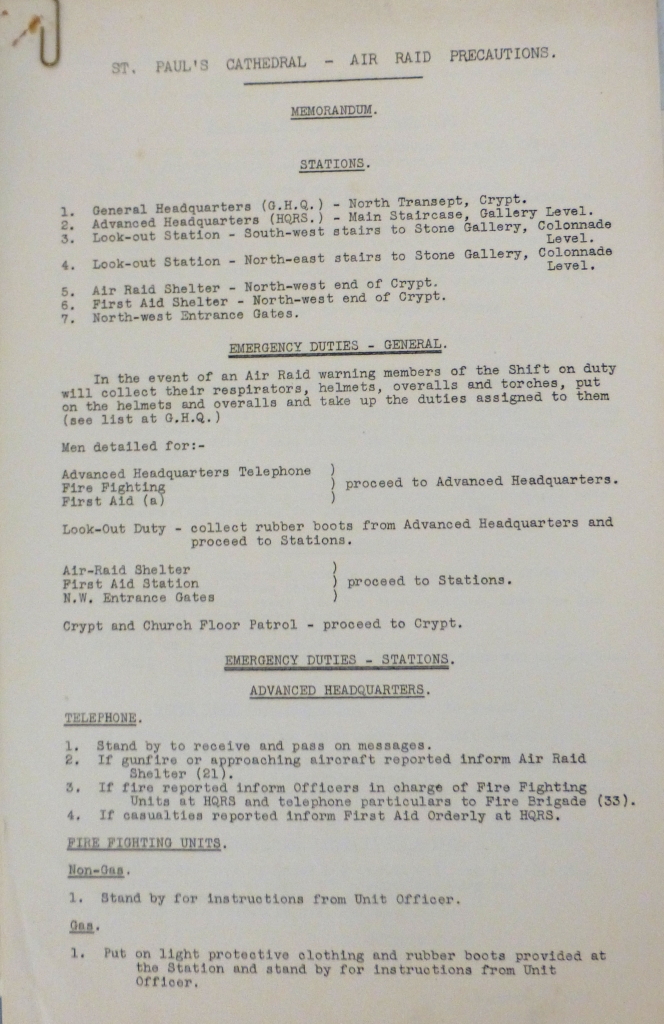

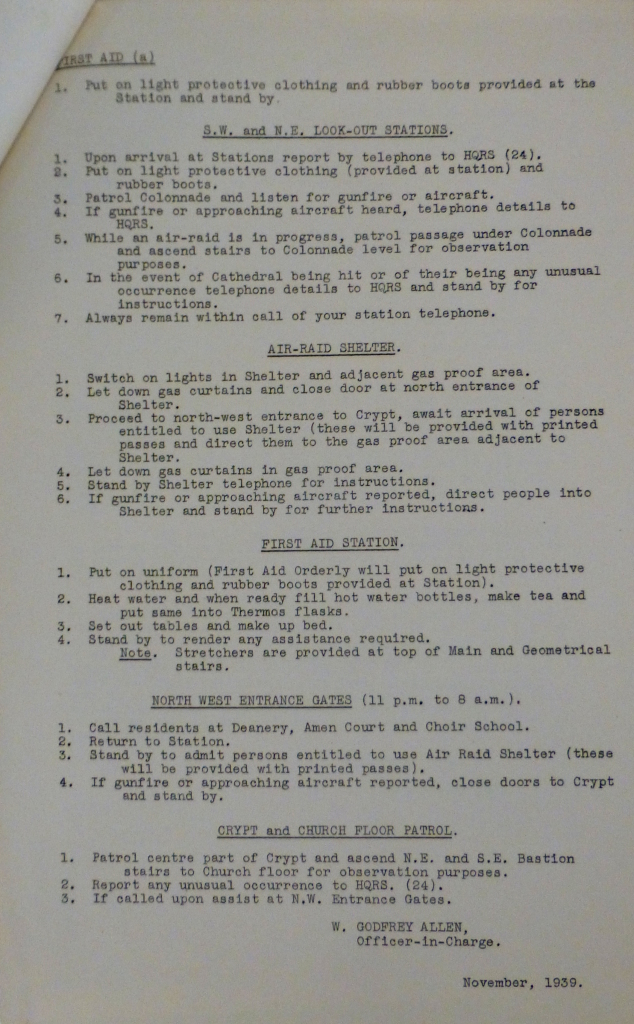

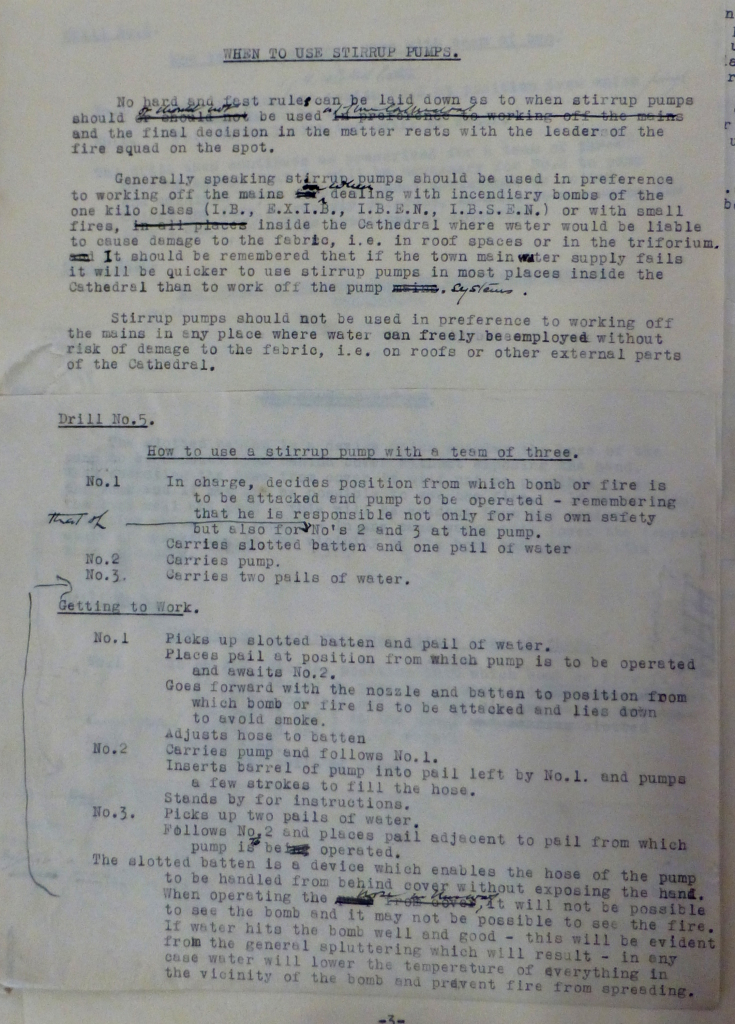

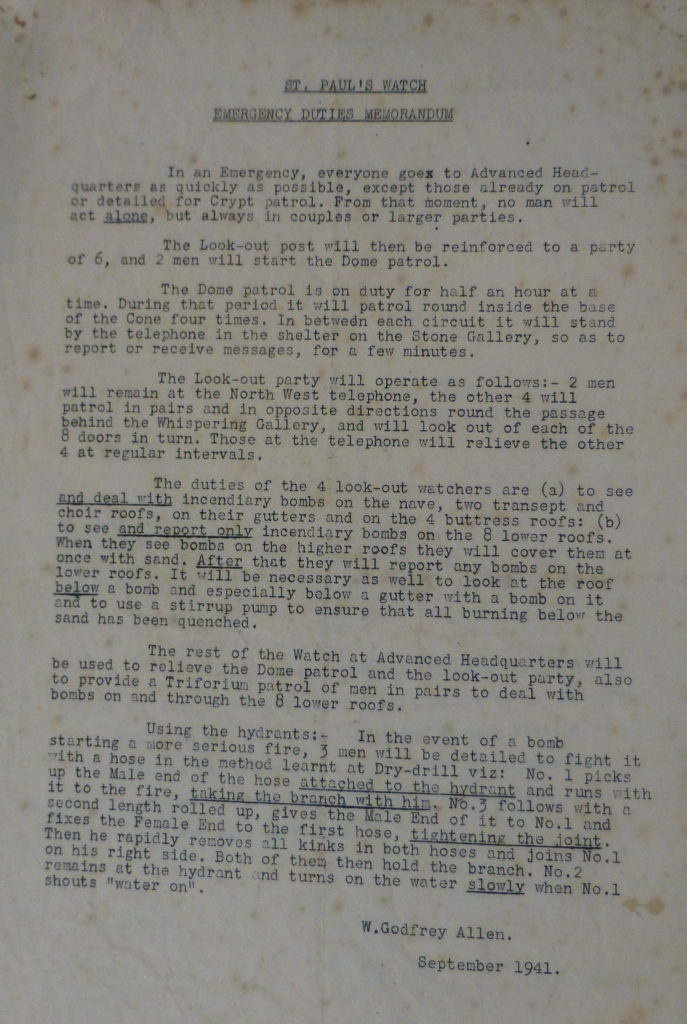

In yesterday’s post I introduced the St. Paul’s Watch. In today’s post I will focus on the night of the 29th December 1940. Although there had been many bombing raids on London since mid 1940, the first raid where the survival of St. Paul’s Cathedral was at risk and where the Watch were tested in the extreme was on Sunday 29th December 1940.

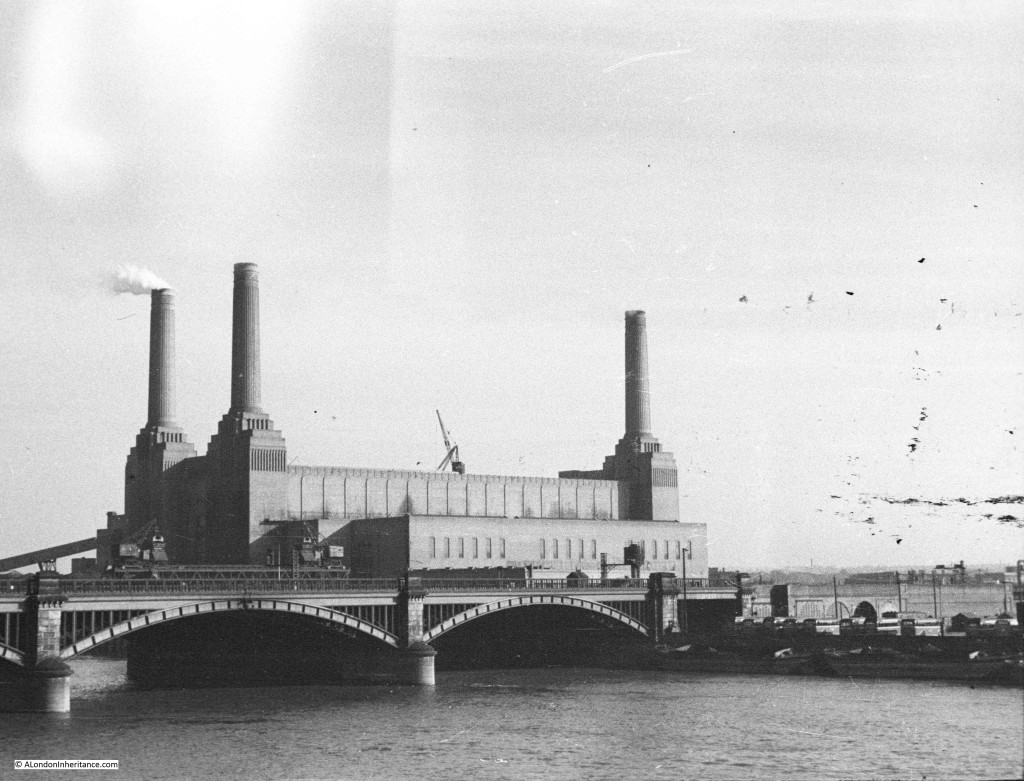

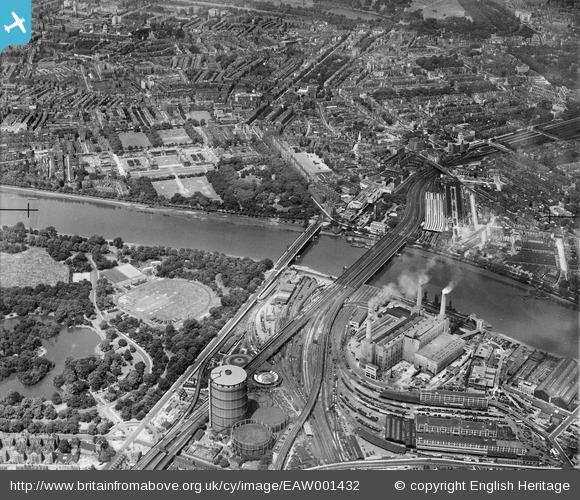

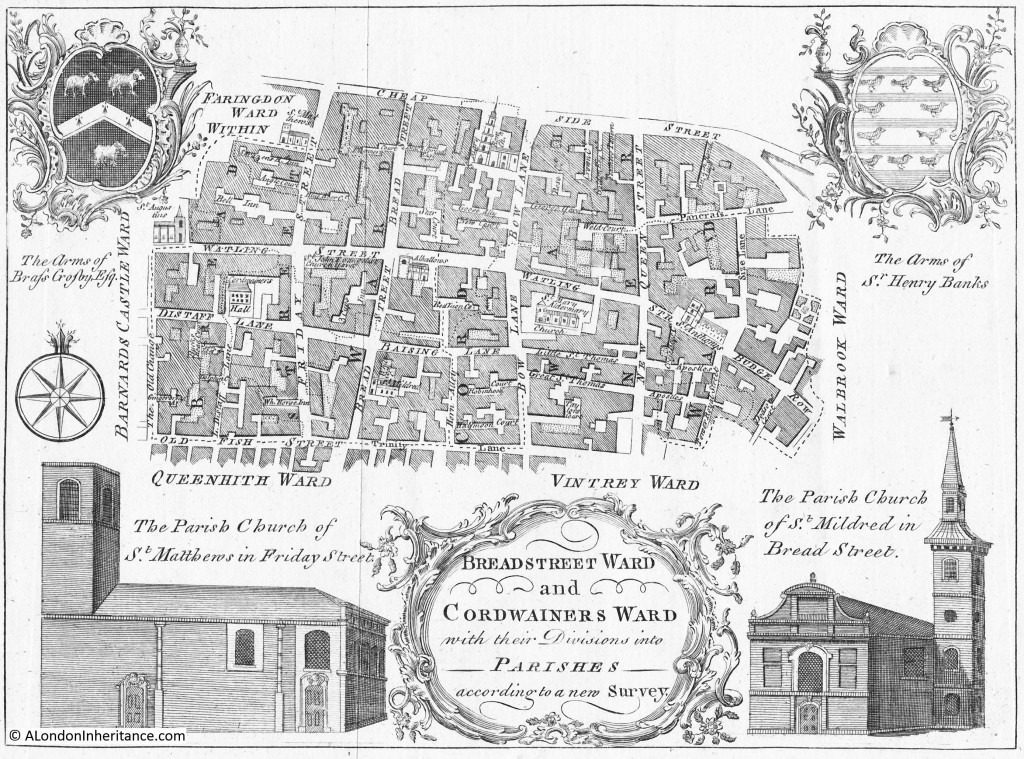

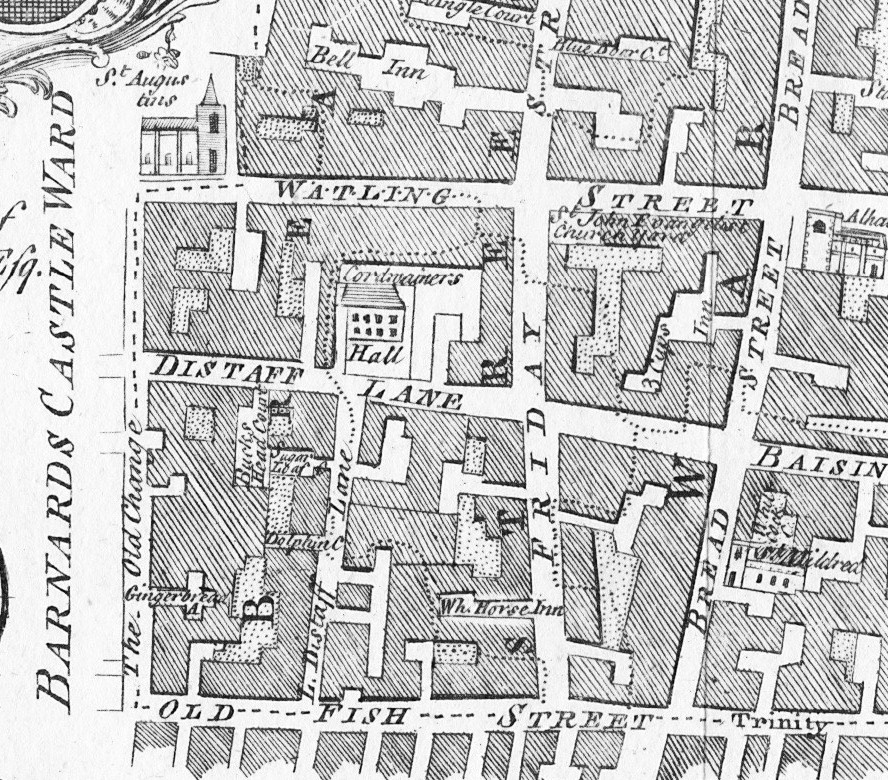

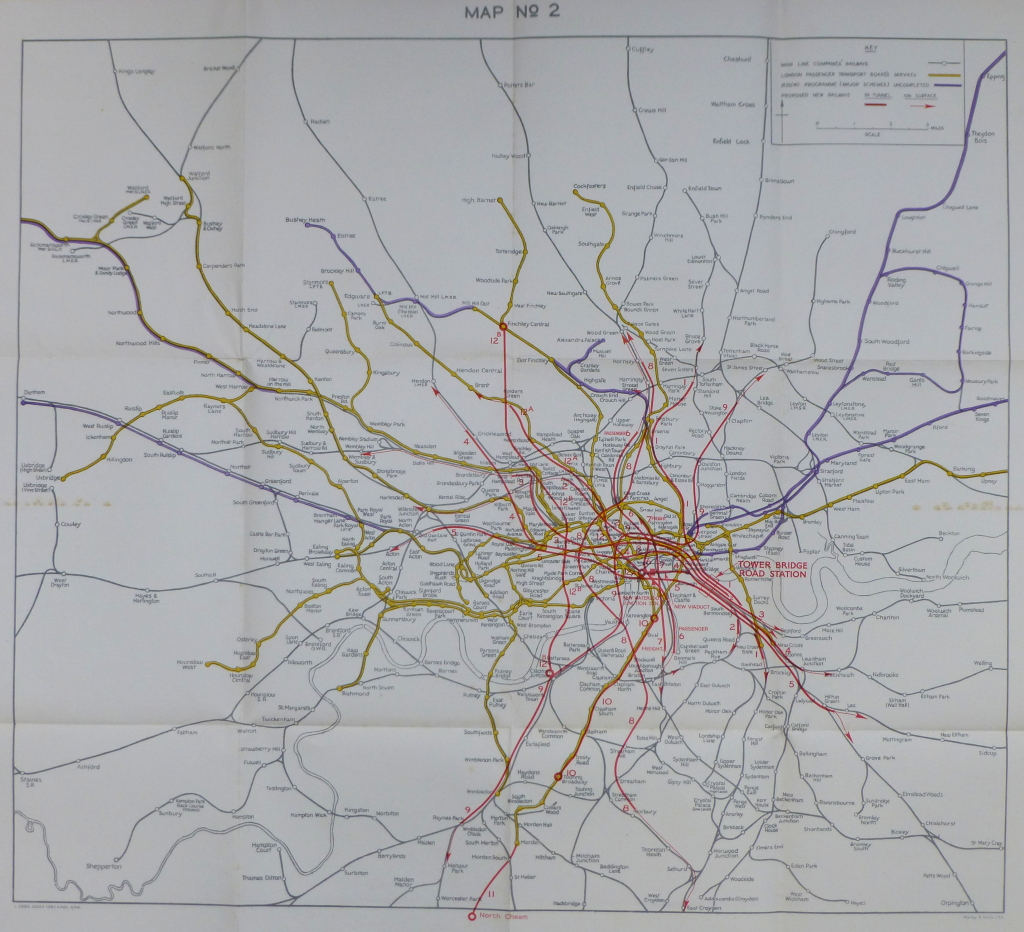

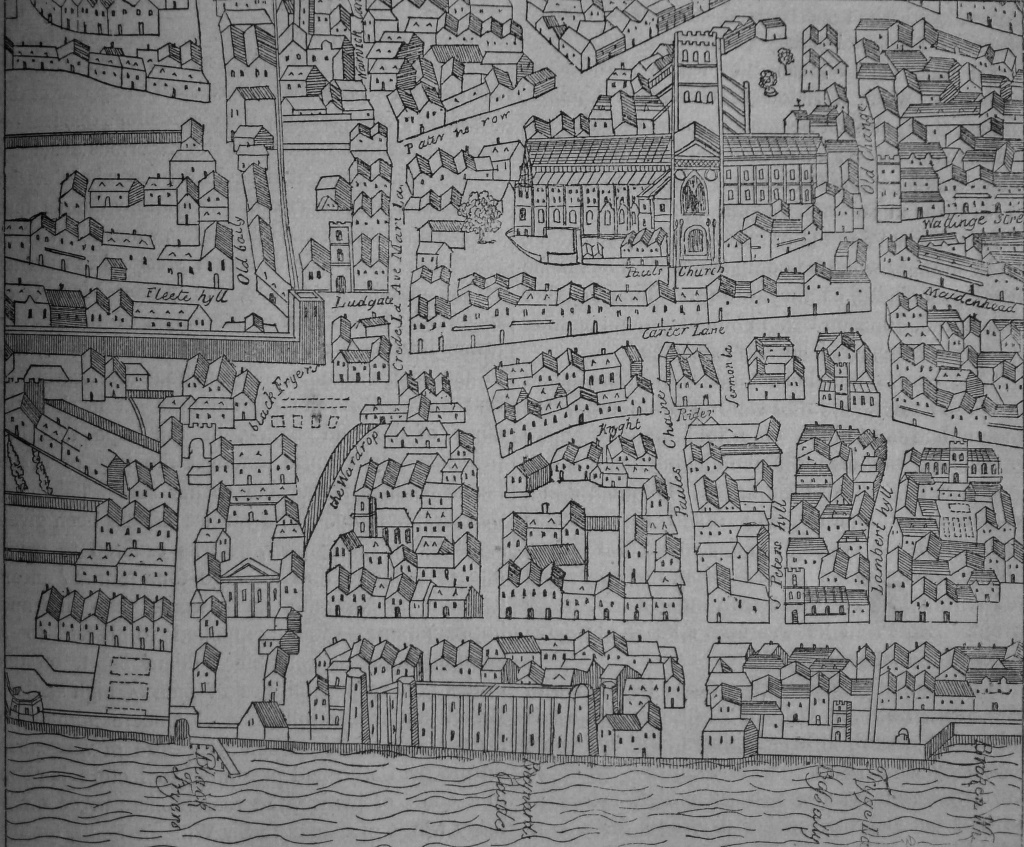

Before getting into detail, an overview of the area around St. Paul’s Cathedral will help set the scene. The following photo shows St. Paul’s and immediate surroundings just before the war. The Cathedral was surrounded on all sides by narrow city streets, closely packed buildings typically of up to six floors in height. St. Paul’s Cathedral was still the dominant building standing high above the surroundings.

To the north was Paternoster Square and Paternoster Row. Historic streets that were one of the centres of the publishing industry with many thousands of books stored in these buildings.

To the north-west is the tower of Christchurch Greyfriars, to the north-east is the tower of St. Verdast alias Foster on Foster Lane and immediately to the south-east of the Cathedral is the square tower of St. Augustine, Watling Street.

To the south, the land dropped down to the River Thames with the extensive warehousing that was still a feature of the City river banks.

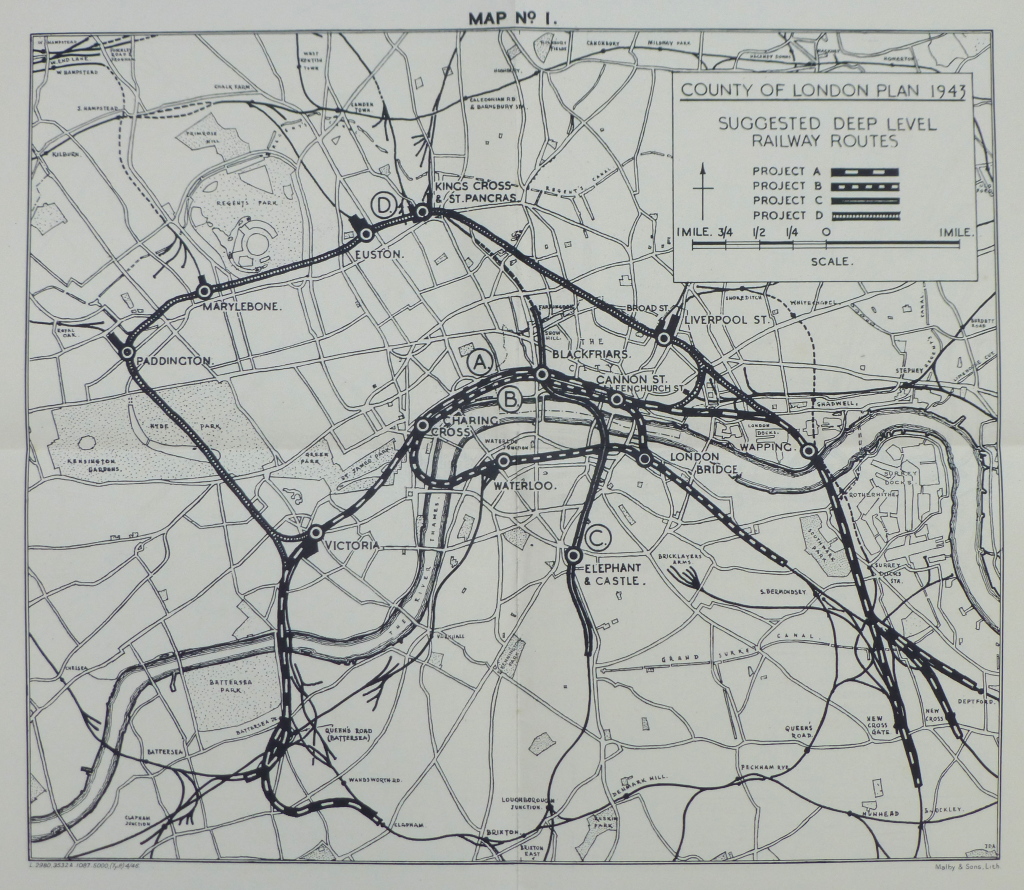

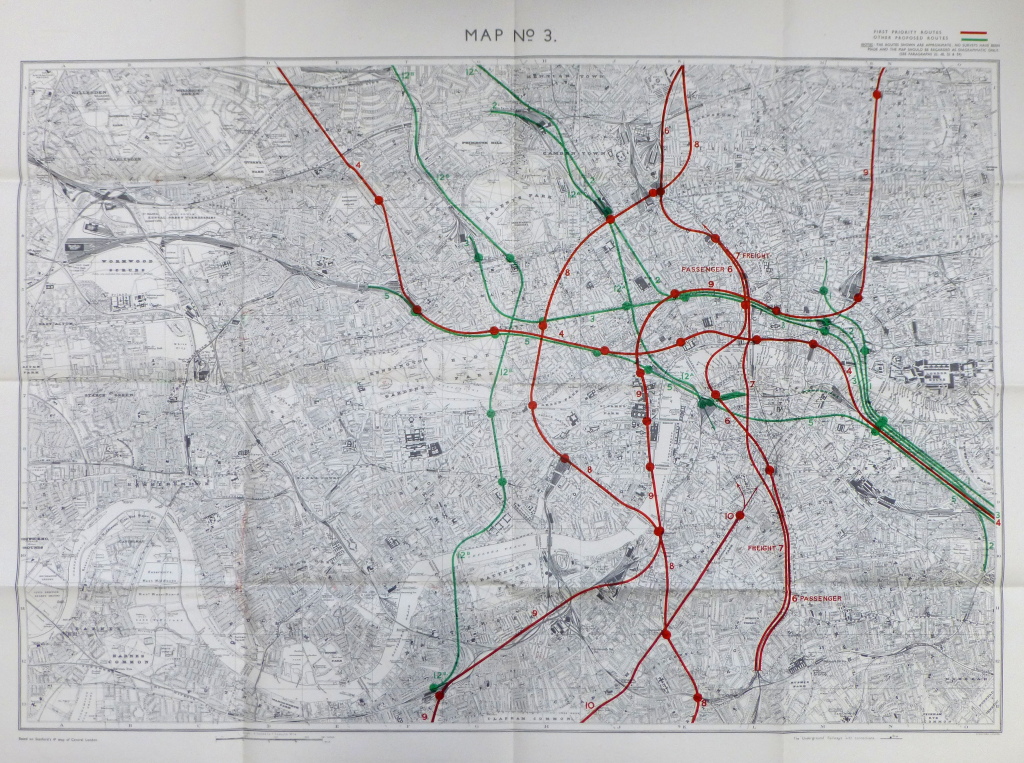

The German raid planned for the night of the 29th December was to feature an initial attack led by a specialist Pathfinder Squadron, followed by the first wave of bombers with mainly incendiary bombs and some high explosive to set the City alight, followed much later in the evening by the second wave of bombers with high explosive bombs. The clear intention was to destroy the City with key strategic targets being the bridges over the river, train stations and tracks and communications centres such as the Faraday building on Queen Victoria Street which was a centre for the London Telephony system and also for international telephony circuits.

The role of the Pathfinder squadron was to locate the target using a beam radio system where radio signals transmitted from the Continent would direct a plane to its target with a change in signal where beams crossed indicating a key geographic point to commence the attack.

The planes of the Pathfinder Squadron flew over the countryside between the coast and south London and on approaching Mitcham the signal changed indicating the point from where a carefully planned course and time would lead the planes directly to the centre of London.

This approach allowed for accurate bombing despite the heavy layers of cloud below. The aim of the Pathfinders was to start fires which the main bomber force could then follow.

At the planned time the bombers released canisters containing the incendiary bombs. On the drop down, the canisters then broke open to shower individual bombs over a wide radius.

The waves of the main bomber force then started to arrive, each loaded with canisters of incendiary bombs and the occasional high explosive bomb.

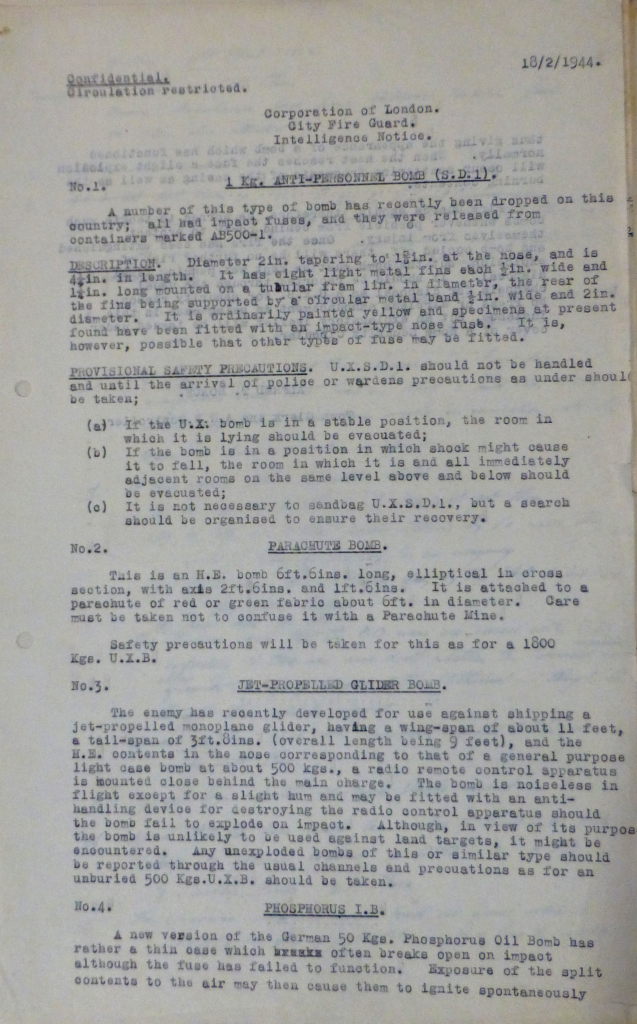

The following photo from the IWM collection (© IWM (MUN 3291)) show the 1KG incendiary Bomb that was dropped in such large numbers on the night of the 29th December.

These were relatively small devices and could be easy to deal with, however when dropped in such large numbers, it only took a few to start fires in hard to reach locations that could very quickly get out of control.

The 1KG incendiary was 34.5cm long and 5cm in diameter. The body was of magnesium alloy with a filling of an incendiary compound (thermite). On hitting the ground, a needle was driven into a percussion cap which ignited the thermite. The heat from this also ignited the magnesium casing causing an intense heat which would ignite any flammable material that the bomb was in contact with.

For the St. Paul’s Watch, the first indication of the danger to the Cathedral came soon after 6pm when they heard a sound described as “a scuttle full of coals being spilled on the floor” which was the sound of incendiary bombs landing all around the Cathedral.

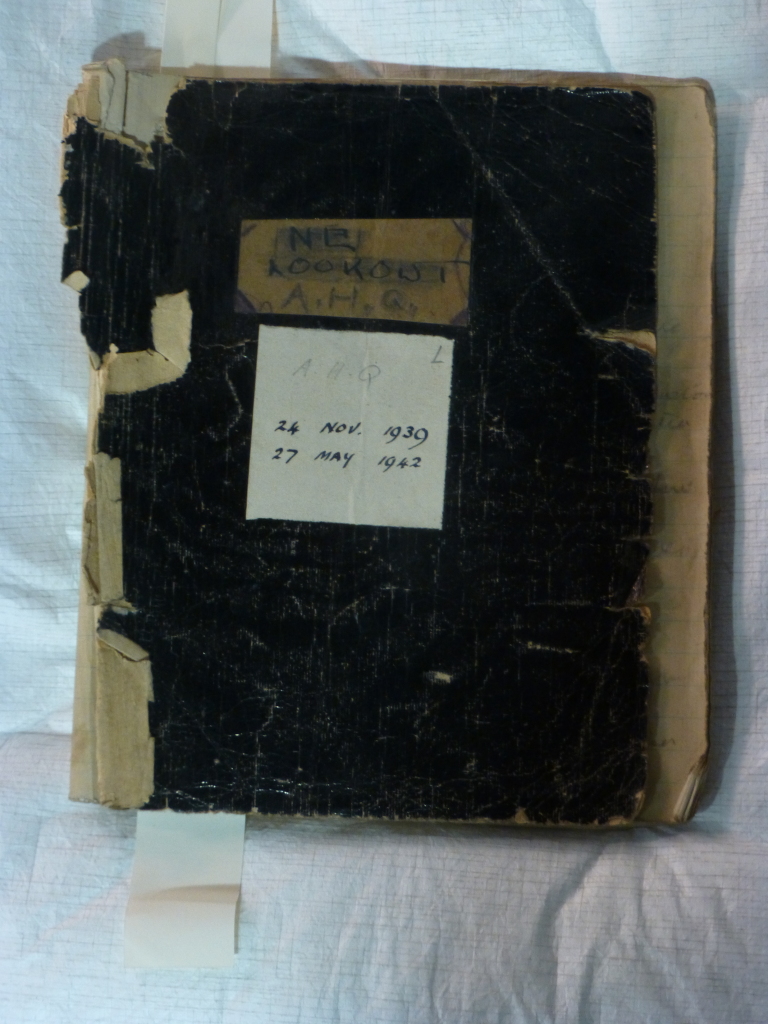

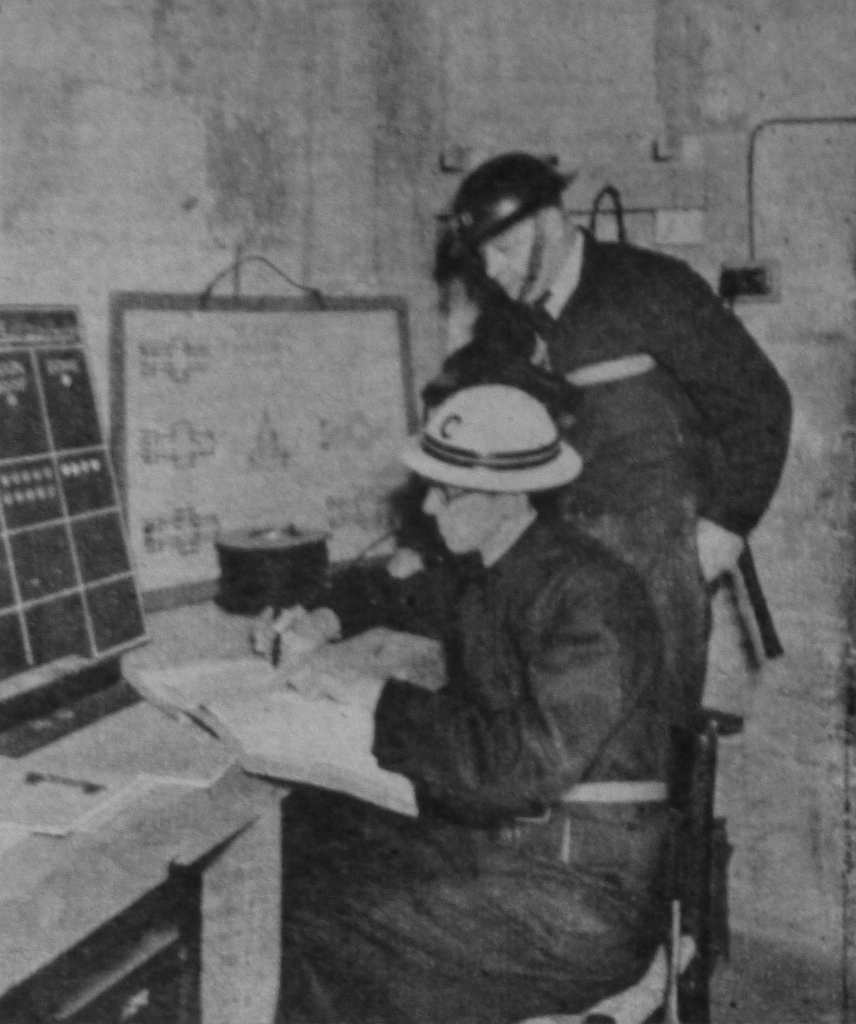

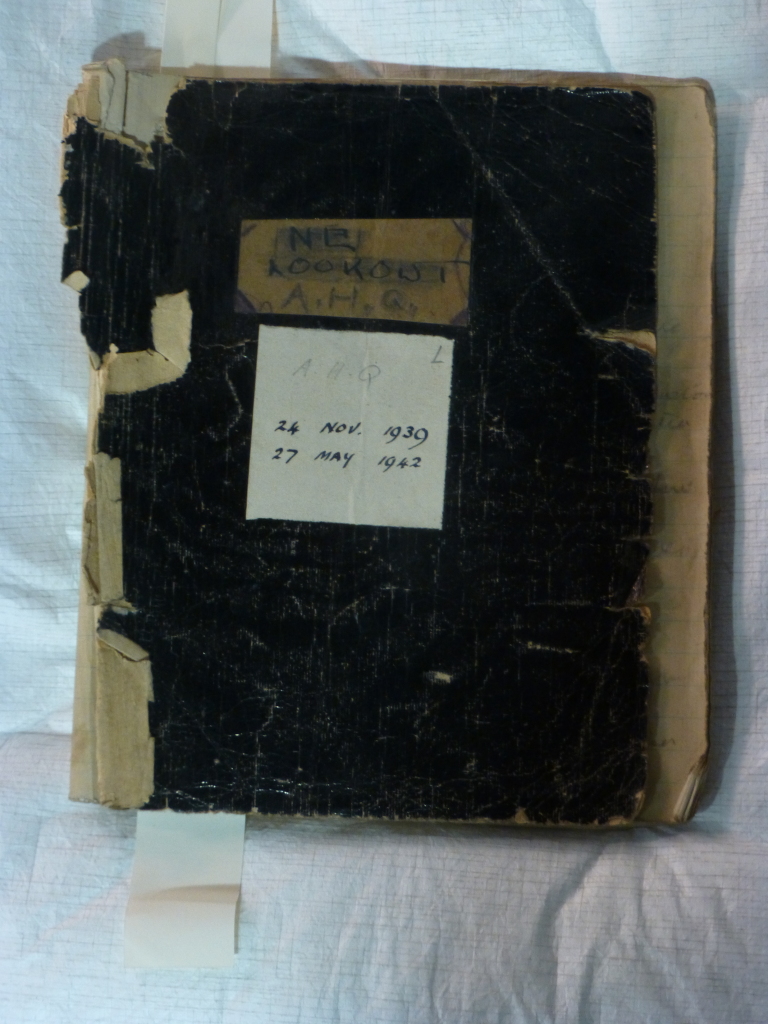

In the crypt headquarters for the Watch, a log was kept throughout the war recording individual events as they happened. Incidents being recorded in a very “matter of fact” way, logging the time and the incident.

The log is still held in the St. Paul’s Archives, the delicate state reflecting the years and conditions of use through the war. I took the following photo of the log covering the 29th December 1940, now in such a delicate state that it needs to be treated almost like a medieval manuscript.

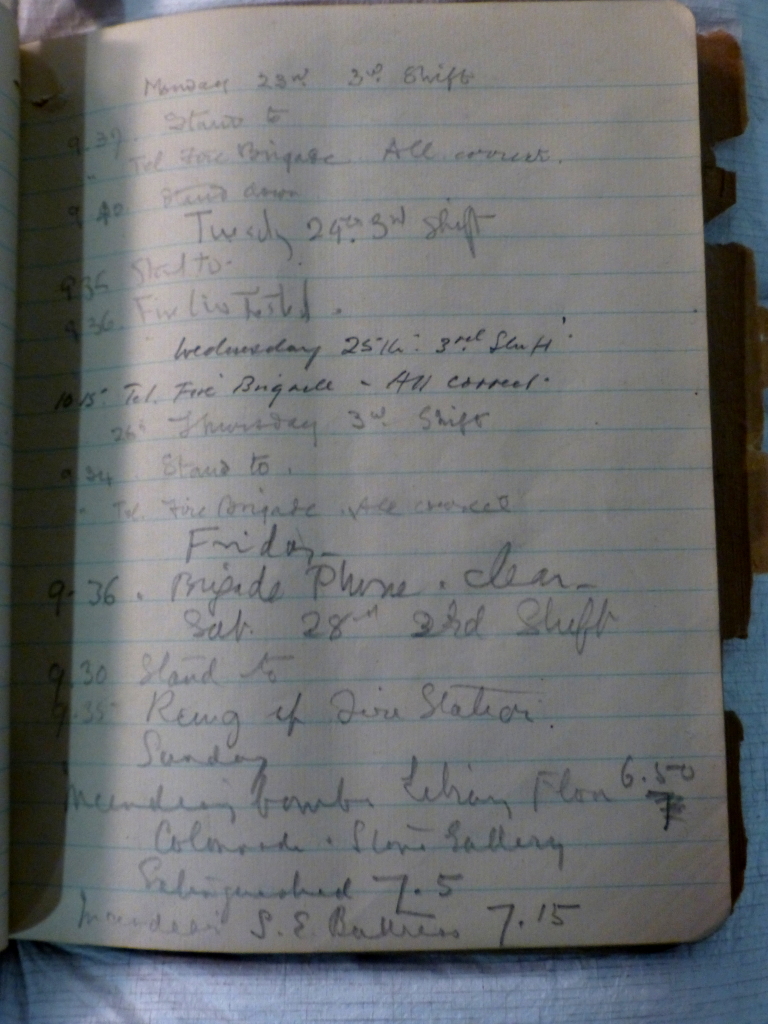

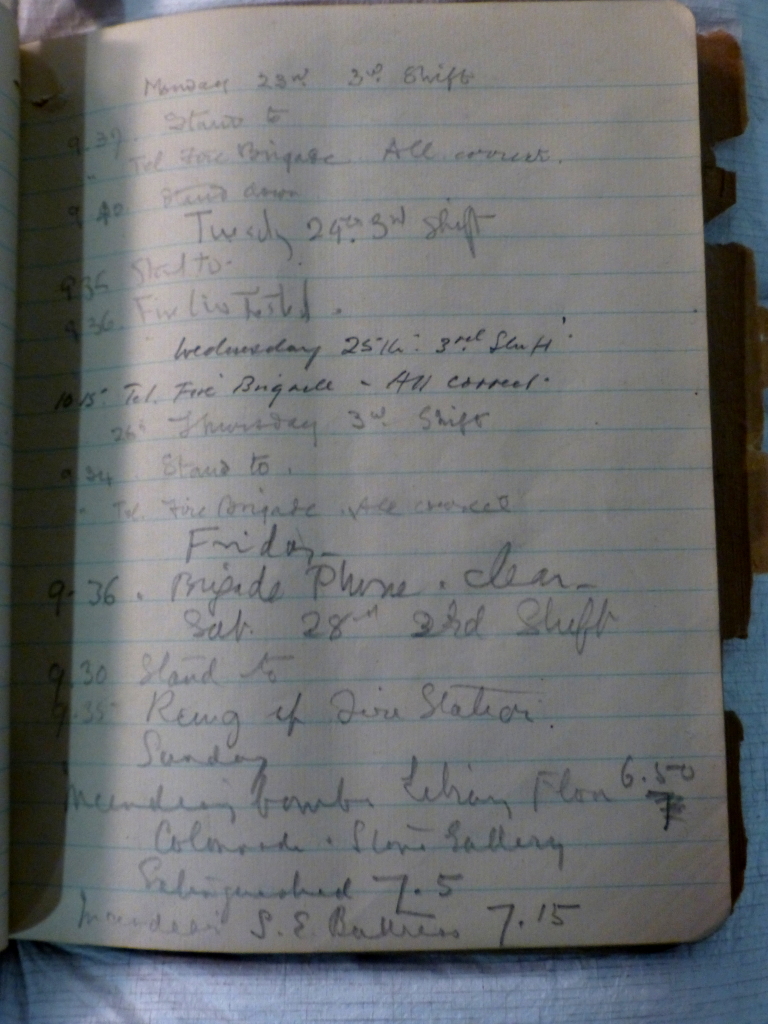

The two pages covering the 29th December 1940 are shown below:

The first page shows a quiet run up to Sunday the 29th, the routine call to the Fire Station the main recorded event.

Towards the bottom of the page, the events of Sunday the 29th start to be recorded (I have tried to interpret the text in the log, any errors are mine):

- Incendiary bombs Library Floor 6.50

- Colonnade Stone Gallery

- Extinguished 7.5

- Incendiary S.E. Buttress 7.15

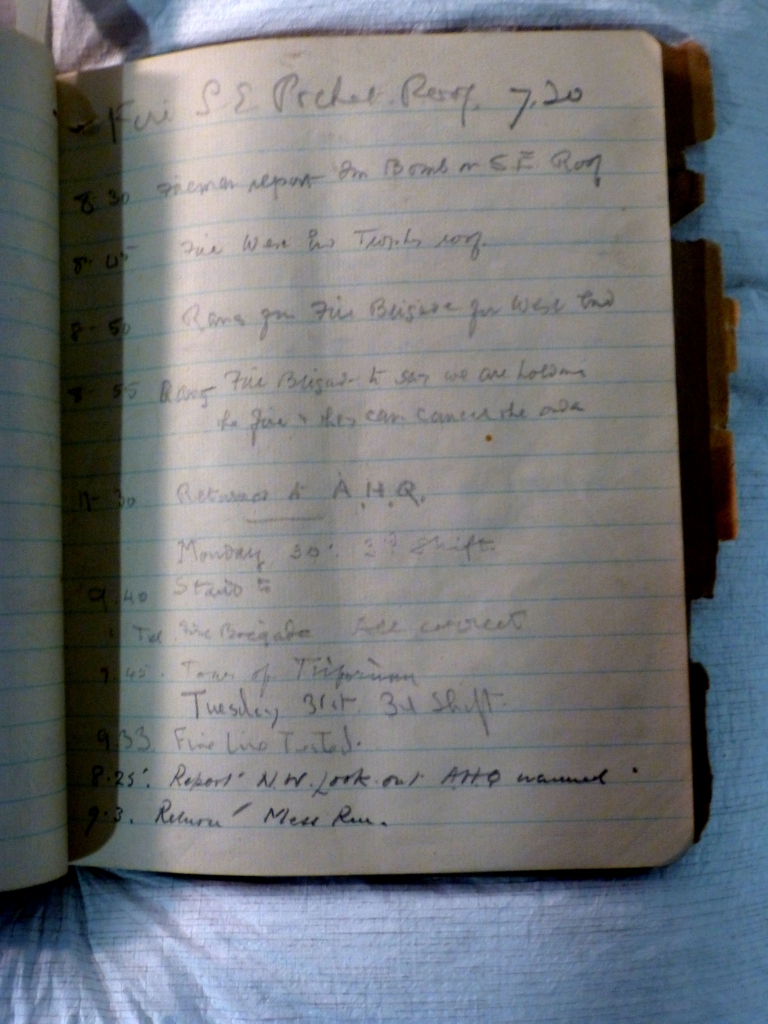

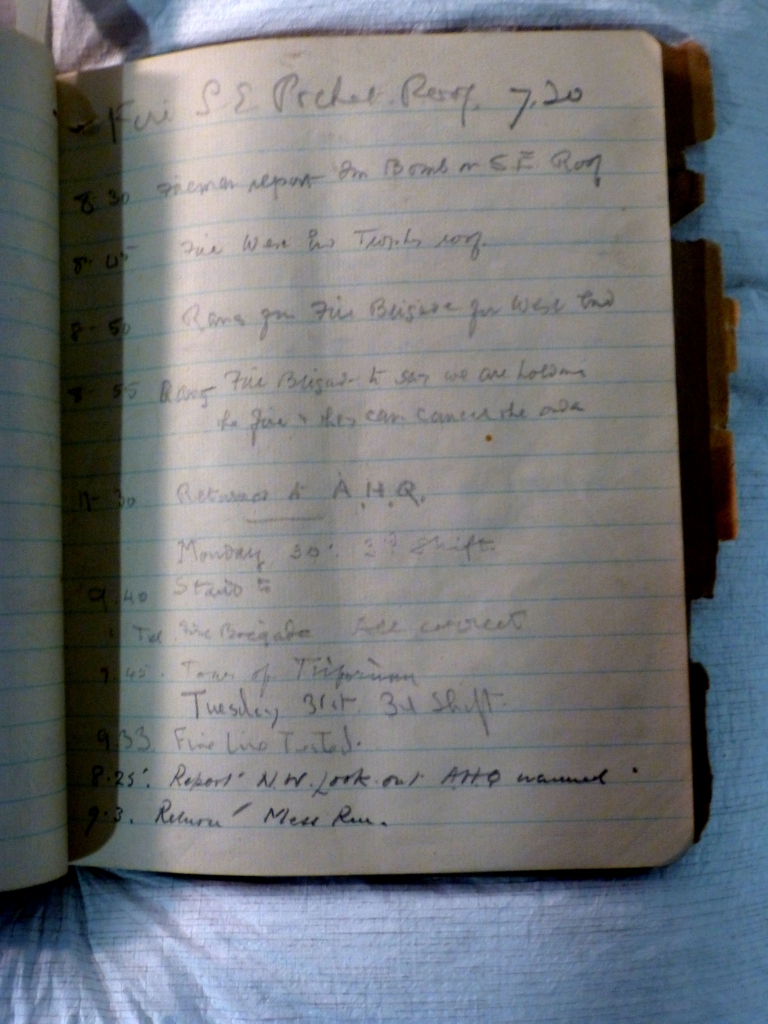

The second page continues:

With events continuing into the evening:

- Fire S.E. Pocket Roof 7.20

- 8.30 Fireman report of bomb on S.E. roof

- 8.45 Fire West End Trophy (room or roof?)

- 8.50 Rang for Fire brigade for West End

- 8.55 Rang Fire Brigade to say we are holding the fire and they can cancel the (call?)

- 11.30 returned to AHQ

The “stand to” was then recorded the following Monday morning at 9:40 after what must have been a most exhausting night.

The log does not really do justice to the fight that the Watch had on their hands that night. I suspect that there were too many events and they were too busy to phone through details.

The book “St. Paul’s Cathedral In Wartime” by W.R. Matthews, the Dean of St. Paul’s during the war and who was in the Cathedral on the night of the 29th provides a more detailed account.

“in half an hour fires were raging on every side of the Cathedral, but we had no leisure to contemplate the magnificent though terrible spectacle for many bombs had fallen simultaneously on different parts of the Cathedral roofs. Watchers on the roof of the Daily Telegraph building in Fleet Street, who had a full view of St. Paul’s from the west thought that the Cathedral was doomed and told us later that a veritable cascade of bombs was seen to hit and glance off the Dome. Some of these bombs fell on the long stretches of the Nave and Choir roofs and some into what are known as pocket roofs, i.e. the lower roofs over the aisles; others landed in the Cathedral gardens producing a fairly like effect amongst the trees and shrubs on the north and south sides. Twenty eight incendiary bombs fell on St. Paul’s and its precincts that night. Some of the bombs penetrated the roofs and came to rest on the brick or hardwood floors over the vaulting, but some lodged in the roof timbers and started fires. It may be imagined that the volume of the attack and its dispersal over the wide area of the roofs presented a hard problem for the defence”

Adding to the number and location of fires, the Watch now faced a further problem, the availability of mains water.

That evening, three, thirty-six inch and twelve other large mains were damaged and when water was most needed there was a very low tide on the River Thames. Hoses and pumps pulling water from the river became clogged with mud and the use of Fire Boats became impossible.

By 8 p.m. there were some three hundred pumps at work in and around the City, trying to pull water from whatever source was available, the number of pumps also having the effect of reducing the overall pressure.

The effect on the Cathedral was the failure of all external supplies of water. The Watch was now down to the supplies of water that had been stored in whatever container could be found or used in the days of preparation. Planning that proved extremely fortunate as these kept up supplies to the stirrup pumps which proved the key tool in getting to incendiary bombs and fires in extremely difficult places across the roofs of the Cathedral. Stirrup pumps and sand bags now became the only tools available in the defence of the Cathedral.

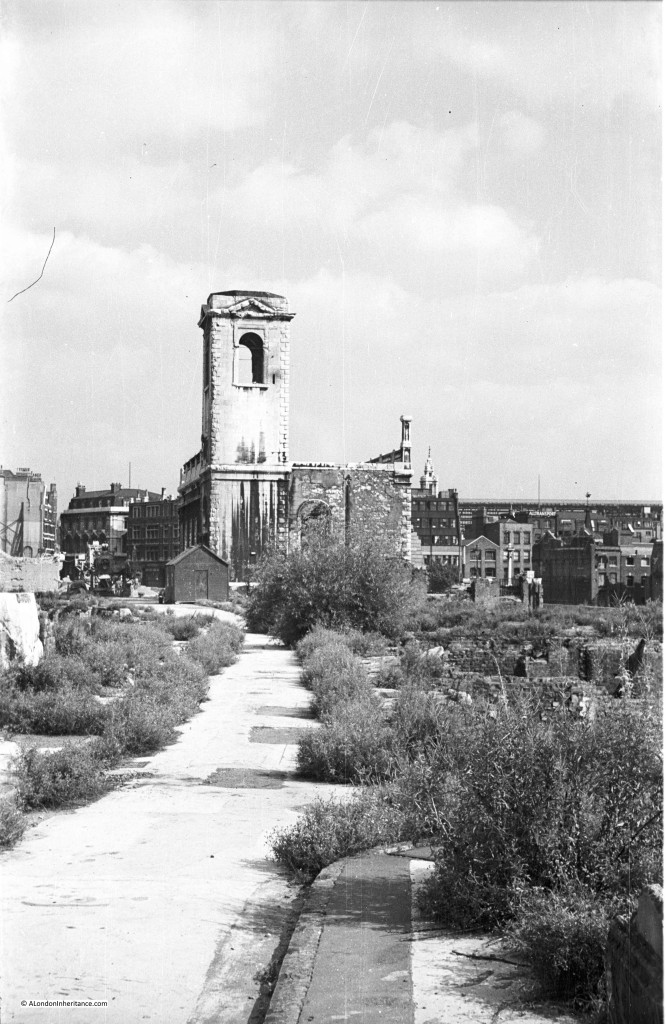

The conditions on the roofs for the Watch must have been extreme. The following photo (©Mirrorpix) was taken from the Cathedral on the evening of the 29th December looking over towards Paternoster Square.

The Chapter House can be seen in flames with the roof lost in the lower part of the photo, just to the left of the statue. See my earlier post which can be found here showing the same scene taken by my father after the war, along with my 2014 equivalent.

The photo also shows one of the other challenges to the Watch and to fighting the fires in general. On the evening of the 29th there was a strong south-west wind. This had the effect of blowing heat, burning embers and smoke across the Cathedral from the south, rapidly spreading the fires and making conditions for fighting the fires extremely hazardous (there were also reports that charred paper from City offices had been found as far afield as Upminster after the 29th)

Returning to the Dean’s account of the evening:

“The action in the Cathedral became for a while a number of separate battles on which small squads fought incipient fires at different places on and beneath the roofs. Some of the bombs were easily dealt with, as for example that one which fell to the floor of the Library aisle and was extinguished by Mr Allen and myself. I have a special affection for the scar left by that bomb on the floor – it represents, I feel, my one positive contribution to the defeat of Hitler ! But some of these battles were arduous and protracted. Bombs which lodged in the roof timber were very dangerous and hard to tackle. More than one of these took three-quarters of an hour before they were put out and had to be attacked by two squads, one from below and the other from above. The lower squad had the additional discomfort of being drenched by the pumps of their more elevated colleagues.”

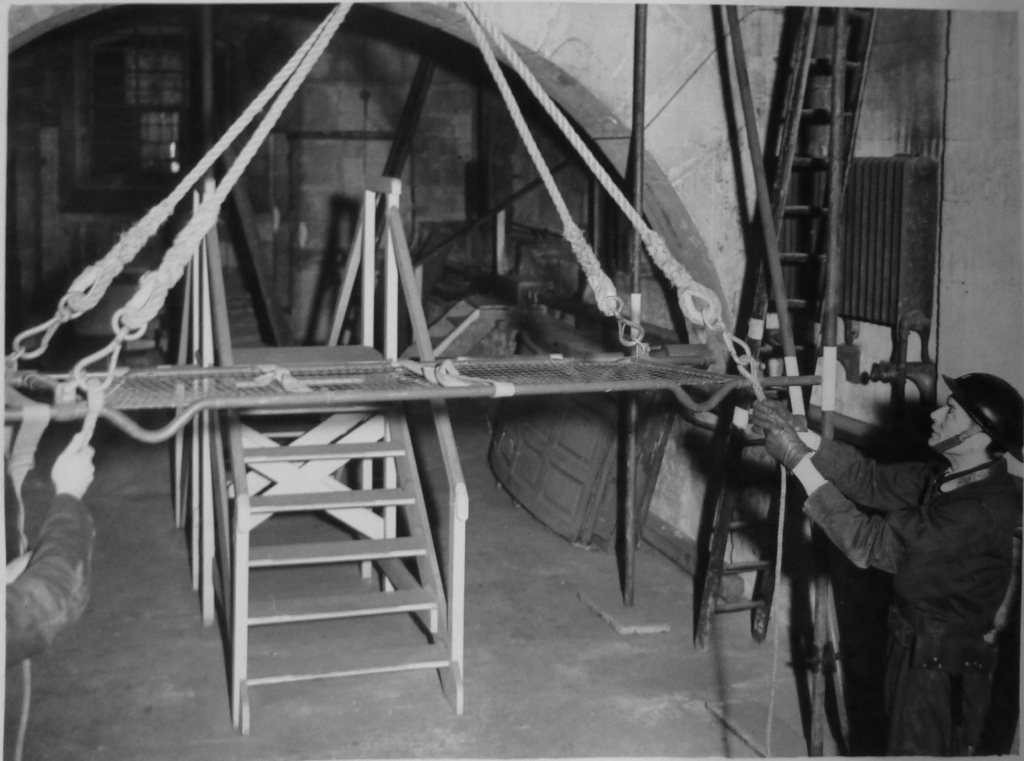

The benefit of all the previous evenings of preparation, training and exercise and the work of Godfrey Allen in preparing the Watch and the defences of the Cathedral were now clearly evident in the way the members of the Watch went to work.

The Dome was always considered a very vulnerable part of the Cathedral. Not only was the Dome one of the defining features of the Cathedral, it was also at a very high risk from fire.

Wren’s design for the Dome was ingenious. Along with the Dome, there is the Lantern structure at the top of the Dome. the Dome alone could not support the weight of the Lantern, therefore Wren constructed three domes. There is the interior Dome, visible from the floor of the Cathedral. Above this there is a second Dome, actually a brick cone structure reaching up to the Lantern and supporting the weight of the Lantern. The third, exterior dome that we see from outside the Cathedral is constructed around this cone, with a wooden structure supporting the lead on the exterior of the Dome and supporting the weight of the Dome by wooden beams and joists resting onto the cone and the floor.

Any penetration of the Dome by an incendiary would gain access to this wooden structure which could quickly develop into a fire that would engulf the Dome.

Whilst the Watch was busy fighting the fires across the roof, the Cathedral received a call from Cannon Street Fire Station to say that the Dome was on fire. A team was dispatched to deal with this new threat and found that whilst the Dome was not actually on fire, an incendiary bomb had not fully penetrated the Dome and was lodged half way through the lead roof, which was beginning to melt.

Watch teams were allocated to patrol the Dome, but fighting fires in this area was difficult with Watch members having to balance along beams of wood to get to a fire, carrying a stirrup pump and bucket of water.

The bomb eventually fell out of the Dome and onto the Stone Gallery where it was quickly dealt with. The molten lead presumably not providing enough support and the weight distributed in such as way that it fell outwards rather than in.

The survival of the Cathedral was critical for many reasons. In 1940, America had not yet entered the war and there were factions that assumed that the UK was a lost cause and could not withstand the German onslaught. When the Dome was hit, American reporters were already sending cables to their newspapers in the US that St. Paul’s had been lost. The ability of London and the country as a whole to survive the blitz was critical in demonstrating to the US that the UK would withstand the attack and act as a base for any future attack on the occupied continent.

The Dean records: “Whilst the whole sky over the City was brighter than day with the flames that were leaping all around St. Paul’s, Mr Churchill sent a message to the Guildhall that the Cathedral must be saved at all costs. The Guildhall sent the message on to us. We were grateful for this voice from the outside assuring us that the thoughts of many were with us that night, though it would not be true to say that the Watch was spurred to greater efforts, for it was already extended to the limit of human endurance.”

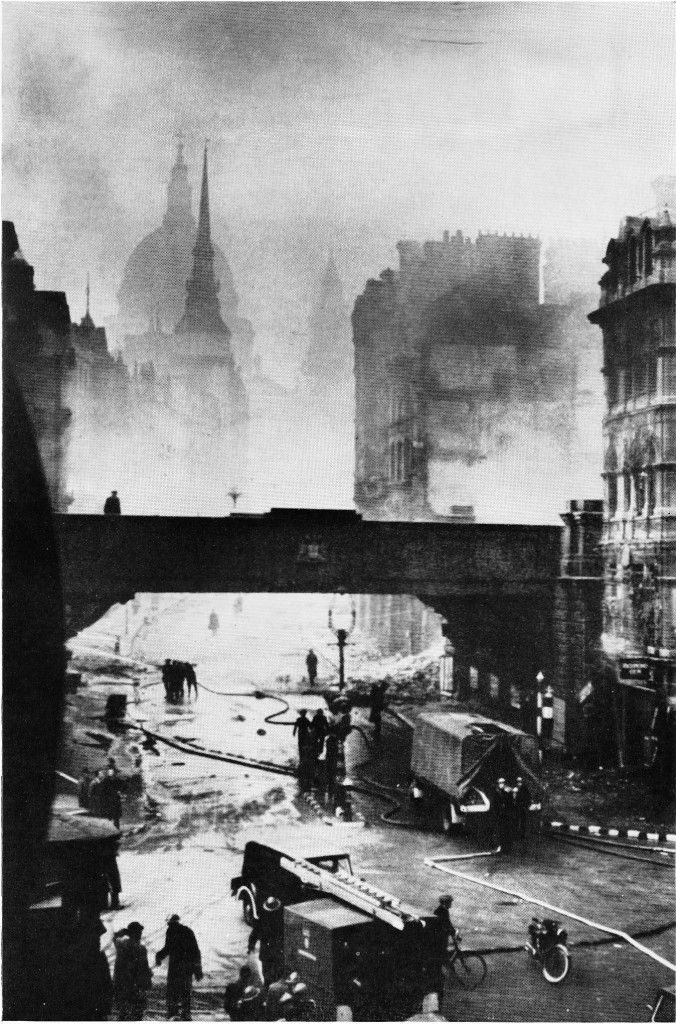

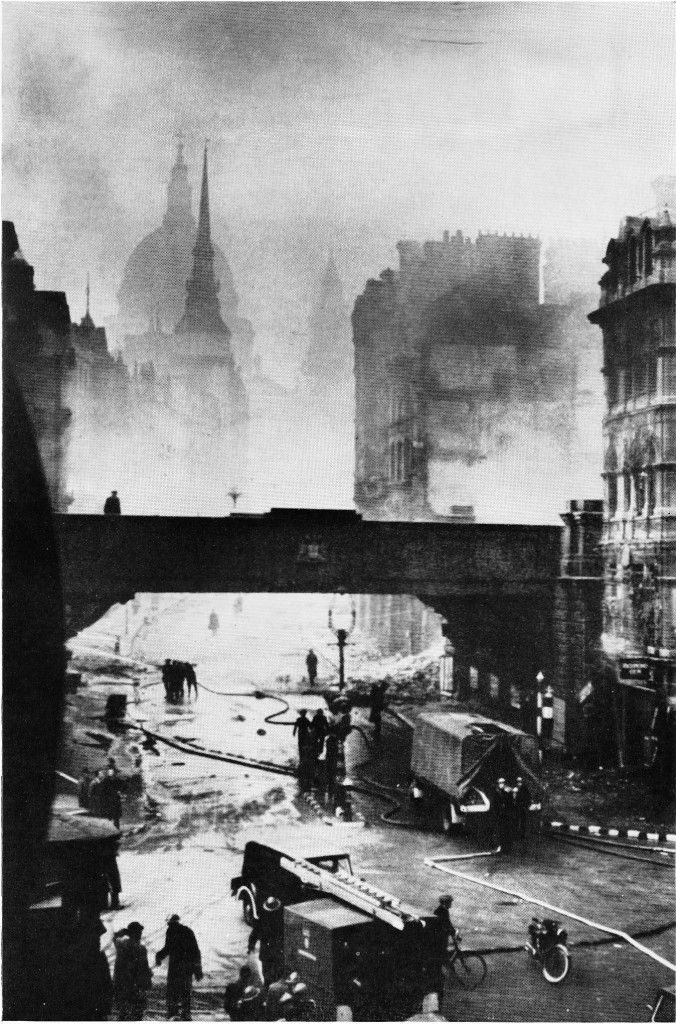

By late evening the areas around St. Paul’s were ablaze. In addition to the above photo of Paternoster Square, the following is from Ludgate Hill looking up towards the western front of the Cathedral on the evening of the 29th December 1940 (photo ©Mirrorpix)

This photo was taken at night, with no artificial lighting. The scene is lit by the fires burning around St. Paul’s. It was claimed to be as bright as day. The vehicles lined up along the road are those of the fire crews working on the surrounding buildings. To the right can be seen fires in buildings between the Cathedral and the River and to the left can be seen the glow of fires from Paternoster Row and down towards Cheapside.

74 years later, on the evening of the 29th December 2014 I took the following photo of the same scene:

A much calmer scene with only the stopping of tourist buses providing any activity.

Just to the left of where this photo was taken is Ave Maria Lane, a short road that leads from Ludgate Hill to Amen Court. On the 29th December 1940 this lane was ablaze with fire crews working in pairs trying to stop the spread of the fires (photo ©Mirrorpix). Two men and a hose trying to control a long stretch of burning buildings, with the constant threat of explosions, bombing and the structural failure of the burning buildings causing a catastrophic collapse into the street.

And on the 29th December 2014 I stood in Ave Maria Lane contemplating what it must have been like, and took the following photo:

And on the 29th December 2014 I stood in Ave Maria Lane contemplating what it must have been like, and took the following photo:

Another perspective of the area around St. Paul’s on that evening can be found in the memoirs of the wonderfully named Commander Sir Aylmer Firebrace, Chief of the Fire Staff and Inspector-in-Chief of the Fire Services. On the evening of the 29th December he was working through London to see what needed to be done and what support was required. He started travelling by car from Southwark where serious fires were developing. Across the river he had to abandon the car and worked through the city, walking from Cannon Street to the Redcross Street Fire Station just to the north of St. Paul’s.

Another perspective of the area around St. Paul’s on that evening can be found in the memoirs of the wonderfully named Commander Sir Aylmer Firebrace, Chief of the Fire Staff and Inspector-in-Chief of the Fire Services. On the evening of the 29th December he was working through London to see what needed to be done and what support was required. He started travelling by car from Southwark where serious fires were developing. Across the river he had to abandon the car and worked through the city, walking from Cannon Street to the Redcross Street Fire Station just to the north of St. Paul’s.

Redcross Street is one of those lost under the Barbican development. Fore Street used to extend to St. Giles Cripplegate from where Redcross Street ran roughly north to Golden Lane which still remains. Stand on the north side of St. Giles and look slightly west of north across the water and that is the routing of Redcross Street and the location of the Fire Station is directly in front of you.

We join Commander Firebrace in the control room at the Redcross Street Fire Station:

“In the control room a conference is being held by senior London Fire Brigade (LFB) officers. How black – or, more realistically, how red – is the situation, only those who have recently been in the open realise.

One by one the telephone lines fail; the heat from the fires penetrates to the control room and the atmosphere is stifling. earlier in the evening, after a bomb falls near, the station lights fail – a few shaded electric hand lamps now supply bright pin-point lights in sharp contrast to a few oil lamps and some perspiring candles.

The firewomen on duty show no sign of alarm, though they must know, from the messages passing, as well as from the anxious tones of the officers, that the situation is approaching the desperate.

A women fire officer arrives; she had been forced to evacuate the sub-station to which she was attached, the heat having caused its asphalt yard to burst into flames. It is quite obvious that it cannot be long before Reccross Street Fire Station, nearly surrounded by fire will have to be abandoned.

The high wind which accompanies conflagrations is now stronger than ever, and the air is filled with a fierce driving rain of red-hot sparks and burning brands. The clouds overhead are a rose-pink from the reflected glow of the fires, and fortunately it is bright enough to pick our way eastward down Fore Street. Here fires are blazing on both sides of the road; burnt-out and abandoned fire appliances lie smouldering in the roadway, their rubber tyres completely melted. the rubble from collapsed buildings lying three and four feet deep makes progress difficult in the extreme. Scrambling and jumping, we use the bigger bits of masonry as stepping stones, and eventually reach the outskirts of the stricken area.

A few minutes later L.F.B. officers wisely evacuate Redcross Street Fire Station, and now the only way of escape for the staff and for the few pump crews remaining in the area lies through Whitecross Street (also now lost under the Barbican development)”.

Quite remarkable to stand outside St. Giles Cripplegate and consider these events happened here 74 years ago, and that this area is so close to St. Paul’s Cathedral, which had it not been for the Watch would almost certainly have suffered the same fate and been severely damaged if not destroyed by fire.

One of the frustrations for the St. Paul’s Watch and also for many members of the Fire Services was that so much could have been saved if many of the buildings also had a Watch, or were open for access. From their vantage point on the Cathedral, members of the Watch saw many instances where an incendiary landed on the roof of a building and smouldered before the heat caused a fire to take hold.

Immediately after landing, an incendiary bomb was relatively easy to do with, sandbags, a stirrup pump and a small supply of water were sufficient, however after a while when the magnesium coating had ignited, temperatures reached very high levels and anything flammable within range of the bomb would catch fire and spread very quickly. Had other buildings employed teams to watch over the roofs, many fires could have been extinguished quickly. As it was the weekend, many buildings were also locked and secured so whilst a bomb may be visible on the roof, gaining access was a challenge.

The lack of water also prevented fires being extinguished. The St. Paul’s Chapter House could have been saved when hit by an incendiary if there had been six buckets of water immediately available.

The scope of the fires that the L.F.B had to fight and the resources needed were immense. The regional L.F.B record for the night recorded that:

- There were 6 conflagrations that needed one hundred pumps each

- 28 fires each needing over thirty pumps

- 51 fires needing twenty pumps

- 101 requiring 10 pumps each

- And 1,286 fires which had one pump each

Pumps were sourced from the rest of London and surrounding regions to help fight the fires in the heart of the City. Around 2,300 pumps were eventually in use that night. (Just before the war there had been only 1,850 pumps covering the whole of Great Britain. Far more than this were in use in the City alone on that one night.)

Late in the evening, although the City was ablaze and the Watch keeping a careful watch on the possibility of burning embers spreading the fire to the roof of St. Paul’s the All Clear was surrounded.

German plans had been for further waves of bombers after the first waves with incendiaries, to then attack with high explosive bombs which would have ripped the city apart, have been a very severe risk to those trying to control the fires and to the equipment used to fight the fires.

The weather over France had been getting worse, the grass runways were being turned into mud and late in the evening the command was given to cancel the waves of bombers with high explosive bombs.

The tide also turned in the Thames and the returning water provided much-needed resources for the considerable numbers of pumps now fighting the fires throughout the rest of the night.

After a long night, the situation was bought under control by 8 a.m. on the morning of the 30th, however many fires continued to burn, but did not spread.

My father was 12 years old at the time and lived in flats near Albany Street just off Regents Park. His account of the night:

“1940 ended spectacularly with the great City fire raid of December 29/30. The sirens wailed shortly after 6 p.m. and the raid was in full swing in a matter of minutes,. For once there was only the sound of planes passing overhead and gunfire, no explosives seemed to be dropping. I found this very strange, And then slowly came the orange glow of fires, small at first then increasing in intensity. During a lull in the raid I ventured out to walk the short distance to Camberley House where I knew that a flat section of the roof, accessible to tenants, would provide me with a panoramic view from Highgate to the City. The sight was breath-taking. Two miles to the south-east raged a huge line of fire with great columns of flames shooting hundreds of feet into the night air at intervals as buildings collapsed into the inferno, and later as the raiders returned in numbers showers of incendiaries could be heard with a noise like an express train, well heard above the combined noise, planes, guns and the shots of the night fighters overhead. the sound was unusually distinctive. The raid ended abruptly, just after 9 p.m. and to my astonishment the raiders never returned. After the “All Clear” sounded I went out again looking for shrapnel, now a form of currency between boys. The night had become as day, the great orange glow reflected from the low clouds. Even the barrage balloons appeared as glowing orange balls. the smell of smoke filled the air and from the far off, the roar of flames and dull crash of falling buildings combined to sound like some distant, gigantic blow lamp”

The Dean of St. Paul’s summed up the night’s events:

“The Cathedral came out of this night of havoc with no serious injury. When we reviewed the situation, remembering the perils which had been endured, we were astonished and thankful. The damage amounted to two burnt partitions in the Library Aisle, local injury to the lead and timber work of the roofs and a desk in the Surveyor’s office. When we looked out over the City we saw an appalling scene of destruction. The area to the east, west and north was laid waste and many of the buildings burned for days.”

After the All Clear had been sounded, Londoners were amazed to see that St. Paul’s Cathedral was still standing. The billowing smoke and colour created by the fires resulted in the strange visual effect of the Dome of the Cathedral appearing to float on a glowing sea of cloud, with the colours changing as the wind blew in different directions.

An estimated 24,000 incendiary bombs fell on London that evening. The potential impact of each bomb being amplified by the damage that a single out of control fire could cause, given strength by the wind that blew across the City.

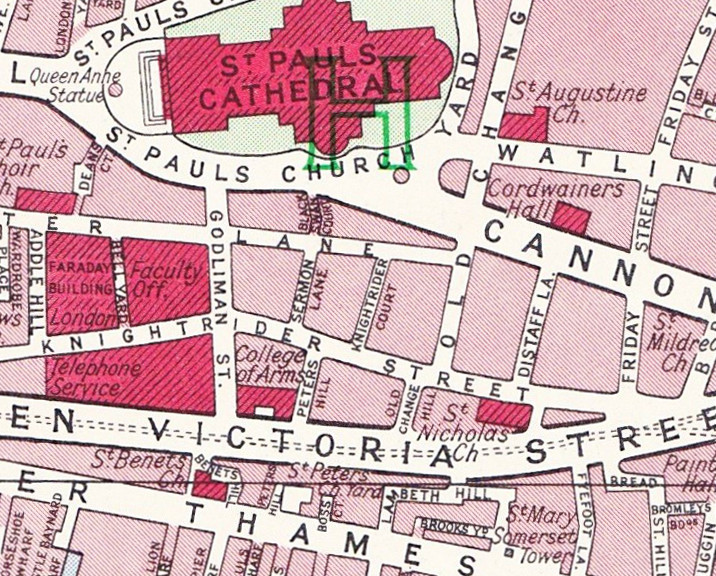

To give an idea of the devastation, the following extract from the London County Council Bomb Damage Maps (source: the London Metropolitan Archives) illustrates the bomb damage around St. Paul’s. (Purple is damaged beyond repair). Whilst this covers the period 1939 to 1945, much of this damage was on the night of the 29th December 1940.

The scenes that welcomed workers returning to the City on the Monday morning were of devastation. Fires still burning and the streets covered in debris and with fire fighting equipment. The following photo was taken on the morning of Monday 30th December and shows Ludgate Circus and the road up to St. Paul’s. The results of the night’s work still clearly visible.

To walk around the Cathedral, late in the evening of the 29th December 2014, the contrast with that night 74 years ago was very apparent. The streets were quiet, Christmas decorations added light to the scene and the Cathedral was lit up, not by fire but by spotlights which nightly turn the Cathedral into one of the most dramatic and beautiful landmarks of the City.

The incendiary that lodged in the Dome, must have been in the area of the Dome shown in the above photo. It was reported by the Fire Station at Cannon Street so would have been in this segment.

Towards Cheapside, another difference between the two nights is apparent. In 2014, the night was clear with a moon shining across the City. Had the weather been like this 74 years ago, the later waves of bombers carrying high explosive would have been able to take off and the outcome for St. Paul’s, the City and the Fire Fighters would have been very different.

And down on the Thames, the tide was high in 2014 and had this been 1940 would have been able to supply the water needed for the hundreds of pumps across the City and for the riser water system of St. Paul’s Cathedral, along with the Fire Boats that would have attacked the fires in buildings along the water front..

That rounds off my two posts covering the St. Paul’s Watch and the raids on the night of the 29th December 1940.

I hope this has done justice to the work of the Watch during this single day, and during the war, as well as the London Fire Brigade who worked tirelessly throughout that night, and through the war.

It has been fascinating to research and learn and I have only scratched the surface on this subject. I recommend the excellent books in the sources section below for further reading.

The sources I used to research this post are:

- I am very grateful to Sarah Radford, Archivist at St.Paul’s Cathedral for providing access to the documents covering the St. Paul’s Watch

- The Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral during the war, the Very Reverend W.R. Matthews published a comprehensive account titled St. Paul’s in Wartime published in 1946 (this article only scratched the surface of the work of the Watch. I recommend this book for a detailed and very readable account)

- St. Paul’s In War and Peace published by the Times Publishing Company in 1960

- Fire Service Memories by Commander Sir Aylmer Firebrace published in 1949

- The London County Council Bomb Damage Maps 1939 – 1945 published by the London Topographical Society 2005

- Bartholomew’s Reference Atlas of Great London published 1940

- The three black and white photos covering St. Paul’s, the view over Paternoster Square and Ave Maria Lane are from Mirrorpix who retain the copyright for these photos

alondoninheritance.com