Last Sunday I was walking along the South Bank in 1980, for today’s post, I have crossed over the river for a walk in the City with a few of my photos, also from 1980.

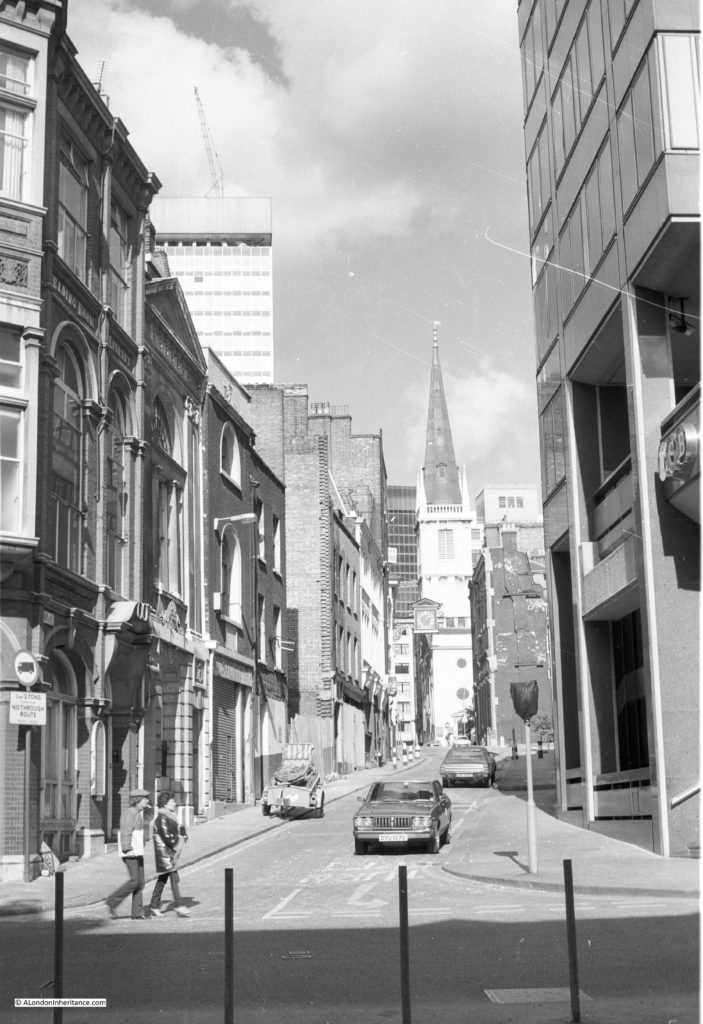

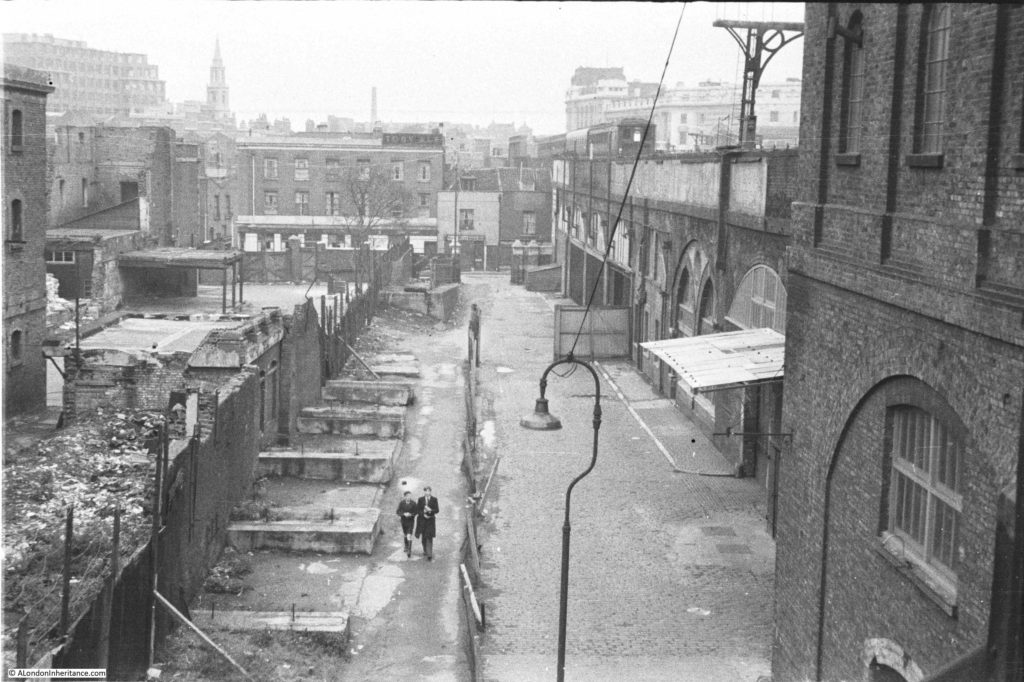

I am starting on Lower Thames Street, opposite the old Billingsgate Market. This is the view looking up the street St. Mary at Hill.

This is the same view 39 years later in 2019:

The street is named after the church on the street, however it is not the church which can be seen in the distance – that is the church of St. Margaret Pattens which is across East Cheap which runs along the top of St. Mary at Hill.

The church after which the street is named is where the ornate clock overhangs the street. Although the street is named after the church, the tower and main entrance to St. Mary at Hill are on Lovat Lane. I visit the church in this post.

In 1980, the area around the street of St. Mary at Hill was still dominated by the Billingsgate fish market, which would not move from Lower Thames Street until 1982. The street still had some open spaces which had not yet been redeveloped following wartime damage, however the financial industry was expanding into the area as show by the relatively new TSB building on the right in the 1982 photo.

If you look at the 1980 photo above, a short distance along St. Mary at Hill on the left, by the trailer, half on the street, there is a shop with a plaque above the shop front.

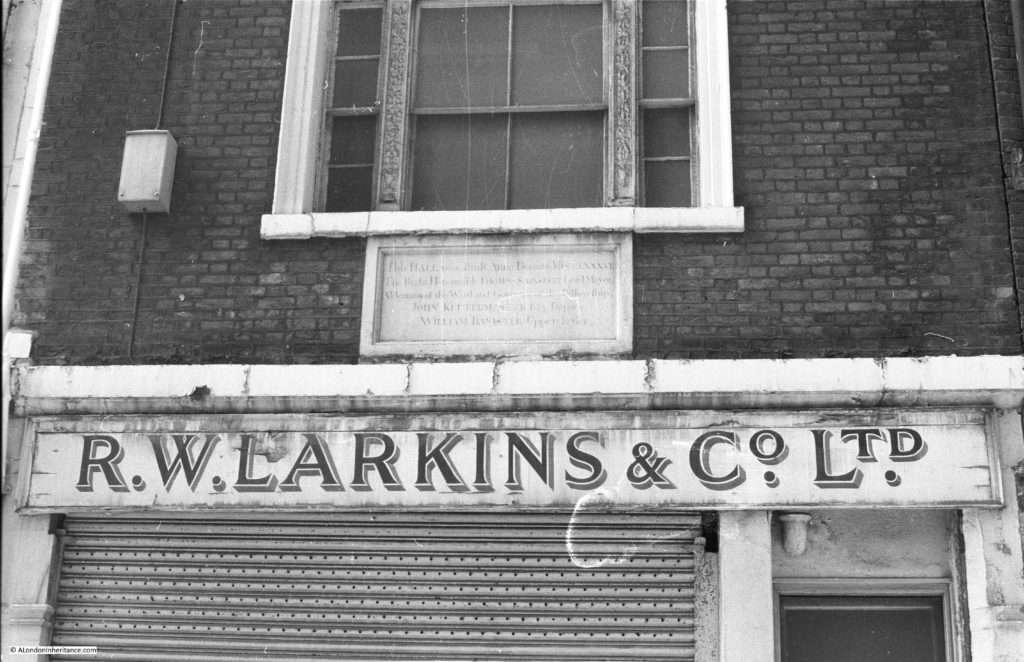

In 1980 I photographed the plaque:

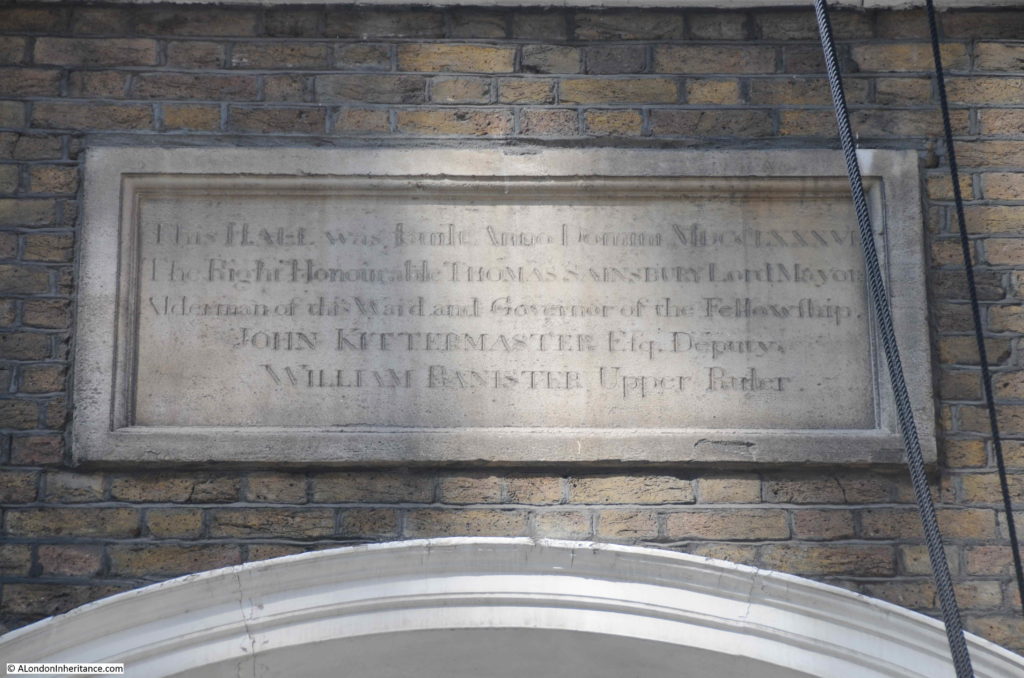

In 2019, the plaque is on the same building, but has been relocated from above the first, to above the second floor window.

The ground floor is no longer a shop.

The plaque reads:

“This Hall was built Anno Domini MDCCLXXXVI The Right Honourable Thomas Sainsbury, Lord Mayor, Alderman of this Ward and Governor of the Fellowship. John Kittermaster, Deputy. William Banister, Upper Ruler.”

The building is part of Watermen’s Hall – the City hall of the Company of Watermen and Lightermen of the River Thames.

The main hall building is immediately to the left. The ground floor with the old shop was redeveloped as part of the hall complex in 1983.

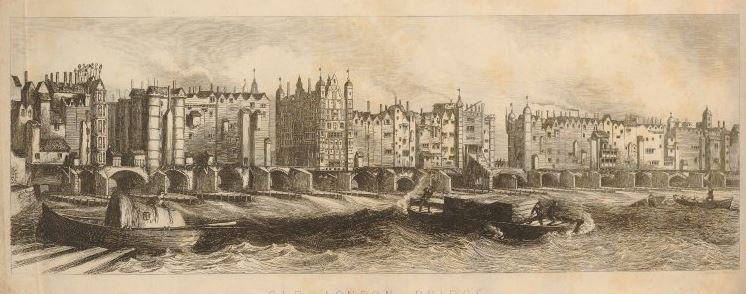

The Worshipful Company of Watermen and Lightermen has its origins in an Act dating from 1555 when a form of licensing was introduced for watermen on the river between Gravesend and Windsor. The aim of licensing was to ensure a standard rate of fares for customers of watermen, rather than the free for all and often extortionate fares that had been charged.

Eight Watermen were appointed each year by the Mayor, and they had the responsibility to ensure the rules of the act were being carried out.

Lightermen were included with the watermen by an Act of Parliament in 1700, and in 1827 the company was incorporated as the Master, Wardens and Commonality of the Watermen and Lightermen.

The scope of the Company’s authority was reduced in 1859 when the western limit was moved from Windsor to Teddington (the tidal limit of the Thames), and in 1908 the licensing powers of the Company were transferred to the Port of London Authority.

The Company did not have Masters until 1827, prior to 1827 the company was administered by Governor, Deputy and Rulers – hence the titles used on the plaque.

The Armorial Bearings of the Company of Watermen and Lightermen on a rather lovely door knocker on the door of the building that in 1980 was occupied by the shop.

The main Hall dates from around 1780 (the plaque dates the building of the hall to 1786), and is the only original Georgian Hall in the City of London.

Armorial Bearings on the front of the Hall:

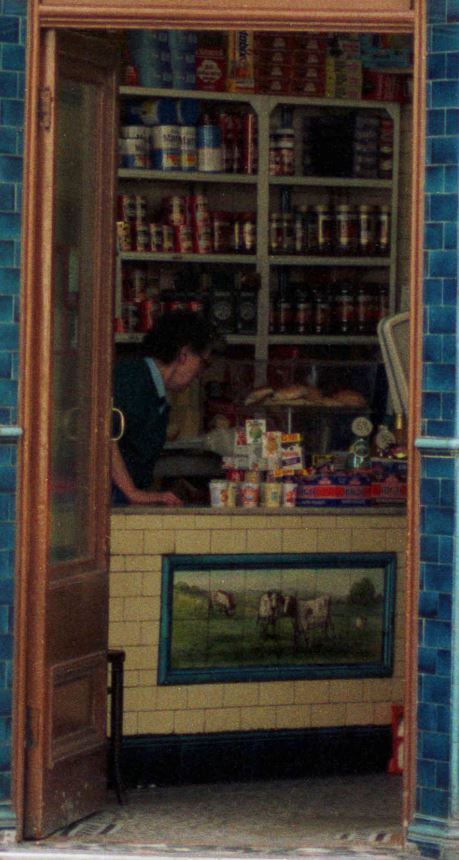

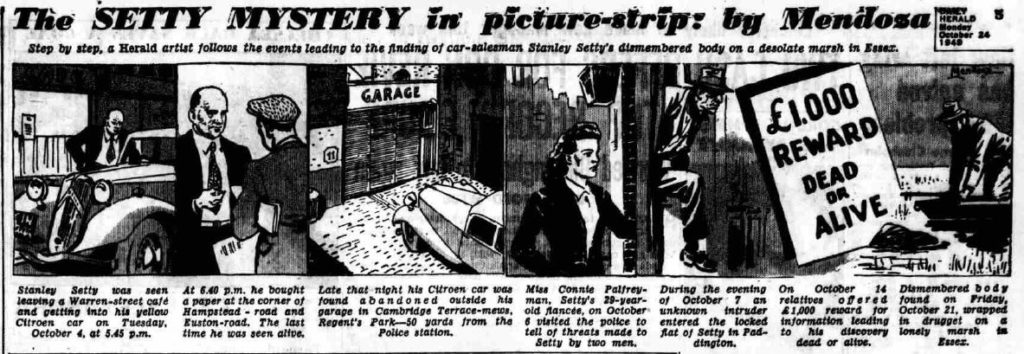

Across Lower Thames Street and St. Mary at Hill is Billingsgate Market:

This was still a working market in 1980 when I took these photos. I have more photos on another film which I have not scanned yet, but on this film I photographed some of the barrows by the side of the market.

And the space to the right of Billingsgate Market which was used by vehicles carrying goods to and from the market. Unlike earlier years, Lower Thames Street was a major east – west route across the City so could not be blocked by market vehicles. The space provided a good view across the river – the tower of Southwark Cathedral can be seen on the right.

This is roughly the same view today as the above photo. The space has been occupied for many years by office blocks.

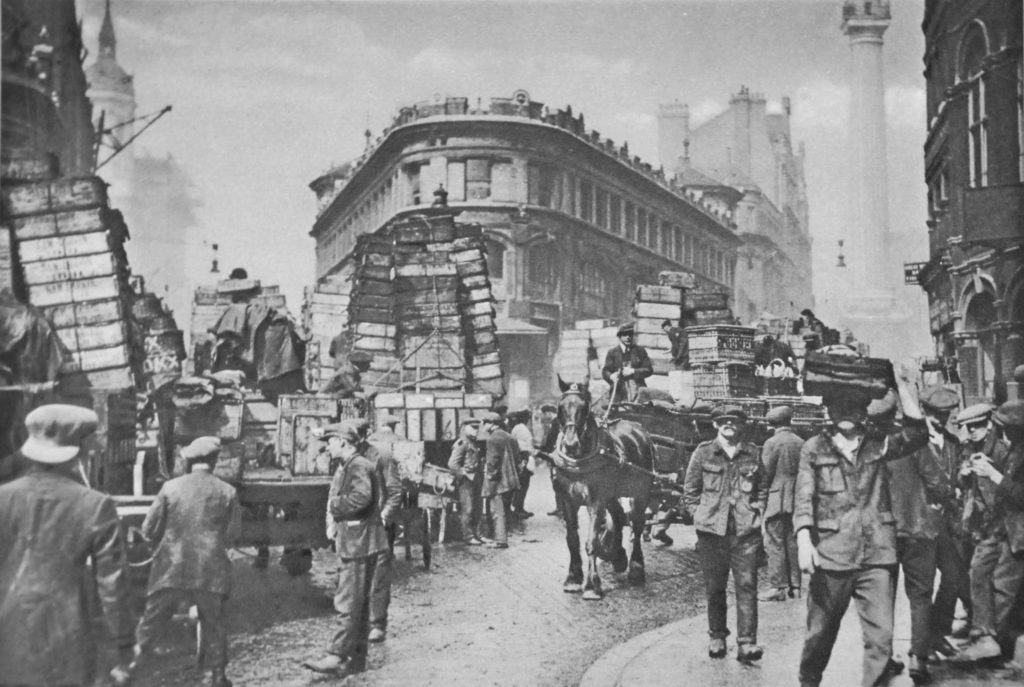

I want to include my next 1980 photo in a time sequence of photos showing the area outside Billingsgate Market, looking along Lower Thames Street and up Monument Street towards the monument to the Great Fire of London.

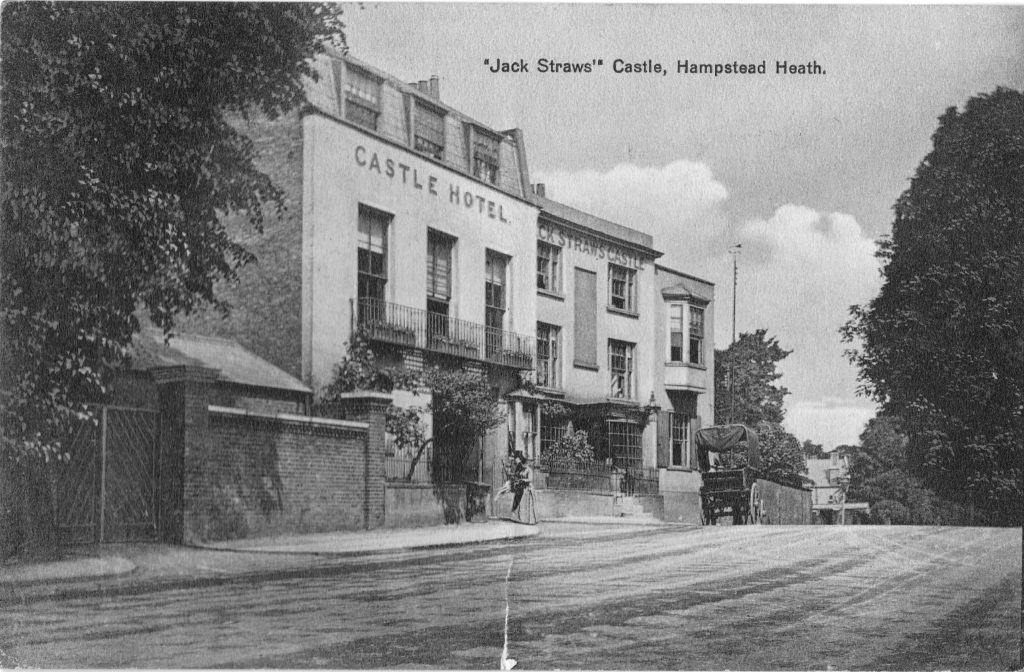

The first is from the book Wonderful London:

The second is my father’s photo taken in 1949 (the majority of the buildings are the same as in the Wonderful London photo):

My photo from 1980:

And my latest photo from April 2019:

This is an area that has changed significantly, both in the trades and business that occupy the area as well as the architecture that also has to change to accommodate the business of this part of the City.

In my father’s 1949 photo there is a rather ornate entrance on the right of the photo. This was the Coal Exchange and is shown in more detail in my post on Lower Thames Street and the view to the Tower of London.

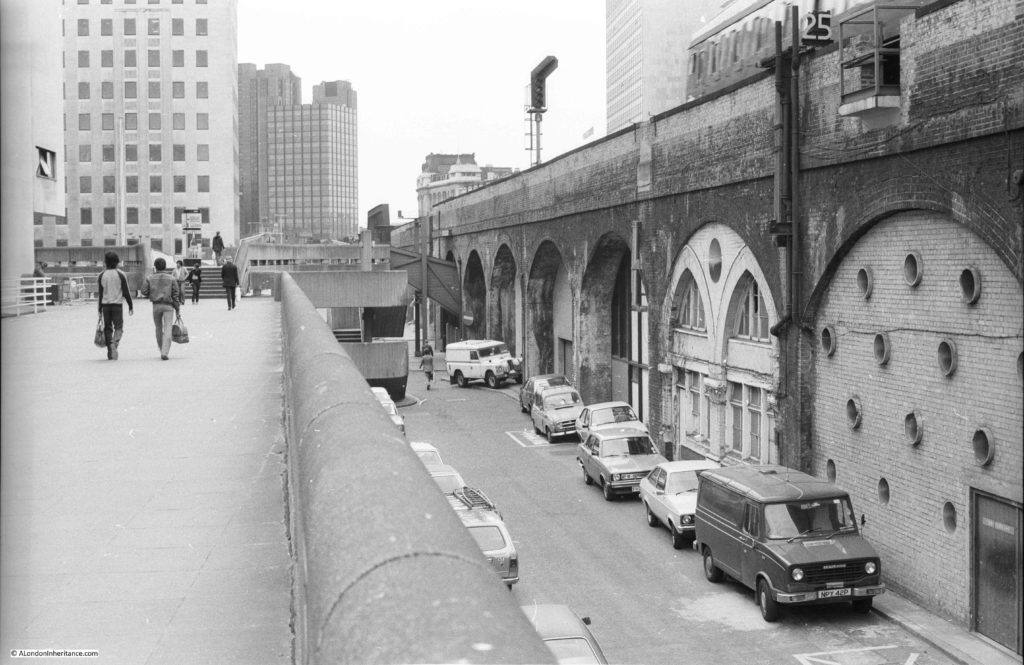

To get to my next location, I walked west along Lower Thames Street and continued along the street as it changes name to Upper Thames Street.

It was across Upper Thames Street, from Broken Wharf, that in 1980 I photographed the solitary tower of St Margaret Somerset.

The same view today:

On first view, it may be thought that the tower of the church remains as the rest of the church was bombed in the last war, however St. Mary Somerset was the victim of population changes in the 19th century when the church was included in an 1860 Act of Parliament that allowed the demolition of a number of City churches.

The 19th century architect Ewan Christian campaigned for the tower to be preserved, so the tower is the only survivor of Wren’s post Great Fire of London rebuild of the church.

A church has long been on the site. In the 1917 publication London Churches Before The Great Fire, Wilberforce Jenkins describes the church:

“The Church of St. Mary Somerset, or Summers Hythe, was near Broken Wharf, on the north side of Thames Street. William Swansey is mentioned as rector in 1335, but the church must have been much older than the fourteenth century. In a deed of the twelfth century mention is made of a certain Ernald the priest of S. Mary Sumerset.

The church was burnt down in the Fire and rebuilt, the parish of St. Mary Mounthaunt being annexed. Nothing remains of the rebuilt church except the tower. A small piece of the churchyard may be seen fenced in.”

In 1980 my photo shows a clear view of the tower from across Upper Thames Street however today, as part of the later 1980s building over Upper Thames Street, the view is now significantly obscured by building that covers over Upper Thames Street.

It is at this point that Upper Thames Street passes through a concrete box structure around which new buildings have been constructed. The street emerges by Puddle Dock.

Part of the small piece of churchyard mentioned in the 1917 book may still be seen today to the right of the tower.

A better view of the tower of St. Mary Somerset, and where Upper Thames Street disappears into a tunnel.

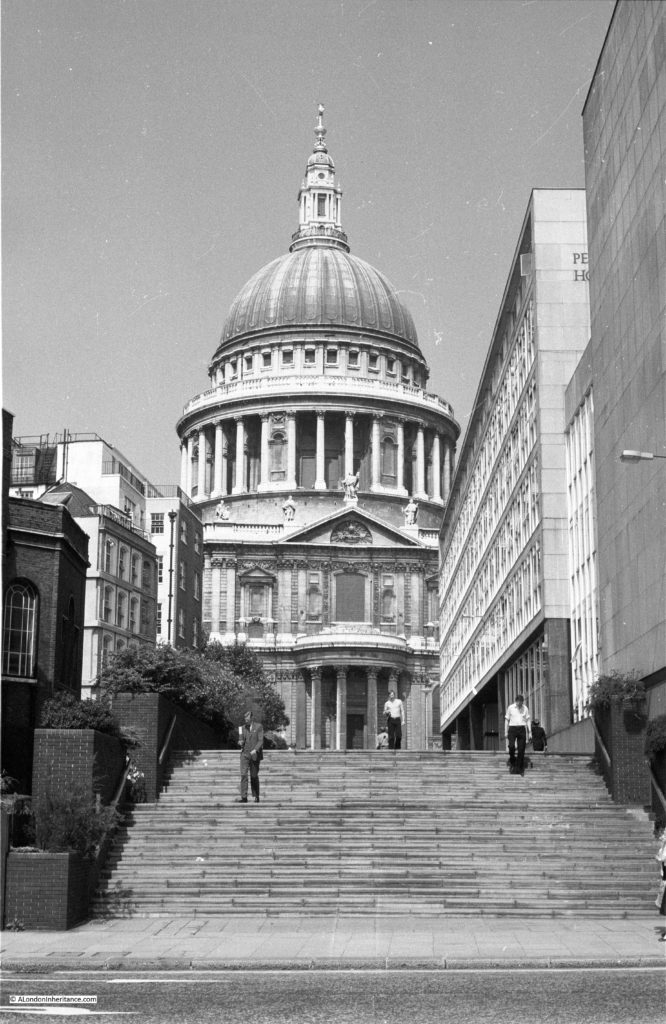

To get to my next location, I walked up to Queen Victoria Street, to where Peter’s Hill crosses the street. This was my 1980 view up to St. Paul’s Cathedral:

The same view today (although by mistake I took the photo in landscape rather than portrait to mirror my 1980 photo).

Originally, in 1980, there was a set of steps leading up from Queen Victoria Street, then a reasonably flat stretch of pathway up to St. Paul’s Churchyard. The height different between St. Paul’s and Queen Victoria Street has now been smoothed with a gradual slope and smaller steps.

To prove that the photos were taken from roughly the same position, the building on the left is the College of Arms. Although in my 2019 photo this is mainly covered in sheeting, the single storey bay extension can be seen in both photos (although somewhat in the shade in my 2019 photos).

The buildings on the right have all changed since 1980, and unlike 1980, the walk heads onward across Queen Victoria Street to the Millennium Bridge and is a very busy tourist route. The main attraction seems to be the bridge’s appearance in one of the Harry Potter films judging by the couple of guided groups I walked past.

I also covered this area in my post on The Horn Tavern, Sermon Lane And Knightrider Court.

The City of London is ever changing, and it is almost to the point where you need to walk every few weeks to capture every change.

One change that has been underway for a while and has revealed, if only for a short time, a church that was once boxed in on all sides, is at the construction site for the Bank Underground Station improvements. The church is St. Mary Abchurch, enjoying its time in the sunlight, before disappearing again in a few years when construction on the station has completed and new buildings occupy the site.

The City always looks fantastic in the sunshine. Deep contrasts of bright light and the dark shadows of the buildings often make photography difficult, however where it works, many buildings look stunning.

This is the wonderful 30 Cannon Street, a brilliant example of 1970s architecture.

The building was constructed between 1974 and 1977 and designed by the architectural practice of Whinney, Son & Austen Hall. Originally built for the French bank Crédit Lyonnais, and was the first building of this type to be clad in double-skinned panels of glass-fibre reinforced cement which helped with the unique exterior design.

30 Cannon Street is Grade II listed, so hopefully is unlikely to be replaced by one of the glass and steel towers that are coming to dominate the City.

As with my South Bank walk, a series of random photos of London, but that is what I enjoy, walking the city and taking photos to tell the story of the city’s evolution.