The south bank of the River Thames has changed dramatically over the years, from an industrial environment, to one of leisure, culture and expensive housing. For much of the south bank, from Westminster Bridge to Tower Bridge, there is very little evidence of these pre-war industries, and their close relationship with the river.

As with much of the Thames as it if flows through the city, this stretch of the river was lined with numerous stairs, providing access to the river from the streets and buildings that ran alongside. It is still possible to find many of these, but there is one lost set of stairs that are the subject of this week’s post – searching for Emerson Stairs in Bankside.

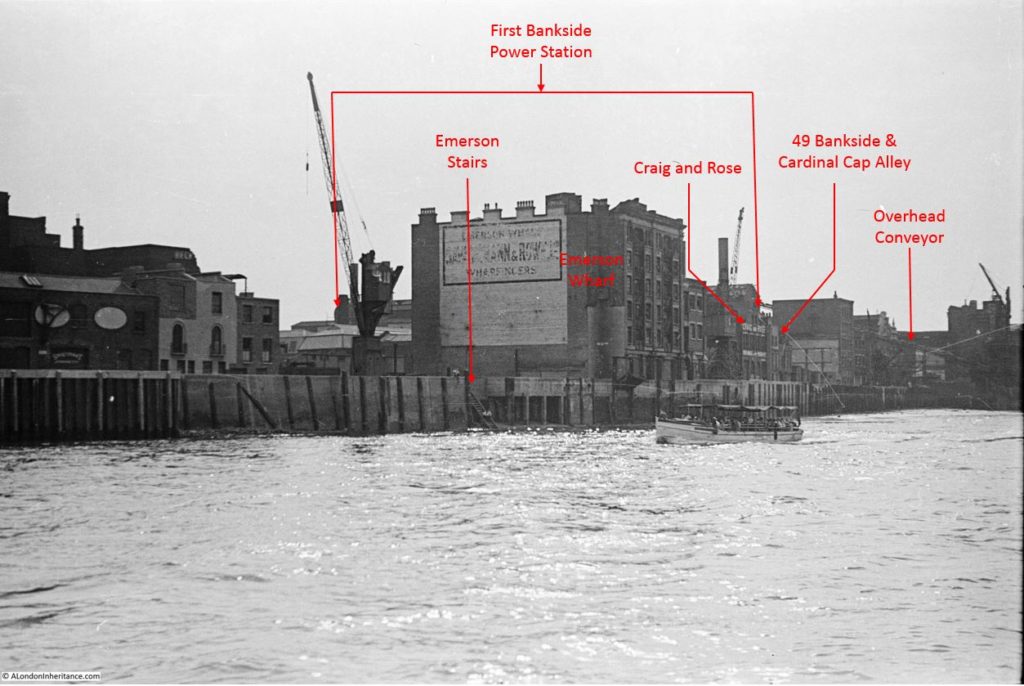

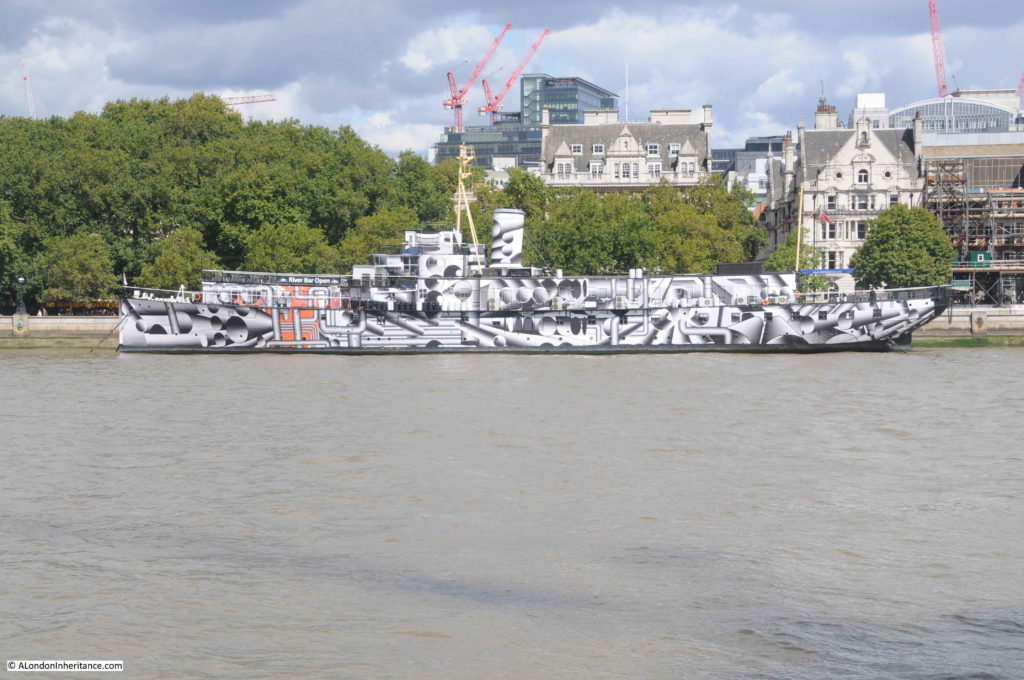

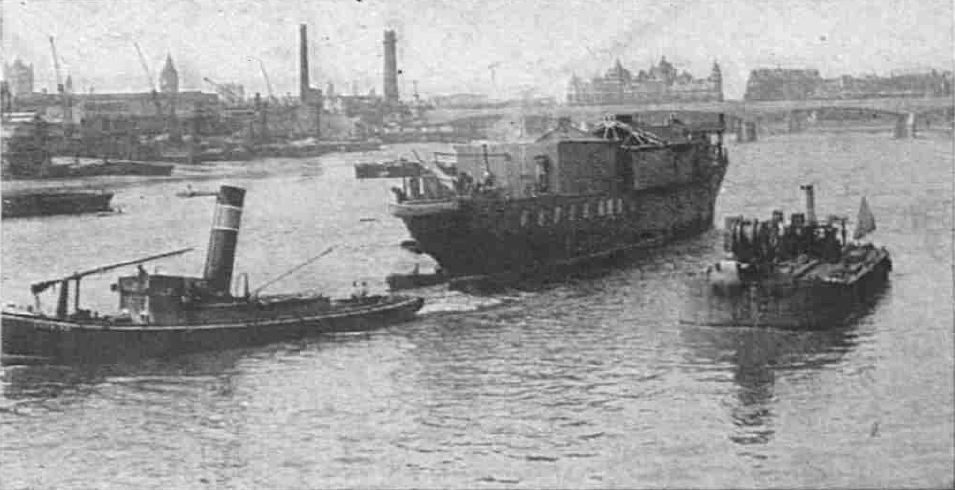

This is one of my father’s post war photos of the south bank:

At first glance, there is not much in the above photo to identify the location today, but there are many pointers which I will explain as I work through the post, but as a starter, this is the same scene today:

The perspective is slightly different between the two photos, as my father was in a boat on the Thames, and I was standing on Southwark Bridge, but the area covered is much the same in the two photos.

The main clue to the location in the original photo is on the sign on the large building in the centre of the photo, which in fading lettering identifies the name as Emerson Wharf.

This building is on the site that would become the Globe Theatre, and in the following photo I have added some of the key landmarks and features visible in the photo:

And in the photo below I have added the location of the original buildings to the 2019 photo:

The only features that remain today are the old houses at 49 Bankside and on the opposite side of Cardinal Cap Alley, although these are behind the trees in the 2019 photo.

The original Bankside Power Station, which was a longer, but thinner building to the 1950s replacement (now Tate Modern) is behind Emerson Wharf, and all the infrastructure between power station and river, including the coal conveyor belt which can be seen in the original photo, have long gone.

One of my many side projects is tracing all the Thames stairs, and in the centre of the photo there is a new one for me to add to the list.

Just visible are a set of stairs leading down from the river, from a small cut into the embankment, and there appears to be a couple of people sitting on the stairs looking out over the river. I have labelled the stairs in the original photo above.

The following photo is an enlarged extract from the original photo showing the stairs (the best quality image I could get from a 72 year old 35 mm negative):

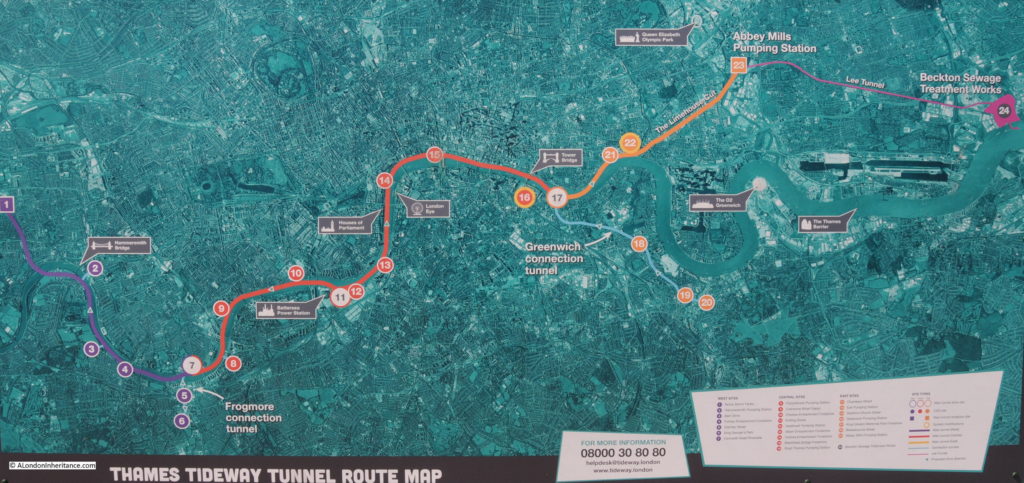

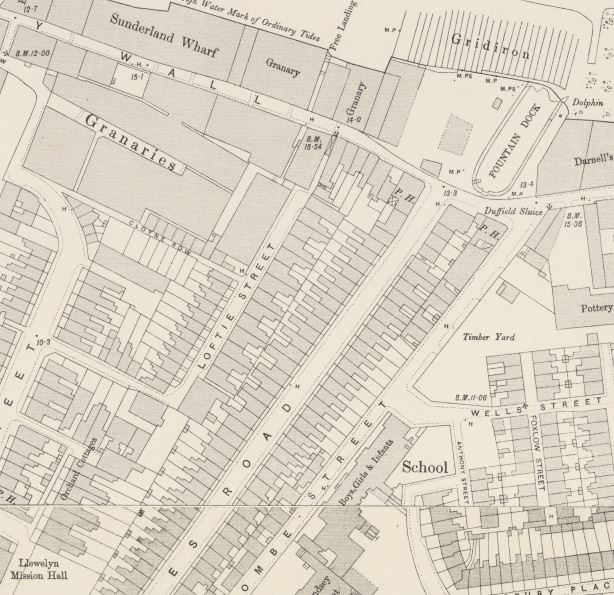

The map below is an extract from the 1951 edition of the Ordnance Survey map for the same area as in the photo.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

The river and “mud and shingle” of the foreshore runs along the top of the map.

Bankside Power Station is the large block towards the left of the map running from top to bottom. The words “overhead conveyor” on the map between power station and river refer to the conveyor partly visible in my father’s photo.

Bankside runs along the river’s edge from left to right.

To the right of centre of the photo there is a street running from Bankside down to the bottom of the map – this is Emerson Street. Look where Emerson Street meets Bankside, then just above, to the left, there is a small cut into the embankment, and the symbol of some stairs reaching down to the river.

These are the same stairs as seen in my father’s photo – Emerson Stairs, leading from the junction of Emerson Street and Bankside, down into the river.

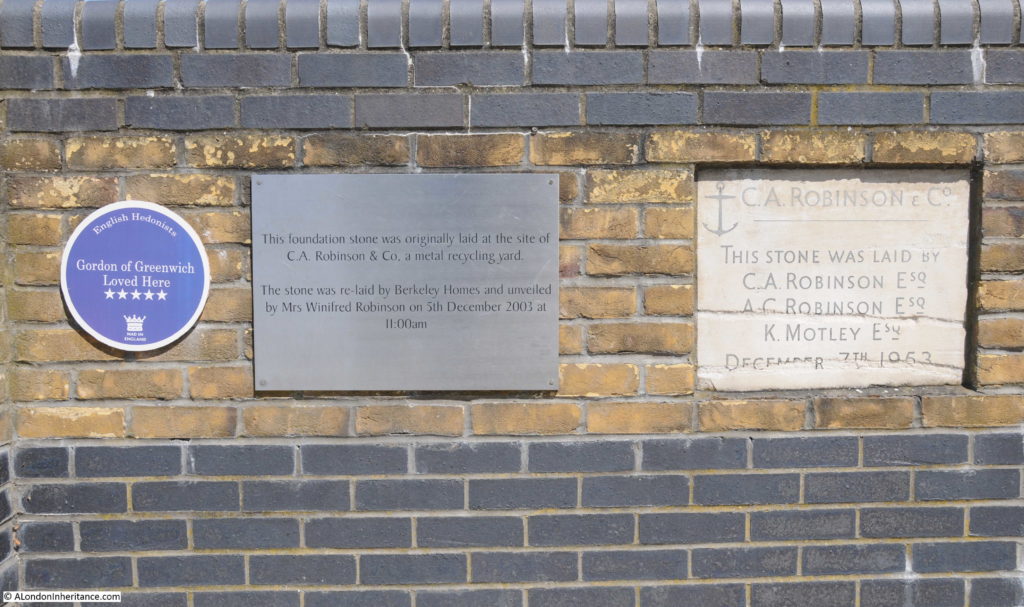

The 1950 edition of the Survey of London – Volume XXII Bankside – provides a source for the name Emerson Street and the associated stairs:

“During the reign of Elizabeth, part of Axe Yard was the property of the Emerson family, William Emerson, died in 1575. His monument in Southwark Cathedral has the succinct epitaph ‘he lived and died an honest man’. His son, Thomas (died 1595) founded one of the parish charities and gave his name to Emerson Street.”

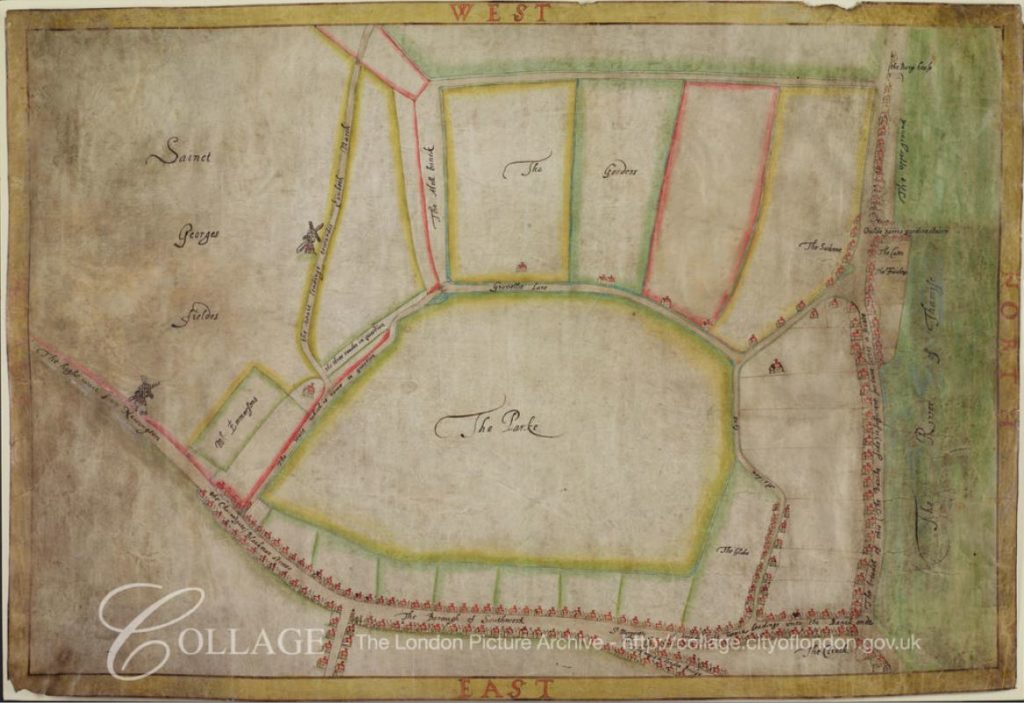

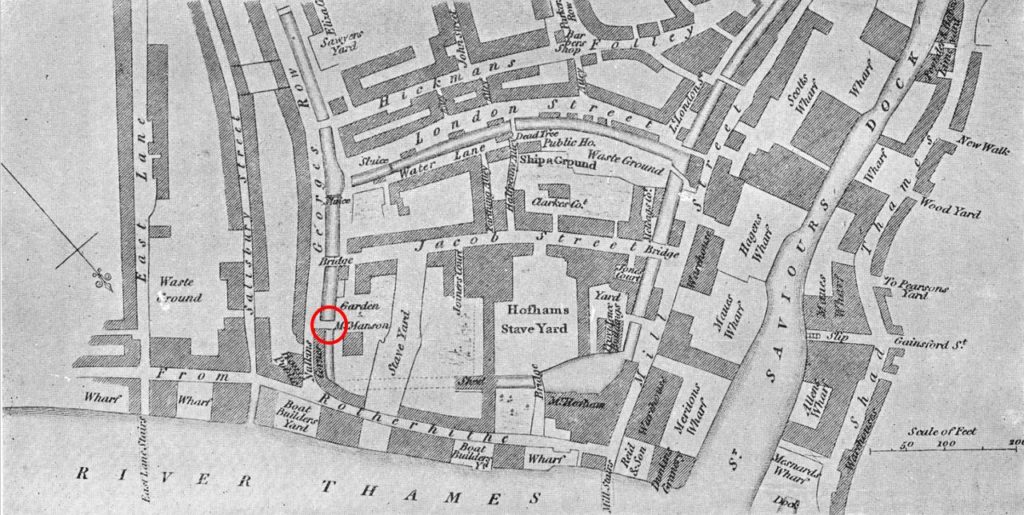

There is a plan of Bankside, dating from 1618, drawn to support a lawsuit over access to Bankside, and in the left of this plan there is a rectangular plot of land labelled ‘Mr Emmerson’s’. The River Thames in the plan is on the right, with Bankside running from top to bottom of the map alongside the river.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: COL_CCS_PL_01_205_26

There is though a bit of a mystery concerning the location and name of the stairs.

I could not find too many mentions of Emerson Stairs. The following newspaper report (London Evening Standard, 6th August 1880) is typical of the few references I could find, where the stairs are used as a reference point on the river:

CORONERS’ INQUESTS – Mr W. Carter, Coroner for the eastern Division of Surrey, held an inquest at the Woolpack, Gravel-lane, yesterday, on the body of John Thomas Glue, 16 years of age. who was drowned in the Thames on Friday last while bathing off Old Barge House Stairs, Upper ground-street, Blackfriars. Thomas Style, who accompanied the deceased for the purpose of bathing, said the deceased swam out some ten or eleven yards, and suddenly called out that he had the cramp, and cried for help. he tried to turn, but was carried down by the rapidity of the current, and sunk under a barge that was moored close at hand. There were a number of others in the water, but at too great a distance to render him any help. Witness packed up the deceased’s clothing and handed them to the police – G.J. Jeffery, Fireman No. 91. picked up the body between Southwark bridge and Emerson Stairs and gave it into the charge of Police-constable 103 M. who had it conveyed to the mortuary.”

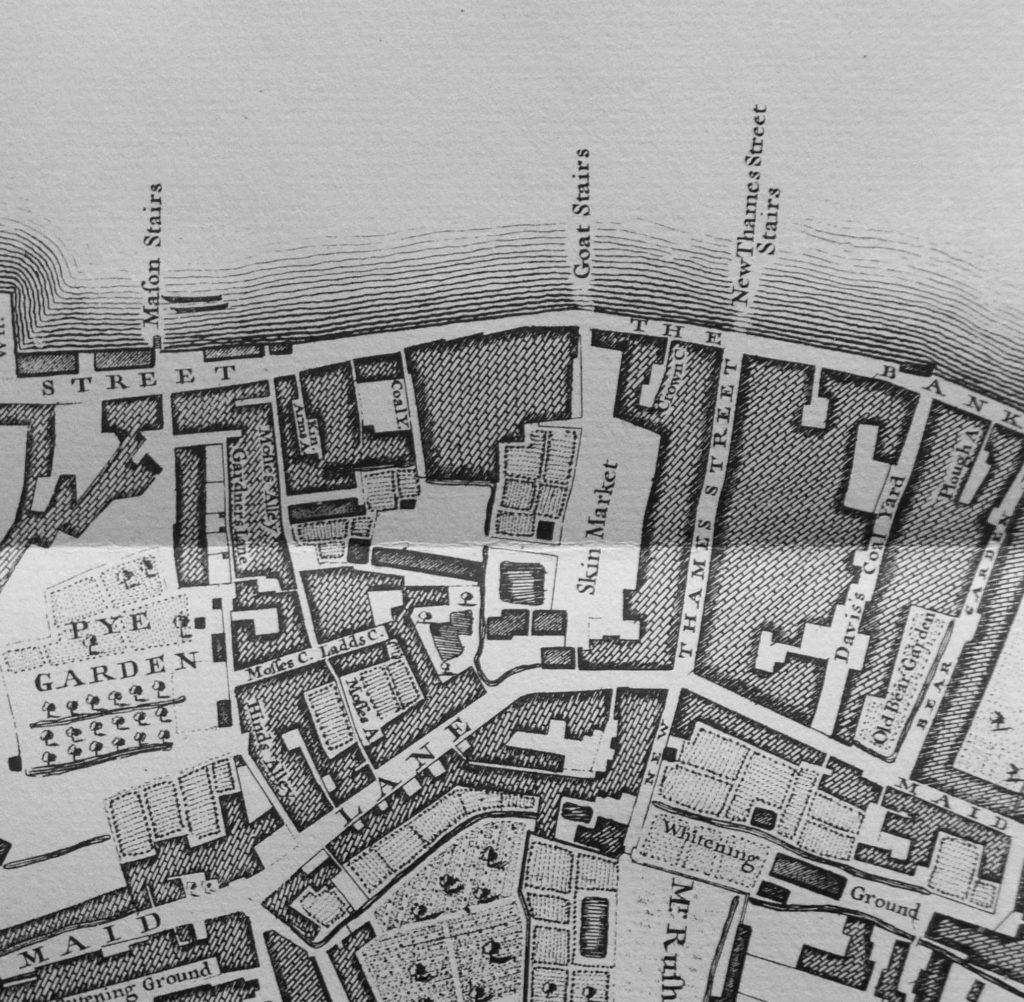

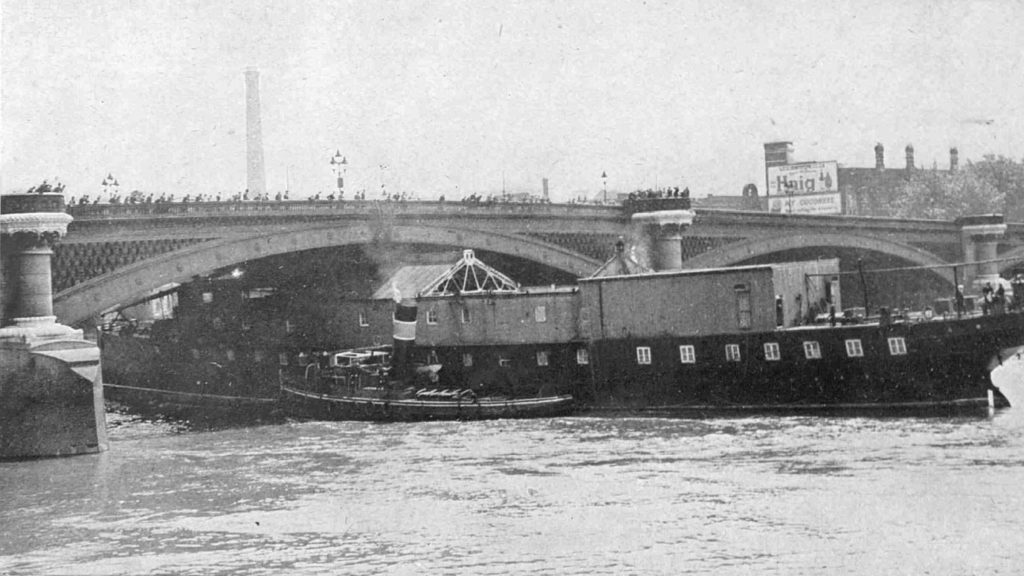

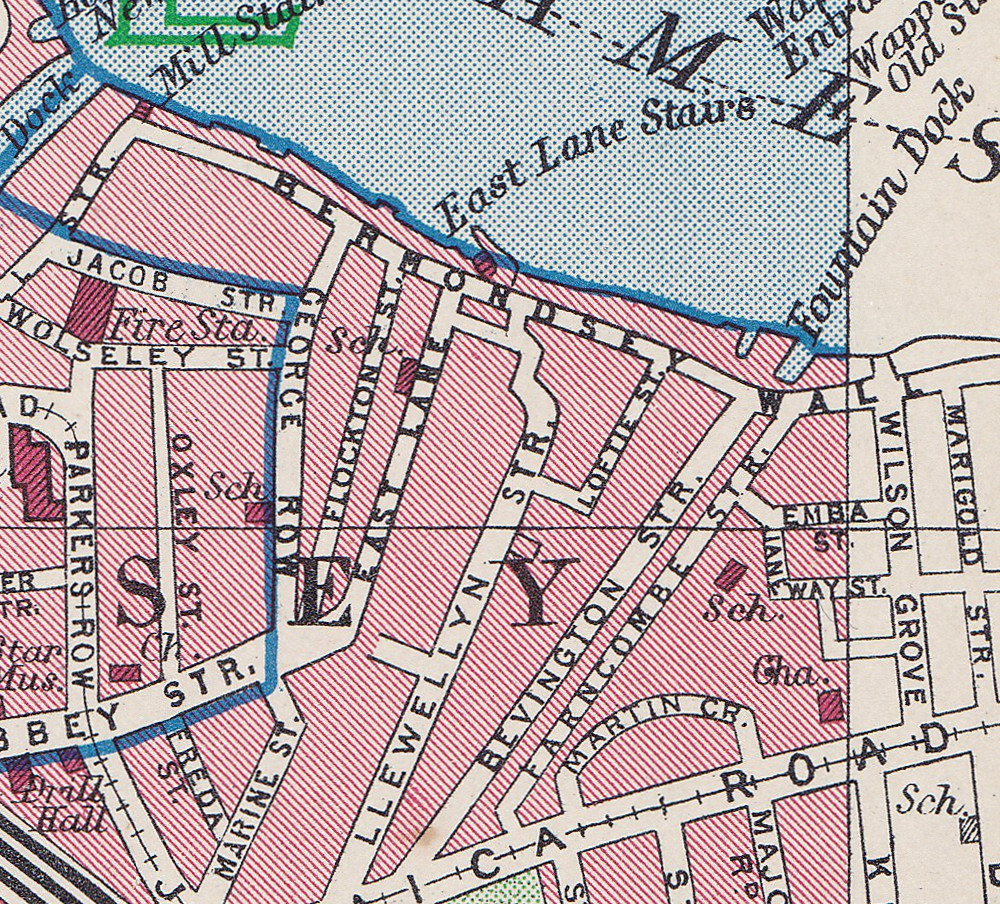

Stairs leading down to the River Thames have often been in existence for many centuries, so I checked John Rocque’s map of London from 1746. The map extract below shows roughly the same area, but where Emerson Street was located in the 1951 map, there is a street named Thames Street, with a set of stairs at the end of the street called New Thames Street Stairs.

So was this the original name of the street and stairs?

Emerson Street is the name on the 1895 Ordnance Survey map, however earlier than this, there seems to be a dual use of Emerson and Thames Street back to around 1880, with Thames Street being the name used prior to 1880.

An example of the use of Thames Street is from multiple reports on the 13th December 1845 about a very high tide that caused significant damage all along the Thames:

“LAMENTABLE EFFECTS OF THE HIGH TIDE – The publicans in Thames Street, Bankside, and so on to Westminster and Lambeth, had their cellars filled with water. The Commercial Road, Lambeth and Belvidere-road, were all under water, and in the later road the cellars were filled. Searle’s the boat builders premises, the glass house and wharfs between the latter place and Bishop’s-walk were flooded to a depth of several feet. the road to Lambeth Church was impassable. The tide rushed under the gates of the Archbishop’s Palace, filling the gardens and approaches to the house. In Fore-street, High-street, and Ferry street, the licences victuallers and other have sustained great losses, and the landlady of the Duke’s Head, in Fore-street estimates her loss at £200.”

So, my assumption was that during the 1880s, Thames Street was renamed to Emerson Street, with the stairs also taking on the Emerson name.

I then checked the Layers of London website to overlay the Rocque map on the 1950s Ordnance Survey map to confirm, but here it got confusing.

The overlay of these maps appeared to show that Thames Street and New Thames Street Stairs were a short distance to the west of Emerson Street and Stairs. Indeed, the road at the south of Emerson Street, Park Street also looks to be in a slightly different position when comparing the two maps.

Returning to a slightly wider view of the Ordnance Survey map, and comparing with the Rocque map, the position of Emerson Street and Thames Street appear the same. The alignment of Maid Lane, and its future name of Park Street look roughly the same, leading down to what would become the junction with Sumner Street.

Credit: ‘Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland’

And comparing with the street layout of today, this looks the same, however Emerson Street has undergone yet another name change. The section north from Park Street to Bankside is now called New Globe Walk – a relatively recent name change to go with the build of the Globe Theatre on what was Emerson Wharf (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors).

So I suspect that Thames Street and New Thames Street Stairs changed name to Emerson Street and Emerson Stairs at some point in the 1880s. They were the same streets, and the mapping between the Rocque and Ordnance Survey maps on the Layers of London site is slightly out at this point – which is only to be expected given the lack of precise mapping and recording techniques available to Roqcue in the mid 18th century.

The name Emerson Street is retained on the southern section from Park Street to Sumner Street, so a reference to the 16th century Thomas Emerson can still be found in Bankside.

There is a report of an inspection by the St. Saviours Board of Works into the condition of Thames stairs and landing places in November 1866. This report includes Thames Street Stairs, but also lists all those within their responsibility and provides names of some that remain, and some lost:

“The committee had made an inspection of the following water-side passages or ways in the district through which the board possessed a right of way – viz: Primrose-alley, St. Mary Overie’s Dock, St. Mary Overie’s Stairs, Horse-shoe-alley Stairs, Rose-alley, Bankside, Thames-street Stairs, Mason’s Stairs, Love-lane Stairs, Clark’s-alley, Rennie’s gateway, Marygold Passage and Stairs, Bull-alley Passage and Barge-house Alley and Stairs, in most of which obstructions, nuisances, &c, existed, which required to be attended to. Referred back to the committee.”

The list of names gives an indication of the number of stairs and alleys there were leading to the river, and there are some intriguing names, Obstructions and nuisances also lets the imagination roam over what river side life was like, and the activities that went on at these stairs and passages, on the border between land and river.

The references I have found name the stairs Thames Street Stairs, rather than New Thames Street Stairs as referenced in Rocque’s map. The use of the word “New” in 1746 is either an error, or implies these stairs replaced a previous set of stairs with the same name – one for my endless list of things I still want to research.

So what does the area look like today?

The following photo is from Bankside, looking down New Globe Walk / Emerson Street / Thames Street.

Part of the street now has restricted vehicle access and the Globe Theatre now occupies the space on the western corner.

This is the view looking up towards the river at the junction of New Globe Walk / Emerson Street / Thames Street with Bankside. The stairs would have been roughly in front of where the red life buoy can be seen.

The stairs were located where Bankside Pier now stands. The pier is directly opposite New Globe Walk and provides access to the passenger ferries that run along the Thames, so although the stairs have disappeared, the same location continues to be used as a means of accessing craft on the river.

Although Emerson Stairs have gone, there are still stairs down to the river at Bankside. A short distance to the west from Bankside Pier are these stairs leading down to the foreshore.

These are new stairs, built as part of the re-development of Bankside, however there is perhaps a historical reference for these stairs.

Looking back at the Rocque map, and just to the west of New Thames Street Stairs are Goat Stairs. Align these with Maid Lane in 1746 and Park Street in 2019 and they are in a similar position (although perhaps a bit too far to the west, depending on the accuracy of the 1746 map).

Goat Stairs are not found on the Ordnance Survey maps, so these were lost much earlier, however the new stairs are a good reminder of the old stairs that once connected Bankside with the river.

From the foreshore by the stairs we can look back at Bankside Pier, the location of Emerson / Thames Street Stairs.

Invisible from the walkway along the river, but visible down on the foreshore, the word BANKSIDE calls out to those on the river and on the opposite shore.

The history of the stairs that line the River Thames is fascinating. I have written about a number before including Alderman Stairs, Old Swan Stairs and Horselydown Old Stairs.

I can now add Emerson Stairs / Thames Street Stairs to the list, and I have many more to go.

Stairs are simple structures, but it is their role as a reference point on the river, and a route crossing the boundary between land and river that is so fascinating.

There are numerous stories about events at these stairs, a couple of which I have already mentioned. Many stories highlight a tragedy and the challenges of life in London – such is the nature of news reporting. One particular report from the 29th May 1842 demonstrated the impact on women of the daily struggle to support a family, and how this came to a tragic conclusion at Thames Street Stairs:

” SUICIDE – On Friday a suicide was committed at the Thames Street Stairs, Bankside, by a respectable married woman, named Firmin, the wife of a lighterman, residing in the Commercial road, Lambeth. Her husband, having occasion to go to work about three o’clock in the morning, left the deceased in bed, and soon afterwards she got up, and having dressed herself, went to the above stairs, and getting on to some barges alongside threw herself into the river. A watchman on the opposite side immediately gave an alarm, and the body was got out of the water, but life was quite extinct. The deceased had been married about twenty two years, and was the mother of eighteen children. Not the slightest reason can be assigned for the committal of the rash act.”

I suspect the reason for the so called ‘rash act’, may have been the challenge of providing for and supporting the family mentioned in the second to last sentence – the stress of supporting a family with eighteen children on a lighterman’s wages must have been enormous.

One final point before finishing this post, the 1950’s Ordnance Survey map shows a number of circles marked “hoppers” in the space between the Emerson Wharf building and Emerson Street.

These are not visible in my father’s photo which was taken in 1947, but they were installed a couple of years later as shown in the photo below taken by my father in 1949 from the north bank of the river, which also provides a good view of the river facing side of Emerson Wharf (the hoppers are slightly left of centre).

I suspect that when the hoppers were added, there was an expectation that industrial life would continue as it had done, however changes in river usage, and the closure of industry along the river in the decades following my father’s photo would end with the scene we see today with the Globe Theatre occupying Emerson Wharf, and the Bankside Pier providing access to the river, in place of Emerson Stairs.