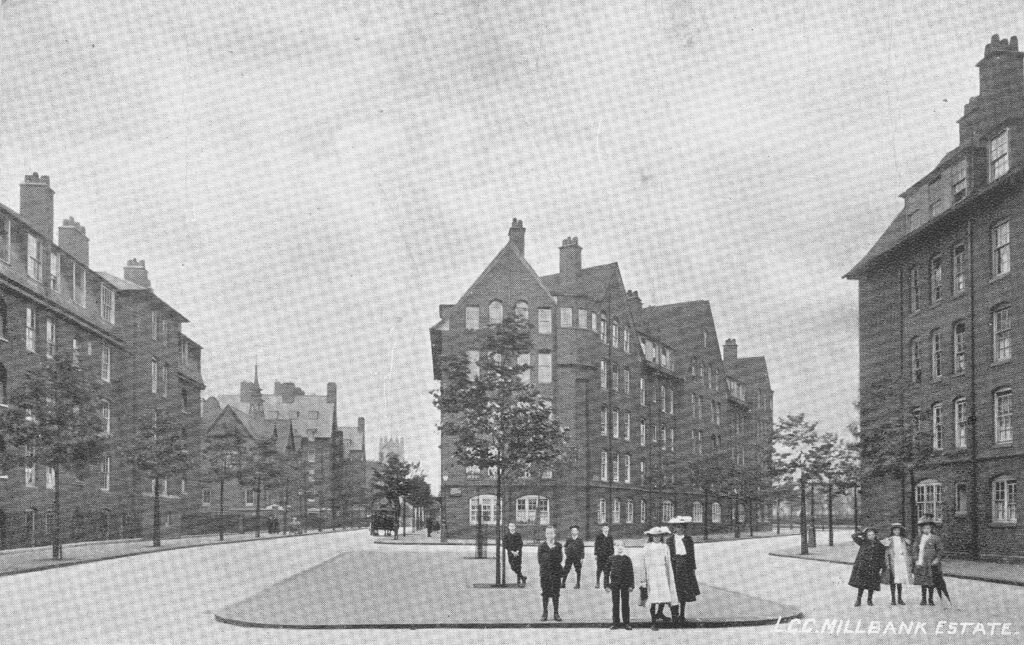

I have a postcard with a photo dated 1906 of the recently completed London County Council, Millbank Estate. The view shows some of the new blocks of flats, wide streets, newly planted trees, and children – probably residents of the new estate.

The same view in September 2020:

The trees have grown and now obscure the view of the blocks of flats. The wide streets now have parked cars, and the children in the view went on to see and hopefully survive, two world wars.

Remove the cars, see through the trees and the two views are much the same.

Both photos were taken at the south western end of the estate, looking north east. The street in front of the camera is Cureton Street and Erasmus Street is on the left and Herrick Street on the right.

The Millbank Estate is a large estate, built at the start of the 20th century, to provide flats for the working class. The estate was designed to accommodate upwards of 4,430 people in a number of separate blocks.

A map of the estate is displayed on a number of panels across the estate:

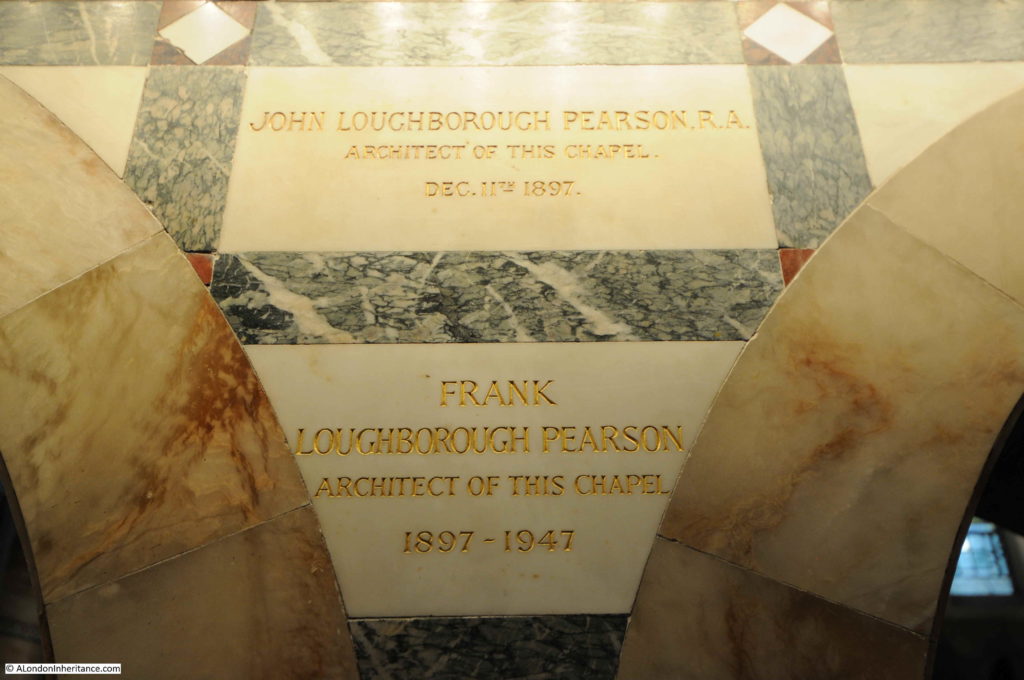

The Millbank Estate is adjacent to the Tate Britain gallery which was opened a couple of years before work started on the Millbank Estate, and the artistic theme of the Tate was extended to the new housing estate as each of the blocks was named after an artist. The full list of names is shown on the lower right of the above panel.

The Millbank Estate was built between 1897 and 1902 by the London County Council and was one of their most significant estates in terms of size and design. It was designed within the LCC’s Architects Department under Owen Fleming and was influenced by the arts and crafts style of design.

The estate is stunning on a sunny day, when the colour of the brick brings a richness to the buildings. The trees – which I assume from their size were planted at the time of the estate’s construction – break up the sunlight and leave patterns on the walls of the blocks.

The trees are regularly pollarded, when their branches are cut back significantly leaving stumps pointing at the sky, but they always grow back and enhance the view.

The view along St Oswulf Street with Hogarth House at the end of the street:

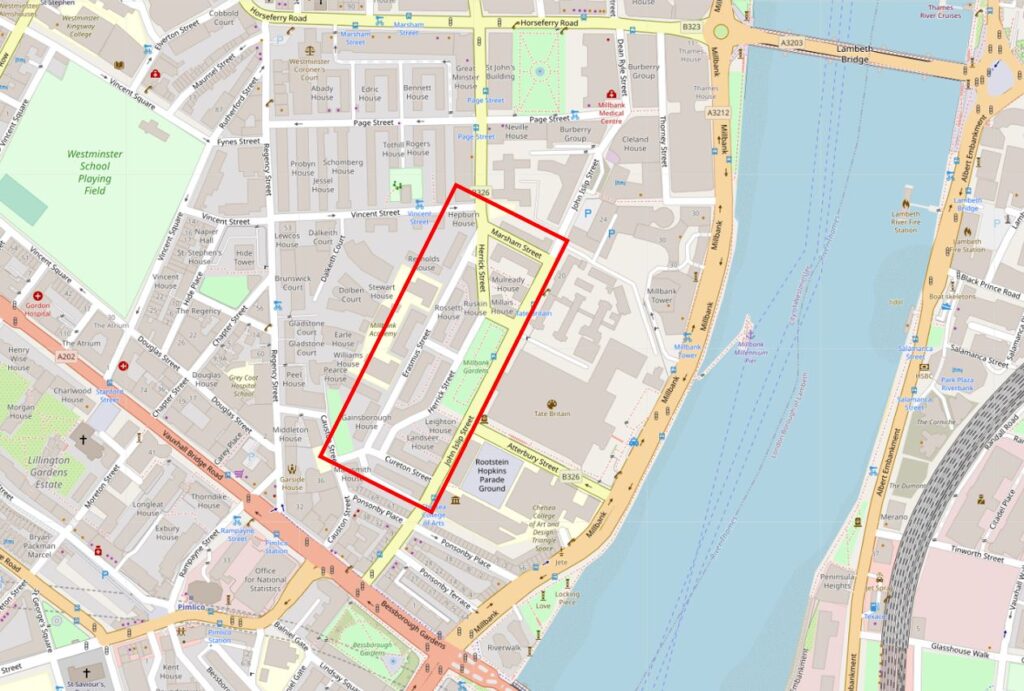

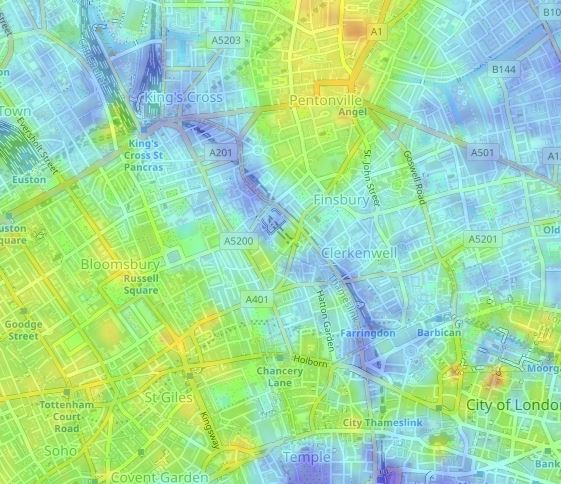

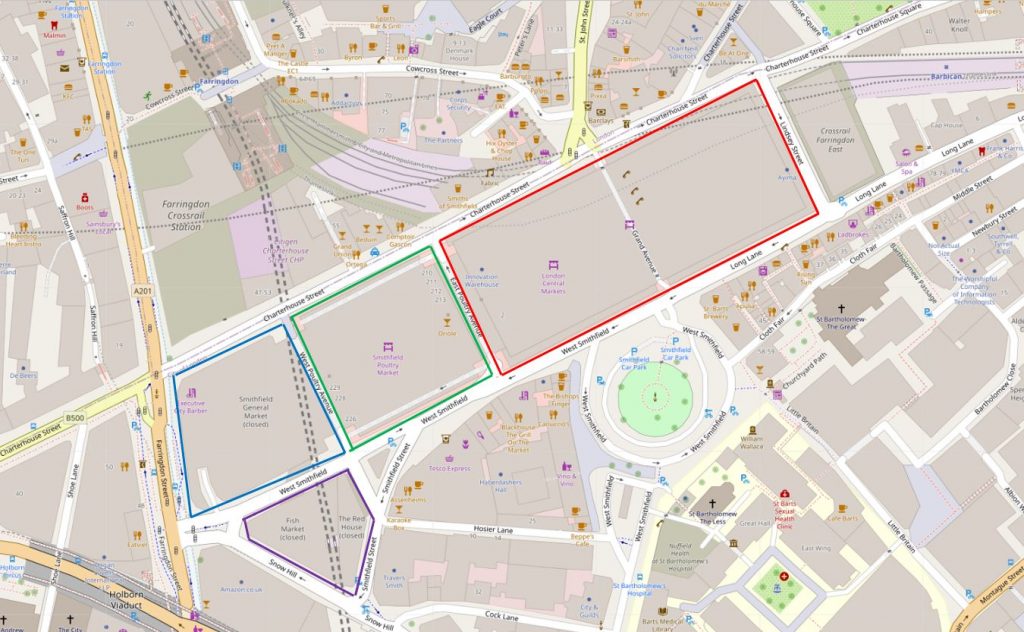

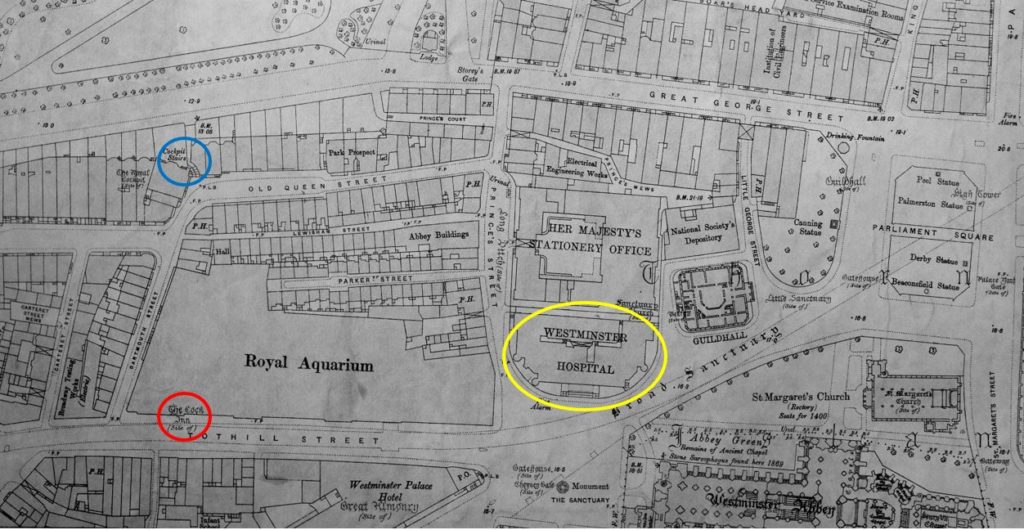

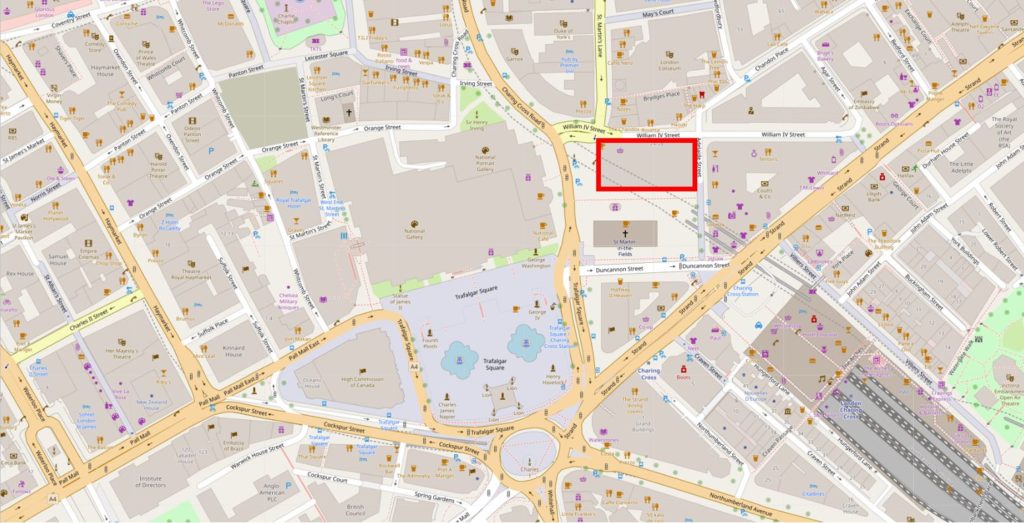

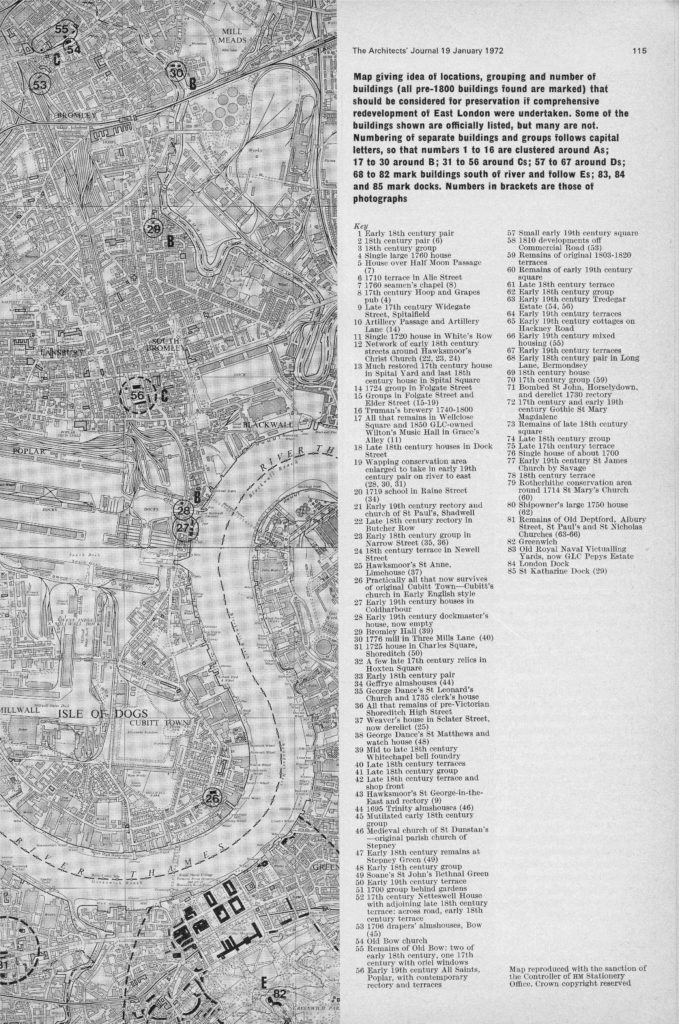

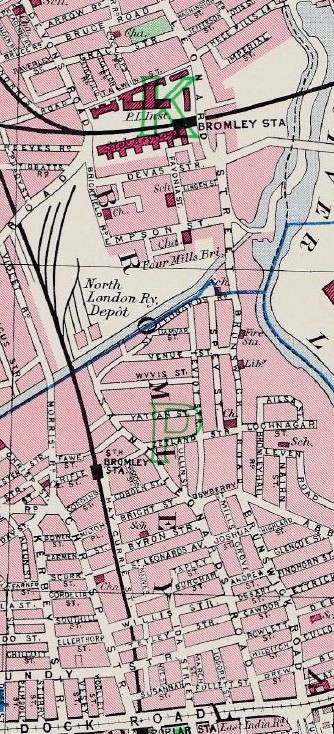

The area occupied by the Millbank Estate has a fascinating history. On land to the west of the River Thames, between Lambeth and Vauxhall Bridges, it was a large area to be free for building at the end of the 19th century. In the map below, the red rectangle shows the approximate area occupied by the estate (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

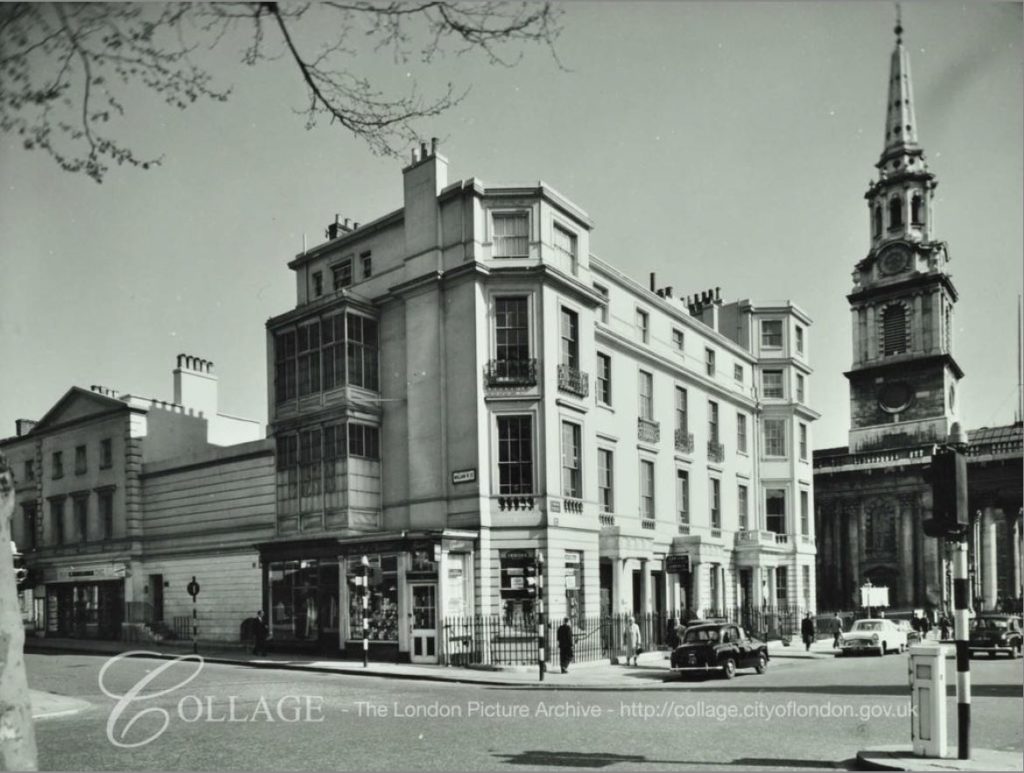

The area occupied by the Millbank estate, and indeed the Tate Gallery was available for new development because of the demolition of a large establishment that had previously the same space.

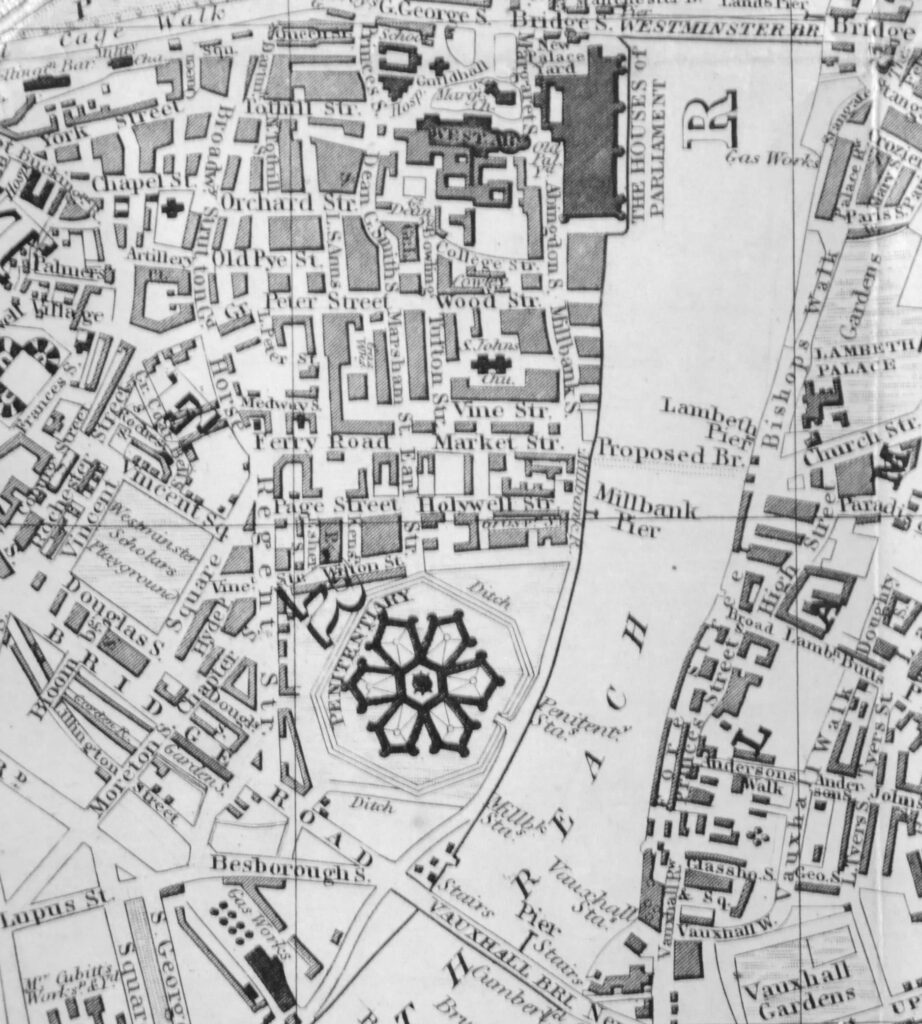

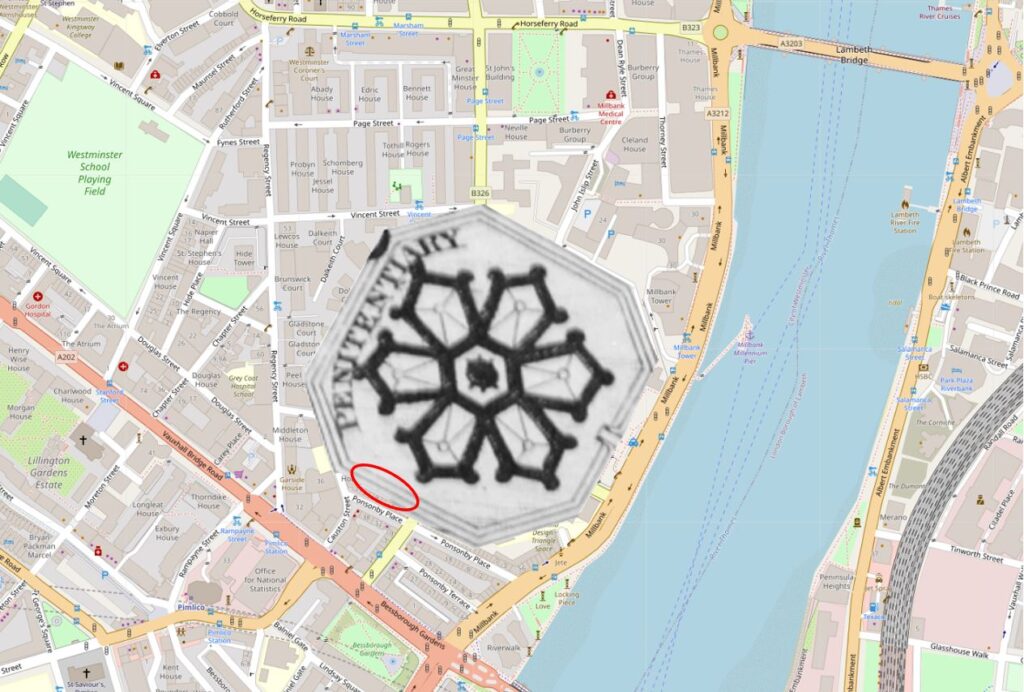

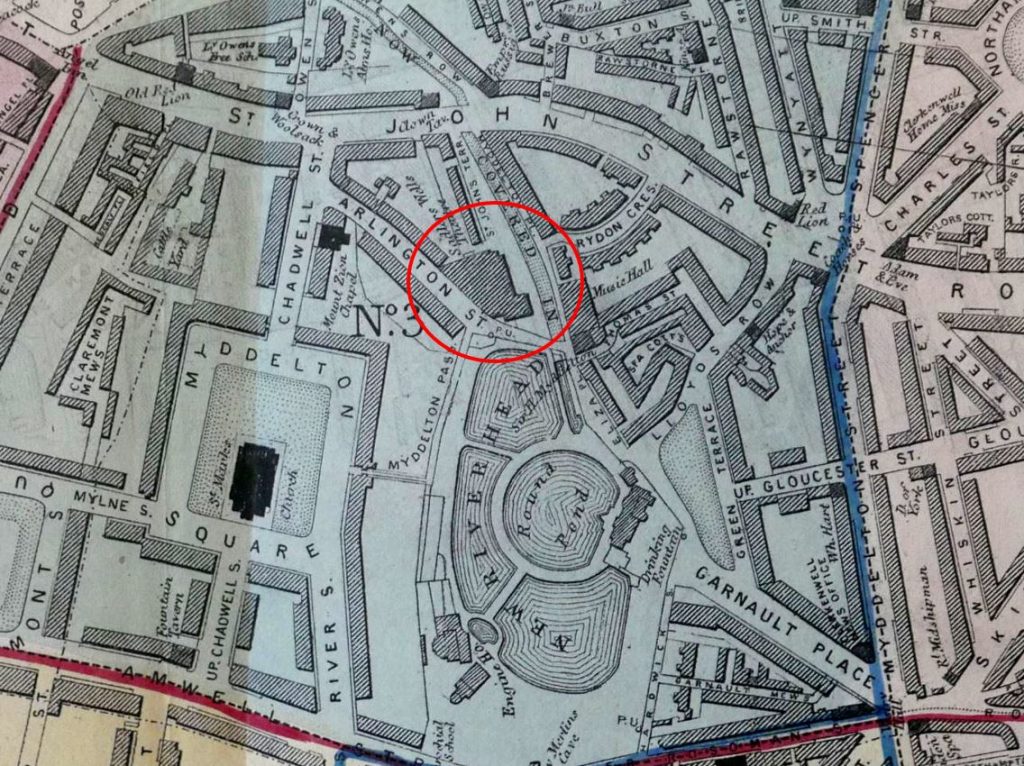

In the following extract from the 1847 edition of Reynolds’s New Map of London, there is a structure with a rather unusual design in the lower centre of the map. This was the Millbank Penitentiary or Prison.

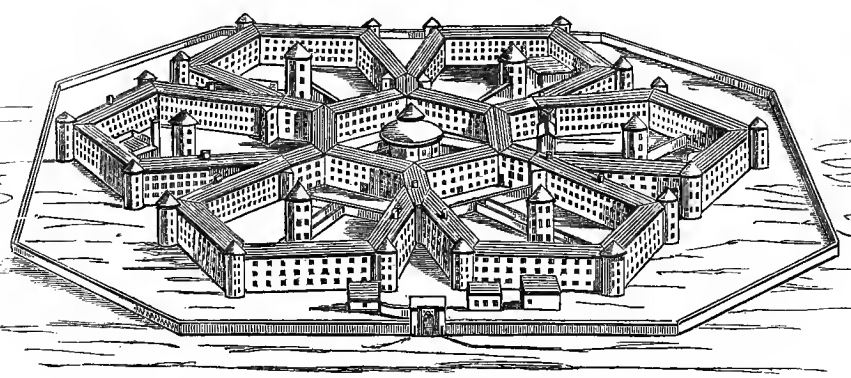

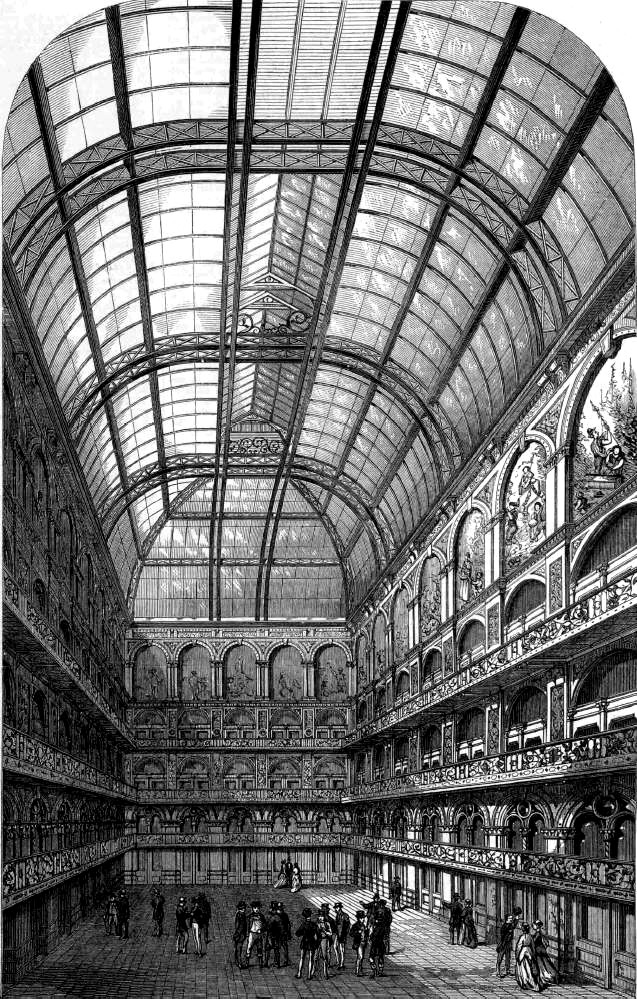

Millbank Penitentiary opened in 1816 and was in use until 1886, and was demolished by 1890. The shape was unusual for the time, with six individual pentagons of cells radiating out from the central governor’s block.

The pentagon design enabled the whole of the prison to be viewed from the central governor’s block.

The prison was initially designed to hold 1,000 prisoners, however as always seems to be the way with prisons, the population was frequently much higher.

Each of the pentagons was home to different types of prisoner. Writing about the prisons of London in 1862, Henry Mayhew and John Binny identified pentagon one as being the reception wing. Number two being for prisoners to work at various trades in their cells. Pentagon three was for women prisoners. Pentagon four housed the infirmary, along with a mix of different prisoners. Number five had individual cells, but also had shared cells which prisoners often preferred for the company and conversation instead of the individual cells.

Mayhew and Binny do not list the functions of the sixth pentagon, but looking at the diagram of the prison in the book, the sixth pentagon was were you would find the surgeon and the chaplain, with a corn mill in the centre.

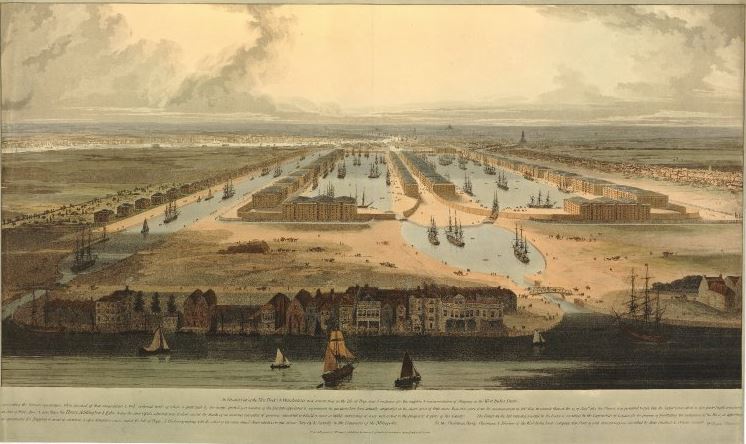

Birds-eye drawing of Millbank Penitentiary:

Millbank Penitentiary was often used as a holding prison before prisoners moved onto other establishments. This included a period where prisoners sentenced to transportation were held at Millbank before boarding ship.

Mayhew and Binny’s book states that in 1854, 2,461 male prisoners passed through Millbank.

Six hundred and ninety seven remained at the end of the year. During the year, prisoners had been moved to other prions. One thousand and ninety five prisoners had been moved to sites of “public works” projects across the country. Of the total number of prisoners passing through Millbank in 1854, only four were pardoned, had a conditional pardon, or were set free.

One hundred and ninety eight female prisoners were in Millbank at the start of 1854, but by the end of the year they had all been moved to Brixton Prison apart from nineteen who had been discharged and one who had died.

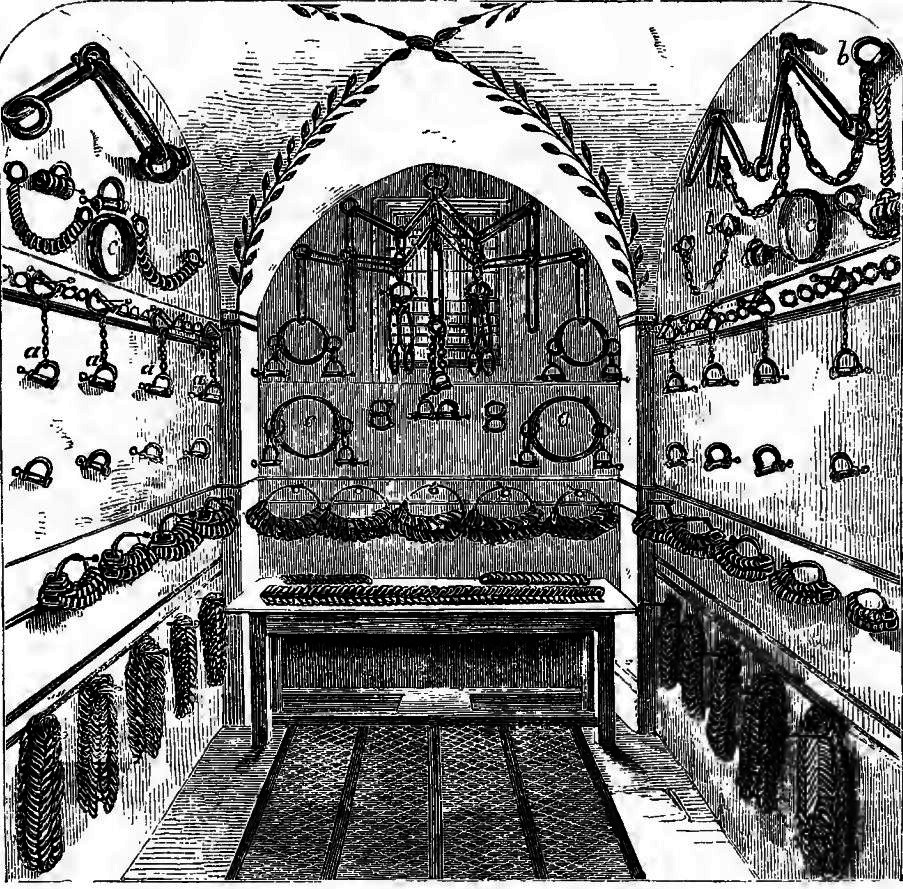

Conditions were harsh for the prisoners at Millbank. The location next to the River Thames must have meant the prison could be very cold and damp in winter. The prison also suffered a cholera outbreak. Prisoners would also be transported or held in irons, and the prison had a Chain Room where the implements to restrain prisoners were stored:

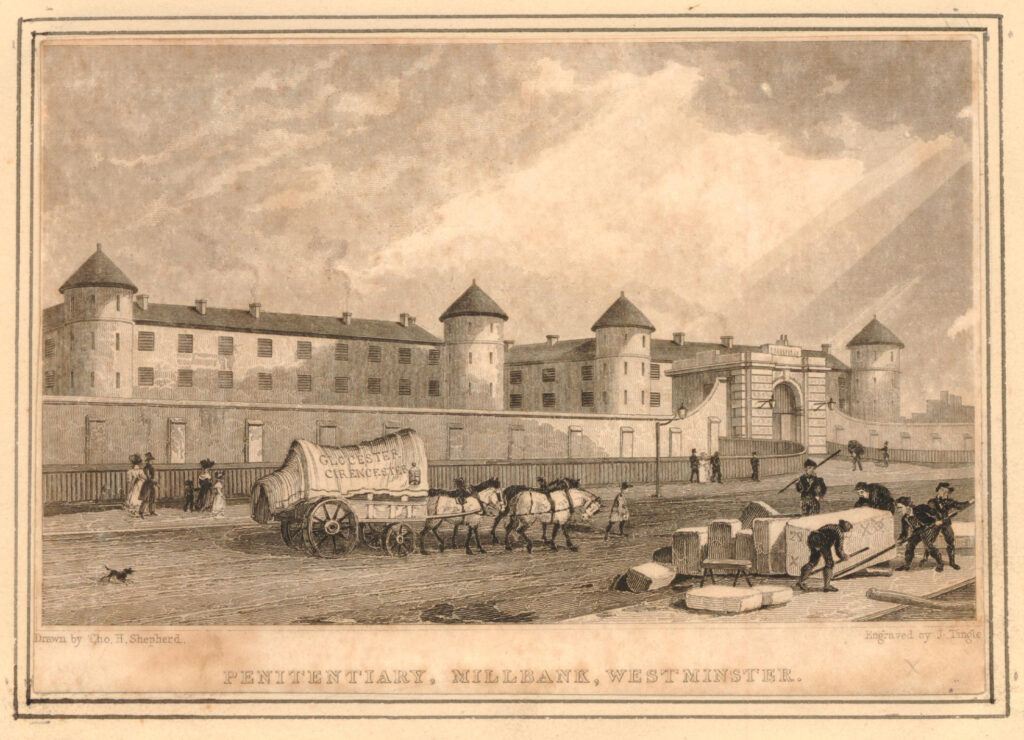

The following print shows the main entrance to the prison, with some of the prison wings behind the walls. This must have been drawn from the edge of the river, and shows the road running towards Westminster on the right, between prison and river.

I have mapped the location of Millbank Penitentiary on the map of the area today in the following map extract.

The Tate Gallery, Millbank Estate and a number of other buildings now occupy the site today, but does anything remain of the prison?

In the above map, I have added a red oval to the rear of the houses that face onto Ponsonby Place. This is the boarder with the south western edge of the Millbank Estate, and Wilkie House is the block that was built with the rear of the block facing the rear of the houses in Ponsonby Place.

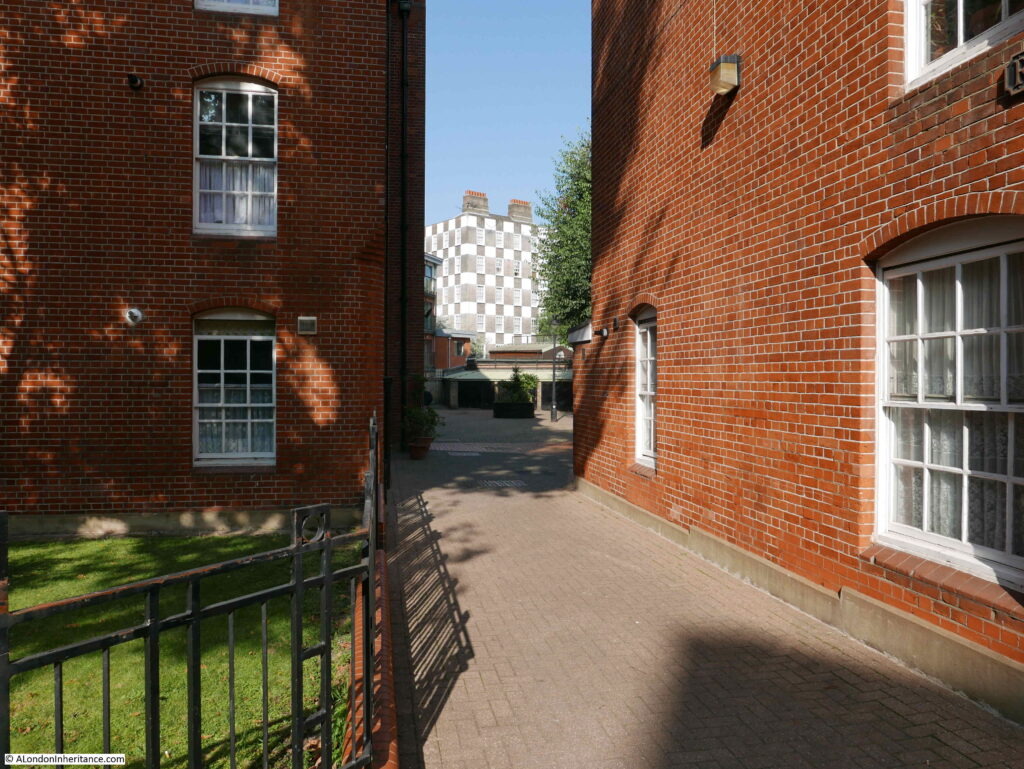

There is a gap between the rear of Wilkie House and the houses to the west as shown in the following photo:

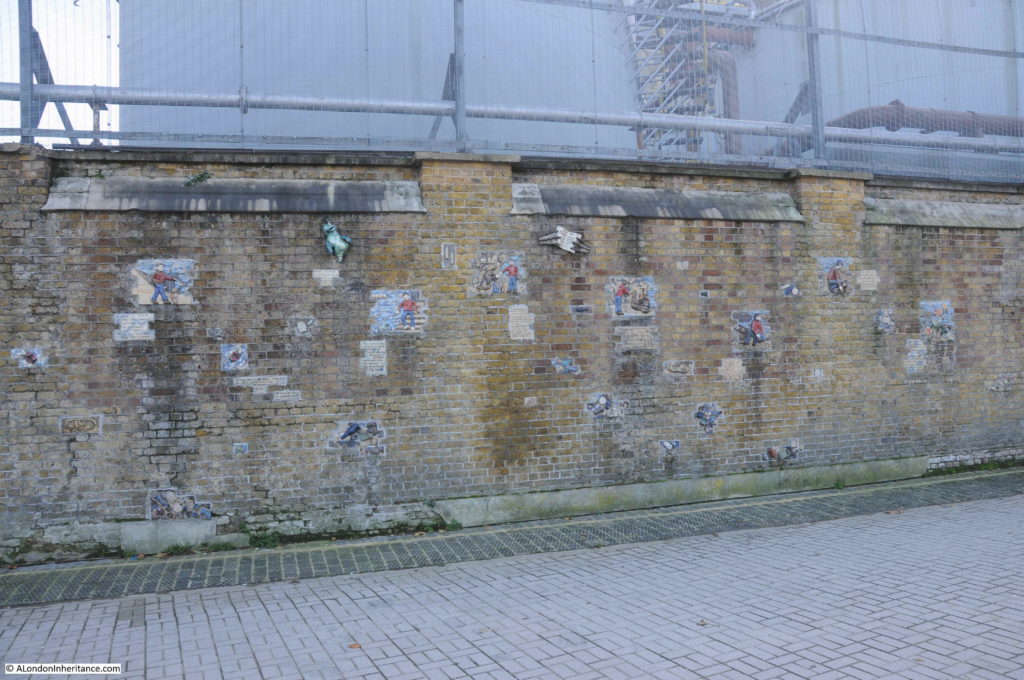

Look over the railings into the gap, and we can see the ditch and sloping wall of the original Millbank Penitentiary:

The City of Westminster Conservation Area Audit states about the ditch and wall:

“Of great importance is the octagonal shape of the former Millbank Penitentiary site, not only for its definition of the shape of the conservation area but also for the surviving sections of wall. This is an important historical and townscape characteristic of the area.”

The Millbank Penitentiary really deserves a dedicated post, so I will continue with my exploration of the Millbank Estate.

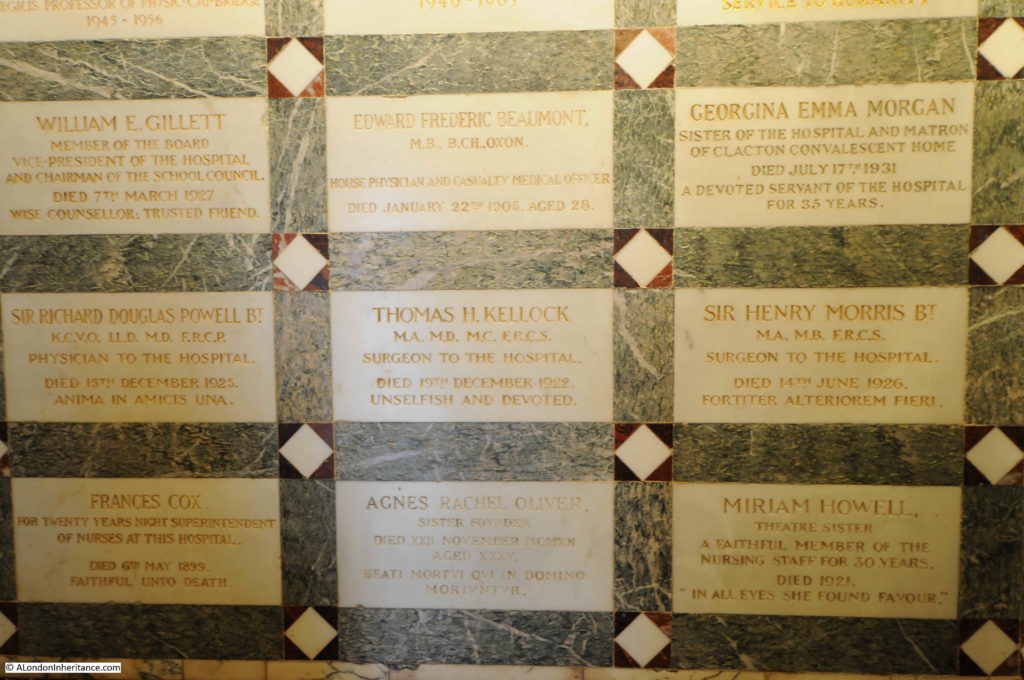

Families were a significant percentage of those living in the estate, so there was a need to provide schools for such a large estate and two were built at the same time as the housing blocks.

The two schools are both in Erasmus Street on the western side of the estate. The first one comes into view:

On the side of the first school is a rather ornate decoration stating Millbank Schools and the year of construction, 1901. In the centre are the initials LSB. These are not the initials of a person, rather the initials are of the London School Board who were responsible for the construction of the schools and it was their architects who produced the designs.

The fount of the first school facing onto Erasmus Street:

Further along is the infant school, also by the London School Board:

Plaque confirming this building as the infants school:

There are entrances and playgrounds at each side of the school building. A stone arch with the word “infants” provides access:

The reason for the two schools becomes apparent as you walk around the estate and realise the size, number of flats and how many children must have lived across the estate.

Between the main blocks of flats there are large courtyards, providing a very child friendly play area:

The blocks are not a monolithic design, they have plenty of individual features which break up the brick. In this view, staggered windows provide light to internal stairs:

Despite the large scale of the estate, there are small features dotted across the blocks, such as this small corner window:

Following photo shows the view looking up the central part of Hogarth House, with a curving, triangular roof line, and long balcony:

The Millbank Estate is Grade II listed, however Hogarth House has a higher Grade II* listing. It was the first block to be started in 1899 and the design of Hogarth House by the architects Henry Spalding and Alfred Cross was the winning design in the competition run by the London County Council Architects Department for the design of the estate.

The Millbank Estate is Grade II listed, however Hogarth House has a higher Grade II* listing. It was the first block to be started in 1899 and the design of Hogarth House by the architects Henry Spalding and Alfred Cross was the winning design in the competition run by the London County Council Architects Department for the design of the estate.

A living room in Hogarth House was photographed in 1909, not long after the building opened.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0832_70_1063

Being almost 120 years old, the Millbank Estate has been through a number of renovations. The condition of the flats had deteriorated by the late 1940s, and there were renovations throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The following photo shows a living room in Millais House in 1962.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0832_62_1623

The coal fire has by now been replaced with an electric fire, and the flats have moved into the television age.

The 1909 photo shows a well furnished Edwardian living room, and looking at the census data we can get an impression of the residents of the Millbank Estate (I was going to produce some detailed tables, but ran out of time).

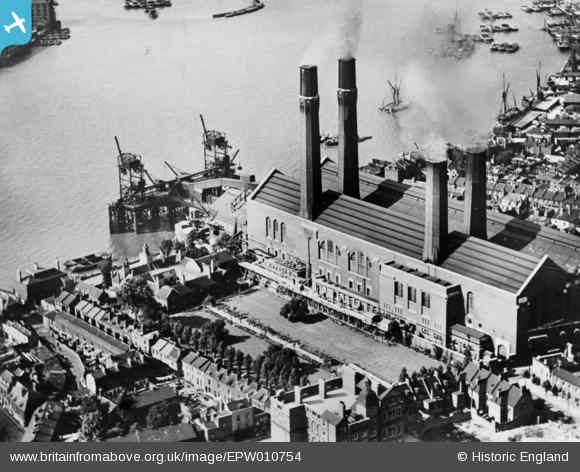

Many or the residents were working / professional people, London County Council employees, Policemen, Workers from the nearby gas works (there were gas holders just to the west of the estate) and also at the Army and Navy Co-Operative Stores both on the Millbank river front, and at the end of the nearby Johnson Street – a street that has since been built over.

There were also residents who had come from the West End following the demolition of many of the slum housing in the area. LCC building was frequently to provide housing for those who had been moved following many of the late 19th century improvement schemes.

Despite this range of jobs, many of the newspaper reports of the opening of the estate still classed the new residents as poor. For example, this report from February 1906 was titled “The King And The Poor”:

“The King visited Millbank on Wednesday and inspected the model dwellings the London County Council had erected on a portion of the site of old Millbank Prison. The Queen accompanied his Majesty. The Royal party left Buckingham Palace at three o’clock in open landaus. The occasion was regarded as semi-private, but thousands of people collected near the point where the reception was to take place. The schools in the neighbourhood were given a half-holiday, and many of the children assembled to see the King.

As to the buildings, the King said they appeared light and comfortable, and these qualities were all the more striking in view of what he saw when visiting some of the lowest slum districts a few years ago. He sincerely hoped that the Council’s scheme would result in nothing but good to those whom it was sought to benefit.”

The Queen’s main concern appears to have been the lack of cupboards in the kitchen, and those who guided the Royal party around the estate promised they would look into the matter with urgency.

As well as the architectural features across the Millbank blocks, it is also worthwhile looking down at the ground, as across the estate are these LCC access covers, dated 1900, so from the original construction of the estate:

The inspiration of the arts and craft movement to the design of the estate is apparent in many of the features, such as the entrances to the blocks:

View between the blocks of Reynolds House, showing the distinctive chequer board patterns of the housing scheme in Vincent Street built for the Grosvenor Estate in the 1920s:

Another example of staggered windows:

The external condition of the Millbank Estate today is very good, and the estate has been through a number of renovations, however this has not always been the case. In 1947 the West London Press reported on a tenants’ protest and a Millbank Estate petition:

“A petition signed by 600 tenants of the Millbank Housing Estate, protesting about the conditions there, was handed by Mrs Lawler of 5 Morland Buildings to Communist L.C.C. member Jack Gaster when a crowded meeting of 200 Millbank Estate tenants was held at Millbank School recently.

Cllr. Gaster will hand the petition to the L.C.C. when their meeting takes place at County Hall next Tuesday.

The petition, which Mrs. Lawler said had met with great support throughout the estate, asks the L.C.C. to provide suitable storage facilities for the storage of coal, so that tenants can build up adequate supplies for the winter months. It also asks for the erection of pram-sheds in the yards to safeguard young mothers from undue strain in pulling prams up many flights of stairs.

The need for the L.C.C. to take immediate steps regarding essential repairs and decorations and to provide labour and materials for cleaning stairs and windows are also stressed in the petition, while a plea is made for railings to enclose the yards to keep children off the streets.”

The L.C.C. did agree that the work was needed, but did not expect the work to completed for a while due to post war shortages of materials and labour.

I suspect that the following photo shows that one of the requests from the tenants of 1947 was delivered, with the provision of pram sheds in the courtyards between the blocks:

Many of the internal courtyards have been decorated with plants and flowers which provide a lovely contrast to the brick of the blocks of flats.

Internal courtyard with plants and lamp post:

The Millbank Estate was built for the working class, and it is interesting how the influx of the new residents changed the demographic of the area. The Morning Post on the 11th January 1906 noted the impact the new estate could have on the General Election, and the re-election of the Conservative MP Mr. W. Burdett-Coutts who had held the Westminster seat for the past 20 years:

“The struggle is rendered the more interesting from the fact that the character of the constituency has greatly altered since the last election. The present electorate is 7,530, and the extensions of artisans’ dwellings on the Millbank Estate and the City of Westminster Council buildings in Regency-street has increased the working class vote to 5,000. This important fact, together with the general effect of the swinging of the political pendulum, and the prejudice raised against the late Government on education, fiscal and other questions, induce the Liberals to think they have a good opportunity of winning the borough in which the Houses of Parliament and so many other important buildings are included.”

Burdett-Coutts did not have to worry, as he won the 1906 election, and would go on to hold the Westminster seat until it was abolished in the 1918 election.

This is Maclise House with the Millbank Tower in the background:

Maclise House is one of the blocks on the Millbank Estate that has this wonderful doorway – it almost looks as if it is providing a portal into another world.

Note how above the entrance doorway, there is the stairway that juts out from the wall, ending at the top with a curved roof.

View back across the courtyard of Maclise House:

This is the view from the north-eastern end of the estate. I am standing by Marsham Street, which turns left in front of the camera. Herrick Street then on the left and Erasmus Street on the right.

There was relatively little bomb damage to the Millbank Estate. Where there was damage it was well repaired – this included the side of the building directly facing the camera in the above photo.

Those children in the 1906 photo at the top of the post could therefore step straight back into the estate and notice few differences – the main changes being almost 120 years of tree growth and parked cars now lining all the streets.

Externally, the housing blocks look impressive and in a well maintained condition. I talked with a few residents in the courtyards and they appeared very happy with their flats.

The London County Council’s Millbank Estate is a far better use of the land than the Millbank Penitentiary that previously occupied the site, however it is good that we can still find a physical reminder of the prison on the boundary of the estate, which shows how the shape of the prison influenced the space occupied by the estate, built by the London County Council for the working class of London.