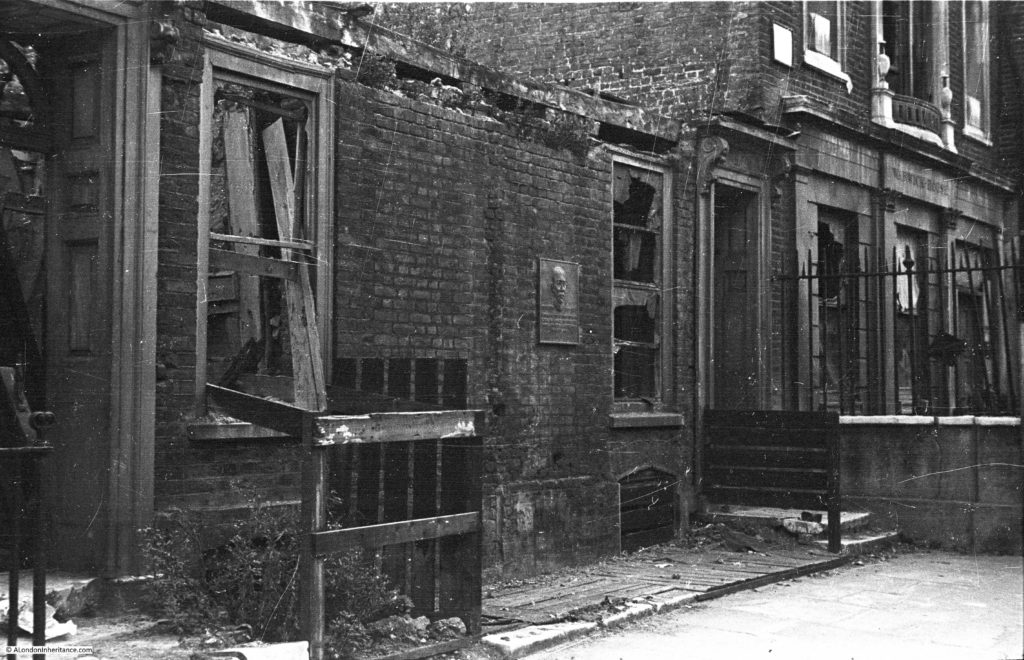

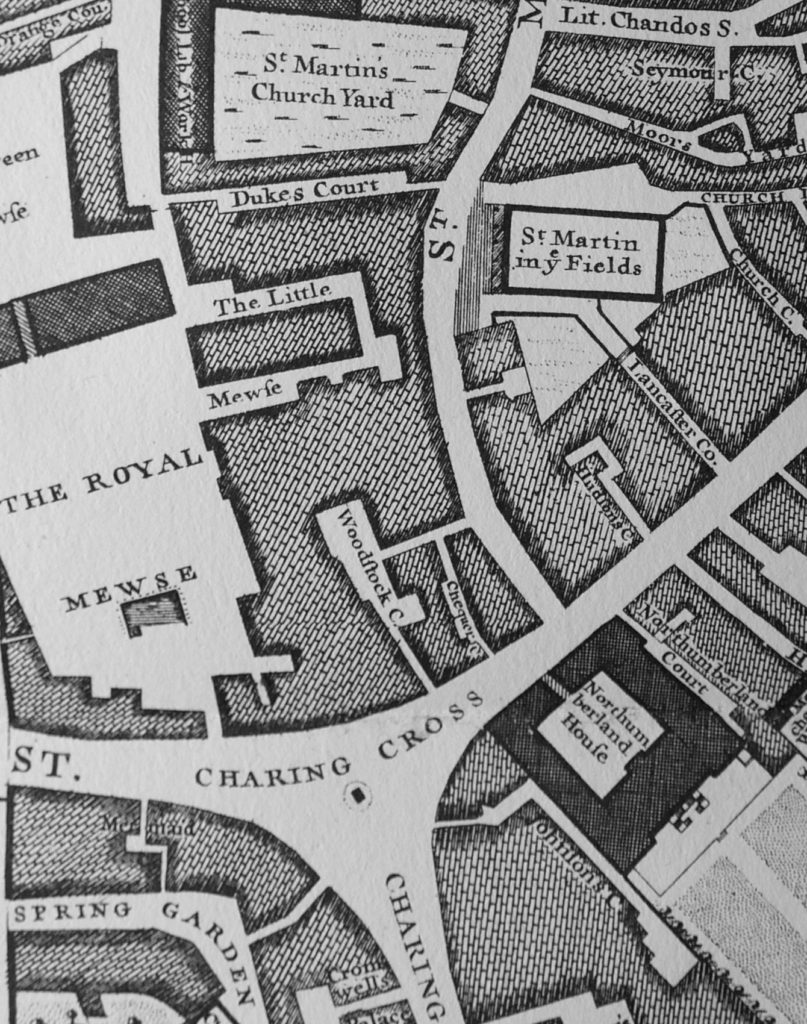

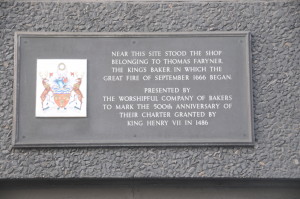

I had not heard of the Dorich House Museum until I was researching my post on a plaque in Gray’s Inn Place published a few months ago. The plaque was the only identifiable feature on a bombed building that my father photographed, and it was the plaque which guided me to the same location today although a new building has been constructed on the site, the plaque remains.

The plaque is of Sun Yat-sen and the sculptor was Dora Gordine (read the original post here).

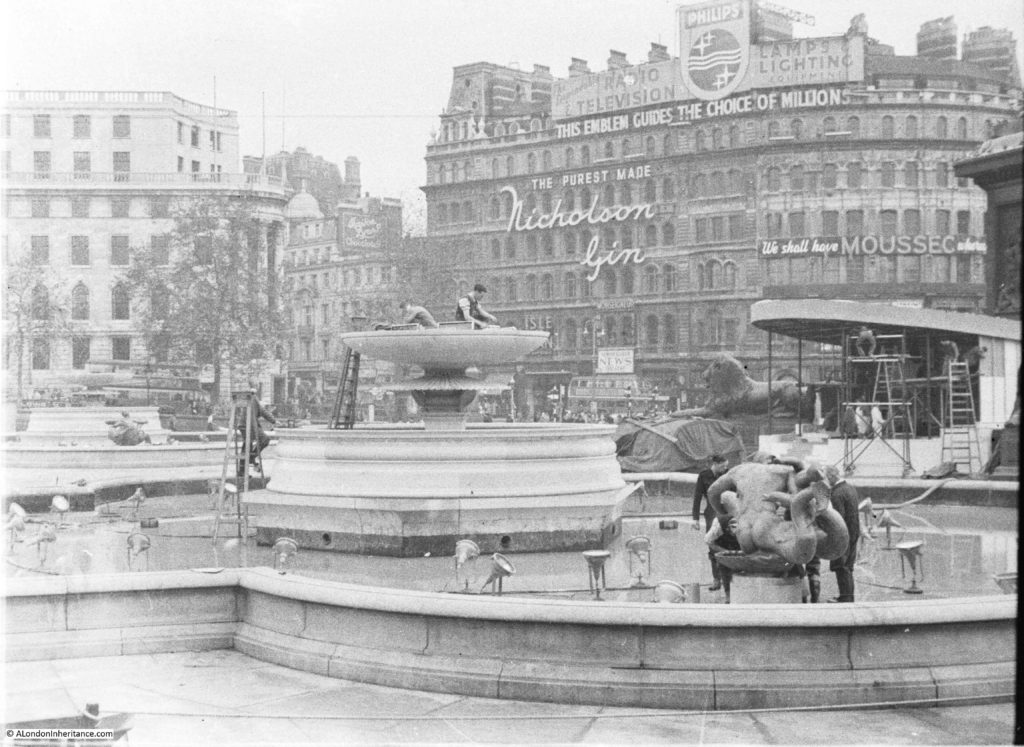

Dorich House is the studio, gallery and living space designed by Dora Gordine in the 1930s and the building today forms a museum of the work of Dora Gordine as well as a remarkable example of a house designed by a sculptor. A few weeks ago I made the trip out to the edge of Richmond Park where the Dorich House Museum is located on the A308, Kingston Vale.

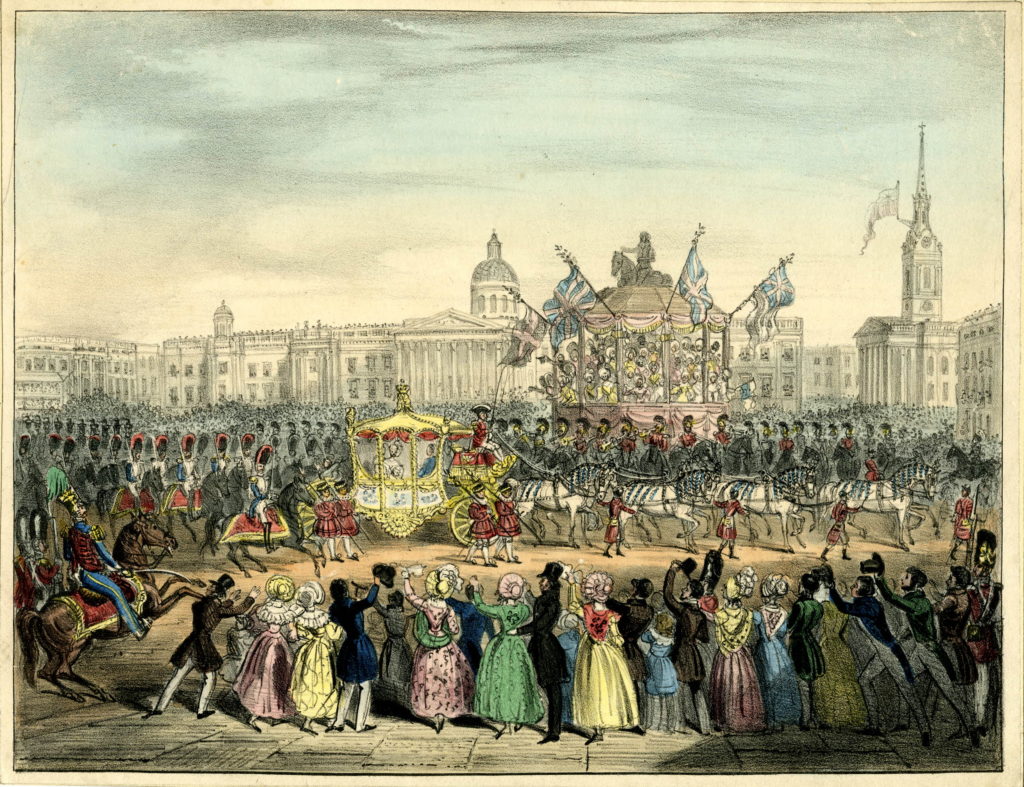

My father’s photo showing the plaque of Sun Yat-sen by Dora Gordine in Gray’s Inn Place:

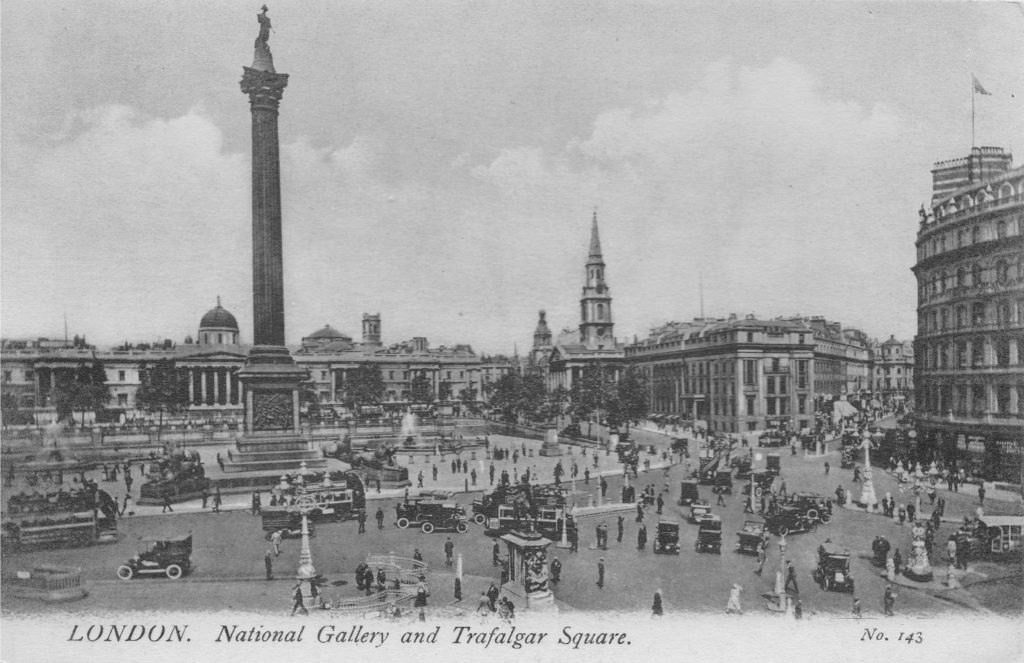

The same location today:

Dora Gordin (she added the ‘e’ to the end of her surname in 1925) was born in Latvia on the 8th of June 1895 into a Russian Jewish family. The family soon moved to Estonia where she attended the National School of Applied Arts and Crafts in Tallin. After the Russian Revolution Dora’s brother Leopold left Estonia for London where he married an English women, studied engineering at Edinburgh University and then settled in Pimlico, became a British Citizen in 1930 and started a career as a civil engineer.

In 1924 Dora moved to Paris and established a home studio and started work. Whilst in Paris her work was exhibited in a number of exhibitions and she also worked as a painter in the British Pavilion at the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Industriels Modernes.

In Paris she met David Gourlay and his girlfriend Janet Vaughan, members of the Bloomsbury Group, and it was through them that she moved to London in 1926, staying at Taviton Street where she met many other artists, writers and photographers.

Whilst in London, her work was being purchased by influential collectors including the millionaire businessman Samuel Courtauld.

She had a studio home designed and built in south-western Paris and in 1930 moved to Singapore for four and half years, where she became a British citizen by marrying Dr George Herbert Garlick, the deputy medical officer of the State of Johore. Although she was living in Singapore, her work was still being exhibited in London.

In 1935 she left Garlick and returned to London via Paris where she was soon involved with the Hon. Richard Hare, the son of Richard Granville Hare, the 4th Earl of Listowel. It was Richard Hare who purchased the land in Kingston Vale in the same year for Dorich House which was completed the following year, when they were also married at Chelsea Registry Office.

Her separation from her original home and family in Estonia was complete and she never returned to Estonia, or appears to have been in much contact with her family. Her mother died in 1930, her brother Nikolai was murdered by the Nazis in 1941. Although not recorded, her sister Anna was almost certainly also murdered by the Nazis, the fate of all the Jews remaining in Estonia.

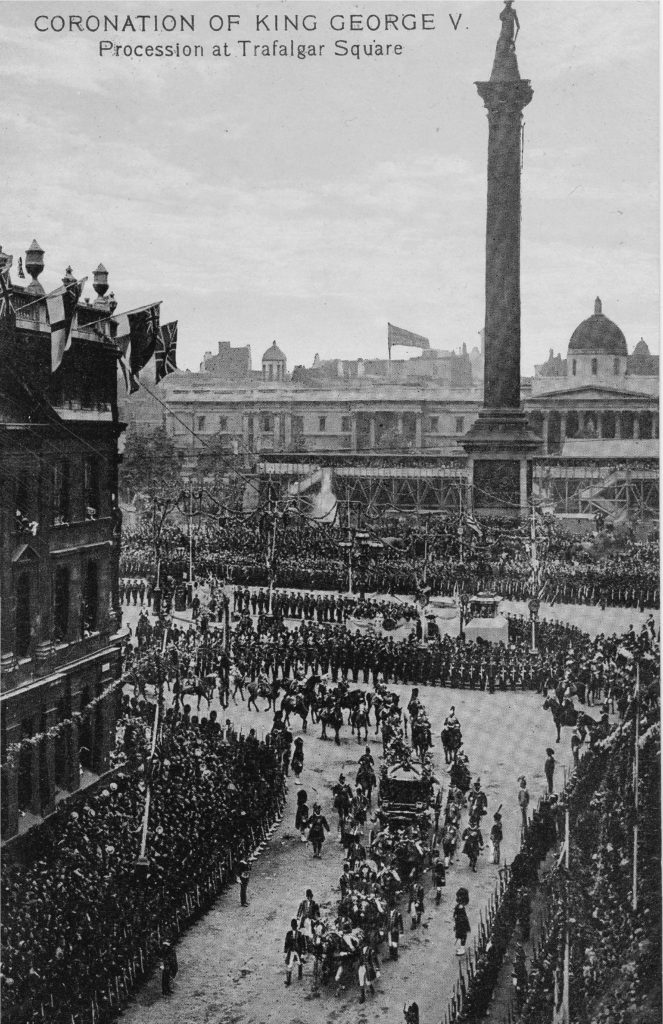

Dora Gordine on the stairs of Dorich House:

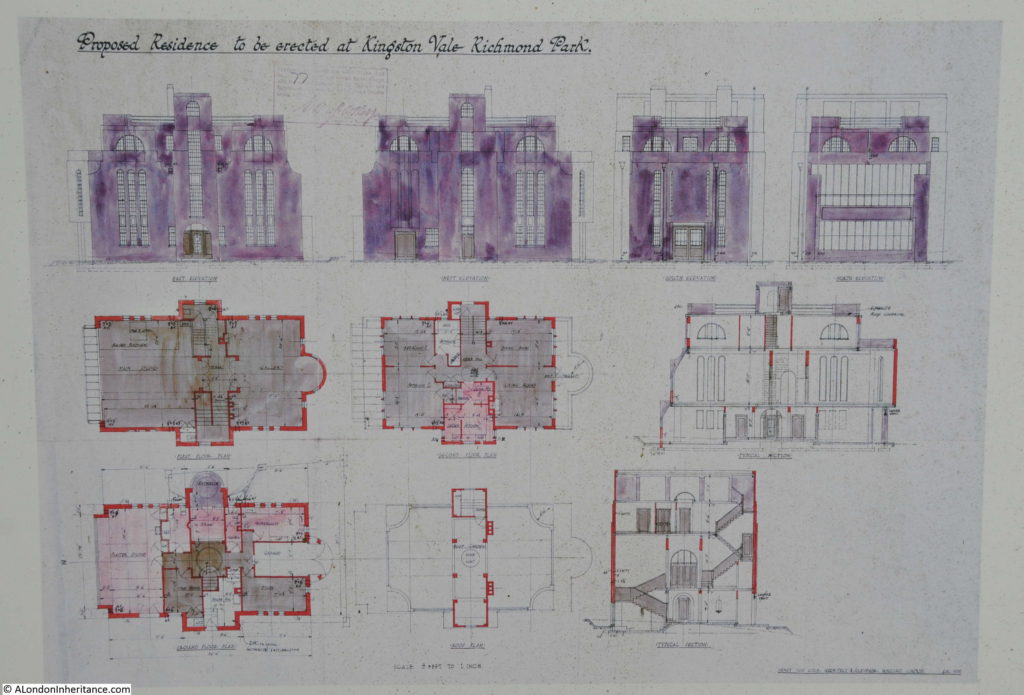

Dorich House was built in 1936 to a design by Dora Gordine. The name of the house is a combination of their first names DORa and RICHard, and Dora lived and worked in the house until her death in 1991 (Richard died in 1966 and after his death Dora never remarried and continued to live and work in the house).

The house was specifically designed to provide studio space for Dora to work, gallery space and a floor designed as a self-contained flat. The flat roof provides a viewing space to look over Richmond Park and the surrounding area.

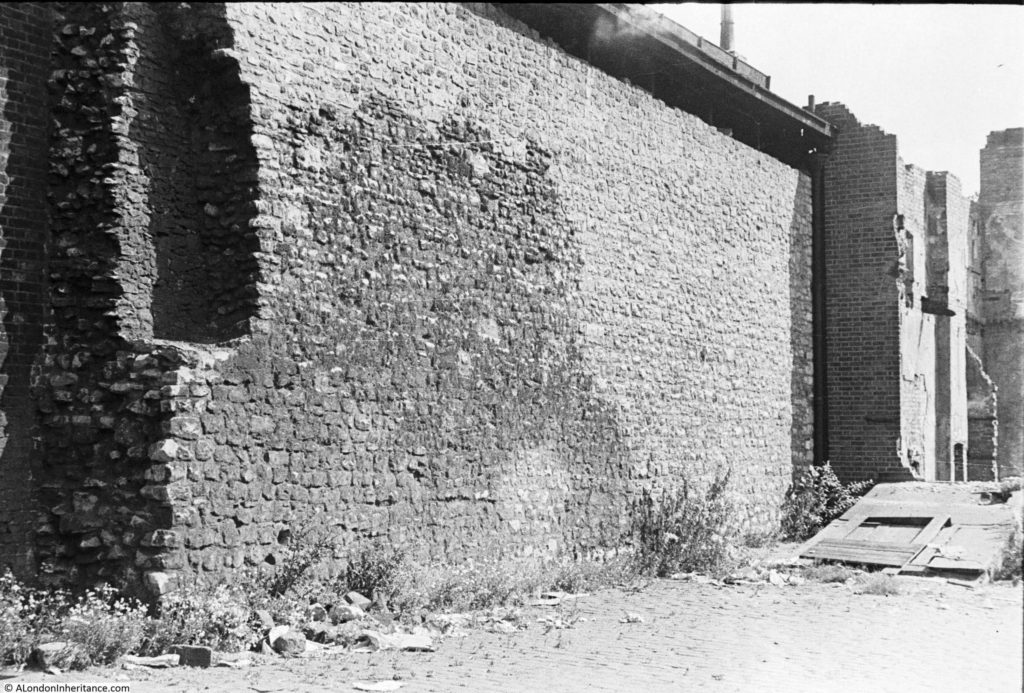

On first sight, Dorich House presents a fortress like appearance with the outer walls constructed of industrial red brick. Large windows provide an indication of the light needed for the studio and gallery space.

Side view of the house showing the large glass windows of the studio and gallery space:

There is a panel outside the house showing the original plans:

From outside, there are clues to the displays to be found inside the house:

After Dora’s death in 1991, the house was purchased and restored by Kingston University and is now open as a museum displaying Dora’s work, and to see a building, designed by an amateur architect in the 1930s which perfectly suited her work as a sculptor and provided a remarkable living space.

The overall construction of the house is of brick outer walls with reinforced concrete floor slabs and flat roof. The use of reinforced concrete floors allowed large floor spans in the studio and gallery which provided the space to work and display.

The plaster studio on the ground floor is now used to display a film on the life of Dora Gordine, information panels and displays of her work:

Also in the plaster studio is a copy of the bronze relief “Power” by Dora Gordine, commissioned for the Administration Block of the Esso Refinery at Milford Haven.

Walking up the stairs to the 1st floor, the height of the floors is visible as are the large windows throughout the building that provide a wonderful use of light.

Half way up to the 1st floor landing:

On the first floor landing, arched doorways lead to the gallery area:

Where many examples of Dora Gordine’s work are on display. The high ceilings and large windows provide a perfect gallery space. The gleaming wooden floors were part of Dora’s design and she would get visitors to put on slippers to protect the wood.

The 2nd floor provided a self-contained flat where Dora and Richard lived. The rooms have been restored and furnished to provide an impression of how they would have looked during Dora and Richard’s occupation of the house, and they also display some of Dora’s early paintings and drawings along with the Russian art and artifacts collected by Dora and Richard.

Throughout this floor, large semi-circular windows provide considerable amounts of light into the rooms:

The dining room:

Connecting the two main rooms on this floor, which are now furnished as dining and living rooms, is a large circular door. The door has a unique design, in that it does not open outwards, but opens by the two individual panels retracting into the walls (although there was no sign saying not to, and although very tempting, I thought it better not to try to open the door).

There are photos in the house showing the door fully open with the panels concealed within the wall and the doorway providing a large, circular opening between the two rooms, changing the way in which these spaces are viewed.

The opposite side of the door from the living room:

View of the living room. An intimate space, but again well lit by the large semi-circular windows.

The 2nd floor living area contains smaller examples of Dora’s work:

Original tiling around fireplaces:

Views across to Richmond Park:

The flat roof has a central covered area and two large open spaces on either side. In the centre of the covered area is the figure “Running boy with balloon”:

The large, flat roof:

The height of the building is clear from the roof when looking over the surrounding buildings:

Dorich House was Dora Gordine’s dream home. The home was designed by Dora, her strong personality was very different to her husband Richard’s reserved character and this comes through in a house that was designed for her work and based on her views of modernism. There is a small room in the house that was Richard’s study, considerably smaller than the spaces within the house used by Dora.

The house was designed to promote healthy living with plenty of natural light and the roof terrace providing access to fresh air (Dora and Richard would have their meals on the roof terrace when the weather was good) and a high vantage point to look over their surroundings.

Walking through the house, it is also apparent that whilst the windows provide plenty of natural light into the house, they are also designed and positioned so that the viewer is not distracted by the external view and the focus is on the sculpture displayed within the rooms. The one exception to this are the living rooms where the lower, semi-circular designs provide good views of the surroundings.

Dora and Richard appear to have enjoyed an idyllic life at Dorich House. After 1950 they do not seem to have employed a house keeper and managed the house on their own. Dora worked on her sculpture and Richard continued his academic work on Russian art and literature. They had a very active social life at the house with a wide circle of friends from Richard’s former diplomatic work, artists, collectors of Russian art and their neighbours.

Dora Gordine had a long and fascinating life, from her birth in Lativia to her death in Kingston. She had traveled widely and avoided the fate of so many of her generation and background in both the Russian Revolution and the 2nd World War.

As usual, I feel I have not been able to do justice to such an interesting subject in such a short post (working out of the country this week has not helped), however it was fascinating to visit the Dorich House Museum and explore both the sculpture and architecture of Dora Gordine.

I will finish the post in the same place as I started with the plaque of Sun Yat-sen by Dora Gordine, unveiled in 1946 on the bombed building in Gray’s Inn Place. At the unveiling by Mr C.K. Sze, the Chinese charge’ d’affaires at the London embassy, Lord Ailwyn (President of the China Association) thanked Dora Gordine “for her worthy memorial and for her interest and inspiration born of her love and experience of China and the East which has enabled her to execute this simple and dignified bas-relief”