Epidemiology has come to public attention as one of the key areas of expertise needed to reduce the spread of Covid-19. The pandemic has come as something of a shock given the significant reductions in disease over the last 100 plus years, although in reality, such a global event was probably only a matter of time given the background transmission of new diseases, and the interconnectedness of the world in the 21st century.

Contagious disease has long been a very significant problem. Outbreaks would rise and fall, killing many thousands of people, often in limited areas. Prior to the mid 19th century, thinking was often that disease was caused and transmitted by a miasma – a form of “bad air”.

It took the work of a number of Doctors and Scientists to prove this was not correct, and to trace the real cause of disease transmission, and one of these was Dr. John Snow, often called the founding father of Epidemiology. His work on the transmission of Cholera in London would demonstrate conclusively how this killer of large numbers of Londoners was transmitted.

The British Medical Journal describes Epidemiology as “the study of how often diseases occur in different groups of people and why. Epidemiological information is used to plan and evaluate strategies to prevent illness and as a guide to the management of patients in whom disease has already developed.”

Although John Snow’s work on Cholera covered the whole country, including outbreaks across London, he is more widely known for one outbreak in 1854 in Broad Street, Soho, and a couple of weeks ago I had a walk around the area to find the focal point of the outbreak, and the pub that bears his name:

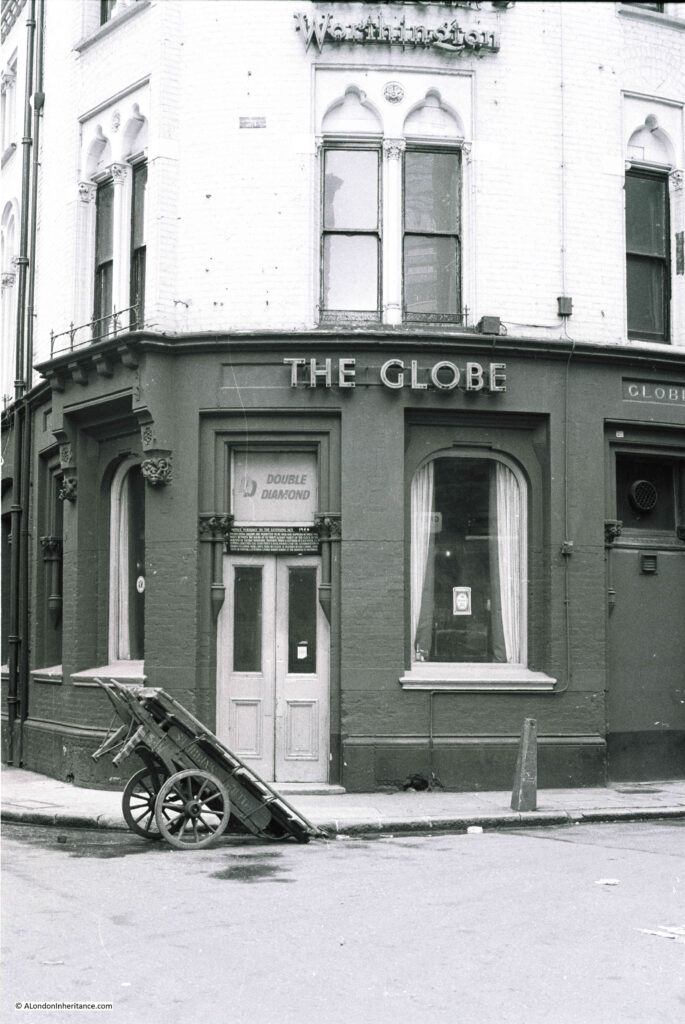

The John Snow pub stands on the corner of Broadwick Street (originally Broad Street) and Lexington Street (originally Cambridge Street). A number of streets in this area of Soho have changed their names since the mid 19th century.

The pub building dates from the 1870s, and was originally called the “Newcastle-upon-Tyne”, The name changed in 1955 to commemorate the centenary of the work in the area of John Snow.

He traced the source of the local Cholera outbreak to a water pump that stood in the street outside the current pub. I will detail how he did this later in the post. Today, there is an imitation pump in the same spot:

The pump was installed in its current position in 2018, having been removed three years earlier due to building work which included extension of the pavement. The replica pump had been installed in a slightly different position to the original, and a pink granite curb stone had marked the location of the original pump.

One of the fascinations of London is that historical reminders tend to accumulate, and the pink granite curb stone was retained, and can now be seen to the left of the plinth on which the pump is mounted, now in the correct position.

The pump is also unusual in that it does not have a handle – the reason for this will be explained later in the post.

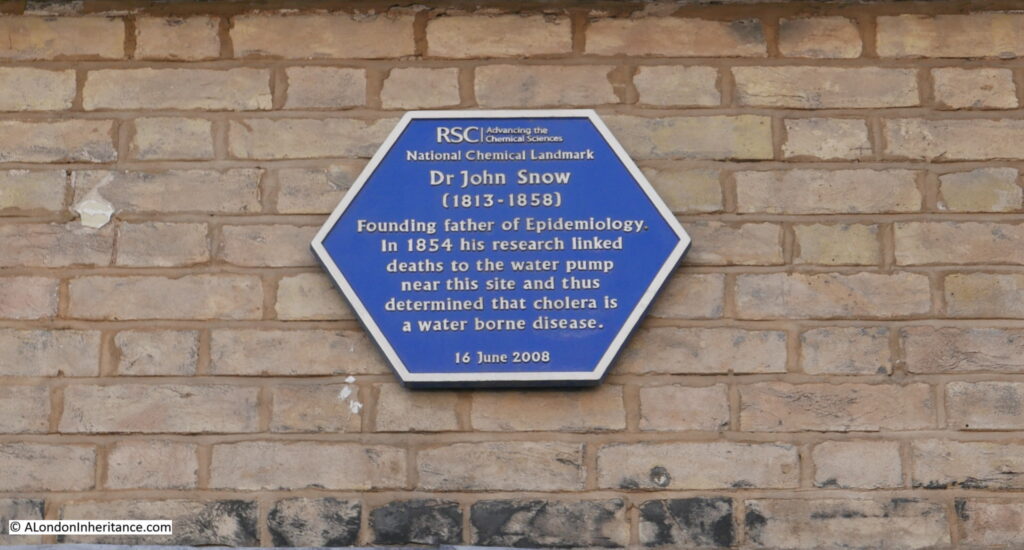

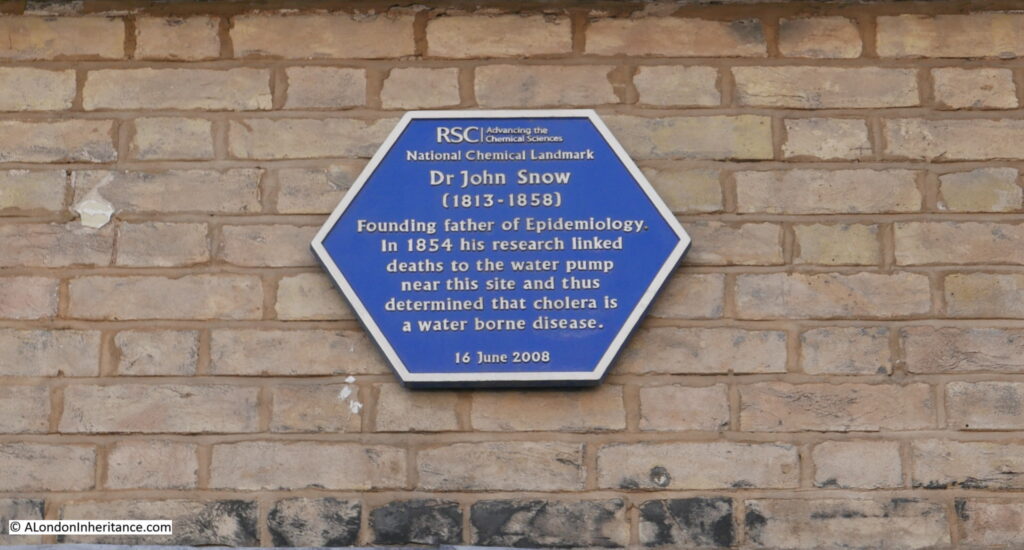

And on the pub wall is a plaque by the Royal Society of Chemistry naming John Snow as the founding father of Epidemiology for his work in the area:

The pump and pub in Broadwick Street:

John Snow was born in York on the 15th of March 1813. A career in medicine seems to have been defined at an early age,. When he was 14 he started work as an apprentice for William Hardcastle, a surgeon in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

He had early experience with cholera outbreaks, and during 1831 he worked on an outbreak at Killingworth Colliery. It was here that he appears to have started making detailed notes on the outbreak – gathering the data that would be essential in understanding the root cause.

He moved to London in 1836 to study at the Hunterian School of Medicine, and a year later started hospital practice at the Westminster Hospital. The following year, 1838, he became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, and in 1850 became a member of the Royal College of Physicians.

Doctor John Snow:

Data gathering in 19th century London was actually rather good. The Registrar General published regular returns detailing the number of deaths by date, cause and location. Where possible, information also included age, gender and profession, so a mass of data was available for evaluation, however outdated theories often prevented the use of data to find the root cause of disease outbreaks.

London could be absolutely filthy. Much of London was not yet connected to the expanding sewer network. Houses often had cesspools directly underneath, raw sewage was pumped into the Thames, contaminated water would be dumped in the streets and ditches.

The city’s cemeteries were overflowing, with bodies piled high in crypts and churchyards.

One of the main theories was that disease was carried in dirty air. Air polluted by rotting vegetables, dirty water, the waste from industry, and from the city’s cemeteries.

There was also no real separation between drinking water and contaminated water. For example, raw sewage was pumped into the Thames, a short distance from where water was taken out for distribution to houses and pumps.

There were frequent outbreaks of cholera. 1849 being the year of the most recent outbreak, however there was also a background rate of cholera deaths happening every year.

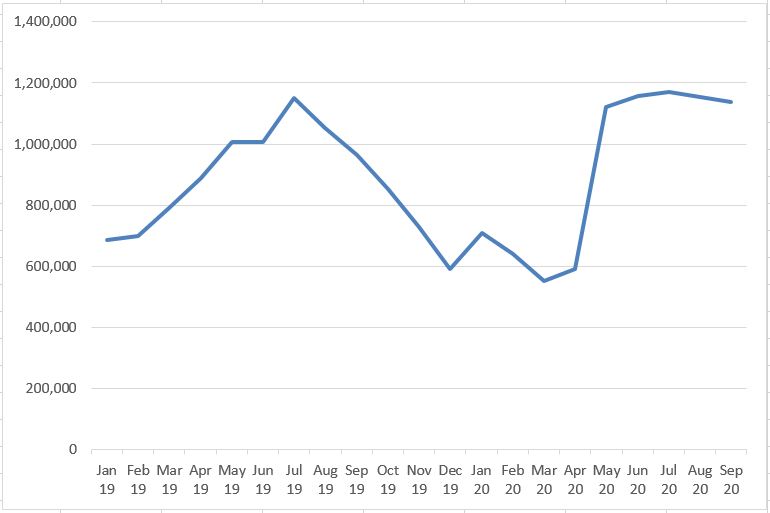

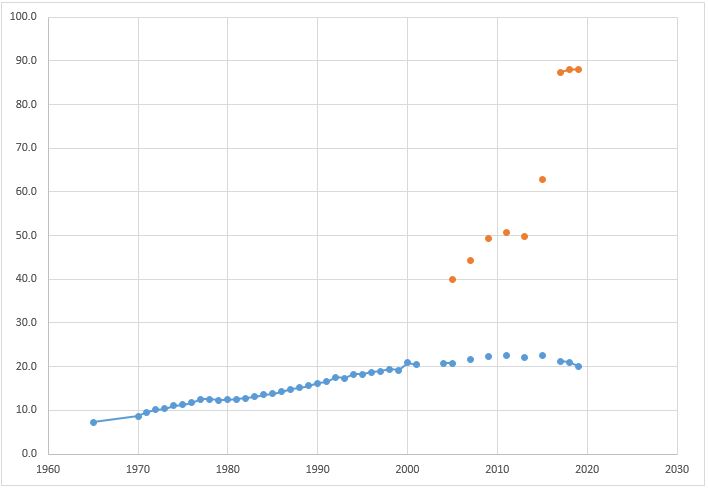

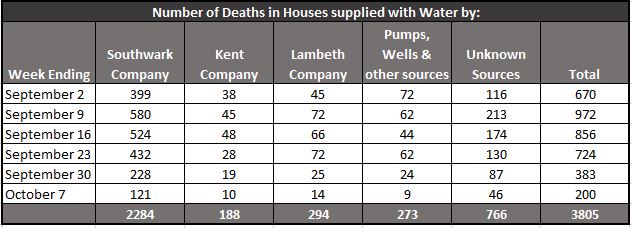

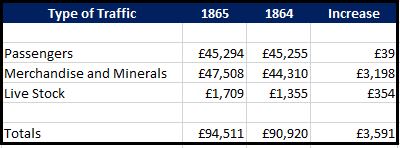

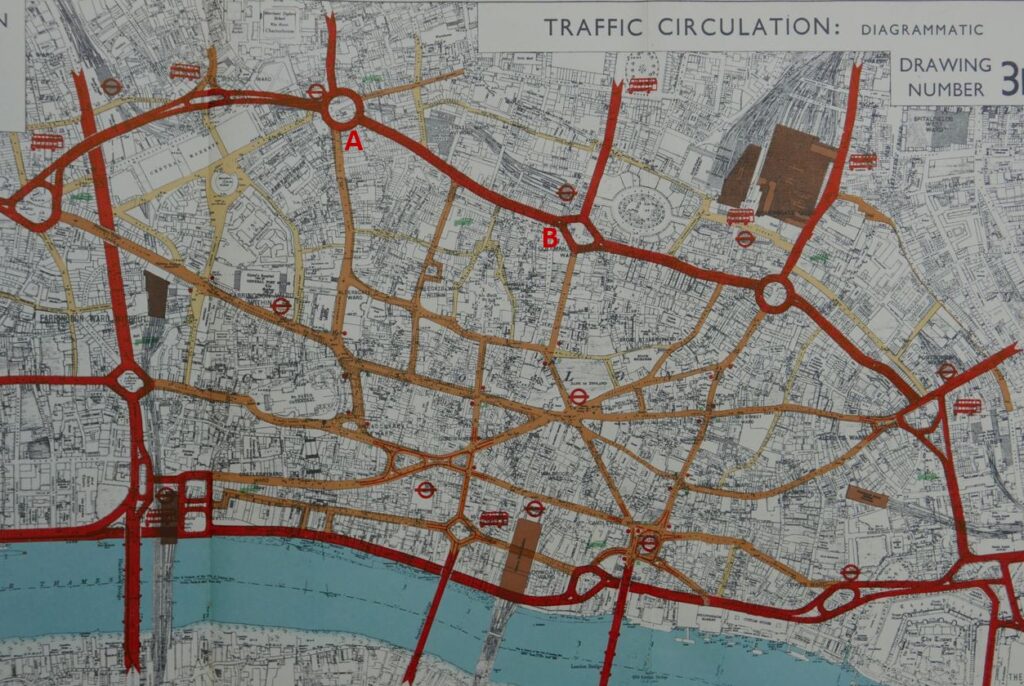

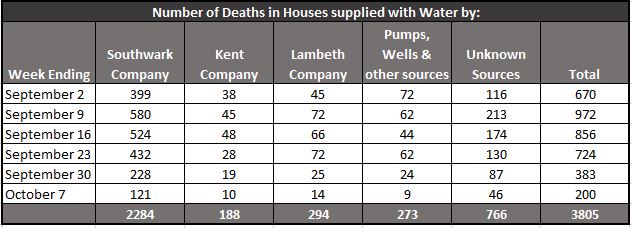

Data recorded by the Registrar General identified the number of deaths per week, aligned with the source of water for the house where the person lived, or the death occurred. The following table shows a period of six weeks in 1854. The table focused on south London, an area where there were significant numbers of cholera deaths.:

The table shows the source of the water supplied to each house where there was a death. The “Unknown Sources” column included a large number of houses where the residents did not know where their water came from as the landlord would pay the bill (and therefore they had no control of the source of their water).

The table implies significant problems with the supply of water by the Southwark Company, but this may have been down to a much larger population.

Much of the evaluation of the data was by John Snow. He obtained the addresses for houses where deaths had occurred from the Registrar General, and spent time going house to house to gather more information.

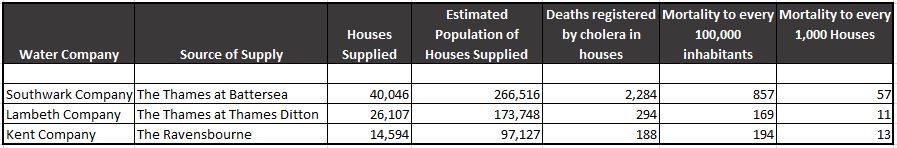

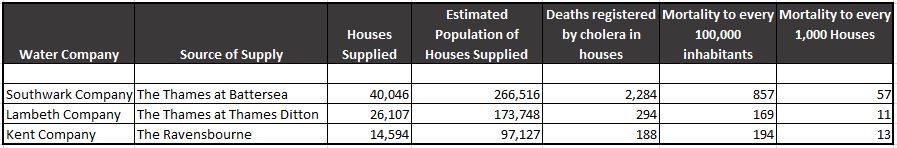

Evaluation of the data enabled a comparison of the mortality rate for each of the water companies to be identified, and this confirmed the issues with the Southwark Company, who had a mortality rate of 857 per 100,000 inhabitants compared with 169 and 194 for the Lambeth and Kent companies:

The Lambeth Company had problems during a previous outbreak in 1849, but had since moved their intake from the Thames upriver to Thames Ditton, which was above the tidal limit of the river at Teddington.

At Thames Ditton, water flowed towards London and there was no wash back in of water due to the tide. This meant that water was less polluted. In central London, there was more inflow of sewage, and this was often swept back in on a rising tide, increasing significantly the level of pollution.

The Southwark Company were still drawing their water from the river at Battersea, not far from a number of sewage outlets at Vauxhall.

Lambeth was the only company to change where they took water following the 1849 outbreak. In 1854, the Southwark Water Company was classed as having the most impure waters, and would not change their water intake till later in the year.

John Snow investigated the source of water used by as many of those who died from cholera as he could find. Some of his records are truly appalling by modern standards:

- At 4, Bermondsey Wall, on 23rd July, the daughter of a bookseller, aged 4 years, cholera 9 hours – Thames water, by dipping a pail in the water

- At Falcon Lane, Wandsworth, on 3rd August, the daughter of a chemist deceased, aged 14 years, premonitory diarhoea 4 hours, cholera 24 hours – Water from a ditch into which cesspools empty themselves

- At Charlotte Place, Charlotte Row, Rotherhithe, July 29th, the son of a barge-builder, aged 3 years, cholera 3 days – Tidal ditch

- At 5 Slater’s Alley, Rotherhithe, July 29th, a labourer, aged 33, cholera 3.5 days – Thames Tunnel water, fetched from John’s Place

Rotherhithe was badly effected. and John Snow mentions Charlotte Row, Ram Alley and Silver Street as “places where the scourge fell with tremendous severity”.

He also states that Rotherhithe had been badly supplied by water for many ages past, and that people were forced to drink from old wells, old pumps, open ditches, and the muddy stream of the Thames.

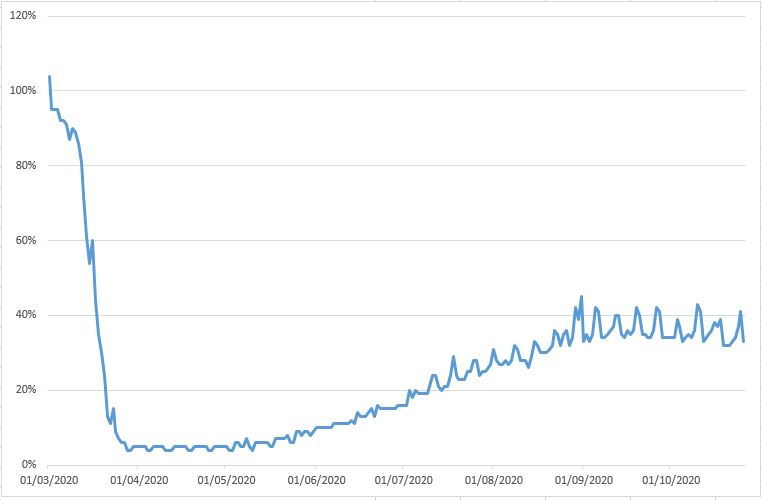

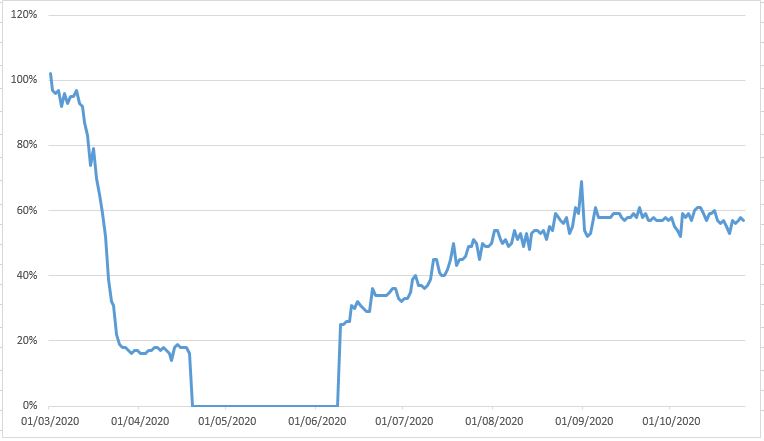

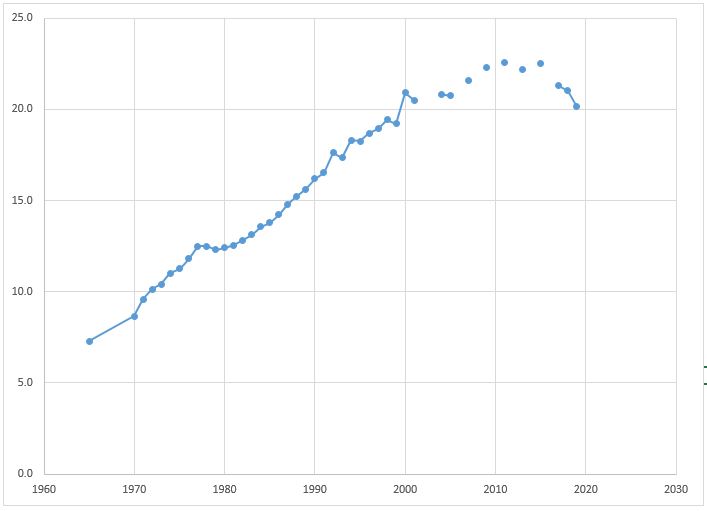

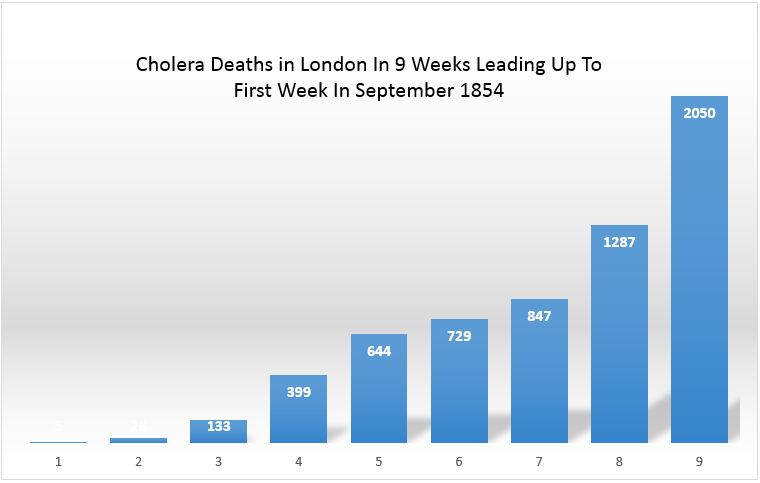

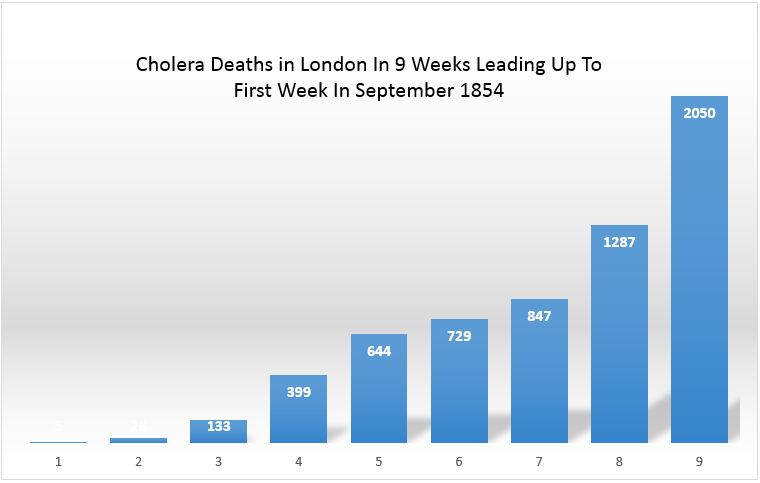

Cholera deaths across London were increasing rapidly during the months leading up to the first week of September. I took the weekly total from the Registrar Generals report, put them in a spreadsheet, and created the following graph which gives a good visual view of the increase.

So in the summer of 1854, cholera was causing deaths across the city, and John Snow was using methods that would become common in epidemiology to understand the impact, and to identify the cause. As well as the cases caused by infected water supplies, the case for which he would be remembered was an outbreak in Soho – a poor area where many of the residents were dependent on water from water pumps.

John Snow investigated the Soho outbreak, and he provided a comprehensive report to the St James, Westminster Cholera Inquiry Committee in July 1855.

Some houses in the area who could afford the cost were supplied by piped water from the Grand Junction and the New River Companies, and in houses that took this water he had found very few instances of cholera. His examination of the water pumps in the streets found the majority had impurities visible to the naked eye. Residents of Broad Street had also informed Snow that water from their local pump had an offensive smell.

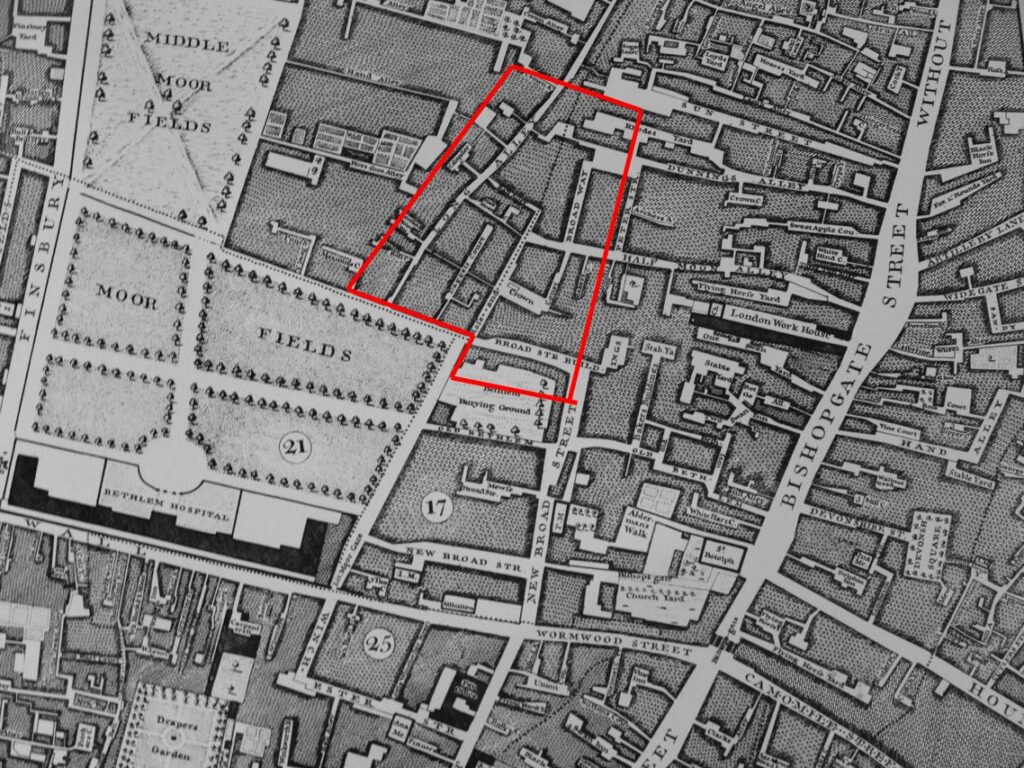

At the start of his investigation, Snow requested data on deaths from the General Register Office. He found that the majority of these deaths had taken place near the Broad Street water pump, and after interviewing many of the residents found that those who had died from the disease had regularly drank water from the pump.

There was no other major outbreak in the area, and the common factor was the Broad Street water pump, so on the evening of Thursday 7th September 1854, John Snow had a meeting with the Board of Guardians of St James’s Parish and presented his findings. As a result, the handle of the pump was removed on the following day.

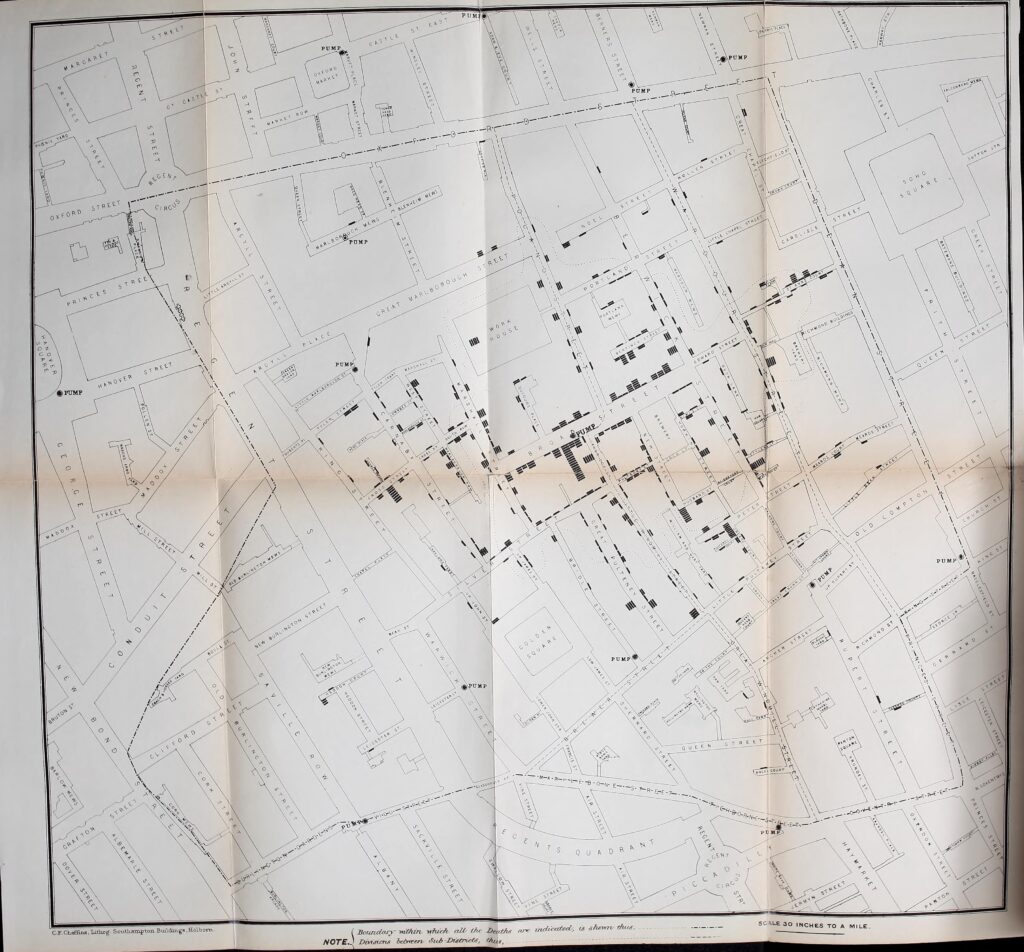

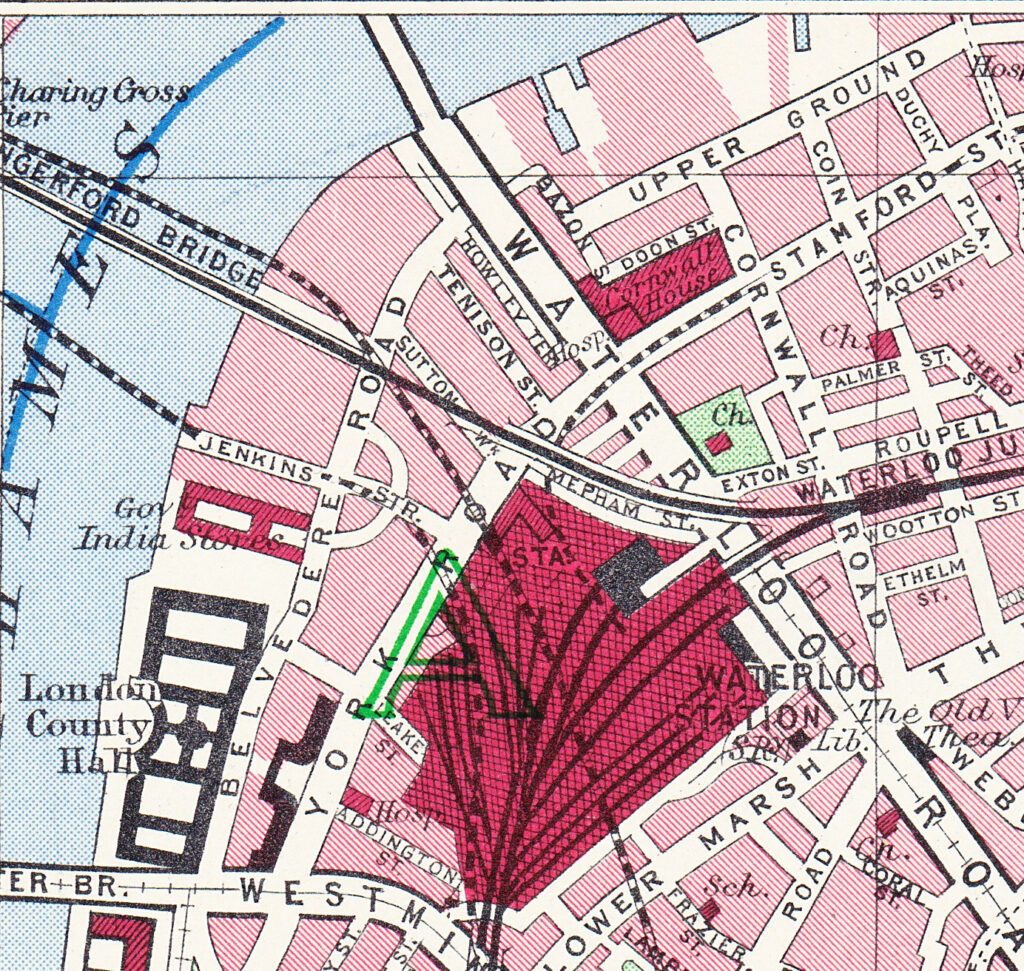

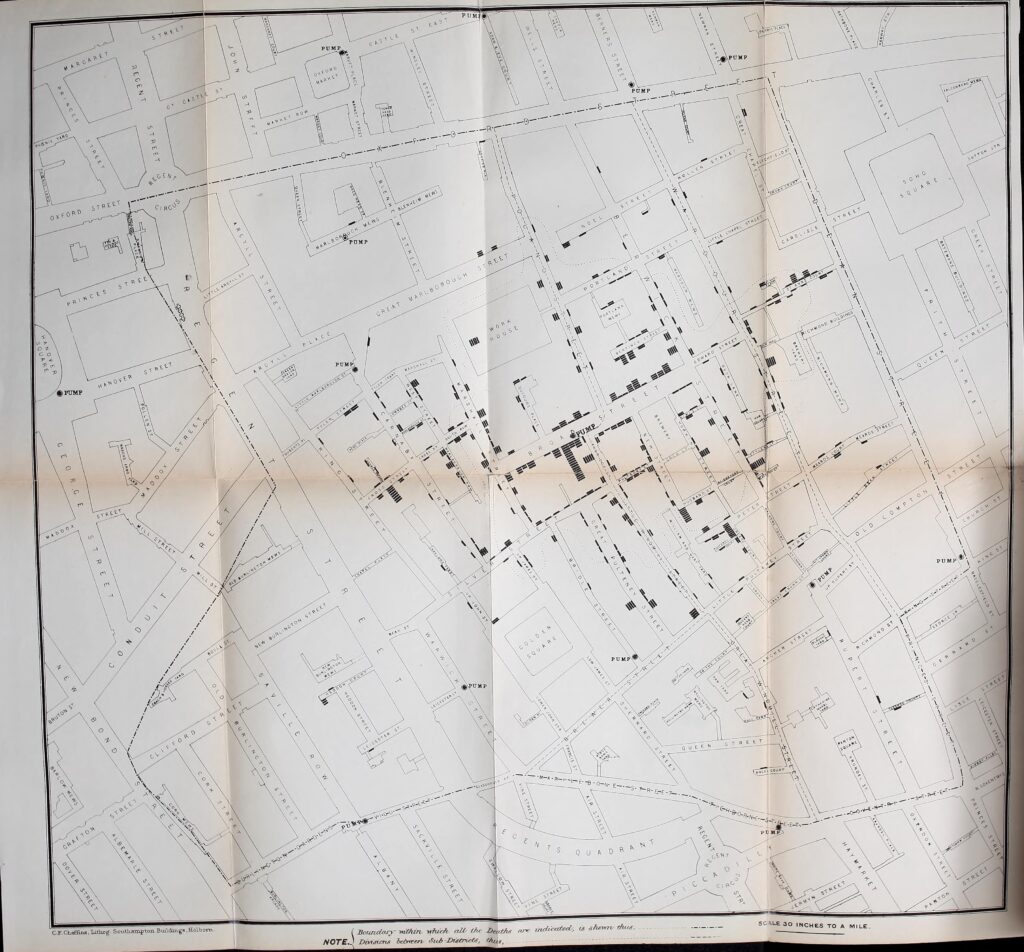

John Snow plotted cholera deaths on a map of the area, with the number of bars representing the number of deaths at each location. The Broad Street pump was close to the long dark line just to the right of centre of the map.

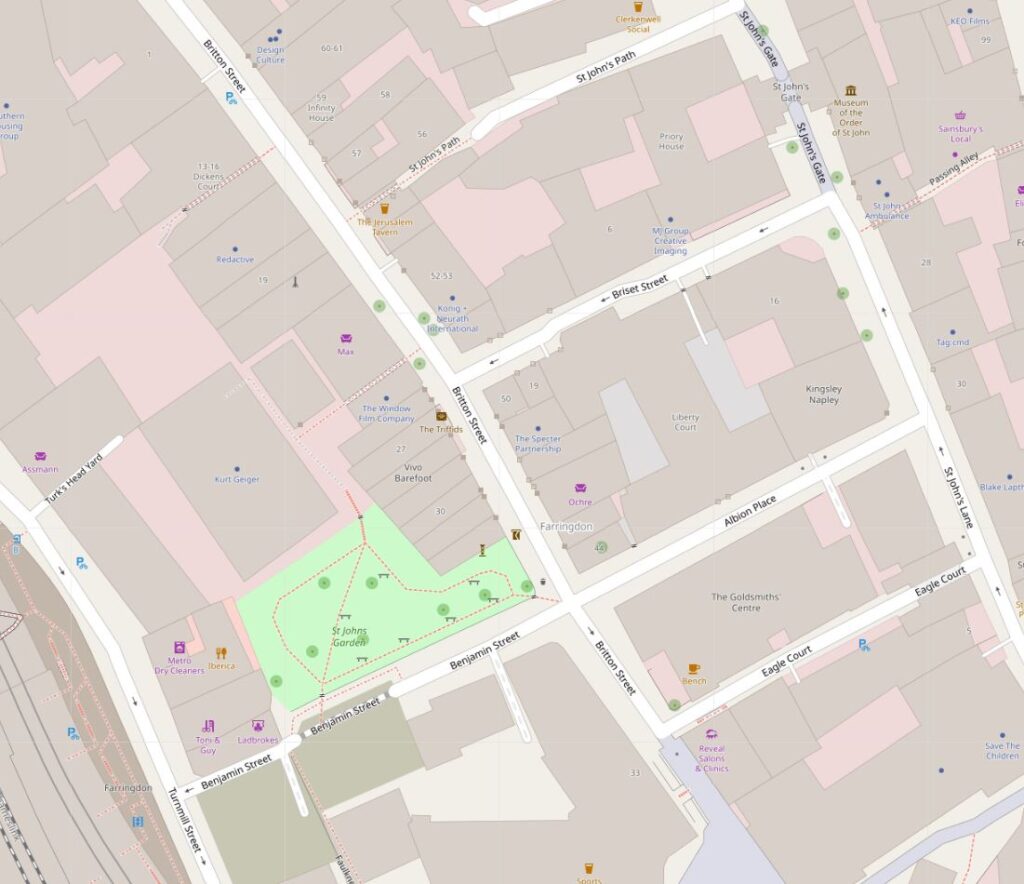

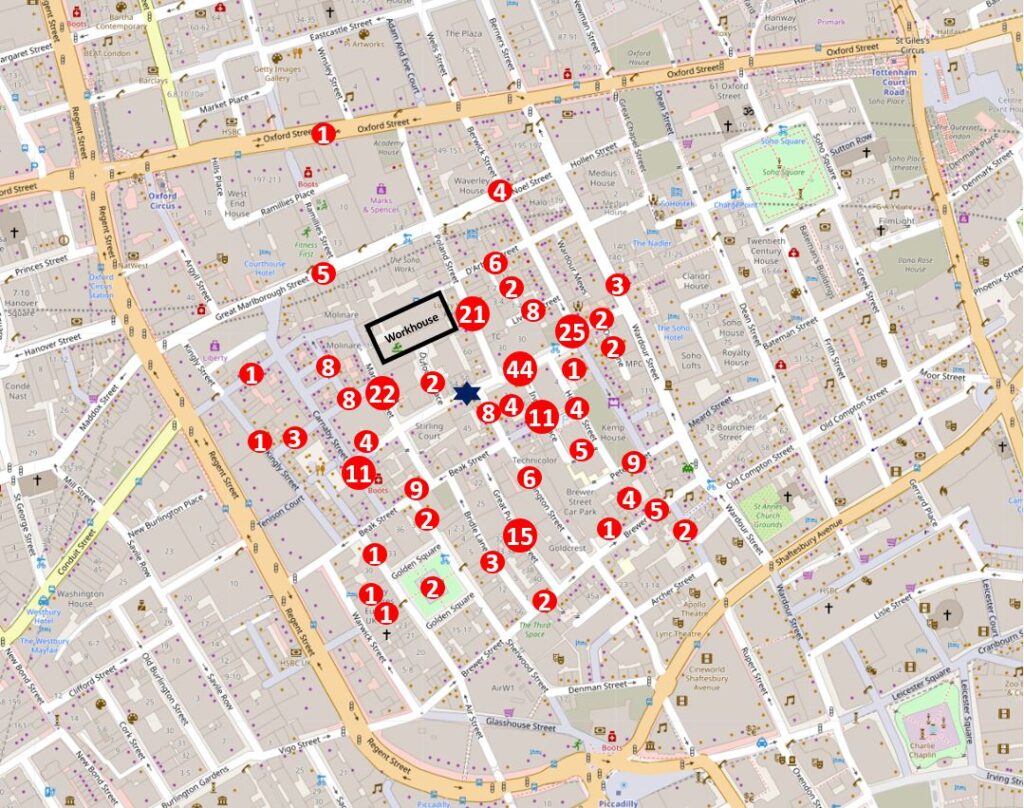

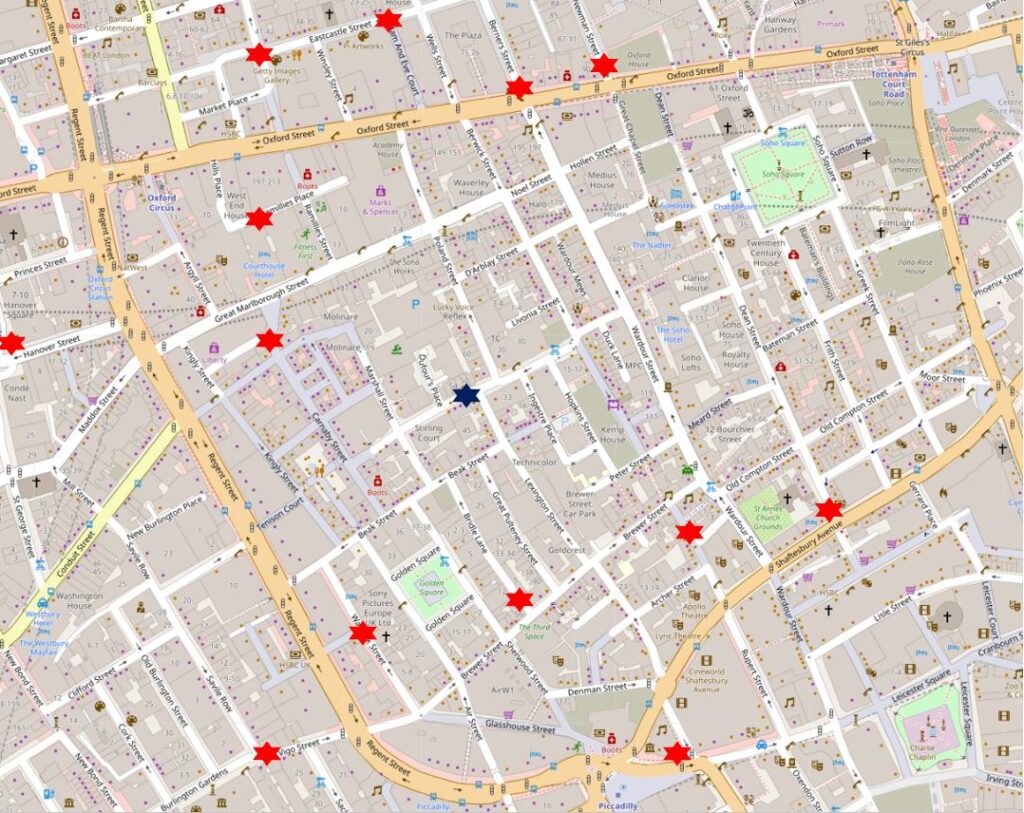

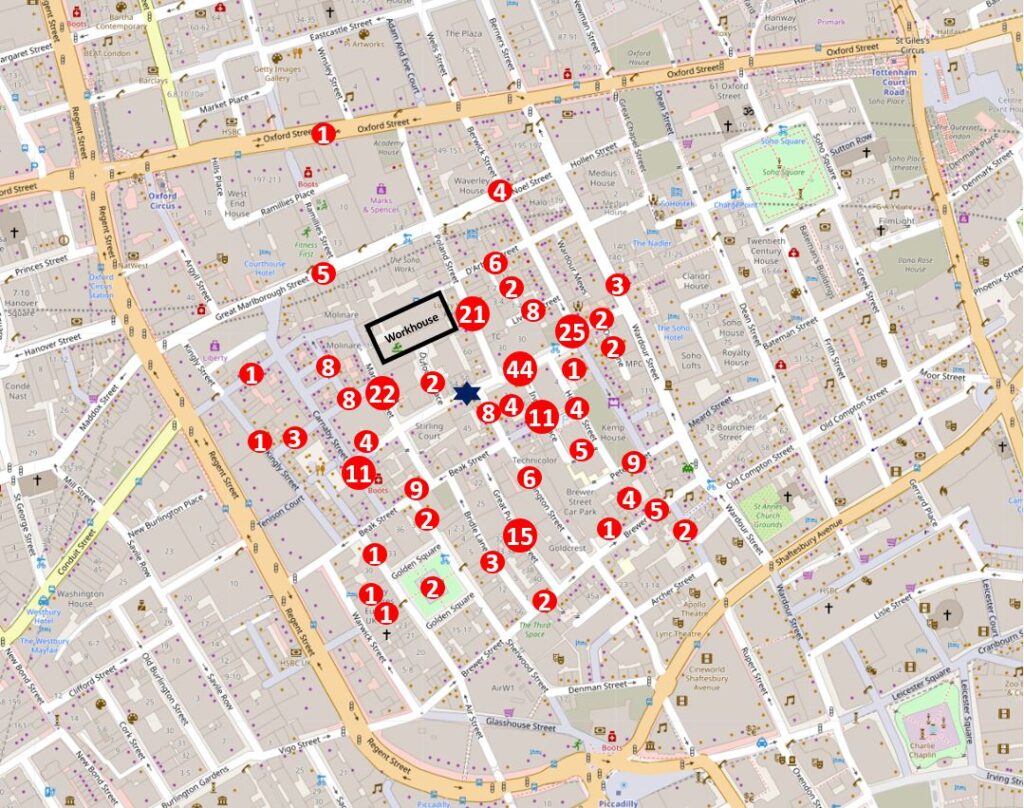

Many of the street names have since changed. To show the number and spread of deaths on a street map of today, I have plotted the numbers on the map below. The dark blue star in the centre is the location of the pump. The numbers represent the total deaths listed for that street, so for example the number 44 to the right of the pump represents the total number of deaths in Broad Street to the left and right of the pump (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

There were a high number of deaths in Poland Street (21), and many of these occurred at the workhouse which is represented by the black rectangle in the above map.

Some of the deaths recorded by Snow at the workhouse are really sad, as often these would be recorded as “female unknown, age unknown”.

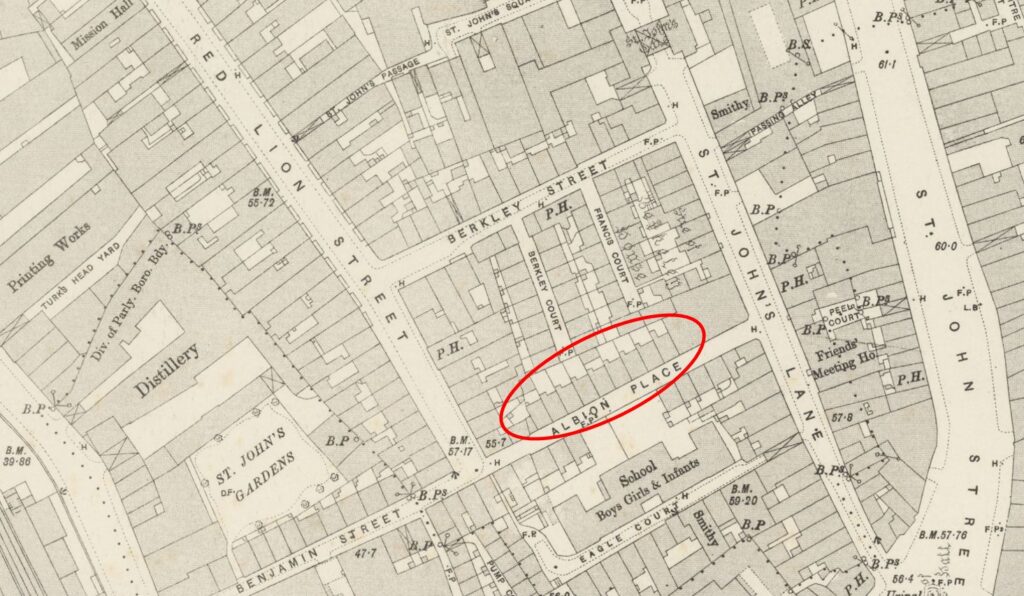

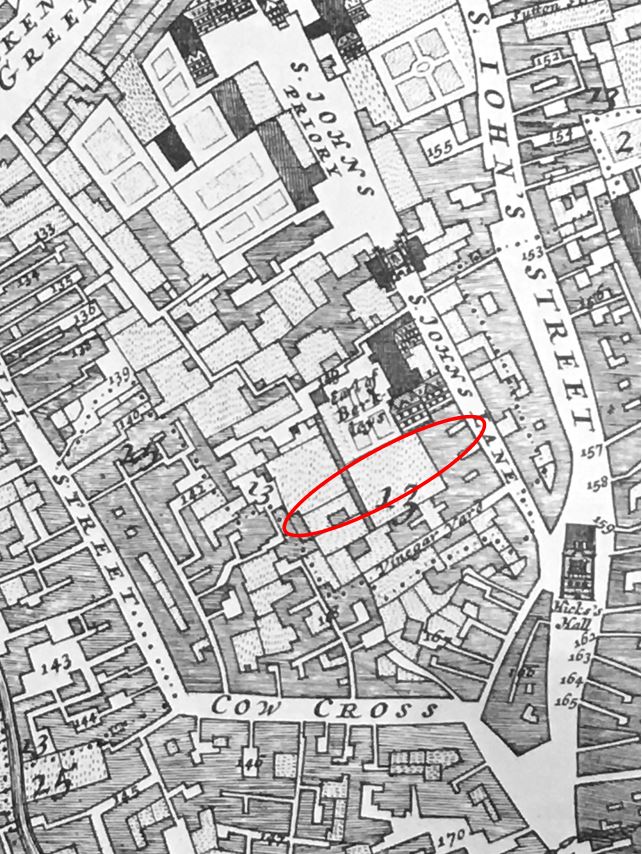

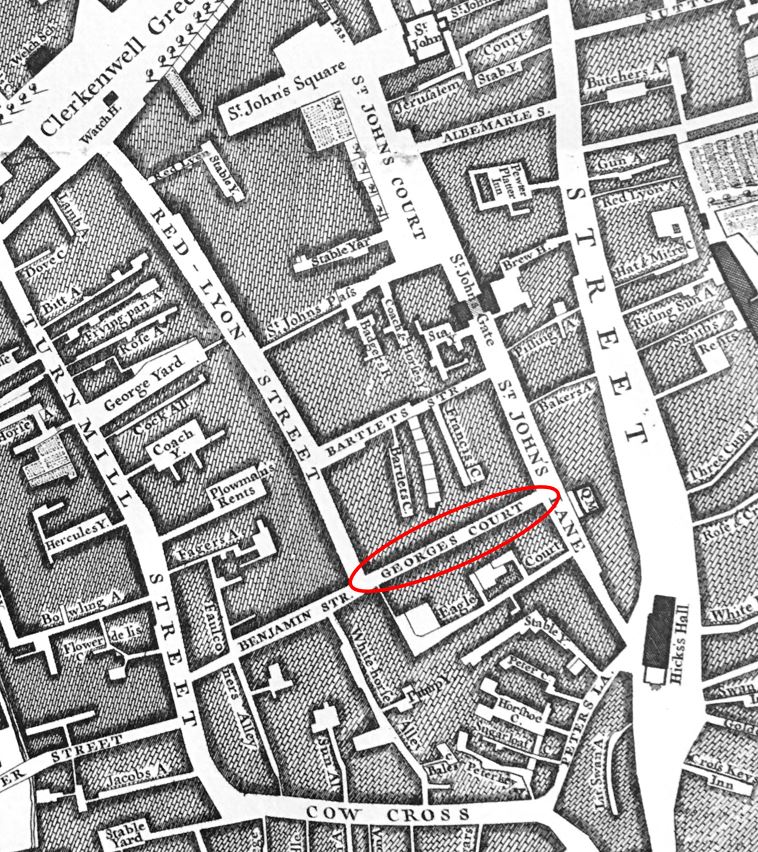

The workhouse is also shown in this extract from the 1894 Ordnance Survey map. The pump is again marked by the dark blue star. A short distance to the right is another building that demonstrated to John Snow that the pump was the source (‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’).

None of the workers at the Lion Brewery caught cholera, despite being in the centre of the outbreak. On interviewing those at the brewery, it was found that “none of the workers drink water” – so perhaps they only drank beer.

John Snow wrote to the Medical Times and Gazette, describing his findings:

“I had an interview with the Board of Guardians of St. James’s parish, on the evening of the 7th, and represented the circumstances to them. In consequence of what I said, the handle of the pump was removed on the following day. The number of attacks of cholera had been diminished before this measure was adopted, but whether they had diminished in a greater proportion than might be accounted for by the flight of the great bulk of the population I am unable to say. In two or three days after the use of the water was discontinued the number of fresh attacks became very few.

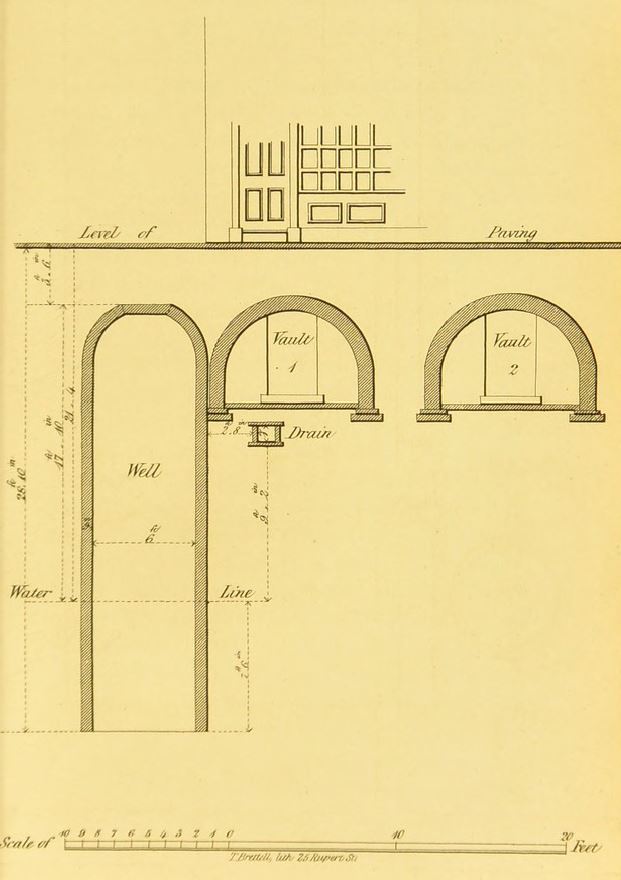

The pump-well in Broad-street is from 28 to 30 feet in depth and the sewer which passes a few yards away from it is 22 feet below the surface. the sewer proceeds from Marshall-street, where some cases of cholera had occurred before the great outbreak.

I am of the opinion that the contamination of the water of the pump-wells of large towns is a matter of vital importance. Most of the pumps in this neighbourhood yield water that is very impure; and I believe that it is merely to the accident of cholera evacuations not having passed along the sewers nearest to the wells that many localities in London near a favourite pump have escaped a catastrophe similar to that which occurred in this parish. ”

The lack of a handle on the replica pump we see today is a reminder of the work by John Snow to get the handle removed.

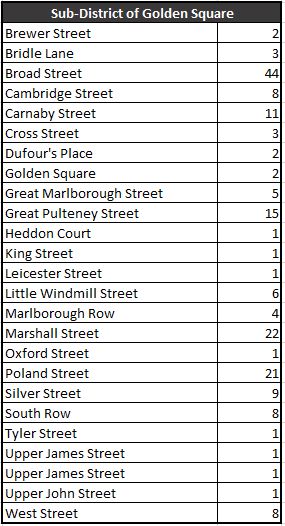

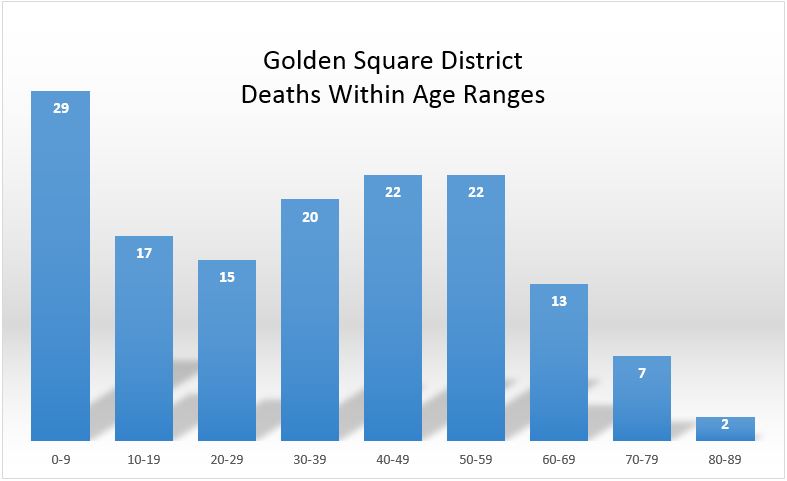

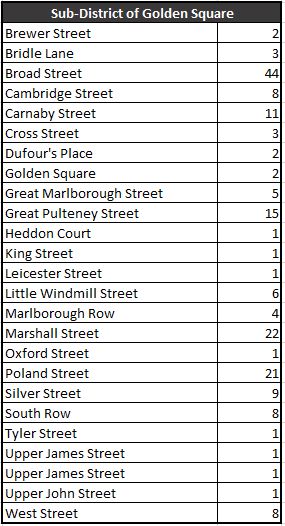

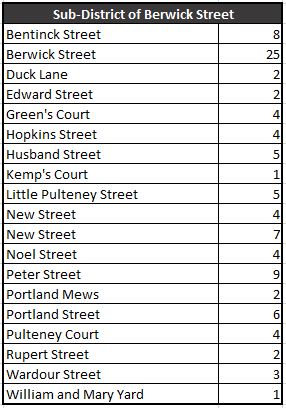

The affected area formed the sub districts of Golden Square and Berwick Street. The number of deaths for each street in these two districts are shown in the following tables:

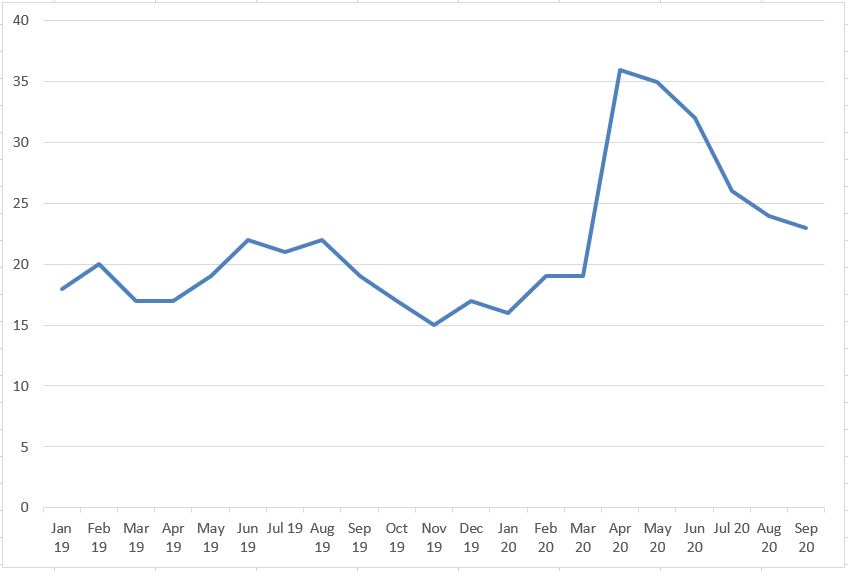

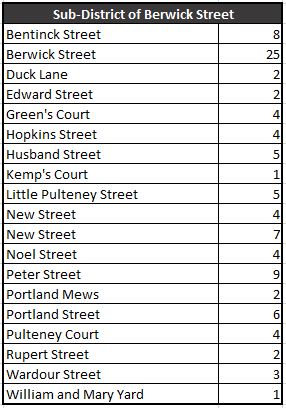

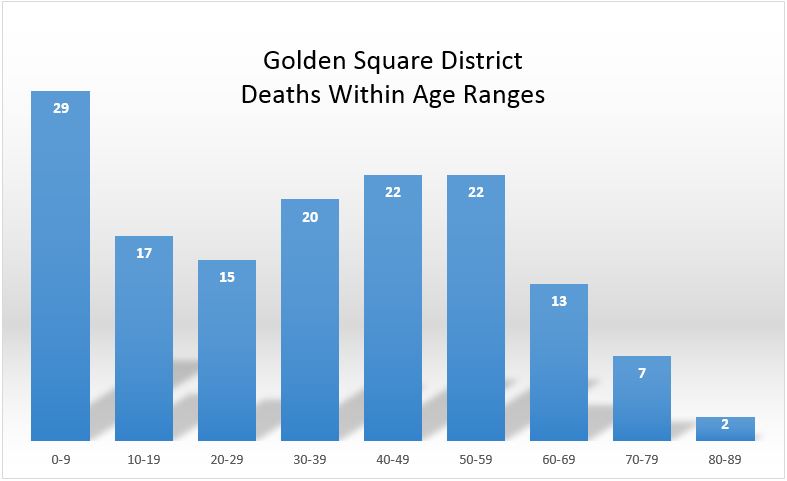

There is other interesting data to be extracted from the Registrar General’s lists. They also include the age of each of those who had died (where known). I extracted these to a spreadsheet, sorted and created the following graph to show the numbers that died within each age range.

The fall off at later ages is not a reflection of reduced impact of cholera, rather there were fewer people to infect in these age groups – London was a young city.

This is reflected in the high death rate of those aged between 0 and 9 years. The reduction between the ages of 10 and 29 was a surprise as there would be more people of these age groups in the area. Perhaps people of these age groups worked away from the pump, were not at the stage when they were in the workhouse, or perhaps being younger and stronger there was a higher survival rate.

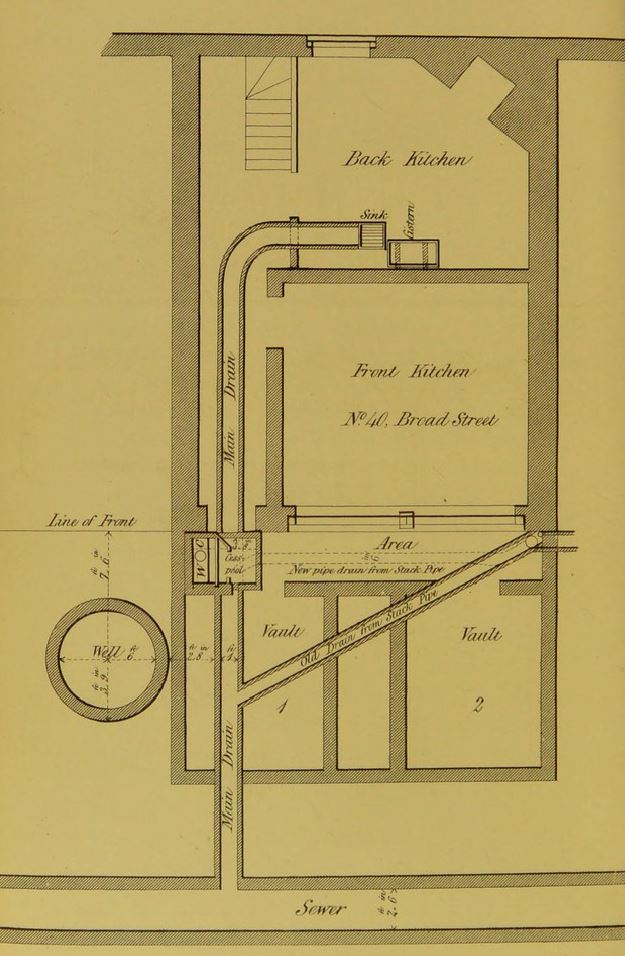

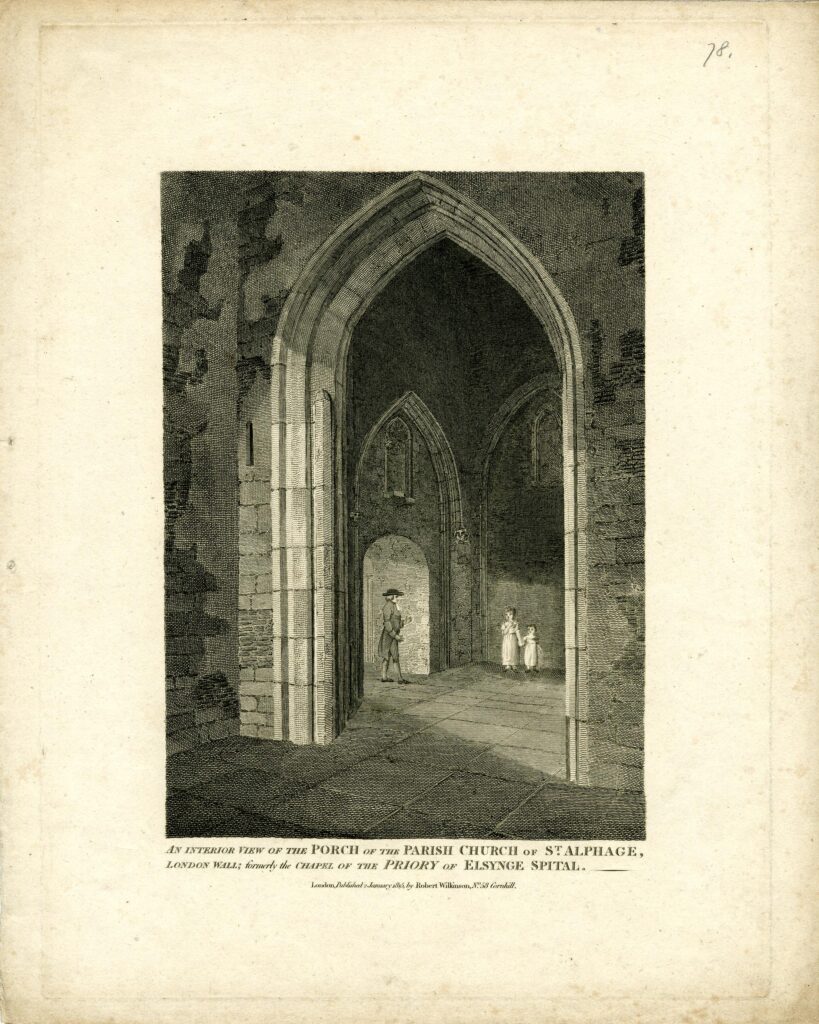

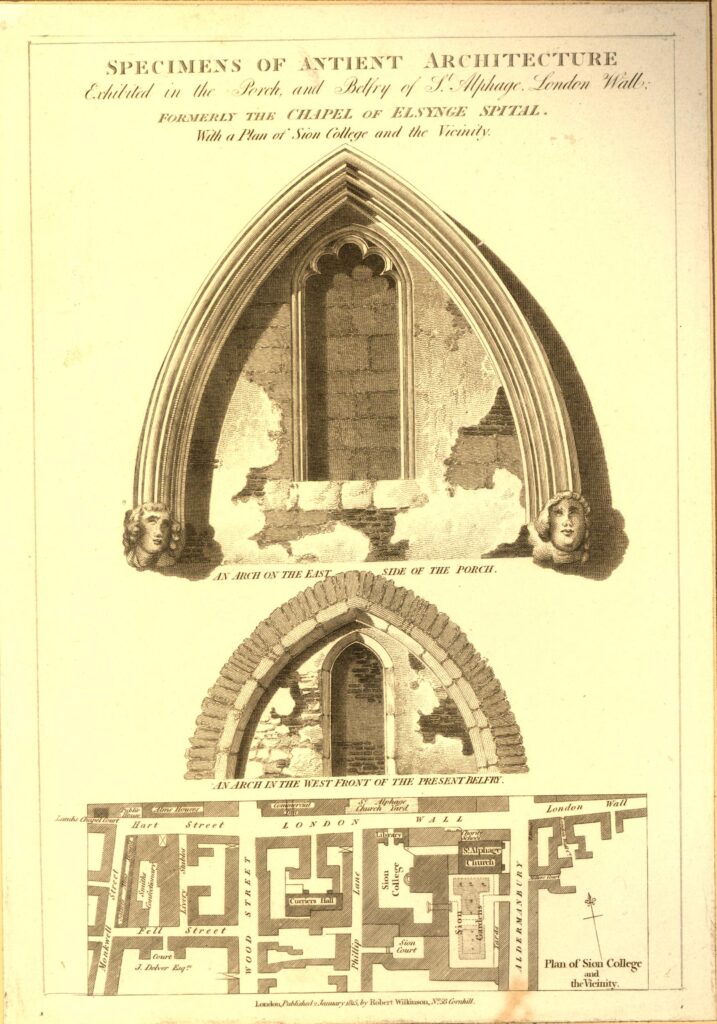

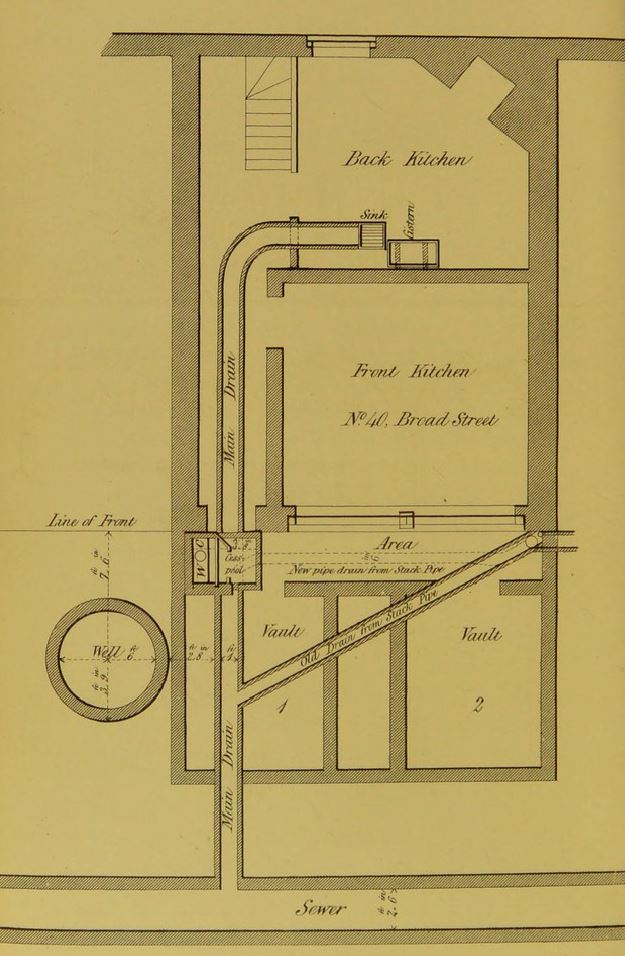

The Westminster Cholera Inquiry Committee in July 1855 included a detailed investigation of the sewer and water infrastructure in the street and the house closest to the pump. The report produced by the Committee included the following drawing:

The diagram shows how close the drains were to the well. The inquiry also examined the cesspool shown by the front of the house and the well. It found the cesspool in very poor condition, and that the mortar between the bricks of the cesspool had decayed allowing the contents to leak into the ground, only a very short distance from the well.

The diagram shows how close the drains were to the well. The inquiry also examined the cesspool shown by the front of the house and the well. It found the cesspool in very poor condition, and that the mortar between the bricks of the cesspool had decayed allowing the contents to leak into the ground, only a very short distance from the well.

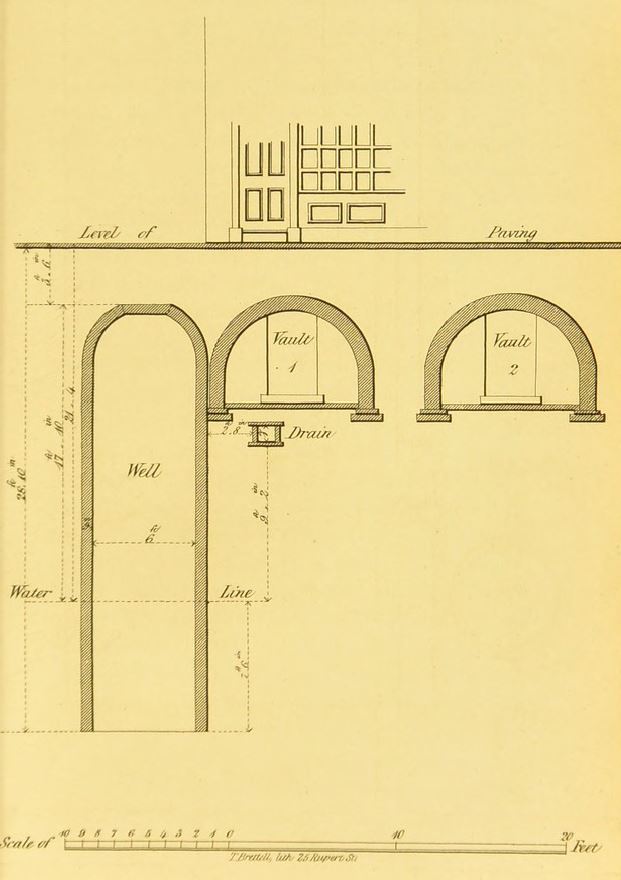

The report also includes the following drawing showing the front of the house, the vaults underneath the pavement, drain and well.

The Westminster Cholera Inquiry Committee report of July 1855 includes a substantial section from the Reverend Henry Whitehead who was assistant curate of St Luke’s Church in Soho during the 1854 outbreak. Whitehead had assisted John Snow with many of the interviews of those living in the streets around the water pump.

Whitehead had initially been sceptical about the cause of the outbreak, being a believer of the miasma theory however he came to the same conclusions as Snow, and was very diligent in his research and interviews of the population.

In his report to the committee, Henry Whitehead recorded the challenges of follow-up research as so many people had moved out of Broad Street, and that approaching the summer of 1855 there was a general feeling of uneasiness in the street – concern that cholera would once again return with warmer weather.

Henry Whitehead identified two houses opposite the pump. One had deaths from cholera and confirmed that they took water from the pump. The adjacent house used water from the New River Company and had no illness.

Although the initial findings to identify the source of the outbreak concentrated on deaths, the follow-up inquiry found that there were 50 cases where people had survived.

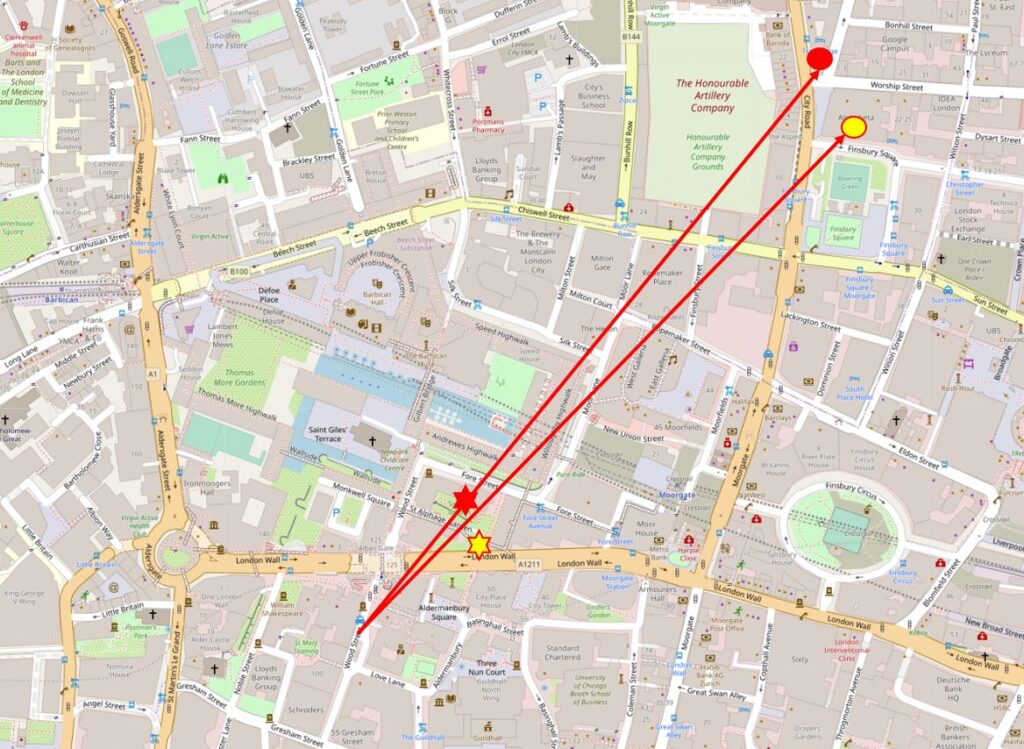

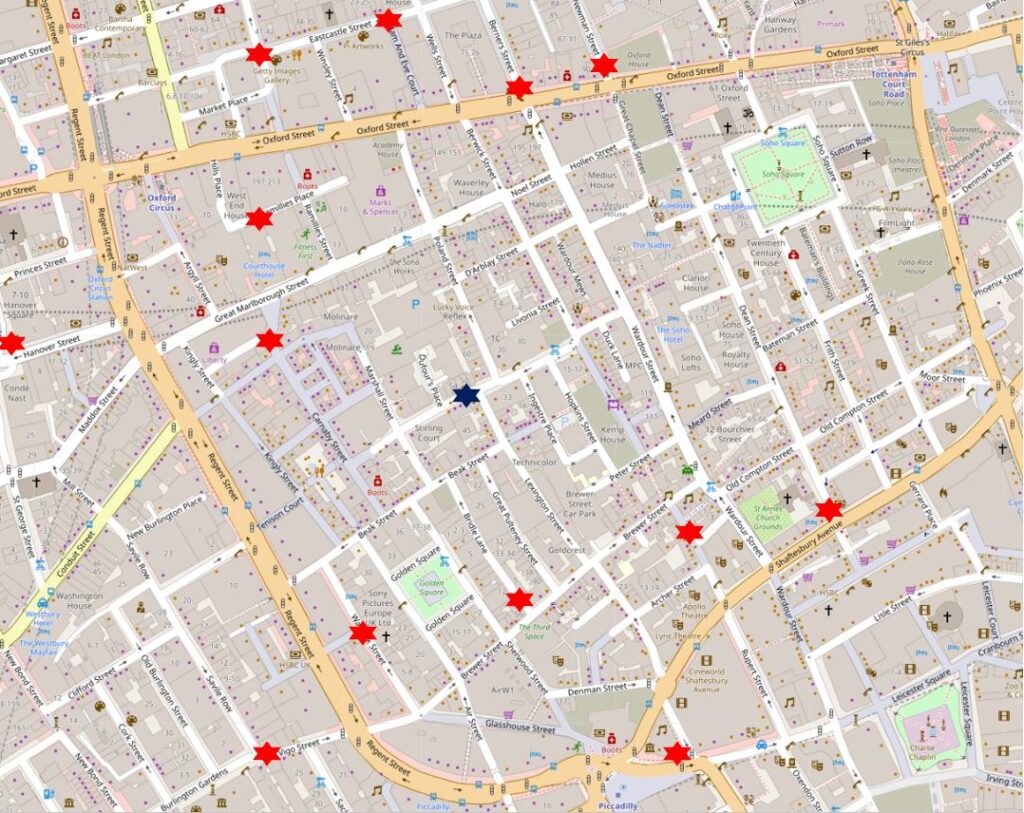

John Snow’s map shows the water pumps of the area. I plotted these on a modern day map to show where the water pumps of 1854 would have been located on today’s streets. Again, the Broad Street pump is the dark blue star, red stars the other water pumps:

Comparing the above map with the map of deaths does again show the high values clustered around the Broad Street pump, with lower numbers as other water pumps became closer.

Broad Street is today named Broadwick Street. the name change happened in 1936 when the eastern section leading to Wardour Street was included – this small section had formerly been called Edward Street (named after Edward Wardour who also gave his name to Wardour Street).

Much of Broadwick Street has changed since the cholera outbreak of 1854, however almost opposite the John Snow pub is a terrace of houses that were there, having been built between 1718 and 1723 as part of the westwards expansion of Broad Street. The terrace is shown in the following photo:

The following photo shows the view looking west along Broadwick Street from close to the Berwick Street junction. The Lion Brewery, which did not have any cholera deaths as none of the workers drank water, occupied the block on the left which now has the brick facing to the upper floors. The brewery was demolished in 1937.

On the corner of Broadwick Street and Berwick Street is the Blue Posts pub. The current rather attractive building dates from a 1914 rebuild, however there had been a pub on the site since the original development of the area, and it is shown on the 1894 OS map.

A rather obscure claim to fame for the Blue Posts pub is that a model of the pub was destroyed by a brontosaurus in the 1925 film Lost World. The following clip shows the pub just before the brontosaurus crashes in and demolishes the building.

Apparently the animators, who created a rather impressive animated film for the 1920s, drank in the pub they chose to destroy for the film.

Lantern over the corner of the Blue Posts pub:

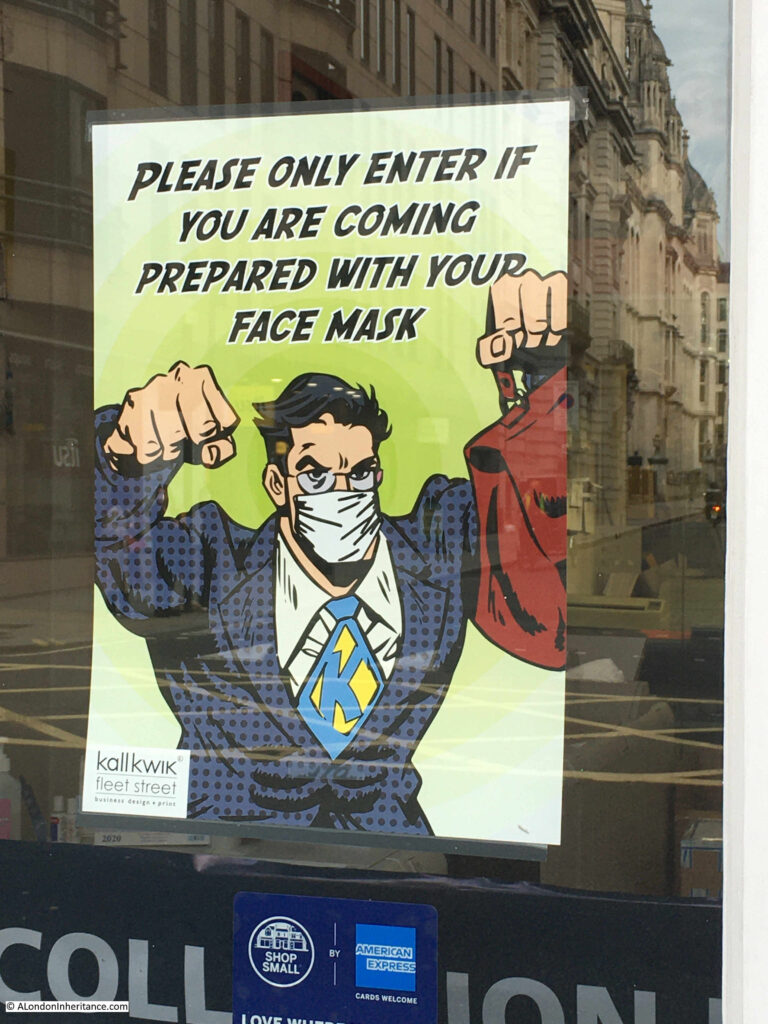

View down Berwick Street showing how a present day pandemic has effected the restaurant trade in Soho:

North western corner of Broadwick Street and Berwick Street with demolished building leaving only the corner façade for inclusion in whatever comes next:

Further back towards Wardour Street, and the following building is on the corner of Broadwick Street (the part that was Edward Street), and Duck Lane, which being towards the Wardour Street end of Broad Street “only” suffered two deaths during the outbreak of 1854.

The ground floor of the building is occupied by the Sounds of the Universe record store:

John Snow’s work was not only around research into the causes of cholera. He was a practicing physician at the Westminster Hospital, and also worked on the technique of anesthesia including how different doses of anesthetic effected the human body.

When Queen Victoria gave birth to Prince Leopold in 1853 and Princess Beatrice in 1857, it was John Snow who administered the obstetric anesthesia.

During the 1854 outbreak he was living at 18 Sackville Street, off Piccadilly. He was a teetotaler and vegetarian for much of his life. He died in 1858 at the young age of 45.

For further reading, the report on the cholera outbreak in the Parish of St. James, Westminster, during the autumn of 1854 can be found in the Wellcome Library collection here.

The second edition of John Snow’s “On the mode of communication of cholera” can be found on Google Books here.

Reading these publications really does make you appreciate the engineering, rules and regulations that are behind the clean water when you do something as simple as turn on a tap.

And the next time an epidemiologist comes on the TV or Radio to talk about the current pandemic, think about John Snow, knocking on doors across London, gathering data on the many cholera outbreaks of the mid 19th century.

alondoninheritance.com