This week, I am back in Wapping, exploring one of the stairs that line the River Thames – King Henry’s Stairs.

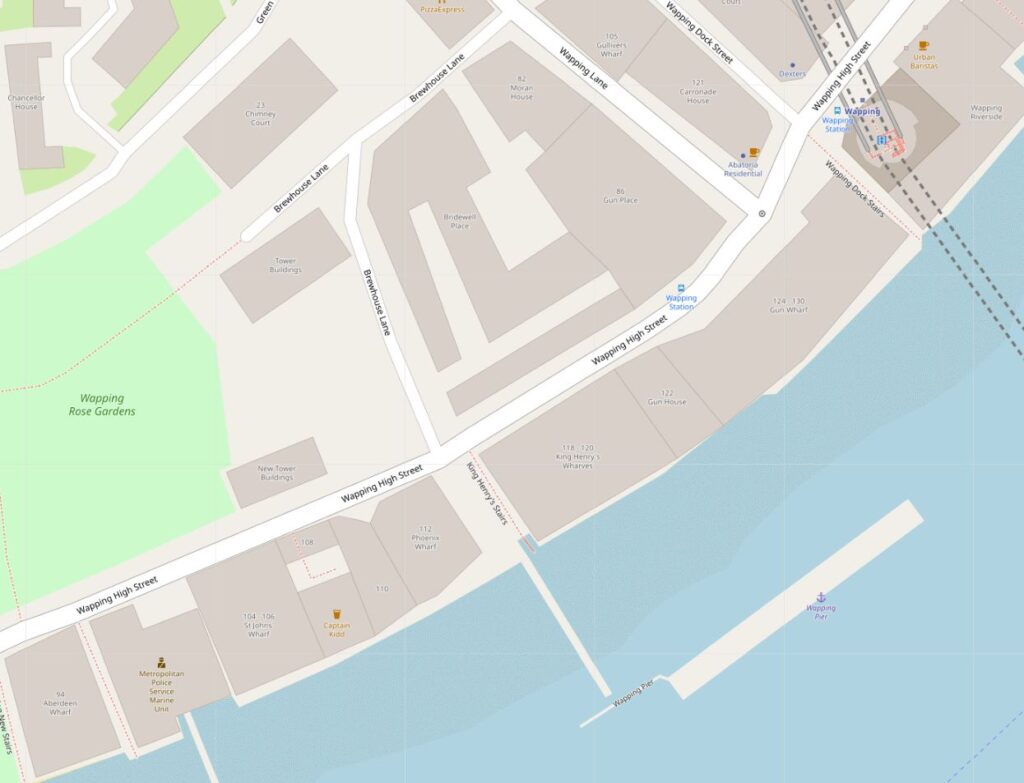

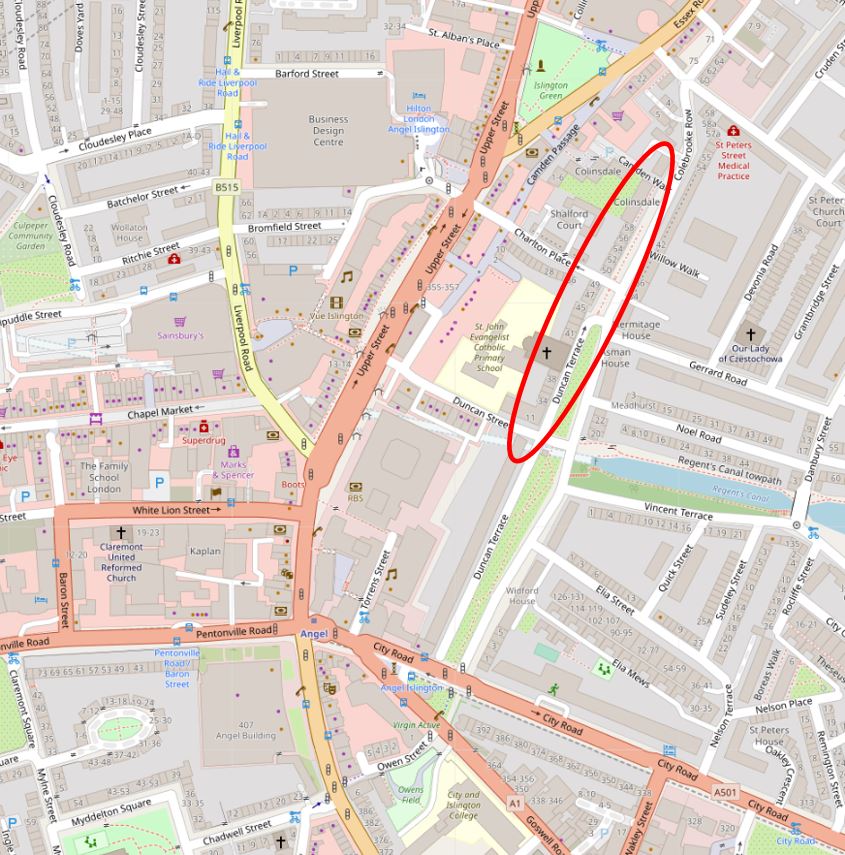

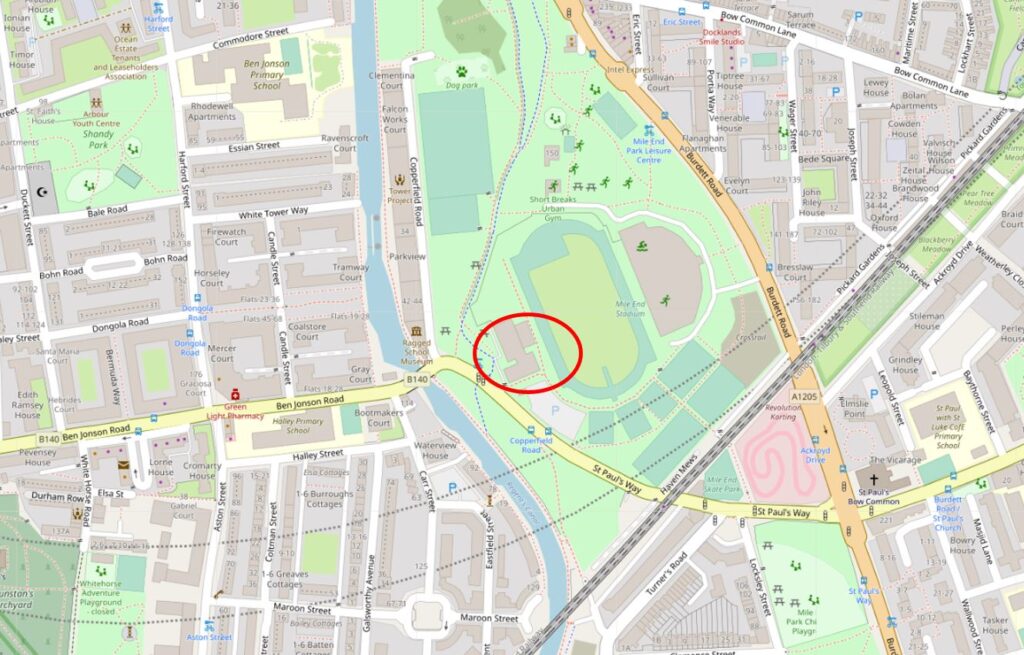

The location of King Henry’s Stairs is shown in the following map. Along Wapping High Street, they are adjacent to Wapping Pier, and opposite Brewhouse Lane (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

The alley that leads to the stairs, opposite Brewhouse Lane:

The alley is between two of the few remaining undeveloped buildings alongside Wapping High Street. Looking towards the river, the Phoenix Wharf building is on the right and on the left is King Henry’s Wharf. Not yet developed into the standard apartment building which has been the fate of the majority of old warehouses that line the river. I am sure their time will come, indeed Phoenix Wharf has had a number of planning submissions and ownership changes, but nothing yet seems firm as yet.

King Henry’s Stairs are unusual for a number of reasons. Their current name is not the original name, they have a rather macabre history, and alongside the location of the stairs is the Wapping Pier, with an elevated walkway leading alongside the stairs out to the pier.

The following photo shows the entrance to the stairs down to the river foreshore, with the walkway to the pier on the right:

However looking over the edge, where one would expect to see a series of stone steps leading down to the foreshore, there is nothing but a sheer drop down to the sand and mud below.

On the right, a metal ladder, a couple of feet out from the edge of the stairs, is hooked over the pier, and provides the only access to the foreshore below:

I stood there for a few moments trying to decide whether the ladder was safe. It looked straight out of a TV hospital drama, where you know what will happen next and anyone risking the ladder would find themselves flat on the ground below.

Swinging one foot out to the ladder, it swung on where it was hooked to the pier, the ladder not being fixed to the ground. Other foot on the ladder, and despite swinging I made it to the ground.

The foot prints in the above photo are mine as I took the photo after getting back up. On arrival the sand and mud was perfectly smooth.

Looking back at the ladder from the foreshore. It may have been fixed at the base at some point, but today is just hooked over the rail alongside the walkway out to the pier. Apart from a couple of steps at the top, there is no evidence of any steps having ever been in place.

The view back to the entrance. When I arrived, the blue gate was wide open which seems somewhat risky given the lack of stone steps and the abrupt fall to the foreshore.

Sticking out from the ground, a short distance away from the wall, are two lengths of wood with a metal pole between, They are angled towards the top of the stairs, and give a clue to what was here.

The following photo from the LMA Collage archive shows King Henry’s Stairs in 1971, and explains the wooden remains. There were once a full set of wooden steps leading from the top of the wall down to the foreshore.

There is no indication of the age of the steps in the 1971 photo, however they look in reasonably good condition, and provide a safe route down to the foreshore. There is just under 50 years between the above photo and my photos, which shows the power of the Thames to erode and decay wooden structures. Daily tides, the continual immersion in water followed by exposure to the air and sunlight has reduced these steps to the two wooden stumps we see today.

The view from the foreshore is always worth it. A smooth layer of sand / mud covered in the tide worn remains of London brick, stone, and the lumps of chalk used to provide a smooth base for barges and lighters.

The algae covered walls show the height of the tide, and the old warehouses stare out on a very different Thames to when they were built.

The view looking to the west, towards central London:

The view to the east, with the towers of the Isle of Dogs behind the Wapping Pier:

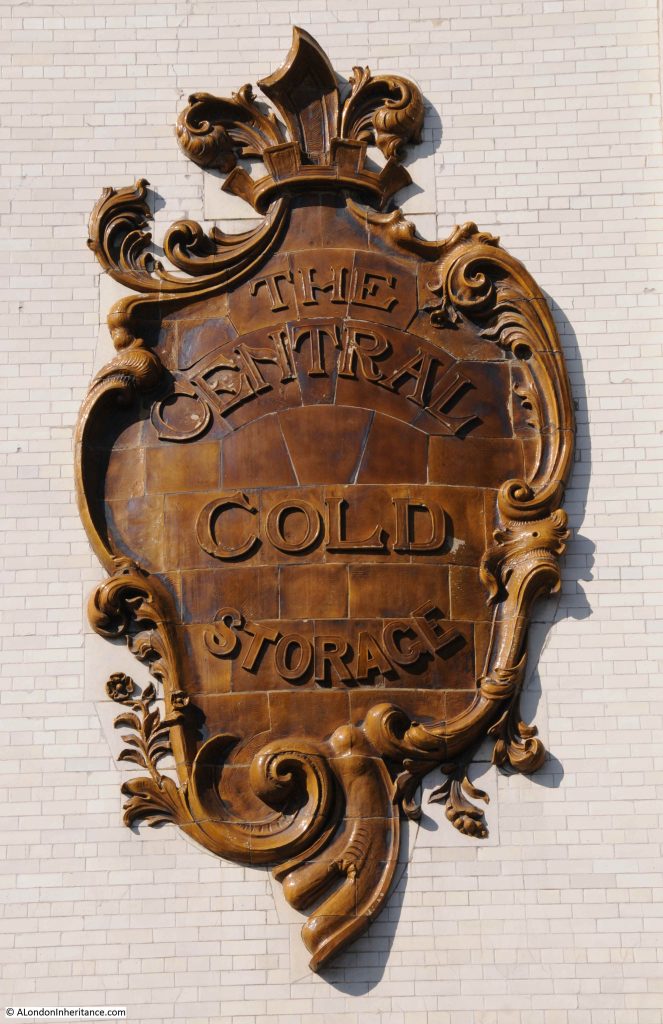

The building on the eastern side of King Henry’s Stairs is King Henry’s Wharf:

The building probably looks much as it did when barges would be lined up on the foreshore, with the crane moving goods between barge and warehouse.

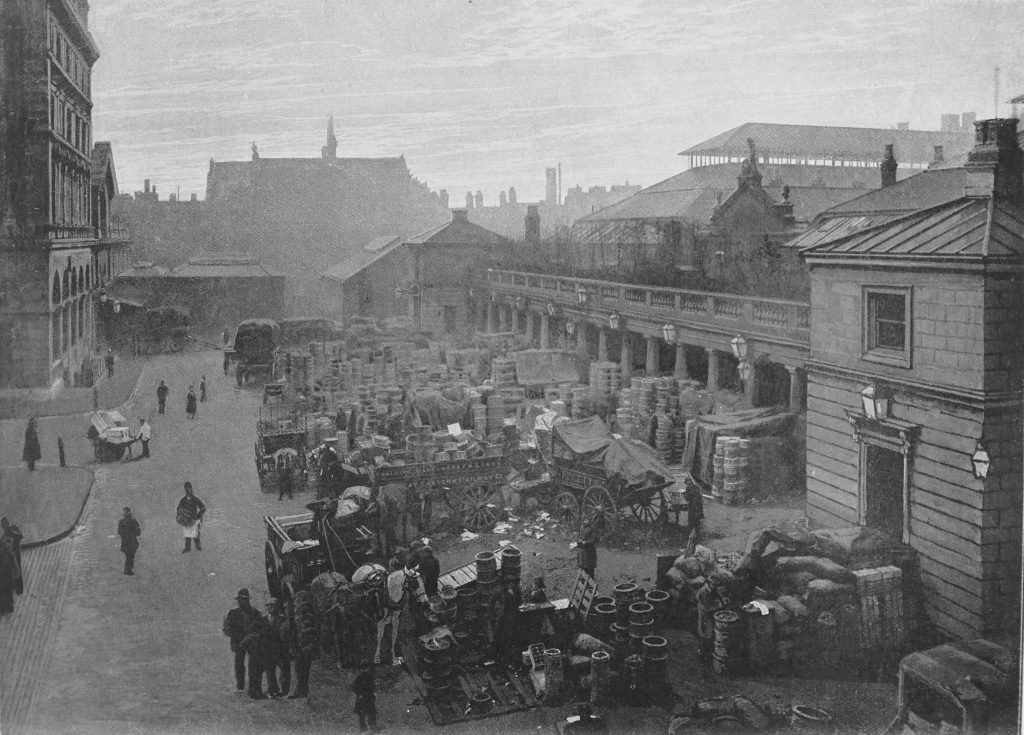

London Wharves and Docks was a directory of all the wharves and docks along the River Thames. Published by Commercial Motor. The directory provided key details for the hundreds of wharves and docks that lined the river from Teddington to Tilbury. According to the 1954 edition, King Henry’s Wharf was known as St. John’s and King Henry’s Wharves. The occupier was R.G. Hall and the building was owned by W.H.J Alexander Ltd of Leadenhall Street. The facilities included;

General, dry goods, specifically dealing with cocoa, coffee, sugar, spices, dried and canned fruit, gums and cheeses. The cranage was 60 cwt and the building provided 1,900,000 square feet of storage space. The building included customs facilities and bonding, an examination floor and sufferance. The river facing side of the building had space for barge berths and the depth of water at high tide was 10 feet.

A closer view of the crane on the side of the building:

On the western side of the stairs is Phoenix Wharf. The Commercial Motor book does not have a listing for a Phoenix Wharf on Wapping High Street so I wonder if this was a name given to the building relatively recently. The small space between Phoenix Wharf and King Henry’s Stairs was Swan Wharf (the 1894 OS map does show a Phoenix Wharf, mainly as open space just to the left).

Looking back from the water’s edge. Phoenix Wharf on the left, then the open space of Swan Wharf. The walkway to Wapping Pier above. King Henry’s Stairs to the right of the walkway followed by the corner of King Henry’s Wharf.

I was puzzled by the name of the stairs and the adjacent building – why King Henry?

The earliest use of the name I could find was from 1823 when on the 8th November the London Sun reported: “SINGULAR SUICIDE – on Thursday morning, about two o-clock, a Gentleman went to a waterman plying at King Henry’s Stairs, and asked him to take him across the river in his boat, which he instantly got into, and the waterman proceeded with his passenger. When they had nearly reached the middle of the river, the stranger took off his hat, and in a moment threw himself overboard, after which he was never seen. There is no name in the hat, nor anything that can lead to a discovery of this unfortunate man”.

Newspapers of the later 19th century offered a clue as to the source of the name when they referred to the stairs, for example in the Shipping and Mercantile Gazette on the 7th July 1840, there is an article about a new pier being erected here, and the article states “King Henry’s Stairs, where in ancient times, the monarchs of England landed and embarked”.

What I do not understand is why monarchs of England would have embarked using these stairs in Wapping, in whenever “ancient times” were. As far as I know, there was no establishment or activities such as hunting on this side of the river that would have attracted a monarch, and there were far safer places towards the City for boarding boats.

The same newspaper article also provides an alternate name for the stairs by stating that they were: “commonly called Execution Dock”. I found this to be a recurring reference in 19th century newspaper reports that King Henry’s Stairs were formerly known as Execution Dock.

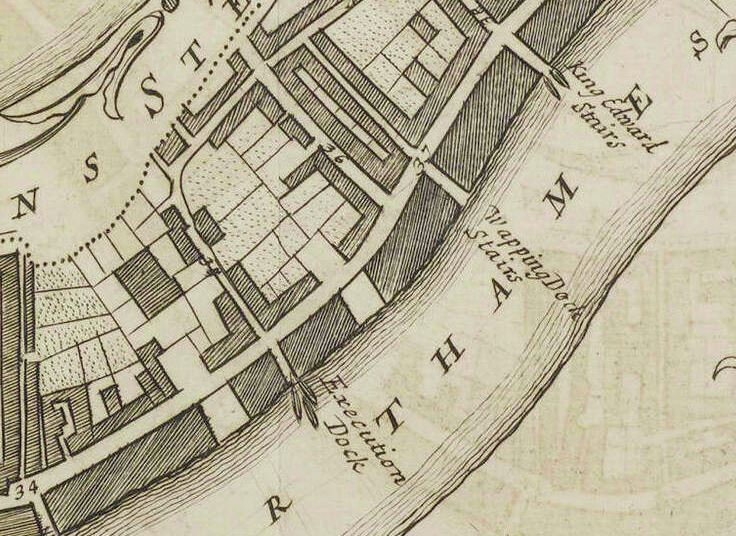

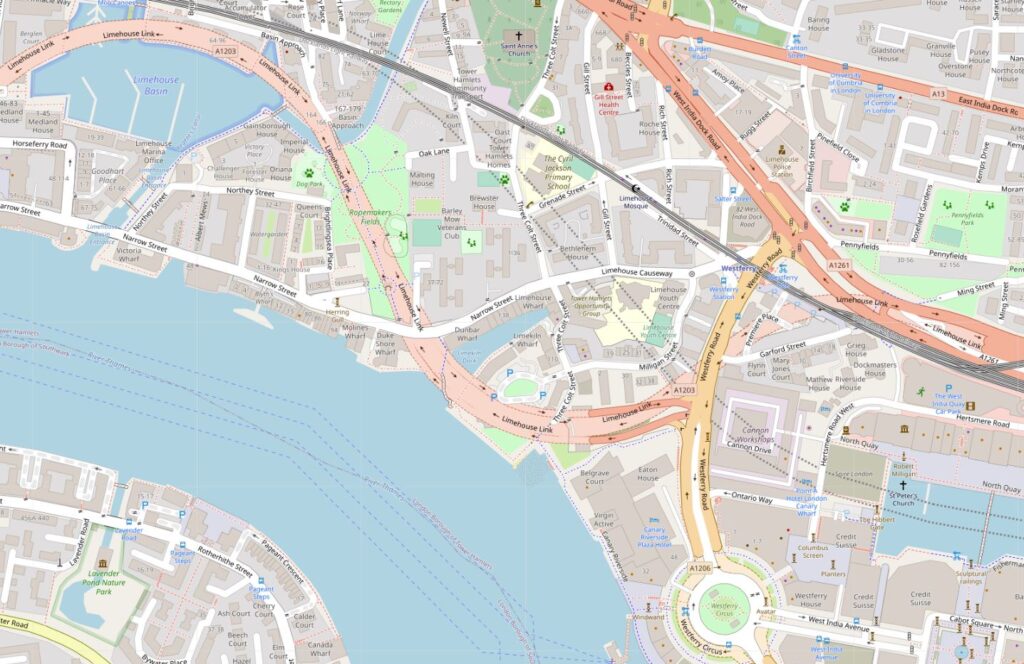

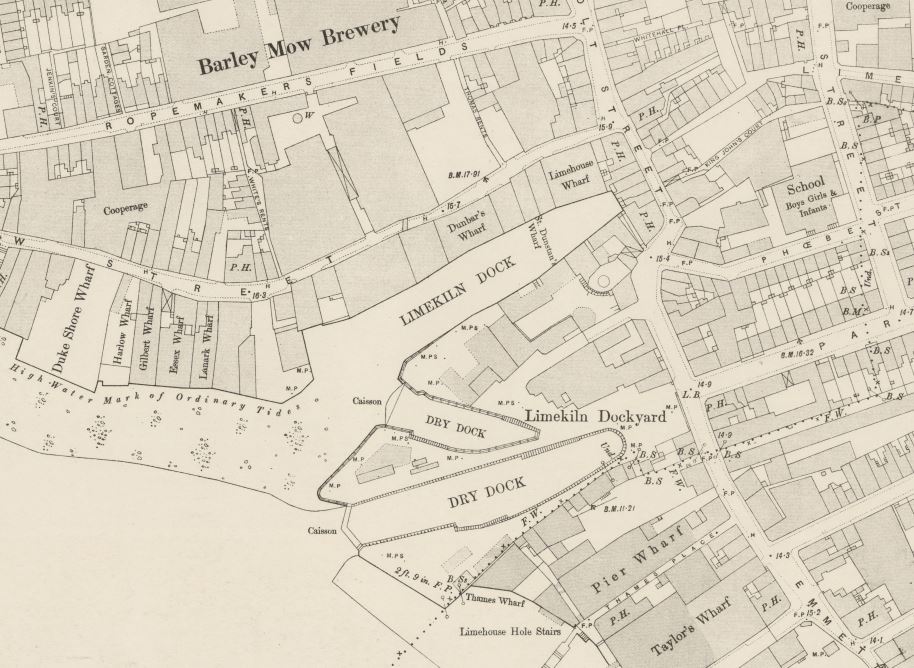

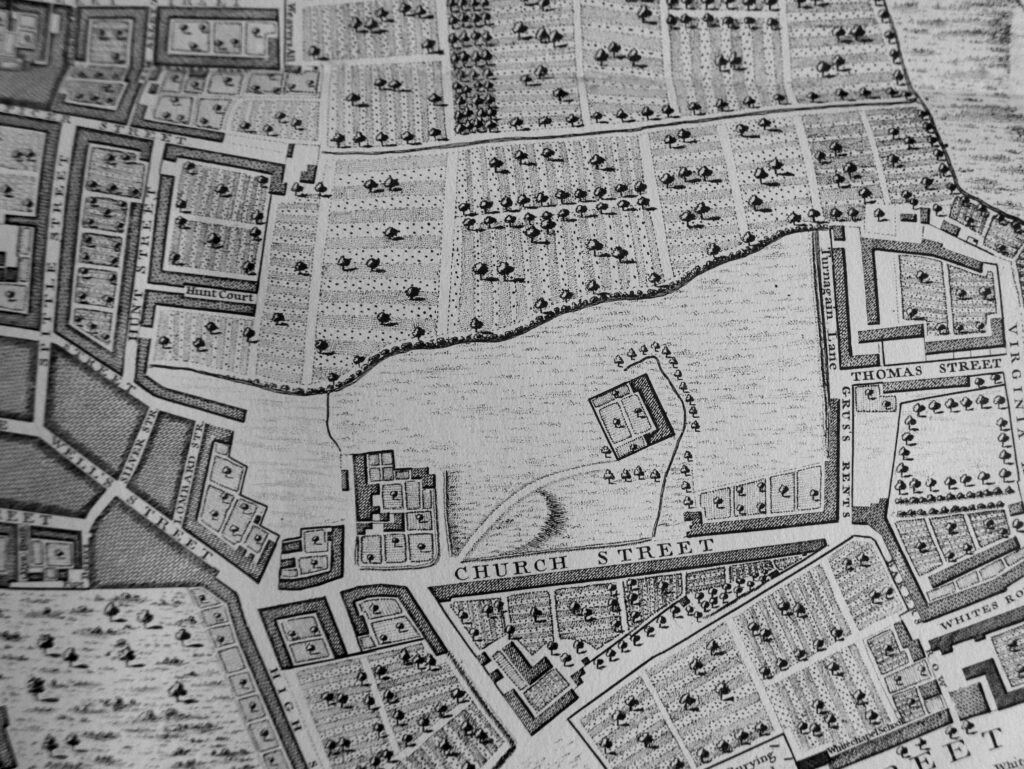

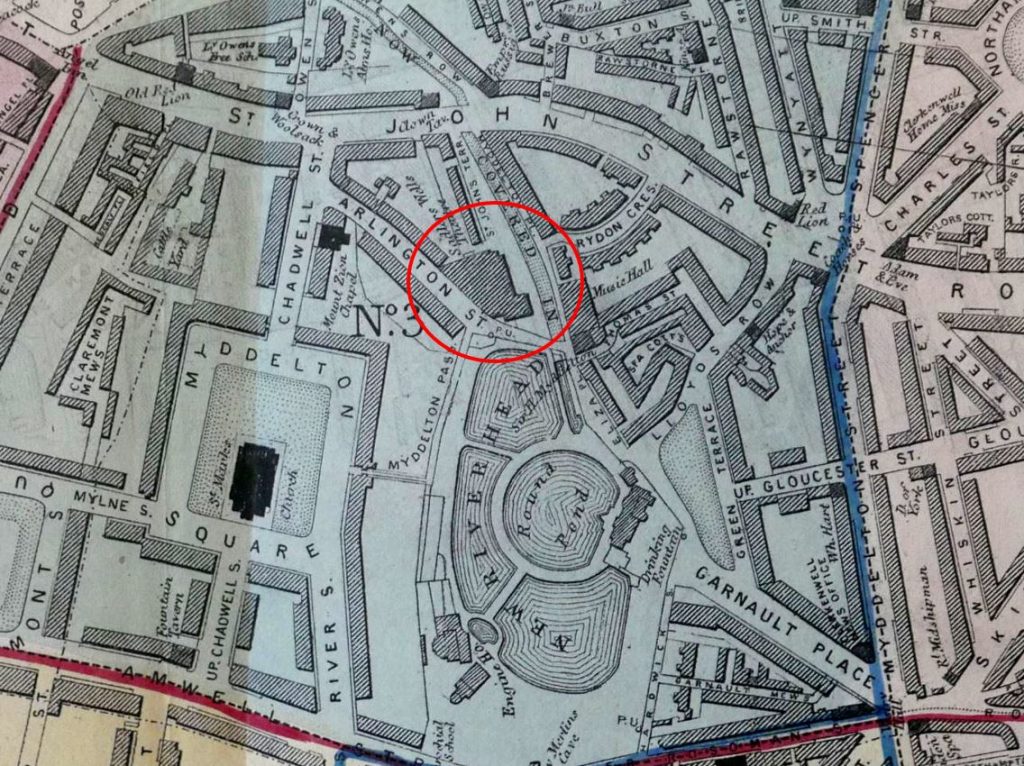

I checked Rocque’s map of 1746 for help, and in the location of King Henry’s Stairs was the name Execution Dock Stairs (in the middle of the map with the name extending out between ships on the river).

To confirm that this was the same location, comparing 2020 and 1746 maps confirms some streets in exactly the right location.

The stairs are off the road Wapping High Street (2020) and Wapping Dock (1746), but opposite where these stairs join this road, is a street with the same name and shape on both 1746 and 2020 – Brewhouse Lane. Compare Rocque’s map above with the 2020 map below:

Execution Dock is used for the name of the stairs in all early maps, always at the same location as King Henry’s Stairs.

The following maps all show Execution Dock at the same location: C. and J. Green (1828), R. Harwood (1799), William Morgan (1682). See the Layers of London site to layer these maps on a contemporary map.

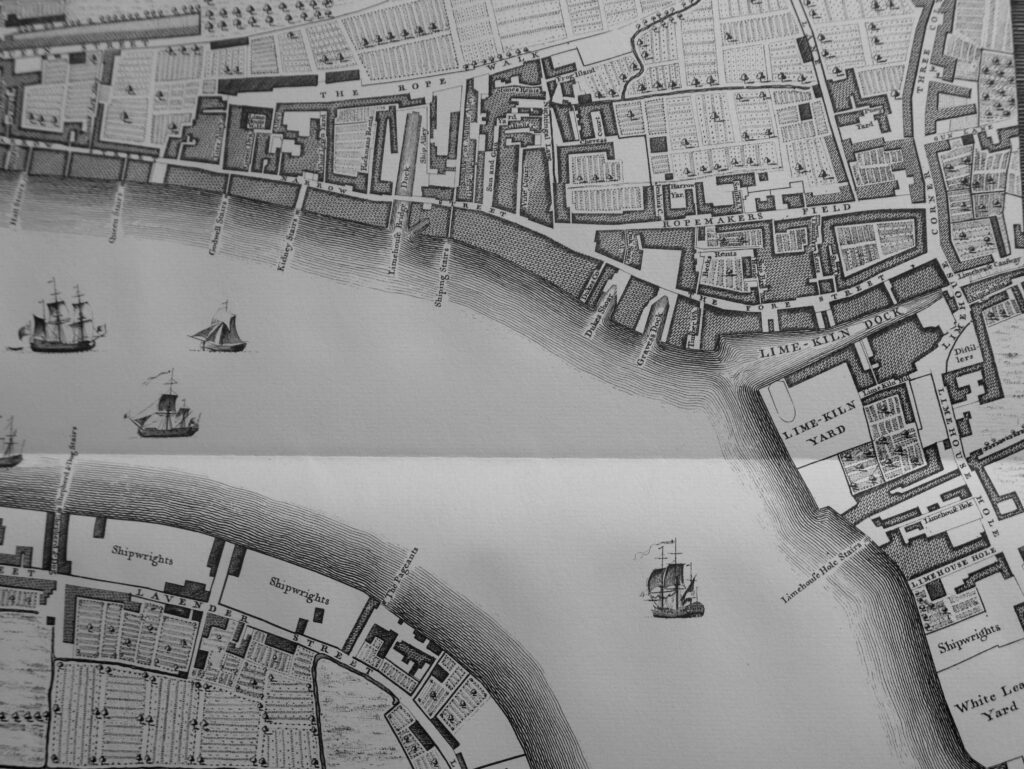

Another example is the following 1755 Parish Map. Although not named, Brewhouse Lane can be seen with the same shape as in the other maps to confirm the location. What I like about this map is that three boats are shown clustered around Execution Dock. This was to show (as confirmed by the earlier newspaper article) that these were stairs where watermen were stationed ready to take a passenger along the river.

Execution Dock probably needs no introduction – it was the place where those found guilty of crimes at sea when the death sentence was imposed, were taken to be hung.

There was a considerable number of executions here, I have been trawling through records compiling a spreadsheet of dates, names and convictions (yes seriously) but ran out of time to complete for this post, however some example are worth examining to get an idea of the crimes and how the convictions were carried out.

Being executed at Execution Dock was a major spectacle. The authorities probably encouraged this so that “justice was seen to be done”, and it would also act as a major deterrent to those considering similar crimes.

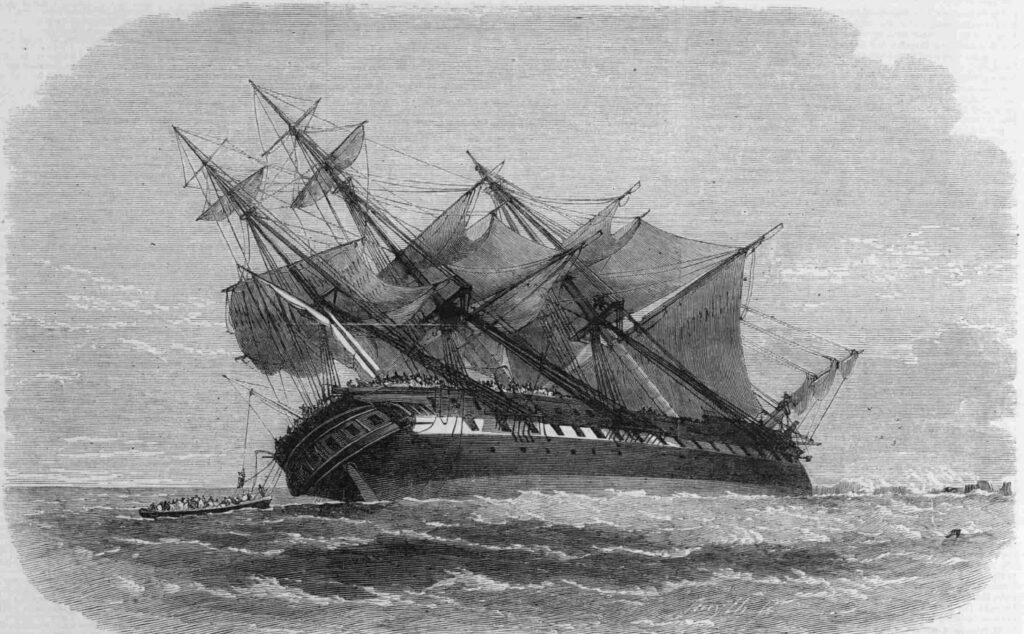

Most references to Execution Dock refer to the crime of Piracy, however you could also be executed there for many other crimes, including Insurance Fraud, such was the fate of one Captain William Codling in 1802.

Captain Codling was on trial for “sinking a ship and cargo with intent to defraud the Underwriters”. It appears that his ship, the Adventure, should have been carrying a quantity of silver, however he had hidden this onshore, and when off Brighton, made holes in the hull of the ship causing her to sink. He and a couple of accomplices could then keep the silver and claim on the insurance – a crime that in 1802 was “an Offence most justly rendered Capital by Statute”.

Captain Codling was found guilt and handed the death sentence. The London Star on the 29th November 1802 carried a detailed account of the execution at Execution Dock:

He was executed on Saturday 27th November and between trial and execution was held at Newgate where since the Friday evening he had been “in solemn devotion and prayer, preparatory to his fatal exit”. His main regret was separation from his wife Jane and his son aged nine.

His wife Jane had traveled to Windsor to try and obtain a pardon from the King, but was not successful, arriving back at Newgate early on Saturday morning, without any success. He had a nephew who assured him that he would look after his wife and son. He appears to have been resigned to his fate, and his main concern was consoling his wife when she returned to the prison:

“The tender scene which now followed would require the pen of the most pathetic writer. The prisoner conducted himself with manly fortitude, and used every argument to console his wife, begging that she would suppress her grief, for that it affected him much more than his own unhappy fate. After some mutual endearments, she became more tranquil, and when they passed about an hour together, Dr Ford, the Ordinary of Newgate, entered, and advised Mrs. Codling to take her last farewell of her husband; Captain Codling himself joined in the request. Any description of their parting scene would appear a mockery of such real woe”.

The article also provided details on the procession that assembled to take Captain Codling from Newgate to Execution Dock. When reading this, consider that this was to guard someone convicted of insurance fraud and was accepting of their fate. The procession was as it was to show the power of the state, the law and judiciary and to act as a very strong deterrent:

“The cart was drawn up by two horses, a board nailed across for a seat, and another as a back to it. The Deputy Marshal was on horseback arranging the constables. Messrs Canner and Holdsworth (the two City Marshals) were likewise on horseback, with their staffs in their hands. A few minutes before nine o’clock the Marshal of the Admiralty arrived in his carriage, with two footmen behind, and the two Sheriffs were next in their carriages. The Rev. Dr. Ford, the Ordinary, followed in his carriage. There were about fourteen of the Sheriffs’ men on horseback to guard the prisoner, whilst the number of constables, all on foot, was about two hundred. Just as St Sepulchre’s clock struck nine, the executioner and his men came out with a pair of steps, which placing them in the back of the cart, they were both ascended. The Under Sheriff, came out with the death warrant in his hand, which he delivered to the Deputy Marshal. he then returned to the prison, and again appeared. conducting the unhappy Captain Codling to the cart and assisting him up the steps.

The mob, which had been collecting for some hours was now immense. the street, lamp-posts, windows and the roofs of the houses, were wonderfully crowded“.

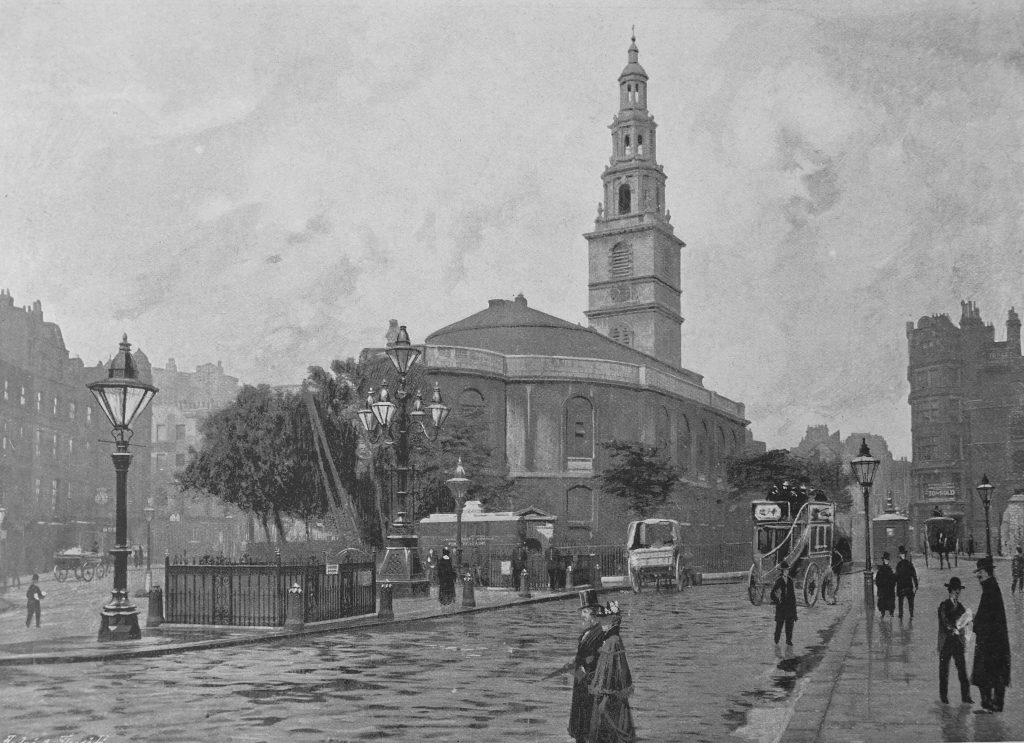

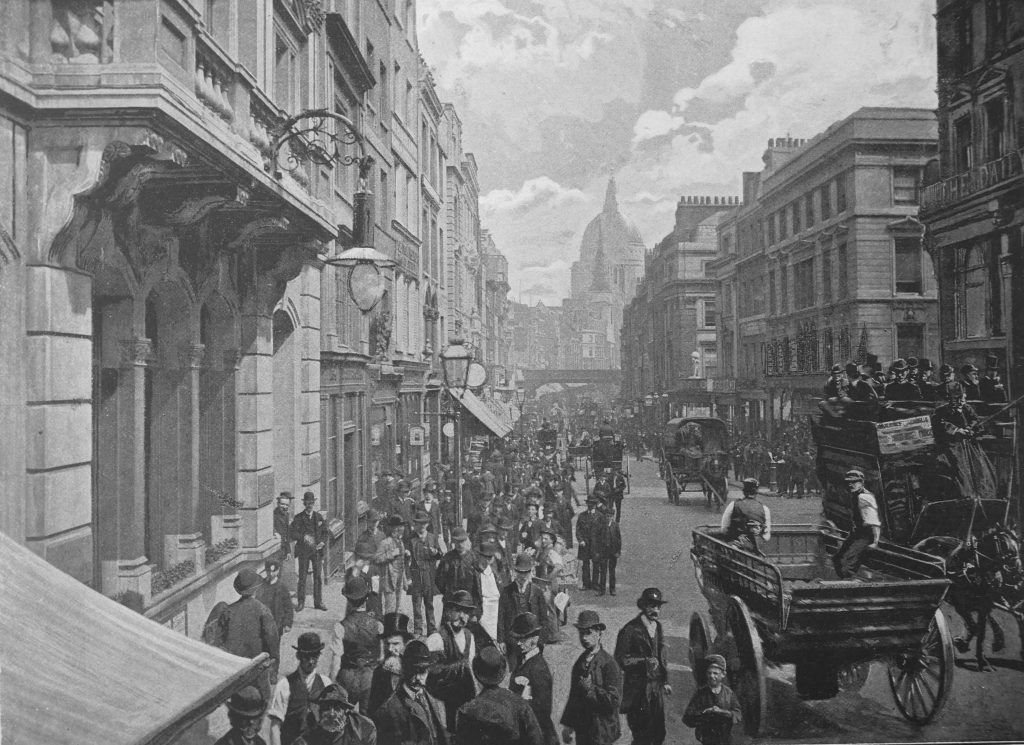

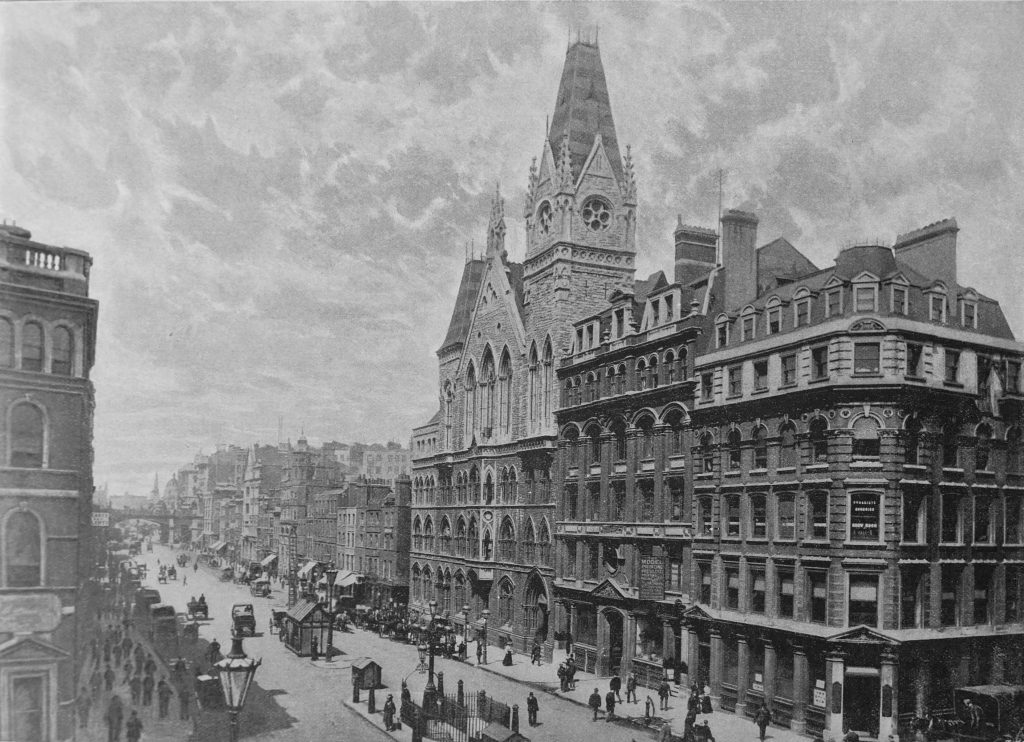

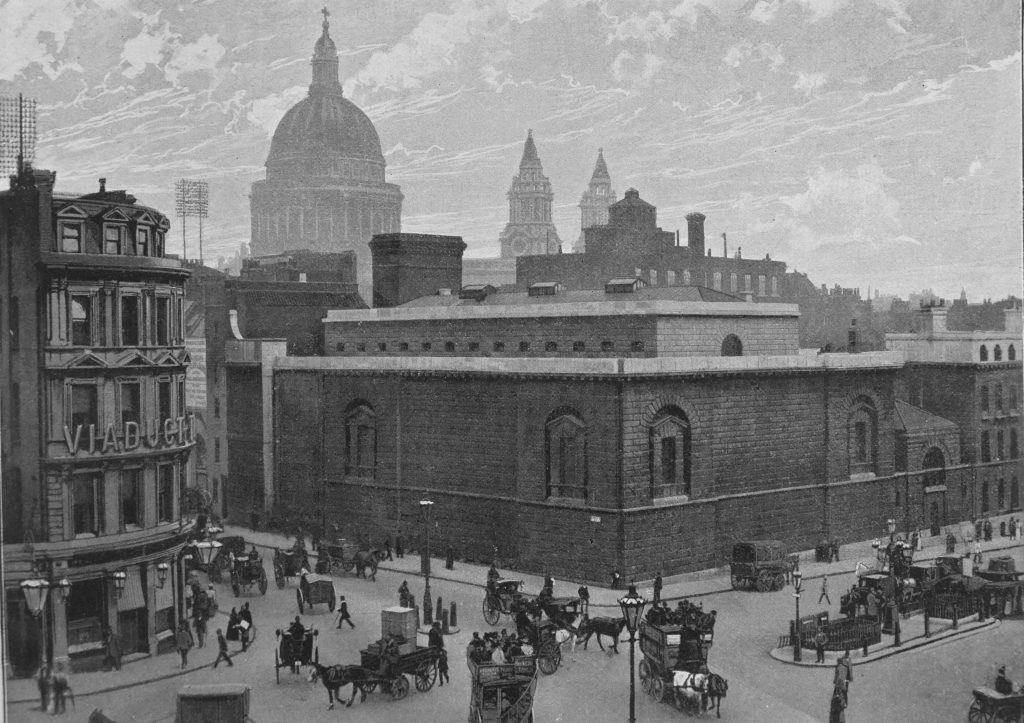

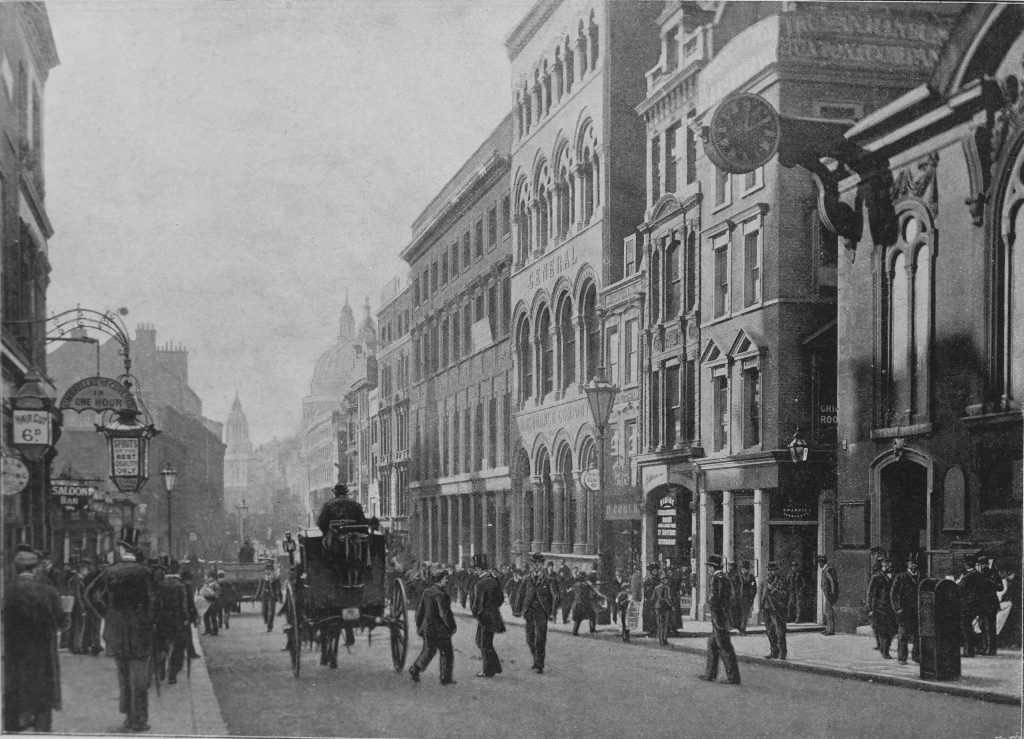

The route taken from Newgate prison was along Ludgate Steet, passing St Paul’s Churchyard, , Cheapside, Leadenhall Street, High Street, Whitechapel, then down Gravel Lane and along to Execution Dock, where the procession arrived at half past ten. The cart was backed up the alley to the stairs.

The crowds in the City were recorded as being larger than for a Lord Mayor’s show. It was market day in Whitechapel, which caused problems getting through the crowds, and along Gravel Lane “the crowd was so great, and the street so narrow, that they were obliged to move very slowly and with great precaution”.

The gallows had been erected about ten to twelve paces from low water mark. Planks had been placed on the mud on which the officials could stand. Then at twenty minutes before eleven, on a signal from the Sheriff “the board was knocked from under his feet, and he was launched into eternity”.

Unfortunately with this method of execution, the end was not so quick. Although he was a weighty man, Captain Codling “struggled hard for three or four minutes”. After being left for a further fifteen minutes, he was taken down, covered with a black cloth, and his body was put into a boat to be taken away.

Captain Codling was described as “a stout well-made man, about 45 years of age – the complexion of a man used to the sea – very pleasing and affable in his manner; and prior to this, bore an extreme good character. he was dressed in double breasted blue coat, with guilt buttons and black collar”.

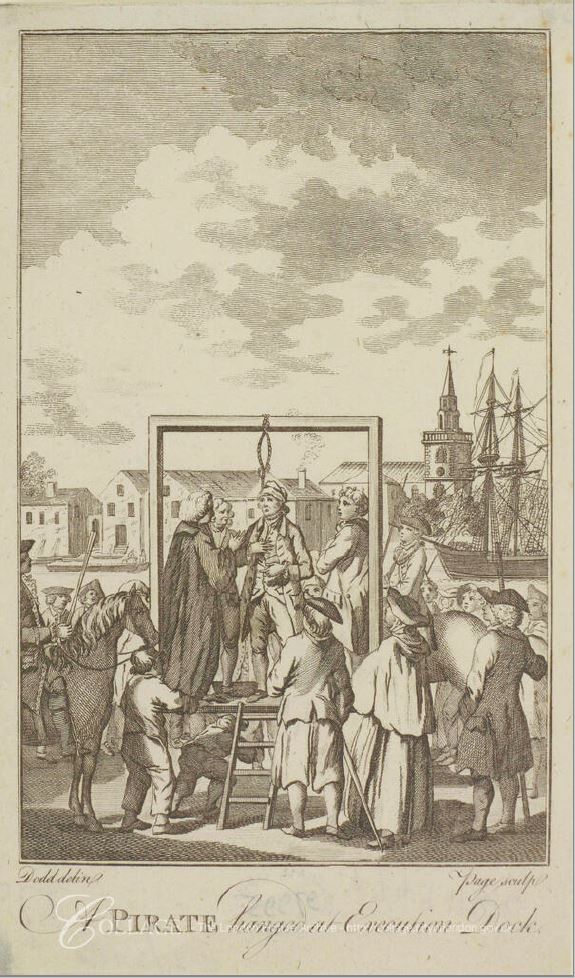

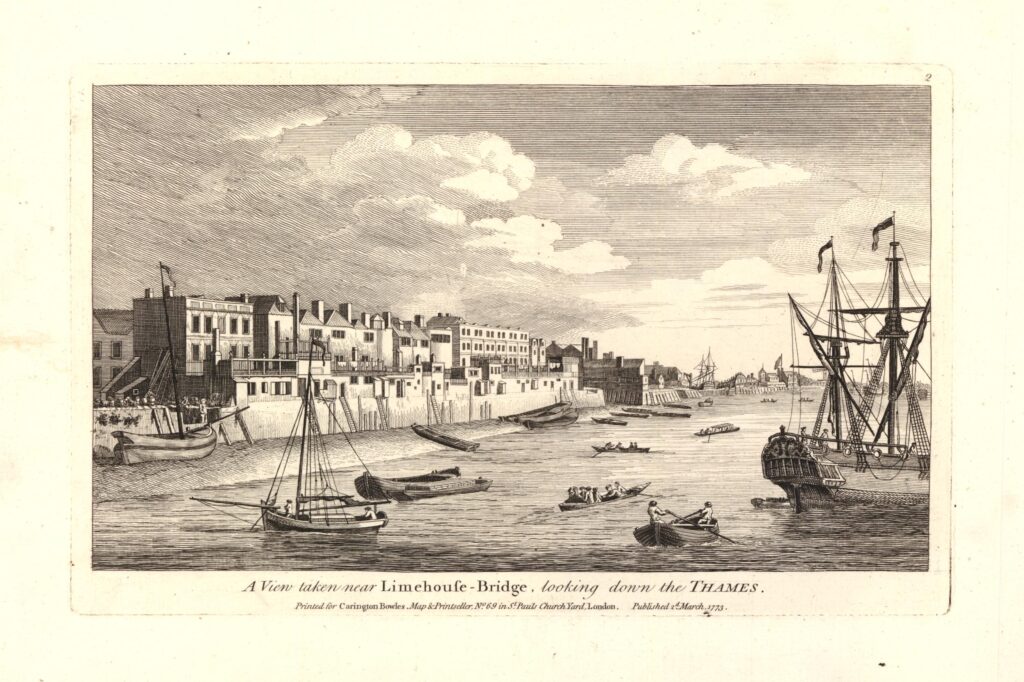

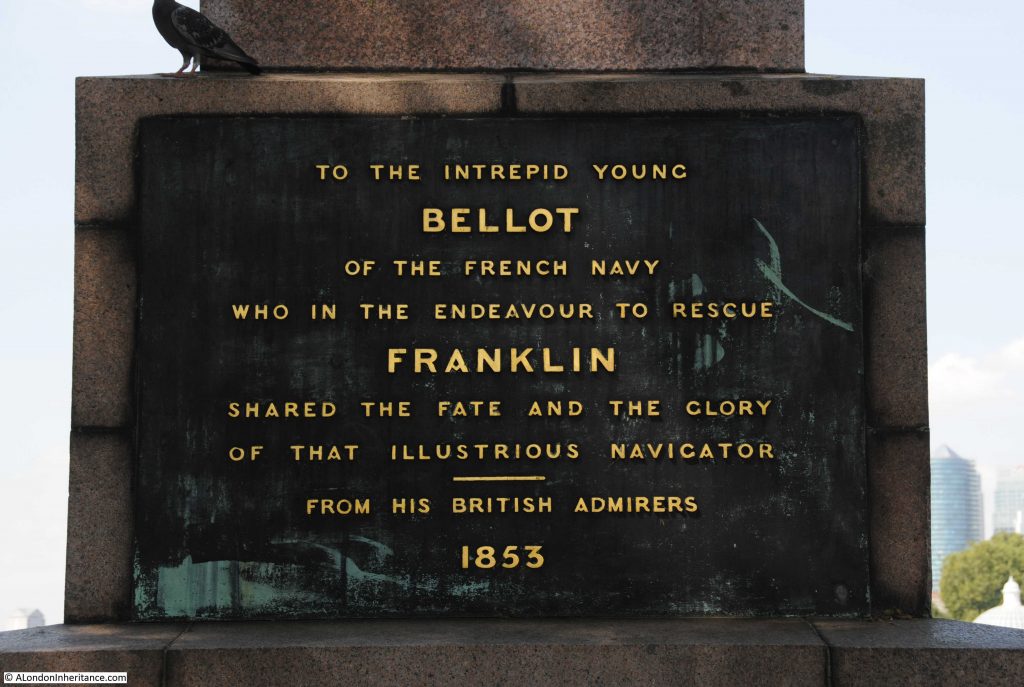

A print of an execution at Execution Dock in 1795, seven years before Captain William Codling, so probably very similar.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: p7491142

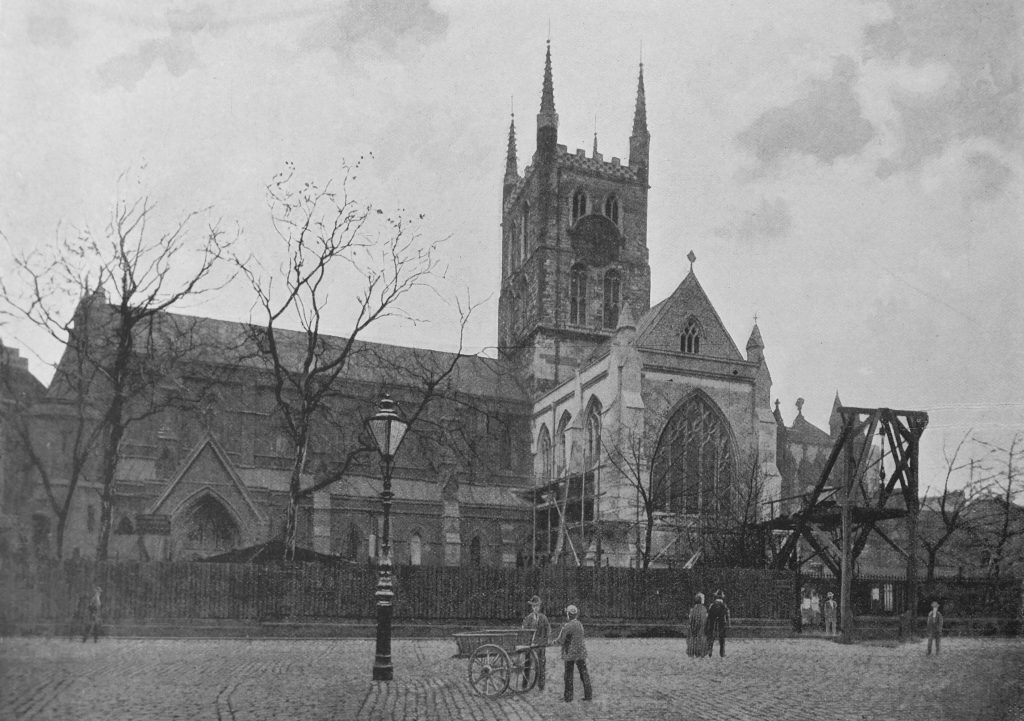

To the rear of the above print is a church tower. This is the tower of St Mary, Rotherhithe.

Unfortunately, Wapping Pier obscures the view of the church today from King Henry’s Stairs:

I took the following photo a little to the west of King Henry’s Stairs, the location of the stairs is marked by the red arrow. The church tower can be seen on the opposite bank.

Executions at Execution Dock covered many different crimes, the common factor being that the crimes happened at sea:

- May 1701, Captain William Kidd was hung for piracy and murder and his body hung in chains off Tilbury

- March 1734, the pirate Williams was executed and his body left to hang in chains

- March 1737, four unnamed pirates were hung on the same day and left in chains

- For the worst offences, the bodies of those executed would be left hanging from the gallows, or their bodies would be left in a cage for the tide to pass over them. Penalties were severe for anyone removing a body. In January 1739, a reward of £100 was being offered for information on who cut down and removed the body of James Buchanan

- in January 1743, Thomas Rounce, who had been convicted for high treason by fighting against his King and country in a Spanish privateer was hung, drawn and quartered at Execution Dock

- December 1781, William Payne, Matthew Knight and James Sweetman were hung after being convicted of Felony and piracy on the high seas. The bodies of Knight and Sweetman were hung in chains at Execution Dock, however the town of Yarmouth had applied to the Admiralty for the body of Payne, so it could be hung in chains on the coast at Yarmouth as a deterrent

- In July 1800, James Wilson was executed after being convicted of fighting against his country, on board a French privateer

- In July 1806, Akow ” a tartar” was executed for the willful murder of one of his countrymen on board the Travers, an East indiaman, on the high seas

- In June 1809, Captain J. Sutherland was executed after being convicted of murdering his cabin boy – a crime of which he was protesting his innocence all the way to the gallows

Some of the crimes which carried a sentence of death seem relatively trivial. In December 1769, six “pirates” were hung in one day at Execution Dock. Edward Pinnel was hung for sinking and destroying a merchant ship, the five others; Thomas Ailsbre, Samuel Ailsbre, William Grearey, William Wenham and Rchard Hide were sentenced to death for entering a Dutch ship two leagues from Beachy Head and stealing sixty hats.

Newspaper reports of the execution of the six men provide an account from the time of how these events proceeded “They appeared very hardened and seemed totally ignorant and careless about the sudden transition they were going to make. the principal of them even wore a blue cockade in his hat, and when they arrived at the place of execution, he bow’d his neck to the halter and threw his hat among the populace. It is thought that more hardened wretches were scarce ever seen. From the great number of people that pressed to see the punishment of the above unhappy men, the great rails along a wharf near Execution-dock gave way, and above 60 people fell over the wharf; by which accident several of them were much bruised and one man killed”.

Executions at Execution Dock would decline in the first decades of the 19th century. The execution of George Davies and William Watts in December 1830 for the crime of piracy was recorded as being the first at Execution Dock for ten years. They would also be the last people executed on the foreshore of the River Thames.

From the 1830s onward, references to Execution Dock were for the normal occurrences at any of the Thames Stairs – accidents on boats close to the stairs, theft, boats for sale, bodies being found, problems experienced by the waterman with difficult passengers, fires and floods etc.

In the latter decades of the 19th century, references to Execution Dock turned from day to day events to historic tales of those who had been executed. I suspect that the new name of King Henry’s Stairs was gradually taking over, but it took some time as a name with the resonance of Execution Dock would take many years to be replaced in the conversations and memory of those who lived and worked in Wapping.

The name change was possibly down to the growth in Victorian trade and industry along the river’s edge at Wapping. To the Victorian businessman, the area was a place to be celebrated for trade and industry, rather than looking back at the barbaric practices of the past.

There is much speculation regarding the exact location of Execution Dock. Maps dating back to 1682 show what are now King Henry’s Stairs as Execution Dock, and the location in respect to Brewhouse Lane is the same. The change in name occurs in the first half of the 19th century, with the earliest use of King Henry’s Stairs being in 1823, with the name growing in use throughout the 19th century, as use of the name Execution Dock declines.

Many sites along the Thames at Wapping have claimed to be the location of Execution Dock, for example the Prospect of Whitby pub has a noose hanging from a gallows over the foreshore at the rear of the pub:

I suspect that King Henry’s Stairs / Execution Dock was the central location for executions, but in the hundreds of years that the practice was carried out, the location shifted along the foreshore to east and west of the stairs as the mud and foreshore shifted, to move around obstructions such as moored boats, building work facing on to the river, perhaps for the more notorious executions, the need to ensure good visibility of the execution from the shore and from boats on the river also dictated the location.

It is a very different place today – the view looking east from Execution Dock. hard to image the scenes that occurred here and where poor Captain William Codling was hung for the crime of insurance fraud.

I have not been able to find out why King Henry’s Stairs was used as the name for the stairs. Were the stairs named after the adjacent King Henry Wharf, or was the wharf named after the stairs – what was here first? I need to find some detailed maps of the area around the 1820s when the name appears to have been first used.

I have not been able to find out why King Henry’s Stairs was used as the name for the stairs. Were the stairs named after the adjacent King Henry Wharf, or was the wharf named after the stairs – what was here first? I need to find some detailed maps of the area around the 1820s when the name appears to have been first used.

After leaving the foreshore, I climbed back up the ladder and stepped across to the top of the river wall, where the missing stairs should be leading down to the foreshore. I closed the gate as I headed back to Wapping High Street as if you were not too careful, and were expecting stairs, a nasty fall into the river or the foreshore could be the result – and there have been far too many deaths here over the centuries.