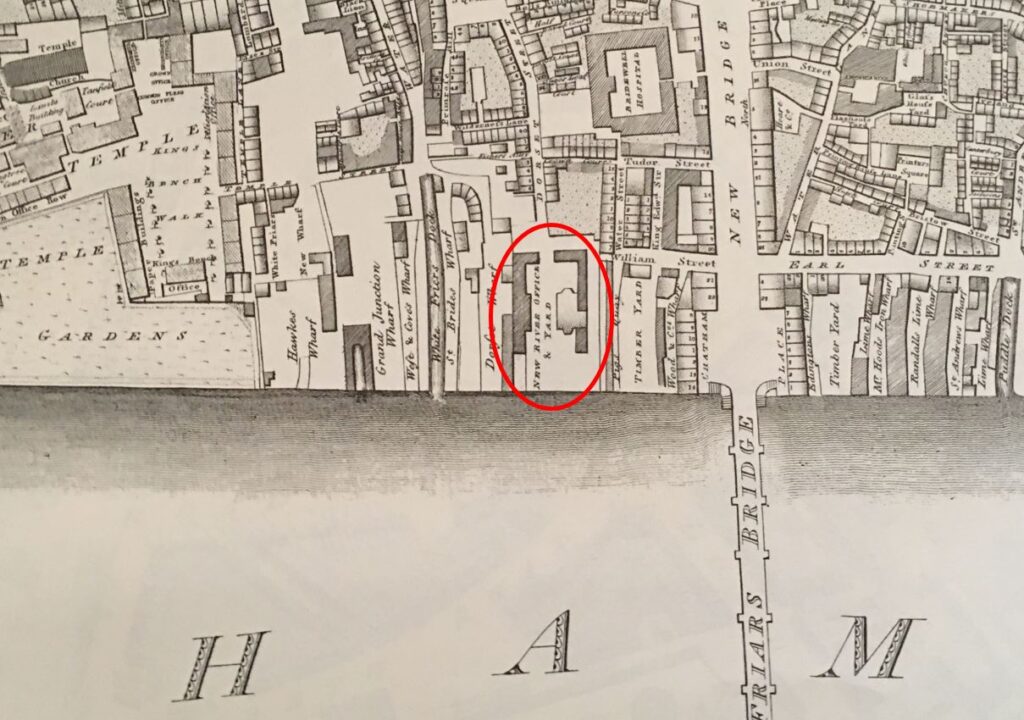

I have written about New River Head in a previous post, as well as a number of posts about how water has been key in the development of Clerkenwell and parts of Islington.

New River Head was the point where water delivered by the New River was collected and treated, then sent on through an extensive pipe network to London consumers from the east end to Soho and the west end.

The New River was built in the early 17th century, opening in 1613. A very innovative and complex bit of civil engineering for the time as it transported water from springs near Ware in Hertfordshire all the way to New River Head. Helping to transform London’s water supplies, that had depended on water from the Thames along with small local wells and springs, to a constant, high volume supply of clean water.

What is remarkable is that this 400 year old artificial river is still in use, and for the same purpose. Today, the New River provides around 8%, or 220 million litres a day, of London’s water, so if you live in London, there is a good chance that you have drank or showered in water that has reached you via the New River.

The New River no longer runs to New River Head. It terminates at the east and west reservoirs around Woodberry Wetlands, just south of the Seven Sisters Road.

Starting in 1992, Thames Water created a New River Walk that follows the 28 miles from the source to New River Head. 25 miles follow the river from source to the reservoirs, and a further 3 miles makes up a heritage walk that follows the original route of the New River through to New River Head.

I have long wanted to walk the route from the source of the New River, and a few weekends ago, had the opportunity to spend a weekend walking the New River with a small group from Clerkenwell and Islington Guides and the Quentin Blake Centre for Illustration, who will be moving into the historic buildings at New River Head.

My post on New River Head and London’s Water Industry covers the history of the New River, so I will not focus on this aspect in this post, however before starting the walk, a quick look at why a former army officer from Bath, Edmund Colthurst, who had served in Ireland, in 1602 proposed a scheme to bring in water from Hertfordshire springs to a site to the north of the city.

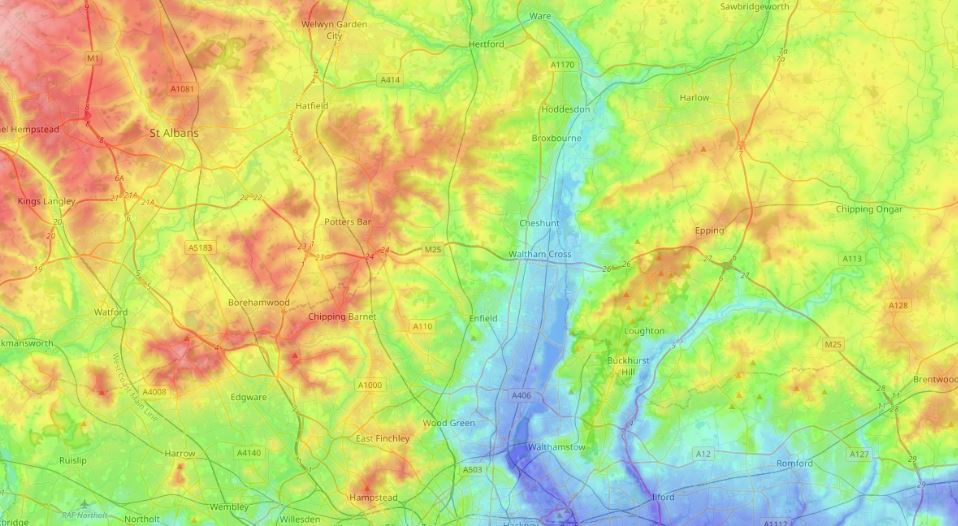

The following map is a heat map (from the excellent topographic-map.com) showing the height of the land around the town of Ware. Blue the lowest, through green, red and to the highest land shown as white:

I have circled the source of the New River. It is here where the New River draws water from the River Lee, and where the Chadwell Springs rise and feed the river. The Chadwell Springs were the original source, with the link to the River Lee added later when more water was required to support London’s growing population.

As can be seen in the map, the source is in a low lying area, there are multiple streams running through the area as well as the River Lee which follows the low lying land to the lower right of the map.

The surrounding land rises, and water collects in the area, providing a significant source for the river.

The Chadwell Spring is the original source of water for the New River. The spring is a large pool of water which is filled with water rising from below ground.

The geology of the area is interesting. Some of the water that rises at the spring comes from the Mimmshall Brook, which, ten miles to the west near Hatfield, drains into a sink hole.

The sink hole forms part of a large underground drainage network called a Karsitic network – an area where the underlying chalk has been dissolved by water forming sink holes and sub-surface drainage networks, which around Hertford and east to the Chadwell Springs covers an area of 32 square kilometers.

The geology of the area means that it was a perfect choice for Edmund Colthurst to propose for the source of the river in 1602.

I refer to the River Lee a number of times in the post. The name can be found with spellings of Lee and Lea. The River Lea is frequently used for the natural river and Lee Navigation for parts of the river where it has been turned into a navigable canal. For simplicity I will use River Lee to refer to any part of the Lee / Lea water system.

Now to start walking the route:

Day 1, Ware to Rye House

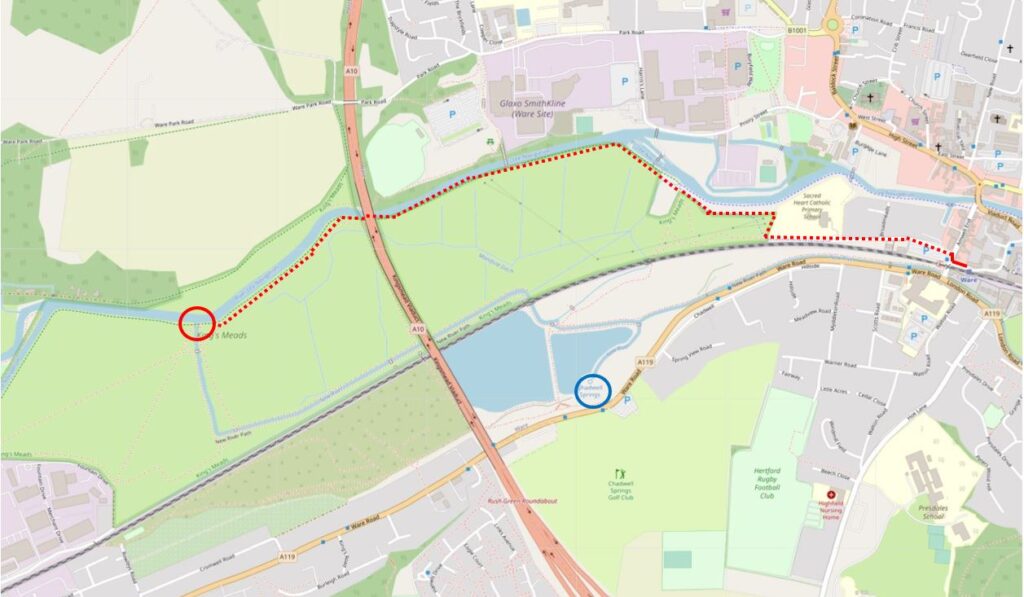

The first day’s walk was just under 8 miles in length, which included the walk to get to the source of the New River. The route is well served by the rail network, so starting from Ware station, it was a walk to the source following the dotted red line in the following map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

The blue circle in the above map marks the location of the Chadwell Spring.

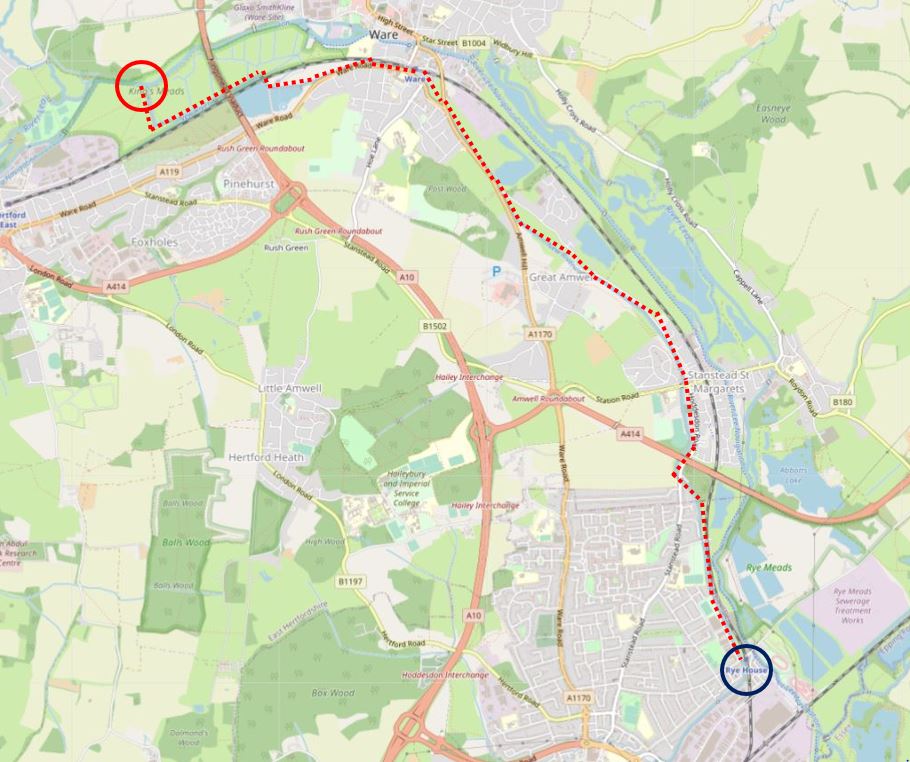

The first day’s walk from the source to Rye House is shown by the red dotted line n the following map:

After walking from Ware station, along the River Lee, the first sign of the New River comes with New Gauge House on the banks of the River Lee:

At the side of New Gauge House are two signs, the one on the left is part of the original signage covering the path alongside the river, the sign on the right shows that this is still a working bit of water supply infrastructure, with appropriate safety precautions.

Looking west along the River Lee, with New Gauge House on the left, and on the right in the river is the infrastructure that allows water to be drawn off from the Lee into the New River.

The following view shows New Gauge House, with the start of the New River coming from the arch below, where water from the River Lee starts its journey south to provide water for the population of London.

New Gauge House was built in 1856. The equipment that controls the flow from the Lee is in the ground floor of the building, and accommodation for a Gauge Keeper was in the floor above.

According to the Historic England listing, 22.5 million gallons is taken each day from the Lee into the New River.

Looking south along the start of the walk:

Looking back along the New River to New Gauge House, slightly hidden by trees, with the higher ground, part of the higher ground that surrounds the area, seen in the background.

As shown in the heat map at the start of the post, this is a low lying area, with large amounts of water lying across the surface of the land:

Signposting from the creation of the New River Path:

A straight stretch of the New River with the A10 road crossing:

Underneath the A10:

It is theoretically possible to get to the Chadwell Spring, however the area around the spring is very overgrown and wet, and required a detour from the main path. The Chadwell Spring rises into a circular pool.

This is the view looking in the direction of Chadwell Spring from the walk alongside the New River:

This is the White House Sluice. The building originally contained the equipment to control water levels on the river:

The most historic building here though is the Marble Gauge photographed below:

The Marble Gauge was built in 1770 to control the water taken from a former inlet to the River Lee. Today, the Marble Gauge does not have any function, and water flows through a couple of iron pipes to bypass the structure.

The Marble Gauge was designed by Robert Mylne, the architect and engineer to the New River Company. The structure, along with the railings shown to the left of the above photo are both Grade II listed.

“This Belongs To New River Company” – stone in the undergrowth to the side of the river:

When completed in 1613, the Chadwell Spring was the furthest north of the sources feeding the New River. The connection to the River Lee would not come until Parliament approved a 1738 Statute that allowed the company to take up to 102 megalitres a day from the River Lee (a significant additional source compared to the original 10 megalitres a day from the Chadwell and Amwell Springs).

Whilst the River Lee provided a considerable additional supply of water for London, it did not please barge and mill owners who were concerned about the impact that such a loss of water would have on their use of the Lee.

The photo below shows the channel from the Chadwell Spring where it joins the New River:

A significant additional source of water was added to the New River during each of the river’s first three centuries.

During the 17th century, the springs at Chadwell and Amwell provided the water. In the 18th century, water from the River Lee was added, and in the 19th century a number of pumping stations were built along the northernmost stretch of the New River. These pumping stations extracted water from bore holes to add to the river.

The first of these is the Broadmead Pumping Station, built in 1881:

Whilst many of the pumping stations are still in use, Broadmead seems to have been converted to offices, and is currently the offices of a car hire company. The building and adjacent chimney are Grade II listed.

The New River then passes through Ware, just to the south of the station, and continues on parallel to the A1170 London Road:

In the above photo, there is a concrete wall projecting out into the centre of the river. A small figure can be seen at the end of the wall:

The figure is part of the Chadwell Way Sculpture Trail, which consists of 31 small bronze sculptures made by a class of 7 and 8 year old children from St John the Baptist Primary School in Great Amwell.

The above sculpture is called “Murphy and his Dog”, by James. The leaflet detailing the trail can be found here.

The river soon moves away from the London Road, and we reach the village of Amwell, where the Amwell Spring adds water to the river. To mark the location, there is a small island in the river:

The monument in the above view has the following inscription:

An appropriate inscription to think about whenever we turn on the tap.

Walking past the island, and at the opposite end is another monument, with a Latin inscription facing the path:

And the following inscription on the other side of the monument:

A short distance along the New River is Amwell Marsh Pumping Station, a Grade II listed building, completed in 1883:

The British Geological Survey have the bore hole record for the boreholes under the pumping station. The record dates from 1899 and details two boreholes 5.25 feet diameter at the top, reducing to 4 feet diameter at the bottom of the boreholes, which are 109 feet deep.

The combined boreholes had a total pumping capacity of just over 7 million gallons in 24 hours, and that when pumping stopped, water rises quickly within the boreholes.

A note in the record shows that the water pumped from below ground is part of a much larger underground water system as the record states “Pumping here affects Amwell springs, Amwell Hill Well and Chadwell spring”, so whilst water can be pumped from the boreholes, the total impact on the water system needs to be considered.

Amwell Marsh pumping station is still extracting water. The steam pumping engine has been replaced with electric, and looking into the New River we can see the turbulence created by water being pumped into the river:

A Metropolitan Water Board sign warning that fishing is strictly prohibited, trespassers and persons throwing stones will be prosecuted, and that any person bathing, washing an animal, or otherwise fouling the water is liable to a penalty of five pounds:

Not sure of the age of the sign. The Metropolitan Water Board was formed in 1903 when it took over the New River Company. The notice is signed by A.B. Pilling, Clerk of the Board. Pilling was authoring books about the new Chingford reservoir in 1913, so the sign must date from the early decades of the 20th century.

A quiet stretch of the New River:

Rye Common Pumping Station, another Grade II listed building, constructed in 1882.

As with the other 19th century pumping station on the route, it was originally steam powered, but was converted to electricity in 1935. As can be seen from the water gushing from the pipe into the river, Rye Common is still contributing to the New River and London’s water supplies.

The New River, running alongside a housing estate:

The New River is now approaching Rye House, with the three chimneys of Rye House Power Station in the distance.

And at Rye House, the first day of walking the New River ended, with the conveniently located Rye House station a very short walk from the river.

Day 2, Rye House to Cheshunt

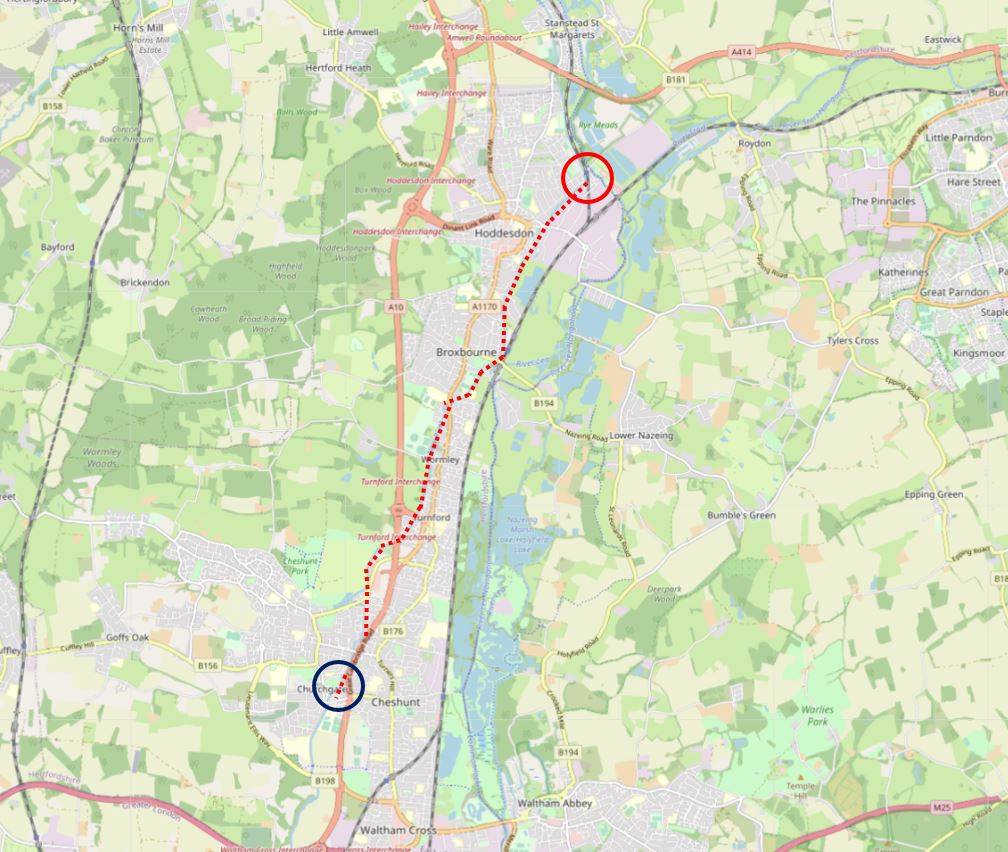

Day 2 of walking the New River, a stretch that will take us from where we finished yesterday at Rye House, along the route of the New River to Cheshunt – the route highlighted by red dashes in the following map (Map © OpenStreetMap contributors):

An overcast and grey Saturday was followed by a sunny Sunday. Not long after leaving Rye House, the route reached Essex Road Pumping Station (difficult to photograph, just a very small part of the brick wall is on the right of the following photo), with new building on an old industrial site in the background.

Two large pipes from Essex Road Pumping Station discharging water into the New River:

Essex Road Pumping Station draws water from a borehole beneath the building. The borehole consists of an upper shaft of depth 54 feet and average diameter of 7 feet, followed by a bore hole which extends to a depth of 403 feet below the surface.

The bore hole record demonstrates that there is a considerable volume of water not that far below ground. In 1920, water would rise to a level 2 feet below the surface, and without pumping, this standing water level does not vary.

The record stated that the bore hole would yield 2,160,000 gallons of water a day.

A short distance after Essex Road Pumping Station is a new road bridge that carries Essex Road over the New River:

The walkway alongside the New River carries on under the bridge, with some appropriate artwork lining the under side of the bridge:

After passing through some housing and industry around Rye House, the New River regains its rural setting, with views helped by the sunny weather after the previous day’s rather grey walk:

It is rather hypnotic watching the flow of the water in the river. Leafs and twigs are carried along at the equivalent of a fast walk. The only turbulence at the occasional sluice and where pumping stations add water to the flow.

To the west of this stretch of the New River are some rather nice houses that make the most of having the New River passing the end of their gardens:

Before returning to a tree lined river:

We then come to the 1887, Grade II listed, Broxbourne Pumping Station:

This is a pumping station that is still in use, extracting water from deep below the surface and adding to the New River. Some turbulance can be seen at the right edge of the photo where water is pouring into the river. There are two other pipes pointing onto the river which must have been used in the past, as this was a pumping station that produced a considerable quantity of water.

The bore hole records for the Broxbourne Pumping Station state that there is a shaft below the building to a depth of 197 feet. It is a large shaft of 14 feet diameter at the top down to 10 feet diamter at the bottom. The bore hole record implies that there are additional bores heading out from the shaft.

The 1909 record states that the standing level of water is only 8 feet below the surface, again indicating how high the water table is along the route of the New River. The 1909 record stated: “Great quantity of water, the temporary pumps being drowned in sinking when 2 to 3 million gallons a day were got out. The yield has been returned as 4,500,000 gallons a day”.

There was a chimney at the pumping station which has been demolished, as along with the other pumping stations along the New River, it was converted from steam to electric. There is though a considerable amount of infrastructure to the side of the building. No idea whether this is still in use, however (if you like that sort of thing, which I do), there are some wonderful green painted tanks to the side. The Historic England listing makes no mention of these, only referring to the building.

It is not just the pumping stations that are listed along the route of the New River, also one of the train stations. This is the rather wonderful Grade II listed Broxbourne Station, built between 1959 and 1961 by the British Railways Eastern Region Architect’s Department:

Broxbourne Station is next to the New River. In the above photo, the New River embankment is the grass seen at the lower left corner.

Whilst this is the closest station to the New River, stations are not that far away for the majority of the walk, and the rail line is here for the same reason as the New River.

The New River needed to follow a route that was almost flat, with a very shallow drop in height from the springs to New River Head. This would ensure a smooth flow of water without any need for pumps.

The valley created by the River Lee and associated water systems had created a relatively low and flat wide channel of land between higher ground on either side.

This enabled the New River to follow the 100 foot contour (height above sea level) almost from source to destination, and the height of the river dropped by only around 20 feet along the entire route. Given the surveying methods and equipment of the early 17th century, it was a remarkable achievement.

This relatively flat land was also ideal for the rail network, which avoided the need to construct tunnels or large embanked routes for the railway, so the New River and railway ended almost parallel to each other.

The following map from topographic-map.com shows the lower land as the blue in the centre, with Walthamstow towards the bottom of the map and Ware at the top. The New River follows the light blue along the left of the blue of the Lee Valley.

Continuing along the New River into Broxbourne, and the river runs around the church of St Augustine’s.

As the New River Path gets into more built up areas, there are now sections where it is not possible to walk alongside the river. Fortunately these are for short lengths, and a quick diversion is needed to get back to the river.

The following photo shows one such section where the river runs through private gardens, A 1926 road bridge crosses the river.

In the following photo, the Mylne Viaduct (part of which is the low wall to the left) carries the New River over the Turnford Brook which runs below the New River, left to right.

The New River has been straightened in places from the original early 17th century route. I have not yet had the time to compare the route today with the original, however I suspect the view in the above photo is of one of the later, straightened sections.

The river is carried on a high earth embankment, which may have been too difficult for the original entirely manual construction method, but easier with later mechanical earth moving.

The New River then passes under the A10. The walkway has a slight diversion through a pedestrian tunnel under the road.

The New River then returns to a rather rural environment, with a large bush growing over half the river. Not sure how much maintenance of the New River is needed today, or is carried out by Thames Water to keep the course of the river open.

Although the New River passes through a number of built areas on the way to Cheshunt, it continues with a rather rural appearance with trees lining the banks. Small foot bridges ensure crossing points as the river winds through communities.

Sluice to manage water levels on the outskirts of Cheshunt:

Passing alongside a new housing estate:

The creation of the New River Path dates back to the early 1990s, and the path continues to be well sign posted with only a few places where some careful reference to the map is needed. This may well change as we get into the built areas of north London.

At the end of Day 2 – an autumn scene in Cheshunt:

From here it was a walk into Cheshunt to return home. The end of a brilliant weekend walking the New River.

Each day was just under 8 miles (which included getting to and from each day’s starting and end point). The early stages of the walk around Ware were wet and muddy in places, after Ware the path was mainly dry and easy to walk.

My thanks to those also on the walk for making it such an enjoyable weekend. We have a second weekend booked in a few weeks time, with an aim of walking from Cheshunt to where the New River currently terminates at the East and West Reservoirs, just south of the Seven Sisters Road.

The next stage will include the symbolic crossing of the M25, where rather surprisingly the New River crosses over, rather than under the M25.