959 (from the Holloway Press):

“Tory Cllr, says FLATS NOT SUITABLE – Cumberland Terrace. Although Cllr, Miss I.C. Mansel maintained that flats in Cumberland Terrace would be unsuitable for council tenants, St. Pancras Borough Council agreed on Wednesday to a housing management committee recommendation that the Crown Estate Commissioners be asked to receive a council deputation to discuss the future of the flats.

Previously the council had asked the Lord Privy Seal to place the flats at the disposal of the council for housing families on the waiting list. The council were then told that it was proposed to let the flats at the best rates obtainable.

Cllr. Miss Mansel said the Conservative group were against the recommendation. ‘I feel these flats would be quite unsuitable for council tenants’.

The committee chairman, Cllr. Mrs Peggy Duff said there was a desperate shortage of housing accommodation and she had no doubt people would be glad to have one of these flats.”

The principle of the “best rates obtainable” still stands, as for example, there is a three bedroom, leasehold apartment in Cumberland Terrace currently on sale for £7,500,000. You can see the listing on Rightmove by clicking here.

View south along the Outer Circle, with another large house with Corinthian columns – a standard feature throughout the estate:

The road in the above photo is again the Outer Circle, the road that circles the boundary of Regent’s Park.

The Outer Circle, or Outer Drive as it was also known, was laid out as defined in Nash’s plans, between 1811 and 1812.

The two mile long road was described as a “fine broad gravel road”, and was one of the first features of the park, forming the boundary between the open parkland, and the land that would be developed into the terraces and houses covered in this post.

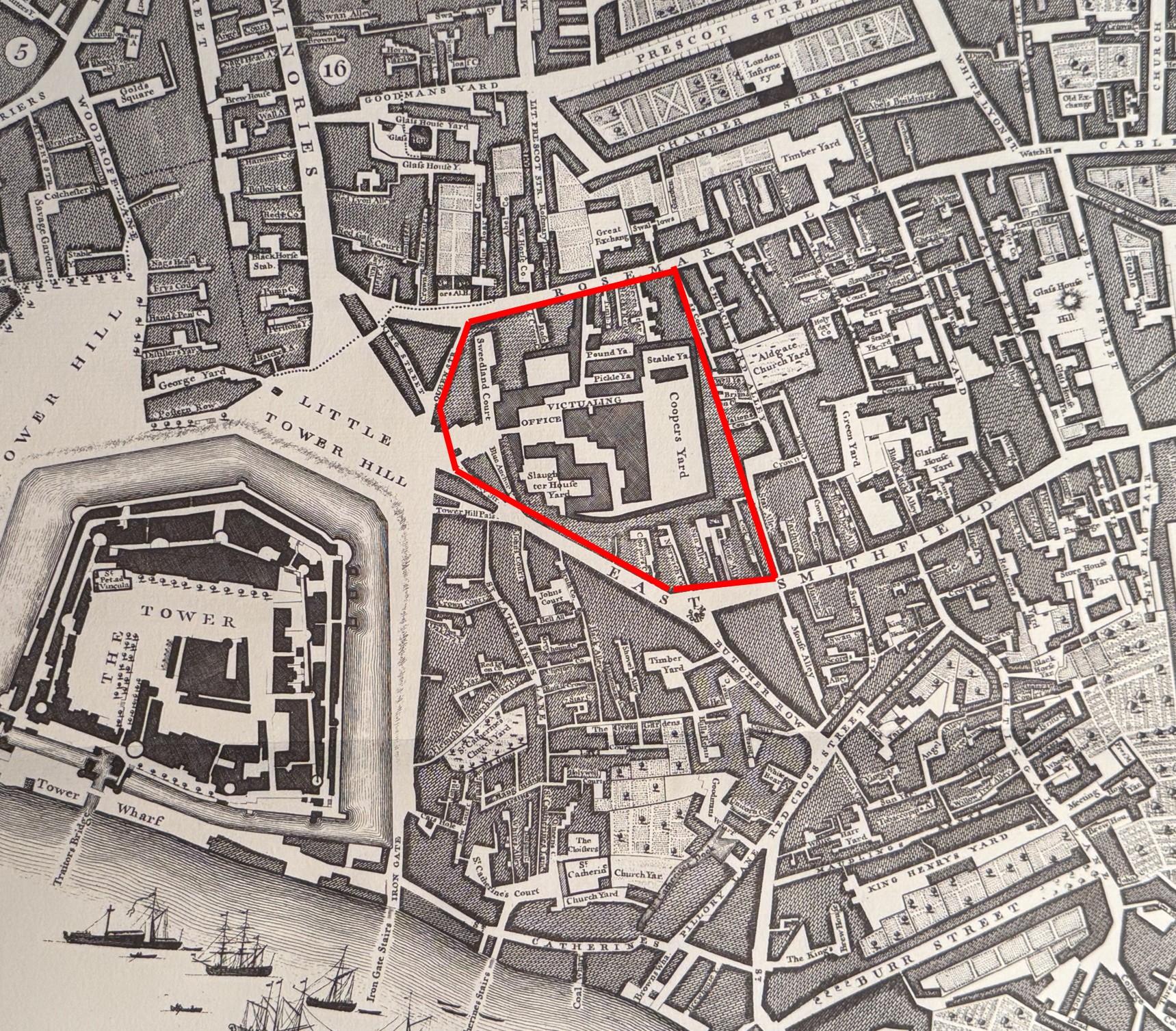

The following map shows Regent’s Park in around 1815, before the terraces and houses were built. The Outer Circle is in place, however it is named in sections, with some of the names that the future terraces would take, so for example, the section of Outer Ring in front of the future Chester and Cumberland Terraces is called Chester Street.

The land just outside the Outer Ring is labelled as “Building Ground”, and this would go on to be developed in the 1820s as shown by the photos in the post.

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

The Outer Circle was open to the public until ten in the evening, when it was closed to the public, but continued to provide access for residents. The road was designed so as you passed along the road on your horse, in your carriage, or on foot, you passed a changing series of views, of both the open parkland on one side, and the large houses and terraces on the other side, which must have seemed extraordinary and magnificent to the average Londoner.

In 1831, the artist Richard Morris created a panorama of the view around the Outer Circle.

The Yale Centre for British Art have the full panorama available on line (click here), and fortunately it has a Creative Commons Public Domain classification, so as an example of the panorama, below is the section showing Cumberland Terrace, with people enjoying the ride and walk around the Outer Circle:

An interesting part of the overall development is much further south, along Park Square East, which connects Marylebone Road to the Outer Circle, where we find this terrace:

The following print from 1829 shows the above terrace. Park Square is to the right, and the mounted soldiers are travelling along the southern section of the Outer Circle:

(© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

In the centre of the terrace shown in the above print and photo is a slightly larger building, with a sign along the roof line. This was the Regent’s Park Diorama, and the building survives to this day:

Again, Grade I listed, and by John Nash, the central Diorama was one of a number operating in London in the early 19th century.

A Diorama consists of a painting, drawings or models which are so arranged and lit, that they give the viewer the impression that they are looking at the real life scene.

Flemings Weekly Express on the 2nd of November 1823 had a description of the Regent’s Park Diorama, as follows:

“On entering the place of exhibition, you find yourself in a small circular theatre, fitted up with balconies, seats and a kind of parterre in the centre; and hung round with rich draperies; and overhead is a transparent ceiling superbly painted in arabesque, which lets in a ‘dim, religious light’.

The theatre or apartment in which you stand, is enclosed on all sides, with the exception of what seems to be about one-fourth of the circle; and this space, from the ceiling to nearly the floor, is entirely open, as if into the air. it is through this opening that you see, at what appears to be a considerable distance, the scenes which are the objects of exhibition.

One of them consists of a lovely valley in Switzerland; and it really is no exaggeration to say, that, seen from the open window of an apartment in its immediate neighbourhood, the scene itself could not produce a more enchanting effect. It is true, the feeling of being able to leave the room, and walk into it is wanting; but perhaps this is nearly compensated for by the indistinct pleasure arising from the sentiment alluded to, that what you behold is a pure creation of human art and ingenuity.”

To keep customers returning, the Diorama would provide a continually changing programme of views, with natural landscapes from Britain and the wider world, city scenes, battles, historical events etc.

By 1852, the Diorama had closed. The contents of the building were sold off the following year, and in May 1855, the building opened as a Baptist Chapel, with the first “solemn services” held to convert the space into a chapel.

The façade of the building hides the structure of the Diorama which was behind, and remarkably this structure still exists today.

The following link is to Google Maps, where the structure of the Diorama is still clearly visible behind the terrace:

https://maps.app.goo.gl/jkeNxsd76SeBaEJk8

The Nash terraces are one of the things that make walking around London so fascinating – the considerable diversity of architectural style and landscape planning. It is important to consider the terraces and large houses as part of the overall design of Regent’s Park, and with Cumberland Terrace, it is clear that the terrace was designed to provide the impression of a palace overlooking the park.

London’s changeable weather also makes walking interesting, and whilst these terraces look magnificent in the sun of a summer’s day, they look just as good in the light of a dull January day, with a dusting of snow across the streets and pavement.