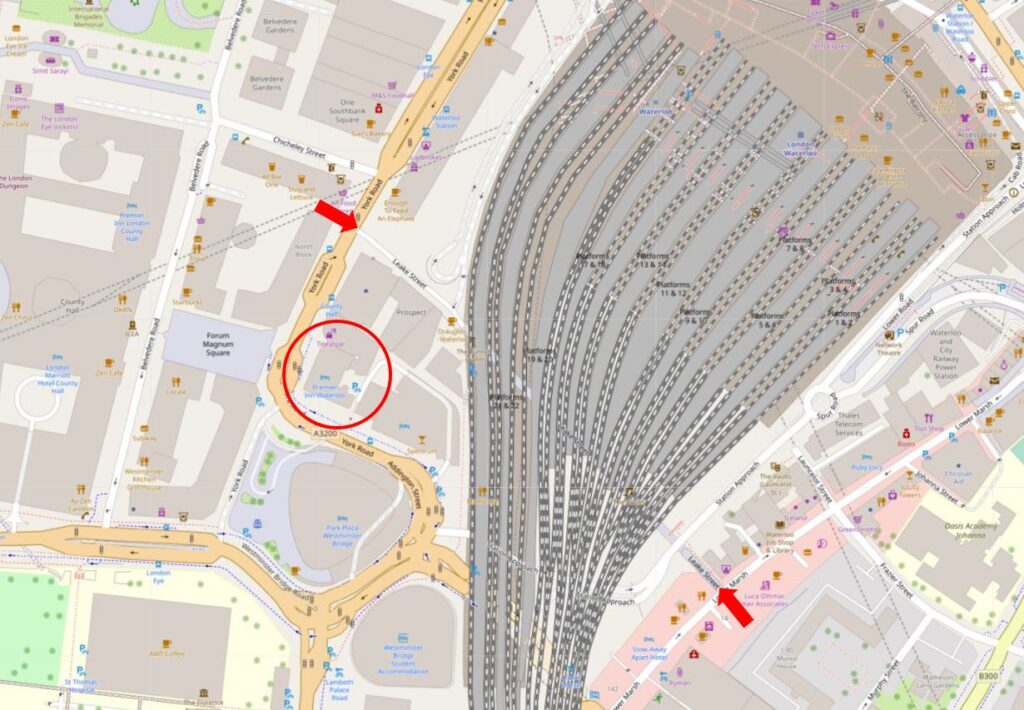

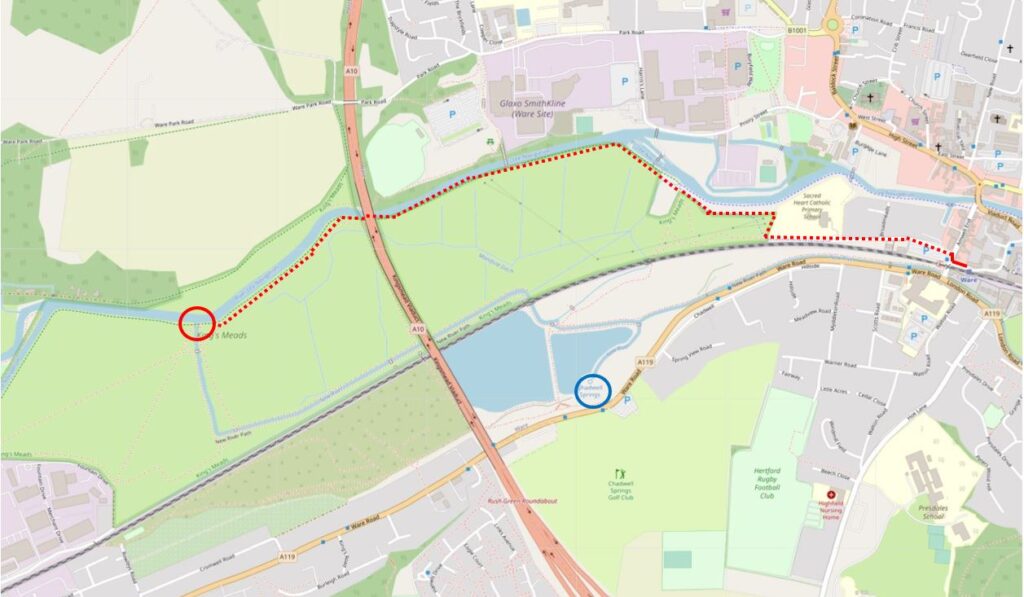

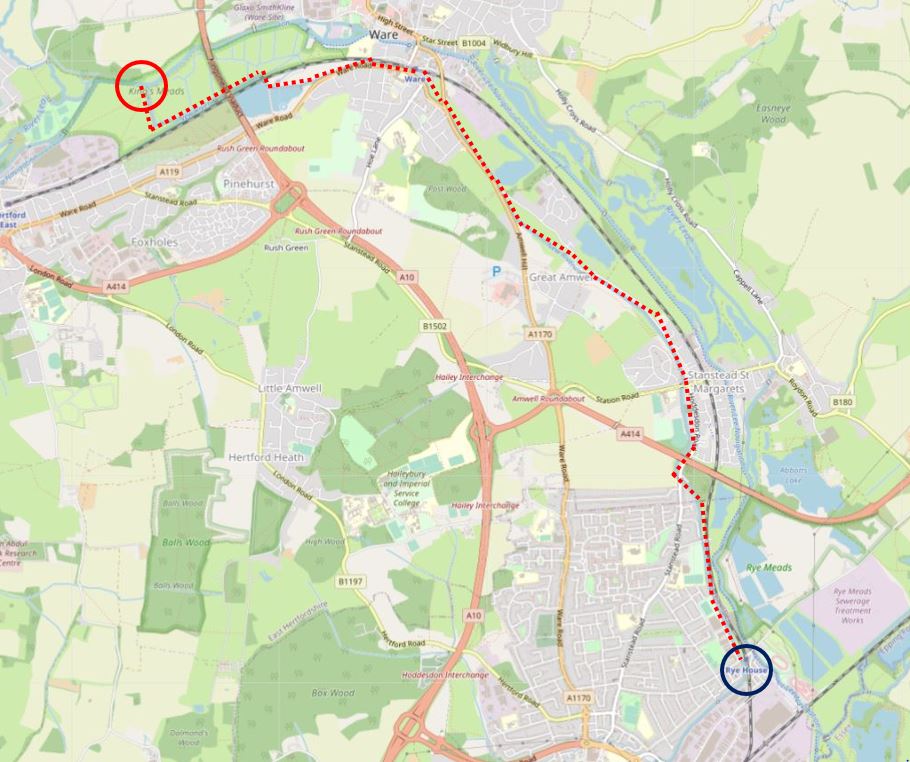

In October of last year, I started the first part of the New River Walk, a walk alongside the 17th century artificial river that was built to bring in supplies of clean water from springs near Ware in Hertfordshire to New River Head in north Clerkenwell.

Some years ago Thames Water signposted a New River Walk that follows the course of the New River as far as is possible, and where it is not possible to walk alongside, the route guides the walker to the next point to access the river.

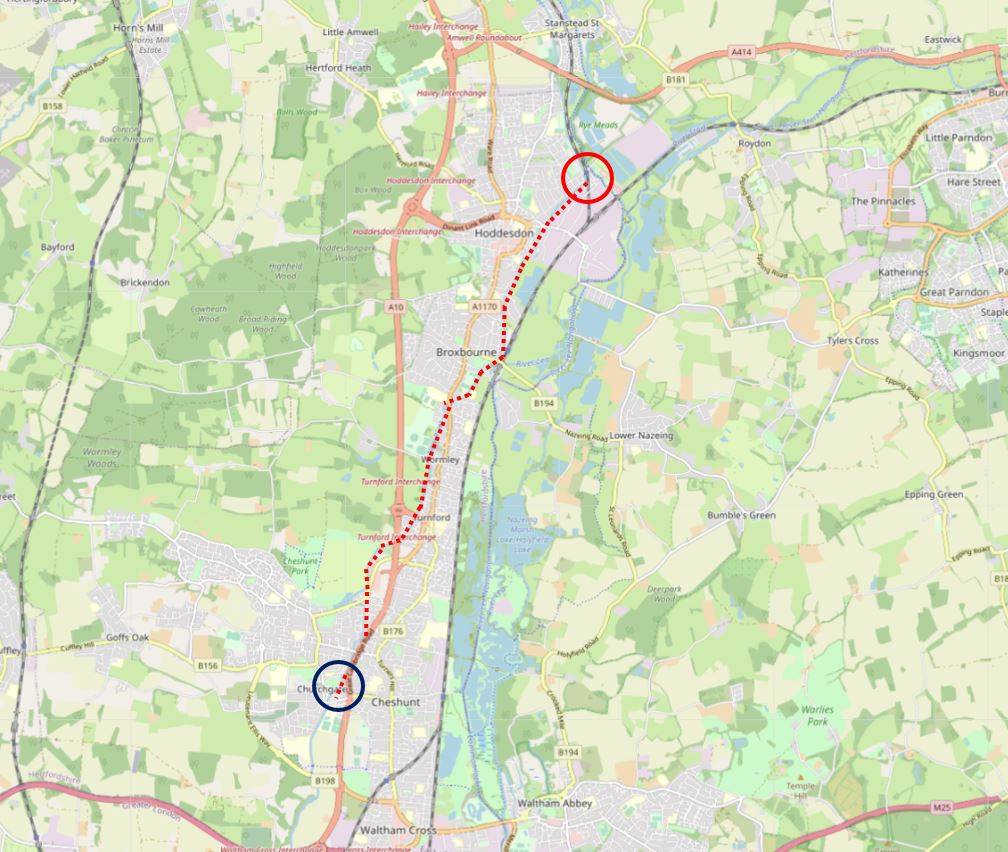

A couple of weekends ago, on a grey and damp Saturday, we started a second weekend to complete the walk. Starting at October’s finishing point in Cheshunt, and ending at New River Head.

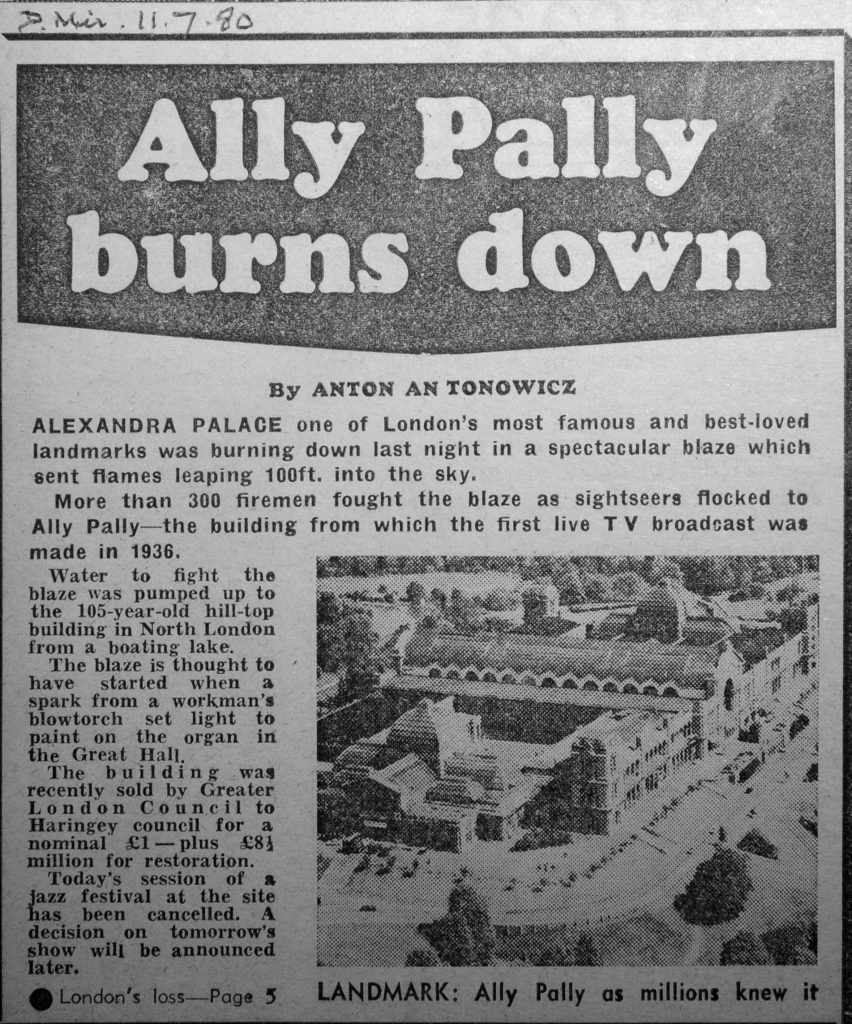

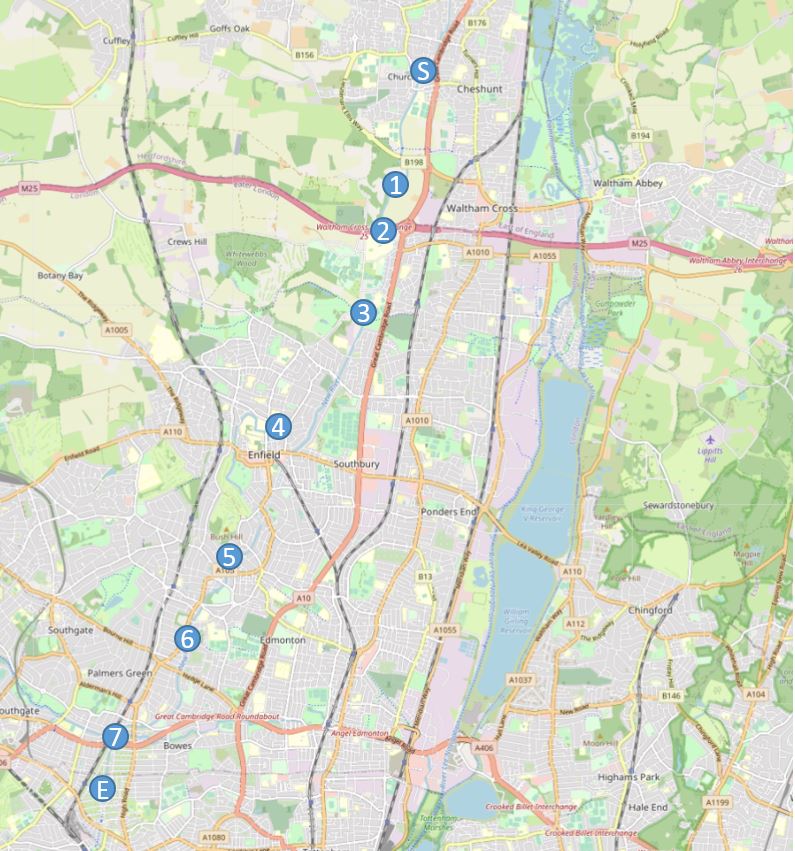

This post covers the New River Walk from Cheshunt to near Bowes Park station, where the river flows into a tunnel heading to Alexandra Palace. A mid-week post will cover the stage of the walk from Alexandra Palace to New River Head.

The route of today’s post can be seen in the following map. Starting at “S”, and with some of the key points covered in the post numbered.

The problem with arranging a weekend in advance is that the weather cannot be guaranteed, and after some sunny weekends, the weekend of the walk turned out grey and damp, with plenty of mud on the path.

The was the scene starting off at Cheshunt:

In the following photo, the large building on the right is the 40 acre site of Newsprinters. As the majority of newspapers no longer run their own print presses, companies such as Newsprinters provide this service to multiple newspapers, so if you read one, it may well have been printed at this site, which is alongside the A10.

A short distance onward, and the results of Storm Eunice were still visible, and would continue to be at a number of points along the New River:

Point 1 on the map: In the following photo the New River opens out into a small lake. The Cheshunt Country Club is behind the trees on the right, and behind the trees directly in front is Theobalds Park:

Theobalds Park is the site of a 16th century palace that was destroyed during the Civil War, and a later stately home which is now a hotel and club.

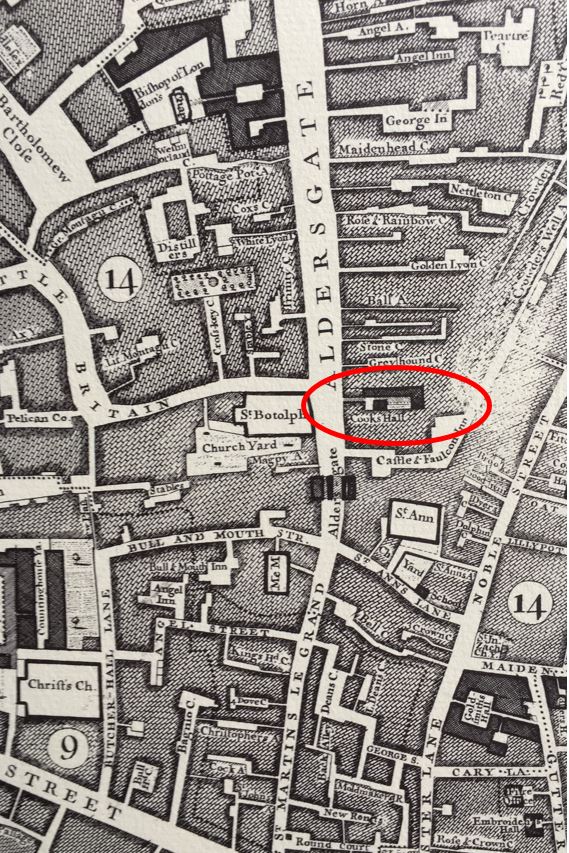

A London connection with Theobalds Park is that Temple Bar Gate was rebuilt here in 1888 after being demolished from its original location at the point where Fleet Street meets the Strand. The stones of the old gate were purchased by Lady Meux, wife of Sir Henry Bruce Meux (of the Meux’s Brewery Company), who owned the house in Theobalds Park.

The gate was rebuilt in the park, and used as an entertainment venue by Lady Meux.

The gate was relocated to London, with reconstruction and restoration completed in 2004, and the gate can now be seen at the entrance to Paternoster Square, just north of St Paul’s Cathedral.

The gate in Theobalds Park, five years before moving back to London:

(Image credit: Temple Bar, Theobalds Park cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Christine Matthews – geograph.org.uk/p/185643)

Point 2 on the map: Continuing past Theobalds Park, and it was time to cross a major landmark on the route, a landmark that confirmed we were heading towards outer London. This was the crossing of the M25.

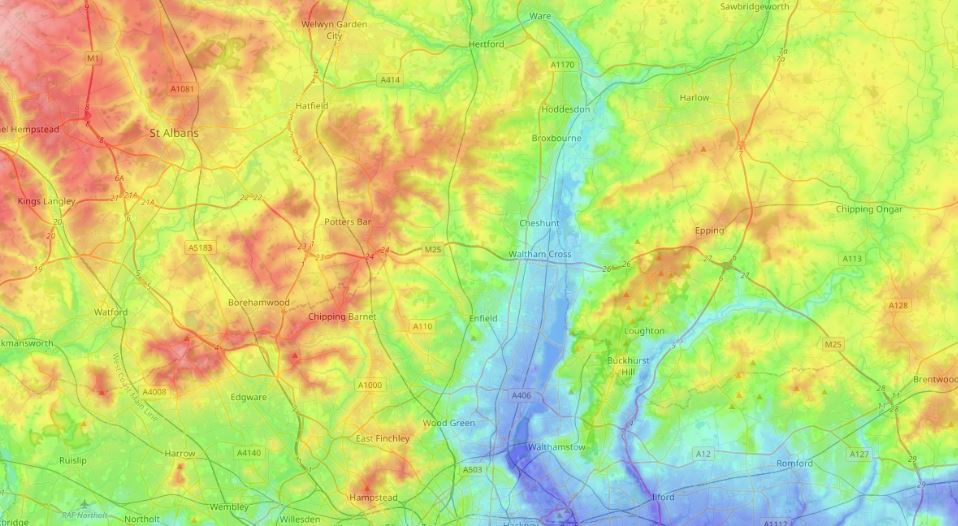

The New River flows from source in Ware to the current termination point at the west and east reservoirs by Seven Sisters Road, without any form of pumping. The incredibly slight gradient along the route is just sufficient to ensure a continuous flow of water.

Despite being built in the early 17th century, the New River continues to be a source of water for London, so when the New River meets the M25, the M25 has to give way.

The M25 has to go under the New River, and the river is carried over the motorway within its own dedicated bridge.

This is the point where the river is split into two channels, ready to enter the bridge:

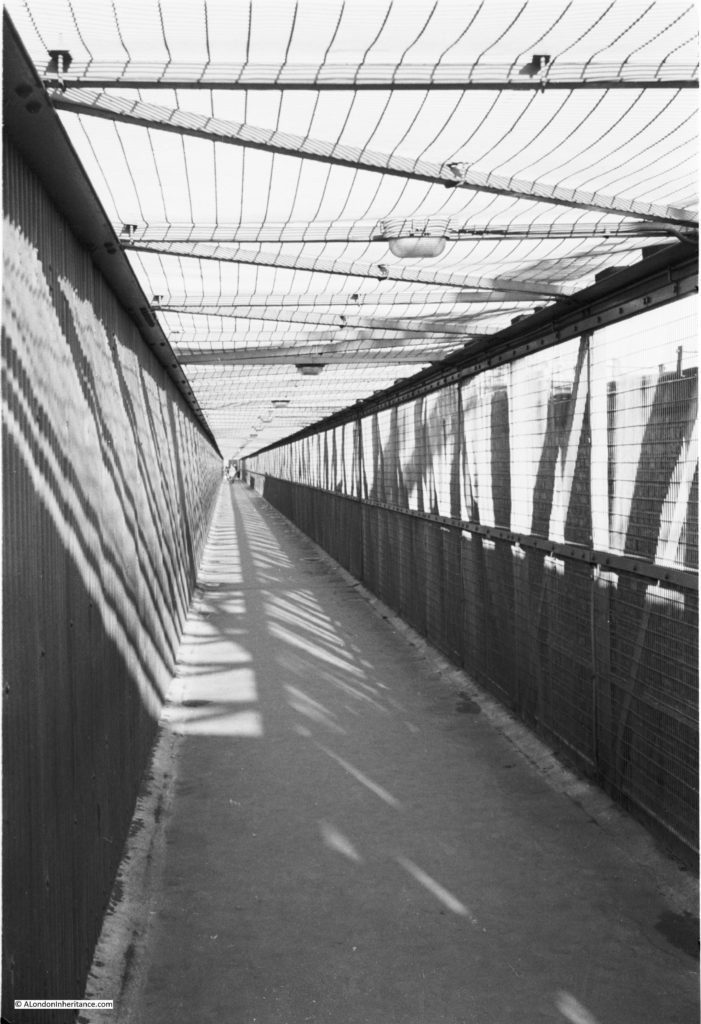

The two channels flow along the bridge, which has a thick concrete slab covering the top:

Looking along the bridge dedicated to carrying the New River over the M25:

Although the bridge carrying the New River over the M25 has a solid concrete surface, this is not a traffic route. There is a track to the Thames Water equipment on either side of the bridge, so the use of a hard surface over the bridge could be to allow Thames Water equipment to move between the two sides of the motorway.

It could also be used to prevent any accidental spillover from the river to the motorway below.

The view looking west from the centre of the bridge:

And the view looking east, at Junction 25 on the M25:

A relatively rural scene at the southern end of the bridge, with a green New River Path signpost showing the way:

The two channels of the New River exit on the south side of the M25:

Colourful graffiti on a rather grey day:

Point 3 on the map: The New River has to cross a number of natural rivers in its route from Ware to New River Head. One of these rivers is the Turkey Brook, which rises just to the east of Potters Bar and heads to join the River Lee Navigation not far from Enfield Lock station.

The Turkey Brook is shown in the following photo, with, in the background the Docwra Viaduct, originally built in 1859, which carries the New River over the Turkey Brook:

Construction of the aqueduct enabled one of the long meanders of the New River to be replaced by a straightened route. The aqueduct was built by Thomas Docwra of Cheshunt, who is presumably the source of the name.

Docwra is an unusual surname, and Thomas Docwra could well be a descendent of another Thomas Docwra who was the Grand Prior of the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem in England in the early 16th century, and who had their headquarters at Clerkenwell, of which St John’s Gate is a reminder.

According to the Thames Water guide to the walk, somewhere around the Docwra Aqueduct are a number of boreholes which enable the New River to be part of an “Artificial Recharge Scheme”. This is where water is extracted from the New River and pumped into the chalk below ground. When extra water is needed to supply London, it is then pumped back out of this aquifer.

I did not see any evidence of this, but the path diverts slightly around the Docwra Aqueduct, and along the path there were also a number of bland brick buildings with nothing to provide a clue as to their function.

Soon after the Docwra Aqueduct, the evidence of the long straight route of the river enabled by the aqueduct can be seen, along with a number of places where what looked like over sized sandbags lining one side of the river:

Not sure why there would be sandbags, as the New River is not a natural river liable to flood, with water levels in the New River being controlled.

Another casualty from Storm Eunice:

And more evidence of the storm:

Point 4 on the map: The walk has now reached Enfield, and there is very little of the river to see. Originally, there was a loop of the river around Enfield, however in 1900, this loop was bypassed by the construction of three cast iron pipes under the town which carried the river on a more direct route.

This means that the New River Walk now runs through the streets of Enfield, with the green signposts directing the way:

Parts of the original route of the New River around Enfield have been preserved as an ornamental watercourse, and the most attractive part is along the aptly named River View, which starts with the Crown and Horseshoes pub overlooking the old river:

Looking along River View, with terrace houses lining one side of the footpath, the ornamental remains of the New River on the other side:

The houses on the right in the above photo appear to have their own private bridge over the river to their gardens.

Small park at the end of River View – one of the small bridges over the ornamental New River can be seen on the right:

South of Enfield we pick up the New River again, however it does a number of disappearing acts as it flows through housing estates and other areas where there is no accessible path alongside the river.

Point 5 on the map: This is another point where the New River has to cross a natural stream. It also shows the age of the New River Walk, and that there appears to have been little major maintenance of the walk over the last few years.

Another of the natural streams that the New River had to cross was Salmon’s Brook. This stream has its source in fields north of Hadley Wood station, and eventually flows into the River Lee.

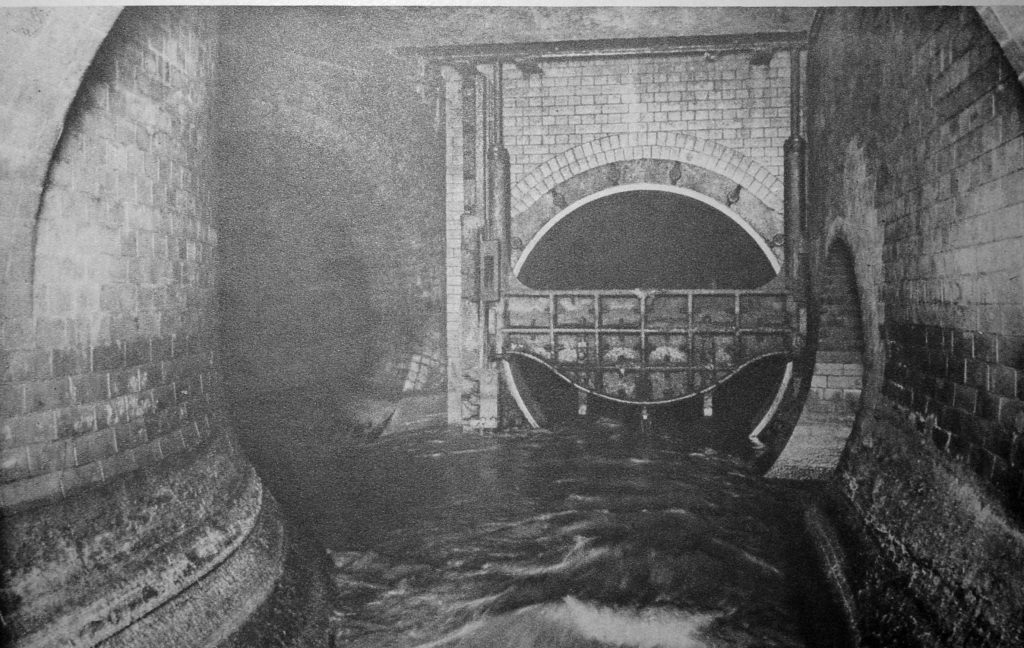

To carry the stream under the New River, a lead lined wooden aqueduct was originally constructed, which was replaced by a brick aqueduct in 1682, which was later largely replaced by a clay embankment and tunnel.

The 1682 arch (known as the Clarendon Arch after the Earl of Clarendon who was the Governor of the New River Company at the time that the arch was constructed) through which the Salmon’s Brook enters the tunnel under the New River was a viewing point when Thames Water originally laid out the New River path, however access to the viewing point has become overgrown and in a bad state of repair and is now closed and fenced off, so it was impossible to get down to the stream and see the arch.

At the top of the viewing point, there is a stone plaque. Very hard to read due to weathering and lack of maintenance, however it dates from 1786 when the New River was raised on a bank of earth over the stream.

The following photo shows the stone plaque and Salmon’s Brook. Originally there was access via steps to the right to see the 1682 arch, which is now a Grade II listed structure.

The arch is the oldest part of the New River to remain, and has an inscription and crest around the entrance to the tunnel:

(Image credit: Clarendon Arch, Bush Hill, London N21 cc-by-sa/2.0 – © John Salmon – geograph.org.uk/p/302364)

Around Winchmore Hill, the New River meanders past larger houses, with gardens backing onto the river:

With New River green signs directing the path along some small diversions:

There are a number of buildings along this stretch of the New River that appear to be pumping stations, however unlike the buildings in the stretch from Ware to Cheshunt, these buildings do not appear to be extracting ground water and pumping into the river.

In the following photo, the building does have what appears to be a concrete channel running to the river, so it may have the capability to pump water from the chalk below, into the river.

Point 6 on the map: At this point, the New River comes up to Green Lanes by the junction with Carpenter Gardens before turning away to head into a housing estate. A couple of stones mark the New River along with a small green space, with the reminder that the New River is “Neither New, Nor a River”:

We can follow the New River for a short distance from the above photo, but it then heads between rows of houses on either side, with the gardens of the houses reaching straight down to the river – so no walking route.

Instead, we walk along the adjacent streets. Here is the aptly named River Avenue, with the New River behind the houses on the left:

I have no idea whether having the New River running at the end of your garden adds to the property price, but it does feature in estate agents descriptions, as there is currently one house for sale in the street that has “fantastic views over the New River and the London skyline • 40ft x 20ft rear garden backing onto the New River”.

Rejoining the New River and more dramatic evidence of Storm Eunice:

The stretch with the marque is along a section of the New River where there is an earth embankment along one side where the river was built along sloping ground and the embankment was needed to ensure the level flow of the river.

At the far end of this stretch, an attempt had been made to close off the access point, presumably due to the marque:

Point 7 on the map: There are two landmarks at point 7. The first is where the New River crosses yet another natural river, this is Pymmes Brook emerging from a tunnel under the adjacent railway line, before it enters another tunnel under the New River:

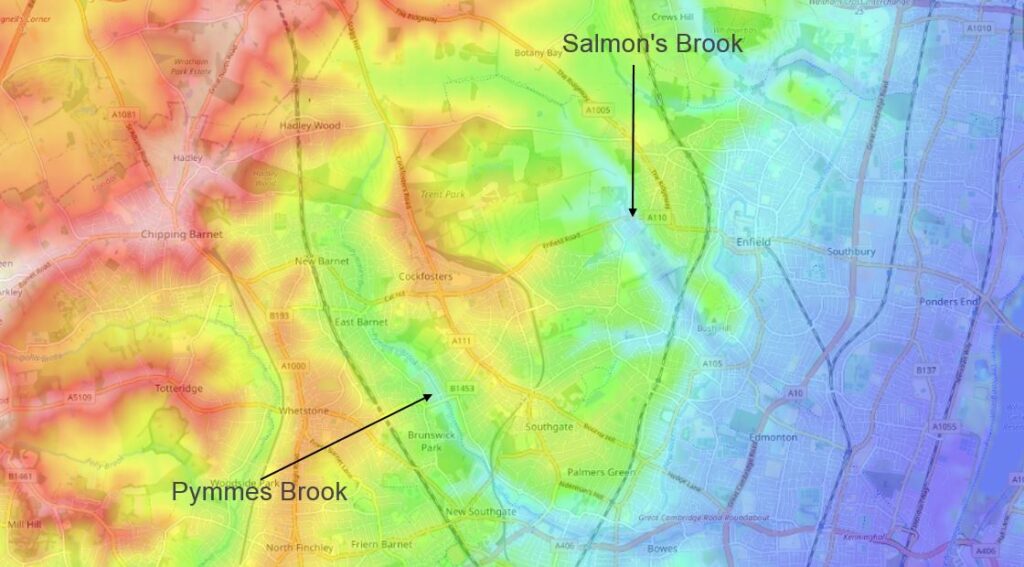

Pymmes Brook appears to emerge in the golf course, just to the north west of Cockfosters station. As with the other rivers and streams that the New River crosses, Pymmes Brook flows east to where it joins the River Lee.

These streams seem relatively insignificant, however taking a wider view and looking at a topographic map, we can see how they have formed in low ground either side of the higher ground of Cockfosters, and over centuries have probably been responsible for some of the erosion of the lower ground as they drained the area around Hadley Wood.

The second landmark at point 7 is where the New River crosses the A406 – the north circular road seen in the photo below. The bridge carries a railway across the road, the New River is flowing under the road directly in front of where I am standing:

The following photo shows the New River emerging from the tunnel that carries it under the North Circular:

After crossing the North Circular, the New River continues alongside terrace streets. One of the houses backing on to the New River has a faded ghost sign for a Builder and Decorator. An unusual position as the sign was not facing onto any road:

I am approaching the end of the first day of the weekend’s walk, and the New River helpfully provides a natural stopping point.

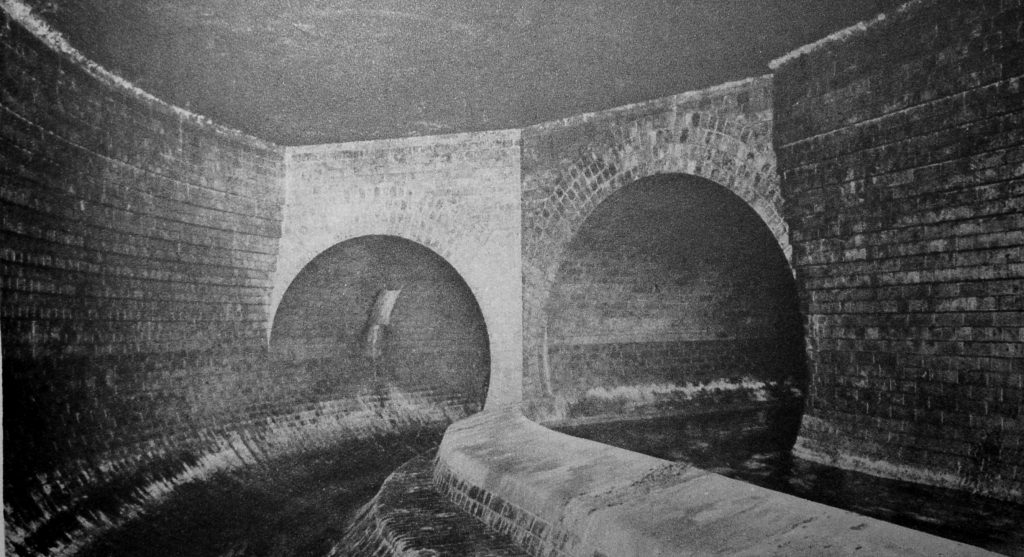

I have reached Bowes Park (Point E on the map), and here the New River enters a tunnel:

The tunnel was built as one of the 19th century initiatives to straighten out the New River and the tunnel runs from Bowes Park to near Alexandra Palace station, and this straight length of tunnel (built in 1859) reduced the original overall length of the New River by 1.5km.

That was the end of Saturday’s walk. Luckily, public transport serves the New River walk really well. In the upper stretches of the walk, it is close to the line from Liverpool Street up to Ware, and for the walk covered in today’s post, it is close to the line to Moorgate, so from the entrance to the tunnel, it was a short walk up to Bowes Park station.

There are numerous places along the route of the New River which take a name from some aspect of the river. Whether a simple name like River Avenue, or perhaps named after someone associated with the river, and the road that leads from the New River up to Bowes Park station is called Myddleton Road after Sir Hugh Myddleton who was the driving force behind the financing and construction of the New River in the early years of the 17th century.

The name is also displayed on the top of this house in Myddleton Road, that was once the home of Lazaris Family Butchers:

We arrived at Bowes Park station, just as a train was leaving. The next one was cancelled, so the day ended with an hours wait on a windswept platform for a train:

Before I end the post, you may be wondering (or almost certainly not), how the New River is kept relatively clean of floating debris, given the amount of trees that line the side, number of housing estates the river flows through etc.

We did notice that there was more rubbish in the river, the further we headed into London, but we also saw a rather clever cleaning method in use at two locations.

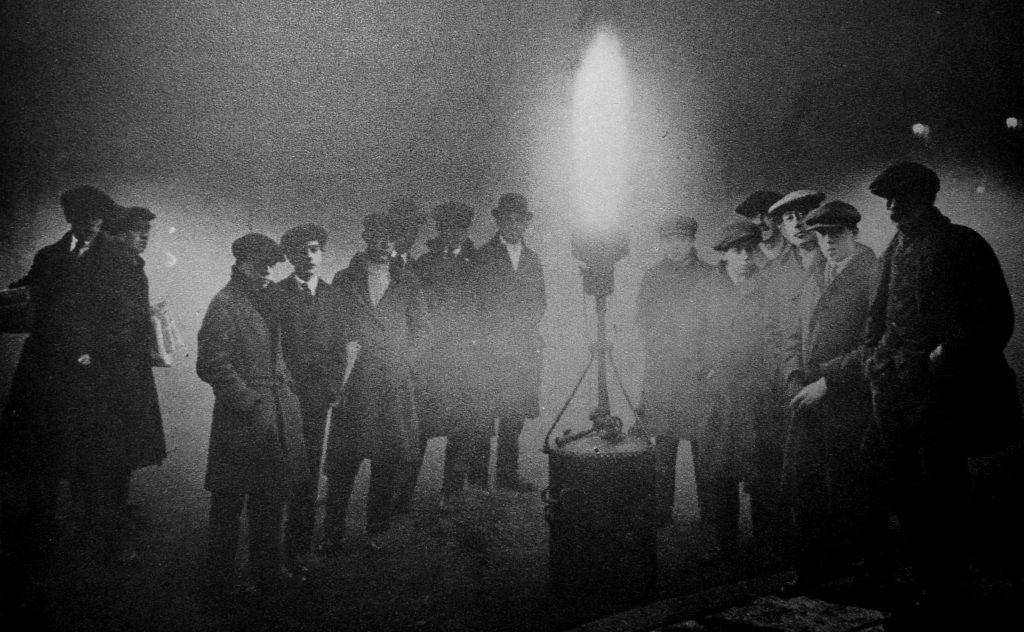

In the following photo, you can see a small cage suspended over the river.

This cage moves along the gantry across the river and is lowered into the river. There is a grating in the river that allows rubbish to collect rather than continue flowing. As the cage is dropped into the river, the lower section opens up as it falls below the surface of the water.

The cage then collects any rubbish collected against the grating, the cage closes, and is raised. It then moves to the right where once over the ground, the cage opens, depositing any collected rubbish on the ground.

The cage is lowered progressively across the river so the whole width is covered.

The whole process appears to be automatic as there was no one visible on the river bank, or building from which to operate the system.

And that is how the New River is automatically cleaned.

Time permitting, the final stage, from Bowes Park to New River Head in north Clerkenwell will be the subject of a mid-week post in the next couple of weeks.