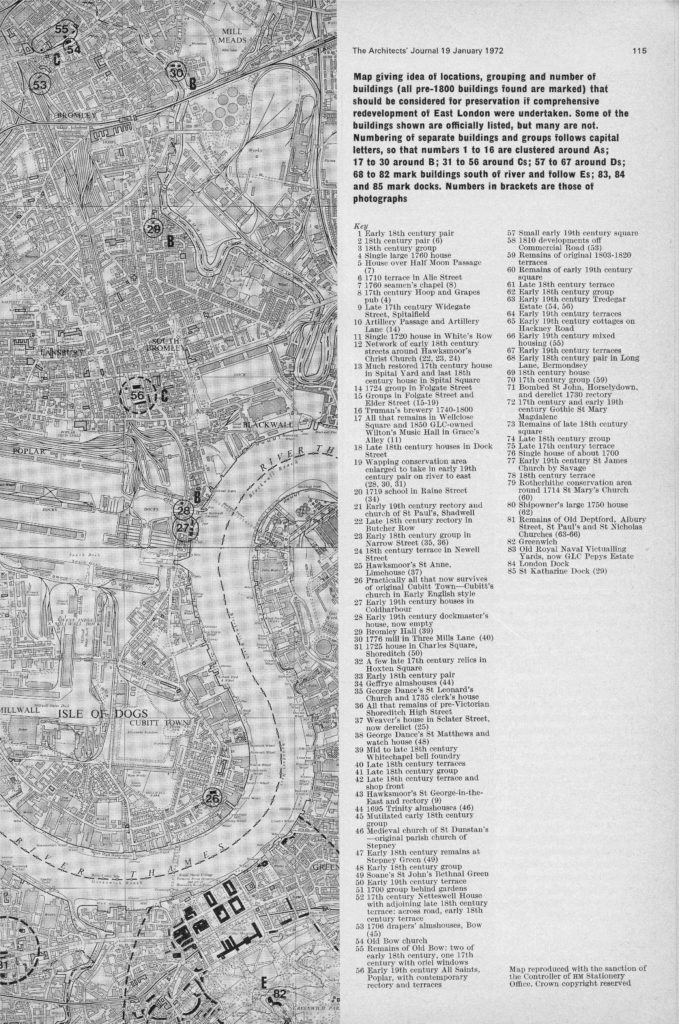

Two years ago I started a project to revisit all the locations listed as at risk in an issue of the Architects Journal. dated 19th January 1972. This issue had a lengthy, special feature titled “New Deal For East London”. The full background to the article is covered in my first post on the subject here.

I have almost completed the task of visiting all 85 locations, there are just a few more to complete. I had a day off work last Monday, the weather was perfect, so I took a walk from Bromley by Bow to the southern tip of the Isle of Dogs to track down another set of locations featured in the 1972 article, and also to explore an area, the first part of which, is not usually high up on the list for a London walk.

There was so much of interest on this walk, that I have divided into two posts. Bromley by Bow to Poplar today, and Poplar to the tip of the Isle of Dogs, hopefully mid-week.

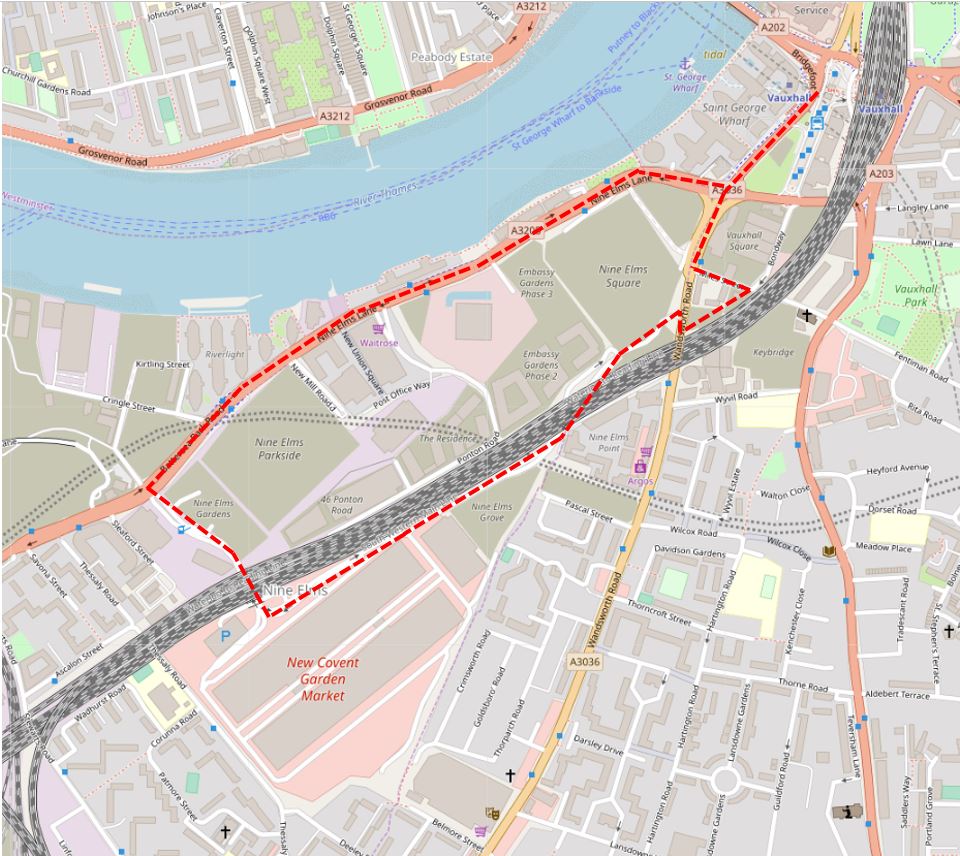

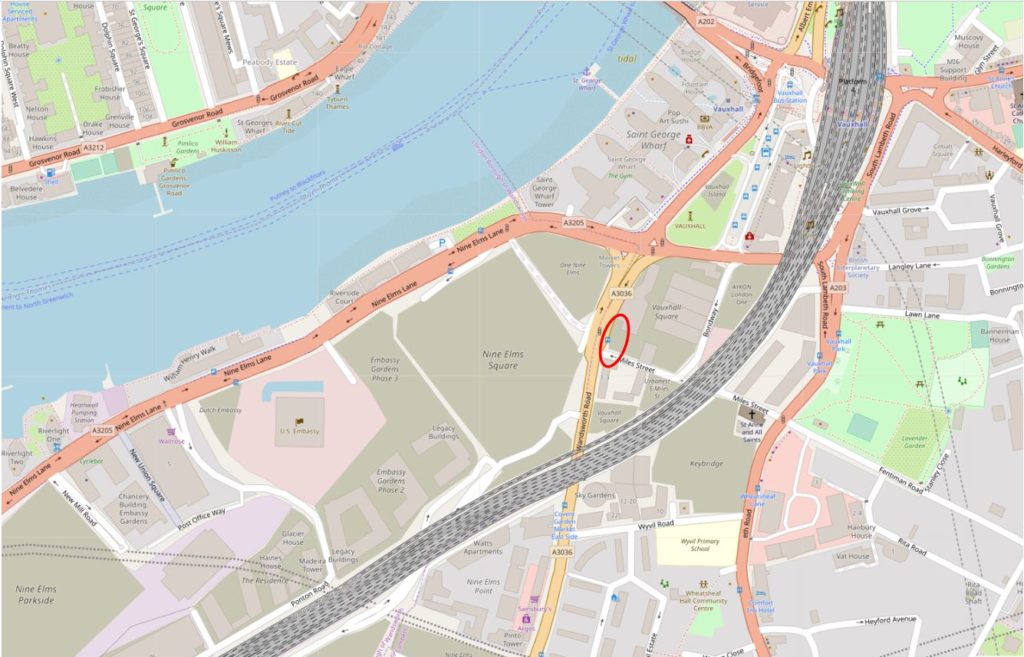

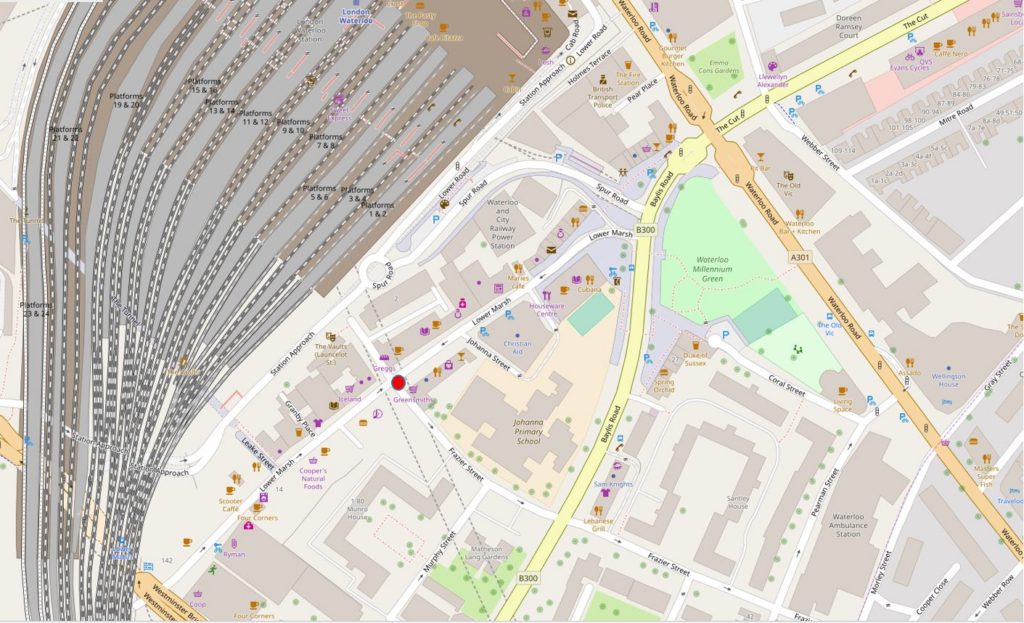

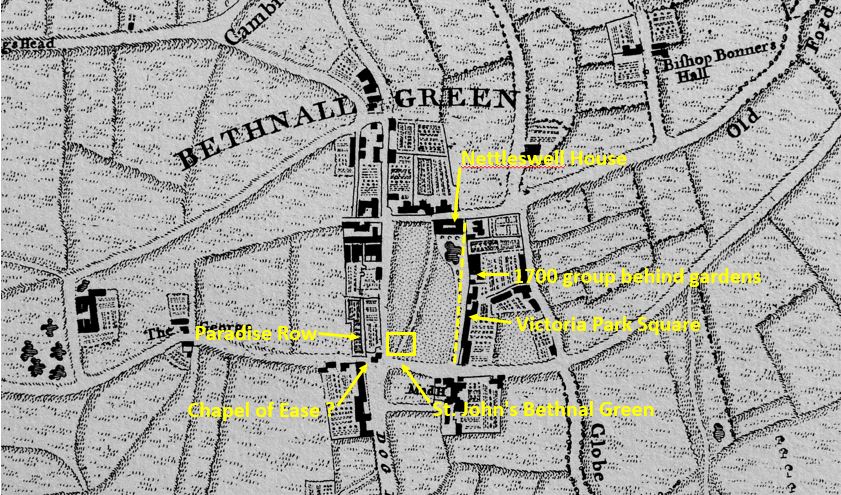

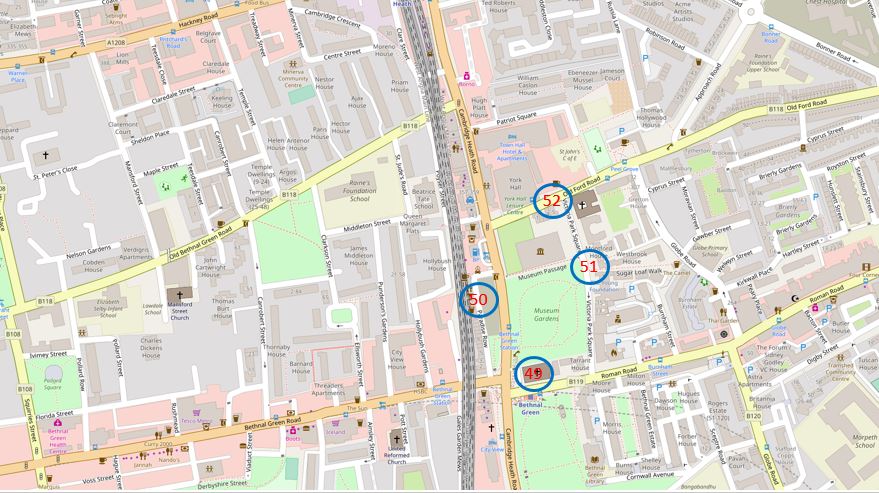

I had five sites to visit, which are shown in the following map from the 1972 article, starting at location number 29, passing by sites 56, 28 and 27 before finishing at site 26.

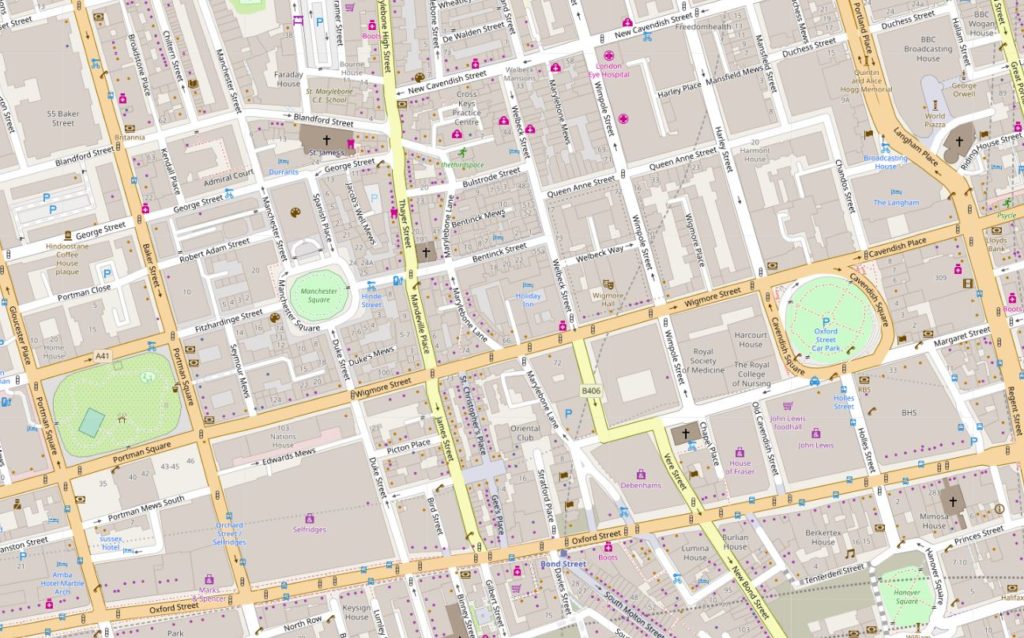

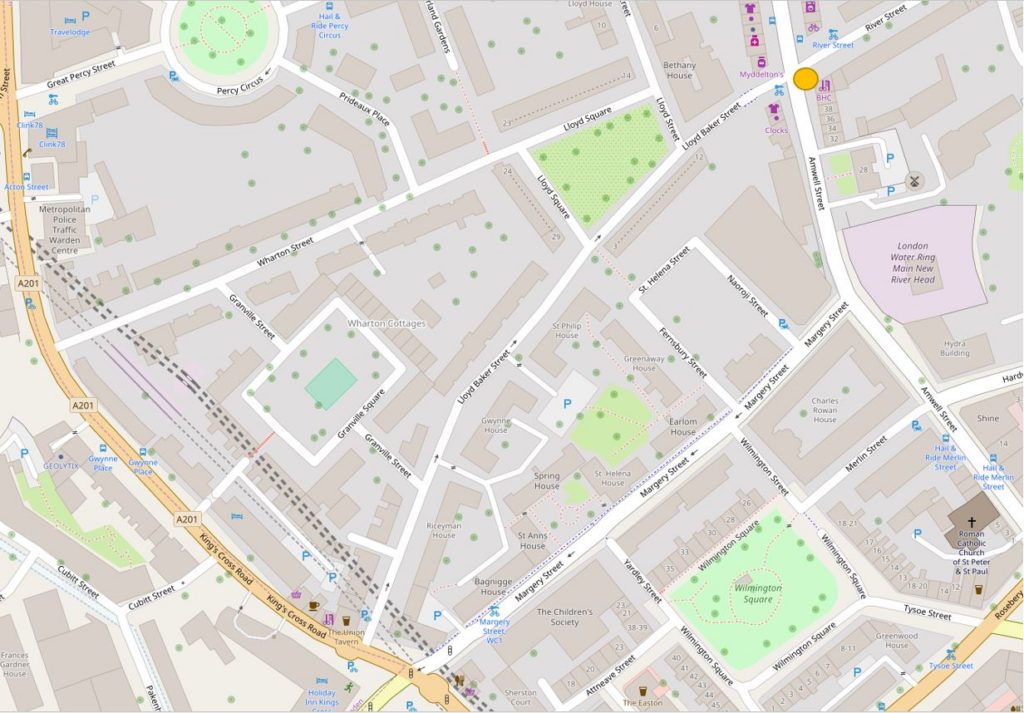

To get to the start of my planned route, I took the Hammersmith & City line out to Bromley by Bow station. There have been some considerable changes to the area in the years since the 1972 article, changes which are still ongoing. The following map shows the area today with the five locations marked. One obvious difference between the 1972 and 2019 maps are the major roads that have been cut through the original streets, and it is by one of these new roads that I would start the walk.

Map © OpenStreetMap contributors.

The entrance to Bromley by Bow underground station has been a building site for the last few years, although with not too much evidence of building work underway. The exterior of the station entrance is clad in hoardings and scaffolding.

The underground station entrance opens out onto a busy road. Three lanes of traffic either side of a central barrier. This is the A12 which leads from the Bow Flyover junction with the A11 and takes traffic down to the junction with the A13 and the Blackwall Tunnel under the River Thames.

Directly opposite the station is a derelict building. This, along with surrounding land has been acquired by a development company ready for the construction of a whole new, mainly residential area, including a 26 storey tower block.

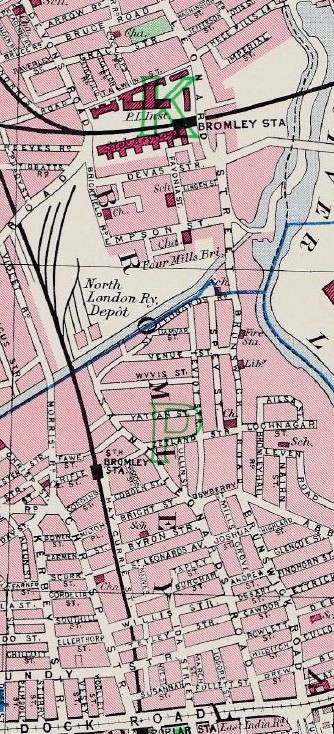

In the photo above, i am looking across the 6 lanes and central barrier of the A12. The construction of this road in the 1970s had a major impact on the area. It was once a network of smaller streets, terrace housing and industry, much of which was due to the location adjacent to the River Lea. The following extract from the 1940 Bartholomew’s Reference Atlas of Greater London shows a very different area. Bromley Station (now Bromley by Bow) is towards the top of the map with St. Leonard’s Street passing the station, leading down to Brunswick Road. Parts of these streets remain, however as the north to south route they have been replaced by the six lane A12. Many of the side streets have also disappeared or been shortened.

There are still many traces that can be found of the original streets and the buildings that the local population would have frequented. This photo is of the old Queen Victoria pub at 179 St Leonard’s Street.

The pub is surrounded by the new buildings of Bow School, however originally to the side of the pub and at the back were large terraces of flats which presumably provided a large part of the customers for the Queen Victoria. The pub closed in 2001 and is presumably now residential.

Walking further along the road, the road crosses the Limehouse Cut, built during the late 1760s and early 1770s to provide a direct route between the River Thames to the west of the Isle of Dogs loop and the River Lea.

New build and converted residential buildings have been gradually working their way along the Limehouse Cut, however there are a few survivors from the light industrial use of the area, including this building where the Limehouse Cut passes underneath the A12.

A short distance along is another old London County Council Fire Brigade Station for my collection. This was built in 1910, but has since been converted into flats.

The building is Grade II listed, with the Historic England listing stating that the building “is listed as one of London’s top rank early-C20 fire stations“. The building originally faced directly onto Brunwsick Road and was known as Brunswick Road Fire Station, however with the A12 cutting through the area, the small loop of the original Brunswick Road that separates the fire station from the A12 has been renamed Gillender Street.

The short distance on from the fire station is the first of the Architects Journal sites on my list:

Site 29 – Bromley Hall

The view approaching Bromley Hall:

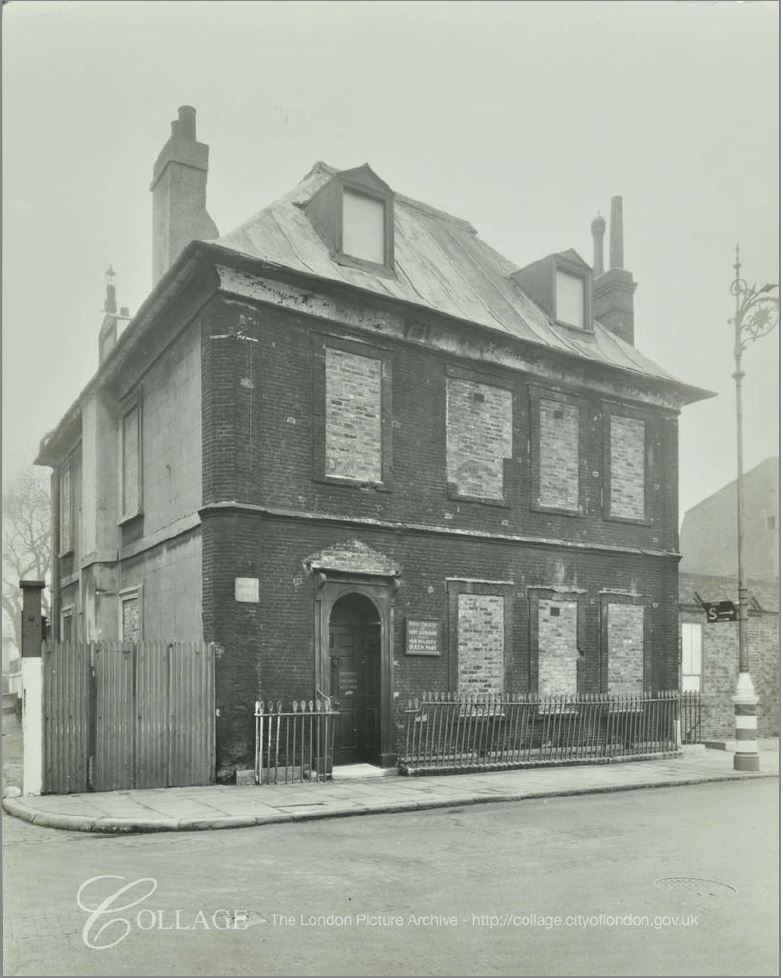

For an area that has been through so much pre and post war development, the original industrialisation of the area and wartime bombing, it is remarkable that Bromley Hall has survived.

Although having been through many changes, the building can trace its origins back to the end of the 15th century when it was built as a Manor House, later becoming a Tudor Royal Hunting Lodge. The site is much older as it was originally occupied by the late 12th century Lower Brambeley Hall, and parts of this earlier building have been exposed and are on display through a glass floor in the building.

The London Metropolitan Archives, Collage site has a few photos of Bromley Hall. The first dates from 1968 and shows the hall, apparently in good condition, but surrounded by the industry that grew up along the River Lea.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01 288 68 5683

The photo highlights the impact that the A12 has had in the area. The above photo was taken from Venue Street, a street that still remains, but in a much shorter form. Everything in the above photo, in front of Bromley Hall, is now occupied by the six lane A12.

An earlier photo from 1943 showing Bromley Hall. The windows have been bricked up, I assume either because of loss of glass due to bombing, or as protection for the building.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_288_F1262

Bromley Hall is Grade II listed and has been open during Open House London weekends and is well worth a visit.

Further along is another example that this area, now isolated across the A12 was once a thriving community. This imposing facade is of Bromley Library, built between 1904 and 1906.

Bromley Library was one of four libraries in Poplar. The others being Poplar Library in the High Street, Cubitt Town Library in Strattondale Street and Bow Library in Roman Road. These libraries were open from 9 in the morning till 9:30 in the evening, and in 1926 almost half a million books were issued across the four libraries.

Bromley Library was one of four libraries in Poplar. The others being Poplar Library in the High Street, Cubitt Town Library in Strattondale Street and Bow Library in Roman Road. These libraries were open from 9 in the morning till 9:30 in the evening, and in 1926 almost half a million books were issued across the four libraries.

The Bromley Library building is now Grade II listed. It closed in 1981 and after standing empty for many years, the old library building has been converted into small business units.

I walked on a bit further, then took a photo looking back up the A12 to show the width of the road.

Bromley Hall is the building with the white side wall to camera, and the library is just to the left of the new, taller building.

There is a constant stream of traffic along this busy road, when I took this photo it was during one of the occasional gaps in traffic when a pedestrian crossing just behind me was at red. There are not too many points to cross the road, with crossings consisting of occasional pedestrian traffic lights and also a couple of pedestrian underpass.

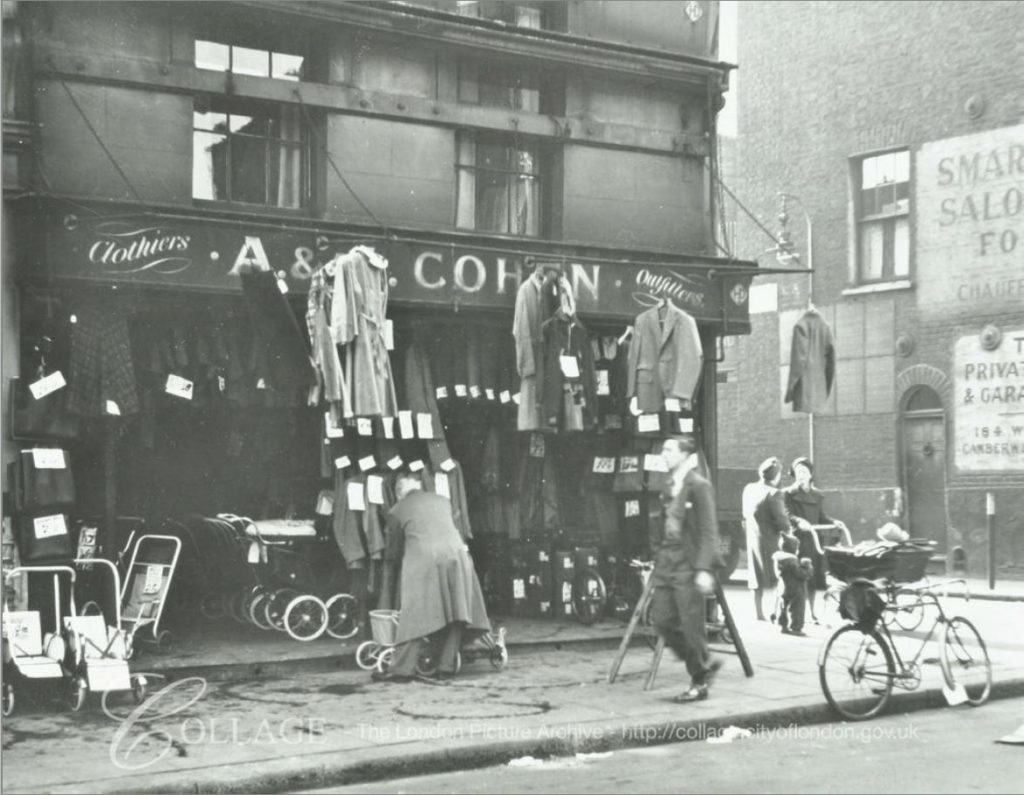

Much of this lower part of the A12 widening between the Limehouse Cut and East India Dock Road was originally Brunswick Street. The following Collage photo from 1963 shows Brunswick Street before all this would be swept away in the 1970s for the road between the Bow Flyover and the Blackwall Tunnel.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_288_AV63_989

Before the road meets the East India Dock Road, there are additional lanes to take traffic under the A12 and across to Abbott Road to the east.

Close to the junction between the A12 and the East India Dock Road is the Balfron Tower.

A whole post could be written about Balfron Tower, the flats design by Erno Goldfinger and built in 1967. Balfron Tower tends to generate either love it or loathe it views of the building. dependent on your appreciation of high-rise accommodation and concrete construction.

The recent past has also been controversial in the history of the building. Like many estates from the 1960s, Balfron Tower suffered from lack of maintenance, failing lifts, problems with plumping and anti-social behavior.

In 2007 the building was transferred from Tower Hamlets Council to the housing association Poplar HARCA. The transfer included a commitment for refurbishment of the building which required considerable work and cost.

Tenants were initially given the option to remain whilst refurbishment was carried out, or move to a new local property. Whilst a number of residents took up the option to move, a number of residents remained.

The remaining residents were moved out in 2010, the reason given being the difficulty of managing a significant refurbishment project along with health and safety issues whilst there are residents in the building. Initially there was an indication that the residents may have a right of return, however this option disappeared as work progressed, and the costs of building works grew.

The redevelopment work is being undertaken by a joint venture including Poplar HARCA, LondonNewcastle and Telford Homes. There will not be any social housing in the refurbished building and all flats will be sold at market rates.

A long hoarding separates the building from the A12 with artist impressions of the new Balfron Tower and the address of the website where you can register your general interest, or as a potential purchaser of one of the flats.

Balfron Tower photographed in February 2019, clad for building work.

A couple of years ago, I climbed the clock tower at Chrisp Street Market and photographed Balfron Tower:

This is a development that will continue to be controversial due to the lack of any social housing and the sale of the flats at market rates. Another example of the gradual demographic change of east London.

To reach my next destination on the Architects’ Journal list, I turn into East India Dock Road. A terrace of 19th century buildings with ground floor shops runs along the north of the street and above Charlie’s Barbers there is an interesting sign:

Interesting to have this reference to a north London club in east London. I put this photo on Twitter with a question as to the meaning and one possible reference is the boring way Arsenal use to play and results would only ever be one nil. I would have asked Charlie, if he still owns the barbers, however they were shut during my visit.

A short distance from Charlies Barbers and across the East India Dock Road was my next location.

Site 56 – Early 19th Century All Saints, Poplar, With Contemporary Rectory And Terraces

Buildings seem to have a habit of surrounding themselves in scaffolding whenever I visit and All Saints, Poplar was certainly doing its best to hide, however it still looks a magnificent church on a sunny February morning.

Poplar was originally a small hamlet, however the growth of the docks generated a rapid growth in population. The East India Dock Road was built between 1806 and 1812 to provide a transport route between the City and the newly built East India Docks.

Alongside the East India Dock Road, All Saints was constructed in the 1820s by the builder Thomas Morris who was awarded the contract in 1821.

The church survived the bombing of the docks during the last war until March 1945 when a V2 rocket landed in Bazely Street alongside the eastern boundary of the churchyard, causing considerable damage to the east of the church.

The church was designed to be seen as a local landmark along the East India Dock Road and across the local docks. The spire of the church is 190 feet high and the white Portland stone facing would have impressed those passing along the major route between City and Docks.

Burials in the churchyard ended in the 19th century and the gravestones have been moved to the edge, lining the metal fencing along the boundary of the church.

The area around the church was developed during the same years as construction of the church. A couple of streets around the church now form a conservation area. These were not houses built for dock workers. Their location in the streets facing onto the church would be for those with a substantial regular income, rather than those working day-to-day in the docks.

This is Montague Place where there are eight surviving terrace houses from the 1820s.

At the eastern end of Montague Place there is another terrace of four houses in Bazely Street. These date from 1845 and are in remarkably good condition.

The church and two terraces of houses form a listed group and are part of a single conservation area.

A short distance further down Bazely Street is one of my favourite pubs in the area – the Greenwich Pensioner. The pub closed for a few years recently but has fortunately reopened.

One of the problems of walking in the morning – the pubs are still closed.

I continued along Bazely Street to Poplar High Street, then turned south to the large roundabout where Cotton Street (the A1206) meets the multi-lane Aspen Way. This is not really a pedestrian friendly area, however I needed to cross under the Aspen Way to continue heading south for my next destination.

This photo looking towards the east, is from the roundabout underneath the flyover that takes the Aspen Way on its way to the Lower Lea Crossing.

As with the A12 along Bromley by Bow, this area has been cut through with some major new multi-lane roads as part of the redevelopment of the docks.

A poster seen underneath the flyover alongside the roundabout.

A poster that is relevant to a specific point in time. I was not sure who would see the poster as it is facing inwards, away from the traffic on the roundabout, and I doubt that many pedestrians take this route.

Emerging from underneath the flyover and the developments on the northern edge of the Isle of Dogs can be seen.

Crossing over Trafalgar Way, and one of the old docks can be found. This is Poplar Dock looking west with two cranes remaining from when the dock was operational.

The site is now Poplar Dock Marina and is full with narrow boats and an assorted range of other smaller craft. Poplar Dock opened in 1851, however the site had originally been used from 1827 as a reservoir to balance water levels in the main West India Dock just to the west. In the 1840s the area was used as a timber pond before conversion to a dock.

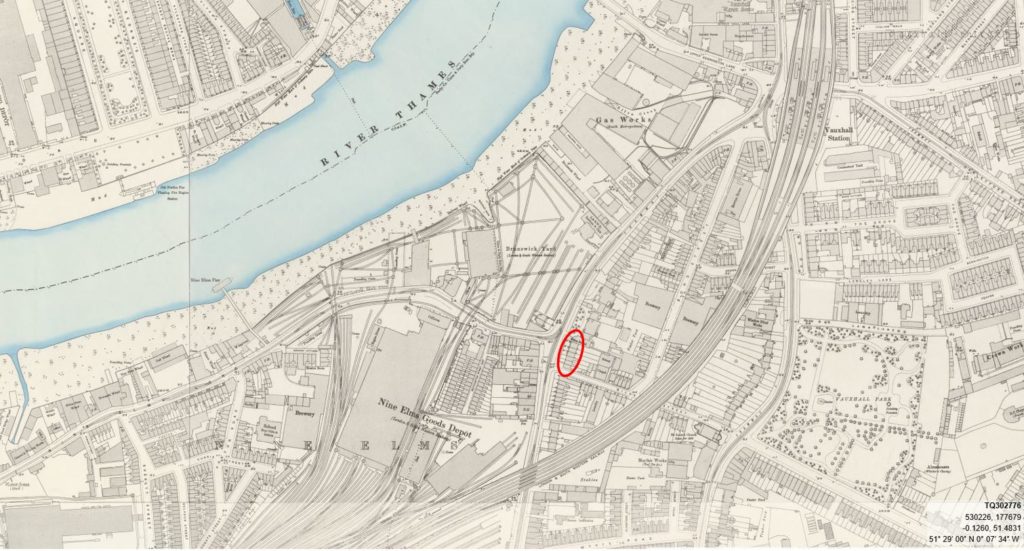

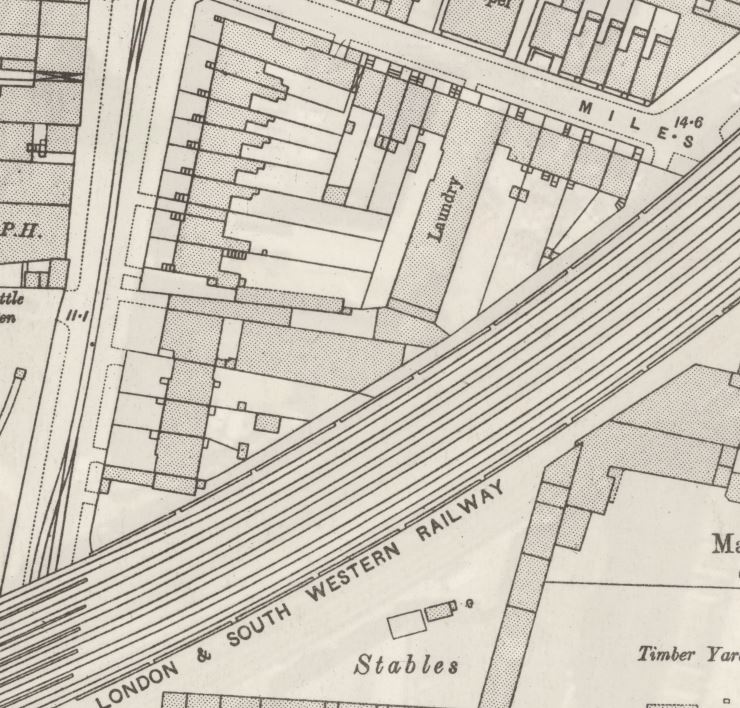

Poplar Docks served a specific purpose, being known as a railway dock. The following extract from the 1895 Ordnance Survey map shows Poplar Docks almost fully ringed by railway tracks and depots of the railway companies.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

Again, the docks deserve far more attention than I can give in this post, so for now, I will leave Poplar Docks at their southern end and walk along Preston’s Road to get to my next location on the Architects’ Journal list.

Site 28 – Early 19th Century Dockmaster’s House, Now Empty

Those last two words must have been the reason for inclusion in the list. An empty building in the docklands in the 1970s would have been at risk, however fortunately the building has survived and this is the view when approaching the location along Preston’s Road.

The Dockmaster’s House goes by the name of Bridge House and is now occupied by apartments available for short term rent.

The house is alongside the Blackwall entrance to the docks, a channel that connects the River Thames to the Blackwall Basin so would have seen all the shipping entering from the river, heading via the basin to and from the West India Dock.

Evidence of the historic function of the place can be found hidden in the gardens between the house and the channel.

Bridge House was built between 1819 and 1820 for the West India Dock Company’s Principal Dockmaster. The entrance to the house faces to the channel running between docks and river, however if you look at the first photo of Bridge House taken from Preston’s Road you will see large bay windows facing out towards the river. This was a deliberate part of the design by John Rennie as these windows, along with the house being on raised ground would provide a perfect view towards the river and the shipping about to enter or leave the docks.

The Architects’ Journal in January 1972 were right to be worried about the future of Bridge House. Later that same year a fire destroyed the roof. The rest of the house survived and a flat roof was put in place.

The house was converted to flats in 1987 and a new roof to the same design as the original replaced the flat roof. The luxury flats did not sell, and Bridge House has hosted a number of temporary office roles before apparently now providing a short term let for flats which have been constructed inside the building.

The view from in front of the house. This side of the house is facing down to the channel that leads from the Thames to the Blackwall Basin.

A view from the bridge over the channel showing the house in its raised position, overlooking the channel and to the right, the River Thames (although that view is now obstructed by buildings).

Before continuing on down through the Isle of Dogs in my next post, I will pause here on the bridge over the channel between docks and river to enjoy the view.

This is looking west towards the original Blackwall Basin:

This is looking east, the opposite direction towards the river with the Millennium Dome partly visible across the river.

I really enjoyed this part of the walk, what could be considered an unattractive route, walking down from Bromley by Bow station is completely wrong. It is an area going through considerable change but there is so much history and so much to explore.

In my next post I will continue walking south towards the far end of the Isle of Dogs to find the remaining two locations from the 1972 issue of the Architects’ Journal.