I have always been interested in what can be found beneath the city streets since finding a copy of Under London by F.L Stevens, published in 1939, probably one of the earliest books dedicated to the subject.

In the late 1970’s, straight out of school as a British Telecom apprentice and working in one of the hidden regional seats of government during the Cold War only furthered this interest. This site in Essex was entered via an ordinary bungalow built on a hillside, inside which a long tunnel led deep into the hillside to the centre of the complex. The site is now open as a tourist attraction !

Therefore I will always take any opportunity for an underground visit and recently the London Transport Museum have been arranging open days at a number of facilities associated with the transport system.

A couple of weeks ago, as part of the London Transport Museum open days I visited the Clapham South Deep-Level Shelter, built during the 2nd World War.

The book Under London, being published in 1939, did not cover the structures built during the war, however it does show the rapid change in the types of defences needed to protect Londoners. The book concludes with a final chapter “London Takes Cover” which documents some of the preparations in London for the expected bombing of the city. Part of the chapter reads:

“A model system of trenches has been built in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, under the seven acres of which is an underground network, one thousand four hundred and twenty-nine feet long, seven feet deep, and covered with concrete and two feet of earth. Seating accommodation is provided for one thousand three hundred people. When the work is finished, turf will be replanted, tennis courts re-laid and, in addition, a new putting green is to be constructed.

Trench systems nearing completion are, at the time I write this, at Clapham Common; Kennington Park; Victoria Park….”

There follows a list of the locations in London where trench systems were being built. The inadequate protection provided by shallow trench systems for the bombing that was to come was soon very apparent. I doubt the author of Under London could have imagined the shelters that would be built in the next few years, one of which was the Clapham South Deep-Level Shelter.

One of the entrances to the shelter close to Clapham South Underground Station on the edge of the Common:

At the start of the war, air raid shelters consisted of trench systems, the basements of buildings, along with the opening of underground stations, although the adequacy of these proved ineffective to direct bombing, including parts of the underground system which were just below the surface. Deep level shelters were needed and in October 1940, with no end in sight of the heavy bombing on London, the Government planned the construction of a number of deep level shelters across London capable of taking up to 10,000 people in each shelter.

Construction started in 1941 with completion in 1942.

To enter the tunnel system on the tour, a second entrance was used, not the obvious entrance on the edge of the Common. At first glance it could be part of the architectural features of the new building above the entrance, however a side door provides access to a very different world:

The shelters are approximately 30 meters deep and the vertical shaft providing access has a double spiral of stairs to speed entry and descent. Whilst the shelters had the facilities to house 10,000 people, getting this many in and out needed the double spiral to try and speed this up, although how long it may have taken for many thousands of people of all ages to climb 30 meters of stairs after a long night below ground can only be imagined.

At the base of the stairs, part of one of the cross passages:

The cross passages provide access to the main shelters. These consist of two tunnels, each about 400 meters long. The tunnels are divided into upper and lower levels thereby doubling the number of people each tunnel can accommodate.

A glimpse of one of the shelter tunnels curving into the distance:

Looking down one of the shelter tunnels. This is the lower half of the tunnel with an identical arrangement in the half of the tunnel above. On the left are the original frames of the bunks provided for those seeking shelter. On the right is shelving for when the shelter was later used to provide secure archive storage.

One of the sections has been fitted out to show how they would have been used:

Looking along the top bunk level, the length of the shelter. Imagine looking along this level when the top bunks were all occupied.

One of the junctions on the cross passages. On the left is one of the places on the tour where a photo background has been put in place to show what the shelter looked like at the time of use, very effective.

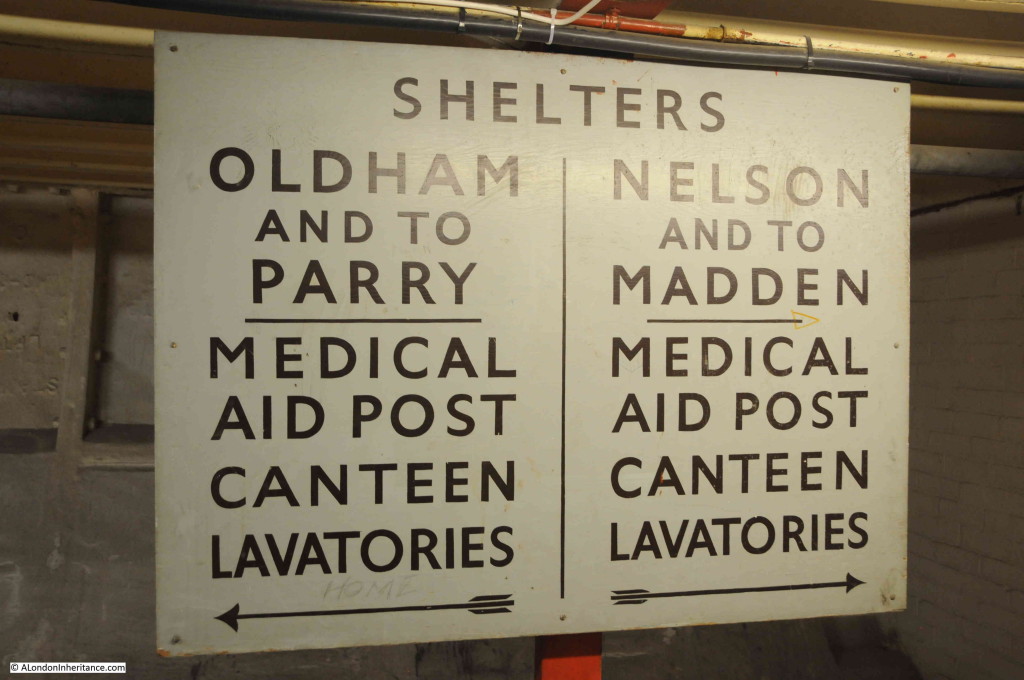

With two long, identical tunnels, each divided into two, it would have been rather difficult to find the specific place where you had your bunk or to meet other family members or friends. To help with location finding, the tunnels were divided into shelter areas, each named after a senior officer in the navy.

The tunnels are very well signposted so even with many thousands of people, whilst it would have been crowded, it would have been difficult to get lost.

Each of the shelters had a canteen. To keep up morale and provide an incentive for being in the shelters, as well as hot drinks, the canteens provided sausage rolls, meat pies etc. food that was not easily available due to the strict rationing restrictions in place at the time.

Original fuse box at one of the canteen locations:

As well as the fuse box, other reminders of the original use of sections of the shelters remain. Original location for a sink in one of the medical facilities:

Examples of wartime posters highlighting the problems with food supplies at the time and the importance of home grown, basic food products such as potatoes and carrots:

As well as the two surface entrances, the tunnels also has an access to the Clapham South Underground Station. This entrance is now bricked up, however during the war it was used to provide direct access to the station platforms for those travelling to work by underground train.

Throughout the tour, the sound of trains highlighted how close the shelters were to the tunnels of the Northern Line.

Steps leading up to the bricked up entrance to Clapham South station:

Brown staining on some of the tunnel walls provide an indication of the materials used in construction. Apparently the brown stains are from the creosote used to soak the hemp that provides waterproofing between joints in the structure.

By the time the shelters were completed, the intense bombing from the blitz period had ceased and bombing of London was much more sporadic. The shelters remained available, but were not opened. This changed during the later period of the war when the V1 and V2 weapons were targeting London.

After the war the Clapham South shelters were called on to provide accommodation to meet a number of specific needs.

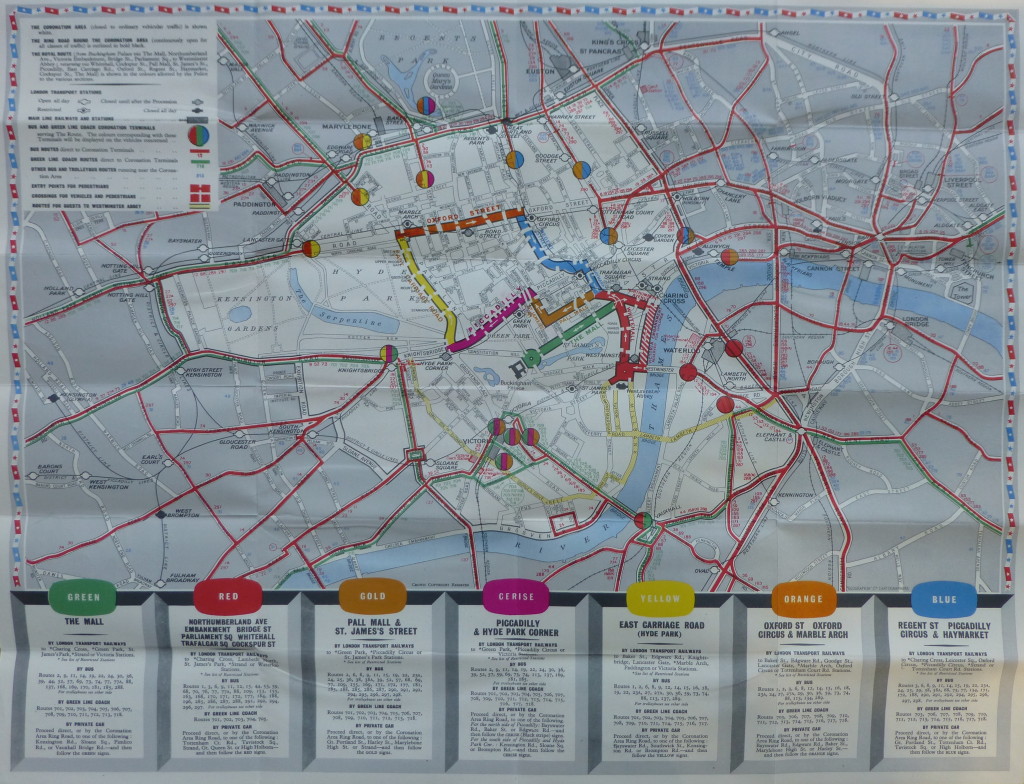

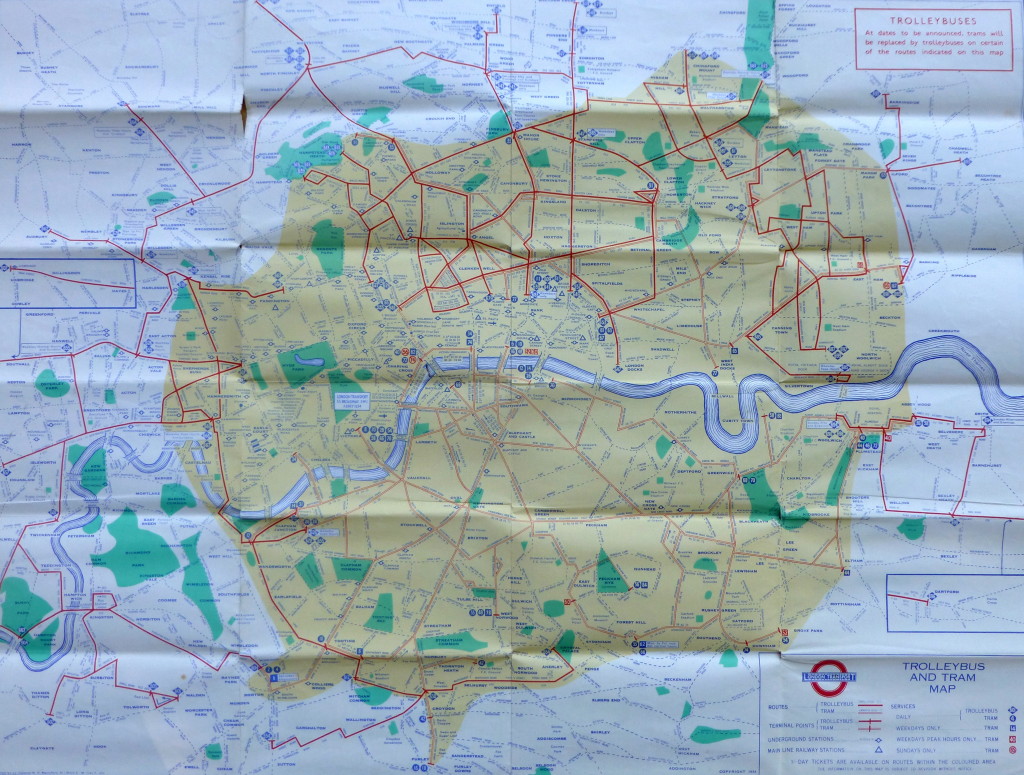

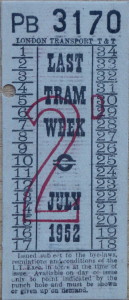

Military personnel were accommodated in the shelters for large events in London, such as the 1953 coronation. Migrant workers who arrived in 1948 on the Empire Windrush, and who did not have any other accommodation, were provided with space in the shelters.

During the 1951 Festival of Britain, the shelters became the Festival Hotel and provided cheap accommodation for overseas visitors to the festival.

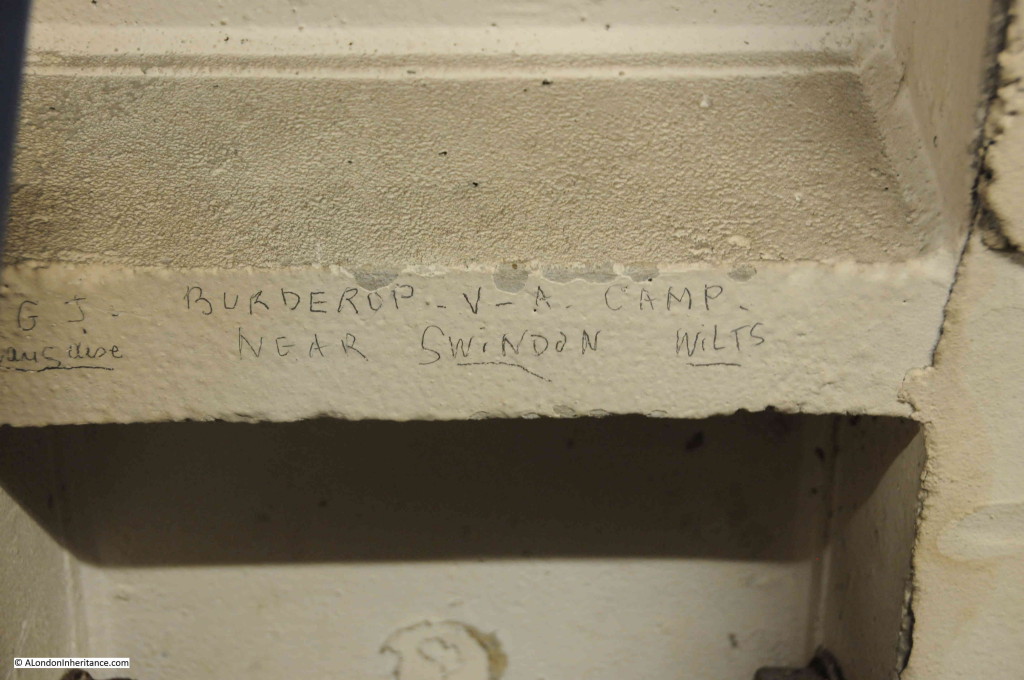

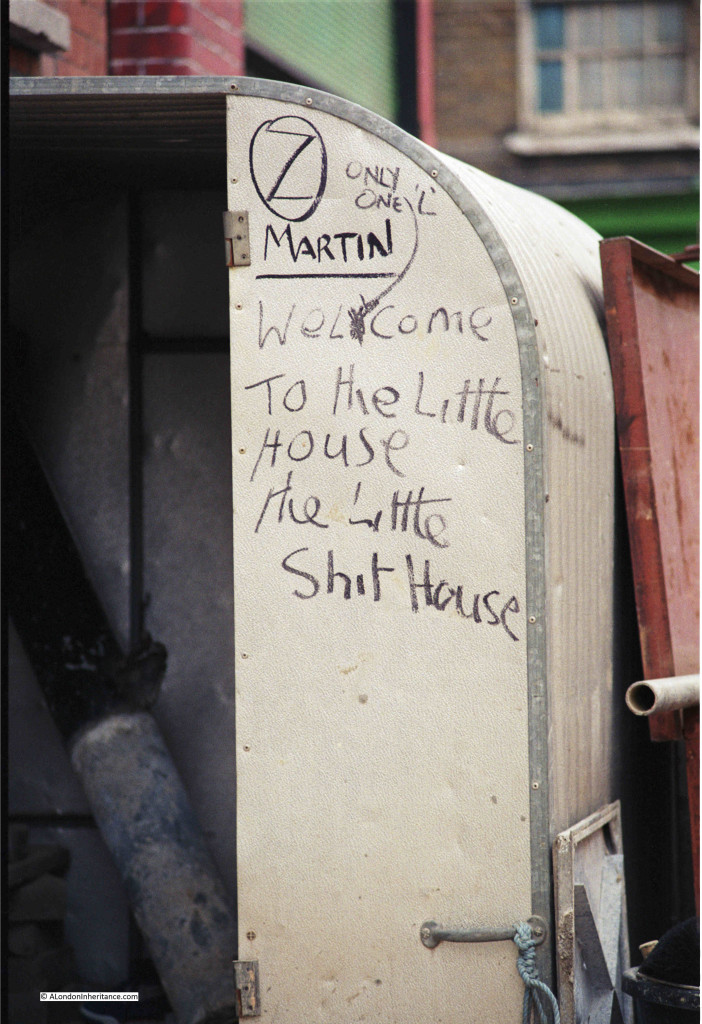

Some of these occupants left their mark in the shelters. Above the bunks, names can be found written on the shelter walls. Due to the dry conditions and stable temperatures of the shelters these look as if they could have been written yesterday rather than over 60 years ago:

Some are written upside down. Here, Marcel de Wael from Brussels was obviously lying on his bunk, writing his name on the shelter wall above his head:

As well as reminders of the occupants, other original signage can be found throughout the shelters:

And inside the control room, one of the boards and the outlines of alarms and indicators that would have notified the staff of any problems within the shelters:

The end of the tour and time to climb the 30 meters back to the surface:

The shelters are impressive to visit and the London Transport Museum tours are really well run and highly informative.

The shelters are impressive to visit and the London Transport Museum tours are really well run and highly informative.

These tunnels were built at the height of the war and the blitz on London, mainly dug by hand and without the complex shields and tunnel boring machines that would be used today.

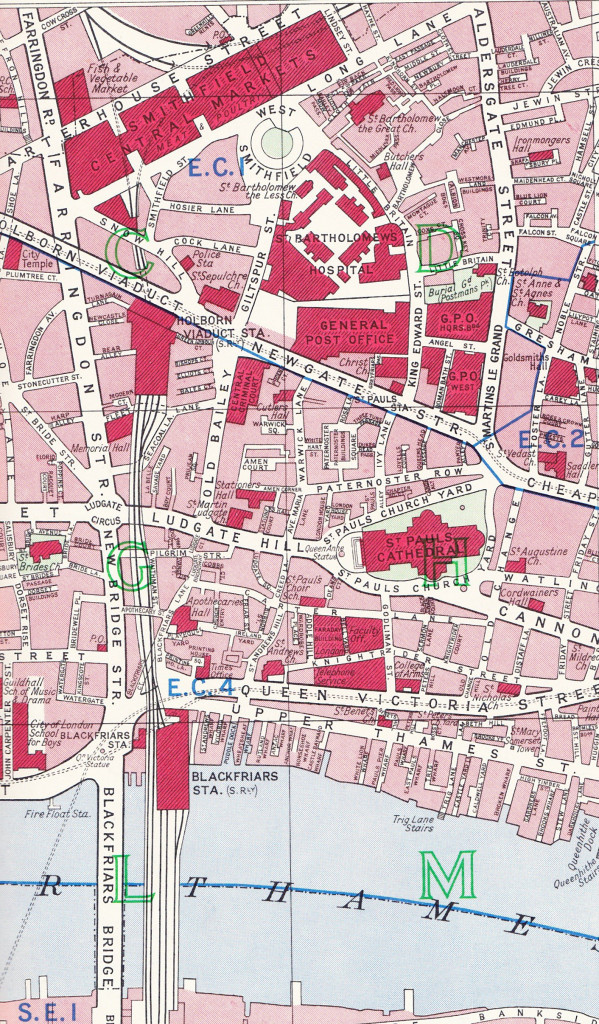

It was not just the shelters at Clapham South, but the other eight shelters completed around London at the same time. In addition to Clapham South, shelters were completed at Clapham Common, Clapham North, Stockwell, Goodge Street, Chancery Lane, Camden Town and Belsize Park. Tunnels were started at the Oval and St. Pauls but were abandoned at the Oval due to poor ground conditions and at St. Paul’s due to restrictions with tunnelling close to the cathedral.

A truly impressive undertaking.

The excellent Subterranea Britannica site has a wealth of detail and photos on the Clapham South Deep-Level Shelter which can be found here.