I started the blog “A London Inheritance” five years ago, at the end of February 2014. I really did not think I would get this far, or be able to keep up the rate of a post a week (which I know is a very low rate compared to some bloggers).

The original aim of the blog was to track down all the locations of my father’s photos, and also to provide a kick for me to get out and explore more of this wonderful city. I hope I am still true to that original aim, and I feel that I have explored and learnt so much during the last 5 years. Getting out and walking really is the best way to discover London.

I still have very many photos where I need to track down the location, new places to visit, themes for walks – I just need to find the time.

Can I also offer my thanks to everyone who reads my posts, subscribes, comments and e-mails. I apologise for being so dreadfully bad at responding to these. When I finish one blog post it is a panic to get the next completed in time. Work and other activities take time, and I am very aware that many of my posts are too wordy and need a bit of a rewrite, so I apologise for inflicting these on you.

I was not sure what to write about to mark five years, so what follows is a bit of a brain dump on the past year, what fascinates me about the process, photography, and some thoughts for the future.

The Most Read Post

My most read post of the year is one that I wrote the previous year.

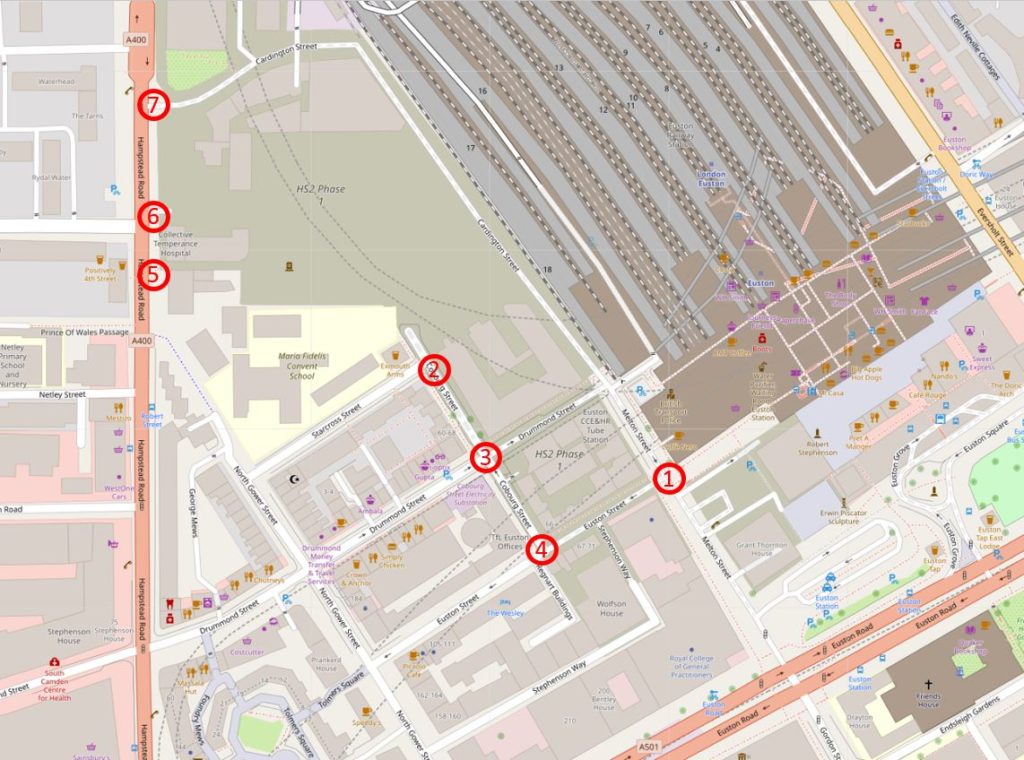

In August 2017 I wrote about St. James Gardens. I had photographed the area shortly before the site was closed ready for the archaeological excavation in preparation for the extension of Euston Station for HS2.

This post was popular at the time and consistently ranks high for viewers. Occasionally there is a very high peak of viewers which usually happens when there is news of a discovery at the excavation.

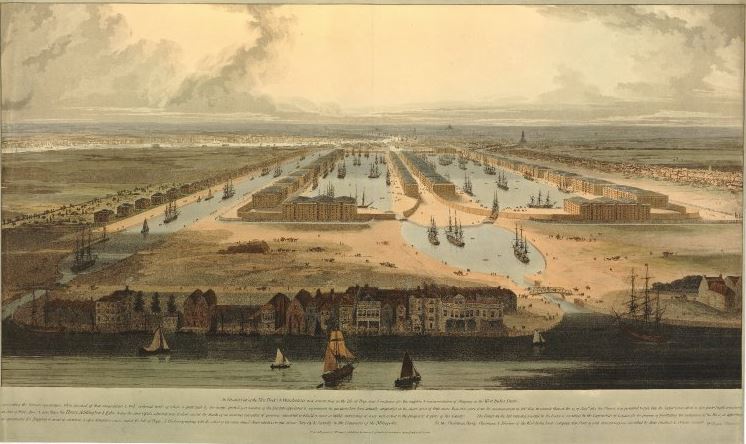

In January it was announced that the grave of Captain Matthew Flinders had been discovered in St. James Gardens. Flinders was the first European to circumnavigate Australia in HMS Investigator, demonstrating that Australia was a single continent.

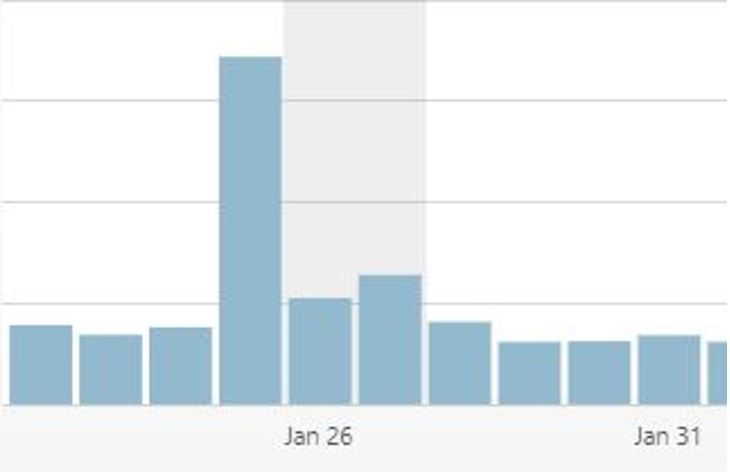

The following graph shows my site states for the days around the announcement of Flinders discovery. The peak day of the announcement was Friday, January 25th and the blog received several thousand views, the majority all going to the page on St. James Gardens that I had written about in August 2017.

The excavations at St. James Gardens and the changes around Euston are, rightly, of considerable interest. I have e-mailed questions to HS2, but get the same response that, judging from comments on the blog, everyone else gets – a very standard response with answers only to very basic questions.

I can understand why, the scale of the work is considerable and must be handled in a sensitive and considerate manner, but I do suspect it would help with the public perception of the work around Euston if more regular detail on the excavations was made available.

The preparation for HS2 also highlights the rate and scale of change. Just within the last couple of years a whole area of streets have been cordoned off and will soon become part of a much enlarged Euston station. I returned to the site earlier this year, and plan to make an annual visit to photograph the changes as HS2 and the new Euston station gradually complete.

London Ghosts

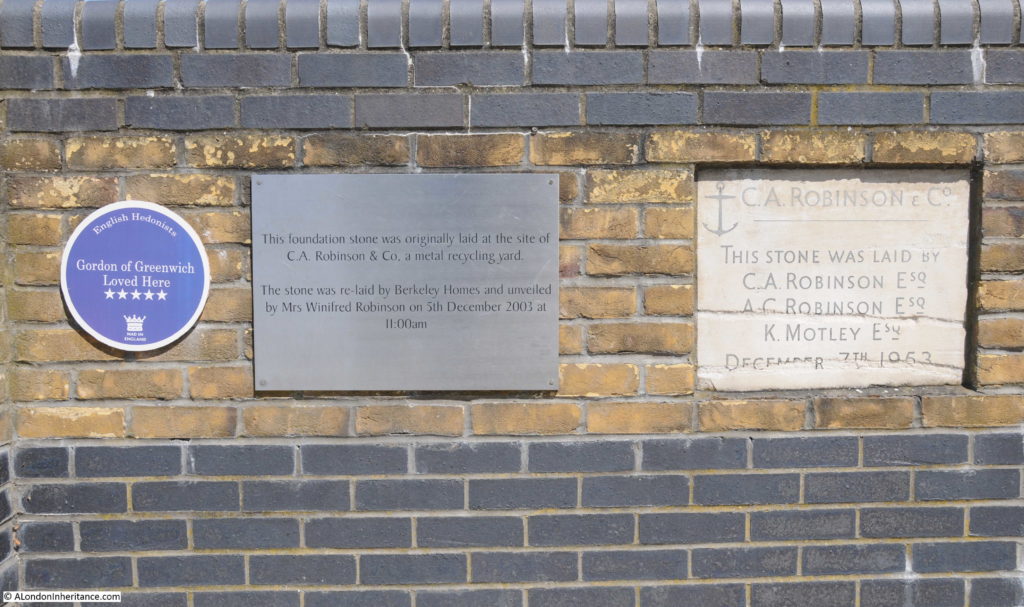

By ghosts, I do not mean the traditional definition, rather the traces that are left behind by the millions of people who have lived, worked, or just passed through London. Not necessarily those who are famous and have blue plaques or other memorials, rather finding a trace of someone who had a very personal connection with the city.

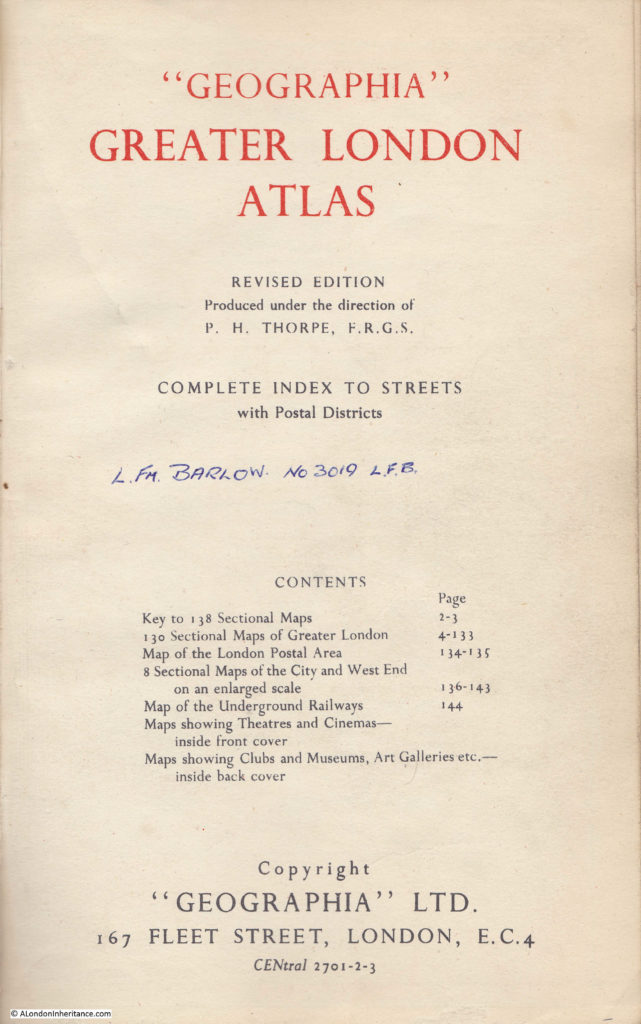

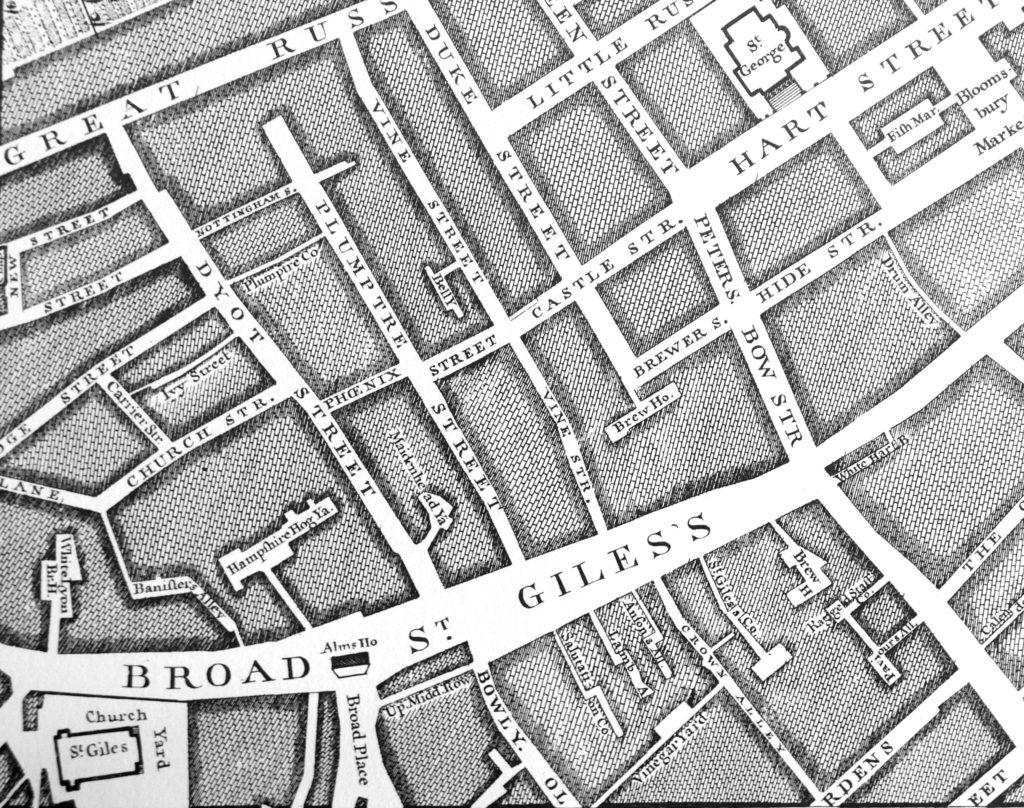

I love London books and these often provide a link. One of my favourites I found in a copy of the “Geographia” Greater London Atlas. I am not sure of the exact date, but this version was published towards the end of the 1950s or very early 1960s.

On the title page is the name of the owner – Leading Fireman Barlow, No. 3019 of the London Fire Brigade.

The atlas itself is fascinating enough, lots of lovely pages of colourful maps, but the street index tells the story of how a London Fireman must have kept up to date with street changes across London – long before the days of Satnavs, Google Maps and the IT that is now deployed to a fire engine.

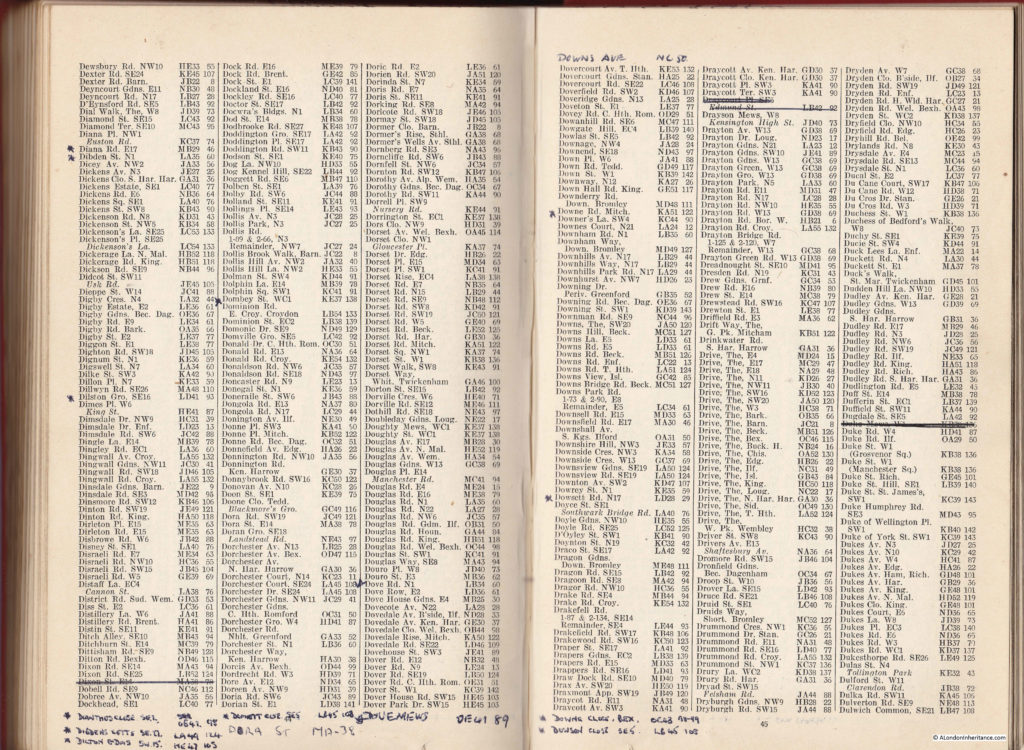

In every single page of the street index, streets have been neatly crossed out, and new names and references have been written at the bottom of each page.

What it appears that Leading Fireman Barlow was doing was keeping his atlas up to date as streets disappeared and new streets were built across the city. This was a time of considerable change with post war rebuilding gathering pace.

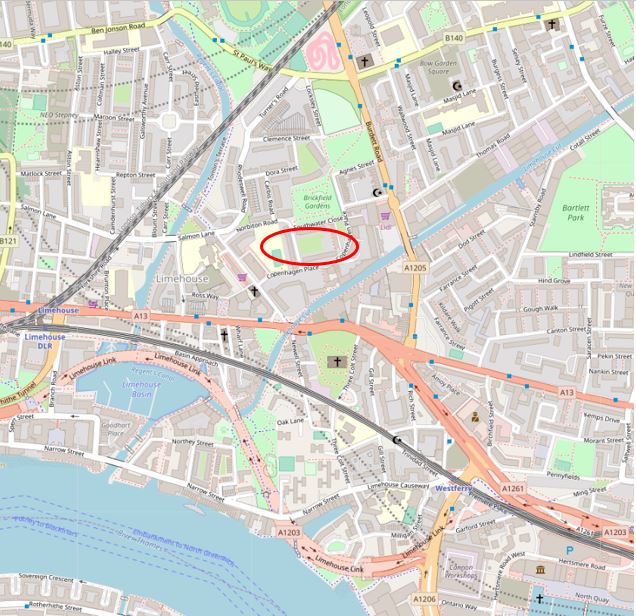

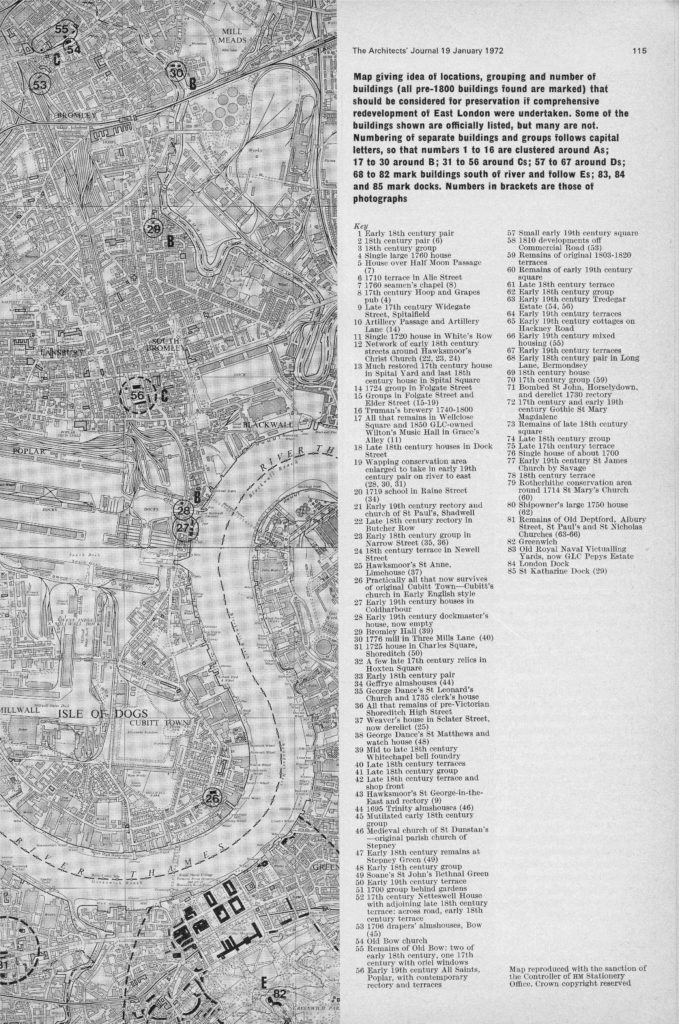

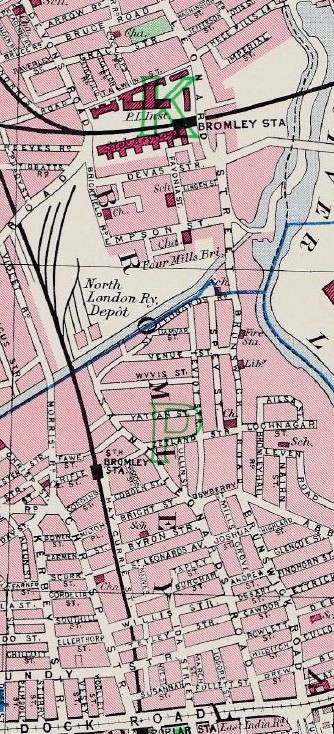

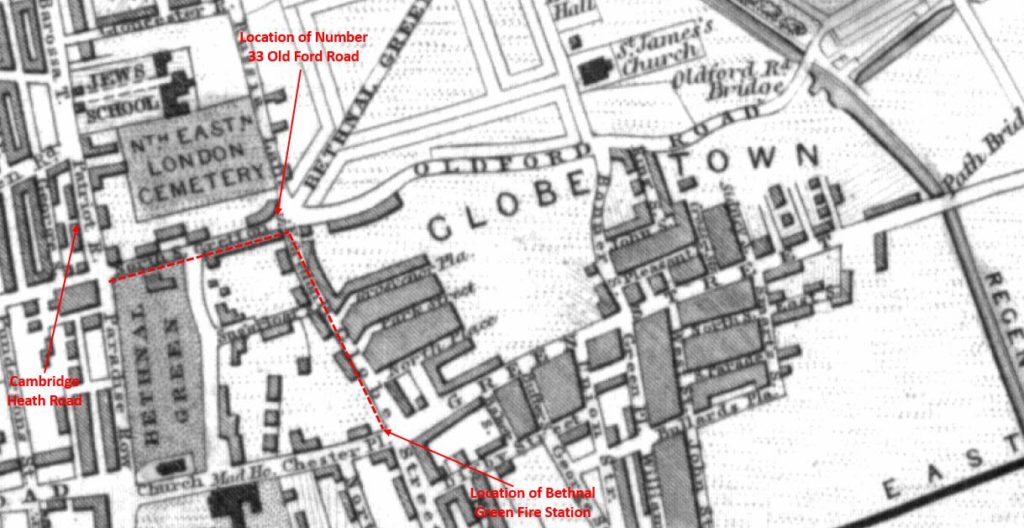

A couple of examples. In the above pages, at lower left, Dixon Street E14 has been crossed out. Looking in the atlas, Dixon Street is one of a cluster of streets in Limehouse, just to the north east of the Regent’s Canal Dock.

This area was considerably rebuilt in the late 1950s and 1960s with the loss of many of the streets that once covered Limehouse. The following map shows the area today with the original position of Dixon Street marked.

Map © OpenStreetMap contributors.

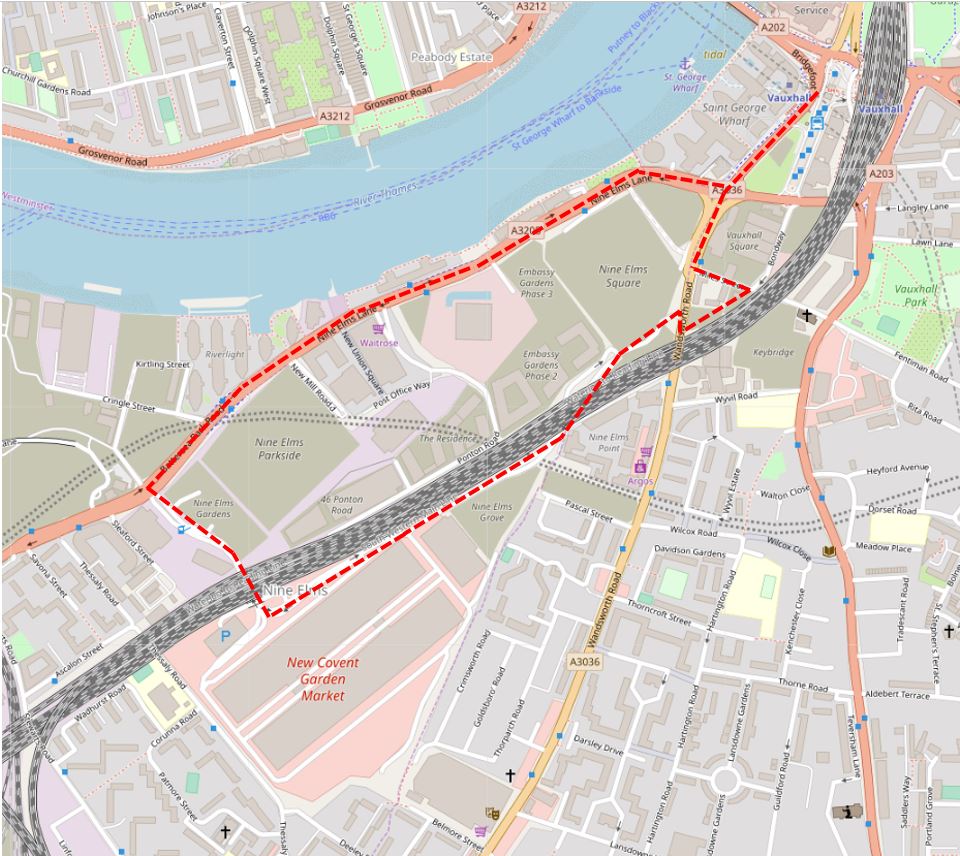

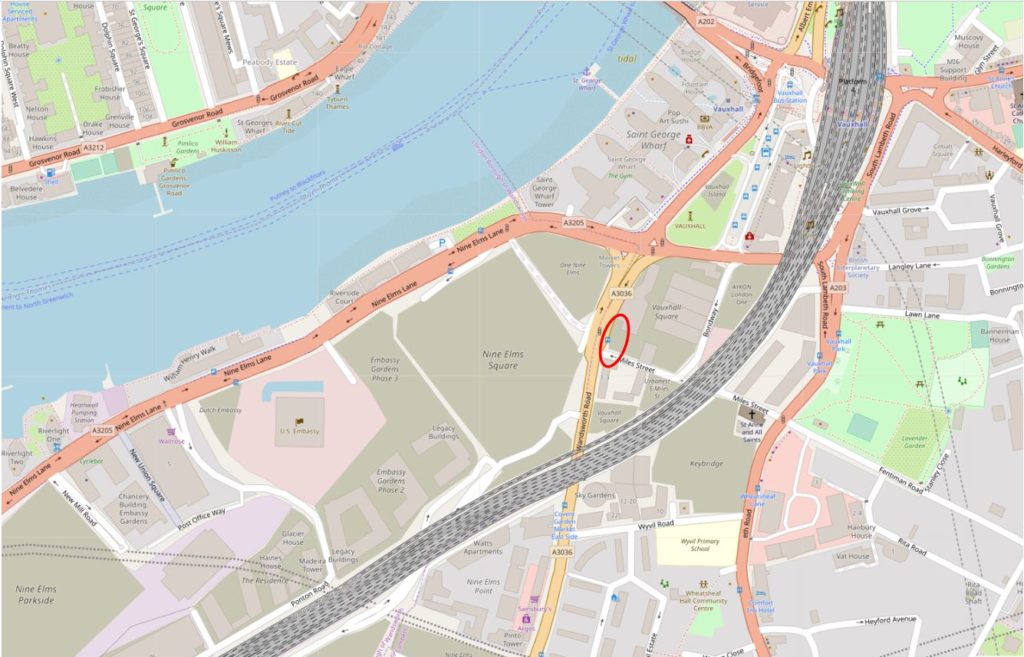

As well as the loss of streets, Leading Fireman Barlow had to keep up with new streets. At the bottom of the same index page is a reference to Dilton Gardens, SW15, HE47, 103. The last number is the page number and the preceding number is the grid reference within the page.

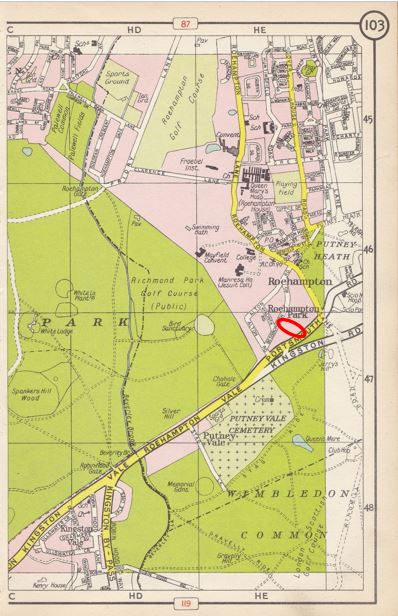

Turning to page 103 and we are now in south west London, just to the east of Richmond Park. I have marked the location of the new street with a red oval.

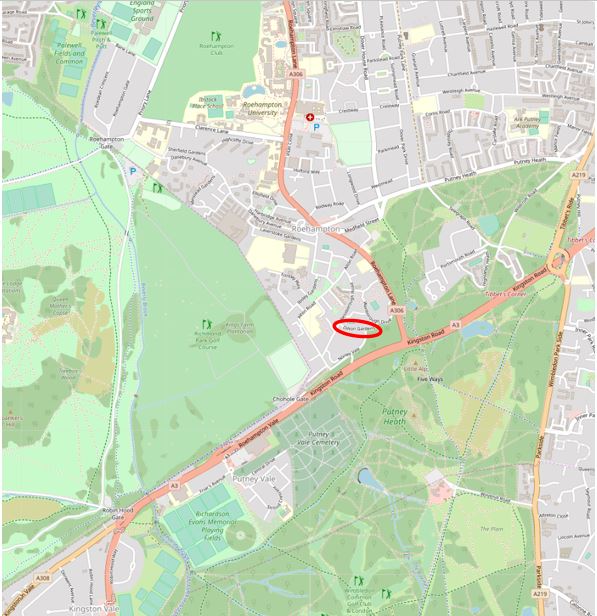

The map of the area today with Dilton Gardens ringed. The map today shows the large area of infill between the boundaries of the park and Roehampton Lane which has been built since the publication of the atlas.

Map © OpenStreetMap contributors.

What surprised me was the range of updates, covering the entire area of the atlas. Leading Fireman Barlow was interested in the whole of Greater London, not just his local fire station. I also wonder from where he got the information? Was this official London Fire Brigade policy to provide updates to staff and did they keep their own atlases up to date? This was at a time when a fireman would have needed to navigate the streets of London using their local knowledge or with paper maps.

Leading Fireman Barlow was very conscientious in updating the atlas and I would love to know why and how.

I found a very different trace of a Londoner in a book I purchased a couple of years ago in a second hand bookshop in Lichfield.

This book, “Achievement – A Short History of the LCC” was published in 1965.

The book itself is a fascinating read on the London County Council, mainly focused on the years 1939 to 1964, however what turned the book from a printed copy of information, into something with a specific history was the presentation slip on the inside of the book.

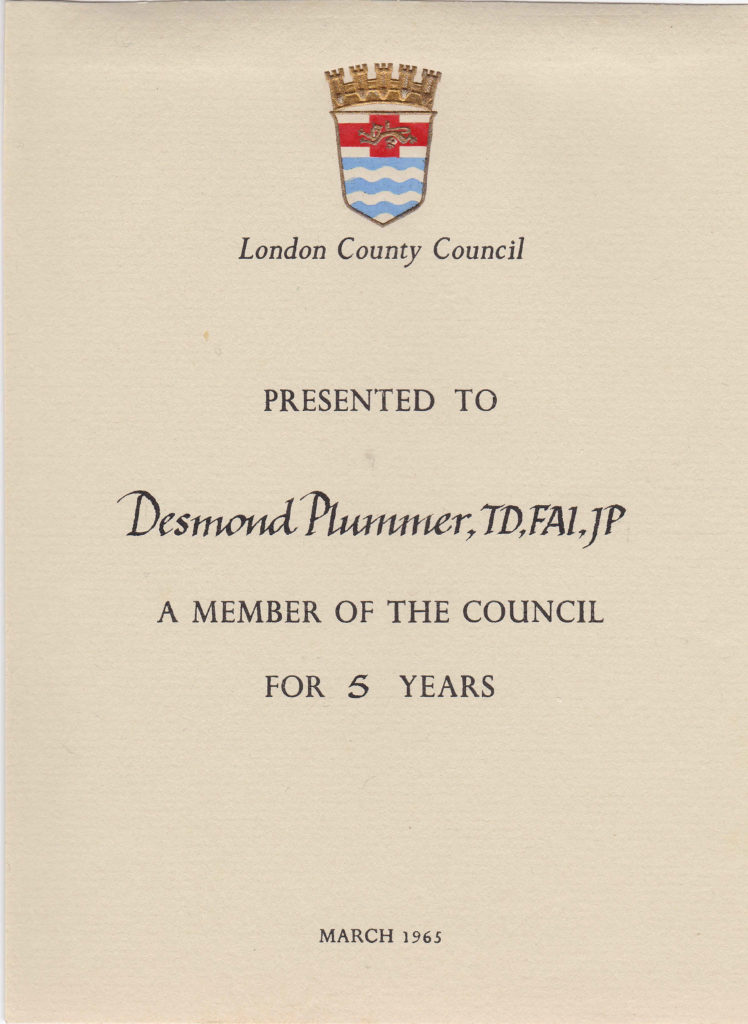

Desmond Plummer was the Conservative Councillor for St. Marylebone to the London County Council from 1960 until 1965. The date is relevant as March 1965 was the last month of the London County Council as the Greater London Council (GLC) took over from the 1st April 1965.

After the formation of the GLC, Plummer was elected leader of the Conservative opposition and became leader in 1967 when the Conservatives won a majority on the GLC. He would continue as leader of the GLC until 1973.

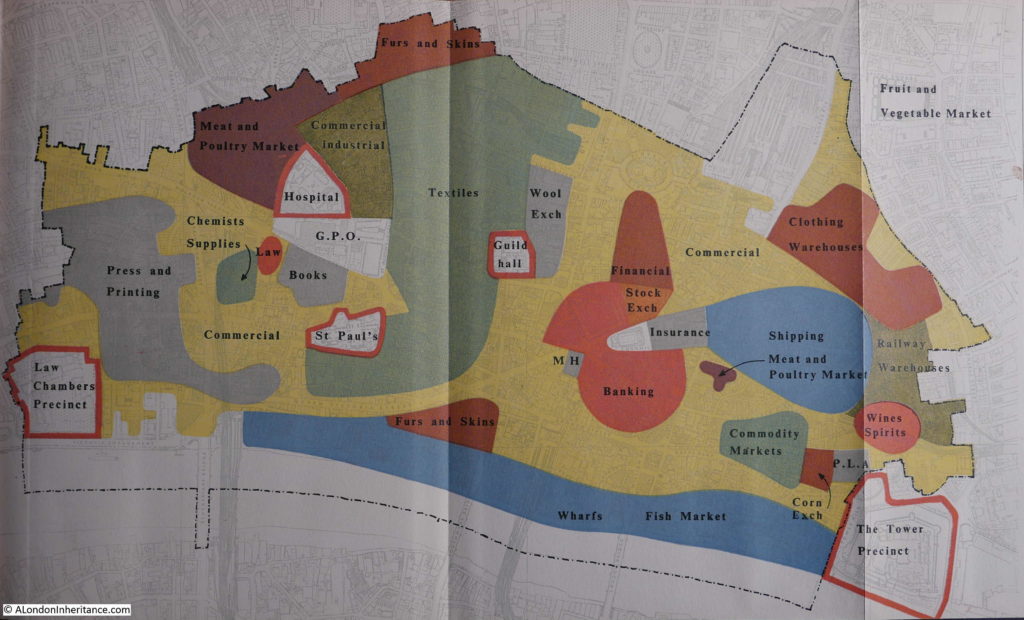

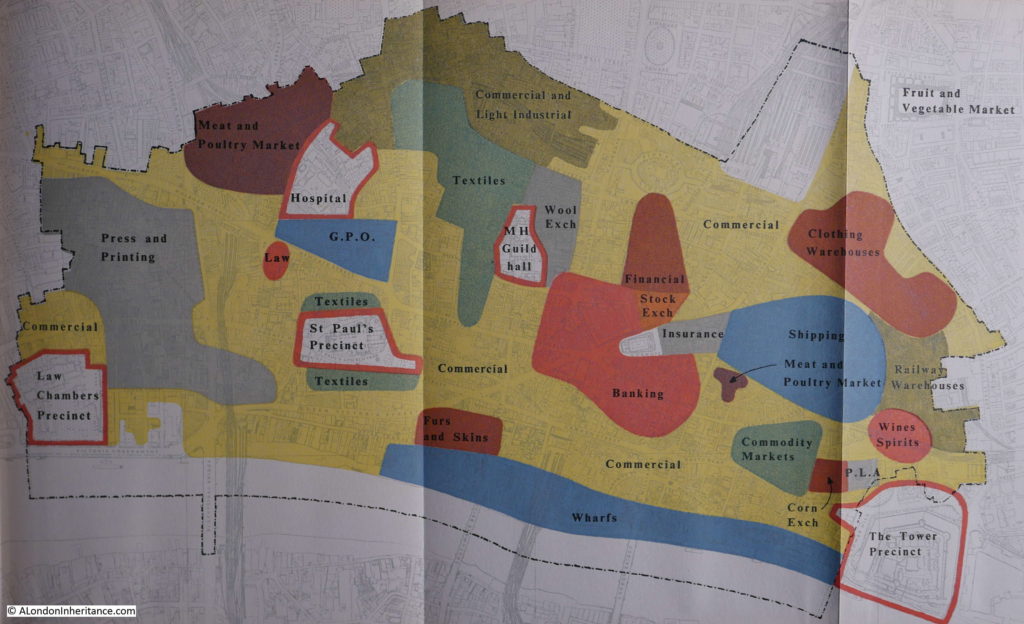

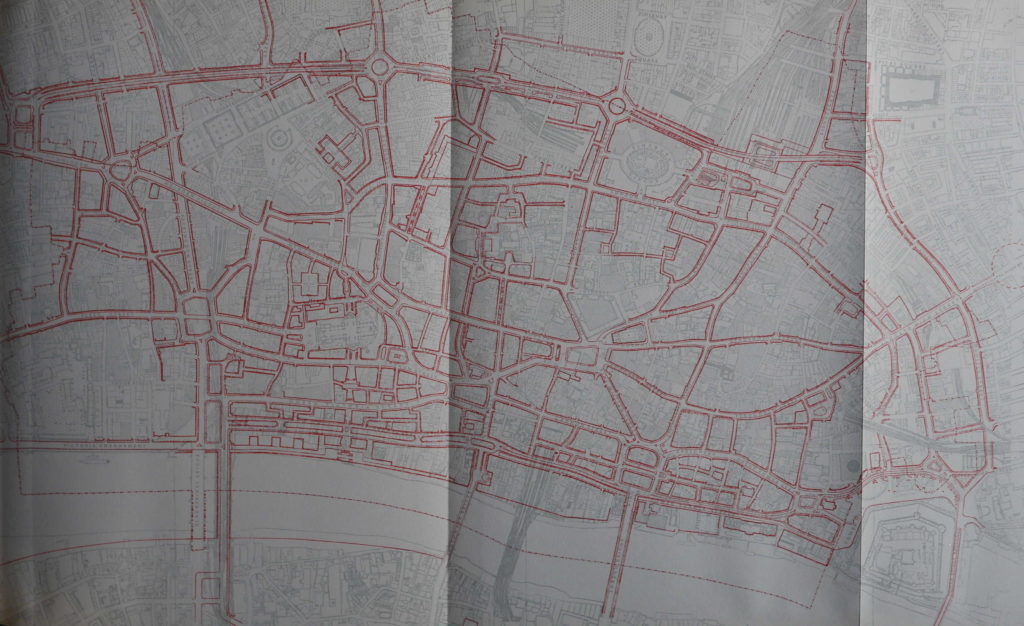

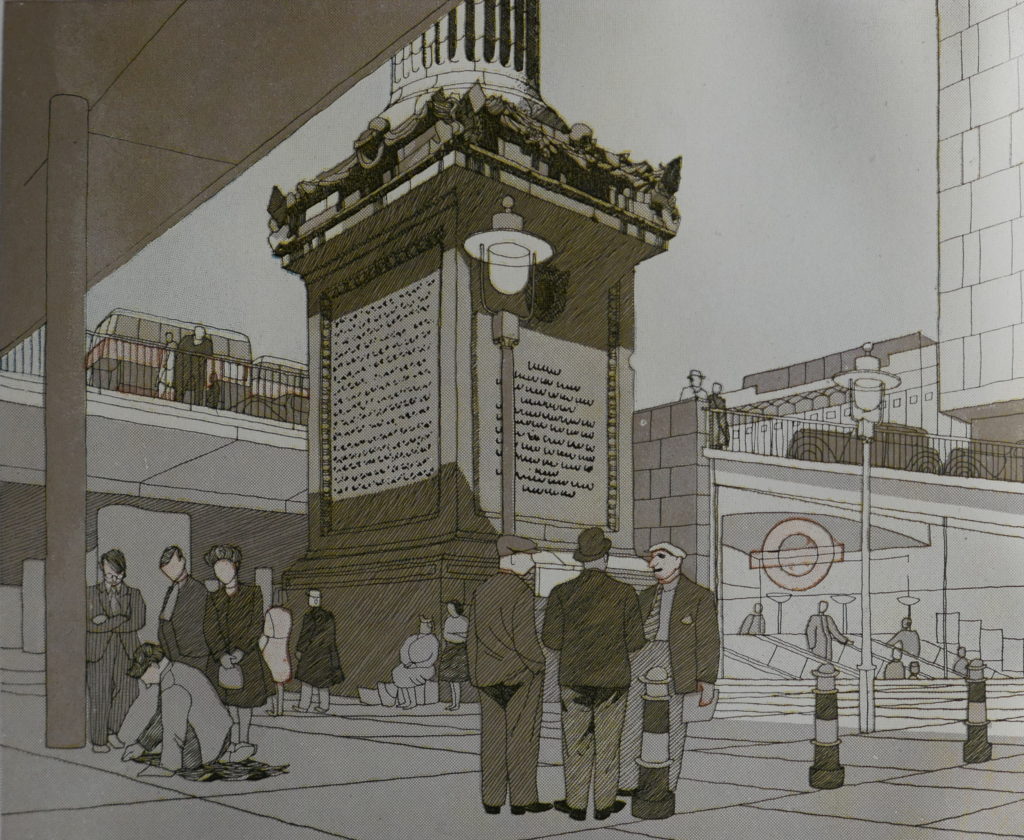

Plummer was a firm believer in the need to upgrade London streets to support the growing levels of traffic, and during his time as Leader, the Westway was built between Marylebone and Acton. He was also in favour of the London Motorway Box scheme, which would have seen the construction of a 30-mile-long, eight-lanes-wide elevated inner ring road (very similar to the schemes published in the “The City of London – A Record Of Destruction And Survival” in 1951). Thankfully, this did not get built.

He died in October 2009 at the age of 95. I do wonder how the book presented to him in the last month of the London County Council came to be in a bookshop in Lichfield?

London Photography

My blog is based on photographs. Tracking down the location of my father’s photos from the late 1940s onward has been a constant theme for the blog.

I started taking photos when as children we were taken on walks through London. My very first camera was a Kodak Instamatic. It used a 126 film cartridge which made it very easy to use as the cartridge slotted directly into the back of the camera. The format of the negatives and the printed photos was square rather than the rectangular output of traditional 35mm film.

The camera only had two light settings, bright and shady, so getting perfect photos back from being developed at Boots was a bit hit and miss. This simplicity did ensure the camera was ideal for a very young beginner.

I recently found some of my early London photos taken with the Kodak Instamatic in an old shoe box, so here is a sample of my first London photos taken in either 1971 or 1972.

This photo was taken in Broadway, looking down Tothill Street towards Westminster Abbey, which can just be seen at the end of the street.

The large building on the right is the London Underground head office at 55 Broadway.

The following photo was taken on the bridge over the lake in St. James Park looking east towards the Government offices along Horse Guards Road.

The following photo is the hat shop of Lock & Co at 6 St. James’s Street.

It is some 48 years since I took the photo of Lock’s, however this is a trivial amount of time since the shop was first established at 6 St. James’s Street in 1765. The shop looks almost identical today.

The following photo was taken in Cheapside, at the junction with New Change. The church is Christchurch Greyfriars.

The view from within Cardinal Cap Alley, Bankside, looking across to St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The alley is gated now, but in the early 1970s, Bankside was an area to explore and had not seen any of the development that would so change this stretch of the river.

I took these photos around 48 years ago. I still have them as they were developed and printed out and these photos have been in a shoe box of photos for the last four decades. Digital photography has opened a whole new world in capability and volume of photos, however I do wonder how many of the amateur photos taken today will still be around in 50 years time.

I last used film for photography about 18 years ago, however one of my planned projects for the coming year is to get back into the use of film. This is my father’s Leica IIIG camera.

He purchased the camera body in 1957 so it is not the camera used for the majority of the early black & white photos I have published, however the lens is much earlier and was fitted to the Leica IIIc that my father used for his early photos.

I have had the camera serviced as the shutter was sticking, and I have brought some Ilford black & white film so I am ready for some film photography of London. I just need to learn how to use the camera and a separate hand held light meter to set up the correct exposure settings on the camera.

Hopefully later this year you will see some 2019 black & white film photos of London on the blog.

A Year Of Posts

I have been to some really interesting places during the year and discovered how much London has changed, but also in many places, they look much the same.

In December I wrote about the Angel. A brilliant pub on the south bank of the river in Rotherhithe. My father had photographed the pub from the foreshore of the river in 1951.

Sixty seven years later I was standing in the same position taking a photo of the same pub. The surroundings have changed dramatically, however the pub is much the same.

Like all London pubs, the Angel has had to adapt to survive and now serves a very different set of customers to when my father took the photo. By chance, from the same year there is a Daily Mirror article written in October 1951 by a journalist who was taken to various locations along the working river by a “merchant skipper”. One of these locations was the Angel, Rotherhithe. He writes of the experience:

“The Angel, Rotherhithe, where the skipper has to meet this mate of his is full of watermen when we arrive. One stocky waterman called Jim – a tough looking character with a grey stubble of a beard – is telling a story indignantly: “So I’m in my boat having a clean-up he is saying, w’en along comes this toff in a boat wearin’ a pair of flippin knickers and a flippen cap. ‘E is trainin some girls ‘ow to sail. Trainin’ em, Jim repeats darkly.

So ‘e comes smack-bang into my boat. O’ course, I could’t even talk to ‘im proper since there were ladies present. ‘get away from my boat, you unsophisticated chucker’ I shouts, ‘E looks up and says: ‘My man’ ‘e says, ‘do you know ‘oo I am?’

‘You might be flippen Joe Louis I says gettin’ really aggravated. But you don’t look like ‘im. An’ unless you push off from my boat this instant, I shall flippin’ well come down and knock your flippin’ ‘ead off – fancy cap an’ all.”

I am sure there was some journalistic embellishment, but an interesting tale from when the customers of the Angel were those who worked on the river and the surrounding warehouses and industries.

Last August we went to the Netherlands. We had lived there for 5 years from 1989 and wanted to revisit places and friends. My father had also cycled round the country in 1952 with some friends he had made during National Service, and as usual took his camera with him. I had not scanned these negatives when we lived in the country, so this was also an opportunity to visit the places he had photographed.

I am fascinated by how places can be connected. Cities do not stand in isolation. London has a road and rail network radiating out across the country and a river flows through the city. There are also networks of power, religion, monarchy and finance which have shaped the City and Country. Trading routes, flows of people from within the country and to and from the world have also established networks of connections.

There are also very unique points of connection. A single event that happened at a specific point in time, and I found one in a wooded suburb of the Hague, when I went to Wassenaar to find the launch location of the first V2 rocket to hit London.

And a week later on the anniversary of the launch, I went to the site in Chiswick where the rocket landed. At each location there is a small memorial pillar that records the date and the event.

Two places, 205 miles apart which will forever have a tragic connection.

The Oosterbeek War Cemetery was one of the many locations that my father visited in the Netherlands. He went to many of the locations associated with Operation Market Garden, the battle made famous in the book and film ‘A Bridge Too Far’. Not a surprising set of locations to visit given he had grown up during the war, had just finished National Service and these events were only 8 years previous.

The Oosterbeek War Cemetery really brings home the huge loss of life and the very young age of so many who died. The majority of those killed on the Allied side of the battle were British and Polish forces and I found a number of the graves that my father photographed in 1952 and for the blog post was able to find some of the stories behind those buried here.

The photos above and below show the temporary marker in 1952 and the permanent stone marker in 2018 on the grave of Mieczyslaw Blazejewicz. A rank of Starszy Strzelec (this seems to translate to a Senior Private or Lance Corporal) in the 3rd Parachute Battalion of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade. He was born on the 24th November 1920 at Lancut, a town in south eastern Poland.

He was killed whilst trying to cross the River Rhine to get to Oosterbeek on the 26th September 1944. As with many of those killed whilst trying the cross the river, his body would drift downstream and be later recovered from the river at Rhenen on the 9th October. He was 23, just two months short of his 24th birthday.

One of the posts I found personally most interesting was about the King Edward VII Memorial Park in Shadwell. I have walked along the river at the side of the park many times and occasionally through the park, but decided to explore the park in more detail.

I found a partially derelict pavilion and the flat grass of a bowling green, both of which had once been for the Shadwell Bowls Club.

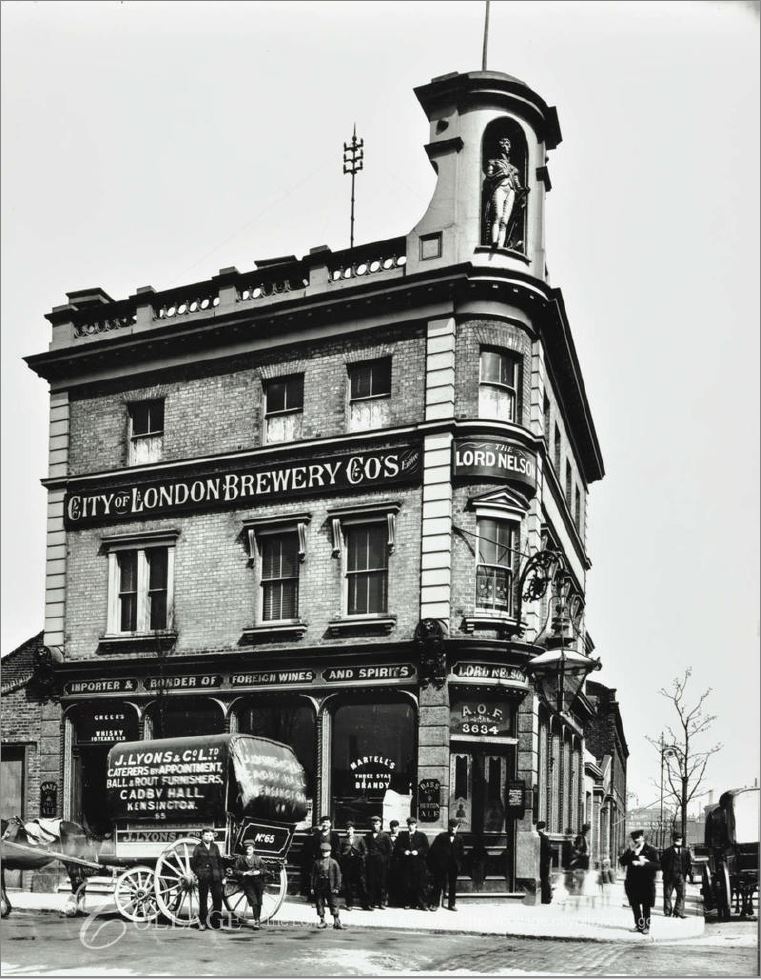

I was initially going to write about the park as I found it, but the more I researched, the more I found. A fascinating history of an area once crowded with streets, houses, pubs, industry, and a fish market that was a potential rival to Billingsgate.

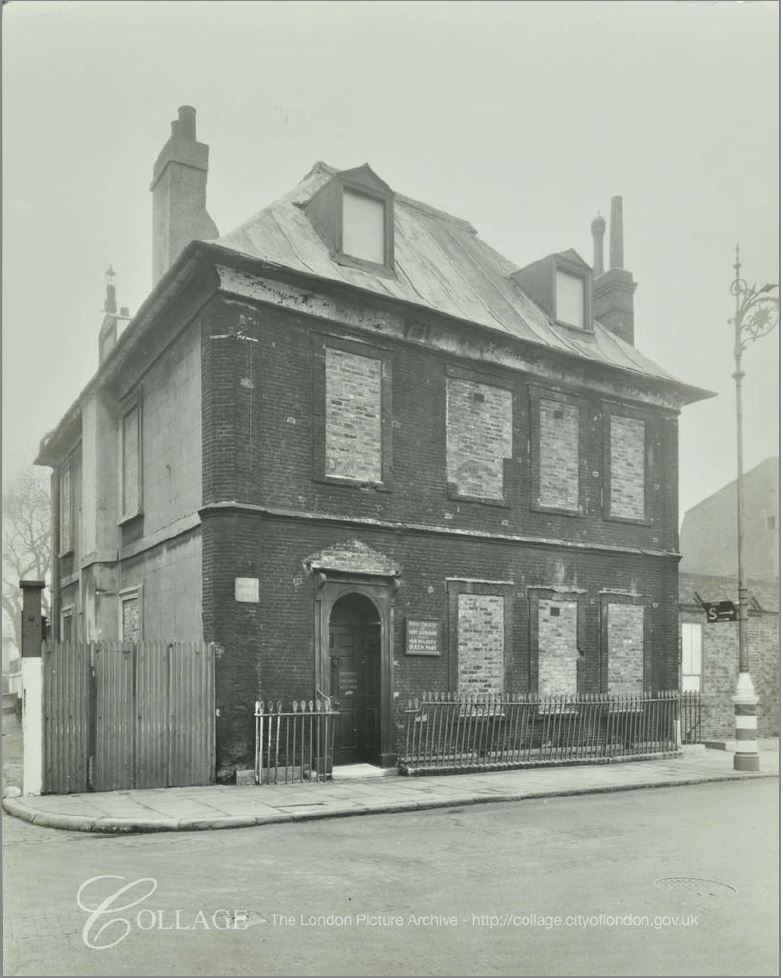

I also found a collection of photos on the London Metropolitan Archives, Collage site and was able to trace the locations of where the photos were taken.

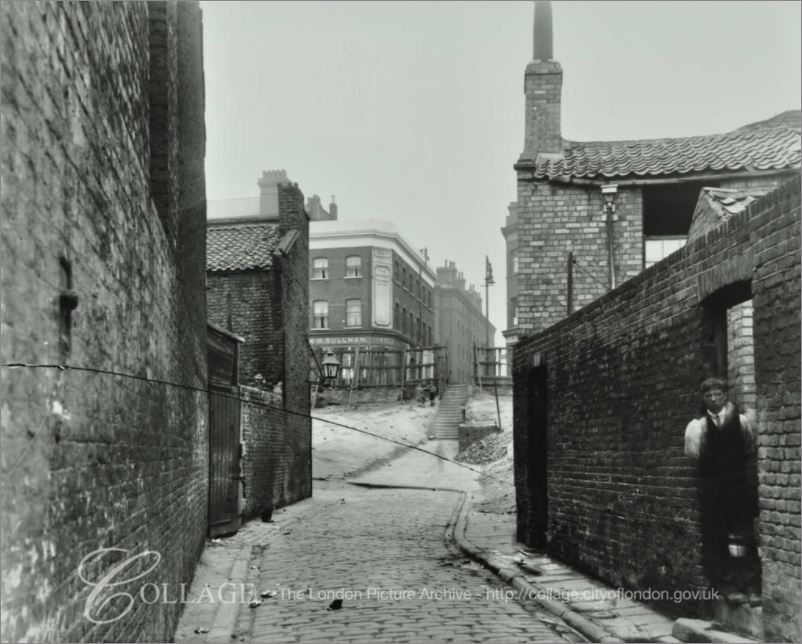

This photo is looking up towards the High Street (the Highway) along Broad Bridge. The building on the left is the Oil Works and residential houses are on the right. Note the steps leading up to the High Street, confirming that the height difference between the Highway and the main body of the park has always been a feature of the area, and is visible today with the terrace and steps leading down to the main body of the park.

Image credit: London Metropolitan Archives, City of London: catalogue ref: SC_PHL_01_381_A361.

Again, another way in which the ghosts of those who have lived and worked in London return, hidden within books, maps, photographs and the physical traces we can find when out walking.

To finish, can I again thank you for reading the blog, subscribing, following, commenting and e-mailing and putting up with my random travels around London and further afield.

I am now off to try to learn how to use a sixty year old film camera.