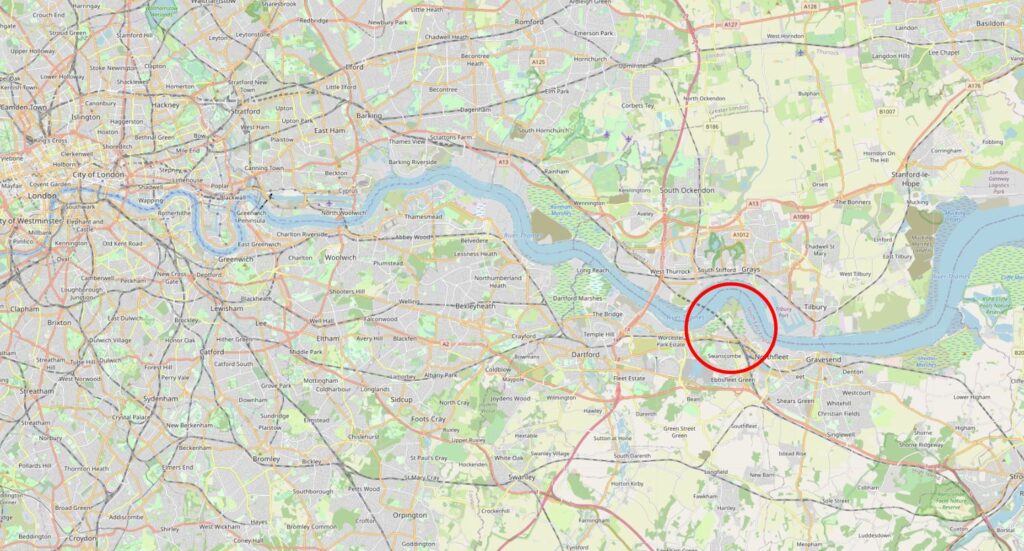

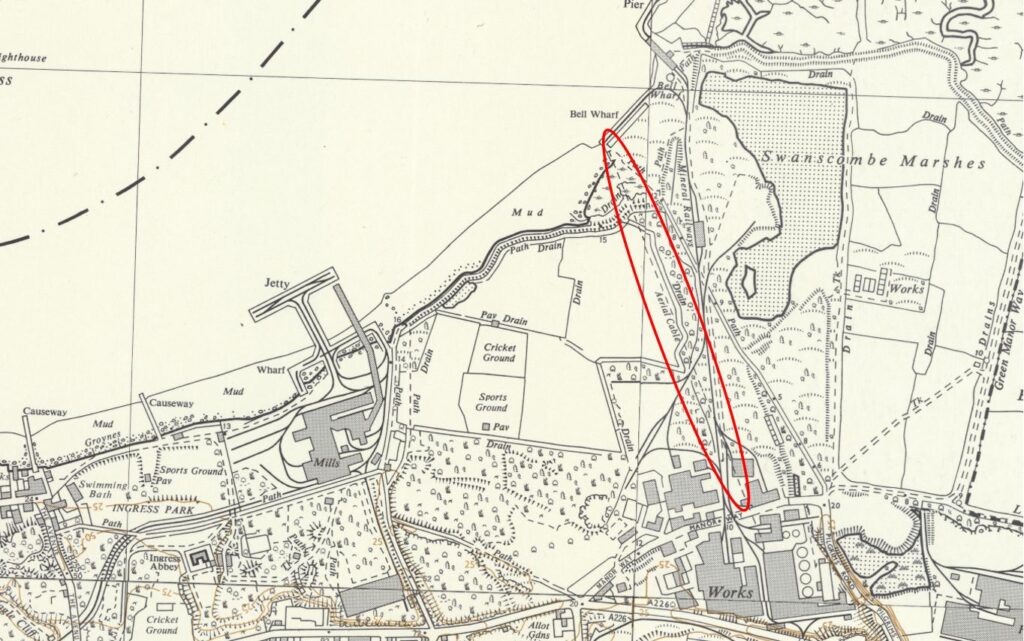

This post continues my walk exploring the Swanscombe Peninsula. The previous post covered the section marked in red in the following map, and this post covers the route in blue, alongside Botany Marsh.

The eastern and southern sides of the Swanscombe Peninsula are more industrialised than the western side, and the noise from these sites is starting to be heard above the breeze blowing through the thick fields of grasses and reeds.

The footpath follows the eastern edge of an area known as Botany Marsh, and the wet nature of the land is very obvious, despite September having slightly less rainfall than the average for the month.

Electricity pole in the marsh:

In the following photo we can see all the infrastructure needed to carry high voltage electricity across the River Thames. On the left is the pylon on the north bank of the Thames in Thurrock, with slightly to the right, the pylon on the peninsula. These two pylons carry the cables across the Thames. In the middle is the tower catching the descending cables and from this tower cables run off across north Kent.

View to the south west across Botany Marsh. More water and the chalk cliffs which are the boundary to the south western edge of the peninsula.

The Swanscombe Peninsula has long been the site for large industrial companies that needed access to the river for transport of raw materials, and space for large processing plants. One of these companies in operation today is the Cemex Northfleet Wharf and Concrete Plant:

The concrete plant has a wharf on the eastern edge of the peninsula where the raw materials for the manufacturer of concrete, aggregates, asphalt and mortar are landed.

Looking in the opposite direction and the peninsula is still wild and wet. Fortunately I did not need to take this footpath.

The western side of the peninsula is more open, however walking along the eastern edge of Botany Marsh, and there are some lovely stretches of footpath, with banks and tall bushes on either side. It feels like walking in the depths of the countryside rather than a site with industry, a Greenhithe housing estate and the Thames all a short distance away.

However evidence of industry along the edge is not far away, and the noise of lorries running to and from the plant now compete with the breeze through the grasses.

This adds to the wonderful contradictions of the peninsula. look one way to see industry, look the other to see the most wonderful landscapes, with Botany Marsh really living up to its name:

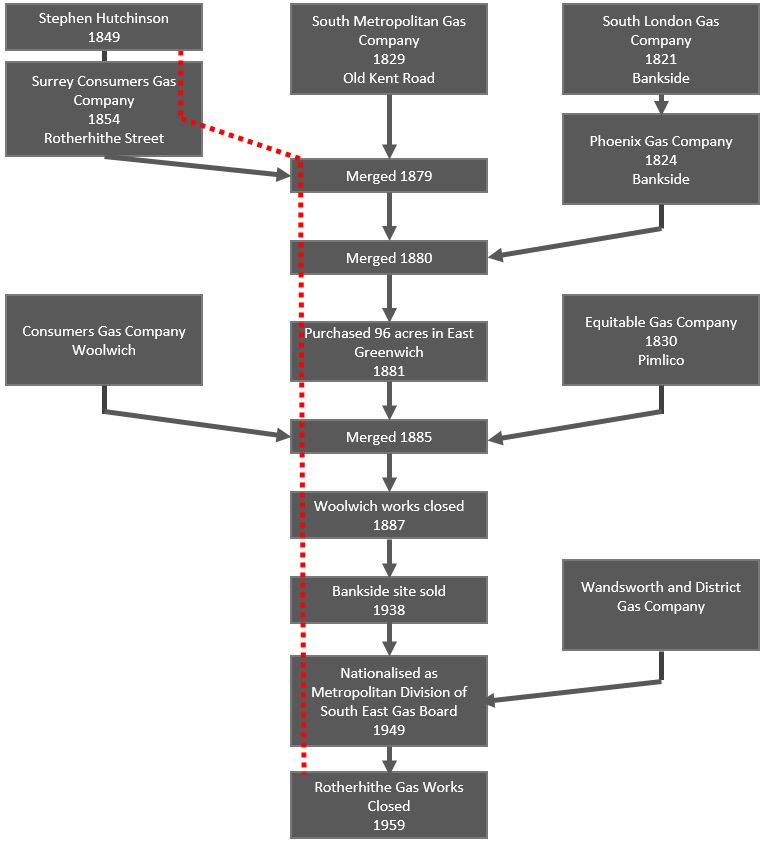

The road that provides access to the industrial areas also provides access to the peninsula, with some limited parking for cars. At one of these entrances is an information panel which tells how the peninsula is managed, and the wildlife that can be seen on Botany Marsh:

Botany Marsh is subject to land management to maintain the biodiversity of the place. Without management, the land would revert to scrub and woodland. Ditches were cleared and the footpath I have been walking along during this part of the walk was created.

The information panel also explains where much of the water comes from. A system to collect water from 20,000 square metres was installed which increased the water flow into the marshes by up to 10,000 cubic metres a year. The water is run through an oil interceptor to ensure the marsh is not polluted

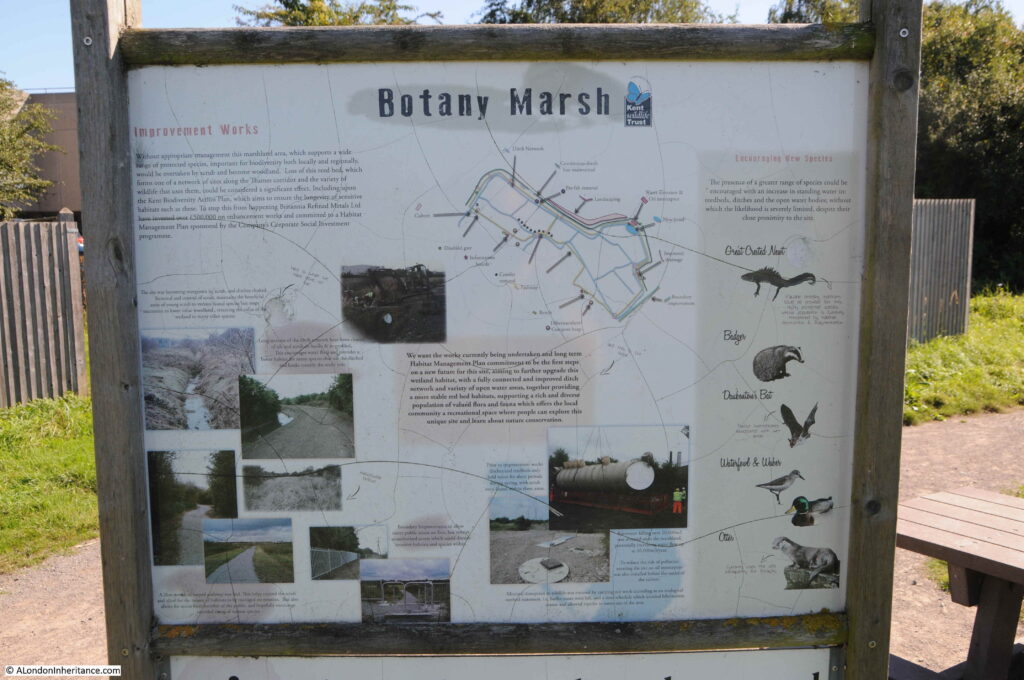

The rear of the panel provides information on the species of animals that can be found across the marsh, many of which have seen a severe decline in numbers over the last couple of decades. Three of the six reptiles native to Britain are found on Botany Marsh (grass snake, slow worm and vivaparous lizard).

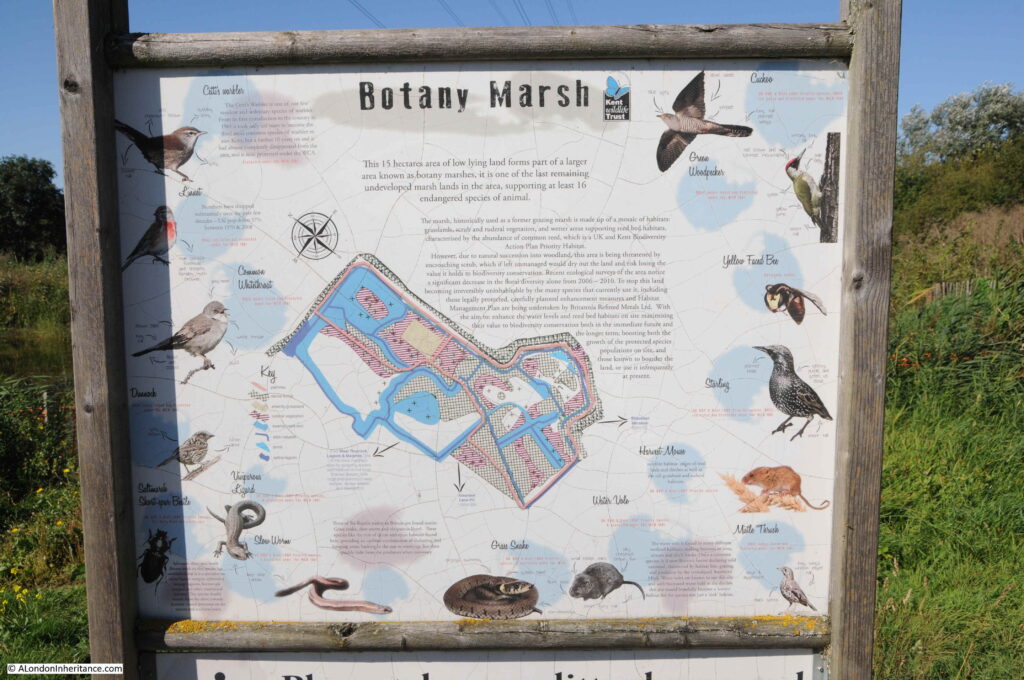

Campaigning to save the peninsula from development has included the need to designate the area as a Site of Special Scientific Interest. The uniqueness of the place, diversity of animal species, the rarity of such a variety of habitats all support an SSSI designation.

In March 2021, an existing SSSI to the south (Bakers Hole – a back filled quarry that was the site of many finds of Stone Age occupation), was extended to include most of the Swanscombe Peninsula.

Consultation on the recommendation to extend the SSSI took place between March and July and a recommendation to the Board of Natural England will be made based on the results. The Board then have until the 10th of December 2021 to either confirm or withdraw the recommendation.

The London Resort are looking at ways that this recommendation can be withdrawn or accommodated within their plans, so the outcome for both the London Resort and the Swanscombe Peninsula is not yet clear.

Map and details of the proposed SSSI are on display at all the main entrances to the peninsula:

As well as the Cemex site, another industrial company on the eastern side of the peninsula is Britannia Refined Metals, a company owned by the multinational Glencore. The company specialises in lead, zinc and tin production.

Given the current shortage of HGV drivers, and the poor facilities provided for them, the above photo provides an example. To the right of the photo was a long layby off the road for lorry parking. The blue box behind the site safety sign appeared to be their only toilet facilities.

Britannia Refined Metals was originally formed around 1930 as the Britannia Lead Co. Ltd, and their original brick building is still onsite with the name above what was probably the original main entrance to the site.

After having a looking at the industrial side of the peninsula, I walked back to Botany Marsh to continue south along the footpath.

Old building on the northern edge of the southern industrial area gradually being overgrown:

Although there are some large industrial sites along the eastern side of the peninsula, they are not that visible, apart from the very tall chimney of the Cemex works. More reeds, grasses and water of Botany Marsh.

The path I was following south, then turned towards the west, to loop back inland. I suspect it ended up at the flooded footpath shown earlier in the post, so after a lengthy detour, I turned back to access the road at the site of the Britannia factory.

Following this road south took me through an industrial estate, very similar to those that have traditionally lined the River Thames, but I did not expect to find a number of London buses:

This is the site of London Bus and Truck Ltd – “For All Your Bus, Coach & Commercial Vehicle Requirements” and specialists in Routemaster buses which explains the small fleet of buses in their parking area:

A bit of protection for pedestrians from the many HGV’s passing along the road:

At the end of the road running through the industrial estate, it meets the A226, or Galley Hill Road, and I followed this busy road to head for Swanscombe station. The road runs across the bridge seen in the distance in some of the photos in today’s posts. The height of the road provides a good view across the Swanscombe Peninsula, and also shows where HS1 enters the tunnel under the peninsula to cross underneath the River Thames:

HS1 is the high speed railway running for 108km between Paris and St Pancras Station. Regular services started on the route on the 14th November 2007. The entrance on the Swanscombe Peninsula is the start of a one and a half mile tunnel under the Thames.

There are industrial sites lining the southern end of the peninsula, on either side of HS1. These industrial sites are also included in the land required by the London Resort. As development has extended east along the Thames from central London, many of these industrial estates have been closed and built over with housing. They are though a much needed part of economic infrastructure.

The view from the bridge shows what appears to be grass and bushes over the northern part of the peninsula. It is not really possible to appreciate the natural diversity of the place from this viewpoint and a walk through the site is needed.

The London Resort describe one of the benefits of their proposals as the regeneration of what is largely a brownfield site. This is true, the peninsula has been the location of both industry, the infrastructure needed to support these industries and connect them to the river, along with the dumping of waste from these industries. However just describing Swanscombe Peninsula as a brownfield site does not fully appreciate the site today. A site which has been considerably reclaimed by nature, is home to many endangered species and also retains that sense of isolation that was so prevalent across much of the land along the river to the east of London.

I also like the industrial sites that are found on the east side of the peninsula. They are there because of the river, the river that has transported so many raw materials and finished products across the centuries.

The road bridge taking Galley Hill Road over HS1. This was the exception when there was no traffic. During my walk along the road there was an almost continuous line of cars and lorries.

The River Thames is always in the background around the peninsula, with shipping moored at, and travelling past Tilbury visible:

From the bridge we can view the chalk cliffs that line part of the south western edge of the peninsula:

There are a number of chalk pits on the peninsula, and the wider Swanscombe area is one of Europe’s most important Paleolithic sites (500,000 BC to 125,000 BC). Finds in the area include hand axes, and what became known as the Swanscombe Skull, which was excavated in Barnfield Pit, a short distance south of the peninsula (part of the extended SSSI). The area also includes evidence from some of the temperate periods between periods of glaciation, or ice ages.

The skull was discovered in 1935 by Alvan T. Marston, one of the many archaeologists who had been working in Swanscombe. He described the discovery as follows:

“For nearly half a century, archaeologists have known the high terrace gravels at Swanscombe, Kent, and in that time have found hundreds of thousands of the early Stone Age hand axes belonging to the Chelles-Acheulean stage, but the constant hope that skeletal remains of the makers of those implements might be found did not become fact until June 1935, when I discovered a human occipital bone 24ft below the surface in the middle gravels of the Barnfield Pit. Nine months later a second bone of the same skull was found, the left parietal, in the same seam of gravel and at the same depth below the surface. The two bones were 8 yards apart, many tons of sand and gravel having to be excavated and examined to bring the second bone to light, and this work is still going on.

Swanscombe is not homo sapiens. It is, as its geological horizon shows, a pre-Neanderthal hominid.”

The Swanscombe Skull © Natural History Museum:

And with that diversion, I reached Swanscombe station, ready for the train back to Waterloo East:

This is the first time I have been to Swanscombe Peninsula. No doubt the weather helped with first impressions, however it was a fascinating walk through such an interesting area.

This is a place that is incredibly unique. Fresh water marsh to the south and salt water marsh to the north has created different environments, with a wide variety of animal species populating the peninsula.

The peninsula is also very quite, I walked through on a Friday, so it is possibly busier at the weekend, however I saw five people at most, only one close up – a jogger on the eastern side of the peninsula.

Jobs are really important and are needed in north Kent, and it is always a difficult argument, however the planned resort / theme park does seem to be in the wrong place.

It does not occupy the whole of the peninsula, however it would have a dramatic impact on the remaining land. Construction work, drainage, impact on the water table, noise and light would all have an impact on the surrounding environment and animals. Many of these animals are threatened, with, for example, Swanscombe Peninsula being one of only two known places where the jumping spider Attulus distinguendus can be found.

The development would also disrupt the movement of animals between the peninsula and the wider environment.

The board of Natural England have until the 10th of December 2021 to make a decision on the SSSI extension to the peninsula. It will be interesting to see their decision and the impact this may have on plans for the London Resort and the future of Swanscombe Peninsula.

If you get a chance to visit, a walk through Swanscombe Peninsula is a really good day out.

More information on the London Resort (which includes their planning application), the Swanscombe Marshes, and those campaigning against the development can be found at the following links:

The London Resort site is here.

The Save Swanscombe Marshes site is here

And their map with their recommended walking route is here

The Kent Wildlife Trust page on the London Resort development is here.

The Bug Life page on the Swanscombe Marshes is here.

The RSPB page on the marshes is here.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs page with the SSSI documentation is here.

The Natural England page on Swanscombe is here.

A PDF of Natural England’s supporting documentation for the SSSI, including maps, can be found here.