Caledonian Park in north London in the Borough of Islington is today a green space in a busy part of London, with few reminders of the areas rich history.

I have much to write about Caledonian Park so I will cover in two posts this weekend. Today some historical background to the area, some lost murals and finding the location of one of my father’s photos. Tomorrow, climbing the Victorian Clock Tower at the heart of the park to see some of the most stunning views of London.

Caledonian Park is a relatively recent name. Taking its name from the nearby Caledonian Road which in turn was named after the Caledonian Asylum which was established nearby in 1815 for the “children of Scottish parents”.

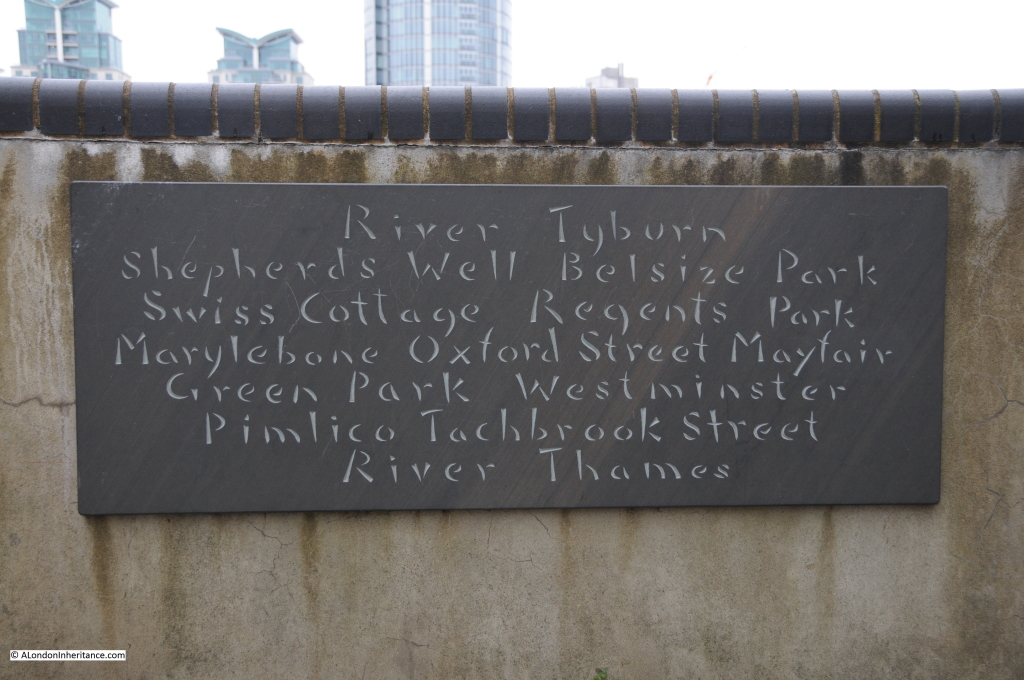

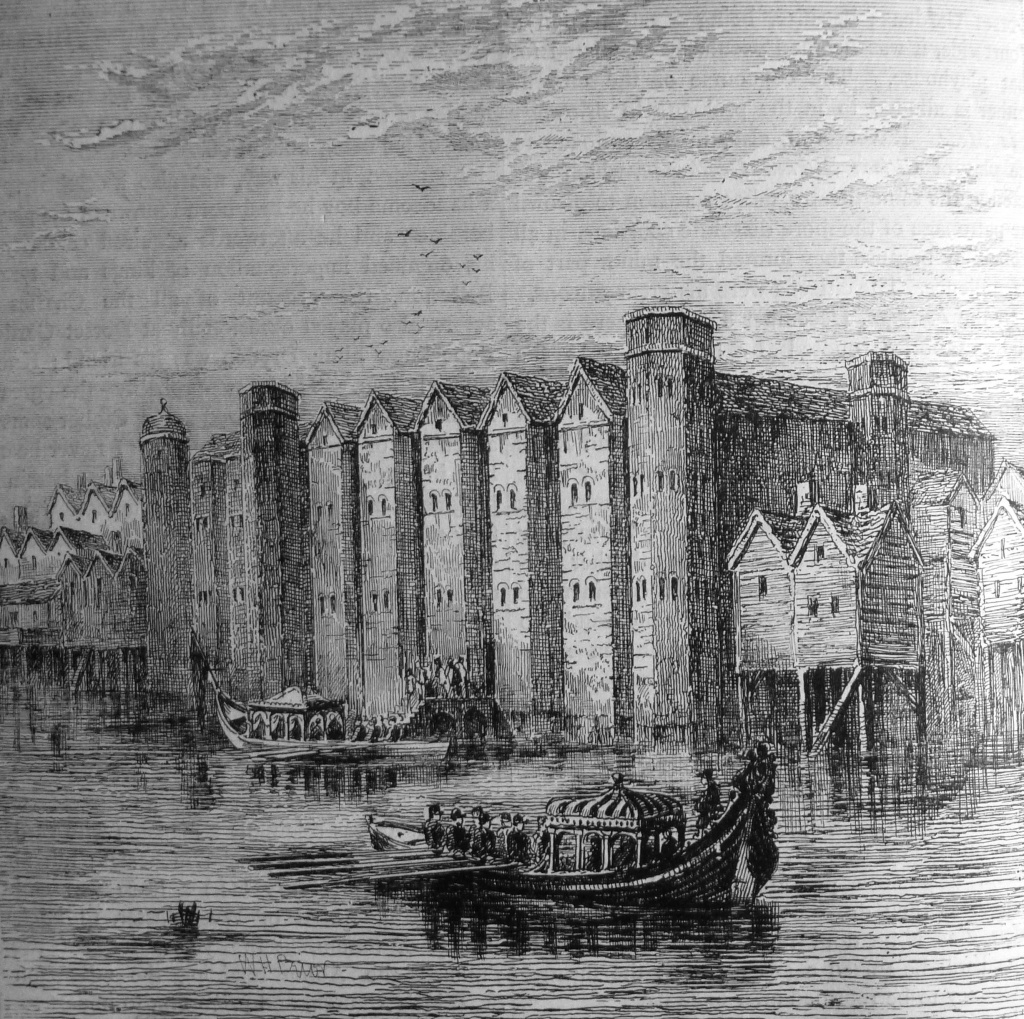

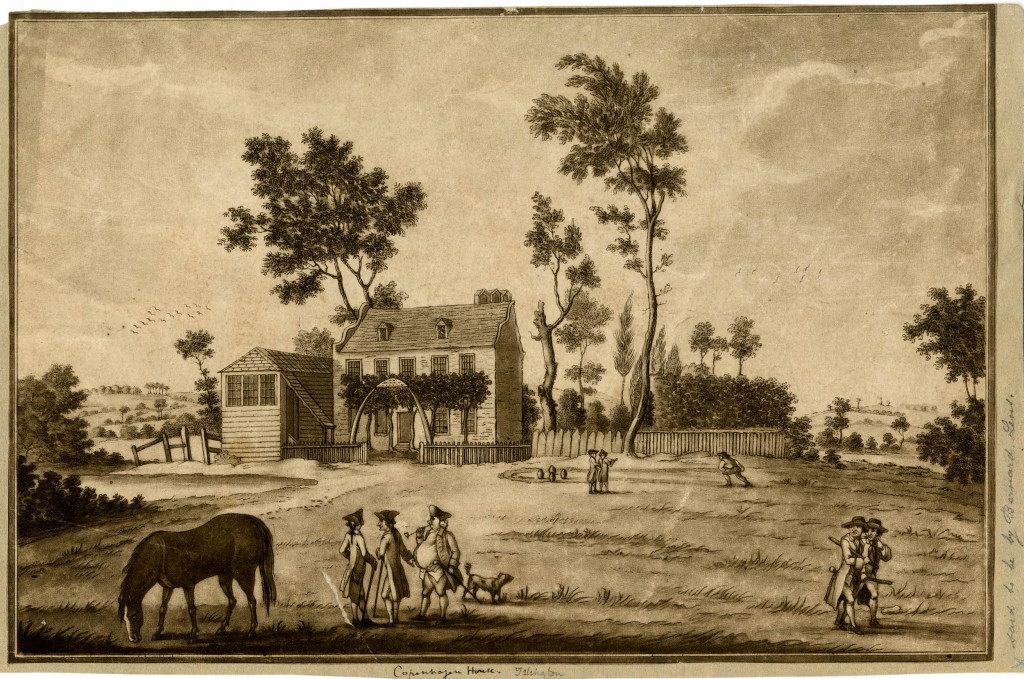

Prior to the considerable expansion of London in the 19th century, the whole area consisted of open fields and went by the name of Copenhagen Fields. There was also a Copenhagen House located within the area of the current park.

The origin of the Copenhagen name is probably down to the use of the house (or possibly the construction of the house) by the Danish Ambassador for use as a rural retreat from the City of London during the Great Plague of 1665.

Copenhagen House became an Inn during the early part of the 18th century and the fields were used for sport, recreation and occasionally as an assembly point for demonstrations, or as Edward Walford described in Old and New London, the fields were “the resort of Cockney lovers, Cockney sportsmen and Cockney agitators”

The following print shows Copenhagen House from the south east in 1783, still a very rural location.

©Trustees of the British Museum

©Trustees of the British Museum

During the last part of the 18th century, Copenhagen Fields was often used as a meeting point for many of the anti-government demonstrations of the time. Old and New London by Walter Thornbury has a description of these meetings:

“In the early days of the French Revolution, when the Tories trembled with fear and rage, the fields near Copenhagen House were the scene of those meetings of the London Corresponding Society, which so alarmed the Government. The most threatening of these was held on October 26, 1795, when Thelwall, and other sympathisers with France and liberty, addressed 40,000, and threw out hints that the mob should surround Westminster on the 29th, when the King would go to the House. The hint was attended to, and on that day the King was shot at, but escaped unhurt.”

The meetings and threats from groups such as the Corresponding Societies led to the Combination Acts of 1799 which legislated against the gathering of men for a common purpose. It was this repression that also contributed to the Cato Street Conspiracy covered in my post which can be found here.

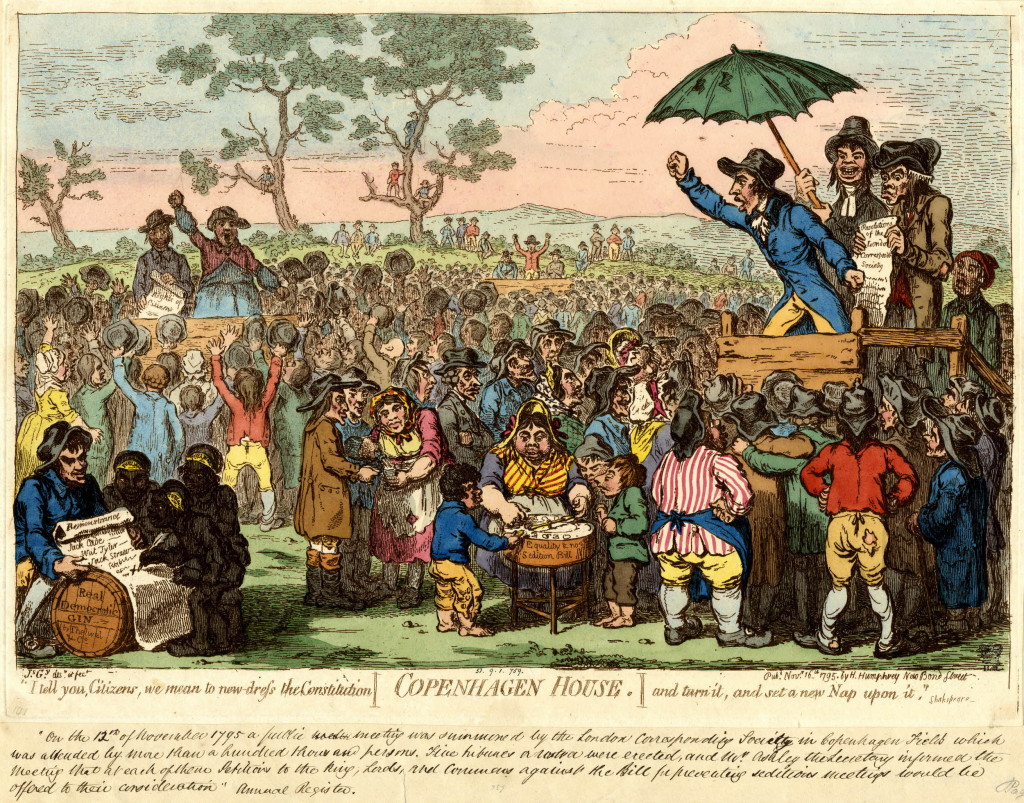

The following is a satirical print from 1795 by James Gillray of a meeting on Copenhagen Fields “summoned by the London Corresponding Society” which was “attended by more than a hundred thousand persons”.

©Trustees of the British Museum

Copenhagen Fields continued to be used for gatherings. In April 1834 there was a meeting in support of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, who had been sentenced to transportation to Australia for forming a trade union. Walter Thornbury provides the following description: “an immense number of persons of the trades’ unions assembled in the Fields, to form part of a procession of 40,000 men to Whitehall to present an address to his Majesty, signed by 260,000 unionists on behalf of their colleagues who had been convicted at Dorchester for administering illegal oaths”.

The final large meeting to be held in Copenhagen Fields was in 1851 in support of an exiled Hungarian revolutionary leader. The role of this rural location was about to change very dramatically.

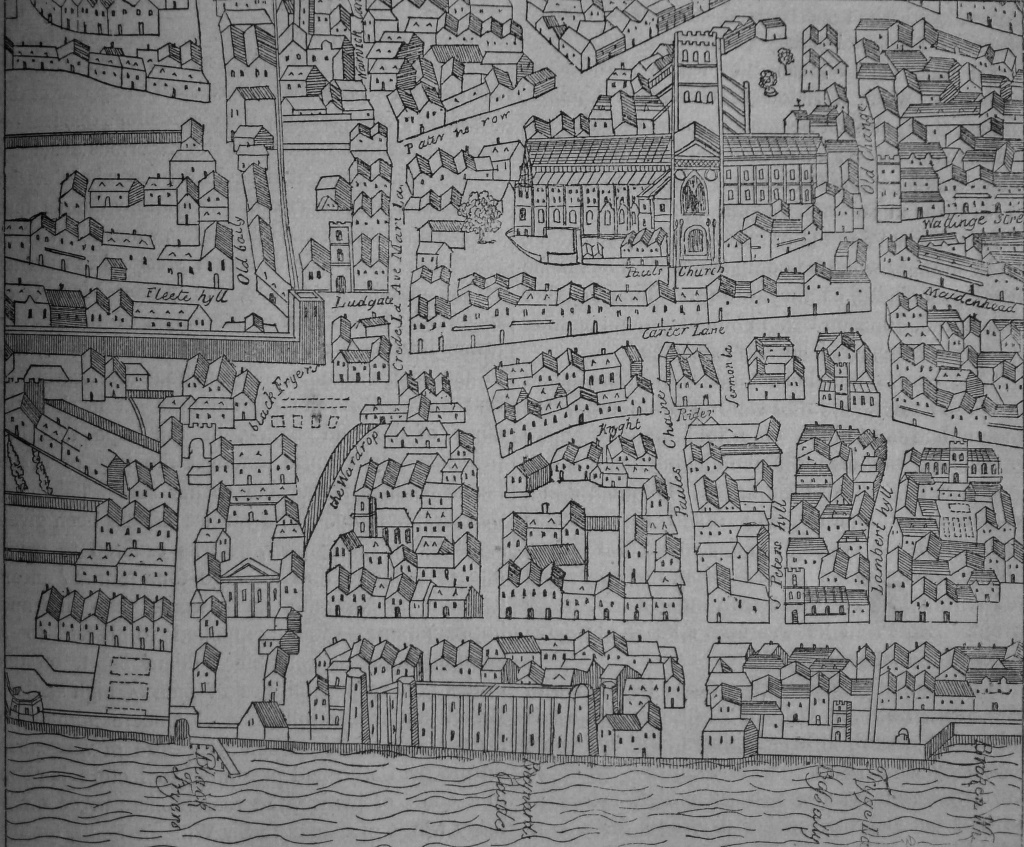

Smithfield in the city was originally London’s main cattle market however during the first half of the 19th century the volume of animals passing through the market and the associated activities such as the slaughter houses were getting unmanageable in such a densely populated part of central London.

The City of London Corporation settled on Copenhagen Fields as the appropriate location for London’s main cattle market and purchased Copenhagen House and the surrounding fields in 1852. The site was ideal as it was still mainly open space, close enough to London, and near to a number of the new railway routes into north London.

Copenhagen House was demolished and the construction of the new market, designed by the Corporation of London Architect, James Bunstone Bunning was swiftly underway, opening on the 13th June 1855.

A ground penetrating radar survey of the area commissioned by Islington Council in 2014 identified the location of Copenhagen House as (when viewed from the park to the south of the Clock Tower) just in front and to the left of the Clock Tower.

The sheer scale of the new market was impressive. In total covering seventy five acres and built at a cost of £500,000. There were 13,000 feet of railings to which the larger animals could be tied and 1,800 pens for up to 35,000 sheep.

Market days were Mondays and Thursdays for cattle, sheep and pigs, and Fridays for horses, donkeys and goats. The largest market of the year was held just before Christmas. In the last Christmas market at Smithfield in 1854, the number of animals at the market was 6,100. At the first Christmas market at the new location, numbers had grown to 7,000 and by 1863 had reached 10,300.

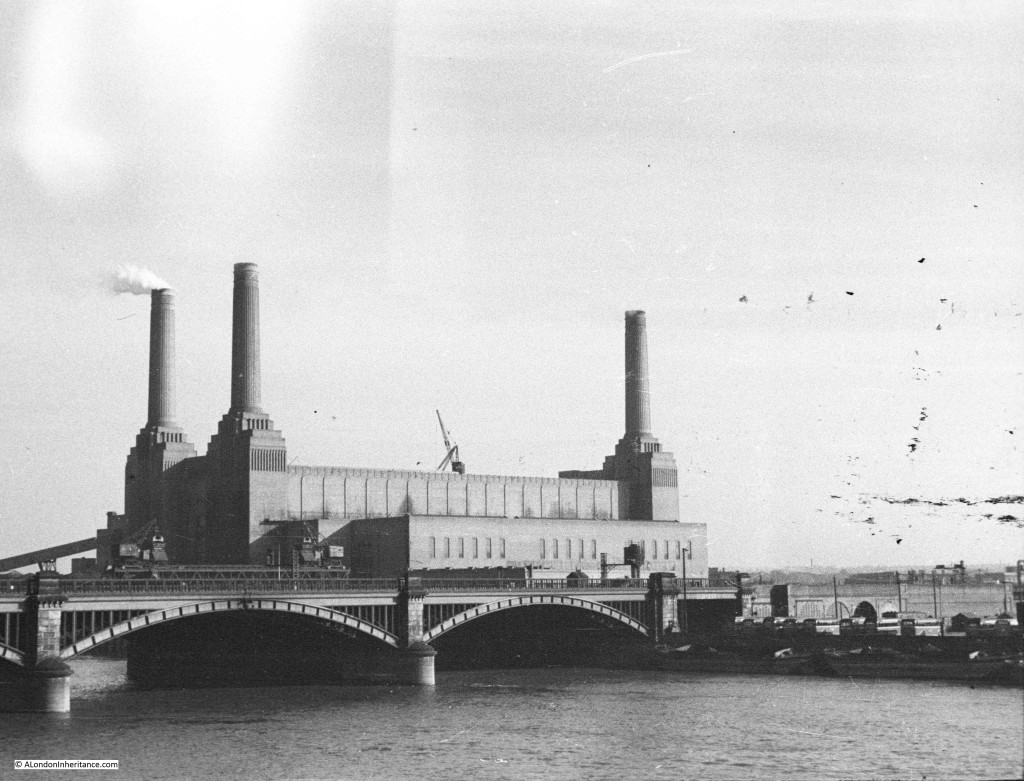

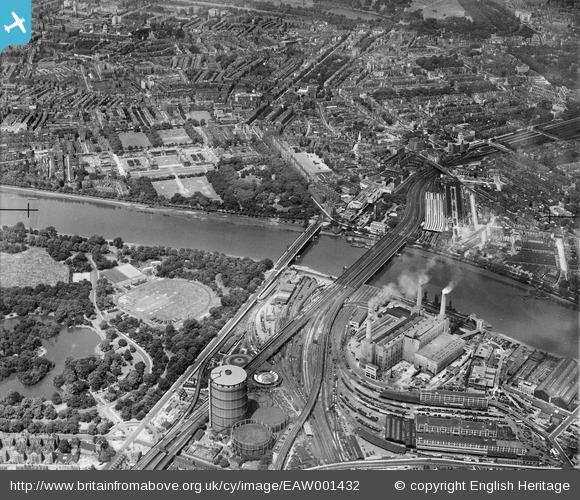

The following Aerofilms photo from 1931 shows the scale of the market. The clock tower at the centre of the market is also at the centre of the photo with the central market square along with peripheral buildings in the surrounding streets.

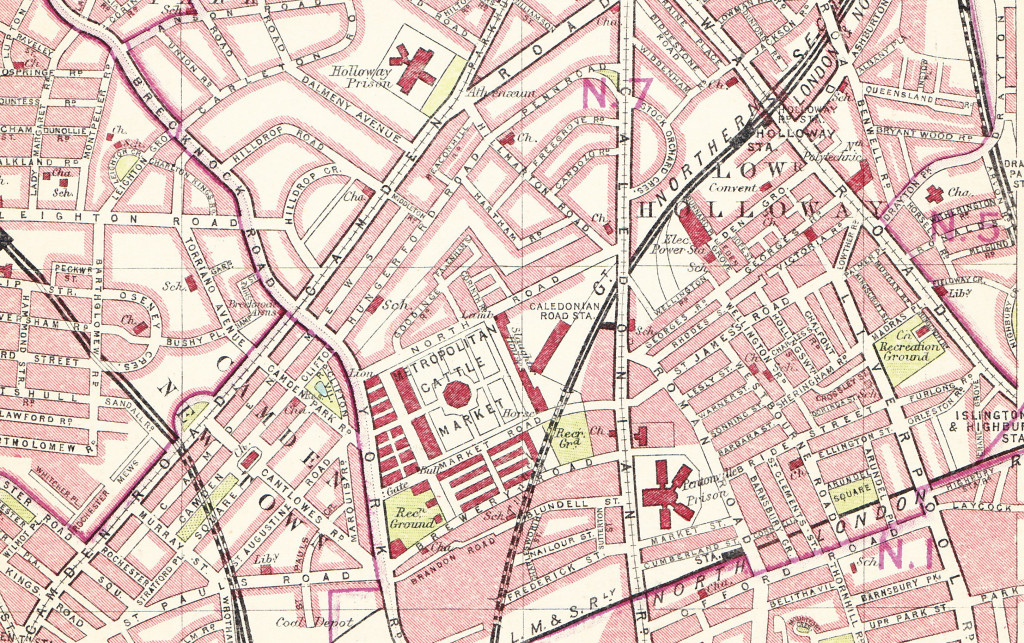

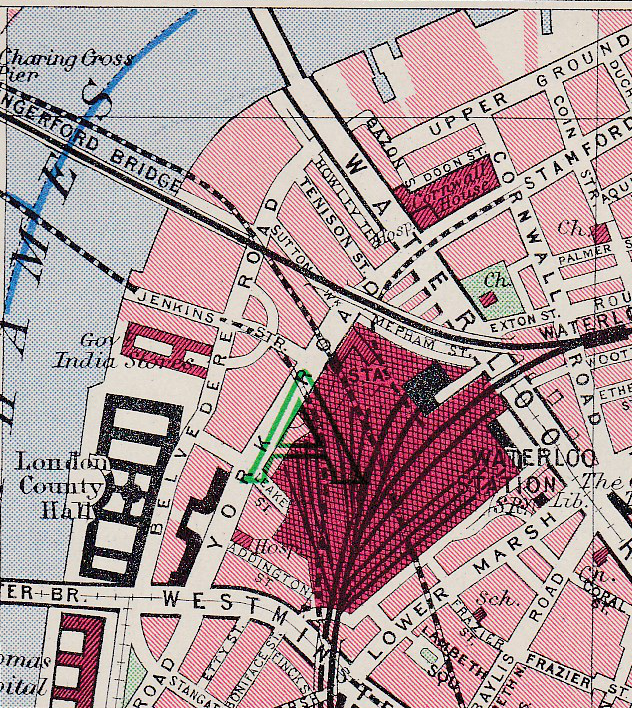

The 1930 edition of Bartholomew’s Handy Reference Atlas of London shows the location and size of the market:

As well as the cattle market, the construction included essential infrastructure to support those working and visiting the market. Four large public houses were built, one on each of the corners of the central square. The following Aerofilms photo from 1928, shows three of the pubs at corners of the main square. The two large buildings to the left of the photo are hotels, also constructed as part of the market facilities

The clock tower is located in the middle, at the base of the clock tower are the branch offices of several banks, railway companies, telegraph companies along with a number of shops.

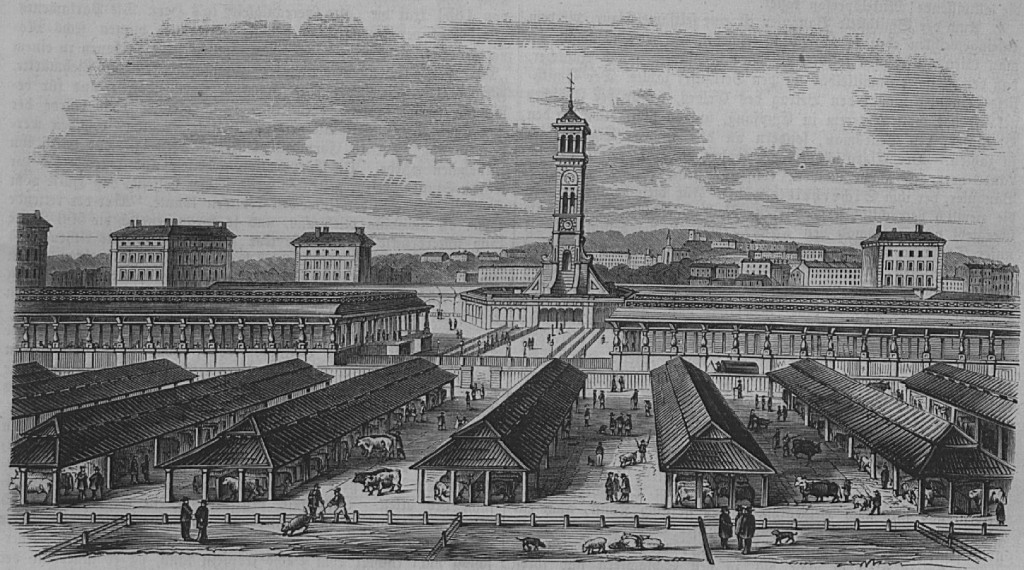

A 19th century drawing shows the clock tower and the long sheds that covered much of the market:

By the time of the First World War, the cattle market had started to decline and was finally closed in 1939 at the start of the Second World War, with the site then being used by the army.

After the war, the slaughter houses around the market continued to be used up until 1964, when the London County Council and the Borough of Islington purchased the site ready for redevelopment. The Market Housing Estate was built on much of the site, although by the 1980s the physical condition of the estate had started to decline significantly, and the estate had a growing problem with drugs and prostitution. Housing blocks were built up close to the clock tower and there was limited green space with many concrete paved areas surrounding the housing blocks and the clock tower.

A second redevelopment of the area was planned and planning permission granted in 2005. The last of the Market Estate housing blocks was demolished in 2010 and it this latest development which occupies much of the area today.

In 1982 a number of murals illustrating the history of the market were painted on the ground floor exterior of the main Clock Tower building of the original Market Estate. In 1986 my father took some photos of the murals during a walk round Islington. As far as I know, these murals were lost during the later redevelopment of the area.

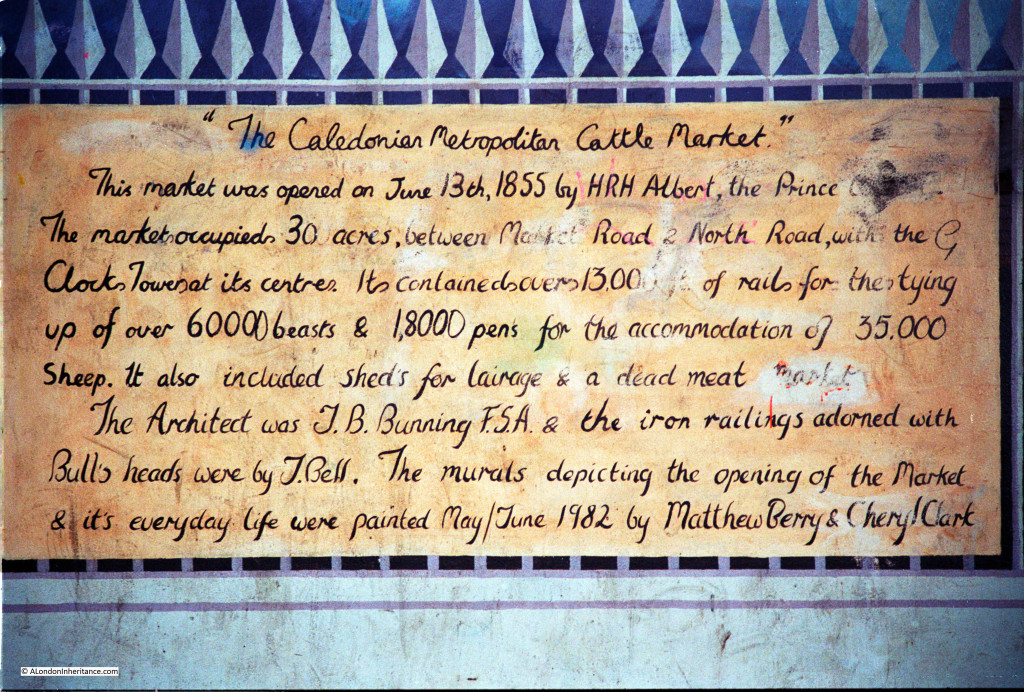

The introductory mural providing some history of the market:

A scene showing the opening of the market by Prince Albert in 1855. A lavishly decorated marquee hosted a thousand invited guests to mark the opening of the market.

The central clock tower painted on the Clock Tower building of the housing estate:

Other scenes from around the market:

As well as the photos of the murals, almost 40 years earlier in 1948 my father had taken a photo of the aftermath of a fire. I was unsure where this was and I published the photo below a few weeks ago in my post on mystery locations.

One of the messages I had in response to this post (my thanks to Tom Miler), was that the building at the back of the photo looked like one of the pubs at the Caledonian Market.

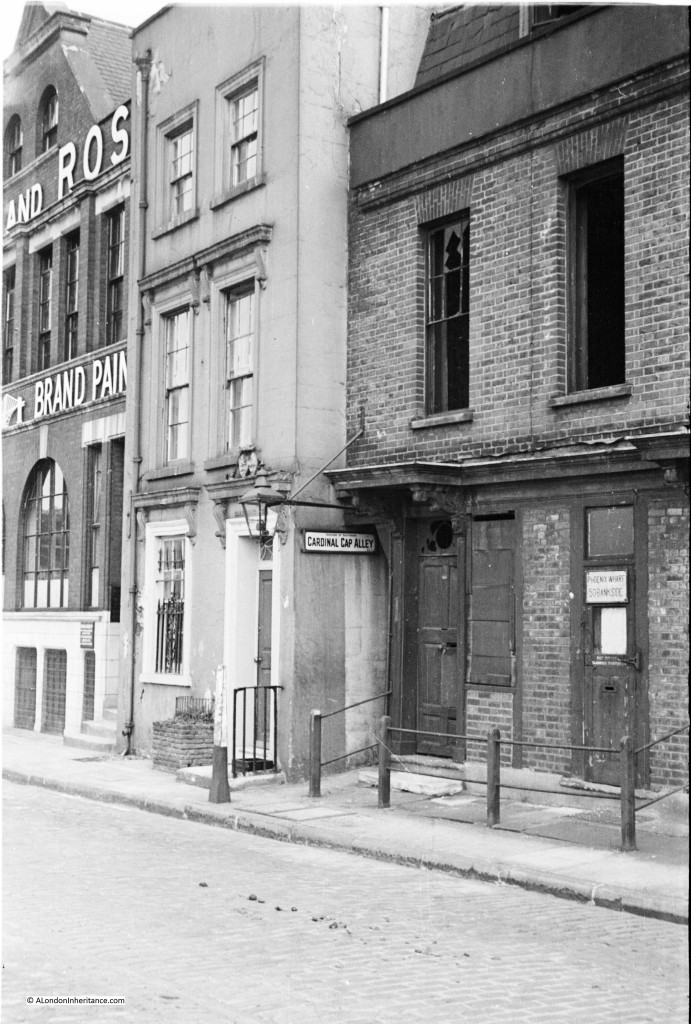

I took a walk around the periphery of the site trying to work out which of the streets and pubs could be the location of my father’s photo and found the following:

This, I am sure, is the location of my father’s photo. The street is Shearling Way running along the eastern edge of Caledonian Park. I probably should have been a bit further back to take the photo, however the rest of the road was closed and full of cars unloading students into the student accommodation that now occupies the southern end of Shearling Way – an indication of how much the area has changed.

The pub is hidden behind the tree, although it is in the same position and the chimneys are clearly the same and in the right position. The old yards and sheds that had burnt down on the right of the original photo have been replaced by housing.

I was really pleased to find the location of this photo, it is one I thought I would not be able to place in modern day London.

This Aerofilms photo from 1948 shows the pub from the above photo at the top left of the main market square with the road running up to the right. Above the road is the area that was the scene of the fire.

This is another photo of the scene of the fire and the housing in the background can also be seen in the above Aerofilms photo, further confirming the location.

Walking down the street I took the following photo of the pub, the front of the pub has the same features as on the 1948 photo.

The pub was The Lamb, unfortunately, as with the other pubs on the corners of the old cattle market, it is now closed.

To the left of the first half of the street, adjacent to the park, the original market railings are still in place:

A short time after the opening of the Cattle Market, a general or flea market had become established alongside. This market grew considerably and was generally known as the Cally Market, a place where almost anything could be found for sale. By the start of the 20th century, the size of the Cally Market had outgrown the original Cattle Market.

The journalist and author H.V. Morton visited the market for his newspaper articles on London and later consolidated in his book “London” (published in 1925) and wrote the following:

“When I walked into this remarkable once a week junk fair I was deeply touched to think that any living person could need many of the things displayed for sale. For all round me, lying on sacking, were the driftwood and wreckage of a thousand lives: door knobs, perambulators in extremis, bicycle wheels, bell wire, bed knobs, old clothes, awful pictures, broken mirrors, unromantic china goods, gaping false teeth, screws, nuts, bolts and vague pieces of rusty iron, whose mission in life, or whose part and portion of a whole, Time had obliterated.”

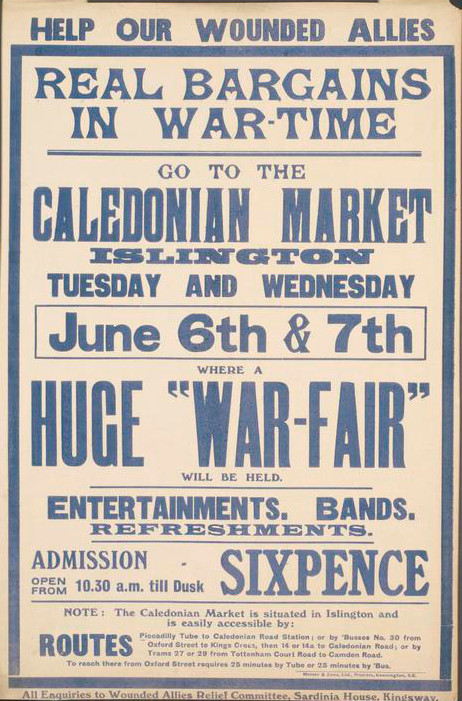

The Cally Market was also used during both the first and second world wars for major fund raising events. This poster from the first world war:

© IWM (Art.IWM PST 10955)

Along with the murals, my father took a photo of the Clock Tower in 1986. The original housing blocks that reached up to the clock tower can be seen on either side. The clock tower is surrounded by concrete paving.

This is the same scene in 2015 from roughly the same point (although I should have been more to the left). The old housing blocks have been demolished and the clock tower is now surrounded by green space.

Looking at the above photo, the wooden steps that provide the route up inside the Clock Tower can be seen through the two windows.

Join me for tomorrow’s post as I climb the tower to the viewing gallery at the top for some of the best views across London.