There are places in London where the subterranean history of the city touches the surface and it is easy to imagine finding long lost geological features beneath the city streets.

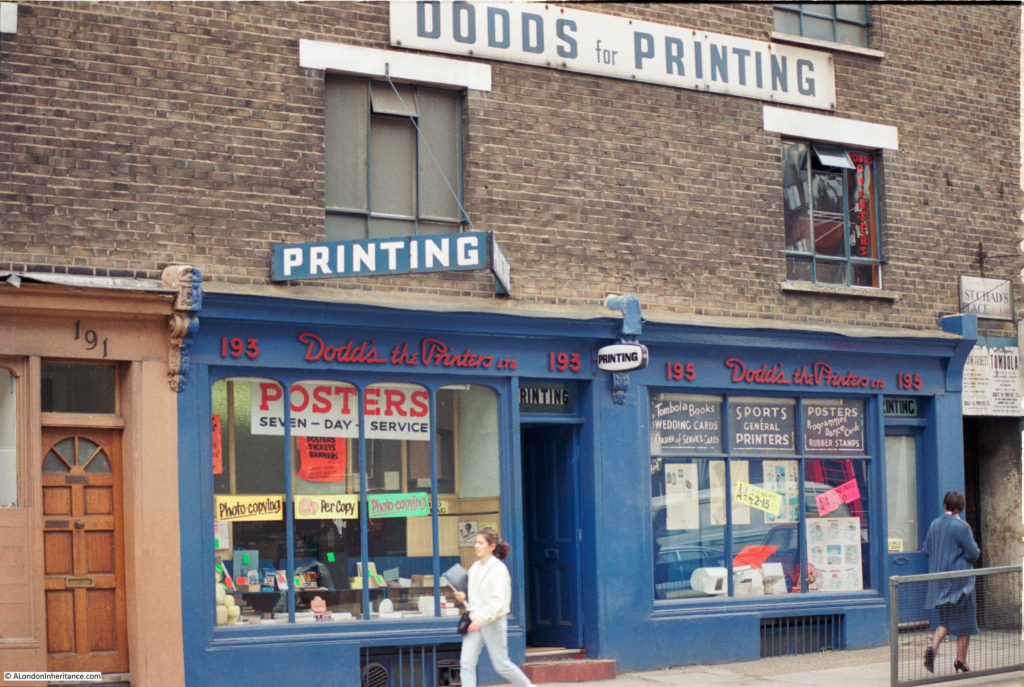

This post is about one such place that I found whilst hunting for the location of this photo that my father took in 1986:

My 2018 photo of the same location:

I am in King’s Cross Road, a street that runs from Pentonville Road to Farringdon Road. The building was the location of Dodds the Printers in 1986 who occupied numbers 193 and 195.

I am not sure when the business closed in King’s Cross Road, however I believe it was relatively recently. The shop front has changed and the lovely signage above the shop has disappeared, however the terrace of 19th century buildings are much the same.

On the right side of both photos is an alley disappearing through the buildings. This is St. Chad’s Place. The following extract from OpenStreetMap shows the location. St. Chad’s Place can be seen running left to right in the middle of the map – suitable for vehicles to just after crossing the rail lines where it turns into a pedestrian alley, with a sharp bend and a narrow stretch running up to King’s Cross Road.

This is the type of view I love – a small alley to explore:

Walking into St. Chad’s Place from King’s Cross Road, you first pass through the terrace lining King’s Cross Road before continuing down a narrow stretch between high brick walls.

Looking back towards King’s Cross Road:

At the end of the narrow stretch, the alley does a 90 degree bend and opens out slightly:

This is the view back down the alley with the buildings lining King’s Cross Road in the distance:

The alley passes a number of old brick, industrial buildings, gently rising in height. Half way along the alley there are high metal walls. This is where St. Chad’s Place passes over a railway.

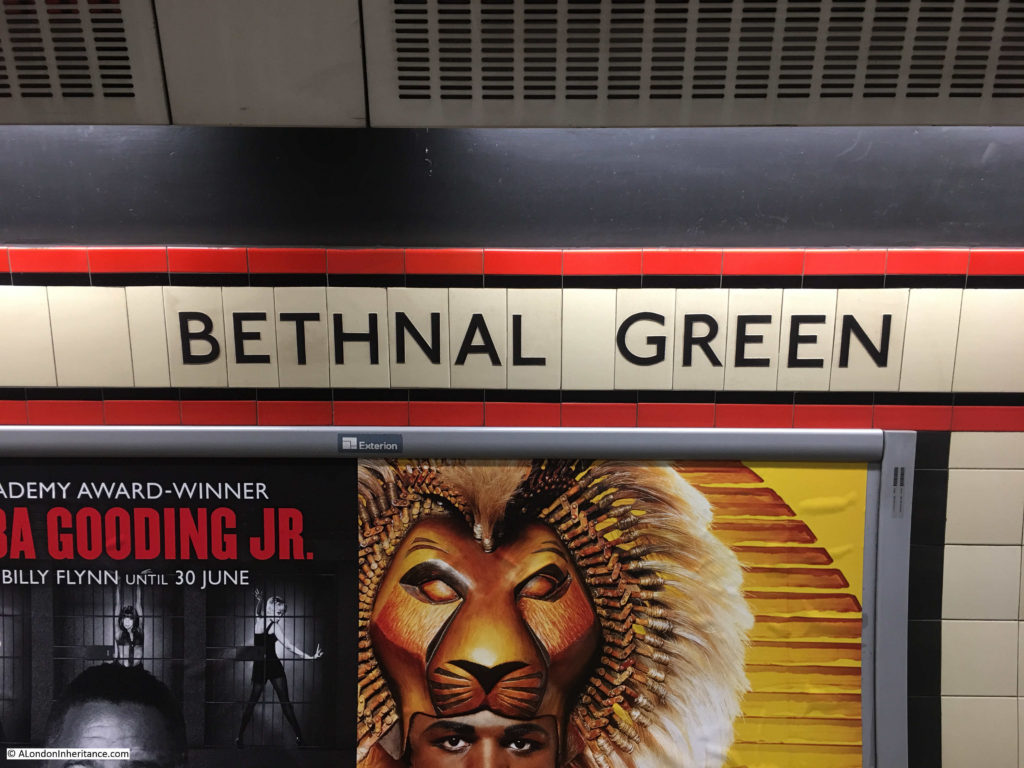

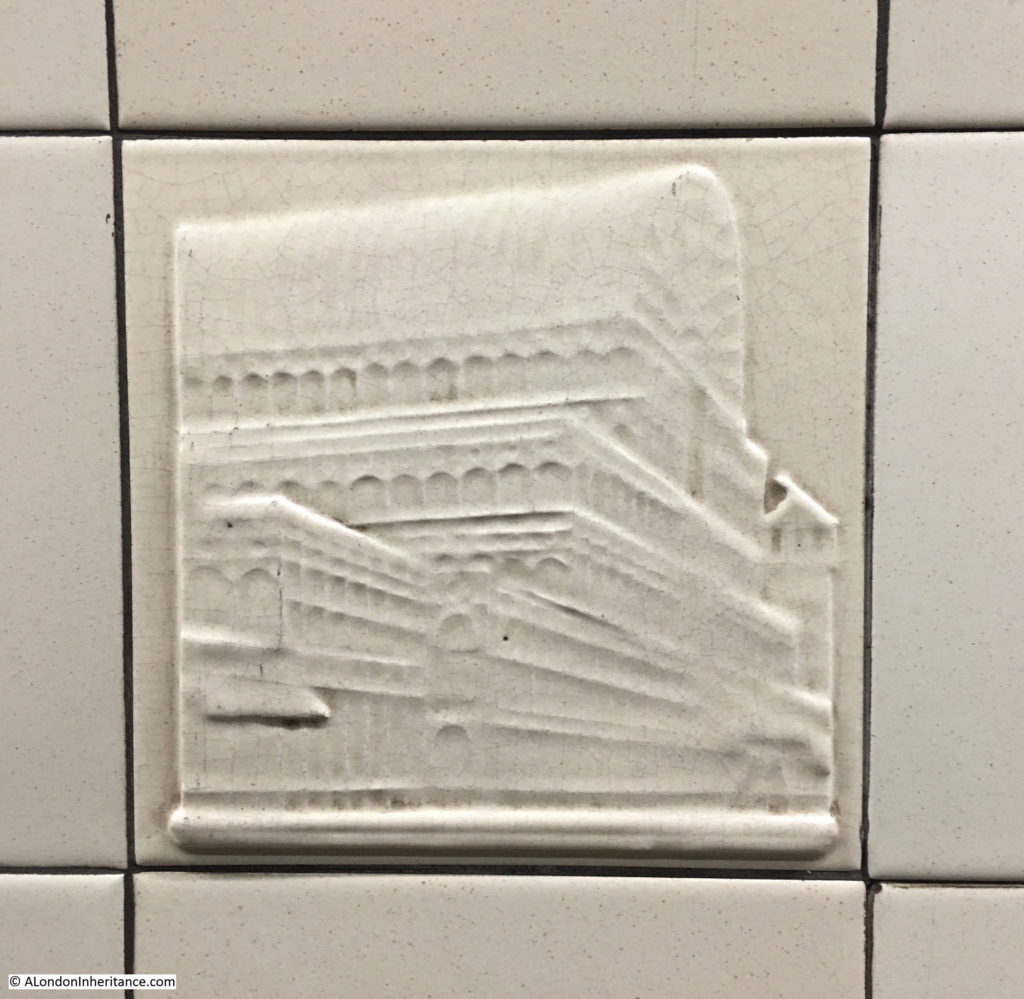

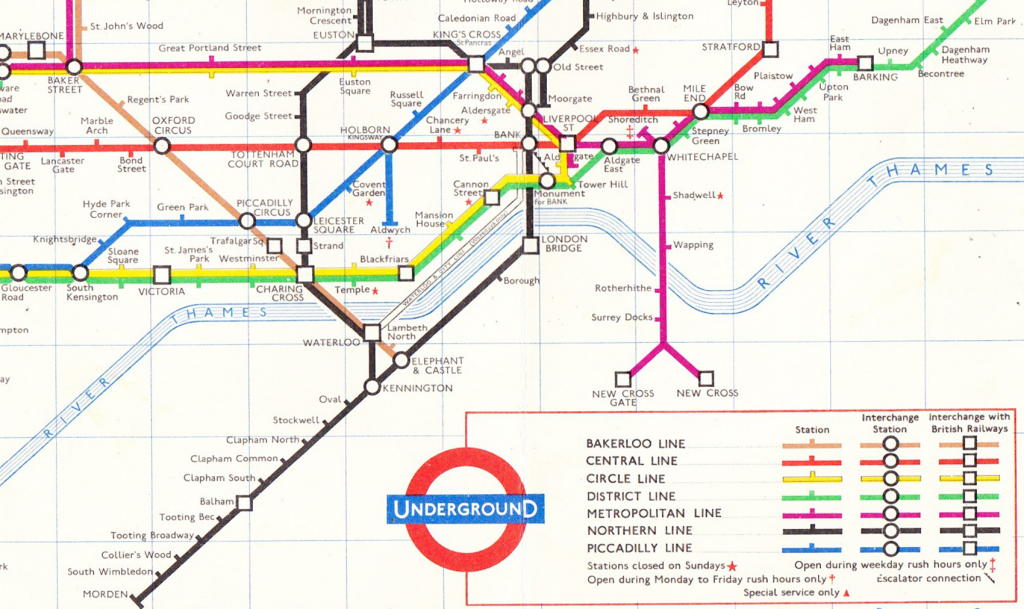

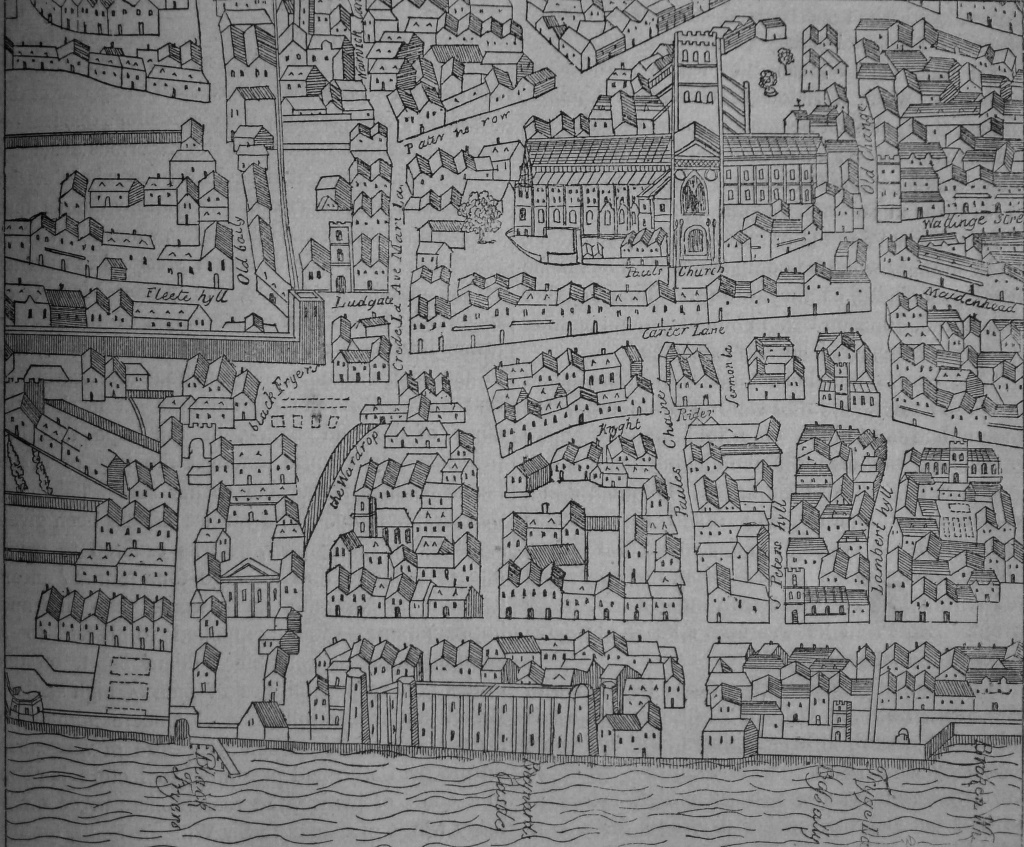

It is just possible to peer over the top of the metal walls and look at the railway beneath. This is the original Metropolitan Railway, built between 1859 and 1862, which ran from Paddington to Farringdon.

The railway was built below street level, using a mix of cut and cover, as well as leaving the railway in an open cutting, as in the stretch that passes underneath St. Chad’s Place.

The route today is used by Thameslink trains and the London Underground Circle, Metropolitan and Hammersmith and City lines. In the following photo, looking south towards Farringdon is a Thameslink train, with the red of an underground train just visible to the upper right.

The railway cuts a wide path between King’s Cross and Farringdon, but for the most part is not that visible. Walking along King’s Cross Road or Gray’s Inn Road, you would not know there is a railway running close by, it is only when you walk through the streets between these major roads that you pass over, and get a view of the cutting through this part of the city.

This is the view looking north from St. Chad’s Place where the railway runs into King’s Cross, St. Pancras underground station:

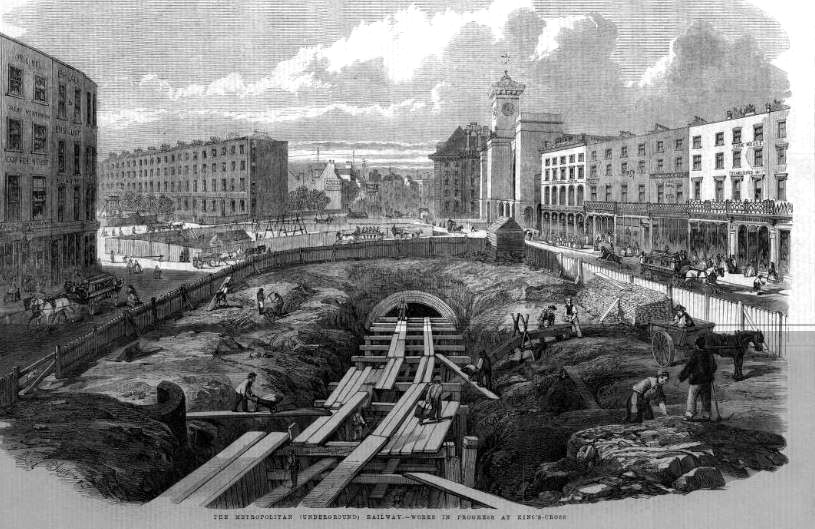

The building of the railway must have been very disruptive to the area. Streets were cut off and before construction of the railway could start, demolition of hundreds of houses, factories, warehouses and workshops was required.

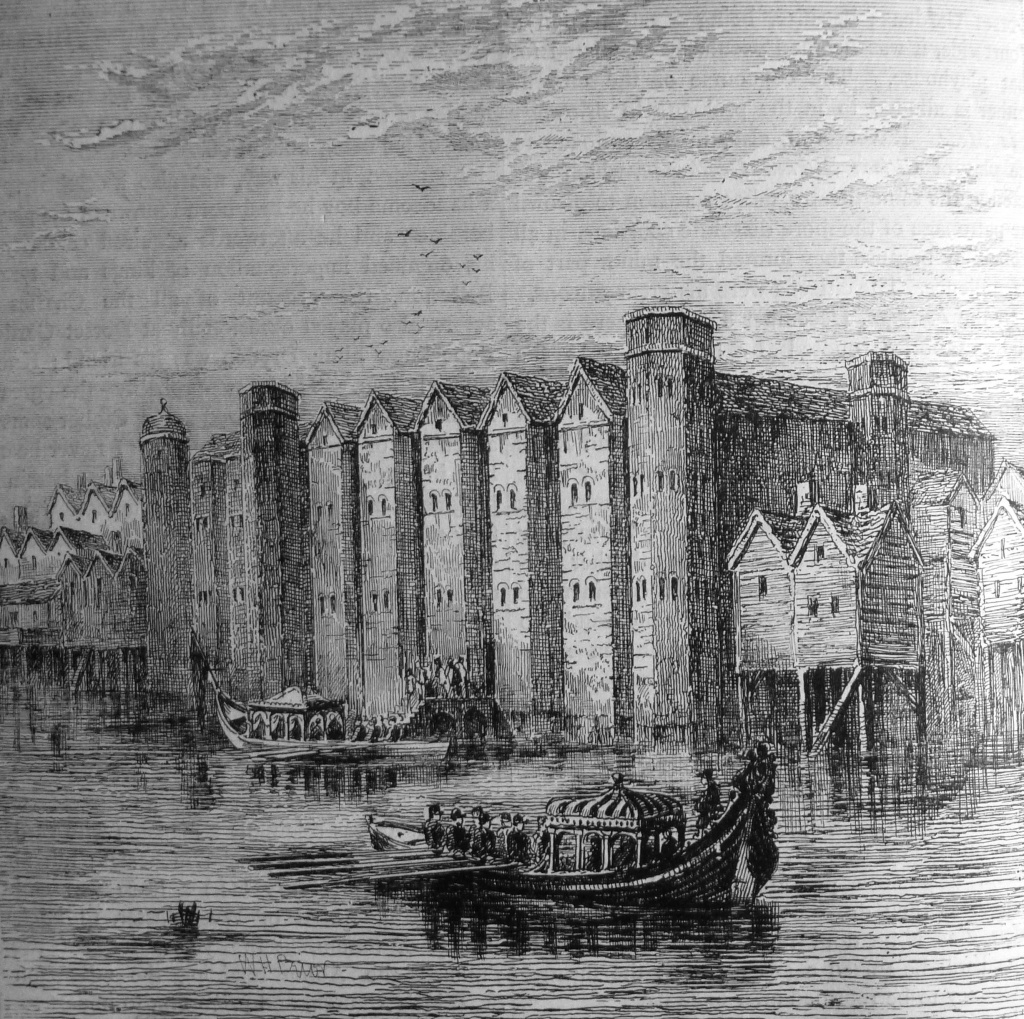

The following print shows the building of the railway near King’s Cross:

Walking up towards Gray’s Inn Road, this is the view back down St. Chad’s Place. A narrow, cobbled roadway in the centre, sloping down to where the blue metal wall of the railway can be seen on the right.

The black sign on the left is for Meat Liquor bar and restaurant, probably the main reason for anyone to walk down St. Chad’s Place. Apart from the person sitting outside the restaurant, I did not see anyone else walk through for the whole time I was in St. Chad’s Place.

At the top is the junction with Gray’s Inn Road.

A walk through St. Chad’s Place is a glimpse of the many old alleys that once ran between major streets (I will be writing about one that is in the process of disappearing in a future post), and the view of the railway provides an insight into what is just below London’s surface, however, as usual, there is always more to discover.

Starting with the name, St. Chad’s Place, this is an indication of what was once here.

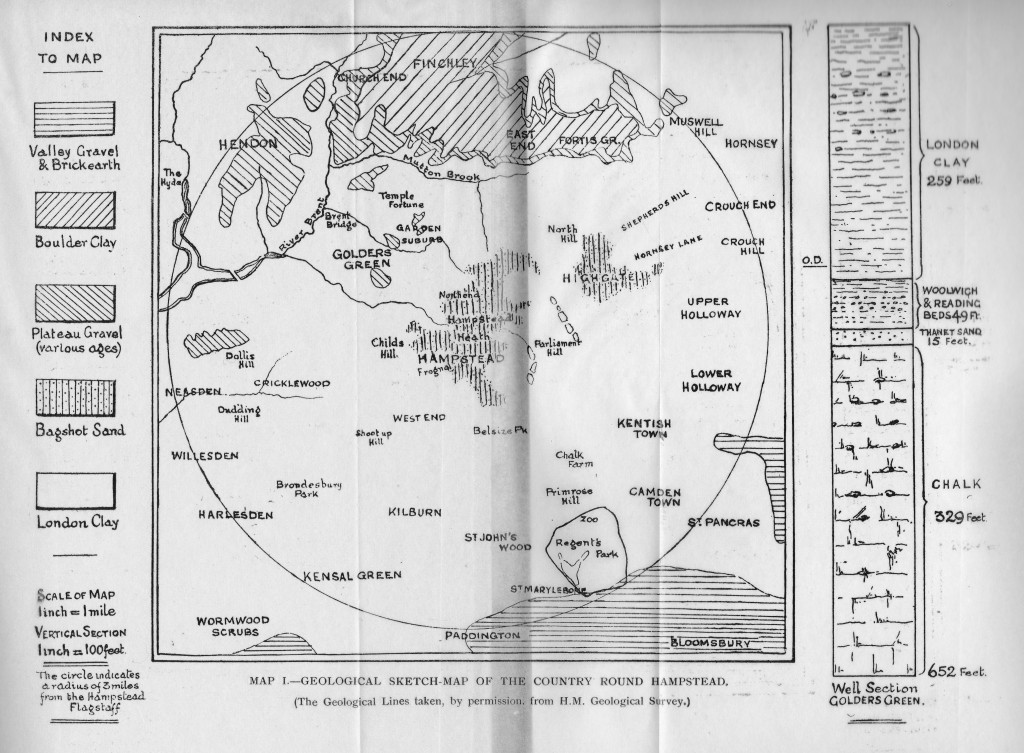

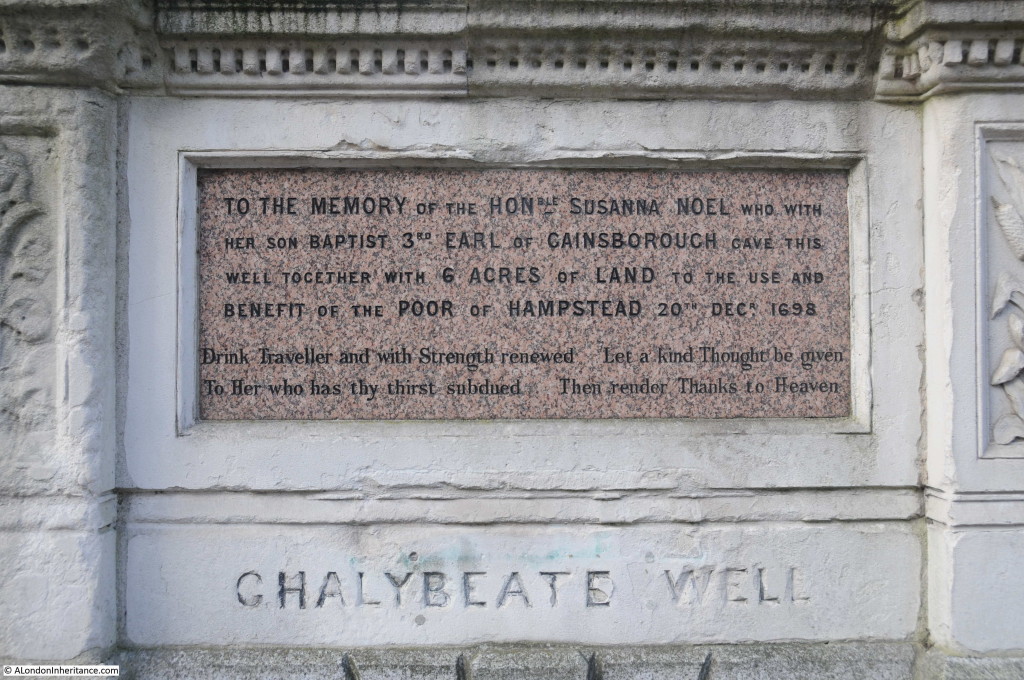

The route of the River Fleet was once alongside where King’s Cross Road now runs, and the geology of the area gave rise to a number of springs at Bagnigge Wells, Clerks’ Well (Clerkenwell), and a St. Chad’s Well. All running close to the River Fleet.

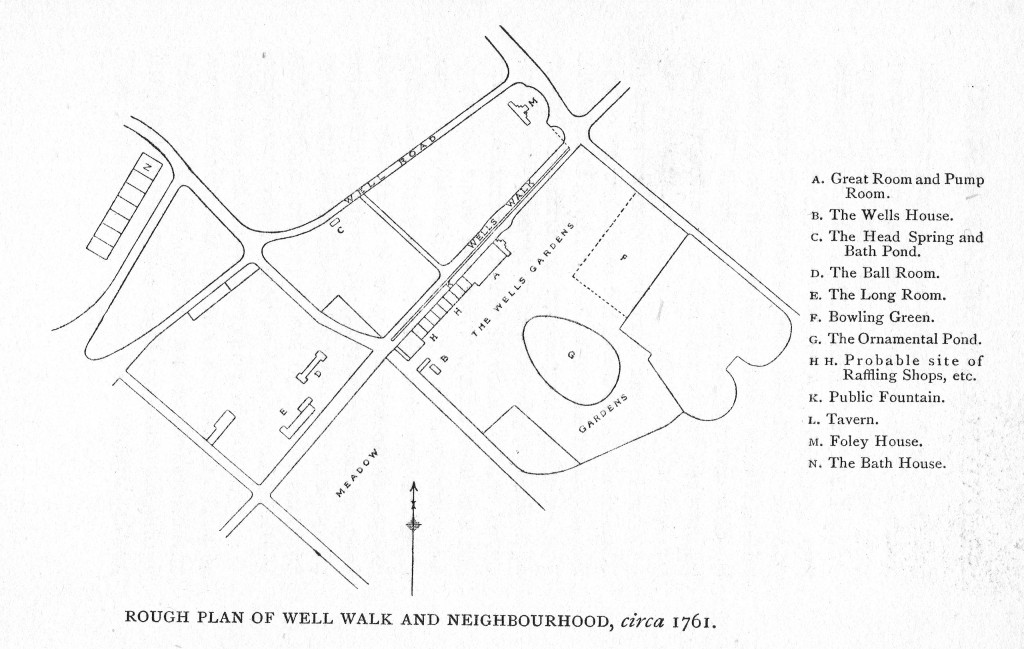

St. Chad’s Well was to be found at the junction of St. Chad’s Place and Gray’s Inn Road.

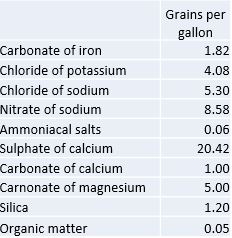

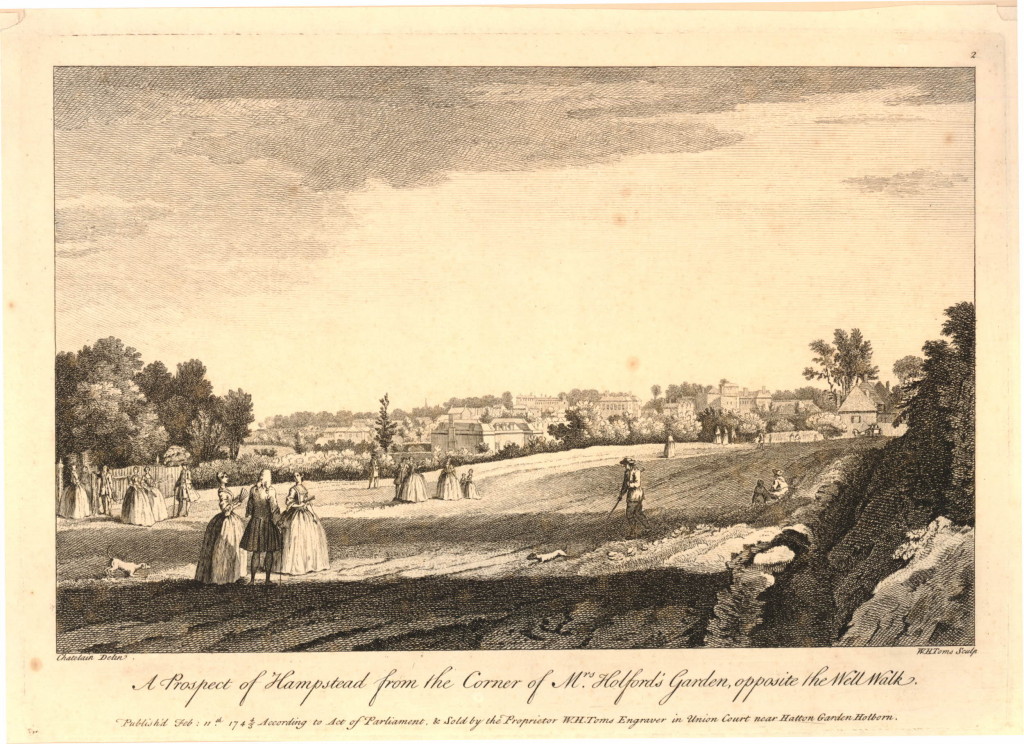

The well was very popular in the middle of the 18th century, with around 1,000 visitors a week travelling along Gray’s Inn Road to take the waters.

The following advert from the 29th May 1807 edition of the Morning Advertiser gives an impression of how St. Chad’s Well was sold to Londoners:

“St. Chad’s Wells – Health restored and preserved, by drinking the Battle-Bridge Waters, commonly called St. Chad’s Wells, formerly dedicated to St. Chad, first Bishop of Lichfield. These Waters are recommended by the most eminent Physicians as the best Purging Waters in England, they are found highly efficacious in removing all Complaints which affect the Urinary Passages such as Stone, Gravel, etc, They likewise cure the Scurvy, Bile, Worms, Piles, Indigestion, Nervous Complaints, Seminal Weaknesses, and various other Disorders too numerous for an advertisement. Several attestations of their wonderful Effects may be seen in the Pump room.

N.B. These Waters may be drank every morning, at 4d each Person, or delivered at the Pump-Room at 8d per gallon. The Gate leading to the Wells opens at the end of Gray’s Inn-lane Road, near the Turnpike.”

The name Battle-Bridge Waters refers to the Battle Bridge, a brick arched bridge over the River Fleet just north of St. Chad’s Place. The name Battle Bridge is often taken to refer to a battle fought here between Boadicea and the Roman army, however this is very unlikely as the name in medieval manorial court rolls was Bradeford Bridge.

Chad refers to a 7th century Mercian churchman who founded the first monastery in Lichfield. St. Chad allegedly preached at Stowe, just outside the centre of Lichfield , and a medieval St. Chad’s Church was built at Stowe along with a holy well with St. Chad’s name. This association with a well could be why the well in Gray’s Inn Road took St. Chad’s name – a more virtuous, health promoting name than Battle Bridge.

The following print from 1850 show the St. Chad’s Well pump house, built close to Gray’s Inn Road. At the rear of the house, gardens stretched back towards King’s Cross Road.

By the time of the above print, the well was declining in popularity. I cannot find exactly when St. Chad’s Well closed, however St. Chad’s Place was built over part of the garden in 1830 and the majority of the gardens were lost in 1860 when the Metropolitan Line was built. I suspect it was the building of the railway which finally swept away the well.

Now this is where this post starts to get very speculative.

I am sure though of the route of the River Fleet. I have checked a number of sources, including the book “The Lost Rivers of London” by Nicholas Barton and Stephen Myers (a well researched and illustrated history of London’s lost rivers and their routes through the city) as well as “The History of the River Fleet” by the UCL River Fleet Restoration Team, and they all show the River Fleet running along the western edge of King’s Cross Road, under where St. Chad’s Place meets King’s Cross Road.

The River Fleet is also shown on the OpenStreetMap extract, running parallel to King’s Cross Road.

St. Chad’s Place descends very gradually as you head from Gray’s Inn Road towards King’s Cross Road, which could be expected for a spring rising near Gray’s Inn Road running through the gardens of the pump-room and down to the River Fleet.

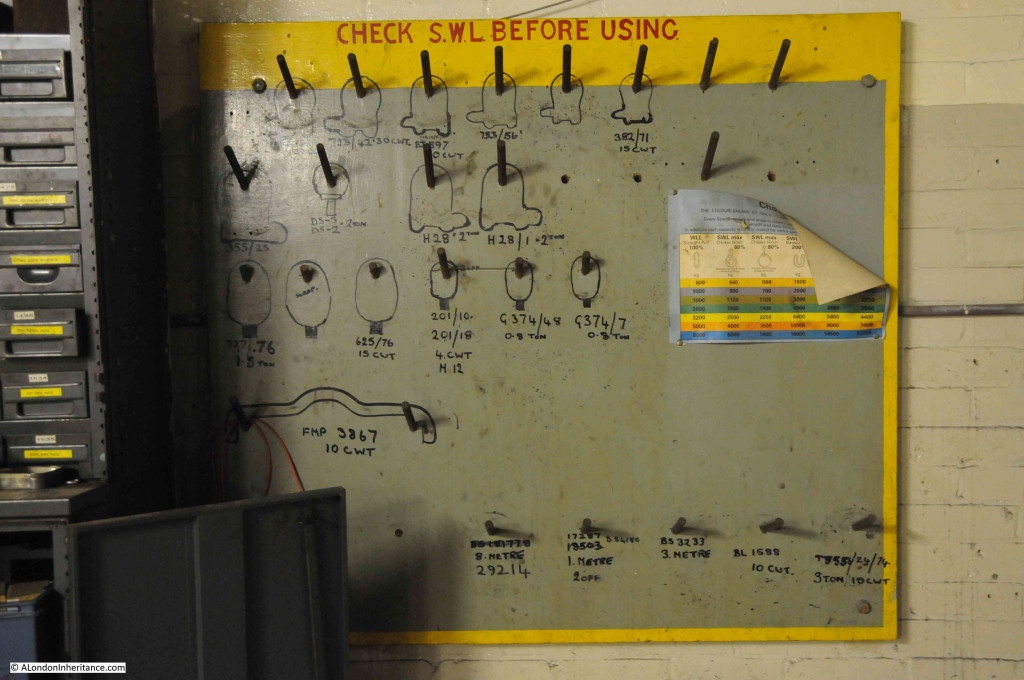

As I walked along St. Chad’s Place, the sunlight glinting off running water below a small grating in the middle of the cobbled street caught my eye.

It was hard to judge the depth, but it must have been around 10 to 15 feet below the road surface. It looked to be a fast flow of clean water, and yes I did take a sniff and it did not smell like a sewer.

I have no evidence to support this, apart from the view through the grating, however it is interesting to imagine that perhaps the waters of the St. Chad’s Well still rise here, and run along St. Chad’s Place, heading towards the River Fleet.

They would now be cut off by the cutting made for the Metropolitan Railway, however perhaps there is a pipe that carries them across, or a separate sewer that runs along the western edge of the railway.

Walking back towards King’s Cross Road, and where St. Chad’s Place passes through the building facing King’s Cross Street, there is a run of old paving slabs, and an old manhole cover.

This is exactly where the River Fleet is shown to run parallel to Kings Cross Road.

If you walk past 193 and 195 King’s Cross Road, take a detour into St. Chad’s Place. Walk up to Gray’s Inn Road and you will cross the River Fleet, the original Metropolitan Railway and the site of St. Chad’s Well – not bad for a couple of minutes walk.

And with some imagination, perhaps you will also see the waters of St. Chad’s Well still running beneath a small, four hole grating.