There are many good reasons for a walk along the River Thames, east from Tower Bridge to Rotherhithe. Views over the river, the historic streets, historic architecture and a number of excellent pubs. One of which is the subject of this week’s post – The Angel Rotherhithe.

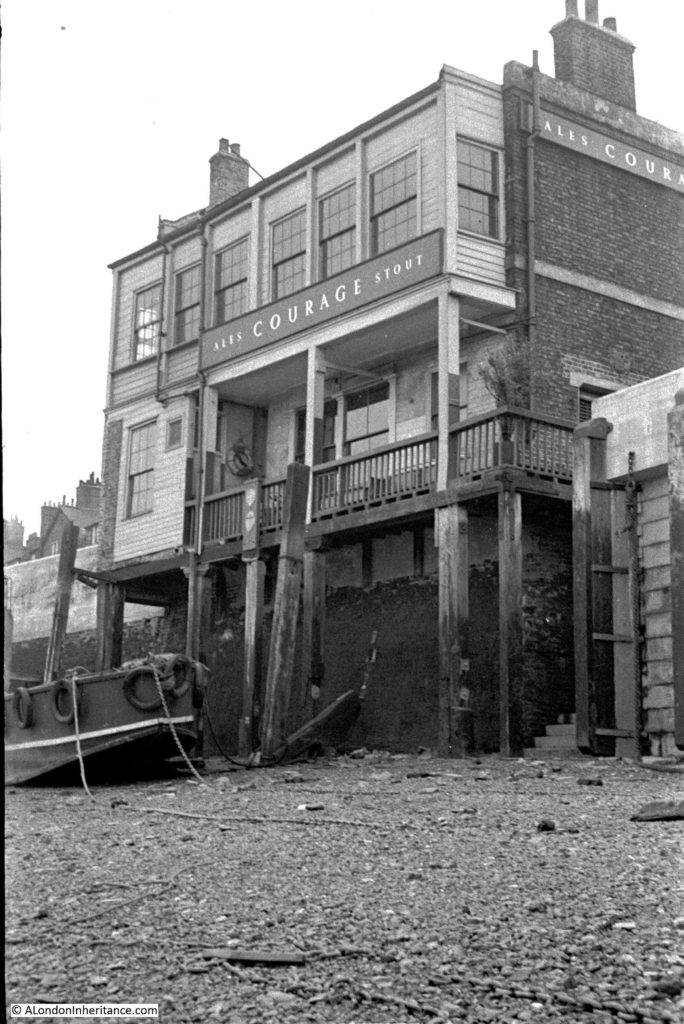

My father took the following photo of the pub from the foreshore of the river in 1951:

I have been meaning to take a photo of the same view for a couple of years, however my previous walks here have been when the tide has not been low enough, or last year when the tide was low, but the pub had scaffolding around the building.

I was lucky on my recent visit as the tide was low, building work had finished and after some early morning rain, the weather was improving. This is the same view of the Angel Rotherhithe in 2018 from the foreshore of the River Thames:

The pub looks much the same despite the 67 years between the two photos. Cosmetic changes, and I suspect some of the woodwork has been replaced.

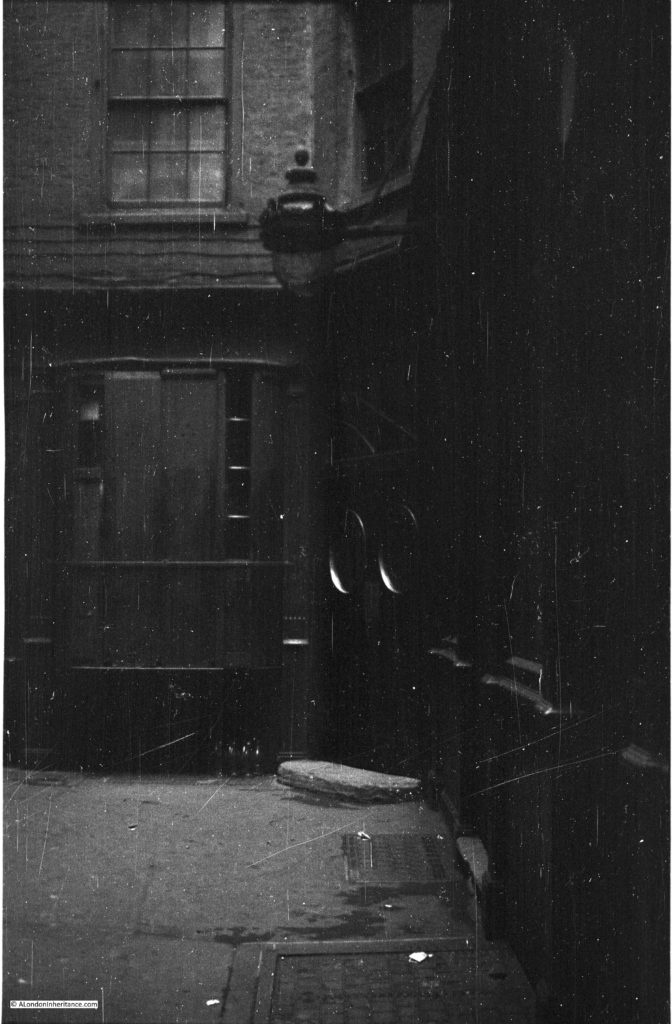

There is one aspect of my father’s original photo that is a mystery. If you look along the balcony facing the river, there is a wooden panel with what appears to be two badges. I have zoomed in on the original negative scan and I cannot make out what they are. I have enlarged and cropped these out to show in the photo below:

They both look to have some form of cross. The lower with a darker cross is a bit more clear than the one above. I do not know if the lower badge is that of the City of London.

They are on the balcony facing the river, so I suspect have some relevance to the working river. I would really appreciate any information as to what these symbols may mean.

There is easy access to the foreshore here, there are stairs just to the right side of the pub in the above photo, these are the Rotherhithe Stairs with a better view in the photo below:

A short distance along the river to the east are another set of stairs, the stairs I used to walk down to the foreshore, shown in the photo below. These are the modern replacement for the King’s Stairs. One of the many sets of stairs that used to exist down to the river.

From the foreshore it is possible to appreciate the tidal range of the River Thames. The green algae on the walls show the normal tidal range, with occasional high tides reaching further up the wall.

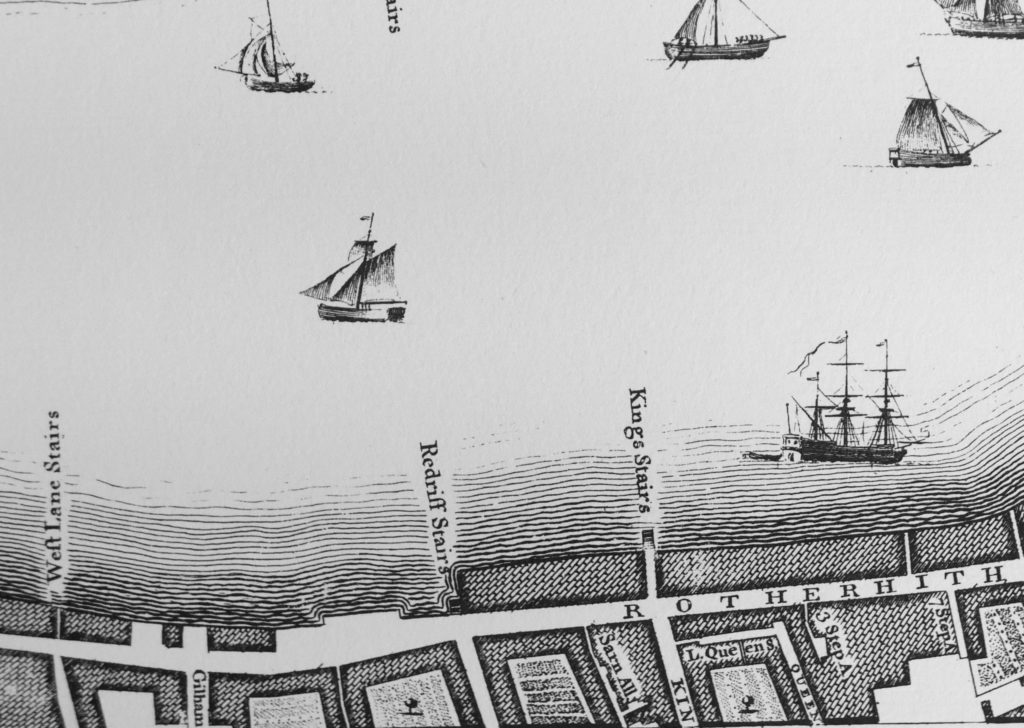

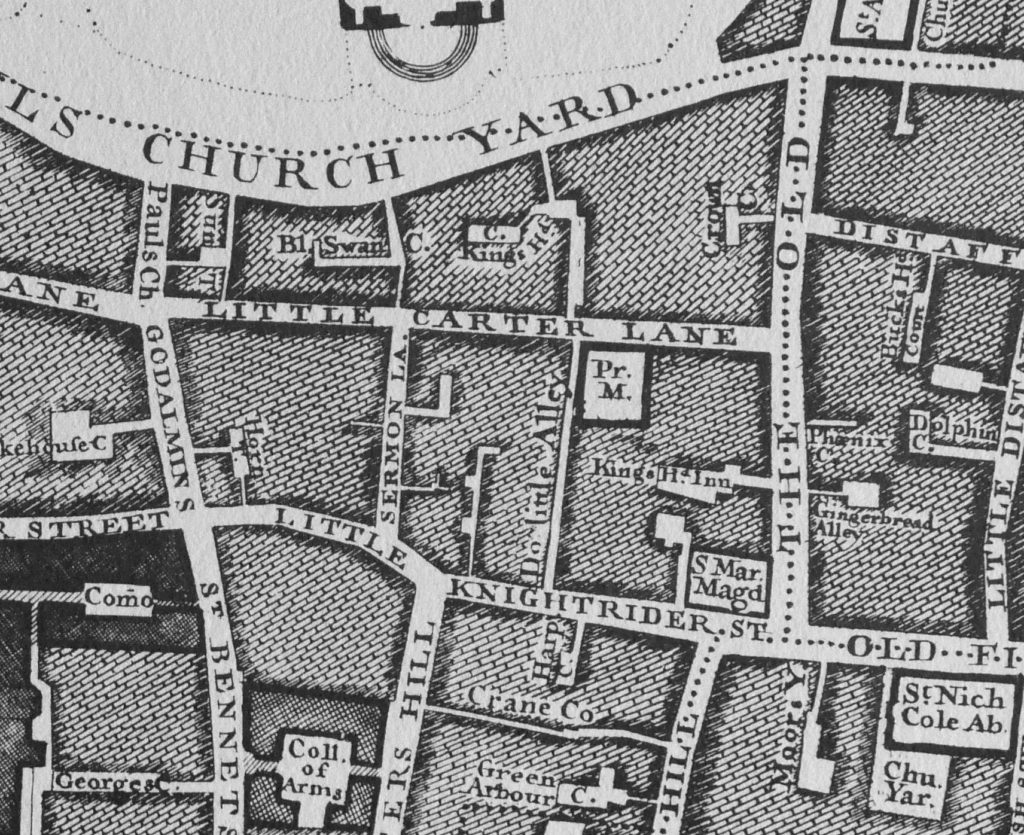

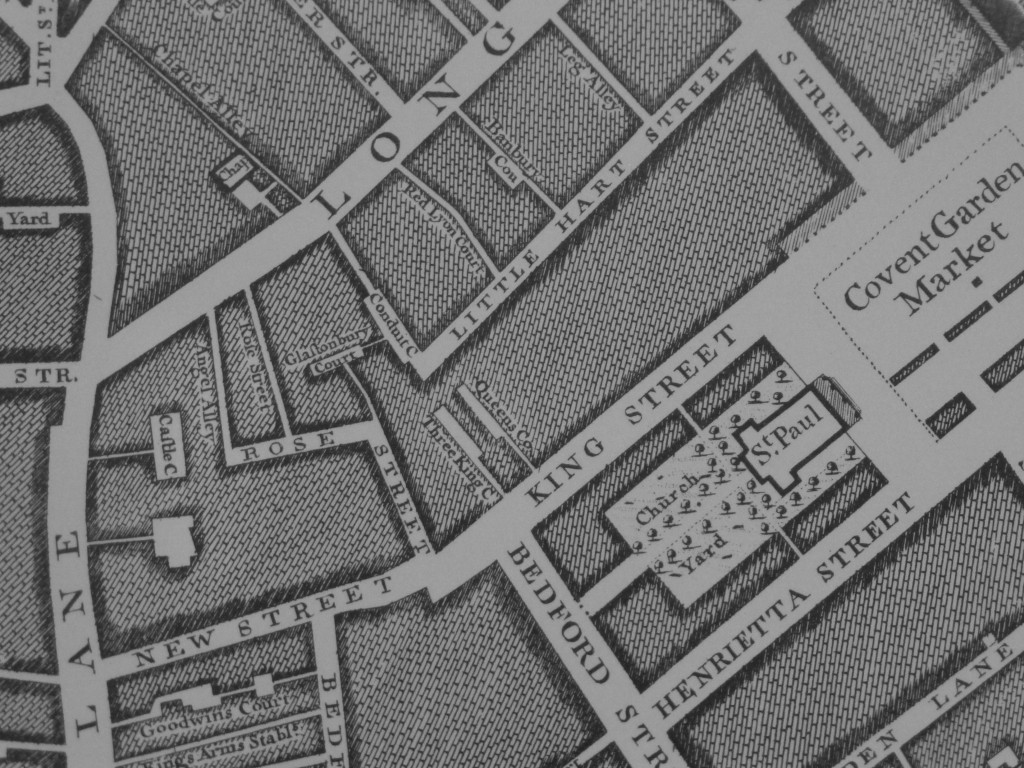

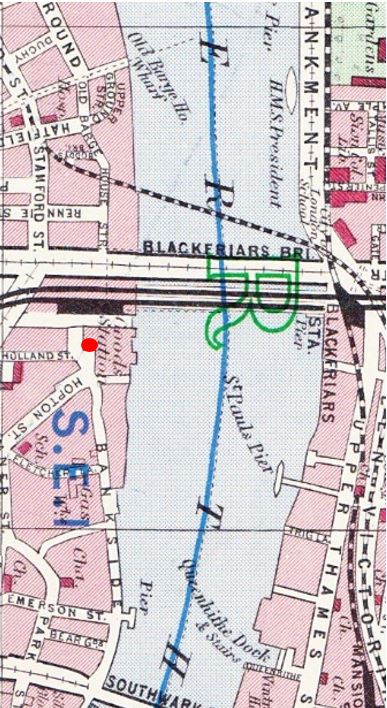

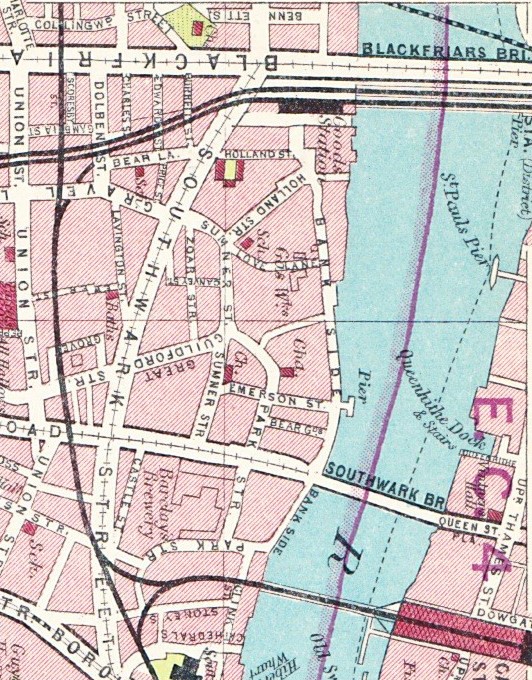

The King’s Stair’s and Rotherhithe Stair’s have been providing access to the river for many centuries. They were both shown on the 1746 Rocque map of London, although the Rotherhithe Stair’s were recorded as Redriff Stair’s (one of the earlier names for Rotherhithe).

I suspect that the wooden posts supporting the balcony of the pub have been replaced since my father’s photo. The remains of the angled post shown in the 1951 photo can still be seen, the top part of the post showing considerable signs of decay. The posts also look as if the upper parts have been renewed but the lower section is older. The upper parts are smoother than the lower and they appear of different age.

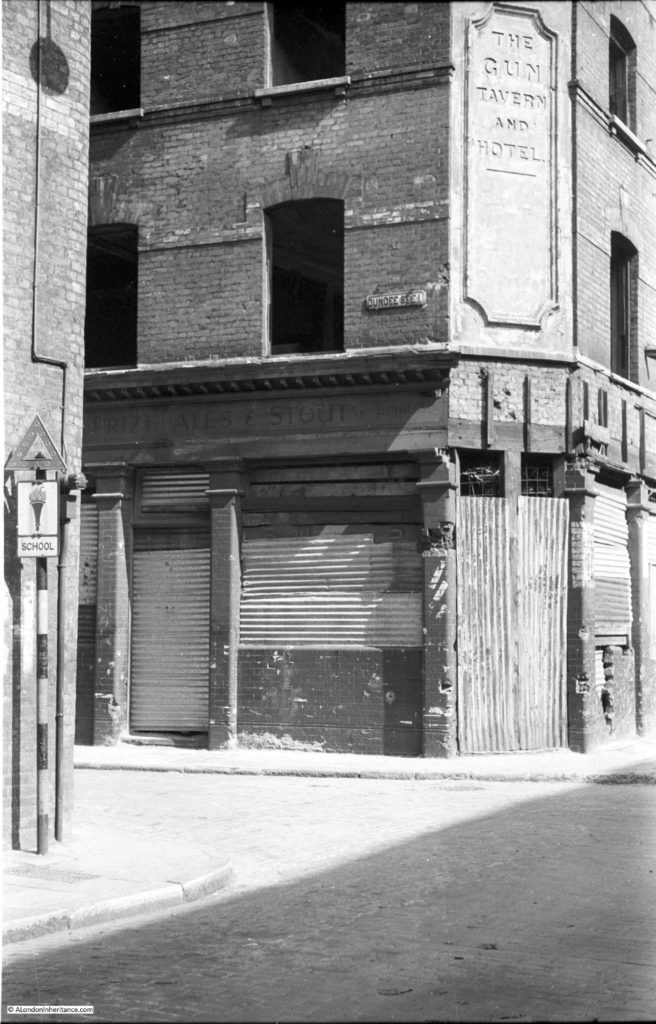

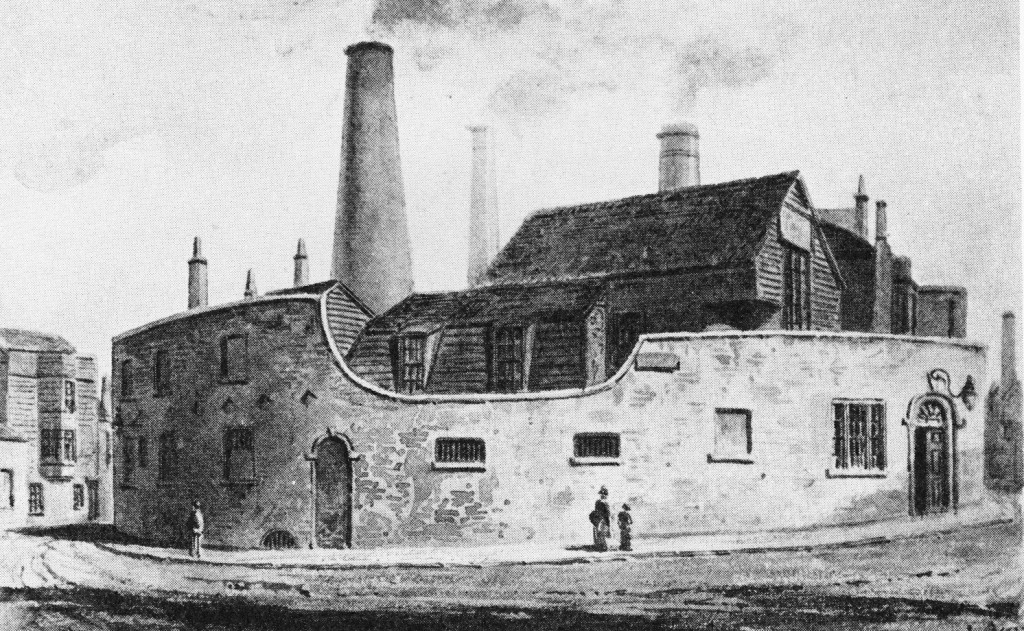

The Angel Rotherhithe is a wonderful early 19th century pub. Grade II listed and dating from the 1830s. The listing states that the building potentially includes material from a 17th century building that occupied the same position. The entrance is on the westerly facing corner of the building, adjacent to the stairs leading down to the river.

Over the years the pub has served the many, varied functions of a public house, over and above selling alcohol. It has hosted inquests, been the meeting place of clubs and societies, sales have taken place and the pub has been used as a contact address. Customers have occasionally attempted fraud (a common method appears to be demanding change when not originally having handed over any note or coin), along with the time in 1845 when the landlady was charged with allowing drinking in the Angel at 11 in the morning on a Sunday.

The Angel has open space on either side of the pub building. Space once occupied by the many working buildings along the river, but today transformed into a space to admire the full sweep of the Thames.

To the west of the Angel, a cat sits on the river wall.

The cat is part of a group of figures by the sculptor Diane Gorvin titled “Dr Salter’s Daydream”.

The Salter’s were a family who had a considerable impact on the lives of those living in Bermondsey.

Ada Brown was born in 1866 and moved to Bermondsey to work in the slums in one of the Settlements established across London. Alfred Salter was a student at Guy’s Hospital when he met Ada at the Bermindsey Settlement.

They married in 1900 and lived in Bermondsey. Both Ada and Alfred worked tirelessly to improve conditions in Bermondsey and Rotherhithe.

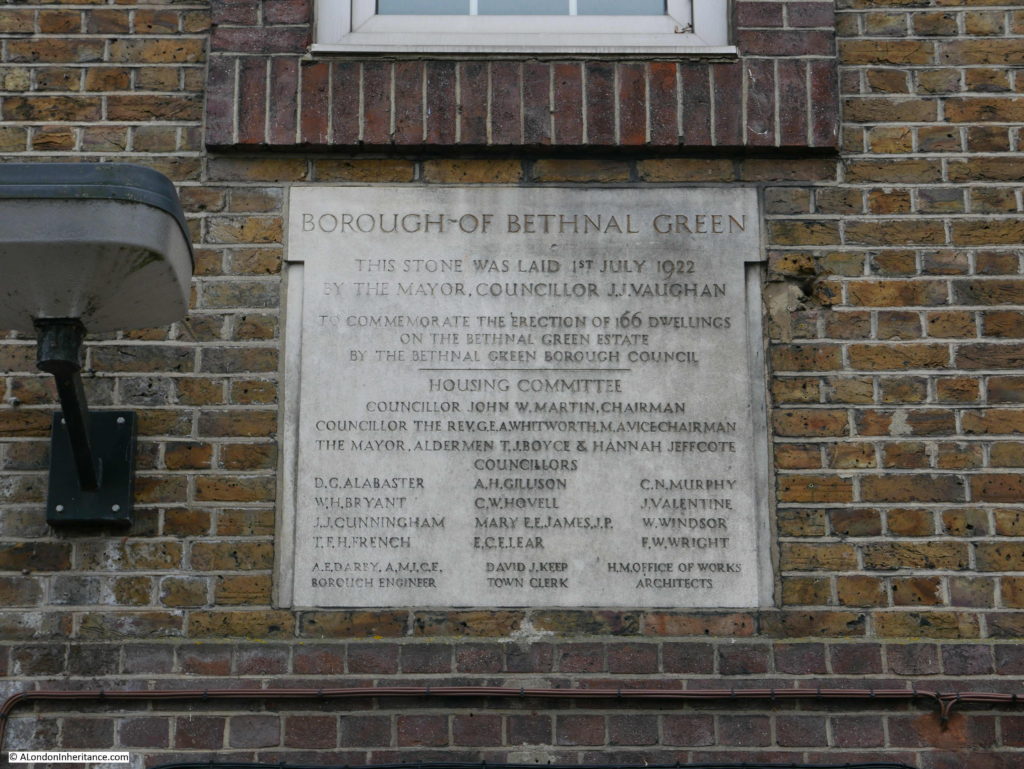

Ada became a Labour councilor, the first woman councilor in Bermondsey in 1909 and set about recruiting women workers to trade unions to organise against the terrible working conditions in the area’s factories.

Alfred was elected MP for Bermondsey in 1909, the same year as Ada was elected Mayor.

Health for those living in Bermondsey and Rotherhithe was not good. Tuberculosis was rife and average life expectancy was at the low end of what could be expected across the whole of London.

Long before the NHS they promoted free medical treatment and education on how hygiene could improve health and prevent disease.

These initiatives resulted in the death rate being reduced from 16.7 per 1,000 down to 12.9 per 1,000 of population in the five years following 1922.

Alfred worked on slum clearance programes whilst Ada focused on how the appearance of an area could improve living conditions, initiatives such as tree planting, public gardens and flower planting.

Ada died in 1942 and Alfred three years later in 1945. The group of statues next to the Angel reveal a tragedy in the lives of the Salter’s. The third statue, up against the river wall is that of a young girl. This is Joyce, their only child who died from scarlet fever in 1920, aged 8.

The title of the group is “Dr. Salter’s Daydream” and represents Alfred in his old age, dreaming of happier times with his wife Ada, their daughter Joyce and her cat.

I am not sure what Alfred would have thought with the statues being located next to the Angel pub as newspaper reports of his death included:

“An advocate of total abstinence, Dr. Salter once declared that he had seen many M.P.s drunk in the House and added that no party was exempt from that failing. He refused to withdraw the statement, and later spoke of Labour Members who ‘soak themselves until they are stupid’. Clergymen and ministers who drank in moderation, he declared, were worse enemies to the temperance cause than clergymen who were drunkards.”

He was also a pacifist. In coverage of local elections in 1907, the London Daily News reported that:

“Bermondsey’s other Councillor, Dr. Cooper, was also elected to Parliament last year. He immediately resigned from the L.C.C. and the seat was retained by Dr. Alfred Salter, who is again before the electors. Dr. Salter is a Quaker and life abstainer, and has resided at the Bermondsey Settlement for several years. He got his municipal training on the Bermondsey Borough Council. As a Passive Resister he has been to prison nine times.”

Dr. Alfred Salter in 1907:

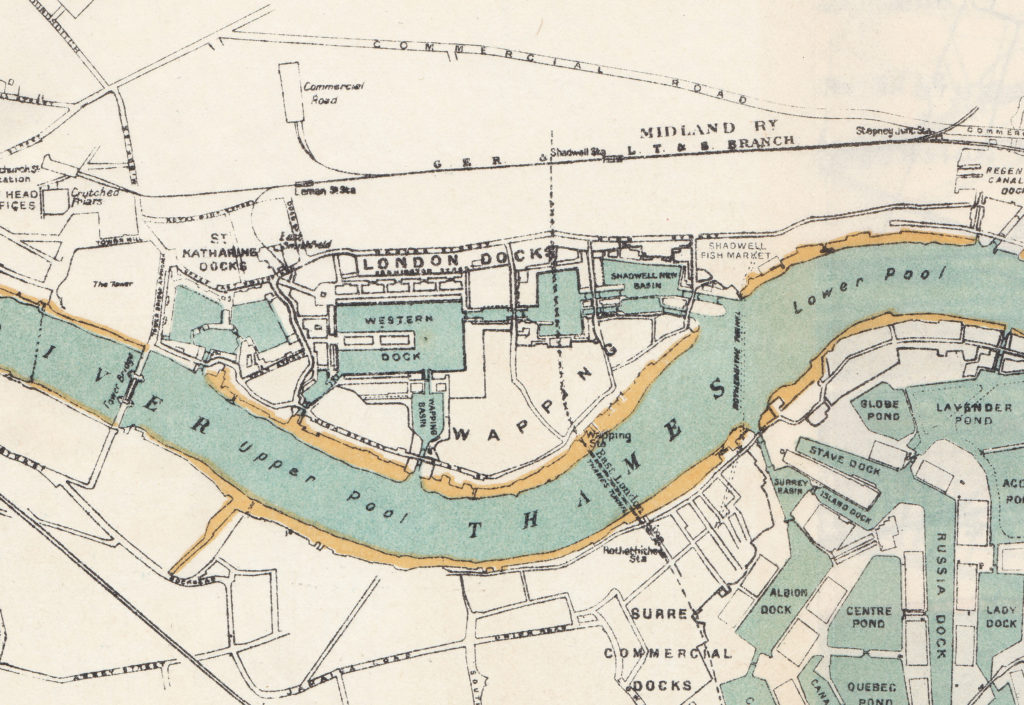

The open space next to the Angel provides some wonderful views of the river. Starting with the westerly view towards the City and Tower Bridge:

Directly across the river to Wapping:

Looking east along the river towards Shadwell:

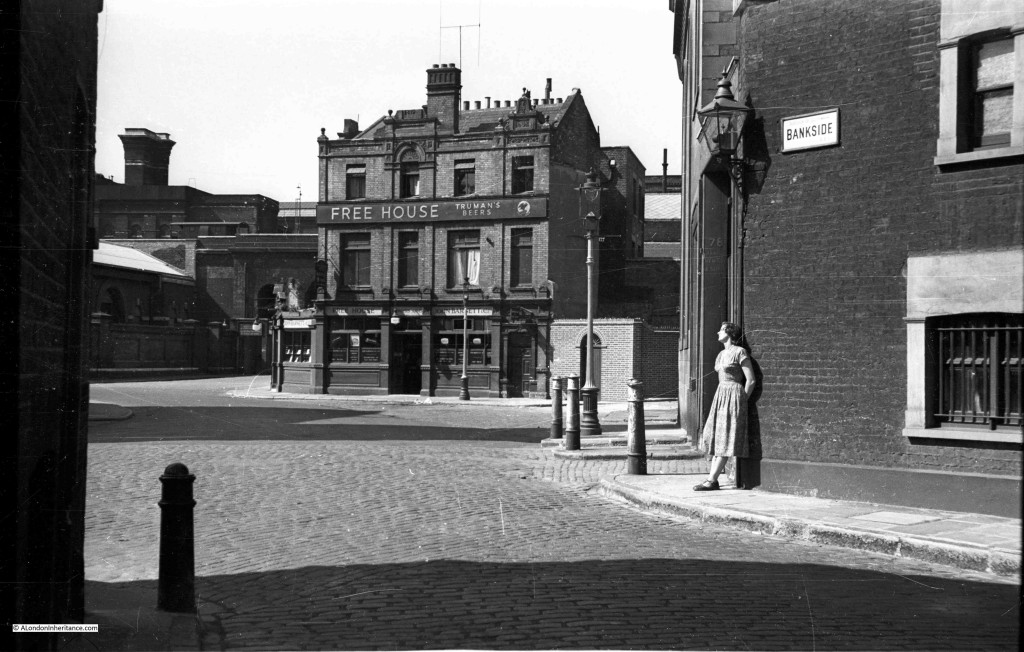

Three years before my father took the photo of the Angel at the top of the post, he took a river trip from Westminster to Greenwich and took photos along the way. The following photo shows the Angel in August 1948.

Barges fill the river and large warehouses fill the space to the right of the Angel.

The large, flat roof warehouse was relatively recent. This was a bonded tobacco warehouse built in the 1930s in place of a previous 1907 warehouse (which was probably in place of earlier warehouses).

The LMA Collage archive includes a photo from 1956 of the Angle and the large, 1930s warehouse:

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_040_81_9834

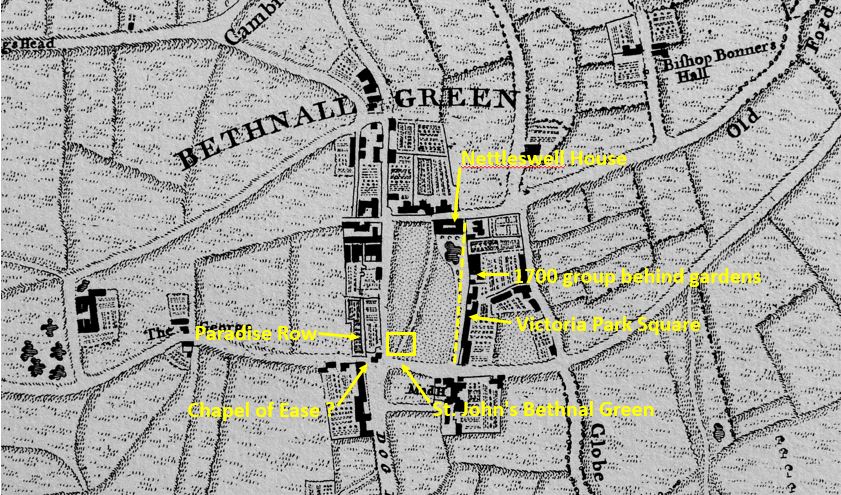

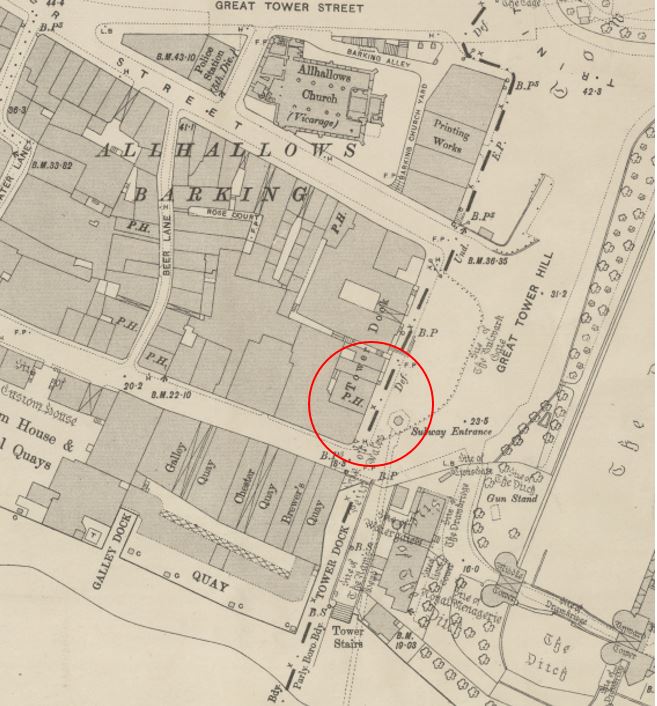

Surprisingly, given the size of the warehouse building, the remains of a much earlier building survived underneath. Much of the space that was occupied by the warehouse is now a large grassed space just to the south west of the Angel. There are the remains of some walls visible above the grass, the remains of King Edward III’s Manor House.

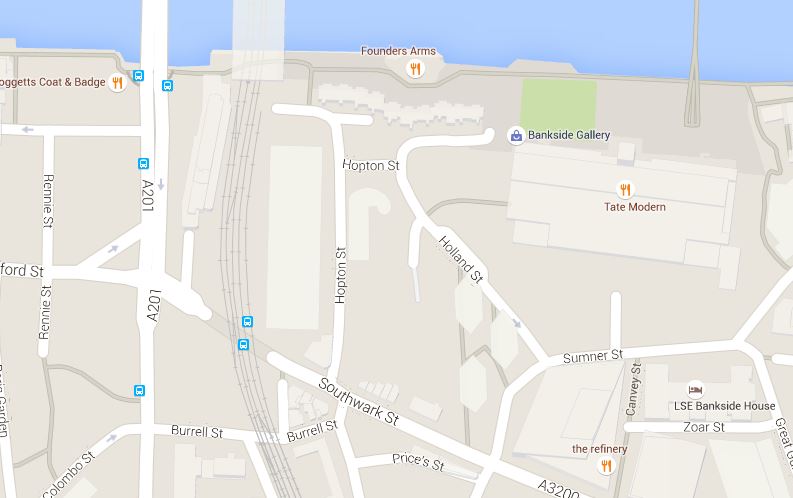

Edward III reigned for a surprising long 50 years (for the fourteenth century) from 1327 to 1377. The manor house was constructed on a low lying island when much of the land here was still marsh.

The manor house consisted of a central open courtyard surrounded by buildings with a moat around three sides. The fourth side was open to the River Thames as the land on which Bermondsey Wall now runs had not yet been reclaimed.

There is no written record of why Edward III had a manor house in what must have been a rather damp and isolated place in the 14th century. The information panel states that there is documentary reference to the housing of the king’s falcons ‘in the chamber’ so perhaps it was the isolation and marshy land that provided the perfect place for falconry, at a location easy to access from the river and not far from the City.

The growth of industry eastwards from the City resulted in construction of embankments and walls along the river which cut off the house from the river by the end of the 16th century. The buildings were sold and used for a variety of purposes, before being integrated within the expanding warehouses along the river in the 18th and 19th century.

Some of the walls were still standing at the start of the 20th century when they were part of a 1907 warehouse.

The walls that remain above the current ground level may not look all that impressive (although to me, finding 14th century remains in Rotherhithe is impressive), however much of what was found when the site was excavated in the 1980s was buried for protection.

The buried southern wall includes the remains of what may have been a staircase. The manor house extended beyond the grassed area to include the houses that can be seen to the south and three medieval stone lined cesspits were found during excavations and preserved under these houses.

Excavations also identified a possible late Bronze Age ditch, two Roman pits and additional medieval features, so perhaps this area close the river was reasonably dry and attracted people to build, live and work here for many centuries.

The view from the opposite corner to the above photo, looking back over the remains of the manor house towards the Angel Rotherhithe.

This is a fascinating area. Within such a small area there are two historic stairs down to the river, a group of statues commemorating a couple that did much to improve the conditions of the people of Bermondsey and Rotherhithe, as well as the grief they must have felt in the loss of their only child, along with the remains of a 14th century Manor House.

The Angel Rotherhithe is also one of my favourite places to stand with a pint on a sunny day and watch the Thames flowing past.