When I started this post, it was going to be a brief mid-week post about a bowling green in the King Edward VII Memorial Park, Shadwell, East London, sandwiched between the River Thames and the very busy road that is now called The Highway. Instead, it has turned into a much longer post as I discovered more about the area, and what was here before.

One of my favourite walks is from the Isle of Dogs to central London. There are so many different routes, all through interesting and historic places. A couple of routes are along the Thames path, or along the Highway. Both routes take you past the King Edward VII Memorial Park and it was here that I found a scene, more expected within a leafy suburb than in Shadwell.

Last November I walked through the park and found the rather impressive bowling green. I am not sure if it is still in use, the grass, although still very flat and green, does not look perfect.

The pavilion at the far end:

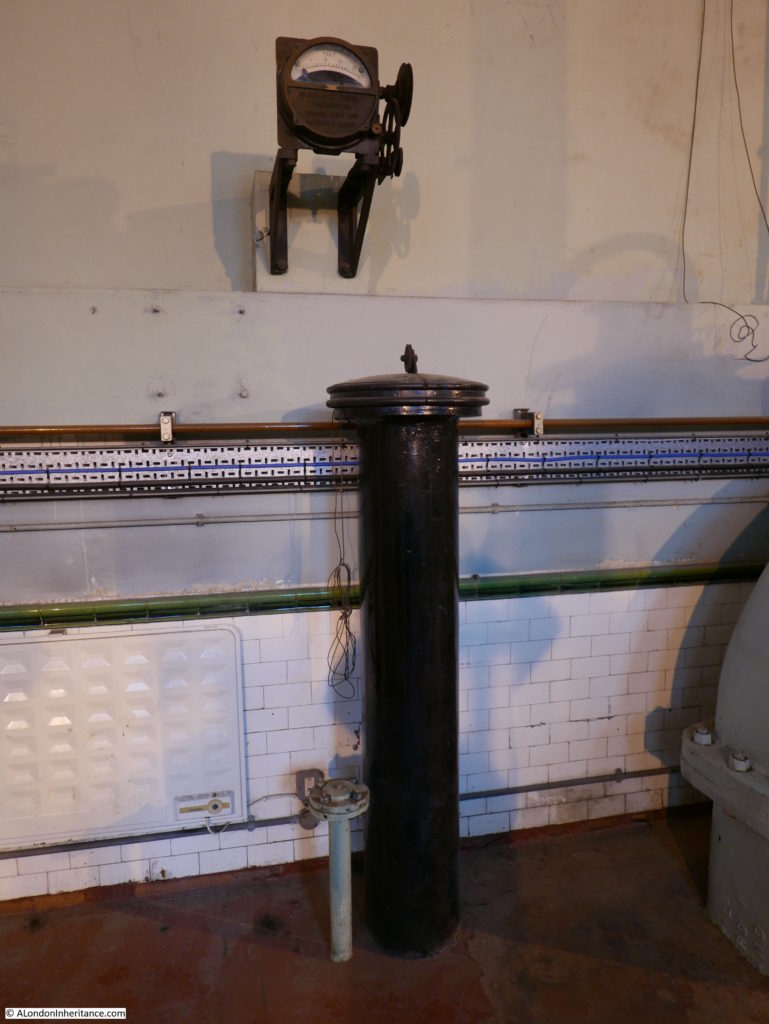

It appears to be used as a store room:

The site was used by the Shadwell Bowls Club. The last reference I can find to the club is in the Tower Hamlets King Edward Memorial Park Management Plan January 2008, when the club was listed as active. In the 2016 Masterplan for the park, the site of the bowling green is shown as tennis courts, so the green may not be here for much longer.

Looking back over the green, with the well-kept hedge running around the edge and the wooden boarding around the side of the green, it is not hard to imagine a game of bowls in this most unlikely of places:

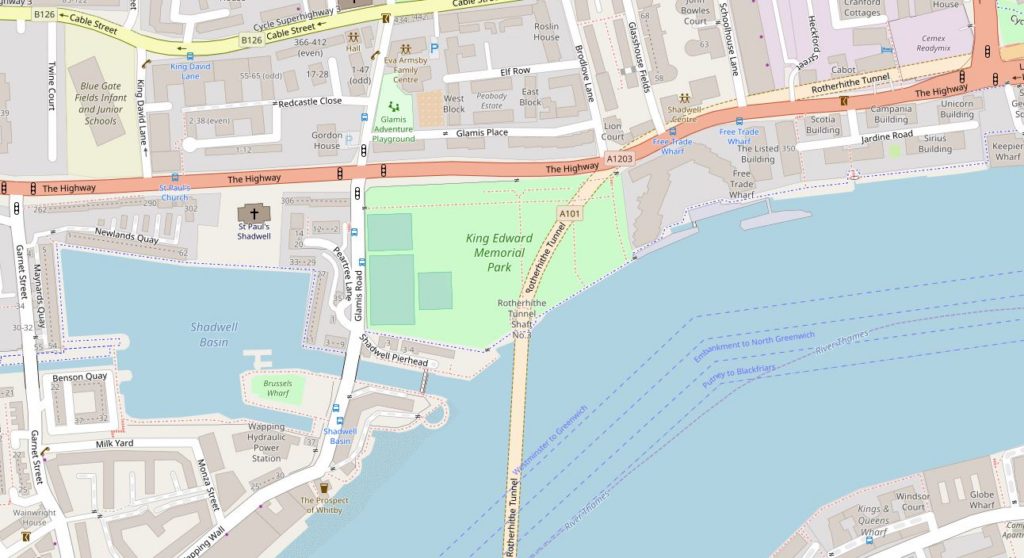

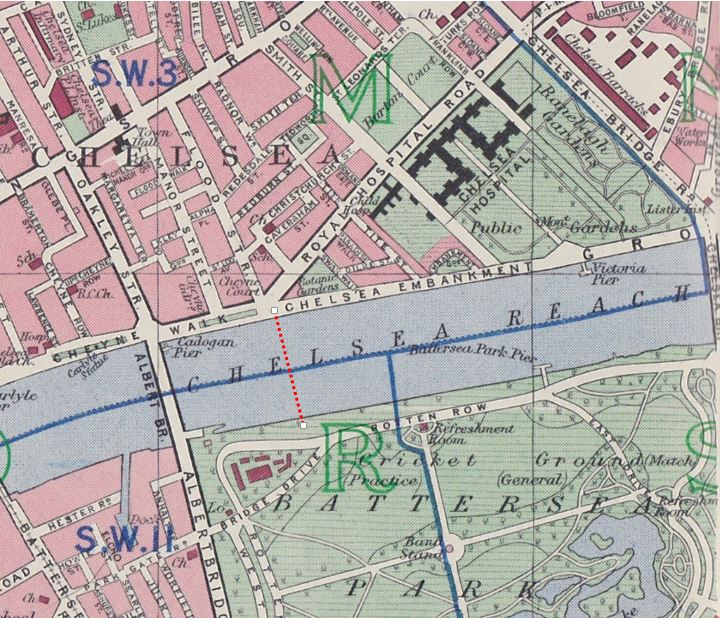

The following map shows the location of the King Edward VII Memorial Park. Just to the north east of the Shadwell Basin and between the Highway and the River Thames. The map shows a road crossing the park, however this is the Rotherhithe Tunnel, so instead of running across the surface of the park, it is some 50 feet below.

After the death of King Edward VII in May 1910, a memorial committee was formed to identify suitable memorials to the king. One of the proposals put forward was the creation of a public park in east London, on land partly owned by the City Corporation.

Terms were agreed for the transfer of the land to the council, funding was put in place and on the 23rd December 1911, the East London Observer recorded that the plan for the King Edward VII Memorial Park was approved by the City Corporation, the London County Council and the Memorial Committee, and that “unless anything unforeseen occurs, it will become an accomplished fact in a very short time”.

Unfortunately, there was an unforeseen event, the First War which delayed completion of the park until 1922 when it was finally opened by King George V on the 26th June.

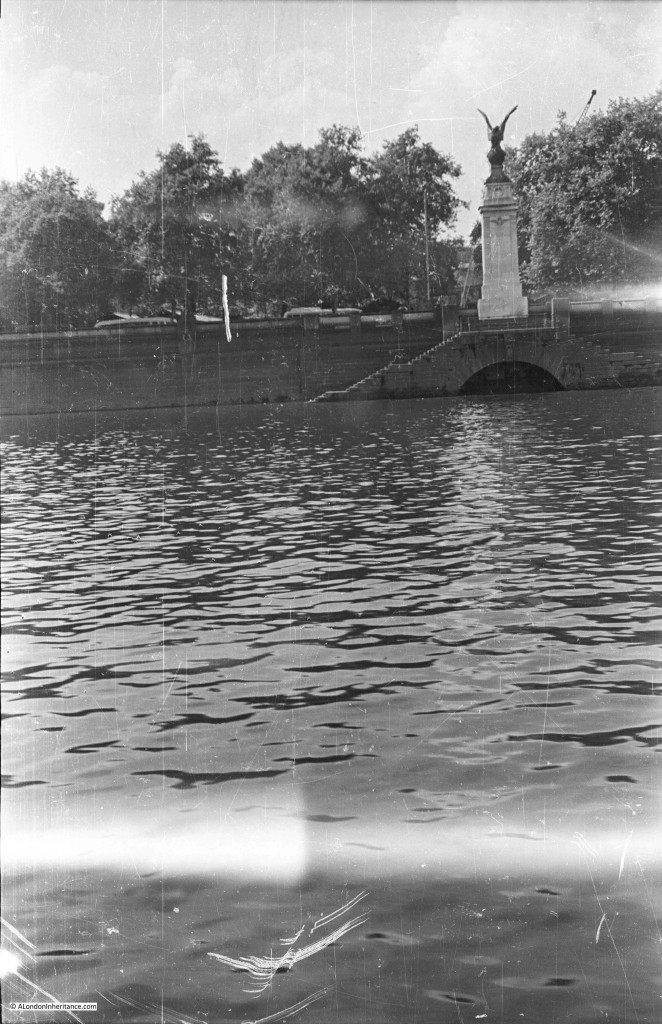

The park is a good example of Edwardian design. A terrace runs the full length of the park along the Highway. In the centre of the terrace is a monument to King Edward VII, with steps leading down to the large open area which runs down to the river walkway.

There were clear benefits of the park to the residents of east London at the time of planning. It would provide the only large area of public riverside access between Tower Bridge and the Isle of Dogs and it was the only public park in Stepney.

Over the years, the park has included glasshouses, a bandstand and children’s playground.

The following photo shows the pathway through the centre of the park from the river up to the monument on the terrace. There was a bronze medallion depicting King Edward VII on the centre of the monument, however this was apparently stolen some years ago.

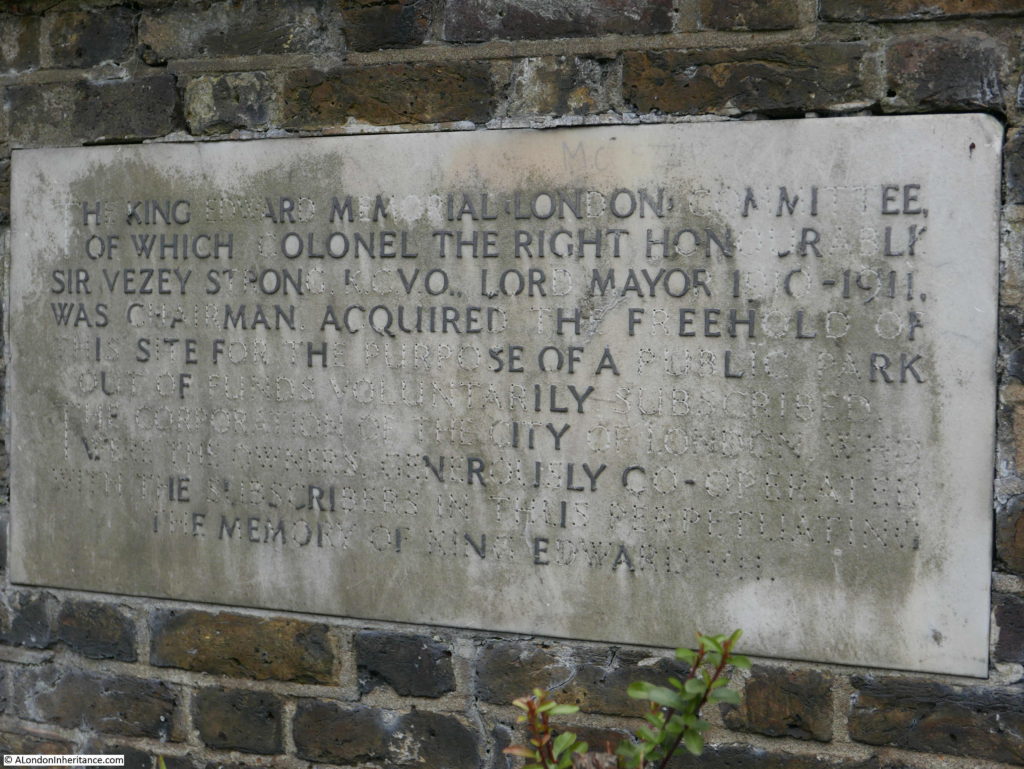

On the wall at the rear of the monument, between the terrace and the Highway is the following plaque:

It reads:

“The King Edward, Memorial London Committee, of which Colonel the Right Honourable Sir Vezey Strong KCVO, Lord Mayor 1910 – 1911 was chairman acquired the freehold of this site for the purpose of a public park out of funds voluntarily subscribed. The Corporation of the City of London who were the owners generously cooperated with the subscribers in thus perpetuating the memory of King Edward VII”

The view along the terrace to the east:

The view along the terrace to the west. The church steeple is that of St. Paul’s Shadwell.

The view down from behind the monument towards the river. When the park was opened, the view of the river was open. It must have been a fantastic place to watch the shipping on the river.

At the river end of the central walkway is one of the four shafts down to the Rotherhithe tunnel. Originally this provided pedestrian access to the tunnel as well as ventilation, so it was possible to walk along the river, down the shaft and under the Thames and emerge on the opposite side of the river.

There is some lovely London County Council design detail in the building surrounding the shaft. The open windows have metal grills and within the centre of each grill are the letters LCC.

It was possible to walk along the river without entering the park, however this is one of the construction sites for the Thames Tideway project to build a new sewer and provide the capacity to take the overflow which currently runs into the Thames. The site at the King Edward VII Memorial Park will be used to intercept the existing local combined sewer overflow, and when complete will provide an extension to the park out into the river, which will cover the construction site.

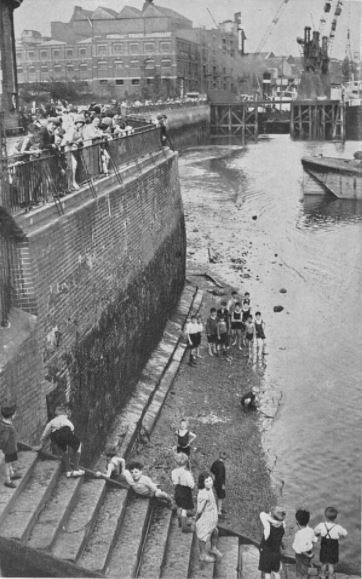

There are many accounts of the popularity of the park after it opened. Newspaper reports call the park a “green lung” in east London and during the summer the park was full with children of all ages.

During the hot August of 1933, access to the river from the park was very popular:

The following photo dated 1946 from Britain from Above shows the park at lower left. Note the round access shaft to the Rotherhithe tunnel. In the photo the shaft has no roof. The original glass roof was removed in the 1930s to improve ventilation. The current roof was installed in 2007.

The King Edward VII Memorial Park is interesting enough, however I wanted to find out more about the site before the park was built.

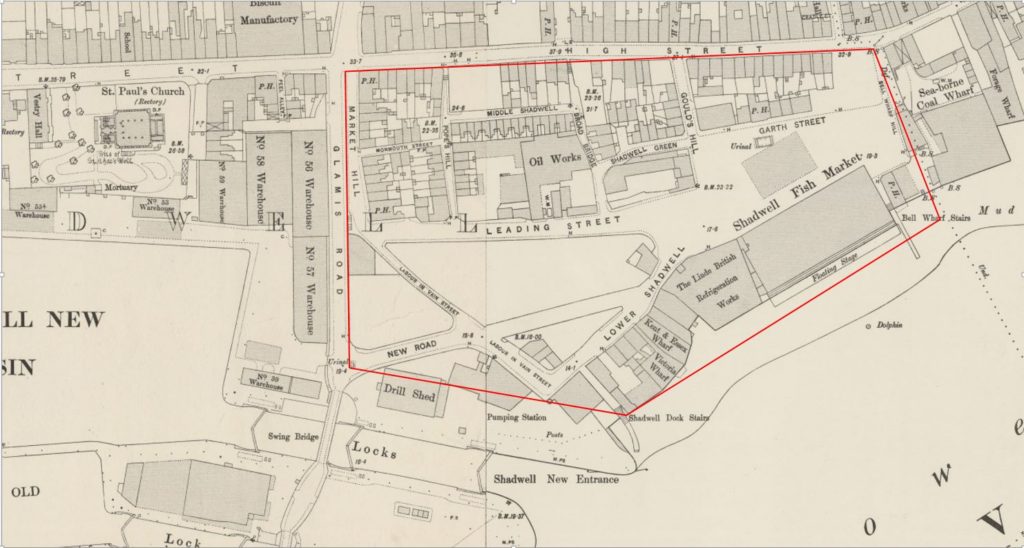

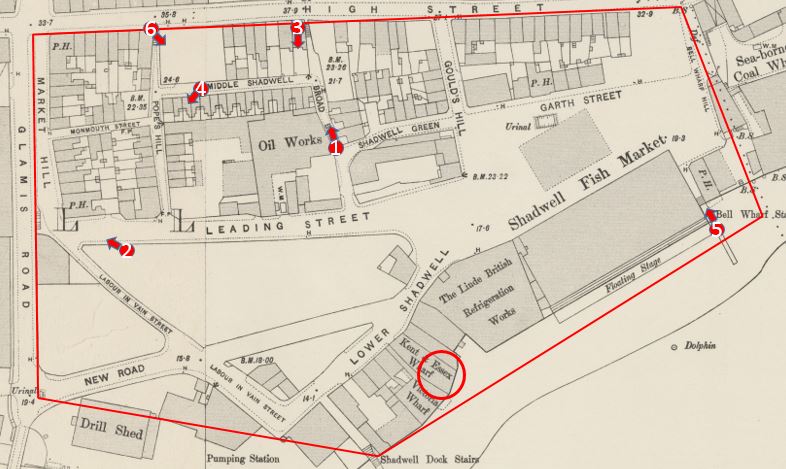

The 1895 Ordnance Survey map provides a detailed view of the site, and I have marked the boundaries of the park by the red lines to show exactly the area covered.

There were some fascinating features. In the lower right section of the park, was the Shadwell Fish Market – I will come onto this location later in the post along with the adjacent refrigeration works.

Above the fish market is Garth Street. The public house (PH) shown in Garth Street was the King of Prussia. I cannot find too much about the pub apart from the usual newspaper reports of auctions and inquests being held at the pub, however there were a number of reports of a disastrous fire which destroyed the pub on the 14th November 1890. Two small children, Agnes Pass aged seven and Elizabeth Pass aged two died in the fire which started in the bar and spread rapidly through the pub. The location of the pub today is just in front of the eastern terrace, about half way along.

Interesting that in the map, there are urinals shown directly in front of the pub – a very convenient location.

To the left of centre of the park can be found a large building identified as an Oil Works. The left hand part of this building is covering part of the bowling green.

One of the streets in the lower right is called Labour In Vain Street, an interesting street name which could also be found in a couple of other London locations.

In 1895 the Rotherhithe Tunnel had not yet been built (it was constructed between the years 1904 and 1908), so the access shaft does not feature in the map. It would be built over the riverside half of the Kent and Essex Wharf building.

The main feature in the map is the Shadwell Fish Market. This was a short-lived alternative to Billingsgate Fish Market.

In the 19th century there were a number of proposals to relocate Billingsgate Fish Market. It had a relatively short frontage to the river and was located in a very crowded part of London with limited space to expand.

Shadwell was put forward as an alternative location. In September 1868, the Tower Hamlets and East End Local Advertiser reported on the petition put forward by the Board of Works for the Limehouse District to campaign for the Shadwell Fish Market. The petition put forward a number of reasons why Shadwell was the right place to relocate Billingsgate:

- That it is the nearest site to the city of London, abutting upon the river for the purposes of a fish market;

- That an area of land upwards of seven acres in extent could be obtained upon very reasonable terms;

- That by means of a short branch of railway to be constructed, communications can be made with every railway from London north and south of the Thames.

- That by means of the Commercial-road and Back-road (recently renamed Cable-street) and other thoroughfares, convenient approaches exist to the proposed site of the market from all parts of London;

- That in consequence of the bend in the river at Shadwell, which forms a bay, ample accommodation exists for the mooring of vessels engaged in the fishing trade, without interfering with the navigation of the river;

- That easy communication can be made with the south side of the Thames by means of a steam ferry, which would also be available for ordinary traffic, and which to a large extent would prevent the overcrowding of the traffic in the City, especially over London-bridge;

- That there is no other site on the River Thames which presents so many advantages as that proposed at Shadwell;

- That the establishment of a fish market at Shadwell would be a great boon to the whole of the East-end of London;

- That should Billingsgate-market be removed, the fish salesmen are in favour of the market being established at Shadwell.

A very compelling case, however there were a number of vested interests in the continuation of the fish market at Billingsgate and no progress was made with approval for a fish market at Shadwell.

However the issue never went away, and in 1884 a company was formed to “give effect to the London Riverside Fish Market Act of 1882”. The company had “on its Board of Directors, three of the best known and most popular men in the East of London – men who taken a considerable interest in the welfare of the people of the district, and have embarked in this enterprise, feeling assured not only of its value to the public, but with confidence that it will prove a commercial success.”

The Directors of the company were Mr. E.R. Cook, Mr. Spencer Charrington, Mr. T.H. Bryant, Mr. E. Hart and Mr. Robert Hewett.

Robert Hewett was a member of the Hewett family who owned the Short Blue Fishing Fleet and was keen to leave Billingsgate due to the lack of space. He would transfer his fleet of ships from Billingsgate to Shadwell.

Work progressed on the construction of the market and at a ceremony to mark the pile driving, the local MP, Mr Samuel Morley, “confidently communicated to the assembled company the burning desire of the Home Secretary to find remunerative labour for the unemployed in East London. Mr Morley is now in a position to inform that the fish market at Shadwell will afford employment to many working men”.

Shares in the fish market company were advertised in the East London Local Advertiser and “those of the East London public who have not yet practically interested themselves in a scheme which promises so well, the opportunity once more offers itself. Applications for shares should, however, be made without delay.”

The new market opened at the end of 1885 and whilst it appeared to start well, the challenges of attracting business from Billigsgate were already very apparent. The London Daily News reported on the 1st March 1886:

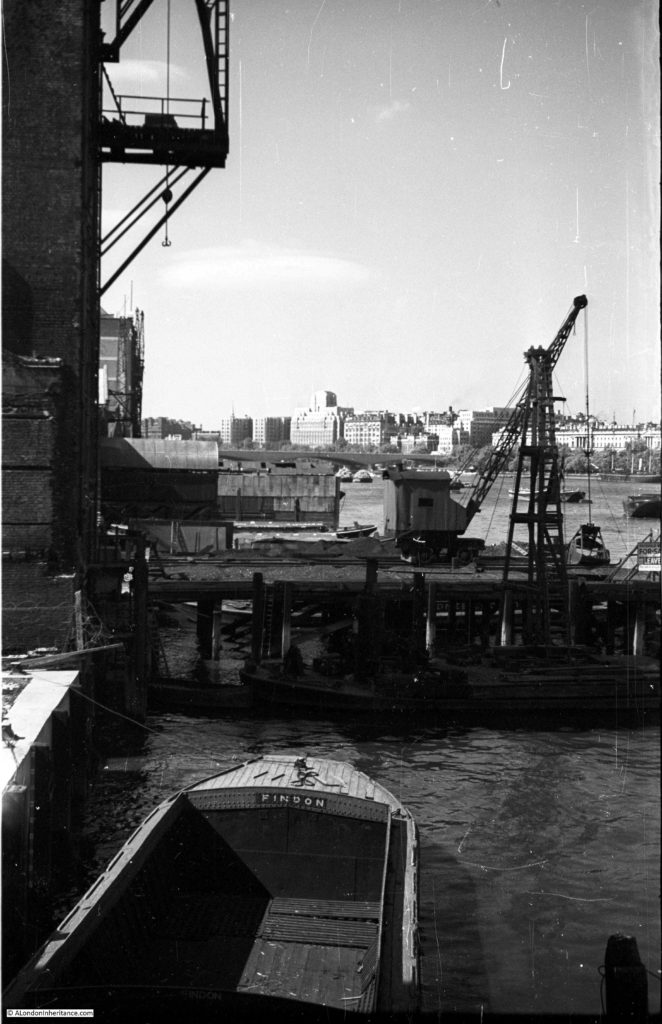

“The new fish market at Shadwell has been going now for about three months, and the fact that a hundred tons of fish can be readily disposed of here every morning indicates pretty satisfactorily that already buyers have begun to find out that the market has at least some advantages over Billingsgate. As regards the supply of this new market, so far as it goes it cannot very well be better. Messrs. Hewett and Co., who are at present practically the only smack owners having to do with it, have 150 vessels out in the North Sea, and a service of steamers plying to and fro between the fleet and the market.”

Interesting how fish were brought in from the north sea fishing boats by a fleet of steamers – a rather efficient method for bringing fish quickly ashore and keeping the fishing boats fishing.

The article indicates the problem that would result in the eventual failure of the Shadwell Fish Market, It was only the Hewett Company that relocated from Billingsgate. None of the other traders could be convinced to move, and there was an extension of the Billingsgate Market which addressed many of the issues with lack of space.

The market continued in business, but Billingsgate continued as the main fish market for London. The Shadwell market was sold to the City of London Corporation in 1904, and in less than a decade later the market closed in preparation for the construction of the King Edward VII Memorial Park.

In total the Shadwell Fish Market had lasted for less than twenty years.

The building adjacent to the fish market was the Linde British Refrigeration Works. A company formed to use the refrigeration technology developed by the German academic Carl von Linde. The Shadwell works were capable of producing 150 tons of ice a day.

Before taking a look at the area just before demolition ready for the new park, we can look back a bit earlier to Rocque’s map of 1746.

The road labelled Upper Shadwell is the Highway. Just below the two LLs of Shadwell can be seen Dean Street, this was the original Garth Street. Shadwell Dock Stairs can be seen under the W of Lower Shadwell and to the right is Coal Stairs which was lost with the development of the fish market.

To the right of Coal Stairs is Lower Stone Stairs. By 1895 these had changed name to Bell Wharf Stairs.

The map illustrates how in 1746 the area between the Highway and the river was already densely populated.

To see if there are any photos of the area, I check on the London Metropolitan Archives, Collage site and found a number of photos of the streets prior to, and during demolition. These are shown below and I have marked the location from where the photos were taken on the 1895 map.

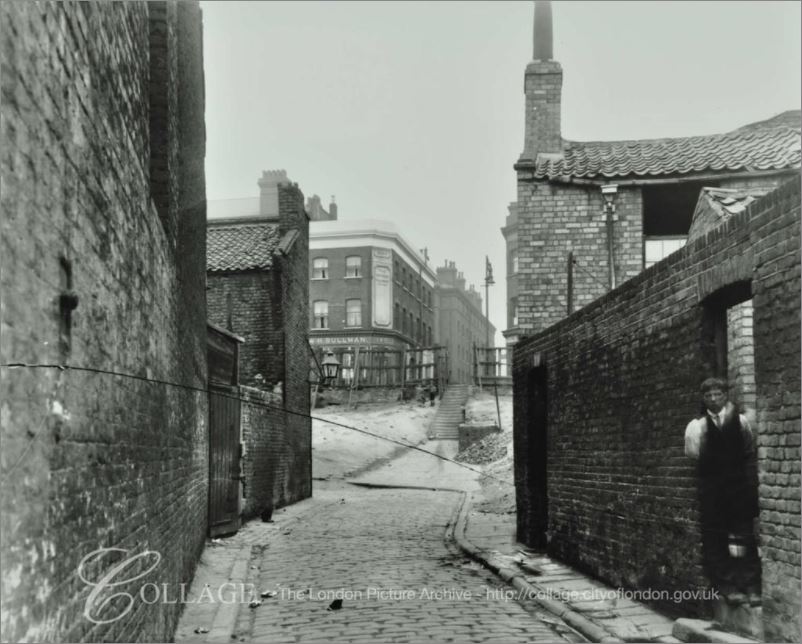

Site 1: Looking up towards the High Street (the Highway) along Broad Bridge. The building on the left is the Oil Works and residential houses are on the right. Note the steps leading up to the High Street, confirming that the high difference between the Highway and the main body of the park has always been a feature of the area, and is visible today with the terrace and steps leading down to the main body of the park.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_381_A361.

Site 2: This photo was taken to the south of Leading Street and is looking across to the steps leading up to Glamis Road, a road that is still there today. The church of St. Paul’s Shadwell is in the background.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_392_82_1222

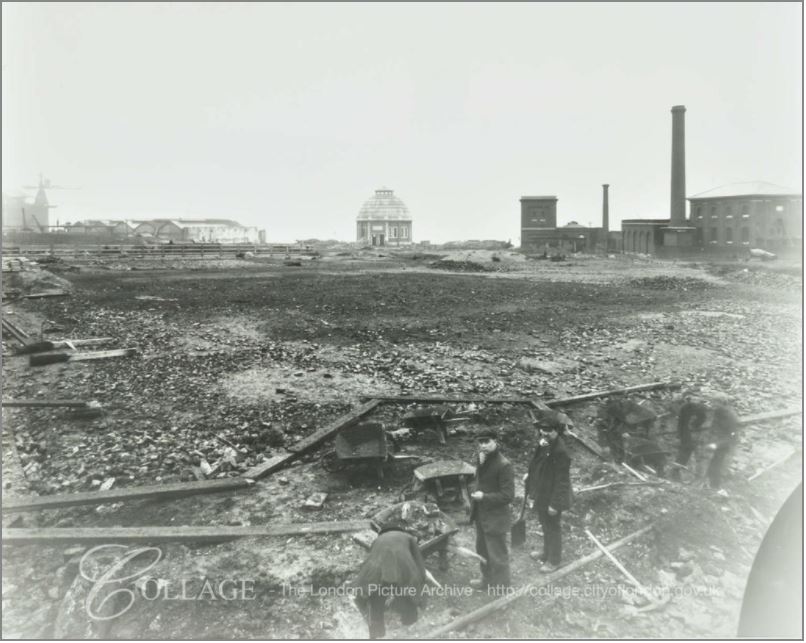

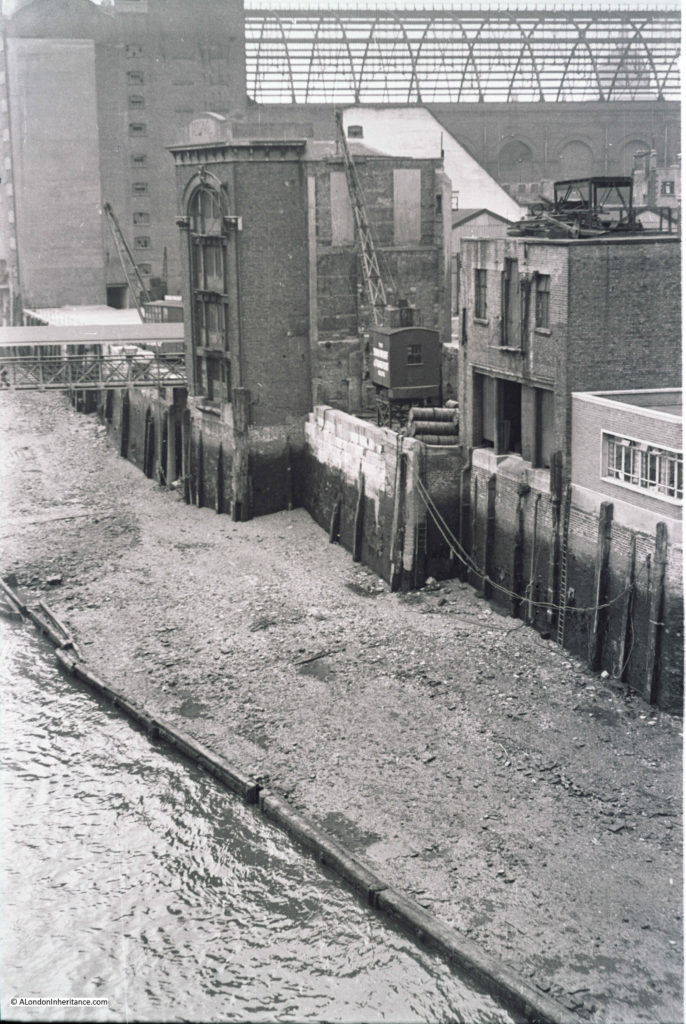

Site 3: This photo was taken from the High Street (Highway) hence the height difference. It is looking down towards the river with the shaft of the Rotherhithe Tunnel one of the few remaining buildings – and the only building still to be found in the area. The remains of the metal framework of the fish market sheds can be seen to the left of the access shaft.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_392_A713

Site 4: This photo was taken in the street Middle Shadwell (the buildings being already demolished) looking down towards a terrace of houses remaining on Pope’s Hill. the buildings in the background are Number 56 and 57 Warehouse of the Shadwell New Basin on the opposite side of Glamis Road.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_396_A495

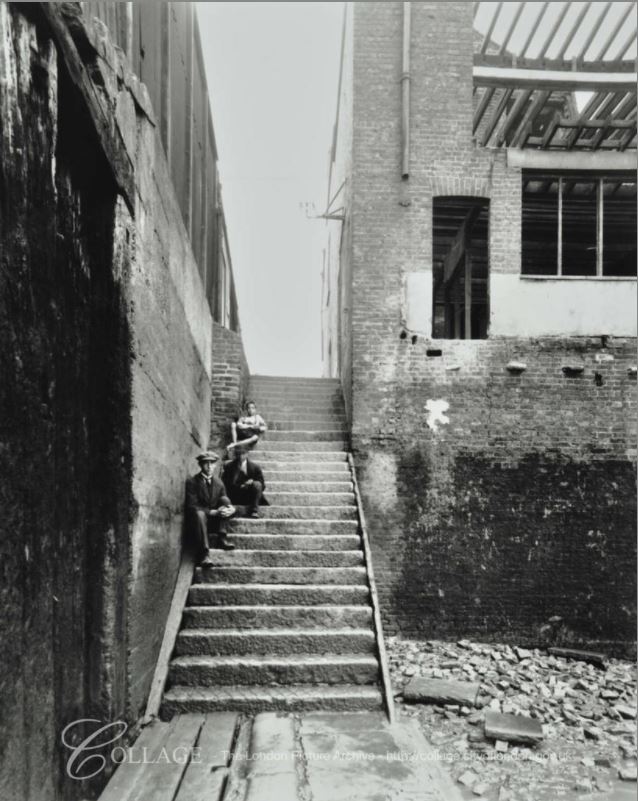

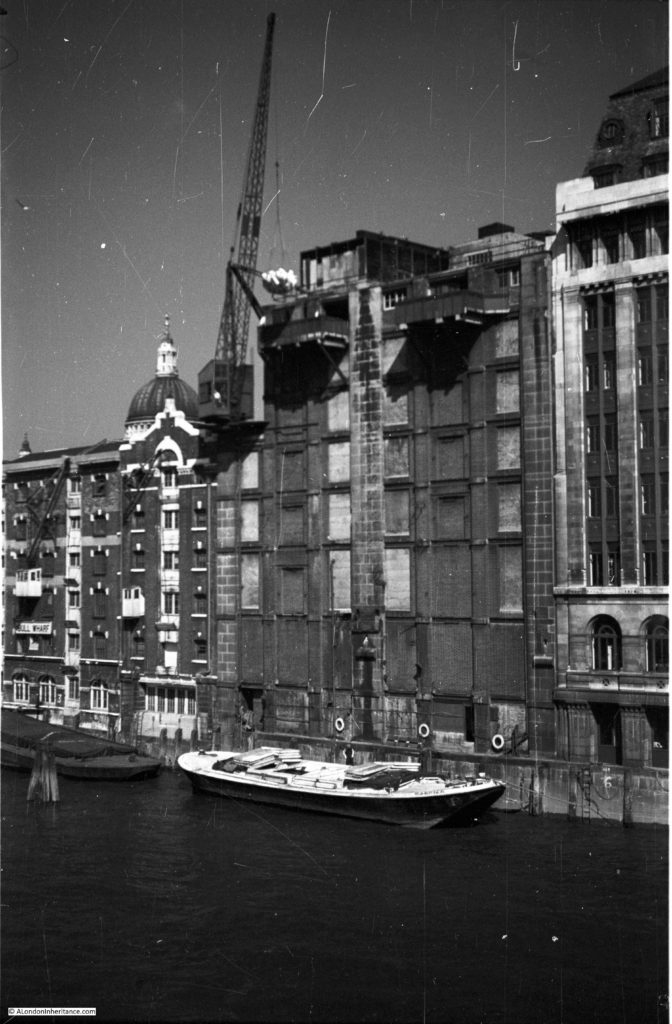

Site 5: This photo is taken looking up Bell Wharf Stairs from the Thames foreshore. The sheds of the Shadwell Fish Market are on the left. The building on the right is the remains of the pub the Coal Meters Arms.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_02_0638_A363

A possible source for the name Coal Meters Arms may be found in the following strange story from John Bull dated the 3rd April 1843:

“Jeremiah John Kelly, the man who entered the lobby of the House of Commons on Friday evening, in a half-mad, half-drunken state, and who was taken into custody by the police, with a carving-knife in his possession, is a person of wayward character and habits., who has given much trouble to the Thames Police Magistrates, and there can be little doubt that he intended to commit an assault on Lord J. Russell, and perpetuate an outrage on that Nobleman. Kelly has made no secret of his intention of attacking Lord John Russell for some time past, and fancies he has some claims on his Lordship for services performed during the last election for the city of London. A few years since Kelly was in business as a licensed victualler, and kept the Coal Meters Arms , in Lower Shadwell, where he also carried on the business of a coal merchant, and an agent for the delivery of colliers in the Pool.”

So perhaps an element of Kelly’s trade was used for the name of the pub.

Site 6: Is at the top of Pope’s Hill where it meets the Highway and is looking back at the remaining terrace houses on the southern side of Middle Shadwell.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_393_A364

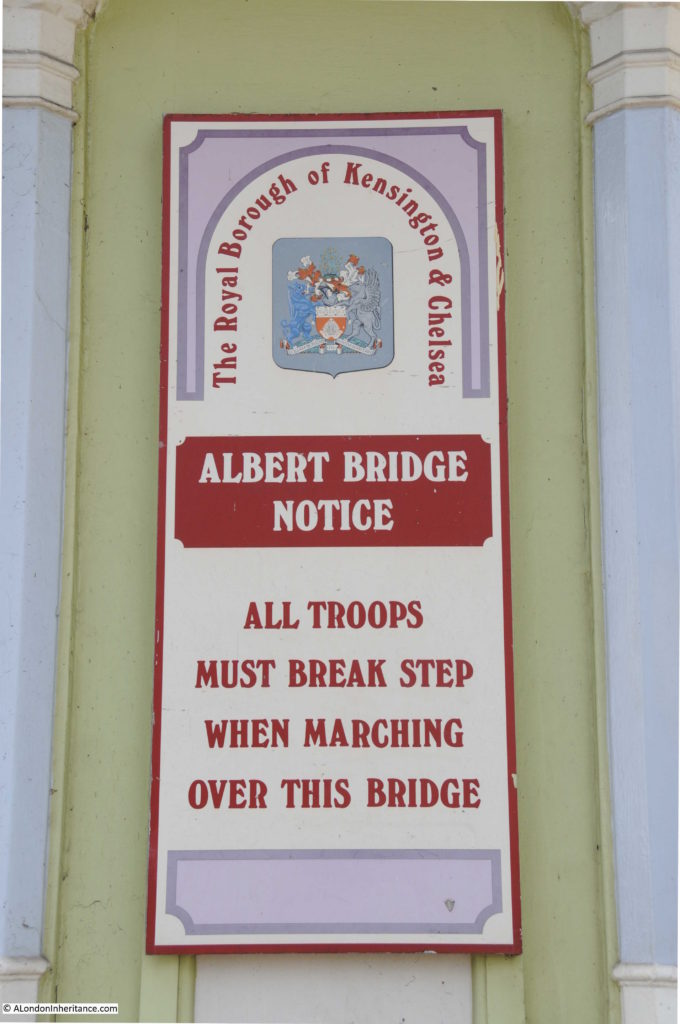

There is one final story to be found in the King Edward VII Memorial Park. Next to the Rotherhithe Tunnel entrance shaft is the following plaque:

The plaque was put in place in the year that the park was opened, and records among others, Sir Hugh Willoughby, a 16th century adventurer and explorer. He died in 1554 whilst trying to find a route around the north of Norway to trade with Russia.

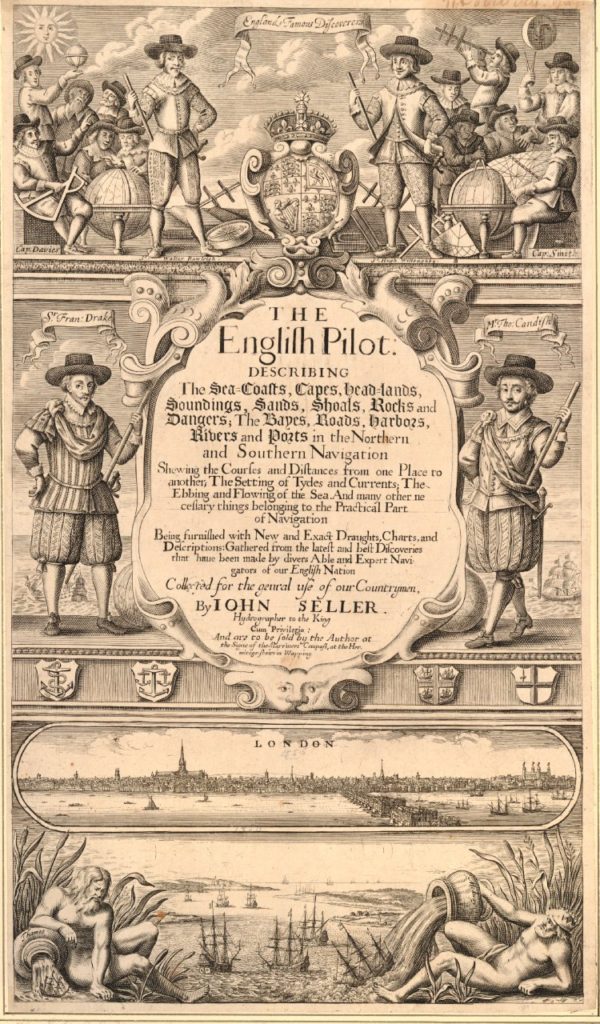

The title page to The English Pilot published in 1671 includes a picture of Willoughby in the top panel of the page, standing to the right of centre.

The lower half of the page shows the Pool of London, the original London Bridge and St. Paul’s Cathedral. Below this are two figures pouring water into the river, one representing the Thames and the other representing the Medway.

This title page fascinates me. It highlights the connections between London, the River Thames, shipping, navigation and the high seas – a connection that is not so relevant to London today, but was so key in the development of London over the centuries.

And on the subject of connections, this post demonstrates why I love exploring London, in that one small area can have the most fascinating connections with the past and how London has developed over the centuries, and it all started with finding a bowling green in Shadwell.